Massive Stranding of Macroramphosus gracilis (Lowe, 1839) in the Strait of Messina (Central Mediterranean Sea): Somatic Features of Different Post-Larval Development Stages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

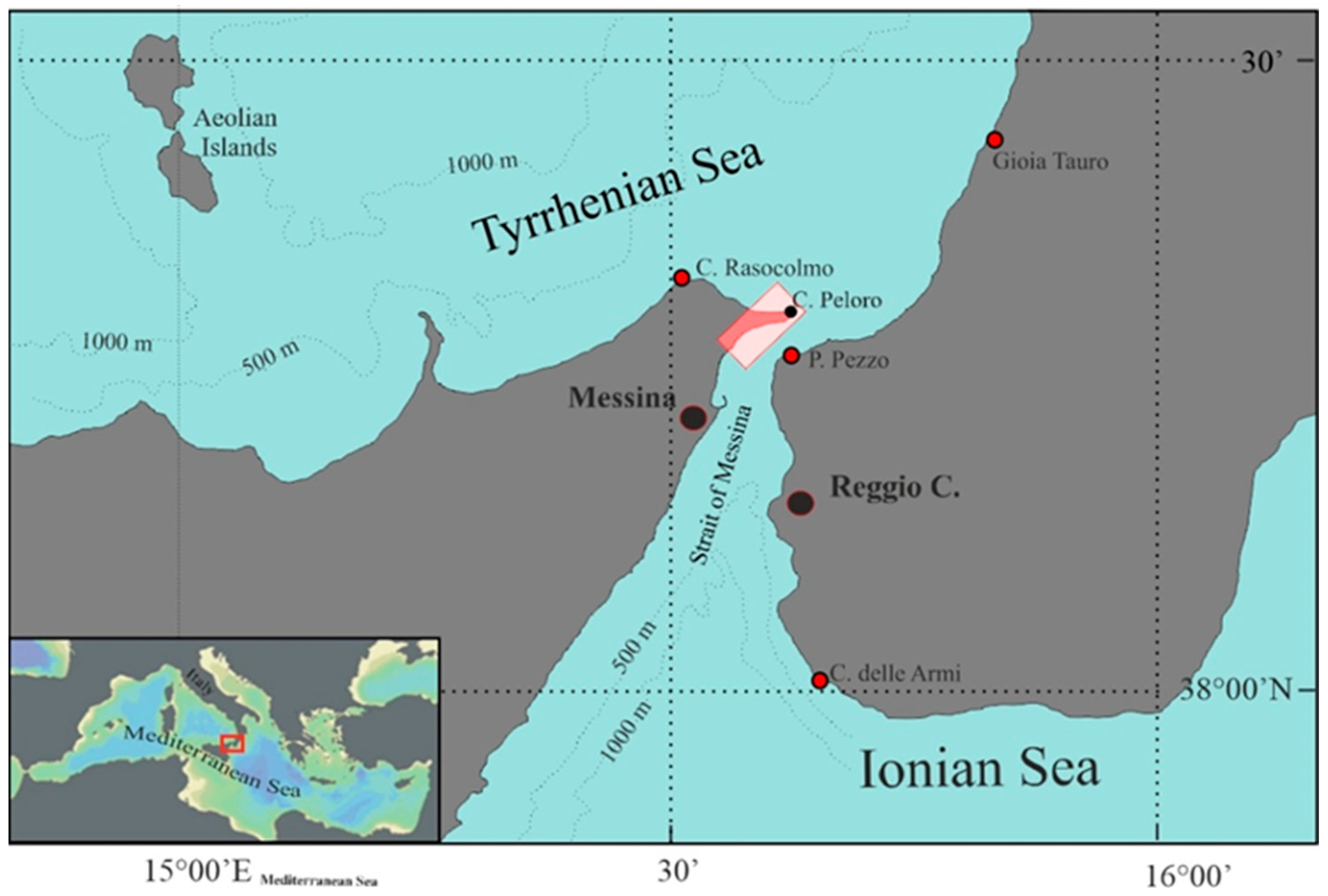

2.1. Study Area

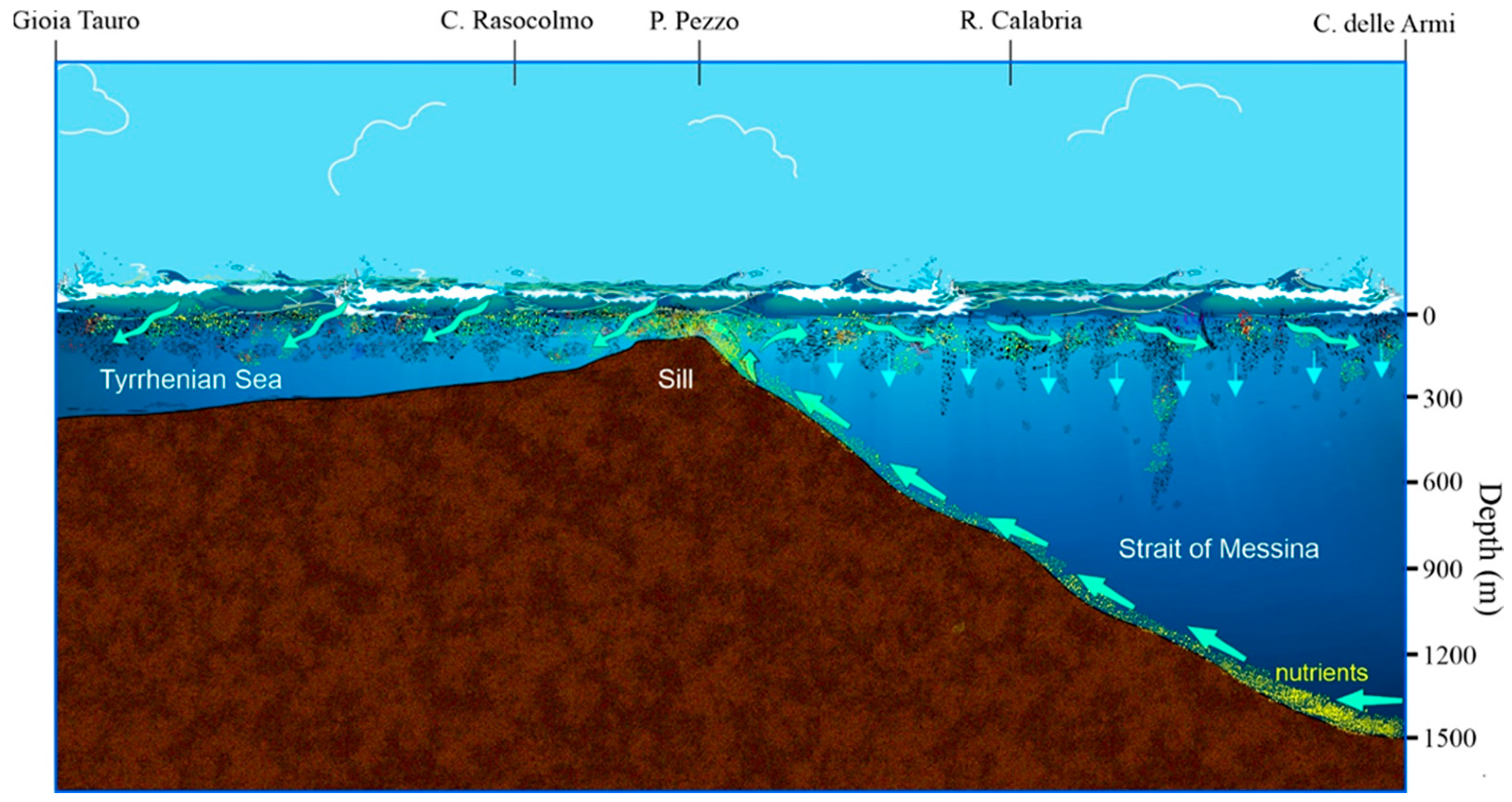

2.1.1. Physical Features

2.1.2. Ecological Features

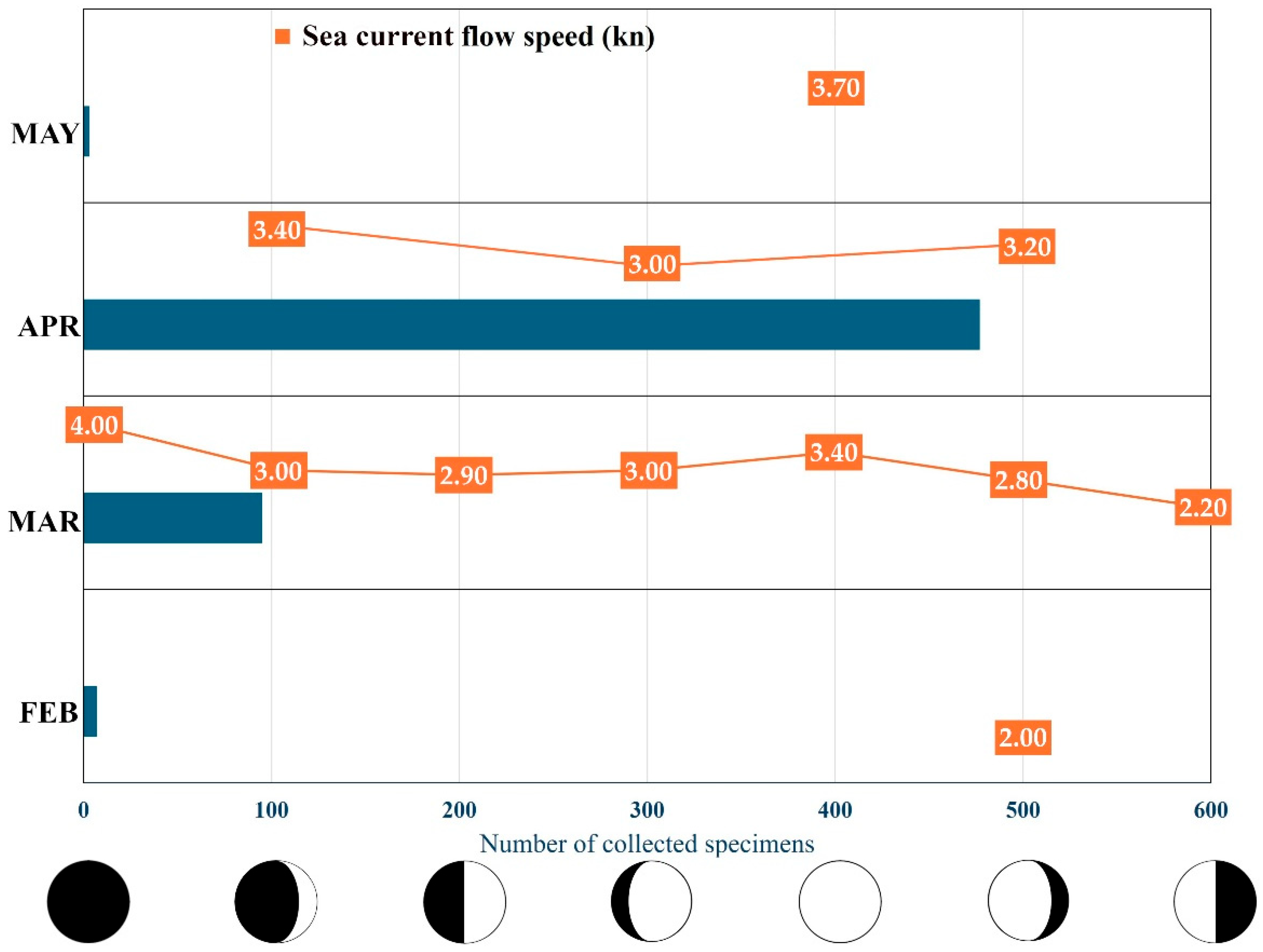

2.2. Samples Collection

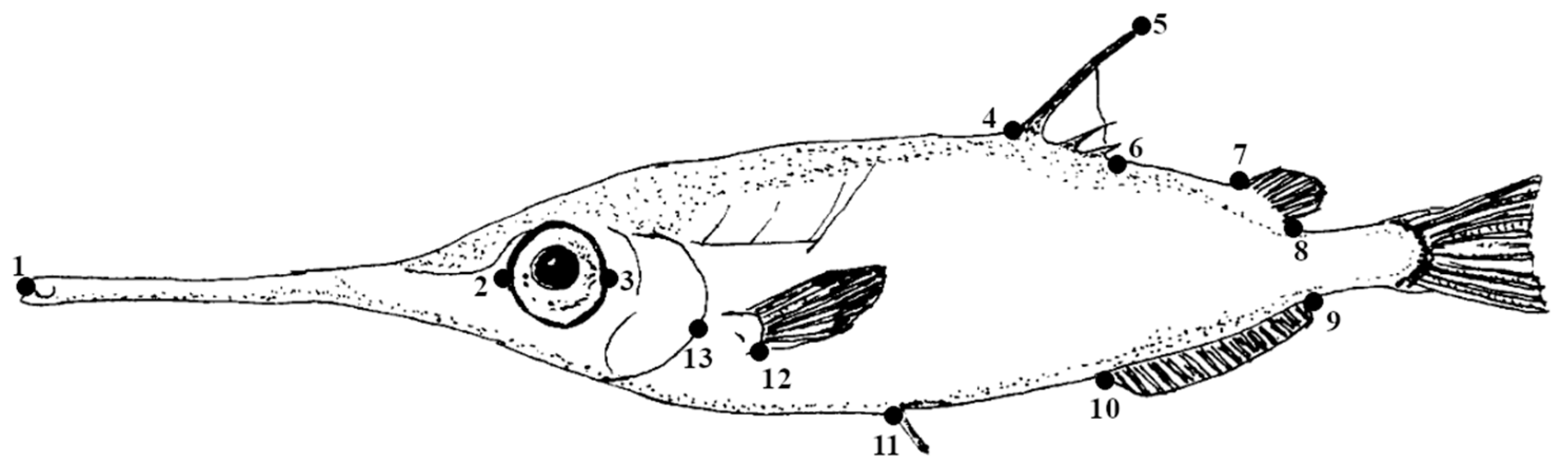

2.3. Data Analysis

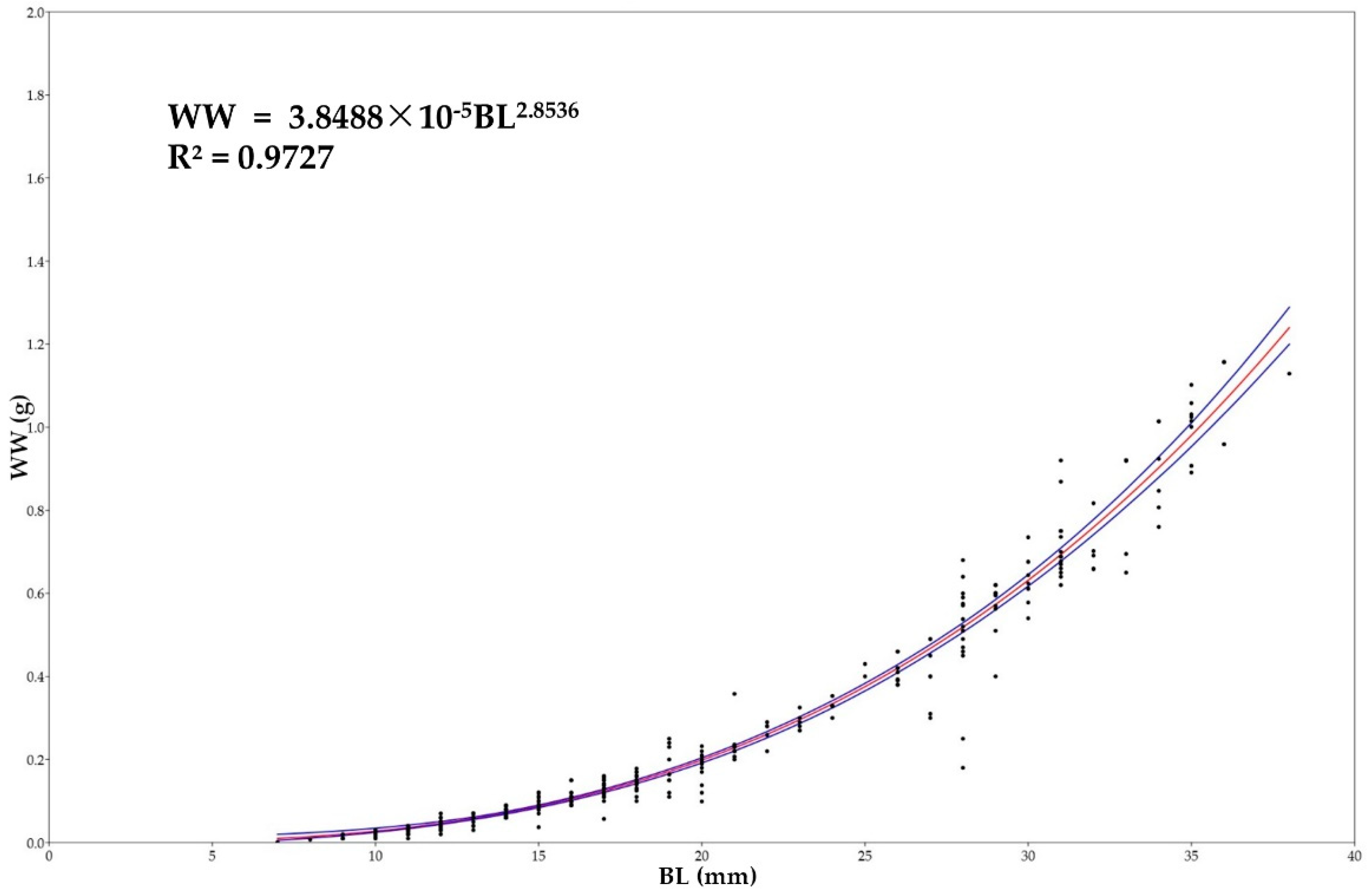

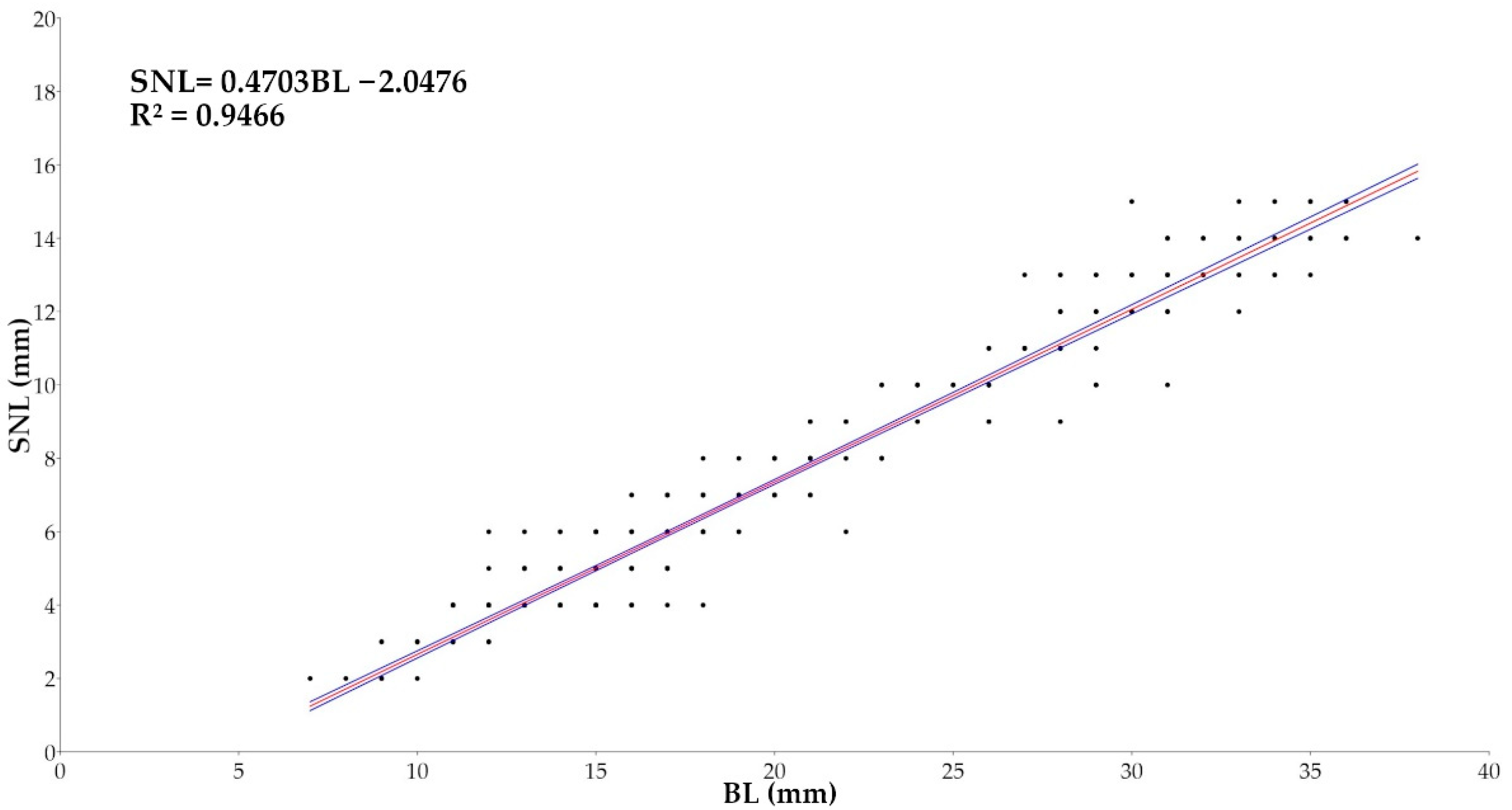

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matthiessen, B.; Fock, H.O.; von Westernhagen, H. Evidence for two sympatric species of snipefishes Macroramphosus spp. (Syngnathiformes, Centriscidae) on Great Meteor Seamount. Helgol. Mar. Res. 2003, 57, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brêthes, J.C. Contribution à l’étude des populations de Macrorhamphosus scolopax (L., 1758) et Macrorhamphosus gracilis (Lowe, 1839) des côtes atlantiques marocaines. Bull. L’institut Pêches Marit. Maroc 1979, 24, 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, T.A. Diet and morphological variation in snipefishes, presently recognized as Macrorhamphosus scolopax, from southeast Australia: Evidence for two sexually dimorphic species. Copeia 1984, 1984, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, C.A. On the systematics of Macrorhamphosus scolopax (Linnaeus, 1758) and Macrorhamphosus gracilis (Lowe, 1839). II—Multivariate morphometric analysis. Arq. Mus. Bocage 1993, 22, 383–402. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, E.; Sasaki, K.; Mitani, T.; Ishida, M.; Uehara, S. The occurrence of two species of Macroramphosus (Gasterosteiformes: Macroramphosidae) in Japan: Morphological and ecological observations on larvae, juveniles, and adults. Ichthyol. Res. 2004, 51, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, L. Age and growth of the snipefish, Macrorhamphosus spp., in the Portuguese continental waters. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2000, 80, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, I.H.; Kamal, M.; Mahfoud, B.; Najib, C. Snipefish (Macroramphosus spp.) abundance and trophic dynamics in response to upwelling regime in the atlantic region from cape blanc to cape boujdor (20°50 N to 26°00 N). Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2024, 9, e05136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthiessen, B.; Fock, H.O. A null model for the analysis of dietary overlap in Macroramphosus spp. at the Great Meteor Seamount (subtropical North-east Atlantic). Arch. Fish. Mar. Res. 2004, 51, 294–304. [Google Scholar]

- Assis, C. On the systematics of Macrorhamphosus scolopax (Linnaeus, 1758) and Macrorhamphosus gracilis (Lowe, 1839). I. A preliminary biometrical approach. Bol. Soc. Port. Ciências Nat. 1992, 25, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, M.; Murta, A.G.; Cabral, H.N. Discrimination of snipefish Macroramphosus species and boarfish Capros aper morphotypes through multivariate analysis of body shape. Helgol. Mar. Res. 2006, 60, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, B.; Martin, B.; Hirch, S. The benthopelagic fish fauna on the summit of Seine Seamount, NE Atlantic: Composition, population structure and diets. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2009, 56, 2705–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’onghia, G.; Tursi, A.; Maiorano, P.; Matarrese, A.; Panza, M. Demersal fish assemblages from the bathyal grounds of the Ionian Sea (middle-eastern Mediterranean). Ital. J. Zool. 1998, 65, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, J.-C.; Bertrand, J.A.; Relini, G.; Papaconstantinou, C.; Mazouni, N.; De Sola, L.G.; Durbec, J.-P.; Jukic-Peladic, S.; Souplet, A. Spatial pattern in species richness of demersal fish assemblages on the continental shelf of the northern Mediterranean Sea: A multiscale analysis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007, 341, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilecenoğlu, M.; Kaya, M.; Cihangir, B.; Çiçek, E. An updated checklist of the marine fishes of Turkey. Turk. J. Zool. 2014, 38, 901–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentieri, P.; Colloca, F.; Ardizzone, G. Day-night variations in the demersal nekton assemblage on the Mediterranean shelf-break. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2005, 63, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy-Haim, T.; Stern, N.; Sisma-Ventura, G. Trophic ecology of deep-sea megafauna in the ultra-oligotrophic Southeastern Mediterranean Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 857179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauria, V.; Gristina, M.; Fiorentino, F.; Attrill, M.J.; Garofalo, G. Spatial management units as an ecosystem-based approach for managing bottom-towed fisheries in the Central Mediterranean Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, M.; Lipej, L.; Dulčić, J.; Iglesias, S.P.; Goren, M. Evidence-based checklist of the Mediterranean Sea fishes. Zootaxa 2021, 4998, 1–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorica, B.; Vrgoč, N. Biometry and distribution of snipefish, Macroramphosus scolopax (Linnaeus, 1758), in the Adriatic Sea. Acta Adriat. 2005, 46, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Granata, A.; Cubeta, A.; Minutoli, R.; Bergamasco, A.; Guglielmo, L. Distribution and abundance of fish larvae in the northern Ionian Sea (Eastern Mediterranean). Helgol. Mar. Res. 2011, 65, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, D.; Profeta, A.; Busalacchi, B.; Minutoli, R.; Guglielmo, L.; Bergamasco, A.; Granata, A. Summer larval fish assemblages in the Southern Tyrrhenian Sea (Western Mediterranean Sea). Mar. Ecol. 2015, 36, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentieri, P.; Serpetti, N.; Colloca, F.; Criscoli, A.; Ardizzone, G. Food preferences and rhythms of feeding activity of two co-existing demersal fish, the longspine snipefish, Macroramphosus scolopax (Linnaeus, 1758), and the boarfish Capros aper (Linnaeus, 1758), on the Mediterranean deep shelf. Mar. Ecol. 2016, 37, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Tuvia, A. Revised list of the Mediterranean fishes of Israel. Isr. J. Zool. 1971, 20, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Papaconstantinou, C.; Tsimenidis, N. Some uncommon fishes from the Aegean Sea. Cybium 1979, 3, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Demetropoulos, A.; Neocleous, D. The fishes and crustaceans of Cyprus. Fish. Bull. Minist. Agric. Nat. Resour. Cyprus 1969, 1, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Tuvia, A. Collection of fishes from Cyprus. Bull. Res. Counc. Isr. 1962, 11, 132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Bilecenoglu, M. Status of the genus Macroramphosus (Syngnathiformes: Centriscidae) in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Zootaxa 2006, 1273, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocco, A. Su di alcuni nuovi pesci de’mari di Messina. G. Di Sci. Lett. E Arti Per La Sicil. 1829, 7, 138–147. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzarelli, G. Gli animali abissali e le correnti sottomarine dello Stretto di Messina. Riv. Mens. Di Pesca E Idrobiol. 1909, 11, 177–218. [Google Scholar]

- Genovese, S.; Guglielmo, L. Spiaggiamenti di fauna abissale nello Stretto di Messina. Atti Della Soc. Peloritana Sci. Fis. Mat. Nat. 1971, 17, 331–370. [Google Scholar]

- Di Carlo, B.S.; Costanzo, G.; Fresi, E.; Guglielmo, L. Feeding ecology and stranding mechanisms in two lanternfishes, Hygophum benoiti and Myctophum punctatum. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1982, 9, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, P.; Ammendolia, G.; Cavallaro, M.; Consoli, P.; Esposito, V.; Malara, D.; Rao, I.; Romeo, T.; Andaloro, F. Influence of lunar phases, winds and seasonality on the stranding of mesopelagic fish in the Strait of Messina (Central Mediterranean Sea). Mar. Ecol. 2017, 38, e12459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, P.; Pedà, C.; Malara, D.; Milisenda, G.; MacKenzie, B.R.; Esposito, V.; Consoli, P.; Vicchio, T.M.; Stipa, M.G.; Pagano, L. Importance of the lunar cycle on mesopelagic foraging by Atlantic Bluefin Tuna in the upwelling area of the Strait of Messina (Central Mediterranean Sea). Animals 2022, 12, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdar, A.; Cavaliere, A.; Cavallaro, G.; Giuffre, G.; Potoschi, A. Lo studio degli organismi marini spiaggiati nello Stretto di Messina negli ultimi due secoli. Nat. Sicil. 1983, 7, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Berdar, A.; Cavallaro, G.; Giuffre, G.; Potoschi, A. Contributo alla conoscenza dei pesci spiaggiati lungo il litorale siciliano dello Stretto di Messina. Mem. Biol. Mar. Oceanogr. 1981, 7, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Berdar, A.; Berdar, N.; Costa, F. Diminuzione di ittiofauna meso e batipelagica spiaggiata nello Stretto di Messina. Mem. Biol. Mar. Oceanogr. 1988, 17, 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, F. I Pesci del Mediterraneo: Stadi Larvali e Giovanili; Grafo Editor: Brescia, Italia, 1999; p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro, M.; Villari, A.; Ammendolia, G.; Spadola, F.; Bonfiglio, L.; Mangano, G.; Panzera, M. Le collezioni di faune ittiche mesopelagiche e malacologica “A. Villari” del Museo della Fauna di Messina. In Proceedings of the Atti XXV Congresso Associazione Nazionale Musei Scientifici, Torino, Italia, 11–13 November 2015; Università degli Studi di Torino: Turin, Italy, 2015; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro, M.; Ammendolia, G.; Rao, I.; Villari, A.; Battaglia, P. Variazioni pluriennali del fenomeno dello spiaggiamento di specie ittiche nello Stretto di Messina, con particolare attenzione alle specie mesopelagiche. Ann. Ser. Hist. Nat. 2021, 31, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bignami, F.; Salusti, E. Tidal currents and transient phenomena in the Strait of Messina: A review. In The Physical Oceanography of Sea Straits; Pratt, L.J., Ed.; NATO ASI Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1990; Volume 318, pp. 95–124. [Google Scholar]

- Mosetti, R. Optimal policies in a Bioeconomic model of eutrophication. Appl. Math. Comput. 1988, 26, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, T.S.; Salusti, E.; Settimi, D. Tidal forcing of the water mass interface in the Strait of Messina. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 1984, 89, 2013–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercelli, F. Crociere per lo Studio dei Fenomeni Nello Stretto di Messina; Office Grafiche C. Ferrari: Venezia, Italia, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Vercelli, F. Il Regime Delle Correnti e Delle Maree Nello Stretto di Messina; Office Grafiche C. Ferrari: Venezia, Italia, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Mosetti, F. Tidal and other currents in the Straits of Messina. In The Straits of Messina ecosystem, Proceedings of the Symposium, Messina, Italia, 4–16 April 1991; Guglielmo, L., Manganaro, A., De Domenico, E., Eds.; Università degli Studi di Messina: Messina, Italia, 1995; pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Povero, P.; Hopkins, T.; Fabiano, M. Oxygen and nutrient observations in the southern Tyrrhenian Sea. Oceanol. Acta 1990, 13, 299–305. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmo, L.; Crescenti, N.; Costanzo, G.; Zagami, G. Zooplankton and micronekton communities in the Straits of Messina. In The Straits of Messina ecosystem, Proceedings of the Symposium, Messina, Italia, 4–16 April 1991; Guglielmo, L., Manganaro, A., De Domenico, E., Eds.; Università degli Studi di Messina: Messina, Italia, 1995; pp. 247–270. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmo, L.; Marabello, F.; Vanucci, S. The role of the mesopelagic fishes in the pelagic food web of the Straits of Messina. In The Straits of Messina ecosystem, Proceedings of the Symposium, Messina, Italia, 4–16 April 1991; Guglielmo, L., Manganaro, A., De Domenico, E., Eds.; Università degli Studi di Messina: Messina, Italia, 1995; pp. 223–246. [Google Scholar]

- Decembrini, F.; Hopkins, T.; Azzaro, F. Variability and sustenance of the deep-chlorophyll maximum over a narrow shelf, Augusta Gulf (Sicily). Chem. Ecol. 2004, 20, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzaro, F.; Decembrini, F.; Raffa, F.; Crisafi, E. Seasonal variability of phytoplankton fluorescence in relation to the Straits of Messina (Sicily) tidal upwelling. Ocean Sci. 2007, 3, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currieri, G. Sulle cause meccanico biologiche della formazione degli accumuli di plancton. Boll. Soc. Zool. It. I 1900, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Zagami, G.; Badalamenti, F.; Guglielmo, L.; Manganaro, A. Short-term variations of the zooplankton community near the Straits of Messina (North-eastern Sicily): Relationships with the hydrodynamic regime. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 1996, 42, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmo, L. Distribuzione dei chetognati nell’area idrografica dello Stretto di Messina. Pubbl. Stn. Zool. Napoli 1976, 40, 34–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sparla, M.; Guglielmo, L. Distribuzione del microzooplancton nello Stretto di Messina (estate 1990). In Proceedings of the Atti X Congresso AIOL, Alassio, Italia, 4–6 November 1992; Aiol: Alassio, Italia, 1994; pp. 307–325. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia, P.; Andaloro, F.; Esposito, V.; Granata, A.; Guglielmo, L.; Guglielmo, R.; Musolino, S.; Romeo, T.; Zagami, G. Diet and trophic ecology of the lanternfish Electrona risso (Cocco 1829) in the Strait of Messina (central Mediterranean Sea) and potential resource utilization from the Deep Scattering Layer (DSL). J. Mar. Syst. 2016, 159, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, P.; Andaloro, F.; Consoli, P.; Esposito, V.; Malara, D.; Musolino, S.; Pedà, C.; Romeo, T. Feeding habits of the Atlantic bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus (L. 1758), in the central Mediterranean Sea (Strait of Messina). Helgol. Mar. Res. 2013, 67, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, A.; Tringali, L.; Bruno, R.; Guglielmo, L.; Guglielmo, R.; Minutoli, R. Lo Stretto di Messina: Via di migrazione per pesci e mammiferi marini. In Sviluppo Sostenibile dei Trasporti Marittimi nel Mediterraneo; Pellegrino, F., Ed.; Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane (ESI): Napoli, Italia, 2013; pp. 691–755. [Google Scholar]

- Ricker, W.E. Computation and interpretation of biological statistics of fish populations. Fish. Res. Board Can. Bull. 1975, 191, 1–382. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. Past: Paleontological statistics software package for educaton and data anlysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 1. Available online: https://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/issue1_01.htm (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Zar, J.H. Biostatistical Analysis; Pearson: New Dehli, India, 2014; p. 756. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, P.; Hoareau, T.B.; Lord, C.; Ah-Yane, O.; Gimonneau, G.; Robinet, T.; Valade, P. Characterisation of post-larval to juvenile stages, metamorphosis and recruitment of an amphidromous goby, Sicyopterus lagocephalus (Pallas) (Teleostei: Gobiidae: Sicydiinae). Mar. Freshw. Res. 2008, 59, 876–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, P.J.; Cowling, M.J. Buoyancy mechanisms of marine organisms: Lessons from nature. Underw. Technol. 1999, 24, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragheb, E. Length-weight relationship and well-being factors of 33 fish species caught by gillnets from the Egyptian Mediterranean waters off Alexandria. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2023, 49, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourlière, F. Fishes of the North-eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean. Poissons de l’Atlantique du Nord-est et de la Méditerranée; Whitehead, P.J.P., Bauchot, M.L., Hureau, J.C., Nielsen, J., Tortonese, Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1984; Volume I, 1984, Revue d’Écologie (La Terre et La Vie), 40; p. 548. [Google Scholar]

- Angiulli, E.; Sola, L.; Ardizzone, G.; Fassatoui, C.; Rossi, A.R. Phylogeography of the common pandora Pagellus erythrinus in the central Mediterranean Sea: Sympatric mitochondrial lineages and genetic homogeneity. Mar. Biol. Res. 2016, 12, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constant, M.; Reynaud, M.; Weiss, L.; Ludwig, W.; Kerhervé, P. Ingested microplastics in 18 local fish species from the northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Microplastics 2022, 1, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schluter, D. Adaptive radiation in sticklebacks: Size, shape, and habitat use efficiency. Ecology 1993, 74, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, S.J.; Goodearly, T.; Wainwright, P.C. Extremely fast feeding strikes are powered by elastic recoil in a seahorse relative, the snipefish, Macroramphosus scolopax. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 285, 20181078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, V.C.; Amore, E.; Cavallaro, L.; Cozzo, G.; Foti, E. Sand waves in the Messina strait, Italy. J. Coast. Res. 2002, 36, 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortier, L. Export production and the production of fish larvae and their prey at hydrodynamic singularities. In The Straits of Messina Ecosystem, Proceedings of the Symposium, Messina, Italia, 4–16 April 1991; Guglielmo, L., Manganaro, A., De Domenico, E., Eds.; Università degli Studi di Messina: Messina, Italia, 1995; pp. 213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Brancato, G.; Minutoli, R.; Granata, A.; Sidoti, O.; Guglielmo, L. Diversity and vertical migration of euphausiids across the Straits of Messina area. In Mediterranean Ecosystems: Structures and Processes; Faranda, F.M., Guglielmo, L., Spezie, G., Eds.; Springer: Milano, Italia, 2001; pp. 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Bergamasco, A.; Cucco, A.; Guglielmo, L.; Minutoli, R.; Quattrocchi, G.; Guglielmo, R.; Palumbo, F.; Pansera, M.; Zagami, G.; Vodopivec, M. Observing and modeling long-term persistence of P. noctiluca in coupled complementary marine systems (Southern Tyrrhenian Sea and Messina Strait). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, L.M. Maturation cycle in the female gonad of the snipefish, Macrorhamphosus gracilis (Lowe, 1839)(Gasterosteiformes, Macrorhamphosidae), off the western coast of Portugal. Investig. Pesq. 1988, 52, 355–374. [Google Scholar]

- Matallanas, J. Aspectos generales del regimen alimentario de Macroramphosus scolopax (Linnaeus 1758) (Pisces, Macroramphosidae) en las costas catalanas (Mediterrâneo occidental). Cah. De Biol. Mar. 1982, 23, 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, P.J.; Clifton, K.B.; Hernandez, P.; Eggold, B.T. Ecomorphological correlates in ten species of subtropical seagrass fishes: Diet and microhabitat utilization. Environ. Biol. Fishes 1995, 44, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogland, R.; Morris, D.; Tinbergen, N. The spines of sticklebacks (Gasterosteus and Pygosteus) as means of defence against predators (Perca and Esox). Behaviour 1956, 10, 205–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosher, B.T.; Newton, S.H.; Fine, M.L. The spines of the channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus, as an anti-predator adaptation: An experimental study. Ethology 2006, 112, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenici, P. Escape responses in fish: Kinematics, performance and behavior. In Fish Locomotion: An Eco-Ethological Perspective; Domenici, P., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 123–170. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran, A.E. The adaptive significance of schooling as an anti-predator defence in fish. Ann. Zool. Fenn. 1990, 27, 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- McFall-Ngai, M.J. Crypsis in the pelagic environment. Am. Zool. 1990, 30, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J. Vision and lack of vision in the ocean. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R494–R502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granata, A.; Bergamasco, A.; Battaglia, P.; Milisenda, G.; Pansera, M.; Bonanzinga, V.; Arena, G.; Andaloro, F.; Giacobbe, S.; Greco, S. Vertical distribution and diel migration of zooplankton and micronekton in Polcevera submarine canyon of the Ligurian mesopelagic zone (NW Mediterranean Sea). Prog. Oceanogr. 2020, 183, 102298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A. Feeding habits of John Dory, Zeus faber, off the Portuguese continental coast. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 1999, 79, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morato, T.; Solà, E.; Grós, M.P.; Menezes, G. Feeding habits of two congener species of seabreams, Pagellus bogaraveo and Pagellus acarne, off the Azores (northeastern Atlantic) during spring of 1996 and 1997. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2001, 69, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Gravino, F.; Dimech, M.; Schembri, P.J. Feeding habits of the small-spotted catshark Scyliorhinus canicula (L., 1758) in the central Mediterranean. Rapp. Comm. Int. Mer Mediterr. 2010, 39, 538. [Google Scholar]

- D’Iglio, C.; Porcino, N.; Savoca, S.; Profeta, A.; Perdichizzi, A.; Armeli Minicante, E.; Salvati, D.; Soraci, F.; Rinelli, P.; Giordano, D. Ontogenetic shift and feeding habits of the European hake (Merluccius merluccius L., 1758) in Central and Southern Tyrrhenian Sea (Western Mediterranean Sea): A comparison between past and present data. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e8634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuset, V.M.; Lombarte, A.; Assis, C.A. Otolith atlas for the western Mediterranean, north and central eastern Atlantic. Sci. Mar. 2008, 72, 7–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | N | Date | N | Date | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 January 2025 | 0 | 5 March 2025 | 0 | 23 March 2025 | 3 |

| 1 February 2025 | 0 | 6 March 2025 | 6 | 3 April 2025 | 453 |

| 2 February 2025 | 0 | 10 March 2025 | 2 | 10 April 2025 | 1 |

| 13 February 2025 | 0 | 11 March 2025 | 0 | 14 April 2025 | 4 |

| 18 February 2025 | 7 | 14 March 2025 | 6 | 15 April 2025 | 18 |

| 20 February 2025 | 0 | 18 March 2025 | 53 | 17 April 2025 | 1 |

| 1 March 2025 | 3 | 19 March 2025 | 3 | 14 May 2025 | 3 |

| 2 March 2025 | 1 | 20 March 2025 | 7 | ||

| 4 March 2025 | 7 | 22 March 2025 | 5 |

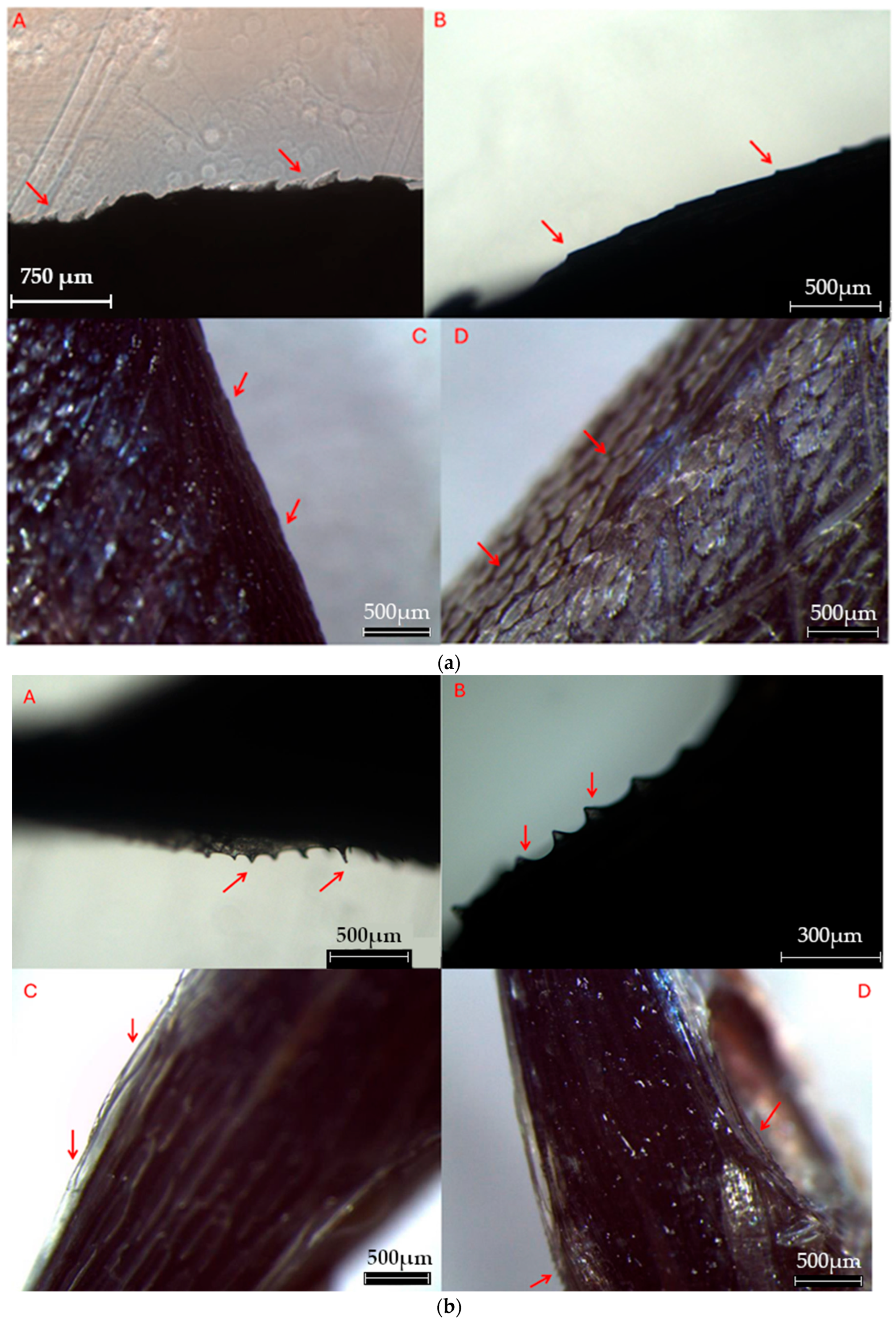

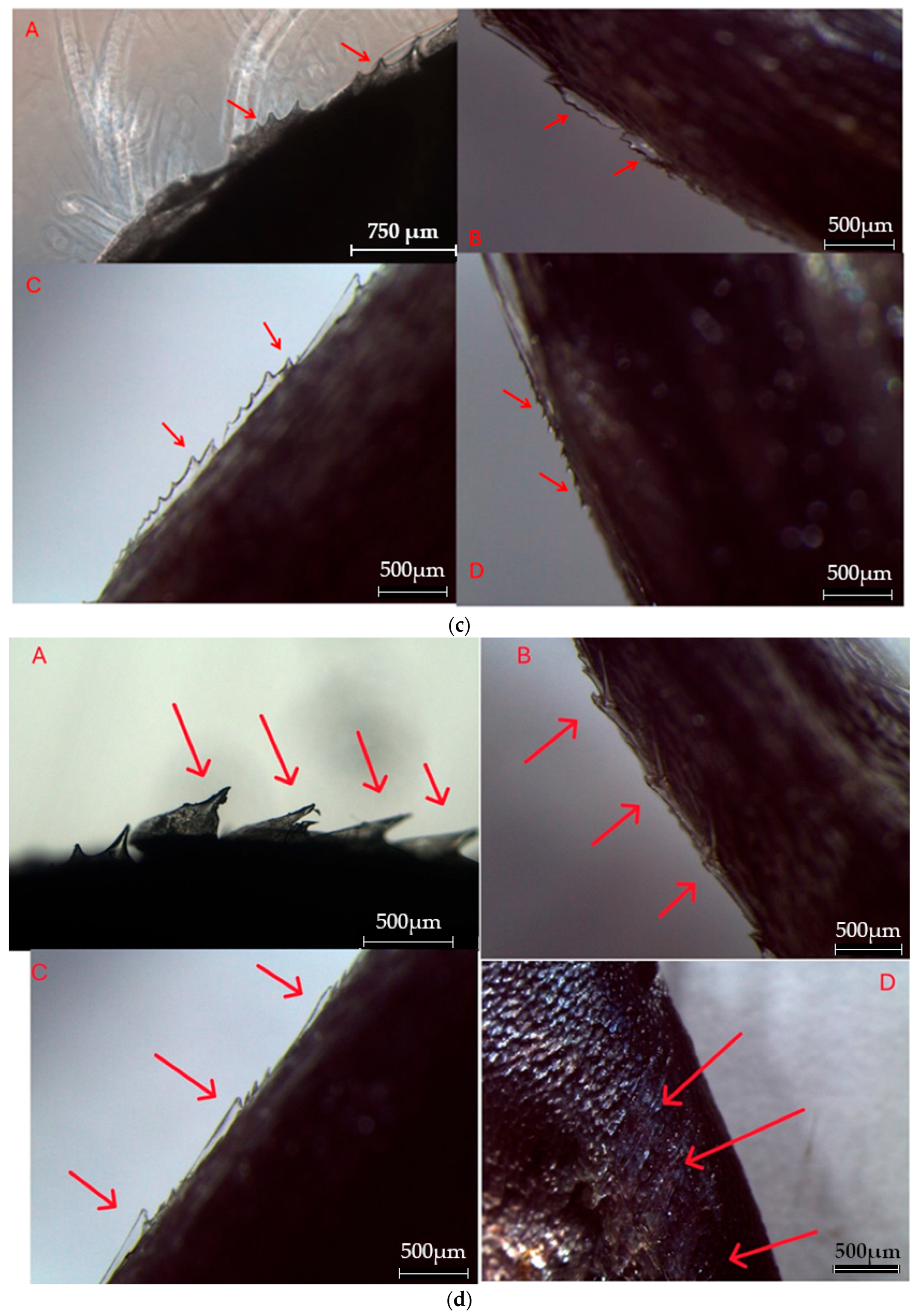

| M. gracilis | M. scolopax | |

|---|---|---|

| Ventral body profile in larval and juvenile | Straight | Notched |

| Body color | Dark dorsally, with silver sides | Red-orange with few melanophores dorsally |

| Posterior margin of dorsal fin spine (spike) in specimens larger than 50 mm SL | Smooth | Serrated with spinules |

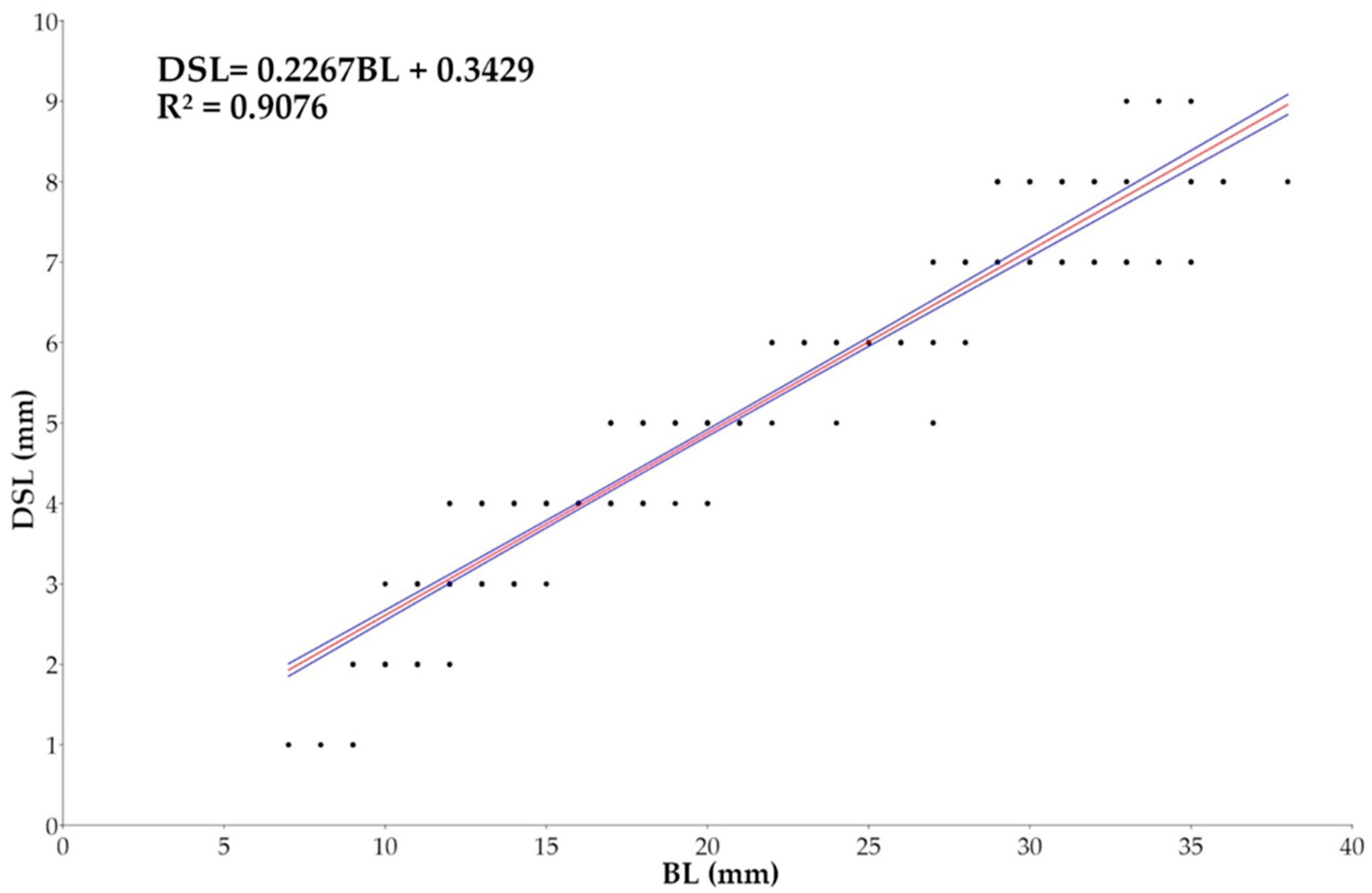

| Length of dorsal fin spine (DSL, Dorsal Spine Length; 4–5) | Relatively short: 17.9–32.6% BL. 62.4–138% distance between dorsal spine–second dorsal fin origin (DSFD, Dorsal Spine Fin Distance; 4–7). | Long: 23.7–46.2% BL. 98.9–231% distance between dorsal spine–second dorsal fin origin (DSFD, Dorsal Spine Fin Distance; 4–7). |

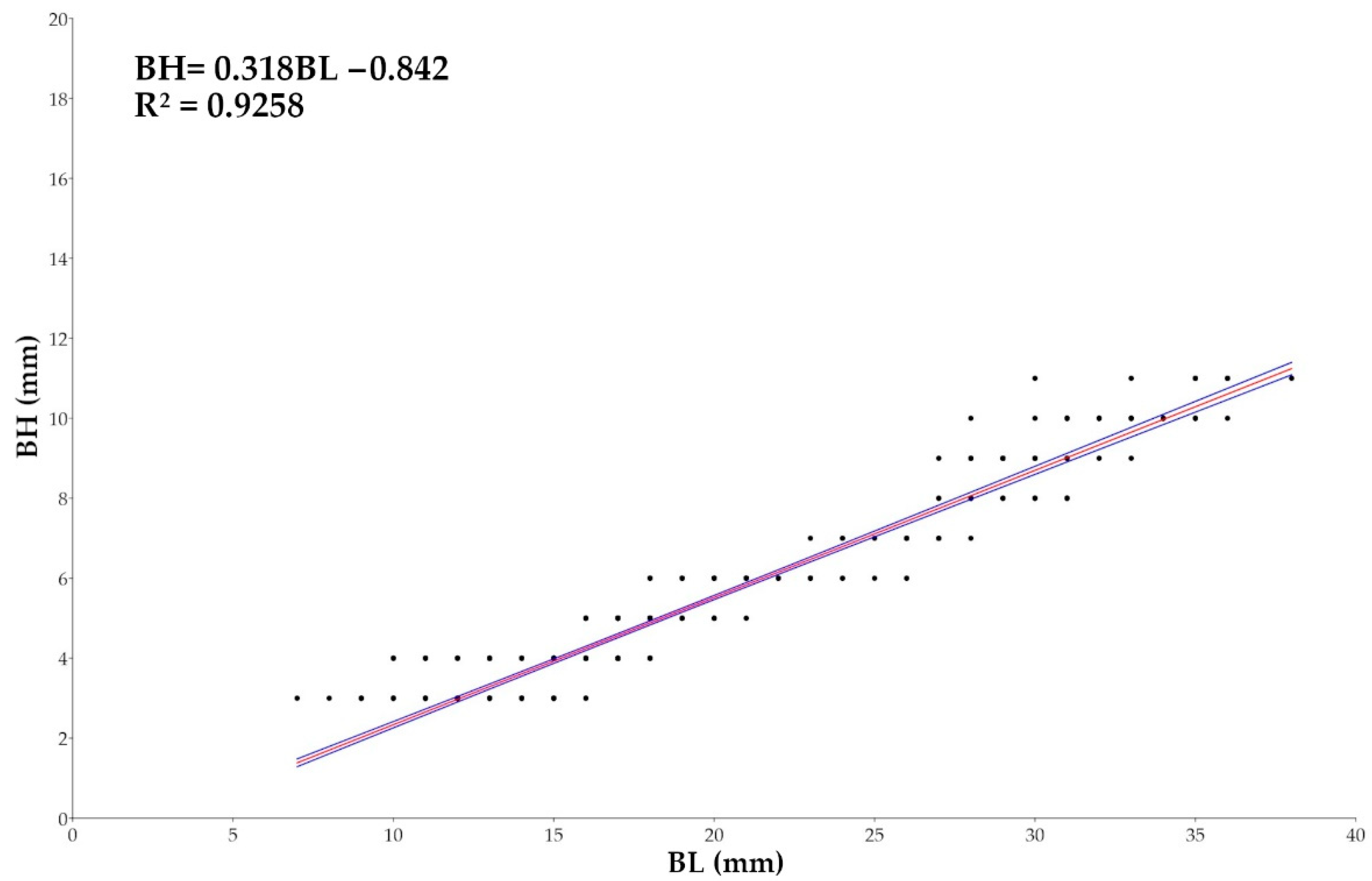

| Body Height (BH; 4–10) | Relatively slender: 20.9–30.8% BL. | Relatively deep: 23.4–36.7% BL. |

| Species | February | March | April | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teleosts | Argyropelecus hemigymnus | - | 11 | - |

| Argyropelecus hemigymnus juv. | - | 8 | - | |

| Conger sp. juv. | - | 1 | - | |

| Cyclothone braueri | - | 6 | - | |

| Diaphus metopoclampus juv. | - | 1 | - | |

| Electrona risso juv. | - | 2 | - | |

| Engraulis encrasicolus | - | 1 | - | |

| Hygophum benoiti | - | 25 | 36 | |

| Hygophum hygomii juv. | - | - | 2 | |

| Maurolicus muelleri | - | - | 1 | |

| Myctophum punctatum | - | - | 1 | |

| Microstoma microstoma | - | 1 | 1 | |

| Microstoma microstoma juv. | - | - | 4 | |

| Nansenia oblita | - | - | 1 | |

| Nansenia oblita juv. | - | 1 | - | |

| Vinciguerria attenuata | - | 6 | - | |

| Vinciguerria attenuata juv. | - | - | 1 | |

| Amphipods | Lestrigonus schizogeneios | - | 6 | - |

| Phronima atlantica | - | 4 | 1 | |

| Phronima sp. | - | 11 | 1 | |

| Phrosina semilunata | - | 2 | - | |

| Scina crassicornis | - | 1 | - | |

| Euphausiids | Euphausia krohni | - | 1 | - |

| Thysanoessa gregaria | - | 45 | - | |

| Mysids | Siriella sp. | - | - | 1 |

| Pteropods | Cymbulia peronii | 1 | - | 3 |

| Macroramphosus gracilis Features | Macroramphosus scolopax Features | Outlier Features | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. | Straight Ventral Body Profile | Silver Body, Dorsally Dark | DSL/ BL Ratio 17.9–32.6% | DSL/ DSFD Ratio 62.4–138% | BH/BL Ratio 20.9–30.8% | Notched Ventral Body Profile | Red-Orange Body | DSL/ BL Ratio 23.7–46.2% | DSL/ DSFD Ratio 98.9–231% | BH/BL Ratio 23.4–36.7% | Silver Body, Light Red Shaded, Dorsally Dark | DSL/ DSFD Ratio < 62.4% | BH/ BL Ratio > 36.7% | |

| 490 | • | • | • | • | • | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | |

| 61 | • | • | • | • | / | / | / | / | / | • | / | / | / | |

| 5 | • | • | • | • | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | • | |

| 2 | • | • | • | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | • | • | |

| 4 | • | / | • | • | • | / | / | / | / | / | • | / | / | |

| 3 | • | / | • | • | / | / | / | / | / | • | • | / | / | |

| 2 | • | • | • | / | • | / | / | / | / | / | / | • | / | |

| 1 | • | • | / | • | / | / | / | • | / | • | / | / | / | |

| 3 | • | • | / | • | • | / | / | • | / | / | / | / | / | |

| Tot | 571 | 571 | 564 | 567 | 567 | 499 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 65 | 7 | 4 | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Geraci, A.; Scipilliti, A.; Guglielmo, Y.; Minutoli, R.; Di Paola, D.; Carbonara, P.; Guglielmo, L.; Genovese, S.; Ferreri, R.; Granata, A. Massive Stranding of Macroramphosus gracilis (Lowe, 1839) in the Strait of Messina (Central Mediterranean Sea): Somatic Features of Different Post-Larval Development Stages. Water 2026, 18, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020156

Geraci A, Scipilliti A, Guglielmo Y, Minutoli R, Di Paola D, Carbonara P, Guglielmo L, Genovese S, Ferreri R, Granata A. Massive Stranding of Macroramphosus gracilis (Lowe, 1839) in the Strait of Messina (Central Mediterranean Sea): Somatic Features of Different Post-Larval Development Stages. Water. 2026; 18(2):156. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020156

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeraci, Andrea, Andrea Scipilliti, Ylenia Guglielmo, Roberta Minutoli, Davide Di Paola, Pierluigi Carbonara, Letterio Guglielmo, Simona Genovese, Rosalia Ferreri, and Antonia Granata. 2026. "Massive Stranding of Macroramphosus gracilis (Lowe, 1839) in the Strait of Messina (Central Mediterranean Sea): Somatic Features of Different Post-Larval Development Stages" Water 18, no. 2: 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020156

APA StyleGeraci, A., Scipilliti, A., Guglielmo, Y., Minutoli, R., Di Paola, D., Carbonara, P., Guglielmo, L., Genovese, S., Ferreri, R., & Granata, A. (2026). Massive Stranding of Macroramphosus gracilis (Lowe, 1839) in the Strait of Messina (Central Mediterranean Sea): Somatic Features of Different Post-Larval Development Stages. Water, 18(2), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18020156