Abstract

Tension and conflict are endemic to any upgrading initiative (including basic infrastructure provision) requiring private land contributions, whether in the form of voluntary donations or compensated land acquisitions. In informal urban contexts, practitioners must first identify well-suited land for public infrastructure, both spatially and with careful consideration for safeguarding claimed rights and preventing conflicts. At the same time, they need to defuse existing tensions over land ownership and land use rights while negotiating for the potential use of a unit of land for infrastructure. Even in the case of employing participatory methods, land negotiations are never tension-free. Despite the extensive literature on linkages between urban poverty, inefficient land management systems, and land disputes, in both rural and urban settings, land negotiations for community-scale infrastructure retrofit projects (e.g., neighbourhood roads, water and sanitation infrastructure) are yet to be fully explored. Drawing on a case study of a live green infrastructure retrofit project in six informal settlements in Makassar, Indonesia, we establish links to exchange theory, collective action, and negotiation theory to build a reliable analytical framework for understanding and explaining the land negotiations in small-scale infrastructure retrofit practices. We aim to describe and assess the fundamental conditions for land negotiations in an informal urban context and conclude the paper by summarising several key strategies developed and used in the case study area to forge land agreements.

1. Introduction

The interactions between different rights-holders and those with interests in land can lead to unintended consequences in land negotiation processes. Scholars have discussed land conflicts and negotiation challenges in various terms, including the correlational–causal analysis of land conflicts [1,2,3,4,5], the impact analysis of conflict situations on urban development [6,7,8,9], and providing preventative or responsive measures to address land conflicts [10,11,12,13]. Despite the extensive literature on linkages between inefficient land management systems, urban poverty, and land disputes in both rural and urban settings, land negotiations for community-scale infrastructure projects (e.g., neighbourhood roads, water and sanitation infrastructure) receive relatively little attention. Furthermore, the tensions and conflicts in land rights that emerge during land negotiations for community-level basic infrastructure provision are yet to be fully explored.

Tension and conflict in land negotiations within micro-scale upgrading projects are sensitive topics that are often not raised directly in the literature for various reasons. Ethical considerations and the need to protect households’ sensitive data (e.g., land ownership data) are among the main challenges in exploring and explaining land negotiations [14]. Moreover, publicly available project reports are often explicitly designed to protect the reputation of the upgrading initiatives, government agencies, and impacted communities [15]. Similarly, the effectiveness of land negotiation strategies and pre-defined conflict resolution mechanisms—proposed by governments, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and international aid organisations at the project initiation—are often not evaluated, at least not until the end of the projects’ lifetime and before new programs have widely replaced them [8].

In reviewing the related literature, two main streams are identified in this area. The first stream explores land use and land ownership conflicts, their causes, and their consequences for development. The classification of land conflicts and providing practical guides, technical tools, and policy recommendations for conflict prevention and management in urban and rural settings are continuing concerns for scholars in this group. The most significant research has been carried out by Global Land Tool Network (GLTN) [10,13] and its partners, particularly Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) [12]. Several significant research outputs have been produced by this group, such as country-specific inventories concerning the route cause analysis of land conflicts and action recommendations [16], and practical guides for understanding, preventing, and solving land conflicts [12].

The second literature stream applies major theories of social exchange, social interaction, and social structure to explore how individuals (different actors) compete, struggle, cooperate, and negotiate for gaining access to land, property, and natural resources and how collective action takes place for the collective use and control of resources. Several significant research outputs have been developed by this group, such as the Access Mechanism proposed by Ribot and Peluso (2003) [17,18]. However, land negotiations for community-scale infrastructure projects in urban areas and informal settlements have received far less attention in these studies. Considering the limited literature, this paper draws primarily upon Leeuwis’s (2000) highly cited publication on the negotiation approach in participatory projects in rural communities. Leeuwis’s approach to the negotiation process has been employed increasingly by scholars in the field of participatory research and has assisted them to develop several guidelines for facilitating negotiation processes [19,20,21,22].

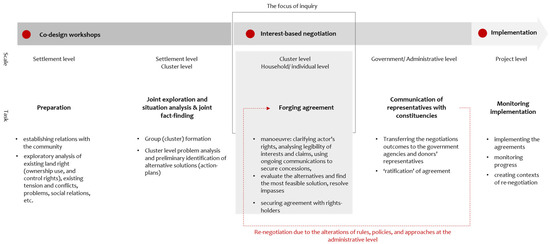

In line with Leeuwis’s (2000) classification of negotiation processes, acquiring land for infrastructure retrofit in our case study is based on the integrative negotiation approach (compared to distributive negotiation). For Van Meegeren and Leeuwis (1999), an integrative negotiation process comprises several main tasks including preparation, joint-fact-finding and collaborative situation analysis, forging agreement, communication of representatives with constituencies, and monitoring implementation [23] (see Figure 1). Therefore, the integrative negotiation process is based on collective action and follows a nonlinear process wherein negotiation tasks can be employed repeatedly at any stage of the negotiation process [24,25]. However, some of these negotiation tasks become important as the negotiation process moves forward, while others are more relevant at the early stages of the process [25].

Figure 1.

Integrative negotiation processes in the RISE Project developed by authors based on Van Meegeren and Leeuwis (1999) [23].

The analysis and discussions in this paper establish links to exchange theory, collective action, and negotiation theory. Within the integrative negotiation approach, we narrow our study’s focus to the forging agreement process (Figure 1). As the administrative-level negotiation meetings (macro-level negotiations with local government agencies and project donors) in our case study at the time of writing this paper are still ongoing, we only focus on negotiation meetings and the micro-level dynamics influencing the advancement of agreements at the household and community levels. This allows us to understand and explain how residents of informal settlements in our case study negotiate land for wastewater infrastructure upgrades. In this paper, we aim to explain the process of land negotiation instead of the product and outcome—such as land procurement mechanisms and design proposals—and explore fundamental conditions that enable households to negotiate land for public infrastructure.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. First, we describe the case study design and research tactics, including the data collection techniques. Then, the findings from the case study of six kampung communities in Makassar and semi-structured interviews are grounded in the existing theories to set out the fundamental conditions allowing for land negotiations in our case study. Then, several negotiation strategies for community-scale infrastructure retrofit practices are presented based on findings from the case study.

2. Research Design and Methods

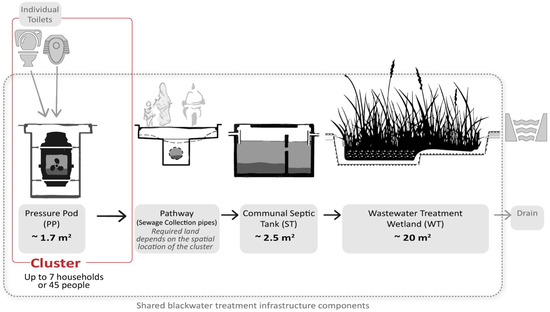

This research uses a multiple case study design and follows a ‘replication logic’ instead of ‘sampling logic’ [26] for selecting cases. The relevance of replication logic is informed by our case study’s scope and geography and studying a live project [27]. We focused on the Revitalising Informal Settlement and their Environment (RISE) Project as a live case of wastewater infrastructure retrofit practice in six kampung communities (comprising 1466 residents across 335 dwellings) in Makassar, Indonesia. The Project engages each kampung community in a participatory design process to implement small-scale, low impact, tertiary infrastructure. The provided infrastructure includes a range of nature-based technologies and design strategies tailored to each site’s water and sanitation stressors. This service provision model (Figure 2) appears to be an alternative, cost-effective solution for expanding essential infrastructure to informal settlements, particularly where the conventional service delivery approaches fail to respond to sanitation improvement demands [28,29]. However, a set of spatial and environmental considerations need to be met in terms of the sustainable operation, maintenance demands, and space requirements [29]. In this sense, a sustainable retrofit practice is both a product of intelligent design solutions and socially and environmentally conscious decisions about the location of infrastructure components.

Figure 2.

Infrastructure delivery model in the RISE Project and an example of land requirements for shared blackwater treatment infrastructure components at cluster level.

For the purpose of this paper, we only focused on the most space demanding green infrastructure components, including wastewater treatment wetlands (subsurface and surface flow wetlands), pressure sewer systems, septic tanks, and access improvements for maintenance purposes. These infrastructure components are collective rather than individual and service several households. Therefore, decision making for the preferred land procurement mechanisms and the location of these infrastructure components occurs at the group level (more than one household). A servicing group in the RISE Project is called a ‘cluster’ and is formed based on social considerations and spatial proximities. The formation of these clusters is attributed to the advantages in the pressure sewer systems (hereafter referred to as pressure pods), which can provide services to a cluster of up to 7 households or 45 people [28,30,31].

We used a mix of tactics (research methods) for data collection in this paper, including semi-structured interviews and documentation. The semi-structured interviews comprise several participant groups such as RISE land negotiation facilitators (two participants), representatives from local upgrading projects (four participants), and local government agencies (eight participants). We must highlight that, due to the sensitivity of land tenure and land negotiations in the RISE Project, direct interviews and meetings with the households were exclusively limited to the RISE facilitators. Therefore, we considered alternative and complementary data resources where possible such as documentation. The documentation involves communications with the local community and households, documented by the in-country field workers (2019–2020), administrative documents such as project reports, minutes of meetings (with different stakeholders and actors), and other reports of project events (co-design workshops and notes).

We used three qualitative data analysis techniques including ‘open coding’, ‘axial coding’, and ‘selective coding’ [32,33,34]. Open coding was undertaken on meeting minutes, negotiation records, and interview transcripts. Axial coding was used to ask about conditions, actions/interactions, and consequences or outcomes of land negotiations. Finally, selective coding or theoretical coding, as the final step, was used to develop a substantive theory. This theory is presented as a discussion in Section 3.2 and Section 4. This step was accompanied by a checking exercise consisting of a joint interview with key land negotiation facilitators in the RISE Project. In the checking exercise, the participants were asked to share their views (agreement and disagreement) regarding the presented findings and emerging theory. The responses were then used to refine the emerging theory.

3. Case Study, Results, Findings, and Analysis

3.1. Case Study Setting

Makassar, also known as Ujung Padang, is the administrative capital of Indonesia’s Sulawesi Island and the country’s fifth-largest urban centre. The six kampung communities in our case study have an acceptable degree of de facto tenure security; however, despite the need for infrastructure upgrades, high population densities, insufficient land, and frequent exposure to flooding render the existing local best practice approaches (e.g., lined septic tanks without an infiltration field) unfeasible.

At the outset of the location decision making for infrastructure, the RISE Project organised co-design workshops as a vehicle to improve local knowledge about the infrastructure and to build trust in communities, before embarking on land negotiations. After this primary stage and forming servicing clusters, the RISE negotiation facilitators initiated the negotiation process. The following section presents the findings from the case study of the land negotiation processes in this project.

3.2. Linking Theoretical Perspectives to the Negotiation Approach

In a social exchange context, actors face competing pressure to simultaneously satisfy their interests and participate in the provision of collective goods [35]. Therefore, collective action becomes a challenge as individuals must protect their resources, and at the same time, negotiate over social goods and fulfil their social obligations towards groups to which they belong. Collective action is challenging to explore and explain due to the multiple dimensions involved in the individuals’ decision-making processes—essentially when valuable and scarce resources are at stake—and the difficulties in disentangling the distinct impacts of each dimension on one’s decisions.

Poteete and colleagues (2010) define the collective action problem as a situation when individuals’ interests (and rationality to protect their valuable resources) compete with the optimal outcomes for a group [36]. In this situation, joint action is discouraged as individuals hope to benefit from the contributions of others while limiting their contributions and costs [36]. Collective action is often used to justify the participatory approach as a leading principle for intervention practices, development, and upgrading initiatives such as sanitation improvements [20,25,37,38,39]. This justification fostered a greater attention to developing a range of collaborative and participatory methodologies, tools, and techniques for operationalising the participatory approach in upgrading projects. However, the generalisation of individuals’ responses to a shared problem, and assuming similar desire or moral obligation for all the actors to engage in decision-making and exchange processes, have been recently criticised [25,40,41]. To overcome these uncertainties and conflicts that emerge within the participatory processes, Leeuwis (2000) suggested using negotiation theory to reframe participatory development efforts. Accordingly, he describes three fundamental conditions as part of the enabling environment that will allow for the integration of negotiation approaches into different participatory processes and conflict resolution situations [25,42]. These fundamental conditions include divergence of interests, mutual interdependence between stakeholders, and the ability to communicate.

In the following section, findings from the case study of the RISE Project are grounded in the exchange theory, collective action, and negotiation theory to explain the fundamental conditions for land negotiation in a multi-layered and complex land tenure system where different interests coexist in a single unit of land. We frame the discussion according to enabling environment for land negotiation, suggested by Leeuwis (2000). Where needed, further references are made to relevant examples of land negotiations in our case study.

3.2.1. Divergence of Interests

A divergence of interests is often at the basis of any negotiation. Divergence of interests in an infrastructure retrofit project is often associated with the value of land and the change in this value as a result of the infrastructure provision. Within an informal urban context, such as kampung communities, acquiring land for infrastructure is a substantial challenge due to the complex nature of land rights and informal tenure arrangements, dense settlement patterns, and unstable environmental conditions [43,44,45,46,47,48]. Various actors may acquire or claim the rights to use, control, and manage a unit of land in reference to a range of state and customary laws, religious orders, or informal codes and agreements [49]. A unit of land can also be, simultaneously, subject to several interests: overlapping interests, complementary interests, and competing interests [50,51,52]. These land interests must be carefully identified and protected to ensure the feasibility of implementation and the sustainability of the outcomes of upgrading projects.

Depending on the interests at stake, and different actors involved, tension and conflict may arise during the negotiation processes. We identified three types of land conflicts in this regard—the first type is associated with conflicts between local government agencies and communities. An example of this is where a previously improved access road is disputed as the local government reneged on the agreements to compensate households’ land contributions once the road was built. The second type exists between kampung communities and large land-holding groups such as developers near these settlements. Such tensions are often related to the boundary disputes and conflict over access passing through a private developer’s land. For example, where residents’ plots and a developer’s land are adjacent, the determination of unclear plot boundaries can generate tension. Since expanding the existing houses or developing secondary buildings with minimal setbacks is likely to occur by encroaching ownership boundaries, these land tensions can mount to a conflict situation. Likewise, the developer can push back the boundaries of the residents’ plots by establishing the walls outside the actual ownership boundaries.

The third type of conflict in negotiation arises from divergence of interests in land and tensions between neighbours. This type is also associated with boundary disputes, conflict over informal use rights (e.g., informal access roads and rights of way), conflict due to horizontal expansion of dwellings over an access road or private spaces of neighbours, and long-standing tensions due to unequal land contributions for shared benefits (e.g., previous pathway improvements). Divergence of interests in land and people’s needs and values for the change (here receiving the RISE infrastructure and connecting to the provided sewerage system and living in a healthier neighbourhood) cultivate exchange relations among people with respect to land rights and benefit flows. Such exchange relations already exist in many informal settlements, particularly where the use rights are shared among a group of households—i.e., informal pathways [51]. However, these exchange relations are dynamic and can change over time. Consequently, conflicts of interest in land can emerge wherever people strive for gaining, maintaining, or controlling particular benefits, which can lead to cooperation, competition, or conflict in land negotiations. In this case, despite having participatory processes, some actors may simply not be willing to or be able to participate in the negotiation process.

3.2.2. Mutual Interdependence

In reaching an acceptable solution for a shared problem (here, the problem is poor sanitation and environmental contamination resulting in health issues), the individual’s decisions and the key stakeholders’ behaviour impact the outcomes for the other actors. Accordingly, a level of dependence exists among actors in the negotiation process. If the key stakeholders do not perceive the shared problem as their concern, a negotiation approach is not viable [25,53]. However, this mutual interdependence in no way implies that all the actors have equal control/power in the decision-making process.

Subject to different conditions, the households may achieve desirable outcomes regardless of the actions of others. In such instances, access to enough land in a suitable location (fitness of unoccupied private land for infrastructure or locational advantages due to proximity to available public land) makes the households independent from the others. An example of this situation can be seen where neighbouring residents around a semi-public alleyway (i.e., pathways with private ownership and granted use rights shared among neighbours for access) do not consider similar needs for pathway improvement as some of them are accessed by an alternative public road in the settlement. Consequently, those with better access have remained disinclined to improve the pathway, and therefore they have maintained more unbuilt, well-suited land in their backyard space and decided to have an individual system for their cluster. These households are equipped to form a self-contained cluster by contributing part of their unoccupied private land for individual wetlands, septic tanks, and other infrastructure components.

However, in many other cases, spatial constraints and land tenure complexities often make households dependent on the decisions and actions of particular rights-holders and stakeholders to determine if they achieve the desired outcomes—i.e., receiving the shared infrastructure and connecting to the provided sewerage system.

Cooperation among neighbours and collective actions can occur to obtain tangible resources—e.g., a pathway and use rights, or intangible resources—e.g., a better relationship with neighbours and cultivating community support. As observed in the RISE settlements, many of these spatial and social exchanges currently exist in kampung communities, allowed by non-formal land rights and land use arrangements. However, introducing spatial alterations and reshaping the existing rights as part of retrofitting infrastructure and confining these informal agreements by long-term or permanent transfer of rights to government authorities can cause tension, particularly if the changes menace the rights-holders’ agency over land.

We identified four main causes of interdependence for land negotiations in our case study. In the following section, we define them based on the potential advantages and limitations faced by people in controlling land interests and connecting to infrastructure.

- Rights-based advantages refer to one’s ability to negotiate and benefit from a negotiation situation based on the land rights granted by law or customary arrangements. Rights-based advantages provide the rights-holders with enforcement opportunities (potential power) to gain, maintain, or control interests in land [17,18]. An example of this is observed where the uncertain status of alleyways in a resettled community created conflict between households and the head of community unit (Rukun Tetangga or RT), followed by denying the households’ rights in decision making about the use rights in this part of the settlement. The households who do not retain such rights—e.g., due to unclear land status after resettlement, are dependent on other rights-holders to gain or maintain a benefit—e.g., maintaining the rights-of-way or connecting to infrastructure. Those registered land rights protected by law, custom, or convention often provide a more significant say for their holders in the decision-making process. An example of this is the case of squatting on private land, where squatters around formalised plots (land ownership certificates) are often excluded from upgrading projects despite the obtained permission from the landowner and approval of the head of community unit or neighbourhood unit (RT/RW heads).

- Spatial and location-specific advantages in the RISE context are attributed to the location-specific opportunities that enable a household to connect to shared infrastructure located on public land with no land contribution. In other cases, taking advantage of shared infrastructure depends on private land contributions from other households—e.g., for pressure pods, sewer collection pipes, and access. In this case, a connected chain of decisions may create high levels of interdependence, subsequently providing more power to some households and rights-holders and putting others in a more power-disadvantaged position.

- Perceived needs for basic infrastructure and individual preferences are also strongly linked to the negotiability of a unit of land for public infrastructure. The households’ perception of the necessity or benefits of wastewater collection infrastructure affects their decisions and justifies their willingness to contribute land for improved infrastructure. According to the interviews with the RISE negotiation facilitators, many households consider higher values for the direct benefit of infrastructure to their family—e.g., an individual toilet, compared to the environmental benefits provided by improved wastewater collection infrastructure. In this case, if the household has a toilet, they may see no value in connecting to the system and may refuse to contribute land for infrastructure. Furthermore, based on interviews with the RISE Project’s negotiation facilitators and representatives from local government agencies (including the Spatial Planning Unit, Regional Development Planning Agency, and Public Works Unit), the perceived lack of demand for wastewater infrastructure and unwillingness to contribute can also be related to the fact that the urban poor have more important priorities than wastewater removal.

- Relational advantages mediate land negotiations for retrofitting infrastructure in several ways. In the micro-scale exchange processes, relational advantages such as the relationship with authority holders (e.g., government officials and community leaders), alliances formed by social relations (with neighbours), social identity, and a sense of belonging to a community or group (social or ethnic groups), determine the dynamics in the practice of negotiation.

Similarly, access to capital—i.e., the availability of financial services offered by banks or saving groups, access to resources such as money and land with clear and exchangeable/transferable rights—impacts the negotiability of a unit of land in informal settlements. According to interviews with the RISE negotiation facilitators, in some cases, access to the resources also impacts the need for basic infrastructure and people’s willingness to cooperate in land negotiations for public infrastructure.

In addition to resource availability, access to the real estate market affects the negotiability of a unit of land in informal settlements. Better access to the real estate market can open alternative opportunities and impact the land negotiations for infrastructure where one or more of the following conditions is present.

- ○

- Selling opportunities obtained by rights-based advantages;

- ○

- Individual’s knowledge about the market;

- ○

- Other relational and spatial advantages such as the presence of a developer nearby who has an interest in the household’s land and available selling opportunities.

Consequently, people may resist any changes to their land if perceived to have a negative effect on their land value or transferability. These changes involve alterations in land-lot size or binding agreements that impose certain restrictions upon transferring land rights to others. Real estate market pressure can also discourage households from contributing land for infrastructure. The reason for this is no mystery. Based on the interviews with the RISE negotiation facilitators, where land-holding groups evince interest in the informal settlers’ land, the settlers fear losing their only secured asset, making them reluctant and wary of any changes that potentially influence their control over land. An example of this is observed where an improved pathway accommodating a pressure pod and pipes for a cluster remains blocked at the end and near a developer’s land to restrict the developer’s power and control over the space.

Based on the analysis results from the case study of six kampung communities in Makassar, as well as interviews with the RISE negotiation facilitators, four conditions can occur in a negotiation process, depending on the power and dependence dynamics. These results support Emerson’s (1962) theory of power relations. He refers to these conditions as ‘balancing operations’ that occur in response to the power imbalances in exchange relations [54].

- Withdrawal happens if the rights-holders put a low value on shared infrastructure or their social relations. According to the interview with the RISE negotiation facilitators, withdrawal is also observed in a few locations where some households do not possess enough land to contribute. Therefore, receiving the basic infrastructure and benefiting from the project depends on the land contribution from other households. Depending on the relationship between households, they may decide to withdraw from the project—for example, if the infrastructure provision requires defusing the enduring dispute and tension between neighbours.

- Status-giving in the RISE Project is seen where the household who has enough land for infrastructure finds higher values in cooperation with other neighbours and establishing a better relationship with them through contributing land for infrastructure.

- Social network extension can also be an alternative solution for balancing unequal power relationships in land negotiation processes, mainly where longstanding tensions and disputes exist among neighbours. In this case, the power-disadvantaged households seek out new relations with other neighbours who together can form a more stabilised servicing cluster. The instances of this situation are observed in several clusters in the RISE settlements where longstanding tension exists between the head of the RT unit’s family and other neighbours. The land negotiations in these circumstances are facilitated by changing cluster arrangements and forming better socially adjusted groups cooperating for shared infrastructure components. The potential for social network extension is closely associated with spatial and location-specific advantages. For example, the opportunities for rearranging clusters may be limited to a few neighbours living in the same alleyway.

- Coalition formation usually happens following the network extension by the power-disadvantaged households and rearranging clusters. In such a situation, the household that is left out (due to tension with others) has few alternatives for getting connected to the provided infrastructure. If the household possesses suitable land for infrastructure, they can contribute a part of their unoccupied private land for on-plot individual wetlands, septic tanks, and other infrastructure components, otherwise they will not benefit from the project. There are several examples in the RISE Project where the rights-holders have been able to keep their property self-contained and receive an individual, on-plot blackwater treatment infrastructure system. This situation often leads to a greater demand for private land contribution from households.

3.2.3. The Ability to Communicate

Within the case study area, several actors are (directly or indirectly) involved in the land negotiation processes for retrofitting infrastructure. These actors may compete, cooperate, or struggle for infrastructure benefits. The key actors include rights-holders (households), facilitators (the RISE local team), authority holders (including government officials and their representatives and community leaders), large land-holding groups, and developers. Except for the facilitators who have no personal interest in land, the other actors can simultaneously hold several social and relational positions at the settlement level and beyond the settlement boundaries. Likewise, their land interests and preferences can be dynamic and vary in different circumstances [17].

In a negotiation process, relevant stakeholders must have the opportunity to communicate with each other. In a tense situation where a longstanding dispute exists between different parties, establishing direct communication for negotiating land and decision making for the shared infrastructure’s location may not be viable. According to interviews with the RISE negotiation facilitators, effective communication can also be adversely affected by power asymmetries at various levels—i.e., from power inequality in small groups such as a family, household unit, or neighbours to the asymmetry of power between government agencies or large land-holding groups and informal settlers. Communication inefficiency can also be attributed to the existing social divide between actors. For example, division can exist between members of different administrative units belonging to different communities—Rukun Tetangga (RT) or community units and Rukun Warga (RW) or neighbourhood units. Religious tensions can also impact the ability to communicate in a negotiation process. Except for one settlement that reported some religious tensions in the past, most of the households in RISE settlements belong to similar religious and ethnic groups. However, a few instances of longstanding tension between the Buginese and Makassarese people (Muslim religious) and Torajans (mostly Christian) exist in several settlements that have impacted land negotiations and cluster formation.

As Leeuwis (2000) argues, there are multiple parallel communication channels and negotiation trajectories during the participatory negotiation process [25]. While land negotiations for public infrastructure can provoke other communications around land rights—e.g., land negotiations between a developer and households about selling opportunities that often occur in parallel—this paper only focuses on those land negotiations directly for the infrastructure. In line with Leeuwis’s research into the participatory negotiation approach in rural settings, and based on the analysis results from six kampung communities in the case study and interviews with the RISE negotiation facilitators, the main communication channels and negotiation trajectories in the RISE Project include:

- Direct land negotiation between different parties involving direct interactions and discussions about the exchanges between the households in the absence of negotiation facilitators and local team members. When facilitators are not present to mediate and assist the parties in reaching a satisfactory agreement peacefully, direct land negotiation between different parties can escalate into tension or conflict. The conflict situations are also reported for direct land negotiation between immediate family members who are not from the same household units (e.g., between parents and children).

- Negotiations between representatives and their constituencies involving negotiations between the representatives of parties—e.g., the head of a large family group, or the representative of a group such as servicing clusters—and local government representatives, including the head of RT/RW units, or in some cases, Lurah (sub-district head), or government agencies. A typical example of representatives at the cluster level is where parents and married children live on informally subdivided plots. According to the interview results and documented communications with households, often one person, for example, the son or the father, has more power in the decision making. This often relates to the family power structure or associates with being more knowledgeable.

In these negotiations, facilitators are present and have more power to coordinate the negotiations and use an active strategy to moderate the discussions for reaching an acceptable agreement. In addition, the facilitators’ presence helps resolve disagreements between parties during the negotiation process and aids power-disadvantaged parties/groups to sufficiently express their concerns.

- Direct land negotiation between facilitators (local team members) and different parties involving all the negotiations between facilitators with the rights-holders and households in the RISE settlements. Depending on the circumstances, facilitators may strategically hold separate meetings with selected parties, particularly where tension exists between them. This type of communication can occur individually (with a single household) or collectively (with more than one rights-holder). At the cluster and household levels, this communication channel is essential for negotiating land for critical infrastructure components. This type of negotiation enables facilitators to more actively raise the households’ awareness of the criticality of their contribution to system functionality and encourage private land contributions where no other alternative for locating infrastructure is available.

In addition to these communication channels, land negotiation can occur on several fronts: household/family-level negotiations; intra-cluster negotiations (between households in the same servicing cluster); settlement-level negotiations and inter-cluster negotiations; and project-level and administrative negotiations. These distinct levels of land negotiations are not necessarily sequenced and can occur in parallel.

4. Discussion: Land Negotiation Strategies for Community-Scale Infrastructure Retrofit Practices

Based on the results of the case study, the following strategies were identified for facilitating land negotiations with communities and rights-holders in the RISE Project. In contrast to the land negotiation and conflict resolution frameworks and tools often proposed in development studies’ literature and practice, we hesitated to formulate one-size-fits-all strategies for land negotiations, as the challenges and opportunities for land procurement for public infrastructure retrofit in each settlement are somewhat unique. Instead, the following are several strategies that proved effective for negotiating a unit of land for green infrastructure retrofit practice in an informal urban context.

4.1. Co-Design and Participation

Co-design workshops can provide important trust building and are beneficial at the outset of the process, as a preliminary activity before embarking on land negotiations. Such an approach enables the negotiation facilitators to gain insights into the existing dynamics and coordinate the land negotiation processes accordingly. The participatory workshops can follow a ‘joint fact-finding’ approach to improve local knowledge about the infrastructure in the earliest stages of the project. Joint fact-finding is the first step towards resolving the shared problem (here, finding a suitable location for infrastructure). Different parties gain access to a wide range of information through collaborative exploration of the problem at stake—i.e., here, the lack of access to infrastructure and the technical, spatial, and legal complexities of finding a suitable location for the infrastructure as well as the criticality of land contributions for system functionality. Therefore, community members are able to communicate and pursue their interests, and facilitators can take these findings into consideration later in negotiation to reach acceptable outcomes for all parties.

4.2. Working with Small Social Units or Clusters

As discussed previously, the technical requirements of the pressure sewer system in the RISE model entails forming servicing groups or ‘clusters’. These clusters are formed based on social considerations (typically kinship) and spatial considerations, and involve up to 7 households or 45 people. Cluster formation proved valuable in working with socially coherent groups to facilitate land negotiations and manage existing tensions and conflicts by placing people with close social relations in the same group. Cluster members often cooperated towards a common goal—i.e., addressing the shared infrastructure problem, the collaborative exploration of issues and solutions such as infrastructure location, land contribution options, and different types of land agreements. These collaborations provided cluster members with a sense of common purpose [55]. Forming servicing clusters also aided with managing and navigating the social dynamics and relations in a community. Where conflict and power asymmetries existed in a cluster, people often sought to form coalitions with other neighbours. If spatial circumstances allowed, clusters could be strategically rearranged to avoid tense negotiation situations and facilitate contributions (exchange interactions). Forming servicing clusters also aided with managing the exchange network size and controlling the dynamics and relations in land negotiations. Cook and colleagues (2013) highlight the potential for ‘coordination problems’ when the exchange network expands and involves more people in negotiations and decision-making processes [35].

4.3. Moderating Social Interactions through Strategic Selection of Participants in Sensitive Situations

As previously stated, in a tense situation where a longstanding dispute exists between different parties, establishing direct communication for land negotiation and decision making for the shared infrastructure’s location may not be viable. Careful selection of participants in land negotiation meetings is of great importance in managing existing tensions and preventing conflict. In this sense, individual meetings with households aid in creating a safe environment for negotiating land rights. Such individual meetings do not imply inclusion or exclusion of rights-holders from the negotiation process; rather, they enable minimising the risk of creating tension during the land negotiation processes.

4.4. Infrastructure as a Tool for Formalising Land Boundaries

Where spatial circumstances allow, wastewater infrastructure components such as wetlands can be positioned along the unmarked borders with public roads, neighbouring plots, or a developer’s land. Establishing more precise physical boundaries through these spatial readjustments can help resolve existing tensions between the rights-holders and subsequently facilitate future land regularisation.

4.5. Infrastructure Upgrades as an ‘Acupunctural’ Strategy

In this approach, existing publicly used (vs. publicly owned) land resources are recognised and used to minimise the land use alteration and land tenure conversion. This includes embracing shared used rights (existing exchange relations) within the existing semi-public and semi-private pathways and redirecting land negotiations for utilising these spaces for the new infrastructure components. Likewise, an acupunctural strategy can use leftover, low-quality spaces instead of high-quality land of households—land that is often subjected to incremental alterations and the expansion of dwellings. Overall, an acupunctural strategy can be viewed as a vehicle to facilitate land negotiations through combining the households’ first-priority needs (such as improved access and upgraded pathways) with the second-priority needs (such as wastewater treatment infrastructure).

4.6. Accepting Land Boundary Uncertainties and Prioritising Negotiation Approaches over Conventional Land Surveying

Unclear boundaries between private plots and between public and private land make mapping land ownership and land use rights in informal settlements difficult. Conventional land surveying processes often trigger tension and conflict before initiating the land negotiations for public infrastructure, causing additional challenges for infrastructure location decision making. Accepting land boundary uncertainties and adopting a flexible approach to boundary demarcation in the early stages of a project can avert avoidable conflict situations.

5. Conclusions

Location decision making and land procurement for public infrastructure raise the complex questions of who has the right to occupy, control, and use a piece of land in informal settlements and how the land, that is often held under uncertain arrangements, can be acquired for infrastructure upgrades [51]. In land negotiation processes, households usually need to negotiate for multiple concerns and purposes simultaneously: infrastructure location and minimising the upgrading project’s unintended consequences—e.g., restraint concerning future construction opportunities, transformation of the semi-private alleyways to public roads, unpleasant smell, disturbing changes in land use and land ownership rights, challenging cluster dynamics, and compensation and land procurement arrangements. These concerns and the ways in which they are negotiated together determine the household’s gains, contributions, and the extent to which the household’s agency over the land is protected.

By employing negotiation theory [25,42] and by engaging with a live infrastructure retrofit project, we analysed the fundamental conditions—i.e., the divergence of interests, mutual interdependence between stakeholders, and the ability to communicate—that allow for the negotiability of a unit of land for public infrastructure in informal settlements. Accordingly, we provided insight into the on-the-ground realities of land negotiation in a multi-layered and complex land tenure system where different interests coexist in a single unit of land.

These findings and the identified strategies for addressing challenges in land negotiation for public infrastructure upgrades are not ‘one-size-fits-all’ solutions and the overall feasibility of projects depends on a complex mix of interrelated legal, spatial, social, and economic factors. Instead, we aimed to capture the fundamental conditions for land negotiations with rights-holders and to explore how the micro-scale social and spatial aspects of land tension and land negotiation (tenure, conflict, space) for community-scale infrastructure projects may interact. We also would like to add a qualifying note that the relatively small sample size for this analysis makes these findings partial and that a larger sample would have to be analysed to have more conclusive and generalisable findings.

We conclude by highlighting the need for more flexible and context-specific forms of land negotiation strategies to manage the interactions between different rights-holders and those with interests in the land during the infrastructure retrofit practices. These alternative forms of negotiation assist with circumventing the unintended consequences in the land negotiation processes. Some of the land negotiation strategies developed in the RISE Project are attributed to the advantages of the nature-based infrastructure provision model. For instance, as outlined above, cluster formation proved to be a valuable tool for working with socially coherent groups to facilitate land negotiations in a safe environment. Cluster formation appeared effective at managing existing tensions and conflicts by placing people with close social relations in the same group and controlling the exchange network size.

The identified negotiation strategies can be adapted for other community-scale infrastructure retrofit projects (e.g., neighbourhood roads, water and sanitation infrastructure). These strategies can be employed in any stage of the negotiation process, while some negotiation tasks can become more important as the negotiation process moves forward. A nonlinear negotiation process appeared effective at addressing the uncertainties associated with the changes in the approaches, policies, rules, and regulations of the project donors or government and the mismatch between administrative preferences and procedures. Future research should analyse the uncertainties caused by the constantly changing policies and regulations enforced by international donors and local government agencies as these play a significant role in the implementation feasibility or alteration of any negotiated agreement made with rights-holders.

In light of findings on land negotiation processes, several research questions can guide future studies: How land negotiation dynamics and patterns are different for each land procurement mechanism—e.g., the utilisation of public land, the procurement of households’ private land, or other available opportunities near these settlements? What is the role of household composition, age, gender, socio-economic conditions, social connections, and family relations, and cultural, ethnic, and religious considerations in land negotiations for public infrastructure?

Many successful land negotiation examples and households’ participation and land contributions in the RISE Project demonstrate positive developments in these communities and depict a promising future for expanding wastewater treatment infrastructure to informal settlements and improving the environmental condition, human health, wellbeing, and resilience of these communities. These concerns are far more critical now as the little progress towards ‘clean water and sanitation for all’ (SDG 6) has been stopped in its tracks due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the new challenges faced by Global South cities in a post-pandemic era.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.M.; Methodology, M.M.; Formal Analysis, M.M.; Data Curation, M.M.; Original Draft Preparation, M.M.; Review and Editing, M.M. and D.R.-L.; Visualisation, M.M.; Supervision, D.R.-L. and M.E.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Monash University Departmental Scholarships (MDS) and Revitalization of Informal Settlements and their Environment (RISE Ph.D. scholarship). The authors also acknowledge the funding received through Monash University Postgraduate Publications Award (PPA).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project Number: 9396; 25 March 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This paper is derived in part from broader Ph.D. research by the first author at Monash University. The authors wish to thank all the RISE local team members in Indonesia and our informants for their time and dedication to share information and patiently respond to our questions. The analysis, conclusions and recommendations of this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the RISE Program and our funders. The authors would also like to thank anonymous reviewers and Academic Editor for their time, insightful suggestions and constructive comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Eisenberg, M.A. Private Ordering through Negotiation: Dispute-Settlement and Rulemaking. Harv. Law Rev. 1976, 89, 637–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barry, M.B.; Dewar, D.; Whittal, J.F.; Muzondo, I.F. Land Conflicts in Informal Settlements: Wallacedene in Cape Town, South Africa. Urban Forum 2007, 18, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, D.; Fricska, S.; Wehrmann, B. Towards Improved Land Governance; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2009; Volume 781. [Google Scholar]

- Borras, S.M., Jr.; Franco, J.C. Contemporary Discourses and Contestations around Pro-Poor Land Policies and Land Governance. J. Agrar. Chang. 2010, 10, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M.; Rakodi, C. Urban Land Conflict in the Global South: Towards an Analytical Framework. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 2683–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Awakul, P.; Ogunlana, S.O. The Effect of Attitudinal Differences on Interface Conflicts in Large Scale Construction Projects: A Case Study. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2002, 20, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magsi, H.; Torre, A. Proximity Analysis of Inefficient Practices and Socio-Spatial Negligence: Evidence, Evaluations and Recommendations Drawn from the Construction of Chotiari Reservoir in Pakistan. Land Use Policy 2014, 36, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, A.; Pham, V.H.; Simon, A. The Ex-Ante Impact of Conflict over Infrastructure Settings on Residential Property Values: The Case of Paris’s Suburban Zones. Urban Stud. (Edinb. Scotl.) 2015, 52, 2404–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magsi, H.; Torre, A.; Liu, Y.; Sheikh, M.J. Land Use Conflicts in the Developing Countries: Proximate Driving Forces and Preventive Measures. PDR 2017, 56, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UN-Habitat. Land and Conflict: A Handbook for Humanitarians; United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat): Nairobi, Kenya, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, J.W.; Holt, S. Land and Conflict Prevention; Conflict Prevention Handbook Series; Initiative on Quiet Diplomacy (IQd); University of Essex: Colchester, UK, 2011; p. 146. [Google Scholar]

- Wehrmann, B. Understanding, Preventing and Solving Land Conflicts; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH: Eschborn, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Land and Conflict Lessons from the Field on Conflict Sensitive Land Governance and Peacebuilding; United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat): Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; p. 141. [Google Scholar]

- Torre, A.; Melot, R.; Magsi, H.; Bossuet, L.; Cadoret, A.; Caron, A.; Darly, S.; Jeanneaux, P.; Kirat, T.; Pham, H.V.; et al. Identifying and Measuring Land-Use and Proximity Conflicts: Methods and Identification. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombard, M. Land Tenure and Urban Conflict: A Review of the Literature; GURC Working Paper Series; University of Manchester; Global Urban Research Centre: Manchester, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Quizon, A.; Pagsanghan, J.; Don Marquez, N. Defense of Land Rights: A Monitoring Report on Land Conflicts in Six Asian Countries; Asian NGO Coalition for Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ANGOC): Quezon City, Philippines, 2019; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, N.; Bojsen, K.P.M. Negotiability and Limits to Negotiability—Land Use Strategies in the SALCRA Batang Ai Resettlement Scheme, Sarawak, East Malaysia. Geogr. Tidsskr. Dan. J. Geogr. 2005, 105, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribot, J.C.; Peluso, N.L. A Theory of Access. Rural Sociol. 2003, 68, 153–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnaud, C.; Le Page, C.; Dumrongrojwatthana, P.; Trébuil, G. Spatial Representations Are Not Neutral: Lessons from a Participatory Agent-Based Modelling Process in a Land-Use Conflict. Environ. Model. Softw. 2013, 45, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnaud, C.; Van Paassen, A. Equity, Power Games, and Legitimacy: Dilemmas of Participatory Natural Resource Management. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, G.; Wallwork, J. Enabling Effective Participation, Negotiation, Conflict Resolution and Advocacy in Participatory Research: Tools and Approaches for Extension Professionals. 2003. Available online: http://www.regional.org.au/au/apen/2003/refereed/083leachgwallworkj.htm (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Muro, M.; Jeffrey, P. Time to Talk? How the Structure of Dialog Processes Shapes Stakeholder Learning in Participatory Water Resources Management. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Meegeren, R.; Leeuwis, C. Towards an interactive design methodology: Guidelines for communication. In Integral Design: Innovation in Agriculture and Resource Management; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara, K. Cohesion, Cooperation, and the Value of Doing Things Together: How Economic Exchange Creates Relational Bonds. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2011, 76, 560–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeuwis, C. Reconceptualizing Participation for Sustainable Rural Development: Towards a Negotiation Approach. Dev. Chang. 2000, 31, 931–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Lovering, D.; Prescott, M.F.; Josey, B.; Mesgar, M.; Spasojevic, D.; Wolff, E. Operationalising Research: Embedded PhDs in Transdisciplinary, Action Research Projects. In The PhD at the End of the World: Provocations for the Doctorate and a Future Contested; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume 4, pp. 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Lovering, D.; Zamudio, R.M.; Arifin, H.S.; Kaswanto, R.L.; Simarmata, H.A.; Marthanty, D.R.; Farrelly, M.; Fowdar, H.; Gunn, A.; Holden, J. Pulo Geulis Revitalisation 2045: Urban Design and Implementation Roadmap; Australian-Indonesia Centre (AIC): Melbourne, Australia, 2019; p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanakis, A. The Role of Constructed Wetlands as Green Infrastructure for Sustainable Urban Water Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramirez-Lovering, D.; Prescott, M.; Kamalipour, H. RISE: A Case Study for Design Research in Informal Settlement Revitalisation Interdisciplinary Design Research in Informal Settlements; The University of Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2018; pp. 461–478. [Google Scholar]

- RISE Asian Development Bank. Water Sensitive Informal Settlement Upgrading: Overall Principles and Approach; ADB and Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; ISBN 1-4462-0040-X. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 1-5063-3019-3. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, A.; Durepos, G.; Wiebe, E. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, K.S.; Cheshire, C.; Rice, E.R.; Nakagawa, S. Social exchange theory. In Handbook of Social Psychology; DeLamater, J., Ward, A., Eds.; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 61–88. [Google Scholar]

- Poteete, A.R.; Janssen, M.A.; Ostrom, E. Working Together: Collective Action, the Commons, and Multiple Methods in Practice; STU-Student edition; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, M.B.; McDonald, G. Community-Based Environmental Planning: Operational Dilemmas, Planning Principles and Possible Remedies. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2005, 48, 709–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, G. Realizing the Right to Sanitation in Deprived Urban Communities: Meeting the Challenges of Collective Action, Coproduction, Affordability, and Housing Tenure. World Dev. 2015, 68, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McGranahan, G.; Mitlin, D. Learning from Sustained Success: How Community-Driven Initiatives to Improve Urban Sanitation Can Meet the Challenges. World Dev. 2016, 87, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrington, D.J.; Sridharan, S.; Saunders, S.G.; Souter, R.T.; Bartram, J.; Shields, K.F.; Meo, S.; Kearton, A.; Hughes, R.K. Improving Community Health through Marketing Exchanges: A Participatory Action Research Study on Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Three Melanesian Countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 171, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducrot, R.; van Paassen, A.; Barban, V.; Daré, W.; Gramaglia, C. Learning Integrative Negotiation to Manage Complex Environmental Issues: Example of a Gaming Approach in the Peri-Urban Catchment of São Paulo, Brazil. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2015, 15, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mastenbroek, W.F.G. Negotiating: A Conceptual Model. Group Organ. Stud. 1980, 5, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovey, K.; King, R. Forms of Informality: Morphology and Visibility of Informal Settlements. Built Environ. 2011, 37, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, P. Pacific Urbanisation and the Rise of Informal Settlements: Trends and Implications from Port Moresby. Urban Policy Res. 2012, 30, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. Housing Resilience and the Informal City. J. Reg. City Plan. 2017, 28, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mukhija, V. Upgrading Housing Settlements in Developing Countries. Cities 2001, 18, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Lotia, H.; Malik, A.A.; Mundt, M.D.; Lee, H.; Rafiq, M.A. Gendered Impacts of Environmental Degradation in Informal Settlements: A Comparative Analysis and Policy Implications for India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 2020, 23, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekesa, B.W.; Steyn, G.S.; (Fred) Otieno, F.A.O. A Review of Physical and Socio-Economic Characteristics and Intervention Approaches of Informal Settlements. Habitat. Int. 2011, 35, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinzen-Dick, R.; Mwangi, E. Cutting the Web of Interests: Pitfalls of Formalizing Property Rights. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Land Tenure and Rural Development; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2002; ISBN 92-5-104846-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mesgar, M.; Ramirez-Lovering, D. Informal Land Rights and Infrastructure Retrofit: A Typology of Land Rights in Informal Settlements. Land 2021, 10, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Benda-Beckmann, F.; von Benda-Beckmann, K.; Wiber, M.G. The Properties of Property. In Changing Properties of Property; von Benda-Beckmann, F., von Benda-Beckmann, K., Wiber, M.G., Eds.; Berghahn Books: New York City, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–39. ISBN 978-1-84545-727-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, J.Z.; Brown, B.R. Interdependence. In The Social Psychology of Bargaining and Negotiation; Rubin, J.Z., Brown, B.R., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1975; pp. 197–258. ISBN 978-0-12-601250-7. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, R.M. Power Dependence Relations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1962, 27, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lawler, E.J.; Thye, S.R.; Yoon, J. Social Exchange and Micro Social Order. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2008, 73, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).