2.3.1. Fuzzy Variable Set Theory and the Relative Membership Degree

Fuzzy variable set theory, initially introduced by Chen as a method for uncertainty analysis, has been subsequently utilized in water resource management studies, as demonstrated by Chunqing, Duan et al. [

28]. According to

Section 2.1, it can be seen that each water quality grade indicator has an accurate threshold. However, when the monitoring value of the indicator falls within the threshold range of the

k-th water quality grade, it cannot be guaranteed that the water quality definitely belongs to that water quality grade or other water quality grades [

29]. In other words, when the monitoring value of the indicator falls within the threshold range of the

k-th water quality grade, the water quality grade belonging to the

k-th grade is a fuzzy concept [

30,

31].

The monitoring value of the

i-th indicator at the

j-th station is denoted as

xij. The possibility that a water sample belongs to the

k-th water quality grade is represented by the relative membership degree

μ(

xij)

k, which ranges from 0 to 1 [

32]. A higher value of

μ(

xij)

k indicates a greater likelihood that the water quality grade is

k. Specifically, when

μ(

xij)

k = 1, it indicates definite membership to the

k-th grade, while

μ(

xij)

k = 0, indicates definite non-membership.

As established in

Section 2.2, the information content of water quality is derived from the grade discrimination of indicators rather than their numerical values. To quantify this grade discrimination, the distribution of an indicator across the various quality grades must be determined [

32].

For a specific monitoring value

xij, its membership to the

k-th water quality grade is a fuzzy concept; thus, the grade distribution cannot be directly inferred from

xij alone. However, the relative membership degree

μ(

xij)

k provides a precise quantitative measure of this distribution. The grade discrimination—and consequently, the information content of water quality—can be quantified by calculating the dispersion (e.g., entropy or standard deviation) of the membership vector

μ(

xij)

k, across all grades

k [

33]. In other words, the grade discrimination of monitoring values can be indirectly quantified by calculating the information entropy of the relative membership degrees—that is, the fuzzy entropy.

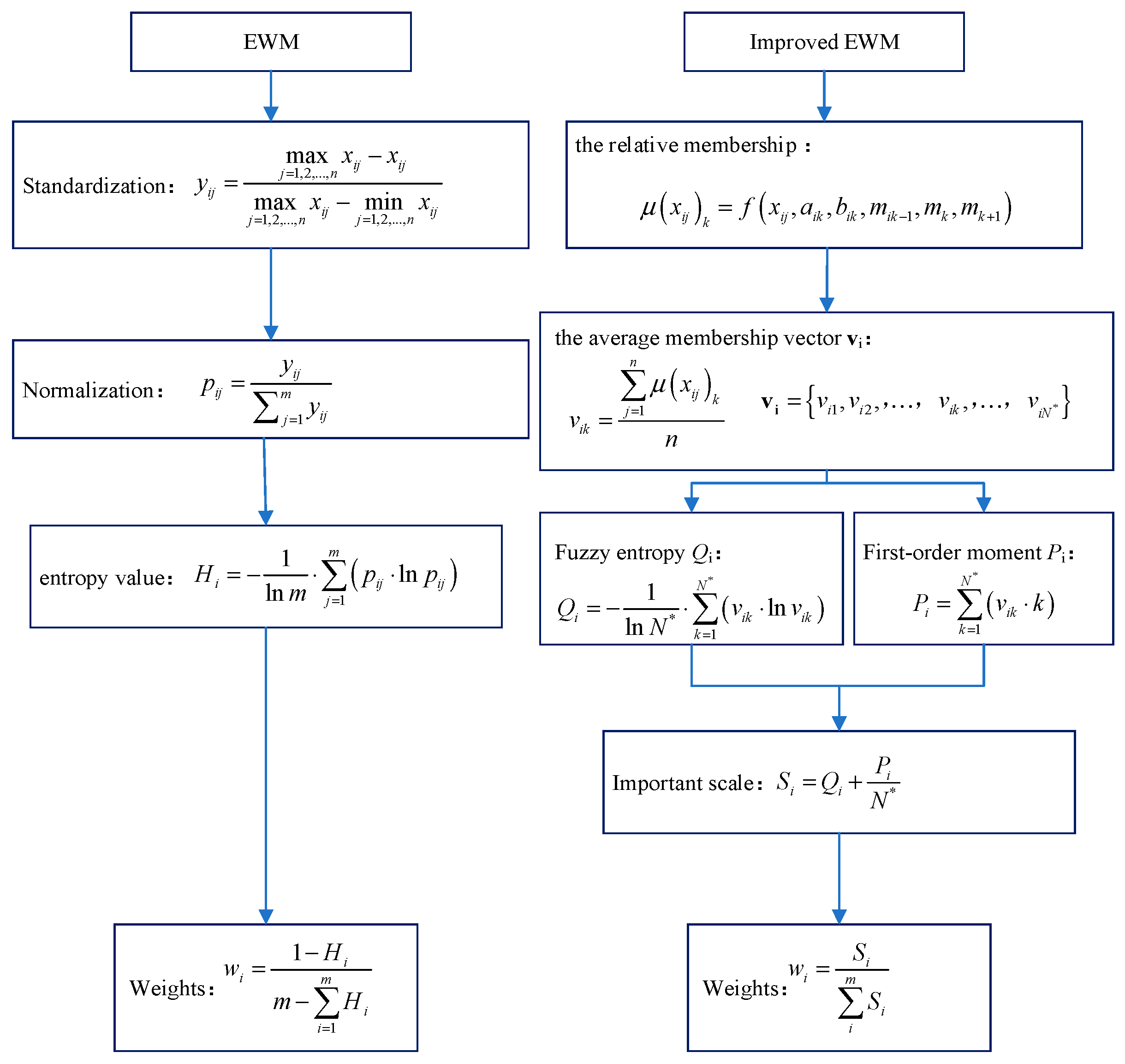

2.3.2. Improved Entropy Weight Model (I-EWM)

The Improved Entropy Weight Method (I-EWM) attempts to calculate the information content of water quality grade distribution using fuzzy entropy. The basic approach of this method is to first compute the relative membership degree matrix and the fuzzy entropy of indicator monitoring values, and then determine the weights based on the informational significance of each indicator’s relative membership degrees. The greater the dispersion of an indicator’s monitoring values in terms of relative membership degrees, the higher the information content of that indicator, and thus the larger the weight assigned to it; conversely, the smaller the dispersion, the lower the weight.

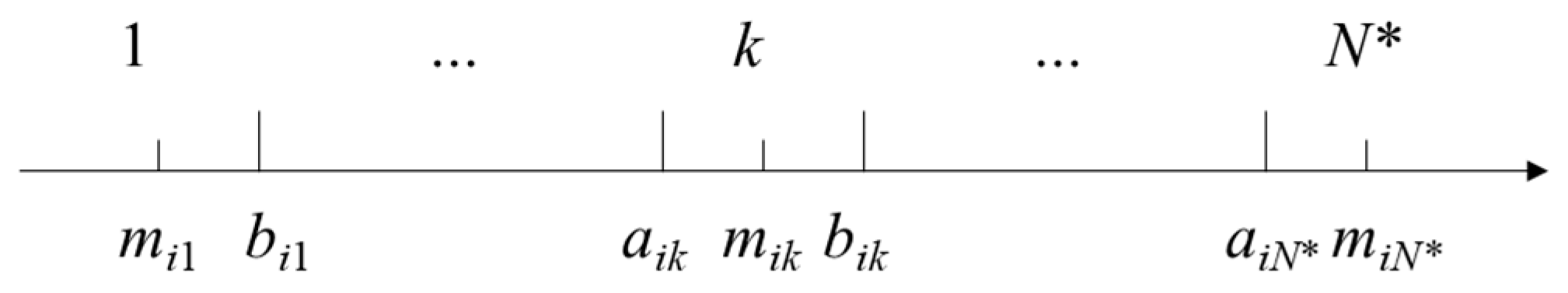

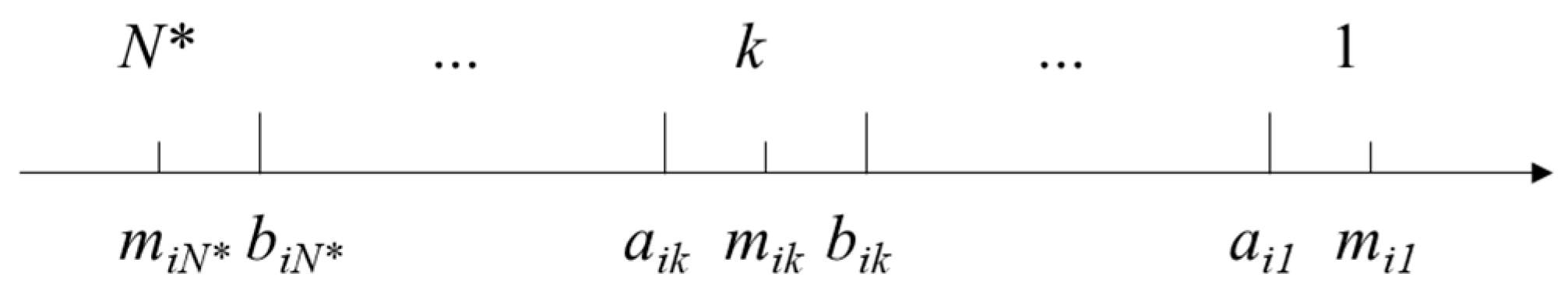

Assuming there are

m pollutant indicators and

n monitoring stations, the thresholds for the

i-th indicator are defined in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, where the

N*-th grade represents the highest water quality level. For the

k-th grade:

aik denotes the lower limit of the threshold,

bik denotes the upper limit,

mik denotes the median value,

and general

β = 1 [

34,

35].

The weighting procedure of the Improved Entropy Membership Weight (I-EMW) method comprises the following steps.

Step 1: Calculate the relative membership degree μ(xij)k:

The membership degree vector serves as the primary carrier of information. Therefore, a scientific analysis of this vector is a prerequisite for conducting grade evaluation and identifying limiting factors. Common principles for such evaluation include the maximum membership degree principle, the proximity principle, and the weighted average principle [

36]. Building upon the weighted average principle, this paper calculates the relative membership degree and the average membership degree of the indicators.

For a “smaller-is-better” indicator, μ(xij)k is calculated as follows:

For a “larger-is-better” indicator, μ(xij)k is calculated as follows:

Step 2: Calculate the average membership vector of indicators.

The relative membership degrees for all grades constitute the relative membership vector of the monitoring value

xij, denoted as

uij = {

μ(x

ij)

1,

μ(x

ij)

2, …,

μ(x

ij)

k, …,

μ(x

ij)

N*}. It is easy to find that each element of the relative membership vector

uij satisfies the following conditions:

To comprehensively represent the environmental characteristics of the

i-th indicator across all monitoring stations, we define its average membership vector

vi = {

vi1,

vi2, …,

vik, …,

viN*}. This vector is obtained by averaging the membership vectors

uij from all

n stations:

where

vik represents the average extent to which the

i-th indicator belongs to the

k-th grade across the entire study area.

Step 3: Calculate the fuzzy entropy and the first-order moments.

The basic calculation formula for fuzzy entropy is derived from Shannon’s information entropy theory. After more than a century of development, the concept of entropy has expanded beyond its narrow physical origins, with its definition, formulas, and laws undergoing varying degrees of transformation—particularly in the expressions used to calculate entropy. In this paper, the fuzzy entropy formula is computed by treating the average membership vector as a discrete variable [

37].

The fuzzy entropy

Qi for the

i-th indicator is introduced to quantify the uncertainty (or information content) inherent in its grade discrimination. It is calculated based on the average membership vector

vi as follows:

The fuzzy entropy Qi reflects the grade discrimination level of the i-th indicator, with a value range of [0, 1]. A higher Qi value indicates a greater grade discrimination level and, consequently, a greater importance of the indicator in the evaluation system. Specifically:

When Qi = 1, the grade discrimination and information content of the indicator are maximized, signifying the highest importance.

When Qi = 0, the indicator possesses no grade discrimination or information content, rendering it unimportant.

However, in water quality assessment, the practical significance of heavily polluted indicators often outweighs that of clean indicators. To account for this, I-EMW incorporates the pollution degree into the weighting process. This is quantified by the first-order moment

Pi, which is defined as the expected (average) water quality grade for the

i-th indicator across all monitoring stations. It is calculated as follows:

where

k is the grade number (e.g., 1, 2, …,

N*), and

vik is the average membership degree of the

i-th indicator to the

k-th grade from Equation (16). A higher

Pi value indicates a worse overall pollution state for the indicator.

As established,

Pi reflects the pollution degree, while

Qi quantifies the grade discrimination level of the

i-th indicator. The I-EMW integrates these two dimensions to assign weights, adhering to the following principles [

14]:

For indicators with an identical pollution degree (Pi), a higher grade discrimination level (Qi) confers greater importance and thus a higher weight.

For indicators with an identical grade discrimination level (Qi), a higher pollution degree (Pi) confers greater importance and thus a higher weight.

Step 4: Calculate the importance scale.

To integrate the pollution degree

Pi and the grade discrimination level

Qi into a composite measure, the importance scale

Si for the

i-th indicator is defined by their weighted sum:

This additive form ensures that both dimensions contribute independently and additively to the overall importance, preventing the scenario where a low value in one dimension nullifies the contribution of the other.

The value range of Si is [1/N*, 2], which is derived from the lower and upper bounds of its components (Qi ∈ [1/N*, 2], Pi/N* ∈ [1/N*, 1]). This signifies:

When Si = 2, both the pollution degree and the grade discrimination level are maximized (Qi = 1, Pi = N*), signifying the greatest importance.

When Si = 1/N*, both dimensions are minimized (Qi = 0, Pi = 1), signifying the least importance.

Step 5: Calculate the final weights.

The final weight

wi for the

i-th indicator is obtained by normalizing the importance scale

Si across all m indicators to ensure their sum equals unity, fulfilling the fundamental constraint of weight assignment: