Hydrochemical Characteristics and Nitrate Health Risk Assessment in a Shallow Aquifer: Insights from a Typical Low-Mountainous Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

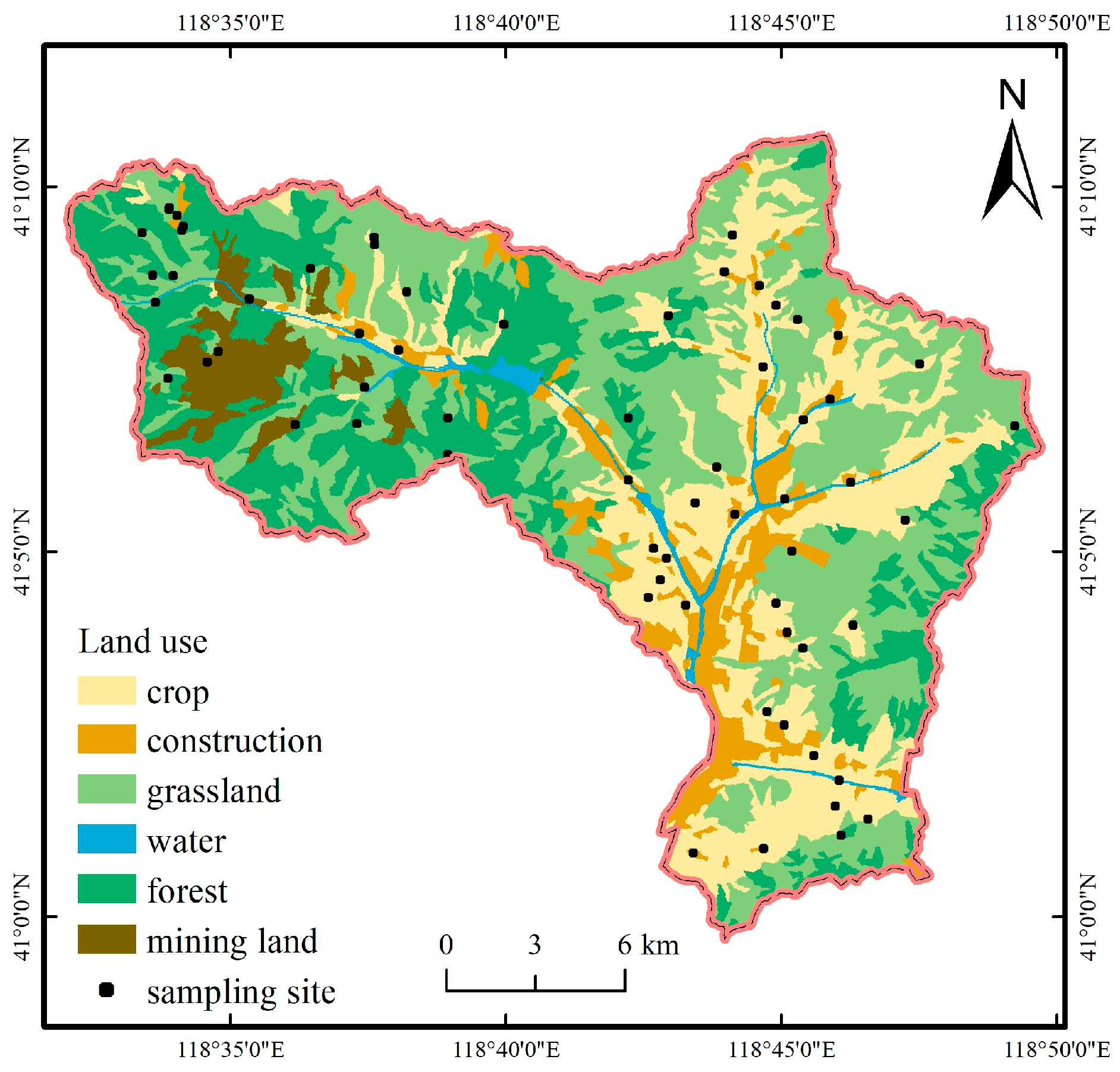

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sample Collection and Laboratory Analysis

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Health Risk Assessment

2.4.1. Core Formulas

2.4.2. Parameter Definition and Values

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Groundwater Hydrochemical Composition Analysis

3.1.1. Statistical Characteristics of Hydrochemical Parameters

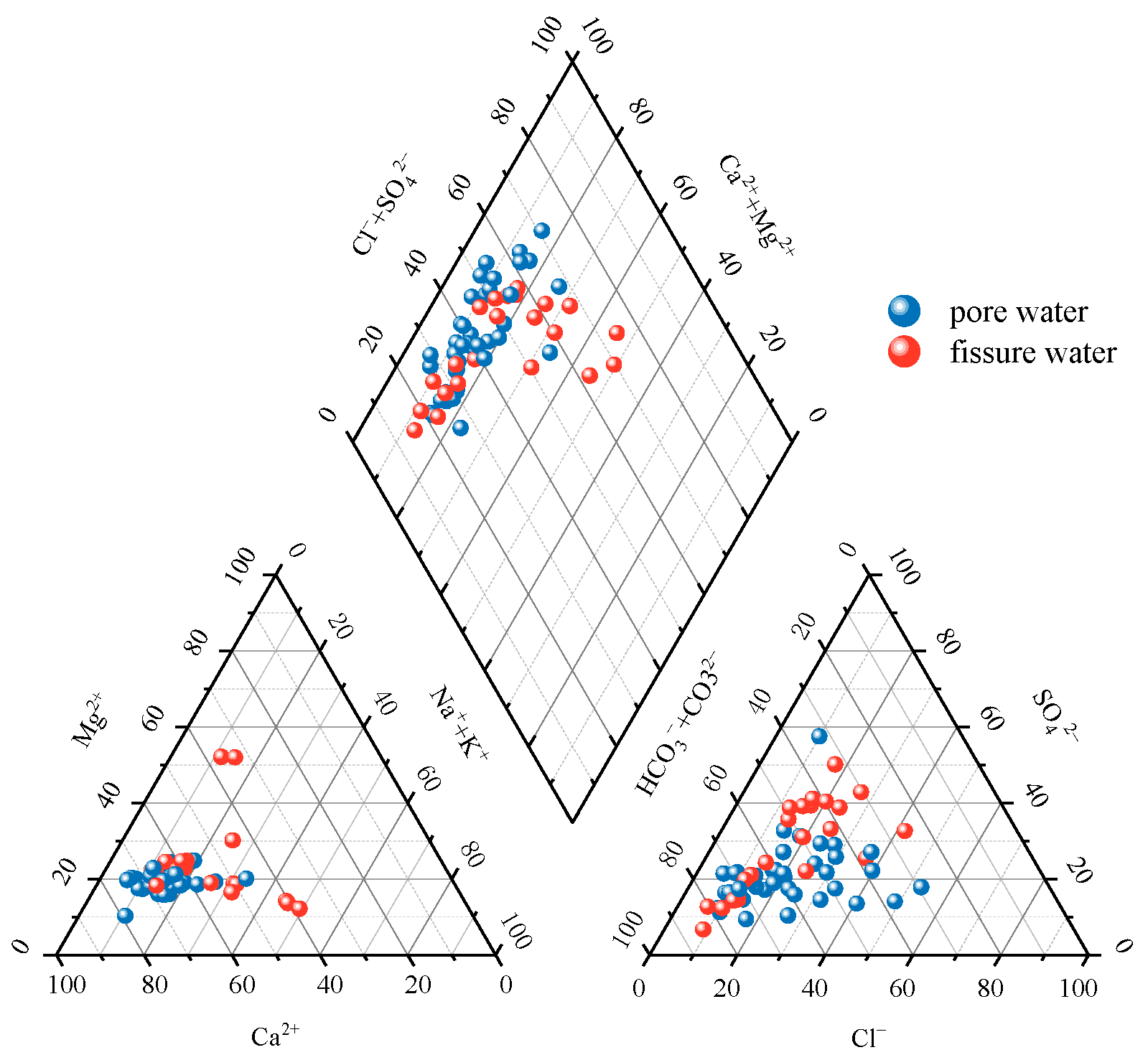

3.1.2. Groundwater Hydrochemical Types

3.2. Correlation Analysis and Principal Component Analysis

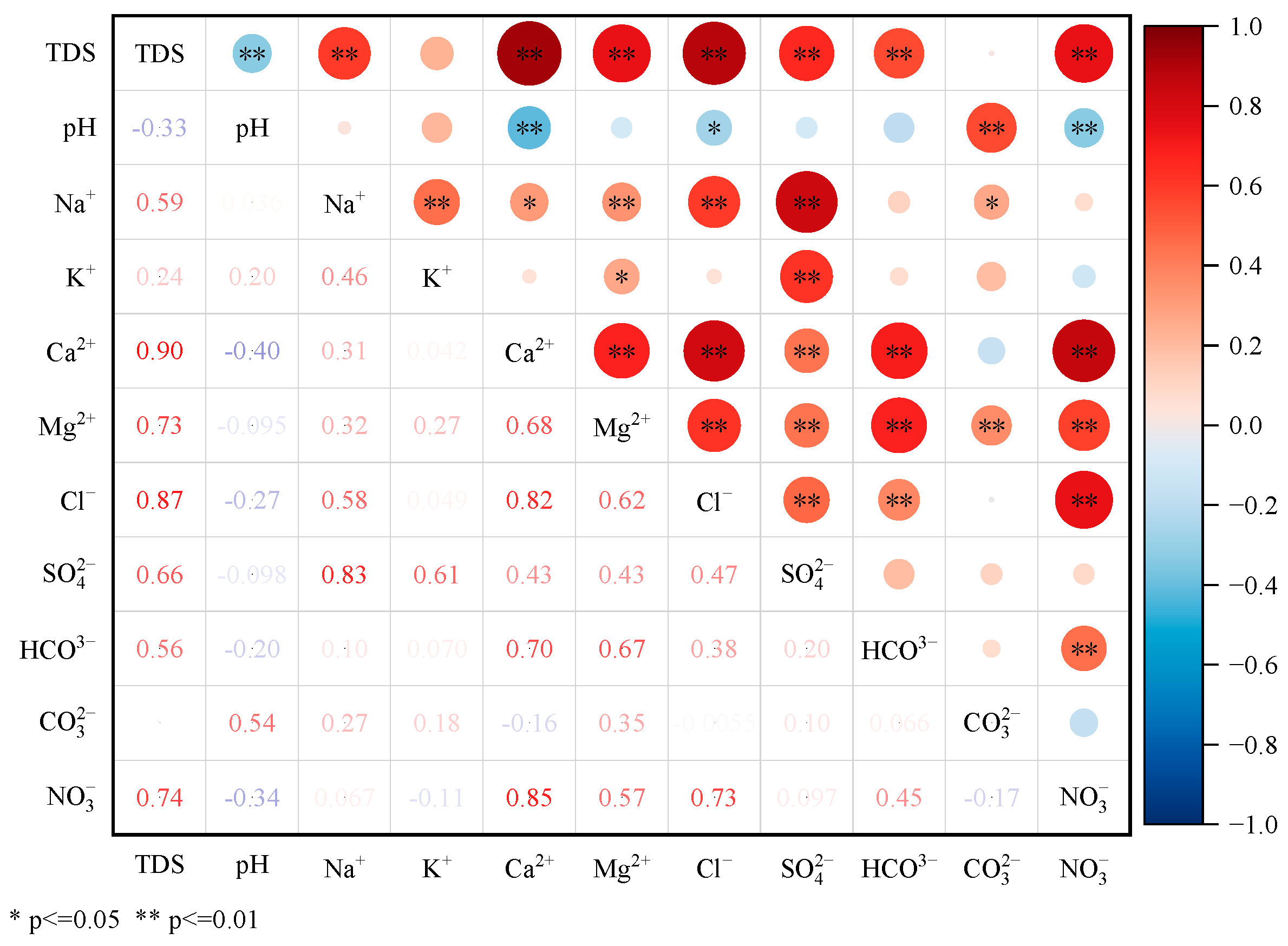

3.2.1. Correlation Analysis

3.2.2. Principal Component Analysis

3.3. Natural Controls on Groundwater Hydrochemistry

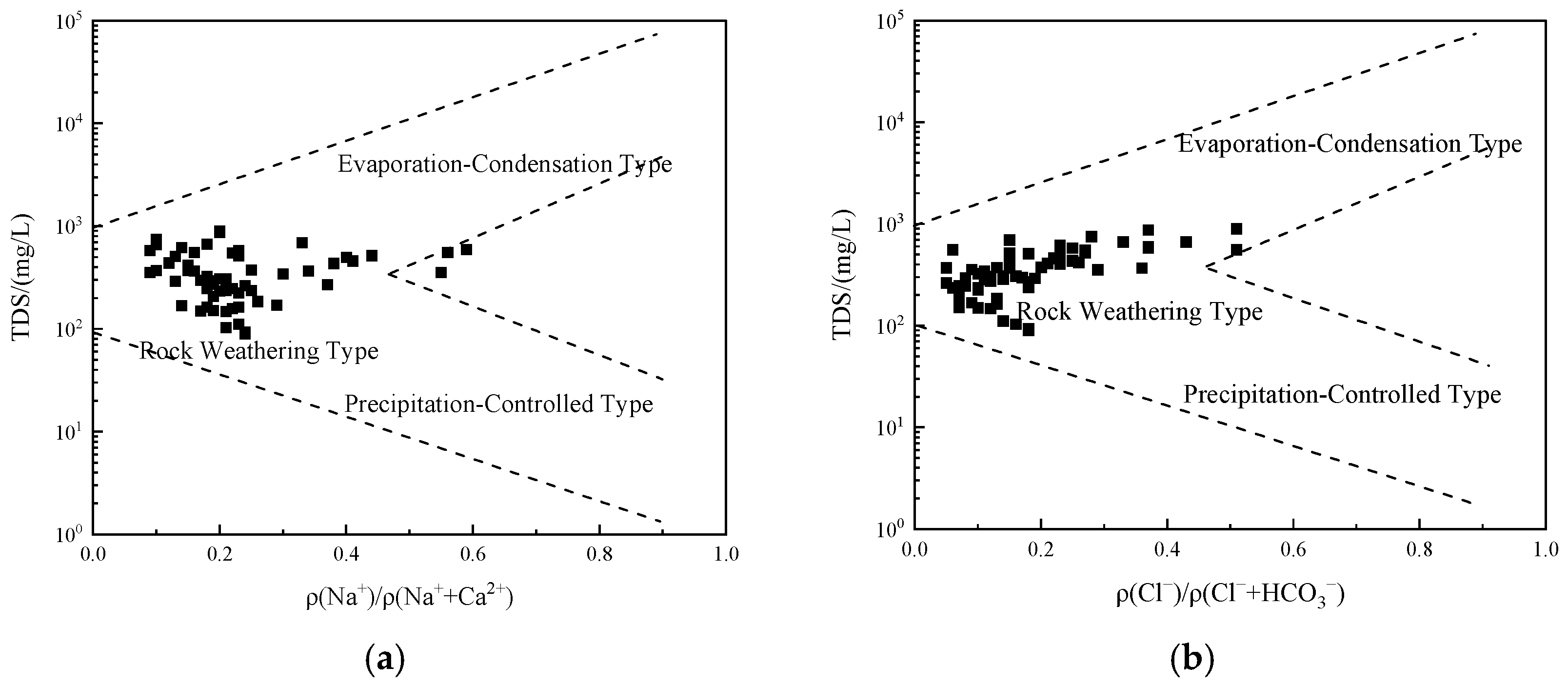

3.3.1. Gibbs Diagram Analysis

3.3.2. Ion Ratio Analysis

3.3.3. Chlor-Alkaline Index (CAI)

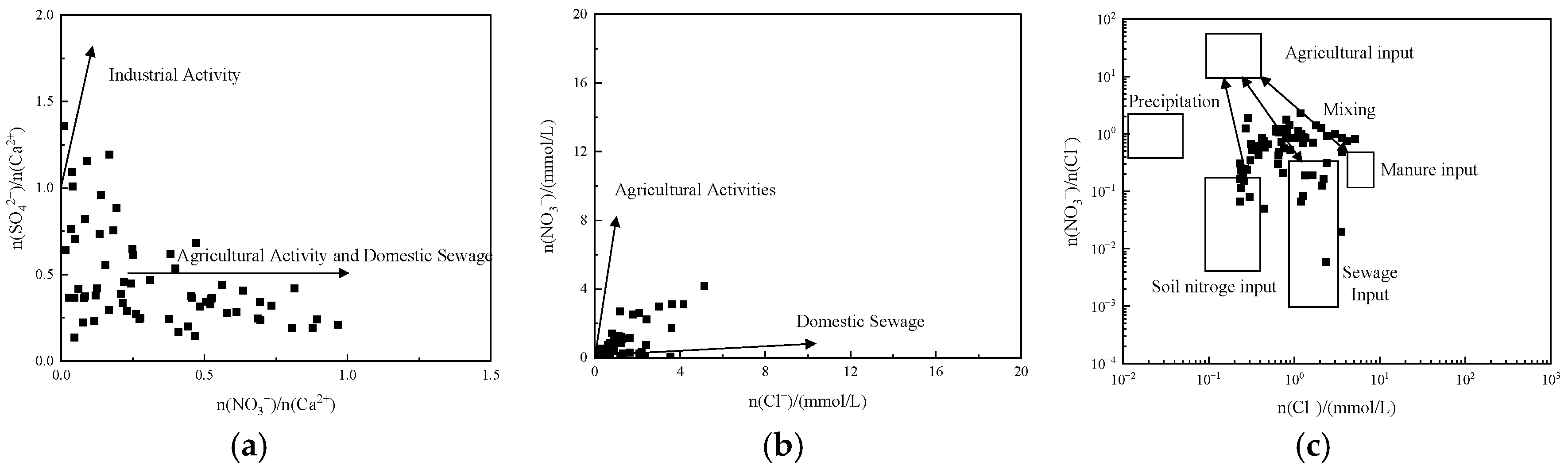

3.4. Anthropogenic Controls on Groundwater Hydrochemistry

3.5. Factors for Controlling Nitrate and Health Risk Assessment

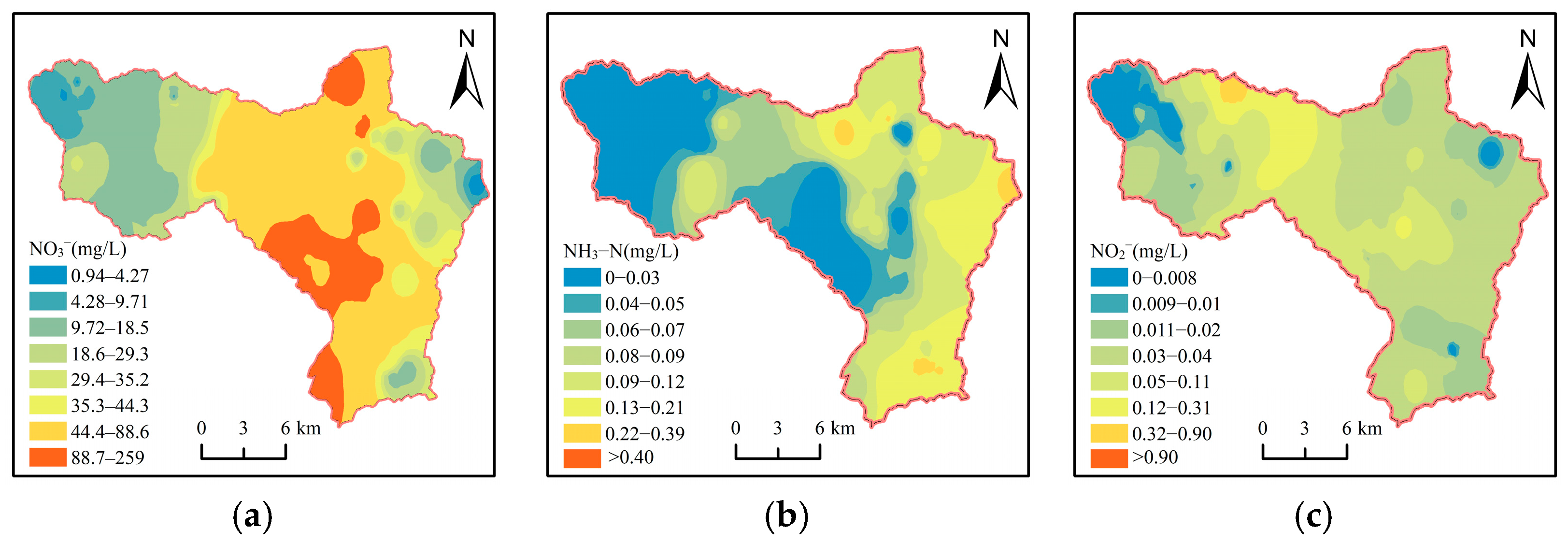

3.5.1. Spatial Distribution of Nitrate

3.5.2. Controlling Factors of Nitrate Evolution

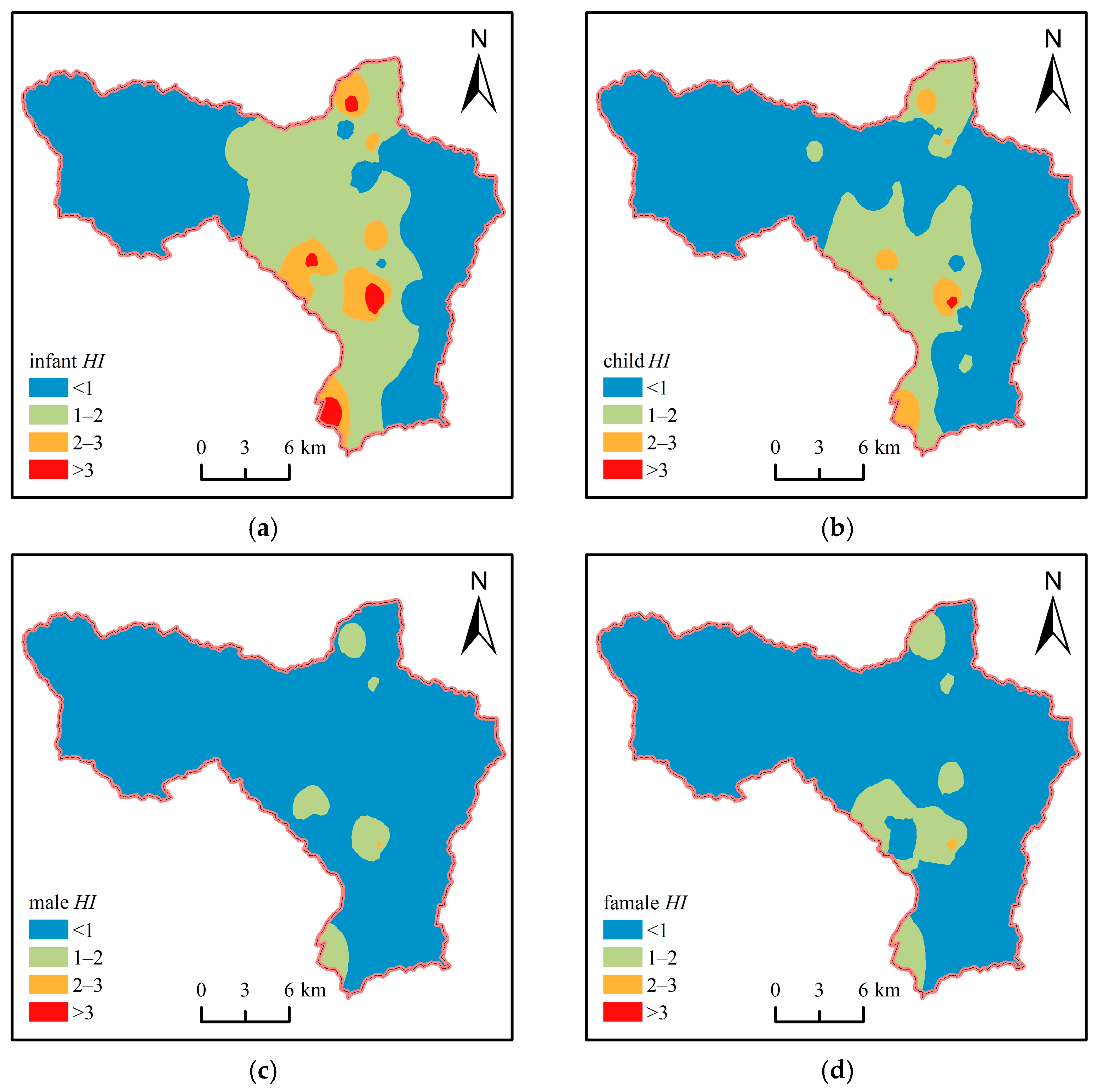

3.5.3. Health Risk Assessment of Nitrate

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ling, Z.; Shu, L.; Wang, D.; Yin, X.; Lu, C.; Liu, B. Characteristics of groundwater drought and its propagation dynamics with meteorological drought in the Sanjiang Plain, China: Irrigated versus nonirrigated areas. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 54, 101911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, L.; Duan, L.; Huang, J. Topical Collection: Groundwater recharge and discharge in arid and semi-arid areas of China. Hydrogeol. J. 2021, 29, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everest, T.; Özcan, H. Applying multivariate statistics for identification of groundwater resources and qualities in NW Turkey. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Gao, Z.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Teng, Y.; Liu, C.; Xu, C. Hydrochemical analysis and quality assessment of groundwater in southeast North China Plain using hydrochemical, entropy-weight water quality index, and GIS techniques. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shi, Z.; Wang, G.; Liu, F. Evaluating Spatiotemporal Variations of Groundwater Quality in Northeast Beijing by Self-Organizing Map. Water 2020, 12, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasnia, A.; Yousefi, N.; Mahvi, A.H.; Nabizadeh, R.; Radfard, M.; Yousefi, M.; Alimohammadi, M. Evaluation of groundwater quality using water quality index and its suitability for assessing water for drinking and irrigation purposes: Case study of Sistan and Baluchistan province (Iran). Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2019, 25, 988–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Guo, H.; Zhan, Y. Groundwater hydrochemical characteristics and processes along flow paths in the North China Plain. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2013, 70, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Song, Y.; Li, Y.-C.; Wei, W.; Zhao, G.-H.; Wang, X.-D.; Huang, J.-M. Hydrochemical characteristics and control factors of shallow groundwater in Anqing section of the Yangtze River Basin. Huan Jing Ke Xue 2024, 45, 1525–1538. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Fang, Y.; Hu, H.; Wang, W. Variation and reason analysis of groundwater hydrochemical characteristics in Beiluhe Basin, Qinghai–Tibet Plateau during a freezing–thawing period. J. Water Clim. Change 2022, 13, 2799–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Cao, S.; Hao, Q.; Liu, S.; Kong, X.; Han, Z. Evolution of groundwater hydrochemical characteristics and formation mechanism during groundwater recharge: A case study in the Hutuo River alluvial–pluvial fan, North China Plain. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, D.; Meng, X.; Wen, X.; Wu, J.; Yu, H.; Wu, M.; Zhou, T. Hydrochemical characteristics, quality and health risk assessment of nitrate enriched coastal groundwater in northern China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 403, 136872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijay-Singh; Craswell, E. Fertilizers and nitrate pollution of surface and ground water: An increasingly pervasive global problem. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, B.T.; Hitt, K.J. Vulnerability of Shallow Groundwater and Drinking-Water Wells to Nitrate in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 7834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zou, Y.; Pan, H.; Zhang, R.; Gu, B. Safeguarding Groundwater Nitrate within Regional Boundaries in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Ge, Y.; Chang, S.X.; Luo, W.; Chang, J. Nitrate in groundwater of China: Sources and driving forces. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tang, C.; Sakura, Y.; Yu, J.; Fukushima, Y. Nitrate pollution from agriculture in different hydrogeological zones of the regional groundwater flow system in the North China Plain. Hydrogeol. J. 2005, 13, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasri, M.N. Nitrate contamination of groundwater: A conceptual management framework. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2007, 27, 220–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.A.; David, M.B.; Galloway, J.N.; Goodale, R.H.C.L.; Ward, M.H. Excess Nitrogen in the U.S. Environment: Trends, Risks, and Solutions; Issues in Ecology; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2012.

- Liu, G.D.; Wu, W.L.; Zhang, J. Regional differentiation of non-point source pollution of agriculture-derived nitrate nitrogen in groundwater in northern China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2005, 107, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Du, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Deng, Y.; Li, Q. Source-oriented health risk assessment of groundwater nitrate by using EMMTE coupled with HHRA model. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 934, 173283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. The analysis of groundwater nitrate pollution and health risk assessment in rural areas of Yantai, China. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Zhao, X.; Teng, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Zuo, R. Groundwater nitrate pollution and human health risk assessment by using HHRA model in an agricultural area, NE China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 137, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhdarpoor, A.; Radfard, M.; Pakdel, M.; Abbasnia, A.; Yousefi, M. Assessing fluoride and nitrate contaminants in drinking water resources and their health risk assessment in a Semiarid region of Southwest Iran. Desalination Water Treat. 2019, 149, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, H.; Qian, H.; Gao, Y. Assessing Nitrate and Fluoride Contaminants in Drinking Water and Their Health Risk of Rural Residents Living in a Semiarid Region of Northwest China. Expo. Health 2016, 9, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, M.R.; Fallahizadeh, S.; Rajabi, S.; Gharehchahi, E.; Rahimi, N.; Azhdarpoor, A. Non-carcinogenic health risk assessment and Monte Carlo simulation of nitrite, nitrate, and fluoride in drinking water of Yasuj, Iran. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2024, 104, 6339–6357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Liu, J.; Hu, S.; Wang, J. Distribution Characteristics of High-background elements and Assessment of Ecological Element Activity in typical profiles of Ultramafic Rock area. Toxics 2025, 13, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Liu, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Tang, Z.; Wang, G.; Yu, T.C. Ecological vulnerability assessment and driving force analysis of small watersheds in Hilly Regions using sensitivity-resilience-pressure modeling. J. Groundw. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Nematollahi, M.J.; Ebrahimi, P.; Ebrahimi, M. Evaluating Hydrogeochemical Processes Regulating Groundwater Quality in an Unconfined Aquifer. Environ. Process. 2016, 3, 1021–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, M.J.; Ebrahimi, P.; Razmara, M.; Ghasemi, A. Hydrogeochemical investigations and groundwater quality assessment of Torbat-Zaveh plain, Khorasan Razavi, Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Su, C.; Liu, W.; Xie, X. Understanding Surface Water-Groundwater Conversion Relationship and Associated Hydrogeochemistry Evolution in the Upper Reaches of Luan River Basin, North China. J. Earth Sci. 2024, 35, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, R. Human Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Groundwater in the Luan River Catchment within the North China Plain. Geofluids 2020, 2020, 8391793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Hu, S.; Shi, J.; Li, X.; Song, D.; Niu, X. Distribution characteristics, source identification and health risk assessment of heavy metals in surface water and groundwater: A case study in mining-affected areas. Front. Water 2025, 7, 1639009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Zhou, X.; Shi, J. Heavy metal contamination and health risk assessment in Critical Zone of Luan River Catchment in the North China Plain. Geochem. Explor. Environ. Anal. 2018, 18, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 14848–2017; China’s Groundwater Quality Standard. Standardization Administration of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2017.

- Tociu, C.; Marcu, E.; Ciobotaru, I.E.; Maria, C. Risk assessment of population exposure to nitrates/nitrites in groundwater: A case study approach. ECOTERRA–J. Environ. Res. Prot. 2016, 13, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Gu, H.; Lan, S.; Wang, M.; Chi, B. Human health risk assessment and sources analysis of nitrate in shallow groundwater of the Liujiang basin, China. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2018, 24, 1515–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y. Health Risk Assessment of Nitrate Contamination in Groundwater: A Case Study of an Agricultural Area in Northeast China. Water Resour. Manag. 2013, 27, 3025–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Qian, H.; Xu, P.; Li, W.; Liu, R. Effect of hydrogeological conditions on groundwater nitrate pollution and human health risk assessment of nitrate in Jiaokou Irrigation District. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Hu, X.; Li, B.; Wu, P.; Cai, X.; Luo, Y.; Deng, X.; Jiang, M. A Groundwater Quality Assessment Model for Water Quality Index: Combining Principal Component Analysis, Entropy Weight Method, and Coefficient of Variation Method for Dimensionality Reduction and Weight Optimization, and Its Application. Water Environ. Res. 2024, 96, 10614303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R.K.; Ramanathan, A.; Parthasarathy, P.; Kumar, A. Hydrochemical characteristics of groundwater in the plains of Phalgu River in Gaya, Bihar, India. Arab. J. Geosci. 2013, 6, 3257–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Gao, Z.; Chen, Q.; Li, F. Hydrochemical characteristics and water quality assessment of groundwater in the Yishu River basin. Acta Geophys. 2020, 68, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.M.; Luo, Y.Y.; Fang, Y.Z.; Hou, Y.S. Hydrogeochemical Mechanism of the Petroleum Hydrocarbon Pollution in Karst Fissure Groundwater system. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Energy and Environmental Engineering, Shenzhen, China, 28–29 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzah, Z.; Aris, A.Z.; Ramli, M.F.; Juahir, H.; Sheikhy Narany, T. Groundwater quality assessment using integrated geochemical methods, multivariate statistical analysis, and geostatistical technique in shallow coastal aquifer of Terengganu, Malaysia. Arab. J. Geosci. 2017, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakis, N.; Mattas, C.; Pavlou, A.; Patrikaki, O.; Voudouris, K. Multivariate statistical analysis for the assessment of groundwater quality under different hydrogeological regimes. Environ. Earth Ences 2017, 76, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussaoui, T.; Derdour, A.; Abdelkarim, B.; Said, B.; Hosni, A.; Reghais, A.; De-Los-Santos, M.B. A novel comprehensive approach to soil and water conservation: Integrating morphometric analysis, WSA, PCA, and CoDA-PCA in the Naama sub-basins case study, Southwest of Algeria. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.C.; Satpute, S.; Prasad, V. Remote sensing and GIS-based watershed prioritization for land and water conservation planning and management. Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 88, 233–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traore, A.; Mao, X.; Traore, A.; Yakubu, Y.; Sidibe, A.M. Multivariate Statistical Analysis of Dominating Groundwater Mineralization and Hydrochemical Evolution in Gao, Northern Mali. J. Earth Sci. 2024, 35, 1692–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Tang, C.; Song, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y. Identifying the hydrochemical characteristics of rivers and groundwater by multivariate statistical analysis in the Sanjiang Plain, China. Appl. Water Sci. 2016, 6, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassi, L. Investigation by multivariate analysis of groundwater composition in a multilayer aquifer system from North Africa: A multi-tracer approach. Appl. Geochem. 2011, 26, 1386–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, M.; Li, X.; Qi, J.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, J.; Yu, L.; Zhao, R. Hydrochemical Characteristics and Multivariate Statistical Analysis of Natural Water System: A Case Study in Kangding County, Southwestern China. Water 2018, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Zhang, Q. Groundwater Chemical Characteristics and Controlling Factors in a Region of Northern China with Intensive Human Activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wu, J.; Qian, H. Hydrochemical appraisal of groundwater quality for drinking and irrigation purposes and the major influencing factors: A case study in and around Hua County, China. Arab. J. Geosci. 2016, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Rishi, M.S.; Herojeet, R.; Kaur, L.; Sharma, K. Evaluation of groundwater quality and human health risks from fluoride and nitrate in semi-arid region of northern India. Environ. Geochem. Health 2020, 42, 1833–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Xiao, C.; Liang, X.; Wei, H. Response of groundwater chemical characteristics to land use types and health risk assessment of nitrate in semi-arid areas: A case study of Shuangliao City, Northeast China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 236, 113473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Peng, Y.; Li, C.; Gao, Z.; Chen, S. Characterization of the hydrochemistry of water resources of the Weibei Plain, Northern China, as well as an assessment of the risk of high groundwater nitrate levels to human health—ScienceDirect. Environ. Pollut. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 268, 115947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Han, C.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Luo, Z.; Liu, J. Assessment of the water quality of groundwater in Bohai Rim and the controlling factors-a case study of northern Shandong Peninsula, north China. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 285, 117482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wu, J.; Qian, H. Assessment of groundwater quality for irrigation purposes and identification of hydrogeochemical evolution mechanisms in Pengyang County, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013, 69, 2211–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, P.; Qu, S.; Liao, F.; Wang, G. Hydrochemical Characteristics of Groundwater and Dominant Water-Rock Interactions in the Delingha Area, Qaidam Basin, Northwest China. Int. J. Appl. Mech. 2020, 12, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, X.; You, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Sun, P.; Fu, J.; Yu, Y.; Mao, K. Hydrochemical Formation Mechanisms and Source Apportionment in Multi-Aquifer Systems of Coastal Cities: A Case Study of Qingdao City, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekklesia, E.; Shanahan, P.; Chua, L.H.C.; Eikaas, H.S. Associations of chemical tracers and faecal indicator bacteria in a tropical urban catchment. Water Res. 2015, 75, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Xie, M.; Zhang, L.; Huang, J.; Xu, Z.; Li, H.; Jiang, R.; Wang, R.; Zeng, X. Identification of sewage markers to indicate sources of contamination: Low cost options for misconnected non-stormwater source tracking in stormwater systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisi, B.; Raco, B.; Dotsika, E. Groundwater Contamination Studies by Environmental Isotopes: A review. In Threats to the Quality of Groundwater Resources; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- GB 5749–2002; National Standard for Drinking Water Quality. Standardization Administration of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2002.

- Bouchard, D.C.; Williams, M.K.; Surampalli, R.Y. Nitrate Contamination of Groundwater: Sources and Potential Health Effects. J.-Am. Water Work. Assoc. 1992, 84, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Yu, X.; Chen, K.; Tan, H.; Yuan, J. Spatiotemporal characteristics and driving factors of chemical oxygen demand emissions in China’s wastewater: An analysis based on spatial autocorrelation and geodetector. Ecol. Indicators. 2024, 166, 112308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegegne, A.M.; Lohani, T.K.; Eshete, A.A. Potential risk assessment due to groundwater quality deterioration and quantifying the major influencing factors using geographical detectors in the Gunabay watershed of Ethiopia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, S.; Li, P.; Fida, M. Groundwater Nitrate Pollution Due to Excessive Use of N-Fertilizers in Rural Areas of Bangladesh: Pollution Status, Health Risk, Source Contribution, and Future Impacts. Expo. Health 2023, 16, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, F.; Chen, S.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xie, H.; Meng, Q.; Xia, Y. Hydrogeochemical and isotopic insights into groundwater evolution in the agricultural area of the Luanhe Plain. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, Q.; Mojtaba, A.; Mansoureh, F.; Abolfazl, B.; Mohadeseh, A.; Ahmad, Z. Health risk assessment of nitrate exposure in groundwater of rural areas of Gonabad and Bajestan, Iran. Environ. Earth Ences 2018, 77, 551. [Google Scholar]

- Ahada, C.P.S.; Surindra, S. Groundwater nitrate contamination and associated human health risk assessment in southern districts of Punjab, India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 25336–25347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Unit | Infants | Children | Adult Males | Adult Females |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRf of nitrate (DRf) | mg/(kg·d) | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Daily water intake (IR) | L/d | 0.64 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Gastrointestinal absorption (ABS) | - | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Exposure frequency (EF) | d/a | 365 | 365 | 365 | 365 |

| Exposure duration (ED) | a | 1 | 12 | 30 | 30 |

| Body weight (BW) | kg | 10 | 30 | 69.55 | 60.4 |

| Average contact time (AT) | d | 365 × ED | 365 × ED | 365 × ED | 365 × ED |

| Skin surface area (SA) | cm2 | 5000 | 12,000 | 16,000 | 15,000 |

| Skin permeability (KP) | cm/h | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Bathing frequency (EV) | Times/d | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Conversion factor (CF) | L/cm3 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Indicator | Unit | Maximum | Minimum | Average | Standard Deviation | Coefficient of Variation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | - | 8.4 | 7.0 | 7.6 | 0.31 | 4.1 |

| TDS | mg/L | 900 | 90.0 | 371 | 187 | 50.3 |

| Na+ | mg/L | 105 | 5.68 | 22.6 | 19.6 | 86.6 |

| K+ | mg/L | 13.7 | 0.60 | 2.33 | 2.10 | 90.0 |

| Ca2+ | mg/L | 187 | 18.2 | 74.5 | 39.5 | 53.0 |

| Mg2+ | mg/L | 39.9 | 4.24 | 14.6 | 7.45 | 51.1 |

| Cl− | mg/L | 147 | 8.15 | 39.5 | 33.4 | 84.5 |

| SO42− | mg/L | 236 | 12.1 | 79.4 | 51.4 | 64.8 |

| HCO3− | mg/L | 277 | 36.3 | 164 | 55.3 | 33.8 |

| CO32− | mg/L | 20.8 | 0.00 | 1.15 | 3.52 | 307 |

| NO3− | mg/L | 259 | 0.94 | 47.8 | 57.6 | 121 |

| NH3-N | mg/L | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 115 |

| NO2− | mg/L | 0.90 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 279 |

| Indicator | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | −0.269 | 0.631 | 0.443 | −0.082 |

| TDS | 0.962 | −0.004 | 0.066 | 0.193 |

| Na+ | 0.618 | 0.54 | −0.400 | 0.037 |

| K+ | 0.319 | 0.654 | −0.194 | 0.284 |

| Ca2+ | 0.911 | −0.349 | 0.051 | 0.020 |

| Mg2+ | 0.807 | 0.110 | 0.353 | −0.200 |

| Cl− | 0.870 | −0.117 | −0.098 | −0.047 |

| SO42− | 0.676 | 0.495 | −0.454 | 0.08 |

| HCO3− | 0.619 | −0.201 | 0.374 | 0.019 |

| CO32− | 0.083 | 0.658 | 0.544 | −0.255 |

| NH3-N | −0.274 | −0.259 | −0.057 | 0.463 |

| NO2− | −0.019 | 0.123 | 0.484 | 0.753 |

| NO3− | 0.725 | −0.511 | 0.196 | −0.057 |

| Eigenvalues | 5.166 | 2.327 | 1.454 | 1.024 |

| Variance Contribution Rate (%) | 39.737 | 17.901 | 11.185 | 7.879 |

| Cumulative Contribution Rate (%) | 39.737 | 57.637 | 68.823 | 76.702 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Song, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, W.; Shi, J.; Hu, S.; Wang, J.; Niu, X. Hydrochemical Characteristics and Nitrate Health Risk Assessment in a Shallow Aquifer: Insights from a Typical Low-Mountainous Region. Water 2025, 17, 3516. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243516

Li X, Song J, Liu J, Liu W, Shi J, Hu S, Wang J, Niu X. Hydrochemical Characteristics and Nitrate Health Risk Assessment in a Shallow Aquifer: Insights from a Typical Low-Mountainous Region. Water. 2025; 17(24):3516. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243516

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xia, Jiaxin Song, Junjian Liu, Wenda Liu, Jingtao Shi, Suduan Hu, Jiangyulong Wang, and Xueyao Niu. 2025. "Hydrochemical Characteristics and Nitrate Health Risk Assessment in a Shallow Aquifer: Insights from a Typical Low-Mountainous Region" Water 17, no. 24: 3516. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243516

APA StyleLi, X., Song, J., Liu, J., Liu, W., Shi, J., Hu, S., Wang, J., & Niu, X. (2025). Hydrochemical Characteristics and Nitrate Health Risk Assessment in a Shallow Aquifer: Insights from a Typical Low-Mountainous Region. Water, 17(24), 3516. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243516