1. Introduction

Water pollution caused by organic contaminants is one of the major environmental challenges of the modern world. Numerous studies have shown that anthropogenic activities, such as various industries, are primary sources of these pollutants, including pesticides, pharmaceuticals, antibiotics, and dyes [

1,

2]. These pollutants pose a significant risk to human health and the environment, and their increased concentration can lead to various negative effects, such as endocrine disruption, antibiotic resistance, and toxicity to aquatic life [

1,

3]. Dyes and pigment-related water pollution have been a well-researched subject with a vast number of research and review papers published in scientific literature over the past decade and beyond [

4,

5,

6].

Particularly, synthetic dyes, used in various industries such as textiles, paper, and plastics, are persistent chemicals that are often discharged into natural water bodies excessively and without proper treatment [

6]. The largest group, classified by chemical structure, is azo dyes (70%), which, upon reduction under anaerobic conditions, can produce aromatic amines that are toxic and potentially carcinogenic [

3,

7]. These dyes are typically toxic, resistant to degradation, and can accumulate in aquatic environments, where they reduce light penetration and affect photosynthesis [

1]. Moreover, the presence of azo dyes in drinking water can lead to severe health consequences for humans, including allergic reactions and an increased risk of cancer. Azo dyes can undergo photo-oxidation under UV irradiation, resulting in the formation of less hazardous substances through the complete degradation or partial mineralisation. If the irradiation is sufficient, hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and superoxide radicals (•O

2−) generated at the interface of the semiconductor and electrolyte contribute to the mineralisation process [

8]. In this research, the widely used synthetic azo dye Congo red (CR) was selected as a model pollutant. The structure is presented in

Figure 1, and its general properties include toxicity, difficult degradation, the production of toxic by-products, and a negative effect on photosynthesis.

Considering the diversity in dye structures, various methods for their removal from aqueous solutions may be applied. Physical and chemical treatments are the most common methods used for dye degradation and in large-scale water treatment systems, but they often suffer from limitations such as high energy consumption, secondary pollution, or inefficiency in degrading complex dye molecules [

1].

The usual treatments for CR-contaminated water, in laboratory-scale models, include adsorption on materials such as activated carbon [

9], which can achieve high removal efficiencies (up to 90–100% for 50–100 mg L

−1 CR at acidic pH), biosorbents such as modified

Foeniculum vulgare seeds [

10] or other materials [

11]. However, these methods often face challenges related to regeneration and costs. A solution may lie in the application of advanced oxidation processes (e.g., electro-Fenton, photo-Fenton, photocatalysis) that generate reactive •OH radicals, which can degrade CR into less toxic intermediates and subsequently lead to complete mineralisation to H

2O and CO

2 [

12,

13].

Photocatalysis has emerged as a solution that enables the degradation of complex organic pollutants, including dyes, into less harmful or fully mineralised by-products using light-activated catalysts [

14]. There are several advantages, including being environmentally friendly, highly efficient under ambient conditions, the potential for complete degradation of pollutants, and the reusability of catalysts, which may prevent the formation of secondary pollutants [

14]. Despite significant progress in dye degradation using photocatalysis, many conventional materials such as TiO

2, ZnO, and BiVO

4 often have key limitations, including narrow light absorption ranges, high recombination rates of photoinduced charge carriers, and low efficiencies under natural sunlight [

15,

16,

17]. Moreover, the synthesis methods for some high-performance photocatalysts often involve complex energy-consuming processes that restrict large-scale implementation. In many studies, simulated solar light is used under controlled laboratory conditions, which does not fully reflect the variability and intensity of real sunlight exposure [

18,

19]. The next step towards sustainability may be the application of natural sunlight instead of artificial light sources, though this approach has limitations due to variable sunlight intensity and dependence on weather conditions. Nonetheless, it remains an interesting option for the development of low-resource wastewater treatment systems. The efficiency of tungsten-doped TiO

2 nanoparticles under natural sunlight irradiation was similar to the photodegradation of CR under UV light—after 55 min and 40 min, respectively, the photodegradation was almost complete, using 15 mg of catalyst and 30 ppm dye concentration at neutral pH conditions [

20]. Similarly, Cd-sulphide decorated graphene aerogel systems (0.4 g L

−1) degraded nearly 100% of 40 ppm CR within 60 min under the natural sunlight [

21], while mesoporous BiZnO

3/g-C

3N

4 nanocomposite (0.04 g L

−1) achieved the same high efficiency in 20 ppm CR at pH 6, maintaining a high reusability rate over six consecutive cycles [

22]. Other materials were also used in the sunlight degradation of multiple dyes in sunlight-driven photocatalysis, achieving efficiencies over 90%—nanocrystalline Zn

2SnO

4/SnO

2, Ag/Ce-doped ZnO, doped SnO

2/carbon hybrids and more [

23,

24,

25,

26].

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are a class of crystalline materials composed of metal ions/clusters coordinated to organic ligands, which have a large surface area, tuneable porosity, and active sites suitable for catalysis [

27,

28]. Many types of MOFs exhibit semiconductor-like behaviour and can absorb UV light to generate electron–hole pairs [

29]. Certain MOFs, such as UiO-66 (based on Zr clusters), have shown promising photocatalytic activity due to their structural stability and optical properties [

27]. However, its relatively wide band gap (~3.60 eV) [

30,

31] indicates a need for combination with other materials in order to be more efficient, such as in Rhodamine B photodegradation, when 15 mg of UiO-66(Zr) coupled with Bi

2MoO

6 degraded 30 mL of 10 ppm dye solution [

27]. Multiple review papers have been published in recent years that show the effective use of MOFs for the photocatalytic degradation of various dyes, including Congo Red, with reported degradation efficiencies reaching up to 100%, depending on factors such as dye concentration, MOF type, light irradiation, etc. [

29,

32,

33]. For example, mechanosynthesised zinc-based MOFs have demonstrated high photocatalytic efficiency in degrading 100 ppm Congo Red under UV and visible light within 90 min [

19]. Notably, synthetised TMU-6 material achieved complete decolourisation, with a COD reduction of 68.4% after 72 h, which has shown its potential for both colour removal and detoxification in textile wastewater treatment [

19]. Also, ZIF-8/KI-doped TiO

2 composite degraded a 20 ppm CR in 100 mL solution under UV light irradiation, achieving 97% degradation within 40 min using 20 mg of catalyst. The high degradation efficiency (76.42%) was maintained after four reuse cycles in a 30 ppm CR solution [

34].

On the other hand, recently, carbonaceous materials, such as activated carbon (AC) and various other materials (carbon dots, carbon nanotubes/nanofibers, graphene, fullerene, and 3D carbon architectures), have been developed, in addition to sorption, as materials for photocatalysis [

9,

35,

36]. ACs have a large surface area, high porosity, and surface functional groups, which, when combined with various photocatalytic materials, may enhance pollutant–catalyst interactions by posing as electron acceptors and making more electrons and holes available for photocatalysis [

37]. TiO

2/AC composites were obtained by ultrasonic impregnation and applied to the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye. The degradation efficiency of 100 ppm methylene blue reached 99.6% in 100 min, while the high photocatalytic activity was retained over five reuse cycles [

37].

Over the years, multiple studies have included AC composites with different materials for dye removal, including ZnO [

38], the previously mentioned TiO

2 [

37,

39], and MOFs [

40,

41]. MOF/AC composites also have the potential for this synergetic approach. Synergistic interaction may enhance both adsorption and degradation efficiency, which is necessary for future upscale applications. To our knowledge, no research regarding photocatalysis of Congo red dye via UiO-66/AC composite (derived from coconut shells) has been conducted to date.

A recent review by Ullah et al. provides an excellent overview of the current state of MOF/AC composites and their applications [

40]. Most studies have focused on adsorption, gas storage, and other applications, while only a few have investigated the photocatalytic properties of MOF/AC composites. Among them, only one study examined the application of UiO-66 MOF/AC composite for the adsorptive removal of arsenic from aqueous solutions [

42]. Other studies investigated the photocatalytic properties of MOF/AC composites for wastewater remediation, but focused on different types of MOFs instead of UiO-66. Compared to our study, the experimental conditions were completely different, and no one has investigated CR degradation. Mahmoodi et al. [

43] applied an MIL-88(Fe)/AC composite for the removal of Reactive Red 198 dye under UV-light irradiation with the assistance of H

2O

2 and found that the composite exhibited higher removal efficiency than pure MIL-88(Fe) MOF and AC. Govindaraju et al. [

44] utilised a Zn-MOF/AC composite for the removal of Methyl Orange and Brilliant Green dyes under UV-light irradiation. The composite demonstrated higher removal efficiencies (86.4% and 77.5%, respectively) than pure Zn-MOF and AC. Liu et al. [

45] applied an MIL-125(Ti)/AC composite, made with nitrogen- and sulphur-co-doped activated carbon, to remove the antibiotic Tetracycline Hydrochloride using a Xe lamp as the irradiation source. They concluded that all composites showed higher removal efficiencies compared to pure MIL-125(Ti) MOF, achieving a maximum removal rate of 94.62%.

In this work, UiO-66 and activated carbon derived from coconut shells were combined by simple mixing in a mortar at different ratios. This approach was chosen to minimise structural alterations of the MOF during composite synthesis, such as pore destruction, which may occur during more complex synthesis procedures, like solvothermal or hydrothermal methods and to demonstrate that composites suitable for photocatalytic applications can be obtained with simpler processing techniques. Furthermore, this synthesis route offers advantages in terms of scalability and sustainability, as it avoids the use of high energy input, toxic solvents, or complex equipment, while also valorising waste-derived activated carbon as an additional functional material.

This study aims to evaluate the photocatalytic efficiency and reusability of UiO-66 MOF, activated carbon, and their composites for Congo Red dye removal under natural sunlight.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Composite Synthesis

Activated carbon (AC) was obtained from Trayal Corporation in Kruševac, Serbia. Congo red dye (CR), C32H22N6Na2O6S2, was obtained from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

UiO-66 xerogel, denoted as MOF, was synthesised at room temperature by mixing terephthalic acid, zirconium oxychloride octahydrate, and methanol, followed by centrifugation of the resulting white suspension. The product was washed with N,N-dimethylformamide and methanol, then dried at room temperature overnight [

46]. Prior to the experiments, AC was milled for 1 h in a high-energy ball mill with a ball-to-powder ratio of 3:1. MOF and AC were mixed in a porcelain mortar and carefully transferred to transparent glass reagent vessels. Ratios of MOF and AC used for composite synthesis, as well as denoted samples, are presented in

Table 1.

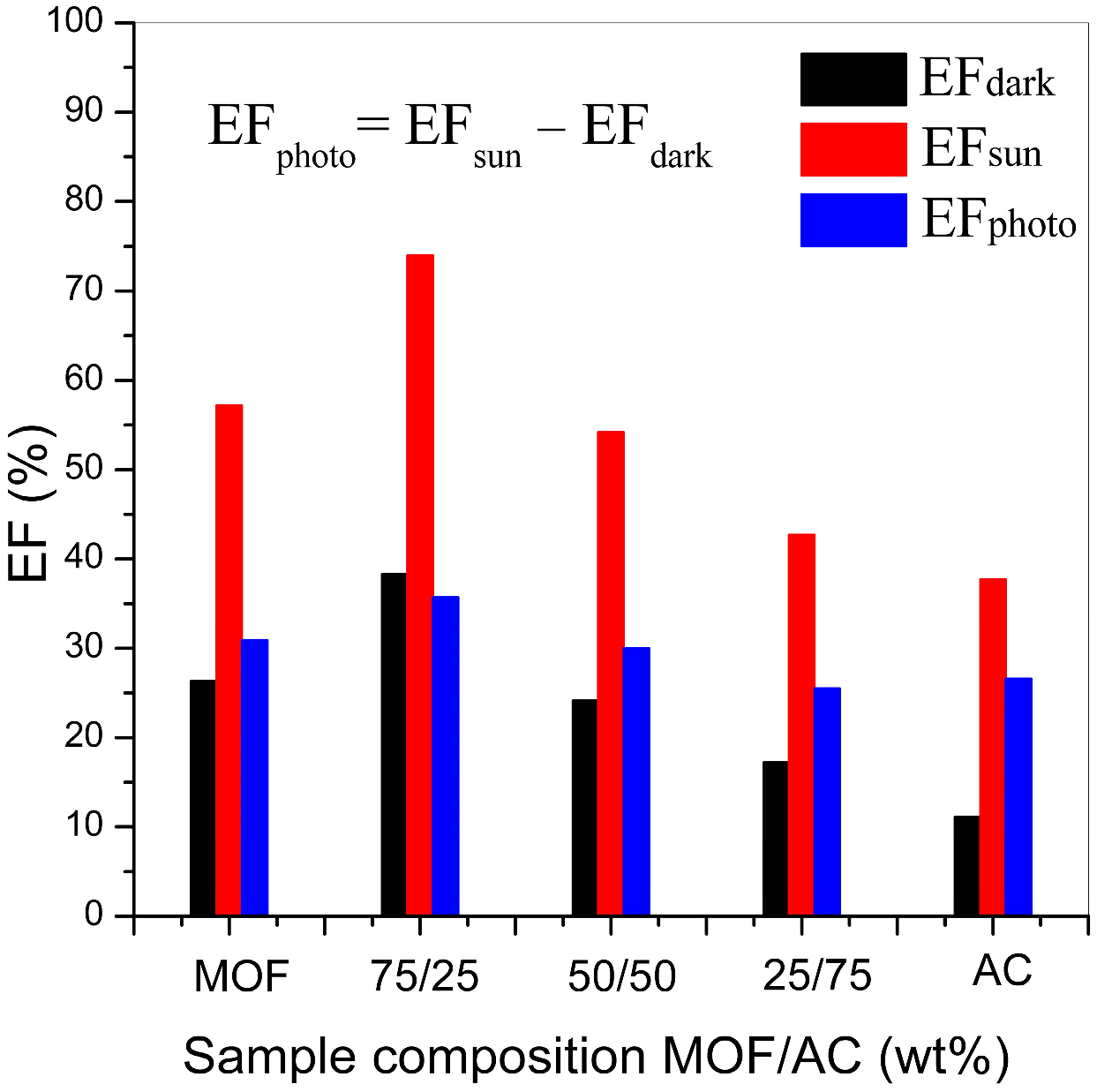

2.2. Photocatalytic Experiments Under Solar Irradiation

Photocatalytic reactions were carried out in transparent glass vessels under natural sunlight. All experiments were done in the shortest possible timeframe (10–20 June), under clear weather conditions with no clouds, at the same time (12:00–14:00 h), to minimise uneven solar irradiation. Illuminance ranged from 120,000 to 160,000 Lux, in a 12:00–14:00 period, with a maximum at 13:00 h in Belgrade, Serbia (44°45′30″ N, 20°35′58″ E). MOF, AC or MOF/AC composite catalysts were mixed with Congo red (CR) dye aqueous solution in 25 mL transparent glass vessels, without further agitation. The solid-to-solution ratio was 1:2000. Prior to solar irradiation, the samples were kept in the dark for several minutes due to transport. As a control, all experiments were also performed in the dark chamber, without any light source. Depending on the experimental design, catalysts were kept in contact with the CR solution for 1, 2 or 4 h.

Initial and final pH were measured with a Hanna HI 2211 pH meter. Final pH prior to UV/Vis measurements was adjusted to approximately pH = 6.8–7, unless otherwise indicated.

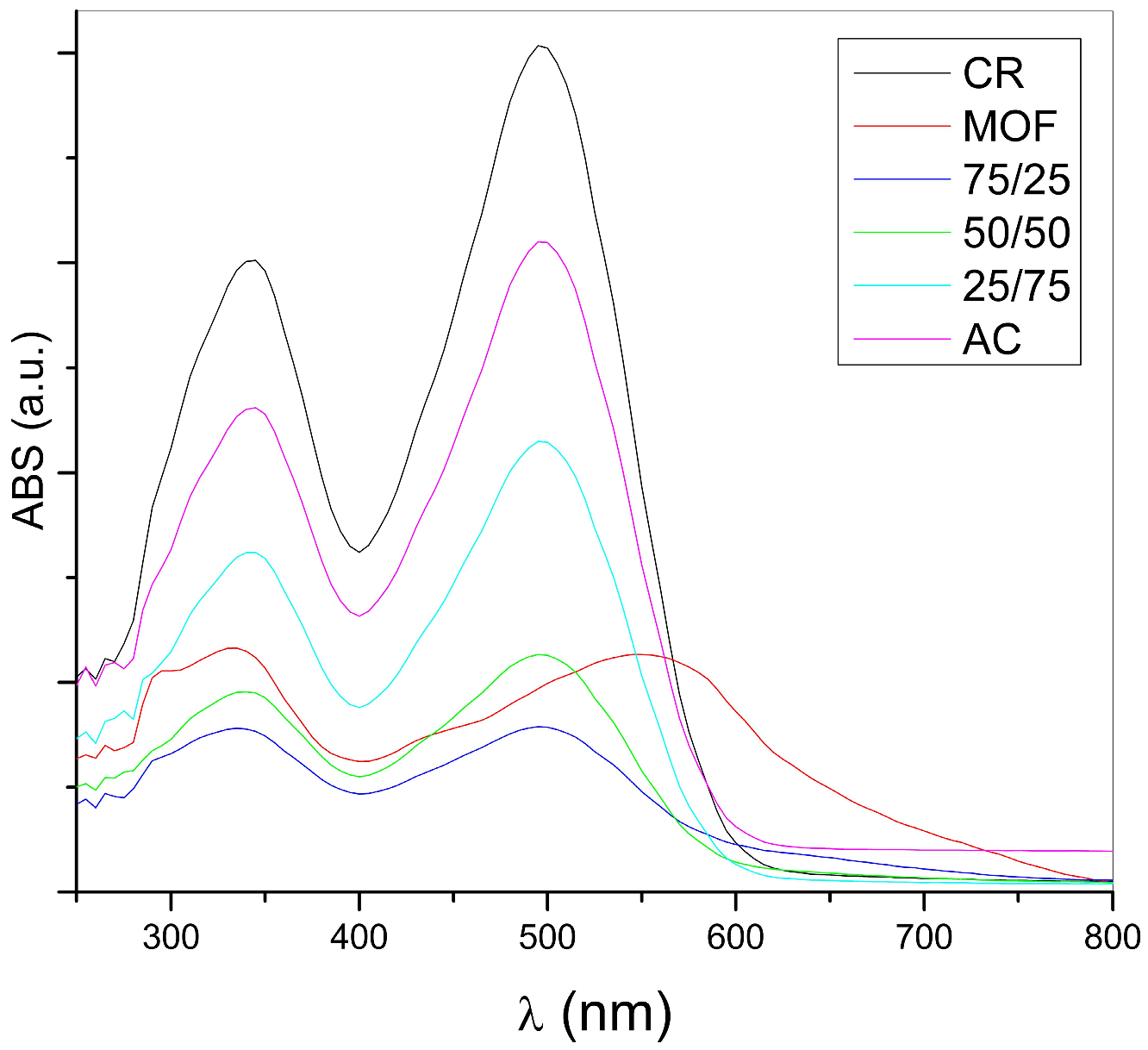

Distilled water was used to dissolve CR and prepare various concentrations of aqueous solutions. The concentration of CR was determined by analysing its absorbance values at a specific wavelength (498 nm) using a Thermo Scientific MULTISKAN GO UV/Vis spectrometer. To generate a calibration curve, absorbance measurements were taken from a series of standard solutions with concentrations ranging from 0 to 50 ppm.

After photocatalytic degradation experiments, the samples were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min to separate the catalysts, and the concentration of the remaining CR in the obtained clear solutions was then measured by UV/Vis. To assess the potential of MOF, AC and MOF/AC composites for CR degradation, the collected data were used for the calculation of removal efficiency RE (%), as given in Equation (1):

where

Ci is dye initial concentration (mg L

−1) and

Cf is dye residual concentration (mg L

−1).

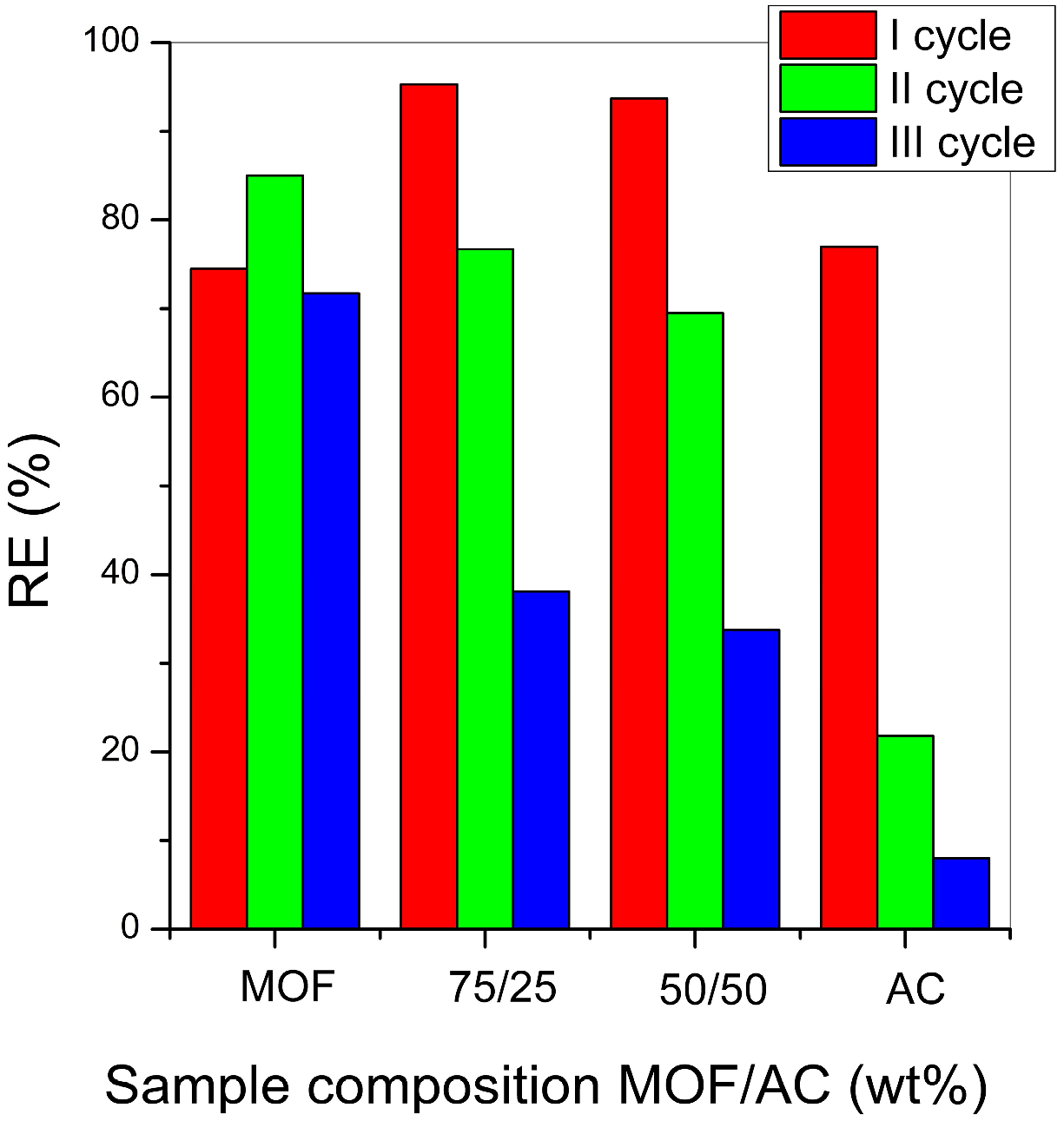

2.3. Reusability Experiments

The reusability of the catalysts was evaluated over multiple cycles using two methods. The first method (Method 1), commonly found in the literature, includes the following steps: at the end of each cycle, catalysts are separated from the solution, thoroughly washed with distilled water, dried at 100 °C, and then reused in a fresh CR solution. The second method (Method 2) was developed in this work to improve catalyst regeneration compared to Method 1. After separation from the CR solution, the samples were washed with distilled water, dried at 100 °C, and then left to stand in 10 mL of distilled water for about 15 days under solar irradiation. The indication that catalysts are regenerated was the moment when the sample of the pure MOF became white again, i.e., when all the CR that was adsorbed on the MOF surface probably decomposed. Catalysts regenerated in this way were then reused in a fresh CR solution.

2.4. Kinetic Experiments

Kinetic experiments were performed under controlled irradiation using a simulated solar light source (Osram Vitalux lamp, 300 W (OSRAM GmbH, Munich, Germany); UVB radiated power (280–315 nm): 3.0 W; UVA (315–400 nm): 13.6 W; remaining output in the visible and IR range). The measured illuminance was 35,000 Lux. Samples were continuously cooled so that the reaction solutions remained at 25 °C throughout the measurements. Before illumination, the catalyst (50/50 MOF/AC composite) was added in a 25 ppm CR solution and then kept in the dark for 30 min to reach adsorption–desorption equilibrium. The amount of dye adsorbed in this step was quantified spectrophotometrically and expressed as adsorbed mass per gram of catalyst (q, mg g

−1), calculated using

where

C0 is the initial dye concentration (mg L

−1),

Ct is the concentration after the dark adsorption period (mg L

−1),

V is the solution volume (L), and

m is the catalyst mass (g).

Immediately after the 30-min dark step, illumination was initiated, and aliquots were collected at defined time intervals (5, 30, 60, 120 and 240 min) for UV–Vis analysis. The post-adsorption concentration (

Ct) was used as

C0 in kinetic modelling. Pseudo-first-order (Equation (3)) and pseudo-second-order (Equation (4)) kinetic models were evaluated based on the corresponding linearised forms:

where

k1 and

k2 are the apparent rate constants for the respective models.

2.5. Characterization of MOF, AC and Synthesised Composites

The microstructure of the MOF, AC and composites was analysed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) method—Rigaku Ultima IV diffractometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan), with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1, 4178 Å). The diffractograms were collected in the 2θ range from 5° to 90° with a scanning step size of 0.02 and at a scan rate of 5° min−1.

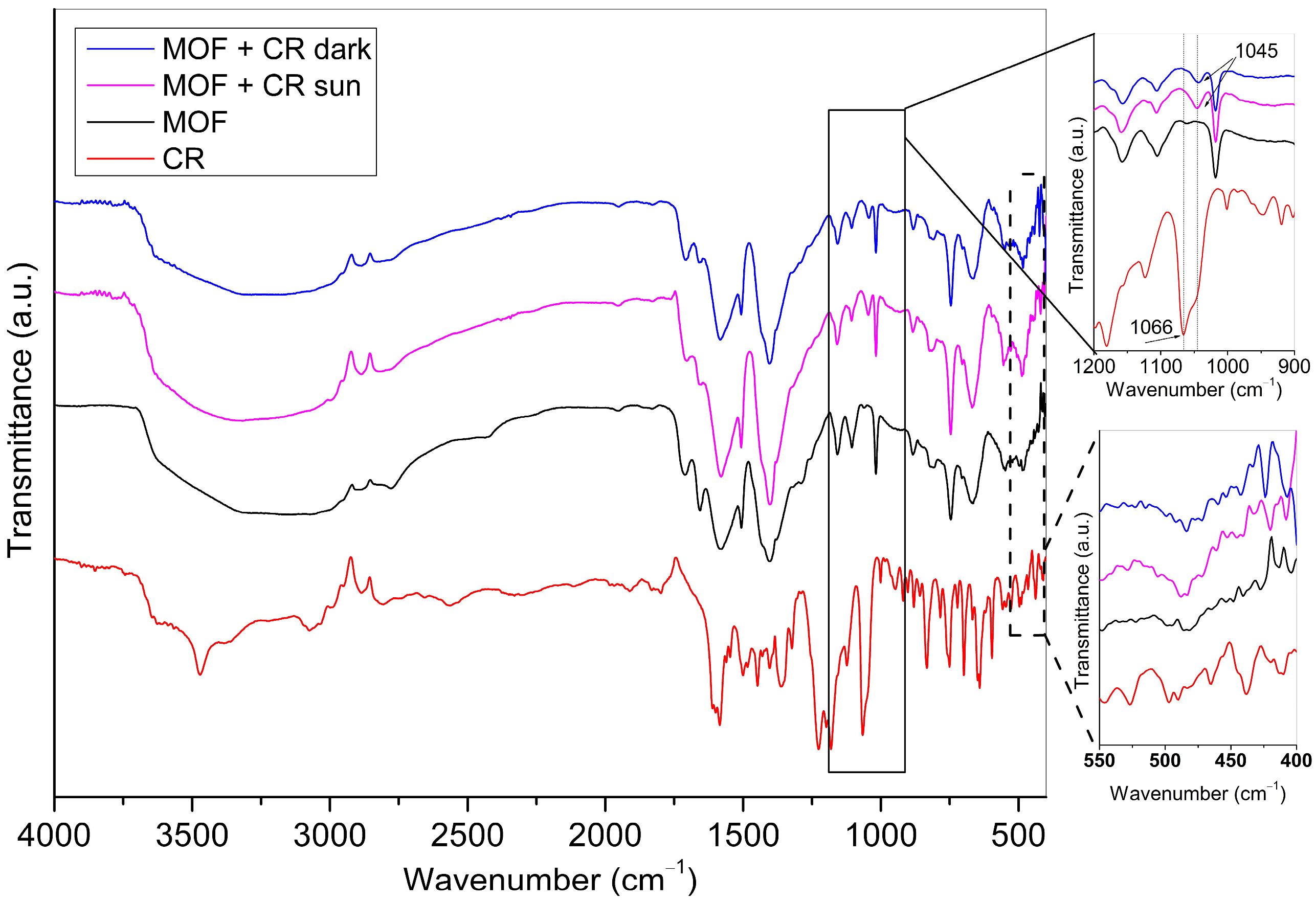

Infrared spectra were obtained by a Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer (FTIR)—Spectrum Two Spectrometer (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) in the range 4000–450 cm−1, with a resolution of 4 cm−1. The diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform (DRIFT) method was used for the spectra recording.

Raman spectra were obtained using a Labram Soleil Raman instrument (Horiba scientific, Kyoto, Japan), with the laser excitation wavelength of 532 nm.