Place-Based Policy in the “Just Transition” Process: The Case of Polish Coal Regions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Objective of Study

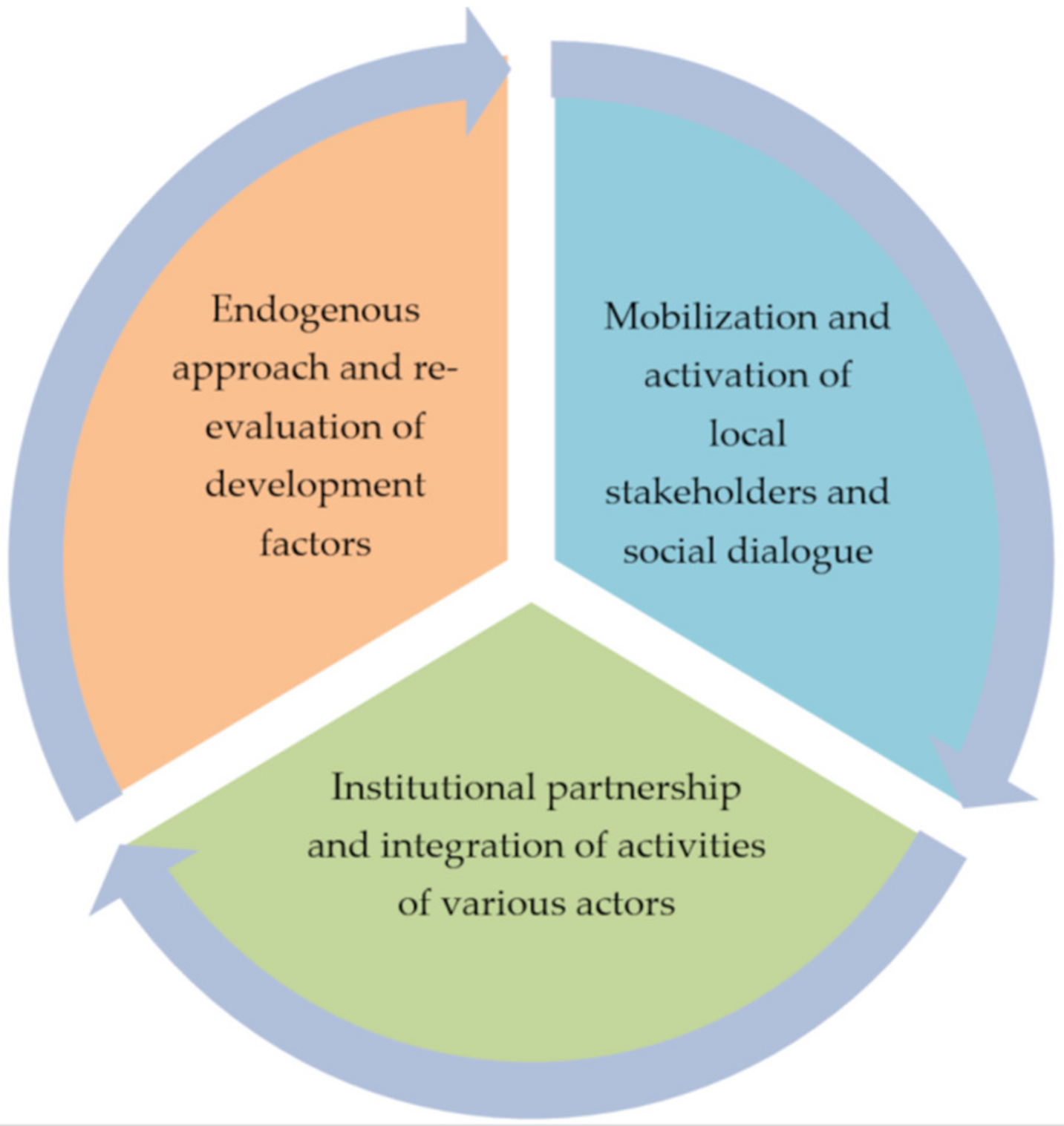

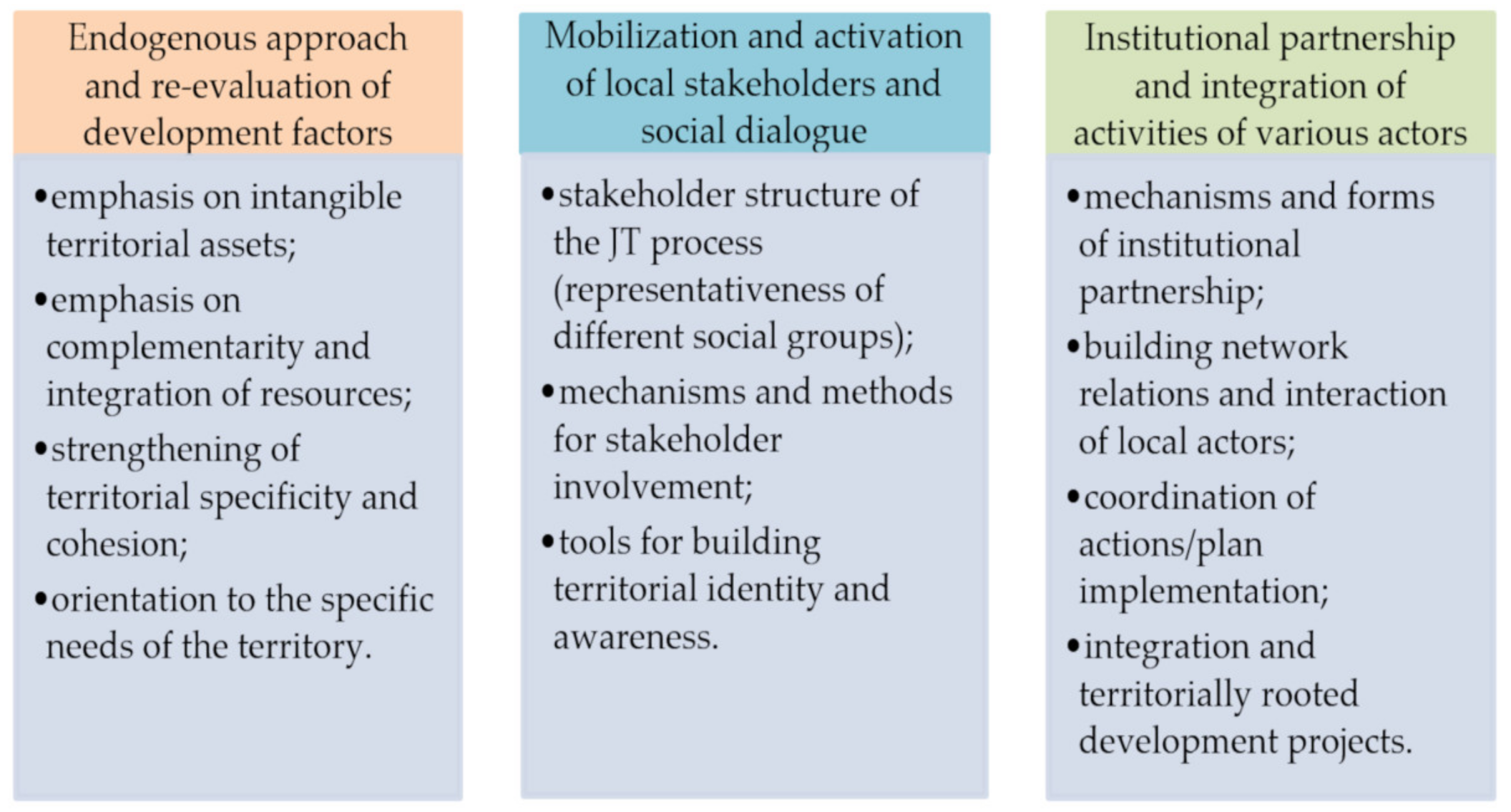

1.2. Place-Based Policy—Theoretical Framework

1.3. The EU Just Transition Mechanism Framework

- Coal mining activities are being carried out;

- There is a significant number of people working in the mining sector and a significant share of those working in mining in total employment;

- There are significant environmental problems, in particular post-mining land transformation and air pollution [32].

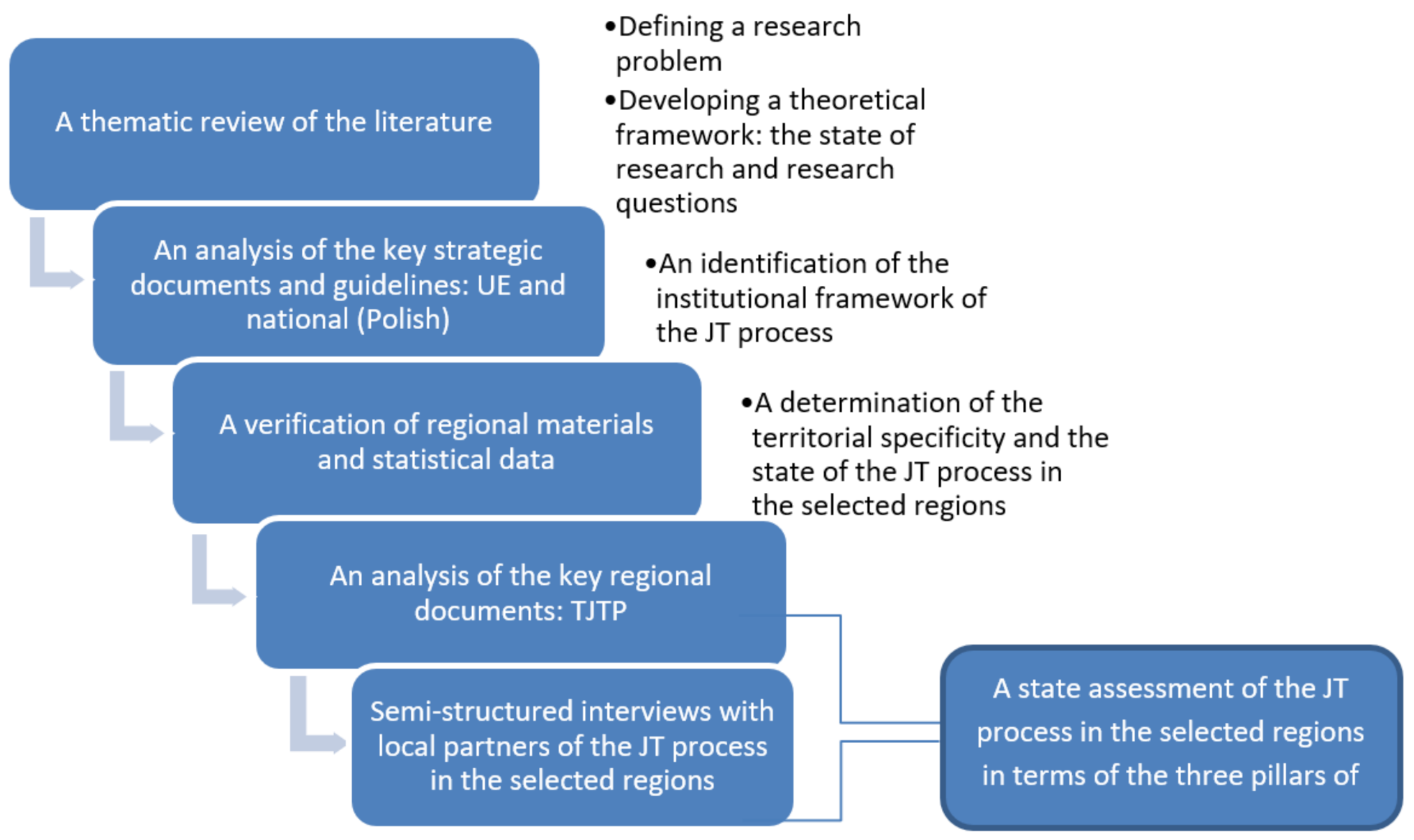

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Method and Sources of Information

- Direct involvement in the planning of the JT process—respondents are persons who have a significant influence on the definition of the objectives, scope of activities and implementation mechanisms of the TJTP;

- Diversity of stakeholders in the JT process—representatives of different social groups, i.e., local and regional authorities, NGOs, workers’ unions and scientific and research institutions participated in the study;

- Different perspectives of the JT process in the regions—semi-structured interviews were conducted with both the entities located in the studied regions (the so-called internal respondents) and the entities seeing the transformation process from a wider, national and European perspective (the so-called external respondents).

2.2. Criteria for Transition Territories’ Selection and Case Study Description

2.2.1. Upper Silesia

2.2.2. Bełchatów Basin

3. Results

3.1. Just Transition Process in Upper Silesia

3.1.1. Endogenous Approach and Re-Evaluation of Development Factors

3.1.2. Mobilization and Activation of Local Stakeholders and Social Dialogue

3.1.3. Institutional Partnership and Integration of Local Actors

3.2. Just Transition Process in the Bełchatów Basin

3.2.1. Endogenous Approach and Re-Evaluation of Development Factors

3.2.2. Mobilization and Activation of Local Stakeholders and Social Dialogue

3.2.3. Institutional Partnership and Integration of Local Actors

- A team for the transformation of mining areas in the Łódzkie Province, comprising nearly 40 people (representatives of mainly local governments and one NGO);

- The Just Transition Team operating within the Provincial Social Dialogue Council (dominated by trade union representatives, as well as representatives of the Province’s Marshal and the Province’s Governor).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Areas of Analysis

| Areas of TJTP Analysis/Dispositions for Semi-Structured Interviews | Research Method TJTP—Territorial Just Transition Plan SSI—Semi-Structured Interview |

| I. Endogenous approach to development and re-evaluation of factors and determinants of development | |

| TJTP |

| TJTP |

| TJTP/SSI |

| II. Mobilization and activation of local actors and social dialogue | |

| TJTP/SSI |

| SSI |

| SSI |

| TJTP/SSI |

| TJTP/SSI |

| III. Institutional partnerships and integration of activities of various actors | |

| TJTP/SSI |

| TJTP/SSI |

| TJTP/SSI |

| TJTP/SSI |

Appendix B. Structure and Characteristics of Respondents

| Institution/Region | Respondent’s Characteristics |

| Marshal’s Office of the Silesian Province (two respondents) | A representative of regional self-government administration; a person supervising and responsible for the JT process in the Silesian Province |

| Jastrzębie Zdrój City Hall | Representatives of local authorities; persons directly involved in the JT process in the Silesian Province |

| Bytom City Hall | |

| Social Economy Foundation | A representative of a social organization; a person directly involved in the JT process in the Silesian Province |

| Science and Technology Park | A representative of the business sector involved in the JT process in the Silesian Province |

| Marshal’s Office of the Łódzkie Province (two respondents) | A representative of regional self-government administration; a person supervising and responsible for the JT process in the Łódzkie Province |

| Bełchatów District Office | A representative of district authorities; a person directly involved in the JT process in the Łódzkie Province |

| Bełchatów City Hall | Representatives of local authorities; persons directly involved in the JT process in the Łódzkie Province |

| Kamieńsk City Hall and Municipality Office | |

| Kleszczów Municipality Office | |

| Center for Ecological Activities “Źródła” | A representative of a social organization; a person directly involved in the JT process in the Łódzkie Province |

| Industrial and Technological Park | Representatives of the business sector involved in the JT process in the Łódzkie Province |

| Business Center Club (BCC) | |

| Institute for Ecology of Industrial Areas | Scientific representatives directly involved in the JT process in the Silesian and Łódzkie Provinces |

| University of Silesia |

References

- Alves Dias, P.; Kanellopoulos, K.; Medarac, H.; Kapetaki, Z.; Miranda Barbosa, E.; Shortall, R.; Czako, V.; Telsnig, T.; Vazquez Hernandez, C.; Lacal Arantegui, R.; et al. EU Coal Regions: Opportunities and Challenges Ahead; JRC Science for Policy Report; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kapetaki, Z.; Ruiz Castello, P.; Armani, R.; Bodis, K.; Fahl, F.; Gonzalez Aparicio, I.; Jaeger-Waldau, A.; Lebedeva, N.; Pinedo Pascua, I.; Scarlat, N.; et al. Clean Energy Technologies Coal Regions in: Opportunities for Jobs and Growth; JRC Science for Policy Report; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Milani, B. Designing the Green Economy. In The Postindustrial Alternative Corporate Globalization; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.: Lanham, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- The European Comission. The European Green Deal; COM/2019/640 Final. The European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640&from=EN (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Rainnie, A.; Beer, A.; Rafferty, M. Effectiveness of Place Based Packages; Regional Australia Institute: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaney, J. Place-Based Approaches to Regional Development: Global Trends and Australian Implications; Australian Business Foundation: Sydney, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, R.F.B.; Rodrigues, M.D.A.; Vieira, S.A.; Batistella, M.; Farinaci, J. Perspectives for environmental conservation and ecosystem services on coupled rural-urban systems. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 2017, 15, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thissen, M.; van Oort, F. European place-based development policy and sustainable economic agglomeration. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2010, 101, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantz, T.L.; Ioppolo, G.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Arbolino, R. Understanding the correlation between energy transition and urbanization. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2021, 40, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, F. An Agenda for a Reformed Cohesion Policy. A Place-Based Approach to Meeting European Union Challenges and Expectations; Independent Report prepared at the request of Danuta Hübner, Commissioner for Regional Policy. European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. Available online: www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/..._/barca_report_en.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- OECD. How Regions Grow. Trend and Analysis; OECD: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Regions Matter. Economic Recovery, Innovation and Sustainable Growth; OECD: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, F.; McCann, P.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. The case for regional development intervention: Place-based versus place-neutral approaches. J. Reg. Sci. 2012, 52, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Institutionalist analysis, communicative planning and shaping places. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1999, 19, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S. Understanding territorial cohesion. Plan. Pract. Res. 2005, 20, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faludi, A. Territorial Cohesion Under the Looking Glass: Synthesis Paper about the History of the Concept and Policy Background to Territorial Cohesion. 2009. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Andreas-Faludi/publication/27353983_Territorial_cohesion_under_the_looking_glass_synthesis_paper_about_the_history_of_the_concept_and_policy_background_to_territorial_cohesion/links/5a9294d20f7e9ba4296e48af/Territorial-cohesion-under-the-looking-glass-synthesis-paper-about-the-history-of-the-concept-and-policy-background-to-territorial-cohesion.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Nosek, S. Territorial cohesion storylines in 2014–2020 cohesion policy. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 2157–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, A.; McKenzie, F.; Blažek, J.; Sotarauta, M.; Ayres, S. Every Place Matters. Towards Effective Place-Based; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Regional Development Warsaw. Territorial Dimension of EU Policy. Strategic Programming, Coordination and Institutions Territorially-Sensitive for an Efficient Delivery of the New Growth Agenda; Ministry of Regional Development: Warsaw, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowska, A. Terytorializacja rozwoju i polityki regionalnej. In Terytorialny Wymiar Polityki Regionalnej. Polskie Doświadczenia; Nowakowska, A., Szlachta, J., Eds.; Biuletyn KPZK: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; pp. 26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Regional Development. Place-Based Territorially Sensitive and Integrated Approach; Ministry of Regional Development: Warsaw, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Camagni, R. Territorial capital and regional development. In Handbook of Regional Growth and Development Theories; Capello, R., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2009; pp. 118–132. [Google Scholar]

- Garcilazo, J.E.; Martins, J.O.; Tompson, W. Why Policies May Need to Be Place-Based in Order to Be People-Centred. VOX EU. 20 November 2010. Available online: https://voxeu.org/article/why-policies-may-need-be-place-based-order-be-people-centred (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Moodie, J.R.; Meijer, M.W.; Salenius, V.; Kull, M. Territorial governance and Smart Specialisation: Empowering the sub-national level in EU regional policy. Territ. Politi. Gov. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, G.; Pugalis, L. Shifting paradigms: People-centred models, active regional development, space-blind policies and place-based approaches. Local Econ. 2014, 29, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlachta, J.; Zaucha, J. Wzmacnianie terytorialnego wymiaru polityki spójności w polsce w latach 2014–2020. In Miasta—Metropolie—Regiony: Nowe Orientacje Rozwojowe; Klasik, A., Kuźnik, F., Eds.; Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Churski, P. Podejście zorientowane terytorialnie (place-based policy)—Teoria i praktyka polityki regionalne. Rozw. Reg. Polityka Reg. 2018, 41, 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zaucha, J.; Brodzicki, T.; Ciołek, D.; Komornicki, T.; Mogiła, Z.; Szlachta, J.; Zaleski, J. Terytorialny Wymiar Wzrostu i Rozwoju; Dyfin: Warsaw, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowska, A. (Ed.) Zintegrowane plany rozwoju—W stronę terytorialno-funkcjonalnego podejścia do rozwoju jednostki terytorialnej. In Nowoczesne Metody i Narzędzia Zarządzania Rozwojem Lokalnym i Regionalnym; Uniwersytet Łódzki: Łódź, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Anczewska, M.; de Grandpré, J.; Mantzaris, N.; Stefanov, G.; Treadwell, K. Just Transition to Climate Neutrality. Doing Right by the Regions; WWF: Berlin, Germany, 2020. Available online: https://wwfint.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/wwf_just_transition_to_climate_neutrality_1.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Carodi, P. Recessions, recoveries and regional resilience: Evidence on Italy. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2014, 8, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mustata, A. Eight Steps for a Just Transition; CEE Bankwatch: Bucharest, Romania, 2017. Available online: https://bankwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/eight-steps-just-transition.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Boschma, R.A.; Martin, R. Editorial: Constructing an evolutionary economic geography. J. Econ. Geogr. 2007, 7, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament; European Union. Regulation (EU) 2021/1056 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 June 2021 Establishing the Just Transition Fund. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32021R1056&from=EN (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- European Commission. The Just Transition Mechanism: Making Sure No One Is Left Behind. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/actions-being-taken-eu/just-transition-mechanism_en (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Bankwatch Network. Territorial Just Transition Plan Checklist, How to Make TJTPs Climate and People Driven; Bankwatch Network: Prague, Czech Republic, 2020. Available online: https://bankwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/TJTP-checklist-1.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Duckett, D.; Feliciano, D.; Martin-Ortega, J.; Munoz-Rojas, J. Tackling wicked environmental problems: The discourse and its influence on praxis in Scotland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 154, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No 240/2014 of 7 January 2014 on the European Code of Conduct on Partnership in the Framework of the European Structural and Investment Funds. 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014R0240&from=EN (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Slaskiego. Terytorialny Plan Sprawiedliwej Transformacji. Województwo Śląskie, Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Śląskiego. 2021. Available online: https://transformacja.slaskie.pl/content/terytorialny-plan-sprawiedliwej-transformacji1 (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Ministerstwo Klimatu i Środowiska. Polityka Energetyczna Polski do 2040 r; Ministerstwo Klimatu i Środowiska: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/klimat/polityka-energetyczna-polski (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Strategia Rozwoju Województwa Łódzkiego 2030. 2021. Available online: http://strategia.lodzkie.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/SRWL-2030_6.05.2021_uchwalona.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Terytorialny Plan Sprawiedliwej Transformacji Województwa Łódzkiego (Projekt). 2021. Available online: http://strategia.lodzkie.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/projekt-Terytorialnego-Planu-Sprawiedliwej-Transformacji-WL_2021.06.29.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Strategia Rozwoju Województwa Śląskiego “Śląskie 2030”, Zielone Śląskie, Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Śląskiego, Katowice. 2020. Available online: https://www.slaskie.pl/content/strategia-rozwoju-wojewodztwa-slaskiego-slaskie-2030 (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Śląskiego. Potencjały i Wyzwania Rozwojowe Województwa Śląskiego w Kontekście Sprawiedliwej Transformacji, Załącznik Diagnostyczny do TPST; Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Śląskiego: Katowice, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Innobservator Silesia. Regionalna Strategia Innowacji Województwa Śląskiego 2030 (PROJEKT). 2021. Available online: https://ris.slaskie.pl/czytaj/konsultacje_spoleczne_projektu_regionalnej_strategii_innowacji_wojewodztwa_slaskiego_2030 (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Innobservator Silesia. Program Rozwoju Technologii Województwa Śląskiego na Lata 2019–2030, Katowice. 2019. Available online: https://ris.slaskie.pl/dokument/program_rozwoju_technologii_wojewodztwa_slaskiego_na_lata_2019__2030 (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Umowa Społeczna Dotycząca Transformacji Sektora Górnictwa Węgla Kamiennego Oraz Wybranych Procesów Transformacji Województwa Śląskiego. 2021. Available online: https://solidarnosckatowice.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Umowa-Spoleczna.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Burchard-Dziubińska, M.; Kassenberg, A.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Pacura, J.; Rzeńca, A.; Sobol, A.; Szablewski, A. Zielona Transformacja Albo Zapaść. Zagłębie Bełchatowskie w Przededniu Zmian; Źródła: Łódź, Poland, 2021. Available online: https://api.ngo.pl/media/get/158170 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Belchatow. Ośrodek Działań Ekologicznych “Źródła”. 2020. Available online: https://belchatow2050.pl/ (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Dańkowska, A.; Sadura, P. Przespana Rewolucja; Krytyka Polityczna: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. Available online: https://wydawnictwo.krytykapolityczna.pl/przespana-rewolucja-934 (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Harrahill, K.; Douglas, O. Framework development for ‘just transition’ in coal producing jurisdictions. Energy Policy 2019, 134, 110990. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/41622949/Framework_development_for_just_transition_in_coal_producing_jurisdictions (accessed on 20 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Bartecka, M. Platforma Węglowa Jako Mechanizm Wspierania Sprawiedliwej Transformacji. Podstawowe Informacje; Związek Stowarzyszeń Polska Zielona Sieć: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. Available online: http://zielonasiec.pl/wp-content/uploads/Platforma-w%C4%99glowa.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Kiewra, D.; Szpor, A.; Witajewski-Baltvilks, J. Sprawiedliwa Transformacja Węglowa w Regionie Śląskim Implikacje dla Rynku Pracy; Instytut Badań Strukturalnych: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. Available online: https://ibs.org.pl/publications/sprawiedliwa-transformacja-weglowa-w-regionie-slaskim-implikacje-dla-rynku-pracy/ (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- Frankowski, J.; Mazurkiewicz, J. Województwo Śląskie w Punkcie Zwrotnym Transformacji; Instytut Badań Strukturalnych: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. Available online: https://ibs.org.pl/publications/wojewodztwo-slaskie-w-punkcie-zwrotnym-transformacji/ (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- Johanson, J.E.; Vakkuri, J. Governing Hybrid Organisations. Exploring Diversity of Institutional Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sabato, S.; Fronteduu, B. A Socially Just Transition through the European Green Deal; ETUI Research Paper, Working Paper; The European Trade Union Institute: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, P.; Newell, P. Sustainability transitions and the state. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, in press. Available online: https://www.cssn.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Johnstone_Newell_2017_sustainabilitytransitionsandthestate_EIST.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2021). [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, M. Fossil fuel subsidy reform, rent management and political fragmentation in developing countries. New Political Econ. 2015, 20, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodie, J.; Tapia, C.; Löfving, L.; Gassen, N.; Cedergren, E. Towards a territorially just climate transition—Assessing the swedish EU territorial just transition plan development process. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nowakowska, A.; Rzeńca, A.; Sobol, A. Place-Based Policy in the “Just Transition” Process: The Case of Polish Coal Regions. Land 2021, 10, 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101072

Nowakowska A, Rzeńca A, Sobol A. Place-Based Policy in the “Just Transition” Process: The Case of Polish Coal Regions. Land. 2021; 10(10):1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101072

Chicago/Turabian StyleNowakowska, Aleksandra, Agnieszka Rzeńca, and Agnieszka Sobol. 2021. "Place-Based Policy in the “Just Transition” Process: The Case of Polish Coal Regions" Land 10, no. 10: 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101072

APA StyleNowakowska, A., Rzeńca, A., & Sobol, A. (2021). Place-Based Policy in the “Just Transition” Process: The Case of Polish Coal Regions. Land, 10(10), 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10101072