Land Certificated Program and Farmland “Stickiness” of Rural Labor: Based on the Perspective of Land Production Function

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

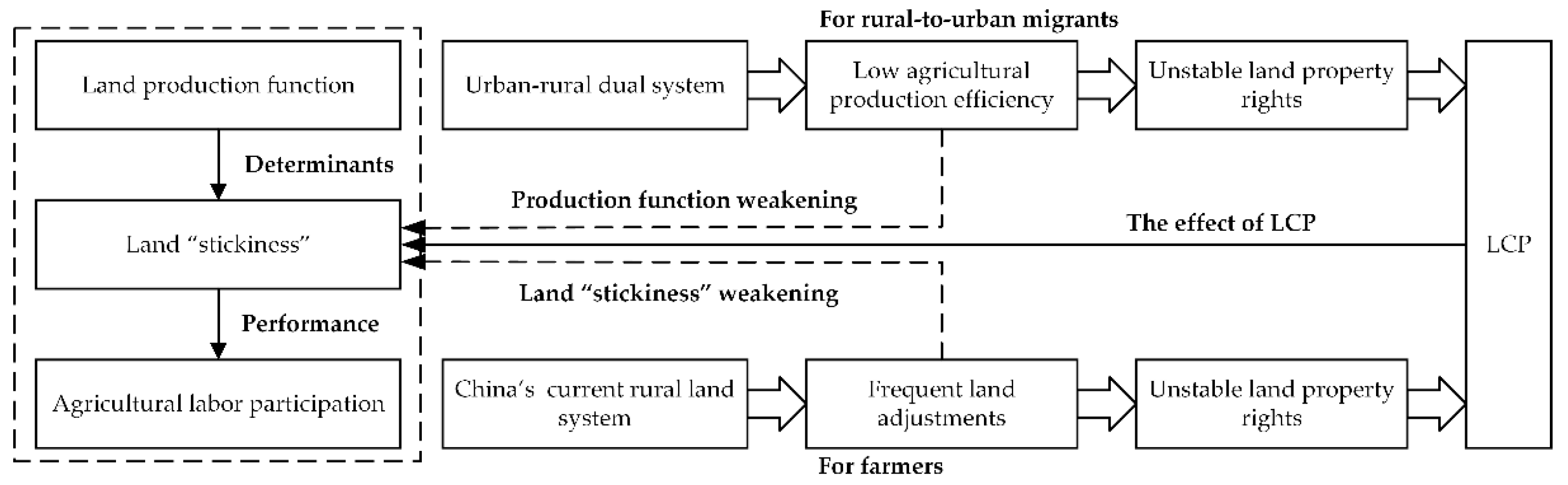

3. Theoretical Framework

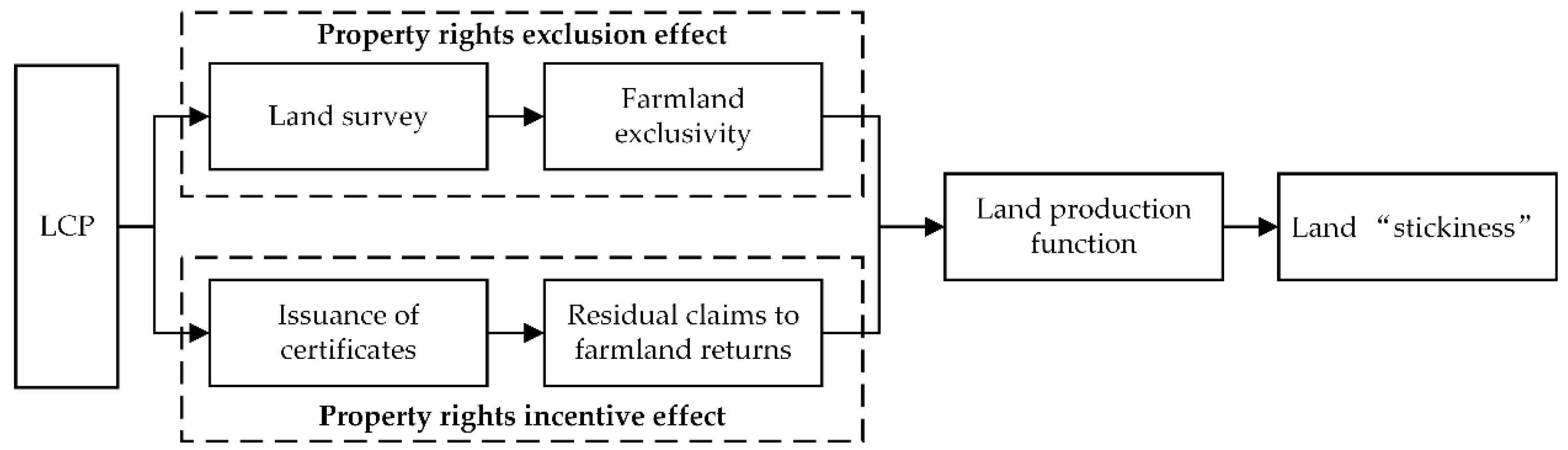

3.1. Property Rights Exclusion Effect, Land Production Function, and Land “Stickiness”

3.2. Property Rights Incentive Effect, Land Production Function, and Land “Stickiness”

4. Data, Variables, and Models

4.1. Data

4.2. Variables

4.3. Models

4.3.1. Propensity Score Matching (PSM) Method

4.3.2. Mediation Effect Model

5. Analysis and Results

5.1. The Estimation Results of the PSM Model

5.1.1. Propensity Score Estimation

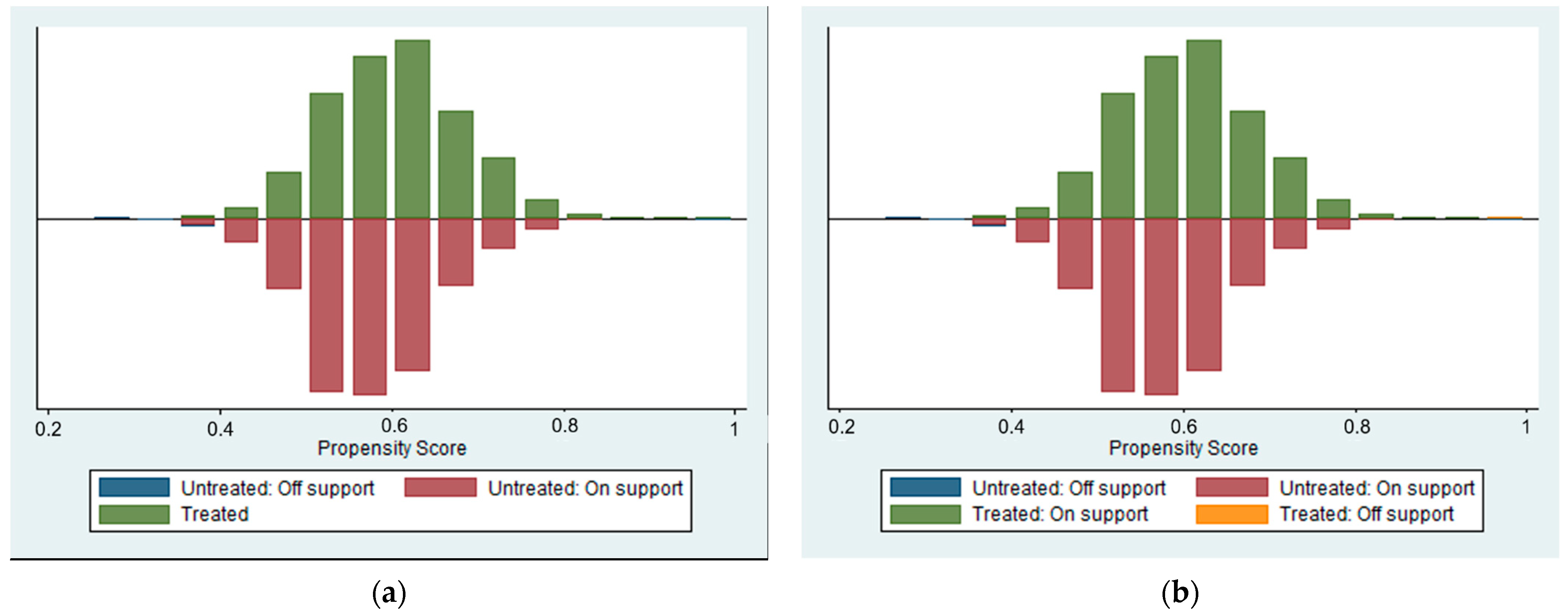

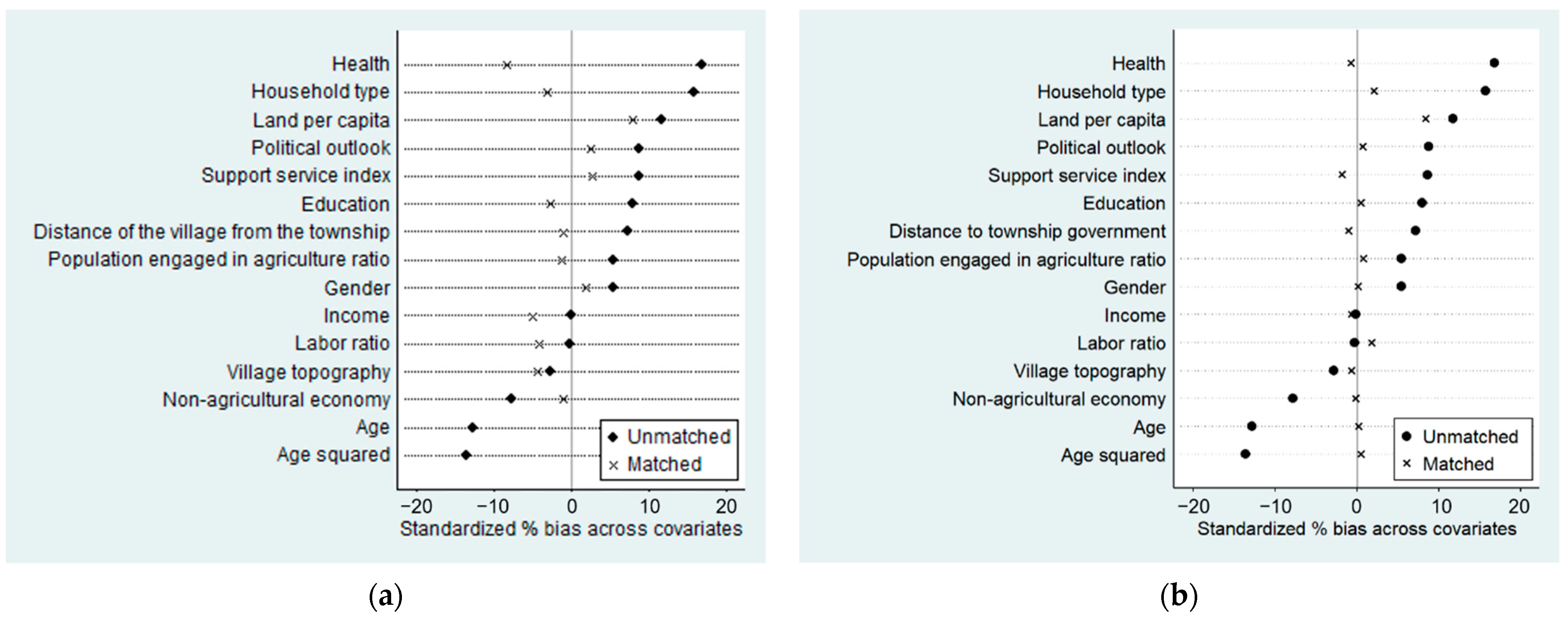

5.1.2. Matching Quality Tests: Common Support Test and Balance Test

5.1.3. Analysis of Matching Results

5.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.3. Robustness Tests

5.3.1. Robustness Test I: Sensitivity Analysis

5.3.2. Robustness Test II: Replacement of LCP Variables

5.4. Mechanism Analysis: How LCP Affect Land “Stickiness”

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Policy Implications

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, S.; Wang, Y. From Native Rural China to Urban-Rural China: The Rural Transition Perspective of China Transformation. J. Manag. World 2018, 34, 128–146, 232. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, B. A Field of One’s Own: Gender and Land Rights in South Asia; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. Land Issues in Urban-Rural China. J. Peking Univ. 2018, 55, 79–93. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Carter, M.R.; Yao, Y. Dimensions and Diversity of Property Rights in Rural China: Dilemmas on the Road to Further Reform. World Dev. 1998, 26, 1789–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leight, J. Reallocating Wealth? Insecure Property Rights and Agricultural Investment in Rural China. China Econ. Rev. 2016, 40, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Heerink, N.; Wang, W. Land Administration Reform in China: Its Impact on Land Allocation and Economic Development. Land Use Policy 1995, 12, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, L.; Huang, J.; Li, G.; Rozelle, S. Land Rights in Rural China: Facts, Fictions and Issues. China J. 2002, 47, 67–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Zhu, X.; Heerink, N.; Feng, S.; van Ierland, E.C. Persistence of Land Reallocations in Chinese Villages: The Role of Village Democracy and Households’ Knowledge of Policy. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.-Y. Two-Tier Land Tenure System and Sustained Economic Growth in Post-1978 Rural China. World Dev. 1996, 24, 915–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latruffe, L.; Piet, L. Does Land Fragmentation Affect Farm Performance? A Case Study from Brittany, France. Agric. Syst. 2014, 129, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, S.; Yohannes, H. Land Redistribution, Tenure Insecurity, and Intensity of Production: A Study of Farm Households in Southern Ethiopia. Land Econ. 2002, 78, 573–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Ma, X.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, X.; Ma, J. Social Relations, Public Interventions and Land Rent Deviation: Evidence from Jiangsu Province in China. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minale, L. Agricultural Productivity Shocks, Labour Reallocation and Rural–Urban Migration in China. J. Econ. Geogr. 2018, 18, 795–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Land Titling Program and Farmland Rental Market Participation in China: Evidence from Pilot Provinces. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Shi, F. Several Important Questions in Rural Land Certification in China. Southeast Acad. Res. 2012, 4, 4–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Shi, X.; Fang, S. Property Rights and Misallocation: Evidence from Land Certification in China. World Dev. 2021, 147, 105632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Bai, Y.; Sun, M.; Xu, X.; Fu, C.; Zhang, L. Experience and Lessons from the Implementing of the Latest Land Certificated Program in Rural China. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Mi, Y. Land Titling and Internal Migration: Evidence from China. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 105763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wu, Y.; Chen, L. Does the Land Titling Program Promote Rural Housing Land Transfer in China? Evidence from Household Surveys in Hubei Province. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawry, S.; Samii, C.; Hall, R.; Leopold, A.; Hornby, D.; Mtero, F. The Impact of Land Property Rights Interventions on Investment and Agricultural Productivity in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2014, 10, 1–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkomoki, W.; Bavorová, M.; Banout, J. Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices and Food Security Threats: Effects of Land Tenure in Zambia. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singirankabo, U.A.; Ertsen, M.W.; van de Giesen, N. The Relations between Farmers’ Land Tenure Security and Agriculture Production. An Assessment in the Perspective of Smallholder Farmers in Rwanda. Land Use Policy 2022, 118, 106122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogelman, C.; Bassett, T.J. Mapping for Investability: Remaking Land and Maps in Lesotho. Geoforum 2017, 82, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senda, T.S.; Robinson, L.W.; Gachene, C.K.K.; Kironchi, G. Formalization of Communal Land Tenure and Expectations for Pastoralist Livelihoods. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brottem, L.V.; Ba, L. Gendered Livelihoods and Land Tenure: The Case of Artisanal Gold Miners in Mali, West Africa. Geoforum 2019, 105, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao Yang, D. China’s Land Arrangements and Rural Labor Mobility. China Econ. Rev. 1997, 8, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, K.; Grosjean, P.; Kontoleon, A. Land Tenure Arrangements and Rural–Urban Migration in China. World Dev. 2011, 39, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, J.; Mu, R. Village Political Economy, Land Tenure Insecurity, and the Rural to Urban Migration Decision: Evidence from China. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2018, 100, 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Luo, B.; Hu, X. Land Titling, Land Reallocation Experience, and Investment Incentives: Evidence from Rural China. Land Use Policy 2020, 90, 104271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y. The System of Farmland in China: An Analytical Framework. Soc. Sci. China 2000, 2, 54–65, 206. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Galiani, S.; Schargrodsky, E. Property Rights for the Poor: Effects of Land Titling. J. Public Econ. 2010, 94, 700–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Human Capital Externalities and Rural–Urban Migration: Evidence from Rural China. China Econ. Rev. 2008, 19, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. The Effect of Land Entitlement on Non-Agricultural Labor Participation. Econ. Sci. 2020, 1, 113–126. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Ali, D.A.; Alemu, T. Impacts of Land Certification on Tenure Security, Investment, and Land Market Participation: Evidence from Ethiopia. Land Econ. 2011, 87, 312–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P. The ‘Credibility Thesis’ and Its Application to Property Rights: (In)Secure Land Tenure, Conflict and Social Welfare in China. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, H.T.; Lyne, M.; Ratna, N.; Nuthall, P. Drivers of Transaction Costs Affecting Participation in the Rental Market for Cropland in Vietnam. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2016, 60, 476–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markussen, T.; Tarp, F. Political Connections and Land-Related Investment in Rural Vietnam. J. Dev. Econ. 2014, 110, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Luo, B.; Boris Choy, S.T.; Li, Y.; He, Q. Do Land Renting-in and Its Marketization Increase Labor Input in Agriculture? Evidence from Rural China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, L. Land Rights and Investment Incentives: Evidence from China’s Latest Rural Land Titling Program. Land Use Policy 2022, 117, 106126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.; Ren, Y.; Rong, K.; Zhou, J. Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture and Household Food Insecurity: Evidence from Azad Jammu & Kashmir (AJK), Pakistan. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierotti, R.S.; Friedson-Ridenour, S.; Olayiwola, O. Women Farm What They Can Manage: How Time Constraints Affect the Quantity and Quality of Labor for Married Women’s Agricultural Production in Southwestern Nigeria. World Dev. 2022, 152, 105800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S. Land Rental, off-Farm Employment and Technical Efficiency of Farm Households in Jiangxi Province, China. NJAS—Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2008, 55, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xie, H.; Yao, G. Impact of Land Fragmentation on Marginal Productivity of Agricultural Labor and Non-Agricultural Labor Supply: A Case Study of Jiangsu, China. Habitat Int. 2019, 83, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L. The Effect of the New Rural Social Pension Insurance Program on the Retirement and Labor Supply Decision in China. J. Econ. Ageing 2018, 12, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, J.; Rozelle, S. Employment, Emerging Labor Markets, and the Role of Education in Rural China. China Econ. Rev. 2002, 13, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brauw, A.; Rozelle, S. Reconciling the Returns to Education in Off-Farm Wage Employment in Rural China. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2007, 12, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Giles, J.; Rozelle, S. Does It Pay to Be a Cadre? Estimating the Returns to Being a Local Official in Rural China. J. Comp. Econ. 2012, 40, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, G. Does Guanxi Matter to Nonfarm Employment? J. Comp. Econ. 2003, 31, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atamanov, A.; Van den Berg, M. Participation and Returns in Rural Nonfarm Activities: Evidence from the Kyrgyz Republic. Agric. Econ. 2012, 43, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Rommel, J.; Feng, S.; Hanisch, M. Can Land Transfer through Land Cooperatives Foster Off-Farm Employment in China? China Econ. Rev. 2017, 45, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Heerink, N. Are Farm Households’ Land Renting and Migration Decisions Inter-Related in Rural China? NJAS—Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2008, 55, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornbeck, R.; Naidu, S. When the Levee Breaks: Black Migration and Economic Development in the American South. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 963–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonasson, E.; Helfand, S.M. How Important Are Locational Characteristics for Rural Non-Agricultural Employment? Lessons from Brazil. World Dev. 2010, 38, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Liu, S.; Xu, D. Gender Difference in Time-Use of off-Farm Employment in Rural Sichuan, China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest Zhang, Q.; Donaldson, J.A. From Peasants to Farmers: Peasant Differentiation, Labor Regimes, and Land-Rights Institutions in China’s Agrarian Transition. Polit. Soc. 2010, 38, 458–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, P. When Can You Safely Ignore Multicollinearity? Available online: https://statisticalhorizons.com/multicollinearity/ (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Opler, T.; Pinkowitz, L.; Stulz, R.; Williamson, R. The Determinants and Implications of Corporate Cash Holdings. J. Financ. Econ. 1999, 52, 3–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Jin, S.; Wang, H.; Ye, C. Estimating Effects of Cooperative Membership on Farmers’ Safe Production Behaviors: Evidence from Pig Sector in China. Food Policy 2019, 83, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.R. Observational Studies; Springer Series in Statistics; Springer: New York, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, L.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, Y. Land Certificate, Heterogeneity and Land Transfer: An Empirical Study Based on 2018 “Thousand Students, Hundred Villages” Rural Survey. J. Public Manag. 2021, 18, 151–164, 176. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Yang, H.; Zheng, H. The Impact of Land Titling on Agricultural Investment in Rural China. Econ. Res. J. 2020, 55, 156–173. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- de Janvry, A.; Emerick, K.; Gonzalez-Navarro, M.; Sadoulet, E. Delinking Land Rights from Land Use: Certification and Migration in Mexico. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 3125–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. The Mechanisms of Governance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, L.; Lu, H.; Gao, Q.; Lu, H. Household-Owned Farm Machinery vs. Outsourced Machinery Services: The Impact of Agricultural Mechanization on the Land Leasing Behavior of Relatively Large-Scale Farmers in China. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 106008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Types | Variable Names | Variable Definitions | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Land “stickiness” | The ratio of labor participating in farming activities (%) | 0.443 | 0.248 | 0 | 1 |

| Independent variable | LCP | 1 if a farmer owns a land certificate, and 0 otherwise | 0.593 | 0.491 | 0 | 1 |

| Individual characteristics | Gender | 1 if the head of household is male, and 0 otherwise | 0.869 | 0.337 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | Age of the head of household (years) | 53.877 | 10.915 | 18 | 89 | |

| Age squared | Age ∗ Age/100 (years) | 30.219 | 11.863 | 3.24 | 79.21 | |

| Education | Years of formal education of the head of household (years) | 7.186 | 3.154 | 0 | 16 | |

| Political outlook | 1 if the head of household is party member, and 0 otherwise | 0.083 | 0.276 | 0 | 1 | |

| Health | 1 if the head of household is healthy, and 0 otherwise | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 | |

| Household characteristics | Income | Total household income in 2015 or 2017 (yuan, logarithm) | 9.709 | 1.853 | 0 | 14.914 |

| Land per capita | The ratio of the farmland size and the number of family members (mu) | 2.533 | 7.124 | 0.01 | 250 | |

| Labor ratio | Share of labor population aged 15–64 | 0.810 | 0.315 | 0 | 1 | |

| Household type | 1 if the household is professional, and 0 otherwise | 0.104 | 0.306 | 0 | 1 | |

| Village characteristics | Population engaged in agriculture ratio | The ratio of the village population engaged in agriculture (%) | 71.919 | 31.084 | 0 | 100 |

| Non-agricultural economy | 1 if the village has non-agricultural economic, and 0 otherwise | 0.182 | 0.386 | 0 | 1 | |

| Support service index | The total number of farmers enjoying village support services | 2.090 | 1.396 | 0 | 6 | |

| Distance of the village from the township | The distance of the village from the township government (km) | 6.330 | 5.936 | 0 | 50 | |

| Village topography | 1 if the village is plain, and 0 otherwise | 0.477 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Variable Types | Variable Names | LCP | Non-LCP | Diff: (1)-(2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |||

| Dependent variables | Land “stickiness” | 0.468 (0.255) | 0.407 (0.232) | 0.061 *** |

| Individual characteristics | Gender | 0.877 (0.329) | 0.858 (0.349) | 0.019 * |

| Age | 53.307 (10.701) | 54.710 (11.170) | −1.403 *** | |

| Age squared | 29.561 (11.537) | 31.178 (12.263) | −1.618 *** | |

| Education | 7.288 (3.129) | 7.037 (3.185) | 0.251 ** | |

| Political outlook | 0.093 (0.290) | 0.069 (0.253) | 0.024 *** | |

| Health | 0.534 (0.499) | 0.450 (0.498) | 0.084 *** | |

| Household characteristics | Income | 9.708 (1.941) | 9.710 (1.717) | −0.002 |

| Land per capita | 2.886 (5.827) | 2.020 (8.650) | 0.866 *** | |

| Labor ratio | 0.810 (0.305) | 0.811 (0.329) | −0.001 | |

| Household type | 0.123 (0.329) | 0.076 (0.265) | 0.047 *** | |

| Village characteristics | Population engaged in agriculture ratio | 72.614 (30.570) | 70.905 (31.800) | 1.710 * |

| Non-agricultural economy | 0.170 (0.376) | 0.200 (0.400) | −0.030 ** | |

| Support service index | 2.139 (1.376) | 2.018 (1.423) | 0.121 *** | |

| Distance of the village from the township | 6.501 (6.203) | 6.154 (5.516) | 0.422 ** | |

| Village topography | 0.471 (0.499) | 0.485 (0.500) | −0.014 | |

| Observation | 2335 | 1601 | — |

| Variable Types | Variable Names | Logit | Marginal Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | ||

| Individual characteristics | Gender | 0.086 | 0.100 | 0.020 | 0.023 |

| Age | 0.058 ** | 0.024 | 0.014 ** | 0.006 | |

| Age squared | −0.060 *** | 0.022 | −0.014 *** | 0.005 | |

| Education | 0.006 | 0.011 | 0.001 | 0.003 | |

| Political outlook | 0.310 ** | 0.127 | 0.073 ** | 0.030 | |

| Health | 0.311 *** | 0.069 | 0.073 *** | 0.016 | |

| Household characteristics | Income | −0.020 | 0.019 | −0.005 | 0.004 |

| Land per capita | 0.028 *** | 0.009 | 0.007 *** | 0.002 | |

| Labor ratio | −0.100 | 0.110 | −0.024 | 0.026 | |

| Household type | 0.480 *** | 0.116 | 0.113 *** | 0.027 | |

| Village characteristics | Population engaged in agriculture ratio | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Non-agricultural economy | −0.172 ** | 0.087 | −0.040 ** | 0.020 | |

| Support service index | 0.091 *** | 0.024 | 0.021 *** | 0.006 | |

| Distance to township government | 0.013 ** | 0.006 | 0.003 ** | 0.001 | |

| Village topography | −0.115 * | 0.069 | −0.027 * | 0.016 | |

| Constant | −1.313 ** | 0.653 | — | — | |

| Variables | Unmatched Matched | Nearest Neighbor Matching | Kernel-Based Matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias (%) | |Bias| Reduction (%) | t-test (p>|t|) | Bias (%) | |Bias| Reduction (%) | t-test (p > |t|) | ||

| Individual characteristics | |||||||

| Gender | U | 5.4 | 0.092 * | 5.4 | 0.092 * | ||

| M | 1.9 | 65.2 | 0.509 | 0.2 | 96.5 | 0.946 | |

| Age | U | −12.8 | 0.000 *** | −12.8 | 0.000 *** | ||

| M | 4.8 | 62.6 | 0.090 * | 0.3 | 98.0 | 0.927 | |

| Age squared | U | −13.6 | 0.000 *** | −13.6 | 0.000 *** | ||

| M | 5.2 | 61.9 | 0.061 * | 0.5 | 96.3 | 0.858 | |

| Education | U | 8.0 | 0.014 ** | 8.0 | 0.014 ** | ||

| M | −2.8 | 64.7 | 0.322 | 0.5 | 96.6 | 0.859 | |

| Political outlook | U | 8.7 | 0.008 *** | 8.7 | 0.008 *** | ||

| M | 2.4 | 73.0 | 0.442 | 0.8 | 91.2 | 0.804 | |

| Health | U | 16.8 | 0.000 *** | 16.8 | 0.000 *** | ||

| M | −8.5 | 49.3 | 0.004 *** | −0.7 | 95.8 | 0.809 | |

| Household characteristics | |||||||

| Income | U | −0.1 | 0.968 | −0.1 | 0.968 | ||

| M | −5.1 | −3786.9 | 0.071 * | −0.7 | −394.1 | 0.826 | |

| Land per capita | U | 11.7 | 0.000 *** | 11.7 | 0.000 *** | ||

| M | 7.9 | 32.7 | 0.000 *** | 8.4 | 28.5 | 0.000 *** | |

| Labor ratio | U | −0.3 | 0.938 | −0.3 | 0.938 | ||

| M | −4.3 | −1606.5 | 0.128 | 1.8 | −630.5 | 0.520 | |

| Household type | U | 15.8 | 0.000 *** | 15.8 | 0.000 *** | ||

| M | −3.3 | 79.1 | 0.314 | 2.1 | 86.8 | 0.513 | |

| Village characteristics | |||||||

| Population engaged in agriculture ratio | U | 5.5 | 0.090 * | 5.5 | 0.090 * | ||

| M | −1.3 | 76.0 | 0.647 | 0.8 | 84.5 | 0.770 | |

| Non-agricultural economy | U | −7.8 | 0.015 ** | −7.8 | 0.015 ** | ||

| M | −1.2 | 84.5 | 0.670 | −0.2 | 98.0 | 0.956 | |

| Support service index | U | 8.6 | 0.008 *** | 8.6 | 0.008 *** | ||

| M | 2.6 | 70.2 | 0.388 | −1.8 | 79.2 | 0.548 | |

| Distance to township | U | 7.2 | 0.029 ** | 7.2 | 0.029 ** | ||

| M | −1.2 | 83.4 | 0.706 | −1.0 | 85.7 | 0.736 | |

| Village topography | U | −2.8 | 0.380 | −2.8 | 0.380 | ||

| M | −4.5 | −56.5 | 0.128 | −0.6 | 78.4 | 0.834 | |

| Matching Methods | Unmatched Matched | Mean | ATT | SE | T Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | C | |||||

| Nearest neighbor matching | U | 0.468 | 0.407 | 0.061 *** | 0.008 | 7.65 |

| M | 0.468 | 0.419 | 0.049 *** | 0.010 | 4.70 | |

| Kernel-based matching | U | 0.468 | 0.407 | 0.061 *** | 0.008 | 7.65 |

| M | 0.467 | 0.419 | 0.048 *** | 0.008 | 5.95 | |

| Matching Methods | Unmatched Matched | Rural Household Types | Farm Size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PH | NPH | Small | Medium | Large | ||

| Nearest neighbor matching | U | 0.041 (0.027) | 0.061 *** (0.008) | 0.058 *** (0.016) | 0.070 *** (0.012) | 0.036 ** (0.015) |

| M | 0.043 (0.038) | 0.032 *** (0.011) | 0.042 * (0.021) | 0.060 *** (0.015) | 0.032 (0.020) | |

| γ | Sig+ | Sig− | t-hat+ | t-hat− | CI+ | CI− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.4167 | 0.4167 | 0.4167 | 0.4167 |

| 1.1 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.4167 | 0.4167 | 0.4000 | 0.4333 |

| 1.2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.3958 | 0.4333 | 0.3889 | 0.4500 |

| 1.3 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.3875 | 0.4500 | 0.3750 | 0.4500 |

| 1.4 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.3750 | 0.4500 | 0.3750 | 0.4583 |

| 1.5 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.3750 | 0.4583 | 0.3667 | 0.4625 |

| 1.6 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.3667 | 0.4583 | 0.3667 | 0.4762 |

| 1.7 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.3667 | 0.4762 | 0.3500 | 0.5000 |

| 1.8 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.3500 | 0.5000 | 0.3500 | 0.5000 |

| 1.9 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.3500 | 0.5000 | 0.3429 | 0.5000 |

| 2.0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.3485 | 0.5000 | 0.3333 | 0.5000 |

| Matching Methods | Unmatched Matched | Mean | ATT | SE | T Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | C | |||||

| Nearest neighbor matching | U | 0.481 | 0.395 | 0.085 *** | 0.008 | 10.88 |

| M | 0.481 | 0.406 | 0.074 *** | 0.011 | 7.03 | |

| Kernel-based matching | U | 0.481 | 0.395 | 0.085 *** | 0.008 | 10.88 |

| M | 0.481 | 0.407 | 0.074 *** | 0.008 | 8.90 | |

| Variables | Model Ⅰ | Model Ⅱ | Model Ⅲ | Model Ⅳ | Model Ⅴ | Model Ⅵ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land Production Function | Land “Stickiness” | Land Production Function | Land “Stickiness” | Land Production Function | Land “Stickiness” | |

| LCP | 0.629 *** | 0.049 *** | — | — | — | — |

| (0.120) | (0.009) | — | — | — | — | |

| Village level LCP | — | — | 0.957 *** | 0.068 *** | — | — |

| — | — | (0.120) | (0.009) | — | — | |

| Village level LCP rate | — | — | — | — | 1.684 *** | 0.128 *** |

| — | — | — | — | (0.196) | (0.014) | |

| Land production function | — | 0.010 *** | — | 0.010 *** | — | 0.009 *** |

| — | (0.001) | — | (0.001) | — | (0.001) | |

| Individual characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Household characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Village characteristics | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observation | 3915 | 3915 | 3915 | 3915 | 3915 | 3915 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, X.; Zhu, W.; Chen, A.; Yang, G. Land Certificated Program and Farmland “Stickiness” of Rural Labor: Based on the Perspective of Land Production Function. Land 2022, 11, 1469. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11091469

Sun X, Zhu W, Chen A, Yang G. Land Certificated Program and Farmland “Stickiness” of Rural Labor: Based on the Perspective of Land Production Function. Land. 2022; 11(9):1469. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11091469

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Xiaoyu, Weijing Zhu, Aili Chen, and Gangqiao Yang. 2022. "Land Certificated Program and Farmland “Stickiness” of Rural Labor: Based on the Perspective of Land Production Function" Land 11, no. 9: 1469. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11091469

APA StyleSun, X., Zhu, W., Chen, A., & Yang, G. (2022). Land Certificated Program and Farmland “Stickiness” of Rural Labor: Based on the Perspective of Land Production Function. Land, 11(9), 1469. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11091469