Discussion on the Dominant Factors Affecting the Main-Channel Morphological Evolution in the Wandering Reach of the Yellow River

Abstract

1. Introduction

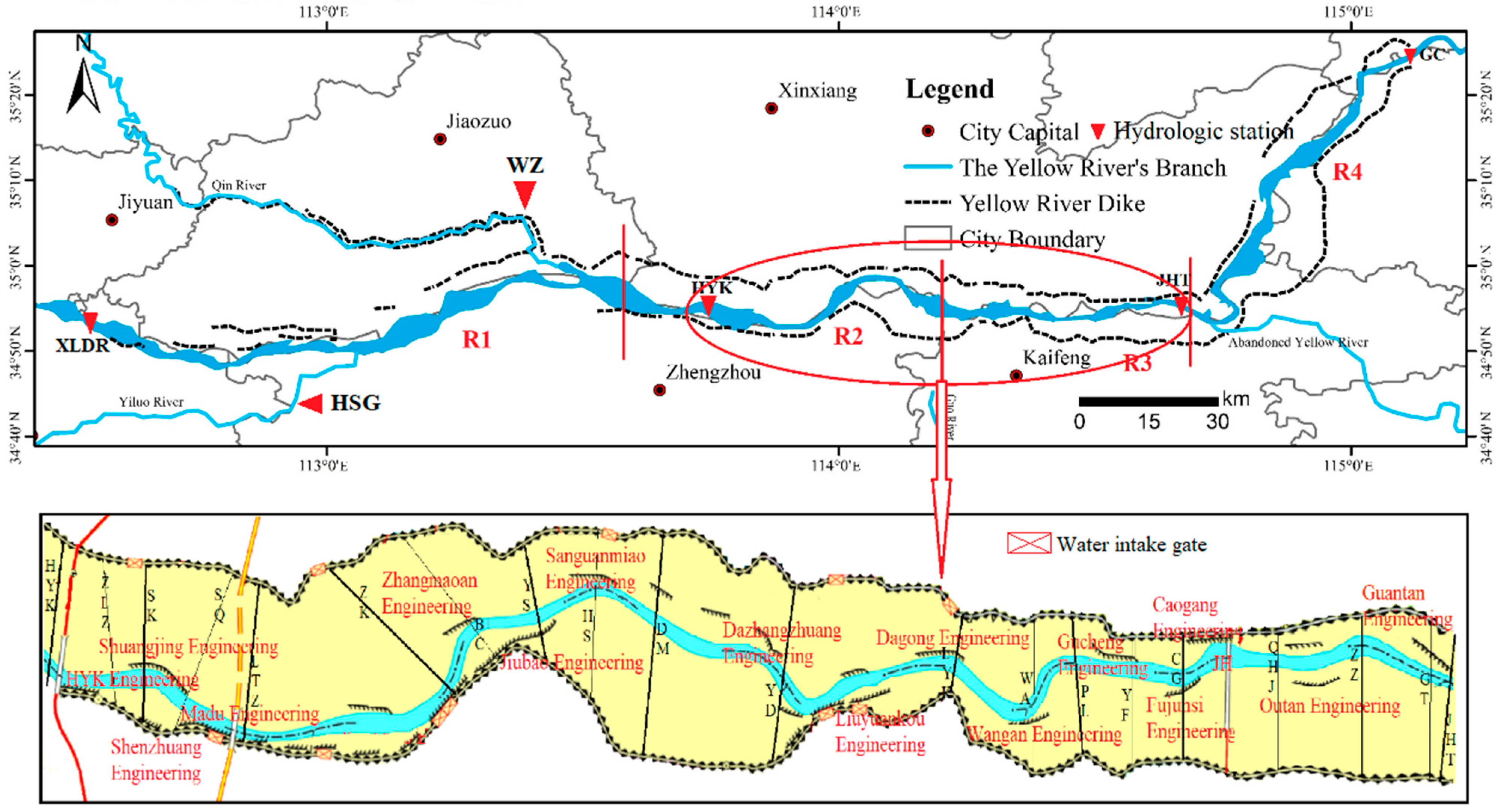

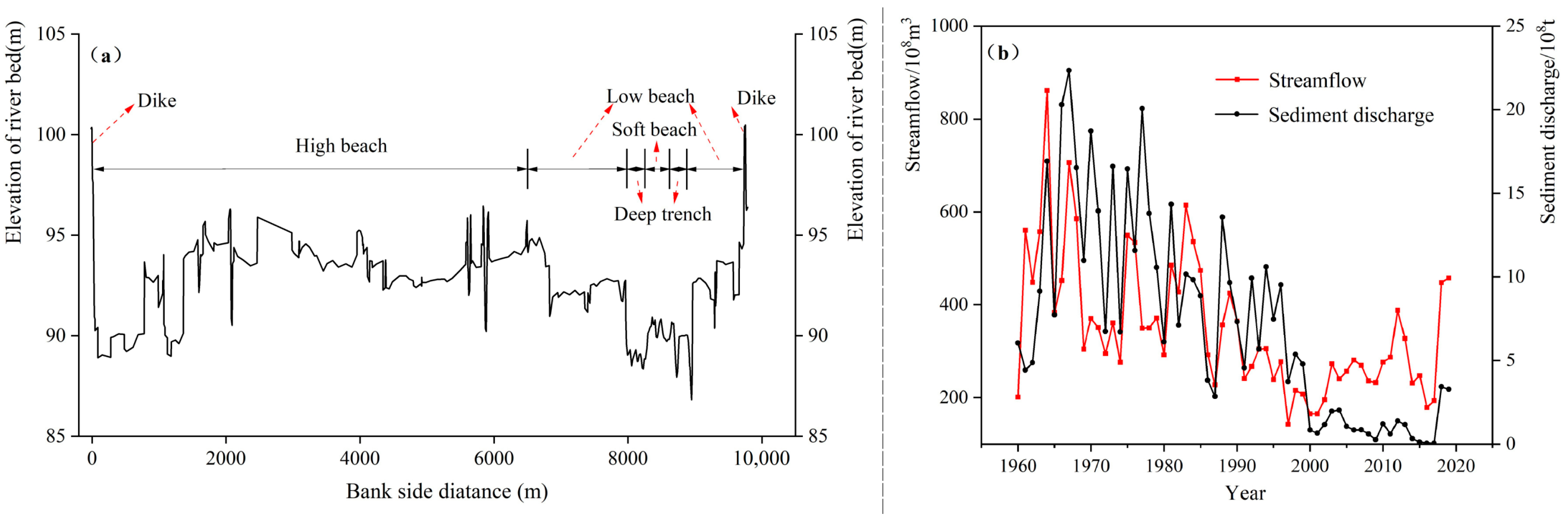

2. Overview of the Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Approach

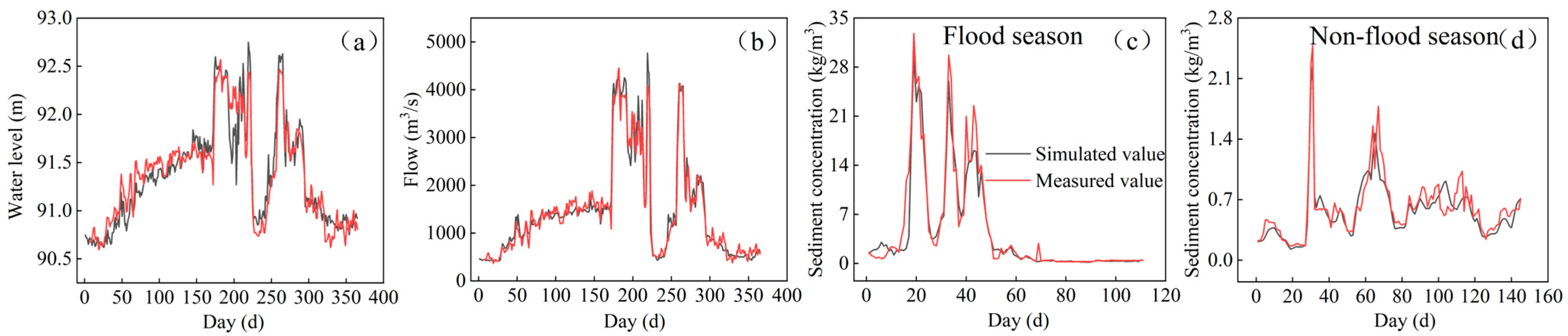

- Based on the measured hydrological, sedimentary, and topographical data, a two-dimensional water–sediment dynamic model was constructed to simulate the changes in water-sediment in the study area over time and space and to obtain the hydrological and sedimentary data of any area. Using the water balance principle, the sedimentation and erosion amounts of different river sections were calculated, and the evolution laws of the main channel of typical sections were analyzed.

- By comprehensively selecting the parameters of river channel morphology, such as the bankfull area (Abf) and the fluvial facies coefficient (ε), as well as the evolution parameters of the main channel, such as the migration distance and the bending coefficient (Ka), the evolution characteristics of the main-channel morphology in the wandering reach over a long time series were analyzed.

- Using the correlation analysis method, the relationships between the river morphology parameters and annual runoff volume, annual sediment discharge, flood season runoff volume, flood season sediment discharge, and sediment contribution coefficient were analyzed. Through multiple linear regression analysis, significant factors were further identified.

3.2. Method for Calculating Sedimentation and Erosion of Water Flow

3.3. Calculation of River Main-Channel Characteristic Parameters

3.4. Data Acquisition and Statistical Analysis

4. Results

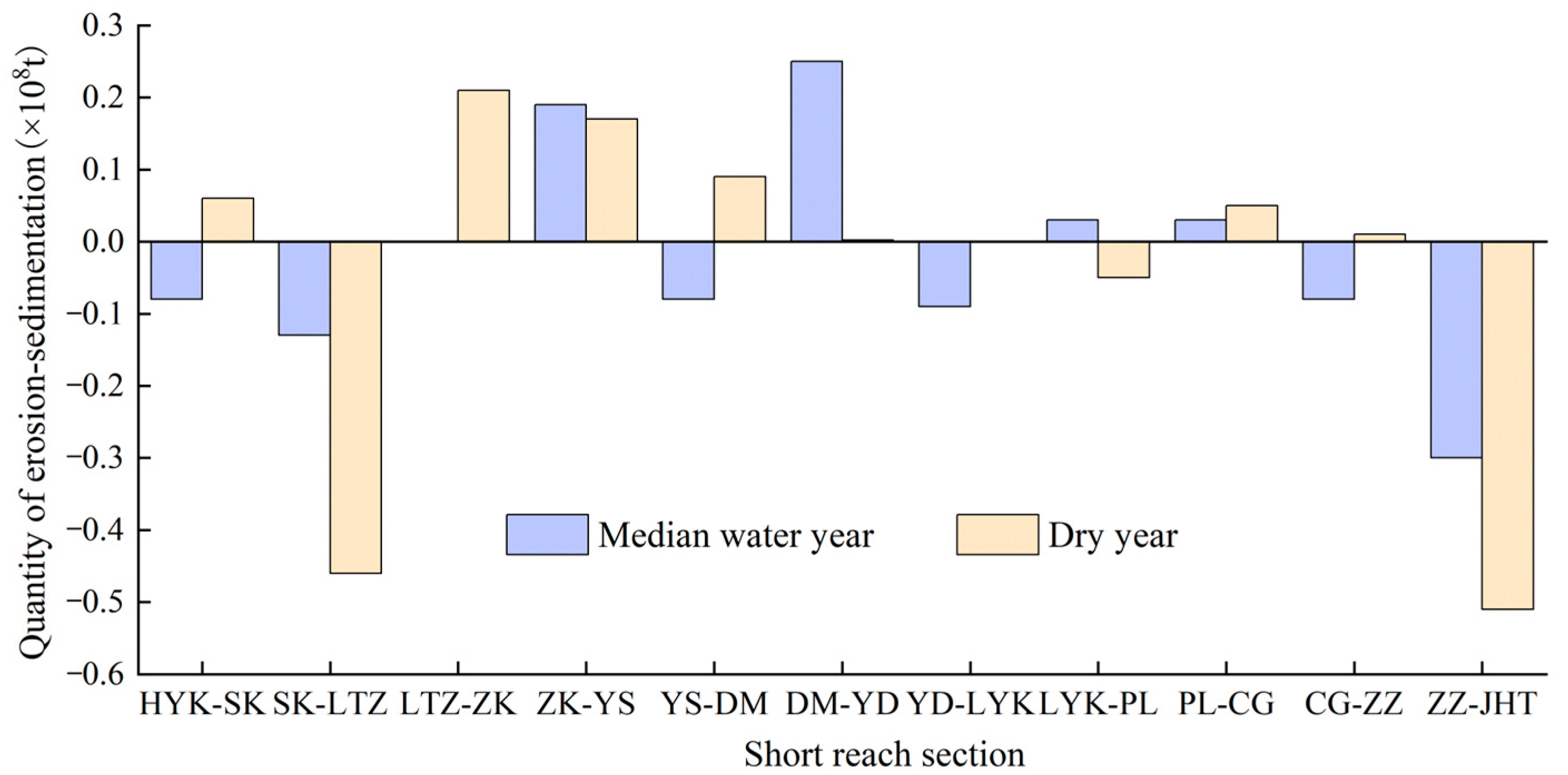

4.1. Analysis of Water-Sediment Erosion and Deposition Changes in the Study Area

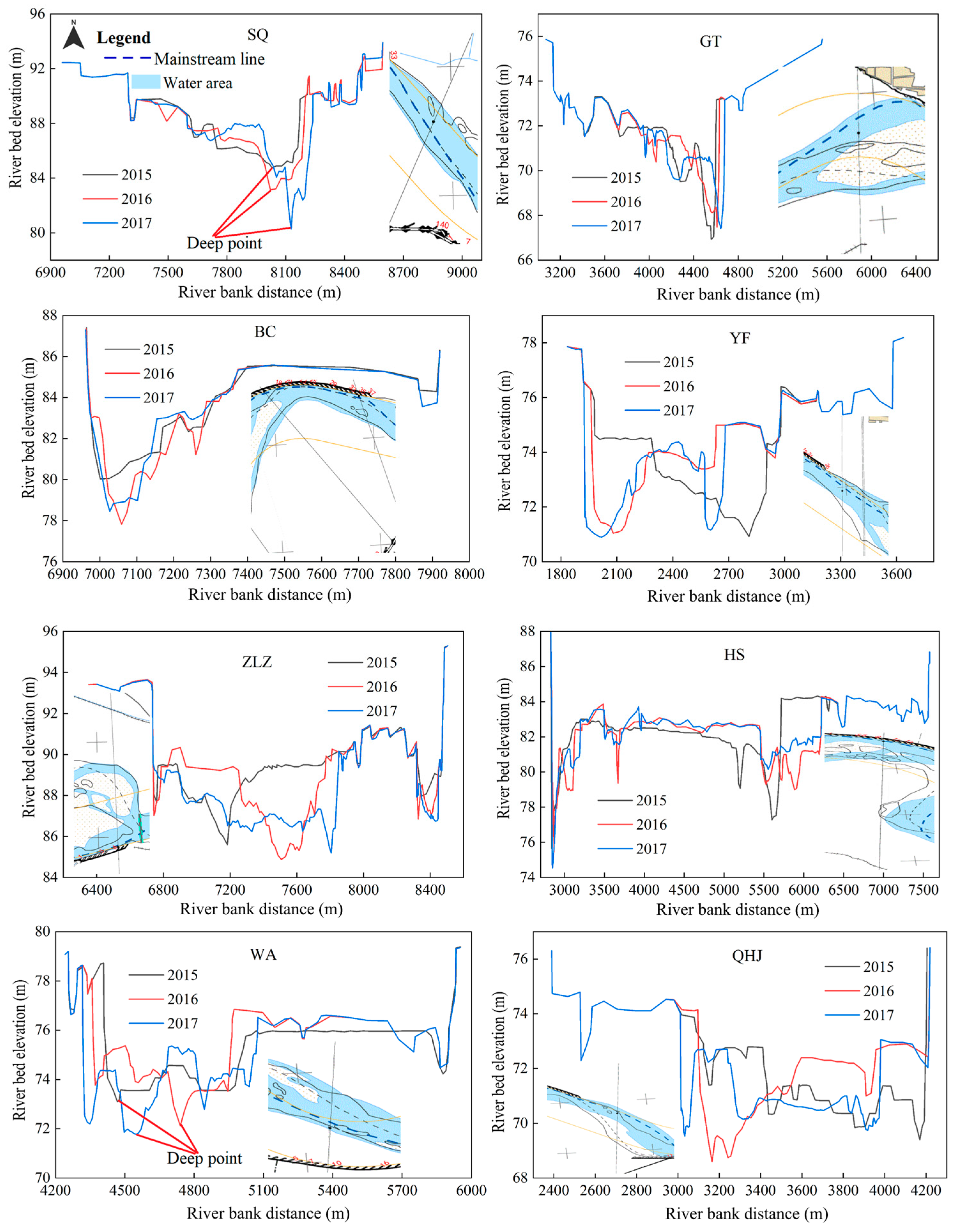

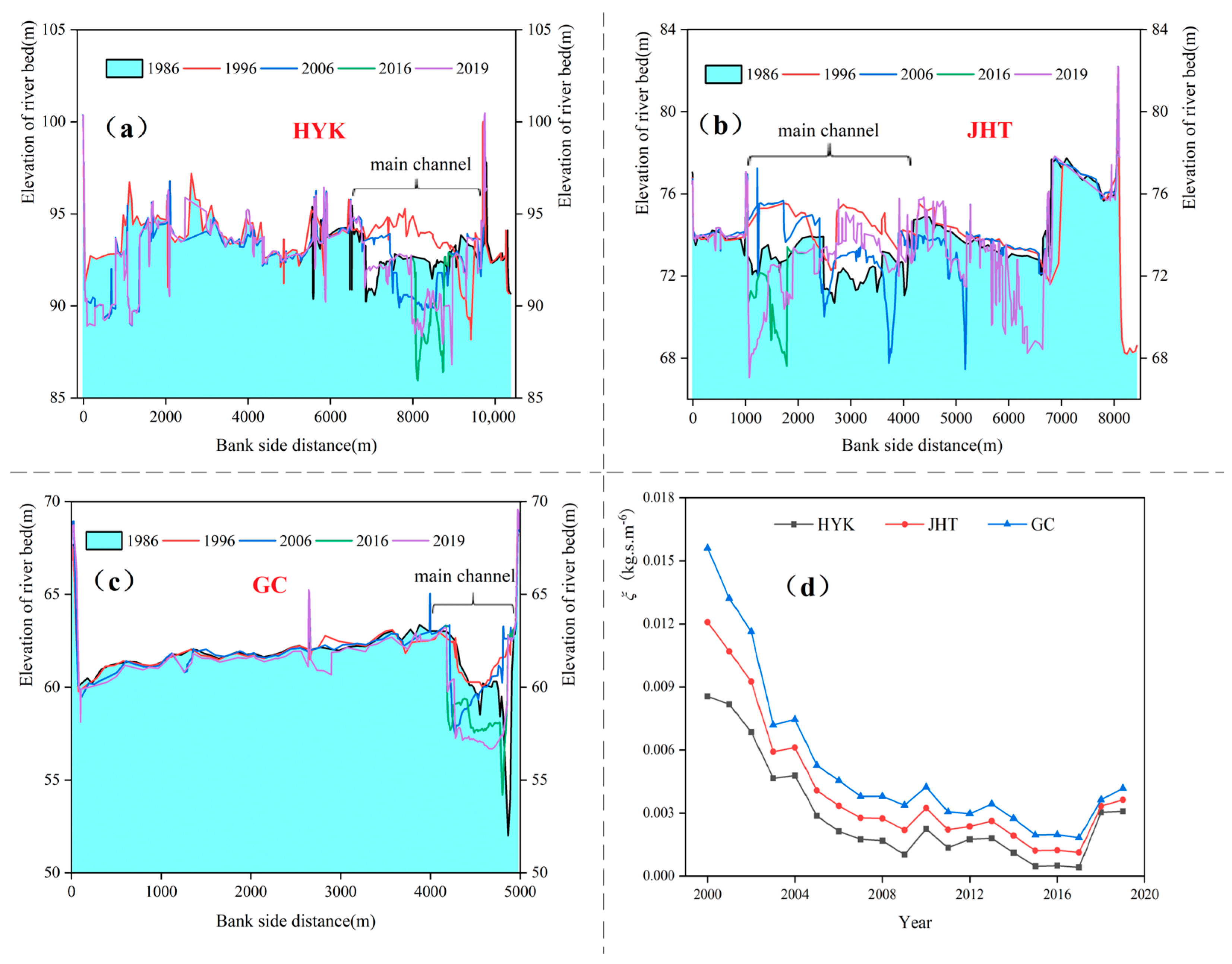

4.2. Analysis of the Evolution Law of the Main-Channel Morphology of Typical Cross-Sections in the Different Water Years

4.3. Analysis of Main-Channel Characteristic Parameter Evolution Based on Long-Term Sequences

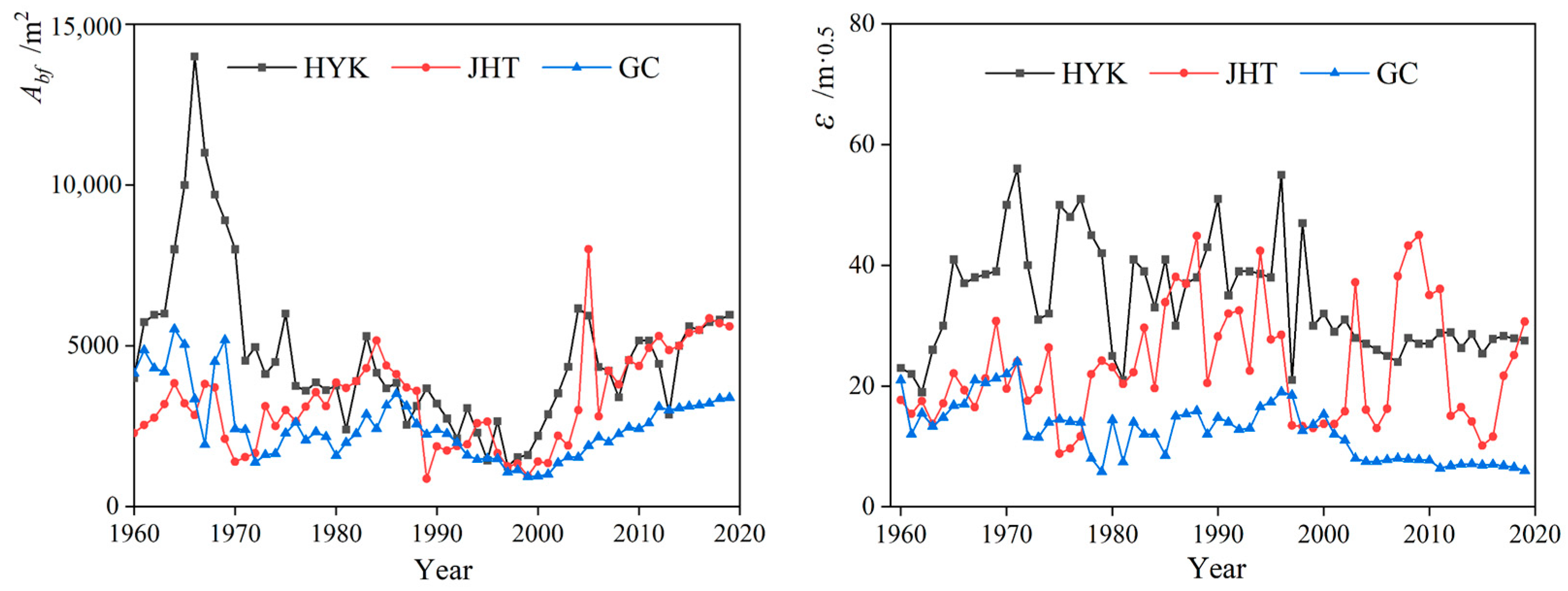

4.3.1. Evolution of Typical Cross-Section River Morphological Characteristic Parameters

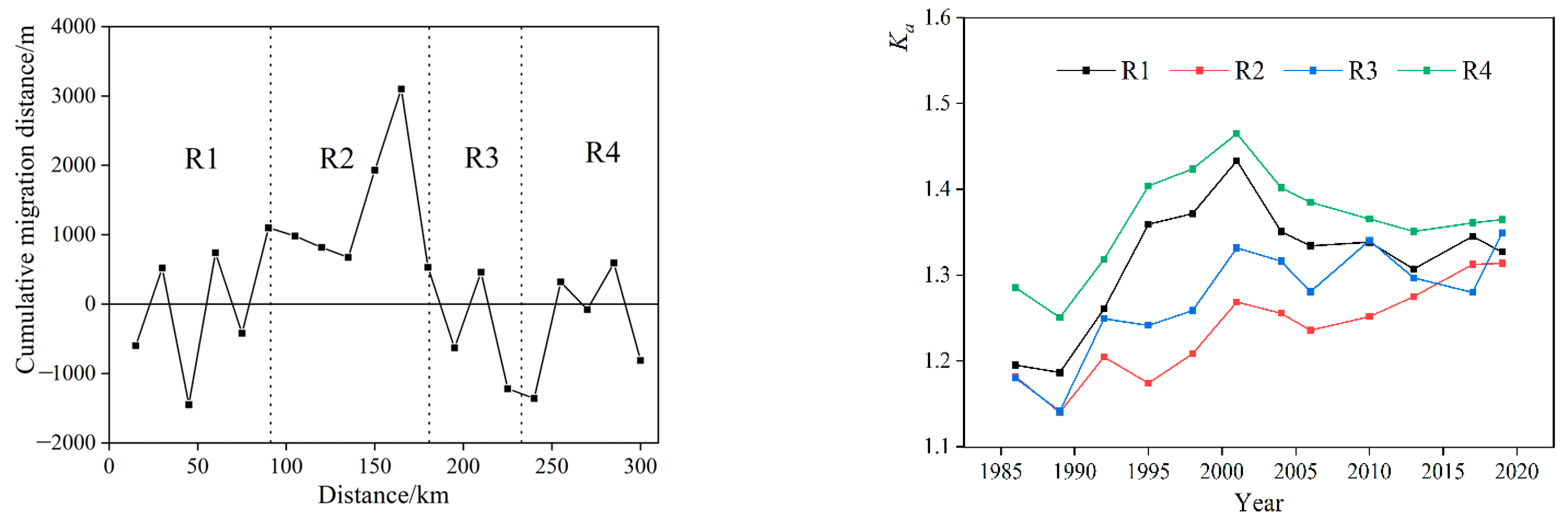

4.3.2. Variations in Main-Channel Evolution Characteristic Parameters in Different Reaches

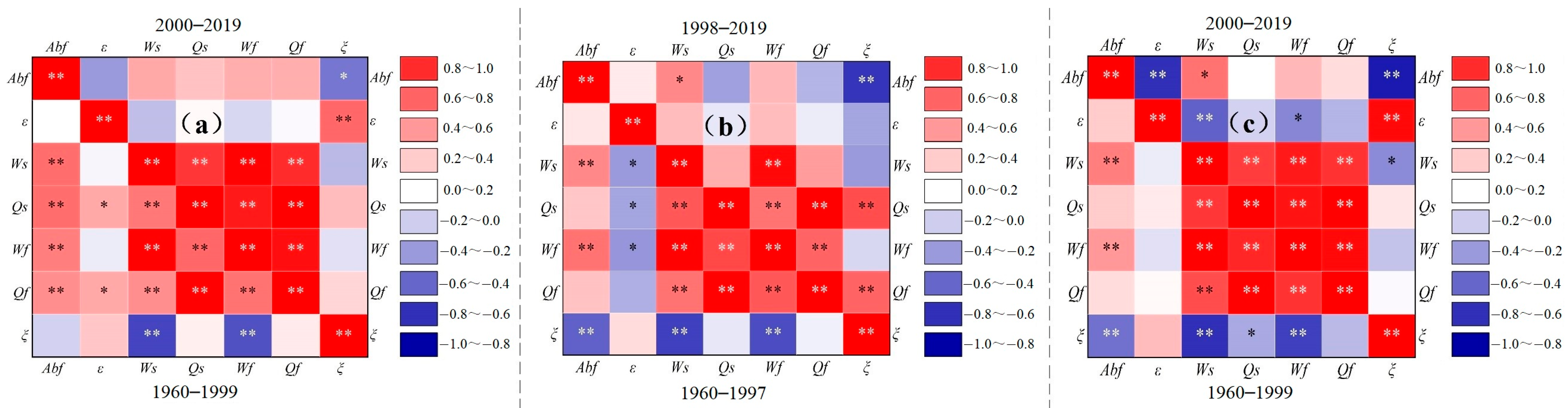

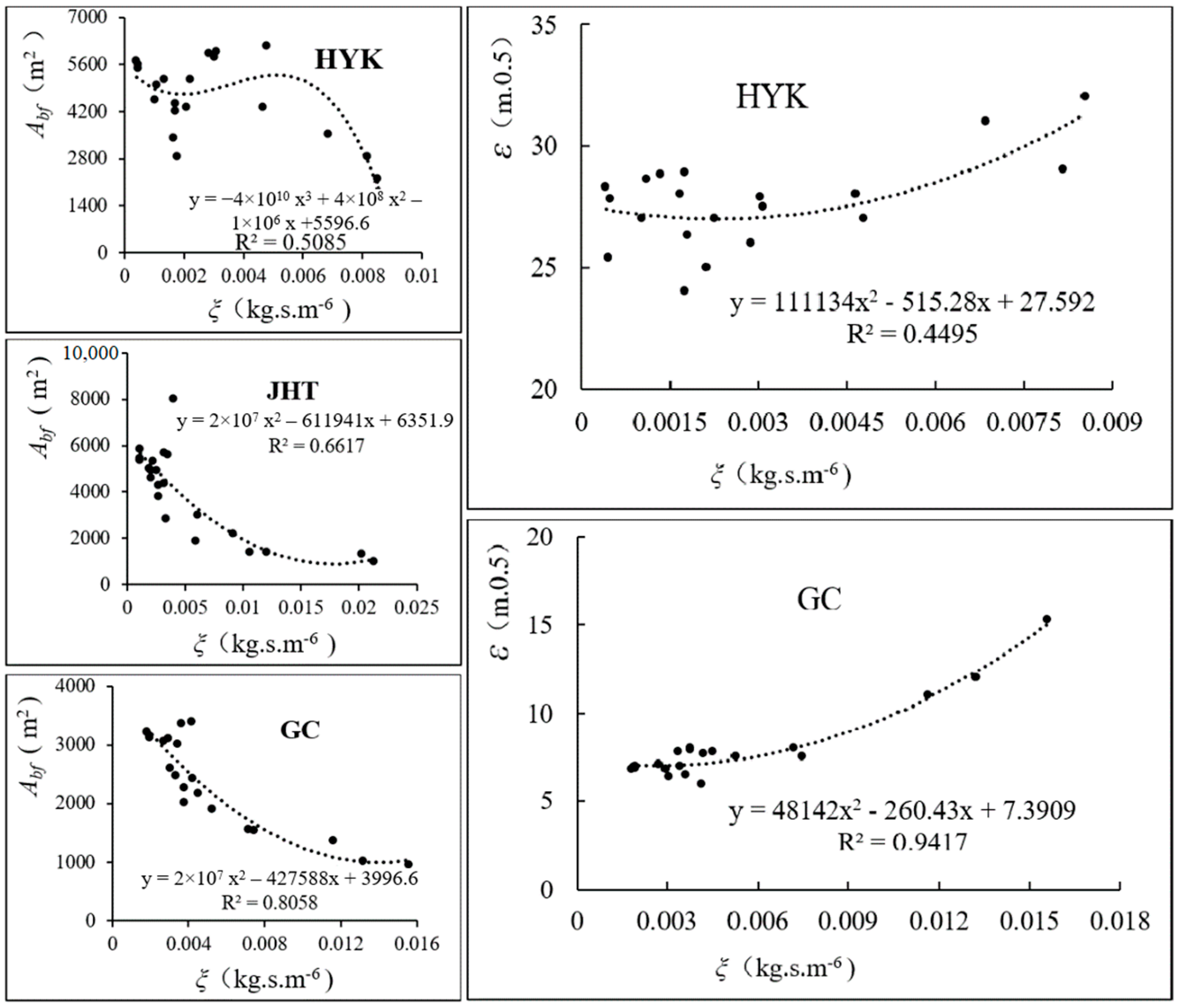

4.4. Identification of Influencing Factors and Construction of Response Relationships for Main-Channel Morphological Characteristic Parameters

5. Discussion

5.1. Influence of Water-Sediment Condition Changes on the Main-Channel Morphology Evolution

5.2. Influence of the Main Flow Direction and the Distribution of Control Engineering Structures on the Lateral Evolution of the Main-Channel Morphology

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- After the XLDR operation, the HYK–JHT reach experienced erosion in the median water and dry years. The erosion volume in the dry year was greater than that in the median water year. The length of erosion decreased from 51.91% in the median water year to 34.61% in the dry year, whereas the length of sedimentation increased from 38.44% in the median water year to 65.36% in the dry year. The erosion volume was large and concentrated in the dry year, whereas it was smaller but more dispersed in the median water year.

- (2)

- The river channel cross-sectional shape evolution is influenced by changes in water-sediment conditions and also constrained by the main river flow direction and regulating engineering. In the area without the constraint of regulating engineering, the main channel of the river undergoes longitudinal and transverse erosion in the direction of the main river flow, such as cross-sections like SQ, GT, and QHJ. In the area with the constraint of regulating engineering, the main channel of the river undergoes longitudinal erosion within the area constrained by regulating engineering, such as cross-sections like BC, HS, and ZLZ.

- (3)

- The construction of the XLDR has had a considerable impact on the evolution of the main-channel morphology parameters. The Abf and ε values of the typical cross-section showed different changing trends before and after the XLDR operation. Constrained by the dike and control projects, the R1, R3, and R4 reaches all shifted towards the south bank. The shift areas were increased by 2.5 km2, 11.1 km2, and 2.8 km2 compared to the shift in the north bank. The R2 reach moved towards the north bank, and the shift area was 22.4 km2 larger than that on the south bank.

- (4)

- After the XLDR was completed, the main factors influencing the changes in the main-channel parameters of the river underwent considerable changes. The main influencing factors of the main-channel parameters shifted from the joint effect of multiple factors to the prominent effect of a single factor. The three typical sections showed strong consistency. When the sediment input coefficient was between 0–0.005 kg.s.m−6, water-sediment had a positive effect on shaping and evolving the main-channel morphology of the river.

- (5)

- From a global perspective, the river channel morphology of the wandering reach of the Yellow River has reached a relatively stable state, but in some small areas, there are still phenomena of river channel oscillation and bank erosion. Future research on the river channel morphology evolution should be precisely aimed toward smaller areas and shorter distances. This places higher demands on the acquisition of data such as water level, flow rate, and sediment concentration. How to obtain precise data on water level, flow rate, and sediment concentration in any area of the wandering reach through existing means and measured data from key hydrological stations is a difficult point that must be overcome. The resolution of these issues and the resulting research will provide support for accelerating the governance of the Yellow River and strengthening its stability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, Z.; Zhao, D.; Syvitski, J.P.M.; Saito, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, M. Anthropogenic impacts on the decreasing sediment loads of nine major rivers in China, 1954–2015. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 139653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Yin, Q.; Jiang, S.; An, W.; Liao, J.; Liu, Y.; Fu, Y. Study on the Driving Mechanism of Ecohydrological Regime in the Wandering Section of the Lower Yellow River. Water 2024, 16, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dethier, E.N.; Renshaw, C.E.; Magilligan, F. Rapid changes to global river suspended sediment flux by humans. Science 2022, 376, 1447–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ni, J.; Chang, F.; Yue, Y.; Frolova, N.; Magritsky, D.; Borthwick, A.G.L.; Ciais, P.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, C.; et al. Global trends in water and sediment fluxes of the world’s large rivers. Sci. Bull. 2020, 65, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xia, J.; Zhou, M.; Li, J. Characteristics of main channel migration in the braided reach of the Lower Yellow River after the Xiaolangdi Reservoir operation. Adv. Water Sci. 2019, 30, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, F.D.; Simon, A.; Steffen, L.J. Reservoir effects on downstream river channel migration. Environ. Conserv. 2000, 27, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.R.; Xia, J.Q.; Deng, S.S. Fluvial processes of the Shishou reach in the Jingjiang Reach in recent fifty years. J. Sediment Res. 2017, 42, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Mao, J.X.; Chen, X.J. Study on scour and armor in the downstream of Three Gorges Reservoir. J. Sediment Res. 2017, 42, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.R.; Xia, J.Q.; Zhou, M.R.; Wang, Y.Z. Evolution process of different abnormal river bends in the braided reach of the Lower Yellow River. J. Lake Sci. 2020, 32, 1837–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Zhong, D.Y.; Zhang, H.W.; Wang, Y.J.; Huang, H. Riverbed adjustment characteristics in braided reaches of lower Yellow River under small and medium discharges. J. Hydroelectr. Eng. 2020, 39, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Yao, Y.; Borthwick, A.G.L.; Slater, L.J.; Syvitski, J.; Bi, N.; Yang, Z.; Wang, H. Mega-reservoir regulation: A comparative study on downstream responses of the Yangtze and Yellow rivers. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2023, 245, 104567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.H.; Wang, Y.J.; Jiang, E.H. Stability index for the planview morphology of alluvial rivers and a case study of the Lower Yellow River. Geomorphology 2021, 389, 107853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xia, J.Q.; Ji, Q.F. Rapid and long-distance channel incision in the Lower Yellow River owing to upstream damming. Catena 2021, 196, 104943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.W.; Zheng, S.; Tan, G.M.; Shu, C. Effects of Three Gorges Dam operation on spatial distribution and evolution of channel thalweg in the Yichang-Chenglingji Reach of the Middle Yangtze River, China. J. Hydrol. 2019, 565, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.F.; Xia, J.Q.; Zhou, M.R.; Cheng, Y.F. Characteristics of section-scale lateral channel migration in the wandering reach of the Lower Yellow River. J. Sediment Res. 2023, 48, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.D.; Li, Z.W.; Boota, M.W.; Zohaib, M.; Liu, X.; Shi, C.; Xu, J. River pattern discriminant method based on Rough Set theory. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 45, 101285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittoria, C.; Kate, R.; Bjørn, K.; Ekeheien, C.; Høydal, Ø. Hydro-mechanical effects of several riparian vegetation combinations on the streambank stability—A benchmark case in Southeastern Norway. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.Q.; Wang, Y.Z.; Li, T.; Li, J. Method to Calculate Channel Migration and Its Application in the Braided Reach of the Lower Yellow River. Yellow River 2019, 41, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.L.; Feng, X.M.; Fu, B.J.; Yin, S.; He, C. Managing erosion and deposition to stabilize a silt-laden river. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 881, 163444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.Q. Dynamic Adjustments in Bankfull Width of a Braided Reach. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Water Manag. 2017, 172, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Wu, B.S.; Zhong, D.Y. Adjustment in the main-channel geometry of the Lower Yellow River before and after the operation of the Xiaolangdi Reservoir Reservoir from 1986 to 2015. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 468–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenna, A.; Surian, N.; Mao, L. Response of a gravel-bed river to dam closure: Insights from sediment transport processes and channel morphodynamics. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2020, 45, 756–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.P.; Wu, B.S.; Shen, Y.; Xue, Y.; Tan, C. Distribution pattern and characteristics of sedimentation in the Lower Yellow River. Shuili Xuebao 2024, 55, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.D.; Li, Z.W.; Boota, M.W.; Shi, C.; Xu, J. Identifying river changes by river pattern events: A case study of the Lower Yellow River, China. Geocarto Int. 2023, 38, 2168070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.D.; Chen, M.; Li, K.; Zhang, X.; Yang, J. Research progress on the failure mechanism of ecological slope protection under multi-factor coupling in the Lower Yellow River. Adv. Water Sci. 2024, 35, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.X.; Miao, C.Y.; Wu, J.W.; Borthwick, A.G.; Duan, Q.; Zhang, X. Environmental impact assessments of the Xiaolangdi Reservoir on the most hyperconcentrated laden river, Yellow River, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2017, 24, 4337–4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.X.; Wang, Y.C.; Hou, P.; Wan, H.W.; Zhang, W.G. Temporal and spatial variation characteristics of land surface water area in the Yellow River basin in recent 20 years. Shuili Xuebao 2020, 51, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Wu, B.S.; Zhong, D.Y. Simulation of the main-channel cross-section geometry of the Lower Yellow River in response to water and sediment changes. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2020, 75, 1494–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.L.; Li, Y.; Bai, Y.C.; Xu, H.Y.; Luo, Q.S. Sediment temporal-spatial distribution and geomorphological evolution in the Huayuankou-Gaocun reach in the lower Yellow River. Shuili Xuebao 2021, 52, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.M.; Fu, B.J.; Piao, S.L.; Wang, S.; Ciais, P.; Zeng, Z.; Lü, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, X.; et al. Revegetation in China’s Loess Plateau is approaching sustainable water resource limits. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wang, S.; Fu, B.J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Sediment transport under increasing anthropogenic stress: Regime shifts within the Yellow River, China. Ambio 2020, 49, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.H.; Jiao, J.Y.; Zhao, G.J.; Zhao, H.; He, Z.; Mu, X. Spatial-temporal variation and periodic change in streamflow and suspended sediment discharge along the mainstream of the Yellow River during 1950–2013. Catena 2016, 140, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.N.; Zhong, D.Y.; Zhang, Y.J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. Wide river or narrow river: Future river training strategy for Lower Yellow River under global change. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2018, 33, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fu, B.J.; Piao, S.L.; Lü, Y.H.; Ciais, P.; Feng, X.M.; Wang, Y.F. Reduced sediment transport in the Yellow River due to anthropogenic changes. Nat. Geosci. 2016, 9, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.H.; Dong, J.W.; Wang, M.H.; Xie, H.; Xia, N.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Mou, X.; Wen, J.; Bao, Y. Effect of water- sediment regulation of the Xiaolangdi Reservoir on the concentrations, characteristics, and fluxes of suspended sediment and organic carbon in the Yellow River. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 571, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.J.; Wu, X.; Bi, N.S.; Li, S.; Yuan, P.; Wang, A.; Syvitski, J.P.; Saito, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, S.; et al. Impacts of the dam-orientated water–sediment regulation scheme on the lower reaches and delta of the Yellow River (Huanghe): A review. Glob. Planet. Change 2017, 157, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.M.; Wang, W.H.; Xie, B.F.; Zhang, M. Fluvial processes of the downstream reaches of the reservoirs in the Lower Yellow River. J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 1321–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.Y.; Wang, W.Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Shang, H.; Zhang, F. Can the narrowing of the Lower Yellow River by regulation result in non-siltation and even channel scouring? J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cao, Z.X.; Borthwick, G.L. Quantifying multiple uncertainties in modelling shallow water-sediment flows: A stochastic Galerkin framework with Haar wavelet expansion and an operator-splitting approach. Appl. Math. Model. 2022. prepublish. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.Q.; Li, X.J.; Zhang, X.L.; Li, T. Recent variation in reach-scale bankfull discharge in the Lower Yellow River. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2014, 39, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.; Xia, J.Q.; Zhang, X.L.; Li, J. Recent variations of reach-scale bankfull channel geometry in the braided reach of lower Yellow River. J. Hydroelectr. Eng. 2014, 33, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Assessment Method of Channel Stability and Its Applications in Braided Reaches of the Yellow River. Ph.D. Thesis, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galappatti, G.; Vreugdenhil, C.B. A depth-integrated model for suspended sediment transport. J. Hydraul. Res. 1985, 23, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Xia, J.Q.; Zhou, M.R.; Cheng, Y.F. Characteristics and mechanism of wandering intensity adjustments in a wandering reach of the Lower Yellow River after the operation of the Xiaolangdi Reservoir. Act Geogr. Sin. 2024, 79, 1161–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.S.; Zhang, Y.F.; Xia, J.Q. Variation of bank-full area at Gaocun station in the Lower Yellow River. J. Sediment Res. 2008, 2, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, S.J.; Wang, Y.J. Variation of Morphological Parameters of Channel Cross-sections and Their Response to Water-sediment Processes in the Lower Yellow River. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2020, 40, 1563–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.J.; Chen, Q.Y. Theory of river pattern transformation and change of channel sinuosity ratio in Lower Yellow River. J. Sediment Res. 2013, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Wu, B.S.; Zhong, D.Y. Simulating Cross-Sectional Geometry of the Main Channel in Response to Changes in Water and Sediment in Lower Yellow River. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 2033–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.J.; Han, S.S.; Zhao, L.J.; Chang, A. Experimental Study on the Channel Morphological Adjustment Under Non-Equilibrium Sediment Transport Conditions. Yellow River 2024, 46, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.H.; Liu, G.; Jiang, E.H. Morphological effects of the operation of Xiaolangdi Reservoir on the Lower Yellow River in recent years. Shuili Xuebao 2024, 55, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.X.; Zhu, C.H.; Zhao, X.; Gao, X.; Luo, Q.S. Scouring and silting law of the Lower Yellow River and water and sediment regulation indicators after the regulation of Xiaolangdi Reservoir. Adv. Water Sci. 2024, 35, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Wang, P.; Shen, G.Q.; Wei, H.; Zhang, W.X. Impact of Xiaolangdi Reservoir operations on flow resistance in the Lower Yellow River. Adv. Water Sci. 2023, 34, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.C.; Liu, J.Z.; Bai, Y.C.; Xu, H.Y.; Zhang, J.L. Adjustment patterns and predictive modeling of main channel cross-sections in representative reaches of the Lower Yellow River. Adv. Water Sci. 2025, 36, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.Z.; Xu, X.Z.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, L. Study of effects of spur-dike group on river-regime control in lower reaches of the Yellow River. J. Dalian Univ. Technol. 2022, 62, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.L.; Huang, Z.; Bai, Y.; Song, X. Sediment deficit and morphological changes of alluvial floodplain in wandering reach of the Lower Yellow River after Xiaolangdi Reservoir operation. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic Parameter | Calculation Method | Parameter Significance | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abf | - | The section area where the water level of the section reaches the level of the flood plain. It has a corresponding relationship with the floodplain water level and the river width. | m2 |

| ε | Comprehensive index to characterize riverbed morphology, which is related to water depth and river width under bankfull water level. | m·0.5 | |

| Migration distance | ArcGIS 10.8 is used to convert each river reach in 1986 and 2019 into centroid points. The direction and distance between centroid points are the migration direction and distance of the main channel. The migration of centroid points to the left bank is positive, and the migration to the right bank is negative. | m | |

| Ka | The ratio of the actual length to the straight-line length. The dividing line is generally 1.3, and when it is greater than 1.3, the river is usually a wandering river. | - |

| Region | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swing to left bank | 15.4 | 28.6 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 59.9 |

| Swing to right bank | 17.9 | 6.2 | 19 | 10.2 | 53.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mi, Q.; Dou, M.; Li, G.; Li, L.; Li, G. Discussion on the Dominant Factors Affecting the Main-Channel Morphological Evolution in the Wandering Reach of the Yellow River. Water 2025, 17, 3509. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243509

Mi Q, Dou M, Li G, Li L, Li G. Discussion on the Dominant Factors Affecting the Main-Channel Morphological Evolution in the Wandering Reach of the Yellow River. Water. 2025; 17(24):3509. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243509

Chicago/Turabian StyleMi, Qingbin, Ming Dou, Guiqiu Li, Lina Li, and Guoqing Li. 2025. "Discussion on the Dominant Factors Affecting the Main-Channel Morphological Evolution in the Wandering Reach of the Yellow River" Water 17, no. 24: 3509. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243509

APA StyleMi, Q., Dou, M., Li, G., Li, L., & Li, G. (2025). Discussion on the Dominant Factors Affecting the Main-Channel Morphological Evolution in the Wandering Reach of the Yellow River. Water, 17(24), 3509. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243509