Application of the Self-Organizing Map (SOM) Algorithm to Identify Hydrochemical Characteristics and Genetic Mechanism of High-Nitrate Groundwater in Baoding Area, North China Plain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting

3. Samples and Method

3.1. Samples

3.2. Self-Organizing Map

3.3. Human Health Risk Assessment

4. Results

4.1. SOM Clustering Results

4.2. Hydrochemical Results

5. Discussion

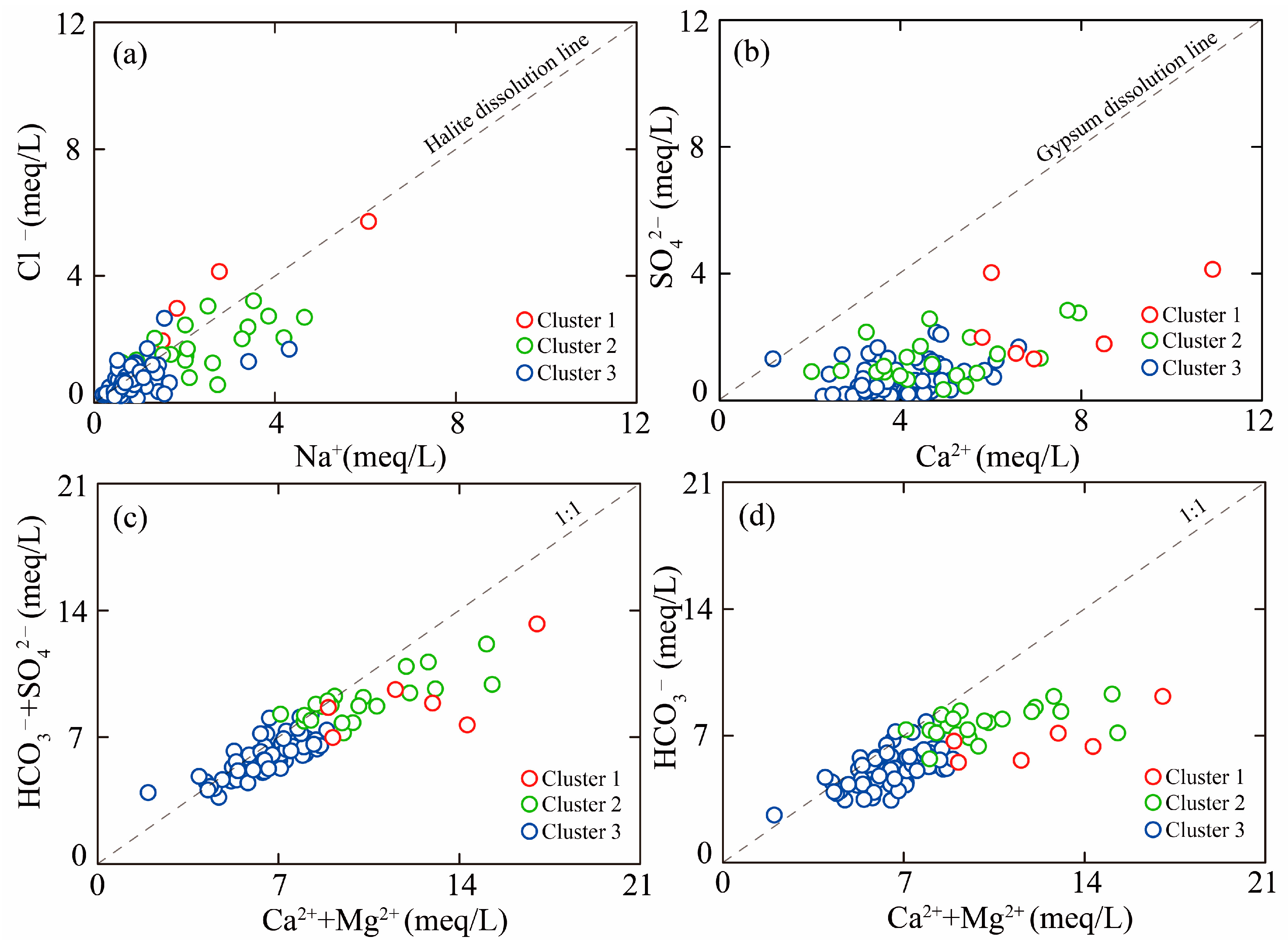

5.1. Hydrochemical Driven Factors

5.2. Identifying Nitrate Sources

5.3. HHRA Results

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The SOM analysis effectively categorized 91 samples into three distinct clusters with markedly different physicochemical characteristics. Cluster 1 (6.59% of samples) is characterized by the highest concentrations of NO3− (exceeding permissible limits), Ca2+, and TDS, suggesting a high degree of mineralization and nitrate pollution. In contrast, Cluster 3 (70.33% of samples) represents the largest group and exhibits the lowest levels of NO3−, Ca2+, HCO3−, and TDS. Cluster 2 (23.08% of samples) presents an intermediate signature with elevated Na+, Mg2+, and HCO3−. The statistical data and supporting figures collectively affirm these hydrochemical characteristics, which are predominantly HCO3-Ca and HCO3-Mg types for Clusters 1 and 2, and HCO3-Ca for Cluster 3.

- (2)

- The NO3− concentrations in the 91 shallow groundwater samples range from below the detection limit to 68.0 mg/L, with a mean value of 9.59 mg/L. Notably, 30.43% of the samples surpassed the anthropogenic pollution threshold of 10 mg/L, indicating significant anthropogenic influence. Molar ratio analyses further reveal that agricultural activities are the primary source of NO3−, supplemented by contributions from domestic sewage.

- (3)

- Utilizing high-nitrate groundwater for long-term consumption presents a potential health hazard. The assessment reveals a discernible pattern in non-carcinogenic risk: children are at the highest risk, followed by adult females and then adult males. The elevated risk for children is directly linked to their lower body weight and heightened sensitivity of their developing metabolic processes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Machiwal, D.; Jha, M.K.; Singh, V.P.; Mohan, C. Assessment and mapping of groundwater vulnerability to pollution: Current status and challenges. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 185, 901–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Huang, F.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, F.; Guan, X. Effects of norfloxacin on nitrate reduction and dynamic denitrifying enzymes activities in groundwater. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 273, 116492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yi, L. Hypoxia exerts greater impacts on shallow groundwater nitrogen cycling than seawater mixture in coastal zone. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 43812–43821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, E.-H.; Lee, K.-K.; Moon, S.; Koh, H.-J. Site-specific management of nitrate contamination based on groundwater flow system characterization in two agricultural areas of Jeju volcanic island, South Korea. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 391, 126359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, T.; Fiasca, B.; Di Camillo Tabilio, A.; Murolo, A.; Di Cicco, M.; Galassi, D.M.P. The weighted Groundwater Health Index (wGHI) by Korbel and Hose (2017) in European groundwater bodies in nitrate vulnerable zones. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 116, 106525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Qian, H. Groundwater nitrate response to hydrogeological conditions and socioeconomic load in an agriculture dominated area. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez-Osuna, F.; Álvarez-Borrego, S.; Ruiz-Fernández, A.C.; García-Hernández, J.; Jara-Marini, M.E.; Bergés-Tiznado, M.E.; Piñón-Gimate, A.; Alonso-Rodríguez, R.; Soto-Jiménez, M.F.; Frías-Espericueta, M.G.; et al. Environmental status of the Gulf of California: A pollution review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2017, 166, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Ye, H.; Shi, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, R.; Cai, Y.; Li, J.; Li, F.; Jin, Z. Using PCA-APCS-MLR model and SIAR model combined with multiple isotopes to quantify the nitrate sources in groundwater of Zhuji, East China. Appl. Geochem. 2022, 143, 105354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khebudkar, A.; Sohoni, M. Estimation of Nitrate Concentration in Groundwater Source Using Zonal Nitrate Balance Method in Male Village of Western Maharashtra. In Geoenvironmental Engineering; Agnihotri, A.K., Reddy, K.R., Bansal, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M. A simple and effective approach to investigate the dominant contaminant sources and accuracy in water quality estimation through Monte Carlo simulation, Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs), and GIS machine learning methods. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 171, 113188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, K.; Wang, L.; Zhu, W.; Deng, Y.; Yu, C. Identifying the Hydrochemical Characteristics and Genetic Mechanism of Medium-Low Temperature Fluoride-Enriched Geothermal Groundwater in the Hongjiang—Qianshan Fault of Jiangxi Province. Rock Miner. Anal. 2024, 43, 568–581. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, S.; Qi, Z.; Hao, Q.; Wang, L.; Luo, Y.; Yin, S. Numerical investigation of groundwater flow systems and their evolution due to climate change in the arid Golmud river watershed on the Tibetan Plateau. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 943075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Cao, M.; Liu, P. Development and utilization of geothermal energy in China: Current practices and future strategies. Renew. Energy 2018, 125, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Y.; Liu, K.; Wan, L.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhang, S.C.; Jia, W.H.; Yue, X.R.; Bu, G.Y. Hydrochemical characteristics and genetic mechanisms of mid-low temperature geothermal fluids in the eastern segment of the Xinquan—Wentang Fault Zone, Jiangxi Province. Acta Geosci. Sin. 2025; in press. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Shi, Z.; Liang, X.; Wang, G.; Han, J. Multiple factors control groundwater chemistry and quality of multi-layer groundwater system in Northwest China coalfield—Using self-organizing maps (SOM). J. Geochem. Explor. 2021, 227, 106795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liao, F.; Wang, G.; Qu, S.; Mao, H.; Bai, Y. Hydrogeochemical evolution induced by long-term mining activities in a multi-aquifer system in the mining area. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.K.; Du, R.H.; Guo, F. Implication of self-organizing map, stable isotopes combined with MixSIAR model for accurate nitrogen control in a well-protected reservoir. Environ. Res. 2024, 248, 118335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, S.; Liang, X.; Liao, F.; Mao, H.; Xiao, B.; Duan, L.; Shi, Z.; Wang, G.; Yu, R. Geochemical fingerprint and spatial pattern of mine water quality in the Shaanxi-Inner Mongolia Coal Mine Base, Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Zhu, S.; Li, J.; Liu, W.; Li, Z.; Sun, Z.; Liu, C. Hydrochemical characteristics and source identification of nitrate in surface water and shallow groundwater in the Poyang Lake Basin, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Wang, G.; Rao, Z.; Liao, F.; Shi, Z.; Huang, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y. Deciphering spatial pattern of groundwater chemistry and nitrogen pollution in Poyang Lake Basin (eastern China) using self-organizing map and multivariate statistics. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 329, 129697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohonen, T. Self-organized formation of topologically correct feature maps. Biol. Cybern. 1982, 43, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Ministry of Health. Control Criteria for Endemie Fluorosis Areas; National Disease Control and Prevention Administration: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund, Volume 1, Human Health Evaluation Manual. Part E (Supplemental Guidance for Dermal Risk Assessment); EPA/540/R/99/005; Office of Superfund Remediation and Technology Innovation: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. Drinking Water Standards Health Advisories Office of Water; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- USGS. National Water Summary 190-1991 Stream Water Quality; USGs Water Supply; United States Geological Survey (USGS): Reston, VA, USA, 1993; p. 59.

- WHO. WHO Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- Deng, Y.; Ye, X.; Du, X. Predictive modeling and analysis of key drivers of groundwater nitrate pollution based on machine learning. J. Hydrol. 2023, 624, 129934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, C.N.; Subramani, T.; Kumar, G.R.S.; Soundaranayaki, K. Nitrate pollution index and age wise health risk appraisal for the Pambar River basin in south India. Environ. Geochem. Health 2025, 47, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, O.; Richards, K.G.; Kirwan, L.; Khalil, M.I.; Healy, M.G. Factors affecting nitrate distribution in shallow groundwater under a beef farm in South Eastern Ireland. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 3135–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yang, Y.; Shi, M.; Lu, Y.; Chen, W. Hydrogeochemical and machine learning evidences for release and attenuation mechanisms of chromium contamination in a partially PRB remediation of shallow groundwater. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 385, 127109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Gao, H.; Zhu, M.; Yu, M.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, M.; Su, J.; Xi, B. Spectral and molecular insights into the characteristics of dissolved organic matter in nitrate-contaminated groundwater. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 355, 124202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Cao, W.G.; Pan, D.; Wang, S.; Ren, Y.; Li, Z.Y. Distribution and origin of high arsenic andfuoride in groundwater of the North Henan Plain. Rock Miner. Anal. 2022, 41, 1095–1109. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaandorp, V.P.; Broers, H.P.; van der Velde, Y.; Rozemeijer, J.; de Louw, P.G.B. Time lags of nitrate, chloride, and tritium in streams assessed by dynamic groundwater flow tracking in a lowland landscape. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 3691–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, K.; Amano, H.; Shinkai, F.; Wakasa, A.; Berndtsson, R. Integrated approach to investigate groundwater nitrate nitrogen pollution and remediation simulation in Shimabara Peninsula, Nagasaki, Japan. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Du, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, X.; Xu, R.; Xiong, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Gan, Y. Source identification of nitrate in groundwater of an agro-pastoral ecotone in a semi-arid zone, northern China: Coupled evidences from MixSIAR model and DOM fluorescence. Appl. Geochem. 2024, 175, 106197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Alfio, M.R.; Fiorese, G.D.; Balacco, G. Identification of potential causes of nitrate pollution in three apulian aquifers (Southern Italy). Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2025, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Unit | Children | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral reference dose for NO3− (RfDoral) | mg/(kg × day) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Gastrointestinal absorption factor (ABSgi) | - | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Drinking rate (IR) | L/day | 0.7 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Exposure frequency (EF) | days/year | 365 | 365 | 365 |

| Exposure duration (ED) | years | 6 | 30 | 30 |

| Average body weight (BW) | kg | 15 | 55 | 75 |

| Average time (AT) | days | 2190 | 10,950 | 10,950 |

| Skin permeability (Ksp) | cm/h | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Contact duration (T) | h/d | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Exposure frequency of daily dermal contact (EV) | - | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Unit conversion factor (CF) | L/cm3 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Skin surface area (Sa) | - | 6597.01 | 15,475.85 | 18,742.36 |

| Average body height (H) | cm | 99.4 | 153.4 | 165.3 |

| Clusters | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DBI | NaN * | 0.9898 | 0.8418 | 0.8946 | 0.9126 |

| pH | TDS | K+ | Ca2+ | Na+ | Mg2+ | HCO3− | SO42− | Cl− | NO3− | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | mg/L | ||

| Cluster 1 | Max | 7.3 | 1172 | 5.9 | 218.0 | 140.0 | 88.3 | 559.0 | 197.0 | 203.0 | 68.0 |

| Min | 7.0 | 527 | 0.6 | 116.0 | 14.7 | 30.7 | 337.0 | 61.4 | 27.5 | 9.7 | |

| Ave | 7.2 | 719 | 3.2 | 149.0 | 52.5 | 58.3 | 412.3 | 116.5 | 98.9 | 34.8 | |

| SD | 0.1 | 220 | 2.1 | 35.5 | 42.4 | 20.0 | 74.0 | 56.1 | 61.4 | 21.3 | |

| Cluster 2 | Max | 7.7 | 1128 | 1.8 | 159.0 | 162.0 | 88.0 | 567.0 | 135.0 | 358.0 | 36.8 |

| Min | 7.1 | 457 | 0.2 | 40.7 | 13.9 | 47.6 | 349.0 | 15.2 | 19.2 | 2.1 | |

| Ave | 7.3 | 609 | 0.7 | 95.9 | 60.0 | 65.5 | 469.2 | 62.5 | 77.7 | 12.6 | |

| SD | 0.2 | 151 | 0.4 | 30.2 | 33.9 | 14.0 | 51.1 | 34.7 | 67.5 | 8.9 | |

| Cluster 3 | Max | 8.1 | 487 | 6.6 | 132.0 | 99.2 | 52.5 | 475.0 | 103.0 | 94.8 | 20.0 |

| Min | 7.2 | 219 | 0.2 | 23.3 | 4.4 | 9.6 | 161.0 | 4.6 | 5.7 | 0.0 | |

| Ave | 7.5 | 351 | 1.4 | 80.4 | 18.2 | 29.7 | 312.7 | 33.6 | 25.3 | 6.2 | |

| SD | 0.2 | 64 | 1.0 | 19.5 | 12.7 | 9.7 | 62.0 | 24.0 | 15.2 | 4.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, J.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S. Application of the Self-Organizing Map (SOM) Algorithm to Identify Hydrochemical Characteristics and Genetic Mechanism of High-Nitrate Groundwater in Baoding Area, North China Plain. Water 2025, 17, 3517. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243517

Gao J, Zhao J, Yang Y, Zheng J, Wang Z, Liu S, Zhang S. Application of the Self-Organizing Map (SOM) Algorithm to Identify Hydrochemical Characteristics and Genetic Mechanism of High-Nitrate Groundwater in Baoding Area, North China Plain. Water. 2025; 17(24):3517. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243517

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Jue, Jianqing Zhao, Yang Yang, Jun Zheng, Zhiguang Wang, Shurui Liu, and Shouchuan Zhang. 2025. "Application of the Self-Organizing Map (SOM) Algorithm to Identify Hydrochemical Characteristics and Genetic Mechanism of High-Nitrate Groundwater in Baoding Area, North China Plain" Water 17, no. 24: 3517. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243517

APA StyleGao, J., Zhao, J., Yang, Y., Zheng, J., Wang, Z., Liu, S., & Zhang, S. (2025). Application of the Self-Organizing Map (SOM) Algorithm to Identify Hydrochemical Characteristics and Genetic Mechanism of High-Nitrate Groundwater in Baoding Area, North China Plain. Water, 17(24), 3517. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243517