Combining Tree Species Composition and Understory Coverage Indicators with Optimization Techniques to Address Concerns with Landscape-Level Biodiversity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

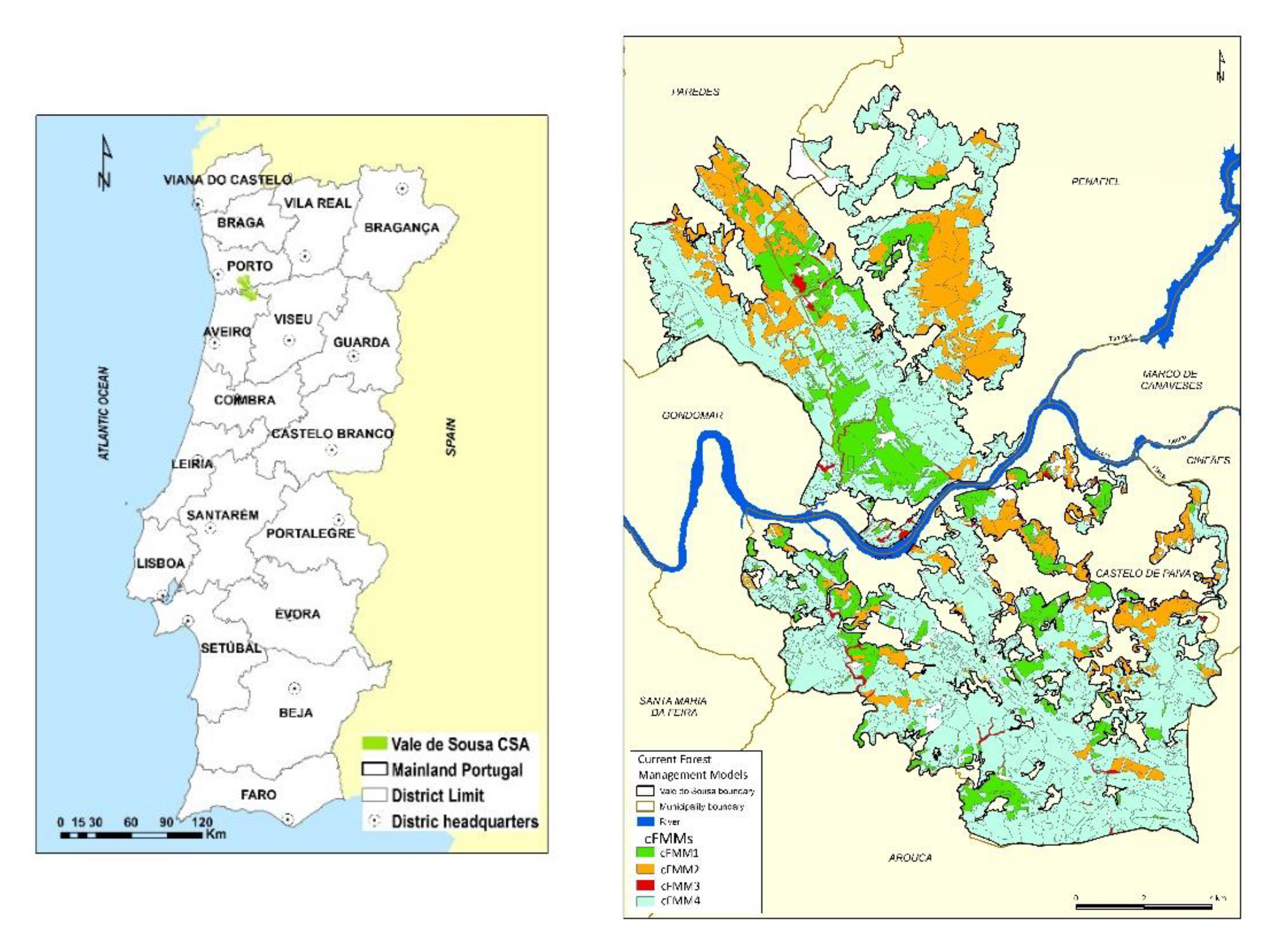

2.1. The Vale de Sousa Forested Landscape. Stand-Level Forest Management Models

- (1)

- A specific growth model to estimate forest growth dynamics under divergent climate conditions have been applied.

- (2)

- The potential biodiversity benefits as a proxy indicator for eight FMMs at stand-level and five fuel treatments (no fuel treatment, annually fuel treatment, each 5-years, and 10 and 15-years) has been computed.

- (3)

- A landscape-level LP-RMC was extended to integrate a biodiversity-oriented forest management indicator taking into account wood provisioning and wildfires reduction, and two local climate scenarios, namely, Business as usual (BAU) and REF (high climate forcing with a RCP 8.5) to evaluate how the essential increase in biodiversity supply can be accomplished through alternative forest models.

2.2. Climate Change Scenarios

2.3. Forest Growth Simulations

2.4. Biodiversity Management-Oriented Indicators

2.5. Forest Management Optimization under Biodiversity Conservation

- (i)

- analyzing the provision of biodiversity values under conflicting ES demand scenarios such as timber production and fire resistance, at landscape-level;

- (ii)

- evaluating the impact of site-specific climate change in long-term decisions (90-years);

- (iii)

- evaluating the impacts of alternative forest management models for biodiversity provisions

2.6. LP-RCM Mathematical Formulation

3. Results

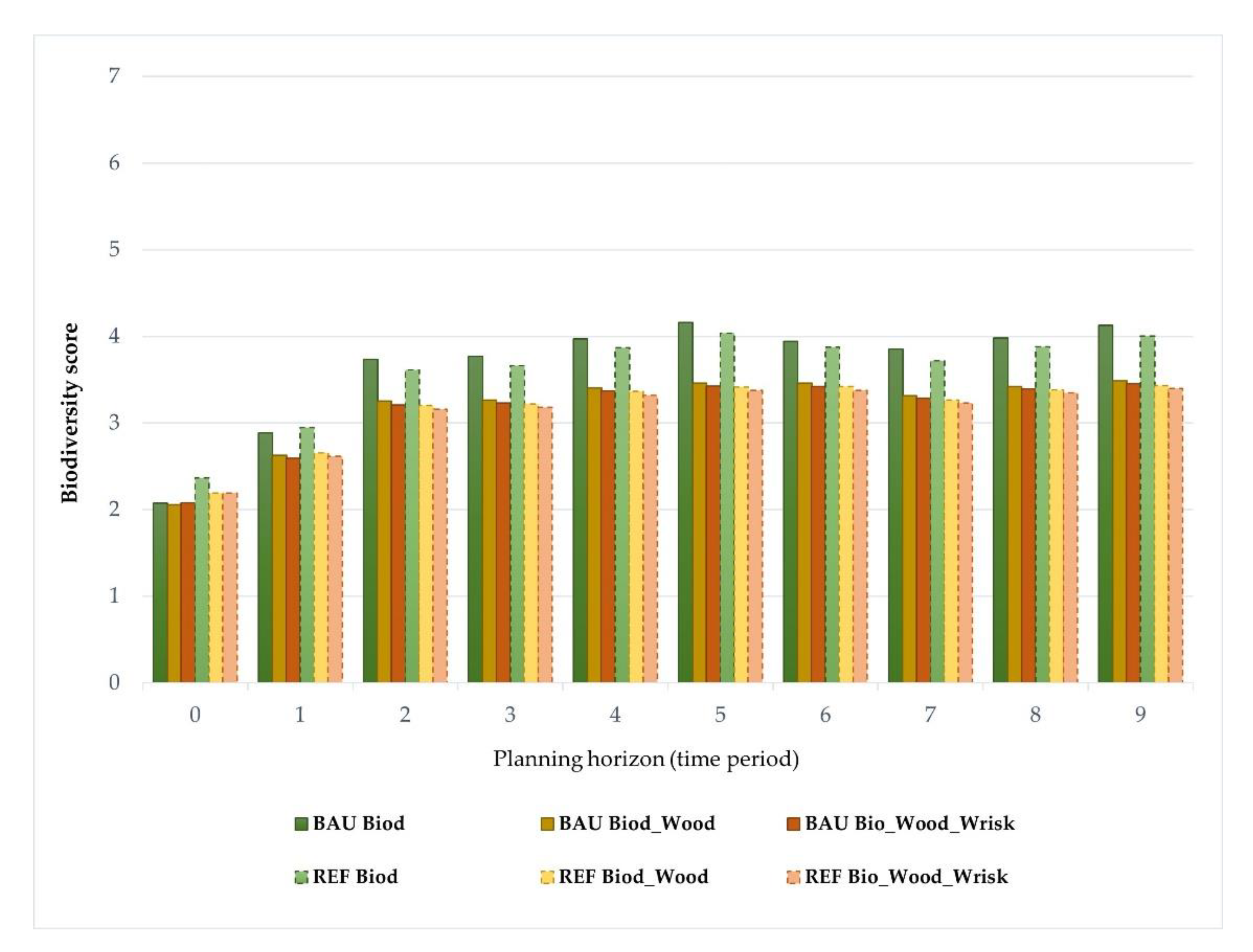

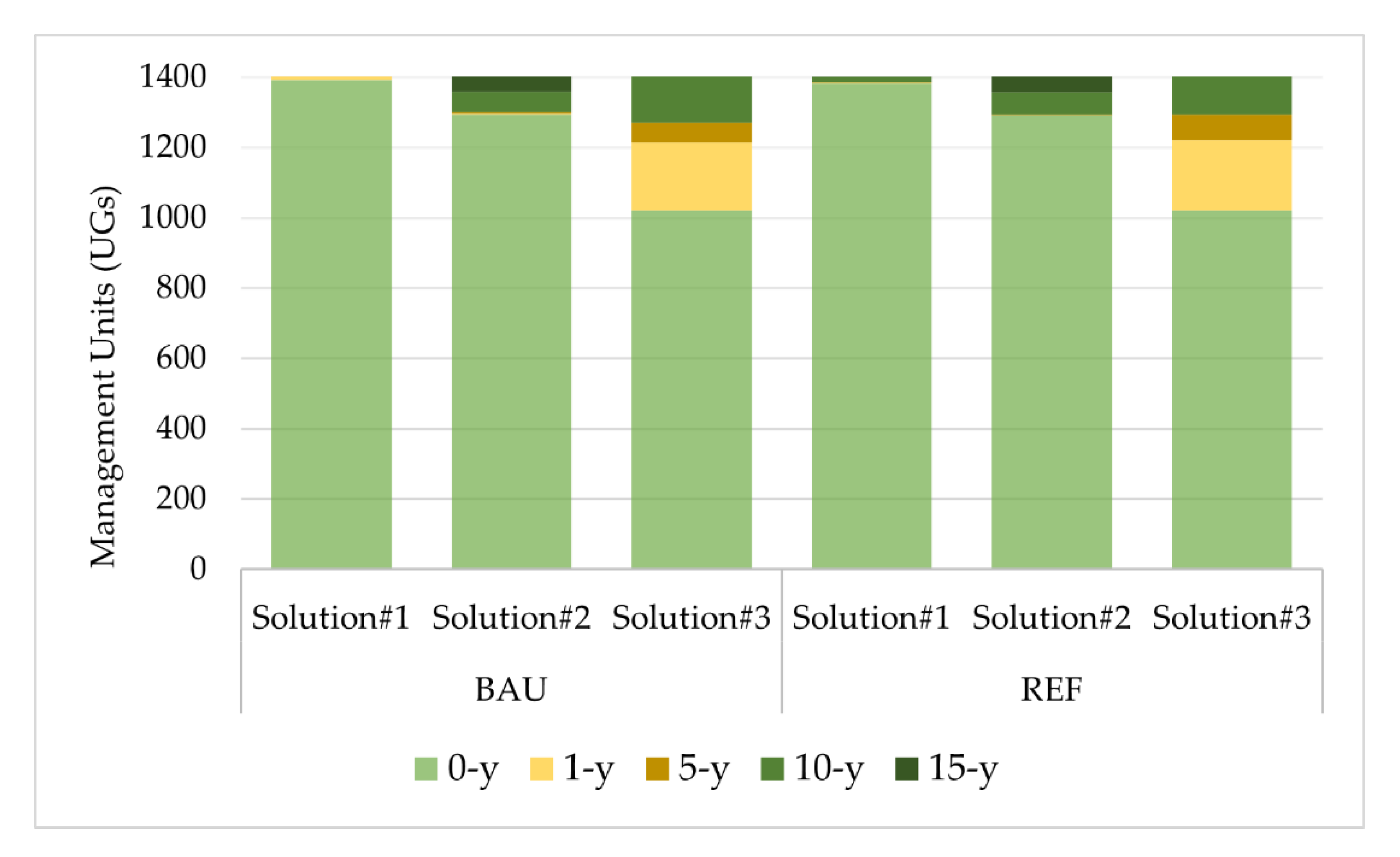

Impacts of Landscape-Level FMM on the Provision Of Biodiversity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Tree Species Composition

| #1. Species Proportion | Description | Scores |

|---|---|---|

| FMM1—Maritime pine dominant | Differentiation between tree species of higher or lower importance for biodiversity. | The mixed stands of maritime pine and eucalypts biodiversity range from 1 to 3 according to the dominance of eucalypt and pine, respectively |

| #1. Species Proportion | Description | Scores |

|---|---|---|

| FMM2—Eucalypt dominant | Differentiation between tree species of higher or lower importance for biodiversity. | The mixed stands of maritime pine and eucalypts biodiversity range from 1 to 3 according to the dominance of eucalypt and pine, respectively. |

| #1. Species Proportion | Description | Scores |

|---|---|---|

| FMM3—Chestnut | Differentiation between tree species of higher or lower importance for biodiversity. | Chestnut is associated to a biodiversity maximum partial score = 4 |

| #1. Species Proportion | Description | Scores |

|---|---|---|

| FMM4—Eucalypt | Differentiation between tree species of higher or lower importance for biodiversity. | Eucalypt pure stands are associated to a maximum partial score = 2 |

| #1. Species Proportion | Description | Scores |

|---|---|---|

| FMM5—Pure maritime pine | Differentiation between tree species of higher or lower importance for biodiversity. | Maritime pure stands are associated to a maximum partial score = 3 |

| #1. Species Proportion | Description | Scores |

|---|---|---|

| FMM6—Pedunculate oak | Differentiation between tree species of higher or lower importance for biodiversity. | Pedunculate oak stands are associated to a maximum partial score = 5 |

| #1. Species Proportion | Description | Scores |

|---|---|---|

| FMM7—Cork oak | Differentiation between tree species of higher or lower importance for biodiversity. | Cork oak stands are associated to a maximum partial score = 5 |

| #1. Species Proportion | Description | Scores |

|---|---|---|

| FMM8—Riparian Systems | Differentiation between tree species of higher or lower importance for biodiversity. | Riparian stands are associated to a maximum partial score = 6 |

Appendix A.2. Understory Vegetation

| #2. Shrub Cover | Description | Scores |

|---|---|---|

| FMM1—Maritime pine dominant FMM2—Eucalypt dominant FMM3—Chestnut FMM4—Pure Eucalypt FMM5—Pure maritime pine FMM6—Pedunculate oak FMM7—Cork oak FMM8—Riparian system | The corresponding “biomass” indicator was measured by Botequim et al., 2015 | The shrub cover of FMMs 1 to 7 ranges between “0” and “1” |

Appendix A.3. Total Biodiversity Score (Example)

References

- Cardinale, B.J.; Duffy, J.E.; Gonzalez, A.; Hooper, D.U.; Perrings, C.; Venail, P.; Narwani, A.; Mace, G.M.; Tilman, D.; Wardle, D.A.; et al. Biodiversity Loss and Its Impact on Humanity. Nature 2012, 486, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretzsch, H.; Knoke, T. Forest management planning in mixed-species forests. In Mixed-Species Forests. Ecology and Management; Pretzsch, H., Forrester, D.I., Bauhus, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 503–544. ISBN 978-3-662-54553-9. [Google Scholar]

- Parrot, L.; Kange, H. An introduction to complexity science. In Managing Forests as Complexity Adaptatiove Systems; Messier, C., Puettmann, K.J., Coates, D., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 17–32. ISBN 978-1-138-77969-3. [Google Scholar]

- Eyvindson, K.; Repo, A.; Mönkkönen, M. Mitigating Forest Biodiversity and Ecosystem Service Losses in the Era of Bio-Based Economy. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 92, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.B.; Margules, C.R.; Botkin, D.B. Indicators of Biodiversity for Ecologically Sustainable Forest Management. Conserv. Biol. 2000, 14, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balvanera, P.; Pfisterer, A.B.; Buchmann, N.; He, J.-S.; Nakashizuka, T.; Raffaelli, D.; Schmid, B. Quantifying the Evidence for Biodiversity Effects on Ecosystem Functioning and Services: Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning/Services. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 1146–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Fargione, J.; Chapin, F.S.; Tilman, D. Biodiversity Loss Threatens Human Well-Being. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, A.; Messier, C. The Effect of Biodiversity on Tree Productivity: From Temperate to Boreal Forests: The Effect of Biodiversity on the Productivity. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011, 20, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Reich, P.B.; Isbell, F. Biodiversity Impacts Ecosystem Productivity as Much as Resources, Disturbance, or Herbivory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 10394–10397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, F.; Craven, D.; Connolly, J.; Loreau, M.; Schmid, B.; Beierkuhnlein, C.; Bezemer, T.M.; Bonin, C.; Bruelheide, H.; de Luca, E.; et al. Biodiversity Increases the Resistance of Ecosystem Productivity to Climate Extremes. Nature 2015, 526, 574–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefcheck, J.S.; Byrnes, J.E.K.; Isbell, F.; Gamfeldt, L.; Griffin, J.N.; Eisenhauer, N.; Hensel, M.J.S.; Hector, A.; Cardinale, B.J.; Duffy, J.E. Biodiversity Enhances Ecosystem Multifunctionality across Trophic Levels and Habitats. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamfeldt, L.; Snäll, T.; Bagchi, R.; Jonsson, M.; Gustafsson, L.; Kjellander, P.; Ruiz-Jaen, M.C.; Fröberg, M.; Stendahl, J.; Philipson, C.D.; et al. Higher Levels of Multiple Ecosystem Services Are Found in Forests with More Tree Species. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Crowther, T.W.; Picard, N.; Wiser, S.; Zhou, M.; Alberti, G.; Schulze, E.-D.; McGuire, A.D.; Bozzato, F.; Pretzsch, H.; et al. Positive Biodiversity-Productivity Relationship Predominant in Global Forests. Science 2016, 354, aaf8957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratcliffe, S.; Wirth, C.; Jucker, T.; van der Plas, F.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M.; Verheyen, K.; Allan, E.; Benavides, R.; Bruelheide, H.; Ohse, B.; et al. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning Relations in European Forests Depend on Environmental Context. Ecol. Lett. 2017, 20, 1414–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butchart, S.H.M.; Walpole, M.; Collen, B.; van Strien, A.; Scharlemann, J.P.W.; Almond, R.E.A.; Baillie, J.E.M.; Bomhard, B.; Brown, C.; Bruno, J.; et al. Global Biodiversity: Indicators of Recent Declines. Science 2010, 328, 1164–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, M.; Fitzgerald, J.B.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Reyer, C.; Delzon, S.; van der Maaten, E.; Schelhaas, M.-J.; Lasch, P.; Eggers, J.; van der Maaten-Theunissen, M.; et al. Climate Change and European Forests: What Do We Know, What Are the Uncertainties, and What Are the Implications for Forest Management? J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 146, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidl, R.; Thom, D.; Kautz, M.; Martin-Benito, D.; Peltoniemi, M.; Vacchiano, G.; Wild, J.; Ascoli, D.; Petr, M.; Honkaniemi, J.; et al. Forest Disturbances under Climate Change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2017, 7, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskent, E.Z. Exploring the Effects of Climate Change Mitigation Scenarios on Timber, Water, Biodiversity and Carbon Values: A Case Study in Pozantı Planning Unit, Turkey. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 238, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, M.; Maroschek, M.; Netherer, S.; Kremer, A.; Barbati, A.; Garcia-Gonzalo, J.; Seidl, R.; Delzon, S.; Corona, P.; Kolström, M.; et al. Climate Change Impacts, Adaptive Capacity, and Vulnerability of European Forest Ecosystems. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezquerro, M.; Pardos, M.; Diaz-Balteiro, L. Integrating Variable Retention Systems into Strategic Forest Management to Deal with Conservation Biodiversity Objectives. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 433, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felton, A.; Lindbladh, M.; Brunet, J.; Fritz, Ö. Replacing Coniferous Monocultures with Mixed-Species Production Stands: An Assessment of the Potential Benefits for Forest Biodiversity in Northern Europe. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 260, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, R.J. Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation in Forest Management: A Review. Ann. For. Sci. 2015, 72, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunette, M.; Foncel, J.; Kéré, E.N. Attitude towards Risk and Production Decision: An Empirical Analysis on French Private Forest Owners. Environ. Modeling Assess. 2017, 22, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibold, S.; Gossner, M.M.; Simons, N.K.; Blüthgen, N.; Müller, J.; Ambarlı, D.; Ammer, C.; Bauhus, J.; Fischer, M.; Habel, J.C.; et al. Arthropod Decline in Grasslands and Forests Is Associated with Landscape-Level Drivers. Nature 2019, 574, 671–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.C.; Spies, T.A.; Wardlaw, T.J.; Balmer, J.; Franklin, J.F.; Jordan, G.J. The Harvested Side of Edges: Effect of Retained Forests on the Re-Establishment of Biodiversity in Adjacent Harvested Areas. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 302, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedrowitz, K.; Koricheva, J.; Baker, S.C.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Palik, B.; Rosenvald, R.; Beese, W.; Franklin, J.F.; Kouki, J.; Macdonald, E.; et al. Can Retention Forestry Help Conserve Biodiversity? A Meta-analysis. J. Appl. Ecol. 2014, 51, 1669–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, L.; Kouki, J.; Sverdrup-Thygeson, A. Tree Retention as a Conservation Measure in Clear-Cut Forests of Northern Europe: A Review of Ecological Consequences. Scand. J. For. Res. 2010, 25, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenvald, R.; Lõhmus, A. For What, When, and Where Is Green-Tree Retention Better than Clear-Cutting? A Review of the Biodiversity Aspects. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 255, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauhus, J.; Puettmann, K.; Messier, C. Silviculture for Old-Growth Attributes. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, L.; Baker, S.C.; Bauhus, J.; Beese, W.J.; Brodie, A.; Kouki, J.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Lõhmus, A.; Pastur, G.M.; Messier, C.; et al. Retention Forestry to Maintain Multifunctional Forests: A World Perspective. BioScience 2012, 62, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, K.L. Multiaged Silviculture: Managing for Complex Forest Stand Structures; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-19-870306-8. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, J.F.; Berg, D.F.; Thornburg, D.; Tappeiner, J.C. Alternative silvicultural approaches to timber harvesting: Variable retention harvest systems. In Creating a Forestry for the 21st Century: The Science of Ecosystem Management; Kohm, K.A., Franklin, J.F., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, WA, USA, 1997; pp. 111–139. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, E.L.; Schulte, L.A.; Palik, B.J. Decade-Long Bird Community Response to the Spatial Pattern of Variable Retention Harvesting in Red Pine (Pinus Resinosa) Forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 402, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouki, J.; Löfman, S.; Martikainen, P.; Rouvinen, S.; Uotila, A. Forest Fragmentation in Fennoscandia: Linking Habitat Requirements of Wood-Associated Threatened Species to Landscape and Habitat Changes. Scand. J. For. Res. 2001, 16, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, A.S.; Tatsumi, S.; Gustafsson, L. Landscape Properties Affect Biodiversity Response to Retention Approaches in Forestry. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 1627–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustynczik, A.L.D.; Asbeck, T.; Basile, M.; Bauhus, J.; Storch, I.; Mikusiński, G.; Yousefpour, R.; Hanewinkel, M. Diversification of Forest Management Regimes Secures Tree Microhabitats and Bird Abundance under Climate Change. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 2717–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coşofreţ, C.; Bouriaud, L. Which Silvicultural Measures Are Recommended To Adapt Forests To Climate Change? A Literature Review. Bull. Transilv. Brasov. For. Wood Ind. Agric. Food Eng. 2019, 12, 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Augustynczik, A.L.D.; Yousefpour, R. Balancing Forest Profitability and Deadwood Maintenance in European Commercial Forests: A Robust Optimization Approach. Eur. J. For. Res. 2019, 138, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coote, L.; Dietzsch, A.C.; Wilson, M.W.; Graham, C.T.; Fuller, L.; Walsh, A.T.; Irwin, S.; Kelly, D.L.; Mitchell, F.J.G.; Kelly, T.C.; et al. Testing Indicators of Biodiversity for Plantation Forests. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 32, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, J.F. Toward a New Forestry. American Forests. November/December 1989. pp. 37–44. Available online: https://andrewsforest.oregonstate.edu/publications/1059 (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Gustafsson, L.; Bauhus, J.; Asbeck, T.; Augustynczik, A.L.D.; Basile, M.; Frey, J.; Gutzat, F.; Hanewinkel, M.; Helbach, J.; Jonker, M.; et al. Retention as an Integrated Biodiversity Conservation Approach for Continuous-Cover Forestry in Europe. Ambio 2020, 49, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, S.J.; Peterken, G.F. Deadwood in British Forests: Priorities and a Strategy. Forestry 1998, 71, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahalil, U.; Başkent, E.Z.; Sivrikaya, F.; Kılıç, B. Analyzing Deadwood Volume of Calabrian Pine (Pinus Brutia Ten.) in Relation to Stand and Site Parameters: A Case Study in Köprülü Canyon National Park. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.F.; Gittings, T.; Wilson, M.; French, L.; Oxbrough, A.; O’Donoghue, S.; O’Halloran, J.; Kelly, D.L.; Mitchell, F.J.G.; Kelly, T.; et al. Identifying Practical Indicators of Biodiversity for Stand-Level Management of Plantation Forests. Biodivers. Conserv. 2008, 17, 991–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenault, A.; Bradfield, G.E. Structural—Compositional Variation in Three Age-Classes of Temperate Rainforests in Southern Coastal British Columbia. Can. J. Botany 1995, 73, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugalho, M.N.; Dias, F.S.; Briñas, B.; Cerdeira, J.O. Using the High Conservation Value Forest Concept and Pareto Optimization to Identify Areas Maximizing Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services in Cork Oak Landscapes. Agrofor. Syst. 2016, 90, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearden, F.; Wardle, D. The Potential for Forest Canopy Litterfall Interception by a Dense Fern Understorey, and the Consequences for Litter Decomposition. Oikos 2008, 117, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, R.; Peace, A.J.; Newton, A.C. Macrofungal Communities of Lowland Scots Pine (Pinus Sylvestris L.) and Norway Spruce (Picea Abies (L.) Karsten.) Plantations in England: Relationships with Site Factors and Stand Structure. For. Ecol. Manag. 2000, 131, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Hedblom, M.; Emilsson, T.; Nielsen, A.B. The Role of Forest Stand Structure as Biodiversity Indicator. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 330, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendron, F.; Messier, C.; Comeau, P.G. Comparison of Various Methods for Estimating the Mean Growing Season Percent Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density in Forests. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1998, 92, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanina, L.; Bobrovsky, M.; Komarov, A.; Mikhajlov, A. Modeling Dynamics of Forest Ground Vegetation Diversity under Different Forest Management Regimes. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 248, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paffetti, D.; Travaglini, D.; Buonamici, A.; Nocentini, S.; Vendramin, G.G.; Giannini, R.; Vettori, C. The Influence of Forest Management on Beech (Fagus Sylvatica L.) Stand Structure and Genetic Diversity. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 284, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, G.; Moro, M.J. Birds of Aleppo Pine Plantations in South-East Spain in Relation to Vegetation Composition and Structure. J. Appl. Ecol. 1997, 1257–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockerhoff, E.G.; Jactel, H.; Parrotta, J.A.; Quine, C.P.; Sayer, J. Plantation Forests and Biodiversity: Oxymoron or Opportunity? Biodivers. Conserv. 2008, 17, 925–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.F.; Halterman, B.G.; Lyon, T.J.; Miller, R.L. Integrating Timber and Wildlife Management Planning. For. Chron. 1973, 49, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hof, J.G.; Joyce, L.A. A Mixed Integer Linear Programming Approach for Spatially Optimizing Wildlife and Timber in Managed Forest Ecosystems. For. Sci. 1993, 39, 816–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hof, J.; Bevers, M.; Joyce, L.; Kent, B. An Integer Programming Approach for Spatially and Temporally Optimizing Wildlife Populations. For. Sci. 1994, 40, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinger, P.; Sessions, J.; Boston, K. Using Tabu Search to Schedule Timber Harvests Subject to Spatial Wildlife Goals for Big Game. Ecol. Model. 1997, 94, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.L.; Camm, J.D.; Haight, R.G.; Montgomery, C.A.; Polasky, S. Weighing Conservation Objectives: Maximum Expected Coverage versus Endangered Species Protection. Ecol. Appl. 2004, 14, 1936–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, S.A.; Haight, R.G.; ReVelle, C.S. A Scenario Optimization Model for Dynamic Reserve Site Selection. Environ. Modeling Assess. 2005, 9, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, S.F.; Haight, R.G.; Rogers, L.W. Dynamic Reserve Selection: Optimal Land Retention with Land-Price Feedbacks. Oper. Res. 2011, 59, 1059–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marto, M.; Reynolds, K.; Borges, J.; Bushenkov, V.; Marques, S. Combining Decision Support Approaches for Optimizing the Selection of Bundles of Ecosystem Services. Forests 2018, 9, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.G.; Garcia-Gonzalo, J.; Bushenkov, V.; McDill, M.E.; Marques, S.; Oliveira, M.M. Addressing Multicriteria Forest Management With Pareto Frontier Methods: An Application in Portugal. For. Sci. 2014, 60, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.M. Using a Logic Framework to Assess Forest Ecosystem Sustainability. J. For. 2001, 99, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ezquerro, M.; Pardos, M.; Diaz-Balteiro, L. Operational Research Techniques Used for Addressing Biodiversity Objectives into Forest Management: An Overview. Forests 2016, 7, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novais, A.; Canadas, M.J. Understanding the Management Logic of Private Forest Owners: A New Approach. For. Poilicy Econ. 2010, 12, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Order No. 58/2019 Approving the Regional Programme for Forestry Planning in Entre Douro e Minho (PROF EDM). 2019. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC183340 (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Marques, M.; Oliveira, M.; Borges, J.G. An Approach to Assess Actors’ Preferences and Social Learning to Enhance Participatory Forest Management Planning. Trees, Forests and People 2020, 2, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, J.H.N. CliPick: Project Database of Pan-European Simulated Climate Data for Default Model Use; AGFORWARD—Agroforestry in Europe: Milestone Report 26 (6.1) for EU FP7 Research Project: AGFORWARD 613520. 10 October 2015, p. 22. Available online: https://www.agforward.eu/index.php/en/clipick-project-database-of-pan-european-simulated-climate-data-for-default-model-use.html (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Rodrigues, A.R.; Botequim, B.; Tavares, C.; Pécurto, P.; Borges, J.G. Addressing Soil Protection Concerns in Forest Ecosystem Management under Climate Change. For. Ecosyst. 2020, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meijgaard, E.; van Ulft, L.H.; Lenderink, G.; de Roode, S.R.; Wipfler, L.; Boers, R.; Timmermans, R.M.A. Refinement and Application of a Regional Atmospheric Model for Climate Scenario Calculations of Western Europe. Clim. Chang. Spat. Plan. Publ. 2012, 12, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, J.H.N. CliPick—Climate Change Web Picker. A Tool Bridging Daily Climate Needs in Process Based Modelling in Forestry and Agriculture. For. Syst. 2017, 26, eRC01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Change in Portugal. Scenarios, Impacts and Adaptation Measures. SIAM Project—1ª Edição. Available online: http://www.scielo.mec.pt/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0870-63522006000100012 (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Barreiro, S.; Rua, J.; Tomé, M. StandsSIM-MD: A Management Driven Forest SIMulator. For. Syst. 2016, 25, eRC07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.; Tomé, J.; Tomé, M. Prediction of Annual Tree Growth and Survival for Thinned and Unthinned Even-Aged Maritime Pine Stands in Portugal from Data with Different Time Measurement Intervals. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 262, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, M.; Oliveira, T.; Soares, P. The GLOBULUS 3.0 Model Data and Equations; Publicações GIMREF; Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Intituto Superior de Agronomia, Centro de Estudos Florestais: Lisboa, Portugal, 2006; p. 26. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Filipe, A.F.L. Implementation of a Growth Model for Chestnut in the StandsSIM.md Forest Simulator. Master’s Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2019. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

- Patrício, M.S. Analysis of the Productive Potential of Chestnut in Portugal. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2006. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-García, E.; Crecente-Campo, F.; Barrio-Anta, M.; Diéguez-Aranda, U. A Disaggregated Dynamic Model for Predicting Volume, Biomass and Carbon Stocks in Even-Aged Pedunculate Oak Stands in Galicia (NW Spain). Eur. J. For. Res. 2015, 134, 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-García, E.; Diéguez-Aranda, U.; Cunha, M.; Rodríguez-Soalleiro, R. Comparison of Harvest-Related Removal of Aboveground Biomass, Carbon and Nutrients in Pedunculate Oak Stands and in Fast-Growing Tree Stands in NW Spain. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 365, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulo, J.A.; Tomé, J.; Tomé, M. Nonlinear Fixed and Random Generalized Height–Diameter Models for Portuguese Cork Oak Stands. Ann. For.t Sci. 2011, 68, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulo, J.A.; Palma, J.H.N.; Gomes, A.A.; Faias, S.P.; Tomé, J.; Tomé, M. Predicting Site Index from Climate and Soil Variables for Cork Oak (Quercus Suber L.) Stands in Portugal. New For. 2015, 46, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faias, S.P.; Palma, J.H.N.; Barreiro, S.M.; Paulo, J.A.; Tomé, M. Resource Communication. SIMfLOR—Platform for Portuguese Forest Simulators. For. Syst. 2012, 21, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-González, P.M.; Stella, J.C.; Campelo, F.; Ferreira, M.T.; Albuquerque, A. Subsidy or Stress? Tree Structure and Growth in Wetland Forests along a Hydrological Gradient in Southern Europe. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 2015–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, H.; Oosterbaan, A.; Savill, P.; Rondeux, J. A Review of the Characteristics of Black Alder (Alnus Glutinosa (L.) Gaertn.) and Their Implications for Silvicultural Practices. Forestry 2010, 83, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botequim, B.; Zubizarreta-Gerendiain, A.; Garcia-Gonzalo, J.; Silva, A.; Marques, S.; Fernandes, P.; Pereira, J.; Tomé, M. A Model of Shrub Biomass Accumulation as a Tool to Support Management of Portuguese Forests. Forest 2015, 8, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICNF. Adaptation of Forests to Climate Change—Work under the National Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change; Ministério da Agricultura, do Mar e Ambiente e do Ordenamento do Território: Terreiro do Paço, Lisboa, 2013; p. 112. (In Portuguese)

- Marques, M.; Juerges, N.; Borges, J.G. Appraisal Framework for Actor Interest and Power Analysis in Forest Management—Insights from Northern Portugal. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 111, 102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, S.; Marto, M.; Bushenkov, V.; McDill, M.; Borges, J. Addressing Wildfire Risk in Forest Management Planning with Multiple Criteria Decision Making Methods. Sustainability 2017, 9, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.; Constantino, M.F.; Borges, J.G.; Garcia-Gonzalo, J. Addressing Wildfire Risk in a Landscape-Level Scheduling Model: An Application in Portugal. For. Sci. 2015, 61, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V12. 1: User’s Manual for CPLEX. Available online: ftp://public.dhe.ibm.com/software/websphere/ilog/docs/optimization/cplex/ps_usrmancplex.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Dieler, J.; Uhl, E.; Biber, P.; Müller, J.; Rötzer, T.; Pretzsch, H. Effect of Forest Stand Management on Species Composition, Structural Diversity, and Productivity in the Temperate Zone of Europe. Eur. J. For. Res. 2017, 136, 739–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M.-C.; Wardle, D.A. Understory Vegetation as a Forest Ecosystem Driver: Evidence from the Northern Swedish Boreal Forest. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2005, 3, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćosović, M.; Bugalho, M.; Thom, D.; Borges, J. Stand Structural Characteristics Are the Most Practical Biodiversity Indicators for Forest Management Planning in Europe. Forests 2020, 11, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, I.; Mackey, B.; McNulty, S.; Mosseler, A. Forest Resilience, Biodiversity, and Climate Change. In Proceedings of the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, QC, Canada, 22 September 2009; Volume 43, pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Biber, P.; Felton, A.; Nieuwenhuis, M.; Lindbladh, M.; Black, K.; Bahýl’, J.; Bingöl, Ö.; Borges, J.G.; Botequim, B.; Brukas, V.; et al. Forest Biodiversity, Carbon Sequestration, and Wood Production: Modeling Synergies and Trade-Offs for Ten Forest Landscapes Across Europe. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugalho, M.N.; Caldeira, M.C.; Pereira, J.S.; Aronson, J.; Pausas, J.G. Mediterranean Cork Oak Savannas Require Human Use to Sustain Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 9, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.G.; Marques, S.; Garcia-Gonzalo, J.; Rahman, A.U.; Bushenkov, V.; Sottomayor, M.; Carvalho, P.O.; Nordström, E.-M. A Multiple Criteria Approach for Negotiating Ecosystem Services Supply Targets and Forest Owners’ Programs. For. Sci. 2017, 63, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, J.; Egoh, B.; Willemen, L.; Liquete, C.; Vihervaara, P.; Schägner, J.P.; Grizzetti, B.; Drakou, E.G.; Notte, A.L.; Zulian, G.; et al. Mapping Ecosystem Services for Policy Support and Decision Making in the European Union. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 1, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proença, V.M.; Pereira, H.M.; Guilherme, J.; Vicente, L. Plant and Bird Diversity in Natural Forests and in Native and Exotic Plantations in NW Portugal. Acta Oecologica 2010, 36, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goded, S.; Ekroos, J.; Domínguez, J.; Azcárate, J.G.; Guitián, J.A.; Smith, H.G. Effects of Eucalyptus Plantations on Avian and Herb Species Richness and Composition in North-West Spain. Global Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 19, e00690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calviño-Cancela, M.; Rubido-Bará, M.; van Etten, E.J. Do Eucalypt Plantations Provide Habitat for Native Forest Biodiversity? For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 270, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörl, J.; Keller, K.; Yousefpour, R. Reviewing the Performance of Adaptive Forest Management Strategies with Robustness Analysis. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 119, 102289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikinmaa, L.; Lindner, M.; Cantarello, E.; Jump, A.S.; Seidl, R.; Winkel, G.; Muys, B. Reviewing the Use of Resilience Concepts in Forest Sciences. Curr. For. Rep. 2020, 6, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olano, M.; Beñaran, H.; Laso, M.; Arizaga, J. Exotic Pine Plantations and the Conservation of the Threatened Red Kite Milvus Milvus in Gipuzkoa, Northern Iberia. Ardeola 2016, 63, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Forest Species | Forest Management Models—FMMs (Forest Cover, %) | Prescriptions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tree Density | Harvesting | Thinning | ||

| Maritime pine (Pinus pinaster) | cFMM1 (73%) cFMM2 (33%) | Plantation 2200 trees/ha−1 | Clear cutting systems|rotations lengths of 40 to 60 y | Pre-commercial|10-y Commercial|Every 5-y between 20 and 50 years of age (up to 5 years before the final harvest) based on a Wilson factor of 0.2 |

| Eucalypt (Eucalyptus globulus) | cFMM1 (27%) cFMM2 (67%) cFMM4 (100%) | Plantation 1400 trees/ha−1 | Coppice systems| ranging from 10 to 12 y | Leaving two shoots per stool on the 3rd year of each cycle |

| Chestnut (Castanea sativa) | cFMM3 (100%) | Plantation 1250 trees/ ha−1 | Clear cutting systems|rotations lengths of 40 to 70 y | Alternative periodicities of 5 or 10 years starting at age 15 |

| Maritime pine (Pinus pinaster) | aFMM5 (100%) | Plantation 1111 trees/ha−1 | Clear cutting systems|rotations lengths between 35 and 50 y | Pre-commercial|15-y Commercial|every 10 years in the period from 25 to 45 years of age |

| Pedunculate oak (Pedunculate oak) | aFMM6 (100%) | Plantation 1600 trees /ha−1 | Clear cutting systems|rotation lengths of 40, 50, and 60 years | Periodicities at 27, 37, and 45-years |

| Cork oak (Quercus suber) | aFMM7 (100%) | Plantation 1600 trees/ ha−1 | 1st debarking|30 y 2nd debarking|40 y 3rd debarking|every 9 y | Five thinning’s at 15, 30, 40, 58, and 76-years |

| Riparian species (Alnus glutinosa, Salix atrocinera, Salix alba, Fraxinus angustifolia, Populus nigra) | aFMM8 (100%) | 5000 trees/ ha−1 | --- | --- |

| Biodiversity Proxies | Specific Indicator | Stand FMM | Landscape FMM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stand Scale/Landscape | (Value Calculated) | (Value Calculated) | |

| Tree species composition | Tree species proportion | ||

| Differentiation between tree species of higher or lower importance for biodiversity (e.g., native vs. introduced, oak vs. eucalyptus) | corresponding tree species, stand age and maximum rotation | Value per period | |

| Understory vegetation | Shrub biomass accumulation | ||

| Increased shrub cover in forest plantation stands, increases habitat heterogeneity and habitat structural diversity, therefore potentially benefiting biodiversity at the species-level | shrub cover: age of the shrub and accumulation of maximum biomass | Value per period | |

| FMM | Species Proportion | Species Rotation | Species Min Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pb(0.73) | Ec(0.27) | Pb(50) | Ec(12) | Pb(2) | Ec(1) |

| 2 | Ec(0.67) | Pb(0.33) | Ec(12) | Pb(50) | Ec(1) | Pb(2) |

| 3 | Ct(1) | Ct(55) | Ct(3) | |||

| 4 | Ec(1) | Ec(12) | Ec(1) | |||

| 5 | Pb(1) | Pb(50) | Pb(2) | |||

| 6 | Qr(1) | Qr(60) | Qr(4) | |||

| 7 | Sb(1) | Sb(90) | Sb(4) | |||

| 8 | Rp(1) | Rp(90) | Rp(5) | |||

| Set/Variables/Data | Description |

|---|---|

| N | the number of management units (1373) |

| M | the number of prescriptions for each stand i (they include the 5 shrub cleaning options and the option to resin or not pure stands of maritime pine) |

| P | the number of planning periods (9) |

| F | the number of forest management models (8) |

| biodiversity indicator in period t that results from assigning to stand i prescription j, ranging from 0 to 8 (high level of biodiversity) | |

| the set of prescriptions that were classified as belonging to a forest management planning | |

| CS_Area | Case study area (14,765 ha) |

| the area assigned to forest management model f | |

| is the percentage of prescription j in management unit i | |

| the area occupied by each specie in the management unit i | |

| the pine timber flow in period t that results from assigning prescription j to stand i | |

| the eucalypt flow timber in period t that results from assigning prescription j to stand i | |

| the chestnut flow timber in period t that results from assigning prescription j to stand i | |

| the pedunculated oak flow timber in period t that results from assigning to stand i prescription j | |

| the cork oak flow timber in period t that results from assigning to stand i prescription j | |

| the standing volume in the ending inventory in stand i when assigning prescription j in period 9 | |

| Wildfire resistance indicator in period t that results from assigning to stand i prescription j. The resultant stand-level values were averaged for the whole landscape and scaled from “1” to “5”, where “1” means less resistance and “5” more fire resistance. | |

| the average biodiversity indicator from the landscape along the 90-year planning horizon. | |

| the total wood production in the CSA | |

| total landscape standing volume at the end of the planning horizon (period 9) | |

| the average wildfire resistance from the landscape along the 90-year planning horizon. |

| Optimal Solution | Objective | Constraints | Local-Climate Scenario | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAU | REF | |||

| #1 | Max BIOD | -------- | 3.82 | 3.73 |

| #2 | Max BIOD | Wood > 9 × 106 m3 & 0.9 × Woodt−1 ≤ Woodt ≤ 1.1 × Woodt+1 | 3.30 | 3.26 |

| #3 | Max BIOD | Wood > 9 × 106 m3 & 0.9 × Woodt−1 ≤ Woodt ≤ 1.1 × Woodt+1 & WRisk > 3 | 3.27 | 3.22 |

| Optimal Solution | Wood (106 m3) | Volume (106 m3) | Standing Volume (106 m3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harvesting | Thinning | |||

| #1_BAU | 5.26 | 3.80 | 1.45 | 1.77 |

| #1_REF | 5.38 | 3.69 | 1.69 | 1.79 |

| #2_BAU | 9.00 | 7.56 | 1.43 | 1.16 |

| #2_REF | 9.00 | 7.60 | 1.40 | 1.17 |

| #3_BAU | 9.00 | 7.48 | 1.52 | 1.20 |

| #3_REF | 9.00 | 7.56 | 1.45 | 1.21 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Botequim, B.; Bugalho, M.N.; Rodrigues, A.R.; Marques, S.; Marto, M.; Borges, J.G. Combining Tree Species Composition and Understory Coverage Indicators with Optimization Techniques to Address Concerns with Landscape-Level Biodiversity. Land 2021, 10, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020126

Botequim B, Bugalho MN, Rodrigues AR, Marques S, Marto M, Borges JG. Combining Tree Species Composition and Understory Coverage Indicators with Optimization Techniques to Address Concerns with Landscape-Level Biodiversity. Land. 2021; 10(2):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020126

Chicago/Turabian StyleBotequim, Brigite, Miguel N. Bugalho, Ana Raquel Rodrigues, Susete Marques, Marco Marto, and José G. Borges. 2021. "Combining Tree Species Composition and Understory Coverage Indicators with Optimization Techniques to Address Concerns with Landscape-Level Biodiversity" Land 10, no. 2: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020126

APA StyleBotequim, B., Bugalho, M. N., Rodrigues, A. R., Marques, S., Marto, M., & Borges, J. G. (2021). Combining Tree Species Composition and Understory Coverage Indicators with Optimization Techniques to Address Concerns with Landscape-Level Biodiversity. Land, 10(2), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020126