1. Introduction

The changes taking place in the production system foster the transformation of its spatial organization. This occurs as a result of changes in the social division of labor and external advantages, greater flexibility of the labor market, as well as stronger correlations between the industry and the local socio-economic conditions. As a result, the undying prerequisites for the location of contemporary economy are transformed, and new industrial clusters and location trends are formed. New industrial locations are often multicenter and less concentrated, and industrial development is firmly rooted in local socio-economic conditions. In the post-industrial era, the escalating costs involved in the functioning of cities, scientific and technical progress, a steady increase in the level of population education, and numerous environmental barriers contributed to the decentralization of economic activities. The increasing appeal of suburban zones as locations for businesses, but also the transformation of the inner-city industrial structures, are one of many consequences of this phenomenon [

1,

2,

3].

This study is focused on cities, specifically on the inner-city structures, and is based on several theoretical considerations, which suggest that cities should provide amenities that attract the most qualified people [

4], in particular professionals highly sought after by high-tech businesses. These units are associated with the high availability of specialized suppliers and customers [

5]. The transport and transaction costs are lower [

5], and the cities offer more opportunities for networking and developing social connections [

6]. These units are generally areas of concentrated specialized and skilled labor [

7,

8].

Industrial concentration and specialization are also accompanied by structural changes [

9,

10,

11,

12].

These changes are primarily driven by the development of science and technology. Hence, the emblematic feature of any economy is its structure providing a measure of the degree of advancement of its products and applied technologies, which depends on and reflects the intensity of research and development.

Innovation, knowledge transfer and the use of knowledge are the core factors determining the pace of this progress and the high level of economic development. A growth in innovation and the deployment of new or significantly improved products or advanced technological processes contribute to a more complete use of the existing resources, as well as better economic performance [

13,

14].

The aim of this study was to demonstrate spatial diversity, changes taking place in the spatial structure, and to assess the degree of advancement of contemporary processes of industry concentration and specialization according to R&D intensity in the agglomeration area of Wrocław and the suburban zone. According to empirical literature, the economy of an agglomeration (Wrocław) is an important pull factor for new high-tech businesses, as these companies tend to benefit from efficiency gains in central and highly agglomerated areas [

15]. In theory, the economy of an agglomeration benefits from sharing, matching, and learning when companies are located close together [

16].

According to this research hypothesis, there is a polarization in the industry concentration and specialization in the city itself and in the suburbs. This study concerns a large urban center—the city of Wrocław—located in post-socialist Poland.

The choice of Wrocław and its suburbs as a research area was not accidental. The branch diversity of Wrocław industry, long-term and early developed industrialization, intense organizational changes, forms of ownership of economic entities, the phenomenon of large enterprises breaking up into smaller units, and an intense inflow of foreign direct investment to the city’s industry, as well as great interest in the location of high-tech enterprises in the city allow for a fuller understanding of concentration processes and industry specialization on the basis of the indicated agglomeration. The changes in industrial activity that took place in Wrocław and its suburbs are analogous to those of other large post-socialist cities in Poland and Central and Eastern Europe.

The location of industrial activity in this area is characterized by both infiltration of industrial operators from the city center to the surrounding vicinity and new industrial locations emerging in the vicinity of a large city. Therefore, it covers both newly established and relocated industrial facilities. This process is selective and contributes to the growing functional specialization in the suburban zone. In the vicinity of the city, in industrial areas, there is also a diversification of industrial activities in terms of the level of technological advancement, depending on the distance from the central center. High-tech companies benefit from the economy of urban agglomerations [

8], and it can be concluded that these benefits are not evenly distributed within the city areas—given that the spatial range of an agglomeration significantly decreases with the distance from the center—and are concentrated in sub-centers [

17], which explains why it is important to use smaller districts as research units.

The study focuses mainly on the spatial regularities of the contemporary processes of industrial location in the city and its suburbs. These processes taking place in the cities of post-socialist states proceed in a diversified manner, which bear similarities to the patterns typical for the cities of the Western world [

18,

19,

20], but are also specific [

21,

22]. The results of the research in the area of the Wrocław agglomeration indicate that the processes of concentration and specialization and the spatial infiltration of industry in this part of Europe in metropolitan areas are more complex, selective, and not as expressive as in Western European countries. Therefore, the study fills a clear gap in the empirical literature by carrying out an analysis that takes into account several dimensions, such as the inner-urban research area and industry according to the intensity of research and development, as well as its concentration and spatial specialization.

2. Literature Background

Economic models originating from the theory of growth, trade, and economic geography indicate that the determinants of economic concentration and specialization are very diverse [

23,

24,

25]. On the one hand, due to comparative advantage and the existing resources, an increase in sectoral specialization of individual economies and regions is expected [

1]. On the other hand, the existing theories of growth point to a decline in specialization resulting from the equalization of labor and capital productivity [

26,

27].

Specialization of industrial production closely depends on the degree of concentration and scale of production. The scale of production must be large enough before it can be divided into the production of specific products. Production specialization then leads to its further concentration. These processes are closely intertwined.

As a result, the concentration and specialization of industrial production should generate various benefits for the national economy: an increase in production and labor productivity, an improvement in production quality, reduced production costs, and increased profitability. This is why it is so important to identify the processes of production specialization that enables an assessment of its effective performance [

28].

Concentration and specialization are also conducive to spatial divisions at different scales. Factors differentiating the dynamics of industrial development in the Polish regions include a diversified availability of qualified staff, transport accessibility, or proximity to sales markets.

The concentration of specialized production stimulates the deepening of links between production and supply, strengthens the interdependence between the distribution of individual industries, and leads to the functional division of space [

29,

30].

Specialization coupled with concentration may result in a more rational territorial distribution of production processes while eliminating the fragmentation of suppliers of components and parts. It may at the same time induce an increase in these costs as a result of a longer distance between enterprises and recipients. Therefore, the spatial distribution of individual industries depends on the degree of their concentration and the increase in production volumes of the businesses concerned. Hence, the concentration of specialized production has an impact on the deepening of relationships between production and supply in these areas. As a result, production specialization leads to its further concentration, or wider cooperation between co-existing or closely located enterprises. The spatial proximity between similar businesses is, therefore, an important source of competitiveness, especially for high-tech industries, as they require face-to-face interaction to exchange complex and tacit knowledge [

3,

31].

Sectoral complementarity in the system of spatial units within the city is the outcome of the abovementioned processes. This phenomenon is also illustrated by the spatial distribution of industrial activity in the city districts of Wrocław. It happens under suitable conditions, which include increasing the technical level of production, improving the technology of production processes, or an appropriate level of specialization [

32].

These business operate in the conditions of constant change. Local conditions that are important from the point of view of running a business, the relevant legal regulations, and consumer preferences in terms of the demand for specific products are changing. The manufacturing process also changes over time in response to technological progress. Enterprises must constantly adapt to these dynamic conditions to maintain profitability. This adaptation also has a spatial dimension [

33]. This is largely manifested by relocations of businesses. These processes are particularly common in metropolitan areas. The concentration of intellectual potential, capital, the proximity of goods and services important for running a business, and a number of other benefits resulting from the location of business in an agglomeration make this location very popular among investors. They often focus on areas with special investment zones, created with the participation and involvement of local authorities in order to strengthen the local economy. Metropolitan areas is also where many businesses are incubated, at least from some specific industries, which was already underlined in the incubator theory in the 60s and 70s [

18].

Geographical differences in production costs often have an impact on the relocation of industry. Industrial production diffuses (“infiltrates”) down the hierarchical system of cities, from larger to smaller localities. Industrial dispersion can be traced back to an increase in labor costs, as well as the emergence of development thresholds in large urban agglomerations [

34,

35,

36]. If this growth exceeds the benefits of agglomeration obtained by businesses, they must relocate their activities in whole or in part to areas where there are opportunities to reduce costs. Such areas may be suburban zones of large metropolises [

37]. This process is also linked to the product life cycle [

38,

39].

In recent years, the rising costs of congestion in large urban centers, deterioration of amenities, and rising wage levels have led to increasing migration of manufacturing activities from metropolitan centers to more peripheral areas. Enterprises are also subject to this process, just as population is, mainly in the production and service sectors [

40]. The reasons for production relocation are more complex. The main motive for relocating production is basically the desire to reduce production costs and increase flexibility. The basic determinants in relocating production include: the level of labor costs, quality and qualifications of human resources, infrastructure, proximity to supply and sales markets, or legal and institutional setting [

41]. Hence, the contemporary trends on the location of industrial activity indicate that suburbanization processes are interlinked with the tendency to relocate industrial plants to the suburban zone, especially large cities [

2]. This phenomenon induces significant changes not only in the spatial industrial structures in the region, but also in inner-city systems.

The processes of suburbanization as well as the emerging economic or specifically industrial activity in these areas can be seen in the vicinity of many urban centers. Each city undergoes specific industrial restructuring, depending on the city’s historical background, economic base, and the quality of the socio-cultural environment [

42].

The development of the suburban zone and, thus, its appeal as a location for the industrial activity are inextricably linked with the size and level of development of the city, its functions and location both in the settlement system, infrastructural layouts, and socio-economic structures [

34,

43,

44].

The center of a metropolis determines the growth of adjacent or more distant satellite cities and non-urbanized areas. If the growth of an urban region is rapid and wave shaped, it may propagate unevenly across the region. This gives rise to an uneven distribution of jobs, which may result in the development of functional specialization in individual units of the suburban zone [

45].

The attractiveness of a suburban zone as a location for business also depends on the quality of the local economic resources. The quality of these resources can either stimulate or inhibit the development of the suburban zone [

46,

47].

The strategy for locating industrial activity and the desire to maximize the value of land rent are seen as the drivers of zonal development of cities [

39,

48,

49]. Land rent varies across different locations, i.e., it decreases with distance from the center. The price of land is also influenced by the land use, the degree of investment, topographic and water-ground conditions, and the proximity to power sources and other facilities. Another component of industrial environment in the suburban zone are human resources consisting of people and their qualifications. The diversity of these resources results from objective reasons such as place of residence, demographic and social differences (sex, age, social origin, etc.), and vocational orientation. The established levels of wages across a labor market reflect the labor costs [

36,

46].

A suburban zone is, therefore, characterized by a favorable environment for industrial activity, including innovative ones, but at the same time, it must incorporate the abovementioned factors that make it more appealing.

Traditionally, high-tech businesses were located in city cores in search of specialized services, human capital, and knowledge flows offered by these areas, and it is known that peripheral areas are not competitive enough to attract and/or generate such companies [

50]. However, the recent processes of suburbanization may change this pattern as the monocentric distribution of economic activity is shifting towards a polycentric one [

51].

As soon as disadvantages of the agglomeration’s central unit become evident, prospective investors become more interested in the suburban zone. Due to the proximity and economic functions of the center, there is no need to develop the so-called environment for business, as it already exists in the center.

Reasons for the relocation of industrial activity are, therefore, complex and contingent on many factors specific for a company and its environment. The main motive for relocating production is basically the desire to reduce production costs and increase flexibility. This phenomenon is, therefore, also closely correlated with the flows of foreign direct investment, which have a very significant impact on the contemporary spatial structure of the industry in many post-socialist countries [

52]. Therefore, technology companies (both in the production and service sector) are located more often in the suburbs than in urban cores in highly developed countries such as the United States, where suburbanization began much earlier [

53], and the question arises whether the post-socialist countries have their own specificity, especially from the European perspective, where the cores of large metropolitan areas still attract high-tech companies. Furthermore, the suburbanization processes have a far shorter history here and often progress very rapidly, and in some metropolises (Barcelona), traditional cores slowly move to the outskirts [

3].

3. Methods and Data Sources

The location of industrial activity was analyzed on the basis of the industry operators registered in section C (industrial processing) of the Polish Classification of Activities (PKA) in the REGON (statistical identification number for businesses) database of 2008 and 2016. The industry’s spatial structures reflect the classification of industrial processing according to R&D intensity broken down into high-, medium-high-, medium-low-, and low-tech sectors. In line with methodological recommendations for high-tech statistical research coordinated by the OECD. The OECD currently uses industrial classifications based on analyzes of the contents of the R&D component, also known as technology-based classifications of industries [

54].

The analysis was based on Wrocław’s spatial division into city districts (48 units). This division reflects Resolution No. XX/419/16 of the Wrocław City Council of 21 January 2016 on the division of Wrocław into city districts.

The source of the statistical data used in the study is the local data bank of the Central Statistical Office in Poland.

Maps showing the spatial distribution of statistical data were made in Map Viewer 7.0.

The suburban zone of Wrocław was determined on the basis of commuting patterns (the city is the main labor market in the region; hence its impact zone is extensive) covering two rings of municipalities around the city.

Quantitative methods were used to identify the degree of concentration and spatial specialization of industrial activity. The underlying analytical statistics included relative indicators (the location quotient (LQ), Florence’s location quotient, or the Krugman Specialization Index), as well as analyses of market structures (Herfindahl–Hirschman index or discrete index).

The degree of advancement and the level of spatial differentiation in the process of industrial concentration were analyzed using the location quotient (LQ). This indicator is a measure of the concentration of activities in the area studied in relation to a reference area [

55]. The city of Wrocław was the reference area in the analysis.

The spatial structure of Wrocław’s industry was assessed using Florence’s location quotient, also known as the concentration index. It is designed to assess the proportionality of the spatial distribution of a phenomenon in relation to another element that serves as a comparator [

56]. It determines the conformity of the spatial distribution of two events in a regional system. As regards the industrial activity, it is calculated according to the formula:

where

,

= number of residential districts, where:

—the percentage share of a residential district j in the number of industry operators of the i-th category established in the city;

—the percentage share of a residential district j in the total number of industry operators established in the city.

The indicator values vary from 0 (complete dispersion) to 1 (complete concentration of the phenomenon).

The Krugman Specialization Index used in this study is the sum of absolute differences between the sectoral shares of a phenomenon in a given unit versus the total value and the sectoral shares of a phenomenon in the total value specific for the reference area, i.e., the city of Wrocław. It determines the degree to which a local structure of the examined unit (e.g., a residential district) differs from the structure of the reference area (city). A variant of the Krugman regional specialization index is expressed by the following formulas [

57]:

—unit number and s—sector number;

—value of the variable in the i-th sector in the r-th unit;

—value in all sectors in the r-th unit;

—value of the variable in the i-th sector in the reference area;

—value in all sectors of the reference area.

This study also uses the Herfindahl–Hirschman index (HHI), which allows us to compactly express the features being analyzed [

58]. It is calculated as the sum of squared shares of all spatial units in the studied region and is expressed by the formula:

where:

—denotes the share of the feature being analyzed in the total value.

The index value ranges from close to zero for dispersed features to 10,000 for highly concentrated features. In practice, a value of less than 1000 means a low concentration, more than 1800 denotes a high concentration, and above 2500 means that the phenomenon is highly concentrated in space [

58]. The study also uses a discrete indicator that is also often used to assess the degree of concentration of a phenomenon [

59].

The choice of N is arbitrary and depends on the purpose of the study and the number of units in a given area [

60].

4. Results

4.1. Wrocław as an Industrial Center

Wrocław is an important industrial center of Poland, located in the south-western part of the country, the capital of the Lower Silesian Voivodeship, and the main city of the Wrocław industrial district. It is characterized by a highly developed processing industry. This city is a historical and important political, administrative, economic, cultural, research, and transport center, which required a well-developed manufacturing sector to meet the needs of its inhabitants, initially provided by craftsmanship and, later, by the industry [

61]. The origin of the Wrocław industrial center is typically urban.

The diversity of industrial activity in Wrocław can be attributed to the strong links with the well-established raw material base of the Sudetes, long-term and early developed economic activity, post-war decisions to support quick industry development, and modernization, as well as the establishment of new production facilities [

61]. The latter trend was fueled by the influx of highly qualified technical staff from the Wrocław research and academic institutions.

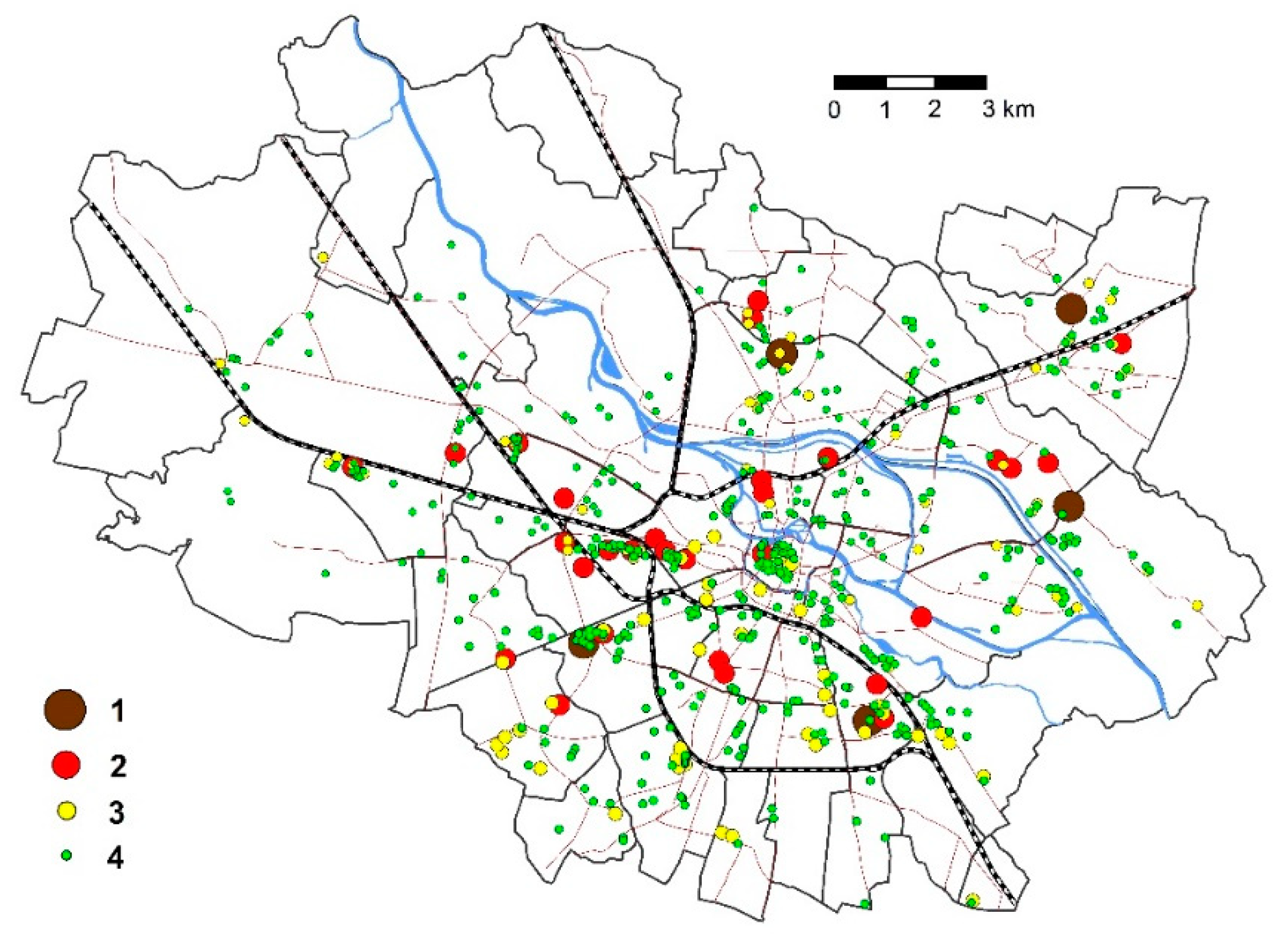

A convenient location at the crossroads of important transport routes between the main economic centers in Poland and internationally attracts new industrial operators to the city. Important transport corridors from the west to the east and from the north to the south intersect in Wrocław. This is particularly evident in the spatial distribution of the city’s industrial facilities located along the main communication routes (

Figure 1). Wrocław’s location near the German and Czech borders also plays an important role, as it offers significant advantages for the industry.

Industrial facilities are integrated into downtown areas, which is a characteristic feature of Wrocław. This specifically involves smaller operators with a work force of up to 250 employees. This is partly a result of the city’s enlargement and spatial expansion into new areas. Larger industrial operators, especially those with large cubature and employing over 1000 people, are commonly located in peripheral residential districts, along the exit directions of the main communication arteries.

The spatial distribution of industrial activity in Wrocław is shaped into concentration zones, whose location conditions are crucially determined by the aforementioned communication system, both internal and external. The industrial zones are concentrated along the main transit road and rail routes, as well as along the Odra water route offering easy access to water supplies. The specific spatial distribution of industrial activity in Wrocław allowed for relatively easy and fast transport of raw materials and semi-finished products, the development of cooperation as well as technical and technological advantages between individual plants and industries.

Under such conditions that prevailed in the 1970s and 1980s, after a period of growing concentration of the industry, the processes of its deglomeration began. It was manifested by the creation of branches of industrial plants mainly in the satellite cities of Wrocław. These cities are also located along the main transit routes from Wrocław, alongside the industrial concentration zones created over the years, strengthened by numerous economic subzones that emerged during the transformation period.

After 1989, as a result of crucial systemic changes in the Polish economy, new economic phenomena resulting from transformation processes and emerging in Wrocław’s industry included changes in forms of ownership of economic operators and the division of large enterprises into smaller units that enjoyed considerable production, financial as well as organizational and managemental independence. This process was accompanied by significant spatial relocation of the industrial activity within the urban system, which resulted in functional, morphological, and social changes in the formerly industrial areas. As a result, new transformed post-industrial areas were emerging in the city, which were gradually occupied by new businesses, mainly services and trade [

62]. This process continues to this day.

The present-day distribution of industrial activity in the city is spatially diversified. As measured by the number of industry operators per 1 square kilometer of the city area, the highest concentration of industrial activity is reported in the central area of Wrocław with a clearly marked southern and north-western area (

Figure 2).

There were nearly 400 industry operators in the Stare Miasto [Old City] district. There were early 200 economic operators in the residential districts in the vicinity of the Old Town—Przedmieście Świdnickie, Plac Grunwaldzki, Ołbin, and Huby. Generally, a greater concentration of industry operators was present in the eastern part of Wrocław, which largely resulted from the historical ties with the industry of Upper Silesia and the internal communication system in the city.

The intensity of spatial distribution of industrial activity in Wrocław shifts towards the periphery of the city. It is characteristic not only for many Western European and North American cities [

63,

64], but also for the cities of Central and Eastern Europe (Prague, Budapest, or Brno) [

22,

65]. The share of industrial operators in total number of businesses depending on their distance from the city center varies considerably (

Figure 3).

The largest share (up to 16%) was primarily within 1–2 km from the center and, then, within a radius of 4–5 km. This spatial distribution of industrial activity is clearly correlated with the spatial expansion of the territory of Wrocław, as manifested by the ensuing clearly lower share of industrial operators within 6–7 km from the center, which then stabilizes at 2% at a distance of more than 10 km.

However, the shifting of industrial activity towards peripheries can be attributed to complex conditions. The advantages of agglomeration generally stimulate the concentration of economic activity. The high intensity and considerable variety of economic activity within a city contribute to the emergence of complementarity and substitution effects, which might be explained by the benefits of urbanization. However, these advantages apply in cities up to a certain size, after which they turn into disadvantages. Excessive growth of industrial activity, accompanied by an increasing population concentration, may bring about negative effects (ineffective communication systems and municipal facilities, lack of free space, or deterioration of the quality of the environment), which result in deglomeration processes. Moving production to other areas is a natural response of business to changes in the operating conditions. On a global scale, this phenomenon is associated with a more efficient allocation of resources, which is a positive phenomenon from the economic point of view [

66]. The processes of industrial infiltration vary depending on the level of technological advancement, which can also be observed in Wrocław (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). In the low-tech sector, the relocations take place on a larger scale, and in general, their magnitude decreases significantly at a distance of 7–8 km from the city center and, then, increases again. In the high-tech industry, they are most common at a distance of 3–4 km from the city center and, then, become less frequent in the peripheral directions. In both cases, the intensity of relocations in the abovementioned direction increased in the period 2008–2016, but shifts towards peripheral directions are particularly evident in high-tech industries, which is a new phenomenon.

4.2. Contemporary Processes of Location and Relocation of the Industrial Activity in the City of Wrocław and Its Suburbs

The concentration of industrial activity according to the level of technological advancement in individual residential districts of Wrocław is basically low. This is evidenced by the HHI values calculated for each of the analyzed categories of industry operators. There were 361 high-tech, 353 medium-high, 301 medium-low, and 352 low-tech operators. The low concentration of industrial activity from all of the analyzed categories means the industry operators are commonly present across all city districts. It also confirms the diversity of Wrocław’s industry that has persisted for many years in many of its districts [

61]. The versatility of Wrocław’s industry is characteristic of large urban–industrial agglomerations worldwide, where the industry produces a variety of highly processed consumer goods [

49,

55,

63].

Florence’s location quotient points to more notable differences in the industry concentration. Although the value of the quotient for each category of industrial operators according to the level of technological advancement was low, the differences between the individual categories were significant. The highest value of the quotient was reported for high-tech industries (0.19). Much lower values, indicating even greater spatial dispersion, were reported for medium-high-technology industries (0.14). Medium-low- and low-tech industries had a score of 0.05 and 0.08, respectively. This proves that these categories of operators are fully dispersed in the spatial structure of Wrocław.

Analysis of the degree of concentration of industry operators according to the levels of technological advancement in the city districts shows, however, a much higher and more complex structure. A “concentration syndrome” is characteristic for high-tech operators. Florence’s location quotient value was the highest for high-tech operators. This is also confirmed by the highest CR5 concentration ratio (Stare Miasto, Muchobór Mały, Biskupin–Sępolno–Dąbie–Bartoszowice, Gądów–Popowice Płd., and Karłowice–Różanka), i.e., the total share of five consecutive districts in high-tech operators. It jointly accounted for over 30% of all high-tech operators in Wrocław. Accounting for the CR10 index, i.e., the sum of ten consecutive residential districts with the highest share in high-tech businesses, these units incorporated over 50% of tech-tech industrial activity. This is a sign of the growing concentration of high-tech businesses in the central, south, and north-west part of Wrocław. This can also be attributed to institutional factors supporting innovation, including technology parks and technology incubators in this area of Wrocław.

The spatial distribution of industrial activity in the city according to the level of technological advancement indicates that individual city districts offer universal conditions for location of industries with different levels of technological advancement. Central districts of the city, which are the core of the urban center, have specifically attracted small-scale industry operators since the beginning of industrialization. The multi-branch nature of industrial activity in central districts can be attributed to the historical development of the city center, which favored the emergence of more technologically advanced industries. The Old City residential district has the highest share in each level of technological advancement of industrial operators, the highest for high and medium-high-tech businesses (8.15% and 8.26% of the total) and low-tech operators (8.03%). In the Old City residential district, apart from high-tech production, such as the pharmaceutical industry, there were also production plants belonging to industries with a lower technological level of advancement, such as paper or clothing production. It should be noted that the data in the REGON database are presented using the enterprise method, i.e., according to the registered place of business, and not according to the local unit, i.e., the actual place of production. As a result, the concentration of industrial activity in the Old Town district may be attributed to the fact that many companies have decided to have their headquarters (registered office) in the prestigious city center and to conduct their actual activities in other parts of the city (usually peripheral).

Analysis of the location quotient (LQ) of industry operators broken down levels of technological advancement shows the particular importance of the environment in the vicinity of the city’s core, creating favorable conditions for high-tech enterprises. The LQ values in residential districts in this part of the city are more than twice as high as the average for Wrocław (Muchobór Mały or Zacisze–Zalesie–Szczytniki) (

Figure 6). The high-tech industry is characterized by high expenditure levels and requires highly specialized technologies and highly qualified staff. An environment of this kind prevails in the central section of the urban–industrial agglomeration [

11,

34,

39,

53]. The immediate proximity to the Wrocław University of Technology and the aforementioned innovation and entrepreneurship centers, such as technology parks and technology incubators, are important in this context. However, in more peripheral districts, such as Żerniki or Bieńkowice, the LQ value is as much as four times higher than the Wrocław average. In peripheral districts, a small number of industry operators is accompanied by a relatively higher number of high-tech operators; hence, the LQ value is much higher.

City districts located along main road and rail routes in the south-west (incl.: Grabiszyn–Grabiszynek, Muchobór Mały, Muchobór Wielki, Powstańców Śląskich), west (Gądów–Popowice Płd., Pilczyce–Kozanów–Popowice Płn.), north (Karłowice–Różanka, Ołbin), and east (Szczepin, Biskupin–Sępolno–Dąbie–Bartoszowice) of the city, accompanied by the abovementioned institutional forms of supporting innovation, are particularly attractive for the high-tech industries. The synergy of these factors results in a high concentration of high-tech businesses. These urban units form an inner ring surrounding the city core, i.e., the Old Town. High-tech operators are also incidentally present in the peripheral parts of the city (Żerniki, Bieńkowice), which is a new process, as peripheral areas are dominated by large-format trade centers [

67].

However, there are not many businesses of this kind in many peripheral districts in the city’s northern and north-western areas. The LQ value is often very low (below 0.5) in this area, which confirms the patterns of location of industry operators relative to the level of technological advancement.

The medium-high-tech industry shows a similar spatial distribution. In this case, the areas of concentration are more pronounced and create compact zones in southern and northern residential districts of Wrocław (

Figure 7).

The spatial distribution of medium-low-tech businesses is completely different. Medium-low-tech operators are generally common in most residential districts in Wrocław and slightly more concentrated in peripheral districts. This is confirmed by the LQ values for this category of enterprises (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9). As for medium-low technology, the vast majority of residential districts scores an average value for Wrocław, ranging from 0.85 to 1.15. As a distinctive feature, low-tech operators were concentrated in peripheral districts, with significantly higher LQ values in relation to city districts located centrally (

Figure 7).

The infiltration of less technologically advanced industrial activity is clearly directed towards the outskirts of the city. Hence, low-tech industries are specifically concentrated in the suburban zone. This is confirmed by the LQ value of low-tech industry, which is significantly higher not only in the first ring of the suburban zone of the city, but specifically in the second ring. This specifically applies to units located along the main communication routes from Wrocław, creating already coherent zones of industry concentration in the entire city and its suburban zone (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10).

4.3. Internal and External Migrations of Industrial Entities from Wrocław to Its Suburbs

In the analyzed period, 618 industry operators migrated within Wrocław, which constituted 9.1% of such operators in 2008 and 8.2% in 2016. The vast majority were so-called external migrations, i.e., to another district of Wrocław (297 operators) or to the suburban zone of (144). Altogether, 177 industry operators in Wrocław migrated within the same city district. Two hundred and thirty-three industry operators migrated within the suburban zone (16.2% of all such operators in this particular area in 2008 and 11.6% in 2016). Internal migration, which prevailed in the suburban zone, encompassed 176 operators; 15 operators moved to other municipalities, and 42 moved to Wrocław (

Figure 11).

As demonstrated by the figures, relocations of industrial activity in Wrocław were mainly internal, i.e., within the same district or within the city (from one to another district), and did not significantly affect the dynamics of changes in the spatial distribution of industrial activity in Wrocław (up to 10%). In addition, relocations of industrial activity in the suburban zone were limited to the same municipality, which means businesses were not moving to new locations (a different municipality), but were looking for a specific plot of land in their current municipal unit. It is worth noting that in the suburban zone in 2008–2016, 569 additional industry operators were registered, of which 144 (25.3%) moved from Wrocław, and 425 (74.7%) were new businesses. In this context, the relocation of industrial activity and its impact on the growth dynamics of industry operators had a much deeper effect on the spatial distribution of industrial activity in the suburbs (up to 25%) than in the center of the city.

The legal form and size of migrating industrial operators is another important aspect in the analysis of migration of industrial activity from Wrocław to its suburban zone. Among 144 migrating industry operators, there were as many as 115 (79.9%) sole proprietorships. Presumably these were mainly entrepreneurs who moved from the city to its suburbs in the process of sub-urbanization. In this context, the relocation of industry operators from the city to the suburbs is mainly attributed to suburbanization.

4.4. Index of Specializations in Wrocław

The concentration of industrial activity in the city districts is also linked with the scale of industry specialization. The spatial intra-city structure of industrial activity was clearly different from the overall structure of the city (

Figure 12). The districts with the highest local specialization levels were mainly those located peripherally: Jerzmanowo–Jarnołtów–Strachowice–Osiniec, Pawłowice, Wojszyce, Żerniki, and Jagodno. The specialization level was mainly determined by medium-low- and low-tech operators.

The exceptions were Bieńkowice and Plac Grunwaldzki, where specialization was mainly shaped by high-tech operators. This example shows that traditional cores are slowly moving to the outskirts (Bieńkowice). Relatively high specialization in the field of high technology was also characteristic of the Old Town and Muchobór Mały, which confirms the importance of the neighborhood, indicating that, when analyzing the conditions for the location of high-tech companies, it is important to account for both the direct and indirect impact of nearby locations [

67]. Relatively high index values were also recorded in the residential districts along the Odra canal: Kowale, Strachocin–Swojczyce–Wojnów, as determined by several significant operators of the chemical and food industry that must be supplied with water.

As a consequence of the processes of industrial location and relocation in the Wrocław agglomeration in 2008–2016, the changes in the spatial distribution of high and low-tech businesses were basically small (

Figure 13A,B). There was a sharp decline in the share of high-tech operators along with the distance from the agglomeration core (

Figure 13A) and a slight increase in the peripheral areas located at a distance of 20–25 km from the core. The distribution of low-tech operators was definitely more gradual, decreasing with distance from the core (

Figure 13B).

5. Discussion

Each city undergoes specific industrial restructuring, depending on the city’s historical background, economic base, and the quality of the socio-cultural environment [

22,

34,

42].

In the Wrocław agglomeration, both low-tech and high-tech businesses are becoming increasingly deconcentrated towards the suburbs (shifting of the share curves in 2016 compared to 2008). It must, however, be highlighted that new locations of high-tech businesses are highly selective and concentrated only in specific districts of the city peripheries, i.e., these businesses are not uniformly distributed across the city outskirts. The findings also suggest that high-tech businesses attach great importance to their location, which means not all neighborhoods will benefit equally. Knowledge-based communication infrastructure, supply of office space and amenities such as parks and business incubators, or the very specificity of the business operations are of key importance here. These regularities indicate the growing role of the suburban zone, characterized by the intensive penetration of industrial activity from the city center, which also results in an increase in industrial areas [

68]. In the Wrocław agglomeration, the high supply of free warehouse, production, logistics, and service space in specific areas is also important, i.e., in Bielany Wrocławskie (Kobierzyce municipality in the first ring of the agglomeration) at the intersection of two motorways: A4 along the east–west axis (Berlin–Kiev), and A8 along the north–south axis (Wrocław–Poznań–Gdańsk and Wrocław–Łódź–Warsaw). This is where multifunctional centers with parks are built, often in the subzones of special economic zones, offering the possibility of implementing built-to-suit investment projects (buildings designed and constructed strictly according to the needs of specific type of tenants) featuring warehouse, production, logistics, and service spaces, and thus, also creating favorable conditions for high- and medium-high-tech operators. These units also create a favorable neighborhood for the adjacent residential estates adjacent to the city and the neighboring municipalities, which confirms that high-tech operators choose their location based on the characteristics of a target area and also the neighboring areas.

The economic processes taking place in a city and in its suburban zone, as evidenced in this study, are multidirectional and selective in nature. The spatial concentration of industrial activity, which is often accompanied by large-format commercial facilities in the suburbs of Wrocław, indicates the level of advancement of suburbanization processes in its area. The suburban zone is not limited to residential estates or small service businesses in suburban rural areas. At the same time, the spatial concentration of industry in the suburban zone of Wrocław is relatively diversified (or specific), as determined by industrial activity and not only by commerce [

69] or business support services, as is typically the case in many cities in Western Europe or North America. This type of suburban zone is a hallmark of Paris [

63] or Montreal [

64]. Unfortunately, large-scale comparisons of intra-city layouts in Europe are still scarce ([

70] for Lyon; [

31] for Oslo; [

3] for Barcelona). There are several analysis for Turkey ([

71] for Istanbul), Canada ([

72] for Hamilton), Japan ([

8] for Tokyo), and the USA [

73]. There are more analyses concerning Chinese cities (Nanjing, Shanghai, Wuhan). It is not surprising, as the development of cities and the establishment of businesses have been of great importance in China in recent years [

74,

75]. However, these cities are completely different, and their size is incomparable to many European cities.

The processes of industrial location in Wrocław and its suburbs show that the level of technological advancement of new operators and their concentration increases in the core of the metropolitan area. The agglomeration center is, therefore, a specific place where high-tech businesses prevail as they require a specific economic environment offered by city centers rather than city outskirts. In the post-socialist states, foreign capital played a particular role in industrial restructuring due to the scarcity of domestic capital [

22,

65]. Its share in industrial locations in the suburban zones of large cities in post-socialist states was far from uniform. In Wrocław, the concentration of foreign capital operators is the highest in the second ring of municipalities and is much lower in the central city and the first ring, unlike Budapest, where foreign companies invested primarily in the already established operators located in the industrial areas within the city or in its immediate vicinity [

22]. The spatial distribution of industrial activity in Wrocław and its suburbs bears a significant similarity to the processes of infiltration of industry from the city center, as was the case in the cities of Spain [

76] or the Czech Republic [

65]. Businesses need an innovative environment mostly offered by the city centers, while low-tech operators have labor-intensive technologies and need to be established in more densely populated areas where more labor force is available. For this reason, medium-low- and low-tech businesses are highly concentrated in the second ring of the Wrocław agglomeration. The spread of external effects and the continuous diffusion of information technologies may, therefore, also bring new opportunities to entrepreneurs in areas more distant from the central city (as illustrated by the first ring in Wrocław). These sites typically have lower financial and non-equity costs (less pollution, lower crime rates, lower value of real estates, less cumbersome process to obtain building permits) compared to large cities [

77].

6. Conclusions

The research results confirm the adopted research hypothesis that revealed significant changes taking place in the spatial structure of the industrial concentration and specialization in Wrocław and its immediate vicinity. The city is characterized by a significant variety and complexity of the analyzed processes. The spatial distribution of industrial activity in the city according to the level of technological advancement indicates that individual city districts offer universal conditions for the location of industries with different levels of technological advancement. High-tech businesses, however, are clearly concentrated in the residential districts of the central area of Wrocław located along the most important communication routes (road and railways) where institutions supporting innovation (technology parks, business incubators) are established, in the south-west and north-east direction. The intensity of spatial distribution of industrial activity in Wrocław shifts towards the periphery of the city. This results in the displacement of less advanced low-tech industry operators, but also the emergence of high-tech industry operators in more peripheral city districts, albeit less numerous than in the city center. This is confirmed by the Krugman Specialization Index. The nature of the spatial concentration and specialization of industrial activity in Wrocław can herald a new spatial pattern, i.e., the shift of high-tech operators towards peripheries, also determined by a synergy between lower rental costs and centers of institutional support for entrepreneurship. This is likely attributed to the spontaneous processes of suburbanization and the accompanying relocation of industrial activity typical of large urban centers in post-socialist states. This is confirmed by studies on the growing importance of localization for high-tech industries, as well as in the first suburban ring of a large urban center [

11,

65]. These processes taking place in the cities of post-socialist states proceed in a diversified manner; they bear similarities to the patterns identified in cities in the West and have their specific ambiguous characteristics resulting from both the relatively short history and rapid course of suburbanization processes. The presented example of changes in the industrial activity of Wrocław and its suburbs confirmed the correctness of these statements. This type of research should be continued in the future to be able to determine whether the observed differences in the dynamics and nature of spatial changes in industrial activities in Western Europe and Central and Eastern Europe were significant.

A certain limitation in the conducted research was the fact that, firstly, focusing on the inner city level allowed for obtaining more accurate results, but the existence of a small number of studies of the analyzed phenomenon at this spatial level largely prevented a more precise comparison with similar studies; secondly, the limited scope of static data at the local level to the number of industrial entities without taking into account, inter alia, the value of industrial production may to some extent limit the inference; third, statistical data were aggregated to the city’s housing estates and community, which contributed to the loss of information on individual industrial entities. However, all the implemented solutions were necessary for the clarity and fluidity of the narrative.

Based on the results of spatial regularities in the location of industry according to the intensity of R&D works in the area of the entire agglomeration, some interesting policy implications arise. First, the intra-urban level is appropriate for analyzing enterprises’ location decisions. This is an important point, as it means that the characteristics of a neighborhood matter to businesses in the localization process. Secondly, public administrations should take into account the spatial regularities of the location of high-tech enterprises when developing a policy of attracting new technology companies to the city’s housing estates. It will also facilitate proper planning of the functions of individual parts of the city. The contemporary processes of concentration and specialization of the industrial activity in Wrocław have created a zonal system, which persists to this day. Specific factors in the location of business activity (e.g., main communication routes, economic functions of individual residential districts) play an important role in this process. This results in the increasing functional specialization of individual spatial units of Wrocław, extending into the suburban zone.