Abstract

The spatial political logic of the construction of Chinese metropolitan areas (CMAs) is unique and complex, involving the interaction of power, spatial production, and the construction of political rationality between multiple scales. Taking the representative Nanjing metropolitan area as an example, we use the “material–organizational–discursive” analytical framework of politics of scale theory to analyze the construction logic of CMAs. This study finds the following: (1) In general, the CMA is a high-quality spatial construction resulting from multi-city negotiation, inter-provincial collaboration, and central–territory linkage, and has generally undergone a process of increasing the power of subjects, nested power relations, frequent scale interactions, and complex interest games; among them, planning is not only a scale tool for competing for power, but also an important representation of the results of multiple power games. (2) In terms of the construction of material space, both the delineation of boundaries and the cross-border connection of infrastructure represent rational thinking and stand as two-way choices of the two power subjects in the MA based on the maintenance and expansion of their own spatial development rights. (3) In terms of organizational space construction, CMAs mainly adopt flexible means, with bilateral and multilateral cooperation at the horizontal level, while there is a certain power inequality at the vertical level. (4) In the construction of discursive space, CMAs have experienced increasing construction significance, escalating scale subjects, and overlapping discourse narratives, and the contrast of power relations has also changed. The contribution of this paper is an expansion of the analytical framework of politics of scale based on the division of spatial dimensions, which provides a new perspective for understanding the construction of CMAs, and also helps us to picture Chinese city–regionalism.

1. Introduction

The metropolitan area (MA) has become a type of spatial combination of urban groups with universal significance worldwide [1] and is an important unit for a country or region to intervene in global competition [2,3]. MAs create close economic and social ties within a specific geographical space that transcend the jurisdiction of individual local governments [4,5] and involve multiple levels of government and the close interaction of power relations between them [6,7]. Thus, MA construction is not only an economic process but also a political one [8]. It has been demonstrated that MA construction is rooted in a specific political-institutional context [9]. Although the construction of MAs in Western countries also requires the political involvement of government, the co-parenting of multiple forces, such as government, enterprises, and citizens, is more common, wherein the forces are relatively balanced [10]. In contrast, Chinese metropolitan areas (CMAs) have obvious traces of government domination [11], and the game of spatial power at multiple scales of government is played throughout the whole process of the construction, forming a complex and unique set of spatial, political, and logical implications.

However, current studies on CMA have mostly focused on land use transformation [12,13], spatial structure evolution [14], urban–rural integration and development [15], ecological protection [16], and other themes, and the spatial political logic of MA construction has not yet attracted sufficient attention from scholars. In the past decade, Chinese governments at all levels have been adjusting their spatial power configurations through games and interactions to accelerate the construction of “sub-state spaces”, such as city clusters, MAs, new districts, industrial parks, and the Great Bay Area. Under this development trend, it is particularly necessary to analyze the spatial political logic of MA construction, which not only helps us to improve our understanding of the laws of such spatial development but also helps to enhance the understanding of the operational process of the Chinese government. The theory of politics of scale, which integrates the dual perspectives of spatial production and power interaction, is one of the core theories of spatial politics [17,18] and is instructive in interpreting the construction laws of “sub-state spaces” such as MAs.

Therefore, this paper aims to investigate the power interaction process unfolding in the construction of CMAs by multi-scale governmental subjects through the theory of politics of scale. The main questions guiding this study are as follows: In what ways do spatial powers interact in the process of CMAs construction? How do spatial powers interact among governments at multiple scales? The case of the Nanjing metropolitan area (NMA) is used to illustrate this interaction process. By doing so, we provide a new analytical perspective for the study of CMAs, revealing the complex power relations and interaction mechanisms at play behind this economic development space, which will help us to understand the construction process of MAs in the Chinese context. At the same time, this study contributes an explanation for the construction of MAs in a government-led context, which complements the existing understanding of the laws of MA development and contrasts with the logic of MA construction in Western countries [11]. In addition, this study also elaborates on the regional development model and governmental operation within the Chinese context. It is important to emphasize that the concept of “power” referred to in this study comes from Foucault’s perspective. According to Foucault, power is a complex network of relations that operates in a specific space [19], and multiple subjects interact with each other in a wide range of ways [20]. This coincides with the construction history of CMAs, where the same decentralized power interaction exists in the process of their spatial construction, forming a network of horizontal and vertical power relations.

The typicality of the NMA lies in that it was not only the first MA to commence construction in China but was also the first cross-provincial MA, and it was the first to receive approval from the central government. Compared with other MAs in China, the NMA has had the longest history of construction and has undergone several rounds of inter-scale spatial power games involving various levels of governmental entities at the central, provincial, and municipal levels [21]. As a case study, the NMA is effectively representative because the spatial power interaction chain operated in its construction process is longer, and the logic of interaction is more complex, meaning it can deeply reflect the spatial political laws of CMA construction.

In what follows, we first sort out the connotations of the concepts of scale and politics of scale according to chronological order. Then, we construct the “material–organizational–discursive” analytical framework of politics of scale based on the division of spatial dimensions. Next, we use the above framework to systematically analyze the spatial political logic of the construction of CMAs, using the NMA as a case study. Finally, we discuss the research findings, propose policy recommendations to promote the construction of CMAs, and point out the limitations of this paper, as well as future research directions.

2. Definition and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Definition of Connotation

Since the 1970s, a series of political and economic shifts, accompanied by post-Fordist changes in modes of production that gradually replaced Fordism, and the transformation of governance that was triggered by the rise of neoliberalism, have driven the research on the “scale shift” in western human geography. The city has shifted from a self-evident scale entity to a scale space involving political elements such as power, institutions, and relations. The shift in the ontological understanding of the political effects of spatial scale has further enriched the study of cities and regions.

The concept of “scale” was first applied to cartography and surveying in geography, and its essential connotation is objectivity, fixity, and instrumentality [22]. After the 1970s, some scholars, based on Lefebvre’s theory of spatial production, further proposed that “scale” as a spatial dimension also has a humanistic meaning of social construction and social production [23], among which Taylor was the first to propose a “political economy of scale” analytical framework in which “city–state–world” is vertically nested [24]. In the 1980s, although a number of scholars initially explored the “scale shift”, the theoretical construction of politics of scale, scale production, and reproduction is still an “understudied” area of research [25]. Until the 1990s, the critical perception of the traditional concept of scale was more widely and intensively discussed in various fields such as geography, political science, and sociology [26], and spatial scale was no longer regarded as an objectively existing material entity [27], but increasingly as a historical product in the context of social construction and political strategy [28]. The understanding of scale is often reflected in hierarchical “metaphors”, such as concentric circles, pyramids, scaffolds, and wormholes [29]. The complex power relations underlying these “metaphors” [30] have brought the political properties of scale to the fore [31], and the concept of scale has thus become an important means of representing the power interactions between multiple layers of various geographical events and processes, and their driving mechanisms [32].

The concept of “ politics of scale” was first introduced by Smith, and although he did not specify its definition, he illustrated the basic process of politics of scale through the case of the New York homeless protesting against the government’s repossession of the park, which is to achieve some political purpose by expanding the scale [33]. Subsequently, Smith further illustrated that the production and reproduction of scale could be used as a political strategy through his study of homeless transportation in New York [34]. Following this path of social construction, Delaney et al. proposed the “political construction of scale” and argued that the political process in the construction of scale is continuous and open and includes a wide range of subjects such as state and non-state actors [31]. Swyngedouw also emphasized the production and transformation of scale, noting that socio-spatial struggles and political strategies often revolve around the problem of scale, and the dynamic balance of power is often linked to the reshaping of scale or the production of a new gestalt of scale [35]. In emphasizing the dynamic construction and reconstruction of scale, Brenner distinguished between singular and plural “politics of scale”, the former emphasizing the production, reconstruction, or competition of socio-spatial organization in a single, self-enclosed spatial unit, and the latter emphasizing the production of specific differentiation, ordering, and hierarchy among scales in a multi-layered hierarchy of scales. He argued that the politics of scale in the plural is more effective in capturing the intrinsic correlations among geographic scales and systematically describing the production and transformation of scales, and should therefore be called “politics of scalar structuration” or “ politics of scaling” [29].

After the concept of “politics of scale” was introduced to China by the scholar Miao in 2004 [36], it has also shown good explanatory power in the exploration of topics such as social conflict events [37], the “Belt and Road” strategy [38], and regional governance [39]. However, since the theory was born in a Western context and introduced to China later, its areas of application in the Chinese scenario need to be further expanded, and the applicability of the theory needs to be further tested.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

Space is a central concept that cannot be circumvented in the study of politics of scale [32]. The theory of spatial production argues that space is both the basis for the operation of power and the object on which power exerts its influence and that space, power, and politics are inseparable [40]. The politics of scale theory pays special attention to space, and its production process, and the concept of space is constantly emphasized in research. Scholars have also come to realize that because the totality of concepts attached to space is too complex, it must be dimensionalized in order to advance research [18,26]. Therefore, some scholars have constructed a framework for the analysis of politics of scale based on the division of spatial dimensions.

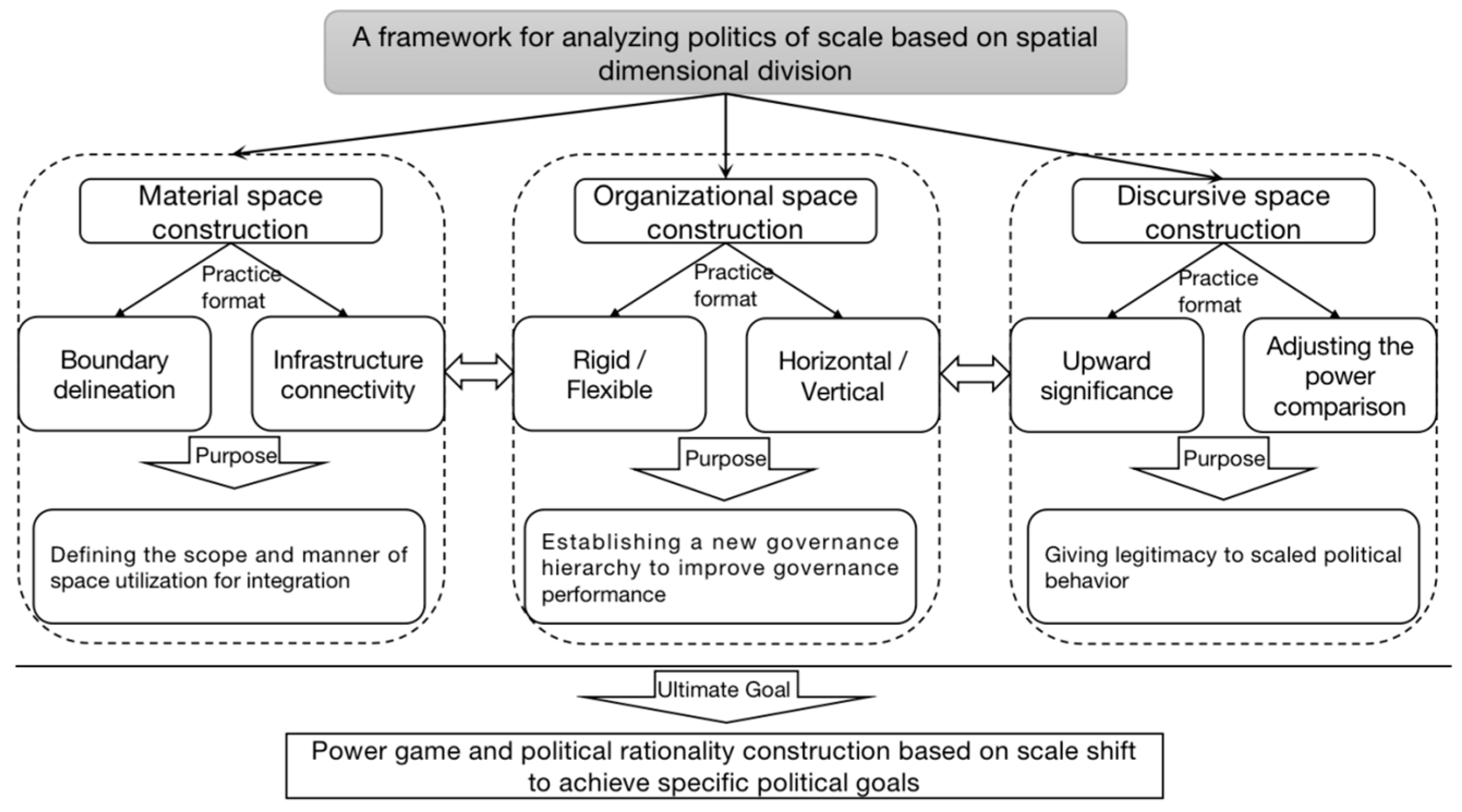

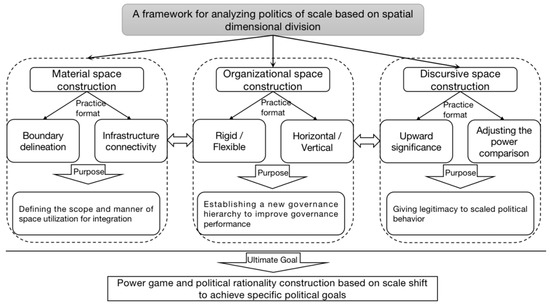

Cox delineated spaces of dependence and spaces of engagement in his analytical framework, emphasizing the role of local interests and their networks of connections in politics of scale, and aiming to portray the scale transformation process of local power participation within regional and global competition [30]. However, the framework focuses on actors’ behaviors in the pushing up, down, and out of scale, and pays insufficient attention to the structural features of politics of scale. Taking into account both structural and actor dimensions, F Wang and Y Liu divided the spaces involved in politics of scale into three categories: material space, organizational space, and discursive space [41]. Based on a comprehensive consideration of the Chinese context, this study complements and extends the specific forms of the practices and goals of the three types of spaces and constructs a more systematic analytical framework of politics of scale based on the division of spatial dimensions (Figure 1), which is used to portray the operational logic of politics of scale events.

Figure 1.

Politics of scale analysis framework of the “material–organizational–discursive” type.

Material space reconstruction is the most basic practical means and expression of politics of scale; it is a type of spatial practice that can be directly observed and perceived and is mainly realized through various types of planning. Specifically, there are two methods of practice: one is to specify the scope of scaling through the delineation of boundaries [41] and to thus mark the use of different spaces; the other is to promote the integration process at the engineering level through the inter-governmental connection of roads, water resources, cables, and other infrastructures. The promotion and implementation of the two are intertwined with multiple interests and rely on specific organizational settings or institutional designs.

Organizational space can also be understood as institutional space, and its change involves a rearrangement of institutions and powers attached to the reconfiguration of material space, aiming to improve the performance of regional governance through the establishment of a new governance hierarchy. At present, there are two main bases for the classification of organizational space changes within academic circles. In the first, depending on whether to break through the original administrative structure, the two types of rigid and flexible are available [42]—the former directly dissolves the original administrative institutions and sets up new institutions according to the developmental needs of the incoming regional spatial management; the latter adds new informal institutions to the basis of the original administrative framework, and unites and extends the spatial control across regions [39]. The second is divided, according to the direction of power, into vertical and horizontal categories, with the former mainly manifesting as “bargaining” or “command obedience” between subjects at the upper and lower levels, and the latter mainly manifesting as collusion or competition of interests between subjects at the same level [18].

The construction of discursive space refers to the consolidation of fragmented narratives into relatively coherent discourses that give legitimacy to actors’ scaled political actions [43]. The space of discursive expression is a “space of representation” [44] with clear ideological implications, and its changes are often accompanied by shifts in the attention of multiple subjects and the reallocation of resources, making discursive expression an important act in shaping spatial power patterns [37]. Compared with material space and organizational space, the construction of discursive space is more “hidden”, and there are two main ways of approaching it: first, by elevating the significance of the scale political events to attract the attention of higher-level subjects and establish a wider range of attention so that the actors can encourage more discourse around, and attract more resources towards, the scale political events [45]; the second is to break from the original scale structure, changing the way the discourse is carried out so as to readjust the power relations within the scale political events [43]. These two approaches are “two sides of the same coin” and often occur simultaneously. Moreover, in general, the new discursive narrative is not a total rejection of the old narrative, but a superimposition that enriches the content of the discourse, thus giving multiple new meanings to the conversation about spatial construction.

The “material–organizational–discursive” analytical framework identifies the field and form of operation of spatial power and can be used to explore the logic of the construction of CMAs. Within the context of China’s authoritarian political system, although MAs are a kind of economic development space, their construction is still dominated by the government. Therefore, in the construction of CMAs, the material space, the organizational space, and the discursive space are defined by the interaction of power between multiple levels of government.

3. Empirical Analysis

3.1. Study Area

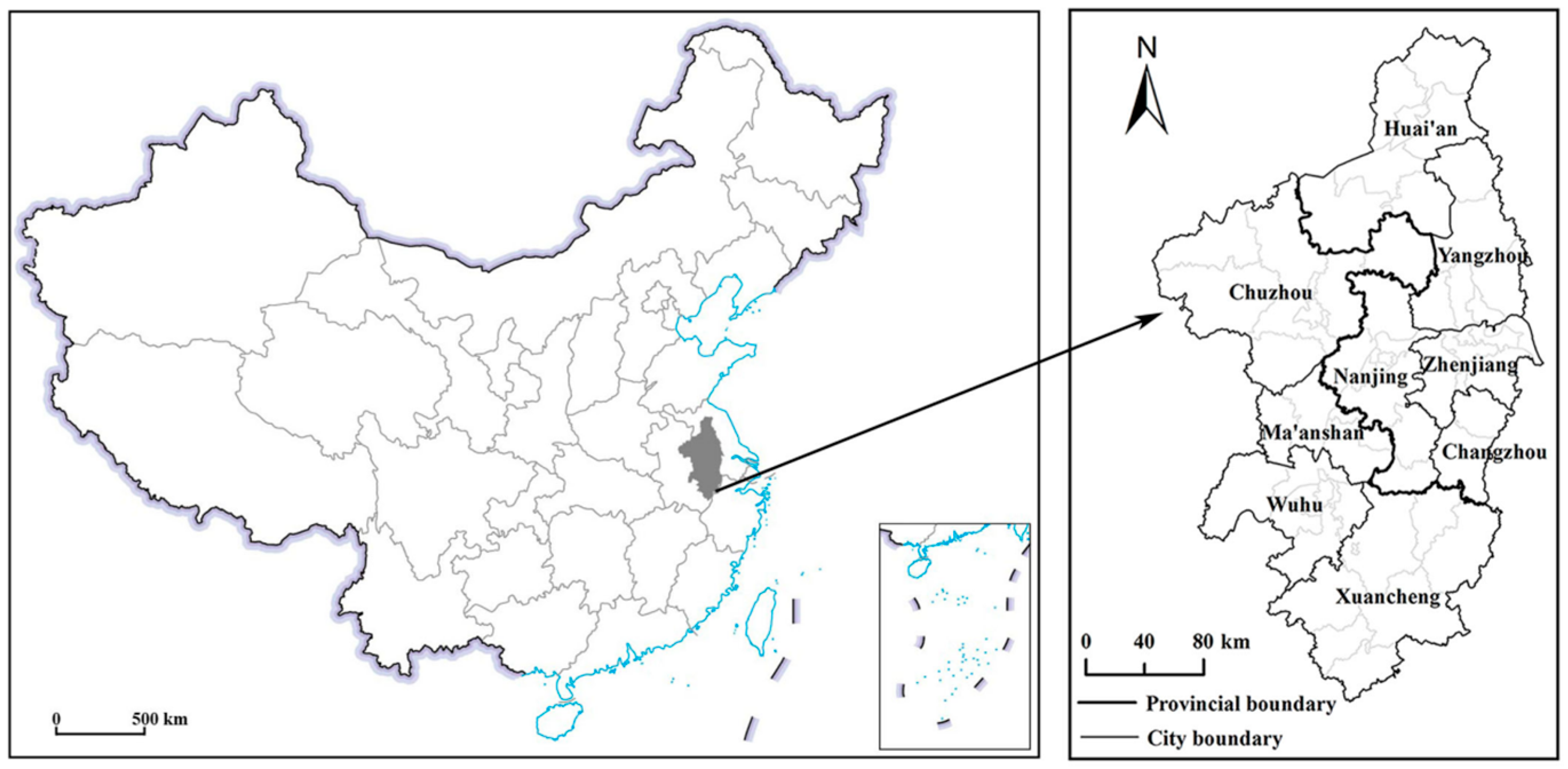

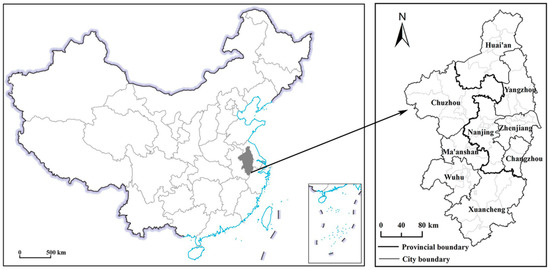

The NMA, an integrated development region centered on Nanjing, is located in the eastern part of China and in the central area of the urban belt that extends along the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River (Figure 2). Among the existing MAs in China, the NMA is highly representative in terms of construction history, construction significance, and development maturity.

Figure 2.

Location of the Nanjing metropolitan area (NMA). Note: This map is based on the geographical scope of the NMA in 2021, wherein Changzhou City only includes Jintan District and Liyang County. Details of the changes in the geographic scope of the NMA are documented in Appendix A.

(1) The NMA was the first MA to be planned and constructed in China. Its predecessor was the Nanjing Economic Zone, established in 1986, which spans 19 cities in three provinces: Jiangsu, Anhui, and Jiangxi. In 2000, the Jiangsu Provincial Party Committee and Provincial Government formally proposed the concept of the NMA at the Jiangsu City Work Conference and identified six cities in Jiangsu and Anhui as member cities. After that, multiple parties entered negotiations and began to act towards the requirements of the development, and released plans for scope adjustments in 2003, 2013, and 2021, respectively, before finally determining the “8 + 2” member pattern.

(2) The NMA was the first cross-provincial MA in China, straddling Jiangsu and Anhui provinces. Nanjing’s unique geographic location has forced the construction of an MA across provinces. This “cross-provincial” nature means it includes a wider range and higher level of power players than other MAs [21], with power interactions across the central, provincial, and municipal levels. This is conducive to producing more valuable information, thus increasing the depth of this study.

(3) The NMA is one of the most highly developed MAs in China and has made great achievements in several fields. In terms of infrastructure, the NMA has made rapid progress in the construction of transportation, water, and energy projects and has formed a dense network of connections. Economically, the cities within the NMA have developed various forms of industrial cooperation, which have greatly contributed to economic growth. In 2021, with a land area of 0.7% of China (66,000 km2) and a resident population of 2.5% (35,482,000 people), the NMA generated 4.1% of China’s GDP (CNY 4.6 trillion). In terms of public services, cities within the NMA are constantly breaking down administrative barriers and promoting the sharing of high-quality resources in education, medical care, public transportation, tourism, and other areas. For example, a unified registration platform has now been established in the NMA, which allows for the booking of medical services and the checking of reports in different places. The rich construction experience of NMA means this study has been able to obtain sufficient reference materials.

3.2. Materials and Methodology

First, we collected three planning documents released during the construction of the NMA (NMA Planning (2002–2020), https://www.docin.com/p-275003530.html, accessed 6 June 2023; NMA Regional Planning (2012–2020), https://www.mayiwenku.com/p-27688515.html, accessed 6 June 2023; NMA Development Planning, https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xwdt/ztzl/xxczhjs/ghzc/202202/t20220228_1317613.html, accessed 6 June 2023) and read them very carefully. The spatial planning documents involve the division of spatial management powers of each level of government [46,47]. By reading the above three planning documents, we can fully understand the positioning and functions of each level of government in the construction of NMA and lay the foundation for analyzing the power interaction between them later.

Second, we searched the official website of the Nanjing Municipal Government for all public information related to the NMA using the keyword “Nanjing Metropolitan Area” (https://www.nanjing.gov.cn/site/zgnj/search.html?searchWord=)%E5%8D%97%E4%BA%AC%E9%83%BD%E5%B8%82%E5%9C%88&siteId=10&pageSize=10&searchWord2=%E5%8D%97%E4%BA%AC%E9%83%BD%E5%B8%82%E5%9C%88&(pageNumber=2, accessed on 6 June 2023). Nanjing, as the core city of NMA, has collected and summarized all the information related to the construction of NMA; therefore, the above public information is complete and has a high degree of credibility in recording the construction process of NMA. Reading this public information in chronological order, we can clearly understand what important events occurred in the construction of NMA, which governmental entities participated in it, and the main tasks of different construction stages, which provide abundant materials for later analysis.

Finally, we searched for related reports on Baidu and Google using the keyword “Nanjing metropolitan area”. After the screening, we selected three reports (https://www.sohu.com/a/509969379_121106832; http://www.360doc.com/content/17/0206/20/32367625_627095468.shtml; http://www.wxrb.com/doc/2021/02/10/65907.shtml, accessed on 6 June 2023). The authors of these three reports were all participants in the development of the NMA plan, and they were familiar with the construction process of the NMA. Therefore, the contents of these three reports are credible. From these reports, we were able to obtain many details of the construction of the NMA (e.g., the NMA Regional Plan (2012–2020) was not submitted to the National Development and Reform Commission for some reason), which can help us to more fully analyze the construction process of the NMA.

3.3. The Logic of Politics of Scale in the Construction of CMAs

The MA is essentially a spatial carrier facilitating regional integration, and its construction processes also revolve around the construction of and competition between various spaces. As such, in this study, we construct a framework for analyzing the politics of scale based on the division of spatial dimensions. Throughout the process of constant changes in, and reconfigurations and transformations of, material space, organizational space, and discursive space, a complex and interesting logic of politics of scale is concealed within CMAs.

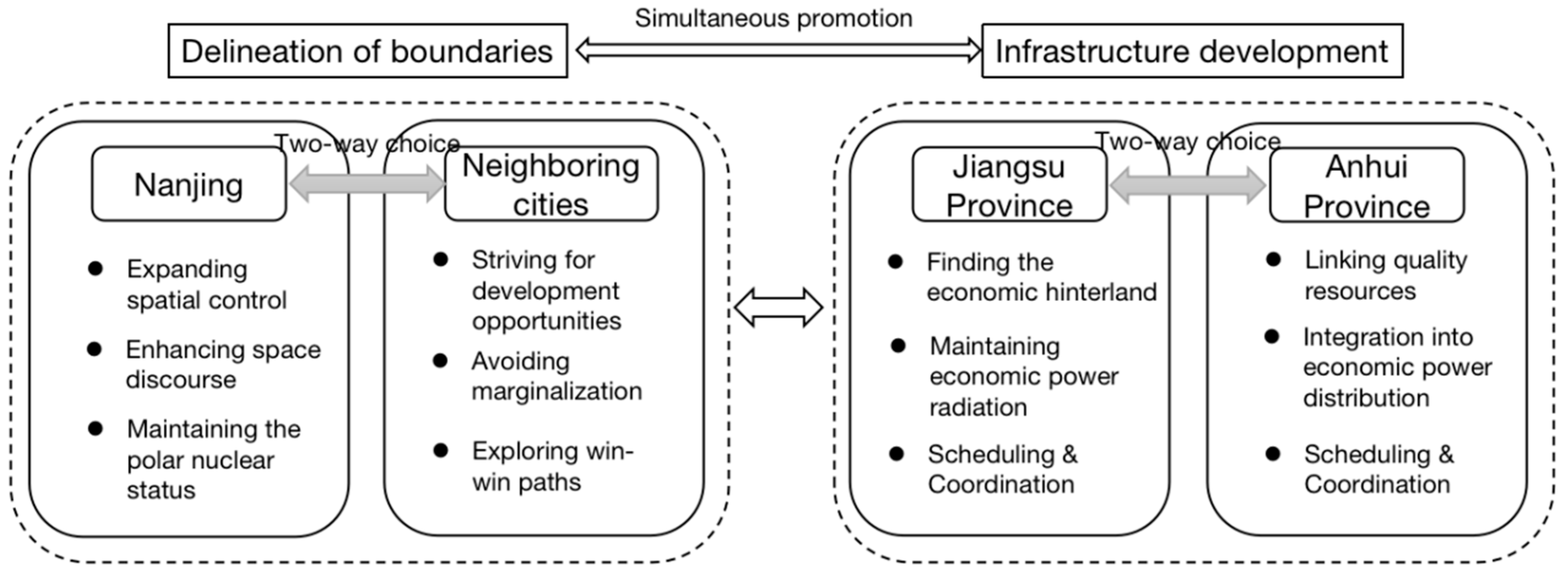

3.3.1. The Logic of Material Space Construction

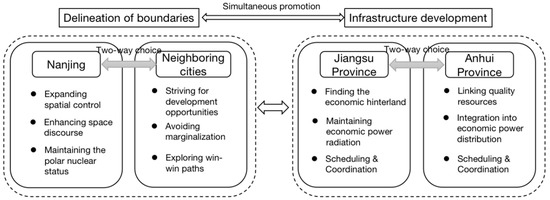

The construction of the material space of the NMA was the result of a two-way choice, aiming at more predictable development through collective action (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Logic of the NMA’s material space construction.

First, the delineation of boundaries is a two-way choice between Nanjing and its neighboring cities. The first step in the construction of the MA is to define the size and boundaries of the territorial scope by delimiting the member cities, as the effective operation of power depends on a specific bounded space [48]. On the one hand, Nanjing, as the capital city of the province, faces the problem of the insufficient economic hinterland, as the economically developed southern Jiangsu region of the province is more closely related to Shanghai, while the vast central and northern Jiangsu regions north of the Yangtze River are beyond Nanjing’s reach. This has forced Nanjing to expand its hinterland to the west and south in order to expand its spatial control and discourse and thus maintain its pole position within its region.

On the other hand, for neighboring cities and their rulers, “entering the MA” means more development opportunities, better expected performance, and greater promotion possibilities [49], and actively “entering the MA” can dampen the threat of being marginalized in the competition for regional spatial development rights. In addition to external boundaries, there are also boundaries within the MA, which depend on the ways in which different development blocks are used. In the NMA, the spatial utilization pattern of “one pole, two zones, four belts, and many clusters” has been defined, and the scaling of different areas has been stipulated. The determination of the internal boundaries came as the result of a mutual game between Nanjing and the neighboring cities, led by the provincial governments of Jiangsu and Anhui, and its conclusion fits into the vision of spatial power development of both parties—a “two-way run” that leads to a win–win situation.

Secondly, the inter-regional connection at the infrastructural level is a two-way choice made by the Jiangsu and Anhui provinces. On the one hand, the NMA has opened up “cut-off roads”, extended existing lines, and built new traffic arteries to bring Jiangsu in the east and Anhui in the center into closer ties in terms of people, capital, and industry. This fulfills the political aspirations of both Jiangsu and Anhui, with the former looking westward for a broader economic hinterland to enhance its development momentum and the latter looking eastward for better development resources to drive growth.

On the other hand, the successful implementation of many projects is inseparable from unified scheduling and coordination at the provincial level, which is actually a two-way choice. For example, the construction of flood control and drainage facilities in the Yangtze and Huaihe River basins, the construction of the Chuzhou (Qingshan)–Yangzhou gas pipeline, the joint construction of the Nanjing–Huai’an–Chuzhou railroad, and the construction of the Nanjing–Wuhu highway all depend upon the joint participation of the two provinces. With the joint efforts of the Jiangsu and Anhui provinces, the density, structure, and quality of all kinds of connected infrastructure within the NMA have been continuously improved, which has strongly facilitated the process of regional integration.

3.3.2. The Logic of Organizational Space Construction

Brenner pointed out that various alliances emerge in the process of regional development to enhance the advantages of particular places by shaping the scale hierarchy [50]. The NMA is an important experimental area for regional governance across provincial administrative regions and has used flexible means to build a series of consultation platforms and mechanisms to realize the reorganization of governing power within the MA space. The setting of agendas has also gradually expanded from industrial collaboration, infrastructure construction, and public service provision to a wider range of areas such as ecological protection, scientific and technological co-creation, education sharing, disaster prevention and control, and cultural exchange, and has gradually become structured, institutionalized, and standardized.

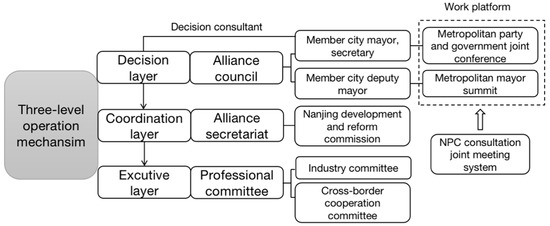

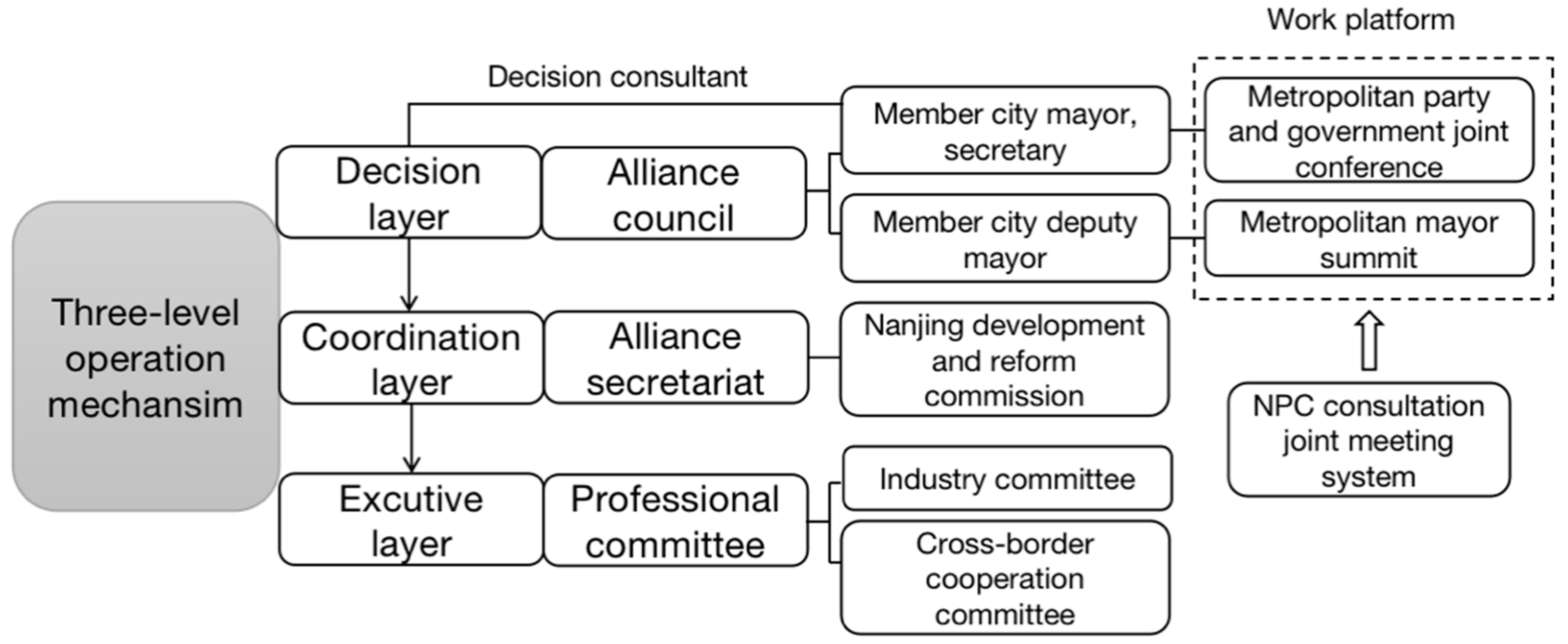

Horizontally, the construction of the NMA’s organizational space is based on cooperation, which is mainly reflected in multilateral cooperation and bilateral cooperation. Multilateral cooperation aims to establish a deliberative mechanism that satisfies all participating subjects and has undergone a continuous improvement process from “government cooperation” to “joint party–government” and “three-level operation”. From the joint meeting of mayors during the Nanjing Economic Zone event in 1986 to the Metropolitan Area Development Forum in 2003 and then to the Mayors’ Summit in 2007, it has primarily been the relevant government departments that dovetailed with the mayor who have acted as leaders. As the cooperation in the MA continues to deepen, more and more matters require higher-level governance authority for their coordination, so in August 2013, the NMA mayors’ summit was formally upgraded to a joint meeting of the party and government, including the secretaries of the municipalities, in order to improve the decision-making capacity by pushing up the scale. It should be emphasized that, in China’s political system, the secretary of a city has a higher administrative rank and broader decision-making authority than the mayor.

However, the degree of multilateral cooperation in the NMA has not yet allowed the formation of a set of mature and unified institutional arrangements, and the culture committee, new media development alliance, NGOs, and other deliberation platforms and subjects are still left out of core agenda setting. Therefore, after two more years of experimentation, in March 2015, the Implementation Plan for the Reform of the Mechanism for Sound Collaborative Development of NMA was introduced, which formally established a three-level cooperation mechanism with the interface of “decision–coordination–executive”, which systematically integrated the governance process, consultation platforms, and related subjects. The decision layer is responsible for determining major matters, such as the development direction and principles of the MA; the coordination layer is responsible for handling the daily affairs of the MA and providing services for multiparty dialogues; and the executive layer is responsible for implementing specific industry development plans and cross-border cooperation matters [21]. Since its establishment, the mechanism has been continuously improved, and in 2019, a consultative joint meeting of the directors of the Standing Committee of the Nanjing Metropolitan People’s Congress was established as an important supplement to expand the governance authority to the legislative level. Then, in 2022, the first cross-provincial collaborative legislation was set out, and a decision related to the protection of the Yangtze finless porpoise was adopted.(Details of three-level cooperation mechanism of “decision–coordination–executive” in the NMA are provided in Appendix B).

In contrast, bilateral cooperation involves fewer subjects and more focused objectives, with government departments on both sides, generally only interfacing with each other. Bilateral cooperation at the municipal level focuses more on industrial development, such as the establishment of the Nanjing–Huai’an Special Cooperation Zone and the Nanjing–Ma’anshan Industrial Cooperation Park, while bilateral cooperation at the provincial level focuses more on the coordination of cross-provincial affairs (e.g., environmental management, emergency management) and the upward push of development planning scales (e.g., the joint submission of the NMA Regional Plan (2012–2020) by Jiangsu and Anhui provinces to the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC).

Vertically, there is also a clear imbalance in power within the extensive cooperation of the organizational space, which manifests as follows.

(1) Between the central and local levels. Although both the central and local governments aim to promote regional unity and integration, the intervention of central power may also raise difficulties for local MA spatial cooperation due to the different levels of power and decision-making horizons. For example, the NMA and the Hefei MA are currently both national strategies recognized by the central government, but there is a partial overlap of member cities (Wuhu, Ma’anshan, Chuzhou). While the central government intends to link the two MAs, the overlap in scope has raised many obstacles to local cooperation, and there were even rumors that the scope of the NMA would be reduced to Nanjing–Zhenjiang–Yangzhou. In China’s special pressure-based system, local forces often have to compromise with the central government’s intentions [51]. In the above-mentioned scope dispute, Jiangsu and Nanjing made the statement that “the scope of the MA is not static”, and “the MA will be planned and developed in a more inclusive manner”, dampening the controversy and creating more space for the central government, the two provinces and the cities.

(2) Inter-provincial. Although there are various forms of cooperation between the Jiangsu and Anhui provincial governments, in general, the main driving force and influence for the construction of the NMA still comes from Jiangsu, with Anhui lacking a clear statement at the provincial level. This is an important illustration of the “core–fringe” structure of the MA in terms of the power scale, which to some extent, reflects Anhui’s desire for autonomous decision-making and its unwillingness to be controlled.

(3) Inter-municipal. In terms of positioning, Nanjing is the only core city in the MA; in terms of level, although it is also a prefecture-level city, Nanjing has sub-provincial authority; in terms of economy, Nanjing’s GDP accounts for more than 30% of the total economic output of the NMA. Therefore, compared with other cities (the weaker side), Nanjing (the stronger side) hold greater power and plays a leading role in planning, facility preparation, organization, and mechanism construction.

The above power inequality issue introduces a lot of uncertainties in the cooperation of subjects at all levels in the MA, but from a positive perspective, it is also an important force in promoting the continuous adjustment and optimization of the organizational space.

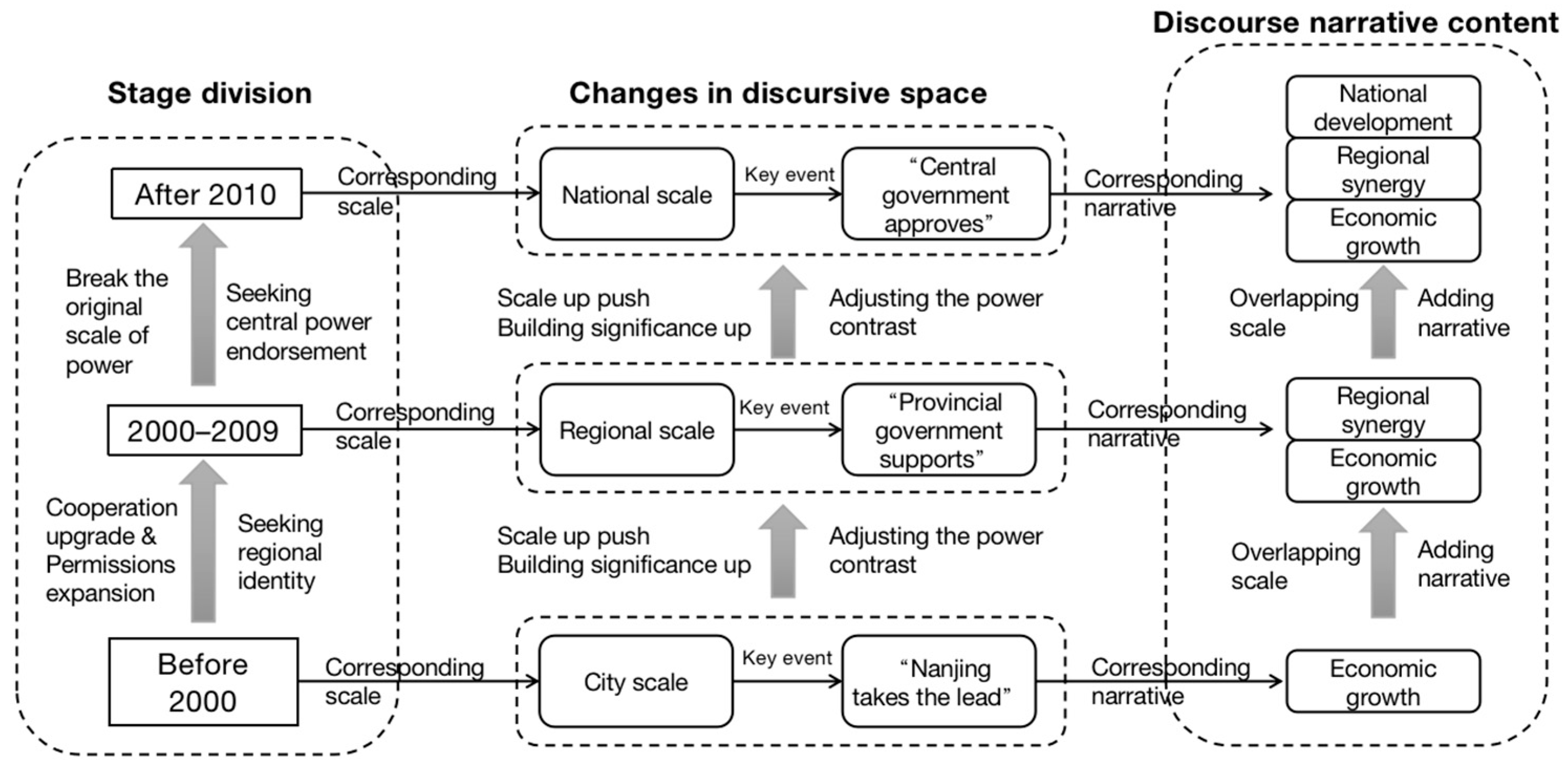

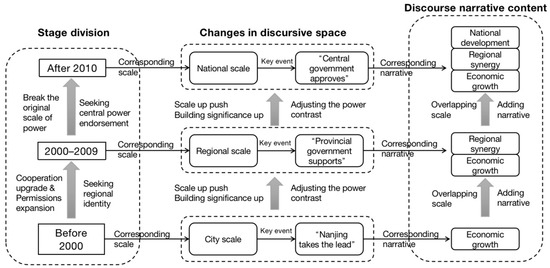

3.3.3. The Logic of Discursive Space Construction

While the construction of the material and organizational space continues to advance, discourse also represents an important power tool in the construction of the NMA. Initially, only economic growth was emphasized, but later, regional synergy and national development narratives were added, and now, a multi-scale overlapping spatial pattern of discourse expression has been formed. On the whole, the construction of the discursive space has gone through three stages: “Nanjing takes the lead”, “the provincial government supports”, and then “the central government approves”. During this process, the positioning and construction significance of the NMA increased, and the contrast in power relations changed (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Logic of NMA’s discursive space construction.

Before 2000, the discourse of the NMA was focused on the city scale, and the narrative content focused mainly on economic growth. The main goal of the Nanjing Economic Zone, spearheaded by Nanjing, was to build a unified market for the free flow of production factors. Since this was the embryonic period of NMA construction, the level of cooperation was limited and mainly stayed at the inter-city level; the field of cooperation was singular, focusing on economic exchanges and cooperation between enterprises, and the form of cooperation was fragmented, lacking systematic organizational and institutional constraints. Despite the many shortcomings at this stage, it laid an important foundation for the spatial adjustment and scale reconstruction of NMA in the future. More crucially, the existence of these shortcomings has become an important motivation for Nanjing to unite all the forces in the MA and raise the significance of MA construction at the regional scale in order to obtain more attention and resource support at the provincial level.

From 2000 to 2009, the discourse surrounding the NMA was pushed up to the regional scale, with the addition of a narrative of regional synergy. After 2000, the acceleration of the process of the reterritorialization of global capital raised the competitive scale of various “sub-state spaces”, such as MAs and urban agglomerations, emphasizing their important role in regional synergistic development [50]. At this stage, the NMA encountered multiple pressures to expand cooperation fields, improve the quality of cooperation, and build cooperation mechanisms, and it was urgent here to change the original scale structure by exploiting the voice and endorsement of higher-level subjects, and to promote the construction of the MA so as to break from the singular narrative of economic growth and move toward the collaborative development of the region, covering a wider range of fields. As a result, the cities in the NMA, led by Nanjing, jointly raised the significance of MA construction to establish its identity at the regional scale; it was thus finally recognized at the provincial level and reflected in planning documents. In short, adding a regional synergy narrative to the discourse is not only an objective requirement if the NMA is to move toward high-quality development but is also an important way for the municipal and provincial governments to readjust the spatial power distribution.

After 2010, the discourse surrounding the NMA was further pushed up to the national scale and entered into the national development narrative. In fact, since the beginning of its construction, the NMA has attracted national attention through its unique model of cross-provincial collaboration. However, the exploration and development of this innovative model did not happen overnight, as inter-provincial collaboration requires much time. Therefore, it was not until 2010 that the NMA was included in the Regional Plan for the Yangtze River Delta Region, issued by the NDRC, and officially recognized at the national level. The NMA Regional Plan (2012–2020) was completed in 2013 under the leadership of Jiangsu and Anhui provinces but was not submitted to the national level for various reasons. In 2019, the NDRC issued the “Guidance on Fostering Modernized MAs”, and Jiangsu and Anhui provinces seized the opportunity to prepare and submit the latest version of the NMA Development Plan, which was approved in 2021. The construction of the NMA officially became China’s national strategy, and its construction rose in significance to the level of support for national development. The intervention of the central government via their discourse has given a strong impetus to the construction of a new scale of power, giving the NMA an advantage in its competition with other “sub-state spaces” of the same type, but the complexity of power interactions also greatly increased during the process of its construction, which will require further attention in future studies.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

In this paper, we explored the spatial political logic of MA construction in China via a qualitative method. In doing so, we took the NMA as our study case. We developed a theoretical framework of “material–organizational–discursive” based on the division of spatial dimensions and conducted an empirical study using it. The main findings can be summarized as follows: (1) From the experience of NMA, higher-level subjects have been involved in the process of constructing CMAs, and a political logic of scale with extensive cooperation and partial disagreement has gradually formed in the multi-scale interaction of spatial power. In this process, spatial planning plays an indispensable role as an important tool for a power struggle at scale and is the key presentation of the results of the game between multiple power subjects. (2) In terms of material space, the delineations of boundaries and infrastructure connections in CMAs are the result of two-way choices made by multiple power players based on rational thinking, which have laid an important physical foundation for the subsequent game. (3) In terms of organizational space, the construction of CMAs mainly employs flexible means and does not break away from established administrative structures. Horizontally, there is a wide range of bilateral and multilateral cooperation, while vertically, much power inequality can be observed between municipalities, provinces, and the central government. This power inequality is the driving force behind the continuous restructuring and upgrading of the organizational space. (4) In terms of discursive space, CMAs are pushing upwards, from “core city takes the lead” to “provincial government supports” and “central government approves”, forming a superposition of multi-scale narratives of economic growth, regional synergy and national development. Discourse expression is not only an important tool for gaining support from higher-level authorities but is also a core approach to gathering consensus from more subjects.

Our study contributes to expanding the analytical dimension of MAs, providing a broad perspective of spatial politics, and breaking through the limitations of existing studies in terms of perspectives and ideas. Although the MA is a kind of economic–social development space, interactions of political power are also at play in its construction process [8]. In particular, in the Chinese context, the government has a deep-rooted political investment in the construction of various scales and types of spaces [52], meaning the political implications of the construction of CMAs are very obvious, with negotiations, games, and cooperation around spatial power being undertaken by multiple levels of governmental entities [11]. However, the existing literature mainly focuses on spatial economic logic and does not pay enough attention to the spatial political logic embedded in the above process, failing to analyze it systematically. Our study fills this gap, and the deep involvement of municipal, provincial, and central governments in the construction of the NMA fully reflects the significant influence of political power on spatial construction in China, which is consistent with the findings of Luo et al. [11]. Considering that spatial construction is a continuous process, it is also necessary to trace the development of the NMA over time in order to understand the latest developments in spatial power flows and mechanisms of action. In addition, it should be emphasized that this paper also advances the “material–organizational–discursive” scale political analysis framework proposed by Wang et al. [41], which is systematically complementary. This framework also has implications for the analysis of the political logic of space in other sub-state spaces. In addition, this paper advances the research on discursive relations in the logic of spatial politics. In fact, although discursive relations are an important part of spatial political practices [43,53], they are often neglected by researchers because they are not easily observed directly [54]. This study analyzed in depth the changing process of discursive relations in the construction of NMA, which has very important theoretical and practical significance.

Our study also contributes to the exploration of city–regionalism in China. The aim of city–regionalism is to move beyond the idea of building individual cities “on their own”, and to establish a regional development consortium to address the dilemma of inter-city competition brought about by urban corporatism [55]. Empirical studies have shown that city–regionalism is rooted in specific political structures, institutional designs, and development models [56,57]. In the available literature, scholars have reached a basic consensus that in China, city–region construction and governance is a state-led project, rather than a spontaneous process, with the state always playing a key role [58,59]. This is very different from the competitive city–regionalism [60], smart city–regionalism [61], and extrospective city–regionalism [62] exhibited in Western countries. This is due in equal part to China’s special up-and-down and peer-to-peer governmental relationships and to its deep tradition of state intervention in economic development and social construction [57]. For Li, city–regionalism in China can be understood as the co-existence of top-down and bottom-up processes, with hierarchical structures and command control within the government system playing an important role [57]. The case of the NMA fits this logic, reinforcing Li’s view and further deepening our understanding of the city–regionalism in China.

The enlightenment and significance of this article on practice also deserve elaboration. Due to the special political system and regional development model, the construction of CMAs is full of interactions between different levels of governmental entities, which dominate the development direction of the CMAs. Therefore, in the future development of CMAs, different levels of government must learn to work together. On the one hand, the governmental entities at the same level should learn to find the greatest possible convention of interests by means of consultation platforms and deliberation mechanisms so as to bring into play the synergistic effect of “1 + 1 > 2”, and make good use of the scale upward push to include higher-level entities and seek large scale power endorsement to change the original power scale pattern, so as to obtain more initiative and discourse for the scale political behavior. On the other hand, the upper and lower levels of government entities should communicate with each other in a timely manner, constantly adjusting their decision-making intentions to maintain the same goal and avoiding conflicts between scales and meaningless internal conflicts caused by conflicting intentions; the interaction between the central and local governments also needs to properly handle the interaction between “recentralization of state power” [51] and “local decentralization” [63].

Of course, there are some limitations to this study. First of all, the MA is essentially a spatial form, and its construction process is mostly centered on the construction and competition of various types of spaces, so this study analyzes the framework of politics of scale based on the division of spatial dimensions. In fact, there are different analytical frameworks and ideas of politics of scale that are available. For example, there are the “scale frames and counter-scale frames” proposed by Kurtz [44], based on collective action theory, and Underthun developed the idea of politics of scale based on “networks of association” [64]. Therefore, it is necessary to choose the appropriate analytical framework according to the characteristics of scale political events when conducting research. Second, this study mainly focuses on the process of cooperation in the construction of scale politics in CMAs, and the clashes of power between subjects at the same level and between upper and lower levels are not sufficiently discussed. The main reason is that the public data available tend to only present the final results of cooperation, and the details of confrontation and competition between power subjects are less clear. In the future, it is necessary to conduct in-depth field surveys and interviews with subjects at each level to obtain more informative information and to properly analyze the power confrontation process. Finally, this study mainly conducts qualitative analyses based on a theoretical framework and does not apply quantitative methods sufficiently. In fact, power can be measured through econometric models [65]. Therefore, in order to more precisely describe the “strength” of power, future studies should focus on the measurement of power interactions in the construction of CMAs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y. and W.Z.; formal analysis, J.Y. and W.Z.; software, J.Z.; resources, J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y.; writing—review and editing, W.Z. and J.Z.; visualization, J.Z.; project administration J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Meng Zhu at Nankai University for his valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The Nanjing metropolitan area has undergone several rounds of geographic scope changes, the details of which are shown in Table A1.

Table A1.

Changes in the geographical scope of the NMA.

Table A1.

Changes in the geographical scope of the NMA.

| Time Points | Key Events | Member Cities |

|---|---|---|

| 1986 | Establishment of the Nanjing Economic Zone. | “19 cities in Jiangsu, Anhui and Jiangxi”: Nanjing, Zhenjiang, Yangzhou, and Taizhou in Jiangsu; Hefei, Ma’anshan, Wuhu, Huainan, Tongling, Anqing, Huangshan, Chuzhou, Lu’an, Xuancheng, Chaohu and Chizhou in Anhui; Nanchang, Jiujiang and Jingdezhen in Jiangxi. |

| 2000 | The NMA was officially proposed at the Jiangsu City Work Conference. | “6”: Nanjing, Zhenjiang, Yangzhou, Wuhu, Ma’anshan, Chuzhou. |

| 2003 | The NMA Plan (2002–2020) was released. | “6 + 5”: Nanjing, Zhenjiang, Yangzhou, Ma’anshan, Chuzhou, Wuhu, Xuyi County, and Jinhu County in Huai’an, downtown, He County, and Hanyan County in Chaohu. |

| 2013 | The NMA Regional Plan (2012–2020) was released. | “8”: Nanjing, Zhenjiang, Yangzhou, Huai’an, Wuhu, Ma’anshan, Chuzhou, Xuancheng. |

| 2021 | The NMA Development Plan was released. | “8 + 2”: Nanjing, Zhenjiang, Yangzhou, Huai’an, Wuhu, Ma’anshan, Chuzhou, Xuancheng, Changzhou’s Liyang County, and Jintan District. |

Appendix B

After years of continuous exploration, Nanjing metropolitan area has established a multilateral cooperation mechanism of “decision-coordination-executive” in the organizational space. The details are shown in Figure A1.

Figure A1.

Three-level cooperation mechanism of “decision–coordination–executive” in the NMA (modified from [21]).

Figure A1.

Three-level cooperation mechanism of “decision–coordination–executive” in the NMA (modified from [21]).

References

- Gottero, E.; Larcher, F.; Cassatella, C. Defining and Regulating Peri-Urban Areas through a Landscape Planning Approach: The Case Study of Turin Metropolitan Area (Italy). Land 2023, 12, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uto, M.; Nakagawa, M.; Buhnik, S. Effects of Housing Asset Deflation on Shrinking Cities: A Case of the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. Cities 2023, 132, 104062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.G.P.; Lima, C.L.; Saito, C.H. Urban Green Spaces and Social Vulnerability in Brazilian Metropolitan Regions: Towards Environmental Justice. Land Use Policy 2023, 129, 106638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore-Cherry, N.; Kayanan, C.M.; Tomaney, J.; Pike, A. Governing the Metropolis: An International Review of Metropolitanisation, Metropolitan Governance and the Relationship with Sustainable Land Management. Land 2022, 11, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damurski, L.; Andersen, H.T. Towards Political Cohesion in Metropolitan Areas. An Overview of Governance Models. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2022, 15, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei Kwadwo, V.; Skripka, T. Metropolitan Governance and Environmental Outcomes: Does Inter-Municipal Cooperation Make a Difference? Local Gov. Stud. 2022, 48, 771–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strebel, M.A. Who Supports Metropolitan Integration? Citizens’ Perceptions of City-Regional Governance in Western Europe. West Eur. Polit. 2022, 45, 1081–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuirk, P. The Political Construction of the City-Region: Notes from Sydney. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2007, 31, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, F. Rethinking China’s Urban Governance: The Role of the State in Neighbourhoods, Cities and Regions. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2022, 46, 775–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, J.; Albet, A. Urban Governance in Southern Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-315-54885-2. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Shen, J.; Chen, W. Urban Networks and Governance in City-region Planning: State-led Region Building in Nanjing City-region, China. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2010, 92, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Miao, C. Spatial-Temporal Changes and Simulation of Land Use in Metropolitan Areas: A Case of the Zhengzhou Metropolitan Area, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 14089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.; Jiang, C.; Shan-Shan, F. Effects of Urban Growth Boundaries on Urban Spatial Structural and Ecological Functional Optimization in the Jining Metropolitan Area, China. Land Use Policy 2022, 117, 106113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.; Shang, Y.; Yang, Y. Did Highways Cause the Urban Polycentric Spatial Structure in the Shanghai Metropolitan Area? J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 92, 103022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Qian, J.; Wang, L. Village Classification in Metropolitan Suburbs from the Perspective of Urban-Rural Integration and Improvement Strategies: A Case Study of Wuhan, Central China. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Pan, C.; Ling, S.; Li, M. Ecological Efficiency of Urban Industrial Land in Metropolitan Areas: Evidence from China. Land 2022, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.P. Looking for the Global Spaces in Local Politics. Polit. Geogr. 1998, 17, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, S.; Waite, C. Brands of Youth Citizenship and the Politics of Scale: National Citizen Service in the United Kingdom. Polit. Geogr. 2017, 56, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Cuello, M.A.; Pinzon-Salcedo, L.A. A Look at Power Issues in Collaborative Program Evaluations Under Michel Foucault’s Conception of Power-Knowledge. Am. J. Eval. 2022, 41, 109821402110603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Does Power “Spread”? Foucault on the Generalization of Power. Polit. Theory 2022, 50, 553–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chen, W.; Wu, F.; Li, Y.; Sun, W. State-Guided City Regionalism: The Development of Metro Transit in the City Region of Nanjing. Territ. Polit. Gov. 2021, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, E.S.; McMaster, R.B. (Eds.) Scale and Geographic Inquiry: Nature, Society, and Method; Blackwell Pub: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-631-23069-4. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J. Scale, State and the City: Urban Transformation in Post-Reform China. Habitat Int. 2007, 31, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.J. A Materialist Framework for Political Geography. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1982, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E.W. Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory; Nachdr.; Verso: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-86091-936-0. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, K.R. The Problem of Metropolitan Governance and the Politics of Scale. Reg. Stud. 2010, 44, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A. Rethinking Scale as a Geographical Category: From Analysis to Practice. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2008, 32, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.J. Embedded Statism and the Social Sciences 2: Geographies (and Metageographies) in Globalization. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 2000, 32, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N. The Limits to Scale? Methodological Reflections on Scalar Structuration. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2001, 25, 591–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, K.R. Spaces of Dependence, Spaces of Engagement and the Politics of Scale, or: Looking for Local Politics. Polit. Geogr. 1998, 17, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, D.; Leitner, H. The Political Construction of Scale. Polit. Geogr. 1997, 16, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.B. Urban Spatial Restructuring, Event-Led Development and Scalar Politics. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 2961–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Harvey, D. Uneven Development: Nature, Capital, and the Production of Space, 3rd ed.; Verso Books: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-84467-643-9. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N. Contours of a Spatialized Politics: Homeless Vehicles and the Production of Geographical Scale. Soc. Text 1992, 13, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swyngedouw, E. Globalisation or ‘Glocalisation’? Networks, Territories and Rescaling. Camb. Rev. Int. Aff. 2004, 17, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.H. Western Economic Geography in Transformation: Insititutional, Cultural, Relational and Scalar Turns. Hum. Grogr. 2004, 19, 68–76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.G.; Wang, F.L. Politics of Scale in “Sanlu-Milkpowder Scandal”. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2011, 10, 1368–1378. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.L.; Zhang, X.C.; Yang, L.C.; Hong, S.J. Rescaling and Scalar Politics in the‘One Belt, One Road’Strategy. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2016, 36, 502–511. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Shen, J.; Gao, X. Towards a Comprehensive Understanding of Intercity Cooperation in China’s City-Regionalization: A Comparative Study of Shenzhen-Hong Kong and Guangzhou-Foshan City Groups. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H.; Nicholson-Smith, D.; Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; 33. print.; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-631-18177-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.L.; Liu, Y.L. Towards a theoretical framework of ‘politics of scale’. Prog. Geogr. 2017, 36, 1500–1509. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N. Globalisation as Reterritorialisation: The Re-Scaling of Urban Governance in the European Union. Urban Stud. 1999, 36, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarstad, H.; Fløysand, A. Globalization and the Power of Rescaled Narratives: A Case of Opposition to Mining in Tambogrande. Peru. Polit. Geogr. 2007, 26, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, H.E. Scale Frames and Counter-Scale Frames: Constructing the Problem of Environmental Injustice. Polit. Geogr. 2003, 22, 887–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.L. ‘Accidents’ and Invisibilities: Scaled Discourse and the Naturalization of Regulatory Neglect in California’s Pesticide Drift Conflict. Polit. Geogr. 2006, 25, 506–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Stead, D. Understanding the Notion of Resilience in Spatial Planning: A Case Study of Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Cities 2013, 35, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, S.; Kanai, J.M. Getting the Territory Right: Infrastructure-Led Development and the Re-Emergence of Spatial Planning Strategies. Reg. Stud. 2021, 55, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, 2nd ed.; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-679-75255-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Yeh, A.G.O.; Zhang, Y. Political Tournament and Regional Cooperation in China: A Game Theory Approach. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2017, 58, 597–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N. New State Spaces; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-0-19-927005-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kostka, G.; Nahm, J. Central–Local Relations: Recentralization and Environmental Governance in China. China Q. 2017, 231, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-C. Sustainable Territories: Rural Dispossession, Land Enclosures and the Construction of Environmental Resources in China. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 6, 102–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefèvre, C. Constructing Metropolitan Scales: Economic, Political and Discursive Determinants. Territ. Polit. Gov. 2018, 6, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luukkonen, J.; Sirviö, H. The Politics of Depoliticization and the Constitution of City-Regionalism as a Dominant Spatial-Political Imaginary in Finland. Polit. Geogr. 2019, 73, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, A.E.G. City-Regionalism: Questions of Distribution and Politics. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2012, 36, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J. Life after Regions? The Evolution of City-Regionalism in England. Reg. Stud. 2012, 46, 1243–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, F. Understanding City-Regionalism in China: Regional Cooperation in the Yangtze River Delta. Reg. Stud. 2018, 52, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, A.E. China’s Urban Development in Context: Variegated Geographies of City-Regionalism and Managing the Territorial Politics of Urban Development. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wu, F.; Zhang, F. Environmental City-Regionalism in China: War against Air Pollution in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region. Trans. Plan. Urban Res. 2023, 2, 275412232211445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorne, C.; Coleman, A.; McDonald, R.; Walshe, K. Assembling the Healthopolis: Competitive City-regionalism and Policy Boosterism Pushing Greater Manchester Further, Faster. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2021, 46, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrschel, T. Competitiveness AND Sustainability: Can ‘Smart City Regionalism’ Square the Circle? Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 2332–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsmuth, D. Competitive Upscaling in the State: Extrospective City-Regionalism. In Handbook on the Changing Geographies of the State; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 355–367. ISBN 978-1-78897-805-7. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y.; Yu, J. Decentralization and Local Pollution Activities: New Quasi Evidence from China. Econ. Transit. Inst. Chang. 2023, 31, 115–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underthun, A.; Kasa, S.; Reitan, M. Scalar Politics and Strategic Consolidation: The Norwegian Gas Forum’s Quest for Embedding Norwegian Gas Resources in Domestic Space. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr.-Nor. J. Geogr. 2011, 65, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkalitsiou, K.; Kotsopoulos, D. When the Going Gets Tough, Leaders Use Metaphors and Storytelling: A Qualitative and Quantitative Study on Communication in the Context of COVID-19 and Ukraine Crises. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).