Abstract

Housing has become pivotal in attracting and retaining talent in first-tier cities. Although numerous cities are actively promoting the provision of talent housing in China, little is known about the talent’s evaluations of talent housing policies or the effect on their urban settlement intention. This paper aims to investigate whether talent housing alleviates the housing difficulties of talent and its role in retaining talent. A questionnaire was conducted face-to-face in talent housing in Shanghai. Binary logistic regression was employed to analyse the factors significantly contributing to the settlement intentions of the talent. Talent housing was confirmed to alleviate the talent’s housing pressures and further increase their urban settlement intention. The local hukou was determined to be crucial in accelerating the willingness of talent to settle in Shanghai. However, housing affordability (including school district housing) may jeopardise such positive effects. It is crucial to provide more choices of talent housing and increase the coverage of good-quality educational resources. In the long run, more talent can be attracted and retained in the locality under a broader coverage of the talent housing scheme.

1. Introduction

As “carriers” of human capital, talent has made great contributions to technological development [1,2]. “Talent” refers to highly educated or highly skilled people. Young talent is generally at the beginning of their career, with relatively weak wealth accumulation. Policymakers worldwide have recognized the pivotal role that talent and its movement plays in economic competitiveness, both globally and nationally [3]. Ever more countries are engaging in intense, global competition to attract internationally mobile human capital. As a fact, two-thirds of countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have implemented policies specifically designed to attract highly skilled migrants [4]. Both point-based systems with supply-led policies and job-offer systems with demand-led policies have been implemented to attract high-skilled migrants by issuing visas [5]. Other incentives adopted in western countries to attract talent include offers of permanent residency, tax breaks, and financial incentives [4]. However, housing policies specifically designed to attract and retain talent are virtually absent from migration policy systems.

Faced with the urgent need for deepening economic restructuring and industrial upgrading, China requires more talent, especially young talent, given the aging problem that has become increasingly serious. “Young people” refers to the population aged between 14 and 35 according to the Middle- and Long-Term Youth Development Plan (2016–2025) of China. Talent is becoming widely recognized as an essential component of urban growth in China [6]. Local governments have made various attempts to attract and retain talent. Attracting and retaining talent has become the priority strategy to promote economic development. The Thousand Talent Plan is the flagship initiative in China, which classifies talent according to levels of scientific achievement. First-tier cities in China, such as Shanghai and Shenzhen, have stated their ambitions to mature into knowledge-intensive economies. Resources, such as housing subsidies and local hukou, are tilted toward elite talent, which may enhance its intention to settle down in the locality [7].

In China, megacities have been actively promoting the provision of talent housing in recent years. Housing subsidies (both monetary and in-kind) are the main measures included in favourable housing policies designed to attract talent. Serious housing affordability problems have been identified in “superstar cities”, e.g., Beijing and Shanghai, in China [8]. The housing price-to-income ratio in Shanghai was as high as 29.85 in 2018, 2–3 times that of other cities in the Yangtze River Delta [9]. Due to the high housing prices and strict housing purchase restrictions in Shanghai, young talent (e.g., new graduates) generally has a difficulty purchasing housing [2]. Some new graduates move to suburbs for lower rents, or they sacrifice living conditions (e.g., living space or housing facilities) for advantageous housing locations [10,11,12]. Rental housing has been the most common housing choice of young people [13]. Housing difficulties induced by skyrocketing housing prices might squeeze creative talent or elites out of these cities [14]. The brain drain may become a serious deterrent to the sustainable development of cities.

Talent housing is a form of housing derived from affordable housing to improve the efficiency of social development with the evolution of talent policy [15]. Talent housing is provided in both rental and partial-ownership terms. The eligibility criteria generally include academic qualifications (a bachelor’s degree or above), national vocational qualifications (Level 2 or above), and qualifications tailored by local departments according to the needs for industrial development. For instance, the Shanghai government planned to raise 200,000 units of rental housing for talent-housing use by 2025. The Wuhan government has developed a “talent housing lottery” system to ensure the provision of affordable housing for business talent and university graduates [2]. Other cities, such as Beijing and Shenzhen, have also developed corresponding policies that strive to provide talent housing [16]. However, the following questions arise: (1) What are the actual living experiences of talent in talent housing? (2) Have talent housing policies alleviated the housing pressures faced by talent? (3) Can talent housing policies achieve the ultimate goal of retaining talent? It is necessary to investigate the residential characteristics and policy effects of talent housing, as well as the policy effects of talent housing on the willingness of talent to settle down in a locality.

Located in eastern China, Shanghai is the municipality with the second-highest gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and the second-largest population in China [17,18]. It is the core city of the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration (YRDUA), which plays a pioneering role in the wave of industry upgrading [19]. This study selected Shanghai as the study case for the following 5 reasons: (1) It is a pinnacle of talent in the country. The proportion of residents (aged 16–59) with college degrees and above increased from 26.2% to 46.4% during the period of 2010–2020 [20]. (2) The population without local hukou accounts for 42.1% of the 24.87 million residents. In particular, nearly 65% of the population aged 15–34 are migrants [21]. (3) Shanghai faces the most serious aging problem among the 4 first-tier cities in China, with 16.3% of residents being over 65 years old in 2020 (Beijing: 13.3%; Shenzhen: 3.2%; Guangzhou: 7.8%). From 2010 to 2020, the proportion of the working population (aged 15–59) decreased from 72.6% to 66.8%. The slight decrease in the working-age population and the rapid improvement in human capital are the most significant changes in Shanghai’s human-resource structure over the decade. (4) The share of people working in tertiary industries has increased from 62.9% to 72.6% during the period of 2015–2019 [22], in accordance with Shanghai’s industrial upgrading strategy. (5) As a long-standing pilot city which has pioneered housing policies in China (e.g., housing provident fund and property tax reform), Shanghai is one of the first cities to provide affordable housing to talent (including young talent, such as new university graduates).

This study aims to investigate whether talent housing alleviates the housing difficulties of talent and its role in retaining talent in Shanghai. Talent, especially young talent, in talent apartments is investigated for the following 2 reasons: (1) talent apartments are tailored to talent; and (2) rental housing has been the most common housing choice of young people (especially young migrants) [13].

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows: Firstly, studies on urban settlement intentions are discussed. Factors influencing the talent’s urban settlement intentions are discussed. Hypotheses are proposed accordingly. Second, the study area and research methods are presented. The third section analyses the factors affecting the urban settlement intentions of talent (especially young talent) and evaluates the implementation of the talent housing policy. The findings and policy implications are presented in the last section.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Talent Housing Policy

In recent years, global cities, led by London and New York, have developed various affordable housing programmes for targeted workers (key workers or essential workers), such as providing down-payment assistance, shared-ownership housing, and subsidized rental housing [16]. Targeted workers are usually engaged in public services or key sectors that affect local economies. The US has the largest number of programmes designed to provide housing assistance to public-sector workers, such as teachers, nurses, and police officers who have low-to-moderate incomes, at the national, state and city levels. England introduced the Key Workers Living Program as early as 2004, identifying the categories of public-sector workers eligible for key worker housing assistance [16]. However, the Key Worker Lives Program was criticized for privileging certain public-sector workers over others [23].

Compared with the targeted workers in the US and England, talent housing in China targets for highly educated and highly skilled workers of a wider range of occupations, such as technical specialists, independent executives, senior managers, and specialized technicians. Since the 2000s, China has accelerated the pace of its public housing provision. To sustain place competitiveness, local governments have included talent in public housing schemes. For instance, Shanghai initiated a talent housing programme as early as 2006. Talent with housing difficulties was included in the Public Rental Housing (PRH) scheme in 2010 [24]. By the end of 2020, Shanghai had raised a total of 187,000 units of PRH for talent-housing use. Besides PRH, private housing was rented by the government or leasing agencies for talent-housing use.

2.2. Residential Preferences of Talent

Talented workers with differing socio-economic characteristics have particular preferences for housing locations, housing sizes, dwelling costs, commuting distances, and residential amenities [25,26,27]. For instance, older talent prefers quiet neighbourhoods in suburbs [26,28]. The metropolitan core is preferred by young talent for cultural and sports activities and by self-employed professionals, who tend to be workaholics [29]. Talent in the Randstad region of the Netherland was found to most value a residential environment with high levels of natural amenities [25]. The effects of regional characteristics on attracting talent have also been well-discussed, such as employment opportunities, housing affordability, regional amenities, accessibility, diversity, and equity [30,31].

The importance of lifestyle factors in affecting the residential choices of talent (e.g., housing location, building type, and housing size) have been highlighted. Lifestyle factors include life-cycle stage, work-role, and leisure activities [31]. Highly skilled talent with work-oriented lifestyles would prefer suburban large detached houses [32]. Constrained by lower incomes, younger talent tend to rent small- or medium-sized apartments rather than purchasing large dwelling units. Talent with children exhibits strong preferences for homeownership and large dwellings in suburbs due to housing affordability and accessibility to the natural environment [31,33].

2.3. Urban Settlement Intentions of Talent

2.3.1. Effects of Socio-Economic and Demographic Characteristics on Urban Settlement Intention

Urban settlement intention is the willingness of a person to settle down in a cities permanently [34]. Current studies have largely focused on the urban settlement intentions of migrants. The determinants and motivation of settlement intentions, especially demographic characteristics, institutional factors, economic incentives, and attachment to the locality, have been extensively investigated [35,36]. With regard to demographic characteristics, young migrants who lived with spouses were found to have stronger tendencies to settle in cities [37]. The cohort effect was a key factor affecting the settlement intentions of migrants. The younger generation (born after the 1980s) usually shows a stronger desire for urban settlement than does the older generation. They are more influenced by desires and the features of destination cities [38]. Female migrants were found to have stronger settlement intentions than male migrants [39]. Moreover, children were decisive in migrants’ permanent settlement intentions through the utility derived from children’s educations and family unification in urban areas [40].

The household registration system (hukou) has been considered as the key barrier to migrants’ settlement intentions in host cities. Migrants suffer exclusion from equal access to basic public services in localities, such as education, social security, and public housing [37,41]. However, rural migrants usually hesitate to obtain urban hukou in host cities at the cost of losing farmland and homesteads in their hometowns [42]. Rural land is considered to be social security for rural migrants to combat unexpected risks in urban areas [43]. However, another strand of literature considers that other factors, such as housing, have been playing an increasingly pivotal role in boosting/hindering the urban settlement of migrants [44].

Economic incentives include human capital and labour-market status. Migrants usually make settlement decisions depending on whether they can maximise their value of human capital and the economic prospects in the locality [45,46]. Highly educated migrants are likely to be permanent settlers [32]. The longer migrants reside in a locality, the more human capital they may continuously accumulate over time. The accumulation of human capital may further strengthen the migrants’ capability to integrate economically into the locality. Furthermore, stable employment, higher income, and richer working experience are factors motivating migrants to permanently settle down in cities [47]. Self-employed migrants are more determined to have permanent urban settlement [48]. They are more integrated into urban areas and more capable of utilising economic and social paths to co-reside with family members in cities [49].

The effects of social and cultural attachment to the locality on the urban settlement intentions of migrants have been emphasised [44,50,51]. Such an attachment is usually derived from a well-developed network of social ties. Supportive social ties in the locality, such as family members and children, and frequent interactions with local people could largely facilitate migrants’ desires to stay home and reduce their intentions to return to hometowns [52,53]. Newly-formed ties with non-kin residents have been positively linked to the permanent settlement intentions of migrants [44,50].

2.3.2. Effects of Housing on Urban Settlement Intention

The effect of housing on the behaviour of urban settlement is believed to be no weaker than that of hukou [54,55]. Homeownership is not only the strongest predictor of migrants’ place attachment, but it is also a form of assimilation into the host city [34]. The access to formal housing, such as commodity housing and public housing, is positively correlated with the strong settlement intentions of migrants [44]. Formal housing might enable migrants to be integrated into a locality by expanding the social network of local ties. Among migrants living in formal housing, those living in public rental housing have expressed stronger willingness to settle down in the locality, compared with those living in private rental housing [34]. Moreover, housing attributes (e.g., quality, location, and size) also have significant effects on the migrants’ settlement intention [34,41,56]. Rural migrants living in larger and better-quality housing are more determined to settle down in cities [34].

However, the effect of housing on the settlement intentions of migrants is argued as being more related to the sorting process of particular migrants than due to the enabling effect of formal housing [44]. That is, migrants who are inclined to settle in a locality would exert more effort toward obtaining access to formal housing. For instance, migrants with no plan to return to hometowns are most likely to live in commodity housing [41]. Hence, investigating the residential plans of migrants is significant in revealing the effect of housing on their settlement intentions.

Moreover, housing prices in host cities are negatively correlated with the urban settlement intentions of migrants [56]. The expected wealth accumulation by urban integration cannot compensate for the decrease in the utility of migrants due to rising housing prices [57]. Migrants (especially skilled ones) are more likely to settle down in larger cities due to better opportunities and public services [58]. To this end, conducting further research on the settlement intentions of skilled migrants in the public housing of large cities is important.

This study was conducted for the following 3 reasons: (1) Although skilled migrants are a non-ignorable part of the talent population, talent also includes those with local hukou. The settlement intentions of residents with local hukou have been under-studied. (2) Although talent has been found to have particular housing preferences, few studies have paid proper attention to the role of housing characteristics (e.g., housing size, rent, and location) in shaping the urban settlement intentions of skilled migrants. (3) No studies have investigated the effects of talent-housing policies on the urban settlement intentions of talent, and in particular, that of young talent.

To fill the research gaps, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H1:

Local hukou plays a pivotal role in retaining talent in first-tier cities.

H2:

Talent residing in central areas of a locality is more willing to settle down.

H3:

Talent planning to renew the lease contract of talent housing has a higher willingness to settle down than that planning to rent commercial housing.

H4:

Policy evaluation positively affects the urban settlement intentions of talent.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Area and Data Collection

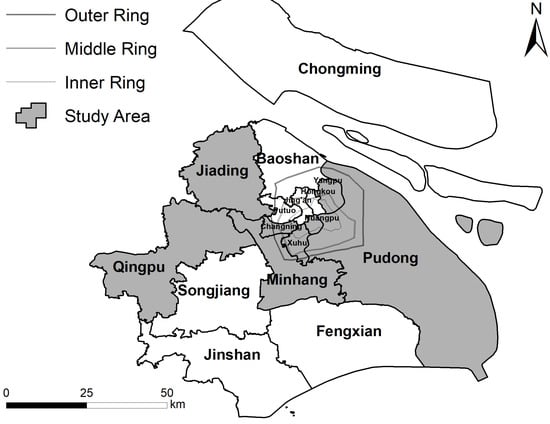

Shanghai is located within the metropolitan area of the YRDUA, which is one of the most developed and dynamic regions in China (see Figure 1 for a map of Shanghai). As 1 of the 4 first-tier cities, Shanghai has been attracting numerous migrants from all over the country, with non-local residents accounting for 42.1% of the total population (10.48 million) in 2020 [59]. To attract and retain talent, the Shanghai government launched a pilot project of providing talent apartments in 2006. The construction and management of talent apartments are relatively mature industries in Shanghai.

Figure 1.

Map of Shanghai, China (Source: the authors).

We conducted a face-to-face questionnaire survey with talent living in the talent housing of Shanghai from June to September 2018. Shanghai comprises 16 districts. The survey area included eight districts, namely, Pudong District, Xuhui District, Changning District, Jiading District, Minhang District, Qingpu District, Yangpu District, and Huangpu District. (See districts marked in grey in Figure 1) As of June 2018, the provision of talent apartments in these 8 districts accounted for 94% of the total provision in Shanghai. Among the eight districts, Jiading District and Xuhui District have applied a certain proportion of the public rental housing as talent apartments.

A door-to-door survey was conducted with the residents living in talent apartments. Probability proportionate to size (PPS) sampling was employed by assigning probabilities in proportion to the size of the samples. As a sample unit with a larger size is expected to make a greater contribution to the total of the samples, the selection bias of this sampling is minimum. The sample size of each district was determined by the proportion of talent apartments provided in each district. (See sample distribution in Table 1) A total of 11 talent apartments were surveyed in the 8 districts. The respondents were asked about personal and household characteristics, residential characteristics, plans for residence in the locality, evaluations concerning talent apartments, and their intentions to stay in the locality. (See the Appendix A for the sample questionnaire) We distributed 249 questionnaires, of which 229 samples were valid.

Table 1.

Sample distribution in Shanghai.

3.2. Data Analysis

The dependent variable was the intention to settle in Shanghai. Respondents were asked about their intentions to settle down in Shanghai (no or not sure = 0; yes = 1). In view of the fact that the dependent variable was a dichotomous variable, the binary logistic regression was employed. The formula was denoted as follows:

where is the response concerning settlement intention in Shanghai; denotes the probability of respondent intending to settle down in Shanghai; represents the independent factors; is the partial regression coefficient corresponding to ; is the intercept; and is the error term.

Independent variables included demographic and socio-economic characteristics (e.g., gender, age, education, marital status, income, hukou, etc.), residential characteristics (e.g., length of residence, housing size, rent, location, waiting period, etc.), residential plans, and policy evaluation. Specifically, the length of residence was measured by the period of residing in a talent apartment. The waiting period measured the length of time spent on waiting for the approval of talent-housing applications. To neutralize the “sorting effect” of housing choice on urban settlement intention, this study used “housing plans” instead of “housing choices”.

Residential plans could partly reflect the trade-off between the housing market and the labour market, which might be closely related to urban settlement intention. The residential plan was the housing plan after the expiration of the eligibility to live in a talent apartment, including the continued application for a talent apartment (coded as 1), renting commodity housing (coded as 2), and purchasing commodity housing (coded as 3). The policy evaluation was obtained by asking “Do you think the talent-housing policy has alleviated your housing pressure in Shanghai?” (no = 0; yes = 1).

4. Results

4.1. Talent Housing in Shanghai

4.1.1. Application Procedure for Talent Apartments

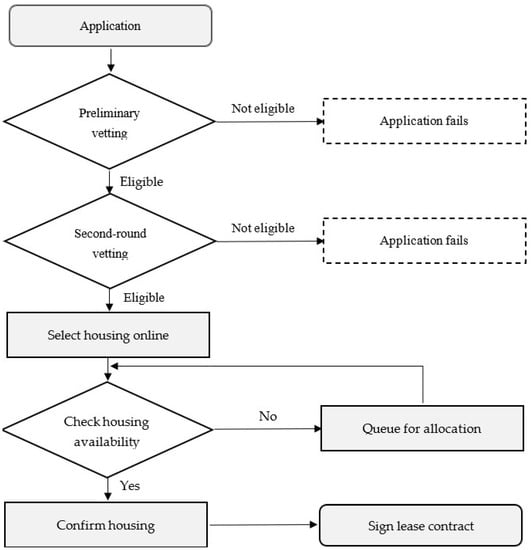

Talent apartments are transitional housing dedicated to meet the short-term housing needs of talent. They are provided to talent who has been identified by the government of each district. The rent is set at a discounted price for the rental housing in the neighbourhood. Applicants can be individuals or working units. The management agencies of talent apartments are responsible for the preliminary vetting of the applications. If the preliminary vetting is approved, the applications are further vetted by the Talent Service Centre the Bureau of Human Resources and Social Security (i.e., second-round vetting). Applicants can select talent apartments online if their applications are approved. There is a waiting list to apply. Once the selected talent apartments are available, talent can sign a lease contract with the management agency. (See Figure 2 for the application procedure for talent apartments). The typical lease term for a talent apartment is 2–3 years. If necessary, an application can be made to renew the lease contract before it expires. The cumulative lease term cannot exceed 6 years.

Figure 2.

Application procedure for talent apartments (Source: the authors).

4.1.2. The Case of Wulingyuan Court

Fulinjiayuan Court (name of the court, 福临佳苑 in Chinese) is the first public rental housing project in Jiading District, Shanghai (Figure 3). It also serves as a district-level talent apartment. It was constructed in 2013 and put into use in 2017. The site area is 13,000 square meters. The complex is comprised of 3 buildings, with 2 buildings (11 floors and 13 floors, respectively) for residential use and 1 building (6 floors) for commercial and community use.

Figure 3.

Photos of Fulinjiayuan Court (Source: the authors): (a) Layout of the complex; (b) Residential building.

The complex is well-equipped with sports facilities, open spaces, and green belts. A total of 564 apartments are provided, which are mainly small-sized (area: 45 square meters). The monthly rent ranges from CNY 1000–1500 (USD 157–235), depending on the floor and the usage type of the apartment (public rental housing or talent housing). The rent for talent qualified by the district government can be as low as CNY 990 (USD 155) per month.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

The respondents were mainly young talent with an average age of 29. About 90% of them were under 35 (Table 2). Nearly 52.0% of them were male (Table 3). Almost 40% of them were married and had higher settlement intentions than single talents. The educational attainment of the respondents was high. All respondents held bachelor’s degrees and above. Specifically, 51.5% of them held master’s degrees and above. Among the 229 respondents, 64.6% of them planned to settle down in Shanghai. The proportion of leader respondents who planned to settle down in the locality was the highest (76.5%), followed by managers (67.1%), clerks (63%), and professional technicians (60.6%).

Table 2.

Age ranges of the respondents.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

The per capita income of the respondents was relatively high (i.e., CNY 21,357 (USD 3226) per month on average). Specifically, the proportion of the respondents with monthly incomes greater than CNY 20,000 (USD 3021) was the highest (49.4%), followed by those earning between CNY 10,000 (USD 1511) and CNY 20,000 (USD 3021) per month (32.3%), and those earning less than CNY 10,000 (USD 1511) per month (18.3%). The higher the income they earned, the more likely it was that they intended to settle down in the locality. Specifically, 83.2% of those earning over CNY 20,000 (USD 3021) per month had the intention of settling down in Shanghai. That figure dropped to 50% for respondents earning between CNY 10,000 (USD 1511) and CNY 20,000 (USD 3021) per month, whilst the number was 40.5% for those with monthly incomes below CNY 10,000 (USD 1511).

The respondents were both local (35.8%) and non-local residents (64.2%) in talent apartments. Approximately 65.0% of them intended to settle down permanently in Shanghai, similar to the findings of Tang and Feng [38]. About 49% of the residents without local hukou intended to settle down in Shanghai. Interestingly, 7.3% of the residents with local hukou did not intend to settle down in Shanghai. Although this segment of the talent has obtained local hukou, it is still confronted by housing difficulties, which may hinder it from settling down in the locality [60]. Moreover, the respondents had been living in the talent apartments for 20 months on average. A total of 75.1% of the respondents indicated that talent housing had alleviated their housing pressure, of which, 73.8% expressed an intention of settling down in Shanghai.

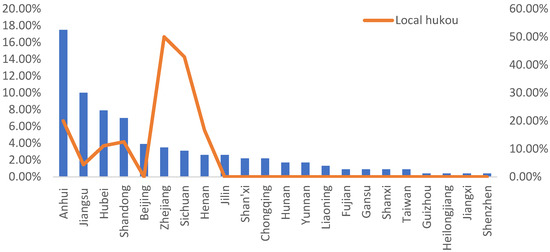

It is worth noting that 72.4% of the respondents indicated that their original places of hukou registration were not Shanghai although 12.71% of them had obtained local hukou (Figure 4). The highest proportion of them came from Anhui Province (17.5%), followed by Jiangsu Province (10%), Hubei Province (7.9%), Shandong Province (7%), Beijing City (3.9%), Zhejiang Province (3.5%), Sichuan Province (3.1%), etc.

Figure 4.

Places of origin of the respondents. (Source: survey by the authors, 2018).

4.3. Regression Results

A total of 4 models were constructed (Table 4 and Table 5). A backward stepwise method was employed. The effects of socio-economic characteristics, residential characteristics, residential plans, and evaluations of talent-apartment policies were analysed in Models 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. It is worth noting that job title was not included in Model 1 since it did not pass the chi-squared test. Average living area was excluded upon adding it to Model 2. All models were significant at the 99% confidence level. The fitting degree of the model improved.

Table 4.

Effects of socio-economic and residential characteristics.

Table 5.

Effects of residential plan and policy evaluation.

4.3.1. Effects of Socio-Economic Characteristics

According to Model 1, the effects of age, income, and local hukou were significantly positive at the 95% confidence level and above. It is worth noting that the effect of age showed an inverted U-shaped curve. Namely, talent aged 26 to 38 (middle-aged among the respondents) had the highest intentions of settling down in Shanghai, whilst talent aged 23–25 and 39–45 was less willing to settle down. Such cohort differences might be caused by the effects of lifecycles, which is consistent with previous studies [38]. According to the survey, 21 out of the 32 respondents who were aged 23 to 25 (i.e., the younger group) attributed their unwillingness to settle down in Shanghai to the instability of work and high housing prices.

Differing from younger respondents, those aged 39–45 indicated that they made settlement decisions based on the principle of maximising the utilities of the whole family. They emphasised the importance of household factors (especially the children’s education). According to the survey results, they preferred to move to rapidly developing, second-tier cities due to the high price of school-district housing in Shanghai and the resulting, relative lack of high-quality educational resources. As expected, higher incomes significantly increased the willingness of respondents to settle down in the locality, which is similar to the findings of Dang, Chen, and Dong [56].

With respect to institutional factors, the local hukou had a positive influence on the respondents intentions to settle in Shanghai. Specifically, the possibility of respondents with local hukou intending to settle down in the locality was 12.61 times that of non-local respondents. Similarly, Choy and Li [61] maintained that the local hukou of large cities remained attractive to migrants, even offsetting their demand for higher wages. Although the effect of hukou on migrants has increasingly given way to other factors, such as economic abilities and housing characteristics, it cannot be ignored [34,41,54].

It is noteworthy that 7.3% of the respondents who held local hukou did not intend to settle down in Shanghai, which can be explained by other factors, including income, age, marital status, and housing affordability. The monthly income of the aforementioned respondents was CNY 10,500 (USD 1586) on average, only half of the average income of the full sample (i.e., CNY 21,357/month) (USD 3226). Furthermore, the average age was 25, which is much younger than that of the full sample (29 years old). As discussed above, respondents aged 23–25 were less willing to settle down than those aged 26 to 38. Regarding their marital status, all aforementioned respondents were married. This is an interesting result because married people were assumed to place more emphasis on stability and to have higher intentions of settling down. This group of married respondents attributed their unwillingness to settle down in Shanghai to the instability of work and high housing prices.

Interestingly, the effect of educational attainment was insignificant in this study, which is different from the findings of other studies [61]. Respondents with higher educational attainments seemed to have lower intentions of settling in the locality. Shen and Li [62] compared the talent-based settlement criteria in Shanghai and Beijing. They claimed that doctoral degrees in Shanghai were not as favoured as they were in Beijing, and skilled migrant workers were more preferred in Shanghai.

4.3.2. Effects of Residential Characteristics

Based on Model 1, residential characteristics were added to Model 2. The average living area was eliminated from the model in the stepwise progress. Residential characteristics significantly affected the urban settlement intentions of the respondents, thus verifying Hypothesis 2. Lower rent would significantly increase the urban settlement intention of respondents. Lower rent could reduce the living costs of respondents in first-tier cities and alleviate their housing burdens. They may have higher economic capacities to settle down in Shanghai. The longer these respondents lived in talent apartments, the stronger were their intentions of settling down in Shanghai. A longer period of stay in the talent apartments, on the one hand, could increase the place attachment of respondents to the locality. On the other hand, a longer period of stay could indicate the stability of the respondents’ working status since long-term employment contracts were prerequisites for applying for talent housing. Working stability further contributed to the respondents’ willingness to stay permanently in Shanghai.

The waiting period (from application, through qualification auditing, to approval) was also a crucial factor. The longer the waiting period was, the less willing the respondents were to settle down in Shanghai. Each additional month of waiting decreased the possibility of the respondents settling down in Shanghai by 1.08 times (i.e., 1/0.93). Longer waiting periods may lead to higher housing expenditure for respondents. They may have to seek housing in the market.

Furthermore, significant differences in urban settlement intentions were found among respondents living in different locations. Respondents living in areas between the middle ring and the inner ring were most likely to have the intention of settling down in Shanghai. Respondents living between the middle ring and the inner ring (that is, within the inner ring) were 3.94 times (3.15 times) more likely to stay permanently in Shanghai than those living outside the middle ring. According to the survey, about 50% of the respondents residing in the inner ring worked in the financial industry. Their average income was about 1.9 times that of respondents residing in the outer ring. They could afford the high living costs in Shanghai. In addition, there was no significant difference between locations of respondents with different job titles.

4.3.3. Effects of Residential Plan

Based on Model 2, Model 3 investigated the effect of residential plans on respondents’ intentions to settle in the locality. Respondents planning to purchase commercial housing exhibited a higher willingness to settle down in Shanghai. Specifically, the settlement intentions of prospective homebuyers were 7.78 times greater than those of respondents planning to renew their lease contracts. Homeownership was the strongest predictor of settlement outcome [34].

It is worth noting that respondents planning to renew their lease contracts upon the expiry of their tenancy in talent housing indicated higher intentions of settling down in the locality than those who were planning to rent commercial housing, thus verifying Hypothesis 3. Nearly 23.1% of the respondents considered renting as the most suitable choice after the expiry of their leasing contracts for talent apartments. They attributed the choice to housing affordability. Given that non-housing expenses account] for 64% of their incomes, it may be difficult for respondents to afford high housing costs with their remaining incomes.

Furthermore, respondents with junior job titles were more likely to renew their lease contracts upon expiry. Specifically, the largest proportion of potential homebuyers were managers (50.6%). Among those planning to renew their lease contracts, the largest proportion were clerks (44.1%). The largest proportion of professional technicians (35.8%) planned to rent commercial housing.

4.3.4. Effects of Policy Evaluation

Based on Model 3, policy evaluation was added to Model 4 for further regression. Interestingly, respondents who indicated that talent housing policy had alleviated their housing pressures were 3.37 times more inclined to settle down in Shanghai than were their counterparts, verifying Hypothesis 4. In general, the respondents were satisfied with the talent-housing policy according to our survey (dissatisfied: 8.3%; neutral: 52.4%; satisfied: 39.3%). Specifically, they were most satisfied with the criteria for eligibility (satisfied: 71.2%; dissatisfied: 2.2%), methods of housing security (satisfied: 55.5%; dissatisfied: 4.4%), and fairness (satisfied: 50.2%; dissatisfied: 0.4%). On the other hand, the rent for talent housing received the highest proportion of dissatisfaction (dissatisfied: 21%; satisfied: 48%), followed by housing alternatives (dissatisfied: 17.9%; satisfied: 34.1%), exit mechanisms (dissatisfied: 17.5%; satisfied: 45%), application procedures (dissatisfied: 16.2%; satisfied: 45%) and waiting periods (dissatisfied: 14.4%; satisfied: 43.2%).

Effective housing policies are needed to alleviate the housing burden of the respondents, thus increasing their settlement intentions in first-tier cities. In view of the relatively low level of satisfaction with the rent, housing alternatives, and waiting periods of talent housing, full use should be made of housing stocks, e.g., commercial housing and qualified housing in urban villages. In this way, more alternative types of talent housing could be guaranteed in terms of rents, locations, layouts, etc. The surrounding facilities (e.g., hospitals, schools, bus stations, etc.) are more mature. The varying housing needs of talent could be better fulfilled. Furthermore, the waiting period for talent housing could be shortened. Vacant housing units could be used more fully. The circulation of talent housing could be accelerated, thus improving the exit mechanisms. The government’s pressure to increase the provision of talent housing could be relieved.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Conclusions

Using data from the questionnaire administered in the talent apartments of Shanghai in 2018, this study investigated the policy effects of talent housing on the settlement intentions of respondents in Shanghai. The research objectives covered not only non-local respondents, but also respondents with local hukou. More than 60% of the respondents planned to stay permanently in Shanghai. The supporting role of talent housing was confirmed in terms of soothing interim housing difficulties and increasing urban settlement intentions. All four hypotheses were supported.

We feel that 5 interesting findings are worth noting: (1) Respondents with local hukou were more inclined to settle down in Shanghai. The local hukou in first-tier cities remains a pivotal incentive for talent to settle down in a locality. However, housing affordability has become a major concern for talent, with or without local hukou, in regard to settling down in Shanghai, resulting in the weakened ability of the city to retain and attract human capital. (2) Family factors were highly emphasised by middle-aged respondents, e.g., children’s education and the associated school-district housing. (3) The characteristics of talent housing did significantly affect the settlement intention of respondents. Among them, long waiting periods did have a significantly negative effect on the respondents’ willingness to settle down. (4) Location was another aspect of talent housing which significantly contributed to respondents’ intentions to settle down in a locality. Respondents residing in central areas were more inclined to stay permanently in the locality. (5) Prospective homebuyers showed the highest urban settlement intentions among all the respondents. Respondents who were planning to renew their lease contracts upon the expiry of their tenancies in talent housing were more willing to settle down than those planning to rent commercial housing.

5.2. Policy Implications

The corresponding policy implications are as follows:

First, aside from relaxing the criteria of obtaining local hukou, local governments of megacities should provide more affordable housing or housing assistance to targeted workers (including talent), which is crucial in attracting and retaining talent. Shanghai is one of China’s economic centres with a high hukou entry threshold. The Shanghai government relaxed the criteria for obtaining local hukou in 2019 so as to attract young talent. Only a bachelor’s degree is required for a new graduates from one of the top four universities in Shanghai to apply for local hukou. Previously, a master’s degree and above was required. However, local hukou may not guarantee the settlement intentions of talent in the locality. More affordable housing (e.g., down-payment assistance) should be provided.

Second, lowering the prices of school-district housing and balancing educational resources could not only retain talent, but it could also cultivate more talent in the locality. Purchasing school-district housing is the simplest way for parents to ensure their children’s access to high-quality compulsory education (primary school and middle school) in China, which has made high-quality educational resources tilt toward the high-income class. The government has made a great effort to weaken the links between housing property and high-quality schools over recent years, including the implementation of “multi-school zoning” in Beijing, “large school districts” in Shenzhen, and “quota allocation and comprehensive evaluations” for high-school enrolment in Shanghai [63,64,65]. However, these efforts have hardly cut the connection between housing property and high-quality schools. The fundamental strategy may be to improve the overall quality of educational resources and expand the coverage of high-quality educational resources.

Third, increasing the supply of talent housing could shorten the waiting period. The Shanghai government planned to raise 200,000 units of rental housing for talent-housing use by 2025. Housing stocks will be fully used, including private rental housing, unused homesteads, and dormitories located in industrial parks. Housing stocks can provide more location choices to talent and could be surrounded by more mature facilities. Furthermore, more location choices could improve the balance between jobs and housing. Thus, housing stocks could fulfil the housing needs of talent. Another key measure to ensure the adequate supply of talent housing is to improve the exit mechanism for talent housing. The circulation of talent housing can be accelerated in this way. The government’s pressure to increase the provision of talent housing could also be relieved.

Fourth, the particular housing preferences of talent should be taken into consideration when providing talent housing. Skilled migrants were found to place more importance on living standards and quality of life [66]. Compared with talent apartments located outside the middle ring, those within the middle ring could enjoy the mature facilities and high-quality services in first-tier cities (e.g., education, health care, and transportation). The living convenience and delightful experiences could increase the talent’s intentions to settle down in the locality.

Fifth, aside from facilitating homeownership (e.g., providing shared-ownership housing), it is vital to increase the talent’s residential satisfaction. The built environment of talent housing should be paid special attention during the phases of urban planning and community design, such as accessibility to various facilities (e.g., transportation, healthcare, education, parks, sport facilities), walkability, and open spaces. Talent housing in Shanghai plays the role of an interim accommodation. Eligible applicants can live there and receive housing subsidies for 3–5 years. Once a lease contract expires, talent can opt to renew the contract or move out. Tenancy renewal indicates not only a stable working status, but also the talent’s satisfaction with the talent apartment.

The contributions of this study are 3-fold: (1) This study fills the knowledge gap regarding the effects of talent-housing policies on the urban settlement intentions of talent, especially young talent. (2) Only a few studies have paid proper attention to the effects of housing characteristics on the urban settlement intentions of skilled migrants. As a supplement, this study examines the role of talent-housing characteristics and residential plans in shaping settlement intentions. (3) Besides non-local talent, this study investigated the settlement intention of talent with local hukou, which has been under-studied in the literature.

There are limitations to this study. Settlement intention was coded as a dummy variable (i.e., yes = 1, no or not sure = 0) due to the limited sample size. Talent that was unsure about settlement was not analysed separately from that which did not intend to settle down in the locality. The neighbourhood environment, which is an important factor contributing to people’s quality of life, may have a positive effect on the talent’s urban settlement intentions, which can be examined in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.T.; methodology, X.L. and W.G.; software, X.L.; validation, L.T., V.J.L. and M.C.; formal analysis, X.L.; investigation, W.G.; resources, L.T.; data curation, X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.T., X.L. and W.G.; writing—review and editing, L.T., V.J.L. and M.C.; visualization, X.L.; supervision, L.T. and M.C.; project administration, L.T. and V.J.L.; funding acquisition, L.T., V.J.L. and M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China [No. 18YJC630160], the National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 71804105], the National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 71904124], the Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China [No. 18YJCZH092], and Shanghai Municipal Government’s Decision-making Consultation Research Key Projects [No. 2021-A-026].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Sample of Questionnaire

1. Personal information

1.1 Gender: □Male □Female

1.2 Age: __________

1.3 Education: __________

1.4 City of graduation: __________ (Province) __________ (City)

1.5 Highest degree obtained: __________ (Year) __________ (Month)

1.6 Hukou status:

(a) Place of registration: __________ (Province/Municipality)

(b) Hukou type: □Urban □Rural

(c) Year of arrival in Shanghai: __________ (Year)

1.7 Marital status:

| (a) Single (b) Cohabiting | ||||

| (c) Married | Live with spouse: | □Yes | □No | |

| Number of Children: | __________ | |||

| Family size (including yourself): | __________ | Family members in the locality: | _________ | |

| Location of spouse: | □Local | □Hometown | □Others: __________ | |

| Location of children: | □Local | □Hometown | □Others: __________ | |

| (d) Separated (e) Divorced | ||||

1.8 Industry:

□Real estate □Manufacturing □Transportation and storage

□Finance □Software and information technology □Others: __________

1.9 Title: □Leader □General manager □Professional and technical staff □General staff

1.10 Type of work unit:

□Public sector □State-Owned Enterprises □Joint venture or foreign-funded enterprises

1.11 Income and Expense: (a) Income: __________ (CNY/month) (b) Expense: __________ (CNY/month)

2. Talent housing

2.1 Method of application:

□Joint application (with spouse) □Individual application □ Joint application (with others) □Others: ________

2.2 Form of residence:

□Living alone □Family (with spouse) □Family (with spouse and children) □Others: __________

2.3 Waiting period: __________ (months)

2.4 Length of residence: __________ (months)

2.5 Location of residence:

□Within inner ring □Between inner ring and middle ring □Outside middle ring □Other: __________

2.6 Living conditions

(a) Rent: __________ (CNY/month); (b) Living area: __________ (Square meters)

(c) Layout: number of bedrooms __________; number of living rooms__________

(d) Floor: __________; total floors in the building: __________

(e) Supermarket or wet market (within 1 km): □Yes □No; (f) Hospital (within 1 km): □Yes □No

(g) School (within 1 km): □Yes □No (h) Bus or subway station (within 1 km): □Yes □No

2.7 Commuting mode: □Subway □Bus □Walking □Bicycle □Motorcycle □Private car □Others: _________

2.8 Commuting distance: _________ (minutes)

2.9 Residential plan after the expiration of talent-housing lease:

□Renew lease contract □Rent commercial housing □Purchase commercial housing □Other: _________

2.10 Housing purchase plan:

□Within 1 year □Within 2–5 years □Within 6–9 years □After 10 years □Other: _________

2.11 Housing satisfaction (Please tick as appropriate)

| Very Dissatisfied | Dissatisfied | Neutral | Satisfied | Very Satisfied | |

| Layout | |||||

| Sound insulation | |||||

| Area | |||||

| Ventilation and light | |||||

| Furniture and appliances | |||||

| Rent | |||||

| Natural environment | |||||

| Distance from the city centre | |||||

| Commuting distance | |||||

| Amenities | |||||

| Safety | |||||

| Property management fees | |||||

| Vehicle management | |||||

| Community culture | |||||

| Overall satisfaction |

3. Housing experience in the locality

3.1 Frequency of residential changes in Shanghai: _________

3.2 Tenure of previous housing: □Homeownership □Rental housing □Others: _________

3.3 Type of the previous housing:

□Commercial housing □Housing in urban villages □Dormitory □Public rental housing

□Housing of family members or friends □Others: _________

3.4 Reasons for choosing talent housing:

□Work changes □Save on housing expenses □Children’s education □Improve living conditions

□Family structure change (e.g., marriage or birth of children) □Others: _________

4. Evaluation of talent-housing policy

4.1 Do you think talent-housing policy has alleviated your housing pressures in Shanghai? □Yes □No

4.2 Do you plan to exit the talent-housing programme after the expiration of your current lease? □Yes □No

4.3 Satisfaction wtih talent-housing policy (Please tick as appropriate)

| Very Dissatisfied | Dissatisfied | Neutral | Satisfied | Very Satisfied | |

| Eligibility for application | |||||

| Procedure for application | |||||

| Waiting period | |||||

| Exit mechanism | |||||

| Tenure security | |||||

| Rent | |||||

| Housing options available | |||||

| Policy fairness | |||||

| Overall satisfaction |

4.4 Suggestions for talent-housing provision: ________________________________________

5. Social integration in the locality

5.1 Do you hold Shanghai hukou? □Yes □No

5.2 Do you plan to settle down in Shanghai? □Yes (Skip to 5.6) □No □Not sure

5.3 What are the main factors that make you unsure or unwilling to settle down? (multiple choices)

□High housing prices □Family issues □High living costs

□High work pressure □Unable to integrate into the locality □Others: _________

5.4 Which city do you plan to live in? □Hometown □Other cities: _________

5.5 When do you plan to leave Shanghai? In _________ (years)

5.6 Do you consider yourself to be a local person? □Yes □No □Not sure

5.7 Please rate your level of social integration: _________ (1–5, higher scores indicate higher levels of integration)

5.8 Friends in the locality:

(a) Number of fellow-townsman: □None □Very few □Some □Many □A lot

(b) Number of local friends: □None □Very few □Some □Many □A lot

References

- William, R.K.; William, F.L. The supply side of innovation: H-1B visa reforms and U.S. ethnic invention. J. Labor Econ. 2010, 28, 473–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Pan, Y. Human capital, housing prices, and regional economic development: Will “vying for talent” through policy succeed? Cities 2020, 98, 102577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.; Hogarth, T. Attracting the best talent in the context of migration policy changes: The case of the UK. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2017, 43, 2806–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaika, M.; Parsons, C.R. The gravity of high-skilled migration policies. Demography 2017, 54, 603–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osanami Törngren, S.; Holbrow, H.J. Comparing the experiences of highly skilled labor migrants in Sweden and Japan: Barriers and doors to long-term settlement. Int. J. Jpn. Sociol. 2017, 26, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLachlan, I.; Gong, Y. Community formation in talent worker housing: The case of Silicon Valley talent apartments, Shenzhen. Urban Geogr. 2022, 43, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yan, X. Does informal homeownership reshape skilled migrants’ settlement intention? Evidence from Beijing and Shenzhen. Habitat Int. 2022, 119, 102495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Qin, Y.; Wu, J. Recent housing affordability in urban China: A comprehensive overview. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 59, 101362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Yang, S.; Chen, Y.; Bai, C. Spatial-temporal evolution patterns and convergence analysis of housing price-to-income ratio in Yangtze River Delta. Geogr. Res. 2020, 39, 2521–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, L.; Chang, K.-L. Do internal migrants suffer from housing extreme overcrowding in urban China? Hous. Stud. 2017, 33, 708–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, T. Quantifying and visualizing jobs-housing balance with big data: A case study of Shanghai. Cities 2017, 66, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Liu, R.; Qi, W.; Wen, J. Urban land regulation and heterogeneity of housing conditions of inter-provincial migrants in China. Land 2020, 9, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grander, M. The inbetweeners of the housing markets—Young adults facing housing inequality in Malmö, Sweden. Hous. Stud. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, M.; Lin, Z. Does housing unaffordability crowd out elites in Chinese superstar cities? J. Hous. Econ. 2019, 45, 101571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y. Research on establishing and perfecting the mechanism of talent apartment. Sci. Dev. 2018, 2, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, N. Building talented worker housing in Shenzhen, China, to sustain place competitiveness. Urban Stud. 2013, 51, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Bulletin of the Seventh National Population Census. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/tjgb/rkpcgb/qgrkpcgb/202106/t20210628_1818822.html (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- China Business Network. Per Capita GDP of 31 Provinces: Beijing and Shanghai Exceeded 150,000 Yuan, Chongqing and Hubei Surpassed Shandong. Available online: https://www.yicai.com/news/101048478.html (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Wang, L.; Xue, Y.; Chang, M.; Xie, C. Macroeconomic determinants of high-tech migration in China: The case of Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration. Cities 2020, 107, 102888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Statistics Bureau. The Answers to Reporters’ Questions at the Press Conference on the Main Data Results of Shanghai’s Seventh National Census. Available online: http://tjj.sh.gov.cn/7rp-pcyw/20210519/e4fb1ce32996477f8ea99869b3a98b0f.html (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Shanghai Statistics Bureau. Composition of Permanent Residents by Household Registration and Age in the Seventh Census. Available online: http://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjnj/nj21.htm?d1=2021tjnj/C0211.htm (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Shanghai Statistics Bureau. Employees in All Sectors of Society. Available online: http://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjnj/nj20.htm?d1=2020tjnj/C0301.htm (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Raco, M. Key worker housing, welfare reform and the new spatial policy in England. Reg. Stud. 2008, 42, 737–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shen, Y. Why does the government fail to improve the living conditions of migrant workers in Shanghai? Reflections on the policies and the implementations of public rental housing under neoliberalism. Asia Pac. Policy Stud. 2015, 2, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oort, F.; Weterings, A.; Verlinde, H. Residential amenities of knowledge workers and the location of ICT-FIrms in the Netherlands. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En Soc. Geogr. 2003, 94, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, P.; Murphy, E.; Redmond, D. Residential preferences of the ‘creative class’? Cities 2013, 31, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslova, S.; King, R. Residential trajectories of high-skilled transnational migrants in a global city: Exploring the housing choices of Russian and Italian professionals in London. Cities 2020, 96, 102421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.V.; Bugge, M.M.; Hansen, H.K.; Isaksen, A.; Raunio, M. One size fits all? Applying the creative class thesis onto a nordic context. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 1591–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, A.; Bendit, E.; Kaplan, S. Residential location choice of knowledge-workers: The role of amenities, workplace and lifestyle. Cities 2013, 35, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Carrillo, F.J.; Baum, S.; Horton, S. Attracting and retaining knowledge workers in knowledge cities. J. Knowl. Manag. 2007, 11, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, A.; Bendit, E.; Kaplan, S. The linkage between the lifestyle of knowledge-workers and their intra-metropolitan residential choice: A clustering approach based on self-organizing maps. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2013, 39, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Du, H.; Hui, E.C.-m.; Tan, J.; Zhou, Y. Why do skilled migrants’ housing tenure outcomes and tenure aspirations vary among different family lifecycle stages? Habitat Int. 2022, 123, 102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, S.K.; Jackson, R.J. The built environment and children’s health. Pediatric Clin. North Am. 2001, 48, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Chen, J. Beyond homeownership: Housing conditions, housing support and rural migrant urban settlement intentions in China. Cities 2018, 78, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. Incomplete urbanization and the trans-local rural-urban gradient in China: From a perspective of new economics of labor migration. Land 2022, 11, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, C. Household registration, land property rights, and differences in migrants’ settlement intentions—A regression analysis in the Pearl River Delta. Land 2021, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, Y. Understanding the gap between de facto and de jure urbanization in China: A perspective from rural migrants’ settlement intention. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2019, 39, 311–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Feng, J. Cohort differences in the urban settlement intentions of rural migrants: A case study in Jiangsu Province, China. Habitat Int. 2015, 49, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güngör, N.D.; Tansel, A. Brain drain from Turkey: Return intentions of skilled migrants. Int. Migr. 2014, 52, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, C.; Ni, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. Family migration in China: Do migrant children affect parental settlement intention? J. Comp. Econ. 2019, 47, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Hui, E.C.M.; Wong, F.K.W.; Chen, T. Housing choices of migrant workers in China: Beyond the Hukou perspective. Habitat Int. 2015, 49, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiong, C.; Song, Y. How do population flows promote urban-rural integration? Addressing migrants’ farmland arrangement and social integration in China’s Urban Agglomeration Regions. Land 2022, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Jia, Y. Resilience and circularity: Revisiting the role of urban village in rural-urban migration in Beijing, China. Land 2021, 10, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S. Does formal housing encourage settlement intention of rural migrants in Chinese cities? A structural equation model analysis. Urban Stud. 2016, 54, 1834–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constant, A.; Massey, D.S. Self-selection, earnings, and out-migration: A longitudinal study of immigrants to Germany. J. Popul. Econ. 2003, 16, 631–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.J. Employment, education, and family: Revealing the motives behind internal migration in Great Britain. Popul Space Place 2019, 25, e2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jancewicz, B.; Markowski, S. Economic turbulence and labour migrants’ mobility intentions: Polish migrants in the United Kingdom, Ireland, the Netherlands and Germany 2009–2016. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 47, 3928–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifazi, C.; Paparusso, A. Remain or return home: The migration intentions of first-generation migrants in Italy. Popul. Space Place 2019, 25, e2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Li, M.; Ma, Y.; Tao, R. Self-employment and intention of permanent urban settlement: Evidence from a survey of migrants in China’s four major urbanising areas. Urban Stud. 2014, 52, 639–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Xue, D.; Li, Z.; Shi, Z. The effects of social ties on rural-urban migrants’ intention to settle in cities in China. Cities 2018, 83, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynnebakke, B. ‘I felt like the mountains were coming for me.’—The role of place attachment and local lifestyle opportunities for labour migrants’ staying aspirations in two Norwegian rural municipalities. Migr. Stud. 2021, 9, 759–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vroome, T.; Van Tubergen, F. Settlement intentions of recently arrived immigrants and refugees in The Netherlands. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2014, 12, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbiano di Belgiojoso, E. Intentions on desired length of stay among immigrants in Italy. Genus 2016, 72, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Guo, F. Breaking the barriers: How urban housing ownership has changed migrants’ settlement intentions in China. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 3689–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Tao, L. Urban settlement intention of young talents: An empirical study of talent apartments in Shanghai. In Proceedings of the 24th International Symposium on Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate, Chongqing, China, 29 November–2 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Dong, G. Settlement intention of migrants in the Yangtze River Delta, China: The importance of city-scale contextual effects. Popul. Space Place 2019, 25, e2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, B.; Lv, P.; Warren, C.M.J. Housing prices, rural–urban migrants’ settlement decisions and their regional differences in China. Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, J. Bringing city size in understanding the permanent settlement intention of rural–urban migrants in China. Popul. Space Place 2019, 26, e2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Statistics Bureau. Main Data of the Seventh National Population Census of Shanghai. Available online: http://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjgb/20210517/cc22f48611f24627bc5ee2ae96ca56d4.html (accessed on 19 October 2021).

- Cui, C.; Geertman, S.; Hooimeijer, P. The intra-urban distribution of skilled migrants: Case studies of Shanghai and Nanjing. Habitat Int. 2014, 44, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, L.H.T.; Li, V.J. The role of higher education in China’s inclusive urbanization. Cities 2017, 60, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Li, B. Policy coordination in the talent war to achieve economic upgrading: The case of four Chinese cities. Policy Stud. 2022, 43, 443–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education Committee of Xicheng District of Beijing. Opinions on Enrollment of Compulsory Education in Xicheng District in 2020. Available online: http://www.beijing.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengcefagui/202005/t20200520_1903693.html (accessed on 19 October 2021).

- Education Bureau of Shanghai. Shanghai High School Enrollment Reform Measures. Available online: http://edu.sh.gov.cn/zcjd_gzjdlqgg/20210317/298ed2734e81400cb5df33ca961ee9a1.html (accessed on 19 October 2021).

- Education Bureau of Shenzhen. Guidance on the Enrollment of Compulsory Education in Shenzhen. Available online: http://szeb.sz.gov.cn/szsjyjwzgkml/szsjyjwzgkml/qt/tzgg/content/post_5521132.html (accessed on 19 October 2021).

- Niedomysl, T.; Hansen, H.K. What matters more for the decision to move: Jobs versus amenities. Environ. Plan. A: Econ. Space 2010, 42, 1636–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).