Abstract

As global populations rapidly increase, there is a need to maintain sustainable landscapes through innovative agricultural systems and practices that continue to work towards addressing Sustainable Development Goal 2, Zero Hunger. Indigenous people around the world seek culturally appropriate and sustainable livelihood opportunities to improve their socioeconomic status, and there is a rich diversity of existing globally important agricultural heritage systems that have been developed by Indigenous cultures over millennia. Wild harvest of plant products is an innovative agricultural practice which has been conducted by Aboriginal Australians for thousands of years and is a more acceptable form of agriculture on Aboriginal land than more intensive forms, such as horticulture. Wild harvest is typically more culturally appropriate, less intensive, and involves less impact. However, enterprise development programs in Aboriginal communities across Northern Australia have historically had very limited economic success. Such communities often experience high welfare dependency and few economic development opportunities. This research takes a case study approach to explore community views about the development of an Aboriginal plant-based enterprise in the Northern Territory, Australia. We used qualitative methods to engage with community members about their experiences, current attitudes, and future aspirations towards the Enterprise. We found that there was broad support from across all sectors of the community for the Enterprise and clear understanding of its monetary and non-monetary benefits. However, there was limited knowledge of, and involvement in, the business beyond the role of provider and producer, and of the governance aspects of the Enterprise. Using this case study as our focus, we advocate for deeper understanding and stronger inclusion of community aspirations, realities, and perspectives on Aboriginal economic development. Cultural values and knowledge need to inform business development. Additionally, there is a need to invest in basic infrastructure to account for the low base of private asset ownership in this context. A holistic, multifunctional landscape approach is required to support sustainable agricultural practices on Aboriginal lands across Northern Australia.

1. Introduction

Globally, there are over 476 million Indigenous people living in over 90 countries. Although they only make up about 6% of the global population, they account for about 15% of the world’s extreme poor. Furthermore, Indigenous people own, occupy, or use about a quarter of the world’s surface area, and this area is likely to contain much of the world’s remaining biodiversity [1]. Australian Aboriginal people are the custodians of the oldest continuous culture on earth and have an extensive ecological knowledge and deep spiritual connection to their country [2].

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (hereafter referred to as ‘Aboriginal’ or ‘Indigenous’) represent 2.8% of the Australian population. Furthermore, 18.4% of the 649,171 people who identify as being Indigenous live in remote or very remote regions of Australia [3]. In Australia, there has never been a treaty between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, nor was Aboriginal sovereignty ever ceded during colonisation. Despite Australia being considered a developed country, its Aboriginal people suffer from considerable social and economic disadvantage. This is reflected in poor levels of health [4], high unemployment rates [5], and low levels of youth employment and education [6].

The Northern Territory (NT) has a very different demography and land ownership system to other state and territory jurisdictions in Australia, as it was colonised far later than southern parts of the country and has been subject to specific legislation relating to Aboriginal tenure since the 1976. Aboriginal people make up over a quarter of the 228,833 people who live in the NT, and 48.8% live in remote areas [3]. Aboriginal people own over half of the NT land mass and coastal waters, mainly under communal, inalienable titles. This means this land cannot be bought, sold, traded, or given away. Many Aboriginal people reside in townships close to their traditional lands with some people living permanently or seasonally in ‘outstations’, which are smaller settlements on their traditional lands. There are as many as 1200 dispersed Aboriginal settlements of varying size scattered over remote regional Australia [7], and these communities allow residents to remain connected to their traditional lands.

Aboriginal people’s custodianship and management of landscapes, comprised of cultural estates and customary use of natural products over tens of thousands of years [8], can be considered an agricultural practice [9] and can be identified as an agricultural heritage system [10]. Furthermore, customary harvest of plant products, in multifunctional landscapes, could be scaled up to service larger markets while maintaining natural and cultural values [9], via innovative and locally appropriate enterprise models and sustainable agricultural practices.

The approach that the Australian government, the private sector, and other stakeholders have taken in supporting Aboriginal economic development has long been in question [11,12]. There is a substantial body of literature which recommends significant changes in government service delivery, consultation practices, collaborative arrangements, and funding delivery [7,13,14,15]. Conversely, there have also been calls for Aboriginal people to change their lifestyle and better align with mainstream Australian economies [6,16].

There is considerable interest from Aboriginal people in the development of culturally aligned economic development in remote regions of Australia [17,18]. Compared to conventional business development, such economic development requires alternative models of engagement and consultation and consideration of the different barriers and enablers for enterprise development in this context [11,19,20,21]. Even though in recent times there has been greater devolution of power from government to Aboriginal people, the emphasis remains on the colonised people to adapt and adhere to the colonisers’ systems.

This study was situated in an Aboriginal community that has over 15 years of enterprise development experience, based on the wild harvest of fruit from a culturally important tree species on landscapes of traditionally managed cultural estates [19,22,23]. The aim of this research was to identify this community’s aspirations for the future development of this enterprise, in order to ensure that the Enterprise addressed both economic, social, and cultural goals. We use the criteria of Colbourne and Anderson [24], who distinguish value creation of Indigenous enterprises by the need to consider (i) accountability to the Indigenous community within which they are embedded; (ii) leveraging community social and cultural assets through a community-centric approach; (iii) value creation that is cultural appropriate; and (iv) appropriate organisational and governance structures that mobilise community value and/or resources. To do this, we have consulted with ten Clans from the study area about their experiences, perceptions, and priorities for the enterprise development. The findings of this research will assist community members, enterprise service providers, and organisations providing ‘backbone’ support [19] to develop strategies for Aboriginal enterprise development.

1.1. Case Study Context

The case study is based on an Aboriginal-owned and -run business called the ‘Thamarrurr Plum Enterprise’ (hereafter referred to as ‘the Enterprise’). In this section the Enterprise and its origins are described, and community involvement discussed. The analysis presented in this paper draws on empirical data derived from a broader, mixed-method doctoral research project [25], which conducted a business analysis of the Enterprise [22] by identifying its development stages and associated actor roles, and then evaluated the community engagement strategies applied in the Enterprise’s establishment [19]. The following provides contextual information within which to consider the community’s views and aspirations.

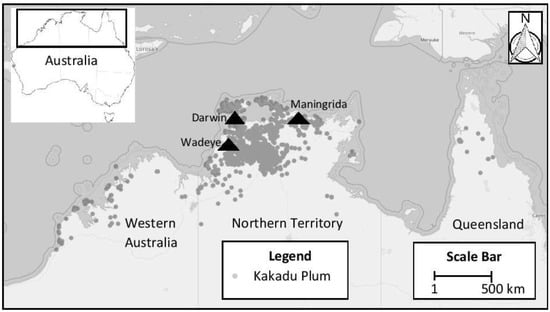

The Thamarrurr Region is an 18,000 km2 area approximately 420 km south-west of Darwin, the capital city of the Northern Territory (NT), Australia (Figure 1). Wadeye is the main township in the Thamarrurr Region and is one of the largest Aboriginal communities in the NT, with a population of 3000 people. There are three ceremony groups and 20 Clans, or traditional land-owning groups, in this region. Traditional Owners are the culturally designated leaders and decision makers for each of these Clans and their estates. Clans also contribute to the governance of the Thamarrurr Development Corporation (TDC). The TDC is the leading community development organisation in the region, and a not-for-profit corporate entity established by the 20 Clans to support economic development [26]. Within the TDC are the Thamarrurr Rangers, an Indigenous land management organisation responsible for operational management of the region’s natural and cultural heritage values in conjunction with the Traditional Owners.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the endemic T. ferdinandiana (as plotted using collection records from [27]). Black triangles represent the approximate locations of Darwin and the Aboriginal Township, Wadeye.

1.2. The Enterprise

The Kakadu plum (Terminalia ferdinandiana) is the basis of a wild harvest enterprise in the Wadeye community [22,23]. In the local language of Murrinh-patha, Kakadu plum is known as mi-marrarrl. It has a long history of wild harvest for customary use, and Aboriginal people have a close affiliation with this species [22,28]. Commercial demand for Kakadu plum is due to its exceptional phytochemical properties which give it numerous applications and market demand from several industry sectors [23]. Kakadu plum fruit has been harvested commercially for over 15 years in the Thamarrurr Region, and the development of the Enterprise has been impacted by a complex combination of social, cultural, economic, ecological, and political factors [22].

Initially, the Enterprise was one of several wildlife-based enterprises that were supported by the Northern Land Council (NLC) in the NT. Land Councils are independent statutory authorities that were established under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (ALRA) and are a Native Title representative body for the purposes of the Native Title Act 1993. The NLC support was through the appointment of a Wildlife Enterprise Development Facilitator in 2005 to help Aboriginal communities develop business acumen and explore wildlife-based enterprise development opportunities (where ‘wildlife’ refers to both plant and animal products). The NLC has a role in approving the commercial harvesting of Kakadu plum on land held under ALRA, under Section 19 of the Act. At a similar time to this, there was a request for supply of Kakadu plum from a Sydney based company, Coradji Pty Ltd. [22]. The NLC supported the Thamarrurr Rangers to trial the harvesting of Kakadu plum to meet the commercial demand from Coradji [29].

1.3. Community Engagement in the Enterprise

There has been a fragmented approach to community engagement for business development within the Wadeye community as the Enterprise has been hosted by different organisations. In 2005, the Thamarrurr Rangers first hosted the wild harvest of Kakadu plum, which was trialled as a part of their land management program. At this time, they were funded through the Federal government’s Community Development Employment Program (CDEP) and supported by the NLC. The CDEP was designed as an income support, community development, employment creation, and enterprise development scheme by the Federal government. It was set up in remote Aboriginal communities in the 1970s and used to employ community members in projects [30]. At this early stage, there was very little community-wide communication about the Enterprise because harvesting activities for commercial purposes were restricted to the Thamarrurr Ranger Program.

In 2007, the funding for the Indigenous Ranger Program changed from the CDEP to a wage-based model, also funded by the Federal government. This meant the management of the Thamarrurr Rangers changed from the Thamarrurr Regional Council to the Thamarrurr Development Corporation (TDC). At this stage, there were extensive community consultations and discussions about the wild harvest of Kakadu plum, and the TDC established a Wildlife Enterprise Centre to host this type of enterprise. In 2011, the TDC provided cash to encourage growth of the Enterprise. The Wadeye community at large was invited to participate in the Kakadu plum harvest and offered immediate payment for fruit collected. With permission from Traditional Owners, hundreds of local Aboriginal people participated in the wild harvest of Kakadu plum from their traditional lands. That season, 2500 kg of fruit was collected [22].

Subsequently, the Thamarrurr Rangers found that they did not have the financial or logistical capacity to manage the Enterprise with this high level of community interest in harvesting. Consequently, they approached an Aboriginal-owned organisation in Wadeye, Palngun Wurnangat Aboriginal Corporation (PWAC), to host the Enterprise. PWAC contracted a business consultant to look at the potential of the Kakadu plum Enterprise and later hosted a meeting of the PWAC Board members to discuss the business, its governance, and aspirations. The PWAC Board responded favourably to the consultant’s Kakadu plum business prospectus, and PWAC took over hosting the Enterprise in 2012/13 and invested in the operational side of this enterprise (e.g., buying equipment, training). PWAC worked with the TDC and the Thamarrurr Rangers to ensure operational procedures were established with the community and social and cultural protocols had high priority.

At this stage, the focus was largely towards deriving social benefits, such as casual employment, income, ability to travel to traditional lands, and intergenerational transfer of knowledge while on country collecting. Consequently, PWAC encouraged community members to wild harvest even though they themselves had not secured market agreements to buy the fruit. This lack of adequate business acumen resulted in the Enterprise being reliant on external sources of funding to pay the upfront operational costs, while large volumes of fruit remained unsold and stored in commercial freezers [22]. However, the Enterprise continued to operate in this way, reliant on external funds, for several years [22]. Eventually, several community meetings were held in 2017 and 2018 to determine community aspirations towards this Enterprise and assess whether it could be governed into the future as a viable business and produce both social and economic outcomes.

In 2018, based on community aspirations, the TDC stepped in again to provide support and to co-host the Enterprise with PWAC. Most importantly, the TDC started focusing on linking with markets and establishing contracts with buyers to purchase fruit, on behalf of community harvesters. The TDC also continued the discussion with the community about community-based options for their greater involvement in the business, beyond the role of harvesters [19].

1.4. Coordination of the Enterprise

Hosting an enterprise such as this one requires substantial financial, social, cultural, and physical capital [31]. There are only a limited number of organisations within a remote Aboriginal community that have the capacity to play such a role. PWAC was hosting the Enterprise and employing staff who were both wild harvesting fruit and handling the incoming fruit. PWAC were focused on the social benefits of the business which included employment and financial benefit to pickers, and sociocultural benefits of being active and working on traditional lands. However, at that point in time, PWAC did not have the capacity or business acumen to connect with the markets and organise sales of fruit, despite there being market interest and demand.

When the TDC linked with PWAC to co-host the business in 2018, they managed to realign the focus on both social and financial outcomes, through confirming community aspirations, aligning with markets and supporting picking operations. In 2022, the TDC continued to have discussions with elders in the community to work towards a community–based framework in which the Enterprise might operate. They have identified several common goals shared by the TDC, PWAC, and the community that they could work together on into the future to continue to sustain and grow this enterprise.

In summary, the main points to come from the empirical data [22] were that the original idea of this Enterprise came from market demand for the fruit and support from the NLC. The Enterprise was initially hosted by the Thamarrurr Rangers, and the community at large were not engaged in the harvest until 2011. Between 2011 and 2018, the Enterprise was managed as a social enterprise with little attention to financial accountability. ln 2018, the TDC took a business-oriented approach to its management and started working with community elders to plan a community-based governance model [19].

We investigated community perceptions of, and aspirations for, the Enterprise in light of these experiences with different governance and enterprise arrangements. We achieved this by speaking with Clan members who harvest Kakadu plum for commercial purposes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Situating the Researchers

One of the researchers has a 15-year association with the community and at the time of the research was a PhD student (J.G.) [25]. Two co-authors were long term staff members at the TDC (M.B. and C.B.). Two co-authors have no direct association with the Thamarrurr Region but were members of the PhD supervisory panel and on the project team because of experience in native plant enterprise development (P.W.) and social science methods (G.E.).

2.2. Case Study Methodology

This research used a case study approach to generate an in-depth understanding of the perspectives, opinion, and aspirations of community members for the development of the Enterprise. It used an ‘embedded’ approach, or mixed-method design, as it contains more than one subunit of analysis [32]: individuals, groups, and community enterprise. This study integrates multiple sources of data including (previously reported) empirical data based on observations [19,25] and new qualitative interview data (group and individual) reported here. Embedding these different sources into one case study enables triangulation among the various sources of data [32,33].

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

To understand community opinions and aspirations for the Enterprise and the basis for decision making, semi-structured interviews of ten Clans and two individuals working within community institutions were conducted. The interviews were considered along with researcher reflections and observations. Similar methods have been used by many other researchers working on Indigenous enterprises [34,35,36].

The semi-structured interviews involved three stages: preparation; implementation (for group and individual interviews), and analysis. The interviews took place in November 2018 in the community of Wadeye, with follow-up discussion of the overall findings at two Kakadu plum Enterprise workshops in August and December 2019.

2.3.1. Preparation

The preparation by the researchers involved long term engagement with the community to identify the main groups and organisations within the Thamarrurr Region that had been involved in this enterprise, understanding the history of the Enterprise’s development, determining the interview questions and methods for different groups (group vs. individual interviews), seeking appropriate Traditional Owner and research ethics authorisation, designing posters and other visual aids to help explain the research project to participants, identifying a suitable venue to conduct interviews, and organising interpreters (as English is only one of multiple languages spoken in the Region) and notetakers to assist in the interviews.

2.3.2. Implementation of Interviews

The main interview procedure was face-to-face dialogue in small groups of members from each Clan. In total, there were ten Clan interviews with a total of 42 participants. Pictures and posters of the Enterprise in operation at important times in its development were used to help inform and facilitate the discussion process. In addition to the group interviews, two individual interviews were undertaken with representatives of two locally owned organisations, located in Wadeye township.

Interviews were semi-structured, and questions were informed by the following pre-determined themes: access, authority, benefits, sustainability, and interest in business development (e.g., new value-adding activities). The first four pre-determined themes related to cultural and operational aspects of the harvest that were known to be important in the long-term engagement of the community [22]. The fifth theme, relating to supply chain participation and value addition, was included to examine community understanding of, and future aspirations for, the Enterprise.

2.3.3. Semi-Structured Group Interviews of Clans

Preparatory consultation pointed to group interviews as the most appropriate method of engaging with individual Clans. Each Clan nominated individuals who they felt were appropriate for an interview, based on their interest and past involvement in the Enterprise. Researchers (a lead interviewer and the note taker) talked to groups from the individual Clans, explained the research context, and secured informed consent for participation in a group interview. Plain English research statements were offered to the group and read aloud as an introduction, explained in the local language, along with a plain English poster using images to explain the research process. Approval to audio tape the interview was sought before each group interview, and in all cases given. The interview questions were translated by members of each group into the local language if requested. Discussions between the group members were encouraged, often in the Clan members’ own language, but the final response was given in English (each interview group included proficient English speakers). We ensured the way the interviews were conducted allowed participants to freely take the conversation in directions they felt were important. This included historical observation and knowledge or feelings about the Enterprise over its entire development since 2005.

2.3.4. Individual Interviews

Two individual semi-structured interviews were conducted by a single interviewer with a non-Indigenous senior staff member from each of two local organisations, Thamarrurr Rangers and Thamarrurr Development Corporation, directly involved in the Enterprise. These are referred to as senior staff members below. The transcripts were sent back to both interviewees to be checked and expanded on. Both consented to being interviewed as representatives of their organisations.

2.3.5. Analysis of Interview Data

Interview data were analysed using a qualitative thematic analysis to identify, analyse, and report on patterns within the data [37]. A deductive approach was the main method used in the analysis undertaken in this research. A deductive approach involves collecting the data based on predetermined themes the researcher is looking for in the data, based on theory or existing knowledge (these themes were noted earlier). An inductive approach [38], involving allowing the data to determine the themes, was also used to determine if information outside of selected themes was being discussed. This was achieved by listening to the audio recordings of the interviews.

2.3.6. Analysis of Semi-Structured Group Interviews of Clans

The Clan interview transcripts were analysed using a coding methodology common to qualitative thematic analysis [38]. Categories defined in the deductive and inductive approaches were compared to ensure all issues raised in the group discussion were captured. Summaries for each Clan group were made in accordance with categories and main points deduced or induced from each group’s data. A summary account of responses for all Clans was then compiled. The results were presented back to the individual Clans in further interviews in August 2019 conducted by the TDC at a Kakadu plum meeting. This meeting was as part of the TDC’s ongoing community development role. This was followed up with a workshop in December 2019 where feedback was given by the lead investigator through an oral presentation along with discussion about subsequent development of the Enterprise since the original interviews.

2.3.7. Analysis of Semi-Structured Individual Interviews

The interviews with the senior staff members were analysed using the coding methodology described above [38]. This information is used to describe how their organisations viewed their role in supporting the future of the Enterprise in the Thamarrurr Region.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Semi-Structured Interviews of Clans

The semi-structured interviews focussed on the following themes: authority, access, benefits, sustainability, business (value adding), and aspirations for future business development. The first four themes were chosen because they relate to the cultural issues associated with resource provision and current operational aspects of the wild harvest. The other two themes, relating to value adding and aspirations for business development, provided information about the community’s vision for the future. Verbatim quotes from Clan interviews have been listed to illustrate themes.

3.1.1. Authority

All the Clans interviewed considered securing permission for harvesting on a Clan estate, from the person or people with authority to grant it, as being central to harvest operations. In most cases it was Traditional Owners who had this authority, although in some Clans other members of the Clan also contributed to this decision. Interviews indicate that permission was freely given in the first instance. Seven of the ten Clans were happy for people from outside their Clan group to pick fruit on their country if they had been given authority from the Traditional Owners. However, two of the remaining groups did not want this to happen, as previously harvesters had cut or damaged trees, resulting in permission being withdrawn. Only one Clan indicated it was not generally permitted from the start. When asked if people breached this protocol by picking from a Clan estate without permission, six Clans indicated that it did not occur because people know the rules, while four indicated that it did happen. In one case it was noted that this caused a ‘fight’ between harvesters and estate owners.

No claim is made on non-Clan harvesters to pay estate owners. The only time payment to a Clan owner by a harvester was mentioned is if that person had not asked for permission to pick.

‘If people go on country and pick without permission, TOs (Traditional Owners) must get money for those plums-need to be strong about this’Clan Rak Yederr

Nine of the ten Clans indicated that the current practices of a pre-season induction workshop, which explains the rules of harvest, was a good idea. It is compulsory for pickers to attend these meetings, where the picking protocols are provided. These protocols had been discussed and agreed upon by Traditional Owners, the TDC, Thamarrurr Rangers, and PWAC. A similar number of groups felt the use of a register to document who had received permission to harvest on each Clan estate was useful. This meant good harvest practice was demonstrated and clearly documented for each Clan estate.

Traditional Owners have an obligation to ‘care for their country’, and many groups confirmed that bad harvest practice, such as cutting or otherwise damaging trees, would not be tolerated, and harvest had been stopped under these circumstances. The words of Traditional Owners (below) illustrate this feeling, which was common among many Clans when trees were deliberately damaged to access fruit. Cutting trees to access fruit was described as ‘wasting’ (Clan Table Hill).

‘Sometimes people go up there (onto Clan estates) without permission, picking and break trees-we will not let people pick if breaking trees’Clan Rak Kungarlbarl

‘If trees being broken or cut, we stop picking, close country down’Clan Rak Nadirri

‘People were cutting trees at … and TOs (Traditional Owners) got sad and angry and closed it down because trees being broken or cut’Clan Rak Kungarlbarl

‘People…feel no good if trees are lying on the ground’Clan Diminin

‘Not good…need to look after trees’Clan Wudapuli-Numa

3.1.2. Access to Picking Sites and to Fruit

Harvested fruit is handled in Wadeye township. Clan estates vary in their distance from Wadeye and in accessibility because of flooding and river crossings. Most Clans identified a lack of transport to their Clan estates as a barrier to accessing fruit and limited the amount of fruit collected. For two of the ten Clans, the roads were mostly too wet for vehicles to get through at the time of year when trees were fruiting. The other eight Clans felt road access was usually not a problem but that often the means of transport to their special picking sites was limited. Two Clans reported that Traditional Owners themselves owned private vehicles and would give a lift to others. Other interviewees reported that Thamarrurr Rangers, the Women’s Centre and TDC staff would use their vehicles to drop off and then return later pick up harvesters. One Clan reported being dropped off by boat and then walking into the picking site. However, getting the harvest back to the pickup site in containers was arduous and a barrier. Some respondents said at times that there were simply no vehicles available to access picking sites.

Only five Clans had harvested fruit in the three seasons prior to the interviews (2015/2016/2018). The reasons given by Clans for not harvesting included roads being flooded, picking areas being closed by Traditional Owners, and mourning responsibilities at the death of a family member. Nine of the ten Clans thought they would pick more fruit if they could get better transport to their picking areas. The words of the Rak Kuy Clan members below were indicative of most Clans.

‘If the creeks were down and there were more cars, lots more people would go out and pick’Clan Rak Kuy

When asked about equipment to access fruit on trees, almost all ten Clans expressed interest in equipment to help. Ideas floated were hooked poles for bending branches close enough to pick from (the most frequently referred to), ladders, trimmers, tree shakers, and mango pickers (there is a well-established mango industry in the NT, and many domestic growers have customised pickers) were all mentioned. One Clan suggested that the community’s Men’s Shed could assist with constructing and designing equipment.

3.1.3. Benefits of Harvesting

Although most Clans reported that picking was hot, hard work, involving getting bitten by green ants, most thought it was good work and something that men, women, and children could all participate in—and ‘as a family’ was often mentioned. Three Clans mentioned it as work being carried out ‘mainly by women’ but that men and children also took part. The main reasons given for enjoying this work were: getting paid for the fruit (even if the actual amount was frequently considered too low), being on their country, creating a healthy activity for children, opportunities for cross generational knowledge sharing, providing an opportunity to collect other bushfoods for consumption, collecting bushfood to take to the elderly people who could not get it themselves. Nine of the ten Clans felt the price they were getting paid was too low and that it needed to increase. Many groups added that not being paid immediately was a disincentive that was stopping some people from picking. Eight of the ten Clans wanted to be paid cash. Two Clans preferred the money being paid into a bank account, so it could be used to cover the expenses (i.e., fuel to drive to Clan estate). Members of the Rak Melpi Clan expressed their feeling about fruit harvesting:

‘Picking Mi-Marrarl is a good, healthy job but it is also hot work, lots of green ants and too low money. We also bring fruit back for old people’Clan Rak Melpi

3.1.4. Sustainability of the Fruit Source

There was some concern about the impact of trees being cut down or damaged, but this was considered a short-term issue as trees were expected to grow back, and picking could be ‘shut down’ for trees to recover (even though that meant not picking). Other than this, there was little concern about the impact of the harvest on the environment as most groups felt there was such a huge number of trees and volume of fruit, and some fruit was always left on the trees. However, there was concern that burning practices, aimed at reducing fuel for later wildfires, affected fruit when it was due to be harvested. Nine Clans commented that early dry-season fires would impact on the fruit, and four Clans thought that fire had a temporary negative impact on larger trees but that most would recover.

‘Early fires effect fruit-helicopter burn. Big fires kill trees’Clan Rak Nadirri

3.1.5. Value Chains and Aspirations for Future Business Development

Clans’ responses to questions about business aspects of the Enterprise indicated that for most Clans, there was very little knowledge about what happened to the fruit once it left Wadeye. This is reflected in the responses below from Rak Kungarlbarl and Rak Kuy Clans.

‘We do not really know (about the industry), but would like to know, what happens with the fruit when it leaves Wadeye’Clan Rak Kungarlbarl

‘We do not really know what happens with the fruit (when it gets sold) but would like to know. We like the idea of value adding’Clan Rak Kuy

All Clans reported that who bought the harvested plums did not matter but that price was more important.

Some participants in one Clan meeting were aware of Kakadu plum’s antimicrobial use to extend the life of cooked prawns. A few community members had been invited to Adelaide, South Australia, a few months before these interviews to the launch of a yogurt by the native foods business, Something Wild Australia [39], which uses Kakadu plum purchased from the Enterprise as an ingredient. The response from Clan Rak Nadirri indicates some knowledge and interest in value adding.

‘Some people know the story about value adding-yogurt, prawns (commercial use). We would like to know about the leaves (commercial use), our people used to eat the sap’Clan Rak Nadirri

Nine of the ten Clans interviewed expressed an interest in value adding and making products in the community. This interest was in relation to employment (in particular for girls and young women by two Clans), intergenerational transfer of knowledge, independence, employment, and pride. The Rangers and PWAC had at various stages in the past experimented with Kakadu plum jam, cordial drink, and soap. The responses from three Clans listed below reflected an overall interest in value adding.

‘Value adding is a good idea-involve young kids and older people helping as well. Young people would be interested in value adding jobs’Clan Rak Kungarlbarl

‘Our group likes the idea of more value adding happening in Wadeye but do not know what this might involve’Clan Rak Kubiyirr

‘Yes, good to be involved in value adding-more money and jobs. This business will go for a long time’Clan Rak Wudapuli

Some Clans remembered the Thamarrurr Rangers pulping the fruit and using it in making soap for its antimicrobial properties.

‘People do not know what happens to the plum. Yes, we would like to see family making things. Rangers used to make soap-this was good. This would be good business, jobs, independence, empowerment’Clan Rak Melpi

‘Like idea of processing. Value adding is good work for girls, making things. Used to like using the pulping machine-making something. Yes, we think this will be a long-term business, need to get younger generations involved’Clan Rak Nadirri

‘We remember when soap making was happening and think this was good. Young people would be interested in this value adding-jobs, can make own money. Think this business will go on for a long time if look after trees’Clan Rak Kuy

These semi-structured interviews have indicated that cultural authority is still very important to Clans. It appears that even though the Clans found harvesting Kakadu plum to be hard work, and even though some did not think they were getting enough payment for the plums, they enjoyed the activity and experienced monetary and many non-monetary benefits from it. They were concerned about the health of their Clan estates and poor harvest practice but did not think the harvest was impacting on sustainability due to the volume of fruit available. There was limited knowledge about what happened to the fruit once it left Wadeye, but most Clans liked the idea of more value adding happening in the community to provide employment for the community. A lack of transport options for accessing harvesting sites and damaging treatment of trees during harvesting, which resulted in estate closures, were identified as impacting the harvest size. In addition, the development of picking tools was thought to potentially increase harvests.

Eight of the ten Clans agreed that the Women’s Centre was the appropriate host organisation and venue for the Enterprise. Two Clans thought the Wildlife Enterprise Centre would be better, one because it is a larger space.

The inductive analysis of interviews, where new themes or discussion points were searched for, did not determine any additional themes to those on which the questions were based. This is understandable given that the interview questions were focused on exploring these specific themes.

3.2. Individual Semi-Structured Interviews

Both non-Indigenous Thamarrurr senior staff members thought that this type of enterprise, based on the harvest of a native fruit with cultural value, was a good business for the region. Senior staff member 2 saw the Thamarrurr Rangers role as being related to the land management implications of wild harvest rather than the commercial aspects. This included contributing to sustainable practice by auditing picking areas for good harvest practice, brokering agreements with Traditional Owners around picking practice, and educating the community about the impacts of poor harvest practices. He thought that if the Enterprise grew into a viable business, these arrangements could be conducted as a fee for service between the Enterprise and the Rangers. Staff recognised that Rangers also needed to liaise with the community about early dry-season burning practice for cultural and management purposes, as the timing of their management burning sometimes overlapped with when fruit was ripe and ready to be picked.

At the time of the interviews in 2018, the TDC was jointly hosting the Enterprise with Palngun Wurnangat Aboriginal Corporation (PWAC). PWAC was without a Manager at the time and unable to host the Kakadu plum Enterprise as they had done since 2013. However, as they had the other PWAC staff trained to handle the harvested fruit and as they housed the equipment (freezers, weighing and packaging equipment), they were still involved in hosting the Enterprise [22]. However, no one from PWAC was appropriate for interview as part of this research project.

Staff member 1 confirmed that their organisation was an incubator for new businesses and supporter of existing businesses in the Thamarrurr region. The TDC considered the Enterprise a priority business because of the overwhelming support for it from the community. Senior staff member 1 thought the Enterprise had potential to be a community-owned and -run business and could grow its capacity to participate in and manage other similar natural resource-based businesses. The value chains established through the Enterprise would make it easier for other products to follow similar routes to commercialisation. The main issues of concern related to the low number of established markets demanding fruit, high turnover of managers in the TDC and PWAC, and issues around conditions of access to land for harvest being controlled by the Northern Land Council (relating to the issuing of permits under Section 19 of the ALRA (NT) 1976). This latter issue can create an additional bureaucratic hurdle for Traditional Owners to access fruit for commercial harvest [23].

Staff member 1 was committed to supporting community interest in future planning for the Enterprise with community members in accordance with community aspirations. At the time of this study, TDC staff were working with Traditional Owners and elders in the community to explore options for how the business could be community-owned and -governed, with the TDC and PWAC supporting the operational side of the business.

In summary, these semi-structured interviews of Clans and support organisations in the Thamarrurr region have clearly identified a community voice with shared aspirations for further progress towards a community-based practice of economic development. Many Clans aspire to be more involved in the supply chain than just participating in a harvesting role. This in turn encouraged commitment from the TDC to initiate discussions with elders to create a community-based structure which would allow community ownership and governance [22].

4. Discussion

This research documents the community views of a plant-based enterprise operating on a landscape comprised of traditionally managed cultural estates. The Enterprise has been operating for more than 15 years in an Aboriginal community, in Northern Australia. Despite this long history and sales to both domestic and export markets, there were two critical barriers identified by the community of harvesters in this study to ongoing commercial development of the Enterprise. Firstly, there is a surprising and ubiquitous lack of knowledge about supply and value chain roles within the supplier community. However, there was awareness among the Clans interviewed about the opportunities presented by greater participation in the value chain, particularly for young women. Addressing this knowledge gap among plum estate owners, harvesters, and Board members, has emerged as a priority for fostering interest and building expertise for decision-making and business development. Secondly, there is a fundamental lack of access to vehicles for the collection of fruit. It would be hard to find a viable primary production enterprise elsewhere in the Australian landscape that operated without vehicles with which to collect and transport fruit within the production site. The lack of vehicles may reflect the lack of private wealth to allow widespread vehicle ownership among harvesters. This situation reflects the expectations and economic realities of remote community life and the common shortcomings that are a barrier to business development [7,11]. These findings point to an important capacity building and infrastructure development role for community institutions in this landscape context.

Building natural resource-based enterprises in remote Aboriginal communities, which are scattered across the vast Northern Australian savannas, is a long, complex process. Critically, there is little exposure to business, the broader Australian economy, and its markets [11,40]. Policy and legislation, government funding and support, land management practices, Indigenous people’s expectations, and intergenerational changes in views, are a few of the many factors that influence business opportunities but that are also in a constant state of change in remote Australian Aboriginal communities [9,41,42,43]. There is a requirement for special long-term training programs, business mentoring and additional support to build the capacity of Aboriginal people in remote communities to participate in their businesses and supply chains by taking additional roles [11]. This is not to suggest that business development should be rushed but that specific barriers should be targeted by community institutions [19].

During the course of the life of this Enterprise, there has been a marked shift in the community’s view of its importance and the community involvement in the Enterprise’s operations. Indigenous people typically want to include a strong focus on cultural and social values into community-based and social enterprises [3,44]. In this case, customary use, which has for many generations involved trade and distribution of excess harvest among other family groups [22,45], has provided a pathway to commercialisation. As a CDEP project, the Enterprise had operated as a ‘social enterprise’ for most of its existence and it was not expected to last past the period of support by the external funding. Normal business planning for financial viability was not occurring [22,46]. Products were not always traded [19]. However, a sustainable Indigenous-led business needs financial viability and business acumen, alongside consideration of social and cultural benefits [11,47]. Recognising this, the TDC introduced greater business acumen into the running of the Enterprise, and it became economically viable while at the same time the TDC started to change its governance structure to enable more community ownership. The community interviews show that Clans have started looking at their long-term involvement in the Enterprise and are thinking of the employment of future generations and their inclusion in all aspects of the business structure. This is an important development in community thinking and an important finding of this research. The TDC’s shift to a more appropriate organisational and governance structure can be seen to be responsible in mobilising community values and resources for business development [24].

Differences in ‘institutional logic’ are thought to be largely responsible for the low engagement of remote Aboriginal communities with business [12,48]. The term ‘institutional logic’ refers broadly to the ‘socially constructed, historical patterns of … practices, assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules’ [49]. Given there are many additional factors that impact on business development in remote Aboriginal communities, their long-term success is even more dependent on good business acumen, planning and communication, as well as alignment with cultural values and priorities. Without these business criteria being incorporated and adapted to local needs, in a way which integrates with Aboriginal world views, the chances of successful business being developed remains low. However, this important work will allow support and enable participation and engagement with business roles.

We found that cultural and business values or priorities were equally important to the harvest community in the conduct of Enterprise activities. Culturally approved resource sharing was not seen as a profit-making opportunity. For example, Traditional Owners did not seek payment or other compensation from pickers who sought appropriate cultural approvals to harvest from their lands. Payment was only sought as a punishment for poor behaviour by pickers. Collecting for family reasons, such as providing for old people no longer well enough to collect themselves or to educate young people, was conducted alongside commercial harvest. Hybrid governance protocols for natural resource use have also emerged to ensure sustainable and appropriately conducted harvest, such as the pre-season induction workshop for authorised harvesters. Given the importance of both cultural and business-facing values for value chain development, it will be important to maintain a space for these values to co-exist in Indigenous enterprises.

Homi Bhabha’s concept of a ‘third cultural space’ [50] may be a useful conceptual tool. A third space is required to develop the mechanisms and language to help create a business that links cultural values with economic development aspirations and also builds links between Indigenous and non-Indigenous partners who may have very different world views or institutional logics. Homi Bhabha [50] first described the term ‘third space’ as the transitional intercultural space between people from differing cultural backgrounds [50,51]. Bhabha [50] described it as the transition space between two or more discourses, conceptualisations, or binaries. Such a space would also subvert post-colonial power relations by creating the opportunity for different knowledge types to come together. Without such a space, partners and individuals are seldom on an equal footing in business development. Therefore, a ‘third space’ [50] is needed in which actors with different cultures, values, and logics can come together to work out overlapping ideals and map out common ground agendas [11,24,47]. There is potential for existing community institutions to provide this space. In this Enterprise the community Women’s Centre has been identified as that safe place.

Thamarrurr Plum Enterprise continues to evolve in response to community aspirations and the demand of markets. Since the community-based consultation reported in this research, the business has pursued a joint venture partnership that involves community members in other aspects of the value chain including production of extracts and marketing. Thamarrurr Plums is also investigating a more mobile collection point in part to address community concern regarding access to harvest areas, damage to trees, and harvest by persons without appropriate permission. The Enterprise has shifted towards a model of community-ownership which is incorporating business values into its governance and operation while at the same time integrating important social and cultural values.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

A key finding of this research is that Aboriginal Clans interviewed in this study are wanting to build business that will persist into the future, for which they have input into all aspects of its design and operation. It also reveals that community cultural authorities see a role in remote Aboriginal Australia for commercial enterprises as being part of the future for economic development, particularly for young people. Building natural resource-based enterprises in remote Aboriginal communities takes time and needs to account for the unique context presented by remoteness, including limited prior exposure to business, the broader Australian economy, and its markets. These factors mean many producer harvesters are not aware of opportunities for value addition, for example. However, this research identifies a requirement for continued and additional support by community institutions in locally customised, long-term training programs, business mentoring, and additional support to build capacity of Aboriginal people in remote communities to take additional roles in businesses and supply chains.

The Northern Territory Government has a strategy for conservation through the sustainable use of wildlife (plant and animals) [52]. This strategy encourages the sustainable use of wildlife for commercial purposes, endorses ecological sustainability, promotes landowners as being the beneficiary of sustainable use of wildlife, and encourages the development of management plans for species to ensure sustainable use [52]. The research presented in this paper has focused on Indigenous enterprise development interests and aspirations as well as concerns around harvest practice and burning regimes. These findings have contributed to the development of a Management Plan for Kakadu Plum 2019–2023 [53] by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, NTG which promotes and supports sustainable use and livelihood opportunities from native plants as sustainable agriculture.

This research supports the fundamental position of both business and social and cultural considerations as central to the success of Aboriginal community-based enterprises. Long-term success and sustainability of agricultural ventures are dependent on good business acumen, planning, and communication with support offered for business development in Aboriginal communities needing to account for both cultural and social and business values.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G., G.E., P.W. and C.B.; methodology, J.G. and M.B.; investigation, J.G. and M.B.; writing of original drafts, J.G., G.E. and P.W.; review and editing, G.E., C.B. and P.W.; supervision, P.W. and C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding and was undertaken as part of a PhD project.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data collected through qualitative methods in this research cannot be shared to protect the identity of interviewees. This was part of the confidentiality agreement stated in the Human Ethics agreement.

Acknowledgments

Charles Darwin University hosted this PhD research. The people and organizations in the Thamarrurr Region that have shared their experiences and perspectives over many years, and for that the authors are grateful.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- The World Bank. Indigenous Peoples Overview. 2020. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/indigenouspeoples (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Rose, D.B. Nourishing Terrains—Australian Aboriginal Views of Landscape and Wilderness; Australian Heritage Commission: Canberra, Australia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics). Census: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Population; ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Mortality and Life Expectancy of Indigenous Australians: 2008 to 2012; (Cat. No. IHW 140); Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M.; Hunter, B. Changes in Indigenous Labour Force Status: Establishing Employment as a Social Norm? Topical Issue No. 7; Working/Technical Paper; Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research: Canberra, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, A. Creating Parity: The Forrest Review; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, M.; Westbury, N. Beyond Humbug: Transforming Government Engagement with Indigenous Australia; Seaview Press: Adelaide, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler, J.M.; Johnston, H.; Olley, J.M.; Prescott, J.R.; Roberts, R.G.; Shawcross, W.; Spooner, N.A. New ages for human occupation and climatic change at Lake Mungo, Australia. Nature 2003, 412, 837–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorman, J.; Griffiths, A.D.; Whitehead, P.J.; Petheram, L. Production from marginal lands: Indigenous commercial use of wild animals in northern Australia. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2008, 15, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shackleton, C.M. Multiple roles of non-timber forest products in ecologies, economies and livelihoods. In Routledge Handbook of Forest Ecology; Peh, K., Corlett, R., Bergeron, Y., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 559–570. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, A.E. Improving business investment confidence in culture-aligned Indigenous economies in remote Australian communities: A business support framework to better inform Government Programs. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2015, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundine, W. Wrong Mr Abbott, Let’s Just Get Down to Business. ABC News. 29 September 2010. Available online: https://mobile.abc.net.au/news/2010-04-30/33878 (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Hunt, J. Engaging with Indigenous Australia—Exploring the Conditions for Effective Relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities; (Issues paper no. 5); Closing the Gap Clearinghouse: Canberra, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, J. Engagement with Indigenous Communities in Key Sectors; (Resource sheet no. 23); Closing the Gap Clearinghouse: Canberra, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Trudgen, R. Why Warriors Lie Down and Die; Aboriginal Resource and Development Services: Darwin, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, N. Up from the Mission: Selected Writings; Black Inc.: Melbourne, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, J. Managing for the Future: A Culture-Based Economy for Northern Australia; Charles Darwin Symposium Series; Charles Darwin University: Darwin, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zander, K.K.; Austin, B.J.; Garnett, S.T. Indigenous peoples’ interest in wildlife-based enterprises in the Northern Territory, Australia. Hum. Ecol. 2014, 42, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, J.T.; Ennis, G. Community engagement in Aboriginal enterprise development—Kakadu plum as a case analysis. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 92, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fordham, A.; Fogarty, W.; Fordham, D.A. The Viability of Wildlife Enterprises in Remote Indigenous Communities of Australia: A Case Study; CAEPR Working Paper No. 63; Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, E.; Jarvis, D.; Maclean, K. The Traditional Owner-Led Bush Products Sector: An Overview; CSIRO: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman, J.T.; Bentivoglio, M.; Brady, C.; Wurm, P.; Vemuri, S.; Sultanbawa, Y. Complexities in developing Australian Aboriginal enterprises based on natural resources. Rangel J. 2020, 42, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, J.; Wurm, P.A.S.; Vemuri, S.; Brady, C.; Sultanbawa, Y. Kakadu Plum (Terminalia ferdinandiana) as a Sustainable Indigenous Agribusiness. Econ. Bot. 2019, 74, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbourne, R.; Anderson, R. (Eds.) Indigenous Wellbeing and Enterprise Self-Determination and Sustainable Economic Development; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman, J.T. Exploring Indigenous Enterprise Development and the Commercial Potential of Terminalia ferdinandiana (Kakadu plum) as an Indigenous Agribusiness across Northern Australia. Ph.D. Thesis, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Australia, May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thamarrurr Development Corporation. About TDC. 2021. Available online: https://thamarrurr.org.au/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Atlas of Living Australia. Mapping and Analysis. 2019. Available online: https://www.ala.org.au/mapping-and-analysis/ (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Raymond, E.; Blutja, J.; Gingina, L.; Raymond, M.; Raymond; Raymond, L.; Brown, J.; Morgan, Q.; Jackson, D.; Smith, N.; et al. Wardaman Ethnobiology; Government Printer of the Northern Territory: Darwin, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, A.B.; Courtenay, K.; Gorman, J.T.; Garnett, S. Eco-enterprises and Kakadu Plum (Terminalia ferdinandiana): “Best laid plans” and Australian policy lessons. Econ. Bot. 2009, 63, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morphy, F.; Sanders, W. (Eds.) The Indigenous Welfare Economy and the CDEP Scheme; CAEPR Research Monograph No. 20; Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Department for International Development. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets; Department for International Development: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, R.W.; Tietje, O. Embedded Case Study Methods: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Knowledge; Sage Publications Inc.: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research, Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2003; ISBN 0-7619-2553-8. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolakis, W. Determinants of success among Indigenous enterprise in the Northern Territory of Australia. J. Aborig. Econ. Dev. 2009, 6, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hindle, K.; Lansdowne, M. Brave spirits on new paths: Toward a globally relevant paradigm of Indigenous entrepreneurship research. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2005, 18, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, D. An examination of Indigenous Australian entrepreneurs. J. Dev. Entrep. 2003, 8, 133–152. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. Qualitative Research: Studying How Things Work; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.R. A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Advertiser. Something Wild Releases Kakadu Plum Yoghurt by Fleurieu Milk Company. 17 November 2018. Available online: https://www.adelaidenow.com.au/delicious-sa/something-wild-releases-kakadu-plum-yoghurt-by-fleurieu-milk-company/news-story/338069d88081b304300053da1e255d27 (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Loureiro, M.L.; McCluskey, J.J. Assessing consumer response to protected geographical identification labelling. Agribusiness 2000, 16, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, J.C. Bawinanga and CDEP: The Vibrant Life, and Near Death, of a Major Aboriginal Corporation in Arnhem Land. In Better Than Welfare? Work and Livelihoods for Indigenous Australians after CDEP; Jordan, K., Ed.; Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University Press: Canberra, Australia, 2016; pp. 175–218. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman, J.T.; Griffiths, A.D.; Whitehead, P.J. An analysis of the use of plant products for commerce in remote aboriginal communities of Northern Australia. Econ. Bot. 2006, 60, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, J.; Pearson, D.; Wurm, P. Old ways, new ways—Scaling up from customary use of plant products to commercial harvest taking a multifunctional, landscape approach. Land 2020, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahn, M. Indigenous entrepreneurship, culture and microenterprise in the Pacific Islands: Case studies from Samoa. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2008, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemuri, S.; Gorman, J. Poverty Alleviation in Indigenous Australia. Int. J. Environ. Cult. Econ. Soc. Sustain. 2012, 8, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valchovska, S.; Watts, G. Interpreting community-based enterprise: A case study from rural Wales. J. Soc. Entrep. 2016, 7, 211–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.; Dana, L.; Dana, T. Indigenous land rights, entrepreneurship, and economic development in Canada: “Opting-in” to the global economy. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L. Opportunities, impediments and capacity building for enterprise development by Australian Aboriginal communities. J. Aborig. Econ. Dev. 2007, 5, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, P.; Ocasio, W. Institutional logics and the historical contingency of power in organizations: Executive succession in the higher education publishing industry. Am. J. Sociol. 1999, 105, 801–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhabha, H.K. The Location of Culture; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, M. Crossing Cultural Borders–A Journey Towards Understanding and Celebration in Aboriginal Australian and Non-Aboriginal Australian Contexts. Ph.D. Thesis, Curtin University, Perth, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- PWCNT. A Strategy for Conservation through the Sustainable Use of Wildlife in the Northern Territory of Australia; Parks and Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory, Northern Territory Government: Darwin, Australia, 1997; Available online: https://www.aquagreen.com.au/files/strategy_for_conservation_through_sustainable_utilisation_of_wildlife.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Gorman, J.T.; Brady, C.; Clancy, T.F. Management Program for Terminalia ferdinandiana in the Northern Territory of Australia 2019–2023; Northern Territory Department of Environment and Natural Resources: Darwin, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).