Utilizing Geoparsing for Mapping Natural Hazards in Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

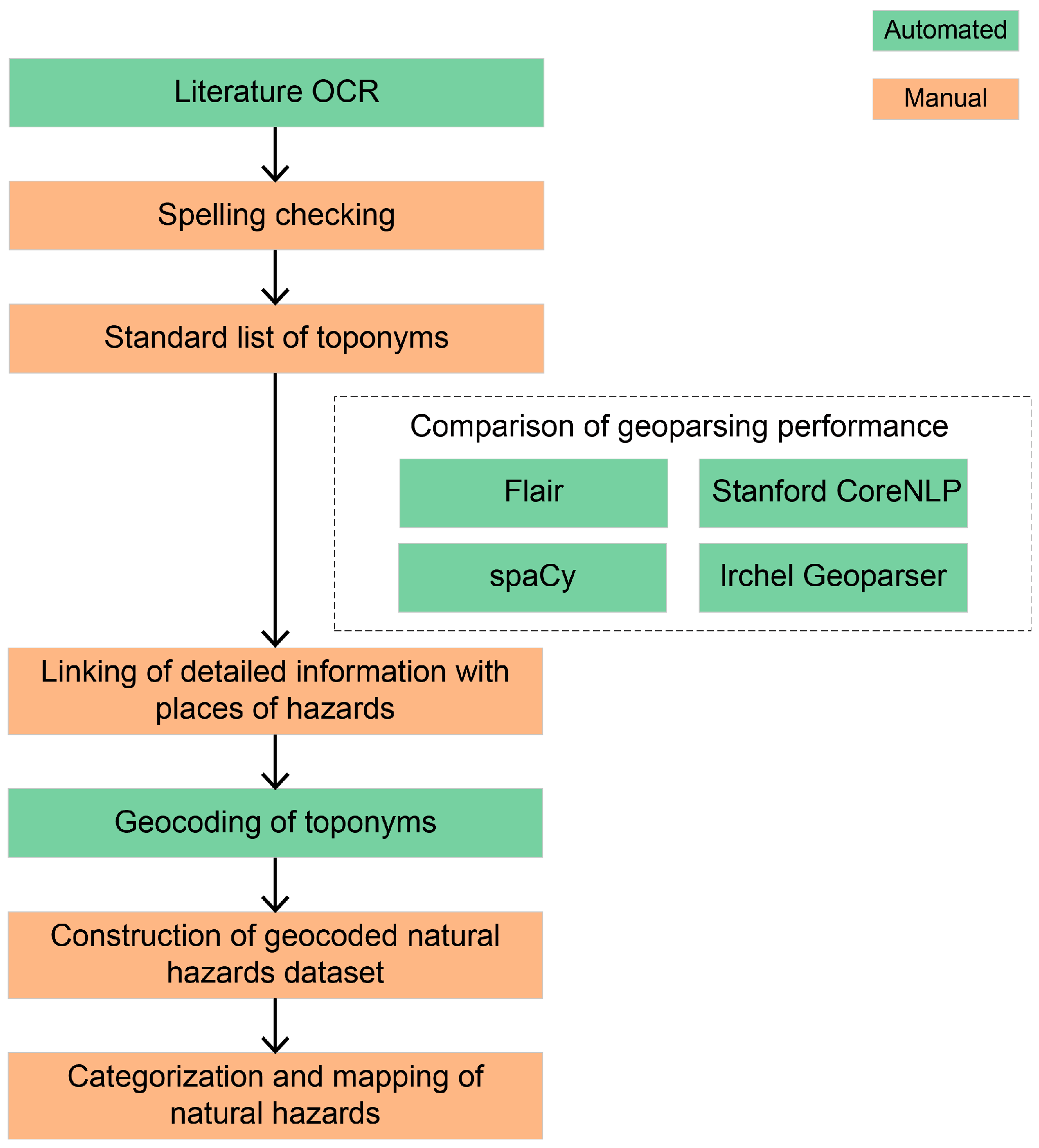

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Preprocessing

2.2. Establishment of Standard Location List and Natural Hazard Dataset

2.3. Evaluation of Toponym NER Performance

2.4. Natural Hazard Data Description and Spatial–Temporal Analysis

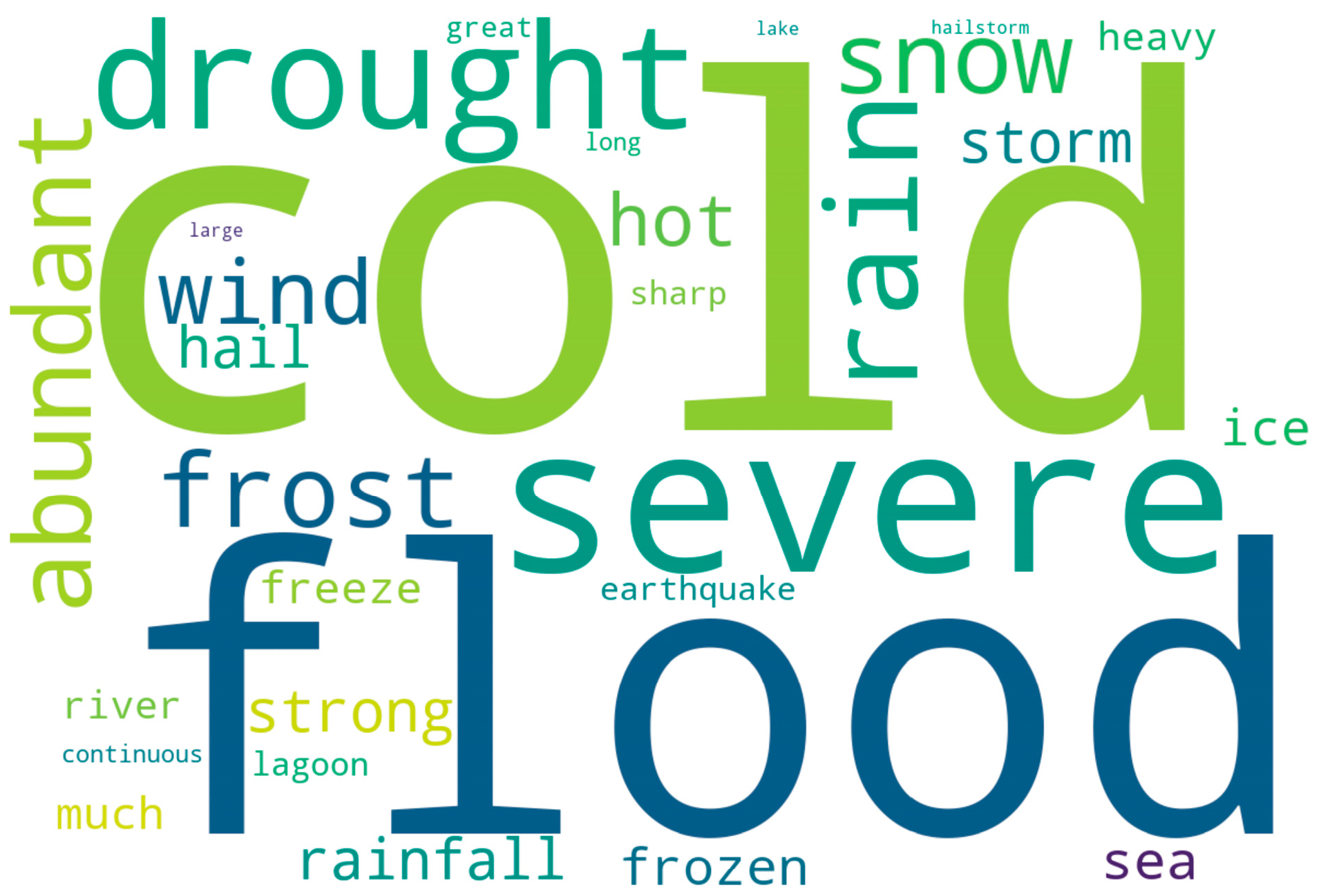

2.5. Natural Hazard Categorization

3. Results

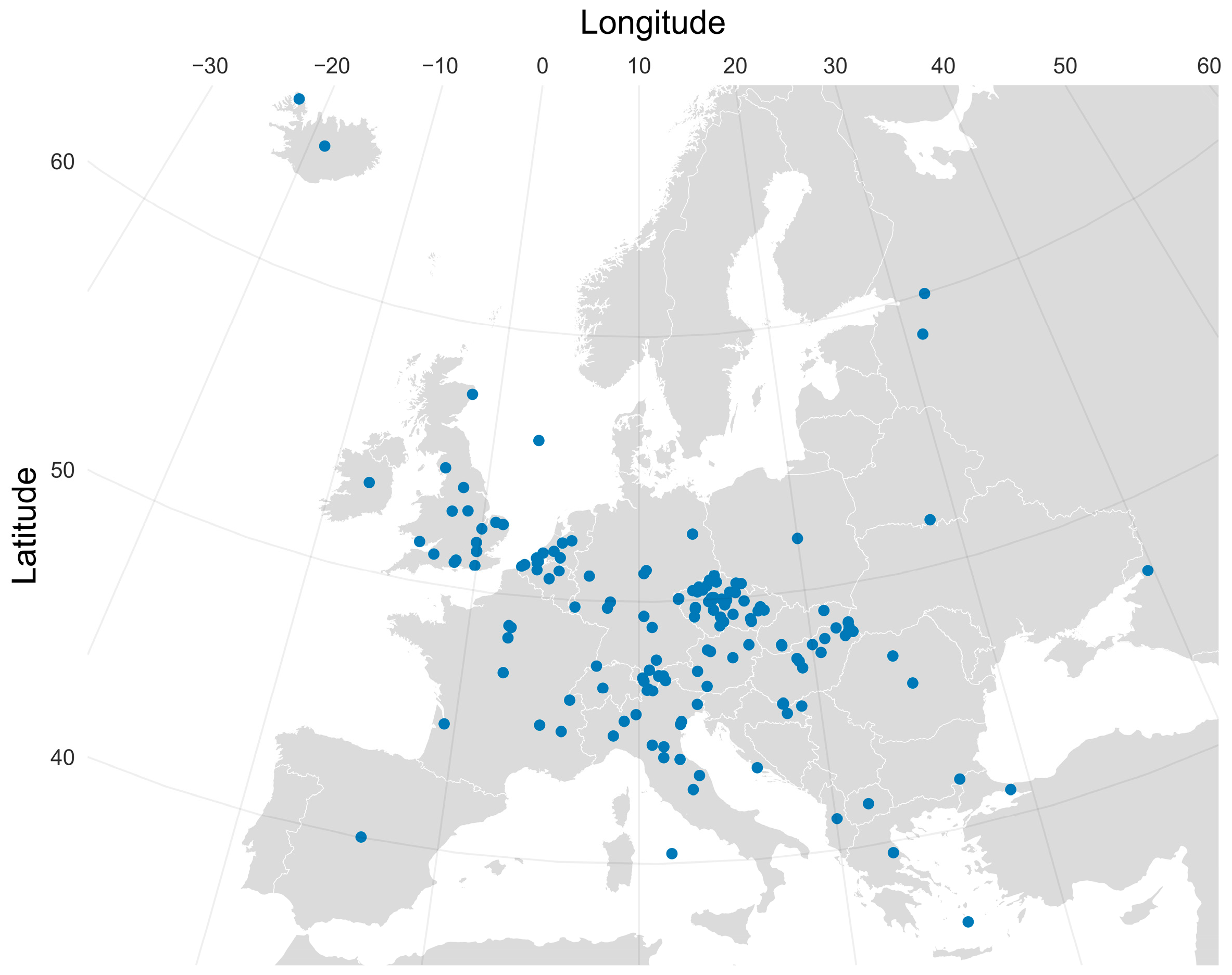

3.1. Standard Location List

3.2. Toponym NER Performance Evaluation

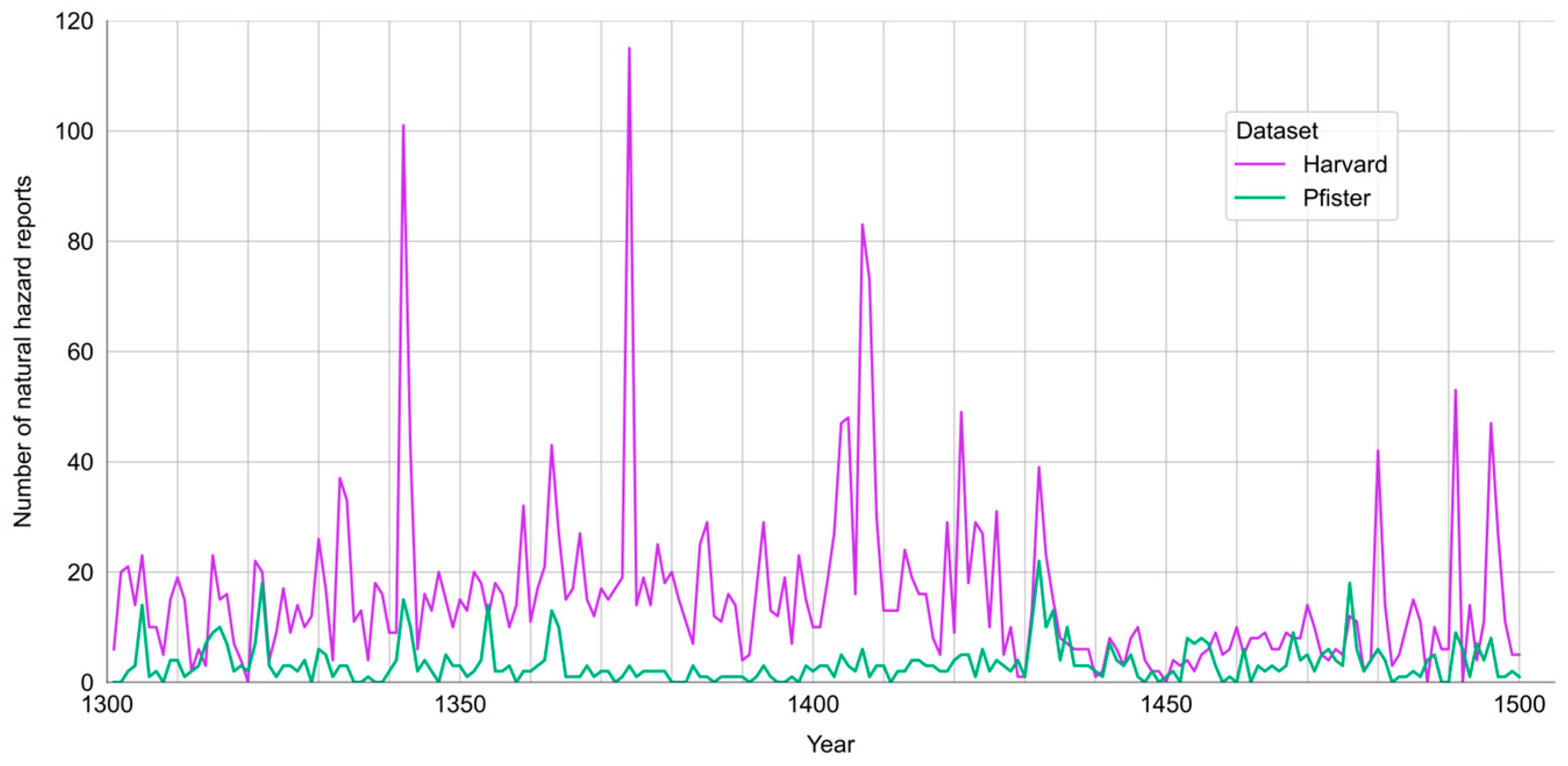

3.3. Description of Natural Hazard Datasets

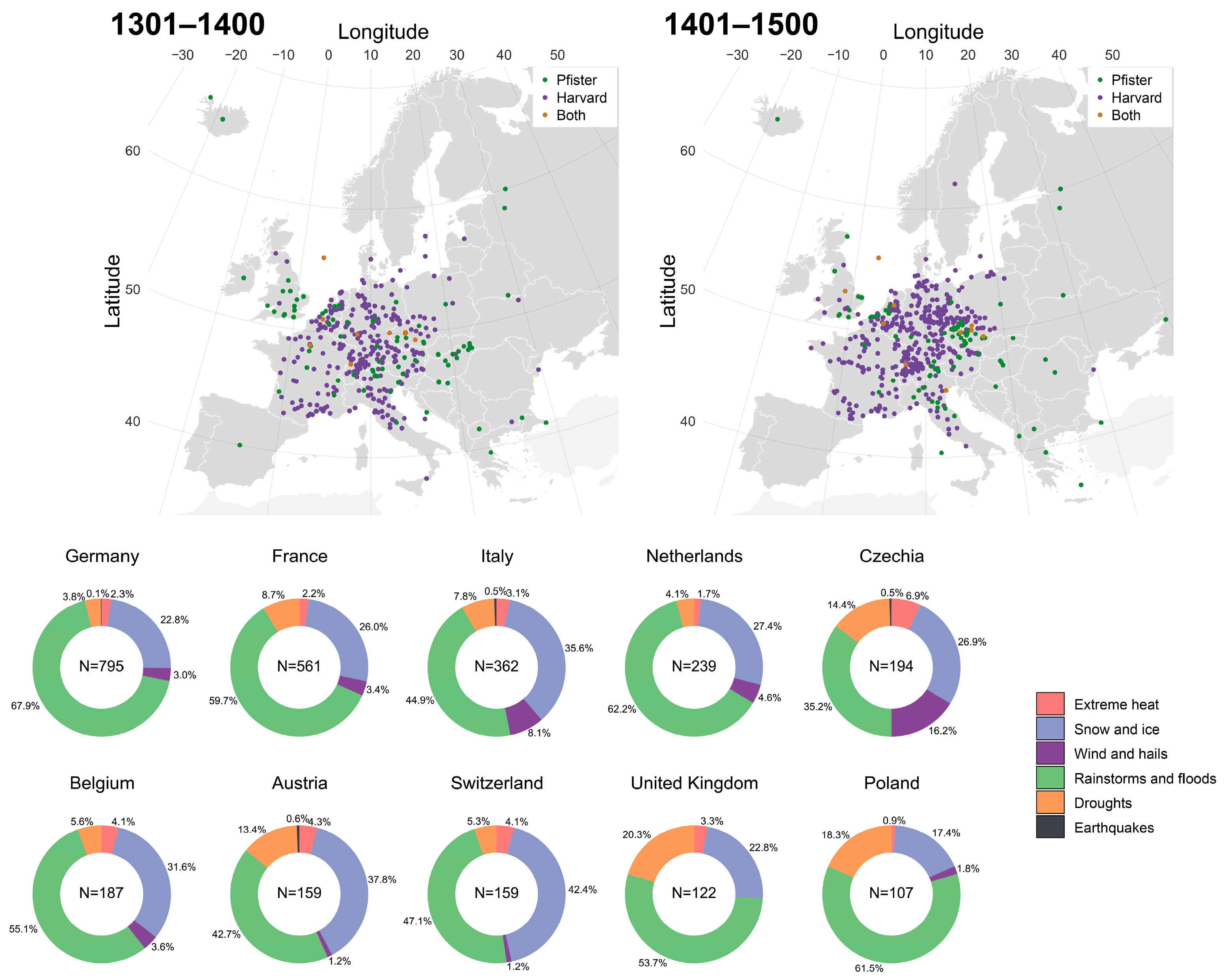

3.4. Spatial–Temporal Characteristics of Natural Hazards

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| NER | Named Entity Recognition |

| OCR | Optical Character Recognition |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| POS | Part Of Speech |

| CRF | Conditional Random Field |

| BiLSTM | Bi-directional Long Short-Term Memory |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CRIAS | Climate Reconstruction and Impacts from the Archives of Societies |

References

- White, S.; Pei, Q.; Kleemann, K.; Dolák, L.; Huhtamaa, H.; Camenisch, C. New perspectives on historical climatology. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2023, 14, e808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, R.W.; Ausubel, J.H.; Berberian, M. Climate Impact Assessment: Studies of the Interaction of Climate and Society; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1985; pp. 319–343. [Google Scholar]

- NatCatSERVICE. Available online: https://www.munichre.com/en/solutions/reinsurance-property-casualty/natcatservice.hsb.html (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Liu, X.; Guo, H.X.; Lin, Y.R.; Li, Y.J.; Hou, J.D. Analyzing Spatial-Temporal Distribution of Natural Hazards in China by Mining News Sources. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2018, 19, 04018006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagl, J.C.; Hattermann, F.F. Impacts of Climate Change on the Hydrological Regime of the Danube River and Its Tributaries Using an Ensemble of Climate Scenarios. Water 2015, 7, 6139–6172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glade, T.; Albini, P.; Francés, F. An introduction to the use of historical data in natural hazard assessment. In The Use of Historical Data in Natural Hazard Assessments, 1st ed.; Glade, T., Albini, P., Francés, F., Eds.; Advances in Natural and Technological Hazards Research; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Han, A.A.; Yuan, W.; Yuan, W.; Zhou, J.W.; Jian, X.Y.; Wang, R.; Gao, X.Q. Mining Spatial-Temporal Frequent Patterns of Natural Disasters in China Based on Textual Records. Information 2024, 15, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgdorf, A.M. A global inventory of quantitative documentary evidence related to climate since the 15th century. Clim. Past 2022, 18, 1407–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Castillo, C.; Diaz, F.; Vieweg, S. Processing Social Media Messages in Mass Emergency: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2015, 47, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimiziarani, M.; Jafarzadegan, K.; Abbaszadeh, P.; Shao, W.Y.; Moradkhani, H. Hazard risk awareness and disaster management: Extracting the information content of twitter data. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 77, 103577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.Q.; Mao, H.N.; Wang, Y.; Rae, C.; Shaw, W. Hyper-resolution monitoring of urban flooding with social media and crowdsourcing data. Comput. Geosci. 2018, 111, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.G.; Engler, D.; Li, X.C.; Hou, J.M.; Wald, D.J.; Jaiswal, K.; Xu, S.S. Near-real-time earthquake-induced fatality estimation using crowdsourced data and large-language models. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 111, 104680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Lin, H. Global Research on Natural Disasters and Human Health: A Mapping Study Using Natural Language Processing Techniques. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2024, 11, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritta, M.; Pilehvar, M.T.; Limsopatham, N.; Collier, N. What’s missing in geographical parsing? Lang. Resour. Eval. 2018, 52, 603–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GeoNames. Available online: http://www.geonames.org (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Brázdil, R.; Kiss, A.; Luterbacher, J.; Nash, D.J.; Řezníčková, L. Documentary data and the study of past droughts: A global state of the art. Clim. Past 2018, 14, 1915–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.K.; Lin, K.-H.E.; Liao, Y.-C.; Liao, H.-M.; Lin, Y.-S.; Hsu, C.-T.; Hsu, S.-M.; Wan, C.-W.; Lee, S.-Y.; Fan, I.C.; et al. Construction of the REACHES climate database based on historical documents of China. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topluoglu, S.; Taylan-Ozkan, A.; Alp, E. Impact of wars and natural disasters on emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1215929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, H.H. Climate Present, Past and Future, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011; Volume 2: Climatic History and the Future, pp. 1–549. [Google Scholar]

- Le Roy Ladurie, E. Times of Feast, Times of Famine: A History of Climate Since the Year 1000; Doubleday and Company, Inc.: Garden City, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Pfister, C.; SchwarzZanetti, G.; Wegmann, M. Winter Severity in Europe: The Fourteenth Century. Clim. Change 1996, 34, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kraker, A.M.J. Storminess in the Low Countries, 1390–1725. Environ. Hist. 2013, 19, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kraker, A.M.J. Reconstruction of Storm Frequency in the North Sea Area of the Preindustrial Period, 1400–1625 and the Connection with Reconstructed Time Series of Temperatures. Hist. Meteorol. 2005, 2, 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- De Kraker, A.M.J. Flood events in the southwestern Netherlands and coastal Belgium, 1400–1953. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2006, 51, 913–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Engelen, A.F.V. Le climat du dernier millénaire en Europe. In L’homme Face au Climat; Bard, É., Ed.; Éditions Odile Jacob: Paris, France, 2006; pp. 319–339. [Google Scholar]

- Camenisch, C. Endless cold: A seasonal reconstruction of temperature and precipitation in the Burgundian Low Countries during the 15th century based on documentary evidence. Clim. Past 2015, 11, 1049–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camenisch, C.; Keller, K.M.; Salvisberg, M.; Amann, B.; Bauch, M.; Blumer, S.; Brázdil, R.; Brönnimann, S.; Büntgen, U.; Campbell, B.M.S.; et al. The 1430s: A cold period of extraordinary internal climate variability during the early Sporer Minimum with social and economic impacts in north-western and central Europe. Clim. Past 2016, 12, 2107–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohr, C. Extreme Naturereignisse im Ostalpenraum: Naturerfahrung im Spätmittelalter und am Beginn der Neuzeit; Böhlau: Köln, Germany, 2007; pp. 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Rohr, C. Measuring the frequency and intensity of floods of the Traun River (Upper Austria), 1441–1574. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2010, 51, 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, G. Schwarzer Himmel—Kalte Erde—Weißer Tod: Wanderheuschrecken, Hagelschläge, Kältewellen und Lawinenkatastrophen im “Land im Gebirge”. Eine kleine Agrar- und Klimageschichte von Tirol; Universitätsverlag Wagner: Innsbruck, Austria, 2010; pp. 363–460. [Google Scholar]

- Pribyl, K. The study of the climate of medieval England: A review of historical climatology’s past achievements and future potential. Weather 2014, 69, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pribyl, K. Farming, Famine and Plague: The Impact of Climate in Late Medieval England; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 97–136, 161–174. [Google Scholar]

- Titow, J.Z. Evidence of Weather in the Account Rolls of the Bishopric of Winchester 1209–1350. Econ. Hist. Rev. 1960, 12, 360–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, W.T.; Ogilvie, A.E.J. Weather Compilations as a Source of Data for the Reconstruction of European Climate during the Medieval Period. Clim. Change 1978, 1, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogilvie, A.E.J.; Farmer, G. Documenting the Medieval Climate. In Climates of the British Isles: Present, Past and Future, 1st ed.; Hulme, M., Barrow, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1997; pp. 112–133. [Google Scholar]

- Brandon, P.F. Late-Medieval Weather in Sussex and Its Agricultural Significance. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1971, 54, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, M. Umweltbeobachtungen oder Ausreden? Das Wetter und seine Auswirkungen in den grundherrlichen Rechnungen des Bischofs von Winchester im 14. Jahrhundert. Z. Hist. Forsch. 2016, 43, 445–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhtamaa, H. Climatic anomalies, food systems, and subsistence crises in medieval Novgorod and Ladoga. Scand. J. Hist. 2015, 40, 562–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brázdil, R.; Kotyza, O. History of Weather and Climate in the Czech Lands I: Period 1000–1500; Geographisches Institut Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule: Zurich, Switzerland, 1995; pp. 224–252. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, A. Floods and weather in 1342 and 1343 in the Carpathian basin. J. Environ. Geogr. 2009, 2, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A.; Nikolić, Z. Droughts, Dry Spells and Low Water Levels in Medieval Hungary (and Croatia) I: The Great Droughts of 1362, 1474, 1479, 1494 and 1507. J. Environ. Geogr. 2015, 8, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D. Freezing of the Venetian Lagoon since the 9th century A.D. in comparision to the climate of western Europe and England. Clim. Change 1987, 10, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauch, M. Der Regen, das Korn und das Salz die Madonna di San Luca und das Wettermirakel von 1433. Quellen Forschungen Aus Ital. Arch. Bibl. 2016, 95, 183–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telelis, I.G. Medieval Warm Period and the Beginning of the Little Ice Age in the Eastern Mediterranean: An Approach of Physicial and Anthropogenic Evidence. In Byzanz als Raum: Zu Methoden und Inhalten der historische Geographie des östlichen Mittelmeerraumes, 1st ed.; Belk, K., Ed.; Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften: Vienna, Austria, 2000; pp. 223–243. [Google Scholar]

- Haldon, J.; Roberts, N.; Izdebski, A.; Fleitmann, D.; McCormick, M.; Cassis, M.; Doonan, O.; Eastwood, W.; Elton, H.; Ladstaetter, S.; et al. The Climate and Environment of Byzantine Anatolia: Integrating Science, History, and Archaeology. J. Interdiscip. Hist. 2014, 45, 113–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klie, J.-C.; Bugert, M.; Boullosa, B.; Eckart de Castilho, R.; Gurevych, I. The INCEpTION Platform: Machine-Assisted and Knowledge-Oriented Interactive Annotation. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING 2018), Santa Fe, NM, USA, 20 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Krauer, F.; Schmid, B.V. Mapping the plague through natural language processing. Epidemics 2022, 41, 100656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbik, A.; Bergmann, T.; Blythe, D.; Rasul, K.; Schweter, S.; Vollgraf, R. FLAIR: An Easy-to-Use Framework for State-of-the-Art NLP. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Demonstrations), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, C.D.; Surdeanu, M.; Bauer, J.; Finkel, J.; Bethard, S.J.; McClosky, D. The Stanford CoreNLP Natural Language Processing Toolkit. In Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations, Baltimore, MD, USA, 3–24 June 2014; pp. 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Honnibal, M.; Montani, I.; Van Landeghem, S.; Boyd, A. spaCy: Industrial-strength Natural Language Processing in Python. Available online: https://github.com/explosion/spaCy (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Spring, N.; Gomes, D. Irchel Geoparser. Available online: https://github.com/dguzh/geoparser (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Alexandre, P. Le Climat en Europe Au Moyen âge: Contribution à L’Histoire Des Variations Climatiques de 1000 à 1425, D’Après Les Sources Narratives de L’Europe Occidentale; De L’École Des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales: Paris, France, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Li, H.; Hu, Y.; Gu, F.; Kersten, J.; Fan, H.; Klan, F. Location Reference Recognition from Texts: A Survey and Comparison. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.D.; Tetreault, J.; Stent, A. It Depends: Dependency Parser Comparison Using A Web-based Evaluation Tool. In Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association-for-Computational-Linguistics (ACS), Beijing, China, 6–11 July 2015; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Akbik, A.; Blythe, D.; Vollgraf, R. Contextual String Embeddings for Sequence Labeling. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Santa Fe, NM, USA, 20–26 August 2018; pp. 1638–1649. [Google Scholar]

- FlairNLP. Available online: https://flairnlp.github.io/docs/tutorial-basics/tagging-entities#list-of-ner-models (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- en_core_web_lg spaCy v3. Available online: https://spacy.io/ (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Gritta, M.; Pilehvar, M.T.; Collier, N. A pragmatic guide to geoparsing evaluation. Lang. Resour. Eval. 2020, 54, 683–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, A.; Oliveira, H.G.; Alves, A.O. Comparing the Performance of Different NLP Toolkits in Formal and Social Media Text. In Proceedings of the 5th Symposium on Languages, Applications and Technologies (SLATE’16), Maribor, Slovenia, 20–21 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, X.; Kubler, S.; Robert, J.; Papadakis, M.; LeTraon, Y. A Replicable Comparison Study of NER Software: StanfordNLP, NLTK, OpenNLP, SpaCy, Gate. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Social Networks Analysis, Management and Security (SNAMS), Granada, Spain, 22–25 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, E.-X.; Jiang, E. Review of Studies on Text Similarity Measures. Data Anal. Knowl. Discov. 2017, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.L.; Liu, Y.R.; Cui, J.; He, H.D. Deep learning-based methods for natural hazard named entity recognition. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Schultz, D.M.; Lyu, H.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, C. Creating a national urban flood dataset for China from news texts (2000–2022) at the county level. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 29, 767–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Luo, L.; Zeng, X.; Han, Z. Fine-tuned BERT-BiLSTM-CRF approach for named entity recognition in geological disaster texts. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camenisch, C.; White, S.; Pei, Q.; Huhtamaa, H. Editorial: Recent results and new perspectives in historical climatology: An overview. Past Global Changes Mag. 2020, 28, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, D.R.; van Bavel, B.; Soens, T. History and the Social Sciences: Shock Therapy with Medieval Economic History as the Patient. Soc. Sci. Hist. 2016, 40, 751–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungqvist, F.C.; Seim, A.; Huhtamaa, H. Climate and society in European history. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2021, 12, e691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauch, M.; Schenk, G.J. The Crisis of the 14th Century: Teleconnections between Environmental and Societal Change? De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Büntgen, U.; Tegel, W.; Nicolussi, K.; McCormick, M.; Frank, D.; Trouet, V.; Kaplan, J.O.; Herzig, F.; Heussner, K.-U.; Wanner, H.; et al. 2500 Years of European Climate Variability and Human Susceptibility. Science 2011, 331, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Temporal Coverage | Hazard Type | Category | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lamb | 1000 B.C.–1850 | Meteorological hazards and geological hazards | Book | [19] |

| Le Roy Ladurie | 1000–1950 | Meteorological hazards and geological hazards | Book | [20] |

| Pfister | 1300–1400 | Low temperature | Journal article | [21] |

| De Kraker | 1400–1953 | Droughts, wind, storms and floods | Journal article | [22,23,24] |

| Van Engelen | 1000–1900 | Floods | Book section | [25] |

| Camenisch | 1399–1498 | Freeze, frost, droughts and floods | Journal article | [26,27] |

| Rohr | 1441–1590 | Floods and earthquake | Journal article and book | [28,29] |

| Jäger | 1250–1900 | Wind and snow | Book | [30] |

| Pribyl | 1256–1448 | Freeze, rain, droughts and floods | Journal article and book | [31,32] |

| Titow | 1209–1350 | Floods and droughts | Journal article | [33] |

| Bell | 950–1500 | Sea ice, floods and droughts | Journal article | [34] |

| Ogilvie | 1200–1430 | Sea ice | Book section | [35] |

| Brandon | 1340–1444 | Heat, severe cold, floods and droughts | Journal article | [36] |

| Schuh | 1300–1400 | Rainstorm and droughts | Journal article | [37] |

| Huhtamaa | 1100–1500 | Heatwave, cold, frost, snow, rainstorms and droughts | Journal article | [38] |

| Brázdil | 974–1500 | Hail, rainstorms, snow, floods and droughts | Book | [39] |

| Kiss | 1307–1507 | Floods and droughts | Journal article | [40,41] |

| Camuffo | 853–1985 | Freeze | Journal article | [42] |

| Bauch | 1432–1433 | Freeze, frost, wind, rainstorm and earthquake | Journal article | [43] |

| Telelis | 803–1470 | Heatwave, cold winter, freeze, snow, rainstorm, floods and droughts | Book section | [44] |

| Haldon | 300–1453 | Heatwave, cold winter, hail, snow, rainstorms, floods and droughts | Journal article | [45] |

| Flair | Stanford CoreNLP | spaCy | Irchel Geoparser | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| model | BiLSTM, CNN, Transformer | CRF | CNN | rule-based/machine learning |

| programing language | Python | Java | Python (Cython for speed) | Python |

| open source | yes | yes | yes | partial |

| community support | active and growing open-source community | large academic and developer user base | large and actively growing open-source community | small community |

| training datasets | CoNLL-2003, OntoNotes | CoNLL-2003 | TIGER, WikiNER | built-in gazetteers covering millions of place names |

| tasks | tokenization, NER, text classification | tokenization, NER, text classification | tokenization, NER, text classification | location recognition |

| language support for NER | English, German, French, Arabic, Danish, Spanish, Dutch, Ukrainian | English, German, French, Arabic, Chinese, Hungarian, Italian, Spanish | English, German, French, Chinese, Danish, Spanish, Dutch, Croatian, Finnish, Ukrainian | English, German, French, Chinese, Danish, Spanish, Dutch, Croatian, Finnish, Ukrainian |

| license | MIT | GNU GPL v3 | MIT | MIT |

| Natural Hazard Type | Triggers in Textual Data |

|---|---|

| Extreme heat | Severe heat, great heat, hot |

| Snow and ice | Severe cold, very cold, heavy snow, snowstorm(s), (strong) freeze, frozen, heavy ice, ice and snow, hoarfrost |

| Wind and hail | Windy, hail, hailstorm(s), wind force n (n > 5) bft |

| Rainstorms and floods | Heavy rain, abundant rain, very rainy, continually rainy, ceaseless rain, flood(s), storm flood, thunderstorm |

| Droughts | Drought(s), severe drought, low water level, low water stage |

| Earthquakes | Earthquake(s), ground shake |

| Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Matthews Correlation Coefficient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flair | 0.997 | 0.98 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| Stanford CoreNLP | 0.996 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| spaCy | 0.992 | 0.50 | 0.62 | 0.64 |

| Irchel Geoparser | 0.995 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, T.; Zhang, X.; Yin, J. Utilizing Geoparsing for Mapping Natural Hazards in Europe. Water 2025, 17, 3520. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243520

Yu T, Zhang X, Yin J. Utilizing Geoparsing for Mapping Natural Hazards in Europe. Water. 2025; 17(24):3520. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243520

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Tinglei, Xuezhen Zhang, and Jun Yin. 2025. "Utilizing Geoparsing for Mapping Natural Hazards in Europe" Water 17, no. 24: 3520. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243520

APA StyleYu, T., Zhang, X., & Yin, J. (2025). Utilizing Geoparsing for Mapping Natural Hazards in Europe. Water, 17(24), 3520. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243520