Impediments to, and Opportunities for, the Incorporation of Science into Policy and Practice into the Sustainable Management of Groundwater in Pakistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area

2.1. Population and Socioeconomic Profile

2.2. Land Use, Cropping Patterns, and Irrigation Infrastructure

2.3. Water Demand and Sources

2.4. Hydrological Realities of the Indus Basin: Science Signals of Depletion

2.5. Governance Framework and Institutional Dynamics: Policies on Paper vs. Practices on the Ground

3. Methodology

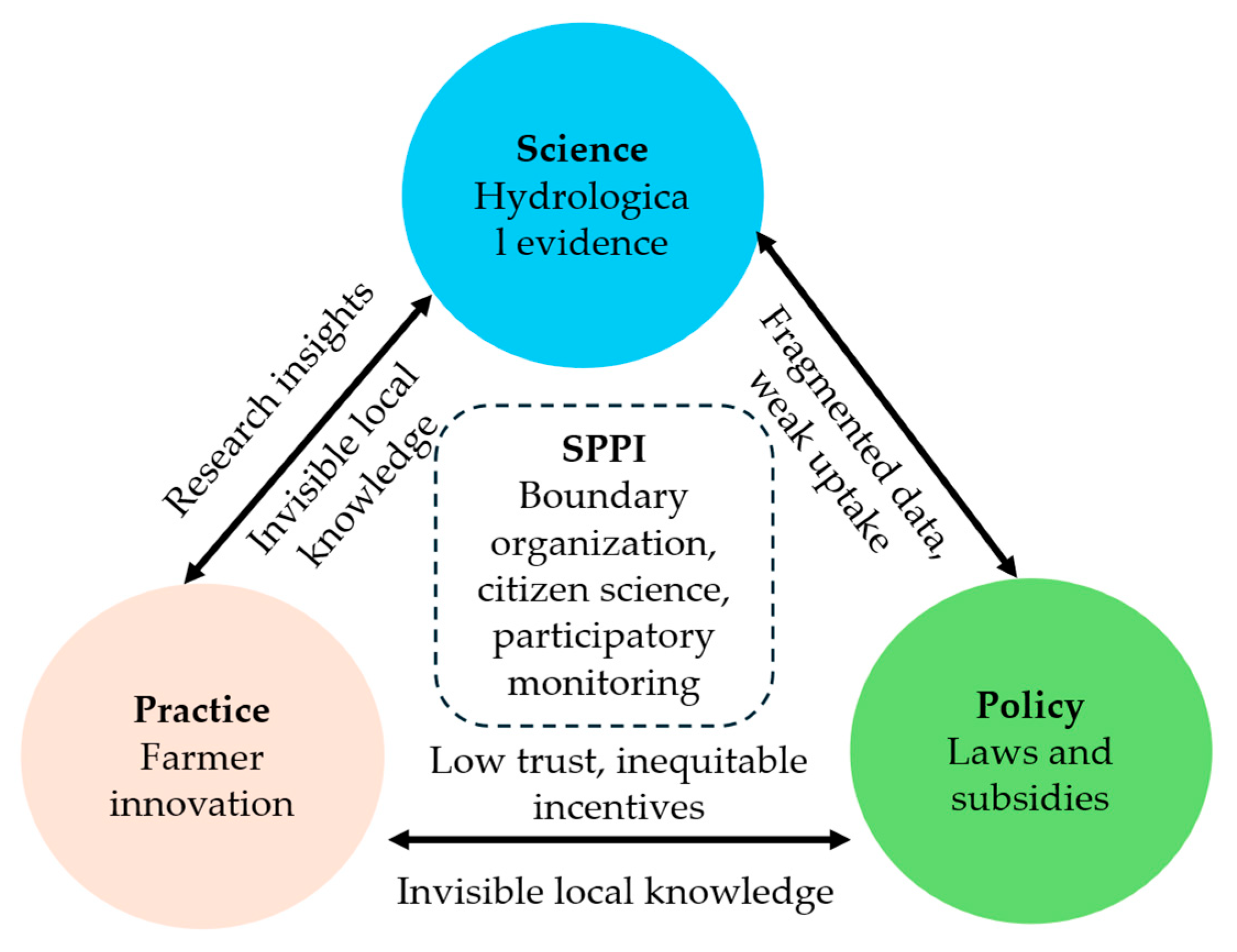

3.1. Conceptual and Analytical Framework

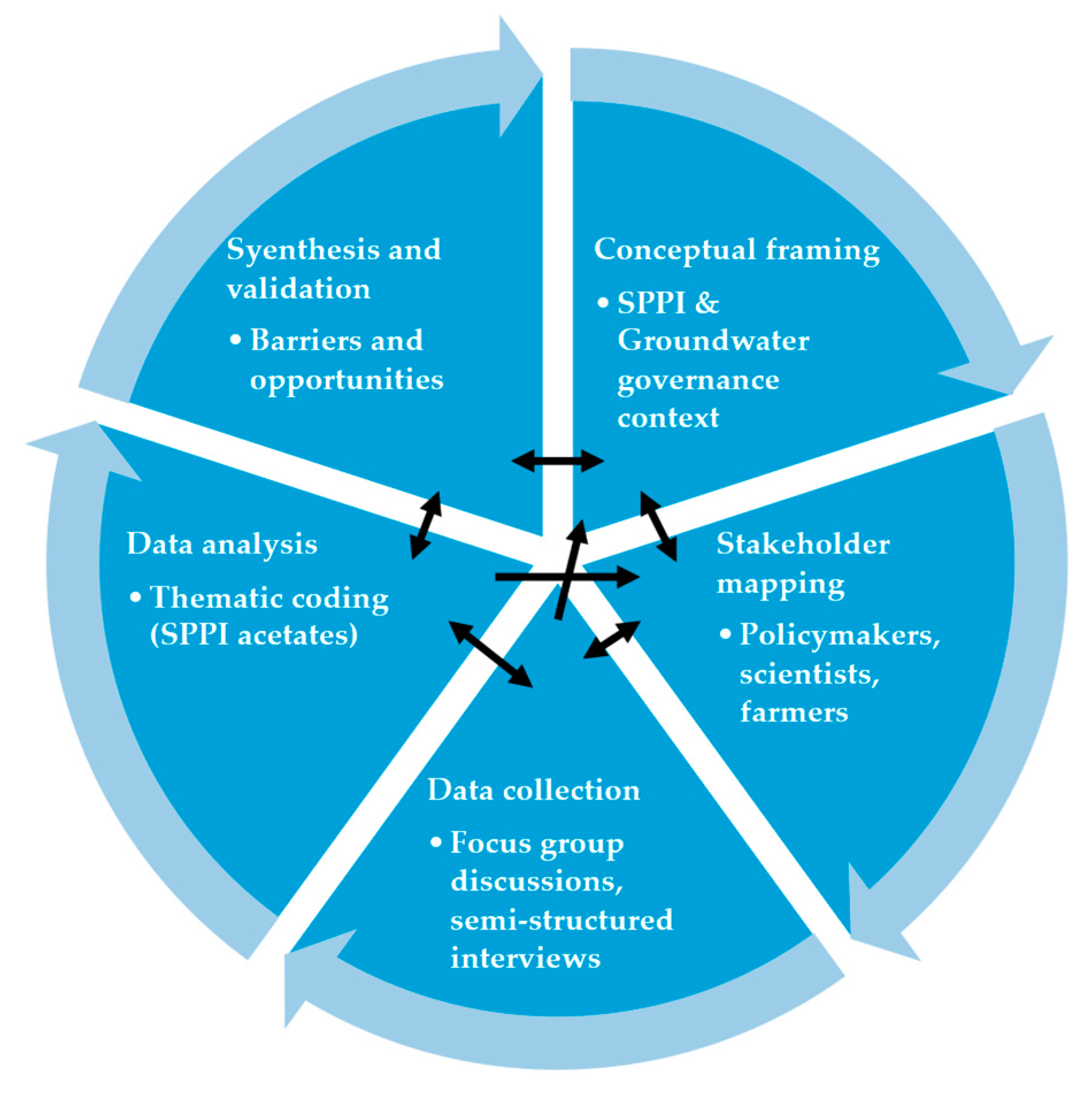

3.2. Research Design and Approach

- (a)

- Conceptual framing: development of research questions informed by SPPI theory and existing groundwater governance literature.

- (b)

- Stakeholder mapping: identification of policymakers, scientists, and farmers using purposive and snowball sampling.

- (c)

- Data collection: conducting focus group discussions (FGDs) and semi-structured interviews.

- (d)

- Data analysis: transcription, translation, and thematic coding (both deductive and inductive).

- (e)

- Synthesis and validation: triangulation of insights across actor groups to identify impediments and opportunities for science–policy–practice alignment.

- (a)

- What institutional, political and behavioural impediments limit the integration of scientific evidence into groundwater policy and practice in Pakistan’s Indus Basin?

- (b)

- How do informal institutions and farmer-led innovations shape groundwater governance outcomes?

- (c)

- What context-appropriate pathways can support more adaptive, inclusive and evidence-informed groundwater governance within the SPPI framework?

3.3. Stakeholder Identification and Sampling

- i.

- Policymakers from federal and provincial water, irrigation, and agriculture departments;

- ii.

- Scientists and researchers from national and provincial R&D institutions and academia;

- iii.

- Farmers representing both smallholders (<5 hectares) and medium-scale landowners (5–20 hectares).

3.4. Data Collection and Analysis Procedures

- Oij = observed frequency for the i-th category (SPPI function) and j-th stakeholder group,

- Eij = expected frequency, computed as

3.5. Pre-Conditions

3.6. Ethical Considerations

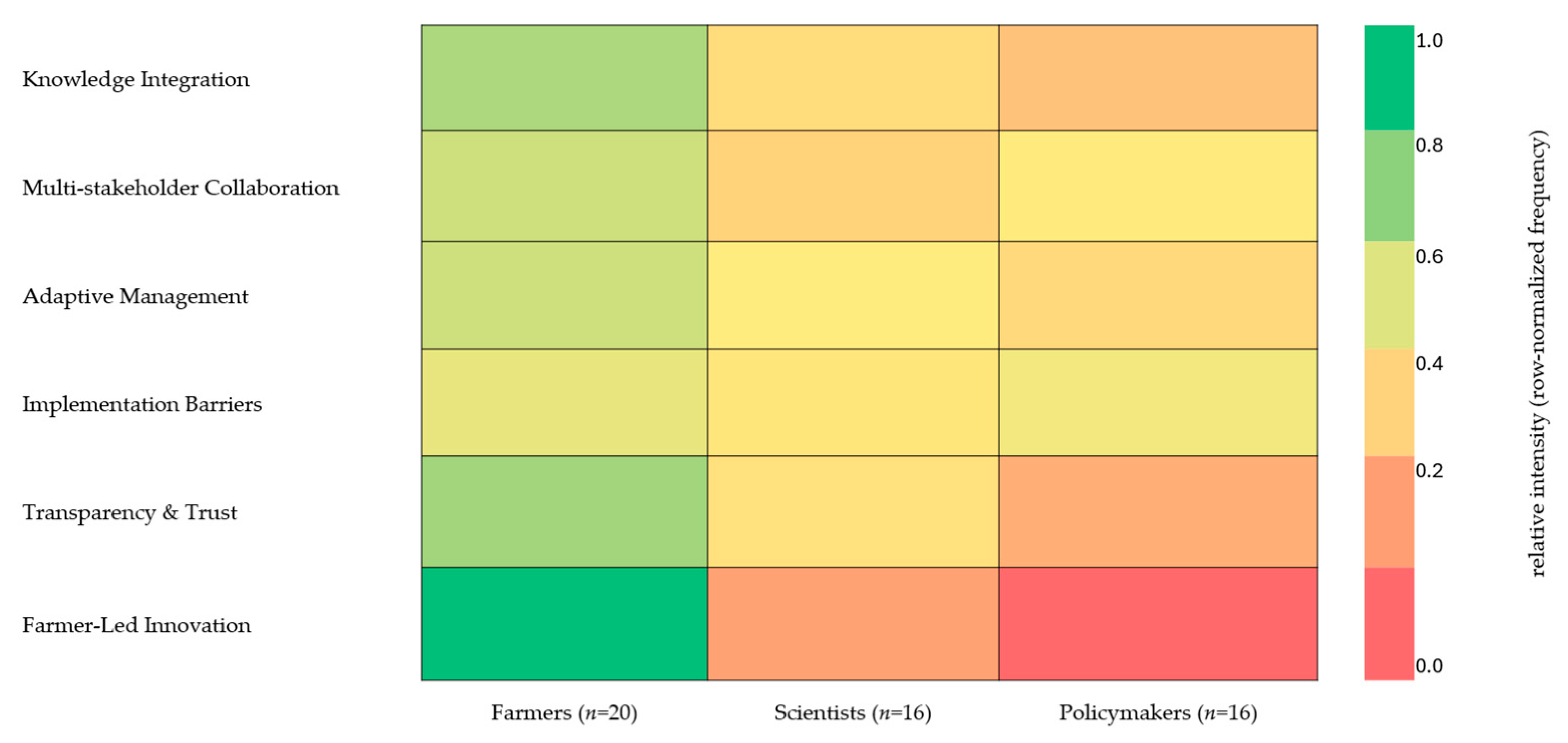

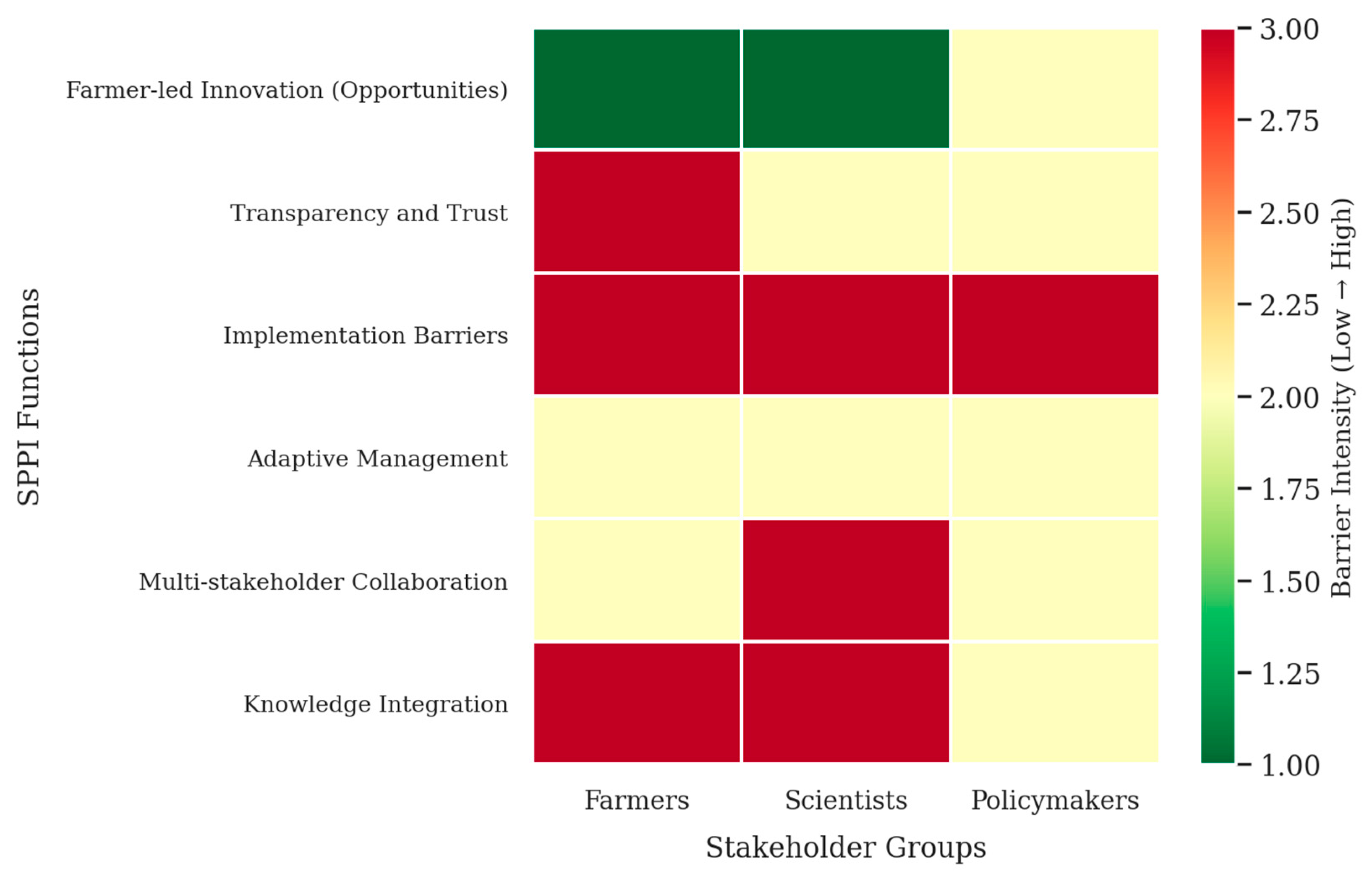

4. Results and Discussion—Barriers and Opportunities in Embedding Science into Policy and Practice

4.1. Knowledge Integration

4.2. Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration

4.3. Adaptive Management

4.4. Implementation Barriers

4.5. Transparency and Trust

4.6. Farmer-Led Innovations and Opportunities

4.7. Synthesis Across Stakeholders

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qureshi, A. Challenges and Opportunities of Groundwater Management in Pakistan. In Groundwater of South Asia; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 735–757. [Google Scholar]

- Cheema, M.J.; Immerzeel, W.W.; Bastiaanssen, W.G.M. Spatial Quantification of Groundwater Abstraction in the Irrigated Indus Basin. Groundwater 2014, 52, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, F.U.; Fatima, B.; Ashraf, M. Challenges to irrigated crop zones of Punjab and Sindh provinces in the wake of climate variability. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Nat. Resour. 2021, 27, 556207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Ashraf, M.; Imran, M.; Salam, H.A.; Hasan, F.U.; Khan, A.D. Groundwater Investigations and Mapping in the Lower Indus Plain; Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR): Islamabad, Pakistan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, F.; Fatima, B. A Review of Drivers Contributing to Unsustainable Groundwater Consumption in Pakistan. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 29, 101414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherji, A. Sustainable Groundwater Management in India Needs a Water-Energy-Food Nexus Approach. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2020, 44, 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wester, P.; Hoogesteger, J.; Vincent, L. Local IWRM organizations for groundwater regulation: The experiences of the Aquifer Management Councils (COTAS) in Guanajuato, Mexico. Nat. Resour. Forum 2009, 33, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villholth, K.; Conti, K. Groundwater governance: Rationale, definition, current state and heuristic framework. In Advances in Groundwater Governance; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Famiglietti, J. The global groundwater crisis. Nat. Clim. Change 2014, 4, 945–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.; Scanlon, B.; Döll, P.; Rodell, M.; van Beek, R.; Wada, Y.; Longuevergne, L.; Leblanc, M.; Famiglietti, J.S.; Edmunds, M.; et al. Ground water and climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, L.; Anderies, J.M.; Campbell, B.; Folke, C.; Hatfield-Dodds, S.; Hughes, T.P.; Wilson, J. Governance and the capacity to manage resilience in regional social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, M.C.; Morehouse, B.J. The co-production of science and policy in integrated climate assessments. Glob. Environ. Change 2005, 15, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, D.; Clark, W.C.; Alcock, F.; Dickson, N.M.; Eckley, N.; Guston, D.H.; Jäger, J.; Mitchell, R.B. Knowledge Systems for Sustainable Development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8086–8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvitanovic, C.; Hobday, A.J.; van Kerkhoff, L.; Wilson, S.K.; Dobbs, K.; Marshall, N.A. Improving knowledge exchange among scientists and decision-makers to facilitate the adaptive governance of marine resources: A review of knowledge and research needs. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2015, 112, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazey, L.; Evely, A.C.; Reed, M.S.; Stringer, L.C.; Kruijsen, J.; White, P.C.L.; Newsham, A.; Jin, L.; Cortazzi, M.; Phillipson, J.; et al. Knowledge exchange: A review and research agenda for environmental management. Environ. Conserv. 2013, 40, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kerkhoff, L.; Lebel, L. Linking knowledge and action for sustainable development. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2006, 31, 445–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnhout, E.; Metze, T.; Wyborn, C.; Klenk, N.; Louder, E. The politics of co-production: Participation, power, and transformation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 42, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.L., II; Janetos, A.C.; Verburg, P.H.; Murray, A.T. Land system architecture: Using land systems to adapt and mitigate global environmental change. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 395–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazey, I.; Schäpke, N.; Caniglia, G.; Patterson, J.; Hultman, J.; van Mierlo, B.; Säwe, F.; Wiek, A.; Wittmayer, J.; Aldunce, P.; et al. Ten essentials for action-oriented and second order energy transitions, transformations and climate change research. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 40, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, D.; Akhter, M.; Nasrallah, N. Understanding Pakistan’s Water-Security Nexus; United States Institute of Peace: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, F.; Dare, L.; Sinclair, D. Governing groundwater in the Indus Basin: Barriers to effective groundwater management and pathways for reform. Environ. Sci. Policy 2025, 173, 104247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PBOS. Pakistan Statistical Yearbook 2023; Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBOS), Government of Pakistan: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2023.

- World Bank. Pakistan Development Update 2022: Reviving Economic Stability; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.worldbank.org (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Lytton, L.; Ali, A.; Garthwaite, B.; Punthakey, J.F.; Saeed, B.A. Groundwater in Pakistan’s Indus Basin: Present and Future Prospects; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Asad Sarwar, Q. Water Management in the Indus Basin in Pakistan: Challenges and Opportunities. Mt. Res. Dev. 2011, 31, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GoP. National Water Policy; Ministry of Water Resources, Governmnet of Pakistan (GoP): Islamabad, Pakistan, 2018.

- Dharpure, J.K.; Howat, I.M.; Kaushik, S. Declining groundwater storage in the Indus basin revealed using GRACE and GRACE-FO data. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2024WR038279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoCC. National Climate Change Policy; Ministry of Climate Change (MoCC), Government of Pakistan: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2021.

- Rana, A.W.; Gill, S.; Meinzen-Dick, R.; ElDidi, H. Strengthening Groundwater Governance in Pakistan; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Watto, M.A.; Mugera, A.W. Groundwater depletion in the Indus Plains of Pakistan: Imperatives, repercussions and management issues. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2016, 14, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M. The Chi-square test of independence. Biochem. Medica 2013, 23, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadow, A.M.; Ferguson, D.B.; Guido, Z.; Horangic, A.; Owen, G.; Wall, T. Moving toward the deliberate coproduction of climate science knowledge. Weather. Clim. Soc. 2015, 7, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bont, C.; Börjeson, L. Policy Over Practice: A Review of Groundwater Governance Research in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Commons 2024, 18, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbing, J.; Wit, M.J. The Grootfontein aquifer: Governance of a hydro social system at Nash equilibrium. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2018, 114, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guston, D. Boundary Organizations in Environmental Policy and Science: An Introduction. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2001, 26, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norström, A.V.; Cvitanovic, C.; Löf, M.F.; West, S.; Wyborn, C.; Balvanera, P.; Bednarek, A.T.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; De Bremond, A.; et al. Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.; Evely, A.C.; Cundill, G.; Fazey, I.; Glass, J.; Laing, A.; Newig, J.; Parrish, B.; Prell, C.; Raymond, C.; et al. What is Social Learning? Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, r1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyborn, C.; Datta, A.; Montana, J.; Ryan, M.; Leith, P.; Chaffin, B.; Miller, C.; van Kerkhoff, L. Co-Producing Sustainability: Reordering the Governance of Science, Policy, and Practice. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2019, 44, 319–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.A.; Banister, J.M. The Dilemma of Water Management ‘Regionalization’ in Mexico under Centralized Resource Allocation. In Integrated Water Resources Management in Latin America; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, G.; Brown, R.; Bos, J.; Bakker, K. The role of science-policy interface in sustainable urban water transitions: Lessons from Rotterdam. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 73, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffin, B.C.; Gosnell, H.; Cosens, B.A. A decade of adaptive governance scholarship: Synthesis and future directions. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, T. Taming the Anarchy: Groundwater Governance in South Asia; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, D.; Marschke, M.; Plummer, R. Adaptive co-management and the paradox of learning. Glob. Environ. Change 2008, 18, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.L. Water rights for groundwater environments as an enabling condition for adaptive water governance. Ecol. Soc. 2022, 27, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Closas, A.; Villholth, K. Groundwater governance: Addressing core concepts and challenges. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2019, 7, e1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SPPI Theme | Farmers | Scientists | Policymakers | Row Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Integration | 38 | 27 | 25 | 90 |

| Multi-stakeholder Collaboration | 25 | 19 | 21 | 65 |

| Adaptive Management | 18 | 15 | 14 | 47 |

| Implementation Barriers | 34 | 30 | 33 | 97 |

| Transparency & Trust | 20 | 14 | 12 | 46 |

| Farmer-Led Innovation | 22 | 10 | 8 | 40 |

| Total | 157 | 115 | 113 | 385 |

| SPPI Function | Dominant Impediments (From Stakeholders) | Evidence Basis | Practical Levers (Policy/Institutional) | Expected Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge integration | Fragmented datasets; late, non-actionable reporting | FGDs + interviews across all groups | Provincial open-data dashboards; joint scientist–planner data teams; farmer-facing advisories | Higher salience & uptake of science |

| Multi-stakeholder collaboration | Episodic, donor-driven events; low farmer voice | FGDs (farmers, scientists) | Standing tri-partite forums; boundary orgs in provinces; co-production MOUs | Stable dialogue; shared priorities |

| Adaptive management | Static plans; no seasonal/annual adjustment | All groups | Seasonal water budgets; rule revision windows; extension on adaptive cropping | Iterative learning; flexible rules |

| Implementation | No metering/licensing; subsidy distortions; thin enforcement | All groups | Phased licensing; targeted subsidy reforms; compliance monitoring with CS support | Enforceability with equity |

| Transparency & trust | Delayed releases; inaccessible formats | All groups | Quarterly bulletins (Urdu/Sindhi); real-time online status; citizen-science validation | Legitimacy & cooperation |

| Farmer-led innovation | Practices invisible to policy; inequity in scaling | Farmers + scientists | Document & evaluate recharge/water-sharing; demos; integrate farmer data | Hybrid knowledge; scalable pilots |

| SPPI Function | χ2 (df = 10) | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Integration | 5.83 | 0.83 | No significant difference across groups |

| Multi-stakeholder Collaboration | 4.12 | 0.74 | Shared perceptions of weak collaboration |

| Adaptive Management | 6.01 | 0.79 | Convergent views on institutional rigidity |

| Implementation Barriers | 7.25 | 0.68 | Consensus on weak enforcement and political constraints |

| Transparency & Trust | 3.45 | 0.89 | Similar concerns across actors |

| Farmer-led Innovation | 2.17 | 0.91 | Common recognition of emerging local initiatives |

| Overall Chi-square | 5.83 (10) | 0.83 | No statistically significant differences among stakeholder groups |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hasan, F.u. Impediments to, and Opportunities for, the Incorporation of Science into Policy and Practice into the Sustainable Management of Groundwater in Pakistan. Water 2025, 17, 3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243496

Hasan Fu. Impediments to, and Opportunities for, the Incorporation of Science into Policy and Practice into the Sustainable Management of Groundwater in Pakistan. Water. 2025; 17(24):3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243496

Chicago/Turabian StyleHasan, Faizan ul. 2025. "Impediments to, and Opportunities for, the Incorporation of Science into Policy and Practice into the Sustainable Management of Groundwater in Pakistan" Water 17, no. 24: 3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243496

APA StyleHasan, F. u. (2025). Impediments to, and Opportunities for, the Incorporation of Science into Policy and Practice into the Sustainable Management of Groundwater in Pakistan. Water, 17(24), 3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243496