Resettlement Governance in Large-Scale Urban Water Projects: A Policy Lifecycle Perspective from the Danjiangkou Reservoir Case in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

- During different policy stages, how have the five types of livelihood capital—natural, physical, human, financial, and social—been affected, and through what mechanisms?

- How has China’s reservoir resettlement policy evolved amid shifting national development goals and institutional contexts? What distinct phases and characteristics can be observed in this evolution?

- What institutional experiences and policy insights does the Danjiangkou case offer for building an integrated, sustainable, and socially inclusive urban water governance system?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Urban Hydraulic Infrastructure and Institutional Resettlement: The Hidden Governance Issue in Development

2.2. Policy Evolution and the Life-Cycle Perspective of Water Governance

2.3. Sustainable Livelihood Framework and Micro-Level Pathways of Resettlement Governance

3. Materials and Methods

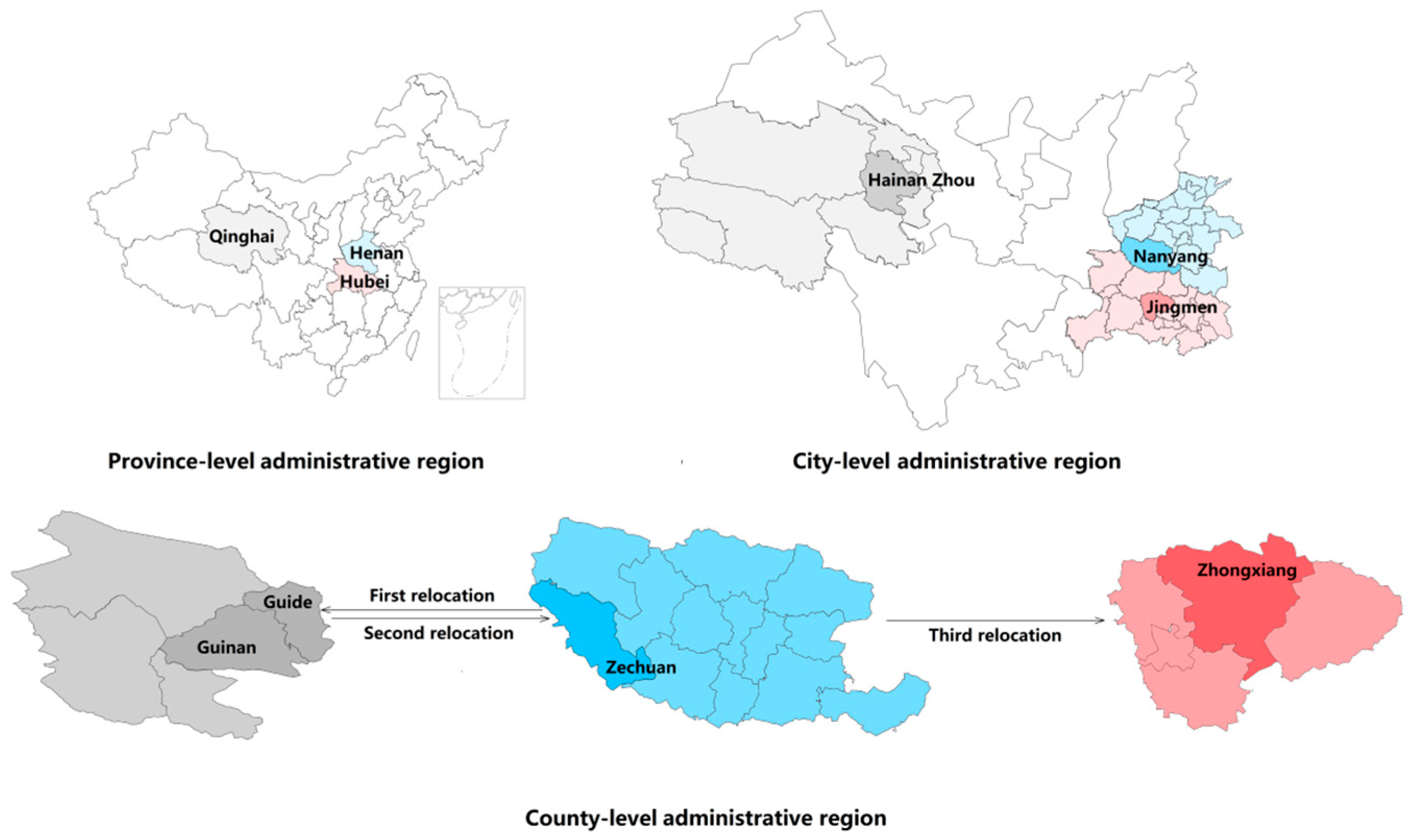

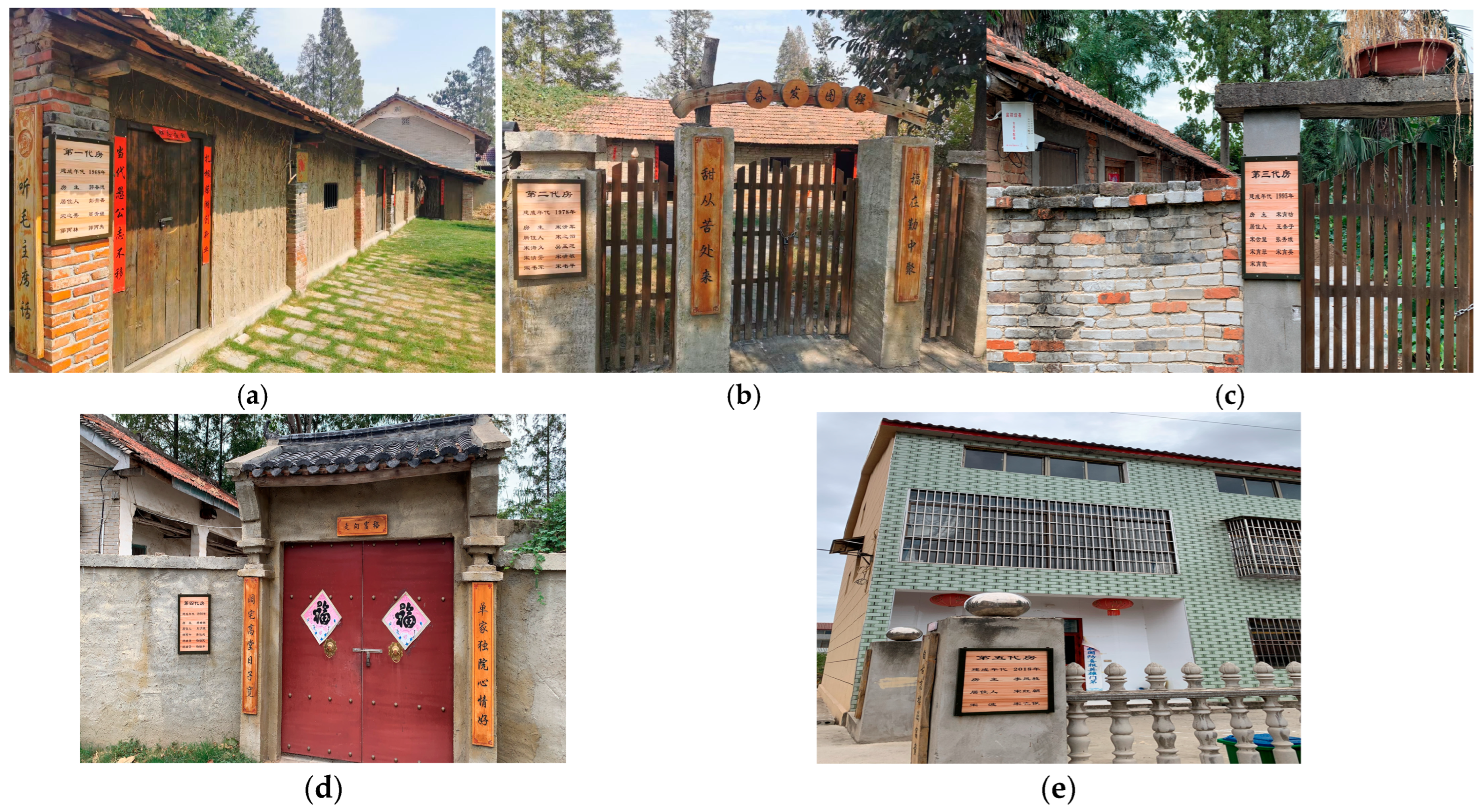

3.1. Case Selection and Research Background

3.2. Data Sources and Methods of Data Collection

3.3. Research Design and Theoretical Analytical Framework

4. Evolution of Livelihood Capital Across Four Developmental Stages

5. Policy Evolution in the Resettlement Livelihood Cycle

5.1. Exploratory Resettlement Stage: Early Relocation and Institutional Failure

- Planning failures: Absence of scientific environmental and socioeconomic assessments led to severe mismatches between population capacity and resource allocation in resettlement areas.

- Policy fragmentation: Strong vertical control but weak horizontal coordination caused resource bottlenecks and inconsistent policy implementation.

- Rigid social governance: Top-down, command-style management suppressed local adaptation and group agency, depriving migrants of institutional channels for expression and negotiation.

5.2. Return Migration Phase: Policy Response and Institutional Adjustment

- Lagging policy compensation: Although the state eventually provided limited support for returnees, compensation mechanisms lacked continuity, leaving livelihood recovery largely dependent on individual and community self-help.

- Restorative social relations: The return process reintegrated original kinship and geographic bonds into the livelihood system, strengthening internal trust and forming a grassroots “social recovery” structure.

- Reflexive governance cognition: The practice of return migration led the state to recognize the limitations of coercive, one-size-fits-all resettlement models, providing empirical grounding for more flexible, differentiated policy designs in the future.

5.3. Self-Reliance Stage: Self-Reliant Recovery Under Limited Support

- Limited policy support: Fiscal constraints restricted the scope of government assistance. Most policies prioritized short-term reconstruction rather than sustained livelihood protection, compelling migrants to depend on self-reliance for recovery.

- Labor-driven livelihood restoration: Labor and skills became central to livelihood accumulation. Migrants engaged in intensive agricultural and handicraft production, transforming manual work into a key mechanism for rebuilding material capital.

- Reconstruction of social structure: In the absence of robust formal institutions, social capital was regenerated through cooperatives, production brigades, and neighborhood mutual aid, making community organization the primary carrier of social resilience.

5.4. Economic Revitalization Stage: Targeted Poverty Alleviation and Urban–Rural Integration

- Policy precision: Targeted poverty alleviation and industrial support policies optimized resource allocation, replacing earlier “broad but inefficient” interventions.

- Economic diversification: Industrial upgrading and non-agricultural employment accelerated capital accumulation, enabling households to transition from single-source agricultural income to multi-income structures.

- Social integration: Strengthened community governance and inclusive public services blurred social boundaries between resettlers and local residents, enhancing social identity and belonging.

6. Discussion: Institutional Lessons for Integrated Water Governance

6.1. Migrant Agency: From Administrative Dependence to Self-Organized Resilience

6.2. Rights Expression: From Silent Compliance to Negotiated Participation

6.3. Transformation of Needs: From Survival Security to Development Empowerment

6.4. Social Identity Transformation: From the Excluded to the Integrated Citizen

7. Conclusions

- Institutional Learning over Time: Policy experiences accumulated across different stages have promoted the transformation of resettlement governance from administrative management to developmental institutions.

- Policy Responsiveness as Livelihood Infrastructure: Flexible and adaptive governance mechanisms are as vital as material compensation.

- Co-Production of Development: Future resettlement governance should establish a collaborative model among government, communities, and markets to form a sustainable livelihood support system.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Number | Interview Time | Name | Age | Gender | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 September 2021 | DHL | 42 | male | migrant |

| 2 | 11 September 2021 | HGX | 35 | male | migrant |

| 3 | 11 September 2021 | HZX | 56 | male | migrant |

| 4 | 11 September 2021 | ZXC | 65 | male | migrant |

| 5 | 12 September 2021 | QSL | 35 | male | migrant |

| 6 | 12 September 2021 | HXM | 45 | female | migrant |

| 7 | 12 September 2021 | ZS | 40 | female | migrant |

| 8 | 12 September 2021 | QZH | 42 | male | migrant |

| 9 | 13 September 2021 | NP | 48 | male | migrant |

| 10 | 13 September 2021 | HXH | 45 | male | migrant |

| 11 | 15 December 2022 | ZSL | 34 | male | migrant |

| 12 | 15 December 2022 | LC | 32 | female | migrant |

| 13 | 15 December 2022 | JJQ | 28 | female | migrant |

| 14 | 16 December 2022 | WJQ | 30 | female | migrant |

| 15 | 16 December 2022 | WXQ | 30 | female | migrant |

| 16 | 16 December 2022 | YYJ | 40 | male | migrant |

| 17 | 17 December 2022 | WYH | 40 | male | migrant |

| 18 | 17 December 2022 | WX | 42 | male | migrant |

| 19 | 17 December 2022 | WHL | 40 | male | migrant |

| 20 | 17 December 2022 | WTF | 27 | male | migrant |

| 21 | 11 August 2023 | HIJ | 33 | female | migrant |

| 22 | 11 August 2023 | DLX | 22 | female | migrant |

| 23 | 11 August 2023 | ZQC | 30 | male | migrant |

| 24 | 12 August 2023 | QXL | 45 | male | migrant |

| 25 | 12 August 2023 | QXS | 37 | male | migrant |

| 26 | 12 August 2023 | QDW | 28 | female | migrant |

| 27 | 13 August 2023 | QXZ | 37 | female | migrant |

| 28 | 13 August 2023 | QXR | 40 | female | migrant |

| 29 | 13 August 2023 | QLZ | 55 | female | migrant |

| 30 | 13 August 2023 | QH | 60 | female | migrant |

| 31 | 14 September 2021 | WXY | 40 | male | water conservancy official |

| 32 | 14 September 2021 | MHT | 32 | male | water conservancy official |

| 33 | 14 September 2021 | MXS | 42 | male | water conservancy official |

| 34 | 15 December 2022 | SZD | 46 | female | water conservancy official |

| 35 | 15 December 2022 | YXL | 33 | female | civil affairs official |

| 36 | 15 December 2022 | YHD | 55 | male | civil affairs official |

| 37 | 10 August 2023 | JZ | 56 | male | civil affairs official |

| 38 | 11 August 2023 | LXS | 58 | male | civil affairs official |

| 39 | 11 August 2023 | LN | 54 | male | civil affairs official |

| 40 | 11 August 2023 | WYH | 37 | male | agricultural official |

| 41 | 11 August 2023 | WX | 47 | female | agricultural official |

| 42 | 12 August 2023 | LXS | 48 | female | agricultural official |

| 43 | 12 August 2023 | ZXL | 50 | male | township official |

| 44 | 13 August 2023 | ZHX | 46 | male | township official |

| 45 | 13 August 2023 | QXB | 47 | male | township official |

| 46 | 13 August 2023 | CLS | 42 | male | township official |

| 47 | 14 August 2023 | CHY | 56 | male | township official |

| 48 | 14 August 2023 | ZPL | 42 | male | township official |

| Number | Respondent Category | Stage | Interview Question |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Government Officials | Policy Formation | What are the most crucial goals and principles in formulating the Danjiangkou Reservoir resettlement policy? How do these goals reflect national strategies and local development needs? |

| 2 | Government Officials | Policy Formation | How were opinions from central departments, local governments, and expert teams negotiated and integrated during the policy formation stage? |

| 3 | Government Officials | Policy Formation | Were pilot projects, debates, or stakeholder investigations conducted during early design? What were their functions? |

| 4 | Government Officials | Policy Implementation | What major institutional or resource-based constraints (funds, land, indicators, cross-regional coordination) emerged during implementation? How were these addressed? |

| 5 | Government Officials | Policy Implementation | How does cross-departmental collaboration (development and reform, water resources, agriculture, civil affairs, finance, etc.) operate? Which links show lower efficiency? |

| 6 | Government Officials | Policy Implementation | How does the government ensure enforcement of resettlement standards, industrial support policies, and continuity of public services? Are there localized adaptations or deviations? |

| 7 | Government Officials | Evaluation & Feedback | How does the government monitor and evaluate resettlement effectiveness (economy, housing, social adaptation, satisfaction)? Is there a formal evaluation system? |

| 8 | Government Officials | Evaluation & Feedback | Do migrants’ demands and challenges change during later phases? How does the government detect and respond to these changes? |

| 9 | Government Officials | Policy Adjustment | Has the government revised or improved the resettlement policy during the later policy cycle? What are representative practices? |

| 10 | Government Officials | Policy Adjustment | What institutional experiences from Danjiangkou are most significant for national governance? What lessons apply to other major water projects? |

| 11 | Local Grassroots officer | Policy Transmission & Implementation | How do grassroots governments decompose tasks, assign responsibilities, and mobilize the masses after receiving higher-level policies? |

| 12 | Local Grassroots officer | Policy Transmission & Implementation | What is the most difficult task in implementation (housing construction, relocation, compensation, verification)? Why? |

| 13 | Local Grassroots officer | Policy Transmission & Implementation | Are there shortages in resources, personnel, or execution authority? How is “flexible execution” practiced? |

| 14 | Local Grassroots officer | Cross-Level Collaboration | How do upper-level governments, departments, and construction units coordinate during resettlement? Is the coordination cost high? |

| 15 | Local Grassroots officer | Cross-Level Collaboration | Do social forces (enterprises, NGOs, design institutes, community groups) participate in resettlement? How effective are they? |

| 16 | Local Grassroots officer | Community Governance & Development | How is governance in new migrant communities constructed (Party organization, neighborhood committees, grid governance)? What challenges exist? |

| 17 | Local Grassroots officer | Community Governance & Development | What are migrants’ main demands? How do grassroots governments respond? |

| 18 | Local Grassroots officer | Community Governance & Development | What working methods support employment, industrial development, and assistance for vulnerable households? Which are most effective? |

| 19 | Local Grassroots officer | Policy Evaluation & Adjustment | Which aspects of superior policies do not match local realities? How is reinterpretation or adjustment conducted? |

| 20 | Local Grassroots officer | Policy Evaluation & Adjustment | What are the most successful practices in grassroots governance? What areas require improvement? |

| 21 | Migrant Groups | Pre-Relocation | How did you first learn about the relocation policy? What were your main concerns and expectations? |

| 22 | Migrant Groups | Pre-Relocation | Were briefings, consultations, or mobilization activities organized by government or village groups? Was communication adequate? |

| 23 | Migrant Groups | Relocation & Resettlement | How was your relocation experience (housing allocation, compensation settlement, item transfer)? What difficulties occurred? |

| 24 | Migrant Groups | Relocation & Resettlement | Have housing conditions and public services (schools, healthcare, transportation) met policy standards? |

| 25 | Migrant Groups | Relocation & Resettlement | What changes occurred in your livelihood (employment, land, income) after relocation? |

| 26 | Migrant Groups | Adaptation & Integration | How are interpersonal relationships, neighborhood interactions, and cultural adaptation in the new community? Are there conflicts with indigenous residents? |

| 27 | Migrant Groups | Adaptation & Integration | Are you satisfied with government support such as industrial assistance, training, and job referrals? What is the actual effect? |

| 28 | Migrant Groups | Adaptation & Integration | Have supportive policies (door-to-door visits, aid for vulnerable households, education support) been helpful? |

| 29 | Migrant Groups | Policy Evaluation | Which policies are most effective? Which have gaps or fall short of expectations? |

| 30 | Migrant Groups | Policy Evaluation | Where should the government strengthen support in the future (employment, industry, healthcare, elderly care, community governance)? |

References

- MacAlister, C.; Subramanyam, N. Climate change and adaptive water management: Innovative solutions from the global South. Taylor Francis. 2018, 43, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zang, C.; Tian, S.; Liu, J.; Yang, H.; Jia, S.; You, L.; Liu, B.; Zhang, M. Water conservancy projects in China: Achievements, challenges and way forward. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwatari, M.; Nagata, K.; Matsubayashi, M. Evolution of Water Governance for Climate Resilience: Lessons from Japan’s Experience. Water 2025, 17, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S. Urban water crisis and the promise of infrastructure: A case study of Shimla, India. Front. Water 2023, 5, 1051336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, Z. Population Urbanization and Urban Water Security in China: Challenges for Sustainable Development Under SDGs Framework. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 4458–4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, M.; Otsuki, K.; Zoomers, A.; Kaag, M. Sustainable Urbanization on Occupied Land? The politics of infrastructure development and resettlement in Beira city, Mozambique. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamani, K. The roles of adaptive water governance in enhancing the transition towards ecosystem-based adaptation. Water 2023, 15, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Xie, J.; Jiao, T.; Su, Z. Research on the livelihood capital and livelihood strategies of resettlement in China’s South-to-North Water Diversion Middle Line Project. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1396705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odume, O.N.; Onyima, B.N.; Nnadozie, C.F.; Omovoh, G.O.; Mmachaka, T.; Omovoh, B.O.; Uku, J.E.; Akamagwuna, F.C.; Arimoro, F.O. Governance and institutional drivers of ecological degradation in urban river ecosystems: Insights from case studies in African cities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, M.; Cox, M.E. Collaboration, adaptation, and scaling: Perspectives on environmental governance for sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens, R.; Shah, E.; Bruins, B. Contested knowledges: Large dams and mega-hydraulic development. Water 2019, 11, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M.M. The risks and reconstruction model for resettling displaced populations. Soc. Dev. World Bank 2021, 25, 235–264. [Google Scholar]

- Hoominfar, E.; Radel, C. Contested dam development in Iran: A case study of the exercise of state power over local people. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, G.; Urban, F.; Tan-Mullins, M.; Mohan, G. Large dams, energy justice and the divergence between international, national and local developmental needs and priorities in the global South. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 41, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, B. Dam Building by the Illiberal Modernisers: Ideology and Changing Rationales in Rwanda and Tanzania; The University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven, H. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam: Africa’s Water Tower, Environmental Justice & Infrastructural Power. Daedalus 2021, 150, 159–180. [Google Scholar]

- Käkönen, M.; Nygren, A. Resurgent dams: Shifting power formations, persistent harms, and obscured responsibilities. Globalizations 2023, 20, 866–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Bastidas, J.P.; Boelens, R. The Political Construction and Fixing of Water Overabundance: Rural–Urban Flood-Risk Politics in Coastal Ecuador, in Rural–Urban Water Struggles; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; pp. 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Helmcke, C. Technology of detachment: The promise of renewable energy and its contentious reality in the south of Colombia. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2023, 41, 976–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Huang, J.; Wang, W. The sustainable development assessment of reservoir resettlement based on a BP neural network. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.; Cashore, B. The dependent variable problem in the study of policy change: Understanding policy change as a methodological problem. J. Comp. Policy Anal. 2009, 11, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Glob. Environ. Change 2009, 19, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimble, M.; Olivier, T.; Anjos, L.A.P.; Tadeu, N.D.; Giordano, G.; Mac Donnell, L.; Laura, R.; Salvadores, F.; Santana-Chaves, I.M.; Torres, P.H.; et al. How do basin committees deal with water crises? Reflections for adaptive water governance from South America. Ecol. Soc. 2022, 27, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lu, J.; Chen, S. A Study on the Evolution and Interrelation of China’s Reservoir Resettlement Policies over 75 Years. Water 2025, 17, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Shi, G.; Dong, Y. Effects of the post-relocation support policy on livelihood capital of the reservoir resettlers and its implications—A study in Wujiang sub-stream of Yangtze river of China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Vanclay, F.; Yu, J. Evaluating Chinese policy on post-resettlement support for dam-induced displacement and resettlement. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2021, 39, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heming, L.; Waley, P.; Rees, P. Reservoir resettlement in China: Past experience and the Three Gorges Dam. Geogr. J. 2001, 167, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, S.R.; Riddell, E.; du Toit, D.R.; Retief, D.C.; Ison, R.L. Toward adaptive water governance: The role of systemic feedbacks for learning and adaptation in the eastern transboundary rivers of South Africa. Ecol. Soc. 2023, 28, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengberg, A.; Gustafsson, M.; Samuelson, L.; Weyler, E. Knowledge production for resilient landscapes: Experiences from multi-stakeholder dialogues on water, food, forests, and landscapes. Forests 2020, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lei, X.; Qiao, Y.; Kang, A.; Yan, P. The water status in China and an adaptive governance frame for water management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2085. [Google Scholar]

- DeCaro, D.A.; Chaffin, B.C.; Schlager, E.; Garmestani, A.S.; Ruhl, J.B. Legal and institutional foundations of adaptive environmental governance. Ecol. Soc. A J. Integr. Sci. Resil. Sustain. 2017, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadri, M.; Aristidou, A.; Ravasi, D. Cross-Sector Partnership Research at Theoretical Interstices: Integrating and Advancing Theory across Phases. J. Manag. Stud. 2025, 62, 484–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras, G.L.; Stringer, L.C.; Quinn, C.H. Corruption and conflicts as barriers to adaptive governance: Water governance in dryland systems in the Rio del Carmen watershed. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 660, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorth, P.; Madani, K. Adaptive water management: On the need for using the post-WWII science in water governance. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 37, 2247–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, C.; Carney, D. Sustainable Livelihoods: Lessons from Early Experience; Department for International Development London: London, UK, 1999; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones, I. Livelihoods Perspectives and Rural Development, in Critical Perspectives in Rural Development Studies; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; pp. 159–184. [Google Scholar]

- Karki, S. Sustainable livelihood framework: Monitoring and evaluation. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Manag. 2021, 8, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepkoech, W.; Mungai, N.W.; Stöber, S.; Lotze-Campen, H. Understanding adaptive capacity of smallholder African indigenous vegetable farmers to climate change in Kenya. Clim. Risk Manag. 2020, 27, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, T. Avoiding new poverty: Mining-induced displacement and resettlement. Min. Miner. Sustain. Dev. 2002, 58, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Li, J.; Feldman, M. Livelihood adaptive capacities and adaptation strategies of relocated households in rural China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 1067649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Qiu, X.; Zhu, F.; Hu, T.; Xu, Y. Follow-up supportive policies and risk perception influence livelihood adaptation of anti-poverty relocated households in ethnic mountains of southwest China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yin, K.; Xiao, Y. Impact of farmers’ livelihood capital differences on their livelihood strategies in Three Gorges Reservoir Area. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 103, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottyn, I. Livelihood trajectories in a context of repeated displacement: Empirical evidence from Rwanda. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, N.; Newsham, A.; Rigg, J.; Suhardiman, D. A sustainable livelihoods framework for the 21st century. World Dev. 2022, 155, 105898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Qi, J. Evaluation and Strategic Response of Sustainable Livelihood Level of Farmers in Ecological Resettlement Area of the Upper Yellow River—A Case Study of Liujiaxia Reservoir Area, Gansu Province. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walelign, S.Z.; Lujala, P. A place-based framework for assessing resettlement capacity in the context of displacement induced by climate change. World Dev. 2022, 151, 105777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhou, K.; Chen, X. Influence of livelihood capital of rural reservoir resettled households on the choice of livelihood strategies in China. Water 2022, 14, 4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Liu, H.; Feldman, M.W. Is change of natural capital essential for assessing relocation policies? A case from Baihe county in western China. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2021, 39, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wang, B.; Zhou, K.; Wang, H.; Zeng, Q.; Xu, D. Impact of fiscal expenditure on farmers’ livelihood capital in the Ethnic Minority Mountainous Region of Sichuan, China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Song, N.; Ma, N.; Sultanaliev, A.; Ma, J.; Xue, B.; Fahad, S. An assessment of poverty alleviation measures and sustainable livelihood capability of farm households in rural China: A sustainable livelihood approach. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Xu, M.; Chen, T.; Wang, Y. Factors Affecting Former Fishers’ Satisfaction with Fishing Ban Policies: Evidence from Middle and Upper Reaches of Yangtze River. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ahmed, T. Farmers’ livelihood capital and its impact on sustainable livelihood strategies: Evidence from the poverty-stricken areas of Southwest China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xiang, H.; Zhao, F. Measurement and spatial differentiation of farmers’ livelihood resilience under the COVID-19 epidemic outbreak in rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 166, 239–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Mao, W.; Hu, Z.; Cai, Y.; Xie, N.; Weng, Z. How does livelihood capital influence the green production behaviors among professional grain farmers cultivating high-quality rice? Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1555488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; White, M.J. Internal migration in China, 1950–1988. Demography 1996, 33, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S. Diaspora’s Homeland: Modern China in the Age of Global Migration; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dongen, E. Across the conceptual divide? Chinese migration policies seen through historical and comparative lenses. Third World Q. 2022, 43, 1627–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavkova, M.; Hristova, M.; Stoyanova, P.; Markov, I.; Lero, N.; Borisova, M. Between the Worlds: Migrants, Margins, and Social Environment; Maeva, M., Slavkova, M., Stoyanova, P., Hristova, M., Eds.; IEFSEM-BAS & Paradigma: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2021; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Tadevosyan, G. Returning Migrants in the People’s Republic of China Challenges and Perspectives—Evidence from Chongqing; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, X.; Chen, S.; Sun, J. Role of non-governmental organizations in post-relocation support of reservoir migrations in China: A just transition perspective. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1339953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lin, W.; Li, S.; Ning, Y. Social impacts of dam-induced displacement and resettlement: A comparative case study in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cao, Z.; Zhou, K.; Ji, Y. Research on the relationship between social capital and sustainable livelihood: Evidences from reservoir migrants in the G Autonomous Prefecture, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 11, 1358386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yao, K.; Liu, B.; Zhang, D. Risk Analysis of Reservoir Resettlers with Different Livelihood Strategies. Water 2022, 14, 3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. Social Reconstruction in Dam-Induced Displacement: A Case Study of Four Resettlement Projects on the Lancang River, China. Master’s Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S.; Li, J.; Lo, K.; Guo, H.; Li, C. China’s rapidly evolving practice of poverty resettlement: Moving millions to eliminate poverty. Dev. Policy Rev. 2020, 38, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Targeted poverty alleviation: China’s ingenuity to defeat poverty. Bangladesh J. Public Adm. 2022, 30, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Zhang, F.; Sun, C. Evaluation of sustainable livelihood of reservoir resettlement based on the fuzzy matter-element model. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1224690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y. Sustainable poverty alleviation and green development in China’s underdeveloped areas. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.C. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed; Yale University Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Long, N. Development Sociology: Actor Perspectives; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mainwaring, Ċ. Migrant agency: Negotiating borders and migration controls. Migr. Stud. 2016, 4, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, L.; Freeman, T.; Polzin, A.; Reitz, R.; Croucher, R. Migrant workers navigating the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: Resilience, reworking and resistance. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2024, 45, 653–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleaver, F.; Whaley, L. Understanding process, power, and meaning in adaptive governance. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Understanding the Process of Economic Change, in Worlds of Capitalism; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012; pp. 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.C. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance; Yale University Press: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- He, B. Deliberative culture and politics: The persistence of authoritarian deliberation in China. Political Theory 2014, 42, 58–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Bian, C.; Yang, J. How can public participation improve environmental governance in China? A policy simulation approach with multi-player evolutionary game. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 95, 106782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, Q.; Guo, F.; Wang, H. State-owned equity participation and private sector enterprises’ strategic risk taking: Evidence from China. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2023, 44, 1107–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Scales of Justice: Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Kersting, N. Participatory democracy and sustainability. Deliberative democratic innovation and its acceptance by citizens and German local councilors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortensi, L.E.; Riniolo, V. Do migrants get involved in politics? Levels, forms and drivers of migrant political participation in Italy. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2020, 21, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as freedom. Dev. Pract.-Oxf. 2000, 10, 258. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, T.; Miles, L.; Ying, K.; Yasin, S.M.; Lai, W.T. At the limits of “capability”: The sexual and reproductive health of women migrant workers in Malaysia. Sociol. Health Illn. 2023, 45, 947–970. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, P. Improving the entrepreneurial ability of rural migrant workers returning home in China: Study based on 5675 questionnaires. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 150. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, A.; Pang, G.; Zeng, G. Entrepreneurial effect of rural return migrants: Evidence from China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1078199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, Z. Multidimensional interaction mechanisms between population urbanization and urban environmental carrying capacity: A static, coupling, and dynamic perspective. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2025, 140, 104038. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital, in the Sociology of Economic Life; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, X.; Han, M.; Yang, D. Escaping from the identity enclave: Social inclusion events and floating migrants’ settlement intention in China. Popul. Space Place 2023, 29, e2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Li, Y. Shaping local identity through public health: The role of social integration among new-generation rural migrants in urban China. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, P.; Cao, Q.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Yu, L. The effects of social participation on social integration. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 919592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primary Indicators | Secondary Indicators | Indicator Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Capital | Arable Land Availability | Whether the household has access to cultivable land suitable for farming | Wu et al., 2022; Xiao et al., 2021 [47,48] |

| Cash Crop Cultivation | Whether the household engages in the cultivation of cash crops for income generation | ||

| Usable Water Resources | Whether the household has access to usable water resources for irrigation or fisheries | ||

| Usable Forest and Mountain Areas | Whether the household has access to forest or mountain resources for livelihood purposes | ||

| Physical Capital | Resettlement Housing | Whether the household has been provided with secure resettlement housing | Guo et al., 2022; Su et al., 2021 [49,50] |

| Livestock Ownership | Whether the household owns livestock or has access to grazing land | ||

| Industrial Support | Whether the household has received industrial or production-related government support | ||

| Social Capital | Social Organizations | Whether the household participates in social or community-based organizations | Li et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2025 [8,51] |

| Community Relationships | Whether the household maintains stable relationships with local residents | ||

| Social Networks | Whether the household possesses stable and reliable social networks | ||

| Ethnic Integration | Whether the resettled population is socially accepted by local ethnic groups | ||

| Financial Capital | Income Sources | Whether the household has stable and diversified income sources | He & Ahmed, 2022; Zhao et al., 2023 [52,53] |

| Household Savings | Whether the household maintains a certain level of savings | ||

| Economic Support Policies | Whether the household benefits from governmental financial support policies | ||

| Human Capital | Labor Force | Whether over half of the family members are able-bodied laborers | Zhang et al., 2025 [54] |

| Education Level | Whether children have access to nine-year compulsory education | ||

| Vocational Skills Training | Whether household members have received government-sponsored skills training |

| Primary Indicators | Secondary Indicators | Exploratory Resettlement Stage | Return Migration Stage | Self-Reliance Stage | Economic Revitalization Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Capital | Arable Land Availability | √ | × | √ | √ |

| Cash Crop Cultivation | × | × | √ | √ | |

| Usable Water Resources | × | × | × | √ | |

| Usable Forest and Mountain Areas | × | × | × | √ | |

| Physical Capital | Resettlement Housing | √ | × | √ | √ |

| Livestock Ownership | × | × | √ | √ | |

| Industrial Support | × | × | √ | √ | |

| Social Capital | Social Organizations | × | × | √ | √ |

| Community Relationships | × | × | × | √ | |

| Social Networks | × | × | × | √ | |

| Ethnic Integration | × | × | × | √ | |

| Financial Capital | Income Sources | × | × | × | √ |

| Household Savings | × | × | × | √ | |

| Economic Support Policies | × | √ | √ | √ | |

| Human Capital | Labor Force | × | √ | √ | × |

| Education Level | × | × | × | √ | |

| Vocational Skills Training | × | × | √ | √ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ge, X.; Li, Q.; Chen, S.; Shangguan, Z. Resettlement Governance in Large-Scale Urban Water Projects: A Policy Lifecycle Perspective from the Danjiangkou Reservoir Case in China. Water 2025, 17, 3589. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243589

Ge X, Li Q, Chen S, Shangguan Z. Resettlement Governance in Large-Scale Urban Water Projects: A Policy Lifecycle Perspective from the Danjiangkou Reservoir Case in China. Water. 2025; 17(24):3589. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243589

Chicago/Turabian StyleGe, Xiaocao, Qian Li, Shaojun Chen, and Ziheng Shangguan. 2025. "Resettlement Governance in Large-Scale Urban Water Projects: A Policy Lifecycle Perspective from the Danjiangkou Reservoir Case in China" Water 17, no. 24: 3589. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243589

APA StyleGe, X., Li, Q., Chen, S., & Shangguan, Z. (2025). Resettlement Governance in Large-Scale Urban Water Projects: A Policy Lifecycle Perspective from the Danjiangkou Reservoir Case in China. Water, 17(24), 3589. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243589