Geospatial Assessment and Modeling of Water–Energy–Food Nexus Optimization for Sustainable Paddy Cultivation in the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka: A Case Study in the North Central Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

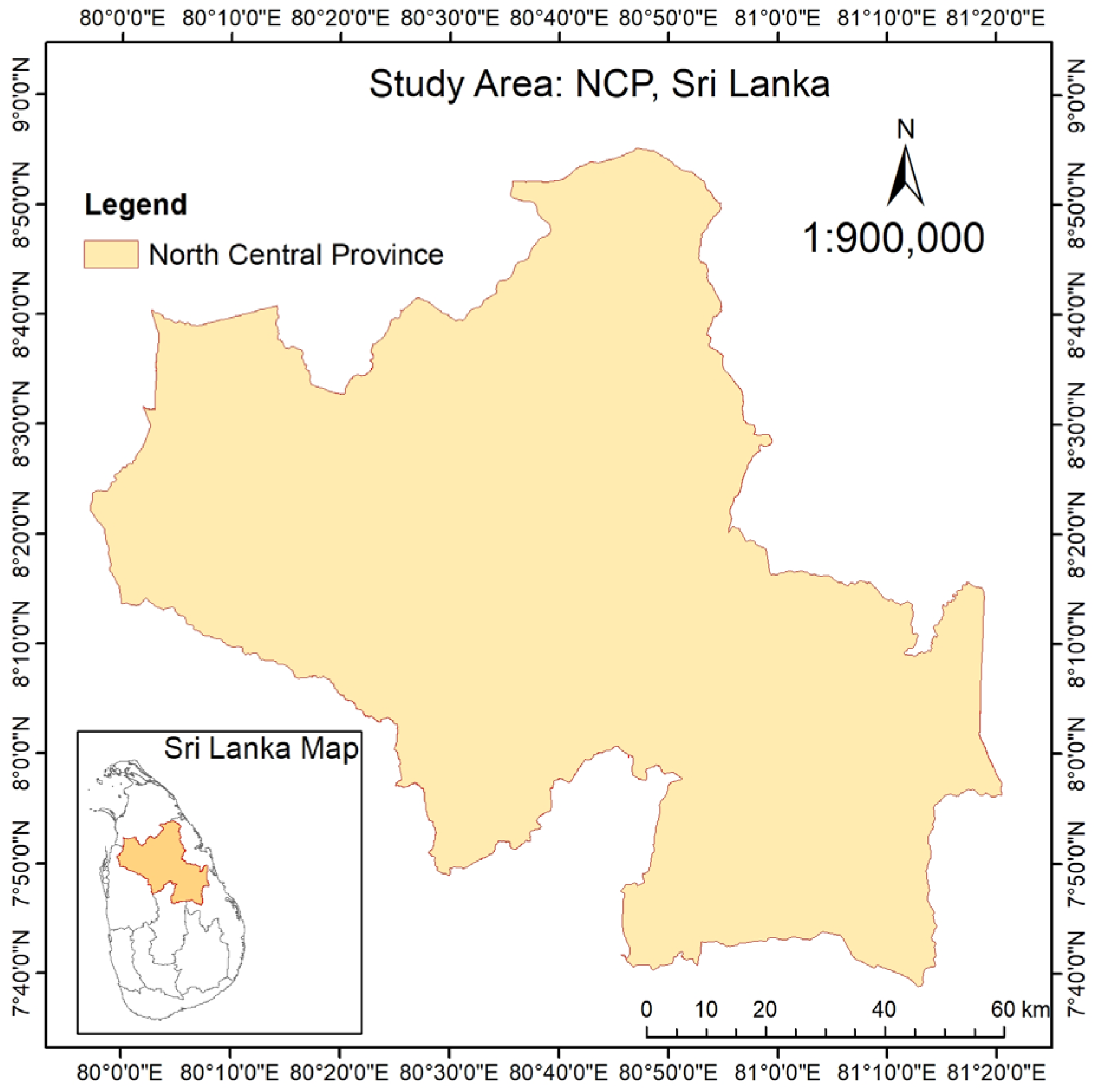

2.1. Study Area

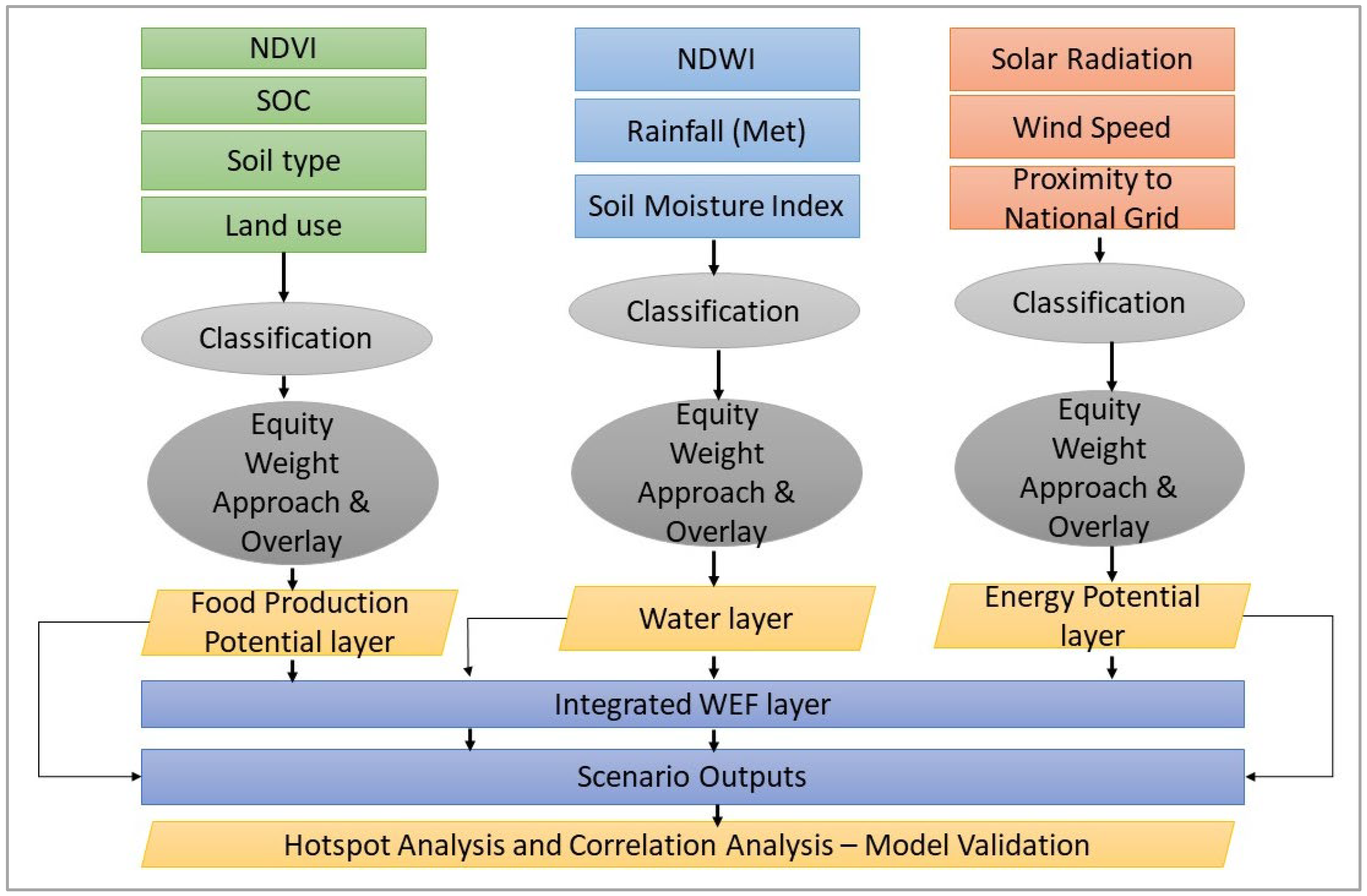

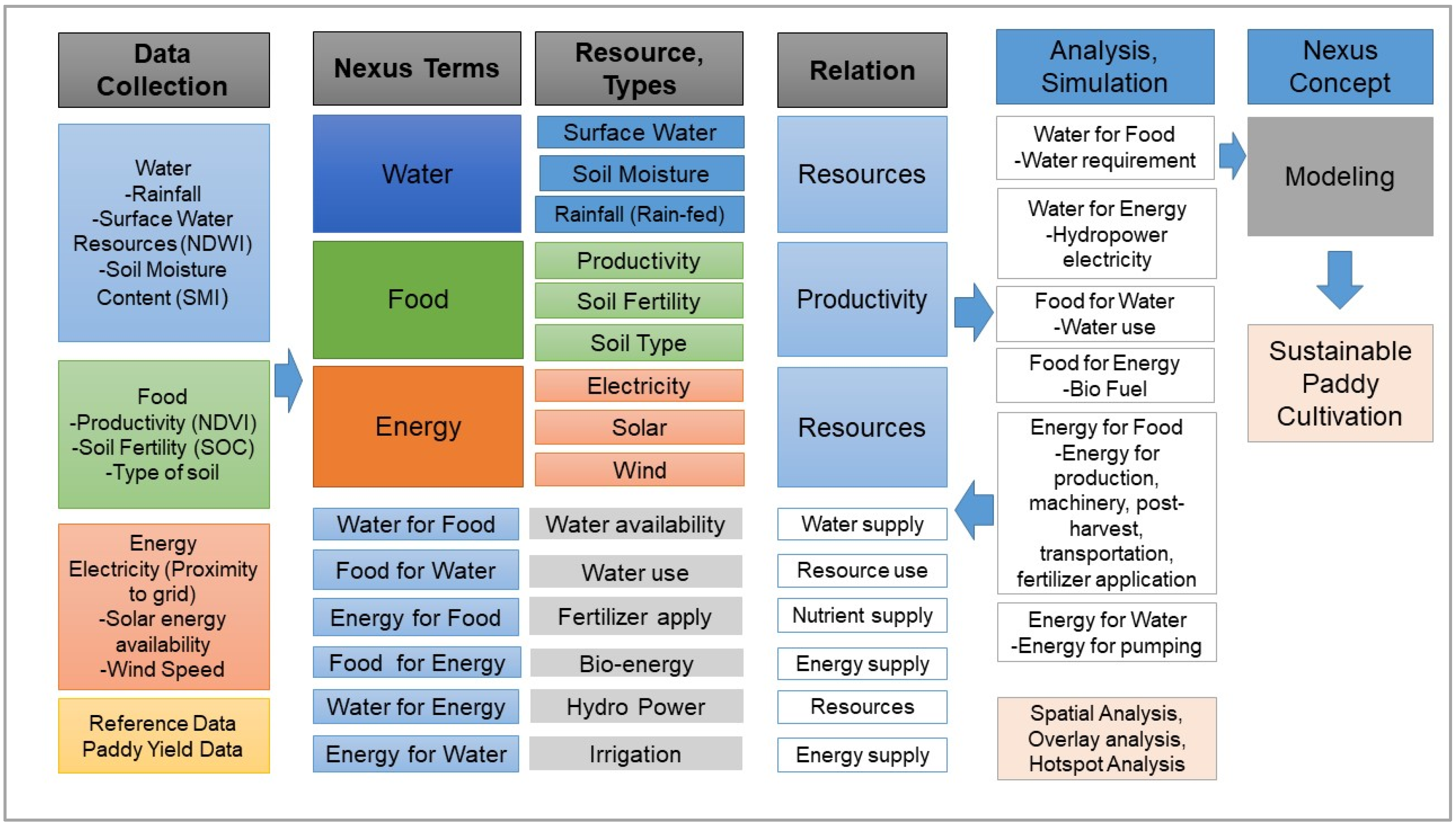

2.2. Data Collection and Method

2.3. Derivation of Remote Sensing Indices

- (a)

- Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)

- (b)

- Normalized Difference Water Index

- (c)

- Normalized Difference Infrared Index (NDII)-based Soil Moisture Index (SMI)

2.4. Construction of WEF Layers

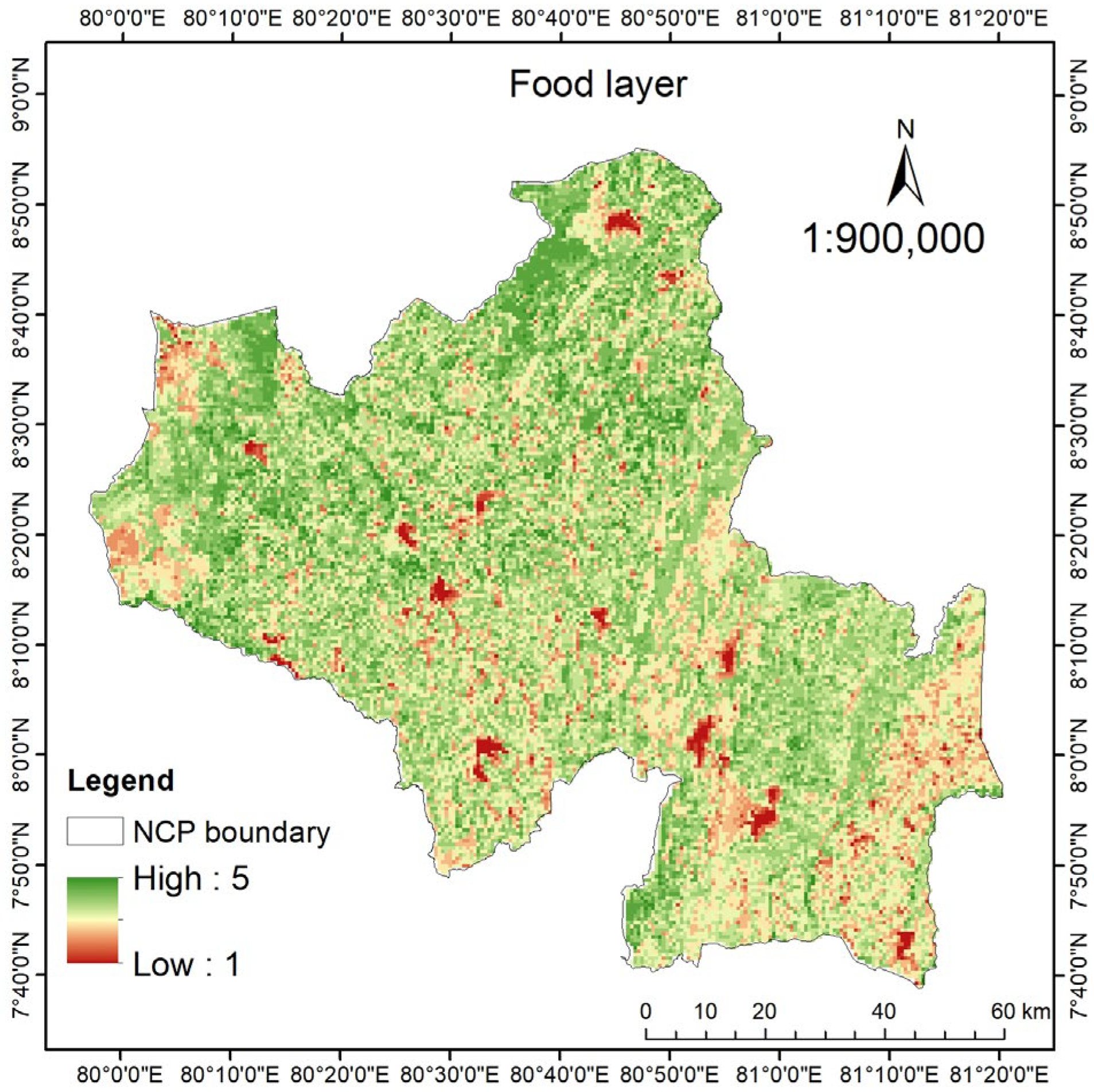

2.4.1. Food Layer

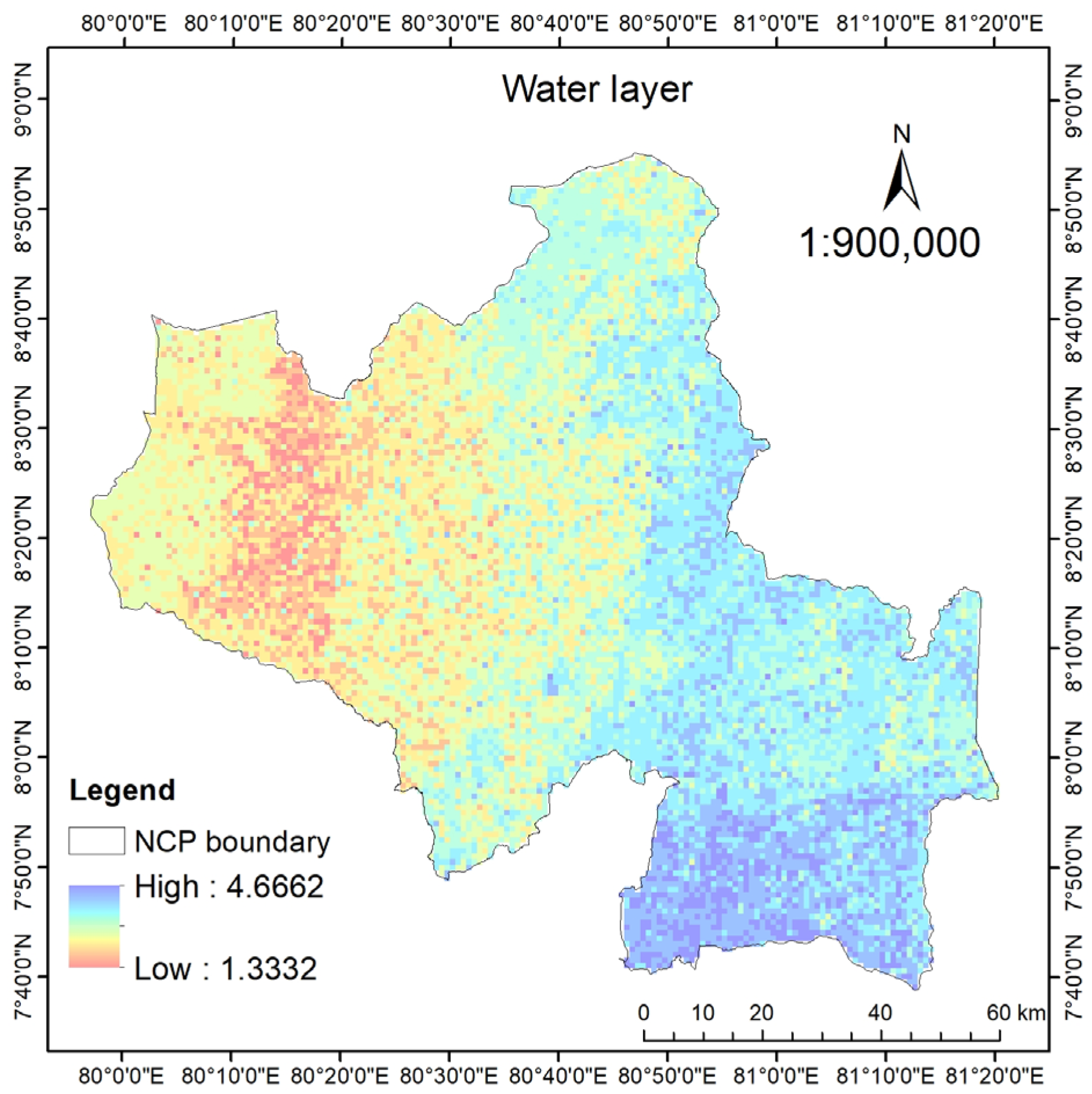

2.4.2. Water Layer

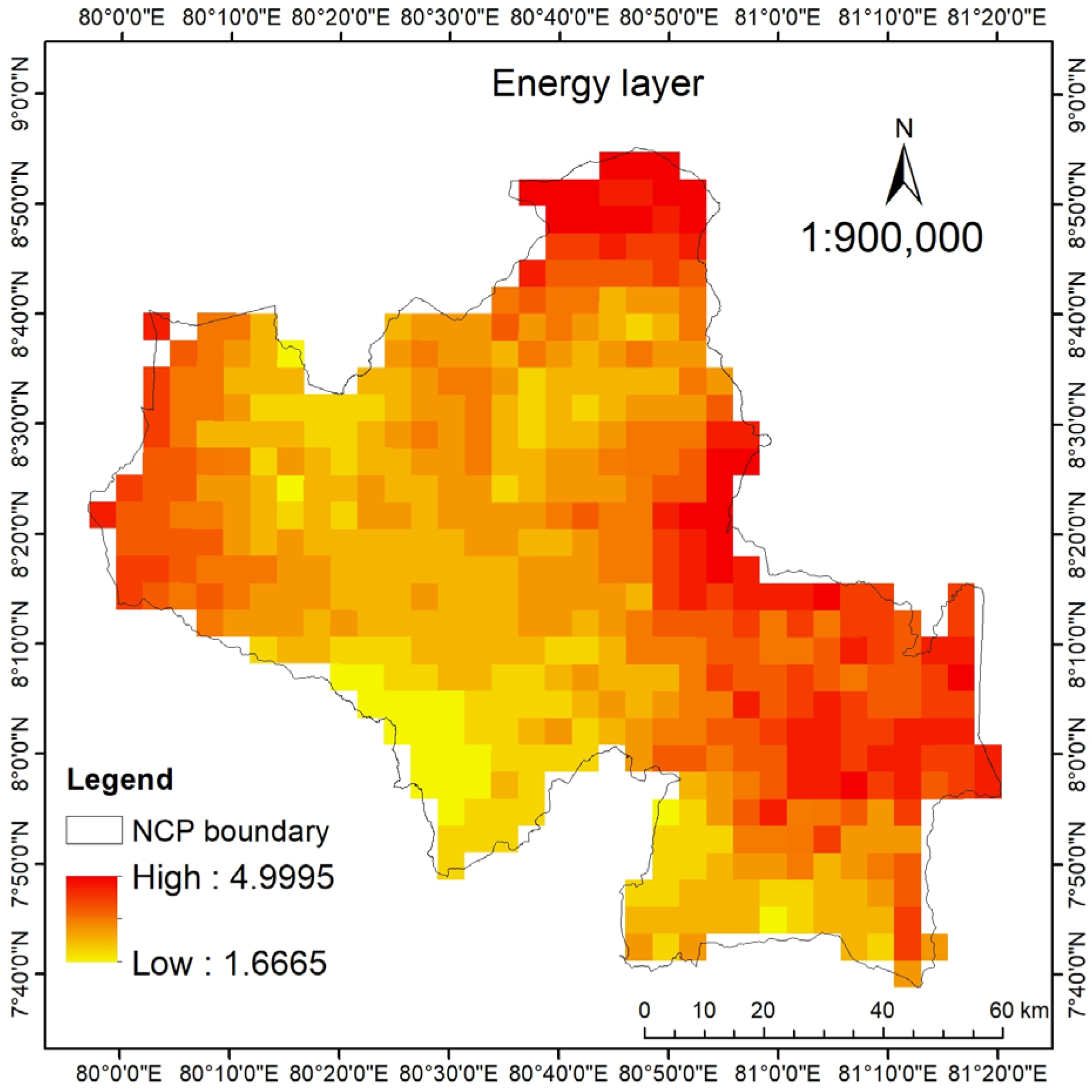

2.4.3. Energy Layer

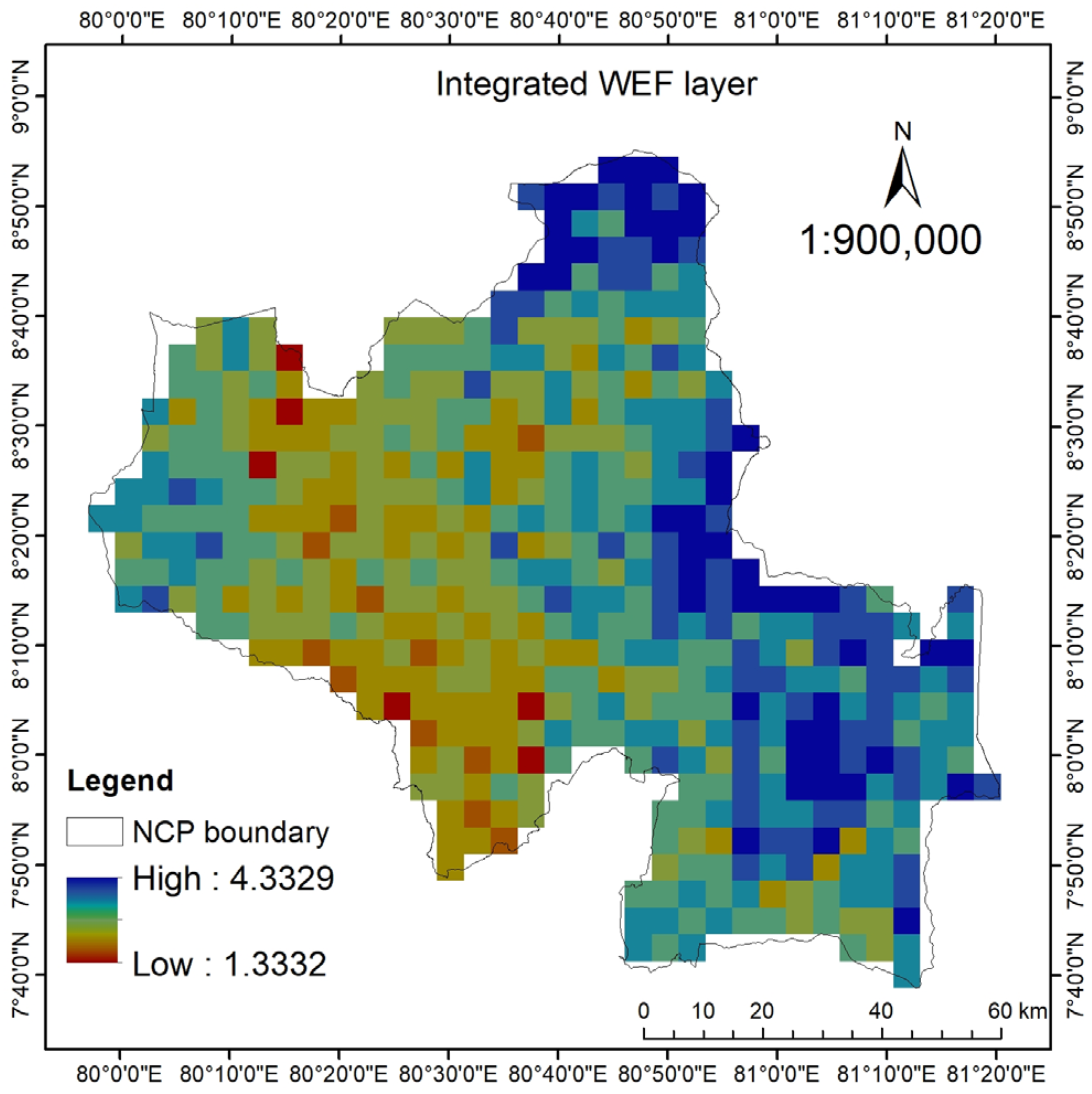

2.5. Spatial Overlay and Nexus Integration

2.6. Scenario Creation

2.7. Hotspot Analysis and Model Validation

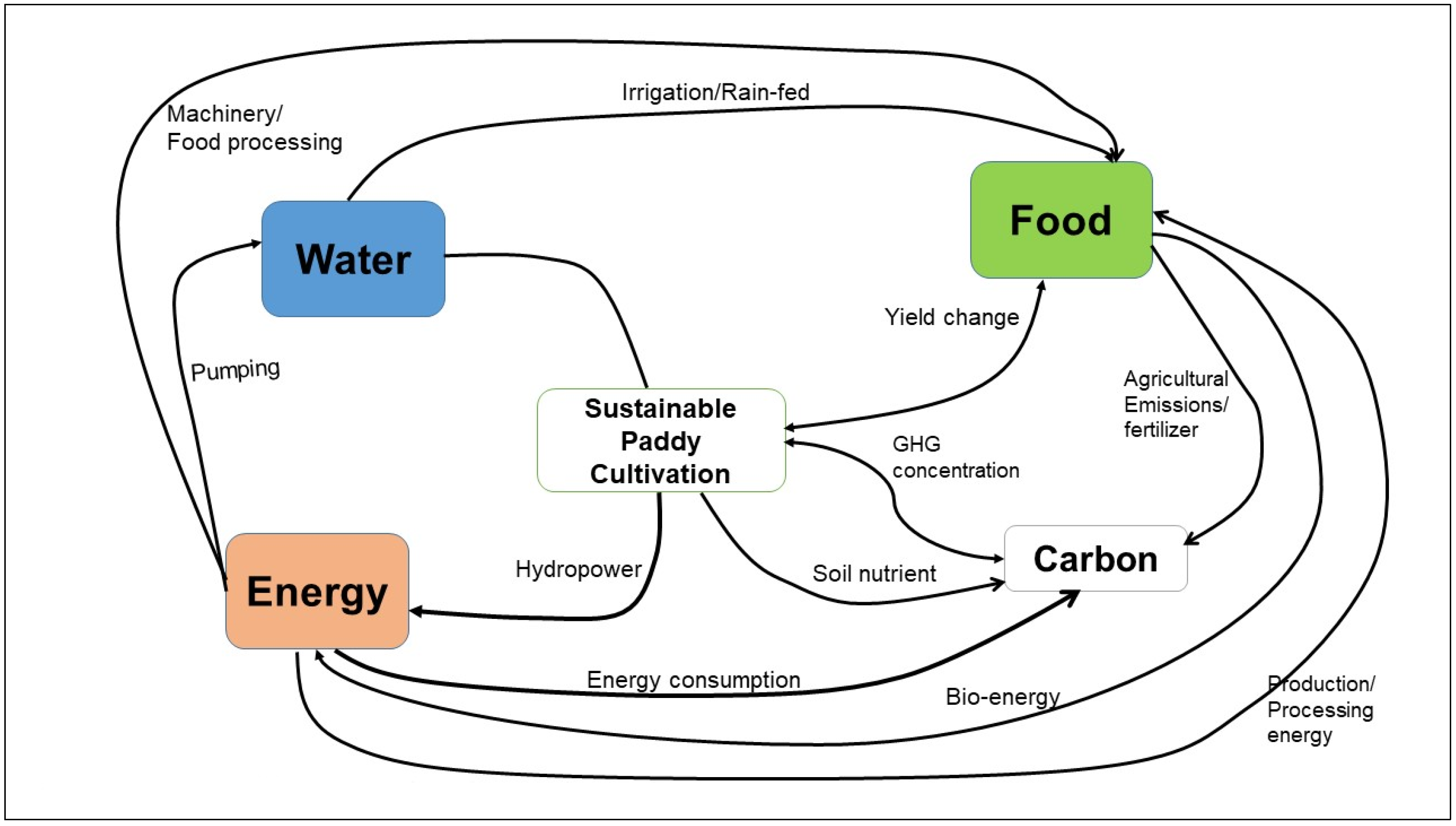

2.8. Carbon Footprint Calculation

3. Results

3.1. Primary WEF Layer Outputs

3.2. Scenario Outputs

3.3. Model Validation

3.3.1. Model Validation: Correlation Analysis Between Hotspot and Scenario Layers

3.3.2. Interpretation by Water Component

3.3.3. Interpretation by Energy Component

3.3.4. Interpretation by Food Component

3.4. Carbon Footprint Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cuthbert, T.; Aidan, S.; Zolo, K.; Mphatso, M.; Tafadzwanashe, M. Water-Energy-Food Nexus Tools in Theory and Practice: A Systematic review. Front. Water 2022, 4, 837316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, R.; Yoo, S.H.; Lee, S.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Hur, S.O.; Yoon, P.R.; Kim, K.S. The Application of a Smart Nexus for Agriculture in Korea for Assessing the Holistic Impacts of Climate Change. Sustainability 2024, 16, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southern African Development Community (SADC). Regional Strategic Action Plan on Integrated Water Resources Development and Management Phase IV, RSAP IV; Southern African Development Community: Gaborone, Botswana, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, P.R.; Lee, S.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Yoo, S.H.; Hur, S.O. Analysis of climate change impact on resource intensity and carbon emissions in protected farming systems using Water-Energy-Food-Carbon Nexus. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 184, 106394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.B. The Water-Energy-Food Nexus; FAO, Italian Agency for Development Cooperation: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/e878a386-7b3c-4413-8c75-8e4587a65a5f/content (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Ringler, C.; Bhaduri, A.; Lawford, R. The nexus across water, energy, land, and food (WELF): Potential for improved resource use efficiency? Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, B.; Lee, S.H.; Kaushik, V.; Blake, J.; Askariyeh, M.H.; Shafiezadeh, H.; Zamaripa, S.; Mohtar, R.H. Towards bridging the water gap in Texas: A Water-Energy-food Nexus approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 647, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Elshorbagy, A.; Pande, S.; Zhuo, L. Trade-offs and synergies in the water-energy-food nexus: The case of Saskatchewan, Canada. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandani, E.J.K.P.; Vidanapathirana, T.T.S. Forecasting Paddy Yield in Sri Lanka Using Back-propagation Learning in Artificial Neural Network Model. J. Univ. Ruhuna 2024, 12, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; Suzuki, H.; Ahmad, W.; Giusti, S.; Ali, A.; Wijekoon, U.; Rathnayake, K.; Sirisena, N.; Mudiyanselage, D.; Senanayake, J.; et al. Efficient Agricultural Water Use and Management in Paddy Fields in Sri Lanka Efficient Agricultural Water Use and Management in Paddy Fields in Sri Lanka, National Outlook; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamawelagedara, W.C.; Wickramasinghe, Y.M.; Dissanayake, C.A.K. Impact of rice processing villages on household income of rural farmers in Anuradhapura District. J. Agric. Sci. Sri Lanka 2011, 6, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Census and Statistics. Agriculture Statistics. 2017. Available online: https://www.statistics.gov.lk/Agriculture/StaticalInformation/PaddyStatistics#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- DailyFT. Innovative Water Management Techniques Revolutionising Paddy Cultivation. 2024. Available online: https://criwmp.lk/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/NSBM-Open-Day.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Burchfield, E.K.; Poterie, A.T.D.L. Determinants of crop diversification in rice-dominated Sri Lankan agricultural systems. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 61, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP Climate. Climate Security Mechanism: Progress Report. 2024. Available online: https://undp-climate.exposure.co/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Young, M.; Vilhauer, R. Sri Lanka Wind Farm Analysis and Site Selection Assistance; NREL/SR-710-34646; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2003. Available online: https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy03osti/34646.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Alahakoon, A.; Thennakoon, T.; Sulaksha, T.; Maneth, D.; Gamage, M.; Weerasinghe, N.; Maharage, D.; Appuhamilage, I.; Hewage, H.; Senarath, P. Overview of solar electricity in Sri Lanka and recycling processes. J. Res. Technol. Eng. 2023, 4, 125–153. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, H.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Li, F.; Pan, K.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, X. A water-energy-food-carbon nexus optimization model for sustainable agricultural development in the Yellow River Basin under uncertainty. Appl. Energy 2022, 326, 120008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change and Land: Summary for Policy Makers. 2019. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2019/06/19R_V0_01_Overview_advance.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- World Bank. The Total GHG Emissions Sri Lanka. 2020. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.ATM.GHGT.KT.CE?locations=LK (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Rathnayake, H.; Mizunoya, T.A. Study on GHG emission assessment in agricultural areas in Sri Lanka: The case of Mahaweli H agricultural region. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 88180–88196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization for the United Nations (FAO). Options for Low Emission Development of Sri Lanka Dairy Sector. 2017. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i7673e/i7673e.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Namany, S.; Al-Ansary, T.; Govindan, R. Sustainable energy, water and food nexus systems: A focused review of decision-making tools for efficient resource management and governance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 610–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.S.; Mahmud, K.; Mitra, B.; Hridoy, A.E.E.; Rahman, S.M.; Shafiullah, M.; Alam, M.S.; Hossain, M.I.; Sujauddin, M. Coupling Nexus and Circular Economy to Decouple Carbon Emissions from Economic Growth. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv, L.S.; Paraschiv, S. Contribution of Renewable Energy (Hydro, Wind, Solar and Biomass) to Decarbonization and Transformation of the Electricity Generation Sector for Sustainable Development. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, R.; Ghimire, B.; Mesbah, A.O.; Sainju, U.M.; Idowu, O.J. Soil Health Response of Cover Crops in the Winter Wheat–Fallow System. Agronomy 2019, 111, 2108–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cai, K.; Qi, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z. Experimental investigation on N2O emission characteristics of ammonia-diesel dual-fuel engines. Int. J. Engine Res. 2025, 26, 1088–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijamans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization for the United Nations (FAO). Global Soil Organic Carbon Map. 2017. Available online: https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/data-hub/soil-maps-and-databases/global-soil-organic-carbon-map-gsocmap/en/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Mapa, R.B.; Dassanayake, A.R.; Eilers, R.G.; Goh, T.B. Classification and Mapping of Soils of Sri Lanka for Sustainable Land Management. In Proceedings of the 18th World Congress of Soil Science, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 9–15 July 2006; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303309091_Classification_and_Mapping_of_Soils_of_Sri_Lanka_for_Sustainable_Land_Management (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Hyun, B.K.; Mapa, R.B.; Sonn, Y.K.; Cho, H.J.; Shin, K.; Choi, J.; Jang, B.C. The Study on Soil Classification in Sri Lanka. Korean Soc. Soil Sci. Fertil. 2015, 48, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring Vegetation Systems in the Great Plains with ERTS (Earth Resources Technology Satellite). In Proceedings of the 3rd Earth Resources Technology Satellite Symposium, Greenbelt, Makati, Philippines, 10–14 December 1973; Volume SP-351, pp. 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- McFeeters, S.K. The use of the normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 17, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, M.; Ghorbanian, A.; Ahmadi, S.A.; Kakooei, M.; Moghimi, A.; Mirmazloumi, S.M. Google Earth Engine Cloud Computing Platform for Remote Sensing Big Data Applications: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 5326–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathivha, F.; Mbatha, N. Comparison of Long-Term changes in Non-Linear Aggregated Drought Index calibrated by MERRA–2 and NDII soil moisture proxies. Water 2021, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Qu, Y. The Retrieval of Ground NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) Data Consistent with Remote-Sensing Observations. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, L.; Chen, Y.; Shi, T.; Luo, M.; Ju, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S. Prediction of Soil Organic Carbon based on Landsat 8 Monthly NDVI Data for the Jianghan Plain in Hubei Province, China. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos, T.; Benos, L.; Busato, P.; Kyriakarakos, G.; Kateris, D.; Aidonis, D.; Bochtis, D. Soil Organic Carbon Assessment for Carbon Farming: A Review. Agriculture 2025, 15, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, V.Q.; Vu, P.T.; Giao, N.T. Soil properties characterization and constraints for rice cultivation in Vinh Long Province, Vietnam. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2023, 12, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hanbali, A.; Shibuta, K.; Alsaaideh, B.; Tawara, Y. Analysis of the land suitability for paddy fields in Tanzania using a GIS-based analytical hierarchy process. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2021, 25, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aginthini, A.; Udayakumara, E.P.N.; Arasakesary, S.J. Land Evaluation and Crop Suitability Analysis—A case study on Karachchi Divisional Secretariat, Kilinochchi District, Sri Lanka. Vavuniya J. Sci. 2023, 2, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B. An assessment on land suitability for rice cultivation using analytical hierarchy process in the Sivasagar district of Assam, India. Int. Res. J. Multidiscip. Scope 2024, 5, 942–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavipathirana, C.G.; Sandamali, J.; Sandamali, K.; Hasara, K.S.L.S. Assessing the Feasibility for Paddy Cultivation Sites Through Multi Criteria Evaluation and GIS Approach: A Case Study of Ampara District, Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Remote Sensing, Sri Jayewardenepura Kotte, Sri Lanka, 17–21 November 2024; Available online: https://acrs-aars.org/proceeding/ACRS2024/AB0047.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Mandal, T.; Saha, S. Land Suitability Analysis for Paddy Cultivation through Geospatial Technique: A Case Study of Malda District, West Bengal. University of North Bengal. 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340684679_Land_Suitability_Analysis_for_Paddy_Cultivation_through_Geospatial_TechniqueA_Case_Study_of_Malda_District_West_Bengal/link/5e99525592851c2f52aa123f/download?_tp=eyJjb250ZXh0Ijp7ImZpcnN0UGFnZSI6InB1YmxpY2F0aW9uIiwicGFnZSI6InB1YmxpY2F0aW9uIn19 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Palihakkara, J.; Attanayake, C.P.; Burkitt, L. Phosphorus Release and Transformations in Contrasting Tropical Paddy Soils Under Fertiliser Application. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 25, 4570–4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, E.M.D.; De Silva, C.S.; Ratnayake, R.R. Estimation and Mapping Soil Organic Carbon in Paddy Growing Soils of Monaragala District, Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of the Open University Research Sessions, Virtual, 16–17 September 2021; Available online: https://ours.ou.ac.lk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/ID-25_ESTIMATION-AND-MAPPING-SOIL-ORGANIC-CARBON-IN-PADDY-GROWING-SOILS-OF-MONARAGALA-DISTRICT-SRI-LANKA.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Munda, G. Social multi-criteria evaluation: Methodological foundations and operational consequences. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 158, 662–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.Q.; van Duynhoven, A.; Dragićević, S. Machine Learning for Criteria Weighting in GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Evaluation: A Case Study of Urban Suitability Analysis. Land 2024, 13, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, S.T.; Li, H.W.; Zhang, B. Research on Geographical Environment Unit Division Based on the Method of Natural Breaks (Jenks). Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2013, XL-4/W3, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Zhang, Z.; Hong, Z.; Liu, L.; Liu, L.; Ashraf, T.; Liu, Y. Spatial suitability evaluation based on multisource data and random forest algorithm: A case study of Yulin, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1338931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, M.M.; Abebe, A.K. GIS and fuzzy logic integration in land suitability assessment for surface irrigation: The case of Guder watershed, Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Appl. Water Sci. 2022, 12, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, S. Identifying Crime Clusters: The Spatial Principles. Middle States Geogr. 1995, 28, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, X.; Dong, Y.; Tan, W.; Su, Y.; Huang, P. A Parameter-Free Pixel Correlation-Based Attention Module for Remote Sensing Object Detection. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H.; Yagi, K.; Yan, X. Direct N2O emissions from rice paddy fields: Summary of available data. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2005, 19, GB1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Change Secretariat (CCS). A Guide for Carbon Footprint Assessment. Climate Change Secretariat Ministry of Mahaweli Development and Environment. 2016. Available online: https://share.google/Nz57MqXEkzjeOifVC (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Department of Census and Statistics. Agriculture Statistics. 2025. Available online: https://www.statistics.gov.lk/Agriculture/StaticalInformation/PaddyStatistics/ImperialUnits/IncludingMahaweli/2024-2025Maha (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Singla, M.K.; Gupta, J.; Gupta, A.; Safaraliev, M. Empowering Rural Farming: Agrovoltaic Applications for Sustainable Agriculture. Energy Sci. Eng. 2024, 13, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Derived Data | Source | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landsat 8/9 satellite data | NDVI, NDWI, SMI | USGS Explorer, Reston, VA, USA https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov (accessed on 17 April 2025) | 30 m | 2020–2023 Acquisition was aligned with the phonological stages of rice to capture peak vegetation periods, from July to August for the Yala season and from January to February for the Maha season |

| Climate data | Rainfall, solar radiation, wind speed | WorldClim 2.1 dataset, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA https://www.worldclim.org (accessed on 28 April 2025) | 1 km2 | Monthly average data from 1970 to 2000 [28] (Fick and Hijamans, 2017) |

| Soil organic carbon | SOC stock data (0–30 cm depth) | Global Soil Organic Carbon Map (GSOCmap v2.0(2017) http://54.229.242.119/GSOCmap/ [29] (FAO (2017) (accessed on 29 April 2025) | 1 km2 | - |

| Soil type | Soil types of NCP | Soils of Sri Lanka | 1:50,000 | 2005 update [30,31] (Mapa et al., 2006; Hyun et al., 2015) |

| Electricity availability | Proximity to national grid | Ceylon Electricity Board Statistical Digest 2021 | 1:2,000,000 | 2021 |

| Land use | Land use classification | Land Use Policy Planning Department (LUPPD), Sri Lanka | 1:50,000 | 2018 |

| Parameter Value | Classification Method | Very High 5 | High 4 | Moderate 3 | Low 2 | Very Low 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDVI | Jenks Natural Breaks | 0.3497–0.5355 | 0.2983–0.3497 | 0.2372–0.2983 | 0.1199–0.2372 | (−0.0902)–0.1199 |

| SOC (Mg/ha) | Jenks Natural Breaks | 63–81 | 58–63 | 53–58 | 0–53 | 0 |

| Soil Type | Literature-based | Alfisols | Ultisols | Entisols | Lithic subgroups | Erosional remnants, Rock Knob Plains |

| Land Use | Literature-based | Agricultural lands | Home gardens, scrubland | Forests | Water bodies | Built-up |

| Parameter Value | Very High 5 | High 4 | Moderate 3 | Low 2 | Very Low 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rainfall (mm) | 140–168 | 129–140 | 118–129 | 105–118 | 89–105 |

| SMI | 0.1587– 0.3172 | 0.1151– 0.1587 | 0.0691– 0.1152 | 0.02274–0.069194 | −0.270616–0.023274 |

| NDWI | −0.1070– 0.0943 | −0.2289– −0.1070 | −0.2885– −0.2289 | −0.330844–−0.28857 | −0.542214–0.330844 |

| Parameter Value | Very High 5 | High 4 | Moderate 3 | Low 2 | Very Low 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximity to national electricity grid (m) | 0–0.06 | 0.06–0.12 | 0.12–0.18 | 0.18–0.23 | 0.23–0.30 |

| Solar radiation (kJ/m2/day) | 19,748–20,093 | 20,093–20,289 | 20,289–20,456 | 20,456–20,621 | 20,621–20,840 |

| Wind speed (ms−1) | 1.58–1.82 | 1.82–1.97 | 1.97–2.11 | 2.11–2.28 | 2.28–2.64 |

| Model Representation |

|---|

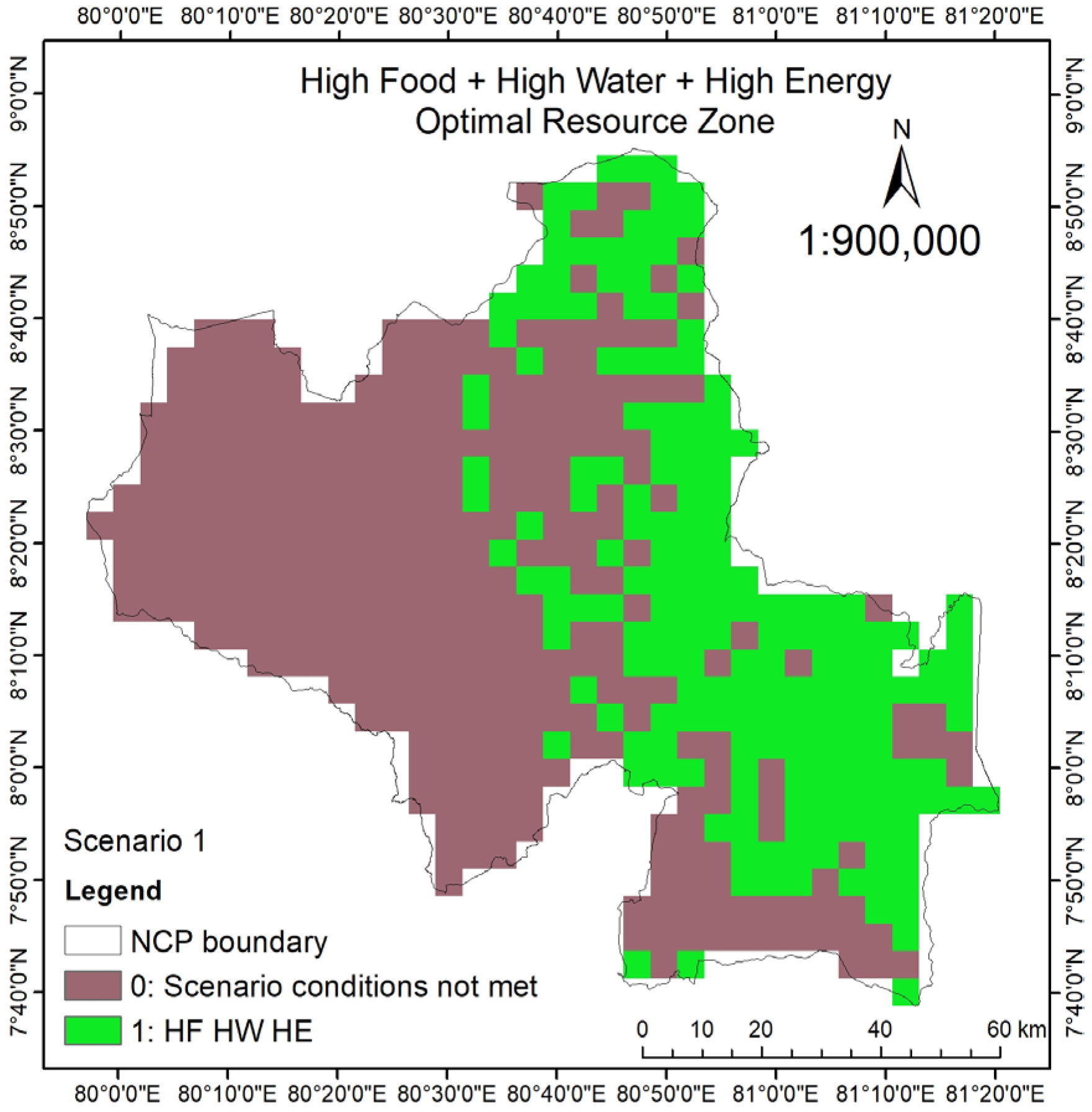

| Scenario 1: WEF interaction in the Study Area |

| High Food + High Water + High Energy: Optimal Resource Zone |

| Scenario_HFHWHE = Con (((“Food_Class” ≥ 3) & (“Water_Class” ≥ 3) & (“Energy_Class” ≥ 3)), 1, 0) |

| “Food_Class” ≥ 3 ➔ selects high-food-productivity areas |

| “Water_Class” ≥ 3 ➔ selects high-water-availability areas |

| “Energy_Class” ≥ 3 ➔ selects high-energy-potential areas |

| 1 ➔ where all three conditions are true |

| 0 ➔ elsewhere |

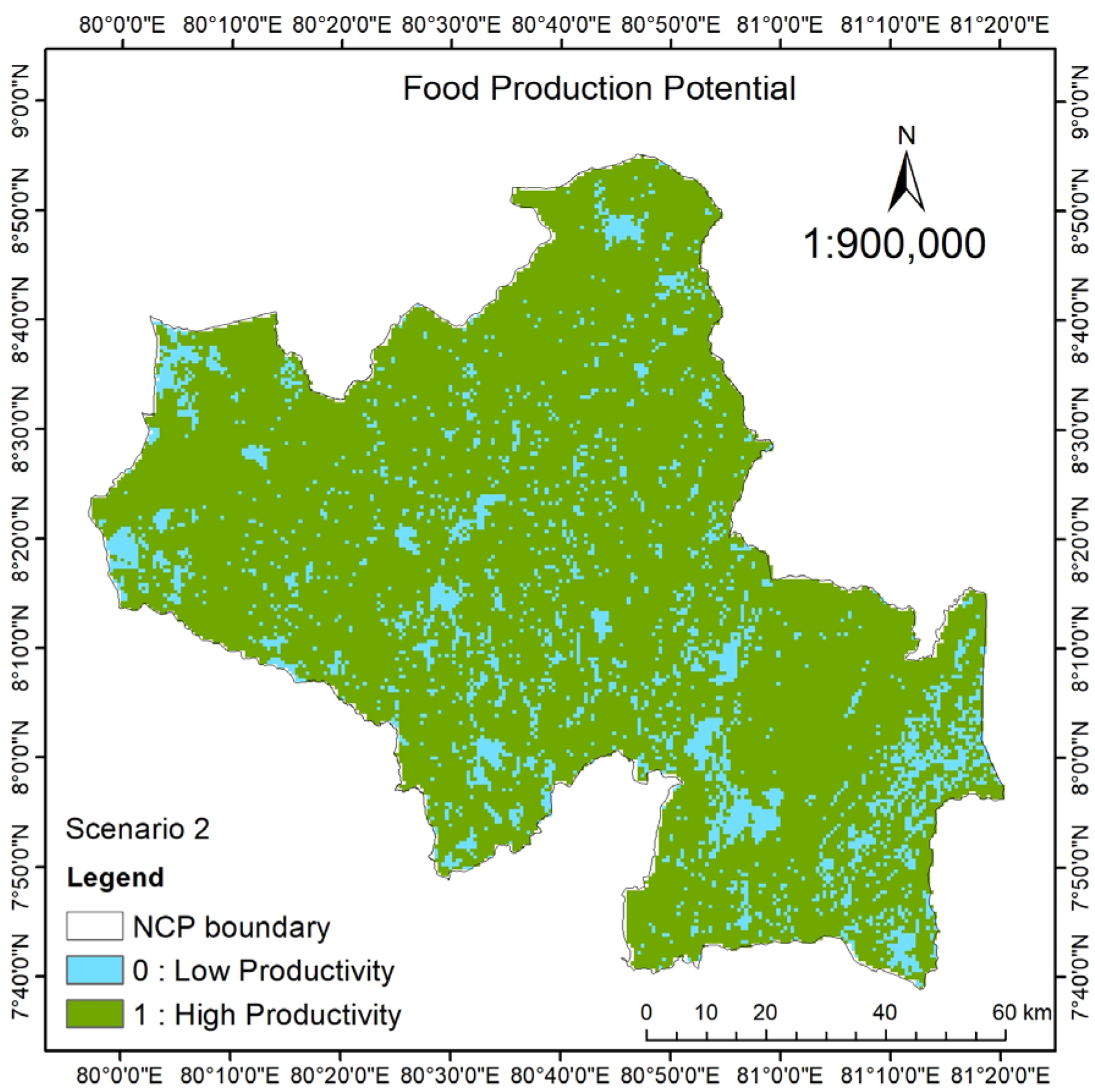

| Scenario 2: High Production Potential: High Food |

| Scenario_HF = Con (“Food_Class” ≥ 3, 1, 0) |

| “Food_Class” ≥ 3 ➔ high food availability |

| 1 ➔ where conditions are true |

| 0 ➔ elsewhere |

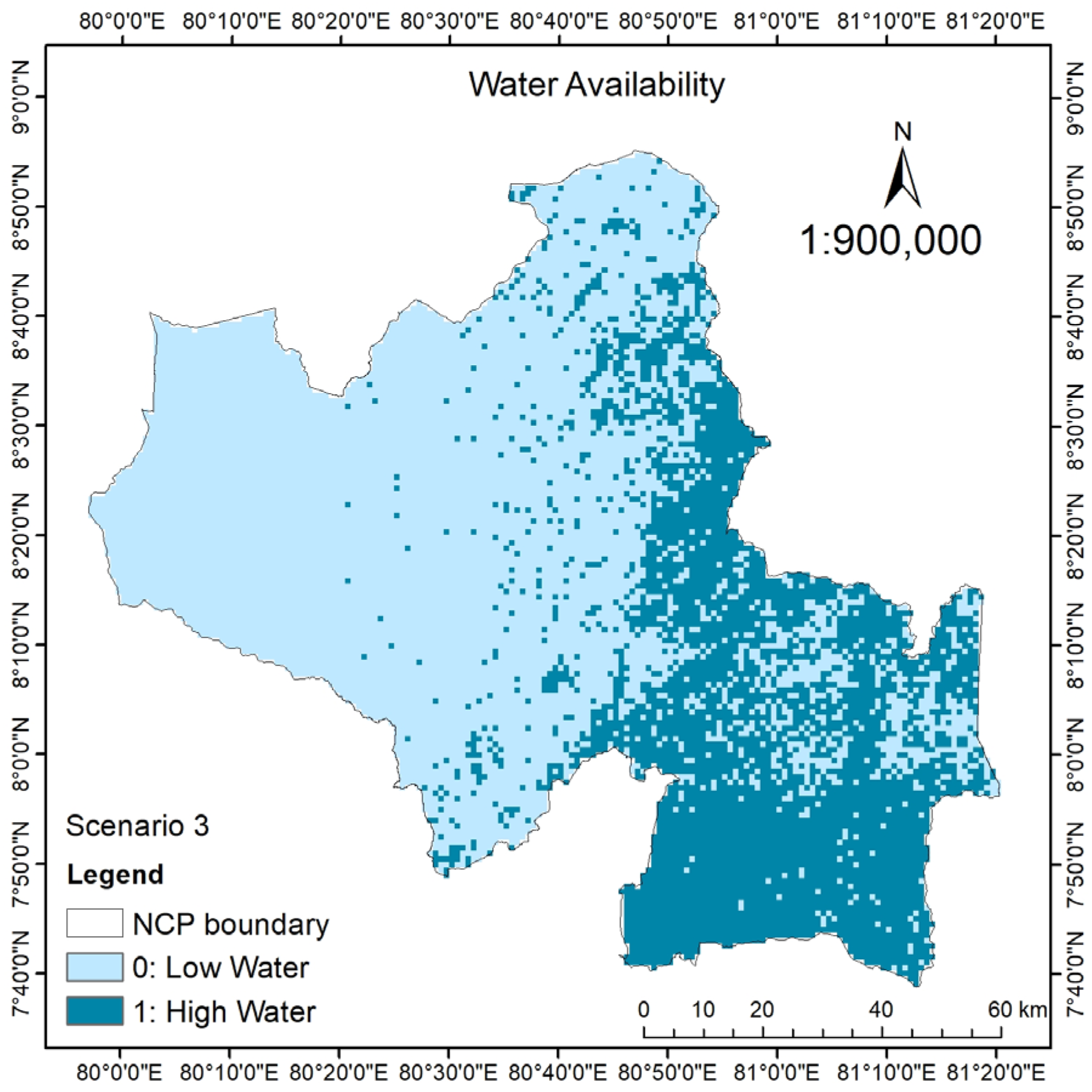

| Scenario 3: High Water |

| Scenario_HW = Con (“Water_Class” ≥ 3, 1, 0) |

| “Water_Class” ≥ 3 ➔ high water availability |

| 1 ➔ where conditions are true |

| 0 ➔ elsewhere |

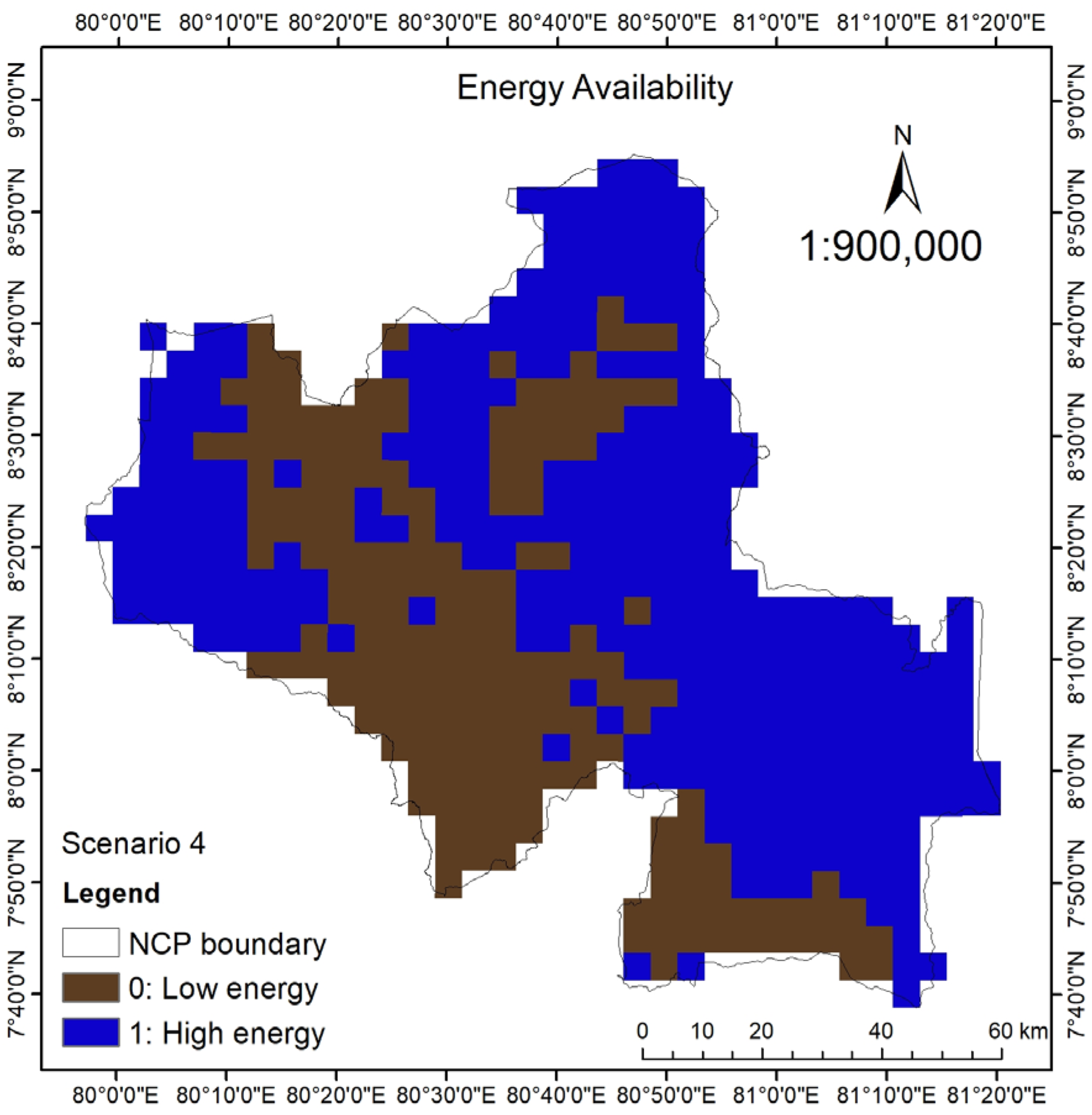

| Scenario 4: High Energy |

| Scenario_HE = Con (“Energy_Class” ≥ 3, 1, 0) |

| “Energy_Class” ≥ 3 ➔ high energy availability |

| 1 ➔ where conditions are true |

| 0 ➔ elsewhere |

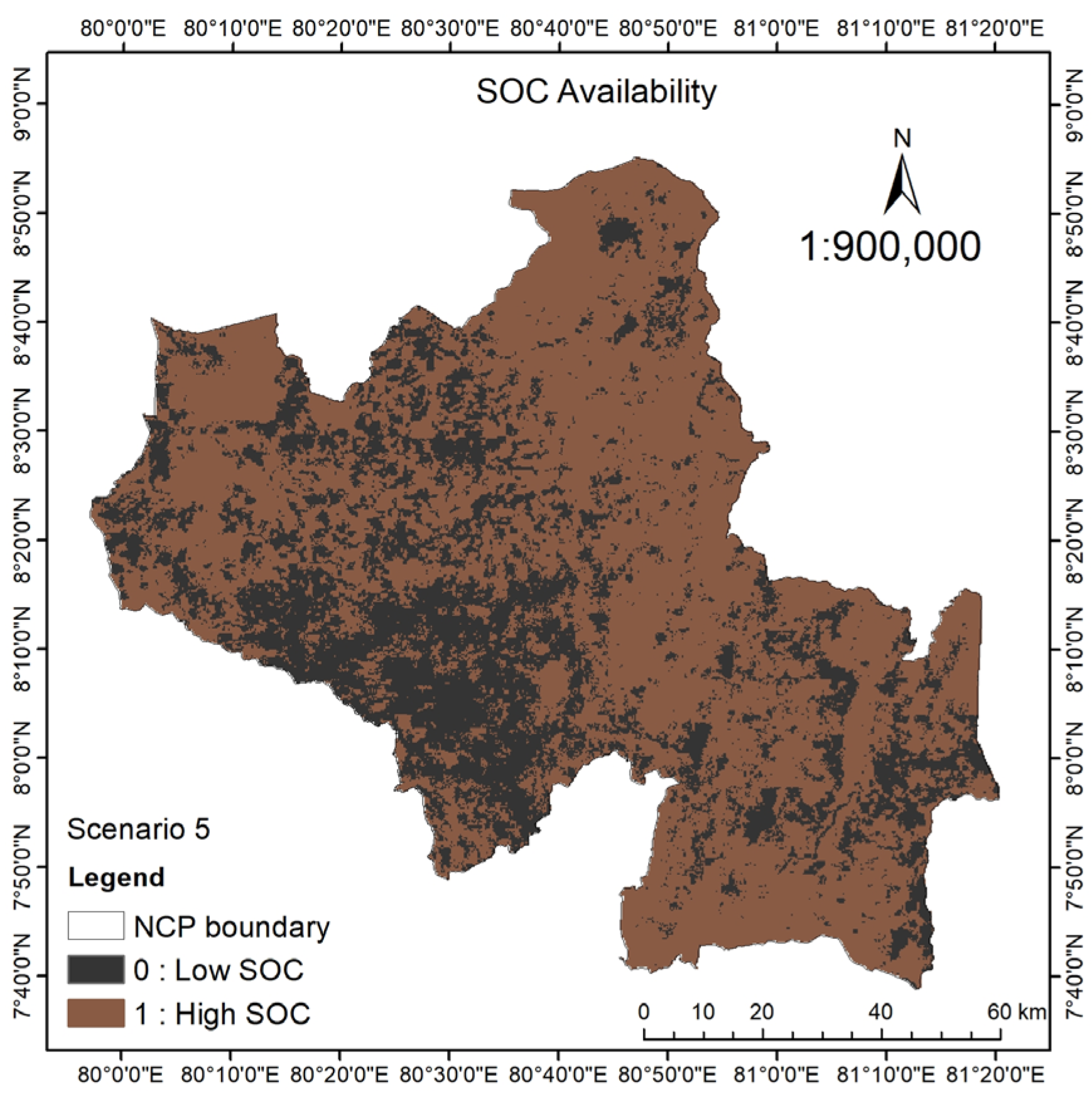

| Scenario 5: High SOC |

| Scenario_HC = Con (“SOC_Class” ≥ 3, 1, 0) |

| “SOC_Class” ≥ 3 ➔ high SOC availability |

| 1 ➔ where conditions are true |

| 0 ➔ elsewhere |

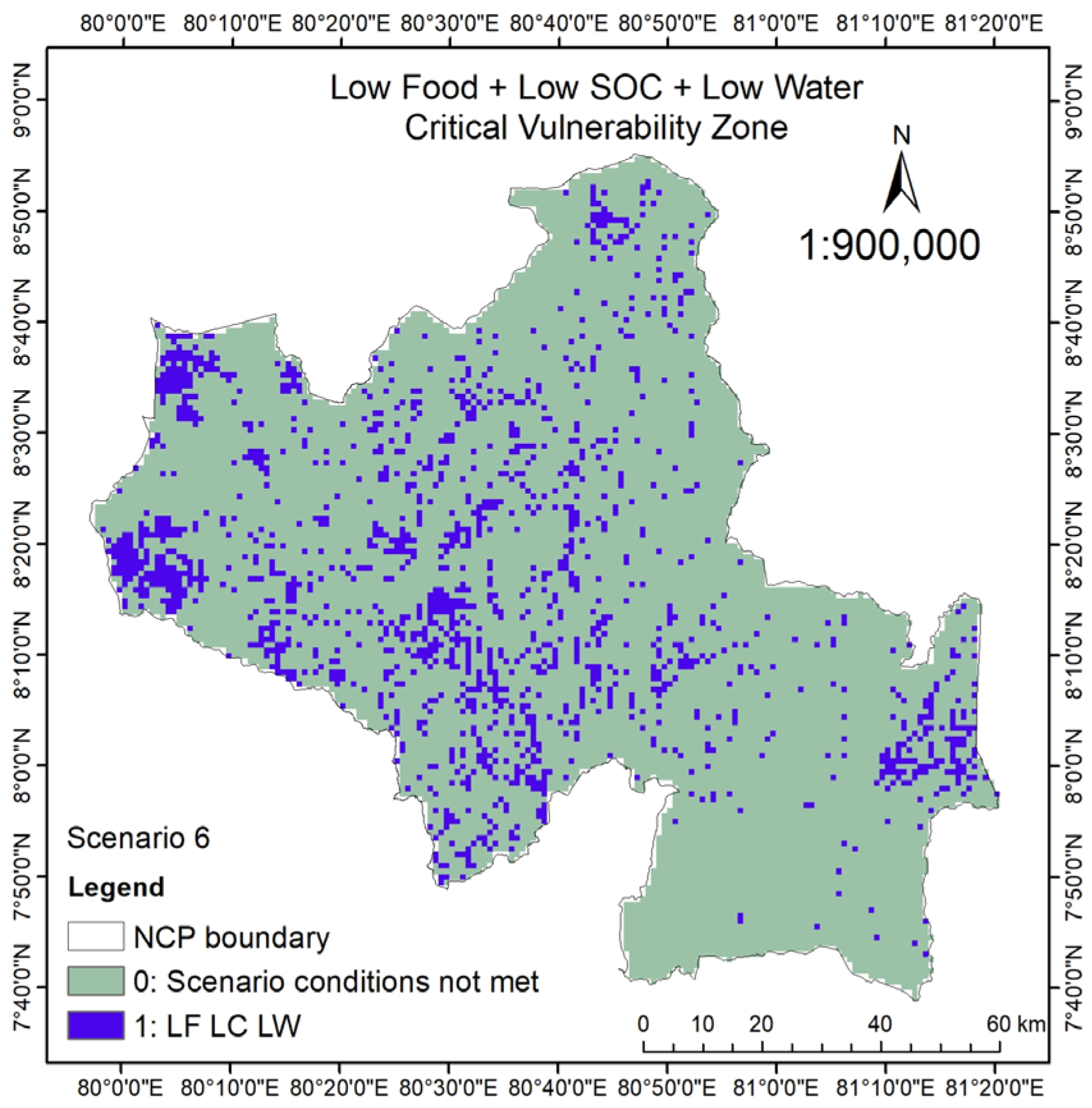

| Scenario 6: Low Food + Low SOC + Low Water (Critical Vulnerability Zone) |

| Scenario_LFLCLW = Con ((“Food_Class” ≤ 3) & (“SOC_Class” ≤ 3) & (“Water_Class” ≤ 3), 1, 0) |

| “Food_Class” ≤ 3 ➔ low food productivity |

| “SOC_Class” ≤ 3 ➔ low SOC availability |

| “Water_Class” ≤ 3 ➔ low water availability |

| 1 ➔ where all three conditions are true |

| 0 ➔ elsewhere |

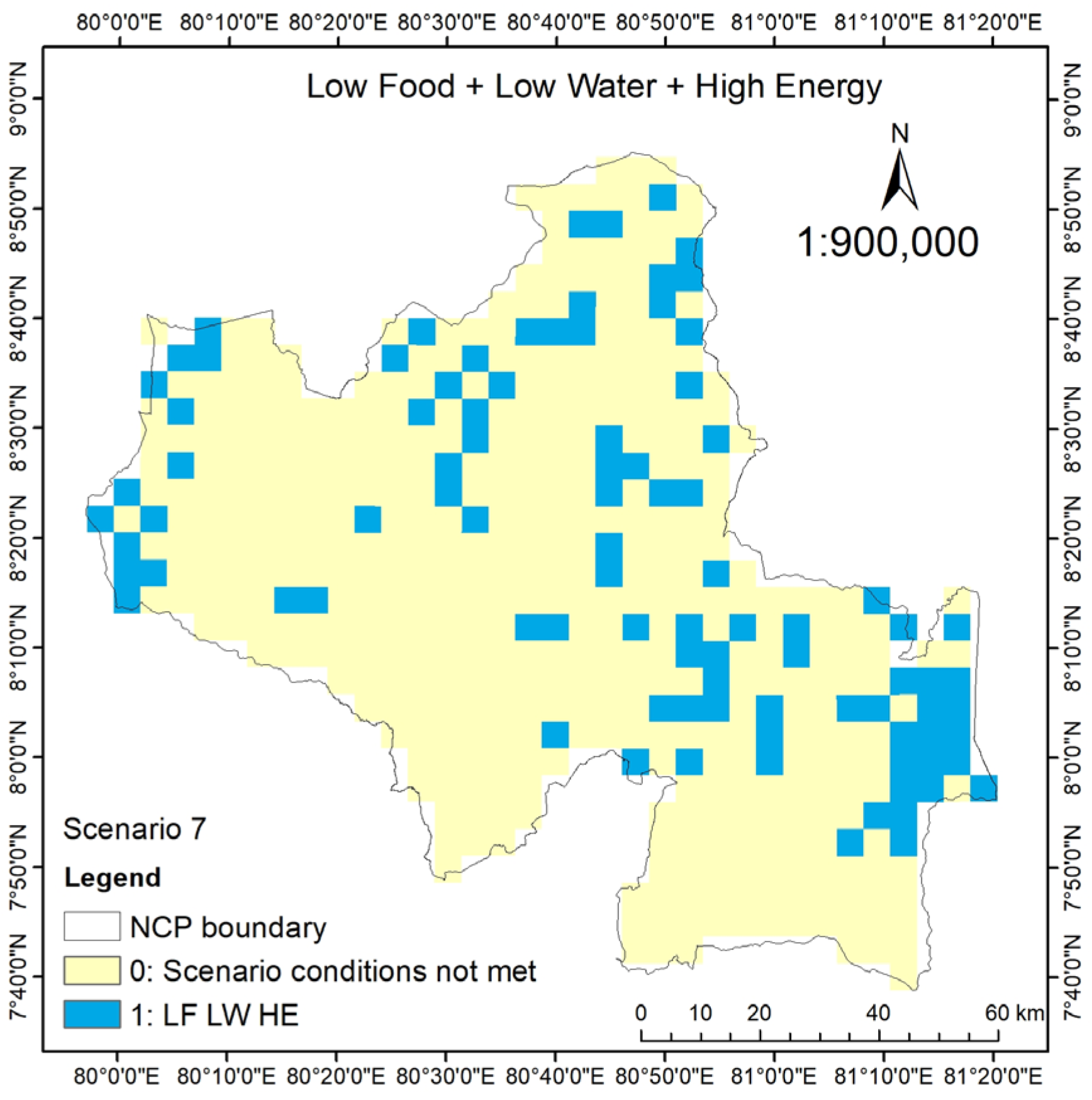

| Scenario 7: High energy + Low Food + Low Water (Energy-driven Zone) |

| Scenario_HELFLW = Con (((“Energy_Class” ≥ 3) & (“Food_Class” ≤ 3) & (“Water_Class” ≤ 3)), 1, 0) |

| “Energy_Class” ≥ 3 ➔ high energy availability |

| “Food_Class” ≤ 3 ➔ low food productivity |

| “Water_Class” ≤ 3 ➔ low water availability |

| 1 ➔ where all three conditions are true |

| 0 ➔ elsewhere |

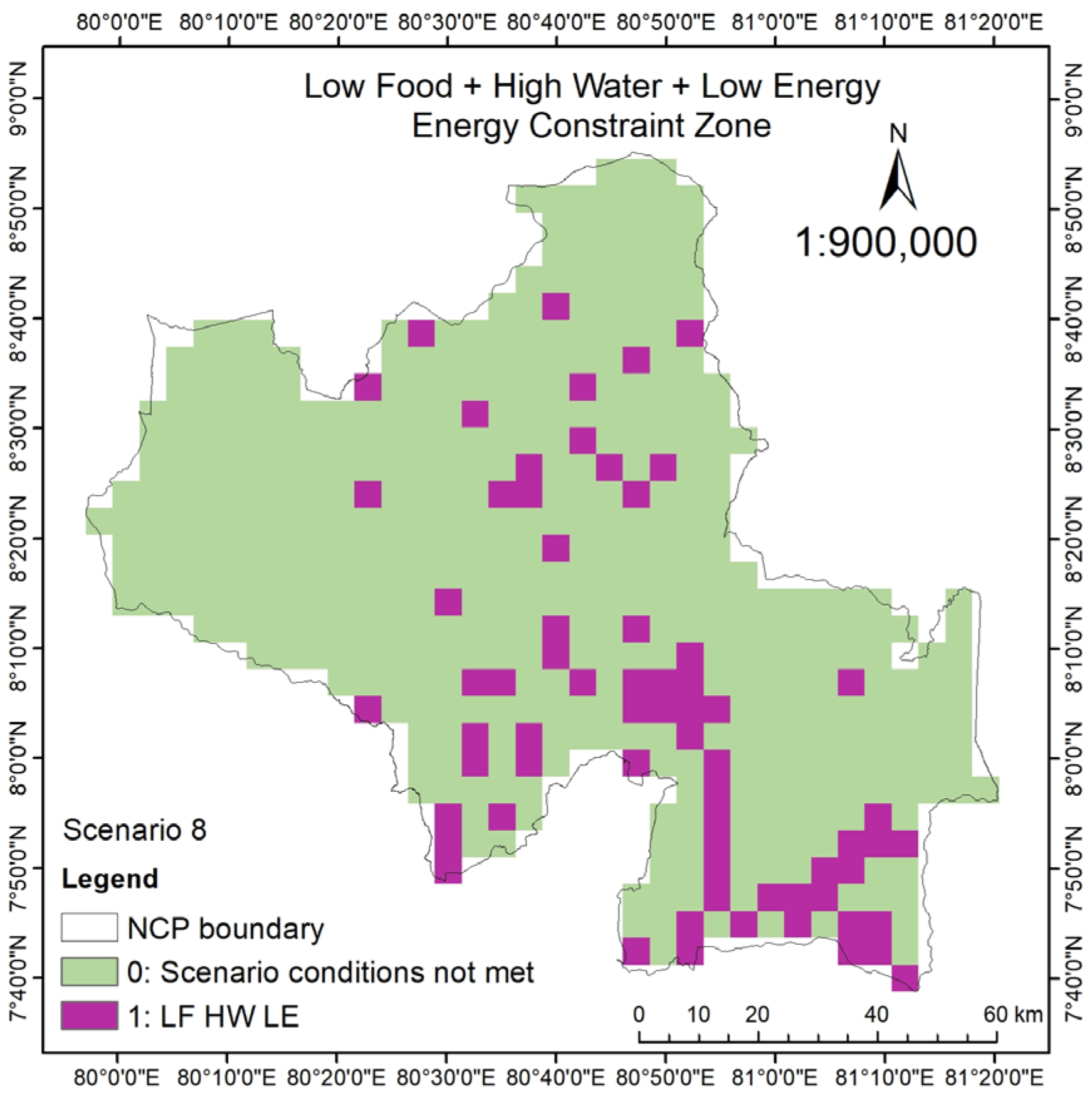

| Scenario 8: Low Food + High Water + Low Energy (Energy-Constraint Zone) |

| Scenario_LFHWLE = Con (((“Food_Class” ≤ 3) & (“Water_Class” ≥ 3) & (“Energy_Class” ≤ 3)), 1, 0) |

| “Food_Class” ≤ 3 ➔ low food productivity |

| “Water_Class” ≥ 3 ➔ high water availability |

| “Energy_Class” ≤ 3 ➔ low energy availability |

| 1 ➔ where all three conditions are true |

| 0 ➔ elsewhere |

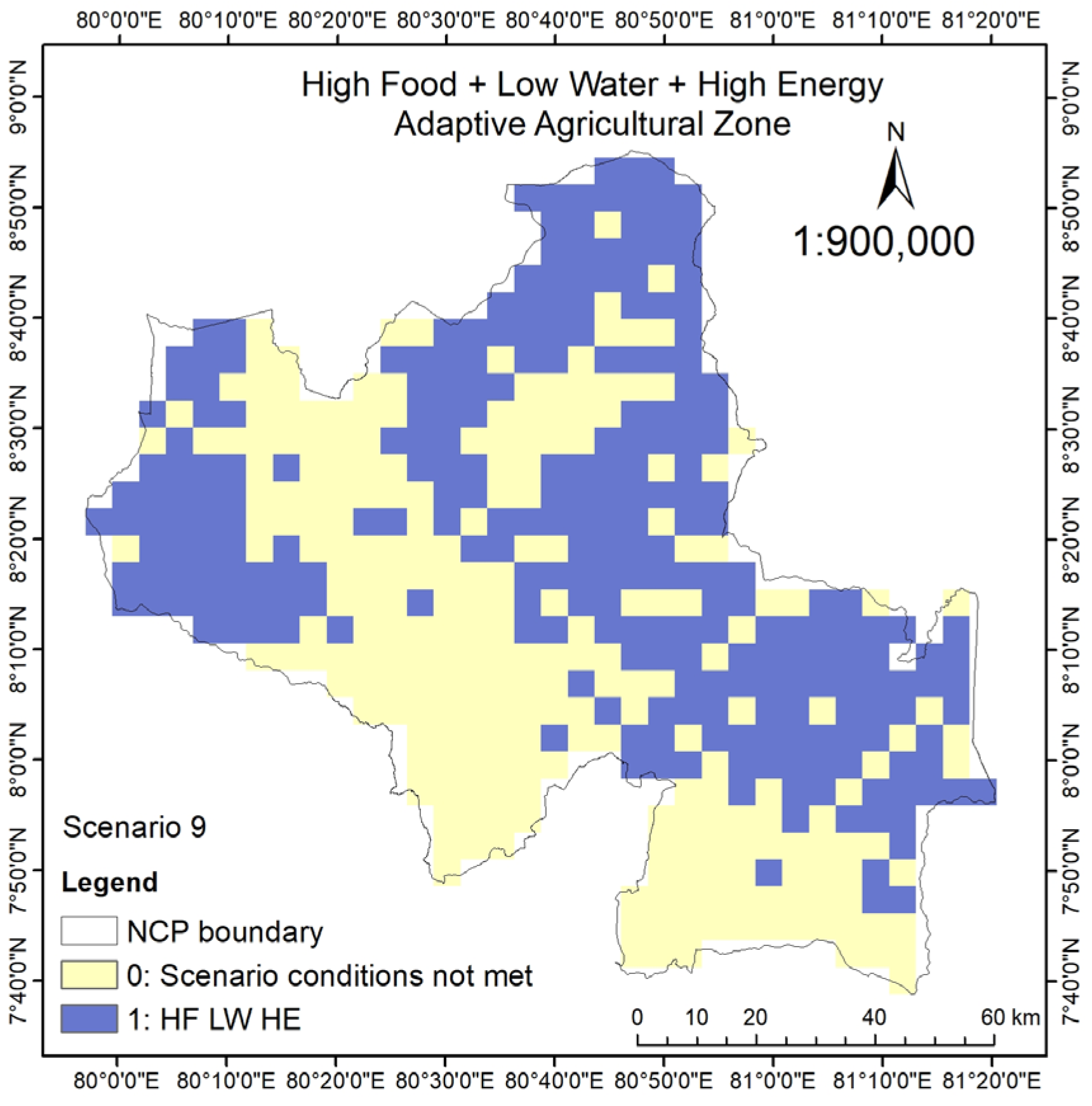

| Scenario 9: High Food + Low Water + High Energy (Adaptive Agricultural Zone) |

| Scenario_HFLWHE = Con (((“Food_Class” ≥ 3) & (“Water_Class” ≤ 3) & (“Energy_Class” ≥ 3)), 1, 0) |

| “Food_Class” ≥ 3 ➔ high food productivity |

| “Water_Class” ≤ 3 ➔ low water availability |

| “Energy_Class” ≥ 3 ➔ high energy availability |

| 1 ➔ where all three conditions are true |

| 0 ➔ elsewhere |

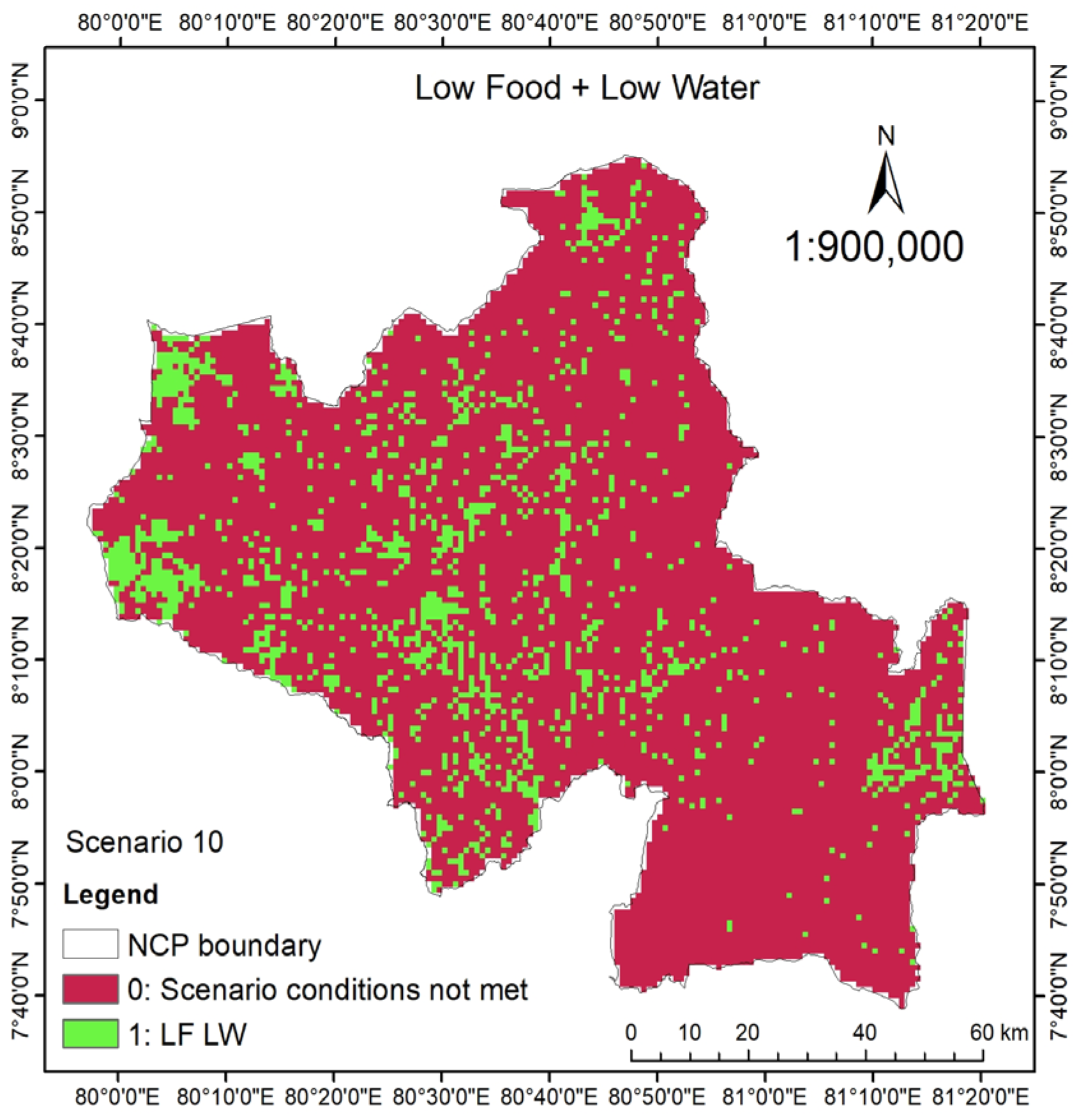

| Scenario 10: High Food + Low Water |

| Scenario_HFLW = Con ((“Food_Class” ≥ 3) & (“Water_Class” ≤ 3), 1, 0) |

| “Food_Class” ≥ 3 ➔ high food productivity |

| “Water_Class” ≤ 3 ➔ low water availability |

| 1 ➔ where all two conditions are true |

| 0 ➔ elsewhere |

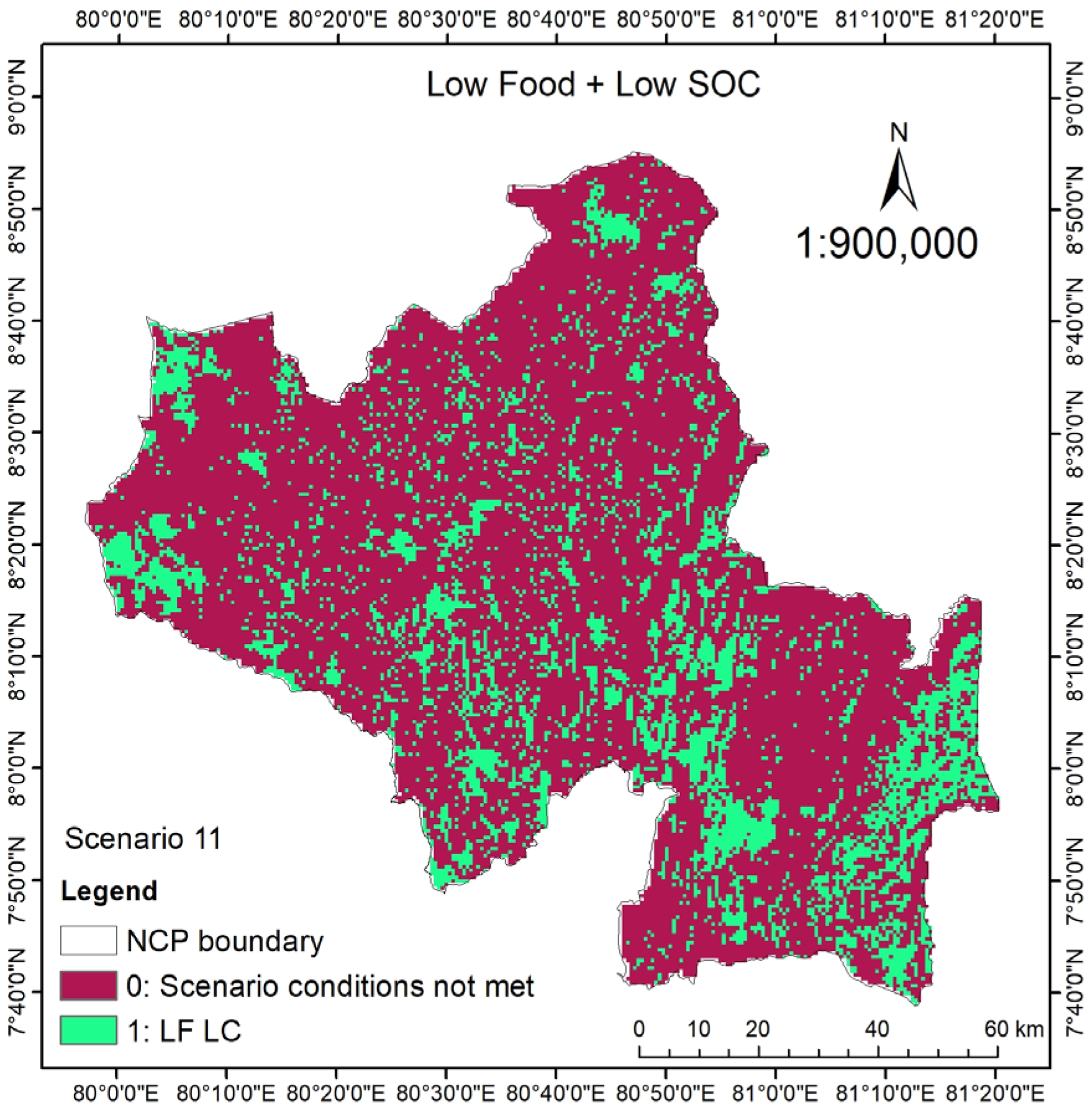

| Scenario 11: Low Food + Low SOC |

| Scenario_LFLC = Con ((“Food_Class” ≤ 3) & (“SOC_Class” ≤ 3), 1, 0) |

| “Food_Class” ≤ 3 ➔ low food availability |

| “SOC_Class” ≤ 3 ➔ low SOC availability |

| 1 ➔ where all two conditions are true |

| 0 ➔ elsewhere |

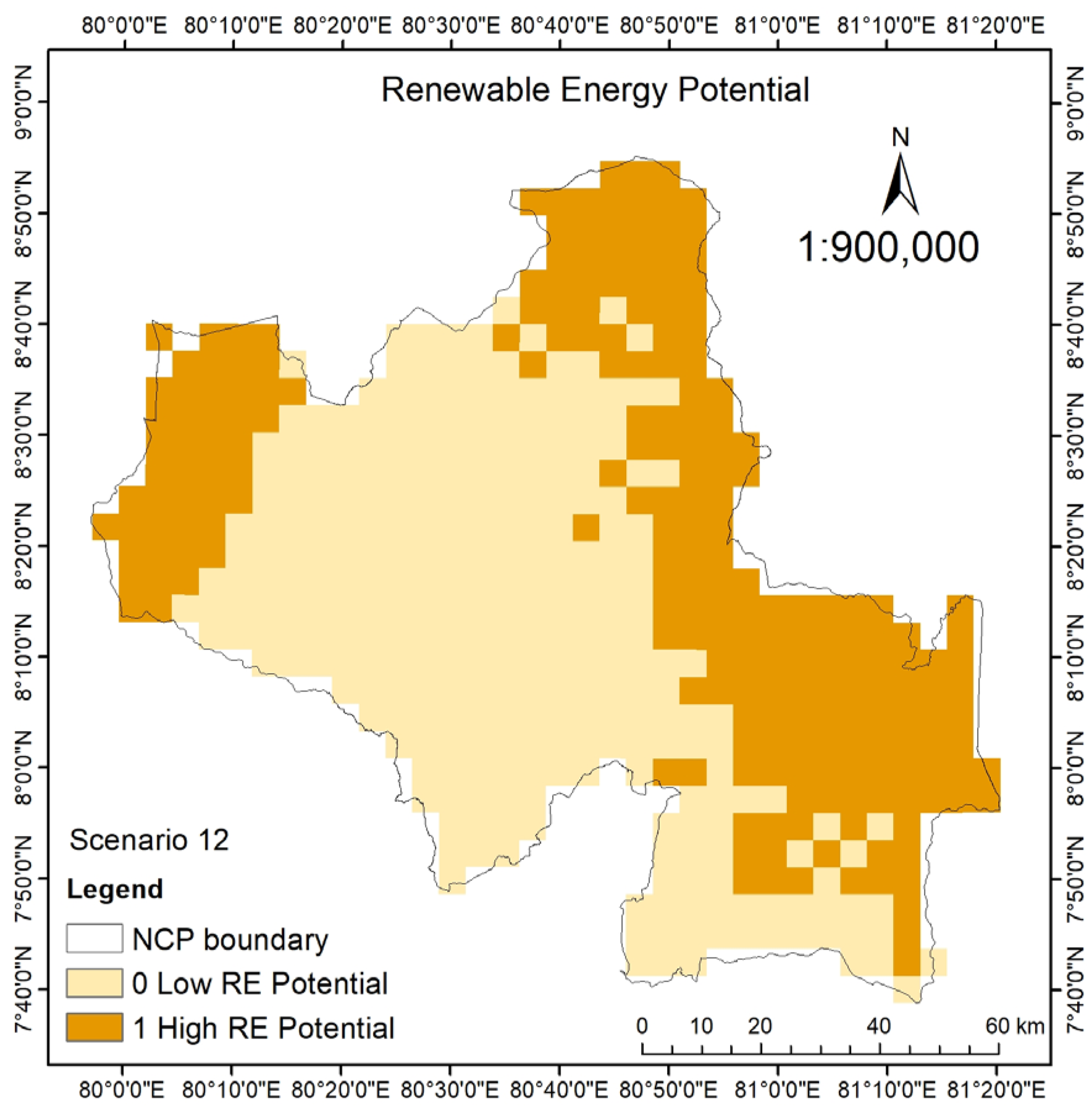

| Scenario 12: High Solar + High Wind (Renewable Energy Potential) |

| Scenario_HSoLWi = Con ((“Solar_Class” ≥ 3) & (“Wind_Class” ≥ 3), 1, 0) |

| “Solar_Class” ≥ 3 ➔ high solar energy |

| “Wind_Class” ≥ 3 ➔ high wind energy |

| 1 ➔ where all two conditions are true |

| 0 ➔ elsewhere |

| Statistic | Layer 1 (Water Hotspot) | Layer 2 (Water Availability Scenario) |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum (MIN) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Maximum (MAX) | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Mean | 0.4523 | 0.5398 |

| Standard Deviation (SD) | 0.4977 | 0.4964 |

| Covariance Matrix | ||

| Layer | 1 | 2 |

| 1 | 0.12156 | 0.08979 |

| 2 | 0.08979 | 0.12156 |

| Correlation Matrix | ||

| Layer | 1 | 2 |

| 1 | 1.00000 | 0.73717 |

| 2 | 0.73717 | 1.00000 |

| Statistic | Layer 1 (Energy Hotspot) | Layer 2 (Energy Availability Scenario) |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum (MIN) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Maximum (MAX) | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Mean | 0.6818 | 0.4316 |

| Standard Deviation (SD) | 0.4658 | 0.4958 |

| Covariance Matrix | ||

| Layer | 1 | 2 |

| 1 | 0.10472 | 0.06498 |

| 2 | 0.06498 | 0.10472 |

| Correlation Matrix | ||

| Layer | 1 | 2 |

| 1 | 1.00000 | 0.58161 |

| 2 | 0.58161 | 1.00000 |

| Statistic | Layer 1 (Food Hotspot) | Layer 2 (Food Availability Scenario) |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum (MIN) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Maximum (MAX) | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Mean | 0.5783 | 0.9398 |

| Standard Deviation (SD) | 0.4938 | 0.2378 |

| Covariance Matrix | ||

| Layer | 1 | 2 |

| 1 | 0.11960 | 0.01573 |

| 2 | 0.01573 | 0.02775 |

| Correlation Matrix | ||

| Layer | 1 | 2 |

| 1 | 1.00000 | 0.27304 |

| 2 | 0.27304 | 1.00000 |

| Pair (Layers) | r (Pearson) | n (Valid Pixels) | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Hotspot vs. Water Scenario | 0.73717 | 10,542 | <0.001 | Indicates a strong positive correlation between hotspot zones and scenarios |

| Energy Hotspot vs. Energy Scenario | 0.58161 | 9863 | <0.001 | Indicates a moderate positive correlation between hotspot zones and scenarios |

| Food Hotspot vs. Food Scenario | 0.27304 | 12,000 | <0.001 | Indicates a mild positive correlation between hotspot zones and scenarios |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Iddawela, A.U.; Son, J.-W.; Sonn, Y.-K.; Hur, S.-O. Geospatial Assessment and Modeling of Water–Energy–Food Nexus Optimization for Sustainable Paddy Cultivation in the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka: A Case Study in the North Central Province. Water 2026, 18, 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020152

Iddawela AU, Son J-W, Sonn Y-K, Hur S-O. Geospatial Assessment and Modeling of Water–Energy–Food Nexus Optimization for Sustainable Paddy Cultivation in the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka: A Case Study in the North Central Province. Water. 2026; 18(2):152. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020152

Chicago/Turabian StyleIddawela, Awanthi Udeshika, Jeong-Woo Son, Yeon-Kyu Sonn, and Seung-Oh Hur. 2026. "Geospatial Assessment and Modeling of Water–Energy–Food Nexus Optimization for Sustainable Paddy Cultivation in the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka: A Case Study in the North Central Province" Water 18, no. 2: 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020152

APA StyleIddawela, A. U., Son, J.-W., Sonn, Y.-K., & Hur, S.-O. (2026). Geospatial Assessment and Modeling of Water–Energy–Food Nexus Optimization for Sustainable Paddy Cultivation in the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka: A Case Study in the North Central Province. Water, 18(2), 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020152