1. Introduction

Despite a prolonged period of urbanisation and industrialisation globally, 45% of the world’s people still live in rural areas [

1,

2]. In order to promote the reasonable development of rural areas, countries around the world try to take different measures to guide the spatial layout of rural settlements [

3]. Some European countries have introduced policies such as “multi-functional agriculture” to adjust the rural layout structure so as to achieve balanced development between urban and rural areas; some Asian countries have implemented the “New Village Movement” to alleviate social conflicts and promote the development of rural areas [

4,

5,

6]; However, whether in a developed or developing country, policy implementation may not necessarily achieve the expected goals [

7], and the loopholes in the policy may also lead to unbalanced development in rural areas [

8,

9]. For instance, some countries in South America have experienced “false urbanisation” (referring to the phenomenon of the rural population’s excessive migration to cities, urbanisation that exceeds the national economic development capacity), resulting in an excessive influx of the rural population into cities, and a large number of rural settlements have been abandoned. The formation of huge “slums” has caused a series of social problems [

10]. This experience shows that grasping the changing laws of rural settlements is not only conducive to the rational use of rural land in a region, but also helps to promote the coordinated development of urban and rural areas [

11].

How do we correctly grasp the law of changes in rural settlements and guide their rational layout and development? First, we use remote sensing images to understand the distribution of rural settlements. For example, we found through imagery that rural settlements in the Mayo region of Yukon, Canada, are distributed along the river; the farmland in the Wilson area of Kansas in the western United States is distributed in rectangular blocks, and rural settlements are scattered around the farmland; the farmland in China’s Guanzhong region surrounds rural settlements. Secondly, governments should formulate corresponding policies on rural settlements according to their own national conditions and regulate the layout of rural settlements with policies. Belgium realizes rural revitalization through organic integration of land planning and rural improvement; and the British government has focused on building central villages, thereby promoting the agglomeration of rural population to central villages. Israel has explored the hierarchical service centre model, which allows the size of rural settlements to adjust to changes in agricultural production methods. In China, there is an urgent need to adjust the layout of rural settlements.

In 2020, there were still 510 million people living in rural areas in China, accounting for 36.11% of the country’s total population [

12]. According to China’s third land survey, the rural residential land area was 21.9356 million hectares, accounting for 62.13% of urban villages and industrial and mining land [

13]. China’s rural population accounts for 36.11% of the country’s total population, but it occupies 62.13% of the country’s construction land. In the context of new urbanisation, adjusting the layout of rural settlements is therefore still the top priority. In recent years, with the rapid development of the social economy and the promotion of related policies, the barriers to mobility among the rural population have been gradually broken down, leading to major changes in the pattern of rural settlements [

14,

15]. In order to cope with these changes, it is necessary to analyse the historical evolution law of rural settlements in depth and then guide their rational layout and development according to the law [

16].

Accurate spatial data is the basis for studying the evolution of patterns in rural settlements. Compared with urban land use, rural settlements are smaller and relatively scattered. They are therefore less described in most existing land use maps, and there is no rural settlement type [

17] in many global land use maps. For example, the land use survey classification system proposed by the US Geological Survey is divided into nine categories: urban or construction land, agricultural land, grazing land, woodland, waters, wetlands, wasteland, permafrost, and tundra. Some early studies used Landsat to extract rural settlements. The researchers combined terrestrial satellite data with public auxiliary geospatial data and used geospatial data fusion to map rural residential sites in remote areas [

18]. Some researchers also used the global urban footprint (GUF) to obtain the rural training samples and used the spectral–texture–time information from the Landsat and Sentinel time series to map the rural residential population [

17]. In recent years, many scholars have used SPOT, QuickBird, and other high-resolution images to extract clearer rural settlement data [

3,

19,

20]. In order to extend the time scale of rural residential data acquisition, some scholars have used topographic maps to obtain long-term rural settlement data, but these maps provide less rural settlement information, and the shooting range is limited, so it is difficult to achieve full regional coverage [

21]. There are thus still great challenges facing research into the pattern evolution of rural settlements on the medium and long time scales.

The spatial evolution pattern of rural settlements in different areas often suggests different laws. In short time scales, the size of a rural residential area usually shows a linear trend. For example, from 2009 to 2014, the area of rural settlements in Changchun City showed a decreasing trend [

11]; from 2006 to 2015, the Kangbashi New Area in Inner Mongolia had significant spatial expansion characteristics [

22]; from 2000 to 2018, the scale of residential settlements in Pudong, Shanghai decreased significantly, showing a decreasing trend from the urban-rural fringe to the outer suburbs [

3]; and from 1990 to 2015, the kernel density of rural settlements in Hubei Province decreased, and there were obvious regional differences [

13]. The evolution of rural settlement size is also different in the medium and long time scales due to differences in the development scenarios in different regions. For example, some scholars have used historical data left by social anthropologists to analyse the evolution of rural settlements in Xin He Village, China, from 1949 to the present and found that their changes involved a process from stagnation to disorderly expansion to orderly construction [

23]. Some scholars have studied the changes in rural settlements in Belarus from 1959 to 2009. Their analysis found that changes in population during different periods affected changes in the number of rural settlements. For example, intensive migration outflow was accompanied by the disappearance of a large number of rural settlements. Some scholars have studied changes to rural settlements in different areas at the same time node. Their results showed that the number of rural settlements in some areas has declined continuously in the past 50 years, while the trend of change in rural settlements in other areas is to decrease first and then increase [

24,

25]. The above studies show that changes in the spatial pattern of rural settlements are usually relatively simple on short time scales, while the change trends on medium- and long-term scales are often diverse. It is therefore of profound significance to study the evolution of spatial patterns in rural settlements on a long time scale to grasp the rural development in this area.

There is a close connection between the evolution pattern of rural settlements and policy reform [

26], and rural policy profoundly affects changes to rural settlements [

27,

28]. In the second half of the 20th century, with the acceleration of globalisation and urbanisation, many countries issued policies to plan the development of rural settlements [

7]. The policies of developed countries mainly focused on the centralised layout of rural settlements, the construction of infrastructure, and other aspects of the rationalisation arrangement [

29]. For example, the Japanese village-building movement is characterised by excavating local resources, respecting local characteristics, and using rural resources to develop and promote rural construction. In view of the lack of rural infrastructure and other problems, the UK proposed a village revitalisation pattern focusing on the construction of central villages, and the government formulated a series of policies to promote the concentration of rural settlements in the key development areas designated by the government. In rural France and rural Brazil, agricultural modernisation policies have also caused changes in the local settlement pattern [

10]. In the 1980s, residential concentration policies were implemented almost throughout Central and Eastern Europe (such as Hungary and Poland) to promote the centralised development of rural settlements [

30]. Developing countries have also promulgated various policies to guide the development of rural settlements. For example, Egypt has issued policies since 1996 to encourage people to settle in the arid regions of the eastern and western desert plateaus and to avoid building new buildings in the floodplain of the Nile River [

31]; China implements macropolicies such as “new rural construction” and “new urbanisation” to coordinate urban and rural development and solve problems caused by the layout of some rural settlements [

32,

33].

In our research, we found that some scholars used topographic maps, text data, and so on to study the changes in the scale of early rural settlements, and the scale of rural settlements showed two trends: expansion and shrinkage. For example, from the 1960s to the 1980s, the number of rural settlements in the Tongzhou District of Beijing decreased from 417 to 365, and the number of rural settlements in the Jizhou District decreased from 660 to 497 [

24,

25]. Ownership has greatly hindered the production of farmers, and the construction of rural settlements in Xinhe Village has stalled [

23]. Rural settlements in the Jinzhong Plain of Shanxi Province have been expanding since 1979 [

34].

We found that land institutional change will affect land use change. Identifying policy as one of the main drivers of land-use change and agricultural development, Teka et al. assessed land-use change in northern Ethiopia since the 1960s and found that the land policies of imperial and communist regimes largely promoted arable land. The increase in vegetative land decreases, while in the EPRDF regime, the situation is reversed [

35]. Spalding et al. describe the evolution of land tenure in Panama in terms of development process and land policy in Latin America, arguing that land use policy affects land use change at the local level [

36]. Munteanu et al. integrated historical maps and satellite imagery of the Carpathians region to assess the impact of nineteenth century agricultural land choices on agricultural development today. They concluded that changes in political systems can affect future land use choices [

37]. Wang Juan et al. analysed the dynamics of land policy and land use change in China based on land use data. They found that land use change in China is closely related to changes in government land policy and socioeconomic development [

38].

From the current point of view, China’s successively implemented rural settlement policies have changed significantly over the past 60 years, and homesteads have undergone a transition from private ownership to public ownership. This paper aims to solve the following two questions: (1) Changes in the scale of rural settlements are not clear in the period before remote sensing data, so is the scale of rural settlements expanding or shrinking? (2) The homestead has undergone a transition from private ownership to public ownership, and this change is decisive, so when did changes in the scale of rural settlements become more drastic?

Changes in the pattern of rural settlements have obvious period characteristics. The analysis and study of the evolutionary characteristics of rural settlements on a medium and long time scales can provide an effective basis for the scientific and reasonable planning of rural settlements. Previous researchers have mostly analysed changes in rural settlement patterns under the influence of driving factors such as terrain, water sources, traffic, altitude, and human activities [

39]. There is currently less work on systematically assessing the impact of rural settlement policies in the medium and long-term scales. We have studied changes to rural settlements in some developed and developing countries and found that there is indeed a close connection between the evolutionary pattern of rural settlements and policy reform. Based on the decryption of military satellite images, this study reveals the spatial evolution characteristics of rural settlements in Dingzhou, China from 1962 to 2020 and explores the impact of policies on rural settlements and changes in different periods. The specific purpose of this study was as follows: (1) obtain medium- and long-term historical data for rural settlements in Dingzhou City, China by decrypting military satellite remote sensing images; (2) uncover the spatial evolution characteristics of rural settlements in Dingzhou City from 1962 to 2020; (3) analyse the effect of rural settlement policies on changes in rural settlements patterns in different periods and summarise the evolutionary characteristics of the different stages of rural settlement spatial patterns.

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Policies Affecting the Changes of Rural Settlements and Stages

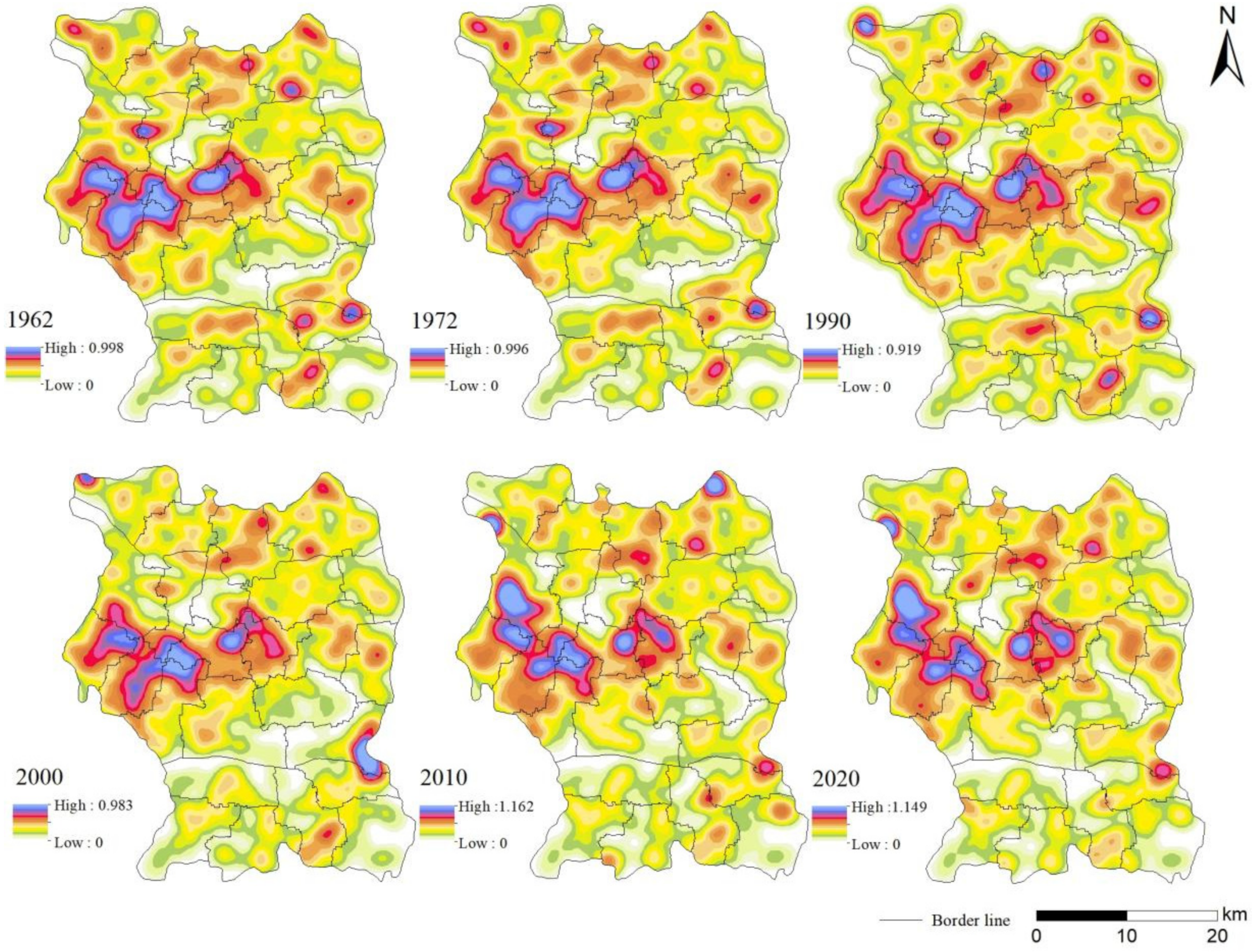

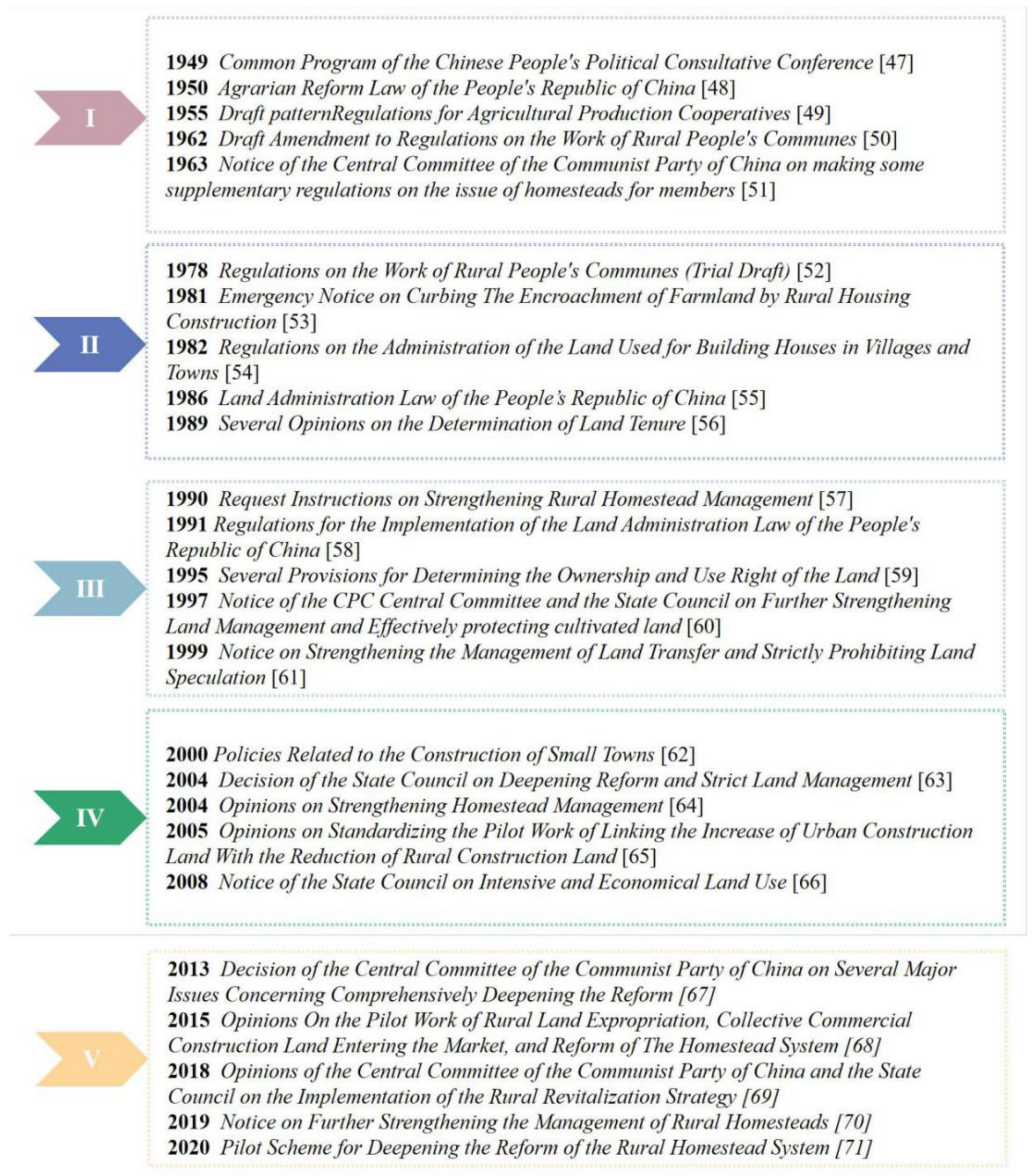

In rural areas of China, the policy for homesteads (land for building rural housing, the main component of rural settlements) profoundly affects rural settlements. The homestead system is an important part of China’s land system. It began during the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Continuous adjustment and improvement meant that it was relatively complete and gradually standardised in the late 1980s. We divided the policies causing changes in the spatial pattern of rural settlements in Dingzhou into five periods (

Figure 8): the period of transition from “private ownership of farmers” to “one homestead, two systems”, the period of the “unified planning” of homesteads, the period of the “paid use” of homesteads, the period of “connecting increase and decrease" in homesteads, and the period of “separation of three rights” of homesteads.

5.1.1. 1949–1972: Period of Transition from “Private Ownership of Farmers” to “One Homestead, Two Systems”

The Common Program of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference adopted in 1949 [

47] proposed that farmers’ land ownership should be protected and that land (including homesteads) should be distributed to farmers free of charge. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, China reformed the rural land system. The Land Reform Law of the People’s Republic of China [

48] promulgated in 1950 proposed the establishment of a privately owned land system by farmers. In 1955, the Draft of the Pattern Constitution of Agricultural Production Cooperatives [

49] stated that means of subsistence were privately owned and that means of production should be gradually nationalised. At this time, as a general rule, farmers were self-employed, and homesteads were distributed evenly and could be obtained free of charge. In 1962, the [

46] established the principle of “one homestead, two systems” (that is, a homestead occupied by farmers for building houses are collectively owned, and the houses built on the homestead are owned by farmers individually) rural homestead pattern. Homesteads were transformed from peasant ownership to rural collective ownership. In 1963, the Circular of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Making Some Supplementary Regulations on the Issue of Homesteads for Members [

50] first proposed the concept of the right to use homesteads. During the period when the private ownership of peasants changed to “one homestead, two systems”, the original ownership of homesteads was changed to a right to use the homestead, beginning the era of the “separation of two rights” of homesteads [

51]. At this time, the framework of China’s homestead system was preliminarily formed. As the concept of the right to use homesteads gradually became clear, the total number of homesteads remained stable.

5.1.2. 1972–1990: Period of “Unified Planning” of Homesteads

The Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee was held in 1978, and the state established a policy of reform and opening up. With the deepening of reforms and opening up and the rapid advances in the marketisation of land, there has been a boom in housing construction in rural areas, and social problems such as speculation in homesteads and the erosion of cultivated land in rural areas have become increasingly serious. Against this background, the State Council promulgated the Regulations on the Administration of Land Use for Villages and Towns in 1982 [

54], which for the first time stipulated a standard area for each household when applying for the right to use the homestead. On this basis, the 1986 Land Administration Law of the People’s Republic of China [

55] made more detailed regulations on the basis of the Regulations on the Administration of Land for Villages and Towns Construction, clearly restricting the occupation of farmland by homesteads. The main feature of this period was the disorderly expansion and controlled adjustment of the total number of homesteads. After the housing boom in rural China, the state intervened in the management of homesteads in a timely manner, and the homestead system was gradually standardised during this period.

5.1.3. 1990–2000: Period of “Paid Use” of Homesteads

In 1990, the Request for Instructions on Strengthening the Management of Homesteads in Rural Areas [

57] first proposed a pilot program for the paid use of homesteads (that is, charging an appropriate amount of fees for homesteads). In 1991, the Regulations for the Implementation of the Land Administration Law of the People’s Republic of China [

58] pointed out that the state manages the legal use of homestead and punishes illegal acts. In 1995, Several Regulations on Determining Land Ownership and Use Rights [

59], stipulations were made regarding the problem of exceeding the standard amount of land occupied by residents for building houses. Since then, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council have issued a notice that the residential construction of rural residents must conform to the village and town construction plan and implement the policy of one house for one household. The state strengthened the management of homesteads during this period, laying the foundation for the subsequent reform of the homestead system.

5.1.4. 2000–2010: Period of “Connecting Increase and Decrease” of Homesteads

After 2000, the central and local governments conducted a large-scale theoretical and practical exploration of the reforms of the homestead system. In 2004, the Decision of the State Council on Deepening Reform and Strict Land Management [

63] encouraged the consolidation of rural construction land and suggested that an increase in urban construction land should be connected to a reduction in rural construction land. In 2008, the Notice of the State Council on Promoting Economised and Intensive Land Use [

66] mentioned that the local government may give incentives or subsidies to villagers who voluntarily vacated their homesteads. Since then, China has stressed the formation of a new pattern of urban and rural economic and social development and integration for the future, and various localities have also intensified the consolidation of rural residential land. The main feature of the reform and exploration period is the reform of the homestead system and the exploration of the exit mechanism for homesteads. The state has also instituted many incentives to encourage farmers to vacate excess homesteads. In addition, the Fifth Plenary Session of the 16th CPC Central Committee proposed building a new socialist countryside, and the implementation of this major strategic measure also provided strong policy support for land use in rural settlements.

5.1.5. 2010–Present: Period of “Separation of Three Rights” of Homesteads

In 2013, the Decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Several Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening the Reform [

67] emphasised that it was necessary to improve the existing pilot projects connecting the increase and decrease of urban and rural construction land. In 2018, the No. 1 Central Document Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on the Implementation of the Rural Revitalisation Strategy [

69] proposed the “separation of three rights” of homestead ownership, contract rights, and management rights. In 2019, the Notice on Further Strengthening the Management of Rural Homesteads [

70] noted that village collectives and farmers should be encouraged to use idle homesteads and houses. In recent years, China has further explored the pilot reform of the rural homestead system, focusing on exploring the “separation of three rights” of homesteads. In the future, under the guidance of the rural revitalisation strategy, the reform of the rural homestead system should make greater breakthroughs in controlling the scale of rural settlements and sorting out rural settlements.

5.2. Impact of Relevant Policies on Changes in Rural Settlements in Dingzhou

5.2.1. Period of Transition from “Private Ownership of Farmers” to “One Homestead, Two Systems”

During this period, the management of rural settlements in China was very strict, the living standards and economic conditions of farmers were relatively low, and farmers’ housing could not be improved for an extended period. The growth of rural housing construction in China was thus very slow. From 1962 to 1972, the area of rural settlements in Dingzhou increased by only 331.92 ha. As the concept of the right to use homesteads was gradually clarified, the total number of homesteads then remained stable during this period.

5.2.2. Period of “Unified Planning” of Homesteads

In 1979, the first national work conference on rural housing construction was held, which reiterated that rural housing involved the means of living and that the property rights of housing should be owned by the members of the community. Since then, China has eased its long-standing controls on rural housing construction. In the 1980s, in order to activate the rural economy and strengthen rural construction, the government formulated some rural policies to relax the application targets for homesteads, resulting in problematic phenomena, such as the random occupation of cultivated land and disorderly expansion of rural housing construction [

72]. During this period, the area of rural settlements in Dingzhou City changed drastically and the area of rural settlements increased by 2743.92 ha. Some settlements in Zhuanlu Town, Qingfeng Town, Gaopeng Town expanded and merged, and there were also new settlements near the cultivated land. Due to the lack of village and town planning, the idea of renovating old houses was relatively weak, and the construction of new houses resulted in the disorderly expansion of most rural housing sites and a general increase in the scale of villages, a relatively scattered layout, and the problematic occupation of cultivated land. After the housing boom in rural areas, the state and local governments intervened in the management of homesteads in a timely manner, and the homestead system was gradually standardised.

5.2.3. Period of “Paid Use” of Homesteads

In the past, the lack of regulations meant that the phenomenon of multiple dwellings per household was common in rural areas. Behaviours such as over-occupancy and random construction seriously affected the appearance of the villages. One family owning multiple houses meant that a large amount of rural land was concentrated in the hands of a few people, which damaged the interests of other farmers. In order to solve these problems, the state and local governments implemented the “one household, one house” policy. The state also issued documents such as the Request for Instructions on Strengthening the Management of Rural Homesteads and Several Regulations on Determining Land Ownership and Use Rights to intensify the control of rural homesteads. In 1992, the Hebei Provincial People’s Government promulgated the Regulations on the Administration of Rural Homesteads in Hebei Province [

73]. If rural residential areas in Hebei Province exceeded the land use limit, the land was retreated within a time limit and planned index management was implemented. During this period, some rural settlements in Kaiyuan Town were converted into cultivated land, some rural settlements in Chang’an Lu Street and Beicheng Qu were vacated into cultivated land, and some were converted into urban land. The growth rates of rural settlements in Zhoucun Town, Yangjia Zhuang Town, Xingyi Town, and Xizhong Town slowed compared to the previous period. Rural homesteads were allocated by households, and redundant homesteads were recovered. This measure strengthened the organisation of rural residential sites in Dingzhou. The government also indicated the direction of action for farmers through positive advocacy and incentives and gave rewards or subsidies to villagers who voluntarily vacated their homesteads. These policies directly aroused the enthusiasm of farmers and effectively controlled the number of rural settlements.

5.2.4. Period of “Connecting Increase and Decrease” of Homesteads

In 2002, the People’s Government of Hebei Province issued the Measures for the Administration of Rural Homesteads in Hebei Province [

74], which pointed out that, upon review by the county (city) land administration department, the county (city) people’s government could take back one household from a rural villager after approval. Since then, Dingzhou has implemented the relevant regulations of the State Council on strict land management and encouraged the consolidation of rural construction land. The increase in urban construction land is linked to the reduction of rural construction land. The growth rate slowed down during this period, although the total area of rural settlements in Dingzhou increased. The average annual growth rate of rural settlements from 2000 to 2010 decreased from 1.81% in the previous period to 1.26%. Rural settlements have also retreated in most areas of Dingzhou, such as Kaiyuan Town, Dalu Zhuang Town, Dongwang Town, Zhuanlu Town, and Ziwei Town. The effective implementation of measures such as “one house for one household” and “connecting increase and decrease” has curbed the expansion of rural settlements and has prompted the spatial pattern of rural settlements in Dingzhou to change from disorder to order.

5.2.5. Period of “Separation of Three Rights” of Homesteads

With the orderly launch of the pilot work connecting the increase and decrease of urban and rural construction land, China’s homestead system has gradually improved. The General Office of the Hebei Provincial Party Committee and the General Office of the Provincial Government jointly issued the Opinions on Accelerating the Promotion of Rural Reform to explore the “separation of three rights” system for rural homesteads [

75]. In response to higher-level policies, Dingzhou also formulated institutional documents, such as the Dingzhou Homestead Management Method [

76], and started preparing the city’s village land use planning. In the Measures for the Use of Surplus Indicators for Homestead Retirement in Dingzhou City [

77], the government proposed using the increase or decrease in bonus funds to support the pilot reform. The average annual growth rate of rural settlements in Dingzhou was only 0.05% during this period, which shows that the towns and villages in Dingzhou actively responded to national policies. In March 2015, Dingzhou City was identified as one of the 33 pilot projects for the reform of the rural land system in the country and has successively carried out three pilot reforms, including the rural land expropriation system, the entry of collectively owned construction land into the market, and the homestead system. Dingzhou actively explored ways to exit during this period, and due to the long-term policy regulation and effective implementation of rural settlements, the scale and pattern of rural settlements has been optimised to a certain extent. The scale of rural settlements has not currently changed much. As a result, the average annual change in the area of rural settlements in 2020 was low.

The orderly launch of the pilot work connecting the increase and decrease in urban and rural construction land means that China’s homestead system has gradually improved. During the period of the “separation of three rights” housing estates, the average annual growth rate of rural settlements in Dingzhou was only 0.05%, which shows that all towns and villages in Dingzhou actively responded to national policies. In September 2020, 104 counties (cities, districts) and three prefecture-level cities launched a new round of pilot reforms for the rural homestead system. The core of this new round is exploring the form of separate ownership, contracts, and the management of homesteads. Dingzhou city is a pilot city in the new round of rural homestead system reform determined by the central government. In 2021, Dingzhou City promulgated the Dingzhou City Rural Homestead System Reform Pilot Implementation Plan, Guiding Opinions on the Revitalisation and Utilisation of Rural Idle Homesteads and Idle Houses in Dingzhou City (Trial) and Dingzhou Rural Homestead Circulation Management Interim Measures [

77], focusing on exploring the “separation of three rights” of homesteads and promoting the management of rural settlements in Dingzhou.

5.3. Policy Suggestions for the Reform of the Rural Homestead System

Although the state requires residential construction by rural residents to comply with the village and town construction plan and has carried out the pilot work regarding the paid use of homesteads in an orderly manner, we found that some towns in Dingzhou City did not adequately control the expansion of rural residents during the period of “paid use” of homesteads. The above phenomenon mainly occurs in towns far from the city, such as Zhuanlu Town, Dalu Zhuang Town, Dongting Town, Dongwang Town, and Haotou Zhuang Hui Township, while the expansion of rural settlements in towns close to the city, such as Mingyue Dian Town and Zhoucun Town, has been effectively suppressed. This shows that there may be some deviations in policy implementation in remote areas of Dingzhou. It is therefore necessary to strengthen the management of homesteads in remote towns and towns. Increasing the publicity and guidance of homestead policies in remote towns and towns and improving the implementation of policies in these areas should be considered.

As a pilot city for the reform of the rural homestead system, Dingzhou should also strengthen its organisation of rural settlements. In recent years, the implementation of policies such as “one house for one household” and “connecting increase and decrease” means that the growth rate of rural settlements in Dingzhou has slowed down, and the disorderly expansion of rural settlements has been effectively controlled, however, our analysis of the spatial pattern of rural settlements suggested that rural settlements in some townships in Dingzhou are small in scale and scattered in layout, including the northern part of Mingyue Dian Town, the eastern part of Kaiyuan Town, the southern part of Chang’an Lu Street, the southeastern part of Liqin Gu Town, and Yangjia Zhuang Town. The government should therefore consider optimising and adjusting the land use scale and internal structure of rural residential areas. While organising rural residential areas, the spatial layouts of Mingyue Dian Town, Liqin Gu Town, Kaiyuan Town, and Yangjia Zhuang Town should be strengthened. This is more concentrated and intensive and promotes orderly and rational land use. Reforming the rural homestead system is also important for the future development of rural residential areas in Dingzhou City. Dingzhou City could revitalise idle homesteads through the development of farmhouses, homestays, rural tourism, and so on and promote the construction and development of rural areas.

5.4. Limitations of This Study and Future Research Directions

The data for different years used in this article are slightly different, but we have adopted some methods to reduce errors caused by the data source. The data resolution (2 m) of 1962 and 1972 is different from that used in other years. The method we used was to firstly convert the spatial data for all years into unified geographic coordinates and define a unified projection; resample the data from 1962 and 1972, and change its spatial resolution to 30 m. Once the operation is complete, we unified the geographic coordinate system, projected coordinate system, and resolution of the data. Due to data transformation, however, there are still some foreseeable errors. When we converted the rural settlement data from 2 meters to 30 meters in 1962 and 1972, and the area increased by 0.087 hectares and 0.0109 hectares, respectively. The deviations were all less than 0.01%, and these deviations may cause slight changes in rural settlements at the pixel edge. In the process of analysing the changes to the spatial pattern of rural settlements, we analysed the effect of policy factors. In real society, there are many factors of the spatial pattern of rural settlements. Spatial elements such as roads, areas of water, and distances from cities and towns will also affect the distribution of rural settlements. In this study, however, these factors were assumed to be stable.

According to our understanding and analysis of the current research status and the thinking about the limitations of this paper, we believe that future research could involve the following: (1) analysing changes in the spatial pattern of rural settlements in other regions and examining whether the changes to rural settlements in each region conform to the relationship curve of the “policy-scale of rural settlements”; (2) considering the effect of other factors on the changes to the spatial pattern of rural settlements, such as population, roads, water areas, and so on. (3) Simulating and predicting the spatial pattern of rural settlements in the future according to the current trend in rural settlements policy.

6. Conclusions

This paper took rural settlement policy as its basis, analysed the scale and pattern changes of rural settlements according to Maslow’s psychological needs theory and game theory, and identified the relationship curve of “policy-scale of rural settlements” in different periods using Dingzhou City, China as an example for empirical research. We analysed the evolution of the spatial scale of rural settlements in Dingzhou from 1962 to 2020 under the influence of this policy. In terms of data acquisition, decrypted military satellite images were used for visual interpretation so as to obtain long-term historical data and extract the historical spatial information of rural settlements in Dingzhou. We used Arc GIS software to perform spatial analysis on the data for rural settlements in Dingzhou City and used the medium- and long-term land use maps of Dingzhou City to explore the evolution law of rural settlements in Dingzhou City. According to the changing trend of rural settlements in Dingzhou over the past 60 years, this paper divided the changing processes of the spatial distribution of rural settlements in Dingzhou into an expansion pattern, merge pattern, retreated pattern and urbanisation pattern. The effect of policies in different periods on the evolution of the spatial pattern of rural settlements was thus analysed. From 1962 to 2020, the total area of rural settlements in Dingzhou showed an increasing trend, with a total increase of 8354.97 ha (73%). Kaiyuan Town, Mingyue Dian Town, Xicheng Qu Street, Xizhong Town, Zhoucun Town, and Ziwei Town have expanded significantly in the past 60 years. The area of rural settlements in Zhoucun Town changed from 530.33 hectares in 1962 to 1225.08 hectares, which is an increase of 131%. The average annual growth rates for 1962–1972, 1972–1990, 1990–2000, 2000–2010, and 2010–2020 were 0.29%, 1.17%, 1.81%, 1.26%, and 0.05%, respectively.

The relevant policies of rural settlements since the founding of the People’s Republic of China have been divided into five periods according to the node events issued by the policy: the period of transition from “private ownership of farmers” to “one homestead, two systems”, the period of the “unified planning” of homesteads, the period of the “paid use” of homesteads, the period of “connecting increase and decrease" of homesteads, and the period of “separation of three rights” of homesteads. During these five periods, policy has played a role in regulating, guiding, and distributing the changes to rural settlements. The growth rate of rural settlements was relatively slow in the period of transition from “private ownership of farmers” to “one homestead, two systems”. The main policy reason for this was that rural homesteads changed from private ownership to “one homestead and two systems”, and the expansion of rural settlements was inhibited. During the period of “unified planning” for homesteads, with the deepening of reform and opening up, there was a boom in building houses in rural areas, and the growth rate of rural settlements increased. During the period of the “paid use” of homesteads, although the state had strengthened the management of rural settlements, they continued to increase in area. During the period of “connecting increase and decrease” of homesteads and the period of the “separation of three rights” of homesteads, some residential township areas began to be vacated due to the implementation of policies such as “one house for one household” and “connecting increase and decrease”, and the growth rate of rural residential areas slowed down. For example, the growth rates of Dongting Town, Dongwang Town, Gaopeng Town, Kaiyuan Town, Mingyu Dian Town, Nancheng Qu Street, and Xingyi Town were all lower compared to the previous period.