Conjunctive-Use Frameworks Driven by Surface Water Operations: Integrating Concentrated and Distributed Strategies for Groundwater Recharge and Extraction

Abstract

1. Introduction

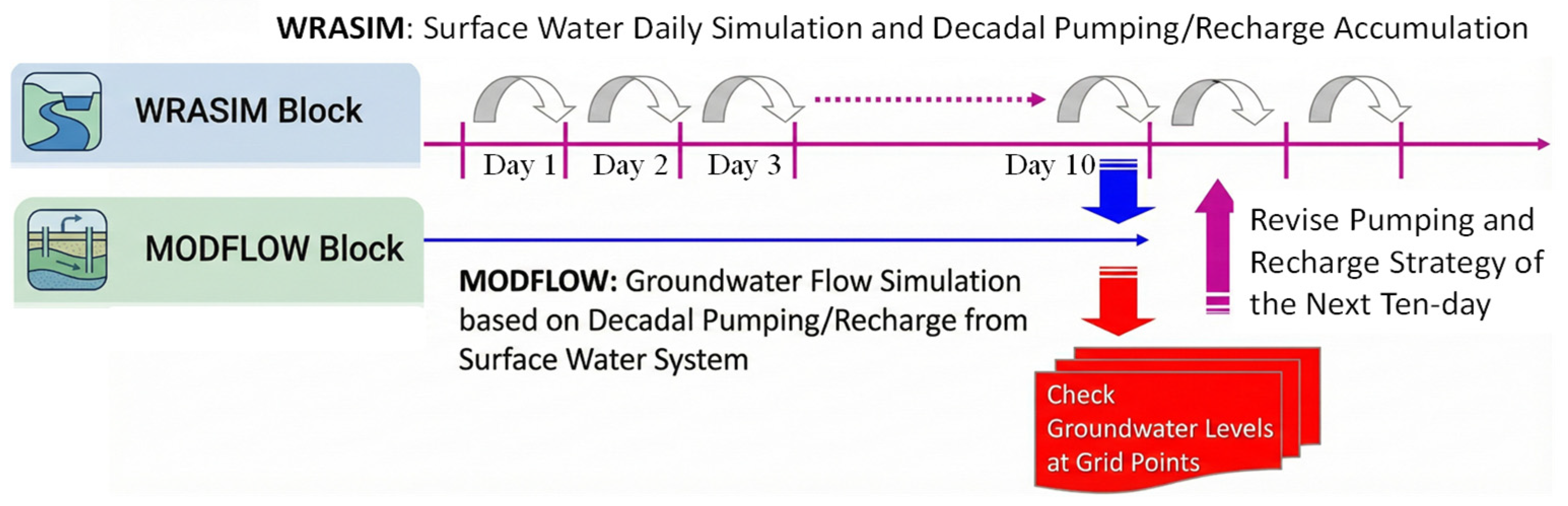

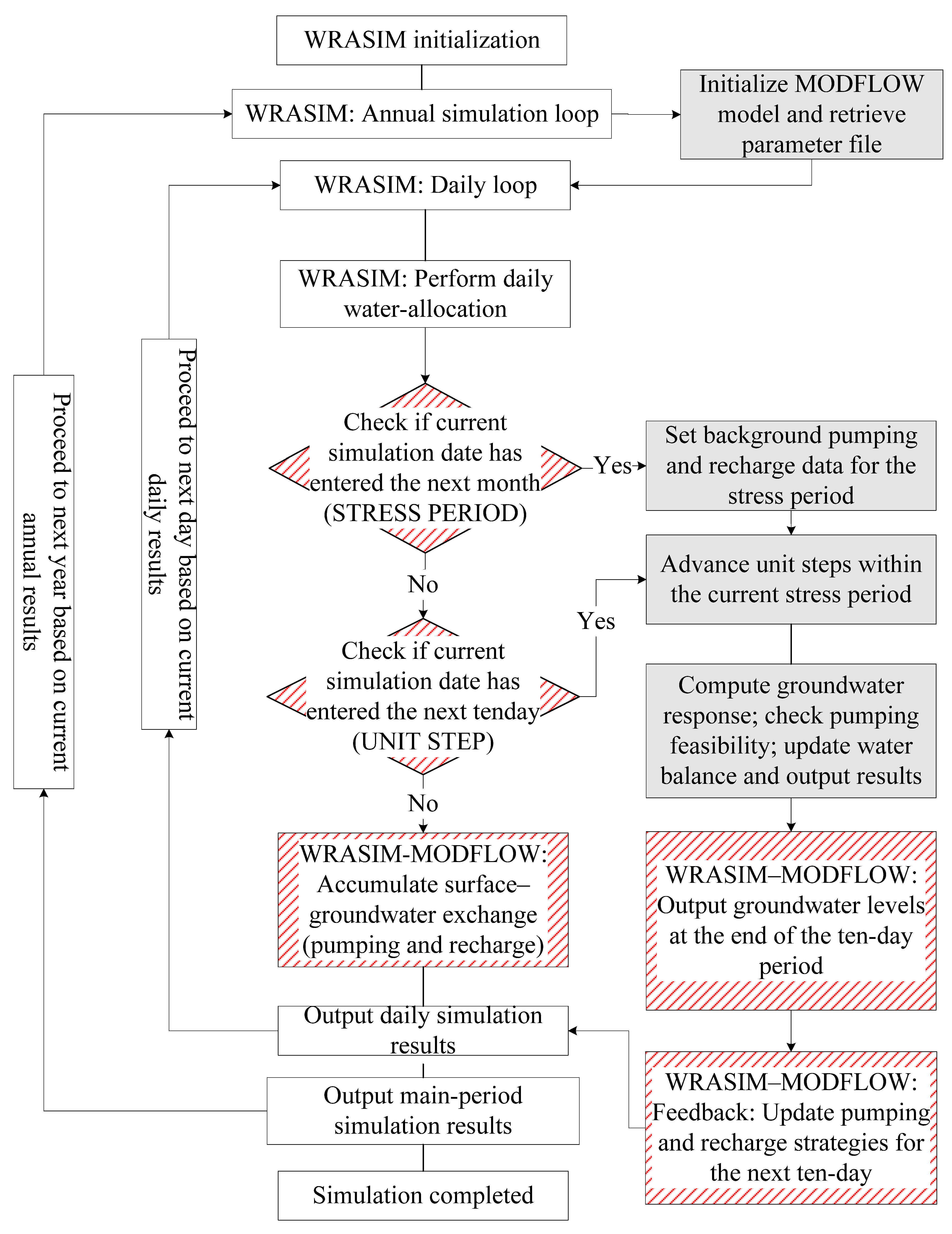

- Cross-timescale coordination. Because groundwater responds more slowly than surface water, the two subsystems are simulated in management-consistent time steps: daily for surface water allocation and at ten-day intervals for groundwater dynamics. Daily surface water operations determine the pumping and recharge decisions for each ten-day period, after which the groundwater model simulates the corresponding water-level responses and feeds them back to guide the next surface water operation cycle.

- Surface water-driven pumping and recharge rules. Pumping and recharge are activated based on operational conditions within the surface water system, such as the availability of surplus flows, reservoir storage exceeding rule curves, or unmet demand surpassing specified thresholds. This structure reflects realistic operational flexibility and priority-based decision-making in multi-source water supply systems.

- Explicit incorporation of groundwater-level constraints. The framework integrates the OGLR that restricts pumping or recharge when groundwater levels fall below or exceed designated thresholds. This mechanism ensures that conjunctive-use strategies remain consistent with long-term aquifer safety and practical management considerations.

2. Materials and Methods

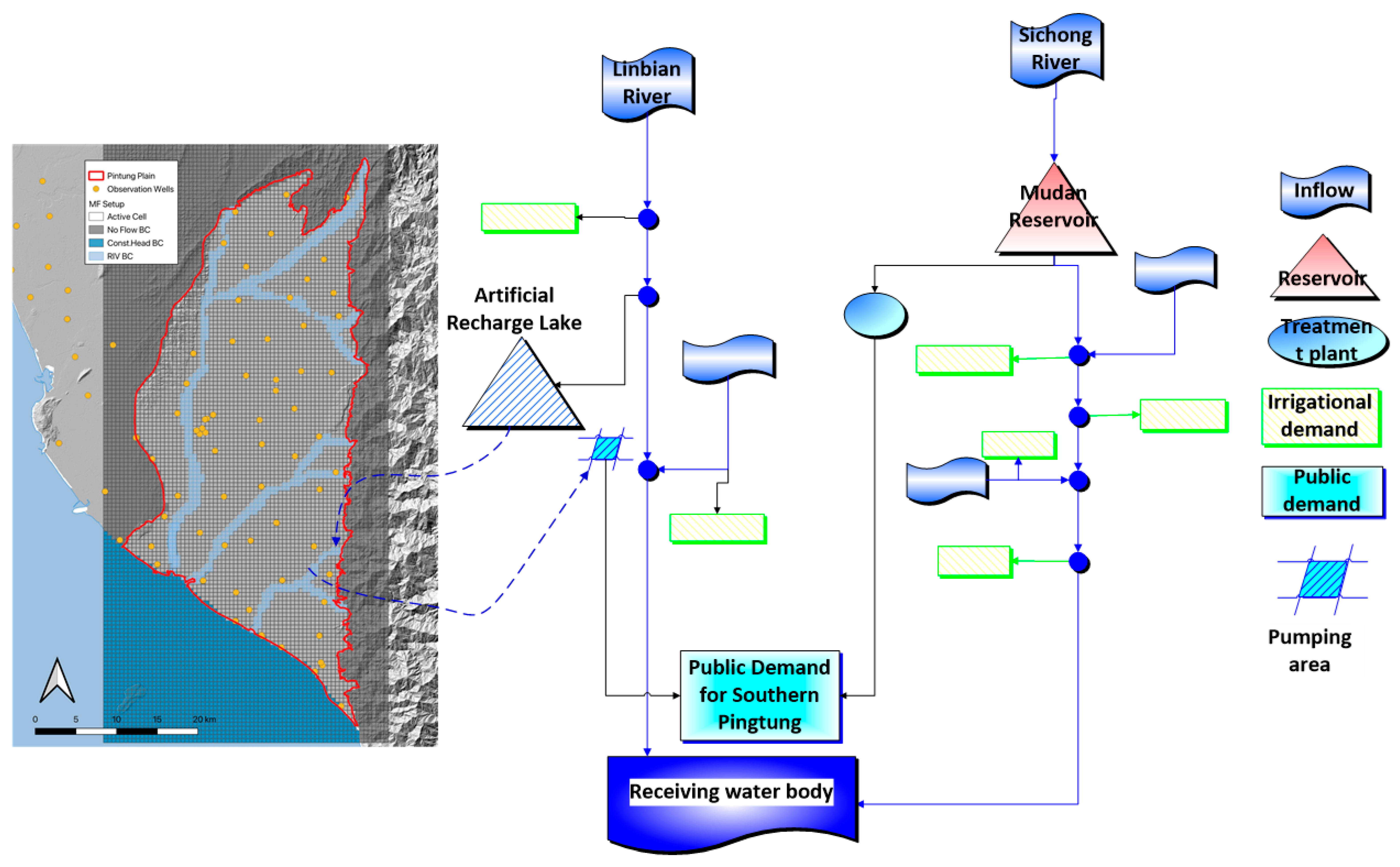

2.1. Surface Water Allocation Simulation Model

2.2. Groundwater Flow Model, Net Recharge, and OGLR

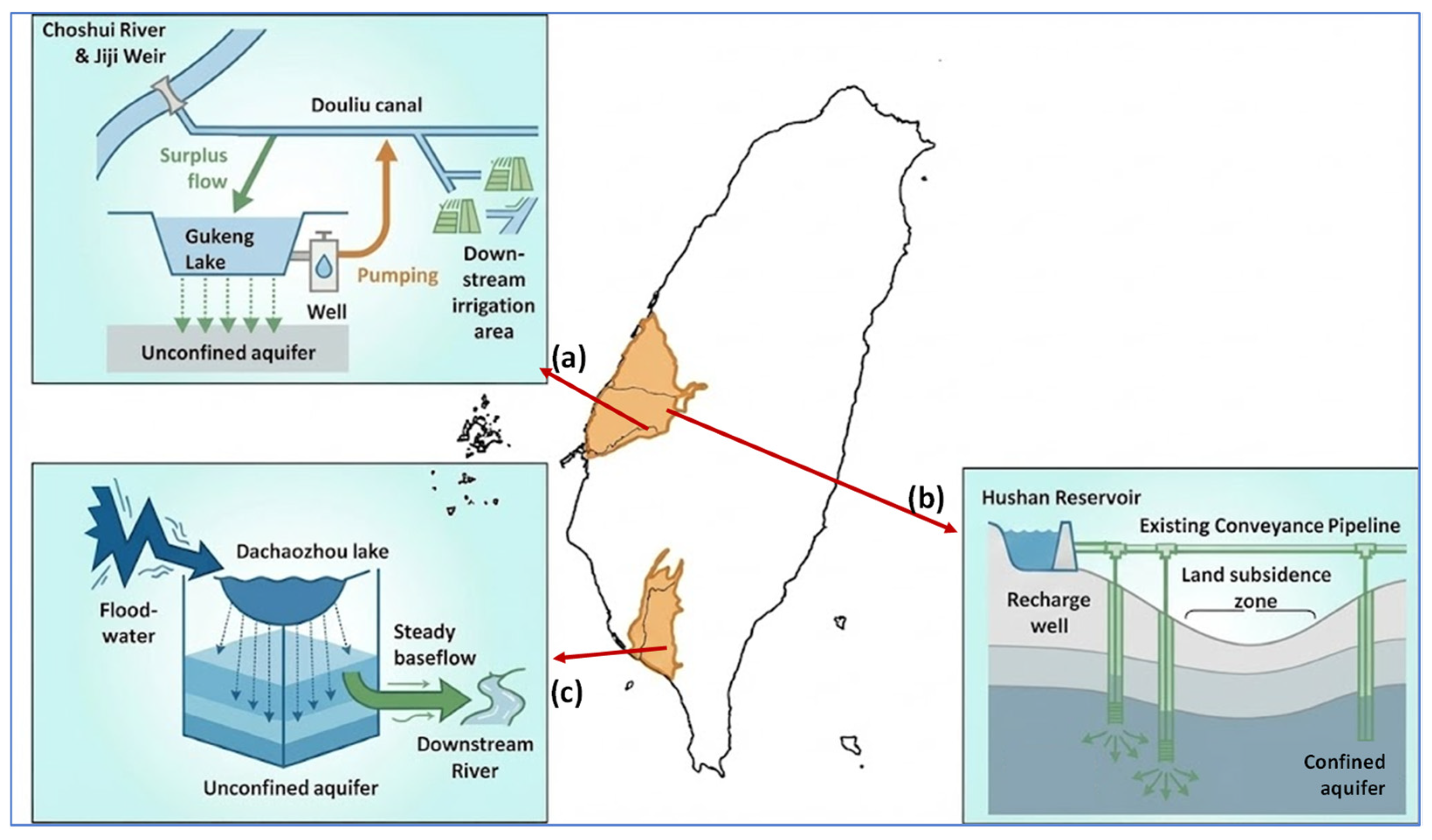

- In the case of the Gukeng Artificial Recharge Lake, the site is located on the southeastern margin of the Choshui River alluvial fan. Recharge from the lake was therefore assigned to the upper unconfined aquifer layer. The layer is composed of coarse sand and gravel with high permeability and an estimated saturated thickness of 100–150 m.

- The Yunlin recharge well is situated in the mid-fan land subsidence zone. The recharge wells inject into the second confined aquifer, which consists mainly of fine sand and silty sand and is overlain by the first regional aquitard. This aquifer occurs at depths of roughly 35–200 m with a thickness of 80–140 m, and is the principal pumping and subsidence-prone layer.

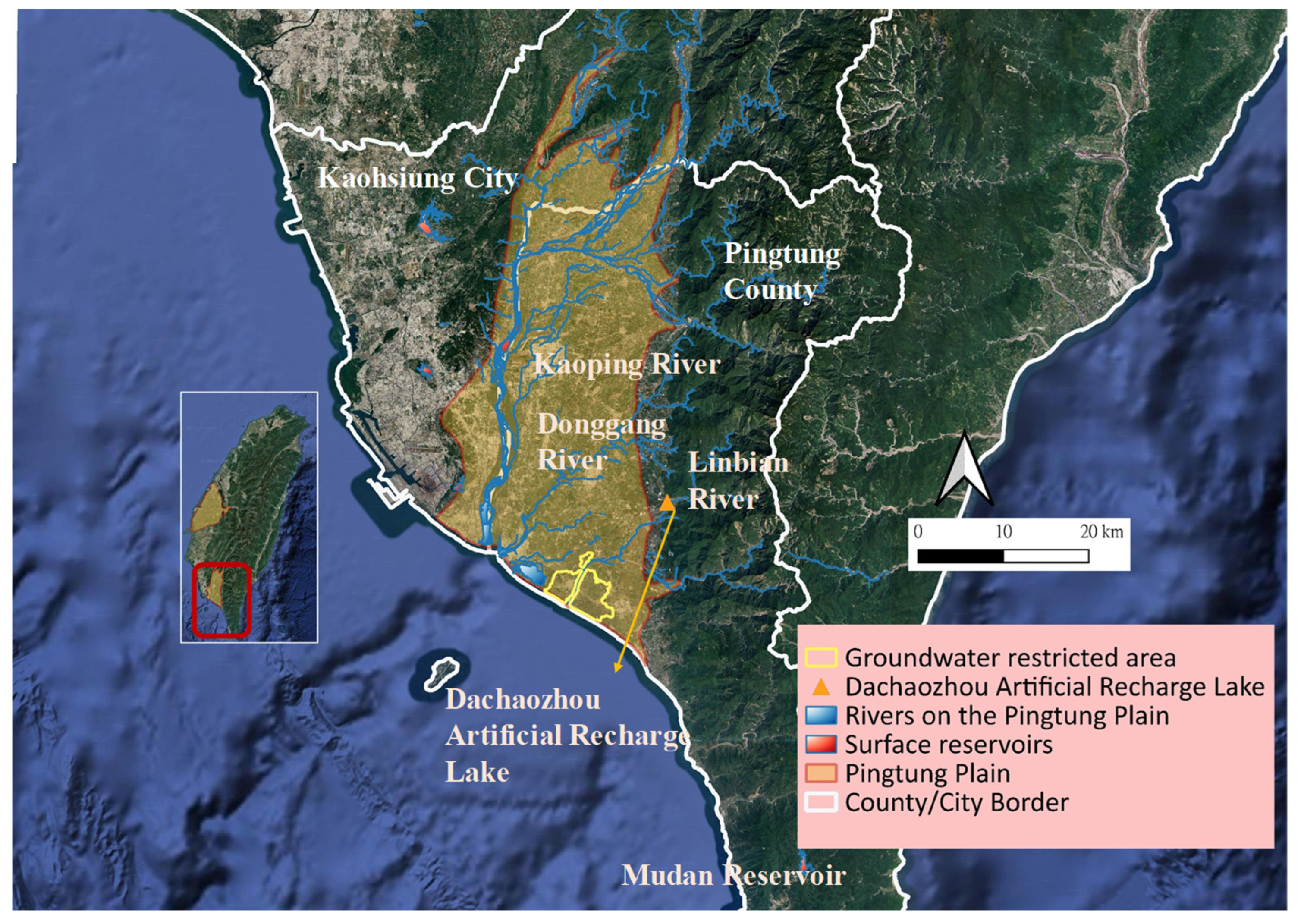

- In the case of the Dachaozhou Artificial Recharge Lake on the Pingtung Plain, the artificial lake overlies a thick, highly permeable unconfined aquifer composed of sand and gravel. Recharge from the lake was accordingly assigned to the upper unconfined layer controlling groundwater mound formation and subsequent baseflow release.

2.3. Integrated Framework and Concept of Conjunctive Surface–Groundwater Operation

- Pumping wells

- (1)

- Each pumping well node may contain multiple pumping locations. For each location, the pumping capacity and the corresponding aquifer layer and grid coordinates in MODFLOW must be predefined.

- (2)

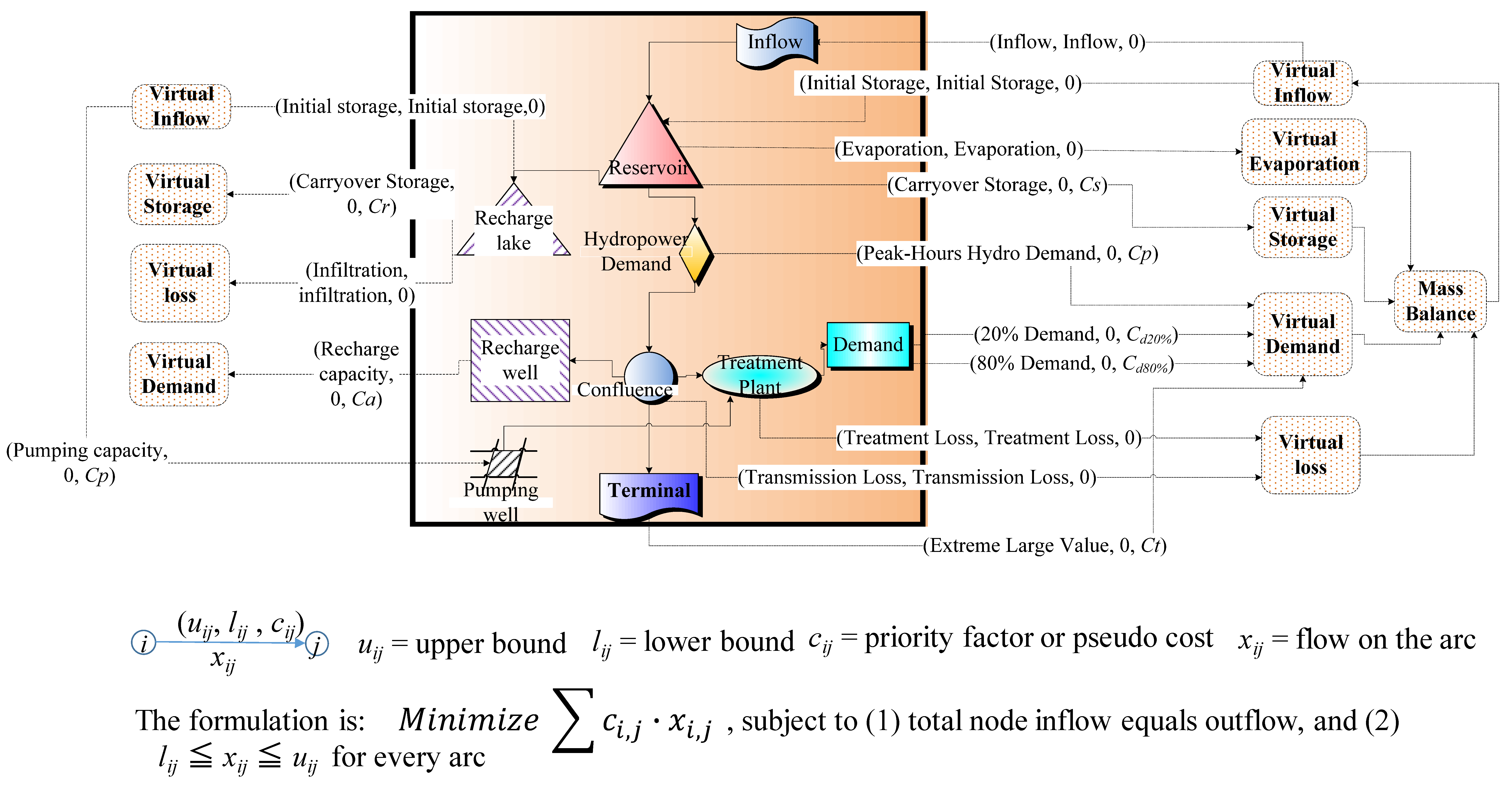

- The node functions similarly to an inflow node of WRASIM that introduces water into the network. However, unlike the inflow node whose upper and lower bounds are fixed (as shown in Figure 3), this node is associated with flexible flow values. The lower bound of the arc connected to the pumping well node (virtual pumping arc) is set to zero, while its upper bound equals the total pumping capacity.

- (3)

- By assigning different allocation-priority coefficients to the virtual pumping arc, various groundwater-use strategies can be simulated. For example, in Figure 3, when the coefficient Cp is designated such that Cp + Cd80% < 0 and Cp + Cd20% > 0, groundwater pumping serves only as a backup source. It is activated to meet demands of up to 80% of the requirement under the minimum-cost objective function of network flow programming. Conversely, when Cp = 0, groundwater is used routinely and preferentially, replacing reservoir storage releases during normal operation.

- Recharge Lake: A recharge lake functions similarly to a reservoir node in WRASIM but additionally estimates the infiltration volume entering the aquifer based on a specified infiltration rate (mm day−1) and the simulated daily average water surface area. The infiltration rate is assumed constant and independent of the hydraulic head difference between the lake water surface and the groundwater table. This assumption represents a long-term, time-averaged approximation of field infiltration conditions, as the measured rates inherently reflect the dominant influence of soil permeability and vadose-zone characteristics rather than short-term variations in the hydraulic gradient. Such simplification is considered appropriate for long-term, water balance-oriented simulations. The corresponding spatial domain of a recharge lake is linked to the grid cells and aquifer layers in MODFLOW. The infiltration coefficient determines the recharge volume per time step, which is restricted to the uppermost unconfined aquifer layer.

- Recharge Wells: A recharge well node operates analogously to a demand node. The recharge volume supplied to each well in WRASIM is then injected into the specified aquifer layer and grid cells defined in MODFLOW. Each recharge well must therefore be assigned its recharge capacity, spatial extent, and target aquifer in WRASIM. The recharge fluxes are imposed as specified inflows to the designated aquifer layer.

- By adjusting the cost coefficients Cr of the virtual storage arcs for recharge lakes and Ca of the virtual demand arcs for recharge wells, the priority relationship between surface water storage and groundwater recharge can be represented. For instance, if groundwater recharge is intended to utilize only surplus, the corresponding recharge arcs are assigned lower priority (i.e., higher cost coefficients) than those of other surface water uses or reservoir storages. The priority sequence for the case in Figure 3 follows the order Cd80% < Cd20% < Cs < Cp < Cr or Ca < 0 < Ct.

- Evaluate groundwater status: At the beginning of each ten-day period, groundwater levels simulated from the previous period are assessed for all pumping and recharge locations to determine whether they remain within the OGLR.

- (1)

- If groundwater levels at a pumping location fall below the bottom of the OGLR, pumping is halted for that period by setting the pumping upper bound in WRASIM to zero. Otherwise, pumping is allowed up to the equipment capacity.

- (2)

- If groundwater levels at a recharge location exceed the top of the OGLR, recharge operations are suspended or deprioritized by assigning higher cost coefficients to the corresponding recharge arcs.

- Simulate surface water allocation: WRASIM performs daily water-allocation simulations for the next ten-day period, computing the total planned groundwater pumping and recharge volumes.

- Simulate groundwater flow: MODFLOW is executed using the allocated pumping and recharge data to simulate groundwater flow and water-level variation within the analysis domain for the current period.

- Update and proceed: The groundwater levels at the end of the ten-day period are used as initial conditions for the next iteration of the coupled WRASIM–MODFLOW simulation.

3. Results of the Case Study

3.1. Gukeng Artificial Recharge Lake

- Basin-scale simulation: The first level focused on the broader Choshui River basin to evaluate the surplus flow available at the Jiji Weir, as shown in Figure 6a. The surplus flow is defined as the remaining volume of natural flow after deducting the entitled withdrawals and diversions of existing users within the water resource system. In the WRASIM model, this condition was represented by introducing a fictitious demand node whose allocation priority was set after all other demand and storage arcs in the system. The simulation results indicate that the annual inflow at the Jiji Weir totals 4.23 × 109 m3 yr−1, of which 1.69 × 109 m3 yr−1 remains as surplus after satisfying all designated water uses. These surplus volumes predominantly occur during the wet season from May to October.

- Canal-scale simulation: The second level independently simulated the water conveyance of the Douliu Canal and its branch networks, as shown in Figure 6b. In addition to the irrigation water allocated to the Douliu Canal from the previous basin-scale simulation, the model allowed the diversion of surplus water from the Jiji Weir during the wet season—subject to the maximum transmission capacity of the canal—to be conveyed to the Gukeng Artificial Recharge Lake for temporary storage. The designed surface area of the recharge lake is 66.5 ha, with a total storage capacity of approximately 4.08 × 106 m3. Based on in situ infiltration tests [29], the average infiltration rate was set at 2.57 m day−1. In the allocation sequence, the recharge lake was assigned a storage priority lower than that of all irrigation branches of the Douliu Canal. Therefore, surplus water was routed into the lake only when it was not yet full and all demands had been fulfilled. Once the lake reached full capacity, diversions were automatically suspended.

- Under the condition without additional recharge or pumping, the average annual water diversion to the downstream branches of the Douliu Canal below the Gukeng site was 22.28 × 106 m3, while the annual water deficit reached 29.72 × 106 m3, corresponding to an average annual deficit ratio of 0.58.

- With artificial recharge implemented, the simulated mean annual recharge volume reached 76.80 × 106 m3. After pumping (18.49 × 106 m3 yr−1) and reusing the recharged water, the average annual deficit in the downstream irrigation area decreased to 11.23 × 106 m3, reducing the deficit ratio to 0.22.

- Table 1 summarizes the simulation results of the abovementioned scenarios. Since the water supplied to the downstream agricultural area accounted for only about 0.53 times the total recharge volume, a substantial remaining capacity for managed abstraction from adjacent irrigation areas existed to further enhance water supply reliability.

3.2. Artificial Recharge in Land Subsidence Areas

- Recharge through the converted wells reaches 13.94 × 106 m3 per year—about 14% of the recharge volume provided by the lake—because surplus storage at Hushan Reservoir occurs mainly during the wet season, limiting the temporal availability for recharge.

- Despite the smaller volume, direct recharge into the subsidence zone raises groundwater levels at the Tuku station by an additional 3.52 m. Within approximately a 10 km radius, groundwater levels at the other three wells also rise by 264–3.44 m (see Figure 8). This indicates that the proposed strategy produces a much more pronounced localized benefit than lake infiltration alone.

3.3. Dachaozhou Artificial Recharge Lake

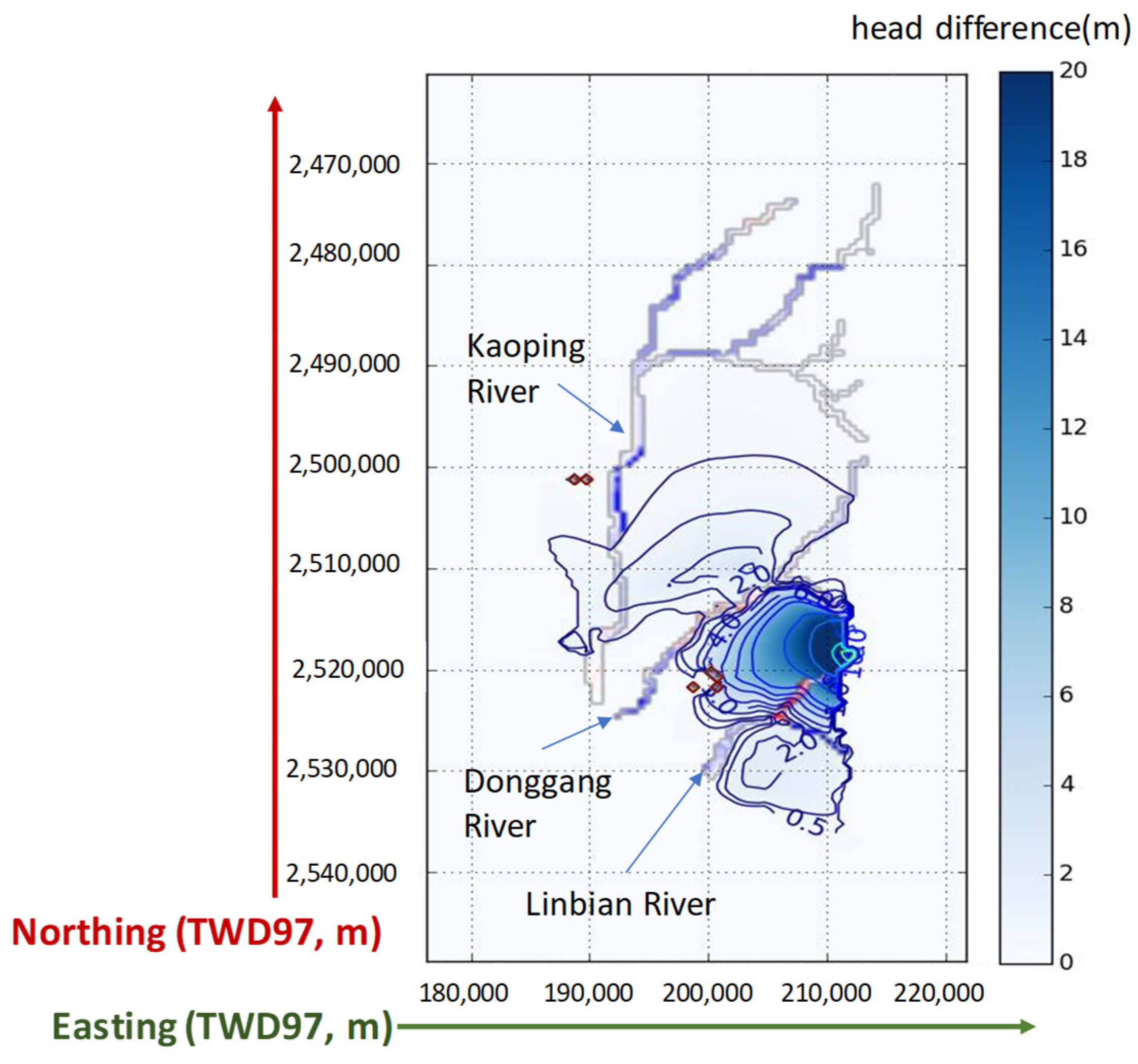

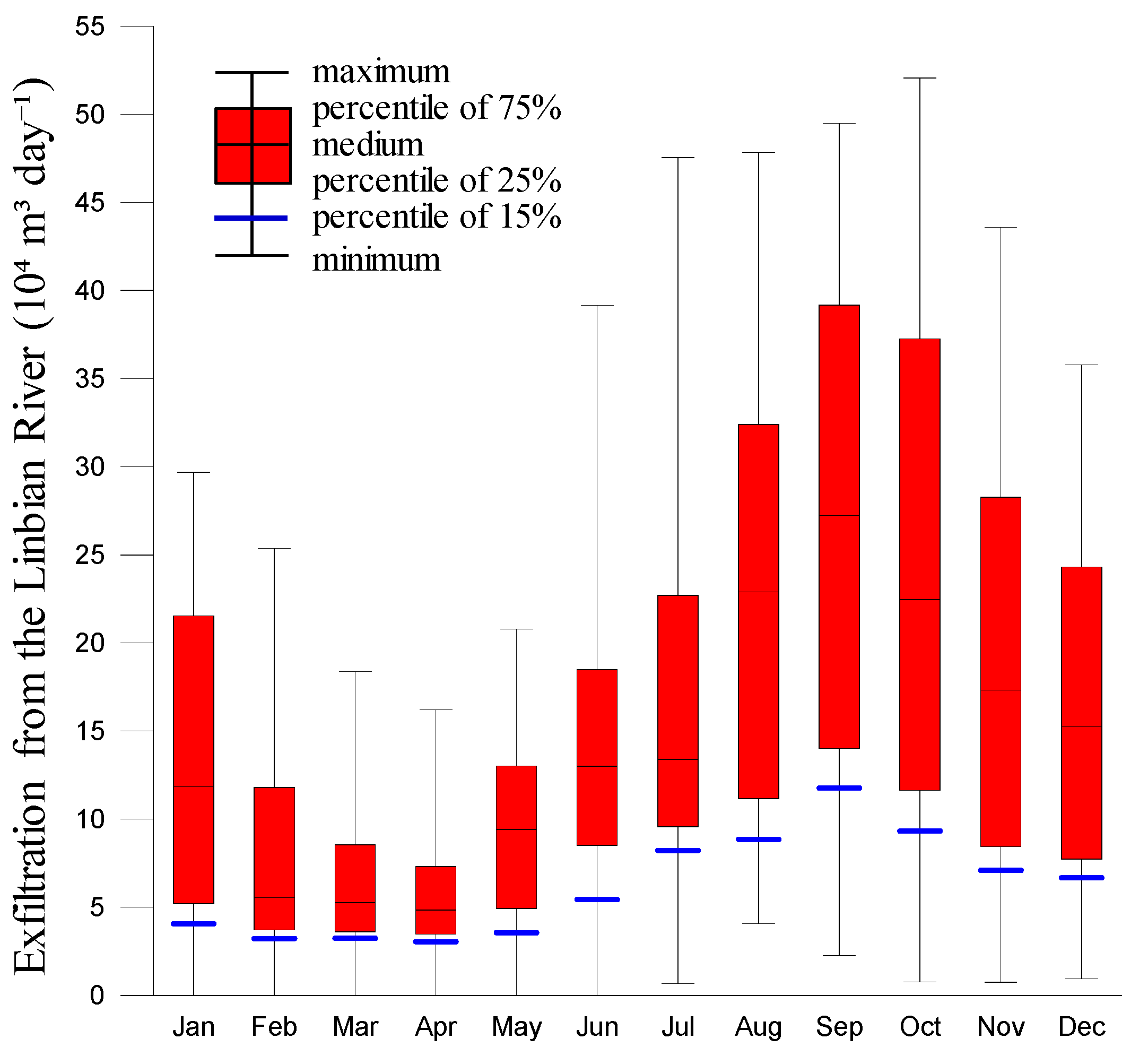

- Recharge effectiveness: Long-term simulations yielded an average annual recharge volume of 112.7 × 106 m3 yr−1. Incorporating this recharge into the groundwater model produced the simulated groundwater-level responses shown in Figure 11, which shows the differences in groundwater levels and river seepage/exfiltration (i.e., groundwater discharge to the channel) patterns with and without the Dachaozhou Artificial Recharge Lake at the end of the simulation periods. The results indicate that the rise in groundwater levels was most significant between the northern side of the Linbian River and the Donggang River. Some recharge water crossed beneath the Donggang River, influencing its right bank, while some water moved southward across the left bank of the Linbian River. A small portion of the recharge effect also extended toward the coastal zone of Pingtung.

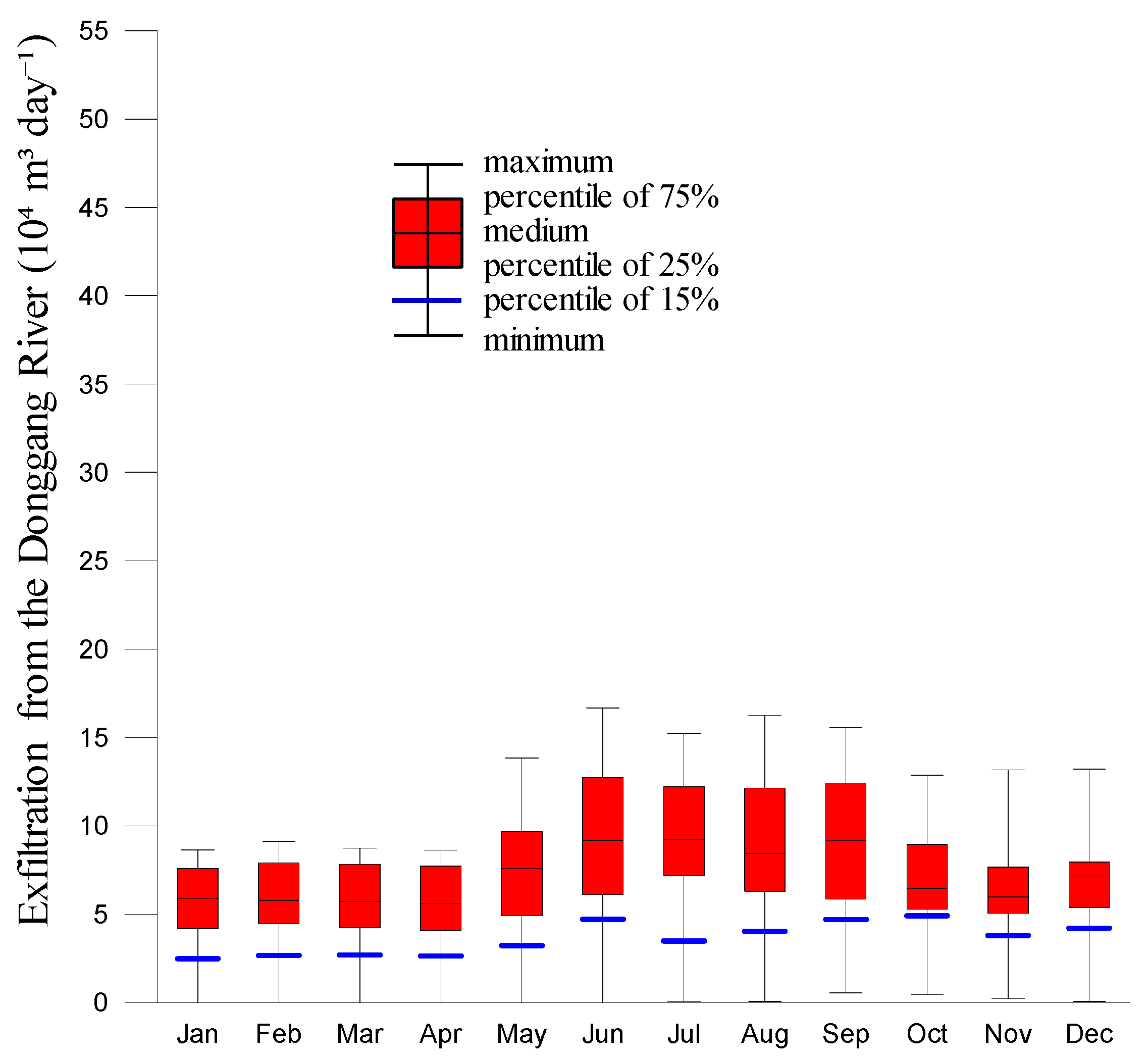

- River exfiltration: In Figure 11, blue zones denote river infiltration, while red zones indicate exfiltration. The elevated groundwater table caused most river segments to shift toward exfiltration, discharging stored groundwater from the aquifer. Throughout the simulation period, the mean annual recharge volume was 112.7 × 106 m3, of which approximately 72% was discharged through river exfiltration, 6% exited through constant-head boundaries, and the remaining 22% contributed to increased system storage.

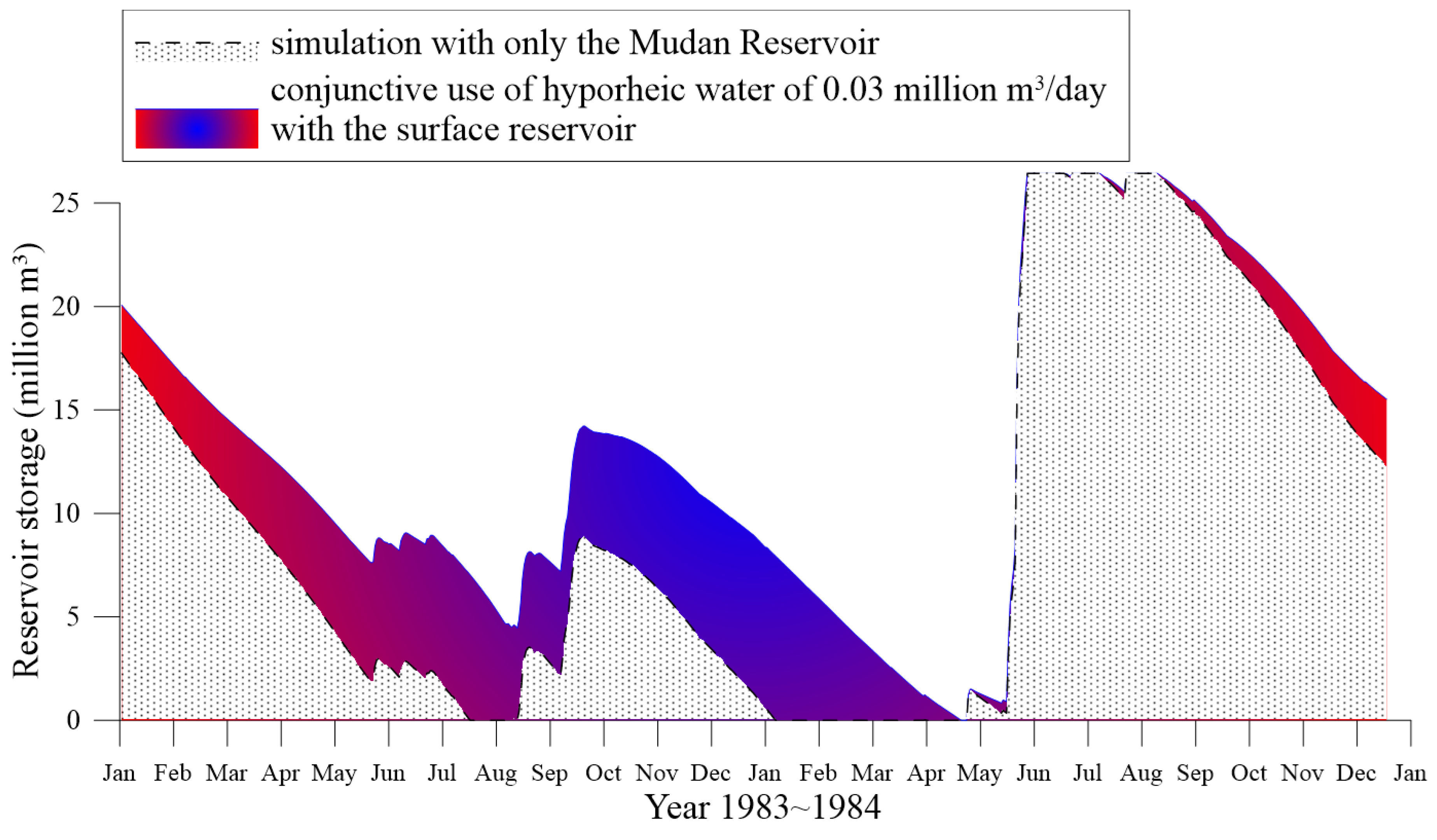

- The average daily water supply from the Mudan Reservoir was 97,900 m3. Water shortages primarily occurred between the wet season of 1993 and the dry season of 1994. During this hydrological year (1 June 1993–31 May 1994), the annual water deficit ratio reached 37.8%, while no shortages were observed in other years.

- During the above severe drought period, the reservoir storage dropped to zero for 275 days, during which the Mudan water supply system was entirely depleted, indicating that backup water sources were urgently required during this extreme event.

3.4. Discussion of Case-Specific Characteristics

- (a)

- Gukeng Artificial Recharge Lake—distributed capture of short-duration surplus flowsThe Gukeng case reflects a spatially distributed, surface water-oriented strategy that captures short but frequent surplus flows from the Choshui River system. By using fallow fields and irrigation channels as temporary infiltration spaces, the system effectively converts wet season surplus into intra-seasonal supply. This “trading space for time” mechanism relies on rapid operational adjustments and leverages existing canal networks. Its effectiveness lies in spatial flexibility and responsiveness to short-duration hydrological opportunities (Table 2 and Table 3).

- (b)

- Conversion of decommissioned public wells to recharge wells—centralized injection with policy-driven feedbackThe recharge well strategy exemplifies a centralized support–distributed feedback framework. Surplus storage from the Hushan Reservoir is conveyed through existing pipelines and injected directly into confined aquifers within the subsidence zone. Despite a smaller recharge volume than the lake-based system, direct injection yields a substantial groundwater-level increase (up to 3.52 m at Tuku and 2.64–3.44 m at surrounding wells within ~10 km). This approach strengthens the feedback loop between groundwater levels and upstream reservoir operation, improving institutional flexibility and enhancing resilience to land subsidence. As summarized in Table 2 and Table 3, the key contribution of this strategy lies in its policy-oriented controllability and its ability to translate centralized surface water surplus into targeted subsurface recovery.

- (c)

- Dachaozhou Artificial Recharge Lake—temporal accumulation and delayed releaseDachaozhou operates as a temporal regulation strategy in which short-duration floodwaters are rapidly infiltrated into thick alluvial aquifers. Stored groundwater subsequently contributes to sustained baseflow and enhances downstream surface water reliability. This “accumulating volume over time” approach provides long-term drought buffering and reduces reliance on upstream reservoirs during extended dry periods. Its system benefit arises primarily from delayed release and aquifer-mediated regulation, as opposed to immediate reuse (Table 2 and Table 3).

3.5. Limitations and Future Extensions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OGLR | Operational Groundwater Level Range |

References

- Sophocleous, M. Interactions between groundwater and surface water: The state of the science. Hydrogeol. J. 2002, 10, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, P.; Stuyfzand, P.; Grischek, T.; Lluria, M.; Pyne, R.D.G.; Jain, R.C.; Bear, J.; Schwarz, J.; Wang, W.; Fernandez, E.; et al. Sixty years of global progress in managed aquifer recharge. Hydrogeol. J. 2019, 27, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custodio, E. Aquifer overexploitation: What does it mean? Hydrogeol. J. 2002, 10, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossman, N.R.; Zlotnik, V.A. Review: Regional groundwater flow modeling in heavily irrigated basins of selected states in the western United States. Hydrogeol. J. 2013, 21, 1173–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.S.; McCornick, P.G.; Sarwar, A.; Sharma, B.R. Challenges and prospects of sustainable groundwater management in the Indus Basin, Pakistan. Water Resour. Manag. 2010, 24, 1551–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, D.P.; van Beek, E. Water Resource Systems Planning and Management: An Introduction to Methods, Models and Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L.; He, J.; Wang, X. A quantitative analysis framework for analyzing impacts of climate change on water–food–energy–ecosystem nexus in irrigation areas based on WEAP–MODFLOW. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 470, 143315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morway, E.D.; Niswonger, R.G.; Triana, E. Toward improved simulation of river operations through integration with a hydrologic model. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 82, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitlasten, W.; Morway, E.D.; Niswonger, R.G.; Gardner, M.; White, J.T.; Triana, E.; Selkowitz, D. Integrated hydrology and operations modeling to evaluate climate change impacts in an agricultural valley irrigated with snowmelt runoff. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR027924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, W.W.G. Review of parameter-identification procedures in groundwater hydrology—The inverse problem. Water Resour. Res. 1986, 22, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, W.W.G. Review: Optimization methods for groundwater modeling and management. Hydrogeol. J. 2015, 23, 1051–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, S.M.; Voss, C.I.; Gill, P.E.; Murray, W.; Saunders, M.A.; Wright, M.H. Aquifer reclamation design: The use of contaminant transport simulation combined with nonlinear programing. Water Resour. Res. 1984, 20, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlfeld, D.P.; Mulvey, J.M.; Pinder, G.F.; Wood, E.F. Contaminated groundwater remediation design using simulation, optimization, and sensitivity theory: 1. Model development. Water Resour. Res. 1988, 24, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Willis, R.; Yeh, W.W.G. Optimal control of nonlinear groundwater hydraulics using differential dynamic programming. Water Resour. Res. 1987, 23, 2097–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, D.C.; Lin, M.D. Genetic algorithm solution of groundwater management models. Water Resour. Res. 1994, 30, 1897–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zheng, C. Ground water management optimization using genetic algorithms and simulated annealing: Formulation and comparison. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 1998, 34, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, F.N.F.; Wu, C.W. Reducing the impacts of flood-induced reservoir turbidity on a regional water supply system. Adv. Water Resour. 2010, 33, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, F.N.F.; Wu, C.W. Determination of cost coefficients of a priority-based water allocation linear programming model—A network flow approach. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 18, 1857–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.W.; Chou, F.N.F.; Lee, F.Z. Minimizing the impact of vacating instream storage of a multi-reservoir system: A trade-off study of water supply and empty flushing. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 2063–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbaugh, A.W. MODFLOW-2005, The U.S. Geological Survey Modular Ground-Water Model—The Ground-Water Flow Process. U.S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods 6-A16, 2005. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://pubs.usgs.gov/tm/2005/tm6A16/PDF/TM6A16.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjTpNiV7-GRAxW8k68BHeS6CNIQFnoECAwQAQ&usg=AOvVaw0b7sb9n4YgNMQCWqYZ0bbl (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Anderson, M.P.; Woessner, W.W.; Hunt, R.J. Applied Groundwater Modeling: Simulation of Flow and Advective Transport, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.S.; Yeh, W.W.G. Parameter identification in an inhomogeneous medium with the finite-element method. SPE J. 1976, 16, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, W.W.G.; Yoon, Y.S. Aquifer parameter identification with optimum dimension in parameterization. Water Resour. Res. 1981, 17, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, D.; Townley, L.R. A Reassessment of the Groundwater Inverse Problem. Water Resour. Res. 1996, 32, 1131–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.Z. Inverse Problems in Ground-Water Modeling; Kluwer Academic: Boston, MA, USA, 1994; 352p. [Google Scholar]

- Kourakos, G.; Mantoglou, A. Inverse groundwater modeling with emphasis on model parameterization. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48, W05540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, J.; Alcolea, A.; Medina, A.; Hidalgo, J.; Slooten, L.J. Inverse problem in hydrogeology. Hydrogeol. J. 2005, 13, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M. The BOBYQA Algorithm for Bound Constrained Optimization Without Derivatives; Technical report, DAMTP 2009/NA06; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yunlin Irrigation Association. Assessment of Infiltration and Groundwater Recharge Benefits of the Gukeng Multipurpose Retention Pond Project; Agency of Irrigation and Farmland; Ministry of Agriculture: Taipei, Taiwan, 2018. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Economic Affairs. Concrete Solutions and Action Plan for Land Subsidence Mitigation in the Yunlin–Changhua Area; Ministry of Economic Affairs: Taipei, Taiwan, 2011. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pingtung County Government. Analysis and Evaluation of Groundwater Recharge Lake Construction and Flow Observation Data of the Linbian River Project; Pingtung County Government: Pingtung, Taiwan, 2014. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Scenarios | Deficit Ratio of Downstream Irrigation Demands | Annual Recharge Volume (Million m3/year) | Annual Pumping Volume (Million m3/year) |

| Default without MAR | 0.58 | – | – |

| Implementing MAR | 0.22 | 76.80 | 18.49 |

| Aspect | (a) Gukeng Artificial Recharge Lake | (b) Conversion of Existing Pumping Wells at Water Treatment Plants into Recharge Wells | (c) Dachaozhou Artificial Recharge Lake |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recharge source | Surplus irrigation water | Excess reservoir storage | River floodwater |

| Recharge measure | Recharge lake | Recharge wells | Recharge lake |

| Conveyance to recharge area | Existing irrigation canals | Dedicated transmission pipelines | Direct diversion of river floodwater |

| Temporal and spatial scale of recharge | Operated within irrigation season with intra-annual cycling | Concentrated during wet seasons with seasonal response | Few days during flood events with long-term aquifer response |

| Use of recharged water | Pumped near the recharge area and conveyed back to the irrigation system | No direct withdrawal; used indirectly by increasing upstream weir withdrawal | Retained in aquifer to sustain baseflow for subsequent surface water abstraction |

| Representative quantified outcomes | Deficit ratio reduced from 0.58 to 0.22 | Groundwater-level increase of ~2.64–3.52 m in the severe land subsidence zone | The number of empty-reservoir days at Mudan Reservoir reduced from 275 to 33 days. |

| Additional benefits or highlights | “Trading space for time” strategy: utilizing fallow fields as infiltration areas to rapidly capture surplus water | Policy-oriented recharge: releasing agricultural water rights during dry periods and improving land stability | Improved downstream river water quality and increased available intake volume |

| Case | Operational Philosophy | Recharge Characteristics (From Concentrated Source to Distributed Infiltration) | Post-Recharge Utilization Characteristics (From Concentrated to Distributed Use) | Temporal Characteristics | Typical Mechanism | System Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gukeng Artificial Recharge Lake | Trading space for time | Surplus flow at the Jiji Weir (concentrated) distributed through canal networks to mid–downstream recharge lakes | Locally concentrated pumping at recharge lakes redistributed to downstream irrigation areas | Short-term | Surplus irrigation flow → distributed recharge | Expands irrigated area |

| Dachaozhou Artificial Recharge Lake | Accumulating volume over time | Floodwater concentrated at a single site infiltrates to the aquifer and emerges as a distributed baseflow or underflow accessible at multiple points | River abstractions incorporated into a distributed municipal supply network | Long-term | Flood → concentrated recharge → delayed baseflow | Enhances resilience of public water supply system |

| Recharge wells converted from existing water treatment plant wells | Centralized support–distributed feedback | Excess storage above reservoir rule curve (centralized) is conveyed via pipelines to multiple distributed wells for precise deep injection | Recharge in subsidence areas indirectly feeds back to the upstream weir, enabling increased groundwater use or reallocation at the Jiji Weir | Stable | Centralized recharge water resources → subsidence-zone injection | Improves regional balance and upstream diversion flexibility |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, C.-W.; Chou, F.N.-F.; Chen, Y.-W. Conjunctive-Use Frameworks Driven by Surface Water Operations: Integrating Concentrated and Distributed Strategies for Groundwater Recharge and Extraction. Water 2026, 18, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010130

Wu C-W, Chou FN-F, Chen Y-W. Conjunctive-Use Frameworks Driven by Surface Water Operations: Integrating Concentrated and Distributed Strategies for Groundwater Recharge and Extraction. Water. 2026; 18(1):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010130

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Chia-Wen, Frederick N.-F. Chou, and Yu-Wen Chen. 2026. "Conjunctive-Use Frameworks Driven by Surface Water Operations: Integrating Concentrated and Distributed Strategies for Groundwater Recharge and Extraction" Water 18, no. 1: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010130

APA StyleWu, C.-W., Chou, F. N.-F., & Chen, Y.-W. (2026). Conjunctive-Use Frameworks Driven by Surface Water Operations: Integrating Concentrated and Distributed Strategies for Groundwater Recharge and Extraction. Water, 18(1), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/w18010130