Assessing Climate Change and Reservoir Impacts on Upper Miño River Flow (NW Iberian Peninsula) Using Neural Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Area of Study, Materials and Methods

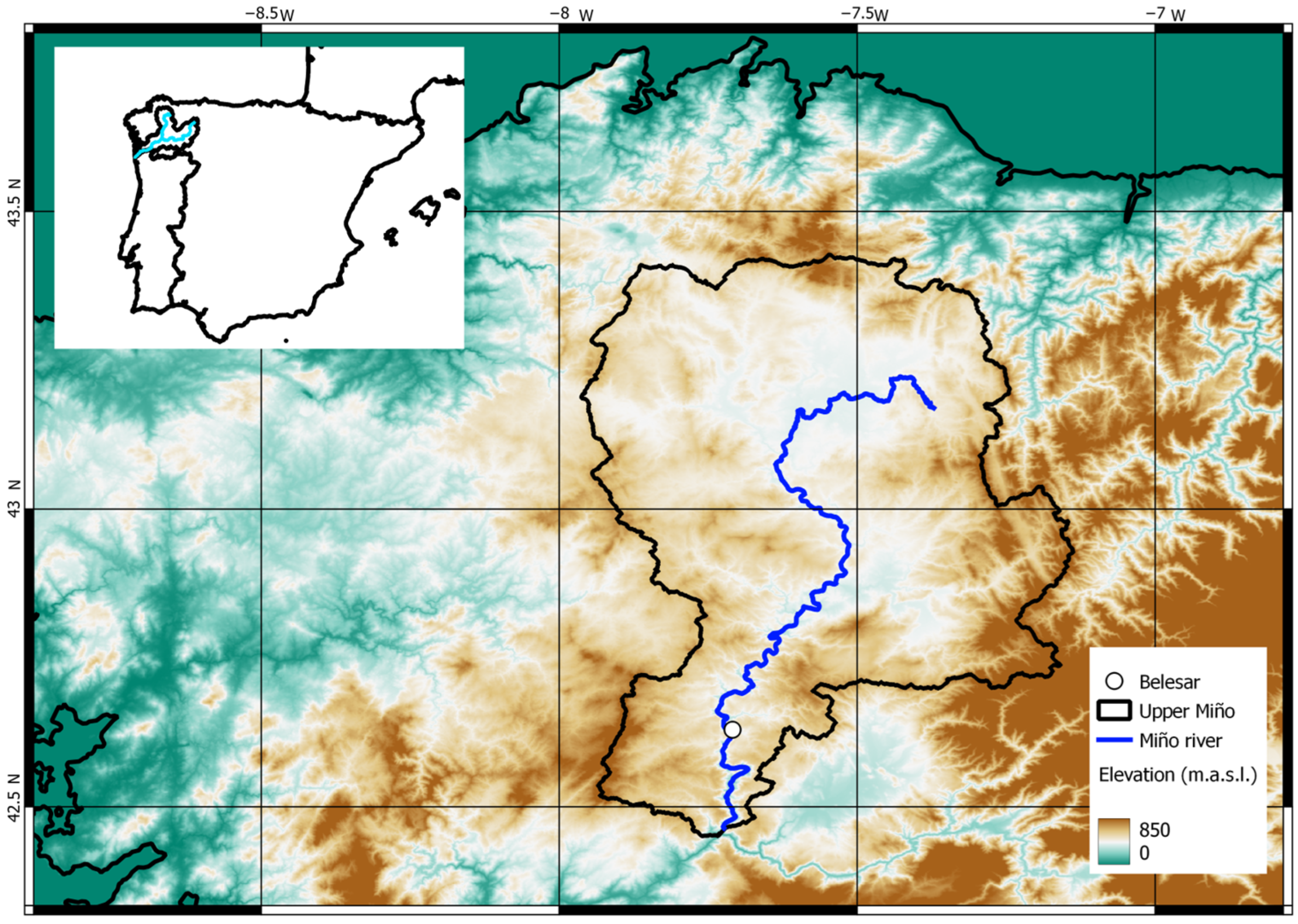

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Reservoir Data

2.2.2. Historical Precipitation and Temperature Data

2.2.3. Climate Model Precipitation and Temperature Data

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Neural Network Modeling of the Hydrological Cycle

2.3.2. Neural Network Reservoir Operation Modeling

2.4. Validation of Neural Network Procedure

2.4.1. Validation of River Flow Modeling

2.4.2. Validation of Reservoir Operation Modeling

3. Results and Discussion

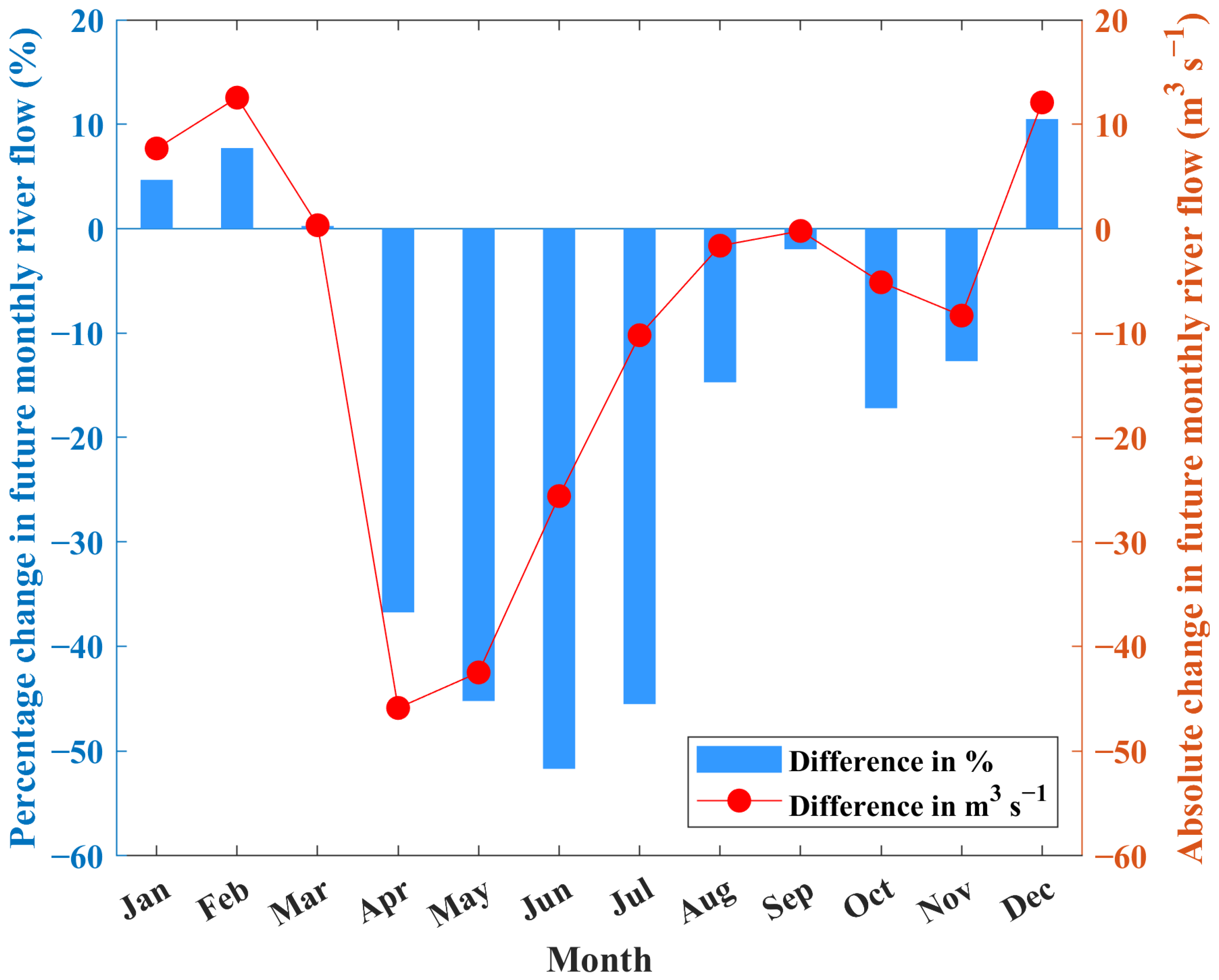

3.1. Analysis of Changes Between Historical and Future River Flows: SSP5-8.5 Scenario

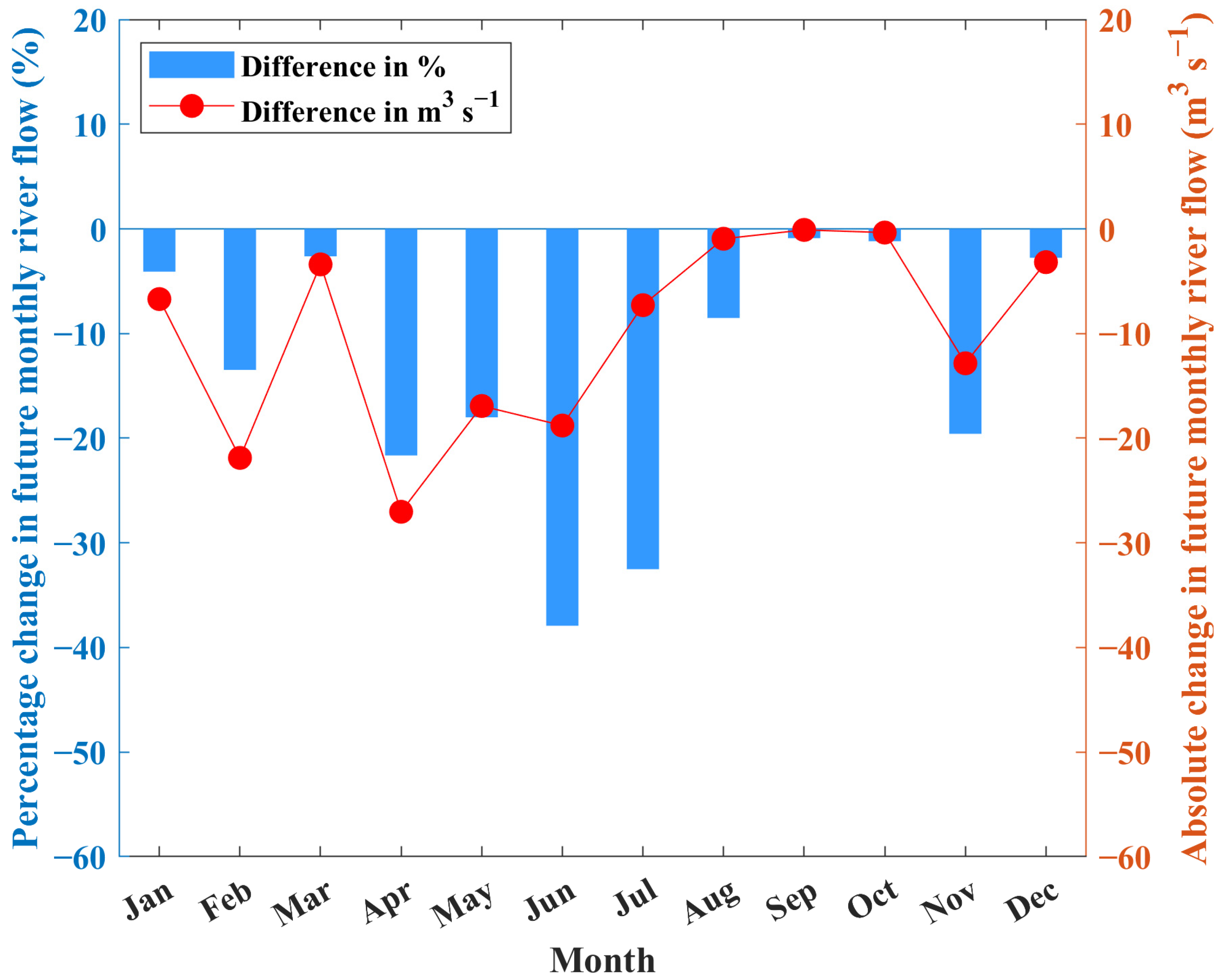

3.2. Analysis of Changes Between Historical and Future River Flows: SSP5-4.5 Scenario

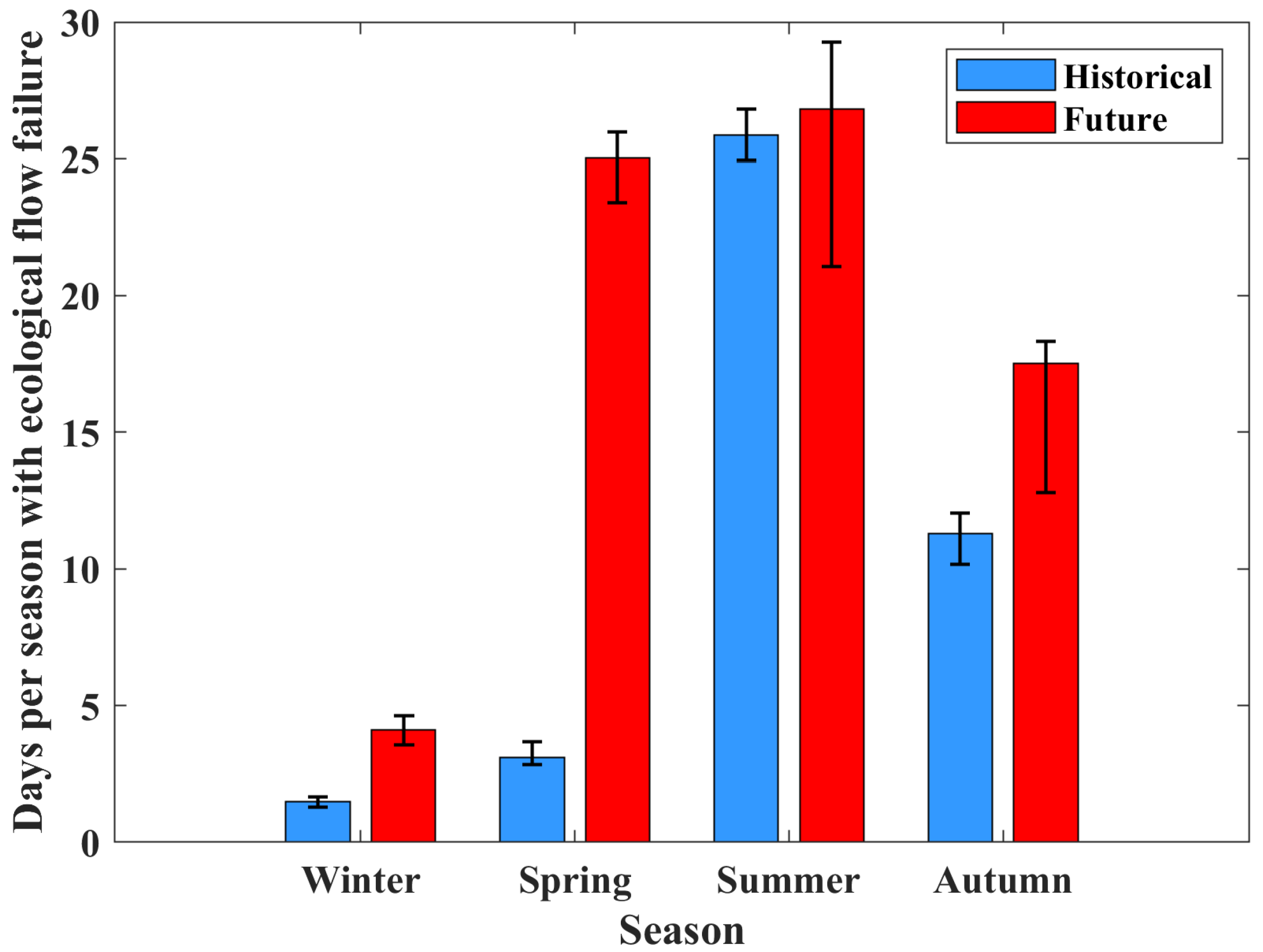

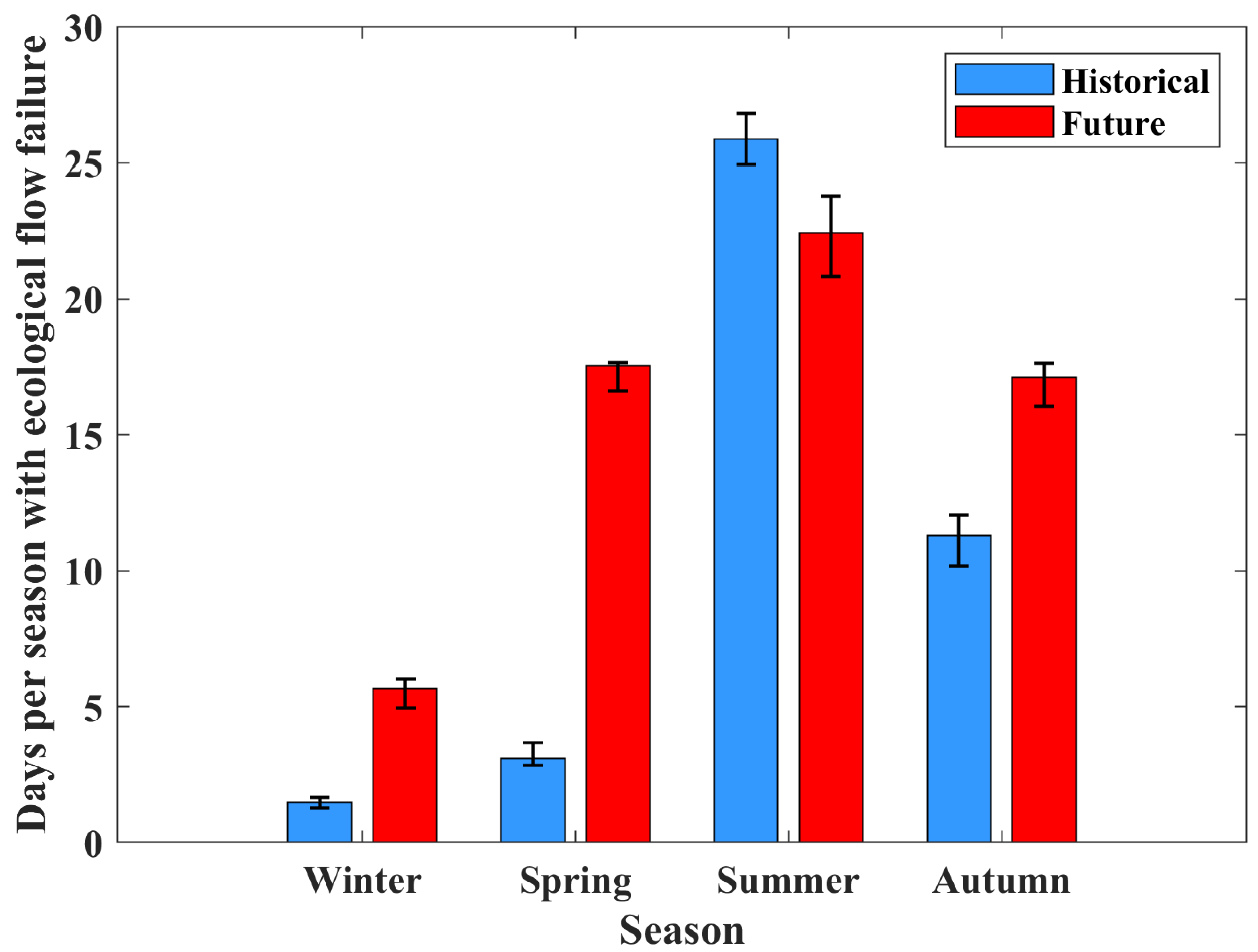

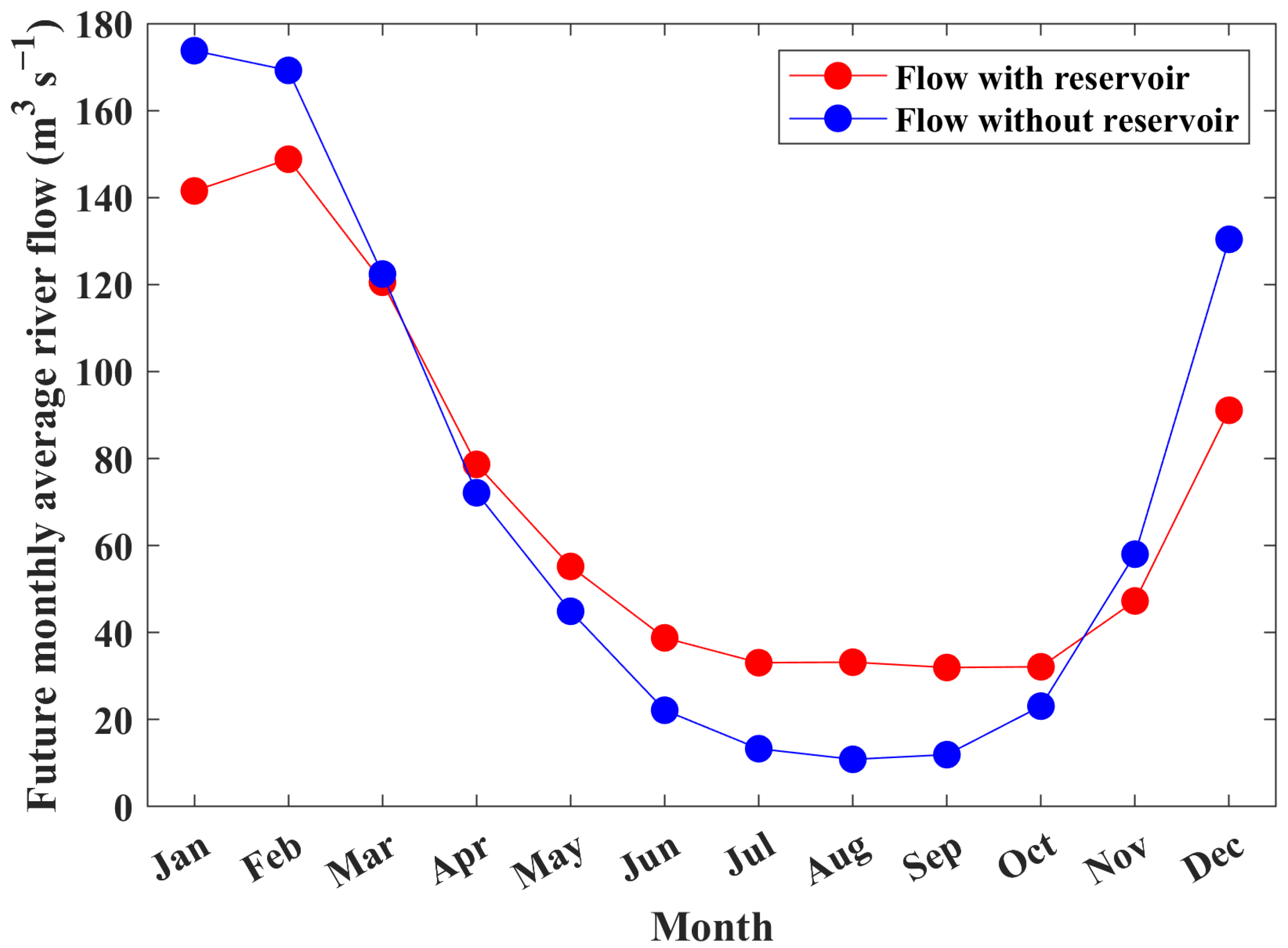

3.3. Analysis of Impact of Belesar Reservoir in Future River Flows Obtained for the SSP5-8.5 Scenario

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L.; Gomis, M.I. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; Volume 2, p. 2391. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, R.P.; Barlow, M.; Byrne, M.P.; Cherchi, A.; Douville, H.; Fowler, H.J.; Gan, T.Y.; Pendergrass, A.G.; Rosenfeld, D.; Swann, A.L.S.; et al. Advances in Understanding Large-scale Responses of the Water Cycle to Climate Change. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2020, 1472, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, F.H.; Allan, R.P.; Behrangi, A.; Byrne, M.P.; Ceppi, P.; Chadwick, R.; Durack, P.J.; Fosser, G.; Fowler, H.J.; Greve, P.; et al. Changes in the Regional Water Cycle and Their Impact on Societies. WIREs Clim. Change 2025, 16, e70005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwuma Sr, C. Invariance of Extreme Hydrologic Events and Climate Change in the Risk Reduction on Environment and Health. Grn Int. J. Apl. Med. Sci. 2025, 3, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, O.V.; McGuire, P.C.; Vidale, P.L.; Hawkins, E. River Flow in the near Future: A Global Perspective in the Context of a High-Emission Climate Change Scenario. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 2179–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páscoa, P.; Russo, A.; Gouveia, C.M.; Soares, P.M.; Cardoso, R.M.; Careto, J.A.; Ribeiro, A.F. A High-Resolution View of the Recent Drought Trends over the Iberian Peninsula. Weather. Clim. Extrem. 2021, 32, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramblay, Y.; Koutroulis, A.; Samaniego, L.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Volaire, F.; Boone, A.; Le Page, M.; Llasat, M.C.; Albergel, C.; Burak, S. Challenges for Drought Assessment in the Mediterranean Region under Future Climate Scenarios. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 210, 103348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöschl, G.; Hall, J.; Viglione, A.; Perdigão, R.A.; Parajka, J.; Merz, B.; Lun, D.; Arheimer, B.; Aronica, G.T.; Bilibashi, A. Changing Climate Both Increases and Decreases European River Floods. Nature 2019, 573, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnell, N.W.; Gosling, S.N. The Impacts of Climate Change on River Flood Risk at the Global Scale. Clim. Change 2016, 134, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Miao, C.; Zhang, X.; Yang, T.; Duan, Q. Detecting the Quantitative Hydrological Response to Changes in Climate and Human Activities. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Deng, H.; Jian, J. Hydrological Processes under Climate Change and Human Activities: Status and Challenges. Water 2023, 15, 4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwira, S.; Damazio, C. Quantification of the Effects of Climatic Factors and Anthropogenic Activities on Streamflow: A Systematic Review. Discov. Water 2025, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Yang, Y. Climate Change and Hydrological Extremes. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2024, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Nóvoa, D.; Soares, P.M.; García-Feal, O.; Costoya, X.; Trigo, R.M.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. Neural Network Approach for Modeling Future Natural River Flows: Assessing Climate Change Impacts on the Tagus River. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 58, 102191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Nóvoa, D.; García-Feal, O.; González-Cao, J.; DeCastro, M.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. Multiscale Flood Risk Assessment under Climate Change: The Case of the Miño River in the City of Ourense, Spain. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 22, 3957–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, R.M.; DaCamara, C.C. Circulation Weather Types and Their Influence on the Precipitation Regime in Portugal. Int. J. Climatol. 2000, 20, 1559–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Moreno, J.I.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Zabalza, J.; Beguería, S.; Lorenzo-Lacruz, J.; Azorín-Molina, C.; Morán-Tejeda, E. Hydrological Response to Climate Variability at Different Time Scales: A Study in the Ebro Basin. J. Hydrol. 2013, 477, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, R.M.; Ramos, C.; Pereira, S.S.; Ramos, A.M.; Zêzere, J.L.; Liberato, M.L. The Deadliest Storm of the 20th Century Striking Portugal: Flood Impacts and Atmospheric Circulation. J. Hydrol. 2016, 541, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, M.N.; Alvarez, I. Climate Change Patterns in Precipitation over Spain Using CORDEX Projections for 2021–2050. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 723, 138024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEDEX. Evaluación Del Impacto Del Cambio Climático En Los Recursos Hídricos y Sequías En España; Centro de Estudios y Experimentaci’on de Obras Públicas: Madrid, Spain, 2017. Available online: https://ceh.cedex.es/web/documentos/CAMREC/2017_07_424150001_Evaluaci%C3%B3n_cambio_clim%C3%A1tico_recu.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Soares, P.M.M.; Lima, D.C.A. Water Scarcity down to Earth Surface in a Mediterranean Climate: The Extreme Future of Soil Moisture in Portugal. J. Hydrol. 2022, 615, 128731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.M.; Trigo, R.M.; Liberato, M.L.R.; Tomé, R. Daily Precipitation Extreme Events in the Iberian Peninsula and Its Association with Atmospheric Rivers. J. Hydrometeorol. 2015, 16, 579–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.M.; Roca, R.; Soares, P.M.M.; Wilson, A.M.; Trigo, R.M.; Ralph, F.M. Uncertainty in Different Precipitation Products in the Case of Two Atmospheric River Events. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 045012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cao, J.; García-Feal, O.; Fernández-Nóvoa, D.; Domínguez-Alonso, J.M.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. Towards an Automatic Early Warning System of Flood Hazards Based on Precipitation Forecast: The Case of the Miño River (NW Spain). Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 19, 2583–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Nóvoa, D.; García-Feal, O.; González-Cao, J.; de Gonzalo, C.; Rodríguez-Suárez, J.A.; Ruiz del Portal, C.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. MIDAS: A New Integrated Flood Early Warning System for the Miño River. Water 2020, 12, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PLAN HIDROLÓGICO 2022-2027 (EN VIGOR RD 35/2023)—Confederacion Hidrográfica del Miño-Sil. Available online: https://www.chminosil.es/es/chms/planificacionhidrologica/propuesta-de-proyecto-de-plan-hidrologico2022-2027-version-cna (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Descripción—Confederacion Hidrográfica del Miño-Sil. Available online: https://www.chminosil.es/es/chms/demarcacion/marco-fisico/descripcion (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Le, X.-H.; Ho, H.V.; Lee, G.; Jung, S. Application of Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Neural Network for Flood Forecasting. Water 2019, 11, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Feal, O.; González-Cao, J.; Fernández-Nóvoa, D.; Astray Dopazo, G.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. Comparison of Machine Learning Techniques for Reservoir Outflow Forecasting. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 2022, 3859–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, Y.; Lyu, L.; Cai, X. Uncovering Historical Reservoir Operation Rules and Patterns: Insights From 452 Large Reservoirs in the Contiguous United States. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR036686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, S.; Cardoso, R.M.; Soares, P.M.; Espírito-Santo, F.; Viterbo, P.; Gutiérrez, J.M. Iberia01: A New Gridded Dataset of Daily Precipitation and Temperatures over Iberia. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1947–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skamarock, W.C.; Klemp, J.B.; Dudhia, J.; Gill, D.O.; Liu, Z.; Berner, J.; Wang, W.; Powers, J.G.; Duda, M.G.; Barker, D.M. A Description of the Advanced Research WRF Version 4; National Center for Atmospheric Research: Boulder, CO, USA, 2019; Volume 145. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, B.; Costoya, X.; Decastro, M.; Insua-Costa, D.; Senande-Rivera, M.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. Downscaling CMIP6 Climate Projections to Classify the Future Offshore Wind Energy Resource in the Spanish Territorial Waters. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 433, 139860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwalm, C.R.; Glendon, S.; Duffy, P.B. RCP8.5 Tracks Cumulative CO2 Emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 19656–19657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewamalage, H.; Bergmeir, C.; Bandara, K. Recurrent Neural Networks for Time Series Forecasting: Current Status and Future Directions. Int. J. Forecast. 2021, 37, 388–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.R.; Ramos, T.B.; Neves, R. Streamflow Estimation in a Mediterranean Watershed Using Neural Network Models: A Detailed Description of the Implementation and Optimization. Water 2023, 15, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.R.; Ramos, T.B.; Simionesei, L.; Neves, R. Assessing the Reliability of a Physical-Based Model and a Convolutional Neural Network in an Ungauged Watershed for Daily Streamflow Calculation: A Case Study in Southern Portugal. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; Jimeno-Saez, P.; Lopez-Ballesteros, A.; Senent-Aparicio, J. Coupling SWAT+ with LSTM for Enhanced and Interpretable Streamflow Estimation in Arid and Semi-Arid Watersheds, a Case Study of the Tagus Headwaters River Basin, Spain. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 186, 106360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R. ANN-Based Rainfall-Runoff Model and Its Performance Evaluation of Sabarmati River Basin, Gujarat, India. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2022, 7, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedam, N.; Tiwari, D.K.; Kumar, V.; Khedher, K.M.; Salem, M.A. River Stream Flow Prediction through Advanced Machine Learning Models for Enhanced Accuracy. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meresa, H. Modelling of River Flow in Ungauged Catchment Using Remote Sensing Data: Application of the Empirical (SCS-CN), Artificial Neural Network (ANN) and Hydrological Model (HEC-HMS). Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2019, 5, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Guan, Q.; Du, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, E. Exploring Future Trends of Precipitation and Runoff in Arid Regions under Different Scenarios Based on a Bias-Corrected CMIP6 Model. J. Hydrol. 2024, 630, 130666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, R.E. The Use of Soil Moisture Budgeting to Improve Stormflow Estimates by the SCS Curve Number Method. Univ. Natal. Dep. Agric. Eng. Pietermaritzbg. S. Afr. 1982, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Cea, L.; Fraga, I. Incorporating Antecedent Moisture Conditions and Intraevent Variability of Rainfall on Flood Frequency Analysis in Poorly Gauged Basins. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 8774–8791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriasi, D.N.; Arnold, J.G.; Van Liew, M.W.; Bingner, R.L.; Harmel, R.D.; Veith, T.L. Model Evaluation Guidelines for Systematic Quantification of Accuracy in Watershed Simulations. Trans. ASABE 2007, 50, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.-F.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Zhao, X.; Xie, E.; Qiu, J. Decomposition-ANN Methods for Long-Term Discharge Prediction Based on Fisher’s Ordered Clustering with MESA. Water Resour. Manag. 2019, 33, 3095–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, M.G.-V.; Gámiz-Fortis, S.R.; Romero-Jiménez, E.; Rosa-Cánovas, J.J.; Yeste, P.; Castro-Díez, Y.; Esteban-Parra, M.J. Projected Changes in the Iberian Peninsula Drought Characteristics. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, L.; Burek, P.; Feyen, L.; Forzieri, G. Global Warming Increases the Frequency of River Floods in Europe. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 19, 2247–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficklin, D.L.; Null, S.E.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Novick, K.A.; Myers, D.T. Hydrological Intensification Will Increase the Complexity of Water Resource Management. Earths Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sante, F.; Coppola, E.; Giorgi, F. Projections of River Floods in Europe Using EURO-CORDEX, CMIP5 and CMIP6 Simulations. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, 3203–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, X.; Leung, L.R.; Liu, C.; Zheng, C.; Guo, Y.; Chiew, F.H.; Post, D.; Kong, D. Future Global Streamflow Declines Are Probably More Severe than Previously Estimated. Nat. Water 2023, 1, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Beltran, B.; Sordo-Ward, A.; Martin-Carrasco, F.; Garrote, L. High-Resolution Estimates of Water Availability for the Iberian Peninsula under Climate Scenarios. Appl. Water Sci. 2024, 14, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, D.B.; Iribas, B.L.; Calvo, P.C. Proposal for Analysis of Minimum Ecological Flow Regimes Based on the Achievement of Technical and Environmental Objectives: Tagus River Basin Case Study (Spain). Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Zabalza-Martínez, J.; Borràs, G.; López-Moreno, J.I.; Pla, E.; Pascual, D.; Savé, R.; Biel, C.; Funes, I.; Martín-Hernández, N. Effect of Reservoirs on Streamflow and River Regimes in a Heavily Regulated River Basin of Northeast Spain. Catena 2017, 149, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán-Tejeda, E.; Lorenzo-Lacruz, J.; López-Moreno, J.I.; Ceballos-Barbancho, A.; Zabalza, J.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M. Reservoir Management in the Duero Basin (Spain): Impact on River Regimes and the Response to Environmental Change. Water Resour. Manag. 2012, 26, 2125–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Neurons | NSE | PBIAS |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.858 ± 0.011 | 11.2 ± 3.1 |

| 2 | 0.844 ± 0.035 | 12.3 ± 5.8 |

| 3 | 0.885 ± 0.039 | 3.7 ± 3.9 |

| 4 | 0.864 ± 0.042 | 6.1 ± 9.5 |

| 5 | 0.889 ± 0.041 | 4.9 ± 4.1 |

| 6 | 0.920 ± 0.054 | 4.1 ± 6.4 |

| 7 | 0.929 ± 0.039 | 1.8 ± 2.3 |

| 8 | 0.942 ± 0.033 | 0.4 ± 1.6 |

| 9 | 0.929 ± 0.044 | 2.3 ± 5.0 |

| 10 | 0.939 ± 0.034 | 0.5 ± 1.7 |

| Period | 10th Percentile (m3 s−1) | Std (m3 s−1) | 99.997th Percentile (m3 s−1) | Std (m3 s−1) | Mean Flow (m3 s−1) | Std (m3 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical | 7.8 | 0.8 | 1574.1 | 256.3 | 84.3 | 2.7 |

| Future (SSP5-8.5) | 6.9 | 2.2 | 1655.2 | 304.4 | 70.7 | 4.6 |

| Future (SSP2-4.5) | 7.4 | 1.1 | 1069.7 | 108.7 | 71.8 | 2.8 |

| Month | Natural Conditions (m3 s−1) | Reservoir Operation (m3 s−1) | Percentage Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 173.7 ± 8.7 | 141.5 ± 9.6 | −19 |

| February | 169.2 ± 12.9 | 148.8 ± 13.4 | −12 |

| March | 122.4 ± 10.2 | 120.5 ± 10.7 | −2 |

| April | 72.1 ± 7.6 | 78.7 ± 7.3 | +9 |

| May | 44.9 ± 4.7 | 55.2 ± 4.1 | +22 |

| June | 22.1 ± 2.1 | 38.8 ± 1.1 | +75 |

| July | 13.3 ± 2.8 | 33.1 ± 1.3 | +148 |

| August | 10.8 ± 4.1 | 33.2 ± 1.6 | +205 |

| September | 11.9 ± 5.3 | 31.9 ± 2.5 | +167 |

| October | 23.1 ± 6.2 | 32.2 ± 4.1 | +39 |

| November | 58.0 ± 5.6 | 47.3 ± 4.8 | −18 |

| December | 130.4 ± 7.3 | 91.1 ± 8.1 | −30 |

| Future River Flow | 10th Percentile (m3 s−1) | Std (m3 s−1) | 99.997th Percentile (m3 s−1) | Std (m3 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural conditions | 6.9 | 2.2 | 1655.2 | 304.4 |

| Reservoir operation | 10.7 | 2.0 | 1413.7 | 370.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barreiro-Fonta, H.; Fernández-Nóvoa, D. Assessing Climate Change and Reservoir Impacts on Upper Miño River Flow (NW Iberian Peninsula) Using Neural Networks. Water 2025, 17, 3514. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243514

Barreiro-Fonta H, Fernández-Nóvoa D. Assessing Climate Change and Reservoir Impacts on Upper Miño River Flow (NW Iberian Peninsula) Using Neural Networks. Water. 2025; 17(24):3514. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243514

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarreiro-Fonta, Helena, and Diego Fernández-Nóvoa. 2025. "Assessing Climate Change and Reservoir Impacts on Upper Miño River Flow (NW Iberian Peninsula) Using Neural Networks" Water 17, no. 24: 3514. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243514

APA StyleBarreiro-Fonta, H., & Fernández-Nóvoa, D. (2025). Assessing Climate Change and Reservoir Impacts on Upper Miño River Flow (NW Iberian Peninsula) Using Neural Networks. Water, 17(24), 3514. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243514