Enhancing Methane Production in a Sidestream Bioelectrochemical Anaerobic Digestion of Sewage Sludge: Focusing on Energy Efficiency and Tradeoffs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inoculum and Substrates

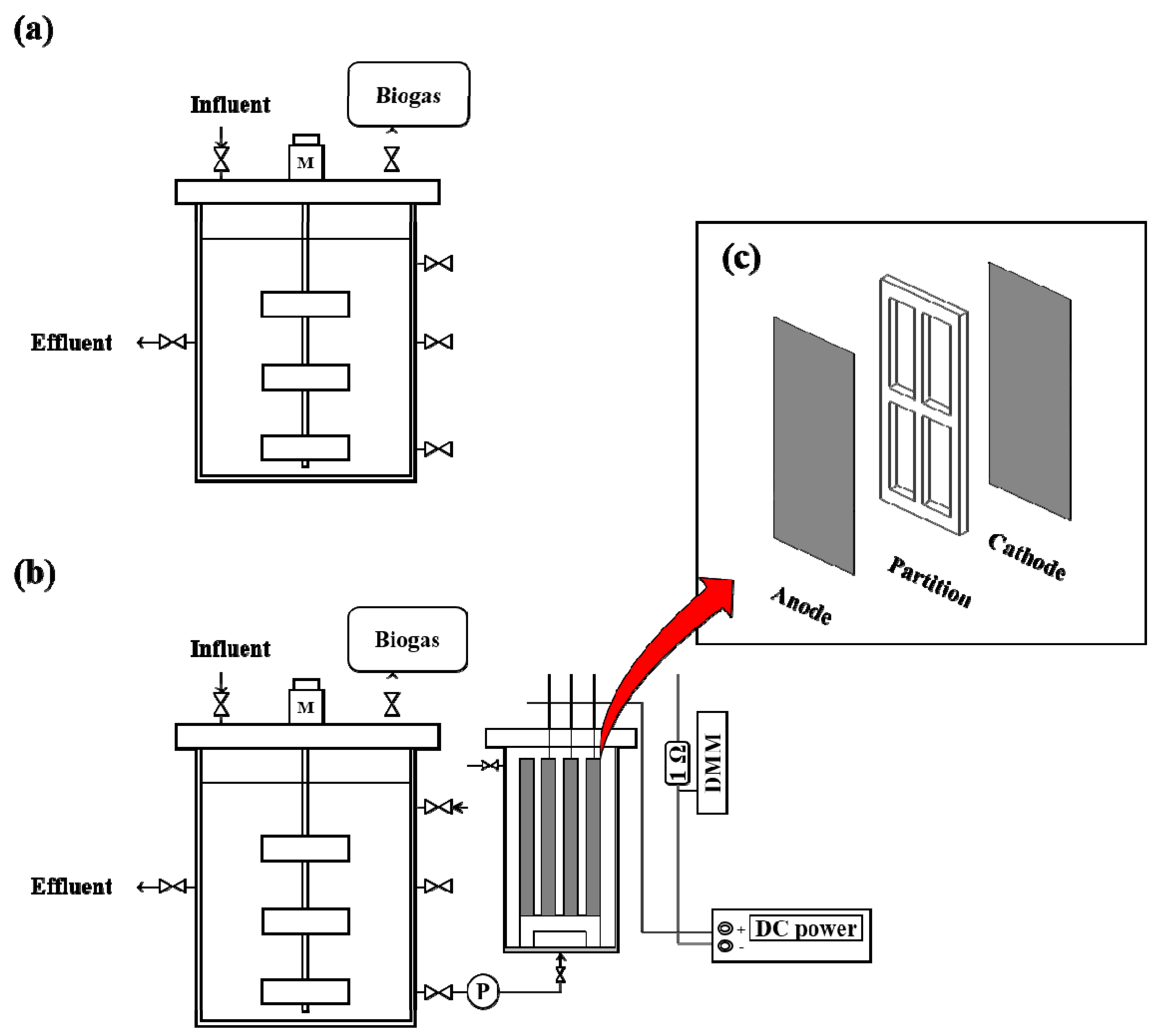

2.2. Reactor Configuration

2.3. Reactor Operation

2.4. Analytical Methods

2.5. Electrical Efficiency Calculation

2.6. Microbial Community Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

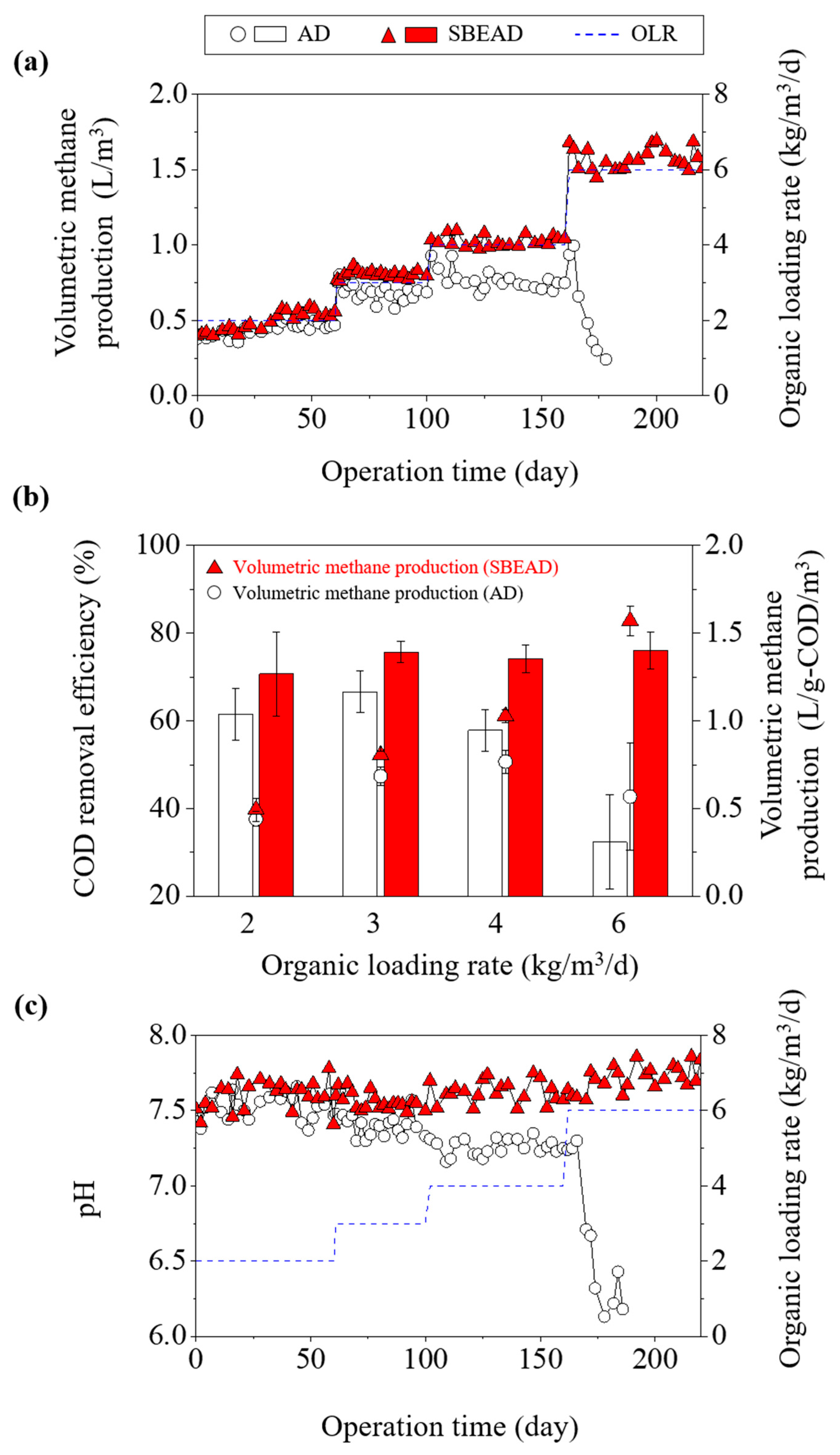

3.1. Comparative Analysis of Process Performance and Stability

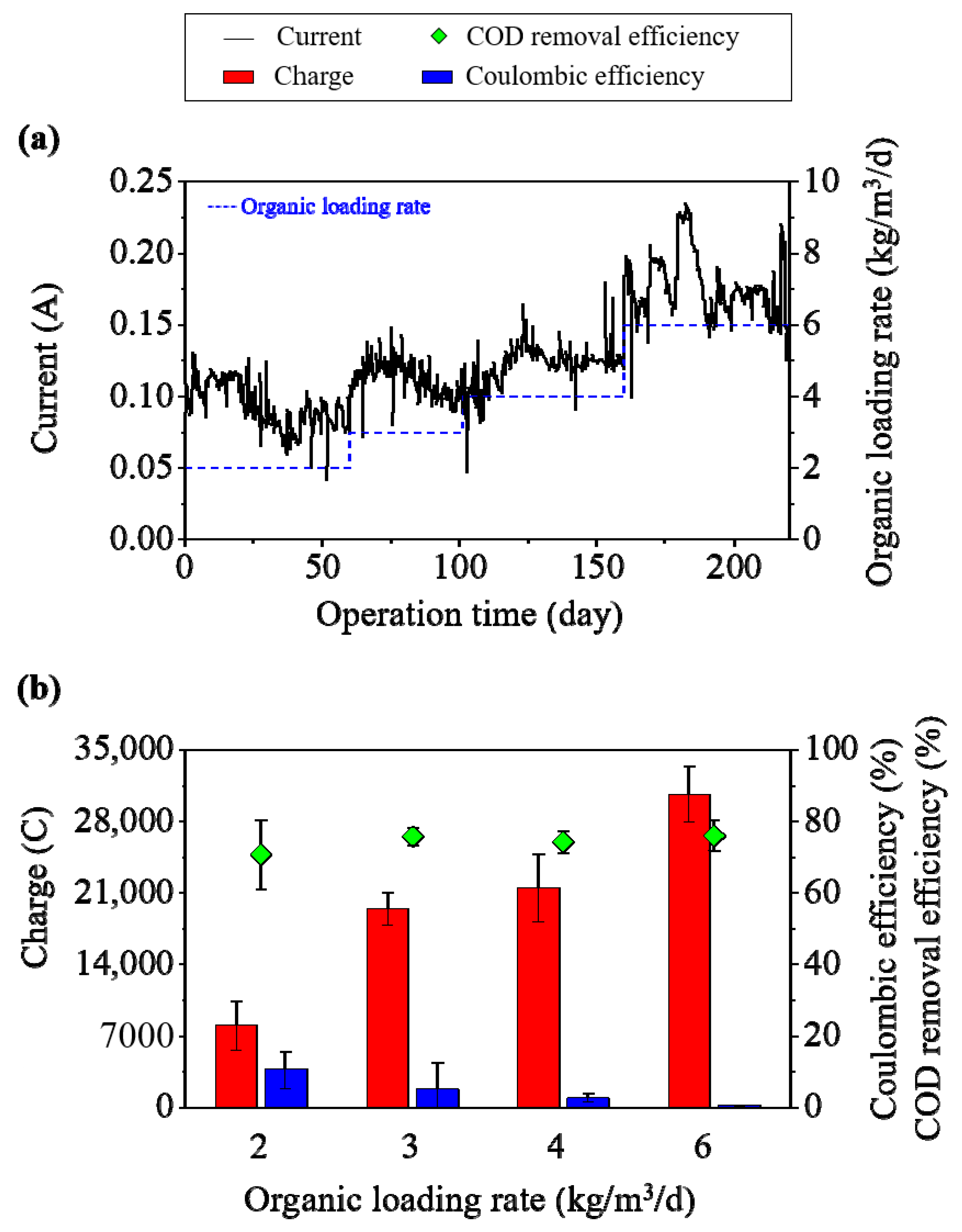

3.2. Bioelectrochemical Performance of Sidestream Bioelectrochemical Anaerobic Digestion

3.3. Energy Recovery Performance and Methane Amplification in Sidestream Bioelectrochemical Systems

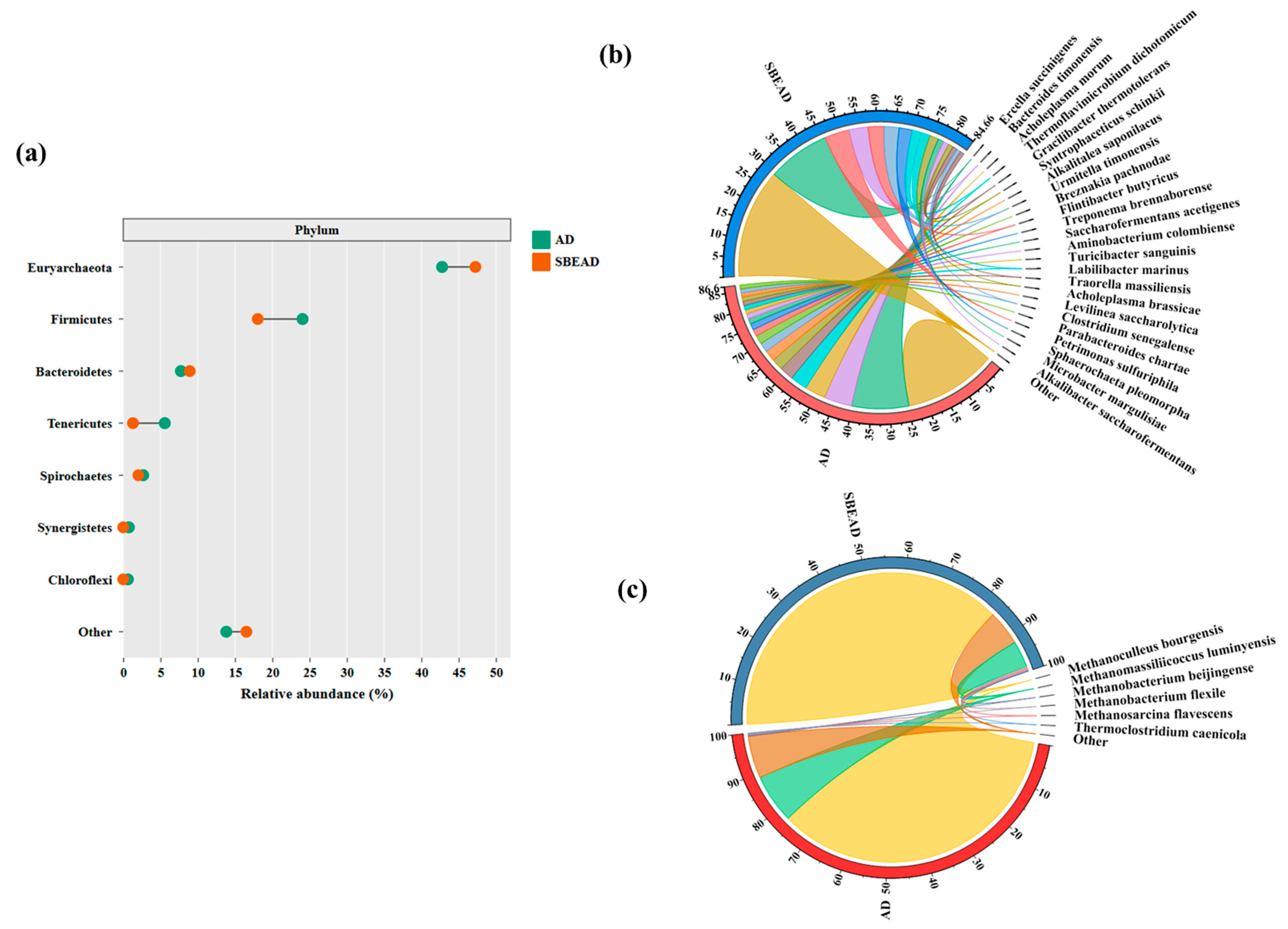

3.4. Microbial Community

3.4.1. Bacterial Community Structure

3.4.2. Archaeal Community Structure

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kadam, R.; Panwar, N. Recent advancement in biogas enrichment and its applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 73, 892–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, R.; Jo, S.; Lee, J.; Khanthong, K.; Jang, H.; Park, J. A review on the anaerobic co-digestion of livestock manures in the context of sustainable waste management. Energies 2024, 17, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, C.; Liu, W.; Zou, S. Optimized alkaline pretreatment of sludge before anaerobic digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 123, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-G.; Lee, B.; Park, H.-R.; Jun, H.-B. Long-term evaluation of methane production in a bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion reactor according to the organic loading rate. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 273, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Saratale, R.G.; Kadier, A.; Sivagurunathan, P.; Zhen, G.; Kim, S.-H.; Saratale, G.D. A review on bio-electrochemical systems (BESs) for the syngas and value added biochemicals production. Chemosphere 2017, 177, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Lee, B.; Shin, W.; Jo, S.; Jun, H. Application of a rotating impeller anode in a bioelectrochemical anaerobic digestion reactor for methane production from high-strength food waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 259, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Song, Y.-C.; Ahn, Y. Electroactive microorganisms in bulk solution contribute significantly to methane production in bioelectrochemical anaerobic reactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 259, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hari, A.R.; Katuri, K.P.; Ruiz-Haddad, L.; Saikaly, P.E. Pre-enriched electrodes, bioelectrochemical processes, and biomass retention collectively enhance methane production in integrated microbial electrolysis cell-anaerobic digestion system. J. Power Sources 2025, 646, 237271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Xiao, C.; Workie, E.; Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Tong, Y.W. Bioelectrochemical enhancement of methanogenic metabolism in anaerobic digestion of food waste under salt stress conditions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 13526–13535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Chen, X.; Han, Y.; Liu, J.; Guo, X. Bioelectrochemical enhancement of the anaerobic digestion of thermal-alkaline pretreated sludge in microbial electrolysis cells. Renew. Energy 2018, 115, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-G.; Lee, B.; Kwon, H.-J.; Park, H.-R.; Jun, H.-B. Effects of a novel auxiliary bio-electrochemical reactor on methane production from highly concentrated food waste in an anaerobic digestion reactor. Chemosphere 2019, 220, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beegle, J.R.; Borole, A.P. Energy production from waste: Evaluation of anaerobic digestion and bioelectrochemical systems based on energy efficiency and economic factors. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 96, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, K.; Raj, T.; Ramanaiah, S.; Kumar, G.; Jeon, B.-H.; Jang, M.; Kim, S.-H. Regulation and augmentation of anaerobic digestion processes via the use of bioelectrochemical systems. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 346, 126628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JIS G 4304; Hot-Rolled Stainless Steel Plate, Sheet and Strip. Japanese Standards Association: Tokyo, Japan, 2021.

- American Public Health Association. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Kadam, R.; Jo, S.; Khanthong, K.; Hwang, M.; Park, J. Influence of starting-up inoculated granule’s color on long-term ANAMMOX performances and microbial-enzymatical characteristics under various nitrogen loads. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vrieze, J.; Gildemyn, S.; Arends, J.B.; Vanwonterghem, I.; Verbeken, K.; Boon, N.; Verstraete, W.; Tyson, G.W.; Hennebel, T.; Rabaey, K. Biomass retention on electrodes rather than electrical current enhances stability in anaerobic digestion. Water Res. 2014, 54, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhar, H.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Vaidya, A.N. Effect of organic loading rate during anaerobic digestion of municipal solid waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 217, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puthumana, A.B.; Kaparaju, P. Impact of Organic Load on Methane Yields and Kinetics during Anaerobic Digestion of Sugarcane Bagasse: Optimal Feed-to-Inoculum Ratio and Total Solids of Reactor Working Volume. Energies 2024, 17, 5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eerten-Jansen, M.C.; Jansen, N.C.; Plugge, C.M.; de Wilde, V.; Buisman, C.J.; ter Heijne, A. Analysis of the mechanisms of bioelectrochemical methane production by mixed cultures. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2015, 90, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Quan, X.; Zhao, H. Evaluation on direct interspecies electron transfer in anaerobic sludge digestion of microbial electrolysis cell. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 200, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleutels, T.H.; Darus, L.; Hamelers, H.V.; Buisman, C.J. Effect of operational parameters on Coulombic efficiency in bioelectrochemical systems. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 11172–11176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-C.; Feng, Q.; Ahn, Y. Performance of the bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge at different hydraulic retention times. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Wang, Y.; Lin, H.; Van Lierop, L.; Hu, B. Facilitating solid-state anaerobic digestion of food waste via bio-electrochemical treatment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 166, 112637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Lu, X.; Cai, T.; Niu, C.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Zhen, G. Magnetite-enhanced bioelectrochemical stimulation for biodegradation and biomethane production of waste activated sludge. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 789, 147859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Gao, Y.; Yu, K.; Zhou, H.; De Costa, Y.G.; Yi, S.; Zhuang, W.-Q. Microbial community in in-situ waste sludge anaerobic digestion with alkalization for enhancement of nutrient recovery and energy generation. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 295, 122277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; He, Q.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Peng, X. A mesophilic anaerobic digester for treating food waste: Process stability and microbial community analysis using pyrosequencing. Microb. Cell Factories 2016, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Park, J.-H.; Kang, H.-J.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, T.J.; Park, H.-D. Distribution and abundance of Spirochaetes in full-scale anaerobic digesters. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 145, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Militon, C.; Hamdi, O.; Michotey, V.; Fardeau, M.-L.; Ollivier, B.; Bouallagui, H.; Hamdi, M.; Bonin, P. Ecological significance of Synergistetes in the biological treatment of tuna cooking wastewater by an anaerobic sequencing batch reactor. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 18230–18238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, J.L.; Rojas, P.; Morato, A.; Mendez, L.; Ballesteros, M.; González-Fernández, C. Microbial communities of biomethanization digesters fed with raw and heat pre-treated microalgae biomasses. Chemosphere 2017, 168, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gelder, A.H.; Sousa, D.Z.; Rijpstra, W.I.C.; Damste, J.S.S.; Stams, A.J.; Sanchez-Andrea, I. Ercella succinigenes gen. nov., sp. nov., an anaerobic succinate-producing bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 2449–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tukanghan, W.; Hupfauf, S.; Gómez-Brandón, M.; Insam, H.; Salvenmoser, W.; Prasertsan, P.; Cheirsilp, B.; O-Thong, S. Symbiotic Bacteroides and Clostridium-rich methanogenic consortium enhanced biogas production of high-solid anaerobic digestion systems. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2021, 14, 100685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwesh, O.M.; Barakat, K.M.; Mattar, M.Z.; Sabae, S.Z.; Hassan, S.H. Thermoflavimicrobium dichotomicum as a novel thermoalkaliphile for production of environmental and industrial enzymes. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2020, 10, 4811–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J.; Romanek, C.S.; Mills, G.L.; Davis, R.C.; Whitman, W.B.; Wiegel, J. Gracilibacter thermotolerans gen. nov., sp. nov., an anaerobic, thermotolerant bacterium from a constructed wetland receiving acid sulfate water. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 2089–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hao, L.; Lü, F.; Duan, H.; Zhang, H.; He, P. Syntrophic acetate-oxidizing microbial consortia enriched from full-scale mesophilic food waste anaerobic digesters showing high biodiversity and functional redundancy. Msystems 2022, 7, e00339-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, A.; Tindall, B.J.; Bardin, V.; Blanchet, D.; Jeanthon, C. Petrimonas sulfuriphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a mesophilic fermentative bacterium isolated from a biodegraded oil reservoir. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughrin, J.H.; Parekh, R.R.; Agga, G.E.; Silva, P.J.; Sistani, K.R. Microbiome diversity of anaerobic digesters is enhanced by microaeration and low frequency sound. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Andrea, I.; Sanz, J.L.; Stams, A.J. Microbacter margulisiae gen. nov., sp. nov., a propionigenic bacterium isolated from sediments of an acid rock drainage pond. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 3936–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröninger, L.; Gottschling, J.; Deppenmeier, U. Growth characteristics of Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis and expression of methyltransferase encoding genes. Archaea 2017, 2017, 2756573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.; Liu, X.; Dong, X. Methanobacterium beijingense sp. nov., a novel methanogen isolated from anaerobic digesters. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, X.; Dong, X. Methanobacterium movens sp. nov. and Methanobacterium flexile sp. nov., isolated from lake sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 61, 2974–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, T.; Fischer, M.A.; Deppenmeier, U.; Schmitz, R.A.; Rother, M. Methanosarcina flavescens sp. nov., a methanogenic archaeon isolated from a full-scale anaerobic digester. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1533–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Inoculum | Sewage Sludge |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.5 ± 0.3 | 6.2 ± 0.2 |

| Alkalinity (g/L as CaCO3) | 9.6 ± 1.5 | 3.2 ± 0.4 |

| TCOD (g/L) | 20.1 ± 2.8 | 92.4 ± 4.1 |

| SCOD (g/L) | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 62.5 ± 2.3 |

| TS (%) | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 108.2 ± 0.9 |

| VS (%) | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 88.4 ± 0.6 |

| Parameter | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Total electrode surface area (m2) | 0.864 | |

| Electrode surface area to working volume ratio (m2/m3) | 8.64 | |

| Current density (A/m2) | 2 kg/m3/d * | 34.7 ± 20.0 |

| 3 kg/m3/d | 93.2 ± 13.7 | |

| 4 kg/m3/d | 151.0 ± 19.7 | |

| 6 kg/m3/d | 219.9 ± 20.0 | |

| Coulombic Efficiency (%) | 2 kg/m3/d | 5.4 ± 5.2 |

| 3 kg/m3/d | 5.1 ± 7.4 | |

| 4 kg/m3/d | 2.7 ± 1.3 | |

| 6 kg/m3/d | 0.9 ± 0.2 | |

| Category | OLR (kg-COD/m3/d) | Energy Recovery Efficiency (%) * | Overall Energy Recovery Efficiency (%) ** | MGI **** (kJ/kJ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | 2 | 87.2 ± 1.3 | 53.6 ± 5.1 (13.3 ± 5.1) *** | - |

| 3 | 83.8 ± 0.6 | 55.8 ± 4.3 (18.5 ± 1.4) *** | - | |

| 4 | 81.0 ± 1.7 | 46.8 ± 4.0 (18.6 ± 18.6) *** | - | |

| 6 | 67.1 ± 14.8 | 23.1 ± 12.4 (3.5 ± 6.2) *** | - | |

| SBEAD | 2 | 85.2 ± 1.1 | 60.1 ± 8.0 (14.9 ± 2.0) *** | 62.8 ± 48.6 |

| 3 | 86.6 ± 1.9 | 65.4 ± 2.0 (21.7 ± 0.7) *** | 56.4 ± 29.7 | |

| 4 | 84.5 ± 1.8 | 62.5 ± 2.2 (24.9 ± 0.9) *** | 114.8 ± 35.3 | |

| 6 | 84.2 ± 2.3 | 63.8 ± 3.5 (31.7 ± 1.8) *** | 585.3 ± 135.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jun, H.; Yang, H.; Kadam, R.; Park, J. Enhancing Methane Production in a Sidestream Bioelectrochemical Anaerobic Digestion of Sewage Sludge: Focusing on Energy Efficiency and Tradeoffs. Water 2025, 17, 3497. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243497

Jun H, Yang H, Kadam R, Park J. Enhancing Methane Production in a Sidestream Bioelectrochemical Anaerobic Digestion of Sewage Sludge: Focusing on Energy Efficiency and Tradeoffs. Water. 2025; 17(24):3497. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243497

Chicago/Turabian StyleJun, Hangbae, Hyeonmyeong Yang, Rahul Kadam, and Jungyu Park. 2025. "Enhancing Methane Production in a Sidestream Bioelectrochemical Anaerobic Digestion of Sewage Sludge: Focusing on Energy Efficiency and Tradeoffs" Water 17, no. 24: 3497. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243497

APA StyleJun, H., Yang, H., Kadam, R., & Park, J. (2025). Enhancing Methane Production in a Sidestream Bioelectrochemical Anaerobic Digestion of Sewage Sludge: Focusing on Energy Efficiency and Tradeoffs. Water, 17(24), 3497. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243497