1. Introduction

For years, spatial planning has been a key mechanism used by public authorities to influence reality [

1], which is quite understandable given the fact that the subject and objectives of spatial planning are very extensive and complicated [

2]. Planning refers to the entirety of public management along with its economic, social, and environmental effects as well as conflicts arising during the functioning and transformations of space. In the literature on the subject, there is a consensus that a significant goal of spatial planning is to coordinate development policies pertaining to various sectors of social and economic life [

3,

4]. What is more, Albrechts et al. [

5] indicate that spatial planning is also a platform where public and private actors interact. This is because, as Martínez [

6] and Ganis [

7] observe, spatial planning, due to the broad scope of its regulations, is an instrument, or at least a condition, for many entities to achieve their objectives (especially economic ones).

A considerable number of publications on the spatial planning systems of European countries (including EU member states) have already been produced. There are a growing number of detailed analyses of spatial planning systems in individual countries [

8]. Some of works are also of an overview nature, comparing the planning systems of different countries [

8,

9,

10]. The classic works that include comparative analysis are focused on “planning families” or “planning traditions” [

9].

Most of the mentioned works examine various countries. As a rule, publications do not take into account both countries of interest to the authors of this paper (i.e., Poland and Portugal), or they include only one of them. Even if both countries are included, they are not widely discussed, and the issue of enforcing actors is rather rarely discussed. Comparative analyses usually concern Poland and Germany, e.g., [

11,

12], or Portugal and Brazil, e.g., [

13,

14,

15]. Furthermore, the publications so far contain quite comprehensive analyses of planning systems, and the issue of clashing interests of various entities is usually discussed only marginally. Therefore, there are some opinions, e.g., [

16] that the existing research on planning systems in the European Union needs to be deepened and detailed. The authors of this paper wish to fill this gap, at least to some extent.

Undoubtedly, there are various factors that influence spatial planning systems, such as historical conditions, socioeconomic and cultural contexts, and what is more, political ones. These patterns have brought about particular forms of government. Furthermore, planning systems are often influenced by international agreements (e.g., European integration). The possibility for planners to cooperate beyond the regional or national borders enables particular countries to learn from various other practices. It may end up with, to some extent, harmonisation or convergence [

17]. A significant document at the European level is adopted in the 1999 European Spatial Development Perspective (ESDP) [

18]. It aims at coherent and complementary spatial development strategies in the European Union member states. However, ESDP is not a binding document. It indicates common directions of action of the member states in the context of spatial policies [

19].

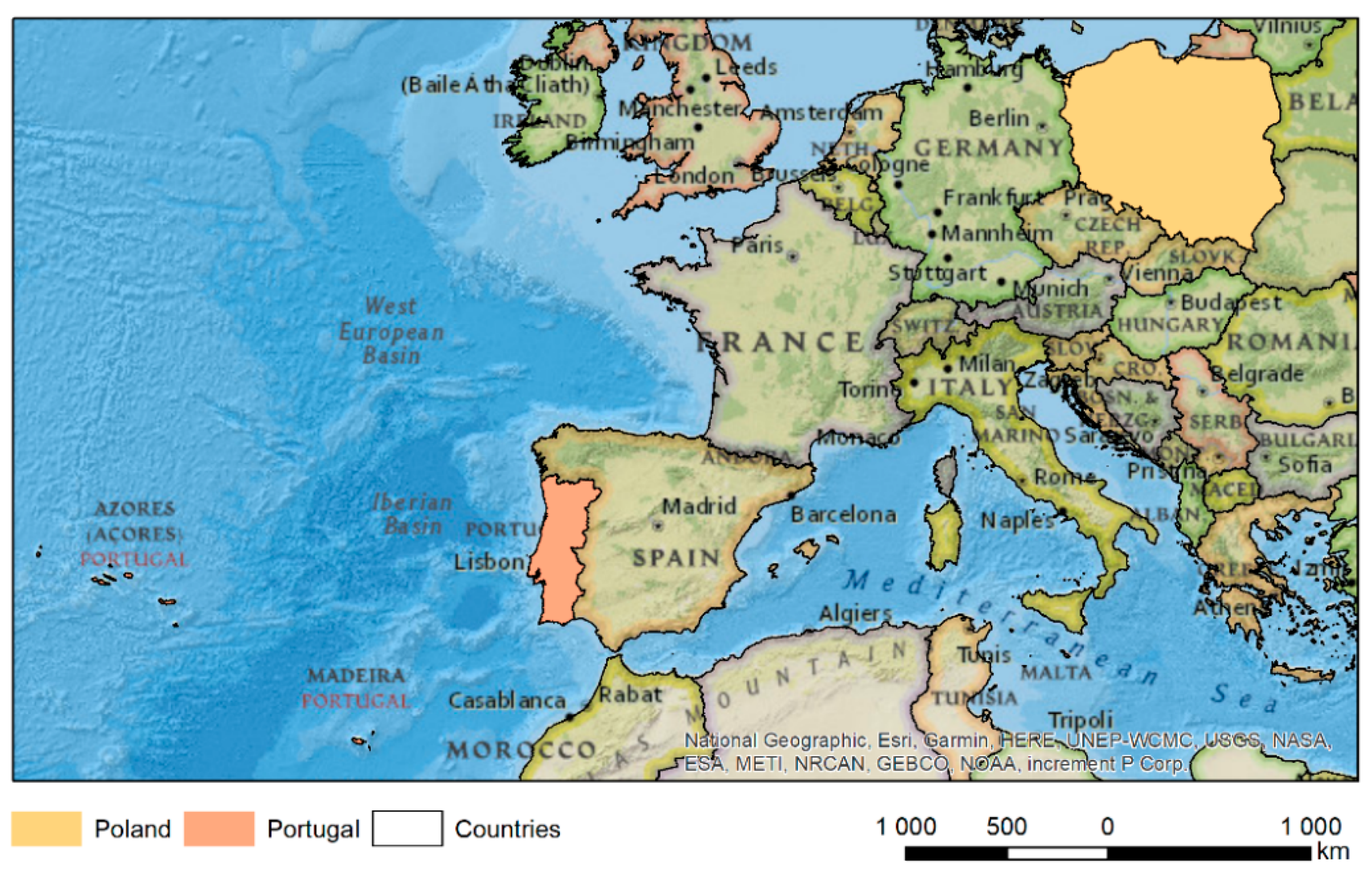

The objective of this study is to compare the relationship between the mechanisms of representing the public and private interest in the spatial planning systems of Poland and Portugal, indicating the similarities and differences between procedures. Two democratic European Union countries with similar levels of socioeconomic development have been selected for comparison. The article is based on the hypothesis that even political, sociocultural, and economic similarities do not necessarily lead to the creation of similar mechanisms of weighing the public and private interest in spatial planning processes.

The question is raised regarding how public interest consideration can be enforced in the spatial planning systems of Poland and Portugal. Do similar determinants create similar mechanisms of weighing the public and private interest in spatial planning processes? Are the spatial planning systems of Poland and Portugal considerably different after all, and can valuable conclusions for both countries be drawn from these differences? A better understanding of these two systems may be useful in the context of learning from good experiences and creating a better space.

The Theoretical Framework

In the literature, there are various divisions of groups of spatial planning systems, according to the classic work of Newman and Thornley [

8]. They divide the systems into five families: British, Scandinavian, Napoleonic, Germanic, and East European. Portugal is an example of the Napoleonic family, the biggest distinguished group, while Poland the East European one. The Napoleonic family is characterised by the primacy of the rule of law. The local government has relatively strong control through central entities. In countries such as Portugal, where dictatorship has spanned many years, centralisation was even stronger. The poorer economic prosperity of the country suggests that most likely the centralised approach was used. Due to changes after the fall of the dictatorship, for instance, the fused system has been visible. The East European family was at the beginning of its creation after 1989 (the work is dated 1996). However, the common past understood as communist time, with a high level of centralisation, seemed to be quite a significant reason of some similarities within this family.

In the 1990s, the European Commission in “the EU compendium of spatial planning systems and policies” [

20] distinguished four main traditions of spatial planning: regional economic planning approach, comprehensive integrated approach, land use management, and urbanism tradition. Portugal is therefore an example, although to a lesser extent, of the first group. The regional economic planning approach is related to quite a broad understanding of spatial planning, with a significant role of socioeconomic aims. In terms of planning, there is rather a top–down approach, and public investments are highly ranged. Poland was not included in this work (it was not a member of the European Union at that time).

ESPON 2.3.2. Governance of Territorial and Urban Policies from EU to Local Level is based on a typology from the compendium, but some changes are visible. Portugal is still placed under regional economic planning and also under land use planning, where planning is related to intervention in the use of land in the local and strategic contexts. What is important for this paper is that this work also includes Poland. The authors qualified Poland as an example of the comprehensive integrated approach. This group is characterised by its hierarchical spatial planning, from the national to the local level [

20,

21].

Reimer, Getimis, and Blotevogel in 2014 [

9] analysed the transformation that has occurred since 1990. Based on “planning traditions”, they took into consideration at least two countries from four groups (regional–economic, urbanism, comprehensive/integrated, and “land use planning”), selecting Poland and Turkey as the examples of developments in East Central and Southeast Europe. In total, 12 countries were examined with the final, comparative conclusions. Although the work takes into account Poland, Portugal is not included.

As living standards rise in most European countries, while the diversity and pace of transformation of their economies increase, the importance of spatial planning is growing [

22]. Therefore, it is evident that the literature on the nature of spatial planning and the scope of its provisions is vast and varied. Different authors define the object and purpose of spatial planning in different ways. Some understand it as both defining a picture of future reality and ways of achieving it [

23,

24]. Others, on the other hand, use the term exclusively or primarily to describe the future shape of reality [

25,

26]. Cullingworth and Nadin [

27] point to an obvious reason for this diversity of views, namely, different legal regulations on spatial planning existing in different countries.

The shape of legal regulations is also crucial for the future shape of space, which is a resultant of the interests of various entities. Due to the limited nature of space and divergence of objectives formulated by the different players in the “game for space”, only some of them have the possibility to achieve their goals. At the same time, the achievement of the objectives of specific entities does not necessarily depend on, for example, the compatibility of these objectives with urban planning principles. Various political pressures are among the factors influencing the decisions of spatial planners [

28]. Grange [

29] points out that spatial planners always work under political pressure both as subordinates to entities of a more or less political nature and because their actions are based on regulations created by legislative bodies. As a result, each planning system emphasises certain values (inherently close to some participants in the “competition for space”) at the expense of others [

30]. This has to mean that different spatial planning systems always inevitably favour or disadvantage the interests of different parties [

31]. At the same time, there is a fairly common opinion that the values preferred in the spatial planning system are the same values preferred by the prevailing political and economic system in a given country [

32]. This is an inevitable result of the role of planning as one of the elements of the political and administrative system [

33].

The natural pressure from economically motivated private entities raises the question of the role of spatial planning in formulating and defending the public interest. After all, numerous public tasks have a spatial expression [

34], and spatial planning naturally links, harmonises, and sometimes even enables the implementation of various public policies [

35,

36]. The nature of spatial planning means that public institutions must be the actors in this sphere of planning. It may thus seem that the public interest will always have an appropriately high status in spatial planning arrangements.

Nevertheless, views on this issue vary. Documents produced by public bodies, such as the institutions of the European Union and the Council of Europe, e.g., [

37,

38,

39], generally emphasise the role of spatial planning as a tool for the integrated shaping and protection of certain public values—nature, cultural heritage, or landscape. UNECE even indicates that spatial planning is the natural and only tool that can ensure balance between private and public interests [

25]. However, E. R. Alexander [

40] points out that, on the one hand, the public interest is indeed the raison d’être of spatial planning. On the other hand, this planning is a platform for the clash of interests of numerous and diverse actors. The multiplicity of these actors means that the full realisation of the public interest is not possible. Furthermore, as P. Allmendinger and G. Haughton [

41] note, in the recent years, some authors have understood not the public interest but economic efficiency as the main objective to be served by spatial planning. M. Papageorgiou [

42] points out that, for instance, the evolution of the Greek spatial planning system, implemented in the second decade of the 21st century, goes in precisely, such a “neoliberal” direction.

Many authors point out that the actual place of the public interest in spatial planning is influenced by the planning culture existing in a given country. M. Neuman [

43], indicating the ongoing discussions on the subject, argues that the planning culture should be considered as a common way of thinking about the principles of spaceshaping. This way results not only from the professional view of planners but also from the value system adopted in a given society. Similarly, D. Fürst [

44] argues that the planning culture consists of mental predispositions shared by all people involved in the planning process. M. Reimer and H. H. Blotevogel [

33] pragmatically conclude that the planning culture manifests itself in the real behaviours and decisions of planners operating within a particular spatial planning system.

Therefore, the authors of the paper believe that the legal structure of a spatial planning system in a particular country plays a decisive role. The essential elements of this structure that determine the possibility of enforcing the public interest in space are primarily:

The content (provisions) of documents drawn up by various public entities and the rank of public values in these provisions;

Relationships between the content of specific documents, manifested particularly in the possibility for various public entities to influence the content of the particular documents;

The impact, through public participation mechanisms, of private individuals, particularly property owners, on the content of planning documents that are the basis for issuing building permits.

3. Results

The systemic shape of spatial planning depends predominantly on the administration structure of a state. The decentralisation of public authority has been evident in Poland following the administrative reform initiated in 1990. There is a three-tier administrative division, with an important role played by local governments [

71]. At present (as of 1 January 2021), the territory of Poland is divided into 16 voivodeships (Polish województwa), which in turn are divided into 314 counties (Polish powiaty), each comprising up to a dozen or so municipalities (Polish gminy). Alongside the structure of counties, there are several dozen (66) largest cities, commonly referred to as “urban counties” (powiatygrodzkie) that combine the county and municipality statuses. Municipalities (2477 nationwide) are a fundamental tier of the administrative division. Each municipality encompasses an area of about a dozen or more villages, a single city, or a small town with the adjacent rural areas [

72]. A special entity within Poland’s system of administrative division is the metropolitan association, which only in the Silesian Voivodeship currently exists, and encompasses over 40 municipalities (most of them are cities) [

73,

74].

The municipality, satisfying most of the collective needs of the local community, is the key structure within Poland’s system of local government [

60,

71]. These needs include local roads, communal infrastructure, and primary schools [

75] (Article 7). The county, also having a local government status, and managing certain roads, among other tasks [

76] (Article 4), is predominantly responsible for strictly administrative matters, handled on behalf of the government administration. The metropolitan association focuses on tasks related to public road and rail transport [

73] (Article 12). The provincial self-government pursues (in principle) a regional development policy, carries out tasks in the field of spatial planning, and manages, among other things, major roads and rail transport of regional importance [

77] (Articles 11 and 14). At the same territorial level as the voivodeship government, there is a separate governmental administration [

78] that performs mainly supervisory functions.

Although the administrative structure of Portugal is still in the process of transformation, it is divided into three tiers similar to Poland. In 1996, pursuant to the Constitution of the Portuguese Republic, local government was established, which, eventually, consisted of three levels of local government in the mainland: administrative regions (Portuguese regiõesadministrativas), municipalities (Portuguese municípios), and civil parishes (Portuguese freguesias) (The autonomous regions of the Azores and Madeira consist of municipalities and parishes. The autonomy of these regions, in lieu of administrative regions, is guaranteed by the constitution [

79]). Despite numerous attempts, administrative regions have not been implemented until today, and their creation is merely a “constitutional objective” [

46,

79,

80,

81]. Until they are established, the division into municipalities is formally binding according to the constitution [

61]. Significant change occurred in 2013 when the division of 18 districts was, in a way, replaced by a division of intermunicipal communities (Portuguese comunidadesintermunicipais—CIM) and metropolitan areas (Portuguese áreasmetropolitanas—AM) [

81,

82,

83]. Two AMs of administrative nature exist around the two largest cities (Lisbon and Porto), and CIMs of a similar character exist in the remaining areas. Furthermore, central public administration (i.e., regional directorates of various ministries) exist at the regional level. A total of 308 municipalities (including 278 in the mainland) function at the local level. The municipalities are divided into small civil parishes, which are quite numerous (3092, including 2882 in the mainland) [

81,

83,

84].

Similar to Poland, the municipality is the key element of Portugal’s administrative structure. It performs the most important public tasks and responds to the needs of the population (e.g., transport and communications, education, basic sanitary conditions) [

82] (Article 23). Some of these tasks are performed (formally on behalf of the municipality) by the civil parish. Metropolitan areas and intermunicipal communities are responsible mainly for coordinating tasks (especially investment projects) of a supramunicipal character. The significance of NUTS 2 units should also be noted. Regional planning is conducted at this level in Portugal. These units are administered by the Commissions for Coordination and Regional Development (Portuguese Comissão de Coordenação e Desenvolvimento Regional, hereinafter CCDR), which constitute decentralised governmental administration [

46,

81,

85].

Spatial planning in Poland is currently (as of July 2021) based on the 23 March 2003 Act on Spatial Planning and Development [

86], which has been amended several times since it was adopted. For many years, the above act granted spatial planning powers to three levels of government: central government, voivodeship government, and municipal government. From the very introduction of the current system, the county has had an auxiliary role.

The Polish Act on Spatial Planning and Development stipulates several goals that should be considered in the process of planning and subsequent development of space. Although these goals include ownership and the economic value of space, emphasis is put on values of public nature, such as spatial order, landscape values, requirements of environmental protection, and cultural heritage preservation as well as generally defined requirements of the public interest [

87].

Spatial planning in Portugal is currently based on two pieces of legislation: the 30 May 2014 Law on the general principles of spatial development and urban planning [

88] (hereinafter LBGPPSOTU) and the new regime of planning instruments (i.e., the Presidential Decree of 14 May 2015 [

89], hereinafter NRJIGT). The Portuguese spatial planning system is much more complex than the system functioning in Poland. Although Portugal has a much smaller territory than Poland, Portuguese law grants spatial planning powers to four levels of public administration, namely, central, regional (CCDR), intermunicipal (including metropolitan), and municipal administration [

14,

88,

89]. Civil parishes, undoubtedly owing to their small territory and weak powers, are excluded from this system.

Spatial planning documents in Portugal are divided into programmes and plans [

88] (Article 38), among which only plans are binding to private entities, while programmes are binding to public administration only [

90]. The public interest has a very high rank among the values that spatial planning is to serve. Section II of Chapter I of NRJIGT [

89] is entirely devoted to values of a public character, and these values include sustainable development, intra- and intergenerational solidarity, quality of life and public security, and national defence requirements. Environmental protection issues are also important.

3.1. Planning at the National Level

Spatial planning at the national level in Poland is currently undergoing transformation. In July 2020 [

91], the national level was removed from the planning system almost completely. In the new system, the medium-term national development strategy (Polish abbreviation: ŚSRK) is to be the basis for the central government to influence spatial planning. It is to be “a document specifying the basic conditions, goals and directions of the country’s development in the social, economic and spatial dimension over a period of 10–15 years as well as detailed actions over a four-year period” [

92] (Article 9). The document has not been completed yet; hence, it is difficult to assess its effectiveness. Until recently, for 17 years, the fundamental document was the National Spatial Development Concept (Polish koncepcja przestrzennego zagospodarowania kraju (KPZK)), which was primarily concerned with the national settlement system along with its basic elements, issues related to environmental protection and historic monument preservation; distribution of social, technical, and transport infrastructure of international and national importance; and problem areas of national importance.

In general, the preparation of KPZK by the government did not require discussing or consulting the draft of this document by other public entities. The law did not provide for the participation of the public whether in the form of opinions formulated by individuals or positions expressed by public organisations, economic entities, and so forth. The only advisory body for the drafting of the concept was the State Council for Spatial Planning, appointed (optionally) by the prime minister [

93] (Article 47). Currently, when drawing up the ŚSRK, the legislator takes into account the question of consulting local government units (and their associations), the Joint Commission of Government and Local Government, and civic and business partners [

92] (Article 6).

The resolutions of the KPZK had to be taken into account (until the above-mentioned amendment of the Act in 2020) in the voivodeship spatial development plans (Polish abbreviation: PZPW) prepared by the voivodeship self-governments [

94] (Article 39). At present, the PZPW will take into account the provisions of the ŚSRK [

86] (Article 39).

Spatial planning at the national level in Portugal is more complex than in Poland. The National Spatial Planning Policy Programme (Portuguese Programanacional da política de ordenamento do território (PNPOT)), amended in 2019, is central in this respect [

95]. This programme is to lay down the rules of the spatial distribution of the resolutions of governmental strategies for socioeconomic development, primarily the distribution of the planned public investment projects of national significance. The document thus contains the spatial instructions referring to many aspects of public authority. Among other aspects, it regulates the principles of urban policy, direction of rural area development, distribution of technical infrastructure, and other public facilities of national significance as well as areas significant from the perspective of environmental protection or preservation of cultural heritage resources [

89] (Article 32). The programme comprises spatial development scenarios (along with a graphic model of the arrangement of space) and action programmes encompassing, among others, investment projects, methods of financing the proposed actions, and their timetable. The programme may also lay down a development framework for other instruments of territorial management [

89] (Article 33).

PNPOT is drawn up by the Council of Ministers with the participation of the especially appointed Consultation Commission (Portuguese comissãoconsultiva), whose members include local government representatives. The commission may submit comments and objections to the draft programme. An opinion of the draft programme is also issued by the National Territory Commission (Portuguese Comissão Nacional do Território), a body subordinated to the minister responsible for spatial planning. What is more, the draft PNPOT is a subject of public discussion for at least 30 days. However, the final version of the programme is approved by the government and then adopted as legislation [

89] (Article 34–38).

At the national level, NRJIGT also indicates sectoral programmes (Portuguese programassectoriais) [

89] (Article 2), whose implementation can have effects of a spatial character. Sectoral programmes primarily concern public tasks within the remit of the government (e.g., environmental protection, water resources, forests, transport, and communications) [

88] (Article 40). These programmes are prepared by the relevant ministers and approved by the government. During their preparation, the government obtains the opinion of the appropriate CCDR, CIM, or municipalities, and then initiates a period of public discussion (not shorter than 20 days) [

89] (Articles 46, 48, 50, and 51).

Special programmes (Portuguese programasespeciais) are another type of documents at the national level. They are fundamentally concerned with the protection of the public interest in areas of special spatial value. They are drawn up for the sea coast, protected areas, public waters, and estuaries, and they contain mainly prohibitions and restrictions on territorial management [

88] (Article 40). Special programmes are prepared by government administration but with relatively significant participation of other actors, namely, a specially appointed consultation committee, consisting primarily of representatives of organisations and institutions involved in areas covered by the programme. The National Territory Commission has the power to resolve any disagreements between the government administration drawing up the programme and the participants in the process of its preparation. When the work on preparing the programme is completed, a public discussion also takes place. Similar to sectoral programmes, special programmes are approved by the council of ministers [

89] (Article 49–50).

3.2. Planning at the Regional Level

Spatial planning at the regional level in Poland is represented almost exclusively by planning by the voivodeship government. Its executive body (i.e., the marshal of the voivodeship) prepares a draft, and the voivodeship assembly approves the spatial development plan for the voivodeship (Polish plan zagospodarowania przestrzennegowojewództwa (PZPW)) [

86] (Article 41–42). This plan defines the basic elements of the voivodeship’s spatial structure, including the basic elements of the settlement system in a given voivodeship together with the transport and infrastructure links, protected areas (including the natural and cultural aspects), and the location of major public investment projects of supralocal importance. A PZPW may include a development plan for a functional area of a city, which is the seat the voivodeship’s central government or local government [

86] (Article 39).

A PZPW must take into account the general national interest. Previously, this was achieved by considering the provisions of the national spatial development concept (currently the provisions of the medium-term national development strategy (ŚSRK)) as well as government investment project programmes [

86,

94] (Article 39). Furthermore, every interested entity may submit an appropriate proposal to the draft plan, although it is the marshal of voivodeship who determines how to proceed with such a proposal. County and municipal governments and special central government administration bodies located within a specific voivodeship or neighbouring area also have the right to express their opinion on the prepared draft plan. The draft spatial development plan for a voivodeship is also evaluated by the voivodeship’s urban planning and architectural commission made up of professionals. However, the opinions of the commission are of a purely advisory nature [

86] (Article 41).

At the voivodeship level, a landscape audit (Polish audyt krajobrazowy) is also carried out to identify and assess the value of landscapes occurring in a given voivodeship as well as to provide recommendations concerning the protection of landscapes. The procedure of conducting an audit is slightly different. The draft audit is reviewed and agreed upon by specialised government institutions and municipal governments, and is presented for public inspection. The voivodeship government decides whether to consider the opinions, and the audit is adopted by the voivodeship assembly [

86] (Article 38–38b).

Spatial planning at the regional level in Portugal is currently represented by regional programmes (Portuguese programasregionais), prepared for NUTS 2 areas (within the remit of a CCDR). A CCDR may propose that the programme is prepared at the CIM level [

89,

96] (Article 52). Pursuant to Article 79 of LBGPPSOTU, Regional Spatial Development Plans (Portuguese Plano Regional de Ordenamento do Território (PROT)), prepared and approved based on Decreto-Lei No. 380/99, remain in force until they are amended or revised [

88]. PROT defined the organisation model of a territory. They took into account arrangements concerning the structure of the urban system and infrastructure of regional importance, environmental protection, and cultural heritage preservation issues, among other issues. They also indicated objectives concerning the location of the main public investment projects and arrangements appearing, for example, in a PNPOT [

97] (Article 53), thus adapting national guidelines to the characteristics of the region [

14]. At present, regional programmes contain similar arrangements as a PROT. They indicate the scope of operation (at the regional level) specified in a PNPOT and previously existing plans and programmes, among other documents [

89] (Article 54).

The preparation of a regional programme is within the remit of a CCDR under the supervision of state authorities responsible for spatial planning. The process of preparing a draft programme is supervised by a consultation committee made up of representatives of relevant government administrations. The commission is of a consultative nature, and any disagreements between its members (entities) and the CCDR are resolved by the National Territory Commission. Regional programmes are approved by way of resolution of the Council of Ministers [

89] (Article 56–60).

3.3. Planning at the Intermunicipal Level

County government in Poland has no autonomous powers in this field and, therefore, is not an active player in spatial planning. A county may only prepare nonbinding “analyses and studies concerning spatial development” and may be consulted and asked for opinions about planning documents prepared by the voivodeship and municipal government. At the initiative of the municipalities concerned, it may establish a county urban planning and architectural commission serving as an advisory body in municipalities that do not have their own commissions of this kind [

86,

98]. The status of a metropolitan association in the sphere of spatial planning, despite the statutory declaration about its role in spatial policy [

86] (Article 3), is similar to the status of counties. Pursuant to the most recent amendment of the 2020 Act on Spatial Planning and Development, already mentioned above, a metropolitan association no longer has to prepare a framework study on the conditions and directions for spatial development of the metropolitan association (Polish ramowestudiumuwarunkowańikierunkówzagospodarowaniaprzestrzennegozwiązkumetropolitalnego) [

86,

94,

99]. At present, a metropolitan association may prepare a metropolitan development strategy (Polish strategia rozwoju metropolitalnego) that establishes the model of the functional and spatial structure, among other things [

56,

58]. Despite more than 30 years of municipal self-government, the numerous intermunicipal associations and communities rarely engage in joint actions with respect to spatial planning. This is largely a result of the lack of legislative regulations in this respect.

In Portugal, one can clearly observe a stronger standing of entities situated between the regional and municipal levels, which is also reflected in the sphere of spatial planning. Metropolitan associations and intermunicipal alliances have various instruments at their disposal to influence spatial development. An intermunicipal programme (Portuguese programa intermunicipal (PI)) is a strategic document at the intermunicipal level. It can be prepared for an entire intermunicipal entity or for at least two neighbouring municipalities within such an entity [

88,

89] (NRJIGT, Article 61; LBGPPSOTU, Article 42). An intermunicipal programme must be consistent with the regional programme [

88] (Article 44); the subject matter of both programmes is similar. It identifies the key elements of a spatial structure, such as the layout of roads and technical infrastructure systems, and standards of protection of valuable spatial values. The programme also contains guidelines for intermunicipal and municipal spatial development plans. It also contains a timetable for the implementation of the planned public investment projects, along with an estimate of their costs and an indication of the sources of financing [

89] (Article 63–64).

An intermunicipal programme is drawn up by the executive body of a CIM or AM. A consultation committee works during the preparation of its draft, and a public debate on the draft is conducted. The programme is approved by representative bodies—an intermunicipal assembly (Portuguese assembleia intermunicipal) or a metropolitan council (Portuguese conselhometropolitano) [

89] (Article 65–68).

At the intermunicipal level, there are three optional studies of a regulatory character:

These documents primarily describe the system of land use. A special competence of intermunicipal plans (on a par with municipal plans) is the division of land into “rural areas” (i.e., those associated with agriculture, livestock breeding, and forestry as well as the protection of valuable natural and cultural areas) and “urban areas” (i.e., totally or partially urbanised or built-up areas). “Rural” land may be converted into “urban” only by way of exception, and the new “urban area” status is valid only for a period specified in the detailed plan, after which a land not used for urbanisation purposes returns to its “rural” status [

88,

89] (LBGPPSOTU Article 10; NRJIGT Article 71–72).

A PDI, having a central role at the intermunicipal level, provides the framework for the application of the other intermunicipal and municipal plans. What is more, municipalities covered by this plan are exempt from the obligation to prepare similar municipal plans [

88,

89] (LBGPPSOTU Article 42; NRJIGT Article 27). At the same time, the plan must be essentially consistent with the governmental spatial plans in particular. It presents an intermunicipal territorial model and the location of local public buildings, among other things [

88,

89] (LBGPPSOTU Article 44; NRJIGT Article 112–113). A draft intermunicipal plan is prepared by a commission established for this purpose by the councils of the municipalities involved or—if the plan encompasses the entire intermunicipal unit—by a metropolitan executive committee in the case of an AM (Portuguese comissãoexecutivametropolitana) and an intermunicipal council in a CIM (Portuguese conselho intermunicipal). The plans are adopted by councils of the municipalities concerned or a metropolitan council/intermunicipal assembly if the plan covers all the municipalities of an intermunicipal unit. The principles related to a PUI and PPI are similar to the analogous plans at the municipal level, after some necessary adaptation [

89] (Article 111–114).

3.4. Planning at the Local Level

Both the Polish and Portuguese spatial planning systems award the key powers concerning the development of space to the lowest tier of local government. Plans drawn up by local authorities are most frequently the direct basis for the implementation of new spatial development. In Poland, the main responsibility in this respect rests with the municipality. The municipal government prepares two types of documents, each with a distinct status and legal consequences, namely, a spatial development conditions and directions study of a municipality (Polish studium uwarunkowań i kierunków zagospodarowania przestrzennego gminy (studium)) and a local spatial development plan (Polish miejscowy plan zagospodarowania przestrzennego—(mpzp)).

The former document, encompassing—by law—the entire territory of a given municipality, is prepared to formulate the basic directions of local spatial policy because it identifies the key elements of local space in accordance with the spatial policy of the central government and voivodeship government. It also has to take into account the principles of supramunicipal spatial planning. The studium primarily provides for the following:

The purpose and manner of development of individual areas, including areas excluded from building development;

Areas placed under protection due to their natural or cultural assets, along with the rules of this protection;

Directions of the development of technical infrastructure and transport system;

Areas where public investment projects of a local or supralocal character will be implemented;

Areas for which mpzp will be prepared because, for example, these areas are intended for the construction of large commercial facilities, or because of the anticipated changes in the ownership structure of properties (consolidation and division) [

86] (Article 9–10).

A studium is not an instrument of local law and, therefore, does not have a direct influence on the possibilities of developing individual properties by their holders. However, the provisions of a studium must be considered by the municipal authorities in the subsequently prepared mpzp. Therefore, the preparation of a studium is accompanied by a procedure ensuring that all the stakeholders can communicate and then, if necessary, defend their interests. Within this procedure, the municipal government announces the commencement of work on the studium and the possibility for natural persons, institutions economic entities, and so forth to submit proposals concerning the way of developing specific areas. The municipal government also consults the draft studium with the voivodeship government. The draft studium is also presented for public inspection so that citizens can submit comments, and a public discussion on the document is conducted. The validity of these comments is assessed and decided by the municipal authorities themselves (i.e., the municipal council) [

86] (Article 9,11).

The local spatial development plan (mpzp) prepared by the municipal government is the key spatial development instrument in the Polish legal system. The plan is the only planning document to have the status of a legal act and serves as the direct basis for issuing building permits. However, the preparation of the mpzp for the whole territory of a municipality is not obligatory. It should be prepared for areas designated for public purposes or large commercial facilities as well as areas where property consolidation and division is to be conducted. The mpzp must take into account the arrangements in the studium, making them more specific as appropriate. The scope of matters regulated by the plan is relatively broad and contains the following in particular:

Designation of land use and principles of building development (building lines, dimensions of buildings, building intensity, etc.);

Areas where building is prohibited;

Rules of protecting the environment, landscape, and cultural heritage;

Rules of property division;

Rules of building and modernising roads and technical infrastructure systems [

86] (Article 14–15).

Although a local plan is one of the responsibilities of a municipality, it has to take the interests of other public entities into consideration. The voivodeship and county government as well as several central government bodies have the right to consult the draft plan. The consultation of the draft with regard to issues related to the responsibilities of the individual bodies is the condition for the plan to come into force. The voivodeship government also has the right to expect the municipal spatial development (mpzp) to conform to the spatial development plan for the voivodeship (PZPW). However, a municipality may demand financial compensation from the voivodeship government for introducing the provisions of the PZPW to the mpzp. Entities other than public administration bodies, including natural persons, also have the right to influence the content of the plan. When the draft mpzp is being prepared, the date of presenting the draft for public inspection and submitting it to public debate is announced [

86] (Article 17).

There is a special type of local plan, namely, a local revitalisation plan (Polish miejscowy plan rewitalizacji), which is optional and prepared for areas covered by a municipal revitalisation programme. The scope of its provisions is expanded in relation to a “standard” mpzp. They include prohibitions and restrictions on commercial or service activities, as well as detailed rules concerning the development of public spaces or the organisation of road traffic [

86] (Article 37f–37g).

As already mentioned above, according to Polish law, spatial planning may also be implemented in areas not covered by an mpzp. In such a situation, administrative decisions issued by heads of municipalities are the basis for building permits. These decisions (with a slightly different content in the case of public and private investment projects) primarily contain provisions resulting from the legal regulations concerning the proposed investment project and its proposed location. Private projects may be carried out according to this procedure only within existing built-up areas or in their immediate vicinity. Decisions enabling investment projects in areas not covered by local plans must be consulted with all the administrative bodies concerned (especially central administration bodies). What is important, however, is that they do not have to be consistent with the studium [

86] (Article 60–61).

In Portugal, local planning is the responsibility of municipalities. The Portuguese system of spatial planning at the municipal level is more complex and involves more significant powers than is the case in the Polish system. The basic document prepared for the entire area of a municipality is the general spatial development plan (Portuguese planodiretor municipal (PDM)) [

100], which defines the general principles of development. This plan is obligatory except for areas covered by a similar intermunicipal plan. Furthermore, a municipality can draw up an urbanisation plan (Portuguese plano de urbanização (PU)) and detailed plans (Portuguese plano de pormenor (PP)) through which a PDM is implemented [

88,

89] (LBGPPSOTU Article 43; NRJIGT Article 95). Similar to a PDM, if a given municipality is already encompassed by an intermunicipal plan (PUI or PPI), the municipality does not prepare a plan of the same kind just for its own territory [

88,

89] (LBGPPSOTU Article 44; NRJIGT Article 27).

A PDM, similar to other plans prepared by a municipality, must conform to the regional programme and programmes prepared by the central administration [

88] (Article 44). A PDM is approved by a municipal assembly (Portuguese assembleia municipal). However, if its provisions are not consistent with sectoral, special, or regional programmes, a proposal for its ratification can be submitted. This ratification implies an amendment of the above programmes so that they reflect the current situation. This occurs only in exceptional cases [

89] (Article 90–91).

The provisions of a general plan cover a broad range of matters. For example, it defines:

Permitted functions of areas;

Criteria of location and development of industrial, service, commercial, and tourist activity;

Indices to be specified in the PU and PP;

The rules of protecting special values of space;

The form of road and technical infrastructure.

However, alongside these “classic” provisions, a general plan also contains provisions defining ways of achieving the proposed form of local space. For example, it specifies the rules of expropriation for public purposes, a programme for the implementation of public investment projects, and even a financial plan. A general plan also contains a timetable of actions to be taken [

89] (Article 96–97).

A consultation commission works during the preparation of a PDM. It is coordinated by the appropriate CCDR, whose members include the representatives of the central administration, an autonomous region, or intermunicipal units. The opinion presented by the commission concerns the compliance of the PDM with the law and the applicable programmes [

89] (Article 83,85). Public participation is ensured through a public debate lasting at least 30 days. The proposals submitted during this debate are reviewed by the municipal council, which has the right to reject proposals that do not comply with the law or spatial programmes and plans [

89] (Article 89).

An urbanisation plan implements the provisions of a general plan. It may be prepared for urban areas indicated in the applicable PDM and, if required by an integrated planning intervention, in the supplementary rural areas. A PU may also encompass industrial, service, or tourist areas. Furthermore, the land use regime should be determined in a PU for the administration centre of a municipality and areas inhabited by at least 25,000 people. An urbanisation plan defines the functions (residential, service, commercial, tourist, industrial, and waste management) and the rules of developing particular parts of an area as well as the form of the road, transport, and technical infrastructure network. It also indicates the location of areas and facilities with a public function as well as areas requiring regeneration and revitalisation. A PU also includes an execution programme and financing plan [

89] (Article 98–100).

The content scope of a detailed plan is evidently broader than in the case of an urbanisation plan. Alongside defining the functions of areas and rules of spatial development, a detailed plan determines a whole range of future actions of a given municipality (e.g., the rules of public space management and the timetable of public investment project implementation). A PP establishes the rules of performing urban planning work, indicates space designated for road and pedestrian traffic as well a green areas, and defines the urban planning parameters, such as the number of floors and building height [

89] (Article 102).

A detailed plan may come in three special forms, as required by local needs: a plan of intervention in rural areas (Portuguese plano de intervenção no espaçorústico), a detailed plan of city revitalisation (Portuguese plano de pormenor de reabilitaçãourbana), and a detailed protection plan (Portuguese plano de pormenor de salvaguarda). An intervention plan, prepared for rural areas, primarily establishes the rules of planning and transforming, if necessary, the existing state of spatial development. It also establishes the mechanisms for the protection of a natural and cultural landscape. However, such a plan may not change the purpose of a land from “rural” to “urban”. A detailed revitalisation plan is prepared for historic centres, whose boundaries are indicated by the previously prepared PDM or PU or urban revitalisation areas. Similarly, a detailed protection plan concerns areas of special historic and cultural value indicated in the appropriate legal regulations [

89] (Article 103–106).

The procedure for preparing an urbanisation plan and a detailed plan is similar. Similar to a general plan, they are prepared by a municipal administration. When drawing up the plan, a given municipality asks the appropriate CCDR for its opinion on the plan (Article 86). Residents of the municipality interested in the draft plan may participate in a public debate, which has to last for at least 20 days. However, the submitted objections to the draft plan are resolved by the municipal council, which then approves the plan [

89] (Article 89).

4. Discussion

Poland and Portugal are, as mentioned above, very similar countries despite the considerable geographical distance between them and their different size. They are at a similar level of socioeconomic development, their societies have a similar cultural profile, and both countries became free from authoritarian (Portugal) or outright totalitarian (Poland) rule relatively recently. At present, both Poland and Portugal are democracies where civic rights and ownership are respected. Thus public authorities in both countries have a similar scope of authority.

All these similarities notwithstanding, the possibilities of representing public interest in the spatial planning system turn out to be completely different. It is self-explanatory that the structure of spatial planning entities in Poland and Portugal reflects the administrative structure of either country. In general, it is based on four tiers: national, regional, supralocal, and local. The distribution of powers between these tiers is noticeably different in either country. In Poland, the key role is played by the local tier, which, by its very nature, must take both the public and private interest in planning decisions. This results from the fact that documents prepared by a municipality determine, directly or indirectly, the possibilities of developing specific areas. The supralocal (county) level plays an entirely marginal role because it does not have any planning powers as such. The content of documents at the voivodeship and national levels is intrinsically focused on public issues, but these documents have a rather complementary role with regard to their subject matter. It is significant that Polish spatial planning documents are focused on a strictly defined assignment of functions, with different levels of generalisation. In addition, local documents establish the rules of spatial development. The problem of implementing the adopted provisions appears only in governmental programmes, but the scope of their provisions is limited to specific domains.

The Portuguese realities are slightly different, although the municipality also is of key significance there. The municipality exclusively prepares plans that may directly provide the basis for issuing building permits. These plans, with a similar legal status, vary depending on the area they are concerned with. The powers at the supramunicipal level are similar to those at the municipal level because the former has a complementary and sometimes substitutive role in relation to the latter. Thus, the interactions between the public and private interest must be taken into consideration also by supralocal entities. The regional level, on the other hand—except for autonomous regions—is primarily an extension of the national level. The powers at the governmental level are based on the structure of documents, which is generally similar to their Polish counterparts: a document of a general character and specialised documents. They are all used to manifest the public interest, but the structure of these documents is much more complex and their content is much broader. It can also be observed that at each level, the subject of spatial planning in Portugal is broader than in Poland. Basically, all documents identify (at various levels of aggregation) the functions of the particular areas or centres as well as the distribution of the applicable public investment projects. Local and supralocal documents and, to a certain extent, regional documents and even some governmental documents also establish the rules of spatial development. Furthermore, a programme for the implementation of public investment projects and even a financial plan are often included in their provisions. The shape of Polish spatial planning, in its current form, is a kind of reaction to the planning system functioning in the communist period. At that time, spatial planning was hierarchical in nature and unconditionally favoured the public interest. At the same time, as private property was poorly respected, this resulted in large areas being allocated for public purposes (including the then state-owned economy) while limiting investment opportunities for the private sector. The political transformation in 1989 and the establishment of municipal self-government the following year caused the pendulum to swing the other way [

101]. The actual rank of the public interest is not only influenced by the provisions of the spatial plans and planning documents. Equally important are the relationships between documents manifesting the public interest of varying ranks (particularly local and central or regional) as well as those that also take private interest into account. To a large extent, a municipality in Poland is autonomous with regard to spatial planning. In particular, a local plan—the only document in Poland’s spatial planning system to have the status of a legal act—may be prepared without taking supramunicipal spatial planning into consideration. Considering a voivodeship spatial development plan in a local plan is obligatory only if an entity in the voivodeship plan meets several financial criteria. A voivodeship plan must be taken into account by a municipal development study (studium). However, due to the far-reaching difference of the scale between these documents (the number of municipalities in individual voivodeships ranges from about 100 to about 300), it is difficult and ineffective to disaggregate the provisions of a voivodeship plan and apply them to a particular part of a municipality. On the other hand, a hierarchy actually existed between the government’s national spatial development concept and a voivodeship spatial development plan. However, in the light of the weakness of voivodeship plans, this hierarchy had little significance for including the public interest in documents providing the basis for building permits.

The situation in Portugal is essentially different. As in a regional economic planning approach, public investments are highly ranged [

20]. A far-reaching hierarchy of spatial planning is a fundamental factor. Thus documents prepared by entities at a lower level must take into account the provisions of documents previously adopted by entities at higher levels of territorial division. This primarily concerns public-interest-related considerations included in the provisions of governmental (central and regional) spatial development programmes and reflected in supramunicipal or municipal plans. Although there is a procedure enabling the preparation of plans inconsistent with higher-ranking programmes, in this case, the approval of entities in these programmes is required.

Spatial planning in both countries is also an arena where the public and private interest clash. This primarily applies, of course, to planning at the local level, related to specific properties, and providing a direct basis for the development of a particular space. The private interest may influence the form of planning documents through a mechanism of public participation, guaranteed by law, during the preparation of drafts of these documents. In both Poland and Portugal, private entities have a range of possibilities to communicate their proposals. In Portugal, however, this is also possible in the case of programmes prepared at the regional and central levels. In both systems, the final decision on the approval of proposals submitted by private individuals and entities rests with the entities preparing the specific documents.

However, there are differences in the actual impact of the private interest on the spatial planning entities, including the possibility for these entities to oppose the claims and demands of private entities, which is based on the necessity to protect the public interest, particularly with regard to intangible values (e.g., spatial order and landscape). It seems that municipalities in Poland have more limited possibilities in this respect than their Portuguese counterparts, which stems from two reasons. First of all, most of the Polish municipalities cover a small area and have a small population (sometimes even smaller than 5000 people). In structures of this type, it is relatively easy for even relatively weak pressure groups (e.g., property owners or potential investors) to exert strong and effective pressure on the local government. What is more, given the above-mentioned lack of a real hierarchy in spatial planning, municipal authorities are in a situation of a “lone guardian” of the public interest. In Portugal, where an average municipality covers a larger area and is subject to pressure from higher levels of public administration, it is much more difficult to advance the private interest.

It can be assumed that the efficacy of representing the public interest in spatial planning is largely the inverse of its sensitivity to the private interest. Thus, to make some generalisations about spatial planning systems in terms of the role of spatial planning as an instrument for representing the public interest, it must be said that despite numerous similarities between the two systems, there are some far-reaching, even fundamental, differences between Poland and Portugal.

Poland’s spatial planning system can be described as a disintegrated liberal system. When the public interest is weighed against the private interest, the former generally holds a stronger position. Within the domain of the public interest, local interest, particularly associated with specific municipal investment projects, is most effectively represented. Against this background, the Portuguese system can be described as hierarchical and coherent, and thus totally different from the Polish system. In Portugal, the public interest, especially of a supralocal nature, enjoys a stronger position than the private interest. This undoubtedly applies not only to public investment projects but also to intangible values protected by spatial planning, such as landscape values and spatial order.

The relatively long period of membership of both countries in the European Union has not been reflected to a greater extent in the spatial planning systems of Poland and Portugal. Above all, it has not affected the similarity between these systems to a greater extent than currently observed. It is significant that since the 1990s, EU institutions have been trying, in a manner not formally binding, to set out the principles of planning to integrate spatially different levels of development policy, e.g., [

18]. Therefore, it seems that the EU cohesion policy has a more significant impact on the Portuguese, than, as COMPASS [

10], on the Polish spatial planning system. Thus, G. Cotella may be right [

102], who assesses that the ways in which public authorities in EU countries interact with space are increasingly diverse after 2000. This opinion coincides with the statement of A. Faludi [

103] that the influence of the EU on the spatial planning of the member states has slowed down in recent years, although it continues through the mechanisms of the European cohesion policy.

The persistent differences in planning systems, illustrated by the example of Poland and Portugal, may also lead to the conclusion (as, e.g., suggested by Reimer, Getimis, and Blotevogel [

9]) that adaptation processes, due to their legislative and cultural nature, are complex and slow. Hence, it is difficult to clearly assess them as convergence or divergence over a period of several years. At the same time, as T. Purkarthofer [

104] suggests, EU policies primarily influence the “soft” mechanisms of spatial planning. This influence is therefore perhaps more noticeable in the sphere of planning culture rather than legislative solutions. However, this is an issue that deserves separate research.