1. Introduction

Globally, rainfall-induced landslides pose significant threats to infrastructure and public safety, necessitating a robust understanding of their triggering mechanisms in varied environments [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The critical role of precipitation is evident in the reliance of hazard early warning systems (LEWS) on intensity-duration thresholds [

5], exemplified by the dependence of translational slides in Italy on antecedent cumulative rainfall [

6]. The destabilization process is primarily driven by hydro-mechanical coupling: infiltration increases pore water pressure, reducing effective stress and shear strength [

2]. This mechanism applies to both shallow landslides and deep-seated gravitational slope deformations (DSGSD) under extreme rainfall scenarios [

7]. Crucially, the susceptibility of a slope is modulated by lithological heterogeneity. Specific failure mechanisms include reductions in shear strength parameters in red basalt soils [

2], degradation of mudstone in bedding rock masses [

8], and hydraulic conductivity contrasts at soil-sandstone interfaces [

9]. To capture these complex dynamics, recent studies have adopted advanced modeling techniques. Fluid-solid coupling analysis [

10] and integrated physically based models, such as TRIGRS and Scoops3D [

11], have proven effective for quantifying stability variations. Notably, applications in the southeastern Tibetan region reveal that extreme rainfall events can rapidly reduce slope stability in weathered bedrock. Consequently, accurate landslide prediction requires a holistic approach that accounts for the multifaceted interactions between hydrological forcing, geological structure, and weathering conditions [

3].

Taiwan lies within an active orogenic belt, where the western part is predominantly composed of weak Cenozoic sedimentary strata. Characterized by low cementation and high porosity, these weak rocks, particularly the Cholan and Mushan sandstones, exhibit nonlinear elastic and elastoplastic deformation behaviors that differ significantly from those of hard rocks [

12,

13]. Research indicates that macroscopic mechanical parameters, such as uniaxial compressive strength (UCS) and Young’s modulus, are strongly correlated with petrological characteristics, notably porosity and grain area ratio (GAR) [

14,

15]. Porosity has been identified as the governing factor for UCS, exerting a greater influence than either grain or matrix content [

14]; specifically, UCS demonstrates an inverse relationship with porosity and a direct relationship with GAR [

15]. In addition to their mechanical behavior, Taiwan’s weak sandstones display deleterious engineering properties, including shear dilation, creep, and wetting-induced softening (a reduction in strength upon saturation) [

14]. Furthermore, argillaceous formations such as the Lichi Melange, a product of the Luzon Arc collision, undergo significant degradation due to prolonged exposure to the region’s warm, humid climate [

16]. Although early-stage weathering may yield a temporary increase in strength, continued exposure inevitably compromises material stability [

16]. Given the susceptibility of these poorly cemented, porous lithologies to weathering, elucidating their degradation mechanisms is critical for assessing regional geological hazards, as this material and structural deterioration is a primary driver of landslide potential [

17].

Weathering involves complex chemical processes, such as silicate weathering [

18,

19] and pyrite oxidation [

20,

21]. In active orogenic belts such as Taiwan, high erosion rates can expose sulfide-containing rocks to the surface. Sulfate produced by sulfide oxidation accelerates chemical weathering rates and reduces the shear strength of the rock mass [

1]. Material weathering is also a key indirect factor in earthquake-induced landslides. For example, in the large Donghekou landslide triggered by the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, the combination of slate weathering and liquefaction of the runout path significantly enhanced the mobility of the sliding mass [

22]. In non-seismic scenarios, rainfall infiltration combined with weathering can form preferential failure surfaces at the laterite-sandstone interface, thereby reactivating landslides [

10]. Therefore, in geologically active areas with weak rock, such as Taiwan, studying how weathering degrades rock mass strength and stiffness [

23] provides the scientific basis for assessing long-term slope stability risks.

Rock formations composed of alternating competent and incompetent strata present significant geotechnical challenges due to their heterogeneity [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. The primary instability mechanism is differential degradation, where the weathering of soft lithologies undermines more complex layers, inducing failure modes ranging from rockfalls to DSGSDs [

25,

26,

29,

30]. These failures are frequently triggered by precipitation-induced fluctuations in pore pressure [

27,

30,

31]. Accurate characterization requires a multi-disciplinary approach. Rock mass properties can be estimated using rock mass classifications and field tests. At the same time, Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Structure-from-Motion (UAV-SfM) photogrammetry facilitates the generation of three-dimensional models and remote discontinuity mapping [

26,

27,

32]. Subsurface geometries can be further delineated via geophysical surveys, such as Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT) supported by seismic methods [

30,

33]. Synthesizing these investigations, quantitative stability assessment can be performed through integrated monitoring and numerical modeling [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

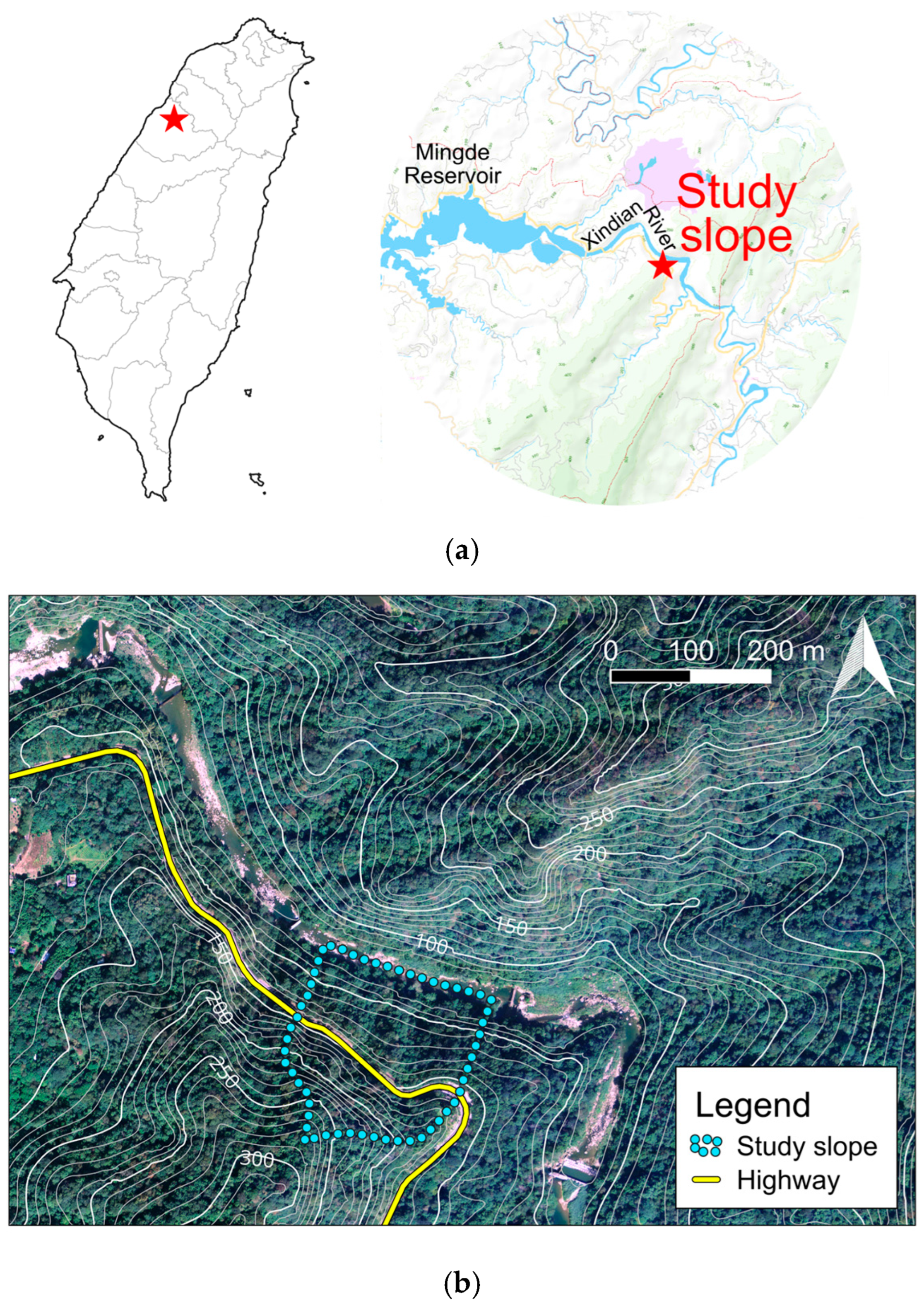

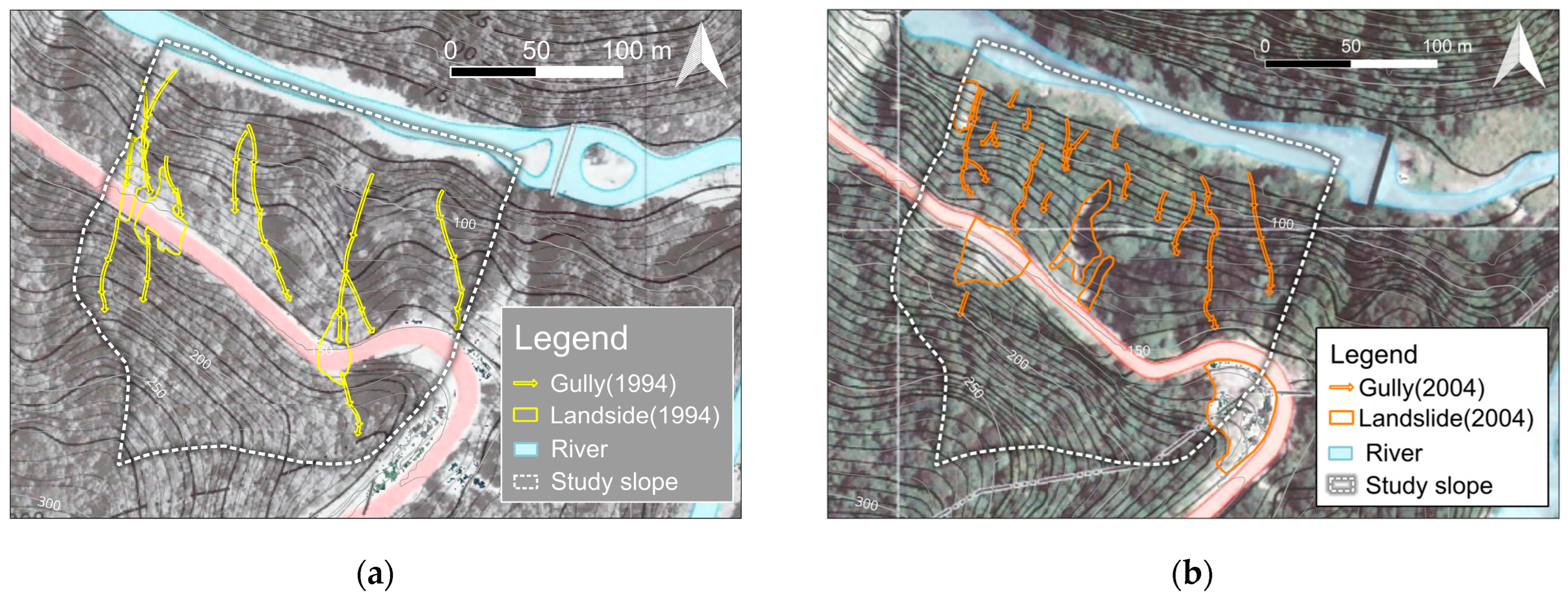

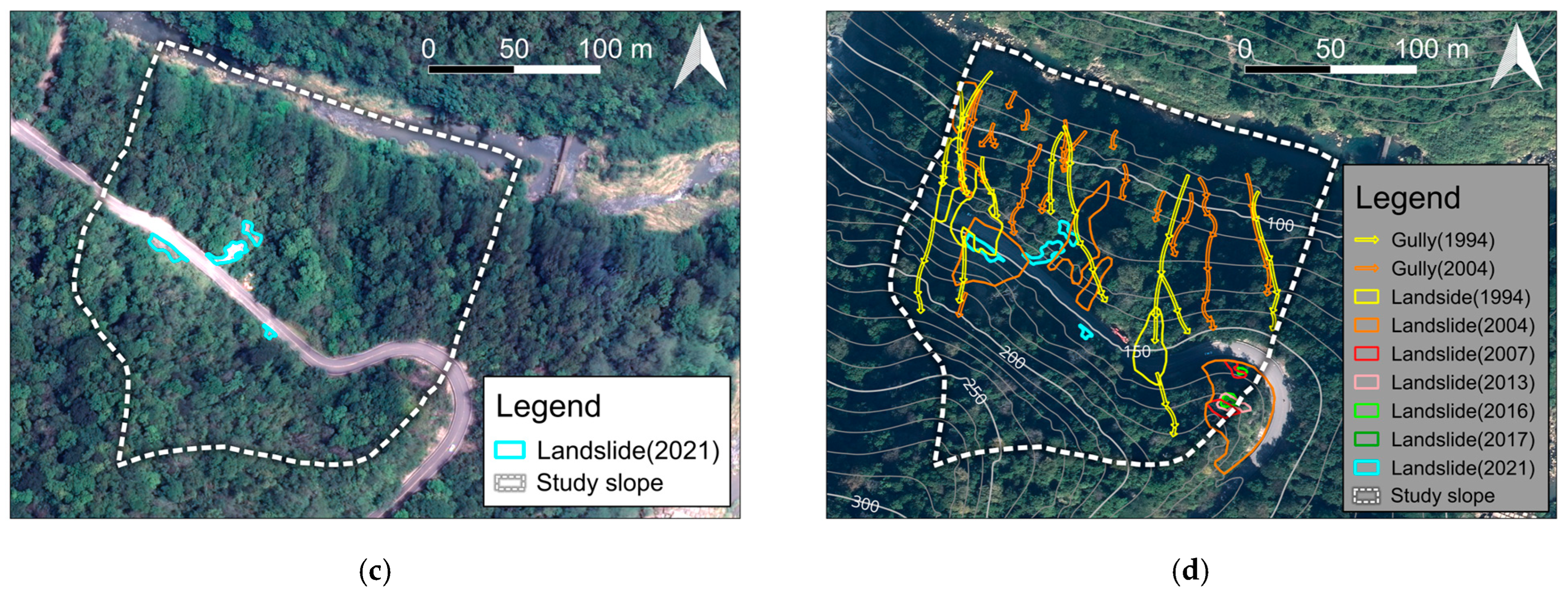

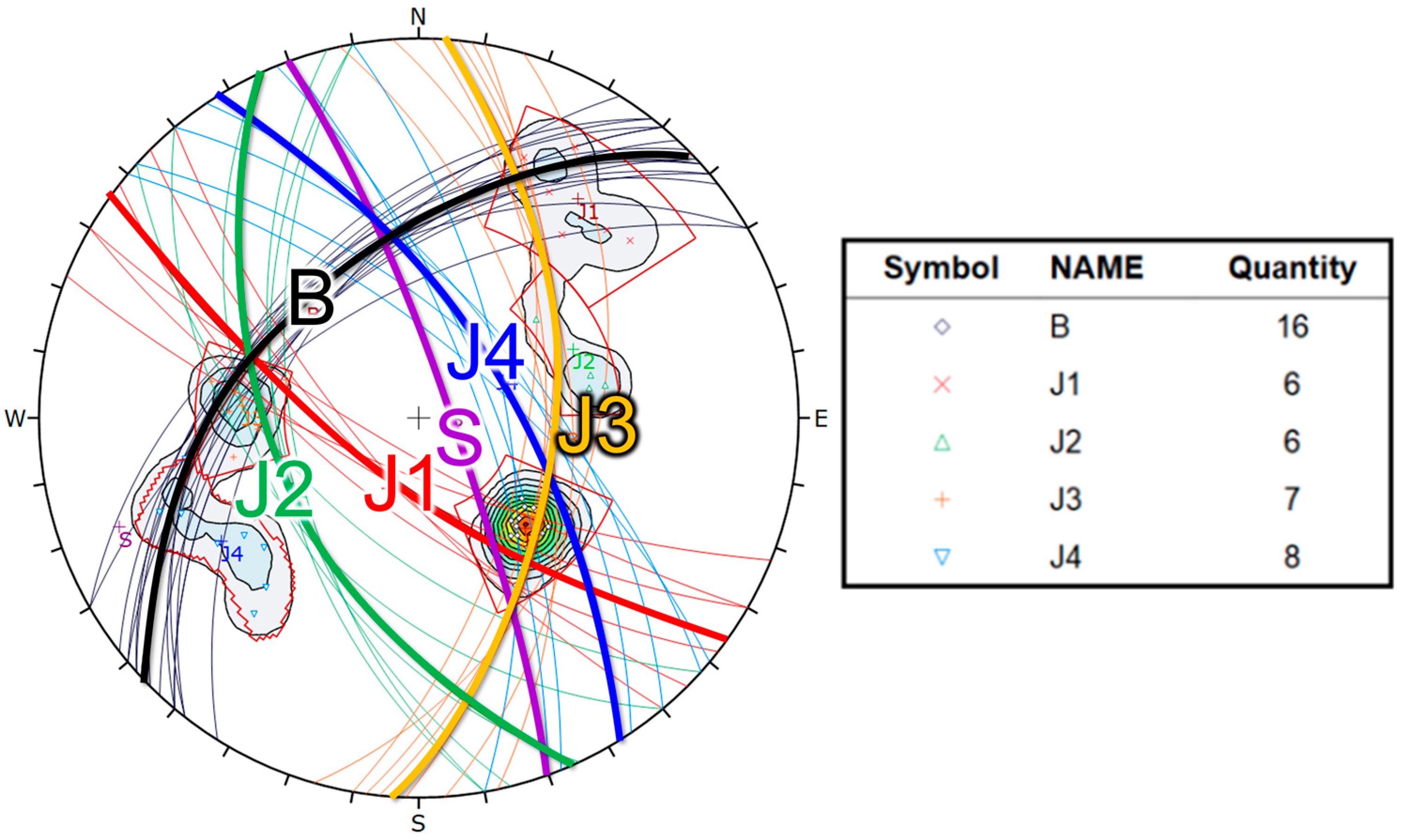

This study focused on sedimentary rock slopes in central Taiwan that have repeatedly collapsed. The study combined remote sensing image interpretation to reconstruct the spatial and temporal distribution of collapses over the years and explore their relationship with rainfall. Based on geological surveys, it was initially concluded that the primary type of slope failure was block movement along discontinuities in the rock mass. At the same time, the collapsing deposits mostly originated from the collapse of highly weathered rock masses. To clarify the mechanism of the disaster, this study conducted discontinuity investigations, photogrammetric mapping, and rock sampling for artificial weathering experiments. The failure mechanism was comprehensively determined based on discontinuity orientation, morphological changes observed in photogrammetric models, and differences in weathering resistance between the interlayered sandstone and shale. Two-dimensional Distinct Element Method (DEM) analysis was then employed to simulate the landslide process, and the results were cross-validated against geomorphological variation data to investigate the causes of collapse in interlayered rock slopes under rainfall-induced differential weathering.

6. DEM Simulations of Landslide Process

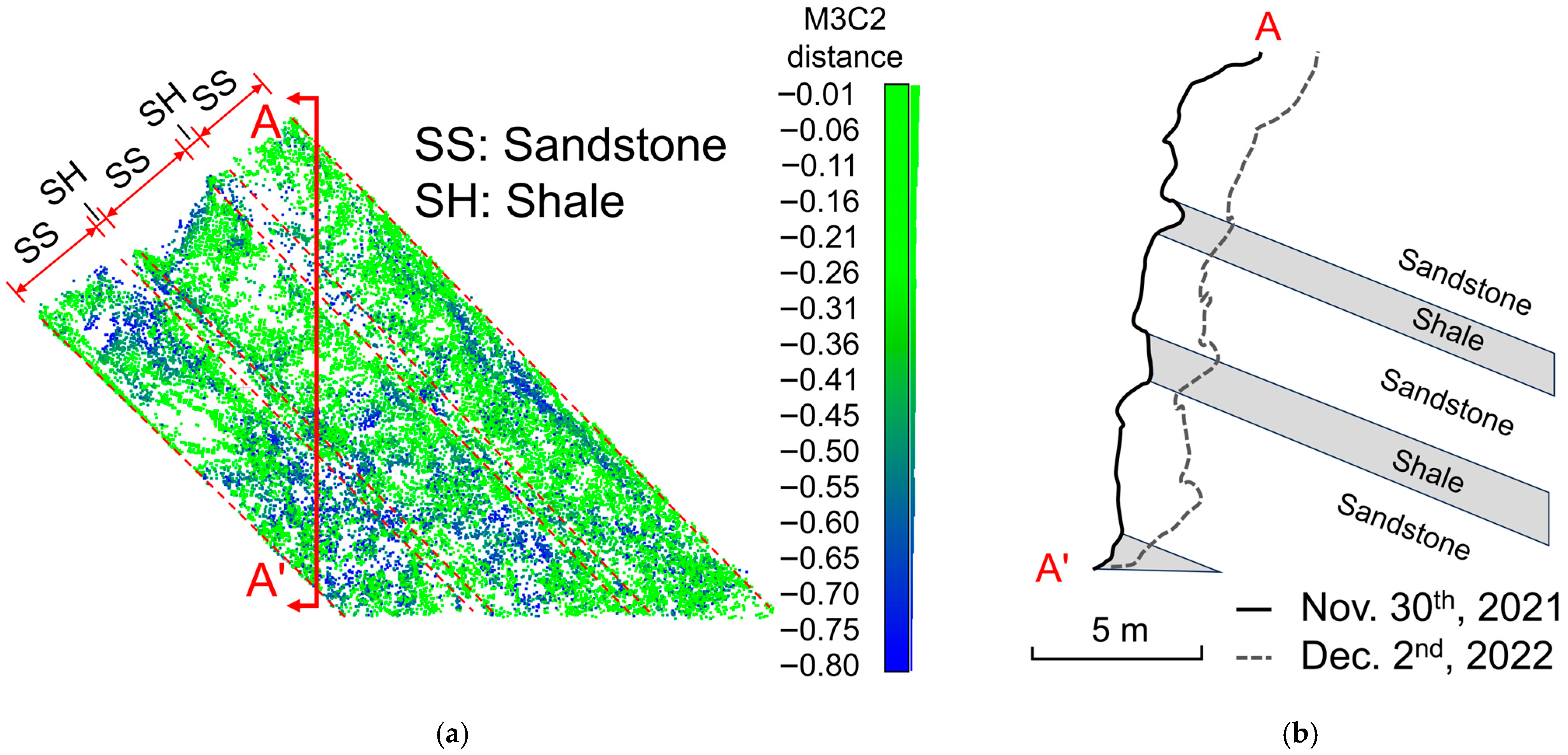

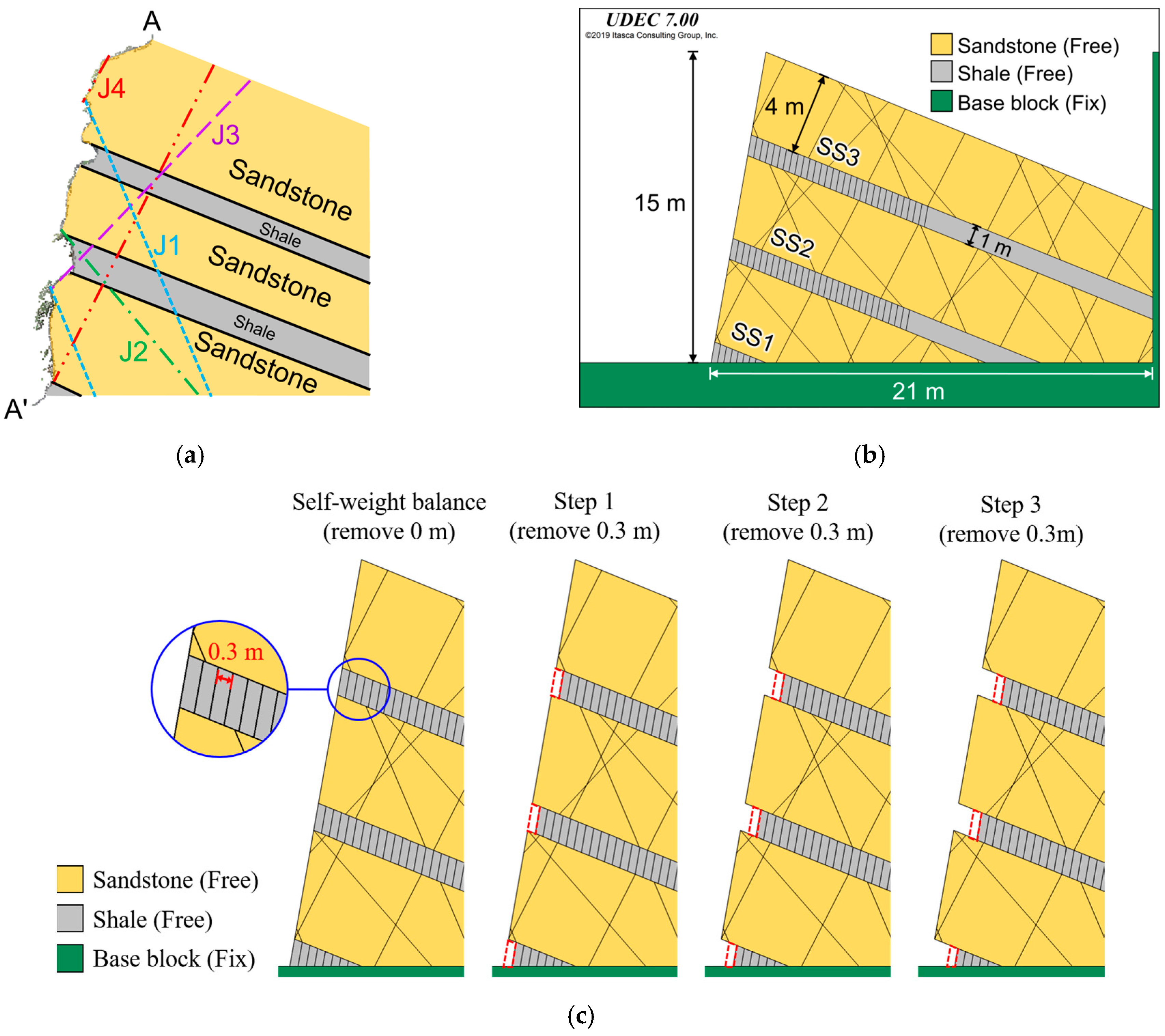

Itasca UDEC was used to assess progressive collapse failure in the study slope. The DEM numerical model is based on a 3D model constructed in November 2021. Section A–A’, where significant differential erosion occurs on the slope, was selected as the basis for model construction (

Figure 9a). The slope bedding planes and joints were extended and simplified based on their orientations measured in the field investigation (

Figure 13a). The model dimensions are 15 m in length and 21 m in width. The yellow blocks in the model represent sandstone with a thickness of 4 m; the gray blocks represent shale with a thickness of 1 m, resulting in a 4:1 sandstone-to-shale thickness ratio; and the green blocks represent the fixed base. To simulate the differential erosion of soft and hard rock layers in interbedded slopes, this study established erosion lines parallel to the slope surface in the shale, thereby simulating the gradual erosion of the weak rock layers over time.

Differential erosion simulation was performed in a staged manner. The distance between erosion lines in shale is 0.3 m (

Figure 13) to create a continuous erosion effect within an acceptable computation time. The simulation is divided into several stages. Stage 0 is a state of self-weight equilibrium. Each subsequent stage removes 0.3 m of shale from the slope. The specific process is as follows: Stage 0, self-weight equilibrium; Stage 1, 0.3 m of erosion; Stage 2, 0.6 m of erosion; Stage 30, 9 m of erosion; and so on. Each stage is calculated until force equilibrium is achieved; once that is achieved, the next stage is simulated. The process is shown in

Figure 13c. During the simulation, the sandstone and shale are free to move without any boundary constraints, while the base rock is restricted in all directions. The physical properties and mechanical properties of intact rocks, and the mechanical parameters of joints, including density, Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, peak and residual friction angle, are based on experimental results [

37] and drilling reports [

38,

39,

40] as listed in

Table 1. Rock materials were assumed to be elastic, and joints were modeled using the Mohr-Coulomb failure criterion, with cohesion neglected. However, the normal stiffness (kn) and shear stiffness (ks) of discontinuities are difficult to determine; therefore, they are estimated using the recommended equations by Itasca (2019) [

41]. First, the Rock Mass Rating estimation in the field investigation yields an average value of 49.8, corresponding to a Modulus Reduction Factor (MRF) of 0.18 according to Singh (1979) [

42].

: Young’s modulus of rock masses;

: Young’s modulus of rock material.

Normal stiffness of joints was derived after Equation (2) [

39] and Equation (3):

where s: spacing,

: shear modulus of rock masses,

: shear modulus of rock material.

Table 1.

Material properties used in the DEM model.

Table 1.

Material properties used in the DEM model.

| Rock Type | Density (kg/m3) 1 | Young’s Modulus (Pa) 1 | Poisson’s Ratio 1 | Normal Stiffness (Pa/m) 2 | Shear Stiffness (Pa/m) 2 | Peak Friction Angle (°) 3 | Residual Friction Angle (°) 3 |

|---|

| Sandstone | 2547 | 7.4 × 109 | 0.33 | 3.6 × 108 | 1.35 × 108 | 32.7 | 27.1 |

| Shale | 2280 | 1.28 × 108 | 0.33 | 6.66 × 107 | 2.5 × 107 | 24.4 | 22 |

Figure 14 illustrates the numerical results for case slope failure due to differential erosion. After each analysis stage, all loose blocks on the slope surface were removed before the next simulation stage. Therefore, the figure only shows the rock blocks that collapsed during that stage.

Figure 14 lists only the stages where failure occurred. From self-weight equilibrium (stage 0) to stage 30, it is found that shale erosion damage causes joints J3 and J4 to form a new slope surface for the next stage. In stage 0, after self-weight equilibrium, the sandstone blocks at the slope toe slid down along J4 due to insufficient support at the bottom, causing a large number of rock blocks above to slide along joints J3 and J4 (

Figure 14a). In stage 1, the slope remains stable (

Figure 14b). In stage 8, after the shale eroded for another 2.1 m compared to stage 1, the rock blocks in the sandstone layer SS1 (see

Figure 13b for location) first rotate outward, causing the rock blocks in SS2 and SS3 that J4 cuts to rotate outward and fall forward (

Figure 13c). In Stage 22, the slope had not yet failed, but the joints between SS2 and SS3 remained open (

Figure 14d). In Stage 24, the sandstone blocks in SS2 topple forward when the underlying shale erodes to within 0.3 m of the joints, causing the rock blocks cut by the joints in SS3 to rotate forward (

Figure 14e). In Stage 29, sandstone blocks in SS2 fell due to the shale erosion, similar to Stage 1 (

Figure 14f).

By observing changes in the sandstone block failure area at each stage and summarizing their regularity, the simulation from self-weight equilibrium to Stage 30 revealed three large collapses with failure areas exceeding 10 m

2. The landslide process shows that the failure phenomena at each stage are closely related to the geometry of the rock blocks cut by the joints. Based on the numerical results and references Cano & Tomás (2013) [

25,

26] and Lin (2019) [

43], the failure modes can be categorized into three: sliding, toppling, and falling. Revised from Line (2019) [

43], block movement of each failure mode can be written as

Figure 15, where sliding contains equal velocity of the top and the bottom edge of the block, toppling involves larger velocity in the top edge than the bottom edge and falling refers to movement with higher vertical velocity than horizontal velocity. Based on the categorization, it is found that a collapse event usually begins with the toppling of sandstone blocks above shale layers, such as blocks 1 and 3, but sometimes with a sliding block, like block 6 (

Figure 14c). Toppling occurs when the line of gravity of the rock block passes beyond the toe of its base because of shale erosion. Rock blocks taking J3 or J4 as their inner boundary should overcome the shear strength along this surface to initiate sliding, as in block 10 in

Figure 14c,d. Some blocks consist of both toppling and sliding. Block 2 slides along the interface between blocks 1 and 2 as it topples. As blocks detach completely from the slope surface, falling begins.

Therefore, the initial failure in the simulation is often triggered by instability at the toe of the sandstone block, which in turn causes the rock blocks in the middle and upper parts of the slope to fail. As erosion deepens, the center of gravity of the rock slope gradually shifts upward, transforming into a failure mode dominated by the middle sandstone block.

7. Discussion

Rainfall and landslide records show a strong correlation between these two. Over the past 12 years, all landslides on the case slope have occurred during the rainy season. Although the rock mass after the slope collapse was only slightly to moderately weathered, the remaining colluvial deposits on the slope surface are the result of highly weathered rock mass, indicating that when weathering reaches a certain level, a landslide will occur. Results from artificial weathering tests show that the average UCS of shale decreased continuously from 24.5 MPa to 7.31 MPa, representing a 70.16% decrease. The average UCS of sandstone decreased from an initial 49.1 MPa to a minimum of 30.91 MPa, before ultimately returning to 50.72 MPa. This is likely due to uneven initial weathering grade within the collected rock samples. In particular, the point load tests required small, individual samples weighing approximately 400–600 g, making them susceptible to localized heterogeneity and property variation. The sandstone has only slightly degraded following artificial weathering experiments; therefore, an average UCS across all 80 cycles was calculated at 43.87 MPa, which is considered the strength after weathering. This represents a 10.65% decrease compared to the initial strength of 49.10 MPa. Comparing the strength reduction ratios of sandstone and shale, the weathering strength reduction ratio of sandstone to shale is approximately 1:6.6. This ratio is considered the weathering resistance ratio of sandstone to shale.

Since considering sandstone weathering in the UDEC simulation would make the model too complicated, the numerical model only considered shale weathering. Therefore, the numerical collapse volume was added to the sandstone weathering volume, and the three-dimensional collapse volume was corrected based on the width of the comparison range. The collapse volume of the two-point cloud variations was 258 m

3. During the simulation process, the sandstone collapse areas at Steps 8 and 24 were 34.8 m

2 and 23.9 m

2, respectively. The shale weathering erosion at the time of collapse was 2.4 m

2 and 4.8 m

2. Using the sandstone-to-shale weathering rate ratio and the rock layer thickness, the sandstone weathering areas were calculated to be 1.45 m

2 and 2.91 m

2. The corrected numerical collapse areas, after totaling, were 38.65 m

2 and 31.61 m

2. The collapse area of profile A–A’ from photogrammetric DSMs is 34.53 m

2 (

Figure 10b). Hence, the simulated collapse areas are 1.12 and 0.92 times the actual collapse area, accounting for 8–12% error.

Kinematic analysis results show four potential failure modes for the case slope: plane failure, wedge failure, direct overturning, and flexural overturning (

Figure 8). The UDEC analysis results (

Figure 14) show plane failure along J3 and J4, direct toppling of the rock block with J3 and J4 as the base, and flexural toppling of the rock block with J2 as the boundary. Wedge failure, in which the rock block slips along the intersection of two weak planes, is challenging to observe in two-dimensional analysis. In addition to wedge failure, the other failure modes identified in the kinematic analysis are also observed in the UDEC simulation. The slope stability degrades gradually in three steps: shale erosion, sandstone blocks losing stability, and collapse. According to DEM analysis, toppling is the dominant failure mode in the collapse of the study slope, followed by sliding and falling. Toppling, however, occurs when shale erosion exposes the block’s line of gravity. One step before collapse, there are always erosions more than half the spacing of J4 (hereafter denoted as S4), as shown in

Figure 16a,b. To obtain a quantitative measure of shale erosion leading to collapse, the outlines before and after a collapse are compared in

Figure 17. Until the collapse in step 8, a critical erosion of 2.71 m occurs, equivalent to 0.78S

4 (

Figure 17a). The other two collapses occur at shale erosion levels of 3.16 m and 1.42 m, corresponding to 0.91S

4 and 0.41S

4, respectively (

Figure 17b,c). Exclude the local collapse in step 29, the critical erosion is approximately higher than 0.75S

4. It is fair to replace S

4 with the spacing of the release joint or tension cracks that grow parallel to the slope surface. To estimate the critical erosion of an interbedded slope, key factors include joint orientation, joint spacing, joint shear strength, and the weathering resistance of intact rock.

Although the numerical results provide an accurate estimation of the collapse amount for Profile A–A’, many aspects must be considered when extending to a broader range. For instance, current numerical analysis assumes that all discontinuities are 100% persistent, that the rock mass is homogeneous, and that discontinuity orientations are consistent. However, discontinuities are often not completely fractured but instead partially connected by rock bridges, which provide additional strength, unlike in numerical models. These rock bridges significantly enhance the slope’s stability. The weather conditions differ from the surface to the interior of the slope, making the exterior part more vulnerable. Therefore, failure may occur at the boundary between different weather conditions within a rock block, rather than at its boundaries, and result in less collapse. Variation in the orientations of discontinuities is also inherent. However, the mean vector directions of each set of discontinuities are used to generate the DEM model, producing a representative estimate of the slope failure and amount. There is also a difference between two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) analysis. In 2D analysis, a profile of the slope was taken as the representative. But from

Figure 10a, it is clear that the collapse areas are unevenly distributed, and that a simple estimate of the 3D collapse volume by multiplying the 2D collapse area by the slope width can produce considerable error. The error arises from the assumption that all joints along the slope width extend infinitely, with a relative geometry consistent with the slope surface; this implies that all discontinuities are parallel to the slope surface but differ only in dip, which is inconsistent with the actual 3D situation. For this case, a reduction factor of 0.44–0.63 should be taken to obtain an acceptable estimation of 3D collapse volume. Based on the results, this study concludes that UDEC has made a significant contribution to the analysis of the failure mechanism and stability assessment in this case. The failure of the slope in this case was primarily due to the toppling of the sandstone after the loss of the supporting shale layer, as well as to sliding at the interface between the sandstone and shale layers and at other intersecting joint lines. The occurrence of collapse also has a specific periodic pattern.

8. Conclusions

To clarify the mechanism of the collapse of interbedded sandstone and shale slopes in central Taiwan, this study investigated the connection between rainfall records and collapse events. From the slope’s appearance, the case exhibited significant patterns of block movement. The rock layers were relatively young Taiwanese sedimentary rocks characterized by poor cementation and susceptibility to wetting–softening. This study investigated potential failure modes by examining discontinuity orientations and conducting kinematic analysis. Photogrammetry was used to construct two three-dimensional models of the case, during which multiple collapses occurred. Geomorphological changes before and after the collapses revealed an inward retreat of 0.01–0.80 m in the lower slope. To quantify the weathering rates of sandstone and shale under rainfall, rock samples were collected from the site and subjected to an artificial weathering experiment designed using temperature and humidity records from a nearby meteorological station. The rock specimens were subjected to cycles of high temperature and low humidity, followed by low temperature and high humidity. The change in the uniaxial compressive strength of the two rock types with the number of weathering cycles indicated a weathering rate ratio of 6.6:1 between shale and sandstone.

Kinematic analysis revealed four potential failure modes: planar failure, wedge failure, direct toppling, and flexural toppling. Each failure type contained multiple sets of catastrophic joints, resulting in a diverse group of unstable rock blocks. The DEM model, based on a cross-sectional analysis of the case study, considered the process by which sandstone blocks in a sandstone-shale interbedded slope destabilize due to continuous shale weathering and rainfall-induced erosion. This type of landslide follows three steps: shale erosion, sandstone blocks lose stability, and collapse. The block movement includes sliding, toppling, and falling. Although the appearance of the slope surface remains similar over time, the amount of shale erosion can serve as an indicator of a landslide. As the slope is about to collapse, shale erosion reaches 0.78 to 0.91 times the spacing of the joint that is approximately parallel to the slope surface. But the values still vary according to joint orientation, joint spacing, joint shear strength, and the weather resistance of intact rock.

The DEM-simulated failure mechanism broadly matched the kinematic analysis results, detailing the sliding and toppling of sandstone blocks along the joints after shale erosion, and presenting good agreement with the 2D-actual collapse area. Transforming the 2D collapse area to the 3D collapse volume, one needs to multiply the numerical collapse area by the width of the extent, 17 m, and by a reduction factor of 0.44 to 0.63. This difference is due to the DEM’s assumption of complete joint continuity, whereas rock bridges are actually present in the site’s joints. The heterogeneity from degrees of weathering and the inherent randomness of joint orientation also contribute to the difference. In practical applications, the reduction factor between the 2D-estimated and the 3D-actual collapse volume should be determined for each case. In general, this study investigated a typical landslide case controlled by rainfall-induced shale weathering, revealed the failure modes of rock blocks, and proposed a quantitative index of critical erosion to identify collapses.