Spatio-Temporal Variation in Water Quality in Urban Lakes and Land Use Driving Impact: A Case Study of Wuhan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

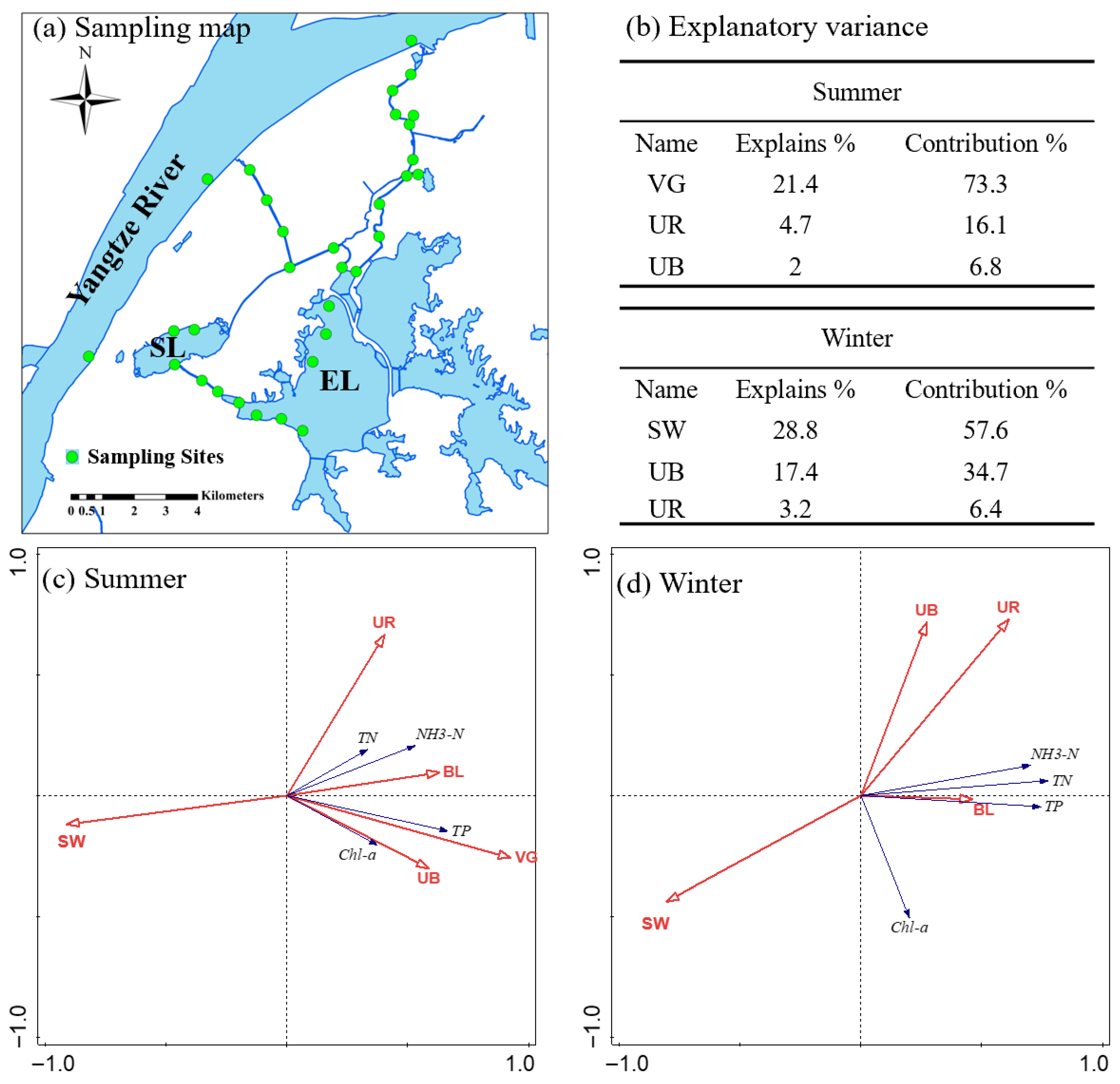

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Water Quality Index (WQI) Assessment

2.3.2. Spearman Correlation Analysis

2.3.3. Land Coverage

2.3.4. Redundancy Analysis (RDA)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Temporal and Spatial Variation Characteristics of Major Pollutants

3.1.1. Inter-Annual Variation Feature

3.1.2. Seasonal Variation Feature

3.1.3. Spatial Distribution of Crucial Pollutants

3.2. Water Quality Evaluation

3.2.1. Single Factor Evaluation Method

3.2.2. WQI

3.3. Correlation Analysis of Water Quality Parameters

3.4. Analysis of Water Pollution Causes Based on Land Use

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costadone, L.; Sytsma, M.D.; Costadone, L.; Sytsma, M.D. Lake and Reservoir Management Identification and Characterization of Urban Lakes across the Continental United States. Lake Reserv. Manag. 2022, 38, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, Y. Urban Lake Health Assessment Based on the Synergistic Perspective of Water Environment and Social Service Functions. Glob. Chall. 2024, 8, 2400144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Wan, H.; Cai, Y.; Peng, J.; Li, B.; Jia, Q.; Yuan, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Hong, B.; et al. Human Activities Affect the Multidecadal Microplastic Deposition Records in a Subtropical Urban Lake, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 820, 153187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, Y.; Yu, X.; Liu, L.; Ning, Y.; Bi, X.; Liu, J. Effects of Hydrological Connectivity Project on Heavy Metals in Wuhan Urban Lakes on the Time Scale. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 853, 158654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyhenmeyer, G.A.; Chukwuka, A.V.; Anneville, O.; Brookes, J.; Carvalho, C.R.; Cotner, J.B.; Grossart, H.P.; Hamilton, D.P.; Hanson, P.C.; Hejzlar, J.; et al. Global Lake Health in the Anthropocene: Societal Implications and Treatment Strategies Earth’s Future. Earth’s Future 2024, 12, e2023EF004387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shao, H.; Guo, Y.; Bi, H.; Lei, X.; Dai, S.; Mao, X.; Xiao, K.; Liao, X.; Xue, H. Ecological Restoration for Eutrophication Mitigation in Urban Interconnected Water Bodies: Evaluation, Variability and Strategy. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Wijesiri, B.; Jia, Z.; Li, Y.; Goonetilleke, A. Re-Thinking Classical Mechanistic Model for Pollutant Build-up on Urban Impervious Surfaces. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Chang, X.; Duan, T.; Wang, X.; Wei, T.; Li, Y. Water Quality Responses to Rainfall and Surrounding Land Uses in Urban Lakes. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 298, 113514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Kollányi, L.; Zhang, J.; Bai, T. Analyzing and Forecasting Water-Land Dynamics for Sustainable Urban Developments: A Multi-Source Case Study of Lake Dianchi’s Environmental Challenges (China). Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Jiang, C.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Zheng, L. Combining Hydrochemistry and Hydrogen and Oxygen Stable Isotopes to Reveal the Influence of Human Activities on Surface Water Quality in Chaohu Lake Basin. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 312, 114933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Wan, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, N.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y. Water Quality Variation and Driving Factors Quantitatively Evaluation of Urban Lakes during Quick Socioeconomic Development. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varol, M. Use of Water Quality Index and Multivariate Statistical Methods for the Evaluation of Water Quality of a Stream Affected by Multiple Stressors: A Case Study. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Peng, J.; Gu, T.; Yu, S.; Xu, Z. Lake-Related Ecosystem Services Facing Social—Ecological Risks. People Nat. 2025, 7, 734–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, H.; Irfan, A.; Muhammad, K.; Latif, I.; Komal, B.; Chen, S. Understanding the Dynamics of Natural Resources Rents, Environmental Sustainability, and Sustainable Economic Growth: New Insights from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 58746–58761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Xu, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X. The Driving Mechanism of Diverse Land Use Types on Dissolved Organic Matter Characteristics of Typical Urban Streams from Wuhan City. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wang, S.; Su, B.; Wu, H.; Wang, G. Understanding the Water Quality Change of the Yilong Lake Based on Comprehensive Assessment Methods. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 126, 107714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fu, Z.; Qiao, H.; Liu, F. Assessment of Eutrophication and Water Quality in the Estuarine Area of Lake Wuli, Lake Taihu, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 1392–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo, R.C.; Niswonger, R.G.; Smith, D.; Rosenberry, D.; Chandra, S. Linkages between Hydrology and Seasonal Variations of Nutrients and Periphyton in a Large Oligotrophic Subalpine Lake. J. Hydrol. 2019, 568, 877–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Qi, W. Assessing the Water Quality in Urban River Considering the Influence of Rainstorm Flood: A Case Study of Handan City, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Thompson, A.M.; Selbig, W.R. Predictive Models of Phosphorus Concentration and Load in Stormwater Runoff from Small Urban Residential Watersheds in Fall Season. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 315, 115171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wu, B.; Pan, G.; Xu, J.; Wu, S. Spatial Scale and Seasonal Dependence of Land Use Impacts on Riverine Water Quality in the Huai River Basin, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 20995–21010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yang, G.; Wan, R.; Xu, L. Chlorophyll a Variations and Responses to Environmental Stressors along Hydrological Connectivity Gradients: Insights from a Large Floodplain Lake. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 307, 119566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Zhou, J.; Elser, J.J.; Gardner, W.S.; Deng, J.; Brookes, J.D. Water Depth Underpins the Relative Roles and Fates of Nitrogen and Phosphorus in Lakes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3191–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collos, Y.; Harrison, P.J. Acclimation and Toxicity of High Ammonium Concentrations to Unicellular Algae. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 80, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Nwankwegu, A.S.; Huang, Y.; Norgbey, E.; Paerl, H.W. Evaluating the Phytoplankton, Nitrate, and Ammonium Interactions during Summer Bloom in Tributary of a Subtropical Reservoir. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 110971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filstrup, C.T.; Downing, J.A.; Downing, J.A. Relationship of Chlorophyll to Phosphorus and Nitrogen in Nutrient-Rich Lakes Relationship of Chlorophyll to Phosphorus and Nitrogen in Nutrient-Rich Lakes. Inland Waters 2017, 7, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Xu, H.; Zhu, G.; Zhu, M.; Guo, C.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, Y. Why Do Algal Blooms Intensify under Reduced Nitrogen and Fl Uctuating Phosphorus Conditions: The Underappreciated Role of Non-Algal Light Attenuation. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2023, 68, 2274–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Tong, R.; Sun, W.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, G.; Shrestha, S.; Jin, Y. Anthropogenic Influences on the Water Quality of the Baiyangdian Lake in North China over the Last Decade. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 701, 134929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, Q.; Yao, X.; Yue, Q.; Xu, S. What Drives the Changing Characteristics of Phytoplankton in Urban Lakes: Climate, Hydrology, or Human Disturbance? J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Paramater | Weight | 100, I | 80, II | 60, III | 40, IV | 20, V | 0, Worse Than V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COD (mg/L) | 3 | <15 | <18 | <20 | <30 | <40 | ≥40 |

| TP (mg/L) | 1 | <0.02 | <0.1 | <0.2 | <0.3 | <0.4 | ≥0.4 |

| TN (mg/L) | 2 | <0.2 | <0.5 | <1.0 | <1.5 | <2.0 | ≥2.0 |

| NH3-N (mg/L) | 3 | <0.15 | <0.5 | <1 | <1.5 | <2 | ≥2.0 |

| Chl-a (μg/L) | 3 | <1 | <10 | <15 | <40 | <50 | ≥50 |

| Lakes | FR | BV | PV | RV | UB | RB | UR | BL | IS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EL | 21.68% | 11.17% | 29.71% | 2.91% | 15.13% | 0.00% | 15.04% | 4.37% | 30.17% |

| SL | 3.34% | 16.38% | 16.66% | 5.99% | 16.39% | 0.00% | 39.08% | 2.16% | 55.48% |

| YCL | 50.31% | 4.92% | 2.91% | 8.84% | 9.22% | 0.00% | 22.13% | 1.67% | 31.35% |

| NL | 65.06% | 0.07% | 0.00% | 0.79% | 12.58% | 0.20% | 12.31% | 8.99% | 25.09% |

| YEL | 84.03% | 1.00% | 0.00% | 0.16% | 0.11% | 4.15% | 2.49% | 8.06% | 6.75% |

| YWL | 65.89% | 3.54% | 0.51% | 0.73% | 16.24% | 0.19% | 7.01% | 5.90% | 23.44% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

He, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, X. Spatio-Temporal Variation in Water Quality in Urban Lakes and Land Use Driving Impact: A Case Study of Wuhan. Water 2026, 18, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020153

He Y, Zhang H, Chen Q, Zhang X. Spatio-Temporal Variation in Water Quality in Urban Lakes and Land Use Driving Impact: A Case Study of Wuhan. Water. 2026; 18(2):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020153

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Yanfeng, Hui Zhang, Qiang Chen, and Xiang Zhang. 2026. "Spatio-Temporal Variation in Water Quality in Urban Lakes and Land Use Driving Impact: A Case Study of Wuhan" Water 18, no. 2: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020153

APA StyleHe, Y., Zhang, H., Chen, Q., & Zhang, X. (2026). Spatio-Temporal Variation in Water Quality in Urban Lakes and Land Use Driving Impact: A Case Study of Wuhan. Water, 18(2), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020153