1. Introduction

In a world filled with diverse natural and man-made hazards that are increasing in frequency and intensity, many consequences seem frustrating. We are still facing conflicts on a global scale and peace is a challenge we must meet. Although societies are becoming more prepared for disasters thanks to advanced remote-sensing technology, disaster risk reduction strategies, and resilience strengthening supporting early warnings for disaster risk reduction, the statistics indicate that the frequency of disasters has risen because people increasingly live in disaster-prone areas [

1,

2]. Disasters may be selective, only affecting a certain part of cities or a particular sector, which may cause development differences between neighborhoods. Persistent causes make the recurrence of disasters and their devastating impact highly probable. Moreover, because completely preventing hazards may seem illogical, it is better to mitigate its effects [

3] by integrating the mitigation and adaptation principles as integral to both the pre-and post-disaster phases, thereby ensuring that societies will be safer and less vulnerable to other potential crises [

4,

5].

The real estate sector is one of the first sectors to experience a depressing state of affairs with regard to different sorts of activities including sales, values, availability, financing, constructing, and lending [

6]. Moreover, real estate is closely linked to a determined geographical location, which strongly affects property values and the balance between the sale and purchase of real estate [

7]. This may be disturbed during disasters, resulting in a spatial imbalance between urban and rural areas. In addition, contradictions pertaining to the legal element of real estate lead to conflicts between formal and informal property [

8]. The problem lies in the shortage of legal criteria for availing eligibility of sustainable life for all, regardless of location [

9]. An even worse problem is dealing with double criteria, which can be implemented by corrupt municipalities fighting the presence of weakened people on informal land, while ensuring the safety of the elite’s property [

10,

11]. This serves to reinforce the spatial imbalance as evidenced in social stratification [

12].

The spatial dimension of cities can be defined based on three basic criteria: land use pattern, population density pattern, and neighborhood unit design [

13]. However, cities are characterized by the range of energetic interactions between the social networks and physical elements, when both are subjected human activities, thereby forming the urban system [

14]. Disasters triggered by natural or man-made hazards destabilize this system as they result in the breakup of social interactions among society. Forasmuch as the main traits of a balanced community form the range of social cohesion among all its components [

15], they reflect the effective interactions between people in each spatial spot in the urban area. The effects of disasters on the spatial dimension of cities can be considered to reflect weak harmony between spaces and the people they belong to.

Research that discusses real estate issues during crises has disproportionately focused only on the economic, social, or investment aspects [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. However, despite the spatial dimension of cities not being addressed in real estate studies, it remains, undoubtedly, the key driver of balance among neighborhoods not only in a self-contained urban area, but also between rural and urban ones. The novelty and contribution of this paper is that it synthesizes the major findings within the research fields of real estate, disasters, urban planning, and spatial balance. It builds a framework for evaluating real estate activities from the perspective of spatiality before, during, and after natural hazards or hazards triggered by conflicts. The evaluation starts from discovering real estate challenges that occurred because of a specific kind of disaster—such as earthquakes as a natural hazard—wars, civil conflicts, armed violence, and forced displacement—as human-instigated hazards—or COVID-19 as a pandemic—resulting in a spatial imbalance in five different case studies (Haiti, Nigeria, Rwanda, Ethiopia, and the United States of America). They were selected based on a refinement process that relies on three main indicators combined; namely, spatial imbalance, disasters, and real estate as a major causative factor. They provide an analysis of challenges and innovations to optimize real estate in a way that is reflected in achieving balanced development.

A key question animating this research is: How can real estate be a driver of a disaster resulting in spatial imbalance? This leads us to another question: How can real estate be a tool for achieving socio-spatial balance in the context of urban recovery among both developing and developed communities? Moreover, how can it also be a guarantee for sustaining stability? In order to answer these questions, three directional hypotheses were proposed to achieve spatial balance among urban areas, derived from the theory of neighborhood units by Clarence Perry (1929) and the theory of Broadacre City by Frank Lloyd Wright [

23,

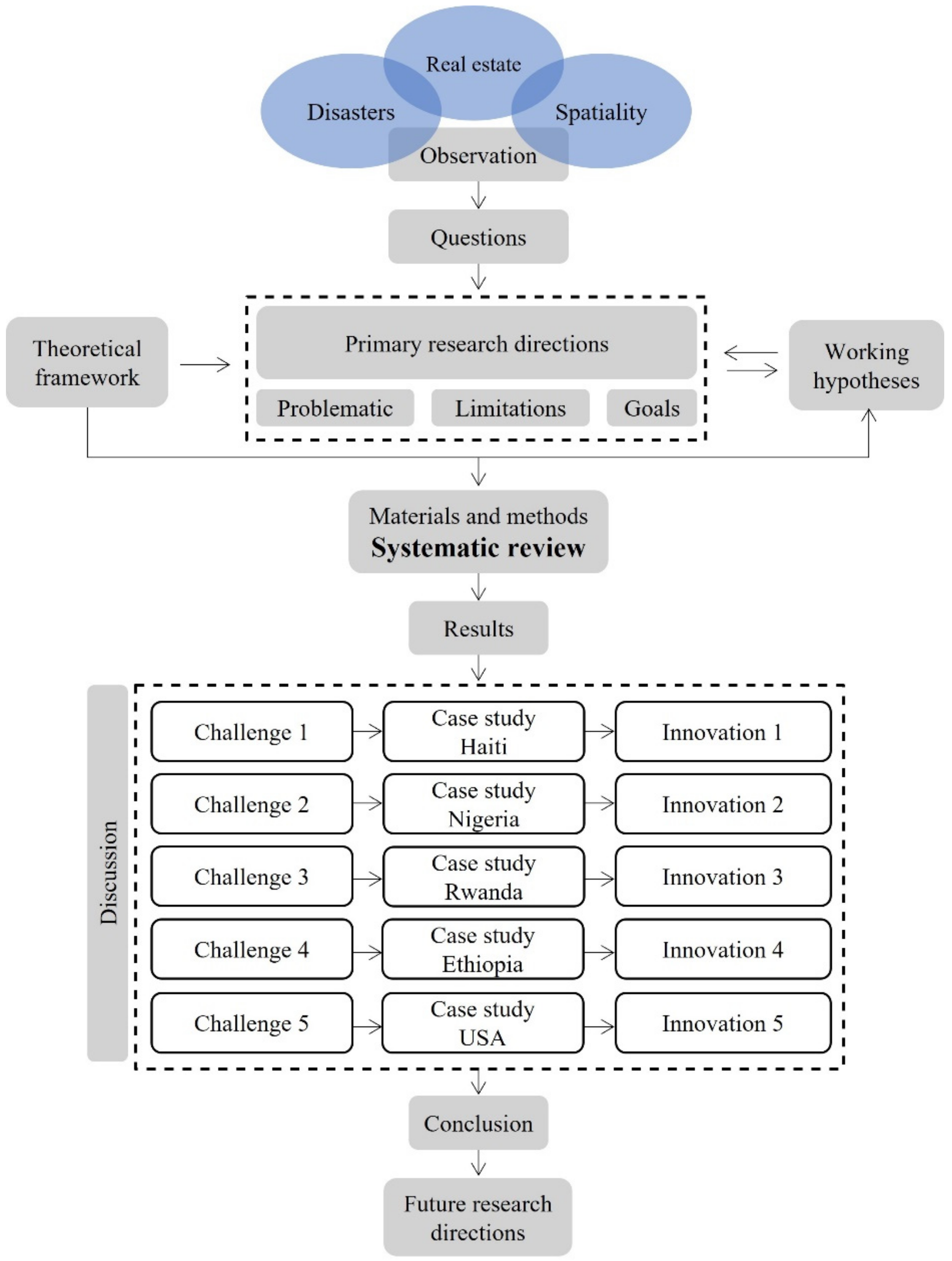

24]. The first hypothesis states that the equitable performance of real estate legislation is an eminent instrument of protecting property rights. The second hypothesis supposes that the demographic change is a factor in aggravating real estate imbalance. The third hypothesis states that the decentralized real estate administration system promotes balanced spatial association according to urban requirements more than the centralized one. The diagram below illustrates the sequence of the systematic review process followed in this paper (

Figure 1).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

The conceptualization of this review paper begins with the identification of sources and prior cases, which were addressed from the perspective of the research direction. Despite the wealth of research conducted in the field of real estate, discovering the spatial impact of real estate on urban areas during disasters requires careful investigation to collect the most narrowly defined references and case studies that impact the topic of research.

The search strategy undertakes a comprehensive approach to identify literature that meets the eligibility criteria in terms of effectiveness, meaning that the searches for evidence should be adequate to collect relevant studies that provide candid answers to the research questions. The starting point for operationalizing a search strategy is PICO concepts (Problem, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes) that further assist in deepening the process of literature collection. To make the search strategy as extensive as possible, a bundle of principles that were customized for each database to be sure that relevant records are not missed:

Break the research concept into more subconcepts and include a wide range of terms for each one;

Follow an iterative process, in which the searching terms can be improved;

Use a multi-faceted approach with a series of searches and a variety of concepts;

Pay equal attention to subject aspects and the study design of the selected studies;

Avoid arbitrary spatial or temporal restrictions that degrade the comprehensiveness of the search process. However, look out for the relevant time periods and geographic locations of selected case studies, in a way that promotes the precision of collecting relevant studies;

Include both randomized and non-randomized studies;

Strike a balance between comprehensiveness and precision by a quick ascertaining the potential relevance of article abstracts.

Google Scholar, an initial database, was used to obtain resources written by well-practiced academics and seasoned professionals, published either in reliable refereed publications or websites of research institutions concerned with issues related to the research topic. In addition, SAGE, The Web of Science, and SCOPUS databases, as well as EBSCOhost research platform, were also used to pursue more refined research terms and access the best-in-class publications. The Boolean operation (OR, AND) was used to combine search terms to make the literature search process more specific (

Table 1). The snowball method helped expand and accelerate access to relevant research.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The criteria had to be met to evaluate real estate issues; they included studies that described: (a) real estate categories (residential, commercial, or vacant land); (b) aspects of study (social, economic, political, or geographical); and (c) the nature and impact of changes caused by disasters on real estate. The relevance of the research objectives, quality of content, and clear presentation of data were also consistent criteria for evaluation. The examination of the data depended on the qualitative method of analysis used to evaluate real estate spatial effects, namely whether it is direct or indirect, ostensible or tacit.

The exact inclusion and exclusion criteria among reviews to synthesize our findings based on a transparent and reproducible approach to collect studies that make high-quality practical or theoretical contributions, which provide reliable findings from which clear challenges or innovations can be drawn (

Table 2).

3. Theoretical Framework

Urban planning theories charted the course of human functions starting from a small neighborhood and evolving to a wide region and into the spatial, physical, and social aspects of society.

The Neighborhood Unit monograph by Clarence Perry is considered one of the first theories that sought to determine human interaction within neighborhoods by applying physical design parameters. The core of Perry’s theory is establishing an ideal neighborhood as a physically defined unit in terms of the right of possession or fair access to city functions [

25]. This has strengthened the acceptance of Perry’s theory in the real estate industry because it incorporated the owners’ interests and community amenities with comprehensive planning objectives and was driven more by sociological concerns than commercial ones [

26]. This indicates the ease with which Perry’s concept can be applied to the investment of real estate developers based on stability, which promotes the development of the neighborhood as a self-contained unit in the city [

27].

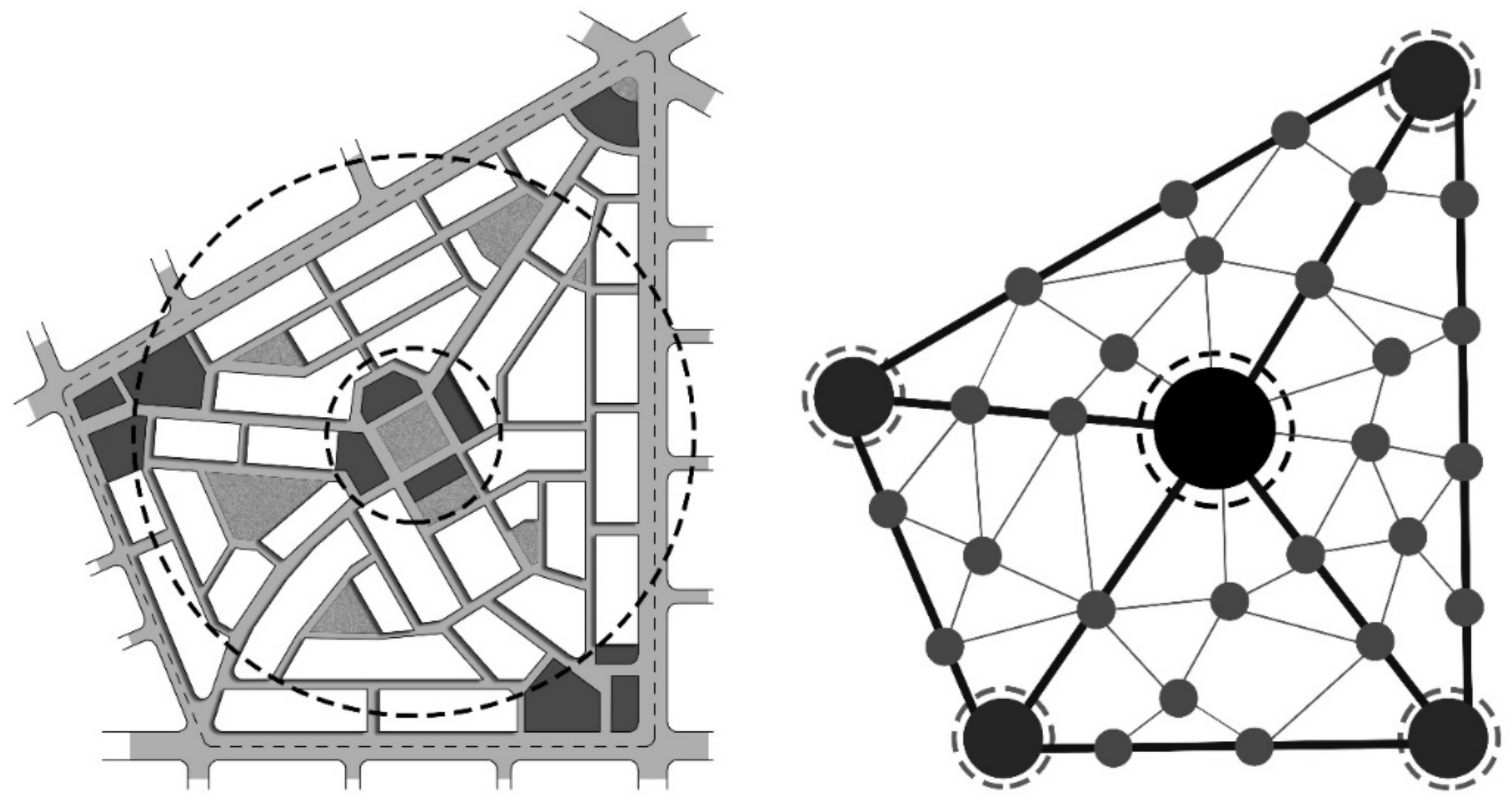

According to the balanced spatial distribution of facilities in Perry’s theory (

Figure 2). The important impact of neighborhood unity on enabling balanced development without discriminatory considerations can easily be realized, especially in the post-disaster phase, which urgently requires a social balance strategy [

28]. Thus,

The Neighborhood Unit monograph is a flexible concept that can be applied to the physical, social, and political variables of cities. Despite being widely criticized as a stereotyped theory, it can be recommended as a futuristic concept for urban growth, due to the satisfaction for all in the residential units [

29]. Hence, this theory was adopted to regenerate cities after disasters. For example, in post-war Britain, planners sought to inspire the ethos of the community in a way that ensured social and spatial balance in urban areas, despite initial concerns about social cohesion associated with the geographical location of services [

30].

This paper is based mainly on the theory of neighborhood units, but it also considers the Broadacre City concept by Frank Lloyd Wright as a good example of ensuring spatial balance in society, since it implies applying the principle of equitable distribution of land ownership among people based on uses or needs [

31]. This reduces unchecked real-estate speculation and protects land value [

32].

Understanding the Impact of Disasters on the Spatial Dimensions of Cities

The spatial dimension of the city represents the first obvious impression, because cities’ spatial configurations such as population density and housing ratio have urban characteristics that can be discerned spontaneously [

33]. Although the spatial patterns of cities differ, a specific trend of sustainability recommends that the city’s spatial pattern move toward the compact shape, reflecting the importance of functional efficiency in terms of transportation as well as social and cultural interaction [

34]. In contrast, the spatial patterns of cities in developing countries are vulnerable to urban changes owing to frequent variations of the social and economic systems [

35]. Therefore, the spatial patterns may differ between cities in developed and developing countries, between strong and cracked economic cities, and even between sociable and ultra-conservative cities.

The effect of disasters can have varying impacts on the urban fabric in developing countries based on their economic state, social cohesion, living standards, and well-educated community [

36]. If these countries have poor socioeconomic indicators, it would make the cities’ spatial structure vulnerable to collapse at any time, resulting in crisis-prone cities with an unhealthy atmosphere. To a large degree, some cities in developing countries are characterized by social disparity, as evidenced by the urban and architectural differences. The physical vulnerability of poor neighborhoods makes them vulnerable to the catastrophic implications of disasters [

37]. All of this leads to an imbalance on the spatial dimension of the city, which is a powerful indicator of the post-disaster recovery process. In this paper, the role of real estate will be reviewed within the context of previous spatial indicators during the disaster period (

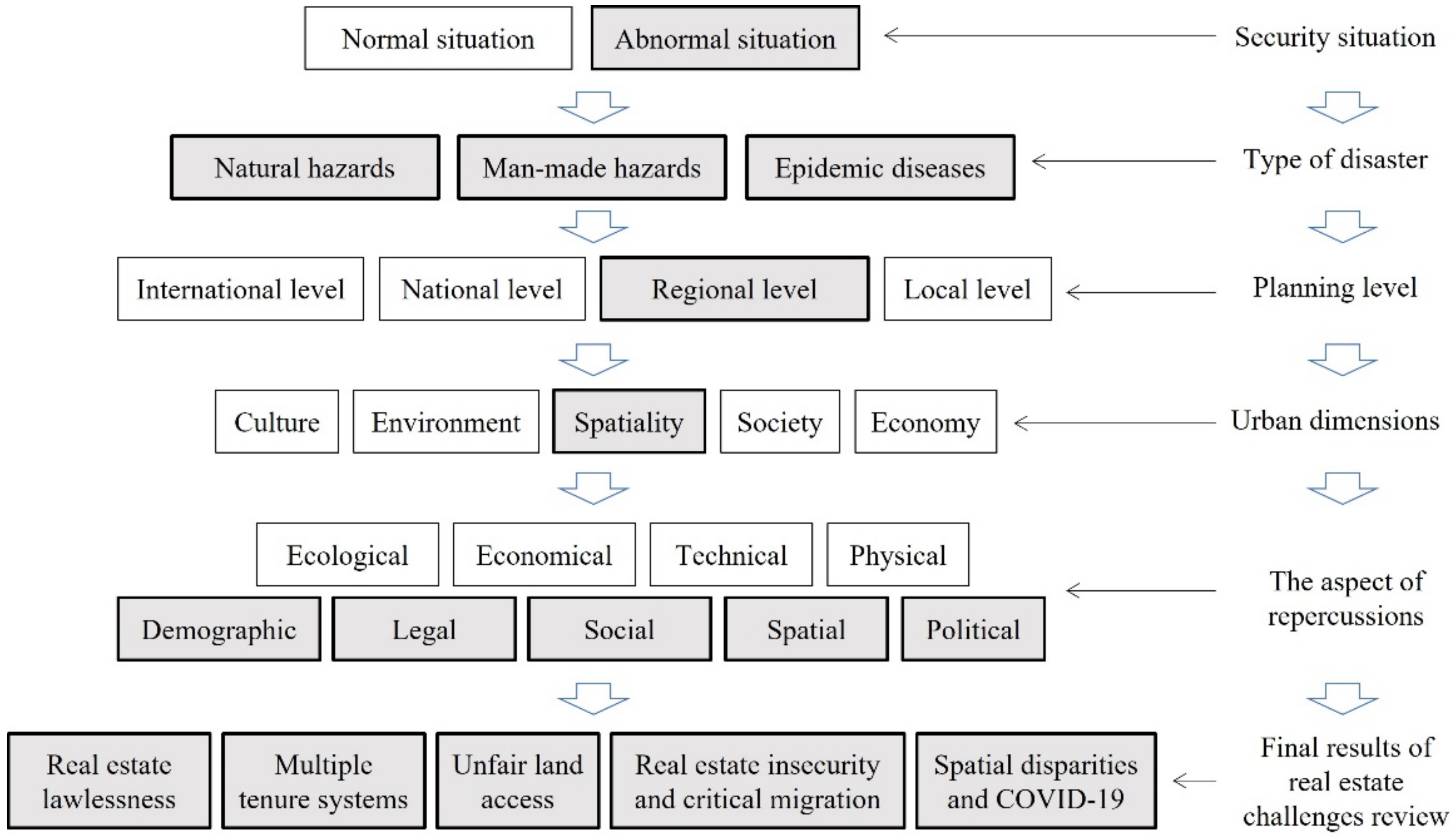

Figure 3).

4. Results and Discussion

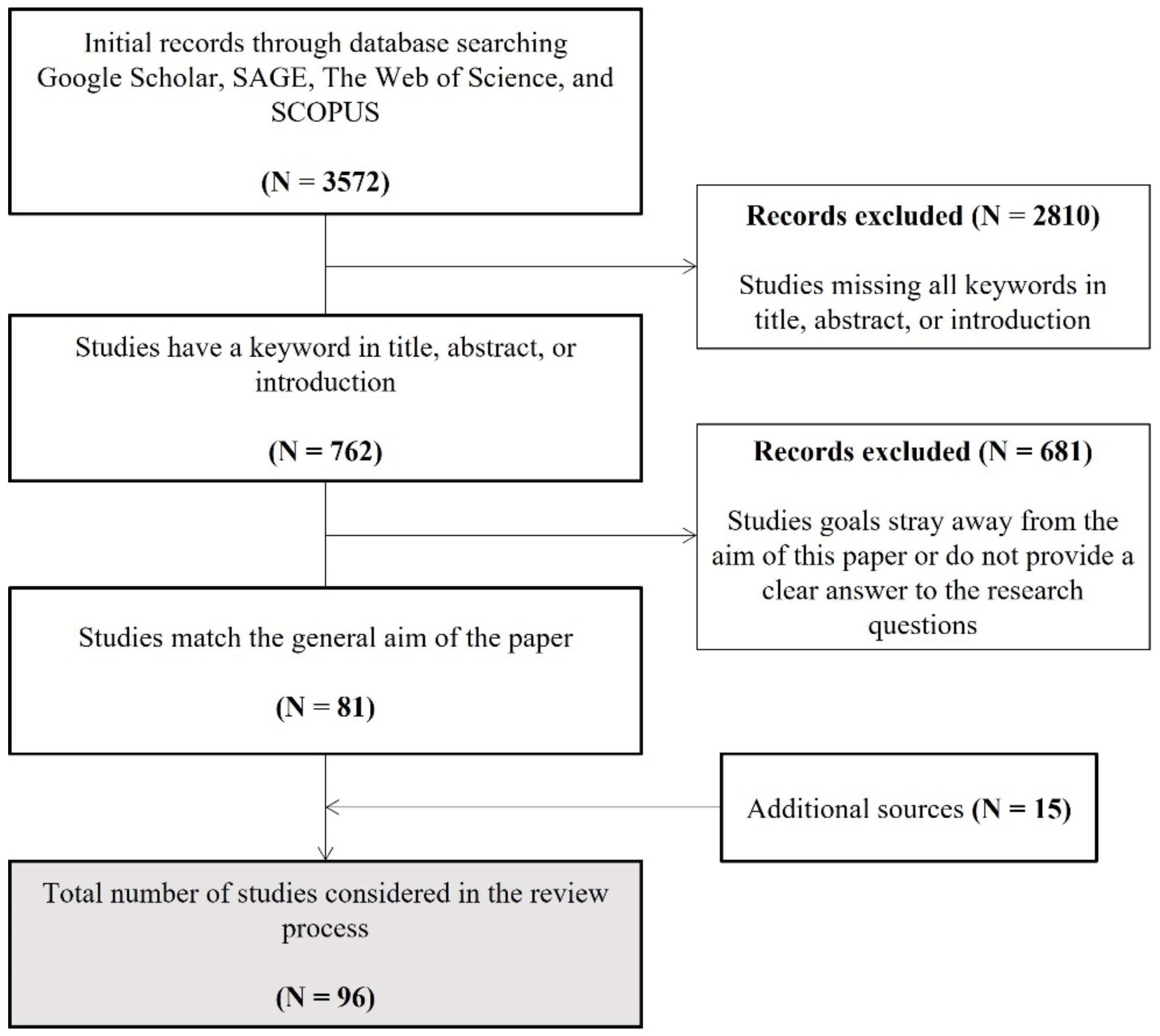

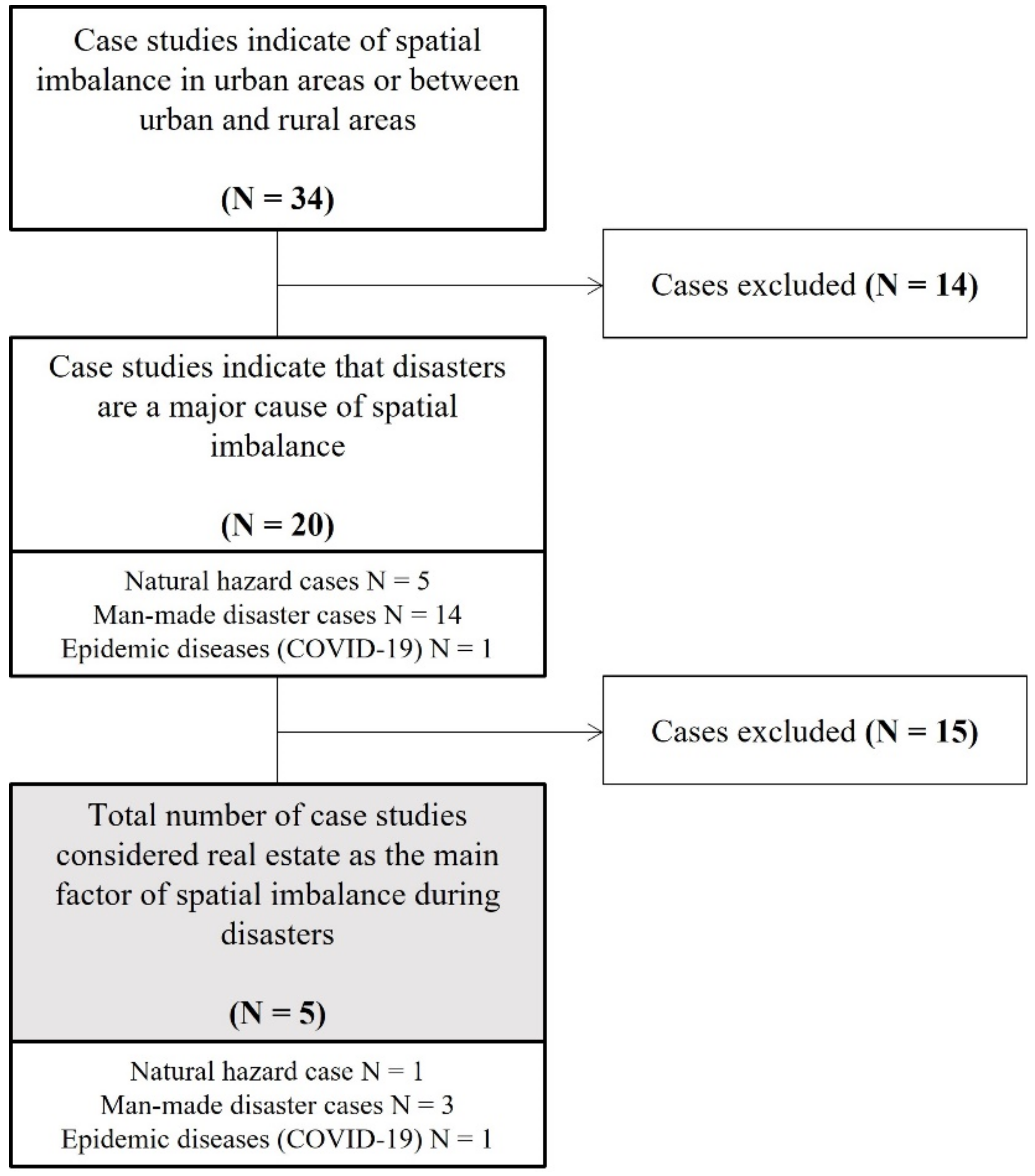

The total number of studies retained from the initial search was 3572. After the first refinement that considered mutual keywords, the number of studies decreased to 762. The second refinement focused on the intersections of study goals with the aim of the paper, resulting in several eliminations to reach 81 studies. In addition, 15 other research items were added from certain official reports, bools, and websites, thus bringing the total number of studies reviewed in this paper to 96 (

Figure 4).

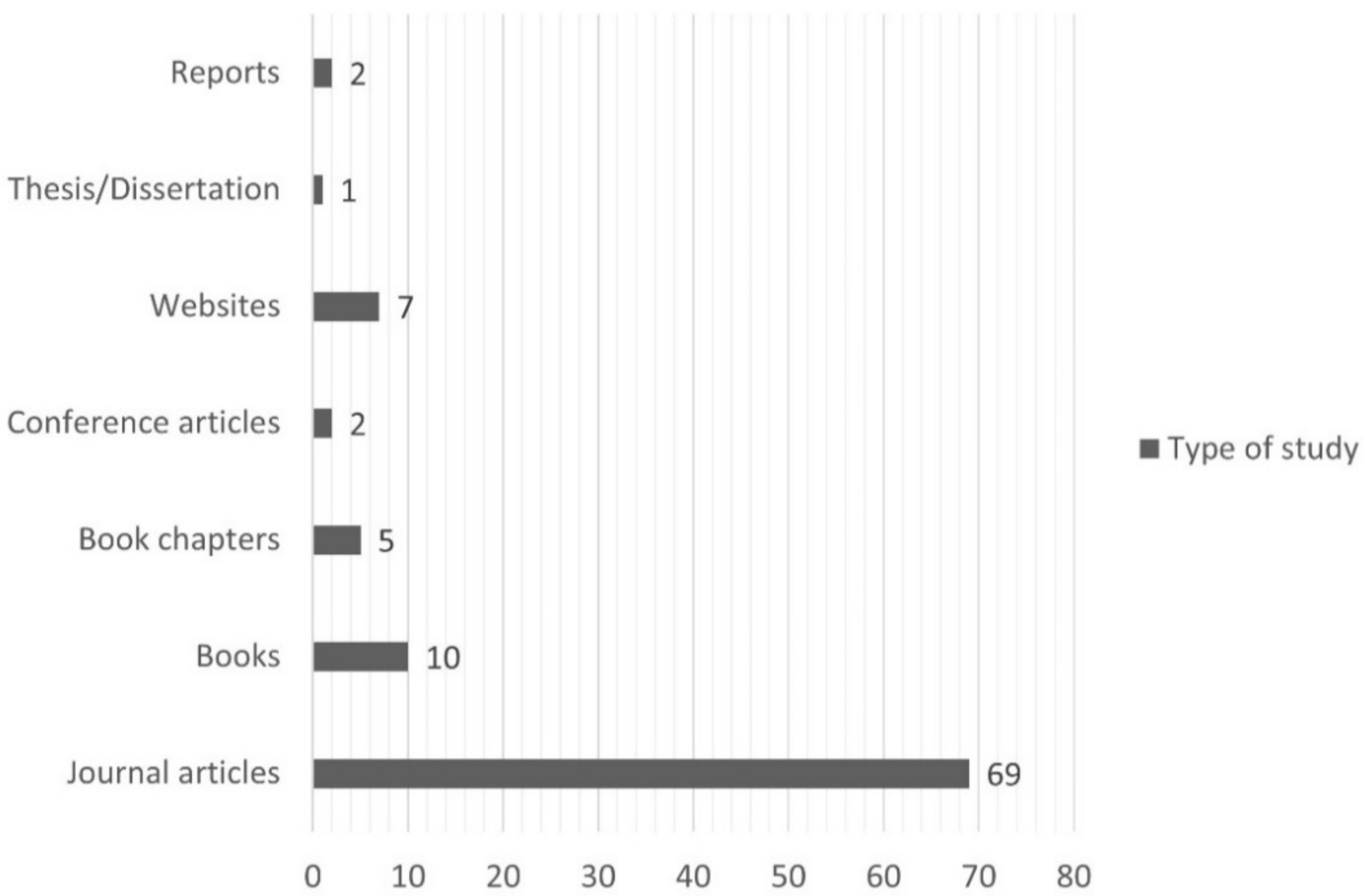

The characteristics of the reviewed studies were divided according to the type of source, although most were from articles in journals (70%) such as

Critical African Studies,

International Planning Studies,

Journal of Geomatics and Planning,

Journal of Land Management and Appraisal,

Disasters, and

Journal of African Real Estate Research. Other sources (30%) were distributed among books, conferences, reports, and official websites (

Figure 5).

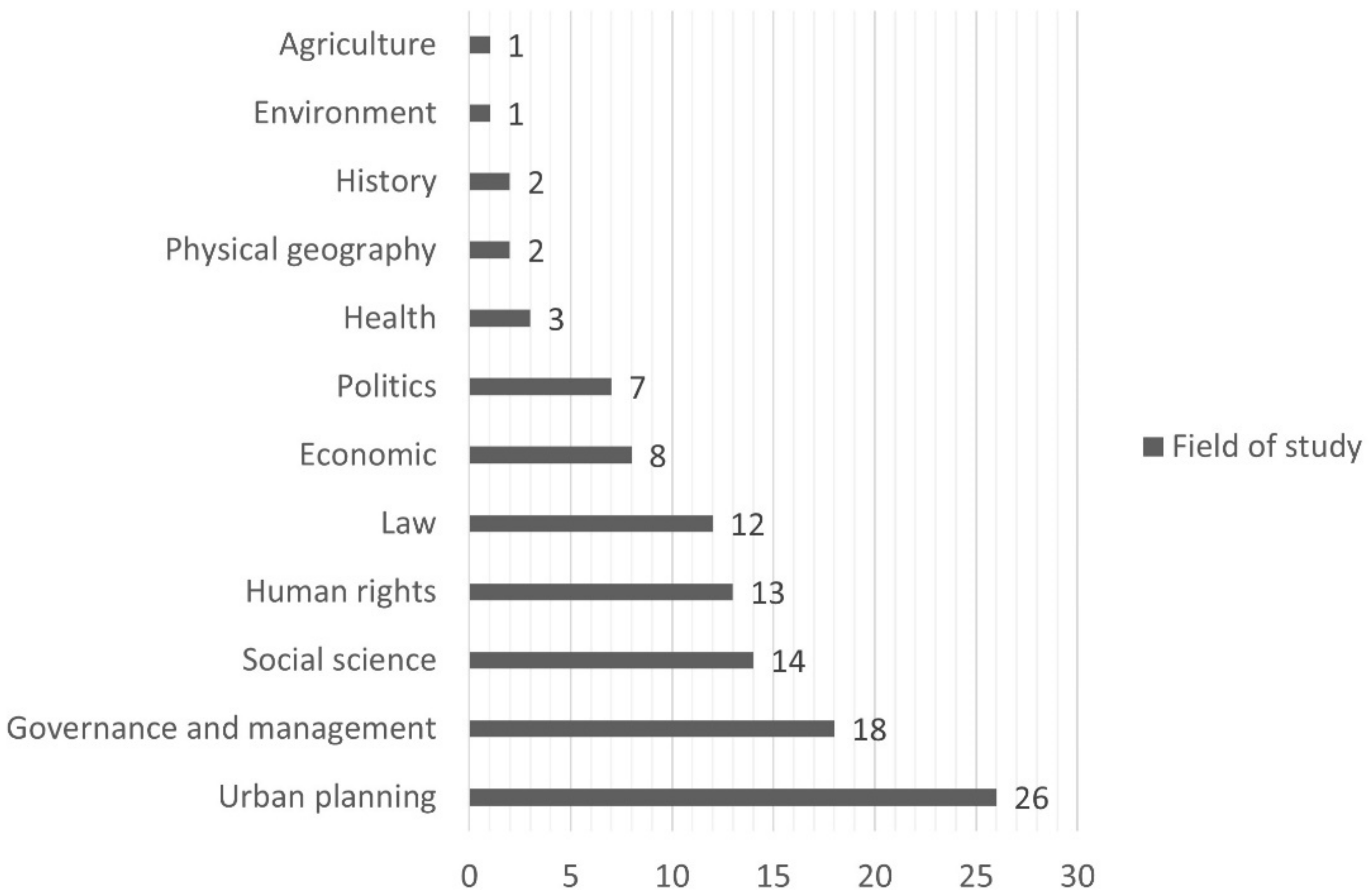

The largest share of studies came from the field of urban planning, governance and management, social science, and human rights (26,18, 14, and 13 studies, respectively), although a substantial proportion focused on the fields of law, politics, and economics. However, only few studies were concerned with physical geography, health, history, environment, and agriculture (

Figure 6).

Evaluating the strength of argument provided by the collected literature depends on the journal quartile rankings that consider the impact factor, citation, and indexing distribution of each journal. The evaluation process indicates that 61% of papers belong to the top quartile (Q1) journals, while fewer fall within the middle-high (Q2) and the middle-low category (Q3), with 14% and 9%, respectively. The search process revealed few working papers, conference articles, and papers belonging to relatively new journals that lacked classification accounted for 16%. The last ones may be regarded as the least scientific influence. However, it was important to keep them in the systematic review due to the significant local data provided in selected case studies, as well as the contribution to clarifying local perspectives that open the discussion of the issues involved. Accordingly, they enhanced thoroughly the answer to research questions. Furthermore, those studies were subject to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for assessing the certainty of argument in literature. The strength of evidence promoted by testing considerations about causality, directness, homogeneity, and precision of argumentation with research questions.

4.1. Real Estate Challenges

Real estate development is a process that encompasses a complex chain of approaches, properties, and outcomes that shape the built environment, in which people live and interact. Accordingly, it is very likely that real estate challenges may arise with the potential to transform the socio-spatial and economical character of urban and rural neighborhoods. Recovery is a straightforward process, but the physical impacts of disasters vary across areas [

38]. Therefore, we examine how the spatial performance of real estate varies across different types of disasters.

To achieve spatial balance in post-disaster nations, we should first analyze the refinement sequence that followed in order to identify the exact challenges, among many, to real estate in the context of improving the spatial balance approach in disaster-prone urban and rural areas. The results revealed five main challenges: (1) real estate lawlessness, (2) multiple tenure systems, (3) unfair land access, (4) real estate insecurity and critical migration, and (5) COVID-19 as a global pandemic (

Figure 7).

Based on the aforementioned refinement, the systematic review process for the five real estate challenges used a number of diverse sources in terms of study fields, document type, disaster type, and study area (

Table 3).

4.1.1. Challenge 1: Real Estate Lawlessness

Real estate-related legislation can be viewed as a guiding compass for peace in post-disaster areas, by promoting compatibility with the emerging realities of properties and making real estate law a deterrent to the questionable legitimacy of local authorities that may be working in favor of one side over the other [

10]. Therefore, the laws that are formulated during or after a disaster to address a specific problem must reflect a wise portfolio of legislation and serve as a protective shield of human rights. This portfolio must include strategies and policies concerned with prevention, insurance, reconstruction, and emergency response issues [

39], based on fair legislation in achieving a balanced real estate administration and promoting institutionalized social justice for all parts of society during and after a catastrophe [

12].

In light of the direct bearing of law on society, the spatial dimension of cities may be affected by the aftermath of social changes through the loss of rights due to different geographical locations. The spatial dispute may also emerge when laws are linked to unstable social rules, which may occasionally be termed “customary rules” that may, under abnormal circumstances, be subject to manipulation according to private interests [

12,

39].

4.1.2. Challenge 2: Multiple Tenure Systems

Multiple tenure forms often emerge due to the duality of formal and informal types of tenure systems according to the differences in geographical location, societal traditions, and urban differentiation. The formal one can be considered the most credible type due to documentation proof and institutional reliability, but it may not be the most dependable form, whereas the informal tenure may be more effective at controlling tenure issues locally and on-site, especially for people who lost their documents during the disaster or others who lost their properties [

40]. However, apart from the reason of multiplicity, what is certainly true is the profound impact of disasters on real estate and property rights [

41]. Furthermore, the inconsistency between the land administration systems within the self-contained metropolitan areas may lead to chronic conflicts over land and other types of real estate, particularly when it is associated with developmental differences and accompanying factors, such as overpopulation and urban sprawl [

42]. Thus, spatial and social crises arise as a consequence of this contrast, namely, variations in the standard of urban living conditions, high rates of violence, and overcrowding [

43].

4.1.3. Challenge 3: Unfair Land Access

Land access is the process by which people use lands productively in formal or informal markets, those controlled by the state authority, the official constitution, or the customary legislations [

44]. Urban areas may be exposed in this respect to aggravating factors, which disrupt their spatial balance, as evidenced by the disparity in land scarcity or in the ability to access land in a specific area more than in another. One reason for this urban disparity is overpopulation resulting from the rapid increase in demographic growth [

45]. However, disasters have chronically affected land access by increasing landlessness and the corresponding inflation of individual land holdings to favor a small number of people in society. This can be portrayed as an urban spatial imbalance, derived from sharp disparities in property values [

46].

Land access can be understood based on three aspects according to its effects on spatiality. The first is related to land use inconsistency, the second relates to the inequality in the distribution of the land output, and the third concerns the bias in making decisions over land or the other types of real estate [

47]. Therefore, the strength of land access lies in the stabilization of property assets owing to the significant role of ownership to confer security in post-disaster recovery and provide relative stability to social contingencies [

48]. Thus, the community will be more balanced as long as real estate properties are divided adequately with fair access regarding the usage, possession, or decision-making pertaining to real estate.

4.1.4. Challenge 4: Real Estate Insecurity and Critical Migration

Real estate security has always been viewed as an extremely complex issue due to the reciprocal spillovers that are likely to interact with changing human conditions during disasters triggered by natural or man-made hazards, particularly regarding the security of tenure, use, and value of the land in as much as its role is to reinforce stability in the post-conflict phase [

49]. Furthermore, the real estate tenure system could reflect the social, economic, and political values of the community, especially when it is guided by democratic and decentralized methods of fair land distribution. Otherwise, the spatial connections among society will wear out due to the mutual relations between displacement and insecurity, which will increase migration rates through the rise of the pull factor of urban areas that have a more secure tenure system and, conversely, the rise of the push factor of areas have an insecure tenure system [

50].

This is conspicuous in east Africa, where land conflicts are accompanied by outbreaks of violence, which occur in response to orchestrated dispossession processes organized by those who seek to retain a monopoly on power and maintain their grip on real estate control [

51]. Such acts force people to migrate to other areas where they may feel a sense of sustainable security in terms of their lives and possessions [

52]. The communal real estate tenures that were promoted under the colonial administration in Africa, and then under multiple African leaders who sequentially altered the control of power in many African countries, can be considered as an essential reason of migration, driving the shifting of ideologies and belongingness of place among society [

53]. This type of tenure in transitional societies causes a lack of security of property rights because there are no regulatory guidelines responsible for determining the right holders and those who are landed or landless [

54]. This sort of practice led to differentiation over land that caused the blurring of the meaning of spatial affiliation.

4.1.5. Challenge 5: Spatial Disparities and COVID-19

Throughout history, the outbreak of pandemics is followed by a bundle of seemingly random repercussions which are nevertheless associated and showed a heightened sensitivity to urban-rural disparity [

55,

56,

62,

63]. The COVID-19 is a pandemic that impacts almost every vital sector and triggers abrupt changes brought on by the acceleration of social and economic interaction in urban life [

57], that lead to substantial implications on the use, value, and tenure side of real estate, which affect the appraisal and valuation processes. The disruption in the property markets due to locational preferences and shifts in real estate demand. Many rural residents claim to be isolated with limited access to services. Conversely, urban residents escape from densely populated areas to areas that provide them with more natural outdoor spaces, especially when they ensure that their work is facilitated by working from home [

58]. Lockdowns have changed the range of spatial interactions. Since optimizing the productivity of working from home, dense urban locations are the most vulnerable to a decline in real estate values due to the fall in the rent flexibility with respect to the density [

59]. Conversely, it can be argued that remote areas remain the most vulnerable, with high rates of infection and mortality. Due to the high housing density, poor health services, high levels of informality [

60], and high air pollution. The effects of have been more catastrophic for poor urban, thereby exacerbating socio-spatial disputes [

61].

4.2. Related Case Studies

In this section, we provide a systematic review of five case studies that reflect the aforementioned challenges on-site (

Figure 8). These cases were selected based on the refinement process, which began by observing the spatial imbalance indicators caused by disasters, and then the role of real estate in this context. The process indicated that the aggressive approaches to conflict—such as repression and forced displacement—are the top issues affecting spatial balance of real estate. Post-colonial states of Africa experienced land conflicts for a long period of time, which caused long-term impacts on spatial differentiation of real estate [

64]. Therefore, the refinement process resulted in three African case studies related to man-made hazards, whereas it indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic has generated a complex shock on real estate in most economically strong countries like the United States of America [

59,

65,

66], which is noteworthy to review the emerging real estate challenges and innovations to address COVID-19. In terms of natural hazards, the Haiti earthquake was identified due to complex intersections of real estate, destruction, and legal deficits. This can be seen as a rich case study for reviewing challenges and innovations (

Figure 9).

Before discussing the case studies, it is important to reveal the characteristics of the selected studies in the review process (

Table 4).

4.2.1. Case Study 1: Real Estate Lawlessness in Post-Earthquake Haiti

Post-earthquake Haiti has witnessed various real estate problems owing to the widespread lack of formal registration documents of real estate, in tandem with the lagging of institutional reform, which implies an over increase of impunity and threats to the safety of properties [

68]. In addition, spatial dysfunction has increased the pressure on host communities as a result of rural-urban movements alongside unregulated urban growth (

IASC, 2010). However, these real estate problems were complicated due to the preceding disruptions even before the earthquake occurred, such as unequal distribution of land, absence of the enforcement of property rights, and double standards of real estate legislation, which often resulted in conflict between the formal and informal form of tenure, particularly regarding issues related to the levying of property taxes [

9].

Key drivers of spatial imbalance in Haiti are the social division between the urban and rural areas, which were further entrenched by the politicization of the judicial system [

11], and the lack of access to justice due to the uneven spatial distribution of courts, which affects a considerable number of citizens because the geographical location of courts has an impact on the distance and the cost of reaching courts [

9]. Another factor is the quantitative and qualitative deficit of courts specialized in real estate, because there exists only a single central court specialized in land, resulting in failure to effectively deal with real estate issues in Haiti [

69].

4.2.2. Case Study 2: Multiple Tenure Systems in Lagos State, Nigeria

Nigeria has witnessed many natural and human-induced hazards, leaving behind widespread economic and social deficits [

70]. In spite of that, Lagos State’s landmass has expanded over the years and has begun to annex adjacent rural real estates. This expansion increased the conflicts between the formal land administration system and the informal one, which was still being followed in rural communities. The formal administration can be better secured because title documentation is guaranteed by authorities, thereby automatically fostering the proper layout of urbanization, promoting values of real estate, and stimulating sustainable investment in the real estate sector. Nevertheless, the formal administration form fell into the trap of social discrimination in many areas of Lagos State due to the biased allocation of land for the rich [

72].

Notwithstanding that, the worst impacts of property disputes in Lagos were undeniably caused by the informal land administration and customary tenure arrangements that were not protected by law and vulnerable to external pressures [

71], as reflected by the usual contentious land boundaries, causing conflicts between owners owing to the difficulty of ascertaining the titles’ roots, thereby allowing an uncontrollable adjustment of real estate limits. This consequently leads to unsecured tenure rights because they are not straightforward, and unofficial documents cannot be accepted in investment choices. Despite that, traditional perspectives consider the communal administration to be safer because real estate disputes are more easily resolved through alternative mechanisms under the power of chiefs of the community. Moreover, the informal system is still decentralized, meaning that the land issue can be solved separately, which promotes social integration and preserves customs that make people feel safer [

72]. To sum up, there are two main aspects of disputes in Lagos: the substantial proportion of land rights, which still follow customary tenure systems, and the government’s desire to formalize the ownership to ensure well-planned urban expansions with the intention of encouraging new investment. The multiplicity of land administration systems in Lagos was the main reason for the spatial imbalance between the urban center and the surrounding areas.

4.2.3. Case Study 3: Unfair Land Access in Post-Conflict Rwanda

The African nation of Rwanda has experienced several crises during the second half of the twentieth century, represented by a lengthy period of repression, which ended with the genocide in 1994. The repercussions of this devastating tragedy resulted in dramatic demographic changes due to forced displacement [

73]. In the post-war period in Rwanda, many people who fled from the crises returned in 1997 claiming their property that had been occupied over time as a result of being unused. At that point, the crisis of land scarcity emerged when the government tried to find a suitable solution for the urgent housing crisis. The official policies revolved around two proposals: the first one involved using public spaces, such as Akagera National Park, and the second one was based on the principle of land sharing [

74]. This sparked the crisis of land disputes, especially with the intervention of the power of money to satisfy greedy needs, which led to the spatial imbalance between rural and urban areas as well as the stark diversity between livelihoods in Rwanda [

83].

In addition, Dawson (2018) studied the inequality factors between two rural areas in western Rwanda, revealing that socioeconomic power is the most influential factor in terms of the social inequality of accessing lands and services in Rwanda starting from the household level. Even more significantly, the aftermath of the conflict extends beyond the land access challenges to include valuation and use land, because both long-term residents and returnees have different land use practices. This means that their different lifestyles have influenced their land, in a way that effectively meets their aspirations, resulting in spatial and social segregation between the two areas [

76].

Therefore, it can be said that the conflict in Rwanda has caused land access challenges by limited the area available per capita. After the genocide in the 1980s, making money was the most important force to acquire real estate and control of land markets. This was accompanied by purchasing lands illegally [

75], instead of focusing on tapping into the power of traditional customary cohesion in the human relationships among the Rwandan community. Those deeds were spurred by the normative discordance of the local real estate tenure system, which exacerbated the spatial imbalance between urban and rural areas, leading eventually to regional disparity [

77].

4.2.4. Case Study 4: Internal Migration and Real Estate Insecurity in Ethiopia

Ethiopia remains one of the poorest countries in Africa after years of conflicts over real estate that have always been the real source of political power. After ousting the imperial regime, the military government followed the system of periodic land redistribution based on the need and size of each family but without the private ownership of property, meaning that people did not have the right of sale or lease. Therefore, land tenure insecurity was prevalent due to the loss of official documentation of real estate and there was no official reallocation of properties [

80]. This period was viewed as a key dividing point in Ethiopian land tenure due to the variations in land practices between southern and northern parts of the country before 1975. The Rist system in the north was characterized by the communal possession of land with inegalitarian, suspicious, and competitive traits that prioritized political considerations. However, in the south, land tenure was the more formal land titling in tandem with improving the orientation of organized and efficient urbanization [

78]. Despite the new land reform system that accompanied the new regime after 1991, the traditional land management method remains unchanged under the main control of the government as an obstacle to land market development and land tenure security [

79].

Apart from the real estate tenure variations that increased the proportion of the landless, the country has also experienced massive immigration flows over time, particularly during civil conflicts between 1984 and 1994, which forced a greater exodus of people from war-prone areas than ever before. This exodus, however, was mostly a short-distance urban–urban migration (49.3% migrants). Addis Ababa had the highest in-migration rates due to the accelerated urban growth, whereas Amhara witnessed few immigration movements. Moreover, the connectivity between cities remained inadequate in terms of quality and quantity [

81], causing the accumulation of human density in determining urban areas without considering other areas, resulting in spatial imbalance and regional variations.

4.2.5. Case Study 5: Rural-Urban Differences in the United States of America during COVID-19

Since the virus struck in the US, the urban structure has been affected substantially due to the fear of crowded places and working from home. This encouraged people to prefer moving to less dense areas [

66]. Housing as well as real estate stock market have a high rate of sensitivity for risk factors since the outbreaks of COVID-19 [

82]. Moreover, a downward-sloping rent gradient reduced the density value by a significant amount [

59]. Consequently, the spatial differentiation in the property valuations has caused urban disorder because of the decline in property tax revenues in city centers resulting from stagnation in prices, while the outskirts will be less affected due to increased valuations for properties and rising prices [

66]. Nevertheless, it can be argued that rural communities are at risk of higher rates of mortality owing to less-diversified labor and real estate markets, weak health services, and heterogeneous rural communities, resulting in long-term social and economic effects, which may reinforce rural-urban differences [

57]. Thus, the post-COVID-19 vision must consider spatial variation in pandemic vulnerability for a healthier and more balanced community.

4.3. Real Estate Innovations

In this section, we reach the last part of the review process and describe the real estate innovations for achieving spatial balance in the five case studies mentioned above to provide an overview of proposals formulated to achieve spatial balance in disaster-affected areas.

Table 5 depicts the innovations of each of the studies reviewed.

4.3.1. Real Estate Innovations in Post-Earthquake Haiti

Land Regeneration Concept

“Overcoming Land Tenure Barriers” is an initiative of the Organization for Migration in Haiti. It aims to address the post-earthquake tenure challenges by ensuring equality among cities and balancing use in housing and infrastructure. This project is divided into three stages: the first stage involves gathering data regarding the catastrophic effects on ownership and analyzing proposals of temporary settlements for the displaced [

84]. The second illuminates the legal occupancy of real estate in affected neighborhoods and determines who owns the actual property rights and who violated the rights of others. The next step addresses conflicts with the help of Shelter’s legal team that is guided by a flexible legal standard that aims to discover the root cause of real estate vulnerability in disasters according to local specificities. It is also responsible for recording property claims, identifying cases that need property dispute resolution mechanisms, and providing legal assistance for returnees [

41].

Access to Fair Adjudication

The Haitian government enacts a modern post-disaster strategy through formal legal reform—as a response to the inaction of the legal system—to uphold the strong judicial decision. Case in point: the role of legal representation for victims of forced eviction has been promoted in the court to encourage return and support fair compensation. Another plan conducted by the Haiti Property Law Working Group includes local and international actors concerned about creating a modern cadaster system as legal proof that protects human rights [

40].

Due to the profound schism between the formal and informal justice systems, multi-stakeholders justice has become dominant, particularly when social systems substitute partly for the rule of law [

85], by which the majority is unable to access real justice. In this regard, a research workshop hosted by a Haitian research institution titled “Mapping Justice and Rule of Law in Haiti” to optimize the practice of the justice system by fostering cooperation between civil society, government, and the international community, as well as experts from different countries, have a similar case to listen to foreign counterparts and consider the possibility of applying them in the Haitian context [

11].

4.3.2. Real Estate Innovations in Post-Conflict Lagos State: Resetting the Legal and Institutional Framework

The government of Lagos State established a new directorate of land regularization supported by the Security Justice and Growth (SJG) program. It provided the means to secure people’s rights by granting statutorily recognizable real estate documents, thereby helping to solve the problem of land tenure pluralism. The land regularization directorate in 2006 enabled more than 6000 people to regularize their property and reach the realm of statutory titling, thereby achieving a balance in access to development for all of the owners [

86]. Therefore, the land regularization concept contributed to bridging the gap between a statutory system of land tenure and diverse customary systems to reduce the possibility of conflict between formal and informal real estate over the entire geographical area of the state. Additionally, the importance of adopting an equitable land administration system driven by innovation should be emphasized, as it promotes a fit-for-purpose approach. Simultaneously, it ensures that citizens can make an efficient and transparent contribution to the land administration system, while also ensuring the balanced distribution of social benefits with regard to the spatial aspect of community to eventually promote fairness and equity in land access, the relocation process, and organizing rights [

87].

4.3.3. Real Estate Innovations in Post-Conflict Rwanda: Land Readjustment Concept

Land access after civil conflicts is riddled with repressive inequality owing to the increasing economic and political ascendancy. In response to unjust behaviors after conflicts, the land readjustment process to achieve social empowerment in Rwanda can be viewed as an appropriate conceptualization in contemplating how spatial balance can prevail over the urban area and its rural surroundings because land policy has considerably changed the way land access was dealt with after the conflicts, since the most important share of land in Rwanda lies in hands of the rich elite [

89]. Land consolidation is the first step that operationally regroups plots of land into objectives concerning changing the land division strategy to obtain more appropriate use [

88]. Then, the distribution process for landless people, who were refugees and returned after the conflict ended, followed a comprehensive policy of defining landlessness against clear criteria for allocation considering the spatial balance between urban and rural areas and preventing potential social tensions among society. These criteria are accompanied by a modernized real estate cadaster, providing offers of acquisition for long-term leases and a cooperative agreement between claimants, community, and state [

74]. Admittedly, the regeneration of real estate can be violently confronted by illegitimate power. Thus, it is necessary to apply this policy in accordance with international parameters to ensure that rights holders regain their rights to facilitate socio-spatial justice among urban and rural areas.

4.3.4. Real Estate Innovations in Post-Conflict Ethiopia: Decentralization of Real Estate Tenure System

The effective practice of decentralization in many countries facilitated the development of spatial-equivalent infrastructure, through the fair allocation of resources with the aim of lower spatial inter-regional disparity [

91]. The decentralized administration in Ethiopia has gradually improved in the real estate sector, based on the development model that mainly depends on efficiency and productivity, in the context of promoting the efficiency of real estate and local administrative land structures [

92]. This is because the decentralization of land functions was anticipated to solve real estate insecurity through a local solution. This was attributed to the fact that the land tenure would be more secured by promoting the productivity, effectiveness, and accountability of the real estate system in addition to providing more operational real estate practices. Moreover, this decentralization helps to raise the image of the government among the local community and guides people to naturally increase their knowledge about legislation and their rights [

93].

The regional government in Ethiopia is responsible for legislation toward flexible executive procedures along with single decentralization programs, which are conducted by local authorities that are concerned with improving real estate local norms, observing unused land, allocating them fairly, solving land disputes, and improving the quality of the cadaster [

90,

92]. This implies fostering the local community in a way that ensures a sustainable relation between citizens and real estate authorities, as well as promoting the equitable sharing of government expenditures on social and economic development. This will reflect a spatial balance between all parts of the city and between rural and urban areas in a determined geographic region. Hence, the decentralization of the real estate tenure system plays a vital role in reducing the possibility of spatial conflicts and spatial disparity in regional development [

96].

A decentralized clustering structure has proven to be effective for better control of cities’ functions by controlling the population density. This can be achieved by enforcing the concept of suburban and outer-suburban satellite cities to establish new settlements that meet the sustainable relocation program’s needs, particularly in the post-disaster phase [

94]. In this manner, a balanced distribution of services can be achieved among disaster-torn regions. This highlights the vital importance of decentralization in terms of providing equitable opportunities to ultimately ensure comprehensive spatial development.

4.3.5. Innovations Addressing the Spatial Impacts of COVID-19 on the Real Estate

Urban innovations are being followed across the world to deal with epidemic diseases by fostering coverage of urban social protection [

60] and providing a human-centered strategy to promote a healthier environment in urban areas to cope with the current crisis and to be more immune to epidemic diseases in the future [

56]. One such strategy is 15-min city, which seeks to conduct urban renewal on a temporal basis by encouraging slow mobility among services that can be reached within 15 min, thereby resetting land use and urban functions that will dramatically change the way real estate conducted [

61,

95]. Furthermore, moving to a decentralized world where everybody lives in equitable low-density environment [

58], in which cities can breathe by decentralization of congested urban functions, and start to strengthen communities far from the city center [

64]. A modern urban structure featuring a fast and smart link between cities facilitated by improving transport networks, accessibility, and technology [

65].

The local governments in the United States of America have not resisted real estate changes triggered by COVID-19. However, strategic adaptability has been evolved on the basis of more livable metropolitan areas with fewer users and less crowded centers, thereby facilitating the transition and expanding public transportation networks with slower frequencies. In addition, the federal governments mitigate the bad impact of COVID-19 on local governments by supporting municipalities through recovery procedures, such as the Fed’s municipal lending facilities. Nevertheless, these procedures are still short-term. Hence, the city centers have to think sustainably by balancing their budgets and decreasing spending [

66].

5. Conclusions

This research was conducted to sketch out a comparative framework for discussing the real estate challenges and innovations in the context of observing the spatial dimension of disaster-affected countries. This helps to understand the mutual effects of real estate during times of disaster on legislation, administration, social justice, security, and shocking global pandemic. Spatial imbalance can prevail owing to lawlessness and double legal parameters that lead to overly poor property enforcement, which reinforces the crack between the strata of society. This necessitates fostering fair real estate adjudication and promoting fit-for-purpose strategies to restore owners’ rights and achieve a balanced society. There is sufficient evidence to support the claim that equitable real estate legislation bringing about the enhancement of social inclusion and strengthening the affiliation concept between people and their surroundings, thereby fostering the security of property rights, and this confirms the validity of the first hypothesis.

Furthermore, the multiplicity of real estate administration and tenure systems has been a critical component of disputes that erupt over estates due to conflicting interests and rights. To address this, we need a renewed approach that keeps pace with maintaining spatial balance during the emergency. Successful real estate administration requires equitable access to property to obtain socio-spatial justice; otherwise, social disparity will aggravate the insecurity problem, which forced people to migrate to more secure places, causing an exacerbation of spatial imbalance. The second hypothesis is validated to some extent; however, demographic change stemming from forced displacement is a critical factor in property imbalance. This related to the enforced disappearance of original property forming a serious obstacle in front of balanced access to real estate in the post-conflict phase.

Real estate security has posed a serious challenge that destroys the sense of belonging to a place due to lack of sustainability. This research, in this respect, illustrated the role of decentralization in making the process of securing real estate more effective in practice. The third hypothesis has been validated in the Ethiopian case study, which emphasizes the role of a decentralized administration system in enhancing coherence between real estate policies, executive programs, and the concerned population, thereby promoting an urban spatial balance.

Urban decentralization can also be resilient post-pandemic recovery, which enhances balance in terms of spatial matching of population and geographical equality, particularly with unprecedented COVID-19 protection measures like lockdowns and working from home, which lead to disruption in global real estate markets resulting from shocking spatial shifts in real estate demand.

The limitation of this research is that, whereas real estate innovations during disasters have been discussed from a social, administrative, and legal perspective, any innovations in econometric techniques for properties valuation and monitoring real estate distortions during and after disasters have yet to be established. Future research should investigate novel technical innovations, which analyze the urban imbalance, by using smart data visualization of the integration between real estate markets and spatial dimensions of urban areas. Additionally, it can open up areas for critical research to investigate the disadvantages of previous real estate innovations so as to develop real estate performance. Thus, it may provide new strategies to mitigate the effects of disasters and even reduce the possibility of their occurrence in order that global stability must be ensured.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A., V.G. and A.R.; methodology, M.A.; software, M.A. and A.R.; formal analysis, M.A. and A.R.; resources, M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.; writing—review and editing, A.R. and V.G.; visualization, M.A.; supervision, A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper has been supported financially by the Ruhr University Bochum and the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support by the DFG Open Access Publication Funds of the Ruhr-Universität Bochum. We would like to express our thanks for German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) for support to carry out this research work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Guggenheim, M. Introduction: Disasters as Politics—Politics as Disasters. Sociol. Rev. 2014, 62 (Suppl. 1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.E.; Bart, R.R.; Kennedy, M.C.; MacDonald, A.J.; Moritz, M.A.; Plantinga, A.J.; Tague, C.L.; Wibbenmeyer, M. The Dangers of Disaster-Driven Responses to Climate Change. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 651–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, G.; O’Keefe, P.; Rose, J.; Wisner, B. Climate Change and Disaster Management. Disasters 2006, 30, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, J.N.; Esnard, A.-M.; Sapat, A. Population Displacement and Housing Dilemmas Due to Catastrophic Disasters. J. Plan. Lit. 2007, 22, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, L.; Christy, J.; Roopesh, B.N.; Binu, V.S.; Das, S.K.; Sekar, K. Development of an Instrument on Psychosocial Adaptation for People Living in a Disaster-Prone Area. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 68, 102716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettibone, H.D. Real Estate in War Time. J. Land Public Util. Econ. 1939, 15, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidin, K.L.; Meerovich, M.G.; Bulgakova, E.A.; Zabelina, S.A. Information Flows Balance and Price of Real Estate. J. Adv. Res. L. Econ. 2017, 8, 496–504. [Google Scholar]

- Walch, C. Typhoon Haiyan: Pushing the Limits of Resilience? The Effect of Land Inequality on Resilience and Disaster Risk Reduction Policies in the Philippines. Crit. Asian Stud. 2018, 50, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, J.S. Challenges of Judicial Reform in Haiti; Lulu.com. 2009. Available online: https://www.lulu.com/shop/jean-s%C3%A9nat-fleury/shop/jean-s%C3%A9nat-fleury/the-challenges-of-judicial-reform-in-haiti/paperback/product-1952rjw6.html?page=1&pageSize=4 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Unruh, J. Land: A Foundation for Peacebuilding. 2013. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285393314_Land_A_foundation_for_peacebuilding (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Marcelin, L.H.; Cela, T. Justice and Rule of Law Failure in Haiti: A View from the Shanties. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 48, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Modern Disaster Theory: Evaluating Disaster Law as a Portfolio or Legal Rules Symposium: A Worldwide Response: An Examination of International Law Frameworks in the Aftermath of Natural Disasters. Emory Int’l L. Rev. 2011, 25, 1121–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Kumlu, K.B.Y.; Tüdeş, Ş. Theoretical Approaches in the Context of Spatial Planning Decisions and the Relation with Urban Sustainability. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 072041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining Urban Resilience: A Review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D. Developing Communities; Sutton Hastoe Housing Association: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, G. The Role of Private Sector for Reducing Disaster Risk in Large Scale Infrastructure and Real Estate Development: Case of Delhi. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 14, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, K.M.; Kovacs, P. Real Estate Market Response to Enhanced Building Codes in Moore, OK. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 27, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apergis, N. Natural Disasters and Housing Prices: Fresh Evidence from a Global Country Sample. Int. Real Estate Rev. 2020, 23, 815–836. [Google Scholar]

- Ricks, M. Money, Private Law, and Macroeconomic Disasters Law and Macroeconomics. Law Contemp. Probs. 2020, 83, 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Brotman, B.A. Bankruptcy Filings, Flooding, Real Estate Prices and Leading Index. Prop. Manag. 2021, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duqi, A.; McGowan, D.; Onali, E.; Torluccio, G. Natural Disasters and Economic Growth: The Role of Banking Market Structure. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 71, 102101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feres, H.G. Long-term urban land market trends. Concepcion, chile. 1989–2018. Archit. City Environ. 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Neighbourhood Unit; Routledge/Thoemmes Press: London, UK, 1929.

- Wright, F.L. “Broadacre City: A New Community Plan”: Architectural Record (1935). In The City Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd Lawhon, L. The Neighborhood Unit: Physical Design or Physical Determinism? J. Plan. Hist. 2009, 8, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, J.S.; Talen, E.; Talen, E.; Hopkins, L.D.; Hays, D.L.; Pallathucheril, V.G. Constructing Professional Knowledge: The Neighborhood Unit Concept in the Community Builders Handbook; University of Illinois: Urbana, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gries, J.M.; Ford, J. Planning for Residential Districts; The President’s Conference on Home Building and Home Ownership: Washington, DC, USA, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, P.H. The Socially Balanced Neighbourhood Unit. Town Plan. Rev. 1958, 29, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, M. Neighborhood Unit and Its Conceptualization in the Contemporary Urban Context. Inst. Town Plan. India J. 2011, 8, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, J. Consuming Communities: The Neighbourhood Unit and the Role of Retail Spaces on British Housing Estates, 1944–1958. Urban Hist. 2016, 43, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Twombly, R.C. Undoing the City: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Planned Communities. Am. Q. 1972, 24, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.M. The Suburbanity of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City. J. Urban Hist. 2019, 45, 1006–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S. Quantifying Spatial Characteristics of Cities. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 2005–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhong, W.; Shearmur, R.G.; Zhang, X.; Huisingh, D. An Inclusive Model for Assessing the Sustainability of Cities in Developing Countries—Trinity of Cities’ Sustainability from Spatial, Logical and Time Dimensions (TCS-SLTD). J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 109, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Setyono, J.S.; Yunus, H.S.; Giyarsih, S.R. The spatial pattern of urbanization and small cities development in central java: A case study of semarang-yogyakarta-surakarta region. Geoplanning J. Geomat. Plan. 2016, 3, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kenny, C. Disaster Risk Reduction in Developing Countries: Costs, Benefits and Institutions. Disasters 2012, 36, 559–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Masri, S.; Tipple, G. Natural Disaster, Mitigation and Sustainability: The Case of Developing Countries. Int. Plan. Stud. 2002, 7, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routledge Companion to Real Estate Development; Routledge Handbooks Online: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Farber, D.A. Introduction: The Role of Lawyers in a Disaster-Prone World Symposium: After the Tempest: How the Legal Community Recovers from Disasters-Introduction. Nova L. Rev. 2006, 31, 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Iwerks, R. This Land Is My Land: Protecting the Security of Tenure in Post-Earthquake Haiti Note. Fordham Int’l L.J. 2011, 35, 1824–1883. [Google Scholar]

- IOM. Dealing with Land Barriers to Shelter Construction in Haiti: The Experience of the IOM Haiti Legal Team; IOM: Le Grand-Saconnex, Sweden, 2012; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Todorovski, D.; Zevenbergen, J.; van der Molen, P. Conflict and Post-Conflict Land Administration—The Case of Kosovo. Surv. Rev. 2016, 48, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Todorovski, D.; Zevenbergen, J.A.; van der Molen, P. Can Land Administration in Post-Conflict Environment Facilitate the Post-Conflict State Building? In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week, Rome, Italy, 6–10 May 2012; Available online: http://www.fig.net/resources/publications/prj/showpeerreviewpaper.asp?pubid=5557 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Deininger, K.; Savastano, S.; Xia, F. Smallholders’ Land Access in Sub-Saharan Africa: A New Landscape? Food Policy 2017, 67, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leegwater. Sharing Scarcity: Land Access and Social Relations in Southeast Rwanda; African Studies Collection; African Studies Centre: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Reale, A.; Handmer, J. Land Tenure, Disasters and Vulnerability. Disasters 2011, 35, 160–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suu, N.V. The Politics of Land: Inequality in Land Access and Local Conflicts in the Red River Delta since Decollectivization. In Social Inequality in Vietnam and the Challenges to Reform; ISEAS Publishing: Singapore, 2004; pp. 270–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearns, R. Access to Land in Rural India: Policy Issues and Options; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Land Tenure|UNCCD. Available online: https://www.unccd.int/actions/land-tenure (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Kenjio, J.W.K. Decolonizing Land Tenure Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Path to Modern Land Policy Reforms. J. Land Manag. Apprais. 2020, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopp, J.M. “Ethnic Clashes” and Winning Elections: The Case of Kenya’s Electoral Despotism. Can. J. Afr. Stud. Rev. Can. Des Études Afr. 2001, 35, 473–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homewood, K.; Coast, E.; Thompson, M. In-Migrants and Exclusion in East African Rangelands: Access, Tenure and Conflict. Africa 2004, 74, 567–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.; Worger, W. Law, Colonialism and Conflicts over Property in Sub-Saharan Africa. Afr. Econ. Hist. 1997, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, P.E. Challenges in Land Tenure and Land Reform in Africa: Anthropological Contributions. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legeby, A.; Koch, D.; Duarte, F.; Heine, C.; Benson, T.; Fugiglando, U.; Ratti, C. New Urban Habits in Stockholm Following COVID-19. Urban Stud. 2022, 00420980211070677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhang, Y. Urban Epidemic Governance: An Event System Analysis of the Outbreak and Control of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Urban Stud. 2022, 00420980211064136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnat, S.M. Rural-Urban Variation in COVID-19 Experiences and Impacts among U.S. Working-Age Adults. ANNALS Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2021, 698, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carson, S.; Nanda, A.; Thanos, S.; Valtonen, E.; Xu, Y. Imagining a Post-COVID-19 World of Real Estate. Town Plan. Rev. 2020, 92, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, S.S.; Strange, W.C.; Urrego, J.A. JUE Insight: Are City Centers Losing Their Appeal? Commercial Real Estate, Urban Spatial Structure, and COVID-19. J. Urban Econ. 2022, 127, 103381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, S.; Cuesta, J. Urban-Sensitive Social Protection: How Universalized Social Protection Can Reduce Urban Vulnerabilities Post COVID-19. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2021, 21, 340–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balletto, G.; Ladu, M.; Milesi, A.; Camerin, F.; Borruso, G. Walkable City and Military Enclaves: Analysis and Decision-Making Approach to Support the Proximity Connection in Urban Regeneration. Sustainability 2022, 14, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.H.; Keil, R. Global Cities and the Spread of Infectious Disease: The Case of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in Toronto, Canada. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, M.; Yu, H.; Nie, S.; Yan, W. Chinese Urban–Rural Disparity in Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Vaccination Coverage Rate and Associated Determinants: A Cross-Sectional Telephone Survey. Public Health 2013, 127, 930–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, S.; Yeros, P. Reclaiming the Land: The Resurgence of Rural Movements in Africa, Asia and Latin America; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman, M. Policy Challenges for the Post-Pandemic City. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2020, 47, 1136–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Donut Effect: How COVID-19 Shapes Real Estate|Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR). Available online: https://siepr.stanford.edu/publications/policy-brief/donut-effect-how-covid-19-shapes-real-estate (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- IASC Strategy. Meeting Humanitarian Challenges in Urban Areas. 2010. Available online: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/iasc-reference-group-meeting-humanitarian-challenges-urban-areas/iasc-strategy-meeting-humanitarian-challenges-urban-areas-2010 (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- International Crisis Group (ICG). Keeping Haiti Safe: Justice Reform, 27 October 2011, Latin America/Caribbean Briefing N°27. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4eb24ec32.html (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Berg, L.-A. All Judicial Politics Are Local: The Political Trajectory of Judicial Reform in Haiti. U. Miami Inter-Am. L. Rev. 2013, 45, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Offia Ibem, E. Challenges of Disaster Vulnerability Reduction in Lagos Megacity Area, Nigeria. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2011, 20, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gbadegesin, J.T.; van der Heijden, H.M.H.; Boelhouwer, P.J. Land Accessibility Factors in Urban Housing Provision in Nigeria Cities. In Proceedings of the ENHR 2016: The European Network for Housing Research Conference: Governance, Territory and Housing, Belfast, UK, 28 June–1 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu, C.P.; Iruobe, P. Comparison of Formal and Informal Land Administration Systems in Lagos State: The Case of Epe Local Government Area. J. Afr. Real Estate Res. 2018, 3, 18–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prunier, G. The Rwanda Crisis: History of a Genocide; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; p. 389. [Google Scholar]

- Musahara, H.; Huggins, C. Land Reform, Land Scarcity and Post-Conflict Reconstruction: A Case Study of Rwanda. Ground Up: Land Rights Confl. Peace Sub-Sahar. Afr. 2005, 314, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreaux, K. Land Conflict and Genocide in Rwanda. Electron. J. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 1, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, N.M. Leaving No-One behind? Social Inequalities and Contrasting Development Impacts in Rural Rwanda. Dev. Stud. Res. 2018, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orrnert, A. Evidence on Inequalities in Rwanda. 2018. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5c70243740f0b603d7852857/356_Inequalities_in_Rwanda.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Kebede, B. Land Tenure and Common Pool Resources in Rural Ethiopia: A Study Based on Fifteen Sites. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2002, 14, 113–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land Tenure in Ethiopia: Continuity and Change, Shifting Rulers, and the Quest for State Control; Crewett, W.; Bogale, A.; Korf, B. (Eds.) CAPRi Working Paper; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, D.A.; Dercon, S.; Gautam, M. Property Rights in a Very Poor Country: Tenure Insecurity and Investment in Ethiopia. Agric. Econ. 2011, 42, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woldemicael, G. The Demographic Transition and Development in Africa: The Unique Case of Ethiopia. Can. Stud. Popul. 2013, 40, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Milcheva, S. Volatility and the Cross-Section of Real Estate Equity Returns during COVID-19. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansoms, A.; McKay, A. A Quantitative Analysis of Poverty and Livelihood Profiles: The Case of Rural Rwanda. Food Policy 2010, 35, 584–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagno, L.; Gandia, E.; Bonnefoy, V. Overcoming Land Tenure Barriers in Shelter and Other Reconstruction Activities in Post-Disaster Settings. In Identifying Emerging Issues in Disaster Risk Reduction, Migration, Climate Change and Sustainable Development: Shaping Debates and Policies; Sudmeier-Rieux, K., Fernández, M., Penna, I.M., Jaboyedoff, M., Gaillard, J.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassu, G. Law Overruled: Strengthening the Rule of Law in Postconflict States. Glob. Gov. 2008, 14, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thontteh, E.O.; Omirin, M.M. Land Administration Reform in Lagos State. Pac. Rim Prop. Res. J. 2015, 21, 161–177. [Google Scholar]

- Shittu, A.I.; Adeosun, O.T. Innovations in Government and Public Administration of Land in Lagos State. Afr. J. Land Policy Geospat. Sci. 2020, 3, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitikainen, A. An Overview of Land Consolidation in Europe. Nord. J. Surv. Real Estate Res. 2004, 1, 25–44. Available online: https://journal.fi/njs/article/view/41504 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Pottier, J. Land Reform as Conflict Prevention: The Case of Rwanda. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Wars and Violent Conflicts, Lisbon, Portugal, 15–16 December 2005; ISCTE: Lisbon, Portugal, 2016. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10071/11692 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Bruce, J.W.; Knox, A. Structures and Stratagems: Making Decentralization of Authority over Land in Africa Cost-Effective. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1360–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalirajan, K.; Otsuka, K. Decentralization in India: Outcomes and Opportunities; ASARC Working Papers; Australian National University, Australia South Asia Research Centre: Canberra, Australia, 2010; Volume 14, Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/pas/asarcc/2010-14.html (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Chinigò, D. Decentralization and Agrarian Transformation in Ethiopia: Extending the Power of the Federal State. Crit. Afr. Stud. 2014, 6, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, M. Localizing Land Governance, Strengthening the State: Decentralization and Land Tenure Security in Uganda. J. Agrar. Change 2017, 17, 208–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, Y.; Meng, X. From Concentration to Decentralization: The Spatial Development of Beijing and the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Capital Region. In Chinese Urban Planning and Construction: From Historical Wisdom to Modern Miracles; Bian, L., Tang, Y., Shen, Z., Eds.; Strategies for Sustainability; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozoukidou, G.; Chatziyiannaki, Z. 15-Minute City: Decomposing the New Urban Planning Eutopia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalirajan, K.; Otsuka, K. Fiscal Decentralization and Development Outcomes in India: An Exploratory Analysis. World Dev. 2012, 40, 1511–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).