The Case for Long-Term Land Leasing: A Review of the Empirical Literature

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Concept of Land Leasing and Theoretical Background

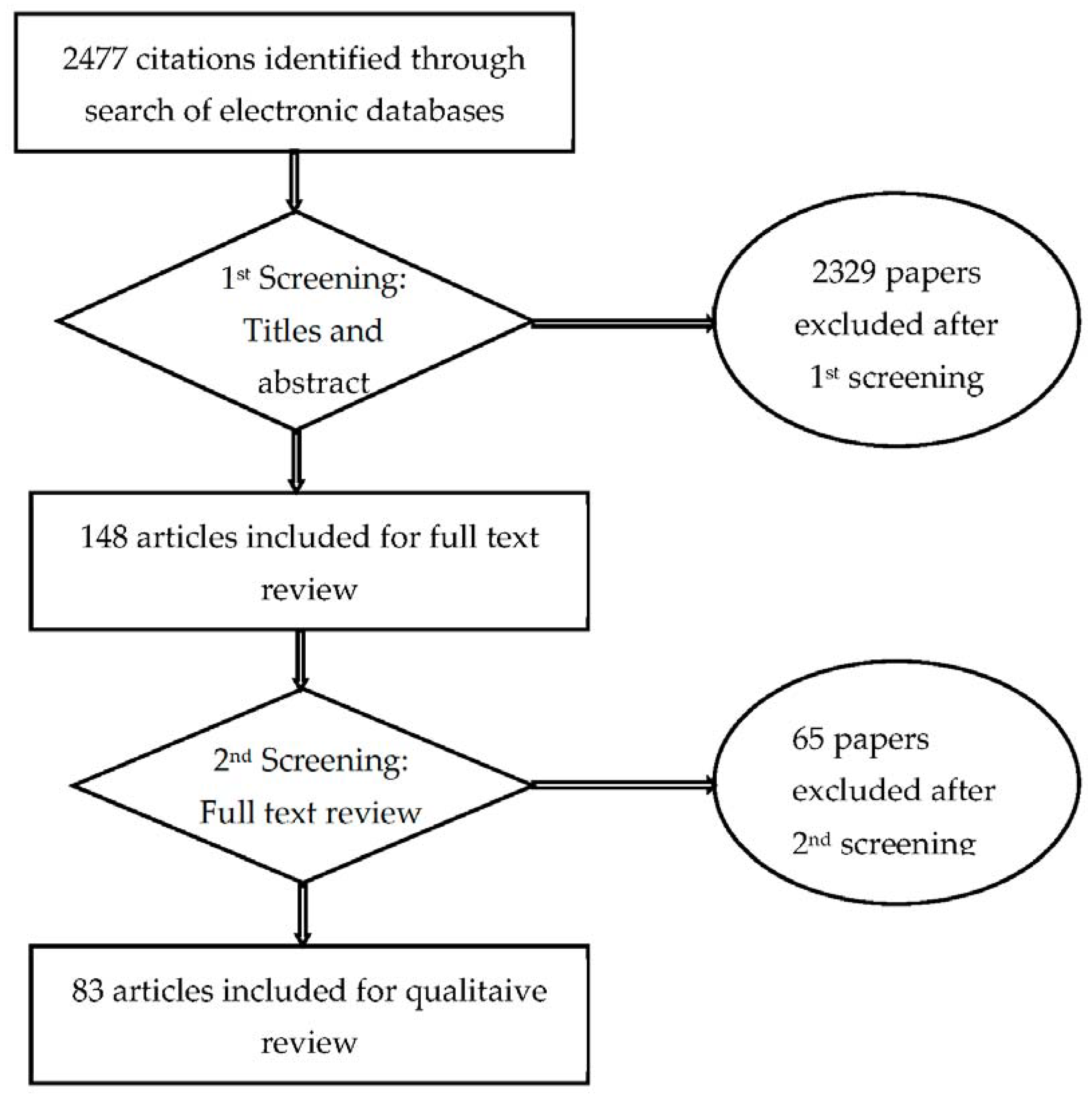

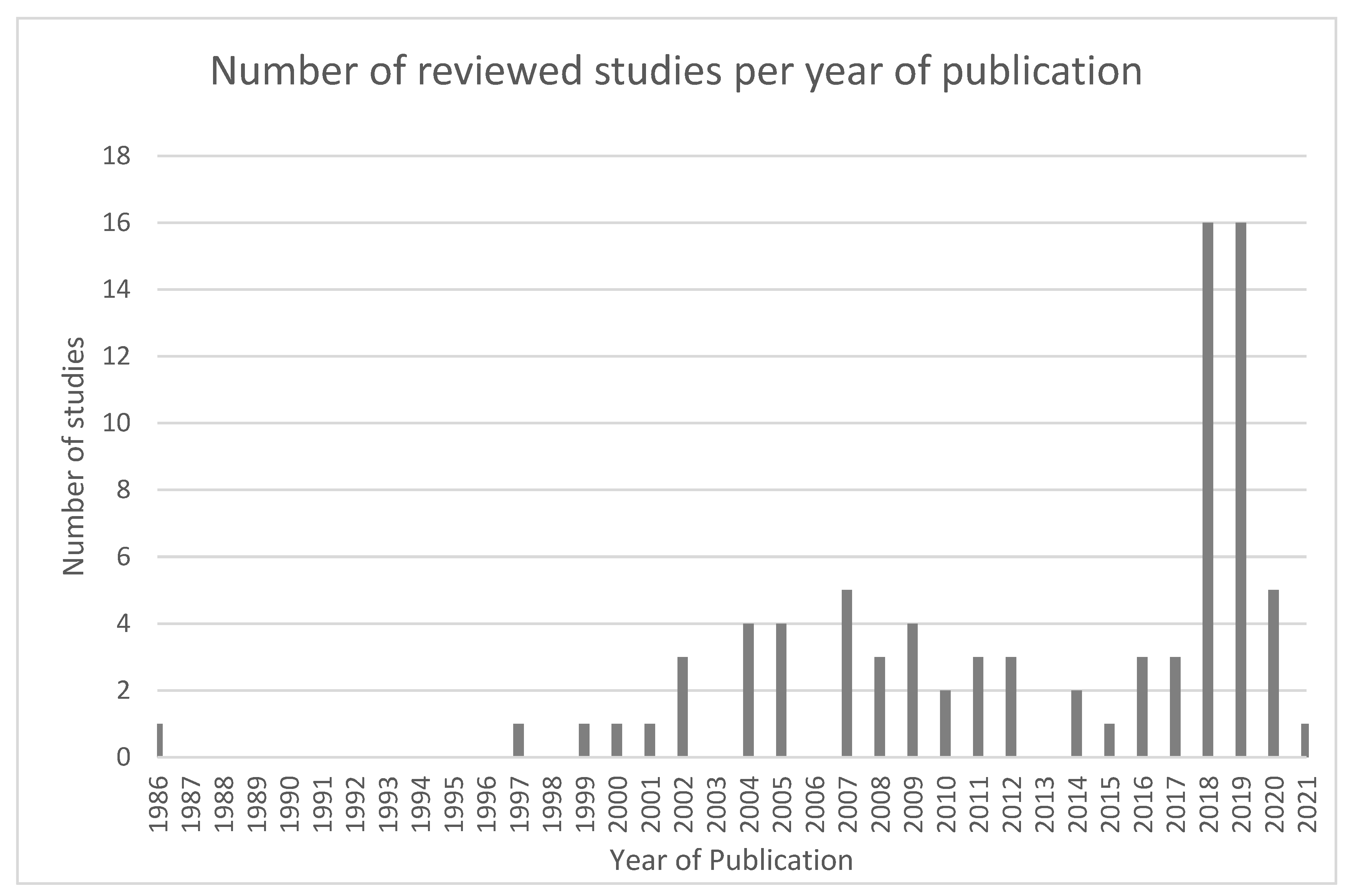

3. Materials and Methods

- Land leasing;

- Land tenure security;

- Land leasing policies;

- Incentives for land leasing;

- Justification for long-term land leasing;

- Encouraging long-term land leasing;

- Barriers to long-term land leasing;

- Land leasing and agricultural productivity;

- Challenges to long-term land leasing.

4. The Case for Long-Term Land Leasing

| Countries | Average UAA/Farm (ha) | Owned UAA, % of Total UAA | Leased UAA, % of Total UAA | Share-Cropping, % of Leased UAA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | 58.7 | 38.3 | 61.7 | 1.5 |

| Germany | 58.6 | 38.7 | 61.4 | 2.6 |

| United Kingdom | 81.41 | 69.4 | 30.6 | - |

| Netherlands | 27.4 | 58.8 | 41.2 | 34.2 |

| Belgium | 34.6 | 32.9 | 67.1 | 1.6 |

| Italy | 12.0 | 64.9 | 35.1 | 16.0 |

| Spain | 24.1 | 61.0 | 39.0 | 18.5 |

| USA | 216 | 60.0 | 38.0 | 34.8 |

| Northern Ireland 1 | 41.2 | 72.2 | 27.8 2 | - |

4.1. Farm Productivity and Profitability

4.2. Farm Investment

4.3. Farm Level Sustainability and Land Management

4.4. Facilitate Structural Change and Encourage New Entrants to Farming

4.5. Access to Credit

4.6. Easy Retirement Decision

5. Challenges to Long-Term Land Leasing

5.1. The Desire to Keep Land in the Family Name

5.2. The Fear of Sudden Change in Policy

5.3. Transaction Costs and Bureaucracy

5.4. Lack of Awareness of Government Policies

6. How to Encourage Long-Term Land Leasing

6.1. Legislation

6.2. Tax Incentives and Subsidies

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| S/N | Reference | Focus of the Study/Title | Country/Sub-Region/Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [79] | Understanding the economics of land access in Ireland | Republic of Ireland |

| 2 | [9] | The factors influencing the profitability of leased land on dairy farms in Ireland | Republic of Ireland |

| 3 | [68] | Increasing the Availability of Farmland for New Entrants to Agriculture in Scotland | Scotland |

| 4 | [80] | Farmland Owners’ Land Sale Preferences: Can They Be Affected by Taxation Programs? | Finland |

| 5 | [22] | Rental Market Regulations for Agricultural Land in EU Member States and Candidate Countries | EU countries |

| 6 | [81] | Landowner response to policies regulating land improvements in Finland: Lease or search for other options? | Finland |

| 7 | [15] | Agri-Taxation | Republic of Ireland |

| 8 | [30] | Keeping agriculture alive next to the city—The functions of the land tenure regime nearby Gothenburg, Sweden | Sweden |

| 9 | [82] | Do Chinese farmers benefit from farmland leasing choices? Evidence from a nationwide survey | China |

| 10 | [5] | Economic and legal differences in patterns of land use in Ukraine | Ukraine |

| 11 | [2] | Farmland tenure and transaction costs: Public and collectively owned land vs conventional coordination mechanisms in France | France |

| 12 | [47] | Changes in property-use relationships on French farmland: A social innovation perspective | France |

| 13 | [83] | EU land markets and the Common Agricultural Policy | EU countries |

| 14 | [51] | Land Leasing: Findings of a Study in the West Region of the Republic of Ireland | Republic of Ireland |

| 15 | [20] | Do farmers care about rented land? A multi-method study on land tenure and soil conservation | Austria |

| 16 | [58] | Land improvements under land tenure insecurity: the case of pH and phosphate in Finland | Finland |

| 17 | [60] | Understanding barriers and opportunities for adoption of conservation practices on rented farmland in the US | US |

| 18 | [16] | Socioeconomic drivers of land mobility in Irish agriculture | Republic of Ireland |

| 19 | [84] | Farm landowners’ objectives in Finland: Two approaches for owner classifications | Finland |

| 20 | [17] | Land lease contracts: properties and the value of bundles of property rights | Netherlands |

| 21 | [85] | Land access for direct market food farmers | US |

| 22 | [69] | Public policy to support young farmers | Thailand |

| 23 | [86] | Political reforms, rural crises, and land tenure i | Western Europe |

| 24 | [87] | Long-term Land Leasing | Republic of Ireland |

| 25 | [72] | Retired Farmers and New Land Users: How Relations to Land and People Influence Farmers’ Land Transfer Decisions | Sweden |

| 26 | [88] | An Economic Evaluation of the Agricultural Tenancies Act 1995 | England |

| 27 | [10] | Impact of Land Use Rights on the Investment and Efficiency of Organic Farming | Pakistan |

| 28 | [52] | Effects of dual land ownerships and different land lease terms on industrial land use efficiency | China |

| 29 | [89] | Exploring long-term land improvements under land tenure insecurity | Finland |

| 30 | [90] | Situational analysis of agricultural land leasing in Uttar Pradesh | Northern India |

| 31 | [91] | Does Land Tenure Systems Affect Sustainable Agricultural Development? | Pakistan |

| 32 | [92] | Leasing of agricultural land versus agency theory: the case of Poland | Poland |

| 33 | [93] | land lease tenure insecurity, productivity and investment | Fiji |

| 34 | [33] | Drivers of change in Norwegian agricultural land control and the emergence of rental farming | Norway |

| 35 | [37] | Contract duration and the division of labor in agricultural land leases | General study |

| 36 | [71] | Characteristics of land market in Hungary at the time of the EU accession | Hungary |

| 37 | [62] | Land tenure and agricultural management: Soil conservation on rented and owned fields | Southwest British Columbia |

| 38 | [63] | Land tenure and the adoption of conservation practices | US |

| 39 | [94] | Do farmers manage weeds on owned and rented land differently? Evidence from US corn and soybean farms | US |

| 40 | [95] | Institutional drivers of land mobility: | Republic of Ireland |

| 41 | [28] | Land leasing and sharecropping in Brazil: Determinants, modus operandi and future perspectives | Brazil |

| 42 | [96] | Land tenure type as an underrated legal constraint on the conservation management of coastal dunes | Republic of Ireland |

| 43 | [97] | Land leasing in rural Ireland | Republic of Ireland |

| 44 | [98] | Investment behavior of the Polish farms | Poland |

| 45 | [78] | Why the uncertain term occurs in the farmland lease market | China |

| 46 | [99] | Encouraging agricultural land lettings in Scotland for the 21st century | Scotland |

| 47 | [100] | A consultation on tenancy reform and call for evidence on farm business repossessions and mortgage restrictions over let land | Wales |

| 48 | [7] | Dynamics and resource use efficiency of agricultural land sales and rental market in India | India |

| 49 | [32] | Arkansas landlord selection of land-leasing contract type and terms | US |

| 50 | [101] | The role of land tenancy in rice farming efficiency | Indonesia |

| 51 | [102] | New entrants and succession into farming | Northern Ireland |

| 52 | [103] | Aging population, farm succession, and farmland usage | China |

| 53 | [104] | The moratorium on agricultural land sale as a limiting factor for rural development | International study |

| 54 | [105] | Effects of land tenure and property rights on agricultural productivity | Ethiopia |

| 55 | [106] | Taxing and untaxing land: Current use assessment of farmland | US |

| 56 | [107] | Land tenure, fixed investment, and farm productivity | Zambia |

| 57 | [29] | On the choice of tenancy contracts in rural India | |

| 58 | [108] | How cropland contract type and term decisions are made | US |

| 59 | [24] | Differentiation of rent for agricultural-purpose land | International study |

| 60 | [109] | Indigenous land tenure reform, self-determination, and economic development | Canada and Australia |

| 61 | [110] | Promotion incentives, infrastructure construction, and industrial landscapes | China |

| 62 | [111] | Passive farming and land development: A real options approach | EU |

| 63 | [112] | Female successors in Irish family farming: four pathways to farm transfer | Republic of Ireland |

| 64 | [113] | Adaptation to climate change via adjustment in land leasing: Evidence from dryland wheat farms in the US Pacific Northwest | US |

| 65 | [114] | The value of social capital in farmland leasing relationships | US |

| 66 | [115] | Impact of land reform on sustainable land management in Ukraine | Ukraine |

| 67 | [116] | Land Grabbing in Europe? Socio-Cultural Externalities of Large-Scale Land Acquisitions | Germany |

| 68 | [74] | Policy Drivers of Land Mobility in Irish Agriculture | Republic of Ireland |

| 69 | [117] | Farmland rent in the European Union | EU |

| 70 | [118] | Land Tenures as Policy Instruments: Transitions | Australia |

| 71 | [119] | Land Tenure Security and Home Maintenance | Japan |

| 72 | [120] | The organization and rise of land and lease markets | EU |

| 73 | [31] | Land market and e-services | Bulgaria |

| 74 | [121] | Land policies and agricultural land markets | Russia |

| 75 | [122] | Farmland lease decisions in a life-cycle model | International study |

| 76 | [61] | Rented land: Barriers to sustainable agriculture | US |

| 77 | [53] | Does land lease tenure insecurity cause decreased productivity and investment in the sugar industry? | Fiji |

| 78 | [123] | Rural land ownership in the United Kingdom: Changing patterns and future possibilities for land use | UK |

| 79 | [66] | Effects of land transfer quality on the application of organic fertiliser by large-scale farmers | China |

| 80 | [38] | Land Tenure, investment incentives, and the choice of techniques | Nicaragua |

| 81 | [61] | Rented land: Barriers to sustainable agriculture | US |

| 82 | [124] | Participation in rural land rental markets in sub-Saharan Africa | Malawi and Zambia |

| 83 | [46] | Retirement farming or sustainable growth—Land transfer choices for farmers without a successor | Republic of Ireland |

References

- Marks-Bielska, R. Factors shaping the agricultural land market in Poland. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léger-Bosch, C. Farmland tenure and transaction costs: Public and collectively owned land vs conventional coordination mechanisms in France. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Rev. Can. D’Agroeconomie 2019, 67, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigier, M.; Kowalski, A. The Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union—The present and the Future. EU Member States Point of View; Instytut Ekonomiki Rolnictwa i Gospodarki Żywnościowej-Państwowy Instytut: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dumanski, J.; Terry, E.; Byerlee, D.; Pieri, C. Performance Indicators for Sustainable Agriculture; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fedchyshyn, D.; Ignatenko, I.; Shvydka, V. Economic and legal differences in patterns of land use in Ukraine. Amazon. Investig. 2019, 8, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.; Deininger, K. Land rental markets in the process of rural structural transformation: Productivity and equity impacts from China. J. Comp. Econ. 2009, 37, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Awasthi, M.K. Dynamics and resource use efficiency of agricultural land sales and rental market in India. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Jin, S.; Nagarajan, H.K. Determinants and Consequences of Land Sales Market Participation: Panel Evidence from India; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bradfield, T.; Butler, R.; Dillon, E.J.; Hennessy, T. The factors influencing the profitability of leased land on dairy farms in Ireland. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.W.; Akram, N.; Hongshu, W.; Andleeb, S.; Kashif, U.; Mehmood, A. Impact of Land Use Rights on the Investment and Efficiency of Organic Farming. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, L.; Sun, D.; Huang, J. Impact of land tenure policy on agricultural investments in China: Evidence from a panel data study. China Econ. Rev. 2017, 45, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D.; Franco, J.C.; Borras, S.M., Jr. Land concentration and land grabbing in Europe: A preliminary analysis. Can. J. Dev. Stud. Rev. Can. D’Études Développement 2015, 36, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zondag, M.-J.; Koppert, S.; de Lauwere, C.; Sloot, P.; Pauer, A. Needs of Young Farmers. Report I of the Pilot Project: Exchange Programmes for Young Farmers; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rounsevell, M.; Reginster, I.; Araújo, M.B.; Carter, T.; Dendoncker, N.; Ewert, F.; House, J.; Kankaanpää, S.; Leemans, R.; Metzger, M. A coherent set of future land use change scenarios for Europe. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 114, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine(DAFM). Agri-Taxation Review-Part A Working Group Report; Department of Agriculture Food and the Marine, Ed.; Department of Agriculture Food and the Marine: Dublin, Ireland, 2014.

- Geoghegan, C.; O’Donoghue, C. Socioeconomic drivers of land mobility in Irish agriculture. Int. J. Agric. Manag. 2018, 7, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Slangen, L.H.; Polman, N.B. Land lease contracts: Properties and the value of bundles of property rights. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2008, 55, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bromley, D.W. Environment and Economy: Property Rights and Public Policy; Basil Blackwell Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Von Benda-Beckmann, F.; von Benda-Beckmann, K.; Wiber, M. Changing Properties of Property; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt, H.; Penker, M.; Salhofer, K. Do farmers care about rented land? A multi-method study on land tenure and soil conservation. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dramstad, W.E.; Sang, N. Tenancy in Norwegian agriculture. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 946–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaian, P.; Kancs, d.A.; Swinnen, J.; Van Herck, K.; Vranken, L. Rental Market Regulations for Agricultural Land in EU Member States and Candidate Countries. Factor Markets Working Paper No. 15, February 2012; Archive of European Integration: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson, C.; Morehart, M.; Kuethe, T.; Beckman, J.; Ifft, J.; Williams, R. Trends in US Farmland Values and Ownership; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2012.

- Zavorotin, E.; Gordopolova, A.; Tiurina, N.; Pototskaya, L. Differentiation of rent for agricultural-purpose land. Sci. Pap. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2019, 19, 691–698. [Google Scholar]

- Loughrey, J.; Donnellan, T.; Hanrahan, K. The Agricultural Land Market in the EU and the Case for Better Data Provision. EuroChoices 2020, 19, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, T.W. The Economics of Leasing. J. Legal Anal. 2020, 12, 221–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuberger, D.; Räthke-Döppner, S. Leasing by small enterprises. Appl. Financ. Econ. 2013, 23, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Almeida, P.J.; Buainain, A.M. Land leasing and sharecropping in Brazil: Determinants, modus operandi and future perspectives. Land Use Policy 2016, 52, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Maitra, P. On the choice of tenancy contracts in rural India. Economica 2002, 69, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastfelt, A.; Zhang, Q. Keeping agriculture alive next to the city - The functions of the land tenure regime nearby Gothenburg, Sweden. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyneva, D. Land market and e-services in Bulgaria. Agric. Econ. Zemed. Ekon. 2007, 53, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rainey, R.L.; Dixon, B.L.; Ahrendsen, B.L.; Parsch, L.D.; Bierlen, R.W. Arkansas landlord selection of land-leasing contract type and terms. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2005, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Forbord, M.; Bjørkhaug, H.; Burton, R.J. Drivers of change in Norwegian agricultural land control and the emergence of rental farming. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 33, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serra, T.; Goodwin, B.K.; Featherstone, A.M. Agricultural policy reform and off-farm labour decisions. J. Agric. Econ. 2005, 56, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallas, Z.; Serra, T.; Gil, J.M. Effects of policy instruments on farm investments and production decisions in the Spanish COP sector. Appl. Econ. 2012, 44, 3877–3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.N. Transaction costs, risk aversion, and the choice of contractual arrangements. In Uncertainty in Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1978; pp. 377–399. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder, J.; Hossain, I.; Epplin, F.; Doye, D. Contract duration and the division of labor in agricultural land leases. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2008, 65, 714–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bandiera, O. Land Tenure, Investment Incentives, and the Choice of Techniques: Evidence from Nicaragua. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2007, 21, 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenuga, A.H.; Jack, C.; Olagunju, K.O.; Ashfield, A. Economic viability of adoption of automated oestrus detection technologies on dairy farms: A review. Animals 2020, 10, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singirankabo, U.A.; Ertsen, M.W. Relations between Land Tenure Security and Agricultural Productivity: Exploring the Effect of Land Registration. Land 2020, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrachuk, M.; Marschke, M.; Hings, C.; Armitage, D. Smartphone technologies supporting community-based environmental monitoring and implementation: A systematic scoping review. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 237, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EndNote Team. EndNote, EndNote X9; Clarivate Analytics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013.

- QSR International. Nvivo (Released in March 2020), 12; QSR International: Burlington, MA, USA, 2020.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baker, M.; Miceli, T.J. Land inheritance rules: Theory and cross-cultural analysis. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2005, 56, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duesberg, S.; Bogue, P.; Renwick, A. Retirement farming or sustainable growth—Land transfer choices for farmers without a successor. Land Use Policy 2017, 61, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léger-Bosch, C.; Houdart, M.; Loudiyi, S.; Le Bel, P.-M. Changes in property-use relationships on French farmland: A social innovation perspective. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs(DAERA). Statistical Review of Northern Ireland Agriculture, Policy, Economics and Statistics Division; Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs: Belfast, UK, 2020.

- The Agriculture and Food Development Authority. Guidelines for Long-term Land Leasing; Teagasc: Carlow, Ireland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Adenuga, A.H.; Davis, J.; Hutchinson, G.; Donnellan, T.; Patton, M. Modelling regional environmental efficiency differentials of dairy farms on the island of Ireland. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 95, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, A. Land Leasing: Findings of a Study in the West Region of the Republic of Ireland. Ir. J. Agric. Econ. Rural Sociol. 1986, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Huang, X.; Yang, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhong, T.; Xie, Z. Effects of dual land ownerships and different land lease terms on industrial land use efficiency in Wuxi City, East China. Habitat Int. 2018, 78, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Nakano, Y. Does land lease tenure insecurity cause decreased productivity and investment in the sugar industry? Evidence from Fiji. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2016, 60, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galiani, S.; Schargrodsky, E. Property rights for the poor: Effects of land titling. J. Public Econ. 2010, 94, 700–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Besley, T. Property rights and investment incentives: Theory and evidence from Ghana. J. Political Econ. 1995, 103, 903–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Place, F. Land Tenure and Agricultural Productivity in Africa: A Comparative Analysis of the Economics Literature and Recent Policy Strategies and Reforms. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1326–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K. Land markets in developing and transition economies: Impact of liberalization and implications for future reform. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2003, 85, 1217–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myyrä, S.; Ketoja, E.; Yli-Halla, M.; Pietola, K. Land improvements under land tenure insecurity: The case of pH and phosphate in Finland. Land Econ. 2005, 81, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deininger, K.; Jin, S. Tenure security and land-related investment: Evidence from Ethiopia. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2006, 50, 1245–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ranjan, P.; Wardropper, C.B.; Eanes, F.R.; Reddy, S.M.; Harden, S.C.; Masuda, Y.J.; Prokopy, L.S. Understanding barriers and opportunities for adoption of conservation practices on rented farmland in the US. Land Use Policy 2019, 80, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M.; Mayerfeld, D.; Bell, M.; Exner, R. Rented land: Barriers to sustainable agriculture. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2004, 59, 70A–75A. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, E.D.G. Land tenure and agricultural management: Soil conservation on rented and owned fields in southwest British Columbia. Agric. Human Values 2004, 21, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soule, M.J.; Tegene, A.; Wiebe, K.D. Land tenure and the adoption of conservation practices. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2000, 82, 993–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayamga, M.; Yeboah, R.W.N.; Ayambila, S.N. An analysis of household farm investment decisions under varying land tenure arrangements in Ghana. J. Agric. Rural Dev. Trop. Subtrop. (JARTS) 2016, 117, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kousar, R.; Abdulai, A. Off-farm work, land tenancy contracts and investment in soil conservation measures in rural Pakistan. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2016, 60, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.W.; Shen, Y.Q. Effects of land transfer quality on the application of organic fertilizer by large-scale farmers in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenuga, A.H.; Davis, J.; Hutchinson, G.; Patton, M.; Donnellan, T. Analysis of the effect of alternative agri-environmental policy instruments on production performance and nitrogen surplus of representative dairy farms. Agric. Syst. 2020, 184, 102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, A.; Sutherland, L.; Hopkins, J.; Flanigan, S.; Rickett, A. Increasing the availability of farmland for new entrants to agriculture in Scotland. In Final Report to the Scottish Land Commission; James Hutton Institute and Fresh Start Land Enterprise Centre: Aberdeen, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Faysse, N.; Phiboon, K.; Filloux, T. Public policy to support young farmers in Thailand. Outlook Agric. 2019, 48, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinnen, J.F.; Swinnen, J.; Vranken, L. Land & EU Accession: Review of the Transitional Restrictions on New Member States on the Acquisition of Agricultural Real Estate; CEPS: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hamza, E.; Misko, K. Characteristics of land market in Hungary at the time of the EU accession. Zemed. Ekon. Praha 2007, 53, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grubbstrom, A.; Eriksson, C. Retired Farmers and New Land Users: How Relations to Land and People Influence Farmers’ Land Transfer Decisions. Sociol. Rural. 2018, 58, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.; Adenuga, A.H.; Ashfield, A.; Wallace, M. Investigating the Drivers of Farmers’ Engagement in a Participatory Extension Programme: The Case of Northern Ireland Business Development Groups. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, C.; Kinsella, A.; O’Donoghue, C. Policy Drivers of Land Mobility in Irish Agriculture. In Proceedings of the European Association of Agricultural Economists (EAAE) > 150th Seminar, Edinburgh, UK, 22–23 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fakayode, S.B.; Adenuga, A.H.; Yusuf, T.; Jegede, O. Awareness of and demand for private agricultural extension services among small-scale farmers in Nigeria. J. Agribus. Rural Dev. 2016, 4, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AEIAR. Status of Agricultural Land Market Regulation in Europe: Policies and Instruments; Association Européenne des Institutions D’Aménagement Rural: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Holthuis, J.; ter Burg, P. Agricultural Law in The Netherlands: Overview. 2020. Available online: https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/1-603-8746?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)&firstPage=true (accessed on 19 December 2020).

- Zou, B.; Luo, B. Why the uncertain term occurs in the farmland lease market: Evidence from rural China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geoghegan, C. Understanding the Economics of Land Access in Ireland; NUI: Galway, Ireland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Myyrä, S.; Pouta, E. Farmland owners’ land sale preferences: Can they be affected by taxation programs? Land Econ. 2010, 86, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouta, E.; Myyrä, S.; Pietola, K. Landowner response to policies regulating land improvements in Finland: Lease or search for other options? Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, B.L.; Mishra, A.K.; Luo, B.L. Do Chinese farmers benefit from farmland leasing choices? Evidence from a nationwide survey. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2020, 64, 322–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaian, P.; Kancs, d.A.; Swinnen, J.F. EU Land Markets and the Common Agricultural Policy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pouta, E.; Myyrä, S.; Hänninen, H. Farm landowners’ objectives in Finland: Two approaches for owner classifications. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2011, 24, 1042–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horst, M.; Gwin, L. Land access for direct market food farmers in Oregon, USA. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 594–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinnen, J.F. Political reforms, rural crises, and land tenure in western Europe. Food Policy 2002, 27, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, T. Registering a Farm Partnership—The Requirements. In Proceedings of the Teagasc Farm Business Conference, Tullamore, Ireland, 26 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, I.; Errington, A.; Millard, N. An Economic Evaluation of the Agricultural Tenancies Act 1995—A Baseline Study; Department Land Use Rural Management, University of Plymouth: Plymouth, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Myyra, S.; Pietola, K.; Yli-Halla, M. Exploring long-term land improvements under land tenure insecurity. Agric. Syst. 2007, 92, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mandal, S.; Misra, G.V.; Naqvi, S.M.A.; Kumar, N. Situational analysis of agricultural land leasing in Uttar Pradesh. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, N.; Akram, M.W.; Wang, H.; Mehmood, A. Does Land Tenure Systems Affect Sustainable Agricultural Development? Sustainability 2019, 11, 3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marks-Bielska, R.; Zielinska, A. Leasing of agricultural land versus agency theory: The case of Poland. Ekon. Prawo 2018, 17, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M.Y.; Saleem, I.; Dwivedi, A.K.; Khan, A. Determinants of agricultural entrepreneurship: A GEM data based study. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 345–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvold, G.B.; Albright, J.; Ervin, D.E.; Owen, M.D.; Norsworthy, J.K.; Dentzman, K.E.; Hurley, T.M.; Jussaume, R.A.; Gunsolus, J.L.; Everman, W. Do farmers manage weeds on owned and rented land differently? Evidence from US corn and soybean farms. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 2030–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, C.; Kinsella, A.; O’Donoghue, C. Institutional drivers of land mobility: The impact of CAP rules and tax policy on land mobility incentives in Ireland. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2017, 77, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, J.; MacLeod, M.; Cooper, A.; O’Hagan, A.M.; Power, J. Land tenure type as an underrated legal constraint on the conservation management of coastal dunes: Examples from Ireland. Area 2005, 37, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, W. Land leasing in rural Ireland-some empirical findings from the south-east. Ir. Geogr. 1997, 30, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieliczko, B.; Kurdys-Kujawska, A.; Sompolska-Rzechula, A. Investment behavior of the Polish farms–is there any evidence for the necessity of policy changes? J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2019, 20, 1292–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, J. Encouraging Agricultural Land Lettings in Scotland for the 21st Century; Scotish Land Commission: Inverness, UK, 2018; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh Government. A Consultation on Tenancy Reform and Call for Evidence on Farm Business Repossessions and Mortgage Restrictions over Let Land; Welsh Government: Cardiff, UK, 2012.

- Khotimah, Y.; Antriyandarti, E.; Supardi, S. The role of land tenancy in rice farming efficiency in upland karst mountainous gunungkidul indonesia. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 14347–14357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.; Miller, A.C.; Ashfield, A.; Anderson, D. New entrants and succession into farming: A Northern Ireland perspective. Int. J. Agric. Manag. 2019, 8, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, B.L.; Mishra, A.K.; Luo, B.L. Aging population, farm succession, and farmland usage: Evidence from rural China. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danylenko, A.; Sokolska, T.; Shust, O.; Wigier, M.; Kowalski, A. The Moratorium on Agricultural Land Sale as a Limiting Factor for Rural Development. In The Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union—The Present and the Future, Non-EU Member States Point of View; Wigier, M., Kowalski, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Tenaw, S.; Zahidul Islam, K.M.; Parviainen, T. Effects of Land Tenure and Property Rights on Agricultural Productivity in Ethiopia, Namibia and Bangladesh; University of Helsinki: Helsinki, Finland, 2009; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Youngman, J.M. Taxing and untaxing land: Current use assessment of farmland. State Tax Notes 2005, 37, 727–738. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.E. Land tenure, fixed investment, and farm productivity: Evidence from Zambia’s southern province. World Dev. 2004, 32, 1641–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierlen, R.; Parsch, L.; Dixon, B. How cropland contract type and term decisions are made: Evidence from an Arkansas Tenant Survey. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 1999, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrill, L.; Boutilier, S. Indigenous land tenure reform, self-determination, and economic development: Comparing Canada and Australia. Univ. West. Aust. Law Rev. 2019, 45, 34–70. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q.S.; Xu, M.; Xu, Z.K.; Ye, Y.M.; Shu, X.F.; Xie, P.; Wu, J.Y. Promotion incentives, infrastructure construction, and industrial landscapes in China. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Corato, L.; Brady, M.V. Passive farming and land development: A real options approach. Land Use Policy 2019, 80, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, A. Female successors in Irish family farming: Four pathways to farm transfer. Can. J. Dev. Stud. Rev. Can. D’Études Développement 2019, 40, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.L.; Mu, J.E.; McCarl, B.A. Adaptation to climate change via adjustment in land leasing: Evidence from dryland wheat farms in the US Pacific Northwest. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, M.R.; Featherstone, A.M. The value of social capital in farmland leasing relationships. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2018, 78, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuryltsiv, R.; Hernik, J.; Kryshenyk, N. Impact of land reform on sustainable land management in Ukraine. Acta Sci. Pol. Form. Circumiectus 2018, 17, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunkus, R.; Theesfeld, I. Land Grabbing in Europe? Socio-Cultural Externalities of Large-Scale Land Acquisitions in East Germany. Land 2018, 7, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Střeleček, F.; Lososová, J.; Zdeněk, R. Farm land rent in the European Union. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2011, 59, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holmes, J. Land Tenures as Policy Instruments: Transitions on Cape York Peninsula. Geogr. Res. 2011, 49, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, S.; Yamaga, H. Land Tenure Security and Home Maintenance: Evidence from Japan. Land Econ. 2009, 85, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Bavel, B.J.P. The organization and rise of land and lease markets in northwestern Europe and Italy, c.1000–1800. Contin. Chang. 2008, 23, 13–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, Z.; Shagaida, N. Land policies and agricultural land markets in Russia. Land Use Policy 2007, 24, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumtje, P.I.; Barry, P.J.; Ellinger, P.N. Farmland lease decisions in a life-cycle model. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2001, 61, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munton, R. Rural land ownership in the United Kingdom: Changing patterns and future possibilities for land use. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, S54–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlin, J.; Ricker-Gilbert, J. Participation in Rural Land Rental Markets in Sub-Saharan Africa: Who Benefits and by How Much? Evidence from Malawi and Zambia. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 98, aaw021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Country | Minimum Term Length (yrs.) | Automatic Lease Renewal | Pre-Emptive Right to Buy | Transferability of Lease to Family Members |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| France | 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Netherlands | 12 years for farms and homesteads; 6 years for separate land or buildings | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Scotland | new tenancies under the 2003 Act, LDT has a min. term of either 10 years (if created after 22 March 2011) or 15 years, if created before | Yes | No, after 2003 | Yes, under the 2003 Act |

| Sweden | whole-farm lease for 5 years | Yes | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adenuga, A.H.; Jack, C.; McCarry, R. The Case for Long-Term Land Leasing: A Review of the Empirical Literature. Land 2021, 10, 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10030238

Adenuga AH, Jack C, McCarry R. The Case for Long-Term Land Leasing: A Review of the Empirical Literature. Land. 2021; 10(3):238. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10030238

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdenuga, Adewale Henry, Claire Jack, and Ronan McCarry. 2021. "The Case for Long-Term Land Leasing: A Review of the Empirical Literature" Land 10, no. 3: 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10030238