1. Introduction

The Central European settlement system was more or less complete in the 12th–13th centuries. Its original density corresponded to the economic and transport conditions at the time. Peasants had to go to the fields, work there and return within one day. This resulted in the high density of settlements in the original settlement system. In the present-day, agricultural work is mechanized and farmers commute to the fields using motorized vehicles. It is no longer necessary to have the dense settlement network that was present in the Medieval Ages. Although conditions have changed considerably, the settlement system seems to be surviving. Tradition, local identity and nostalgia sustain traditional villages.

However, this is not the whole truth. Many settlements have disappeared or have been destroyed in the whirlwind of historical events. In Czech territory alone, this means approximately a thousand villages. There are two main groups of reasons in general for such development. Some villages were artificially destroyed to give way to civil engineering structures or were destroyed by wars or various catastrophes. Another large group of villages disappeared as a result of being abandoned by their inhabitants. Some rural settlements do not exist any more and only the remains of the foundations of the original buildings can be seen today. Other rural settlements have been transformed into second homes, without any or only a minimum of permanent residents.

During World War II, thousands of villages were destroyed in Europe. They were destroyed during the fighting or were burned as part of Nazi terror. Some of the destroyed villages were left as monuments for reverent reasons. The most famous Czech case is Lidice. It can be assumed that most of the destroyed villages were restored after the war, but the available literature focuses more on urban renewal. However, this issue is not the subject of this article. Theoretically, it could be more about the consequences of an ethnically-based population change. A significant difference in terms of memory is that places of struggle are usually celebrated or used for propaganda, while in places of ethnic change, the system tries to forget the original inhabitants. Under the conditions of Czechia, the situation at the end of WWII and after establishment of the iron curtain had a considerable impact on the present situation. Some villages were not re-settled after expulsion of the German population. Some others were deliberately destroyed in order to create buffer zones without permanent settlements on the borders.

The concept of ethnic cleansing did not appear in the literature until around 1990 [

1]. However, this phenomenon appears in modern history in connection with colonization, when it comes to cleansing from the original population [

2]. In the last century, it was a purification in the name of nationalism, which significantly affected Europe in particular. In the interwar period, it mainly concerned the Balkans. The Stalinist regime in the USSR moved entire nations according to political needs. Large ethnic cleansing was associated with Nazism—the Holocaust, plans for the partial liquidation and displacement of the Slavic population, as well as the expulsion of 100,000 French people from Alsace-Lorraine. In the post-war period, among other things, about 14 million Germans from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Yugoslavia and Romania were displaced. In the recent past, we have witnessed ethnically conditioned shifts in relation to the break-up of Yugoslavia.

However, most of the literature focuses on the political and social context of ethnic cleansing (often ideologized), while the impact on landscape and settlement remains in the background. These issues have been largely tabooed in order to forget the original inhabitants. Therefore, mentions can be found more in foreign literature [

3]. Our contribution tries to fill the existing gaps.

The process of extinction of small municipalities is considered a tragedy. But is this really the case? From which point of view is this a negative trend and to what degree does this rationalize the national settlement system? What really happens when a village loses its permanent population? Is there any way to retain the genius loci, identity and memory of abandoned villages? These are the research questions that our article will endeavour to answer.

Older theories concerning rural settlements dealt with the types of ground plans of villages and their relationship to the structure of fields [

4]. Individual settlements are analyzed separately. Their eventual extinction was also often individual—due to floods, fires, epidemics and attacks by enemies. The more frequent extinction of villages in earlier history is associated with the consequences of the Thirty Years’ War.

National state is connected with the theory of National Settlement Systems (in the Czech Republic, Dostál and Hampl [

5], which shows the top-down hierarchy of settlements. The fundamental theory of central places was introduced by W. Christaller [

6], who explains the bottom-up hierarchy. The theory of central places was applied in Czechoslovak planning practice during the Communist regime by creating a system of central places of three hierarchical levels, and dividing non-central places into settlements of permanent significance and of non-permanent significance. The role of normatively defined centers across the national territory was to provide basic public amenities where inhabitants from particular hinterlands were able to meet their needs for education, health care or social care. At the end of the socialist period, the Czech urban system was largely comprised of a dense network of hierarchically structured urban centers, which played the key role of local centers for rather well-defined hinterlands, especially in the peripheral and rural regions [

7].

On the other hand, populated settlements of non-permanent importance were not equipped with infrastructure and had a building closure. Their gradual disappearance or the loss of their function as permanent housing was expected. This approach has been frequently criticized due to its central enforcement, finality and unilateral foundation on the simplified criteria of economic advantage. Intangible aspects, such as the nostalgic relationship of citizens to their community, the preservation of cultural and mental values were not taken into account.

This objective process continues in the market economy, even though it does not receive more support from the center. The smallest settlements are threatened with depopulation, even the most basic services disappear from them and there are usually no human or financial resources for any development. It is this category of settlements that may be the subject of further consideration regarding the extinction of settlements as sites of concentration of permanent housing for the population. There are naturally also villages whose predisposition to extinction has not been confirmed. This is caused, among other things, by changes in the trends of urbanization processes.

Present settlement theories react to post-productive transition and globalization. In Europe, global approaches related to a unified continent are utilized in addition to emphasis on regional identities [

8]. The settlement system of Visegrád countries was analyzed e.g., by Hajdú et al. [

9]. Bole et al. [

10] explain the transition of functions of individual parts of the Slovenian settlement system: large and medium-sized towns are changing from having an industrial function to becoming seats of high quality services and creative industries, small towns are changing into modern industrial centers, rural settlements in the vicinity of regional centers are affected by suburbanization and peripheral rural settlements are shrinking. In some countries, depopulation of small villages is a current theme [

11]. It is especially important in countries with not just rural to urban migration, but an overall decrease in population (emigration to developed countries), which manifests as a substantial reduction of the rural population [

12,

13]. Rumyantsev et al. [

14] mention rural settlements without any population.

The majority of settlement theories analyze the upper level of the system (metropolises, regional and sub-regional centers, cities and towns). Rural settlements receive only marginal attention as a rule. However, there are some urbanization processes, which also concern the countryside. One of these is suburbanization, which transforms central areas into an urban-rural continuum [

15], where individual settlements and their original character almost cease to exist. We can mention disappearing villages, not in the physical sense but in the sense of the loss of their rural character and also identity.

Physical disappearance mostly concerns some very small villages in peripheral regions. Increasing mobility allows the local population to meet requirements for job opportunities and services in increasingly distant centers. At the same time, the sharp drop in employees in the primary sectors of the national economy frees people from rural areas. The functions of housing and newly developing tourism usually remain, but they do not seem to develop in each of the existing villages. This is the basis for the gradual disappearance of the permanent settlement function in some settlements.

Unless this concerns targeted liquidation of a village that needs to give way to an investment intention, the termination of a settlement is usually gradual. In literature, this process is sometimes called shrinkage [

16]. Its features are usually closure of the last services (post office, school, shop, restaurant, library), a fall in the number of permanent residents and usually conversion of part of the housing fund into second homes or hospitality facilities [

17], sometimes adding an environmental format [

18]. At present and in the near future, the opposite process is not ruled out—i.e., the retroactive conversion of cottages into permanently inhabited apartments. On the other hand, suggestions by some experts for settlement of abandoned villages by immigrants from abroad with a different culture [

19] cannot be recommended. This would result in formation of a ghetto of people, whose assimilation would be almost impossible in real time.

The problem of abandoned villages is current in some South and East European countries. This is mainly the result of depopulation due to post-industrial changes in the countryside. Felipe and Mascarenhas [

20] document such a situation in Portugal, pointing out that significant cultural heritage is disappearing along with the villages. Di Figlia [

21] hopes that although the abandoned villages ceased to exist, their memory could be preserved. Rural landscape changes due to abandoned settlements are generally emphasized [

22].

Under Czech conditions, post-war abandonment is connected mostly to expulsion of the German population [

23]. A similar experience can also be found in Poland [

24,

25] and Slovenia [

26]. In the former Soviet Union, the extinction of villages in the last century has been associated with violent collectivization [

27]. In Israel, villages abandoned by Arab citizens after the Arab–Israeli wars (1947) were demolished in the 1960s [

28]. Bański and Wesełowska [

29] discussed the broader spatial and socio-economic contexts. European literature mainly discusses villages that disappeared during the Middle Ages [

30,

31], often perceived as an archaeological subject. In the Mediterranean, in the Balkans, and some other parts of Europe, this is still a current problem in relation to abandonment of the countryside and land [

32]. Re-use of abandoned buildings is widely discussed [

33], particularly in relation to an eventual tourism function [

34], for the purpose of social agriculture [

35] or for the creation of ecovillages [

36].

The expulsion of the German population from the Czech borderland and big cities is one of the consequences of WWII. Specific numbers vary. It is estimated that approximately 2.2 million Germans were moved to the US and Soviet occupation zones in Germany. Additionally, about 300,000–500,000 Germans from Czechoslovakia were killed on the front lines during the war, about 300,000 escaped on Hitler’s command, about 200,000 remained missing and between 19,000 and 30,000 died or were killed during uncontrolled expulsion before the official displacement was organized. The number of losses is higher than the number of Germans before the war, because hundreds of thousands fled to the Czech Republic before the end of the war. In any case, the Czech Republic lost more than 2 million Germans, the majority of them from the borderland.

Not all villages were re-settled after the expulsion. New settlers were directed towards towns and larger villages in lower-altitude valley locations. Many small settlements in the highlands and mountains were not re-settled or their re-settlement was not successful. The population moved from mountains to the valleys, which had subsequent disastrous consequences due to exposure to flood hazards [

37]. Additionally, in relation to the establishment of the iron curtain, some settlements in close vicinity to the borders were destroyed with the goal of creating an empty buffer zone.

Some settlements had to give way to various technical works and other purposes. The liquidation of settlements due to military training areas commenced during the Nazi occupation and continued even after the war ended. Evacuated villages in military areas were often used as training targets for the artillery. Later on, villages were destroyed due to construction of (coal) mines, water reservoirs and nuclear power plants. In such cases, the destruction was organized and residents were usually moved to new flats and houses in other settlements in a planning way.

The aim of the article is to clarify the causes of the extinction of villages, its impact on the landscape and on the settlement system, as well as the possibilities of preserving the historical and cultural memory of extinct places. Finally, the danger of extinction of villages at the present time is discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

Abandoned villages can be studied within the terms of various disciplines. Archaeology examines features of physical substance and culture [

38], anthropology is interested in the human aspect of things and the immediate context of extinction [

39], geography examines the spatial distribution of extinct villages and the broader context.

A spectrum of geographical, sociological and ethnographic methods was used for analysis of abandoned villages in Moravia. This consisted of a combination of analysis of statistical data, secondary and cartographic sources, field research and remote sensing methods (including old aerial photographs).

The first step was to identify municipalities and parts of municipalities that disappeared from statistics during the second half of the 20th century. It was then determined to what extent the statistically extinct settlements also physically disappeared. A field search followed, which included the exact location of the defunct village and identified any remains or references directly in the field. The results of historical mapping and aerial photographs were used. The results were photographically documented. This more detailed research took place in Moravia and in the Czech part of Silesia in 2020. Further information was sought on the identified extinct settlements. Archival and museum materials, secondary sources and consulting with local experts were used.

The main weakness in the methodological area is the lack of data from the period before, during and just after the war. Some archives were destroyed, others moved to an unknown location. A lot of information can be found in Soviet archives, which are difficult to access. For villages that disappeared later, the information situation is better.

The research area was defined by the historical territory of Moravia and Silesia and the observed timeline was determined from 1945 to the present. The study unit for the extinct settlements research was determined as municipality, part of municipality or hamlet with at least 5 residential buildings registered as of 1930. The term village, settlement or hamlet refers to a spatially separated physical structure in the landscape, consisting of residential buildings eventually also other buildings. The term municipality or commune refers to the smallest unit of state administration and self-government. The municipality may consist of several villages. Small municipalities are municipalities under 500 inhabitants, very small municipalities have less than 200 inhabitants. The identified settlements were localized on the basis of comparative analysis of historic statistical information about the numbers of residents and buildings according to Statistical lexicon of municipalities in the Czechoslovak Republic, on the basis of a census dating from 1 January 1930 with current public statistical data.

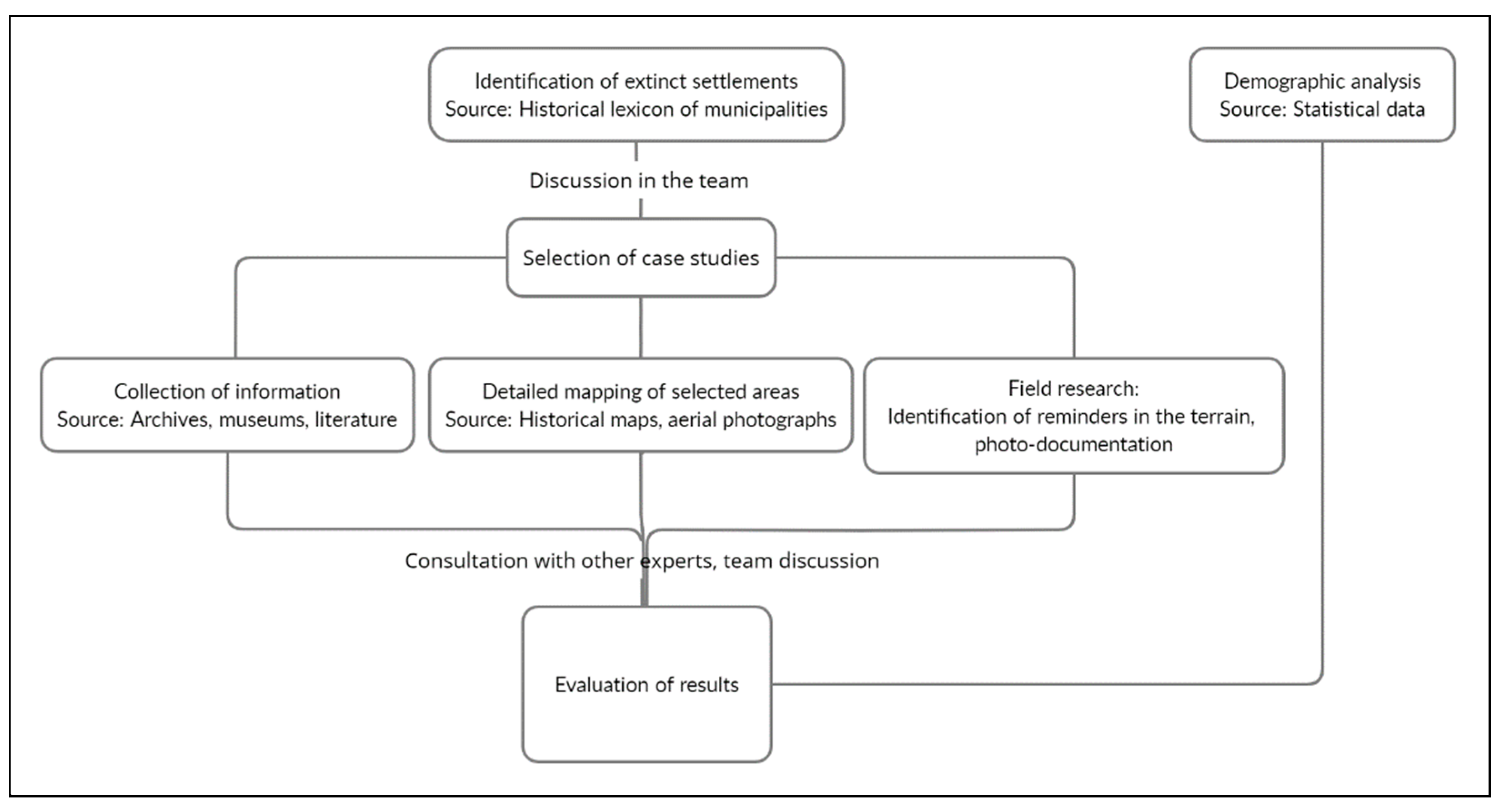

From this group of the settlement, the physically extinct settlements were chosen (i.e., settlements with the loss of settlement function in the period after 1945 in relation to destroyed most of the original buildings). The physical extinction of a settlement was verified by analysis of historic map materials, aerial survey images (from 1936) and present orthophotomaps. Field research was subsequently carried out. Concentrations of endangered municipalities were evaluated cartographically. The procedure is in

Figure 1.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Evidence of Extinct Settlements

Most of the extinct settlements are located in the borderland (along the inner border of the Czech Republic). This phenomenon is mainly associated with the expulsion of the original German population after World War II. However, the area is also affected for other combined reasons associated with post-war geopolitical development—particularly the declaration of a forbidden border zone established along the western border of the territory and the establishment of military training areas. The area with extinct villages copies the entire then border with Germany (which is today part border with Poland) and a large number of extinct settlements are also located near the border with Austria (particularly at the border with the South Bohemian Region). With a few exceptions, we can find only a few extinct settlements in the interior. The reason for extinction in this case is usually construction of infrastructure.

In general, there is a spatial disproportion in the distribution of extinct settlements within Bohemia on one hand and Moravia and Silesia on the other hand. Exact numbers are not available for comparison due to the inconsistent methodology of identification and location of extinct settlements. However, the estimate of the number of extinct settlements in Bohemia is ten times higher than the number in Moravia and Silesia. The amount of extinction of settlements due to mining is also significant in North Bohemia.

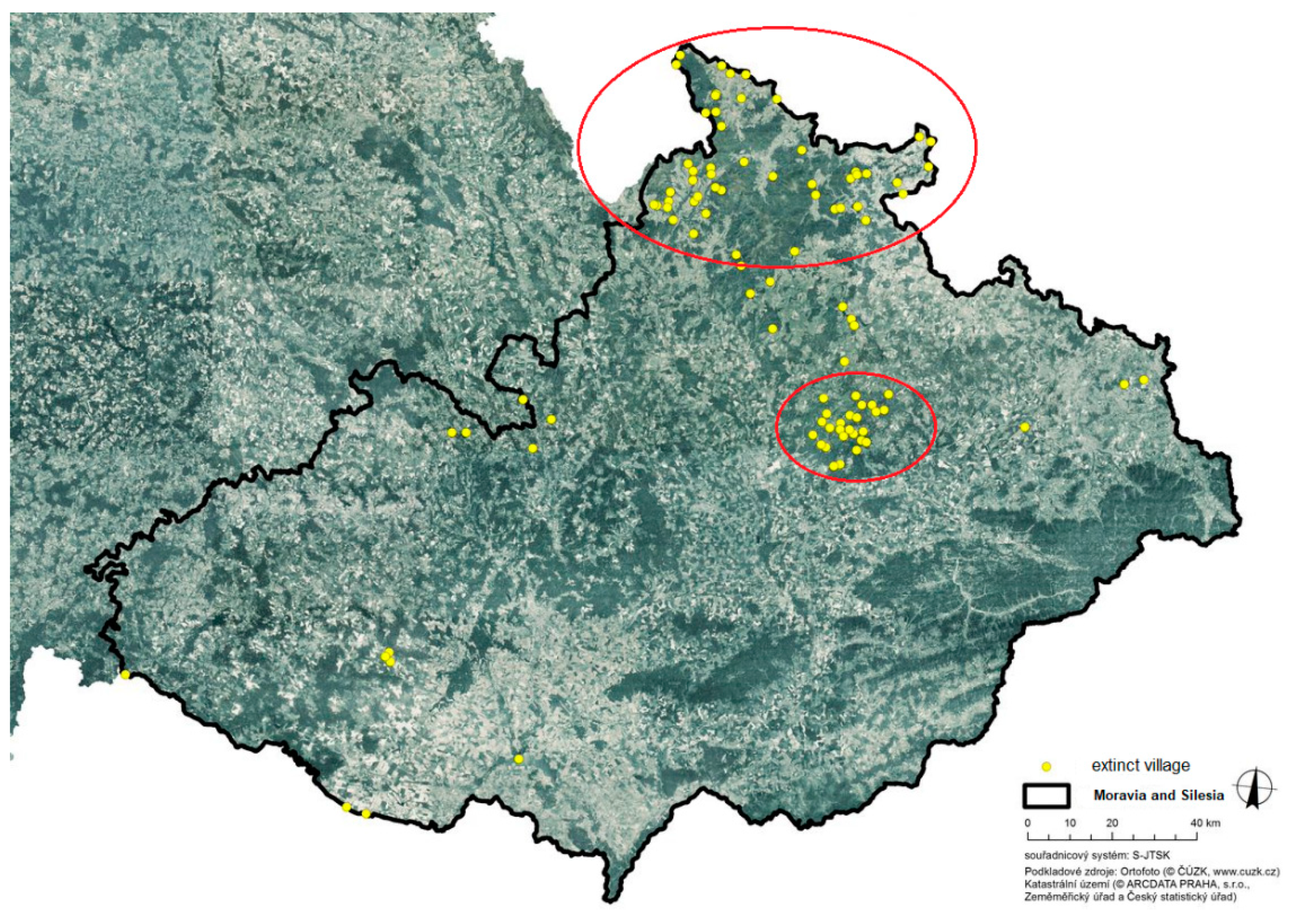

3.2. Abandoned Villages in Moravia and Silesia as a Case Study Region

About one hundred extinct settlements can be identified within Moravian and Silesian territory—these settlements can be classified as physically abandoned (in terms of current physical structure) during the period after 1945. The most greatly affected areas are in Sudetenland (the mountain range between the Moravian Gate and the passage of the Elbe near Hřensko) associated with the expulsion of the original German population. The districts of Jeseník, Bruntál and Šumperk were most heavily affected—a total of two thirds of all extinct settlements in Moravia and Silesia are located there (border area in

Figure 2). Another numerically significant group consists of a cluster of municipalities that disappeared as a result of establishment of the Libavá military district (a total of 26 settlements, the area in

Figure 2 in the interior). An interesting fact is that only three settlements within the entire area of Moravia and Silesia disappeared due to the establishment of a forbidden border zone. Other reasons are attributed to just a few defunct settlements—due to the construction of the Dukovany Nuclear Power Plant, water reservoirs, deep black coal mining or the construction of an airport.

The map shows the significant territorial disproportion in relation to abandoned settlements on the north-south axis. Most of the extinct villages are located in the northern part of Moravia and Silesia. The environmental conditions (particularly the significantly colder climate, the higher altitude, the ruggedness of the terrain and the poor fertility of the soil) can be pointed out as a significant implicational reason for settlements disappearing in this area in the broader scope. These factors complicated re-population of areas during the subsequent period, while settlements in the South Moravian borderland were usually re-settled due to prosperous agriculture and viticulture.

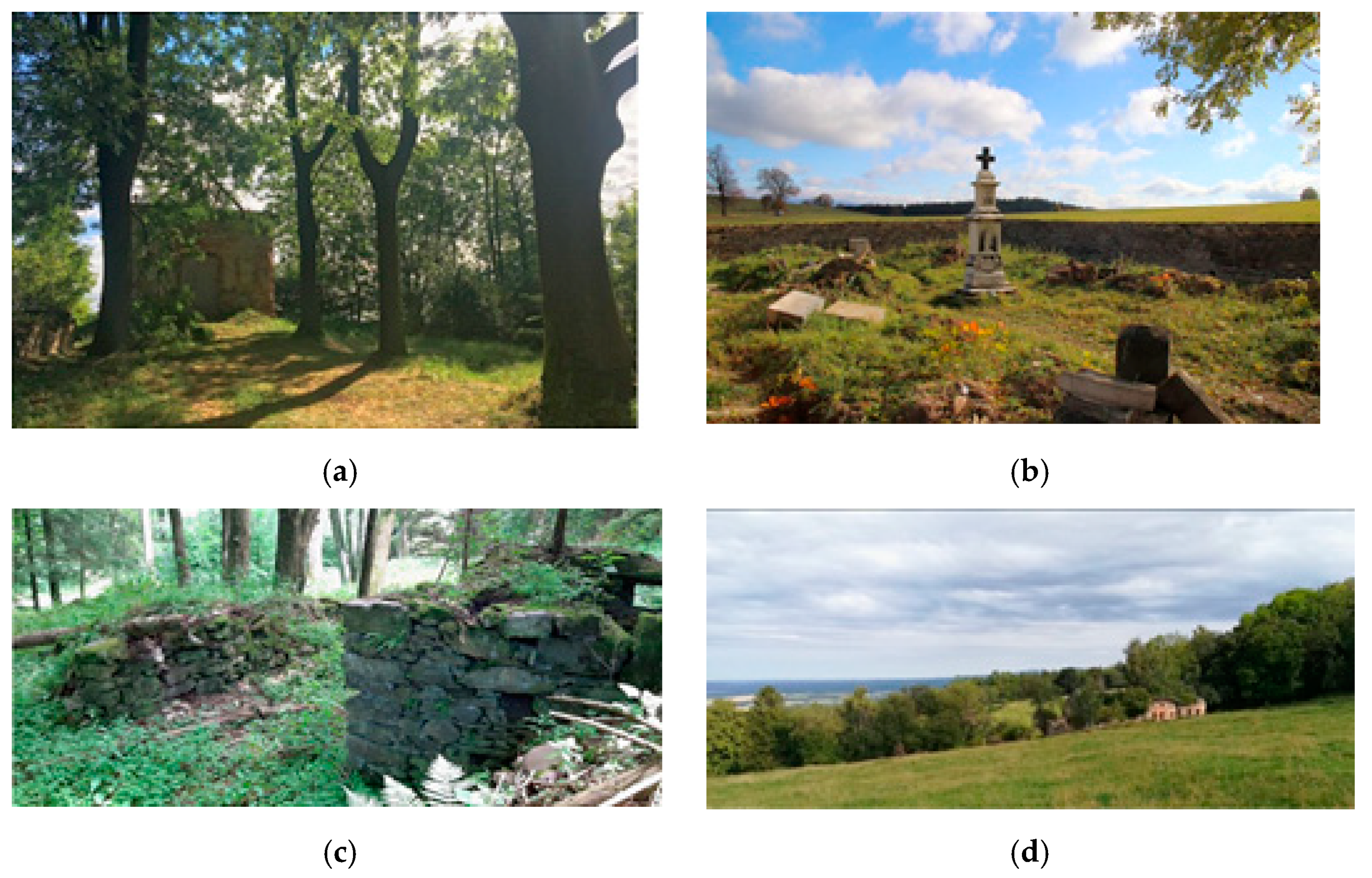

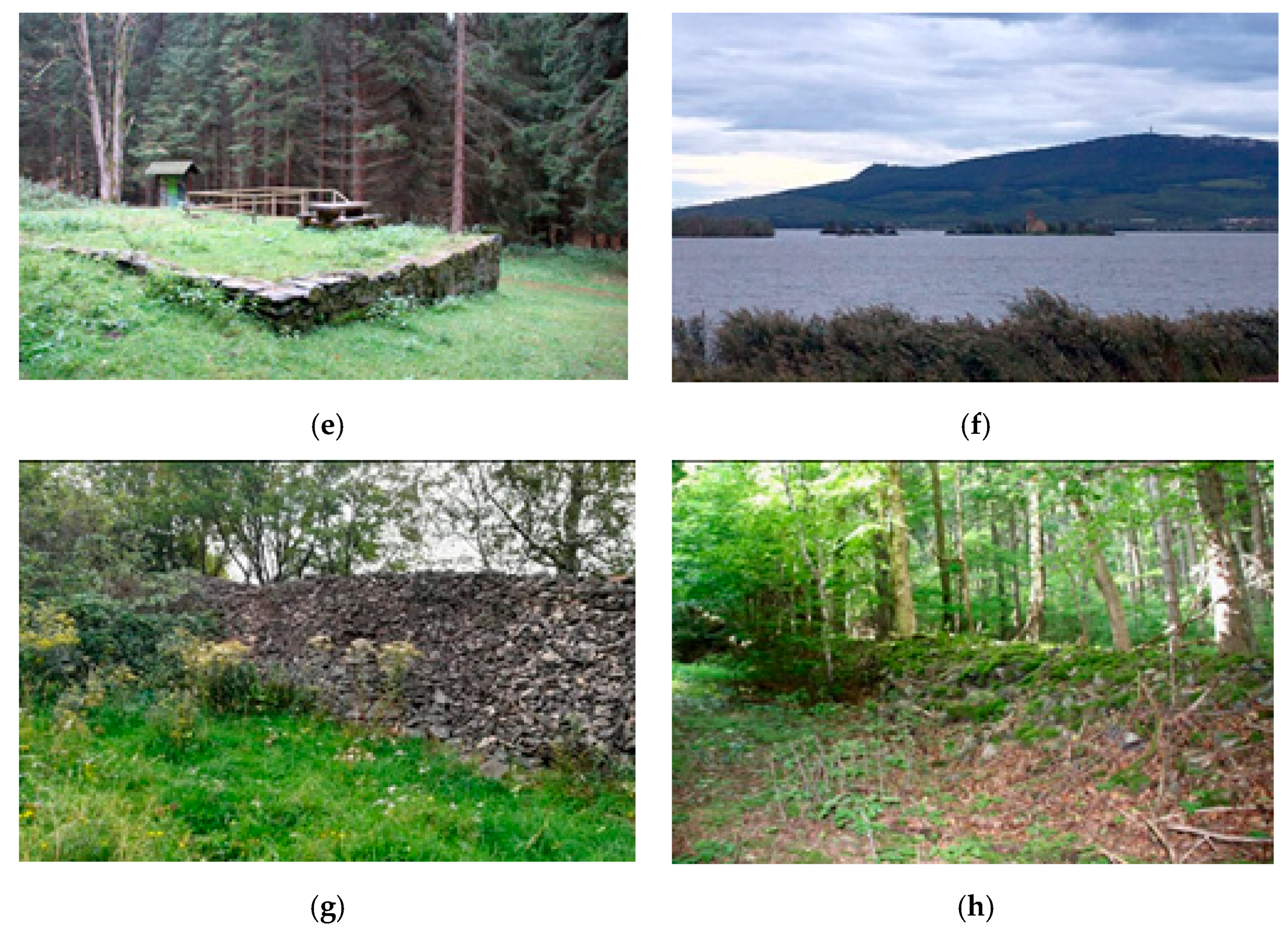

3.3. Analysis of the Course, Reasons and Results of the Villages Abandonment

In the case of settlements that were not re-settled after expulsion of the German population, unused buildings were usually dismantled and used as building materials elsewhere. The rest were deliberately destroyed in the 1950s, as dilapidated buildings posed a security risk and worsened the image of border regions. Some isolated buildings remained and were usually secondarily used as warehouses, dormitories for seasonal workers, farm buildings or second homes. In this area of the borderland, we can find numerous ruins and other remains of the original settlements. Sometimes a religious artefact survived, such as a torment, ruins of chapels or churches, or a cemetery. These sacral artefacts had been in a desolate condition after the 1950s. Sometimes, it was voluntary associations who restored these buildings and preserved their history for the public. Local memory is currently being restored in some places, for example, as part of the creation of educational trails or simply as a result of restoration of sacral elements.

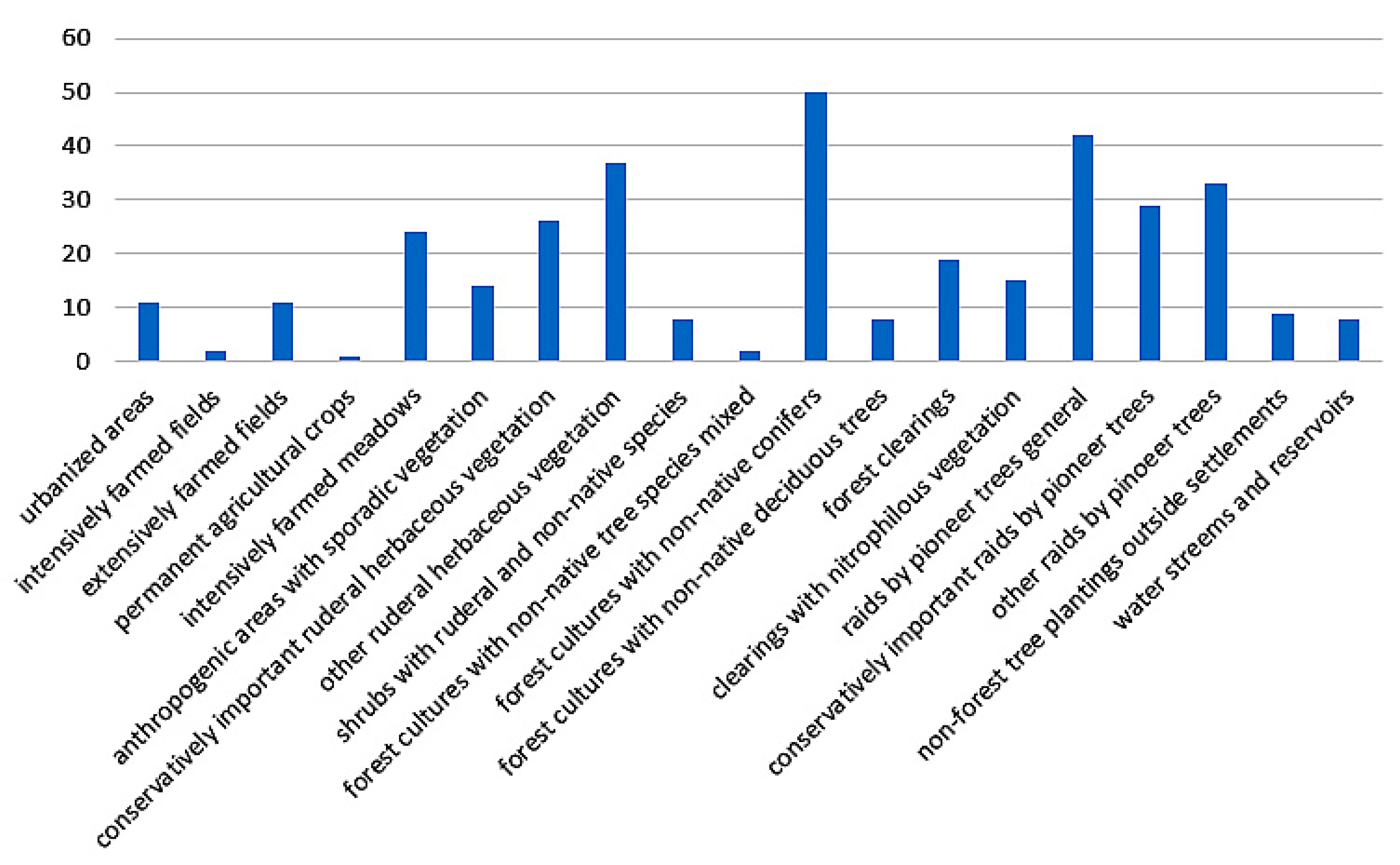

The localities of abandoned villages manifest differently in the field. From the point of view of the relation to the landscape, the essential question is what arose in the territory of extinct villages. For this purpose, the representation of individual habitats was analyzed [

40]. For each defunct settlement, individual types of natural and non-natural habitats were searched for, which are currently located on the territory of the former built-up area of the defunct settlement and its adjacent landscape, or in the entire cadastral area of the defunct settlement.

The natural habitats in the areas of extinct settlements are dominated by mesophilic oat-grass meadows (located in the territory of 70% of all extinct settlements), riverine ash-alder woodland, florid beech forests and high mesophilic and xerophilic shrubs. Among the non-natural habitats (

Figure 3) in many areas of extinct settlements, there are ruderal herbaceous vegetation typical of desolate habitats of ruins, as well as conservation-significant stands with the potential to develop and transform into natural habitats, forest cultures with non-native conifers in the territory of 80% of all extinct settlements, as well as conservation-significant stands, which have the potential to develop natural forest vegetation and which are typical of overgrown borders and heaps with deposits of stones from fields and demolished foundations. Of the habitats, units for the conversion of natural habitats to Natura 2000 habitat types, Tilio-Acerion forests on slopes, rubble and ravines, mixed ash-alder floodplain forests of temperate and boreal Europe and non-priority extensive mowed lowland meadows are the most represented in extinct settlements.

The causes and manifestations of village extinction are clearly shown in

Table 1.

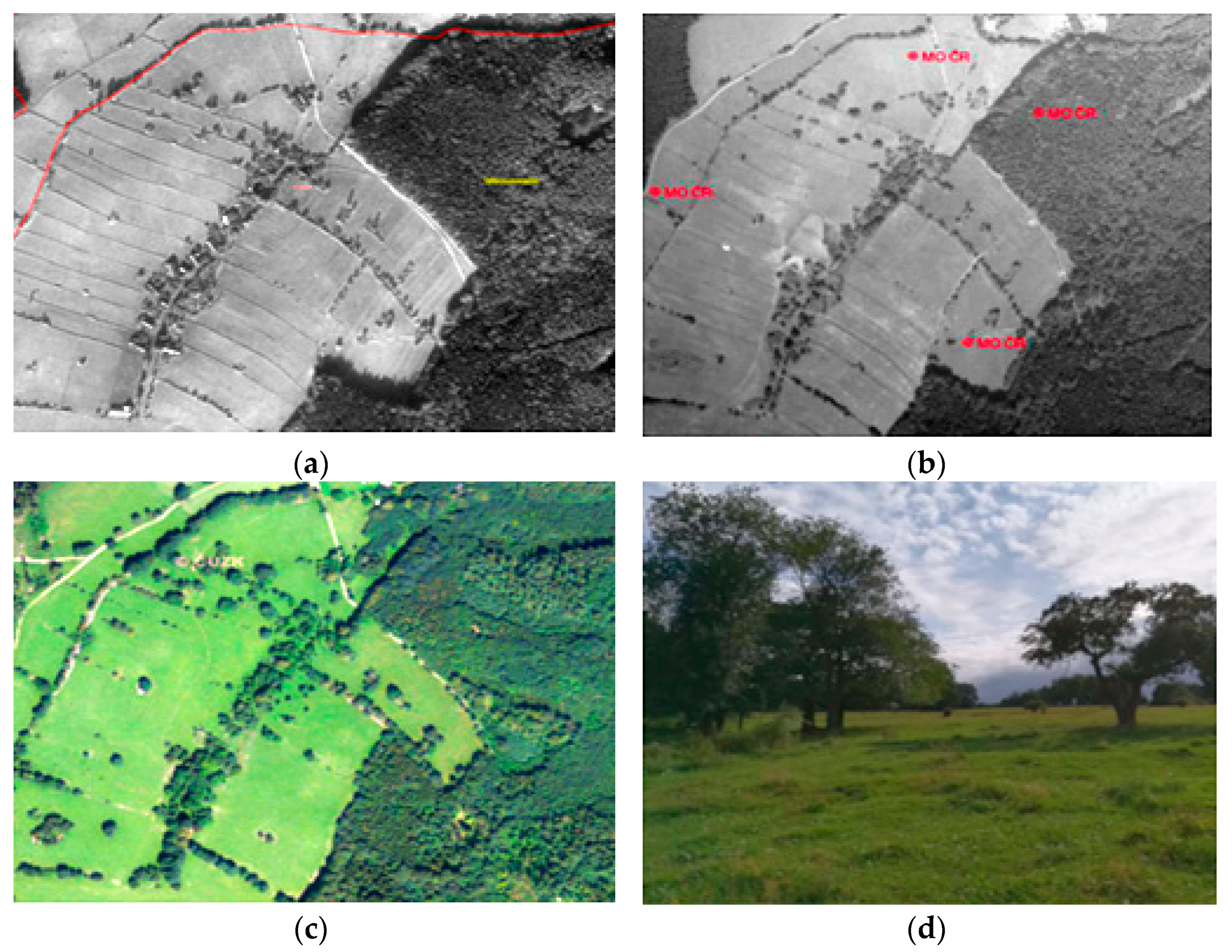

Examples of contemporary reminders of extinct settlements can be found in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

As part of political liberalization in the 1990s, some military areas were terminated or reduced, especially after the departure of the Soviet Army from Czechoslovakia. This also enabled the theoretical restoration of permanent settlement. However, this effect on the settlement system has similar problems to the effect on villages in peripheral areas [

41].

3.4. Demographic Analysis and Urbanization Process

The depopulation of villages on the border is taking place against the background of ongoing urbanization processes. In the second half of the 20th century, it was a one-way rural-to-urban migration. This process was supported by the so-called centralized settlement system, where state-controlled or supported housing construction was concentrated in cities and other centers, while in the case of so-called municipalities without permanent significance, there was a building closure.

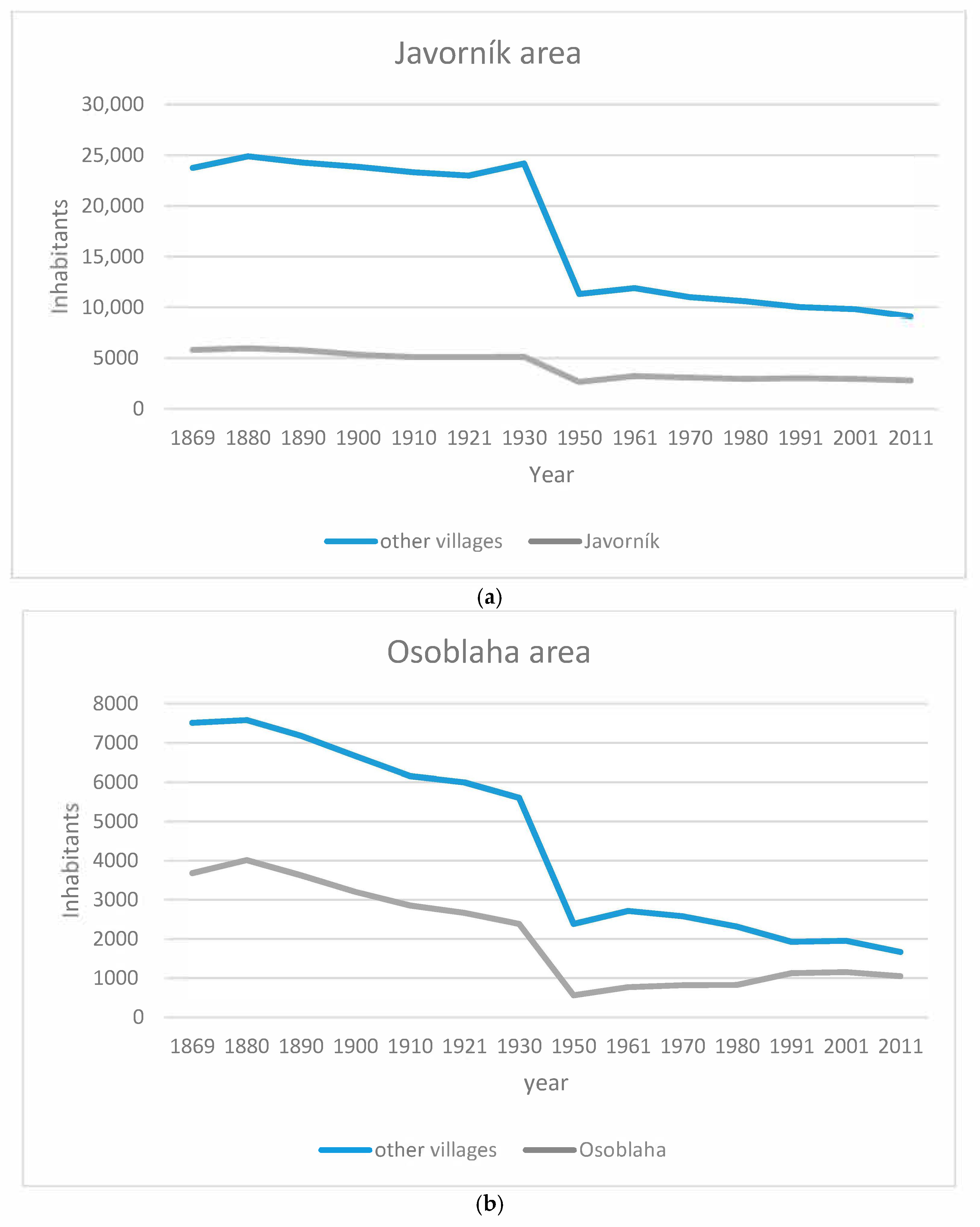

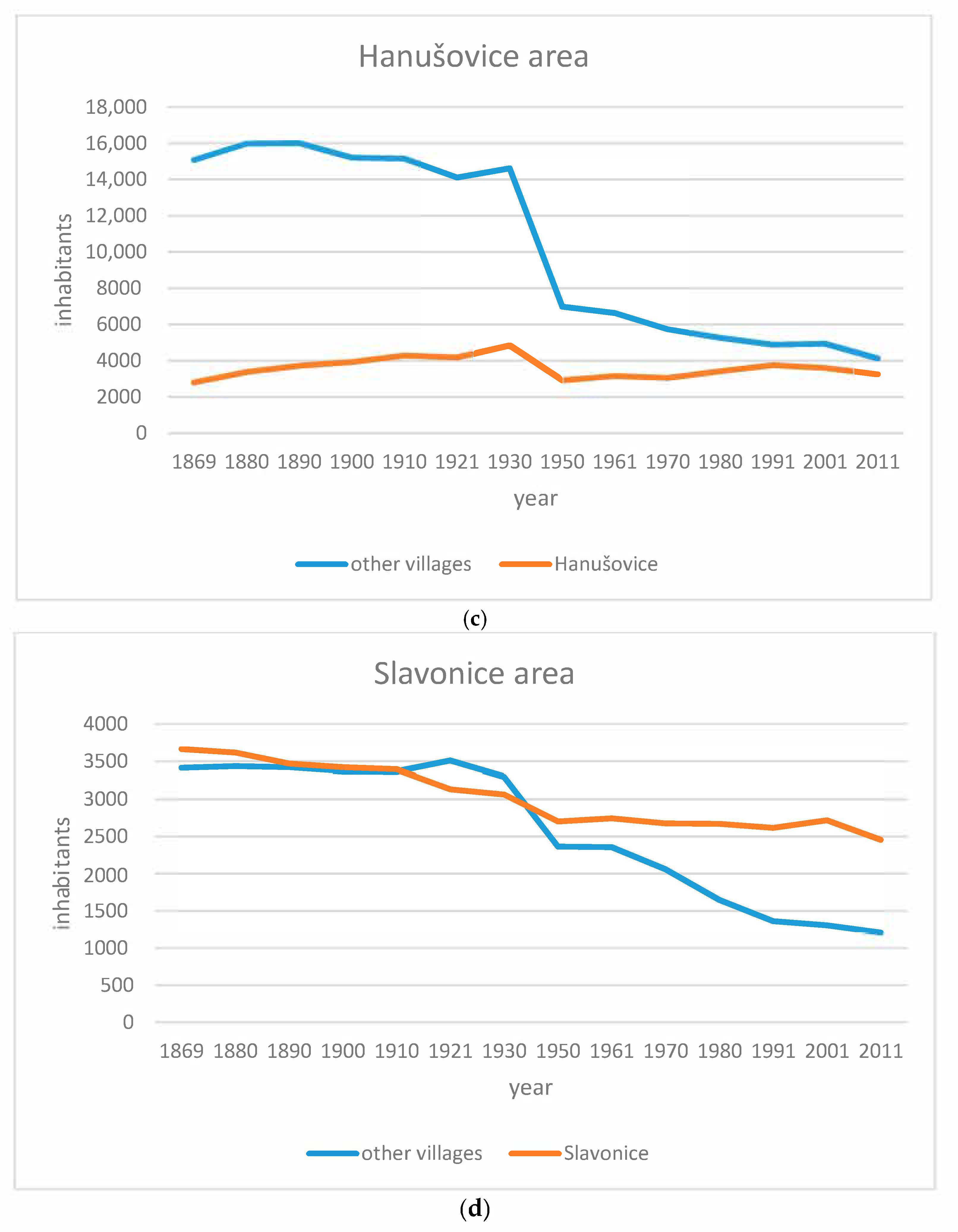

The result of this process was not only the depopulation of border areas (except for heavily industrialized), but also the concentration of inhabitants in cities and other selected centers. This process undoubtedly contributed to the extinction of small villages in remote locations. Some examples of such a development can by found on figure Z where four borderland areas were choosen.

Javorník area (

Figure 6a) is situated in the Czech part of Silesia near the present border with Poland. It is separated from the Czech hinterland by the ridges of the Rychlebské Mountains. It consists of 13 municipalities. In addition to small municipalities, there are three small towns in the area. A total of 23 settlements disappeared here after World War II.

Similarly, the Osoblaha area (

Figure 6b) is located in the Czech part of Silesia. The microregion has a reputation as one of the most remote areas in the Czech Republic. The peculiarity of this micro-region, consisting of 7 municipalities, is the absence of any urban center. However, even here, the proportion of the population living in the central settlement has increased. A total of 6 villages disappeared here after World War II.

Hanušovice (

Figure 6c) is located in northern Moravia. Unlike other selected cases, Hanušovice was an industrial center (textile and food production), in neighboring Jindřichov, there was a paper mill. The micro-region consists of 8 municipalities, two of which are small towns. After World War II, 17 settlements disappeared in the Hanušovice area. Here, the concentration of inhabitants in the center is most striking—probably due to the complex relief, which increases the remoteness of settlements outside the main valley.

The Slavonice area (

Figure 6d) represents the example of southern Moravia, where the extinction of villages is not so common. It is a small area, consisting of 4 villages, where, however, after the Second World War, 5 villages disappeared. It is quite obvious that the depopulation of the small town of Slavonice is gradual, as rural villages have experienced a relatively steep decline.

In all cases, it turns out that the sharp decline in the population of non-central municipalities occurred between the censuses of 1930 and 1950, i.e., in connection with World War II. This would point to an obvious connection with the expulsion of the German population. However, if we looked at the population development of municipalities on the opposite side of the border in Austria, Bavaria or Saxony, we would also find significant depopulation tendencies. For example, the population of Waldkirchen an der Thaya, opposite Slavonice, fell from 1379 to 522 between 1939 and 2019, with 6 out of 7 villages having less than 100 inhabitants. The difference is that in neighboring countries, this process has taken place gradually. It turns out that the expulsion of the Germans was not so much the cause of the extinction of the villages, but rather the catalyst for a process that tooks place naturally.

It is clear from

Figure 7 that there are mainly very small settlements among the villages that disappeared on the border. The population of most of them fell below 100 before the war. As for the villages, which disappeared in a planned way, because they had to give way to military premises or large investments, there are rather small villages slightly over 200 inhabitants.

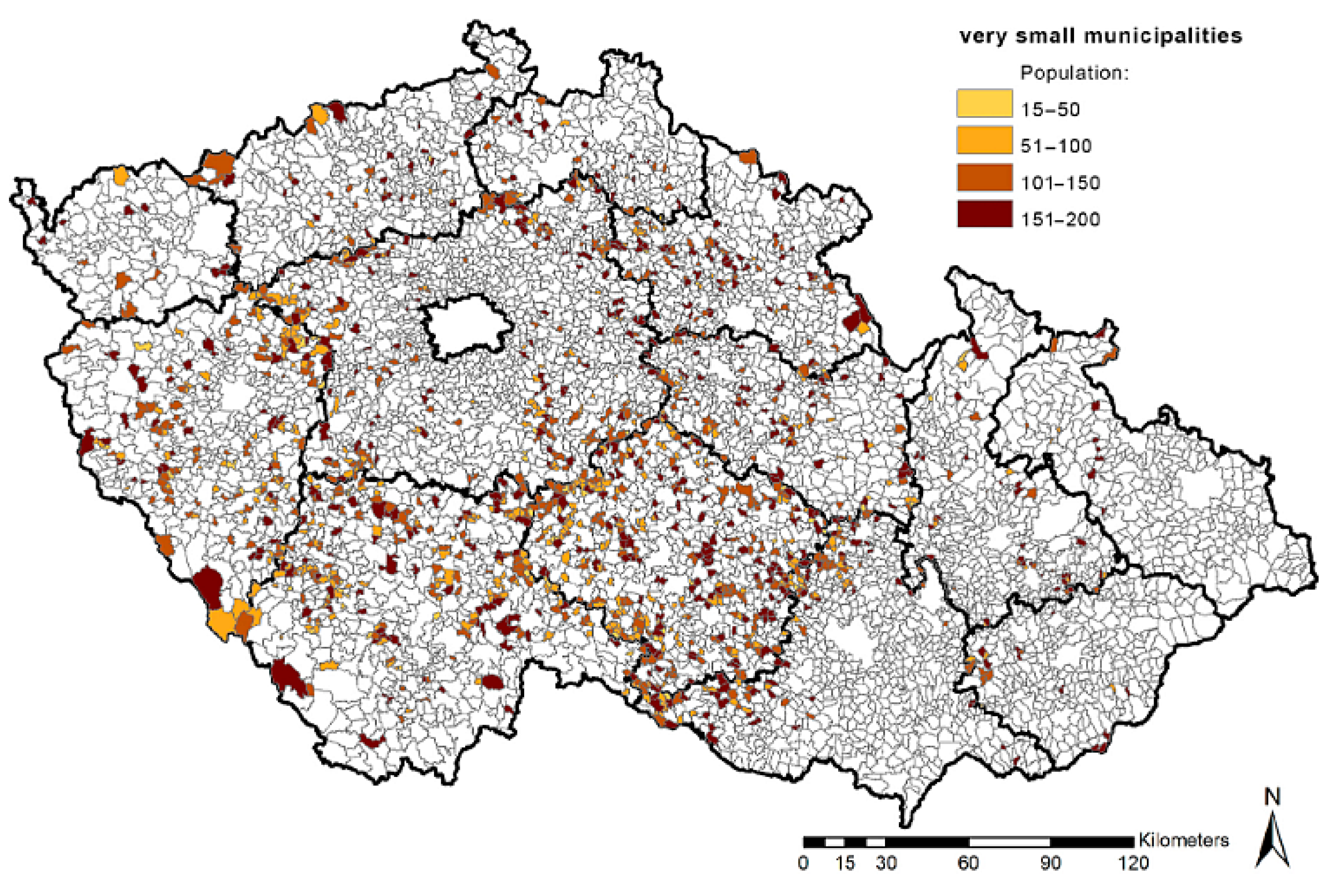

3.5. Depopulated Small Villages in Czechia at Present?

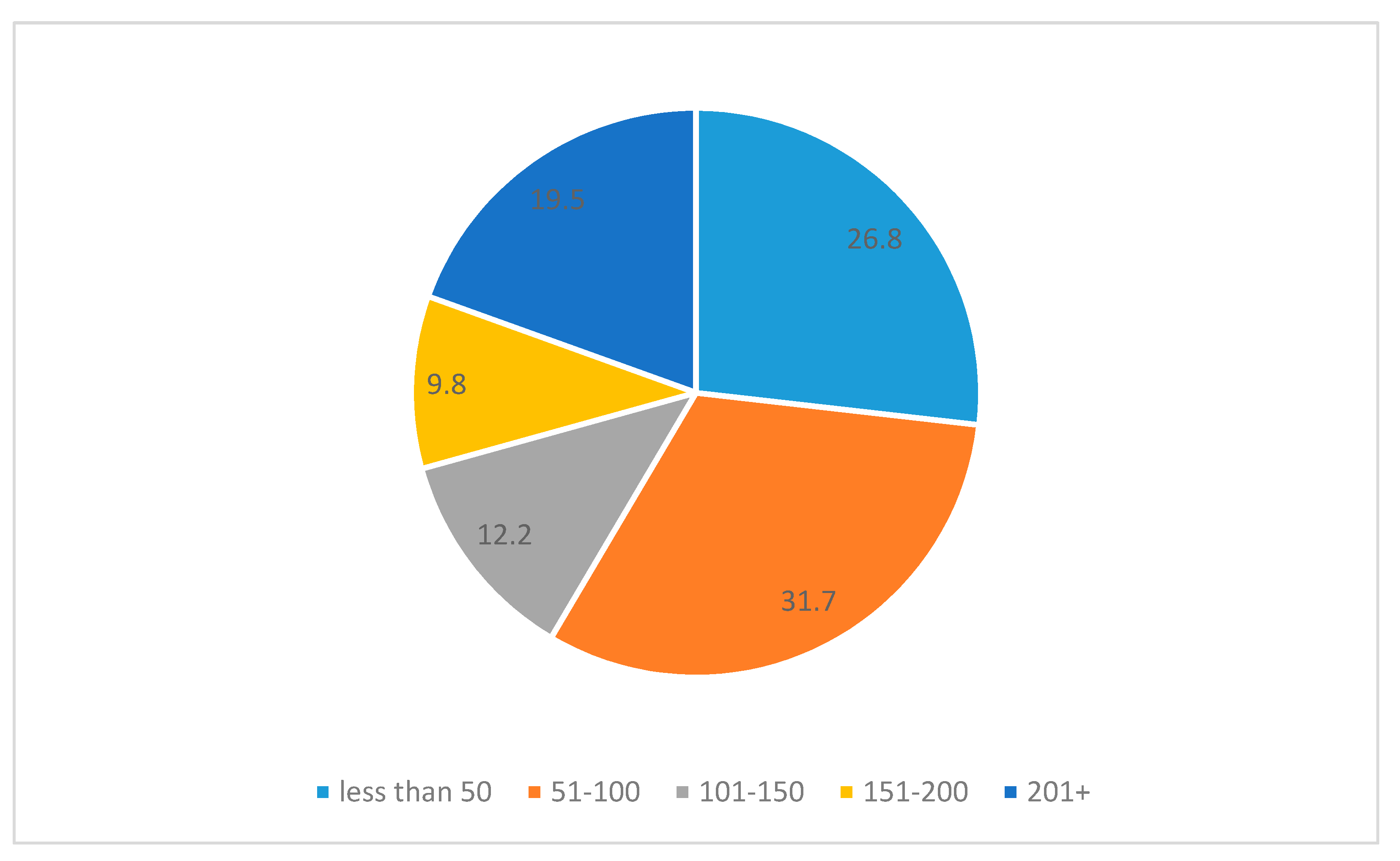

The Czech Republic has the most fragmented administrative structure in Europe. Together 1444 municipalities out of the total of 6253 have fewer than 200 inhabitants [

42]. In Moravia, there is a difference between large villages in the lowlands—often exceeding 2000 or more inhabitants, and small villages in the mountains bordering the main transit route through the Moravian Gate (Hrubý Jeseník Mountains and Bohemian-Moravian Highlands in the west and West Carpathians in the east). The entire settlement system depends on a dense structure of small towns fulfilling the role of centers ensuring jobs, services, social contacts, transport links and micro-regional identity. Everyday life takes place in the functional systems created by small towns and rural settlements in the outlying regions [

43].

The distribution of municipalities with less than 200 inhabitants, some of which are endangered by depopulation, can be seen in

Figure 8. It is clear that these municipalities are concentrated on regional borders (between NUTS 3 regions) and in some parts of the borderland area. The risk of village extinction is associated with a wider process of rural depopulation, which was typical especially for a productive society. The current transition to a post-productive society modifies this process. Nowadays, housing in remote villages is becoming attractive again, so that even the size category of municipalities with less than 200 inhabitants is experiencing a migration increase as a whole. If these municipalities lose population, it is the result of natural decline, which is associated with aging. The number of municipalities with less than 200 inhabitants has a decreasing tendency. There were 1736 such municipalities in the Czech Republic in 2000, while in 2015 there were only 1444. At the same time, the total number of municipalities remains more or less the same. This means that the reason for the fall in the number of very small municipalities is that their population has exceeded the limit of 200 inhabitants and more.

Migration trends and directions have been changing since the mid-1990s. Earlier migration from rural to urban areas, supported by the mass construction of prefabricated housing estates in cities and the administrative capping of construction in so-called settlements without permanent significance, was replaced by bilateral migration, in which migration from cities to rural areas slightly predominates. The targets of this migration are naturally mainly suburbanized villages, but people are also moving to more distant and smaller rural settlements to a lesser extent. On one hand, the main drives are cheaper housing in the more remote countryside—especially for the elderly, and on the other hand, a better and quieter natural environment for young families.

4. Discussion

The risk of village extinction is associated with a wider process of rural depopulation, which was typical especially for a productive society. The current transition to a post-productive society modifies this process. Nowadays, housing in remote villages is becoming attractive again, so that even the size category of municipalities with less than 200 inhabitants is experiencing a positive migration balance as a whole. If these municipalities lose population, it is the result of natural decline, which is associated with aging.

However, it is also necessary to realize that the process of transformation to a post-productive society has a reverse side. There is increased interest in the use of rural settlements for housing and tourism, especially for second homes. While housing tends to be located in rural settlements with basic social infrastructure and with adequate access to larger centers, second homes and tourism can also be found in locations in the remote countryside. Therefore, rather than the extinction of rural municipalities, it is currently possible to assume their transformation from agricultural settlements to residential or recreational settlements. After all, even uninhabited villages after displacement of the German population—if their buildings were not razed to the ground—have been transformed into second-home villages since the 1960s.

One must realize that the basic structure of Central European settlement originated in the 13th century. Since then, individual settlements have been disappearing. The original villages were located so that the farmer would be able to walk to the fields, work and return home within a reasonable time. This means that the villages had to be relatively densely situated. Today’s rural resident, who is motorized and mostly works in the village or town, does not need such a dense network of villages. So, if we are talking about the danger of extinction of villages, we are primarily concerned with their cultural heritage, not their technical and economic substance.

This historical heritage can be preserved without having to preserve the physical structure of villages—especially in a situation where the historical heritage of the countryside disappears under the pressure of suburbanization, counter-urbanization, the introduction of non-original buildings and the urban way of life. The preservation of the genius loci, the landscape memory and the spiritual heritage does not necessarily have to be linked to the preservation of the physical structure of the village [

44]. It can be associated with a certain place in a field—a chapel, a cross, the rest of the settlement, a monument—to which the spiritual heritage may be related.

Larger settlements are more efficient for housing in today’s world and can have a complete range of basic social services and full technical equipment. The smallest settlements are suitable for recreation activities, or for those residents who prefer quiet solitude close to nature. However, these people should be either mobile or reconciled to the fact that they will live in settlements with a very limited infrastructure.