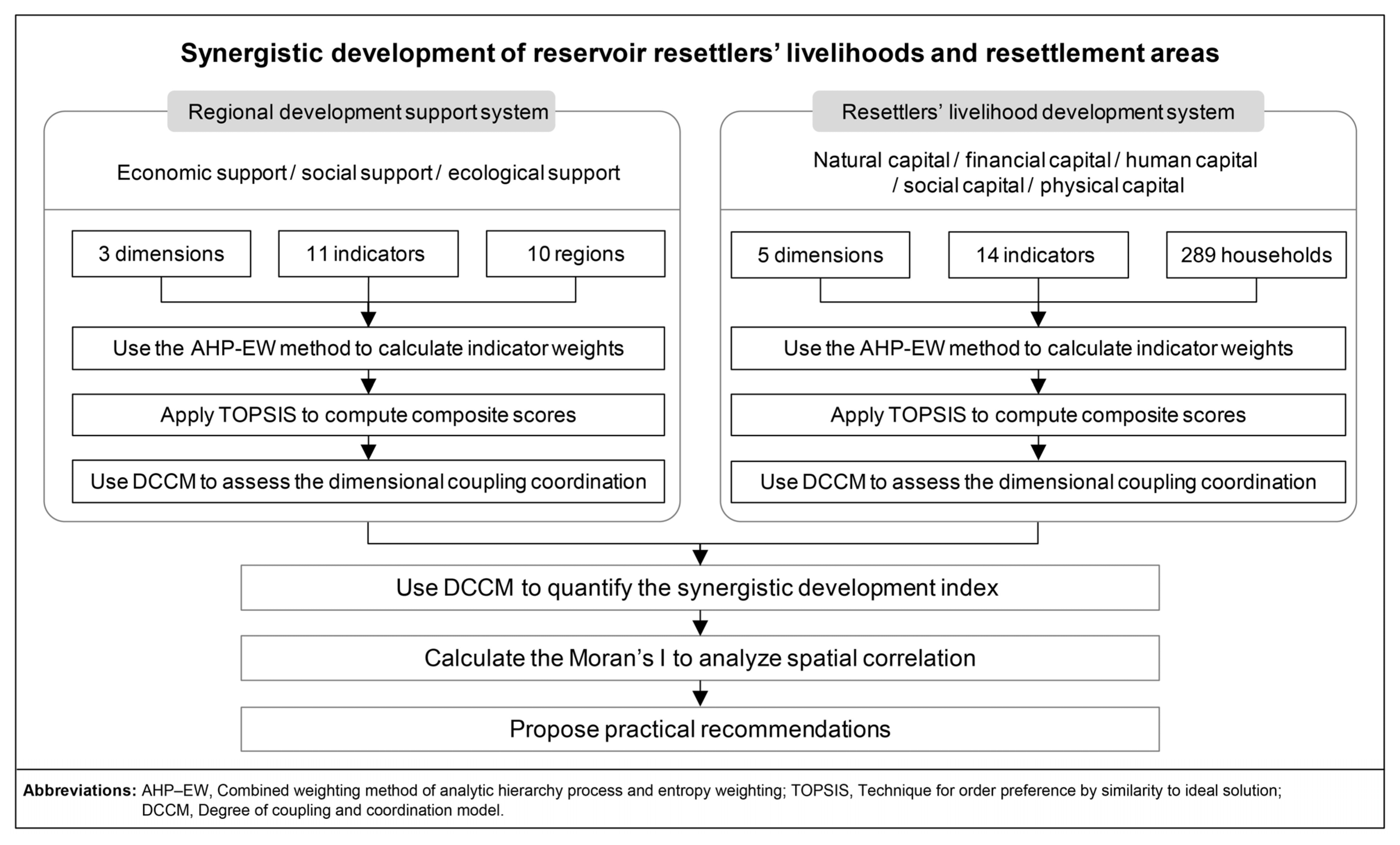

3.2. Regional Development Support System Analysis

3.2.1. Indicator Weight Determination for the Regional Development Support System

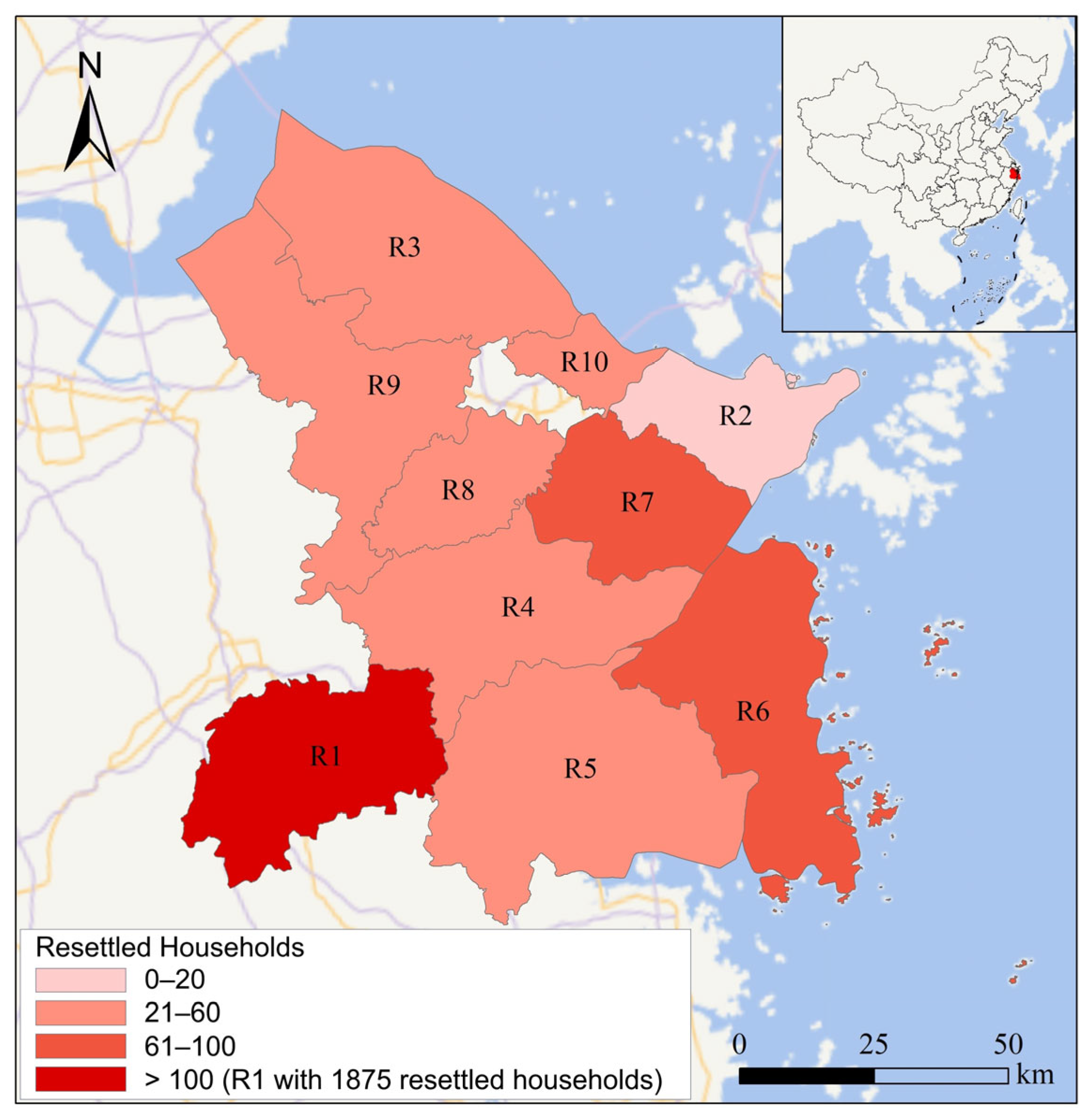

Using 2023 government statistical data for each region and information provided by resettlement management agencies, the AHP–EW method was applied to calculate indicator weights for the RDS subsystem based on evaluations from five domain experts (

Table 6). All judgment matrices satisfied the consistency requirement (CR < 0.1). The resulting weight distribution reflects the coordinated logic characteristic of hydropower resettlement—economic priority, ecological constraint, and social foundation—highlighting the interdependent relationship between development, environmental protection, and livelihood support.

ES is the primary driver of coordinated development, with a combined weight of 0.503, functioning as the essential linkage between resettlers’ livelihoods and regional development. Industrial expansion and employment opportunities directly influence household income levels. The AHP-derived subjective weight for this dimension is 0.633, reflecting policy prioritization of economic growth, whereas the entropy-based objective weight is 0.308, indicating substantial data dispersion. Among the indicators, the employment absorption rate of resettler industries (ES4) holds the highest weight (0.437), signifying the capacity of industries to absorb labor. The performance of characteristic industries (ES3) also ranks highly (weight 0.271), representing the alignment between regional industrial structures and resettlers’ livelihood needs. These findings correspond to a synergistic development model characterized by “employment-led, industry-driven” growth.

ECS captures the distinctive ecological constraints and requirements of reservoir resettlement, with a combined weight of 0.271—higher than that of Social Support. The ecological service supply indicator (ECS2), encompassing water quality, forest coverage, ecological engineering, and pollution control, carries the greatest weight (0.462), serving as a core ecological constraint. The agricultural output value per unit sown area (ECS3) and per capita cultivated land area (ECS1) reflect the limited agricultural land resources in Zhejiang Province, underscoring the ecological specificity of the study area.

SS provides the foundational safeguards for livelihood development, with a combined weight of 0.226. SS indicators such as education, vocational training, and community services underpin the realization of synergistic development. The coverage of specialized resettler training (SS3) acts as a key linkage between industrial demand and skill enhancement (weight 0.381), while community service coverage (SS2) and infrastructure convenience (SS4) contribute to social integration and household livelihood stability.

3.2.2. System Performance Evaluation

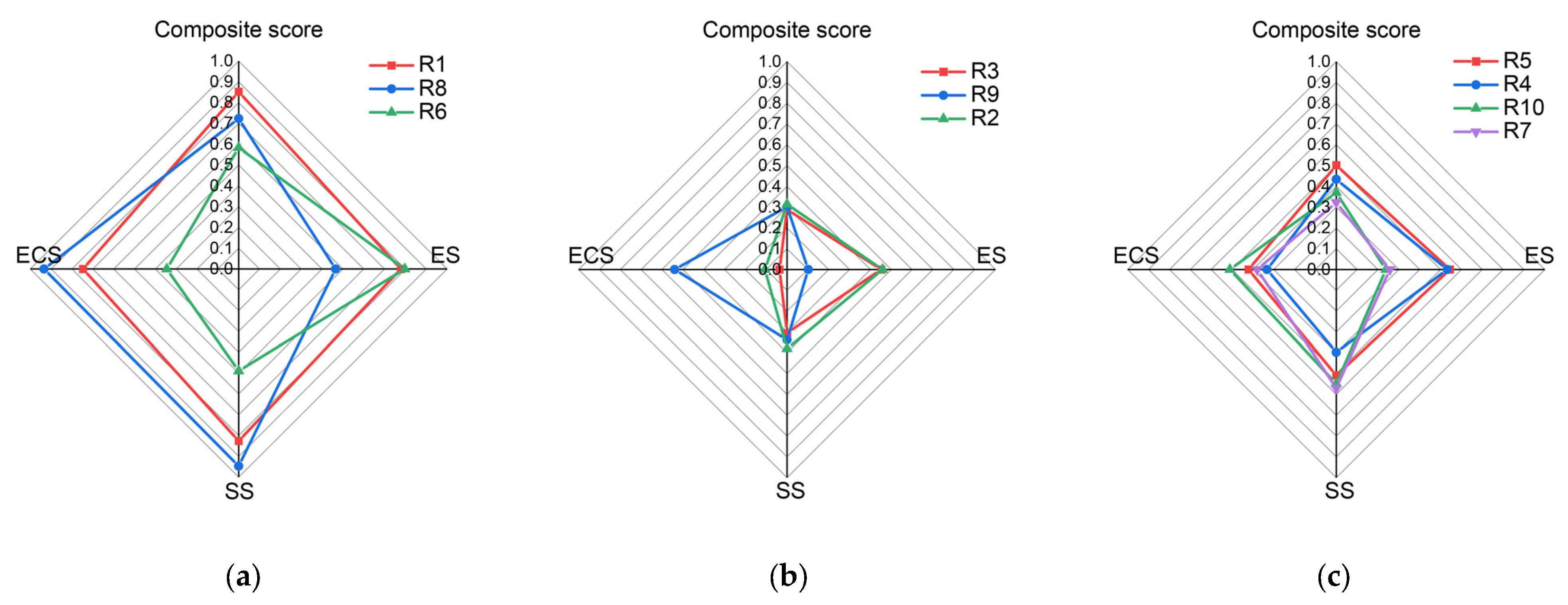

Using the validated indicator weights and expert-reviewed data, the TOPSIS method was applied to calculate scores for each dimension and to derive composite measurements for the RDS subsystem (

Table 7). The results reveal a distinct gradient pattern described as “high-level regions with balanced development and low-level regions with pronounced deficiencies”.

High-performing regions include R1 (0.852), R8 (0.728), and R6 (0.597), all exhibiting balanced and synergistic performance across the three dimensions. Radar charts for these regions are presented in

Figure 3a. As the core water-source area, R1 demonstrates strong integration between ECS (score: 0.747) and ES (score: 0.778), while also maintaining high performance in SS. R8 benefits from a well-developed cultural and tourism industry, achieving the highest scores in both SS and ECS, reflecting a dual-advantage development model. R6, identified as an industrially advanced county, displays strong economic performance and high employment absorption capacity, resulting in the highest ES score among all regions.

Low-level regions include R3 (0.285), R9 (0.321), and R2 (0.323), each constrained by significant deficiencies in one or more key dimensions, as illustrated in

Figure 3b. R3, a port-industrial hub dominated by heavy industry, performs poorly in SS (0.305) and extremely low in ECS (0.036). R9 exhibits weak economic development, with ES1, ES3, and ES4 identified as major limiting indicators. R2, characterized by a petrochemical-led economy, demonstrates a narrow industrial base and heightened ecological risk, resulting in low scores in both SS and ECS.

Medium-level regions—R5 (0.519), R4 (0.451), R10 (0.392), and R7 (0.349)—display mixed performance, with distinct strengths and weaknesses, as shown in

Figure 3c. R5 has a well-developed commercial and service sector but limited employment alignment for resettlers, reflected in a low ES4 score. R10 performs relatively well in ECS, but its small industrial base constrains job creation, leading to a weak ES dimension.

Dimensional analysis confirms consistency between RDS rankings and the actual economic, social, and ecological profiles of the regions. For example, in the ES dimension, regions where tertiary industries contribute more than 50% of GDP (e.g., R4 and R5) exhibit strong employment potential but experience mismatches in training alignment. In the ECS dimension, water-source protection zones (e.g., R1) face restrictions on agricultural output due to ecological regulations, whereas non-protected industrial areas (e.g., R3) are constrained by pollution pressures. In the SS dimension, urban cores (e.g., R4 and R5) demonstrate high accessibility to public services, while peripheral regions (e.g., R9) require substantial infrastructure improvements.

This analytical framework enables precise identification of regions with robust support capacity (e.g., R1 and R8) and those with evident deficiencies (e.g., R3 and R9), providing actionable insights for improving system coordination. For instance, R3 requires targeted measures in vocational training and ecological restoration, whereas R9 needs strategies to convert ecological assets into economic advantages. Consequently, region-specific and complementary interventions can be formulated to strengthen overall system-level coordination.

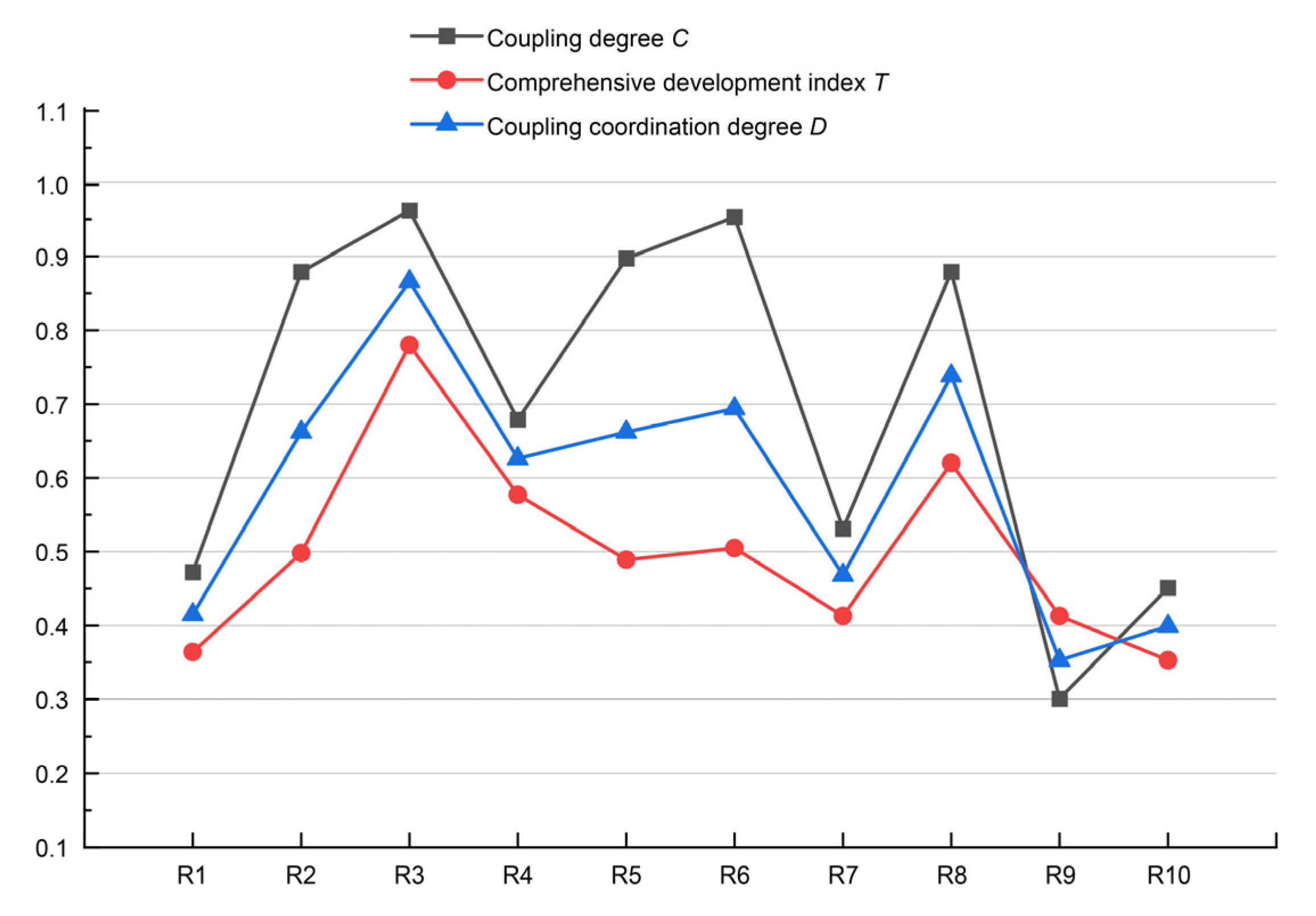

3.2.3. Internal Coupling Coordination Assessment for the Regional Development Support System

The internal coordination degree of the RDS subsystem represents the extent to which its internal indicators evolve in a balanced and mutually reinforcing way. Using the DCCM (Equations (7)–(9)), the coupling coordination degree

D was calculated among the three support dimensions, namely, ES, SS, and ECS, within the RDS system for the 10 regions. Coupling coordination grades follow the classification standards outlined in

Table 4. Results are presented in

Table 8 and visualized in

Figure 4.

The results reveal a distinct gradient of differentiation across regions. Each region’s coordination status closely corresponds to its industrial structure, policy orientation, and resource endowment—factors that collectively align with observed regional development patterns. Based on coordination levels, the regions are categorized into three groups: high coordination, medium coordination, and low coordination.

(1) High coordination areas include R1 (D = 0.921) and R8 (D = 0.894). These regions demonstrate well-balanced coordination across all three dimensions. Their development model can be characterized as a closed-loop synergy: ecological protection as the foundation, policy-driven support as the guarantee, industrial fit as the linkage, and livelihood security as the ultimate objective.

As the core resettlement area of the QC Reservoir, R1 demonstrates strong alignment between characteristic industries and its ecological base. In the social dimension, high scores in SS3 and SS2 indicate that both ecological and economic benefits are effectively transmitted to resettlers. Its leading ecological tourism industry successfully transforms natural resources such as water and cultivated land into economic value, exemplifying a typical “ecology–economy” synergy consistent with the SLF.

R8 leverages a mature eco-cultural tourism sector. Its high ES4 score, combined with leading performance in SS3 and SS4, reflects effective coordination among ecological assets, social service provision, and employment generation.

(2) Medium coordination areas include R6 (0.682), R5 (0.667), R10 (0.586), R7 (0.576), and R4 (0.561). These regions display partial coordination, wherein one dimension performs strongly while others show relative deficiencies.

R6 and R5 are primarily economy-driven regions that exhibit weaknesses in ecological coordination. In contrast, R10, R7, and R4 display relatively balanced development across the three dimensions but suffer from structural constraints such as limited industrial diversity. These regions require targeted improvements to address mismatches—particularly between economic and ecological systems, and between economic and social systems.

(3) Low coordination areas include R2 (0.421), R9 (0.264), and R3 (0.192). These regions are characterized by pronounced unidimensional weaknesses that hinder overall system interaction. R2’s petrochemical industry contributes to economic growth but imposes high ecological costs and weakens social linkages. R9, despite abundant ecological resources, faces difficulties in economic transformation and lacks adequate basic social support. R3 relies heavily on a single heavy-industry structure, with underdeveloped ecological and social support systems, resulting in a pronounced imbalance among the three dimensions. These low-coordination regions exemplify the challenges faced by economically unbalanced or geographically disadvantaged areas (e.g., mountainous regions) and call for precise, issue-oriented policy interventions.

(4) Spatial pattern of RDS coupling coordination indicates that high-coordination regions are primarily concentrated in ecological–economic transition zones (e.g., R1 and R8), whereas low-coordination regions are generally located in traditional industrial or rural agricultural areas (e.g., R3 and R9). This reflects the pattern: “ecological-priority areas coordinate strongly, traditional-industry areas coordinate weakly”. The driving mechanism underlying this pattern lies in the dynamic equilibrium among the three dimensions. In particular, ecological service supply (ECS2) and industrial employment adaptation (ES4) emerge as the key determinants of coordination levels, while SS performs a bridging function, connecting ecological and economic development with resettlers’ well-being.

3.3. Resettlers’ Livelihood Development System Analysis

3.3.1. Indicator Weight Determination for the Resettlers’ Livelihood Development System

Using field survey data from 289 sample households and expert evaluations from five domain specialists, the AHP–EW method was employed to calculate indicator weights for the RLD subsystem (

Table 9). All judgment matrices satisfied the consistency test criteria. The subjective weight distribution reflects resettlers’ primary concerns—such as income stability, employment security, and skill alignment, while the entropy-derived objective weights capture regional disparities in livelihood conditions. The resulting structure is consistent with the core logic of the SLF: FC serves as the foundation, HC functions as the driving force, NC provides supplementary support, and PC together with SC act as fundamental guarantees for sustainable livelihood development.

FC serves as the cornerstone of resettlers’ livelihood systems, with a combined weight of 0.351. Among its components, per capita annual income (FC1) holds the highest weight and demonstrates strong policy relevance. The income diversification index (FC2), weighted at 0.353, underscores the essential contribution of diversified income sources to enhancing livelihood resilience. The number of government subsidy types (FC3), with a weight of 0.271, reflects the importance of policy and financial support mechanisms in sustaining resettlers’ livelihoods. The relatively narrow income disparity among resettlers across regions indicates both Zhejiang’s advanced stage of economic development and its well-established social security network. This finding suggests that resettlement policies have successfully secured basic income levels for vulnerable groups, thereby mitigating livelihood risks associated with

HC functions as the primary driver of livelihood transformation, with a combined weight of 0.278. Within this category, the employment–industry matching degree (HC5) carries the highest weight (0.312), directly representing the degree of alignment between household labor skills and regional industrial demands. Survey respondents frequently emphasized that “job fit influences income more than formal education,” highlighting the significance of the proportion of labor with employment skills (HC4). The labor employment rate (HC3) and household labor ratio (HC2) reflect overall labor participation levels and household workforce structure. The average household education level (HC1) holds the lowest weight, as the widespread attainment of basic education in Zhejiang reduces variability. Moreover, education alone does not guarantee improved livelihoods unless it is effectively converted into employable skills aligned with local labor market requirements.

NC, with a combined weight of 0.192, emphasizes alignment with regionally characteristic agriculture. Cultivated land resources in resettlement areas are generally limited, and some households have opted for pension-insurance–based resettlement instead of land redistribution, thereby reducing dependence on cropland. The degree of match between cropping structure and characteristic agriculture (NC3) holds the highest weight (0.408), reflecting Zhejiang’s capacity to sustain specialized agricultural production despite its constrained land availability. The cultivated land quality grade (NC2) carries a greater weight than per capita cultivated land area (NC1), underscoring that land quality contributes more significantly than quantity to livelihood sustainability and agricultural productivity.

PC and SC have relatively lower combined weights—0.102 and 0.077, respectively—indicating their roles as foundational supports rather than principal drivers of livelihood development. During the resettlement process, local governments implemented multiple initiatives to facilitate social integration. Survey respondents generally expressed satisfaction with interpersonal relationships and community participation; however, they consistently emphasized that economic stability remains central to their livelihood strategies. Within these categories, per capita housing area (PC1) and community participation (SC2) hold the highest indicator weights (0.450 and 0.465, respectively), functioning as baseline guarantees that underpin broader livelihood development and social adaptation.

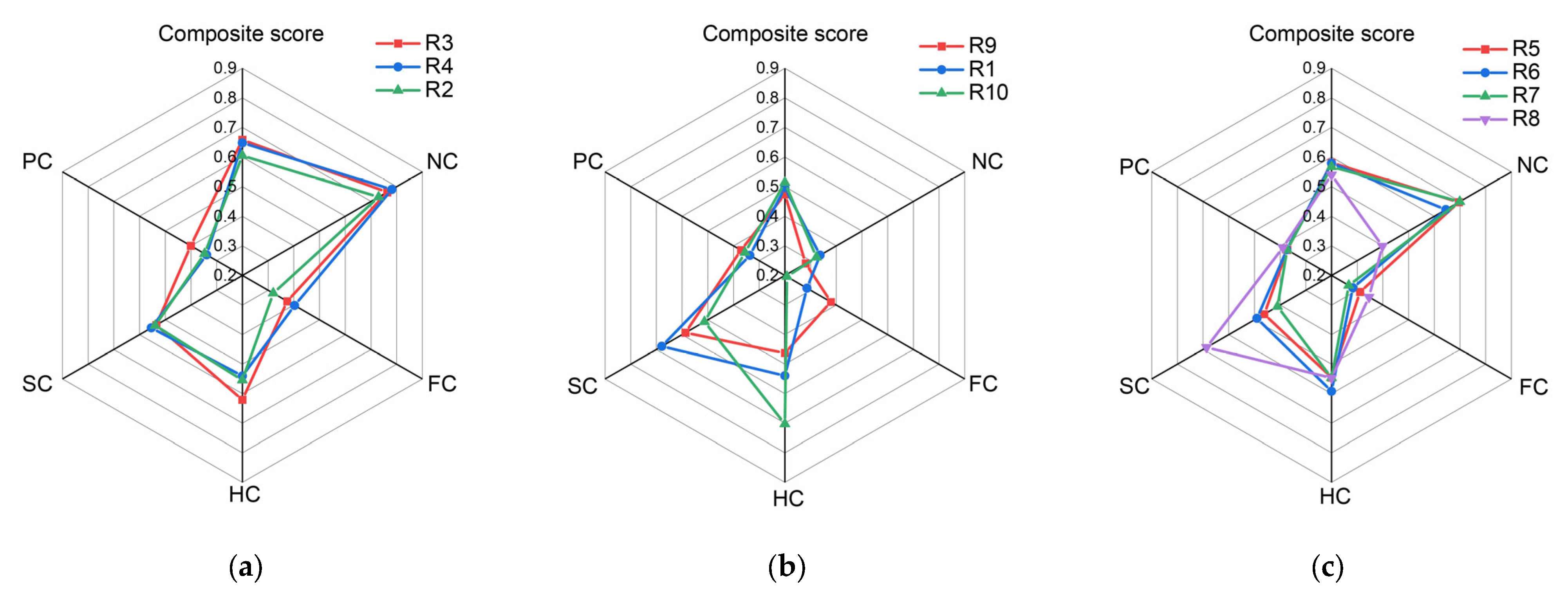

3.3.2. Livelihood Capital Evaluation

Individual indicator scores were computed for all 289 surveyed households based on the field data (

Table 3). The TOPSIS method was subsequently applied, using these indicator scores and the previously determined weights, to calculate both dimension-level scores and overall composite measurements for the RLD subsystem (

Table 10). The results reveal a distinct gradient pattern: regions with higher scores exhibit well-balanced livelihood capital structures, whereas low-scoring areas display pronounced deficiencies in one or more forms of capital accumulation.

High-score regions include R3 (0.658), R4 (0.648), and R2 (0.605). These regions exhibit well-balanced livelihood capital portfolios, each displaying notable strengths in one or more dimensions (

Figure 5a). R3 resettlers benefit from robust HC, supported by high-skilled employment opportunities within the port industry. Correspondingly, HC and PC scores are the highest, reflecting the advantages of an industrialized urban environment that features stable employment and well-developed infrastructure. In R4, the modern service economy contributes to income stability, with resettlers achieving strong performance across NC, FC, and SC—demonstrating the advantages of diversified urban settings. R2’s petrochemical industry provides steady employment and consistent support across all capital types, with no significant deficiencies observed in its livelihood structure.

Low-score regions include R9 (0.474), R1 (0.496), and R10 (0.514), all of which exhibit multidimensional constraints (

Figure 5b). R9 records the lowest scores in HC and NC due to slow agricultural transformation, limited industrial capacity, weak employment opportunities, and poor skill alignment. In R1, resettlers face restrictions imposed by water-source protection regulations and are confined to cultivating “suitable” crops such as rice and legumes, thereby reducing returns on NC. Many resettlers retained their previous employment modes because of intra-county relocation, resulting in path dependency that suppresses FC scores. R10 reveals a mismatch between HC and FC—low income levels and limited income diversification stem from the volatility of local fisheries and the absence of robust alternative industries.

Medium-score regions, including R5 (0.581), R6 (0.579), R7 (0.567), and R8 (0.540), show moderate performance without pronounced strengths or critical weaknesses (

Figure 5c). R5’s commercial-urban context yields balanced yet undifferentiated livelihood capitals. R6 resettlers exhibit sufficient industrial skills but limited income diversification. R7 possesses strong agricultural potential yet weak community integration. R8 demonstrates strong social support, but its agricultural adaptation capacity for resettlers remains underdeveloped.

Analysis by capital dimension confirms consistency with observed regional realities. In FC, urban centers (e.g., R4) attain higher scores, whereas agricultural regions (e.g., R7) face greater income risks due to industrial concentration. In HC, industrialized areas (e.g., R3) display superior skill alignment, while rural zones (e.g., R9) experience lower employment rates. In NC, water-source protection regions (e.g., R1) are notably constrained by environmental regulations. For PC and SC, urban localities (e.g., R4) benefit from improved housing conditions and greater social participation, whereas peripheral regions (e.g., R10) face limitations in basic support infrastructure.

Overall, these results highlight significant spatial heterogeneity in resettlers’ livelihood capitals and provide an empirical foundation for differentiated policy interventions. For instance, R9 would benefit from enhanced vocational training to strengthen skill adaptability, while R10 requires expanded non-farm employment opportunities to stabilize household income and mitigate livelihood vulnerability.

3.3.3. Internal Coupling Coordination Assessment for the Resettlers’ Livelihood Development System

The internal coordination degree of the RLD subsystem reflects the extent to which its livelihood-related indicators evolve coherently and structurally reinforce one another. Using the DCCM, the coupling and coordination relationships among the five livelihood capitals within the RLD subsystem were computed to evaluate each region’s efficiency in resource allocation and overall system order. The classification of coupling coordination grades follows the criteria outlined in

Table 4, while the corresponding results are summarized in

Table 11 and illustrated in

Figure 6.

The results indicate substantial variation in coupling coordination levels across regions, reflecting how effectively resettlers’ livelihood capital structures align with regional industrial demands. Overall, the observed patterns correspond closely with the distinctive livelihood characteristics of local resettlers. For analytical clarity, the regions are classified into three coordination categories—high, medium, and low—based on their coupling coordination degrees.

(1) High-coordination area: Only R3 qualifies as a high-coordination region (D = 0.866). Its defining feature is the strong interaction and synergy among all five forms of livelihood capital. Resettlers in R3 actively utilize local economic opportunities and have successfully adapted to new production and living environments. The high score for employment–industry matching degree (HC5) drives the accumulation of FC and reinforces PC. This dynamic creates a virtuous cycle characterized by deep coupling between human and financial capital, strong physical capital, and well-developed SC. These mutually reinforcing relationships result in a highly efficient and well-integrated livelihood system.

(2) Medium-coordination areas: R8 (D = 0.738), R6 (D = 0.694), R2 (D = 0.662), R5 (D = 0.662), and R4 (D = 0.626) fall within the medium-coordination category. These regions maintain relatively balanced livelihood capital structures that correspond to local development contexts, though none exhibit dominance in a single capital dimension.

In R8, R5, and R4, SC plays a pivotal role. Their tertiary-sector–based economies foster balanced interactions among the various capitals, producing moderate synergies between NC and FC. However, limited agricultural adaptability constrains further capital enhancement. R6 and R2 demonstrate strong integration between regional industrial development and livelihood capital formation. In both regions, HC and FC align effectively with local employment structures, though income diversification remains modest. These areas would benefit from policies that enhance cross-capital complementarities and mitigate reliance on single-dimensional growth.

(3) Low-coordination areas: R7 (D = 0.468), R1 (D = 0.415), R10 (D = 0.399), and R9 (D = 0.353) are identified as low-coordination regions. These areas experience significant deficits in one or more livelihood capitals, which hinder capital interaction and impede the formation of a self-reinforcing livelihood system.

In R7, ongoing industrial upgrading in mold manufacturing has resulted in skill mismatches and shortages in financial ad social capital. In R1, watershed protection policies constrain agricultural income, while path dependency in employment limits the compensatory roles of social and human capital in offsetting deficiencies in FC. R10, influenced by volatility in the fisheries sector, experiences unstable income and difficulty converting human capital into financial returns. R9, a mountainous agricultural county, suffers from limited arable land and underdeveloped human capital, leading to concurrent weaknesses in both natural and human capital dimensions. These regions require tailored policy interventions—such as programs for mitigating skill mismatches, promoting non-farm employment, and implementing ecological compensation mechanisms—to address localized vulnerabilities.

(4) Spatial pattern and mechanism: The gradient pattern of coupling coordination within the RLD system exhibits a clear spatial hierarchy: urban and industrially advanced regions > traditional agricultural regions > mountainous regions. The primary mechanism driving this differentiation lies in the dynamic balancing capacity among the five livelihood capitals. HC and FC—particularly HC5 and FC2—are the dominant determinants of coupling strength, while NC and SC serve complementary roles. Nevertheless, weak industrial alignment or stringent ecological constraints can create structural bottlenecks, disrupting overall system integration and limiting sustainable livelihood transformation.

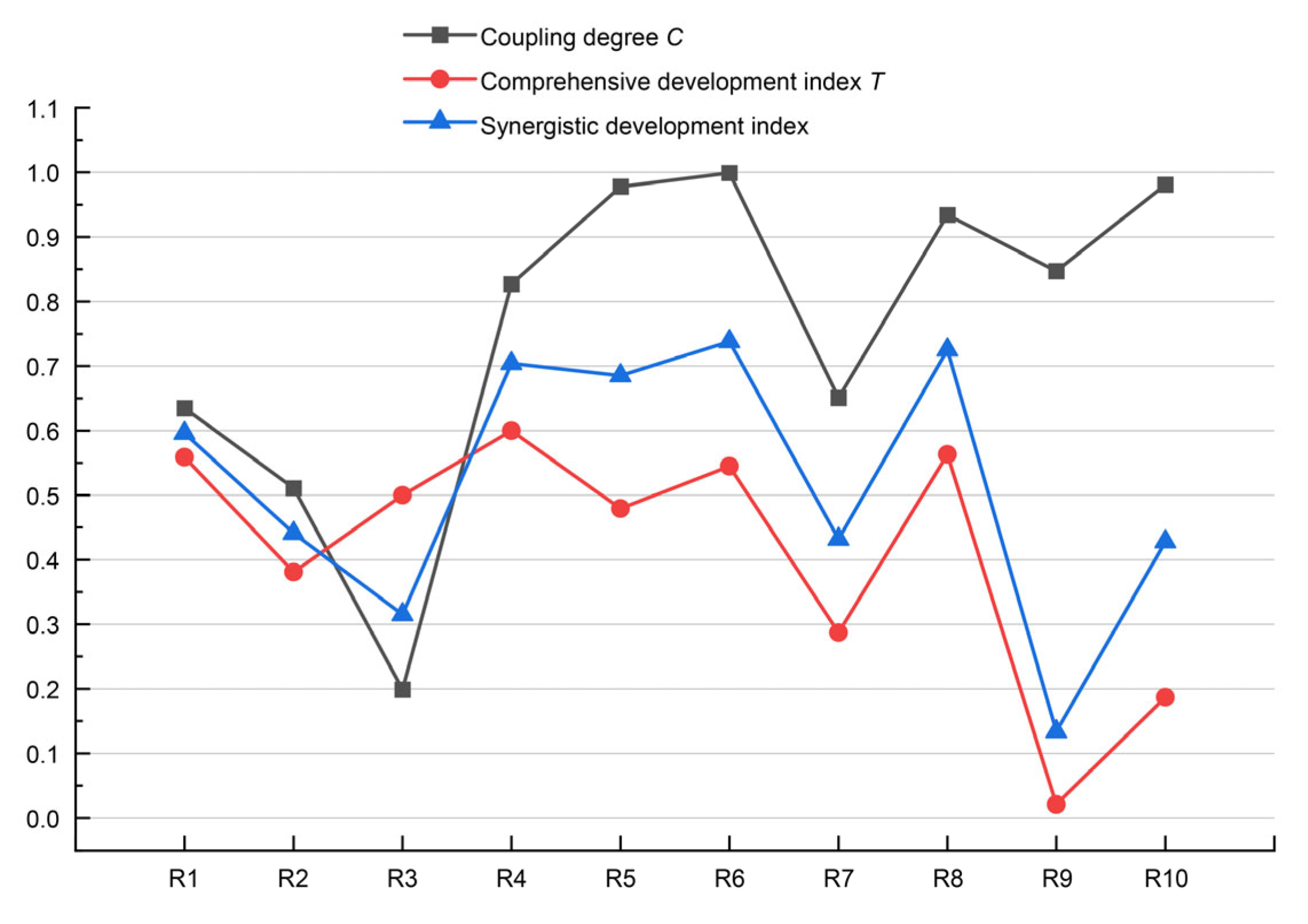

3.4. Analysis of the Synergistic Development Index

Building on the development levels of RDS and RLD discussed in

Section 3.2, along with their internal coordination analyzed in

Section 3.3, this section employs the DCCM to calculate the SDI. The SDI quantitatively measures the degree of synergy between resettlers’ livelihood development and regional development. A higher SDI value indicates a more balanced and mutually reinforcing relationship between the two subsystems, reflecting a healthier bidirectional dynamic of “livelihood improvement supported by regional development and regional progress driven by livelihood enhancement”. Classification grades are consistent with those presented in

Table 4, while the calculated results are summarized in

Table 12 and visualized in

Figure 7.

The SDI reveals a distinct gradient across the ten regions, illustrating the varying degrees of alignment between resettlers’ livelihood needs and the developmental capacities of their host regions. Fundamentally, the SDI captures the efficiency of bidirectional interactions—that is, the extent to which the regional support system can effectively provide resources to the livelihood system, and whether the livelihood system can, in turn, generate feedback that strengthens regional development. Considering each region’s industrial structure, resource endowment, and resettler characteristics, the regions are categorized into four synergy types: Benign Synergy, Region-driven, Unipolar Constraint, and Dual-weak Lock-in. The distribution of the SDI is shown in

Figure 8.

(1) Benign Synergy type includes R6 (SDI = 0.738), R8 (SDI = 0.725), and R4 (SDI = 0.704). These regions demonstrate strong interaction between the two subsystems (high C) and relatively high overall development levels (high T). The defining feature of this type is reciprocal empowerment between the regional support system and resettlers’ livelihood system, forming a positive feedback loop in which regional development generates livelihood opportunities, and livelihood advancement, in turn, reinforces local economic growth. Coordination mechanisms in these regions are both mature and effective, promoting sustainable, high-level development.

R6 records the highest SDI, primarily due to elevated scores in ES4 and HC5, representing strong employment absorption by characteristic industries and a high degree of labor–industry matching. These two key indicators establish a virtuous cycle of industrial drive → skill supply → income growth → consumption feedback, reinforcing long-term system stability. R8 successfully transforms ecological assets into economic momentum through its mature eco-cultural tourism sector. High employment absorption among resettlers strengthens FC accumulation, achieving a balanced outcome that combines ecological conservation with livelihood improvement—a clear demonstration of “green synergy” between environment and development.

(2) Region-driven type includes R5 (SDI = 0.685) and R1 (SDI = 0.596). These regions feature a strong RDS system that drives the RLD subsystem forward. However, internal weaknesses within the livelihood system constrain overall synergy. To achieve higher coordination, these regions must enhance the transmission efficiency through which regional advantages translate into direct livelihood improvements for resettlers.

R5 is a traditional commercial hub, and benefits from well-developed regional infrastructure and service systems. Nevertheless, persistent skill mismatches among resettlers weaken employment alignment, thereby reducing the effectiveness of converting economic advantages into tangible livelihood outcomes.

R1 serving as the core watershed protection area, attains the highest RDS composite score (0.852) due to strong policy support in ecological services and public infrastructure. However, RLD performance remains limited. Strict environmental regulations—such as prohibitions on polluting industries within ecological redline zones—curtail productive activities and disrupt the balance between NC and local economic demand. This results in a “high support–low livelihood” configuration, where resettlers’ developmental potential and self-driven initiative are insufficiently activated.

(3) Unipolar Constraint type includes R2 (SDI = 0.441), R7 (SDI = 0.432), and R10 (SDI = 0.428). In these regions, substantial deficiencies in one subsystem suppress overall coordination, necessitating targeted interventions to alleviate single-dimension bottlenecks.

In R2, the petrochemical industry drives regional economic development but simultaneously exerts severe ecological pressure, forming an “ecological constraint synergy” pattern where industrial growth conflicts with environmental sustainability. R7 is currently undergoing industrial upgrading toward research and high-tech sectors; however, the resettlers’ livelihood system lacks the requisite HC to adapt. Skill mismatches between existing labor capacity and emerging industrial demands significantly hinder coordinated progress.

(4) Dual-weak Lock-in type includes R3 (SDI = 0.315) and R9 (SDI = 0.134). These regions experience concurrent weaknesses in both the RDS and RLD subsystems, resulting in minimal interaction and entrapment in a low-level development loop. Achieving coordination in such contexts requires comprehensive structural transformation.

R3’s dependence on heavy industry has led to ecological degradation and underdeveloped social infrastructure. Although the RLD subsystem performs moderately, resettlers’ labor participation and consumption contribute little to regional development, producing a fragmented structure characterized by an “independent support system and self-contained livelihood system”. This disconnection prevents genuine synergy between the two subsystems. R9, as a mountainous agricultural county, lacks both economic and social infrastructure, and its RLD score is the lowest among all regions, resulting in a pronounced dual-weak lock-in condition.

(5) From the typological analysis, Benign Synergy regions should focus on consolidating their multidimensional advantages to sustain high-level coordination. Region-driven areas must strengthen mechanisms that effectively translate regional development potential into tangible livelihood improvements. Unipolar Constraint regions require targeted policy interventions to alleviate subsystem bottlenecks and restore balance. Dual-weak Lock-in regions, by contrast, demand fundamental structural reform and the simultaneous empowerment of both subsystems to break out of low-level equilibrium traps.

The core determinant of SDI performance lies in the strength of supply–demand alignment between the two systems. Specifically, HC5 (employment–industry matching degree) and ES4 (employment absorption by characteristic industries) function as the principal drivers of synergy, fostering mutual reinforcement between labor capacity and industrial demand. ECS2 (ecological service supply) and FC2 (income diversity index) act as modulators that can either constrain or amplify synergy, depending on local environmental and economic contexts. Collectively, these findings offer robust empirical evidence to guide differentiated and precision-targeted policy strategies aimed at improving the sustainability and effectiveness of resettlement outcomes.

3.5. Spatial Correlation Analysis of the SDI

To examine the spatial association of the SDI across the ten regions, Moran’s I was calculated to evaluate both global and local spatial correlations (using Equations (10) and (11)). This analysis identifies patterns of geographic clustering or dispersion in county-level coordination performance. The results reveal a spatial configuration characterized as “weakly dispersed distribution with heterogeneous local associations”. While global spatial dependence is not statistically significant, localized clustering and dispersion patterns are evident. These findings indicate that variations in industrial structure and resource flows play a critical role in shaping the spatial differentiation of coordination levels among regions.

3.5.1. Global Spatial Correlation Analysis

Global Moran’s I measures the overall spatial dependence of a regional variable. For the SDI, the global Moran’s I is , with a theoretical expectation E(I) = −0.111, Z = 0.135, and p = 0.446. These values indicate that the overall SDI distribution across the 10 regions follows a “weakly dispersed” pattern, which is not statistically significant.

This weak spatial dispersion primarily results from the pronounced heterogeneity in industrial structures among regions. Central urban areas (e.g., R4 and R5) are dominated by service-oriented industries, coastal industrial zones (e.g., R3 and R2) display heavy industrial activity, and ecological regions (e.g., R1 and R10) emphasize agriculture and eco-tourism. Such industrial differentiation disrupts the conventional expectation that geographically adjacent regions should display similar levels of coordination. In addition, the randomized resettlement process—where resettlers are allocated to relocation sites through a lottery mechanism—introduces heterogeneity in skill composition and livelihood capacity, thereby weakening patterns of global spatial clustering.

3.5.2. Local Spatial Correlation Analysis

Local Moran’s I identifies spatial association patterns between each region and its immediate neighbors. The sign of

indicates clustering or dispersion, and significance is determined by the

Z-score and

p-value. Results are presented in

Table 13. Based on significance and direction, local spatial associations are categorized into Significant-association, Marginal-association, and Weak-association types.

(1) Significant-association type (p < 0.05) includes R4 and R7, which represent opposite spatial patterns—clustering and dispersion—and serve as illustrative typological examples.

R4 shows significant clustering (). It forms a “high–high” cluster with neighboring R5 and R8. This is driven by strong industrial complementarity: R4’s modern service economy complements R5’s commercial sector and R8’s eco-tourism, while interconnected public services enhance regional cohesion.

R7 exhibits significant dispersion (), forming a “low–high” contrast with higher-performing neighbors like R6 and R4. R7 is in industrial transition (from mold manufacturing to tech-intensive sectors), but resettler skills and social adaptability lag, creating a coordination gap.

(2) Marginal-association type (p < 0.1) includes R5 and R10, where spatial clustering is evident but not statistically strong due to weaker underlying foundations.

R5 marginally clusters with R4 and R8 in a “high–high” configuration, enabled by commercial complementarities and frequent regional interaction. However, resettler–industry mismatch weakens overall livelihood linkages.

R10 forms a marginal “low–low” cluster with adjacent R9. Both regions lack industrial depth and have limited resource circulation, reinforcing their low-coordination status.

(3) Weak-association type (p ≥ 0.1) includes the remaining six regions, namely, R6, R8, R1, R2, R3, and R9, none of which show statistically significant spatial correlation. This reflects industrial heterogeneity and isolated development dynamics.

The root causes of the weak spatial association observed among these regions stem from several structural factors: industrial mismatches (e.g., R3’s heavy-industrial orientation contrasted with neighboring service-based economies), ecological constraints (e.g., R1’s stringent water-source protection policies that restrict cross-regional coordination), and geographic or administrative isolation (e.g., R9’s mountainous terrain limiting interregional connectivity). In such contexts, the interaction between livelihood and support systems tends to be self-contained or structurally fragmented, thereby reducing spatial regularity and impeding the diffusion of synergistic development effects across adjacent regions.

(4) Implications: The spatial differentiation of SDI is not solely determined by geographic proximity but emerges from a complex interaction among industrial specialization, policy alignment, and livelihood–system compatibility. Regions with homogeneous or complementary industrial structures (e.g., R4–R5–R8) tend to form spatial clusters, while heterogeneous regions (e.g., R7 versus R6) exhibit spatial dispersion due to mismatches in industrial orientation or disparities in resettler capacity. Public service interconnectivity strengthens spatial cohesion and regional “stickiness” (e.g., R4 and its neighboring areas), whereas administrative fragmentation or geophysical isolation (e.g., R10) weakens spatial linkages.

To promote spatially balanced development, it is essential to dismantle administrative barriers, enhance industrial integration, improve cross-regional resource circulation, and prevent the emergence of “islanded” or fragmented development zones. These findings offer a solid empirical basis for formulating cross-regional coordination and support mechanisms in future reservoir resettlement planning and implementation.