Evolution Pattern of Hydraulic Characteristics at a Bridge Site: The Influence of Key Flood Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Models and Method

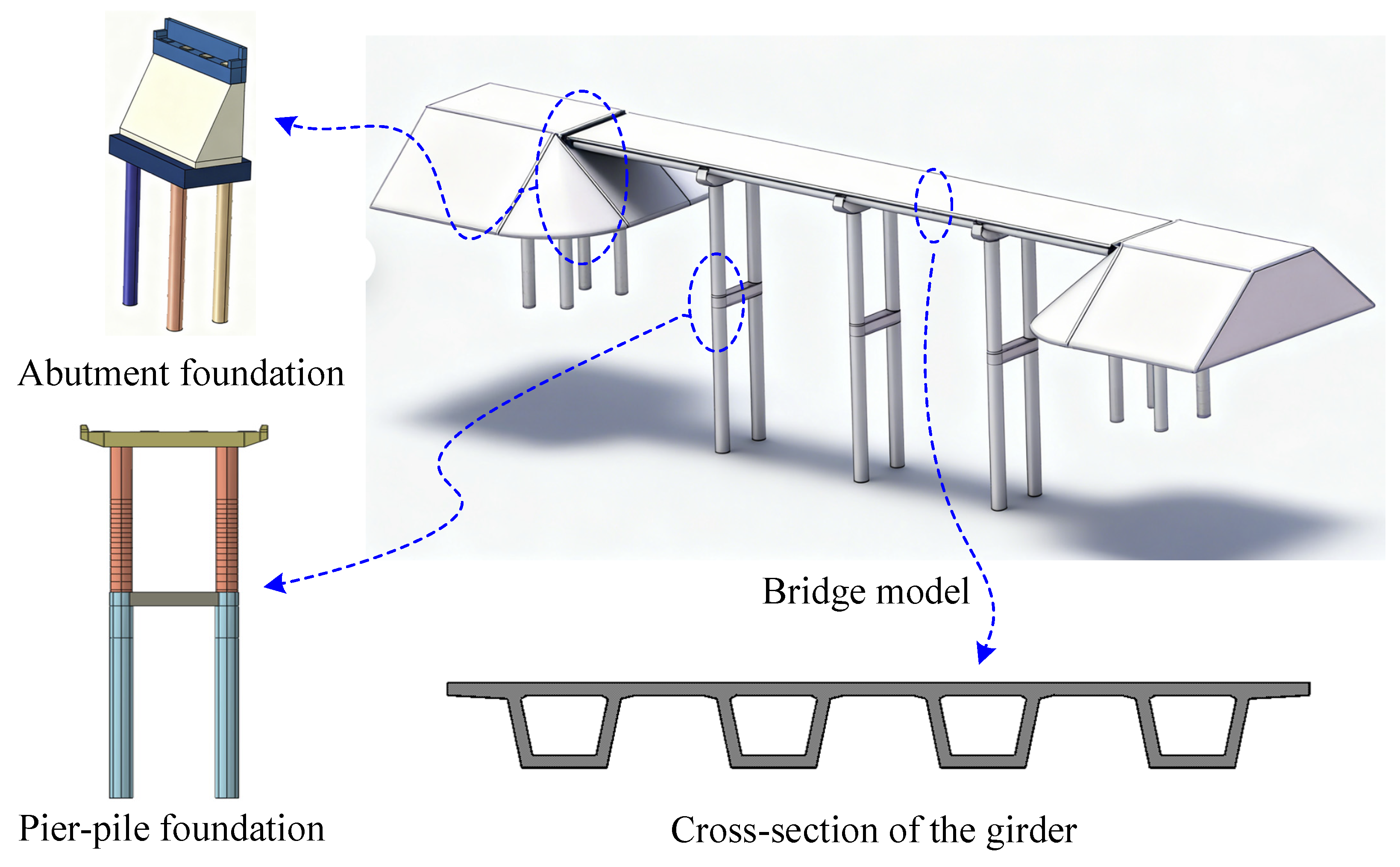

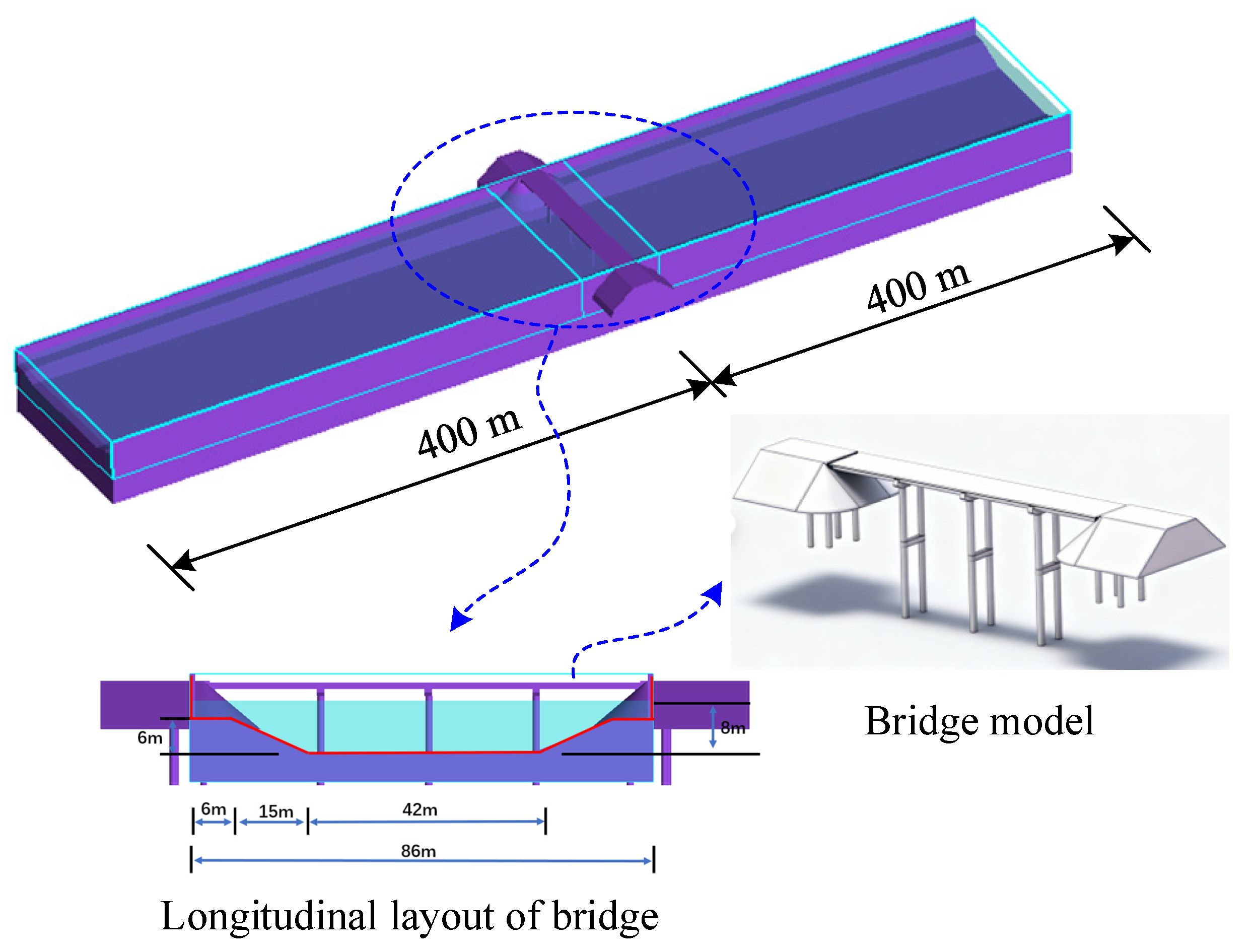

2.1. Structural Model

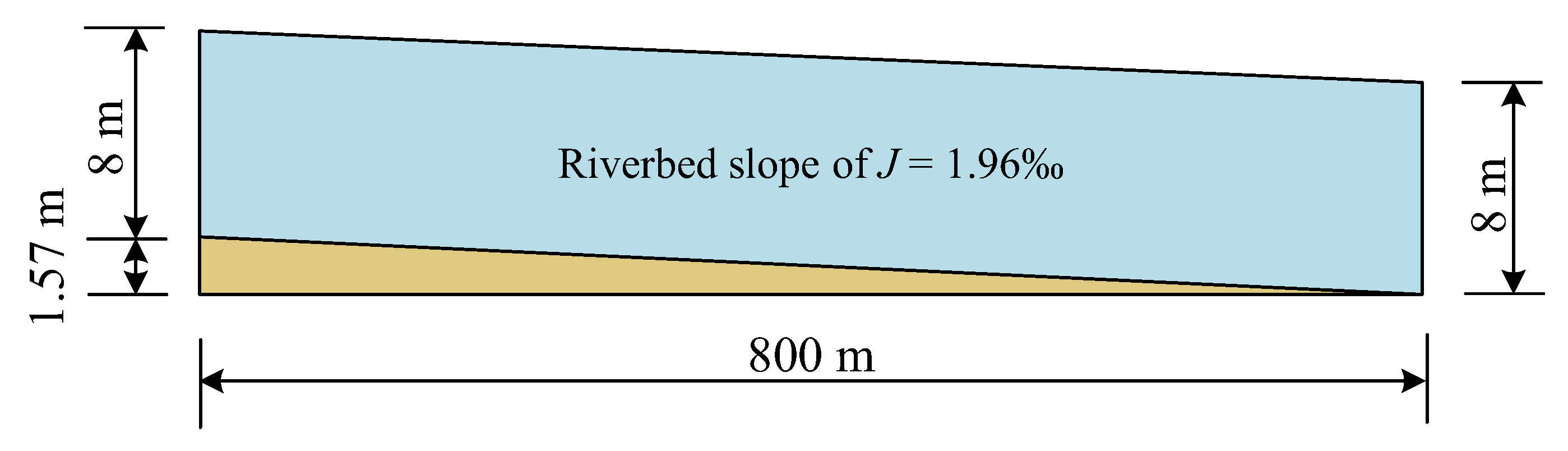

2.2. Hydraulic Model

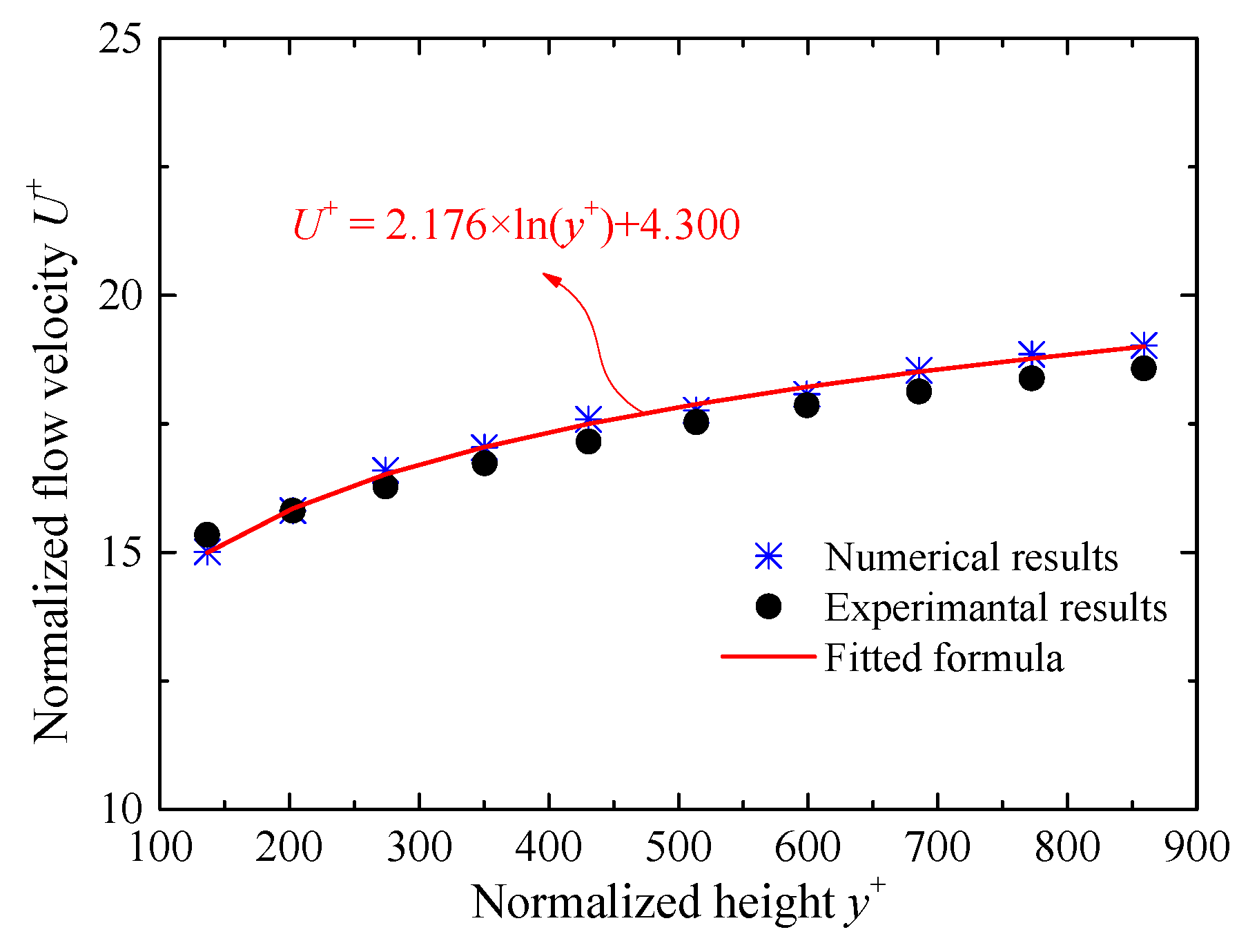

2.3. Model Validation

3. Results and Discussion

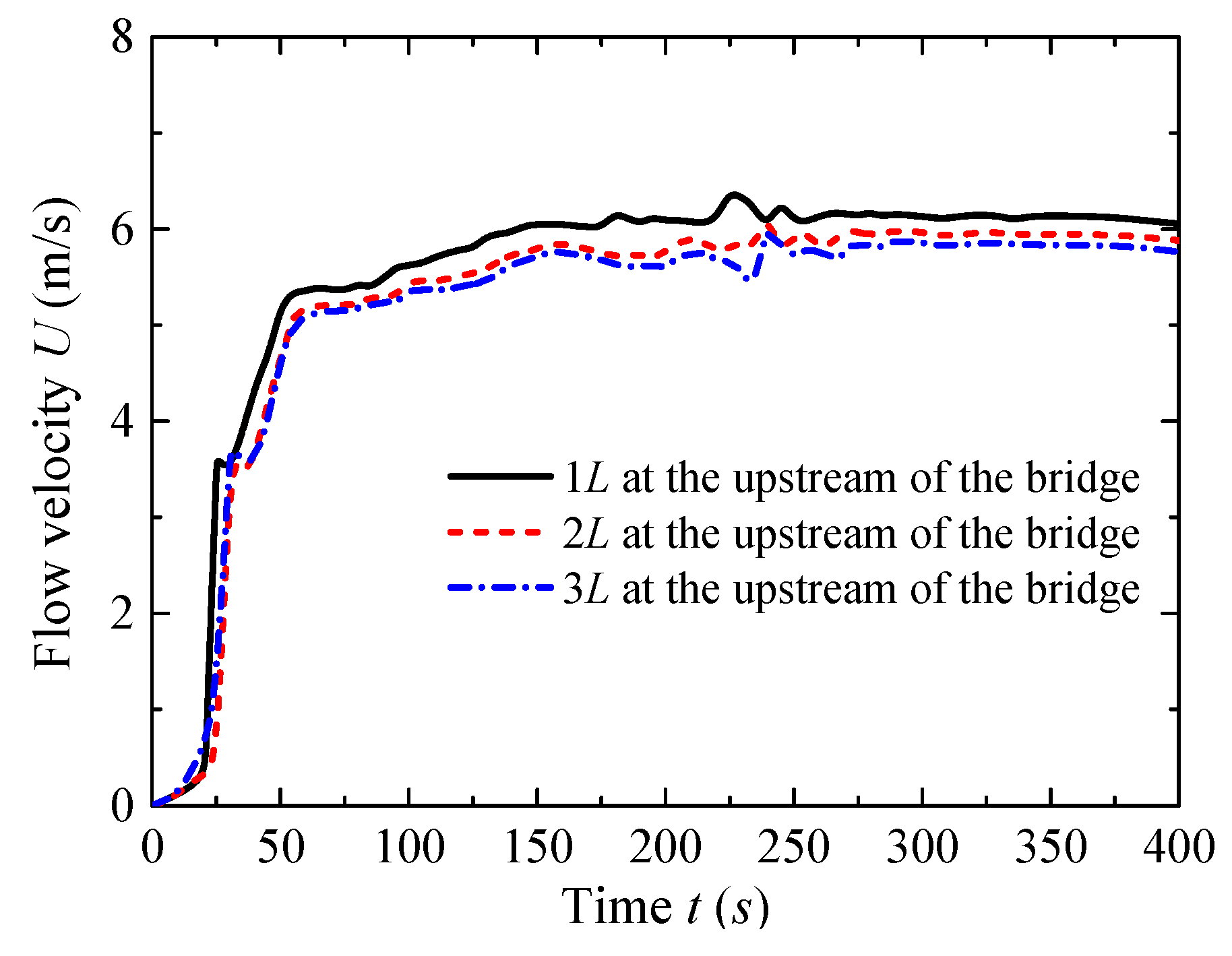

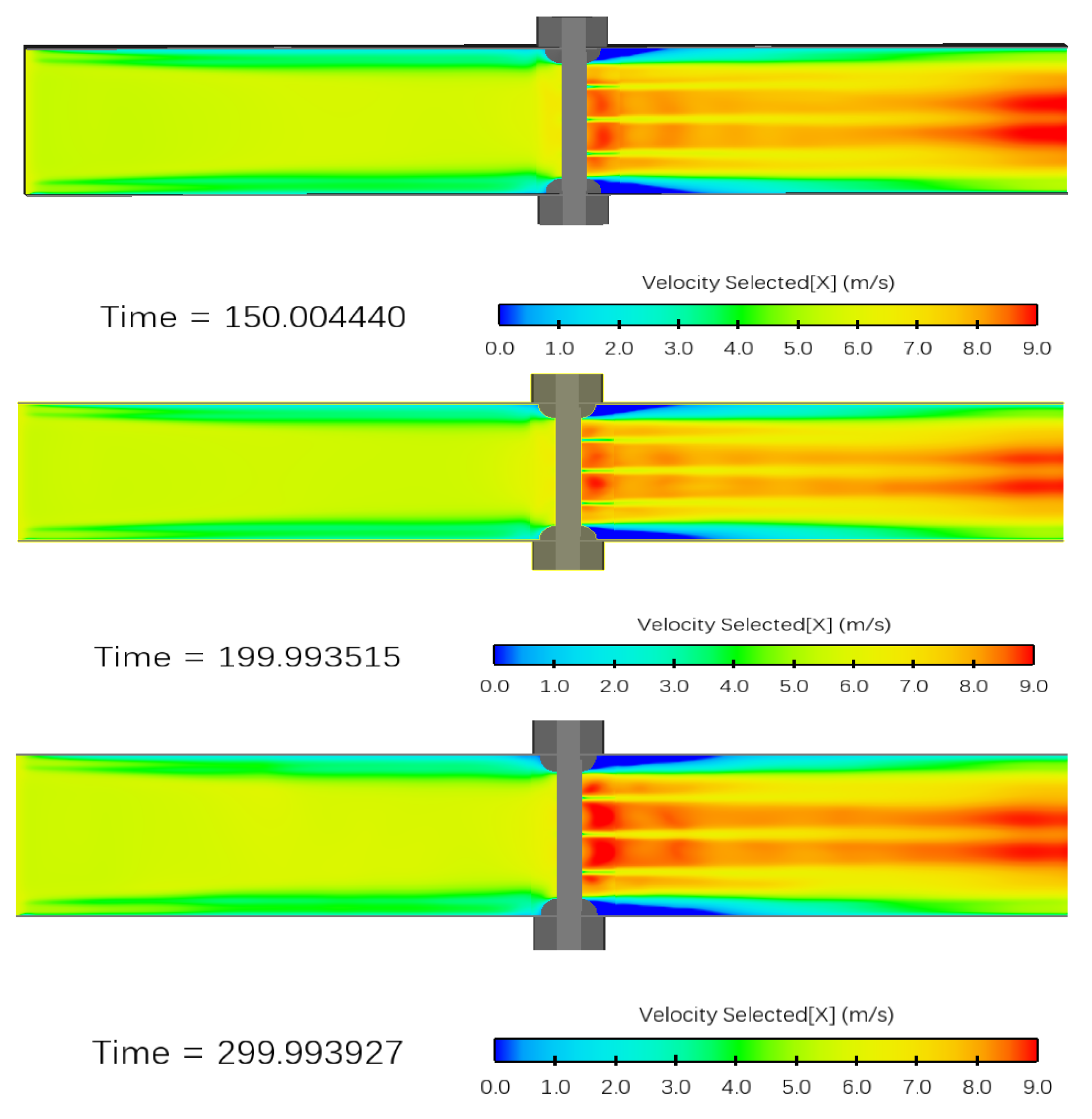

3.1. Determination of Optimal Flow Duration

3.2. Effects of Initial Flow Velocity

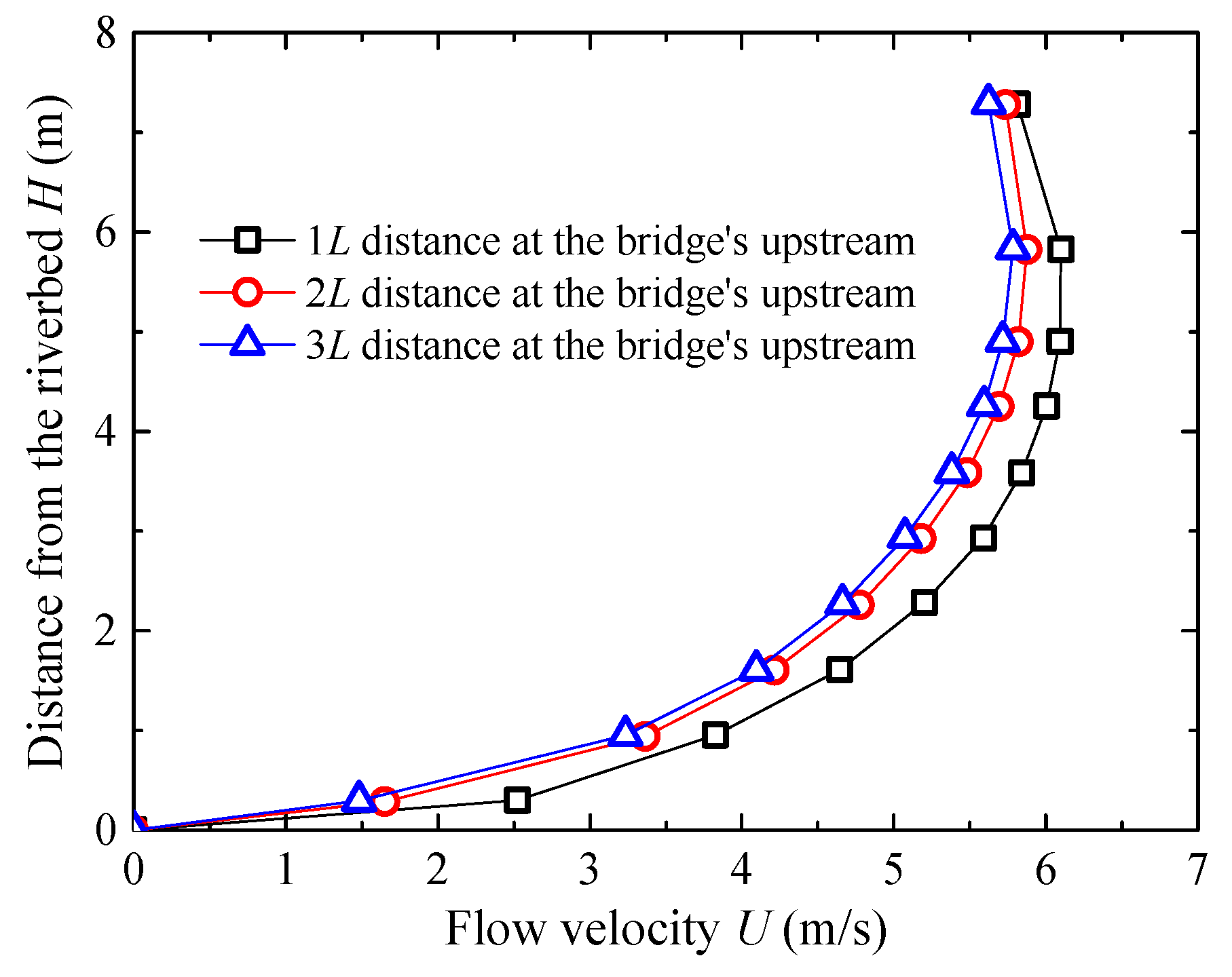

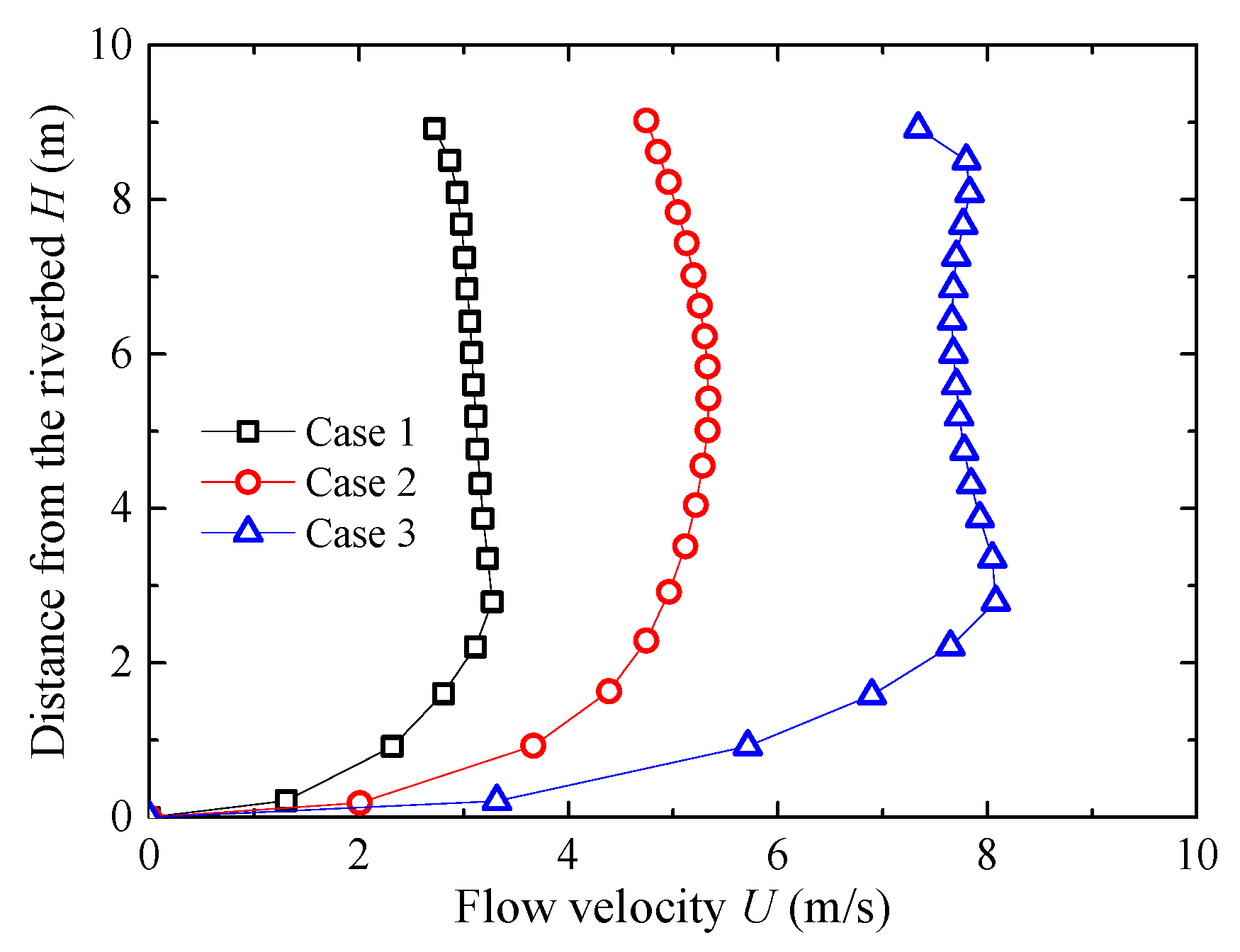

3.2.1. Upstream Flow Velocity Distribution

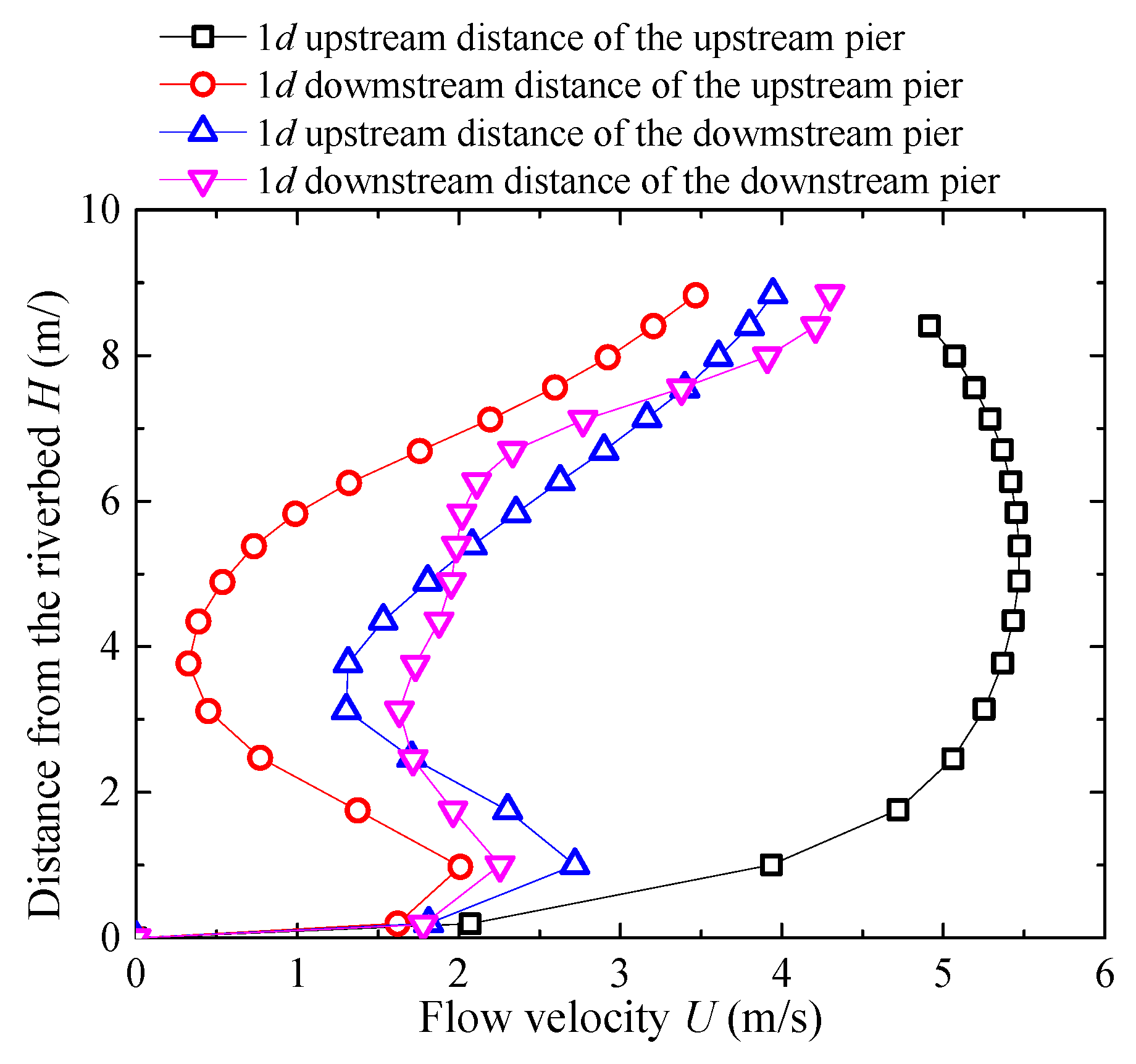

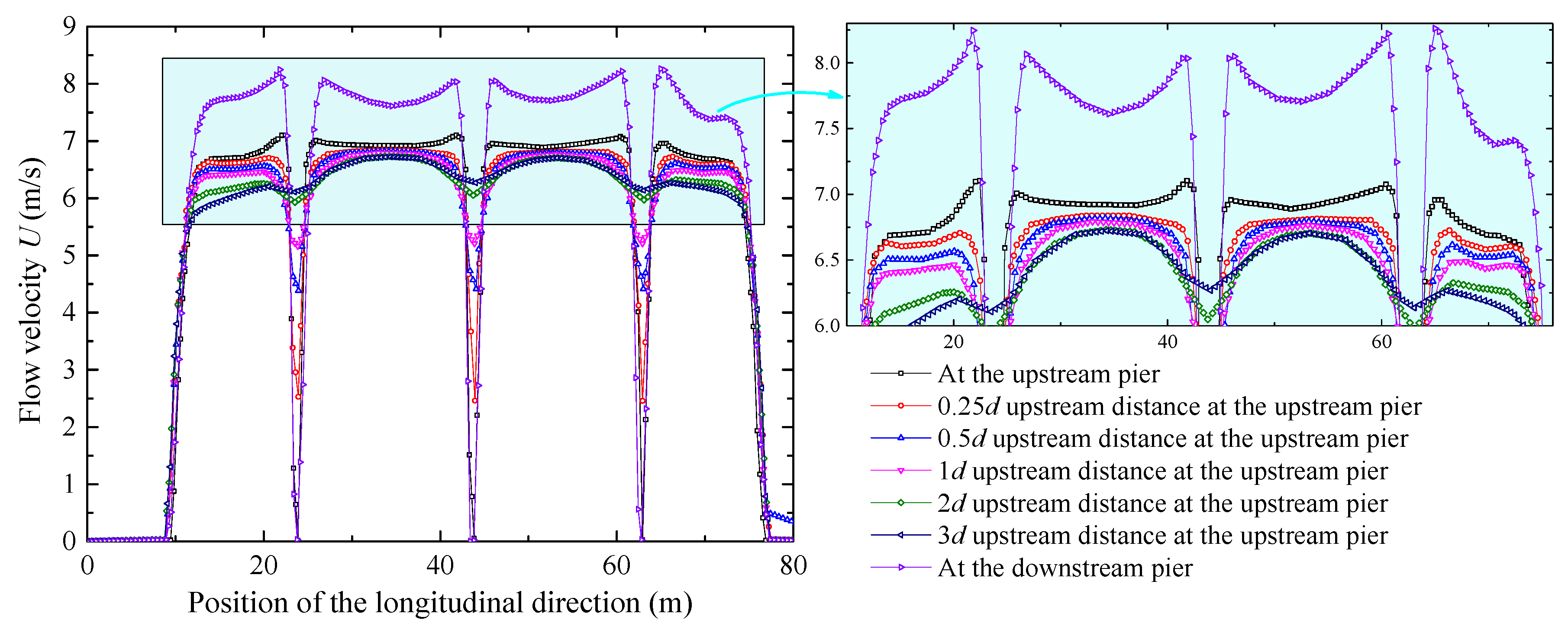

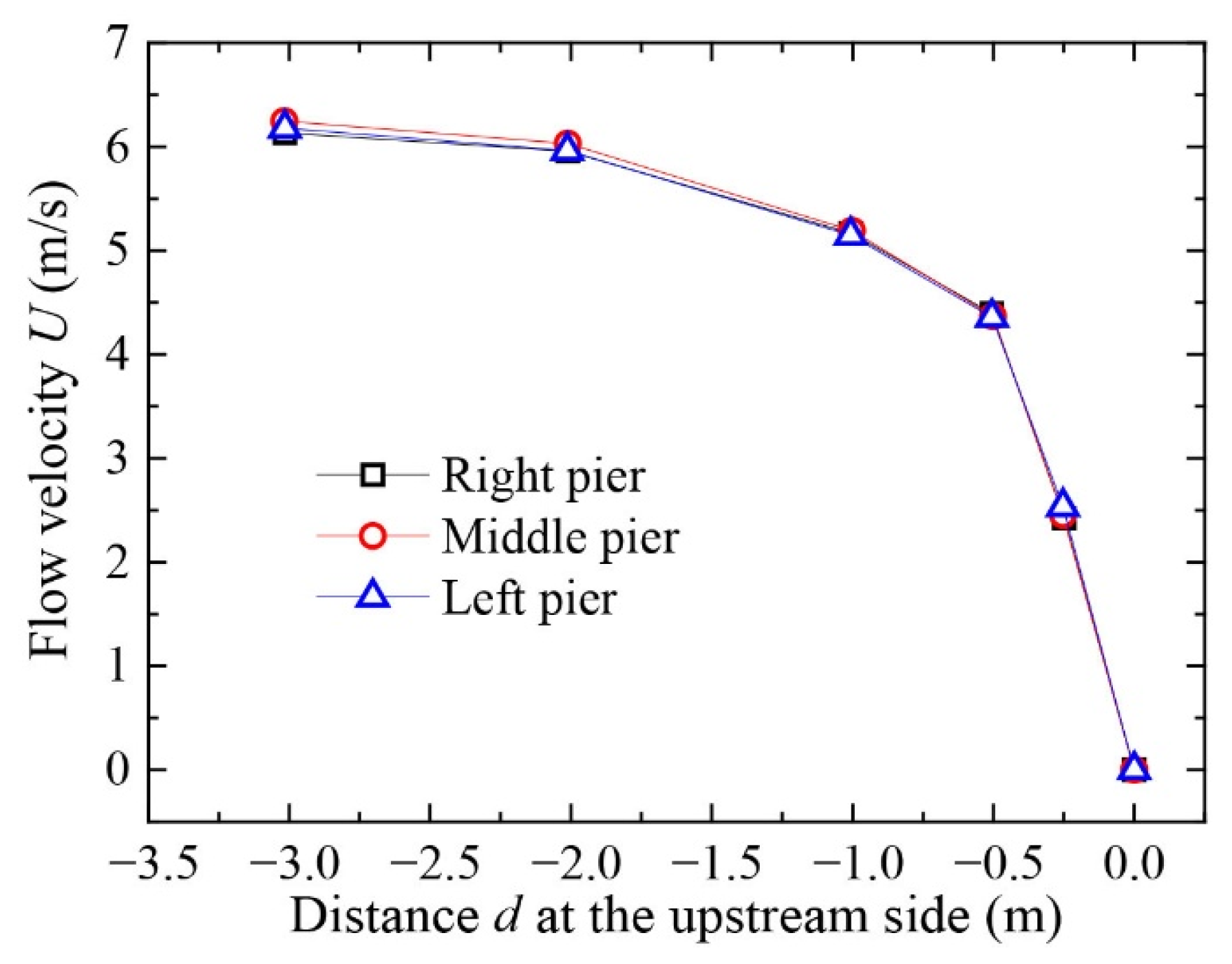

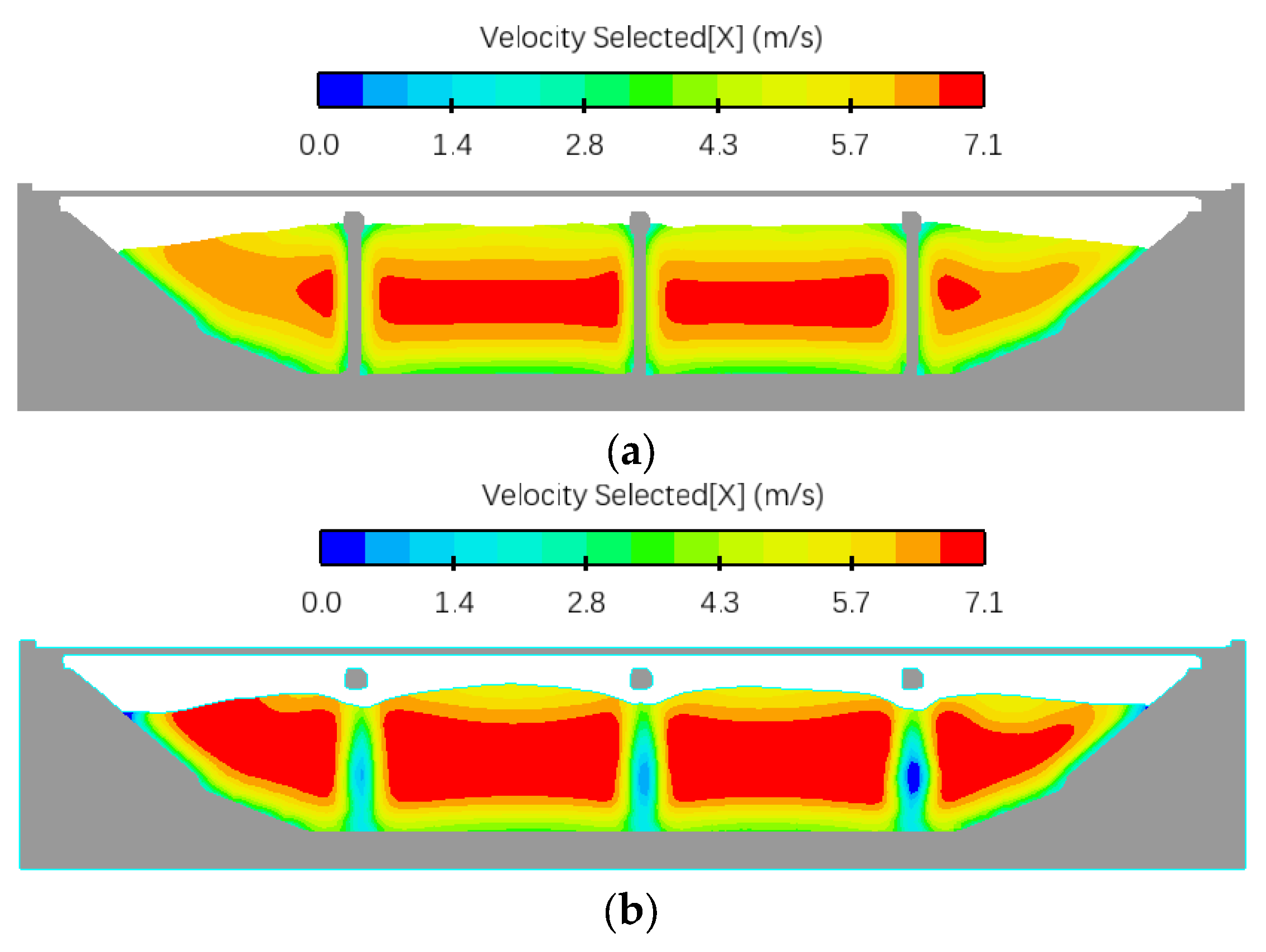

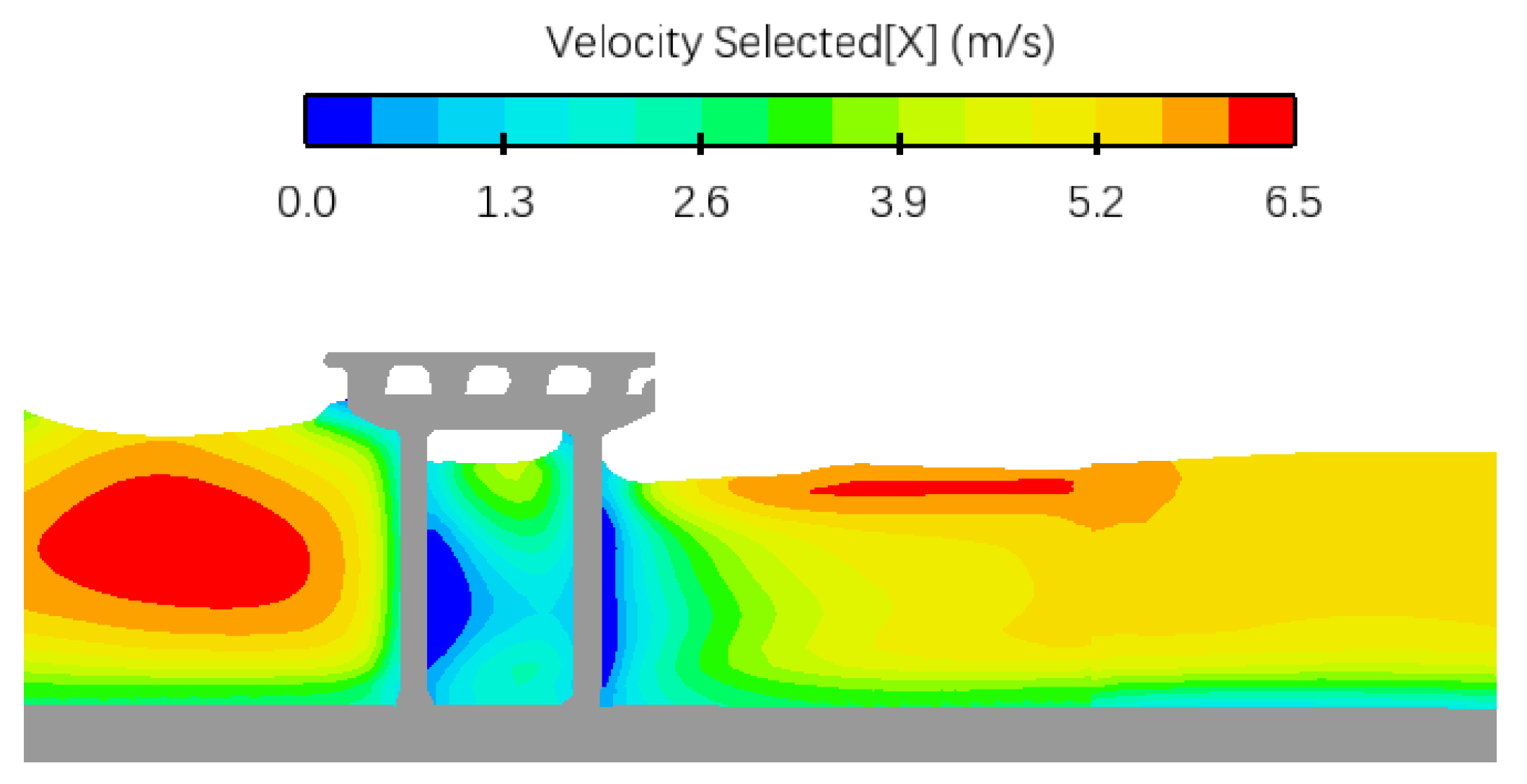

3.2.2. Flow Velocity Distribution at Bridge Site

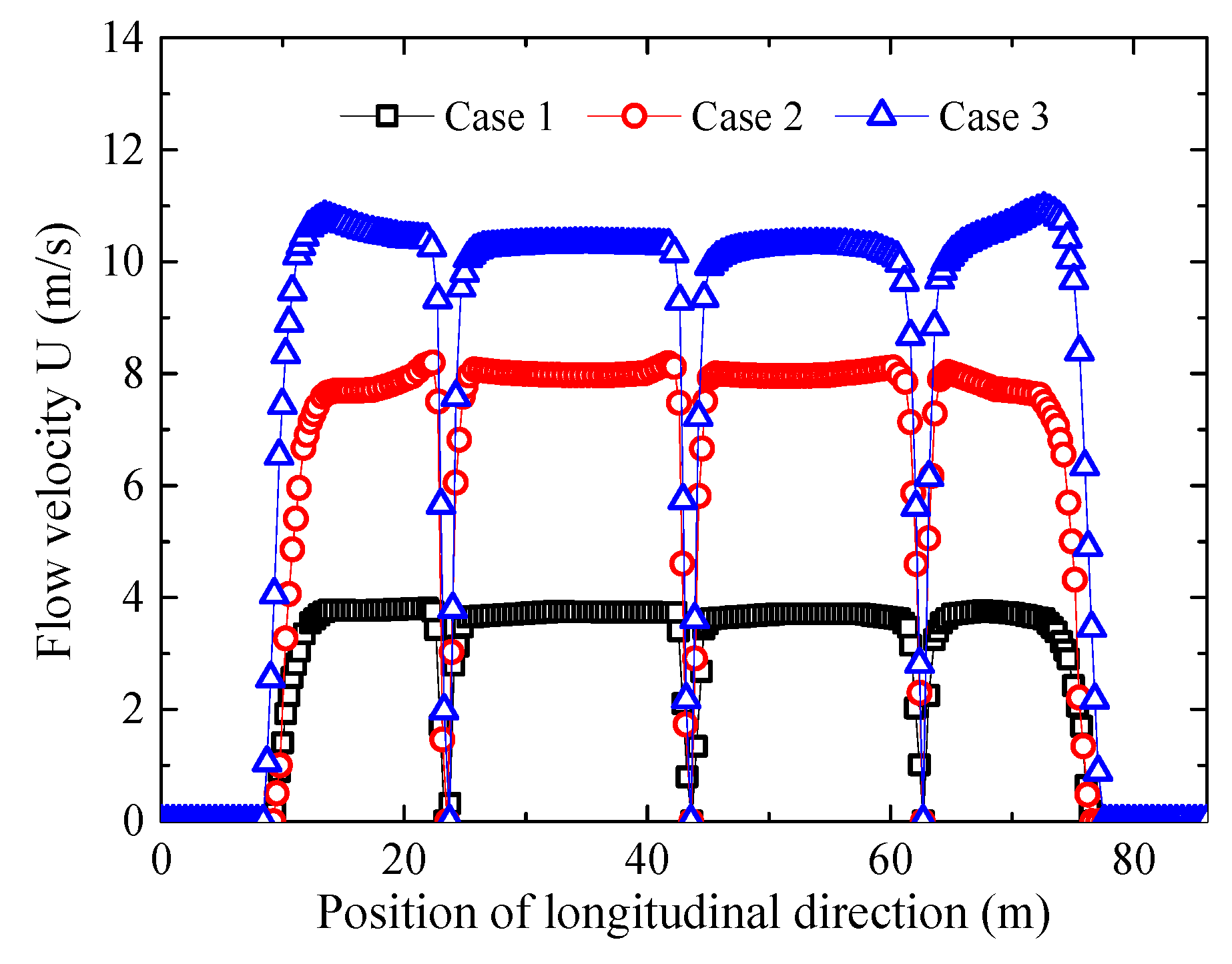

3.2.3. Influence of Different Initial Flow Velocity

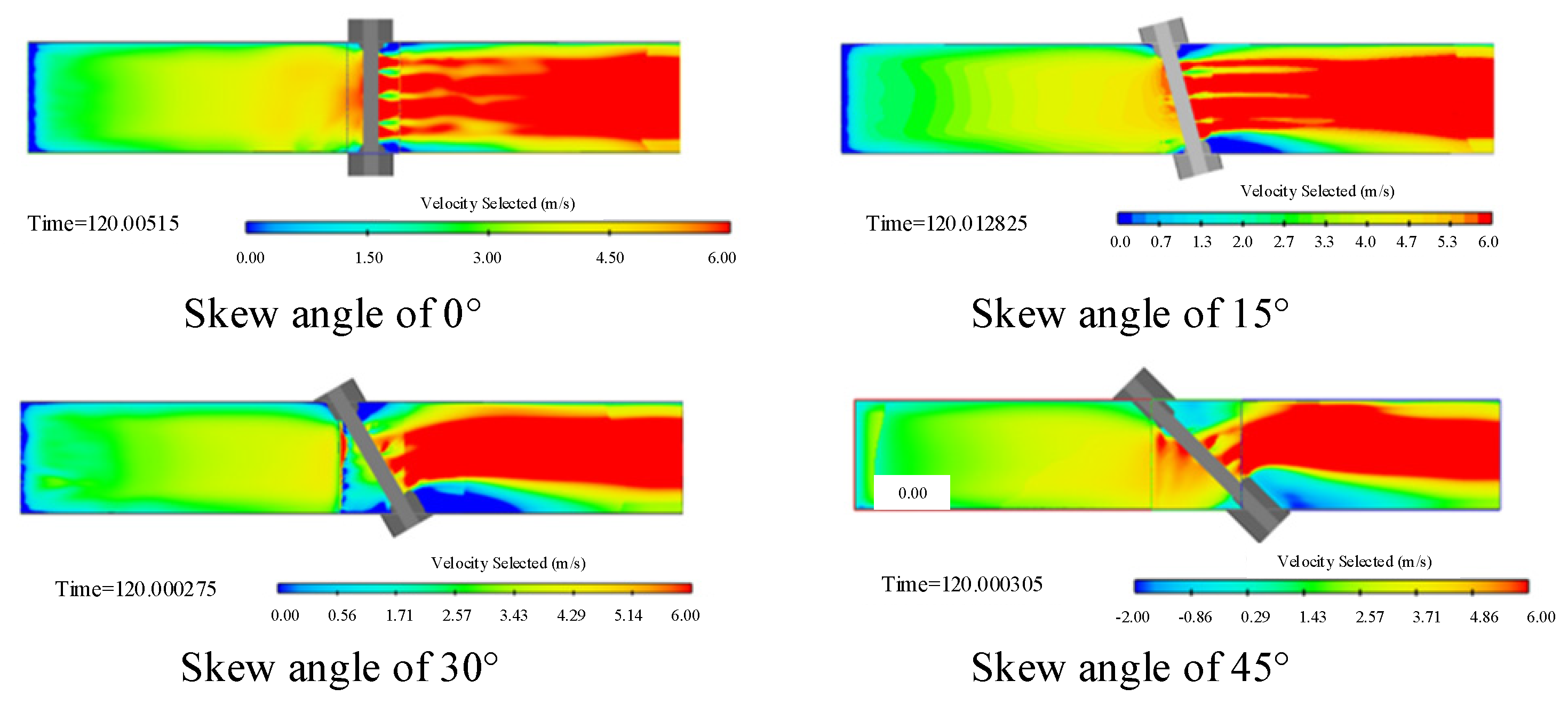

3.3. Effect of Bridge–Channel Skew Angle

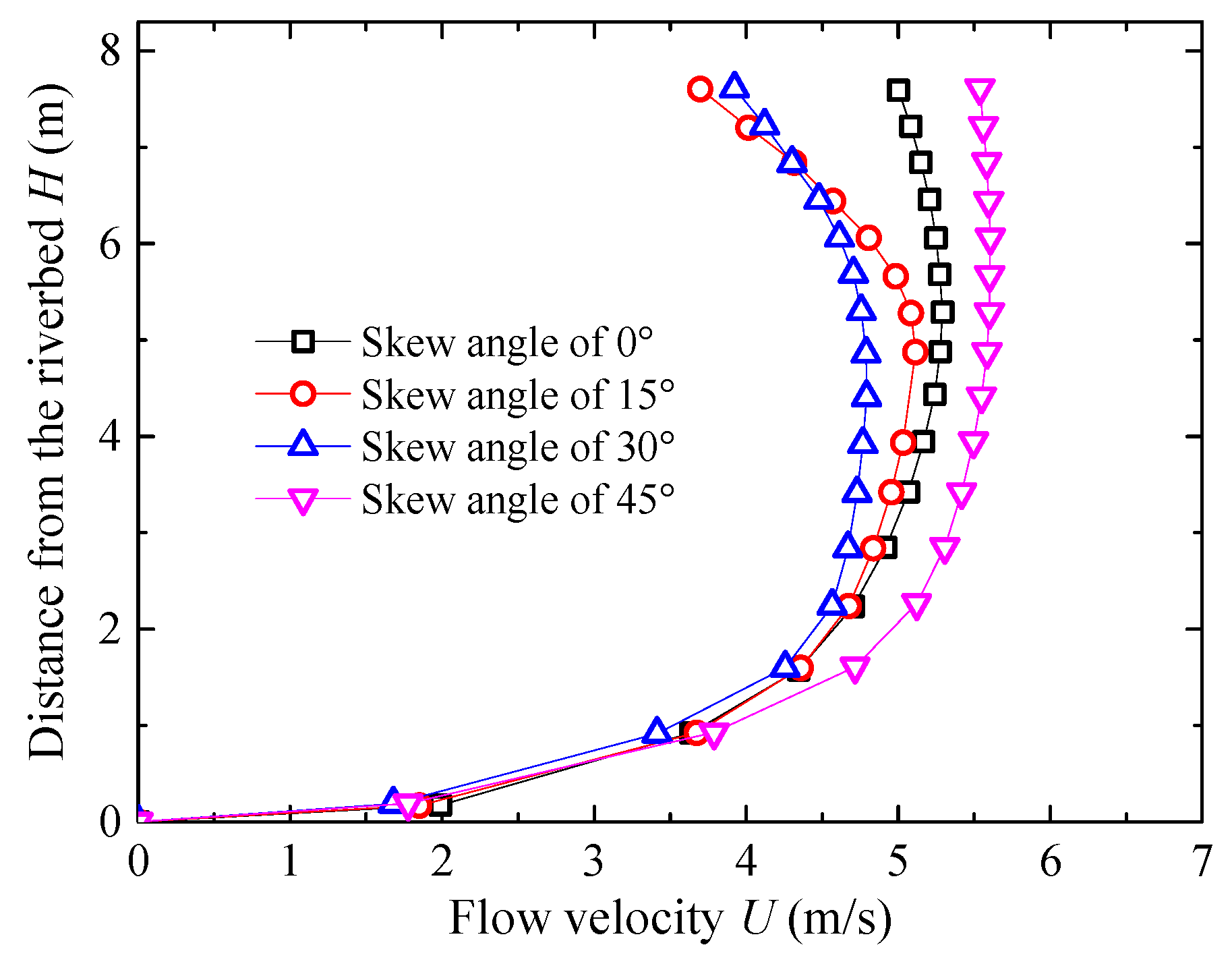

3.3.1. Vertical Flow Velocity Distribution at the Upstream Piers

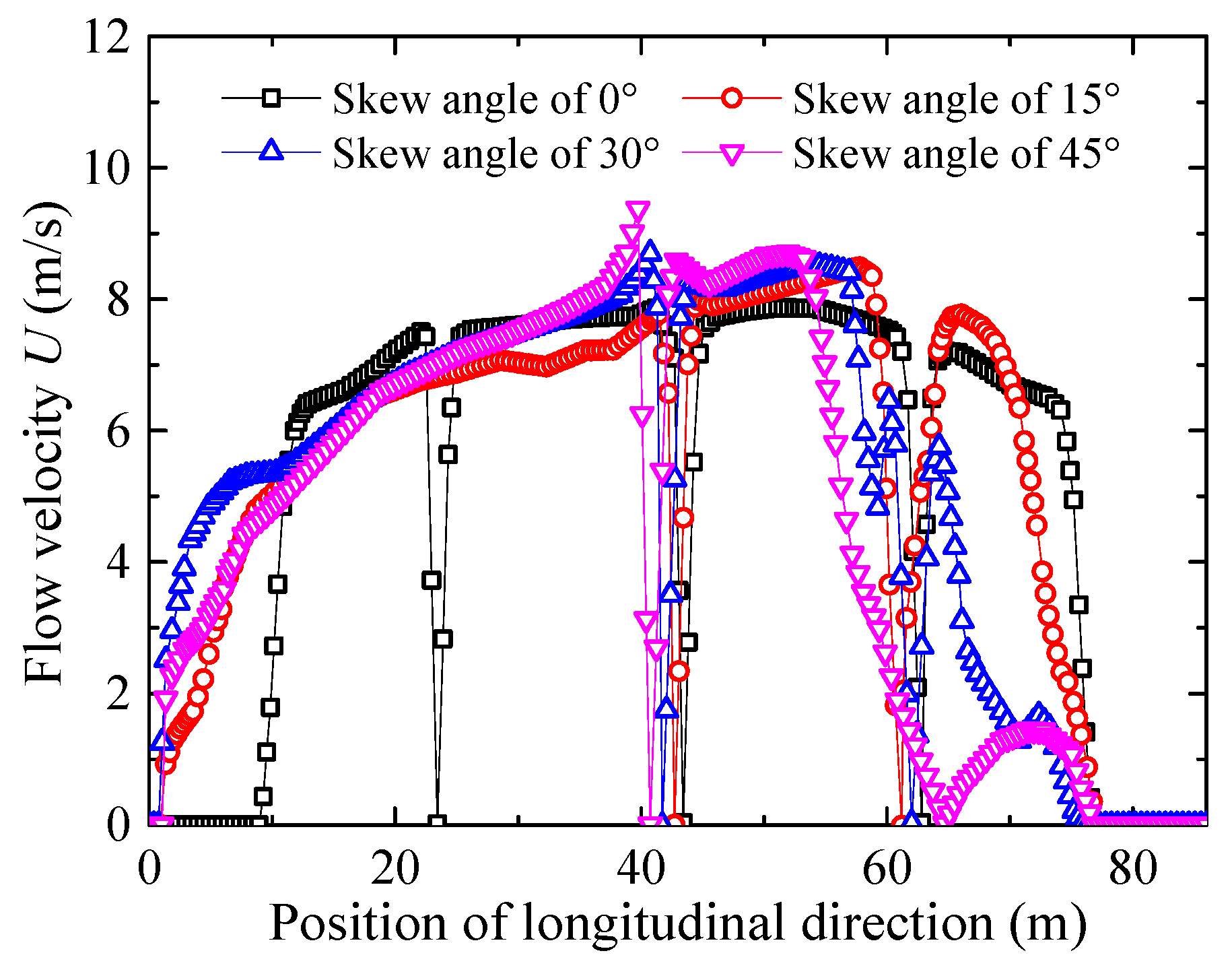

3.3.2. Transverse Flow Velocity Distribution at the Upstream Piers

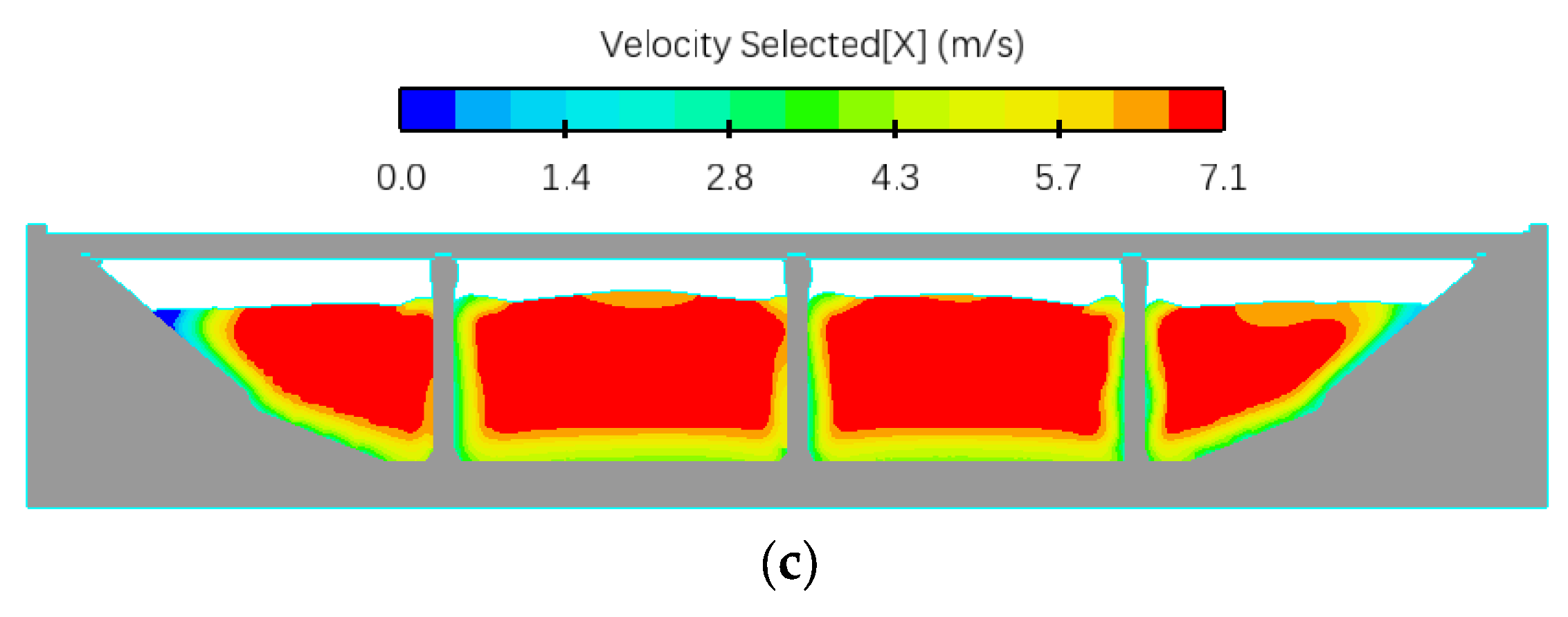

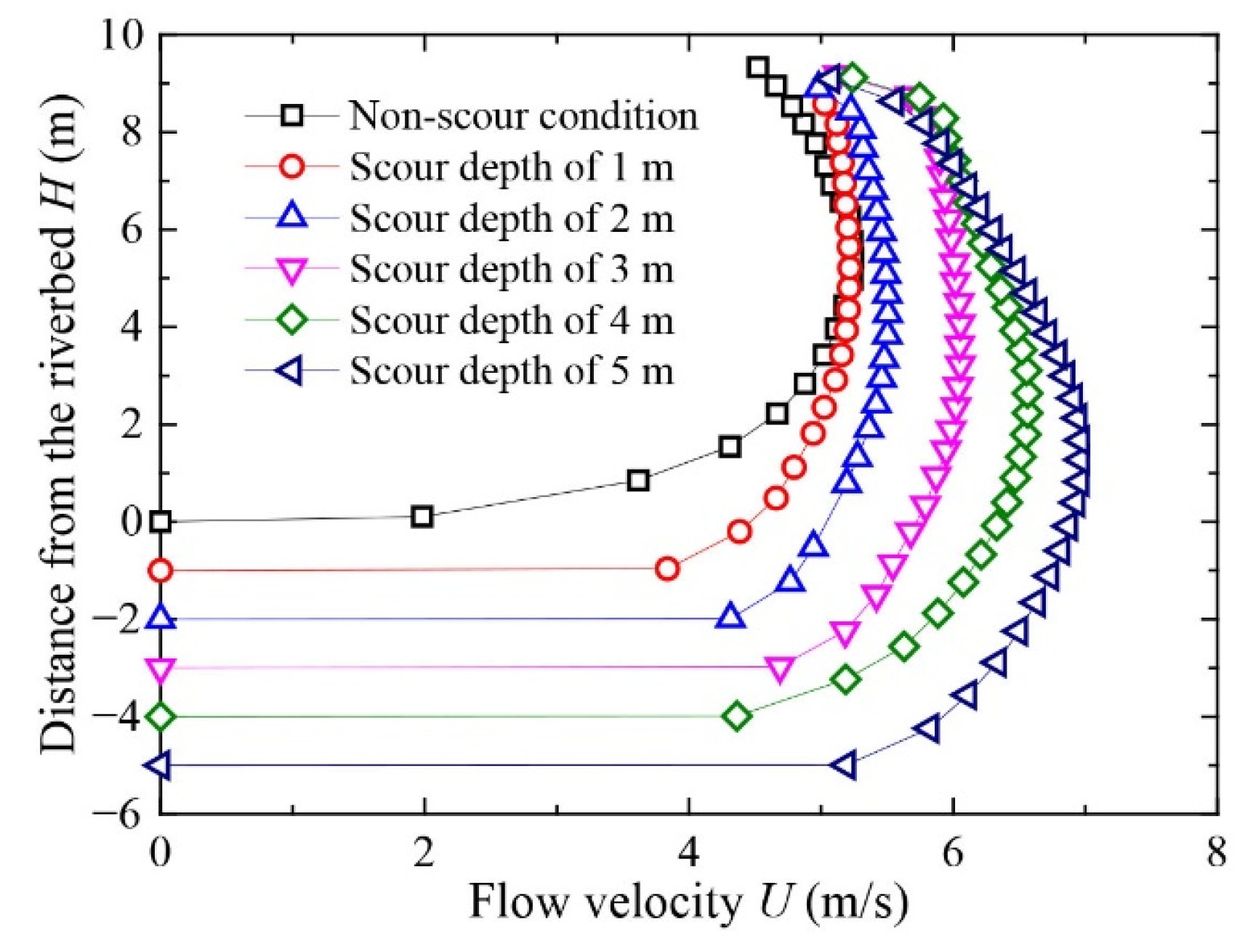

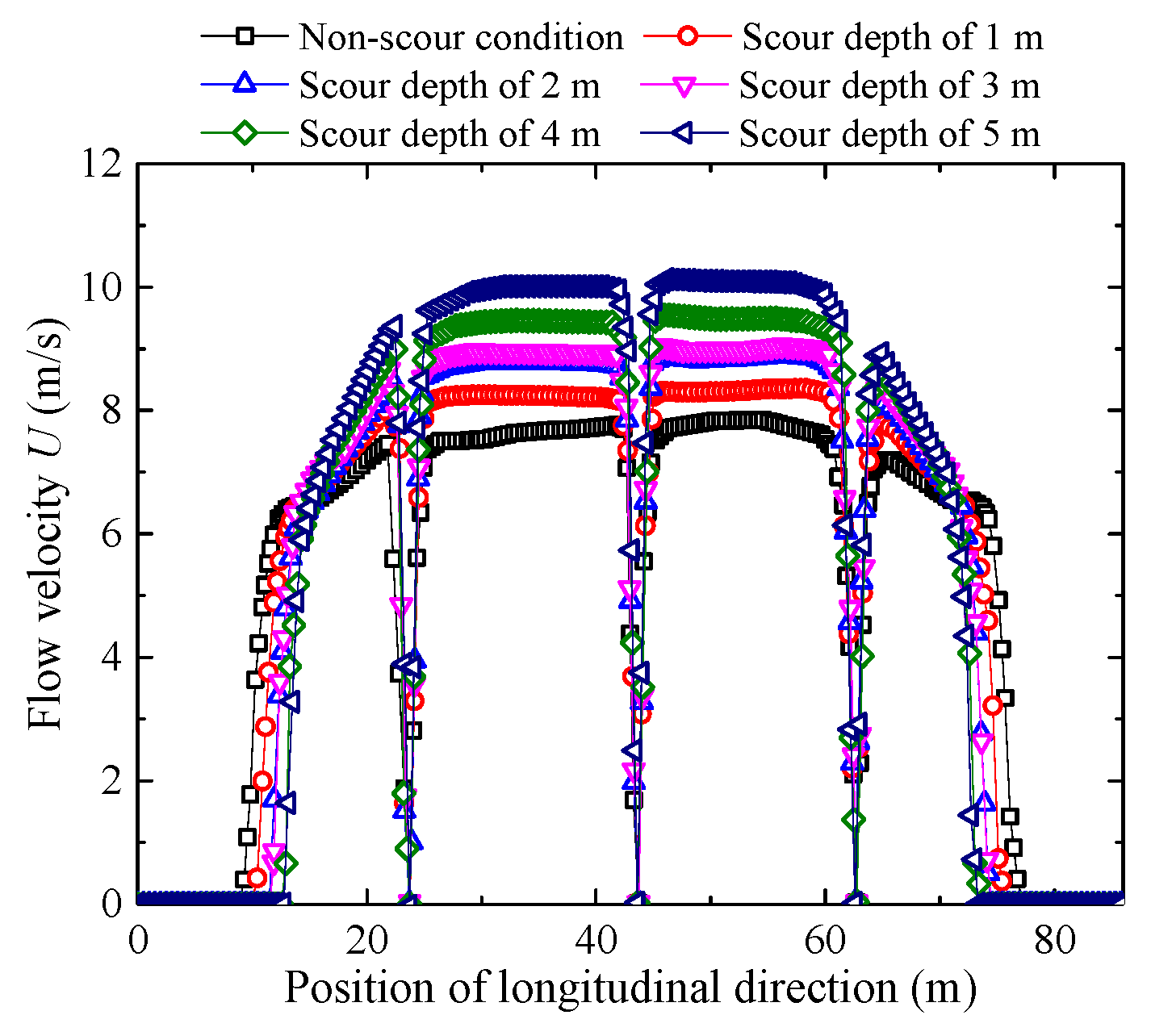

3.4. Effect of Scour Depth

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The vertical flow velocity distribution at the upstream side of the upstream pier gradually increases with increasing distance from the riverbed elevation. In contrast, the vertical flow velocity on the downstream side of the upstream pier and on both sides of the downstream pier exhibits vertically non-uniform development. This is due to the horseshoe vortex and flow disturbance near the upstream pier, which disrupt and dissipate part of the flow’s forward momentum. At the transverse direction, the flow velocity increases slightly between piers when approaching from upstream, but decreases directly in front of the piers. With increasing the initial flow velocity, the vertical and transverse flow velocity distribution at the bridge site will gradually increase.

- (2)

- For the different scenarios with varying bridge–channel skew angles we obtain the following: at larger skew angles, the lateral velocity component suppresses vertical vortices, thereby reducing vertical flow velocity; at smaller skew angles, complex flow separation triggers intense three-dimensional turbulence, enhancing vertical vortices and fluctuating energy, which restores vertical flow velocity.

- (3)

- A greater scour depth increases the peak flow velocity by altering the flow field and its resistance properties. Deeper scouring enhances the channel’s confinement, which reduces flow energy loss and initiates acceleration further upstream. This leads to a significantly higher and steeper acceleration peak as the channel morphology becomes more pronounced.

- (4)

- The findings in this research primarily apply to bridges with circular piers. For piers of different shapes, alterations in flow disturbance characteristics may influence the development patterns of hydraulic conditions at the bridge site. In future work, unsteady flow simulations incorporating flood hydrographs derived from actual events will be performed to analyze how the rate of flow change and flood duration affect the hydraulic conditions at bridge sites.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Edgare, M.D.; Federico, N.M.; Mohammadi, J. Investigation of common causes of bridge collapse in Colombia. Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 2009, 14, 194–200. [Google Scholar]

- Wardhana, K.; Hadipriono, F.C. Analysis of recent bridge failures in the United States. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2003, 17, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Cai, C.; Zhang, R. Review of hydraulic bridge failures. China J. Highw. Transp. 2021, 34, 10–28. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.; Wang, W.; Yu, Y. State-of-the-art review on the causes and mechanisms of bridge collapse. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2016, 30, 04015005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Lan, S.; Yang, J. Causes and statistical characteristics of bridge failures: A review. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2022, 9, 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Cai, C.; Zhang, R.; Shi, H.; Xu, C. Review of hydraulic bridge failures: Historical statistic analysis, failure modes, and prediction methods. J. Bridge Eng. 2023, 28, 03123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Xiong, W.; Ma, X.; Cai, C. Progressive bridge collapse analysis under both scour and floods by coupling simulation in structural and hydraulic fields. Part I: Numerical solver. Ocean Eng. 2023, 273, 113849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, A.R.; Montoya, B.M.; Ortiz, A.C.; Gabr, M.A. Quantifying probability of deceedance estimates of clear water local scour around bridge piers. J. Hydrol. 2021, 597, 126177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro, A.; Manfreda, S.; Tubaldi, E. The science behind scour at bridge foundations: A review. Water 2020, 12, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yu, X.; Liang, F. A review of bridge scour: Mechanism, estimation, monitoring and countermeasures. Nat. Hazards 2017, 87, 1881–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, A.R.; Gabr, M.A.; Montoya, B.M.; Ortiz, A.C. Local scour around bridge abutments: Assessment of accuracy and conservatism. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xiong, X.; Melville, B.W.; Sturm, T.W. Dynamic morphology in a bridge-contracted compound channel during extreme floods: Effects of abutments, bed-forms and scour countermeasures. J. Hydrol. 2021, 594, 125930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajikawa, Y. Numerical simulation of flow and local scour around structures in steep channels using two-and three-dimensional hydrodynamic models. Water 2025, 17, 3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinga, J.V.; Alipour, A. Assessment of structural integrity of bridges under extreme scour conditions. Eng. Struct. 2015, 82, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, J.; Hager, W.H. Down-flow and horseshoe vortex characteristics of sediment embedded bridge piers. Exp. Fluids 2007, 42, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Raikar, R.V. Characteristics of horseshoe vortex in developing scour holes at piers. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2007, 133, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargahi, B. Controlling mechanism of local scouring. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1990, 116, 1197–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R.L. Junction flows. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2001, 33, 415–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devenport, W.J.; Simpson, R.L. Time-depeiident and time-averaged turbulence structure near the nose of a wing-body junction. J. Fluid Mech. 1990, 210, 23–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Cheng, L.; Zang, Z. Experimental and numerical investigation of local scour around a submerged vertical circular cylinder in steady currents. Coast. Eng. 2010, 57, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Yin, Z.-Y. Micromechanical analysis of local scour behaviors around circular piles in granular soil under steady flows with SPH-DEM. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 328, 121061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Zhao, M.; Wu, H.; Dhamelia, V. Experimental study of local scour around a compound pile under steady current. Ocean Eng. 2025, 318, 120151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Hydrological Specifications for Survey and Design of Highway Engineering; China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arneson, L.; Zevenbergen, L.; Lagasse, P.; Clopper, P. Evaluating Scour at Bridges, 5th ed.; National Highway Institute (US): Vienna, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Melville, B.W. Pier and abutment scour: Integrated approach. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1997, 123, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, D.M.; Miller, W., Jr. Live-bed local pier scour experiments. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2006, 132, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Wang, C.; Huang, M.; Wang, Y. Experimental observations and evaluations of formulae for local scour at pile groups in steady currents. Mar. Georesources Geotechnol. 2017, 35, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveto, G.; Hager, W.H. Further results to time-dependent local scour at bridge elements. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2005, 131, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, W.H.; Unger, J. Bridge pier scour under flood waves. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2010, 136, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabarestani, M.K.; Zarrati, A.R. Local scour calculation around bridge pier during flood event. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2017, 21, 1462–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, O.; Castillo, C.; Pizarro, A.; Rojas, A.; Ettmer, B.; Escauriaza, C.; Manfreda, S. A model of bridge pier scour during flood waves. J. Hydraul. Res. 2017, 55, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, O.; García, M.; Pizarro, A.; Alcayaga, H.; Palma, S. Local scour and sediment deposition at bridge piers during floods. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2020, 146, 04020003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, B. The physics of local scour at bridge piers. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Scour and Erosion, Tokyo, Japan, 5–7 November 2008; pp. 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.O.; Sturm, T.W. Effect of sediment size scaling on physical modeling of bridge pier scour. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2009, 135, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayasree, B.; Eldho, T.; Mazumder, B.; Ahmad, N. Influence of bridge pier shape on flow field and scour geometry. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2019, 17, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. General Specifications for Design of Highway Bridges and Culverts; China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Technical Standard of Highway Engineering; China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Investigation and Assessment Team. Investigation and Assessment Report on the July 19 Highway Bridge Collapse Disaster in Shangluo, Shaanxi. 2024, 36p. Available online: https://jtyst.qinghai.gov.cn/jtyst/2025-07/29/article_2025072915040382114.html (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Qiu, M.; Ostfeld, A. A head formulation for the steady-state analysis of water distribution systems using an explicit and exact expression of the Colebrook-White equation. Water 2021, 13, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanson, H. Hydraulics of Open Channel Flow; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nezu, I.; Rodi, W. Open-channel flow measurements with a laser Doppler anemometer. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1986, 112, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Wang, E.; Dong, Z.; Li, G. Discussion and application of velocity profile in open channel with rectangular cross-section. J. Hydrodyn. 2004, 19, 144–151. [Google Scholar]

| Position | Setup Status |

|---|---|

| Inlet boundary condition | Specified velocity boundary, different initial flow velocity for different conditions |

| Outlet boundary condition | Specified pressure boundary |

| Free surface treatment | Solving the transport equation of the volume fraction |

| Case | Initial Flow Velocity U0 (m/s) | Skew Angle θ | Water Depth H0 (m) | Froude Number Fr | Reynold Number Re |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 90 | 8 | 0.34 | 2.40 × 107 |

| 2 | 6 | 90 | 8 | 0.68 | 4.80 × 107 |

| 3 | 9 | 90 | 8 | 1.02 | 7.20 × 107 |

| Scenario | Initial Flow Velocity U0 (m/s) | Skew Angle θ | Water Depth H0 (m) | Froude Number Fr | Reynold Number Re |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 0 | 8 | 0.68 | 4.80 × 107 |

| 2 | 6 | 15 | 8 | 0.68 | 4.80 × 107 |

| 3 | 6 | 30 | 8 | 0.68 | 4.80 × 107 |

| 4 | 6 | 45 | 8 | 0.68 | 4.80 × 107 |

| Ad | λ | Bc/Bcg | Q2/Qc | hcm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.995 | 0.065 | 0.9 | 1 | 8 |

| Initial Flow Velocity U0 (m/s) | Compression Coefficient μ | Initial Water Depth (m) | Water Depth After Scouring hp (m) | Scour Depth (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 0.82 | 8 | 8.47 | 0.47 |

| 6 | 0.88 | 8 | 9.05 | 1.05 |

| 9 | 0.94 | 8 | 9.71 | 1.71 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Li, W.; Li, P.; Jin, X.; Liu, Y. Evolution Pattern of Hydraulic Characteristics at a Bridge Site: The Influence of Key Flood Factors. Water 2026, 18, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020155

Li Z, Li W, Li P, Jin X, Liu Y. Evolution Pattern of Hydraulic Characteristics at a Bridge Site: The Influence of Key Flood Factors. Water. 2026; 18(2):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020155

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zhenchuan, Wanheng Li, Pengfei Li, Xuanji Jin, and Yao Liu. 2026. "Evolution Pattern of Hydraulic Characteristics at a Bridge Site: The Influence of Key Flood Factors" Water 18, no. 2: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020155

APA StyleLi, Z., Li, W., Li, P., Jin, X., & Liu, Y. (2026). Evolution Pattern of Hydraulic Characteristics at a Bridge Site: The Influence of Key Flood Factors. Water, 18(2), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020155