Isolation and Identification of Pseudoalteromonas agarivorans LJ53, a Pathogenic Bacterium Causing Bleaching Disease in Saccharina japonica

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Bacterial Isolation

2.3. Re-Infection Assay

2.4. Observations of Ultrastructural Changes in the Infected Sporelings Using Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM)

2.5. Morphological Observation of the Pathogenic Bacterial Strain

2.6. Molecular Identification

2.7. Microbial Community Profiling Analysis

3. Results

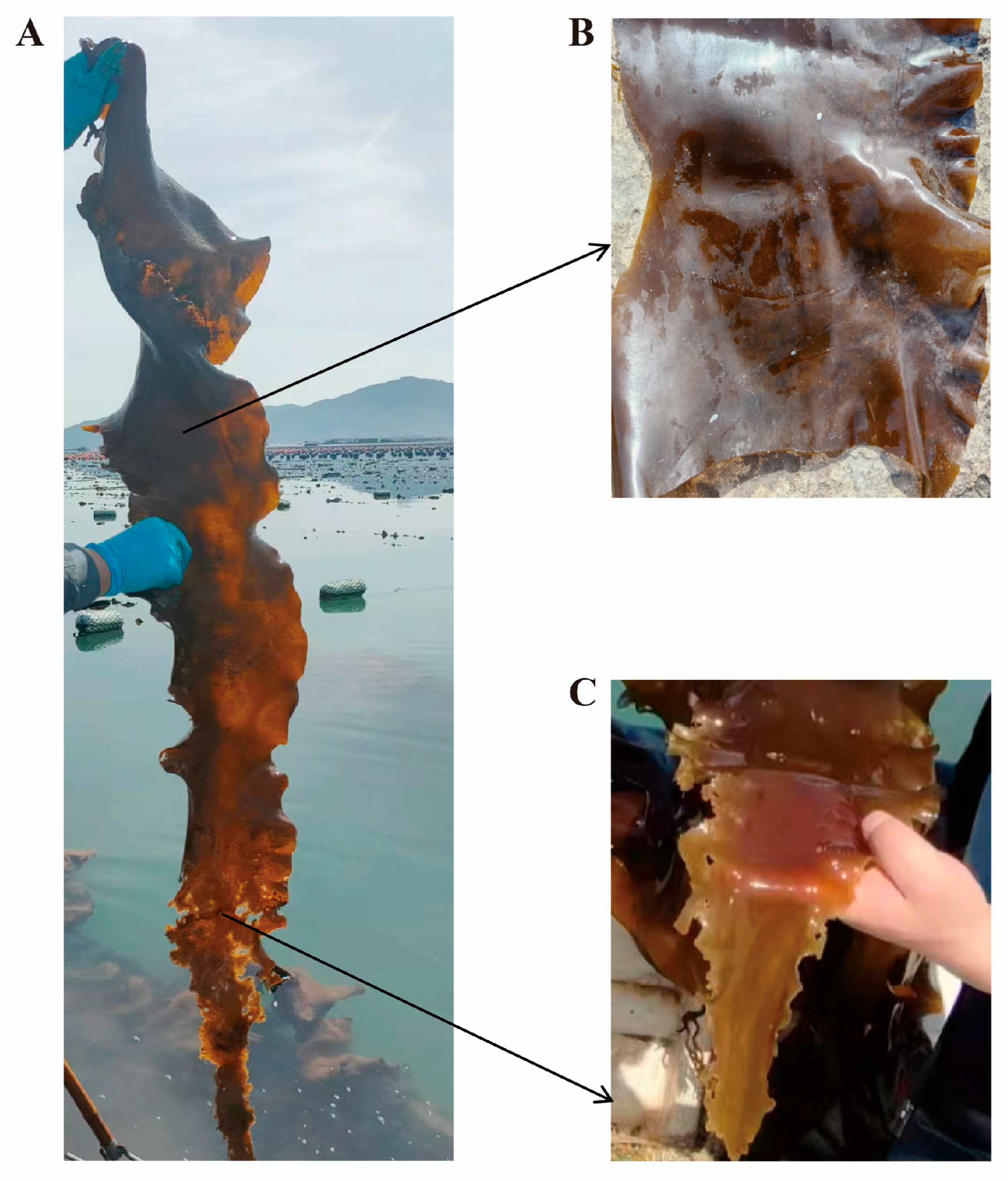

3.1. Isolation of Pathogenic Bacteria and Re-Infection Assay

3.2. Observations of TEM of Infected Tissue by Strain LJ53

3.3. Morphological Characteristics and Molecular Identification of Strain LJ53

3.4. Ecological Insights from Metagenomic Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wenning, R. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture (sofia) 2020 report. Integr. Environ. Asses. 2020, 16, 800–801. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Lu, B.; Shuai, L.; Li, D.; Zhang, R. Microbial diseases of nursery and field-cultivated Saccharina japonica (Phaeophyta) in China. Arch Hydrobiol. Suppl. Algol. Stud. 2014, 145, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppin, R.; Rautenbach, C.; Smit, A.J. Individual-based numerical experiment to describe the distribution of floating kelp within the Southern Benguela Upwelling System. Bot. Mar. 2024, 67, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, C.; Thomas, T.; Lewis, M.; Steinberg, P.; Kjelleberg, S. Composition, uniqueness and variability of the epiphytic bacterial community of the green alga Ulva australis. ISME J. 2011, 5, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemay, M.A.; Chen, M.L.Y.; Mazel, F.; Hind, K.R.; Starko, S.; Keeling, P.J.; Martone, P.T.; Parfrey, L.W. Morphological complexity affects the diversity of marine microbiomes. ISME J. 2021, 15, 1372–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, K.; Joint, I.; Callow, M.E.; Callow, J.A. Effect of marine bacterial isolates on the growth and morphology of axenic plantlets of the green alga Ulva linza. Microb. Ecol. 2006, 52, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel, B.L.; Miranda, K.K.; Fogarty, E.C.; Watson, A.R.; Pfister, C.A. Functional Insights into the Kelp Microbiome from Metagenome-Assembled Genomes. mSystems 2022, 7, e01422-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adouane, E.; Hubas, C.; Leblanc, C.; Lami, R.; Prado, S. Multi-omics analysis of the correlation between surface microbiome and metabolome in Saccharina latissima (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae). FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2025, 101, fiae160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelps, C.M.; McMahon, K.; Bissett, A.; Bernasconi, R.; Steinberg, P.D.; Thomas, T.; Marzinelli, E.M.; Huggett, M.J. The surface bacterial community of an Australian kelp shows cross-continental variation and relative stability within regions. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2021, 97, fiab089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Nair, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, H.; Lu, L.; Chang, L.; Jiao, N. Adverse Environmental Perturbations May Threaten Kelp Farming Sustainability by Exacerbating Enterobacterales Diseases. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 5796–5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Chen, Y.; Saha, M.; Zhuang, Y.R.; Chang, L.R.; Xiao, L.Y.; Wang, G.G. Pseudoalteromonas piscicida X-8 causes bleaching disease in farmed Saccharina japonica. Aquaculture 2022, 546, 737354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.Y.; Zhuang, Y.R.; Chang, L.R.; Xiao, L.Y.; Lin, Q.; Qiu, Q.Y.; Chen, D.F.; Egan, S.; Wang, G.G. Naturally occurring beneficial bacteria Vibrio alginolyticus X-2 protects seaweed from bleaching disease. mBio 2023, 14, e00065-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.W.; Yan, X.Y.; Xiao, J.L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, M.H.; Jin, J.Y.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liao, Z.Y.; Chen, Q. Isolation, identification, and whole genome sequence analysis of the alginate-degrading bacterium Cobetia sp. cqz5-12. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppenheimer, C.H.; Zobell, C.E. The growth and viability of 63 species of marine bacteria as influenced by hydrostatic pressure. J. Mar. Res. 1952, 11, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sanger, F.; Nicklen, S.; Coulson, A.R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 5463–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.Y.Z.; Bekhet, G. First isolation and characterization of the pathogenic Aeromonas veronii bv. veronii associated with ulcerative syndrome in the indigenous Pelophylax ridibundus of Al-Ahsaa, Saudi Arabia. Microb. Pathogen. 2018, 117, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11 Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method—A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Liu, C.M.; Luo, R.; Sadakane, K.; Lam, T.W. MEGAHIT: An ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1674–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E.; Lu, J.; Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Breitwieser, F.P.; Thielen, P.; Salzberg, S.L. Bracken: Estimating species abundance in metagenomics data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2017, 3, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chang, L.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, X.; Han, Q.; Li, N.; Egan, S.; Wang, G. Diversity of the epiphytic bacterial communities associated with commercially cultivated healthy and diseased Saccharina japonica during the harvest season. J. Appl. Phycol. 2020, 32, 2071–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pang, S.; Shan, T.; Su, L. Changes of microbial community structures associated with seedlings of Saccharina japonica at early stage of outbreak of green rotten disease. J. Appl. Phycol. 2020, 32, 1323–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, L.; Baumann, P.; Mandel, M.; Allen, R.D. Taxonomy of aerobic marine eubacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1972, 110, 402–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanenko, L.A.; Zhukova, N.V.; Rohde, M.; Lysenko, A.M.; Mikhailov, V.V.; Stackebrandt, E. Pseudoalteromonas agarivorans sp. nov., a novel marine agarolytic bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micr. 2003, 53, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, G.; Gauthier, M.; Christen, R. Phylogenetic analysis of the genera alteromonas, Shewanella, and moritella using genes-coding for small-subunit ribosomal-rna sequences and division of the genus alteromonas into 2 genera, Alteromonas (emended) and Pseudoalteromonas gen-nov, and proposal of 12 new species combinations. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1995, 45, 755–761. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Lan, X.; Zhou, M.; Chen, X.; Jin, J.; Zhu, S.; Yang, J.; Chen, J. Genome sequencing and comparative genomic analysis of Pseudoalteromonas arabiensis N1230-9 isolated from the surface seawater of the Pacific Ocean. Weishengwu Xuebao 2024, 64, 1691–1703. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Liang, S.; Chu, C.; Han, X. The influence of biosurfactant on the growth of Prorocentrum donghaiense. China Environ. Sci. 2004, 24, 692–696. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Lin, Z.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Zhou, J.; Guan, M.; Zhou, J. Facilitating harmful algae removal in fresh water via joint effects of multi-species algicidal bacteria. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, R.P.; Lu, X.W.; Li, X.N.; Pu, Y.P. Biological degradation of algae and microcystins by microbial enrichment on artificial media. Eco. Eng. 2009, 35, 1584–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.J.; Weeks, O.B.; Colwell, R.R. Taxonomy of pseudomonas piscicida (bein) buck meyers and leifson. J. Bacteriol. 1965, 89, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Choudhury, J.D.; Gachhui, R.; Mukherjee, J. A new collagenase enzyme of the marine sponge pathogen Pseudoalteromonas agarivorans NW4327 is uniquely linked with a TonB dependent receptor. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 109, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.H.; Zhang, X.D.; Zhang, X.R.; Wang, X.F.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Xu, F. Direct preparation of alginate oligosaccharides from brown algae by an algae-decomposing alginate lyase alyp18 from the marine bacterium Pseudoalteromonas agarivorans A3. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussin-Léveillée, C.; St-Amand, M.; Desbiens-Fortin, P.; Perreault, R.; Pelletier, A.; Gauthier, S.; Gaudreault-Lafleur, F.; Laforest-Lapointe, I.; Moffett, P. Co-occurrence of chloroplastic ROS production and salicylic acid induction in plant immunity. New Phytol. 2025, 248, 1989–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.G.; Li, X.Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, S.W.; Jing, B.Y.; Hu, C.Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Zhou, Y.H.; Yu, J.Q.; Hu, Z.J. ERF.D2 negatively controls drought tolerance through synergistic regulation of abscisic acid and jasmonic acid in tomato. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 3363–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.F.; Bai, X.L.; Jiao, S.; Li, Y.M.; Li, P.R.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wei, G.H. A simplified synthetic community rescues Astragalus mongholicus from root rot disease by activating plant-induced systemic resistance. Microbiome 2021, 9, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.H.; Wang, W.H.; Zhang, S.K.; Chen, J.H.; Wu, J.S. Soil pH and potassium drive root rot in Torreya grandis via direct modulation and microbial taxa-mediated pathways. Ind. Crop Prod. 2025, 228, 120940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Qin, P.; Lu, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, A.; Cao, Y.; Ding, W.; Zhang, W. Bioprospecting of culturable marine biofilm bacteria for novel antimicrobial peptides. Imeta 2024, 3, e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Ye, T.; Li, C.; Praveen, P.; Hu, Z.; Li, W.; Shang, C. Embracing the era of antimicrobial peptides with marine organisms. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2024, 41, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Chen, Q.; Chen, S.; Xu, B.; Ju, J.; Wang, H. Mathermycin, a lantibiotic from the marine actinomycete Marinactinospora thermotolerans SCSIO 00652. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e00926-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ouyang, Y.; Tu, R.; Li, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhong, C.; Fu, L.; Li, J. Isolation and Identification of Pseudoalteromonas agarivorans LJ53, a Pathogenic Bacterium Causing Bleaching Disease in Saccharina japonica. Water 2026, 18, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010066

Ouyang Y, Tu R, Li J, Zhou X, Zhong C, Fu L, Li J. Isolation and Identification of Pseudoalteromonas agarivorans LJ53, a Pathogenic Bacterium Causing Bleaching Disease in Saccharina japonica. Water. 2026; 18(1):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010066

Chicago/Turabian StyleOuyang, Ying, Ruojing Tu, Jiapeng Li, Xianzhen Zhou, Chenhui Zhong, Lijun Fu, and Jiangwei Li. 2026. "Isolation and Identification of Pseudoalteromonas agarivorans LJ53, a Pathogenic Bacterium Causing Bleaching Disease in Saccharina japonica" Water 18, no. 1: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010066

APA StyleOuyang, Y., Tu, R., Li, J., Zhou, X., Zhong, C., Fu, L., & Li, J. (2026). Isolation and Identification of Pseudoalteromonas agarivorans LJ53, a Pathogenic Bacterium Causing Bleaching Disease in Saccharina japonica. Water, 18(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010066