Phytoplankton Size as an Ecological Bioindicator in a Subtropical Fragmented River, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

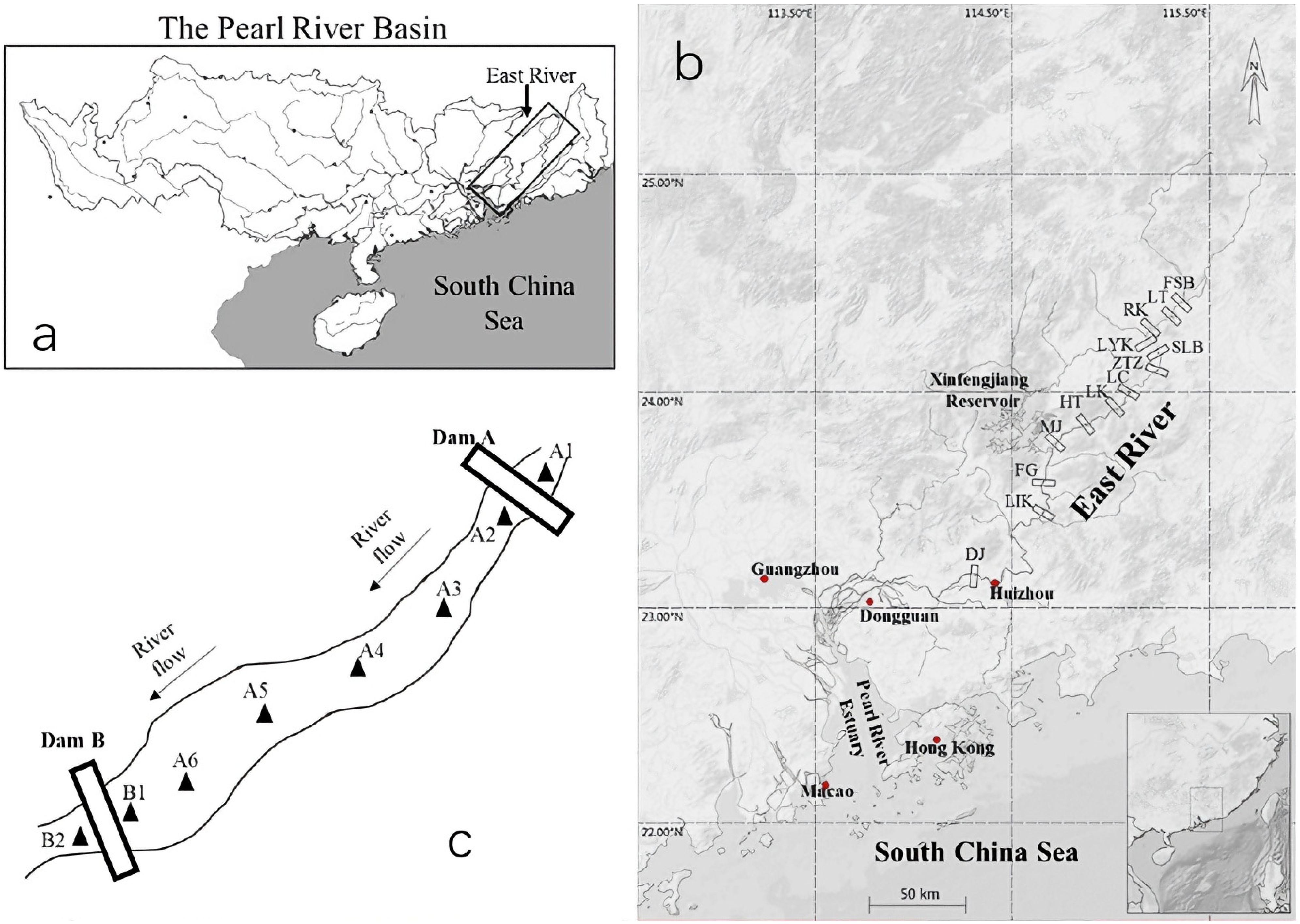

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Sampling and Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

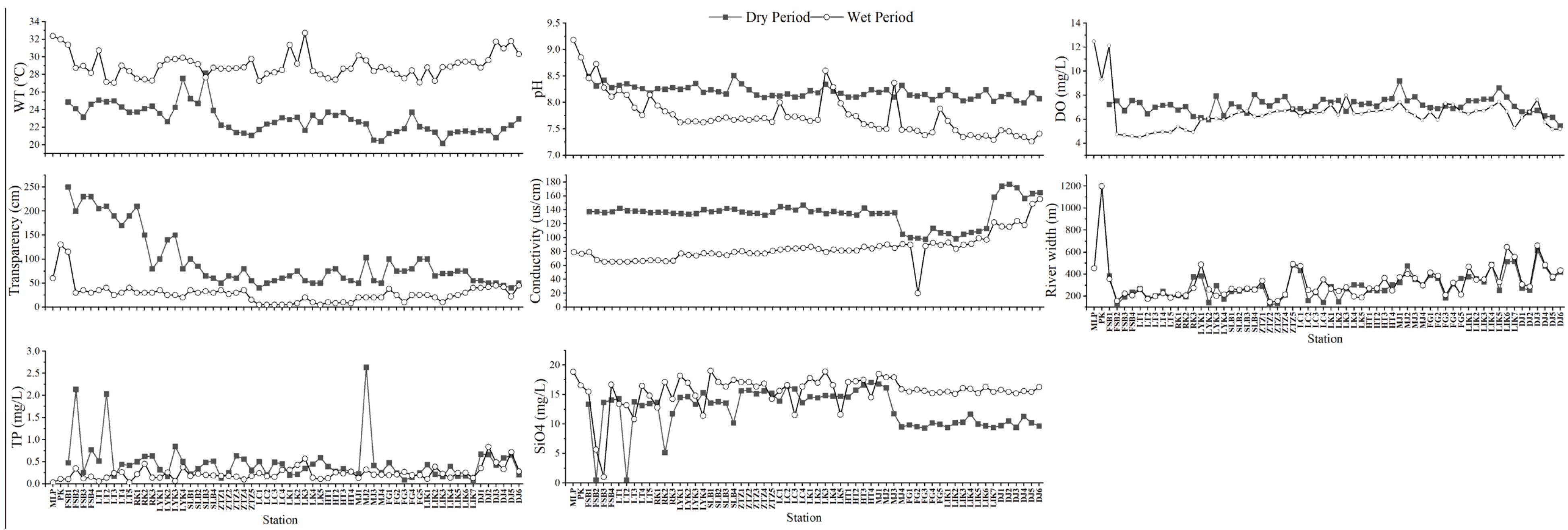

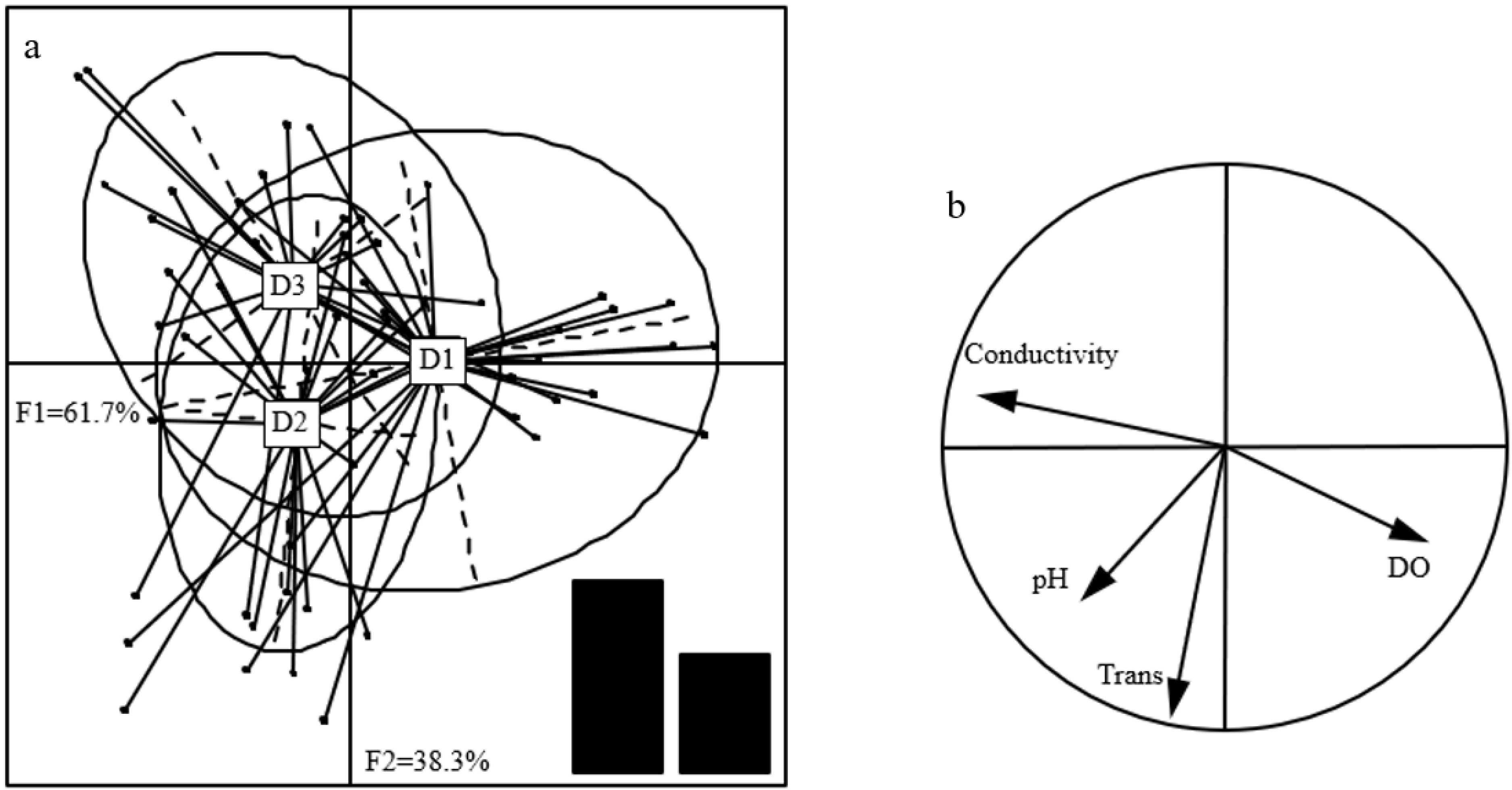

3.1. Water Environment Characteristics

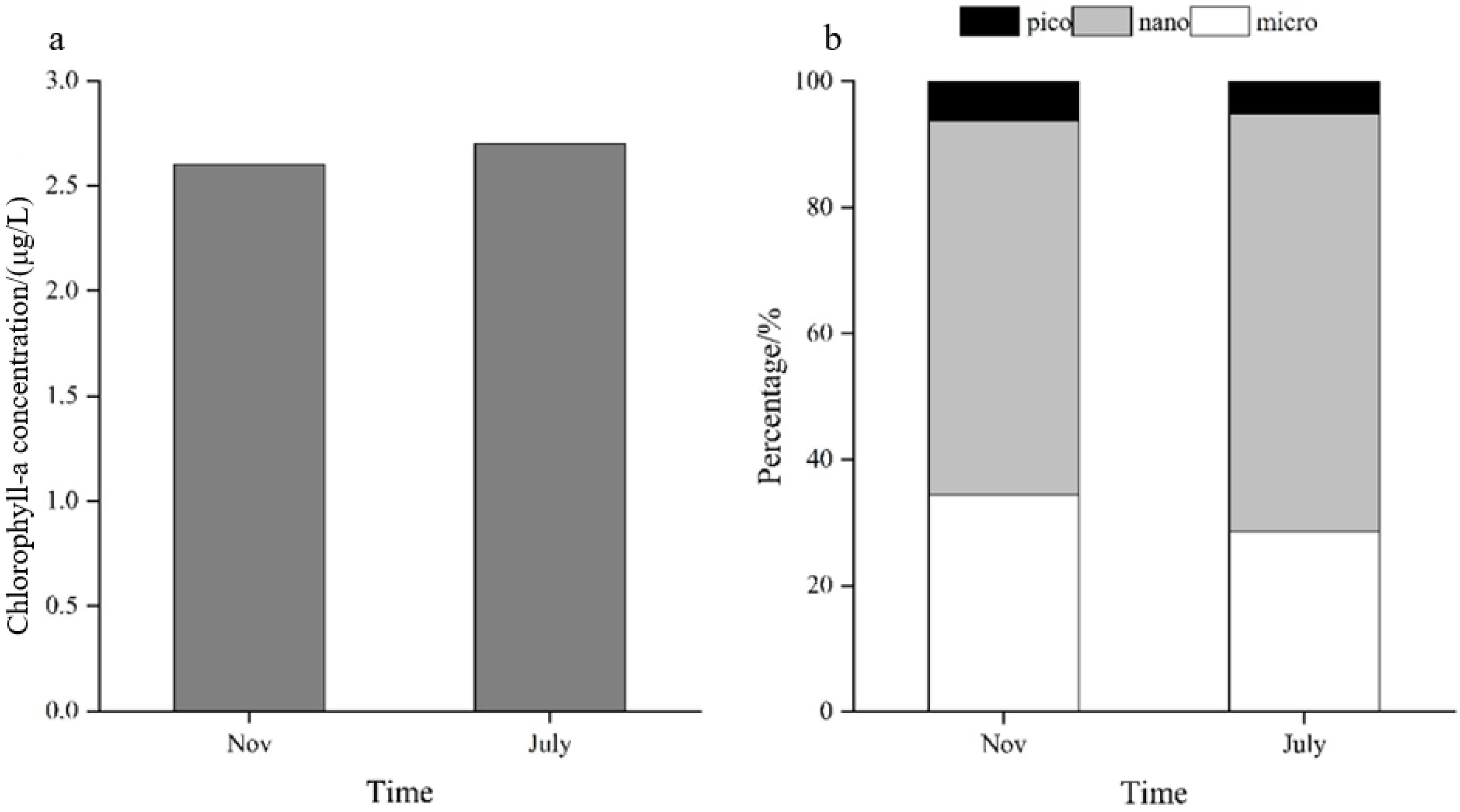

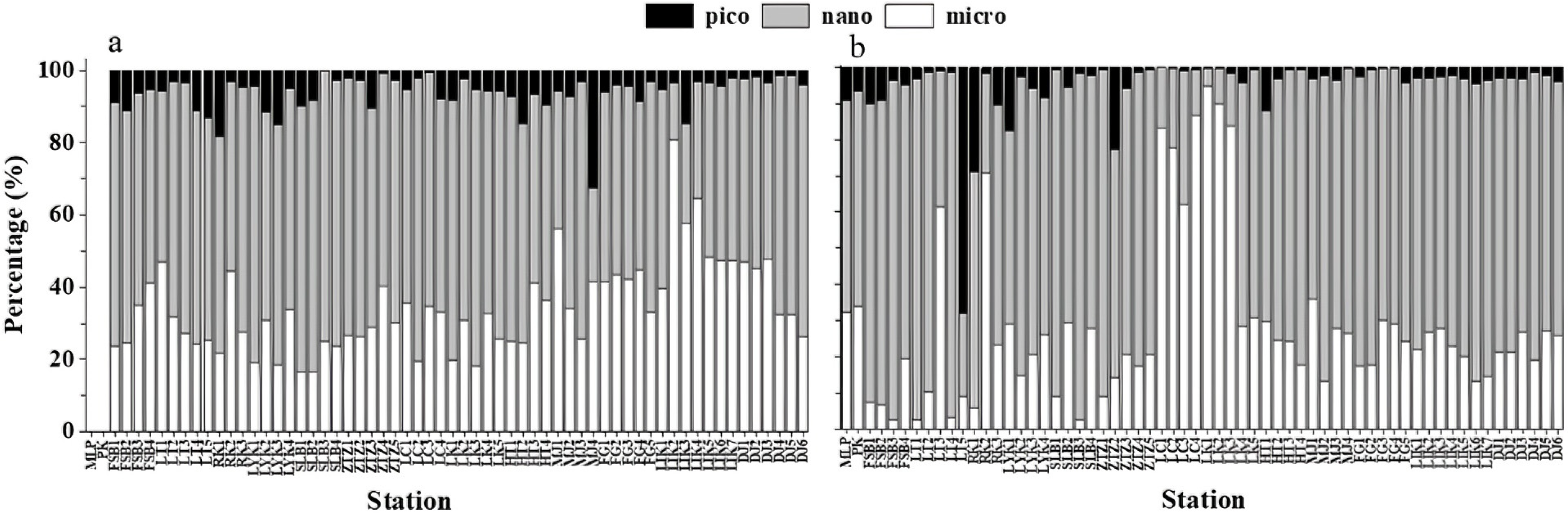

3.2. Seasonal Characteristics of the Total Chl-a Concentration and Particle Size Composition

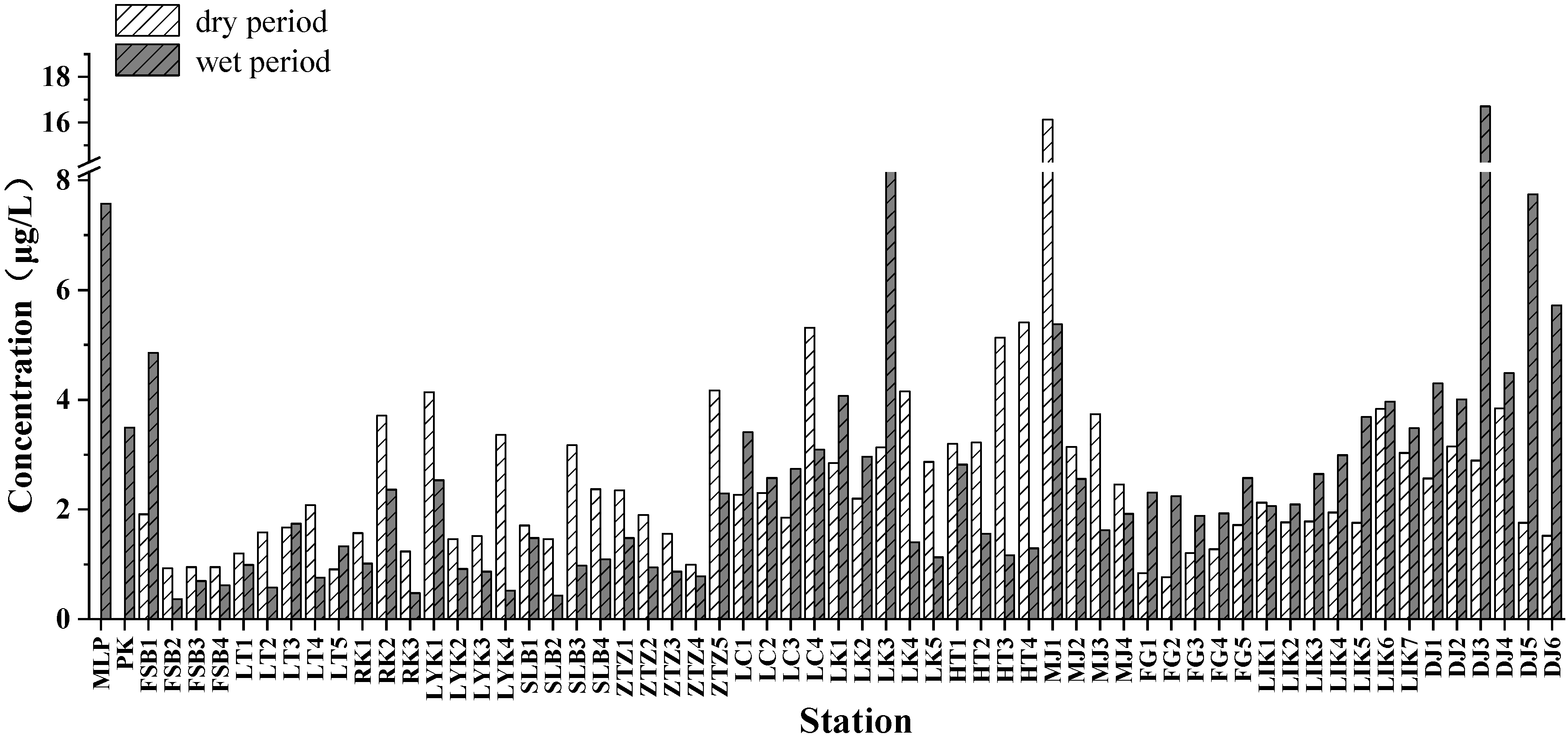

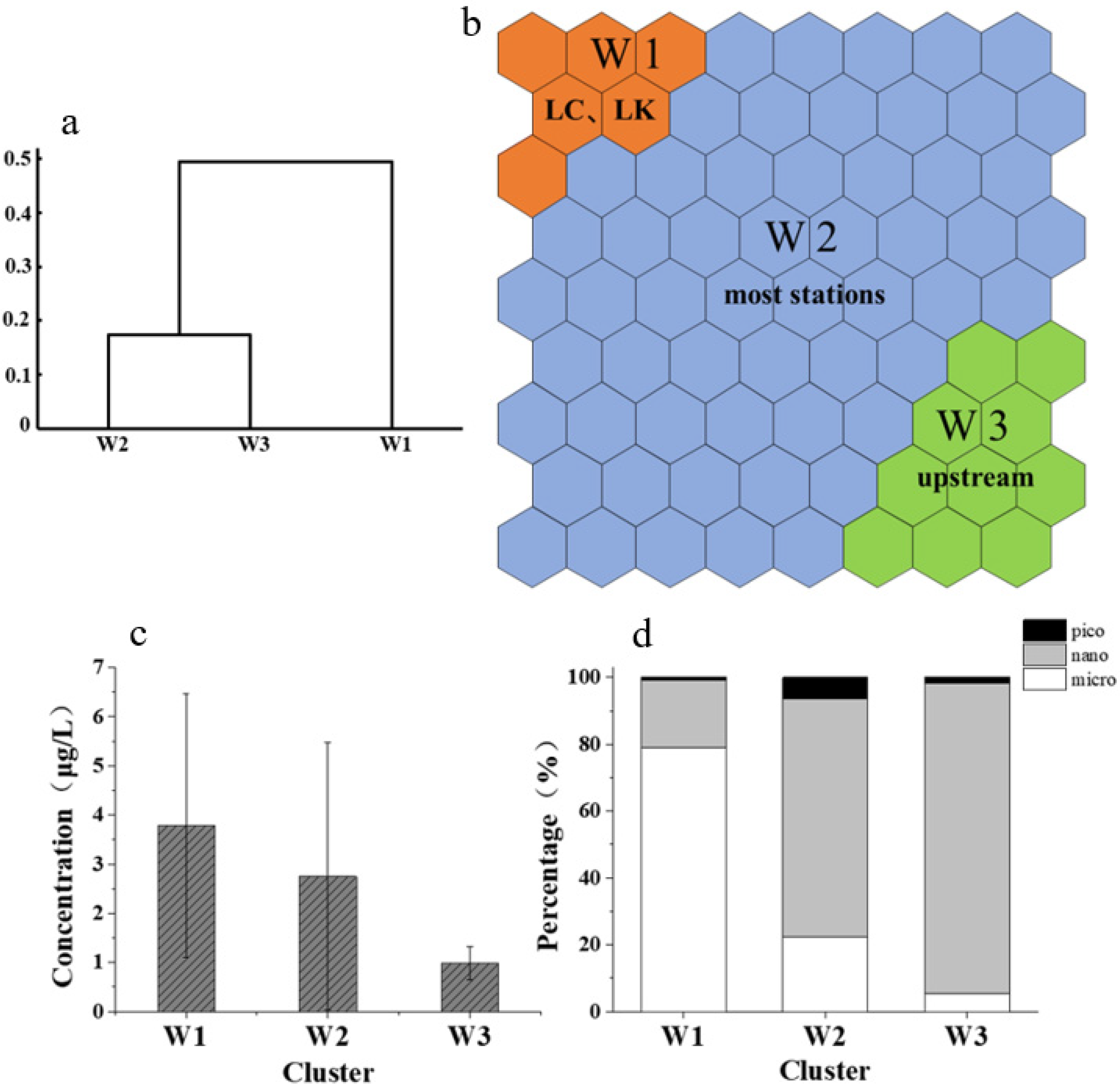

3.3. Spatial Characteristics of the Total Chl-a Concentration

3.4. Spatial Characteristics of the Percentage Composition of Chl-a Concentration in Different Particle Sizes

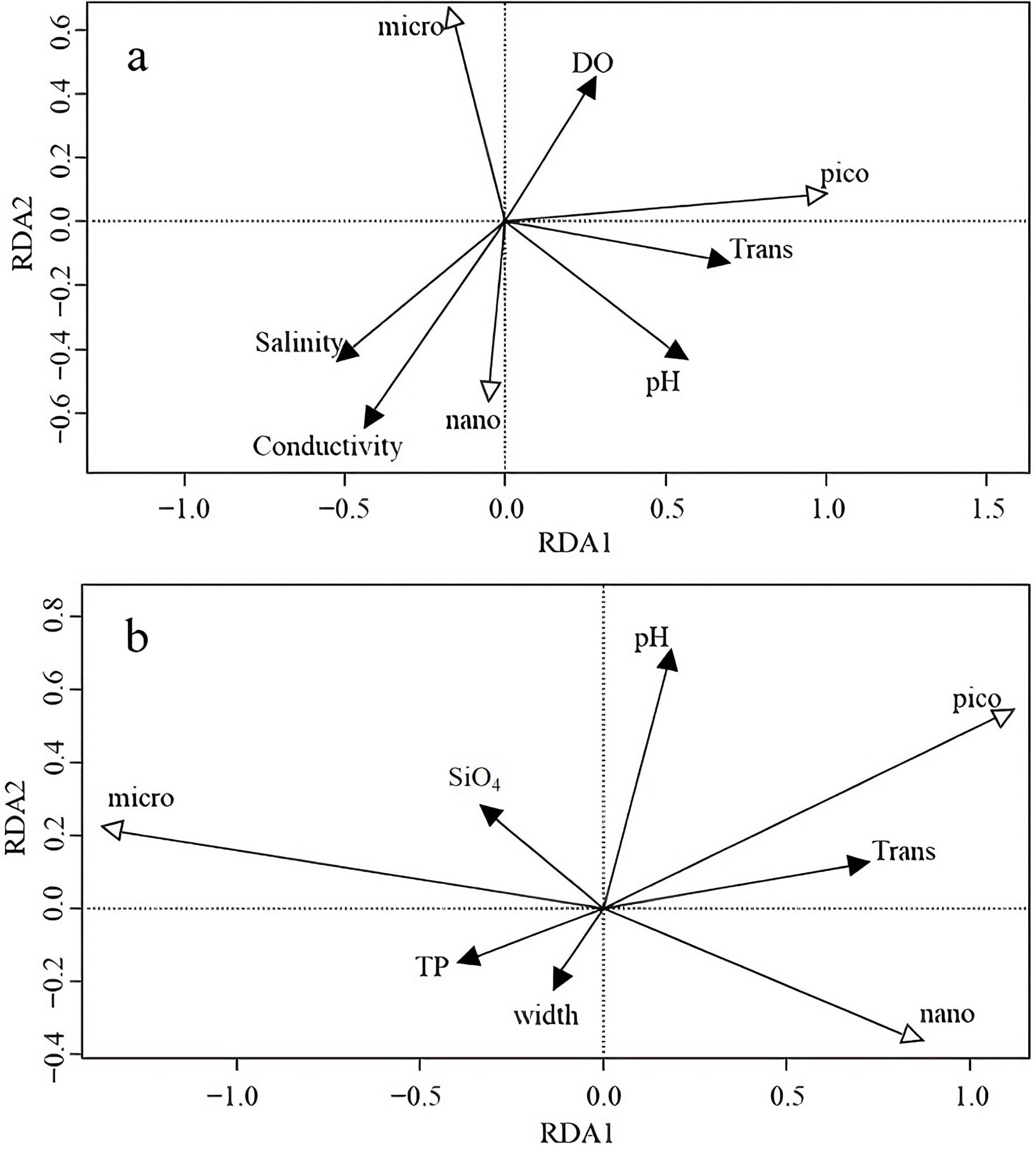

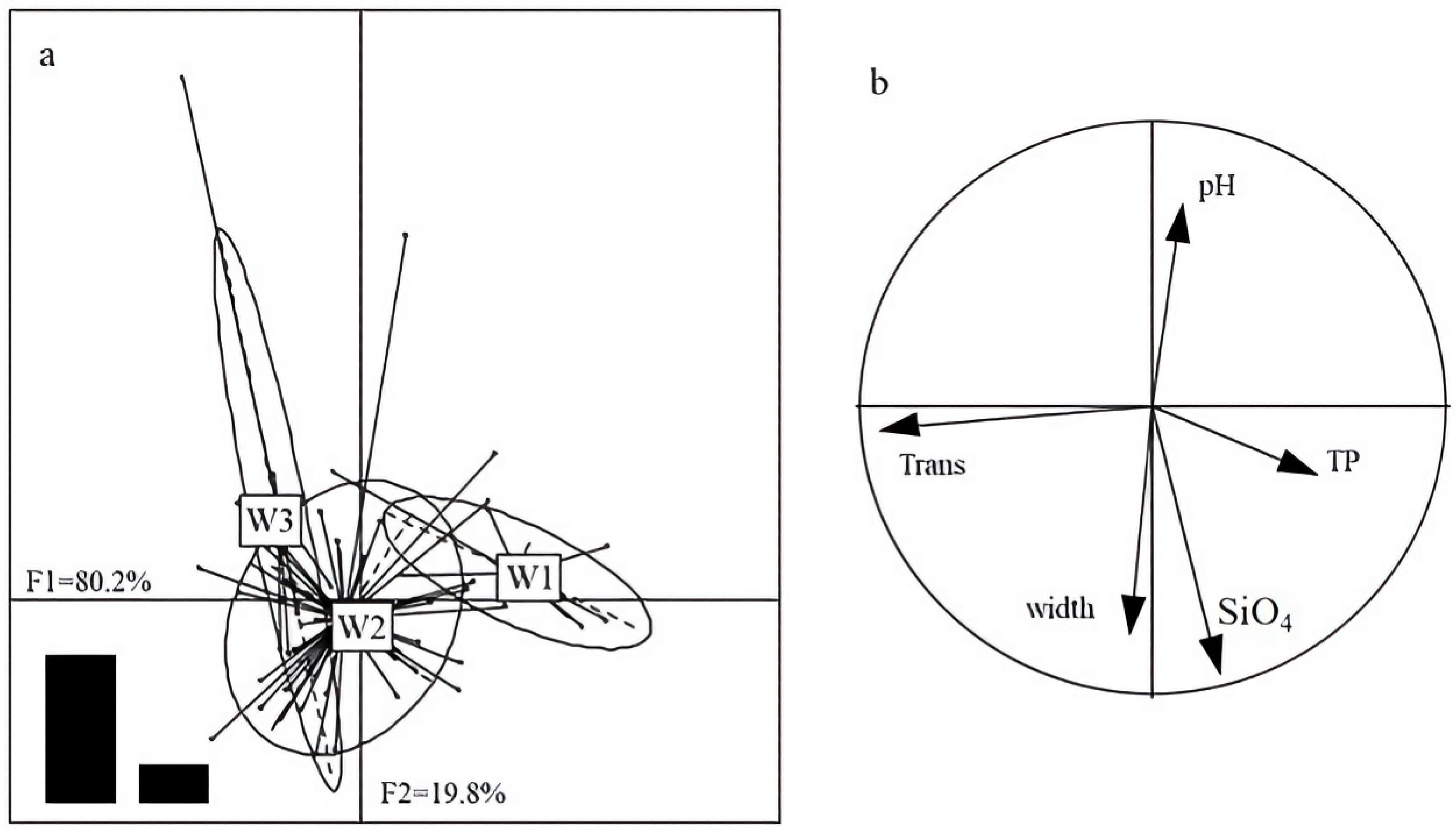

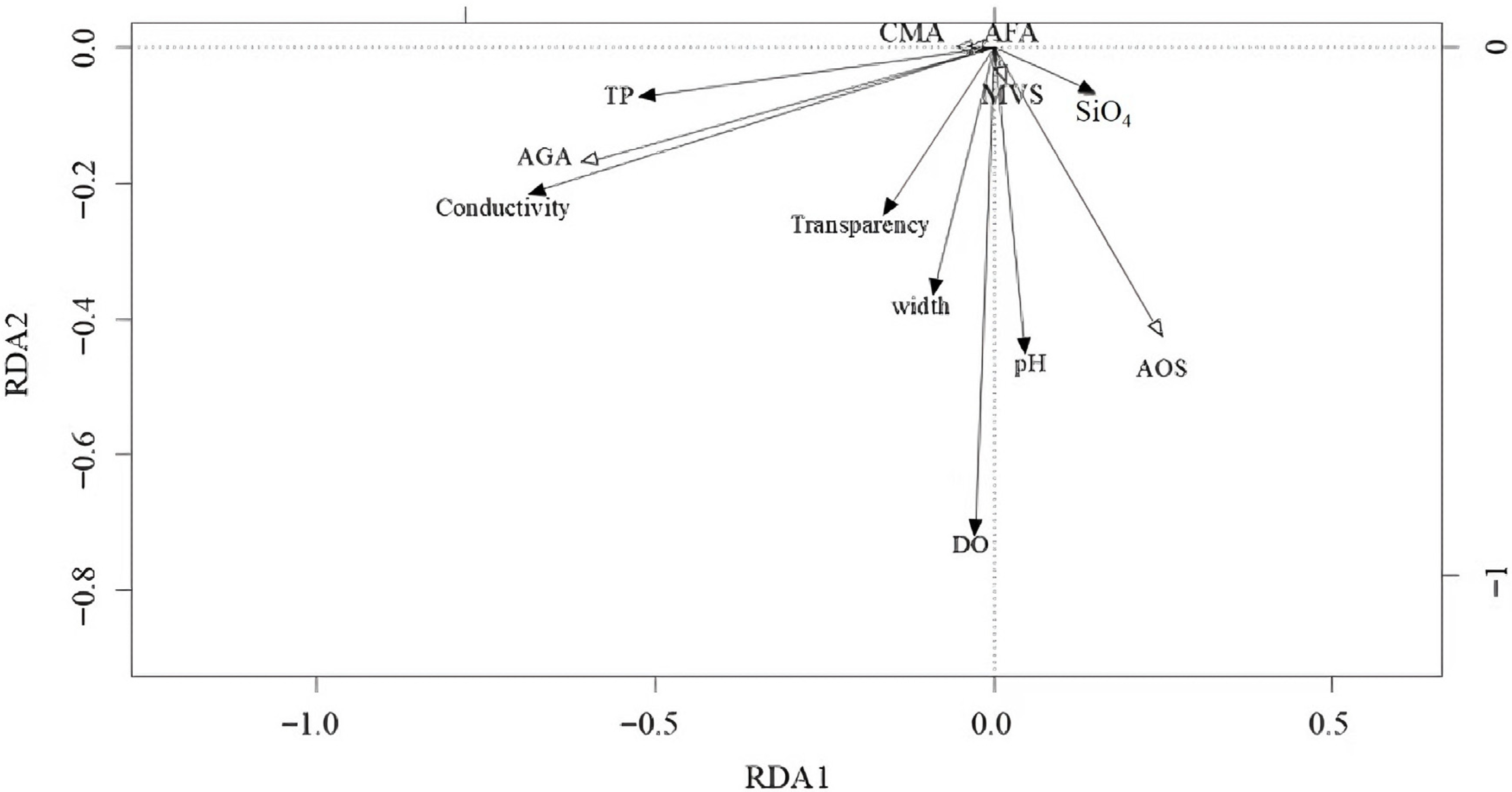

3.5. Degree of Redundancy Analysis

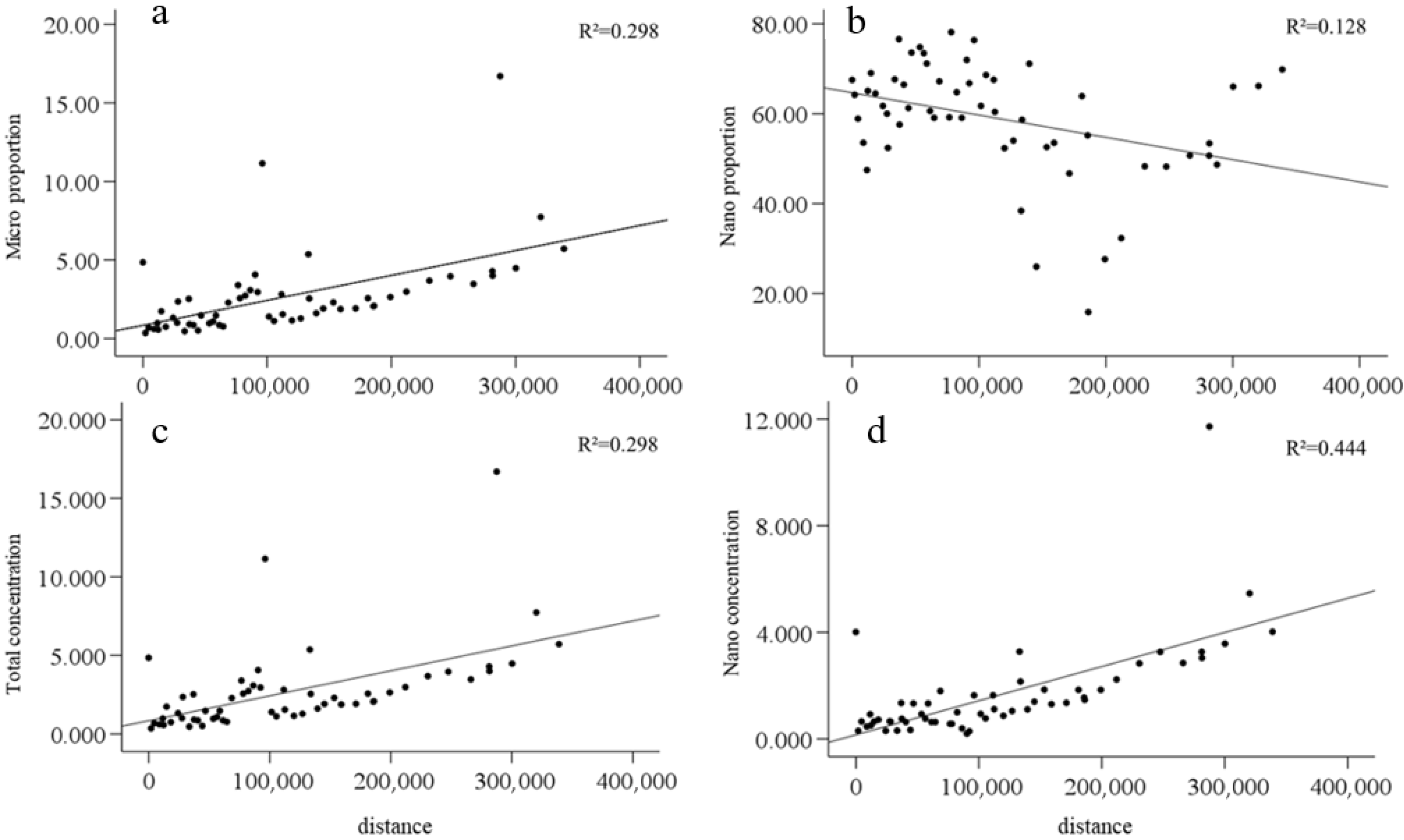

3.6. Relationship Between Chl-a Particle Size Composition and Distance of Phytoplankton

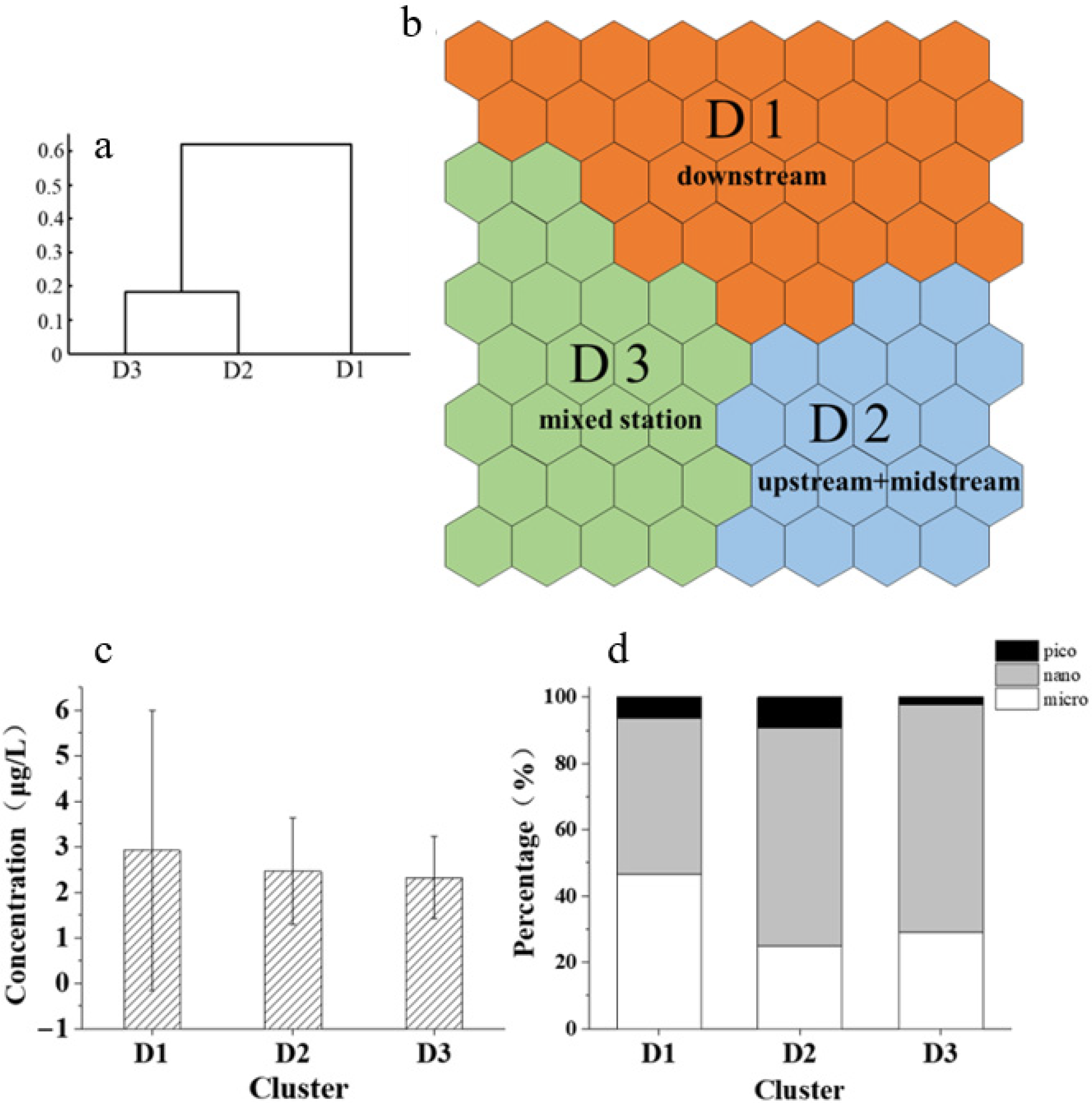

3.7. Predictive Analysis

3.8. Relationship Between Dominant Species and Size-Fractionated Chl-a

3.9. Relationship Between Dominant Taxa and Environmental Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatio-Temporal Characteristics of the Total Chl-a Concentration

4.2. Spatio-Temporal Characteristics of Phytoplankton Size Composition

4.3. Phytoplankton Size Structure as an Ecological Indicator in Fragmented Rivers

4.4. Predictive Analysis of Spatiotemporal Variation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alvarez-Fernandez, S.; Riegman, R. Chlorophyll in North Sea Coastal and Offshore Waters Does Not Reflect Long Term Trends of Phytoplankton Biomass. J. Sea Res. 2014, 91, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, F.; Castro, M.C. Chlorophylla of Size-Fractionated Phytoplankton at a Temporary Hypersaline Lake. Int. J. Salt Lake Res. 1996, 5, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelmakh, L.; Kovrigina, N.; Gorbunova, T. Phytoplankton Seasonal Dynamics under Conditions of Climate Change and Anthropogenic Pollution in the Western Coastal Waters of the Black Sea (Sevastopol Region). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksnes, D.L.; Egge, J.K. A Theoretical Model for Nutrient Uptake in Phytoplankton. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1991, 70, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litchman, E.; Klausmeier, C.A. Trait-Based Community Ecology of Phytoplankton. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2008, 39, 615–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xie, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, F.; Laws, E.A.; Huang, B. Examining the Size-Specific Photosynthesis-Irradiance Parameters and Relationship with Phytoplankton Types in a Subtropical Marginal Sea. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 130, 108094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padisák, J.; Soróczki-Pintér, É.; Rezner, Z. Sinking Properties of Some Phytoplankton Shapes and the Relation of Form Resistance to Morphological Diversity of Plankton—An Experimental Study. Hydrobiologia 2003, 500, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauly, D.; Christensen, V. Primary Production Required to Sustain Global Fisheries. Nature 1995, 376, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitari, R.R.; Anil, A.C. Estimation of Diatom and Dinoflagellate Cell Volumes from Surface Waters of the Northern Indian Ocean. Oceanologia 2017, 59, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, R.F.; Haraguchi, L.; Mcquaid, J.; Burger, J.M.; Lunga, P.M.; Stirnimann, L.; Samanta, S.; Roychoudhury, A.N.; Fawcett, S.E. Nanoplankton: The Dominant Vector for Carbon Export Across the Atlantic Southern Ocean in Spring. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadi3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.G.; Brzezinski, M.A.; Cohn, M.R.; Kramer, S.J.; Paul, N.; Sharpe, G.; Niebergall, A.K.; Gifford, S.; Cassar, N.; Marchetti, A. Size-Fractionated Primary Production Dynamics During the Decline Phase of the North Atlantic Spring Bloom. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2024, 38, e2023GB008019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, G.; Sun, J. Nanophytoplankton and Microphytoplankton in the Western Tropical Pacific Ocean: Its Community Structure, Cell Size and Carbon Biomass. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1147271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardikar, R.; Ram, A.; Parthipan, V. Distribution of Size-Fractionated Phytoplankton Biomass from the Anthropogenically Stressed Tropical Creek (Thane Creek, India). Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2021, 41, 101577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaneesh, K.M.; Mitbavkar, S.; Anil, A.C. Dynamics of Size-Fractionated Phytoplankton Biomass in a Monsoonal Estuary: Patterns and Drivers for Seasonal and Spatial Variability. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 207, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, W.; Wu, N.; Lai, Z.; Du, W.; Jia, H.; Ge, D.; Wang, C. Spatio-Temporal Patterns and Predictions of Size-Fractionated Chlorophyll a in a Large Subtropical River, China. J. Freshw. Ecol. 2020, 35, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, W.; Yang, W.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Gao, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, C. Phytoplankton Species Richness as an Ecological Indicator in a Subtropical, Human-Regulated, Fragmented River. River Res. Appl. 2023, 39, 718–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.V.; Stanford, J.A. The Serial Discontinuity Concept: Extending the Model to Floodplain Rivers. Regul. Rivers Res. Manag. 1995, 10, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.; Stanford, J. The Serial Discontinuity Concept Of Lotic Ecosystems. Dyn. Lotic Ecosyst. 1983, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.-L.; Feng, P. Serial Discontinuity Concept and Its Development Status in River Ecosystem Research. Adv. Water Sci. 2005, 16, 758–762. [Google Scholar]

- Stanford, J.A.; Ward, J.V. Revisiting the Serial Discontinuity Concept. Regul. Rivers Res. Manag. 2001, 17, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, L.E.; Jones, N.E. A Test of the Serial Discontinuity Concept: Longitudinal Trends of Benthic Invertebrates in Regulated and Natural Rivers of Northern Canada. River Res. Appl. 2016, 32, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasong, T. Variation Analysis Method for Hydrologic Annual Distribution Homogeneity Based on Gini Coefficient. A Case Study of Runoff Series at Longchun Station in Dongjiang River Basin. J. Hydroelectr. Eng. 2012, 31, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Ge, D.; Yang, W.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Gao, Y.; Mai, Y.; Wang, C. Taxa Composition and Ecological Traits of Filamentous Diatoms in a Regulated Fragmented River, China. Fundam. Appl. Limnol. 2022, 195, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.J.; Lai, Z.N.; Wang, C. Temporal and Spatial Patterns of Phytoplankton Species Richness in the Pearl River Delta. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 3816–3827. [Google Scholar]

- Toolbox, S.; Vesanto, J. Neural Network Tool for Data Mining: SOM Toolbox. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Tool Environments and Development Methods for Intelligent Systems (TOOLMET2000), Oulu, Finland, 13–14 April 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ultsch, A. Self-Organizing Neural Networks for Visualisation and Classification. In Information and Classification; Opitz, O., Lausen, B., Klar, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1993; pp. 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D.L.; Bouldin, D.W. A Cluster Separation Measure. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1979, PAMI-1, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuth, H.; Beale, M.; Hagan, M. Neural Network Toolbox, For Use with MATLAB; The MathWorks, Inc.: Natick, MA, USA, 2000; p. 415. [Google Scholar]

- Alhoniemi, E.; Himberg, J.; Parhankangas, J.; Vesanto, J. SOM Toolbox. Online Documentation. 2000. Available online: http://www.cis.hut.fi/projects/somtoolbox (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Sneath, P.H.A.; Sokal, R.R. Numerical Taxonomy. Nature 1962, 193, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihaka, R.; Gentleman, R. R: A Language for Data Analysis and Graphics. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 1996, 5, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete-Ortega, M.; Calvo-Díaz, A.; Graña, R.; Mouriño-Carballido, B.; Marañón, E. Effect of Environmental Forcing on the Biomass, Production and Growth Rate of Size-Fractionated Phytoplankton in the Central Atlantic Ocean. J. Mar. Syst. 2011, 88, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poff, N.L.; Olden, J.D.; Merritt, D.M.; Pepin, D.M. Homogenization of Regional River Dynamics by Dams and Global Biodiversity Implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 5732–5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, C.M.; Freeman, M.C.; Freeman, B.J. Regional Effects of Hydrologic Alterations on Riverine Macrobiota in the New World: Tropical-Temperate Comparisons: The massive scope of large dams and other hydrologic modifications in the temperate New World has resulted in distinct regional trends of biotic impoverishment. While neotropical rivers have fewer dams and limited data upon which to make regional generalizations, they are ecologically vulnerable to increasing hydropower development and biotic patterns are emerging. BioScience 2000, 50, 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, D.M.; Wolock, D.M.; Meador, M.R. Alteration of Streamflow Magnitudes and Potential Ecological Consequences: A Multiregional Assessment. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 9, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, F.; Attermeyer, K.; Ayala, A.I.; Fischer, H.; Kirchesch, V.; Pierson, D.C.; Weyhenmeyer, G.A. Phytoplankton Gross Primary Production Increases along Cascading Impoundments in a Temperate, Low-Discharge River: Insights from High Frequency Water Quality Monitoring. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriqi, A.; Pinheiro, A.N.; Sordo-Ward, A.; Bejarano, M.D.; Garrote, L. Ecological Impacts of Run-of-River Hydropower Plants—Current Status and Future Prospects on the Brink of Energy Transition. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 142, 110833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.B.; Jung, M.-K.; Tsang, Y.F.; Kwon, H.-H. Stochastic Modeling of Chlorophyll-a for Probabilistic Assessment and Monitoring of Algae Blooms in the Lower Nakdong River, South Korea. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 400, 123066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimambo, O.N.; Chikoore, H.; Gumbo, J.R.; Msagati, T.A.M. Retrospective Analysis of Chlorophyll-a and Its Correlation with Climate and Hydrological Variations in Mindu Dam, Morogoro, Tanzania. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, W.; Wu, Y.; Kidwai, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, J. Spatial and Temporal Variations of Nutrients and Chlorophyll a in the Indus River and Its Deltaic Creeks and Coastal Waters (Northwest Indian Ocean, Pakistan). J. Mar. Syst. 2021, 218, 103525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Taani, A.A. Trend Analysis in Water Quality of Al-Wehda Dam, North of Jordan. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014, 186, 6223–6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Hu, C.; Yang, W.; Wu, N.; Liu, Q.; Wei, J.; Wang, C. Phytoplankton Species Composition as Bioindicator in the Largest Fragmented Channel of the Pearl River, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lai, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Lek, S.; Hong, Y.; Tan, X.; Li, J. Population Ecology of Aulacoseira Granulata in Xijiang River. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2012, 32, 4793–4802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, L.S.; de Souza Lopes, A.A.; Colares, L.; Palheta, L.; de Souza Menezes, M.; Fernandes, L.M.; Dunck, B. Dam Promotes Downriver Functional Homogenization of Phytoplankton in a Transitional River-Reservoir System in Amazon. Limnology 2021, 22, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabater-Liesa, L.; Ginebreda, A.; Barceló, D. Shifts of Environmental and Phytoplankton Variables in a Regulated River: A Spatial-Driven Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 968–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.; Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Ge, J. Long-Term Response of an Estuarine Ecosystem to Drastic Nutrients Changes in the Changjiang River during the Last 59 Years: A Modeling Perspective. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1012127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, T.R.; Tiwari, N.K.; Kumari, S.; Ray, A.; Manna, R.K.; Bayen, S.; Roy, S.; Das Gupta, S.; Ramteke, M.H.; Swain, H.S.; et al. Variation of Aulacoseira Granulata as an Eco-Pollution Indicator in Subtropical Large River Ganga in India: A Multivariate Analytical Approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 37498–37512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasiewicz, P.; Belka, K.; Łapińska, M.; Ławniczak, K.; Prus, P.; Adamczyk, M.; Buras, P.; Szlakowski, J.; Kaczkowski, Z.; Krauze, K.; et al. Over 200,000 Kilometers of Free-Flowing River Habitat in Europe Is Altered Due to Impoundments. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, E.P.; Jenkins, C.N.; Heilpern, S.; Maldonado-Ocampo, J.A.; Carvajal-Vallejos, F.M.; Encalada, A.C.; Francisco Rivadeneira, J.; Hidalgo, M.; Canas, C.M.; Ortega, H.; et al. Fragmentation of Andes-to-Amazon Connectivity by Hydropower Dams. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaao1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; He, Q.; Li, H.; Xu, Q.; Cheng, C. Response of CO2 and CH4 Transport to Damming: A Case Study of Yulin River in the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Environ. Res. 2022, 208, 112733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, K.; Jang, M.H.; Joo, G.J. Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Phytoplankton Communities along a Regulated River System, the Nakdong River, Korea. Hydrobiologia 2002, 470, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wu, N.; Li, W.; Liu, Q.; Lai, Z.; Fohrer, N. Curved Filaments of Aulacoseira Complex as Ecological Indicators in the Pearl River, China. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 118, 106722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Distance | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total concentration | dry period | 0.112 |

| wet period | 0.546 ** | |

| Micro concentration | dry period | 0.192 |

| wet period | 0.181 | |

| Nano concentration | dry period | 0.024 |

| wet period | 0.666 ** | |

| Pico concentration | dry period | −0.057 |

| wet period | 0.087 | |

| Micro proportion | dry period | 0.468 ** |

| wet period | −0.027 | |

| Nano proportion | dry period | −0.357 ** |

| wet period | 0.119 | |

| Pico proportion | dry period | −0.228 |

| wet period | −0.219 |

| Time | Size-Fractionated Chl-a | Category | Algal Taxa | Biomass Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018.11 | nano- and micro-Chl-a | Bacillariophyceae | Aulacoseira granulate (AGA) | 66% |

| micro-Chl-a | Bacillariophyceae | Aulacoseira fennoscandica (AFA) | 1% | |

| nano- and micro-Chl-a | Bacillariophyceae | Melosira varians (MVS) | 8% | |

| nano- and micro-Chl-a | Bacillariophyceae | Cyclotella meneghiniana (CMA) | 1% | |

| 2019.7 | nano- and micro-Chl-a | Bacillariophyceae | Aulacoseira granulata | 25% |

| micro-Chl-a | Cyanophyta | Anabaena oscillarioides (AOS) | 11% | |

| nano- and micro-Chl-a | Bacillariophyceae | Cyclotella meneghiniana | 1% | |

| nano- and micro-Chl-a | Bacillariophyceae | Melosira varians | 8% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sang, D.; Wei, J.; Hu, C.; Liu, Q.; Sun, J.; Wang, C. Phytoplankton Size as an Ecological Bioindicator in a Subtropical Fragmented River, China. Water 2025, 17, 3513. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243513

Sang D, Wei J, Hu C, Liu Q, Sun J, Wang C. Phytoplankton Size as an Ecological Bioindicator in a Subtropical Fragmented River, China. Water. 2025; 17(24):3513. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243513

Chicago/Turabian StyleSang, Deyu, Jingxin Wei, Caiqin Hu, Qianfu Liu, Jinhui Sun, and Chao Wang. 2025. "Phytoplankton Size as an Ecological Bioindicator in a Subtropical Fragmented River, China" Water 17, no. 24: 3513. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243513

APA StyleSang, D., Wei, J., Hu, C., Liu, Q., Sun, J., & Wang, C. (2025). Phytoplankton Size as an Ecological Bioindicator in a Subtropical Fragmented River, China. Water, 17(24), 3513. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243513