1. Introduction

Groundwater modeling under climate change has been the focus of several recent studies, which consistently find that changes in climate variables, combined with anthropogenic stressors, lead to reduced recharge, lowered water tables, altered surface–groundwater interactions, and increased vulnerability of aquifer systems. For example, Ngo et al. [

1] used a coupled SWAT-MODFLOW (Modular Finite-Difference Flow Model) model to assess future groundwater recharge in the Choushui River Alluvial Fan, Taiwan, under different Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) scenarios, finding that while some scenarios show increases, many project a long-term decrease in recharge particularly under higher-emission pathways. In Brazil, Pedrosa Bhering et al. [

2] developed a numerical model for karst and pelitic aquifers in a semi-arid watershed, projecting clear declines in water table levels, largely driven by population growth and pumping, with climate change compounding these pressures. A country-scale study in Hungary modeled shallow groundwater responses, showing that future climate impacts vary by region and dataset resolution, but the methodology provides a framework for assessing climate vulnerability of shallow groundwater resources [

3]. Moreover, in North Algeria, Kastali et al. [

4] used a 3D MODFLOW-6 regional model with climate projections from CMIP5/6 plus scenarios of groundwater extraction to show that although both climate change and abstraction reduce flows, over-pumping may have larger effects on surface and groundwater interaction than climate changes alone.

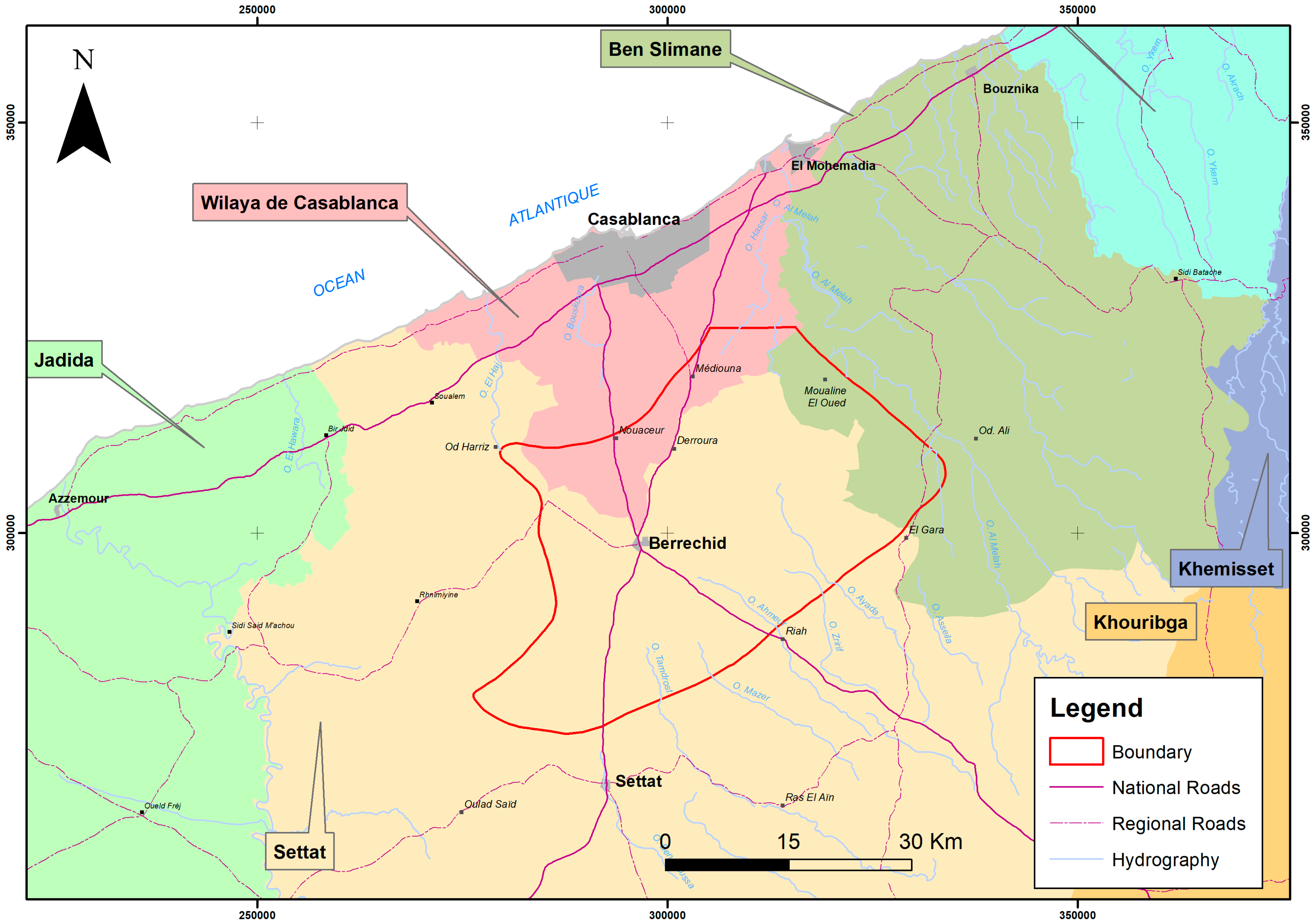

The Berrechid Plain, a major groundwater reservoir in western Morocco covering about 1500 km2 south of Casablanca, is bounded by the Settat Plateau, the Oued Mellah Valley, and the Chaouia aquifer. Despite its strategic role in regional water supply, increasing agricultural and industrial demand, coupled with recurrent droughts since the 1980s, has led to severe overexploitation and continuous water table decline.

While similar studies have investigated the combined impacts of climate change and anthropogenic pressures on aquifers in other regions of the world, limited attention has been given to Moroccan semi-arid basins such as Berrechid, where hydro-climatic variability and uncontrolled groundwater abstraction occur simultaneously. Moreover, the integration of climate-projection datasets with appropriate groundwater-withdrawal management strategies—aimed at ensuring sustainable resource use and maintaining aquifer stability—remains scarce at the regional scale in Morocco.

Building on this foundation, the present study aims to assess how future climate variability, combined with appropriate groundwater-withdrawal management strategies, may affect the hydrodynamic behavior of the Berrechid aquifer. Specifically, it seeks to (a) evaluate the current state of overexploitation, (b) project groundwater levels to 2050 under the RCP 4.5 scenario with authorized pumping rates, and (c) analyze system responses through steady-state, transient, and predictive simulations using GMS/MODFLOW.

3. Results and Discussion

The primary objective of this study is to assess the impact of climate change on the Berrechid aquifer and evaluate the most appropriate groundwater-withdrawal management strategies to ensure sustainable use of the resource and maintain aquifer stability. To achieve this, a comprehensive hydrogeological synthesis of the aquifer was conducted using all available data.

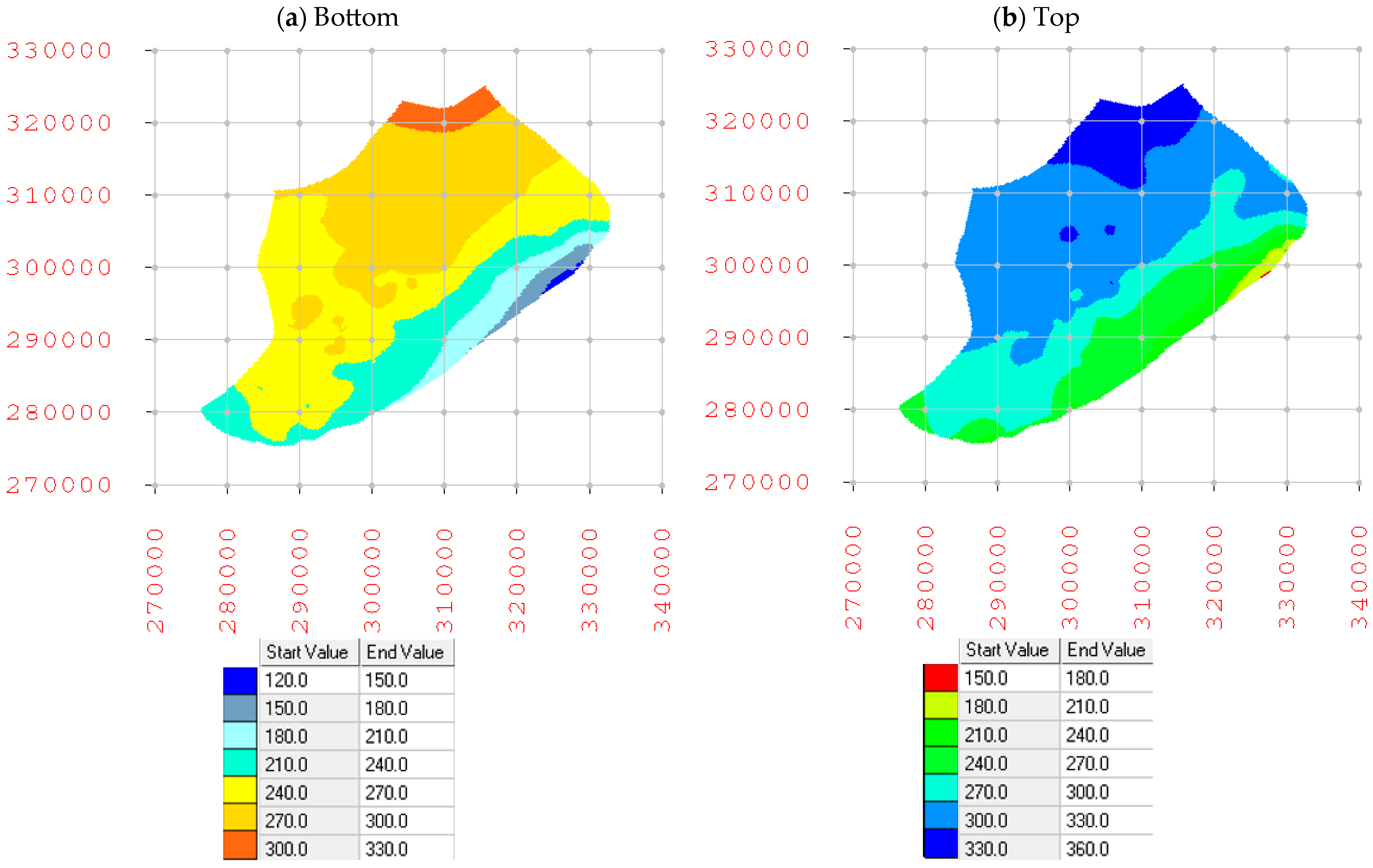

The primary aquifer is located beneath the Quaternary silts, comprising Pliocene sandstone. In certain areas, the sandstone formations rise, and the aquifer extends horizontally into older horizons. The average thickness of the aquifer is approximately 20 m and can exceed 30 m alongside fossil channels of the pre-Pliocene hydrographic network.

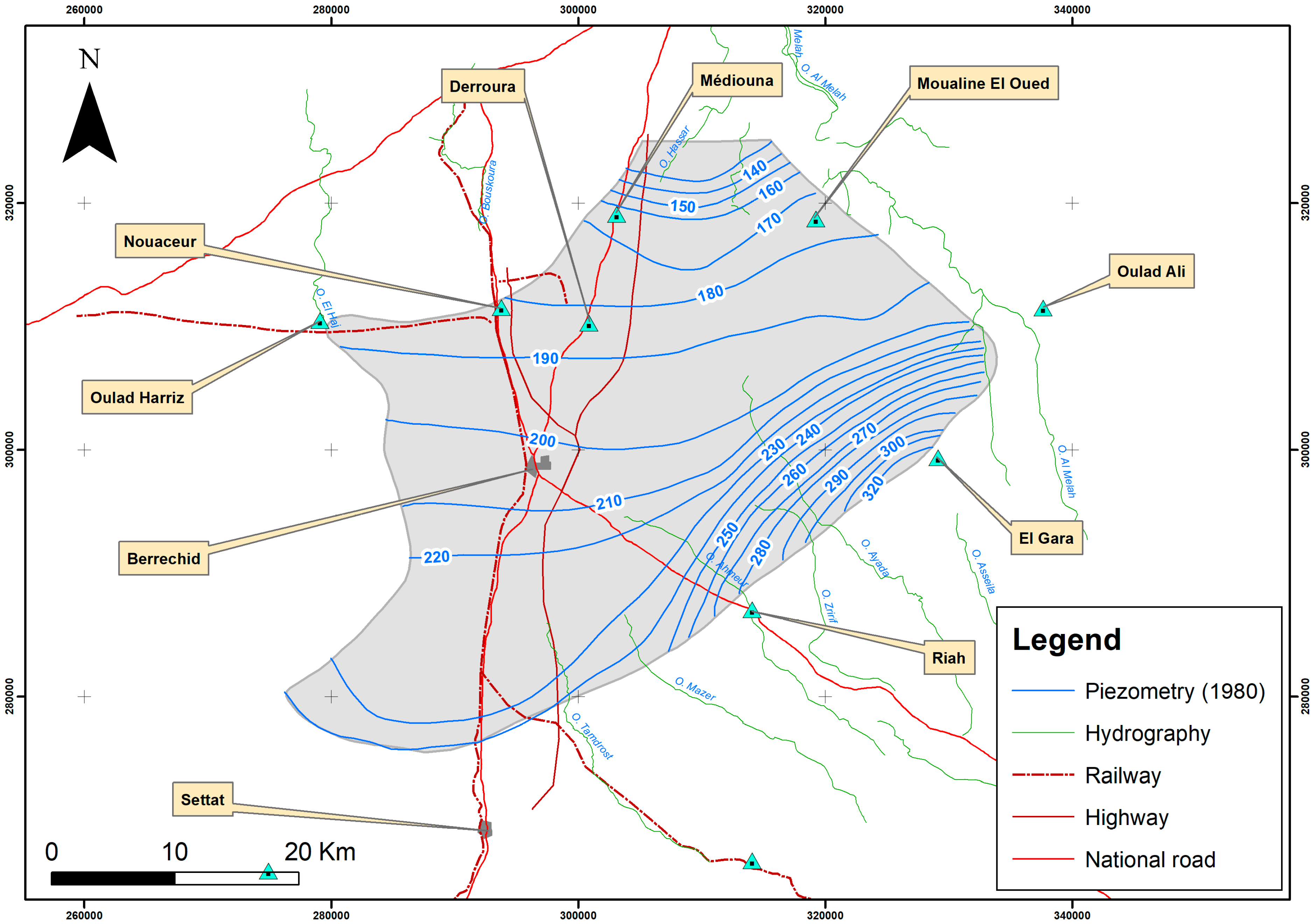

The piezometric evolution of the aquifer indicates an equilibrium state from the 1950s until 1980, followed by a deficit period extending from 1981 to the present. This deficit period is characterized by continuous and sustained declines in the aquifer, attributed to a combination of reduced rainfall and increased withdrawals, particularly during drought episodes.

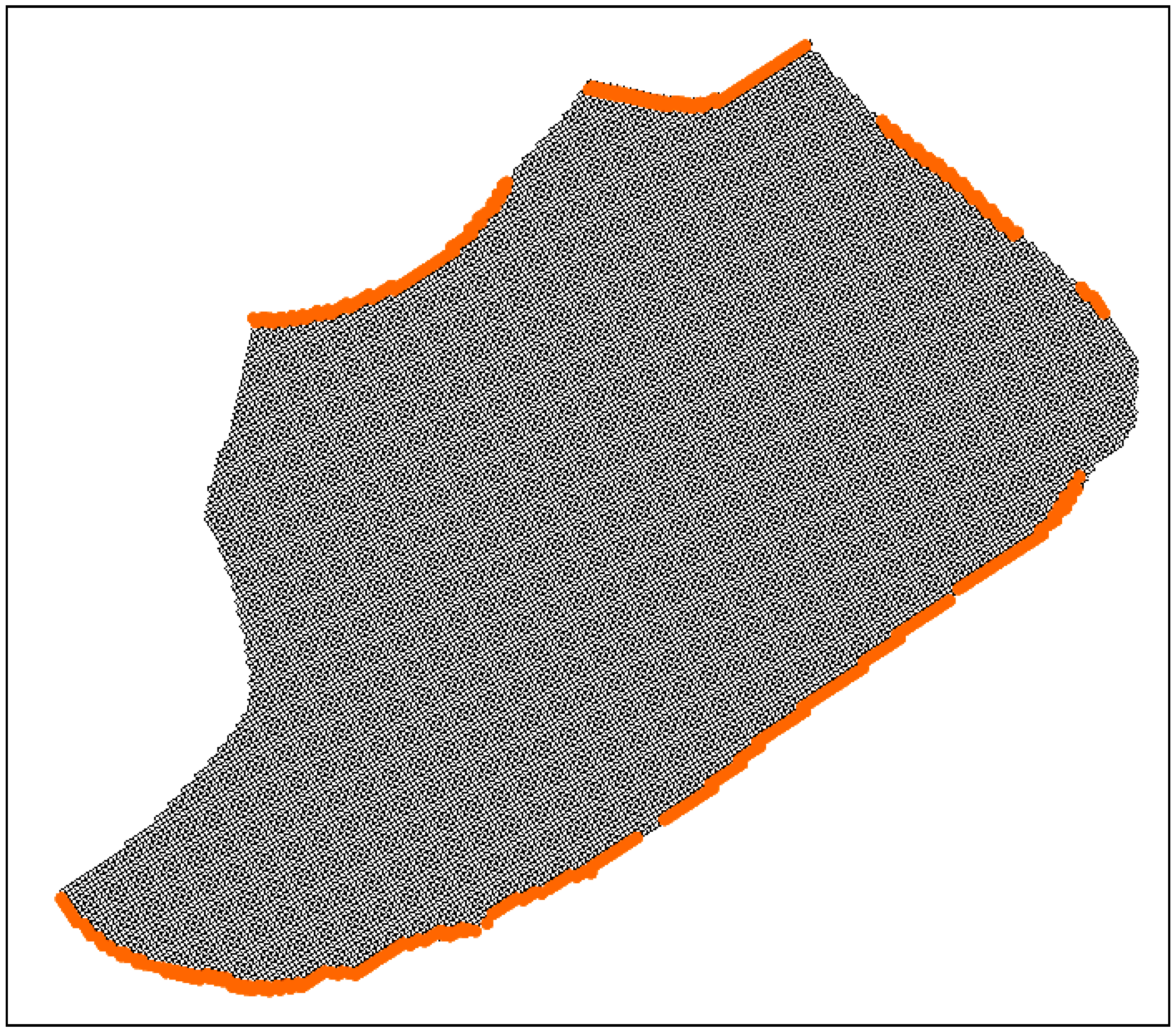

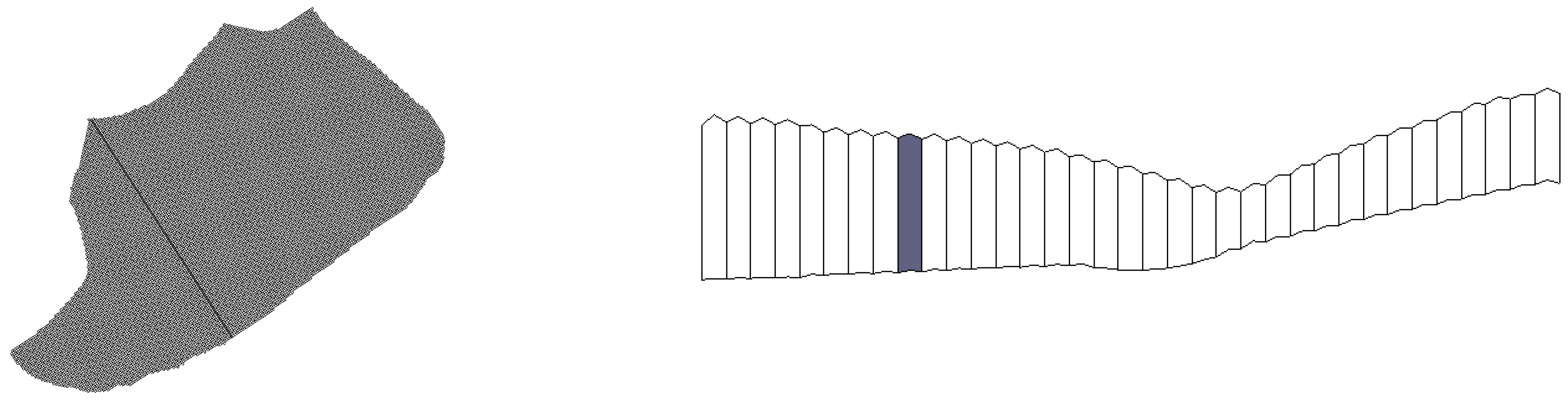

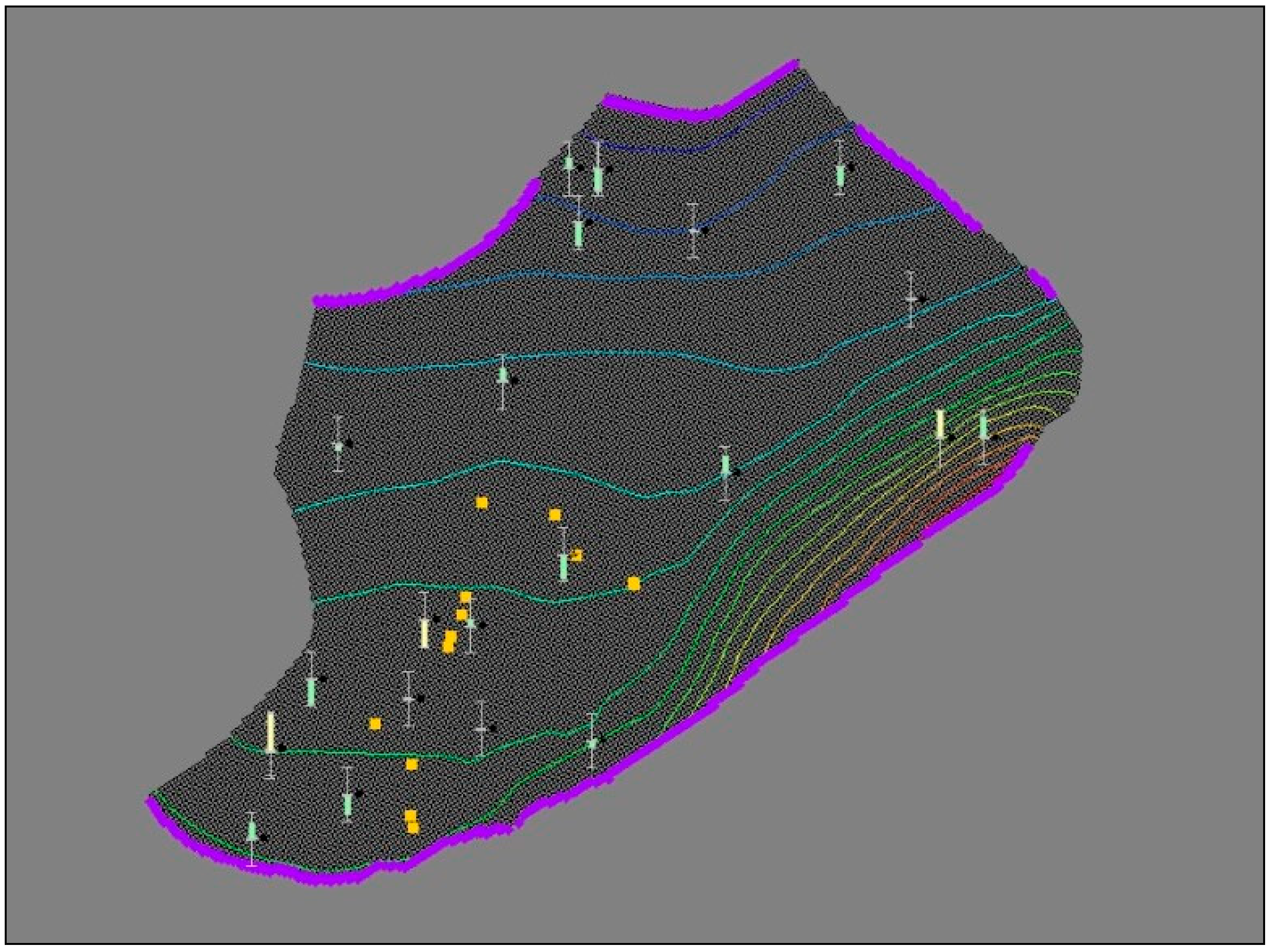

Hydrodynamic modeling of the Berrechid aquifer was conducted using the MODFLOW digital simulation software within the GMS pre-post-processor (Version 10.3). The domain discretization consisted of 266 columns and 166 lines, delineating 44,156 regular square meshes with a side length of 250 m, including 24,401 active meshes. The mesh size was selected based on the density and variability of available data.

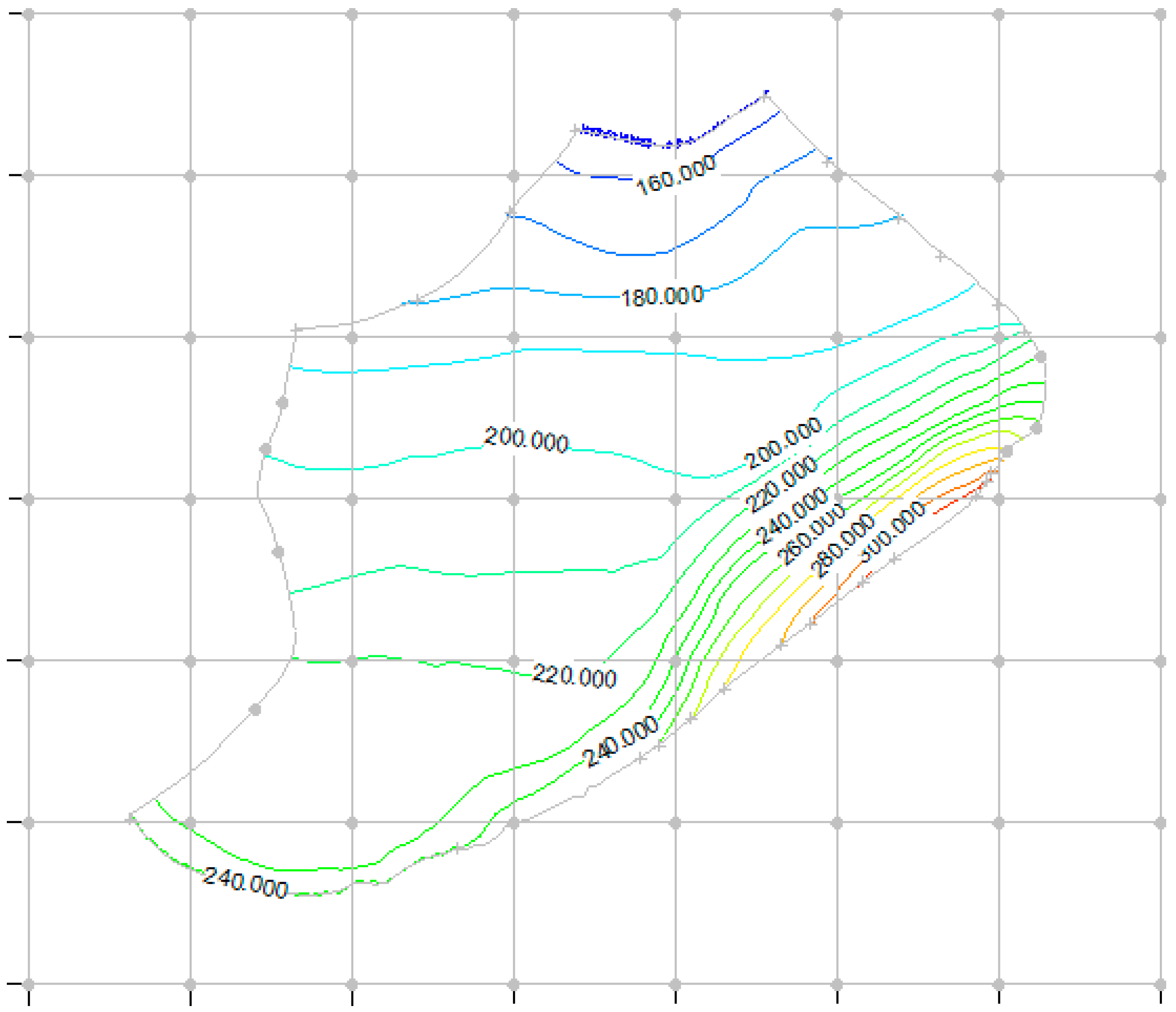

The reference piezometric state used for steady-state model calibration was the 1980 piezometric map, marking the onset of groundwater drawdown. The simulated piezometry for the same year (

Figure 9) exhibits excellent agreement with field observations, as confirmed by the comparison presented in

Figure 10. Residuals shown in

Table 3 further indicate satisfactory calibration. Part of the discrepancy arises from the fact that model-computed heads correspond to the centers of grid cells—each measuring 250 m per side—whereas observation wells are rarely located exactly at these centers. As a result, positive residuals occur when a piezometer is situated upstream of the cell center, and negative residuals appear when it is located downstream.

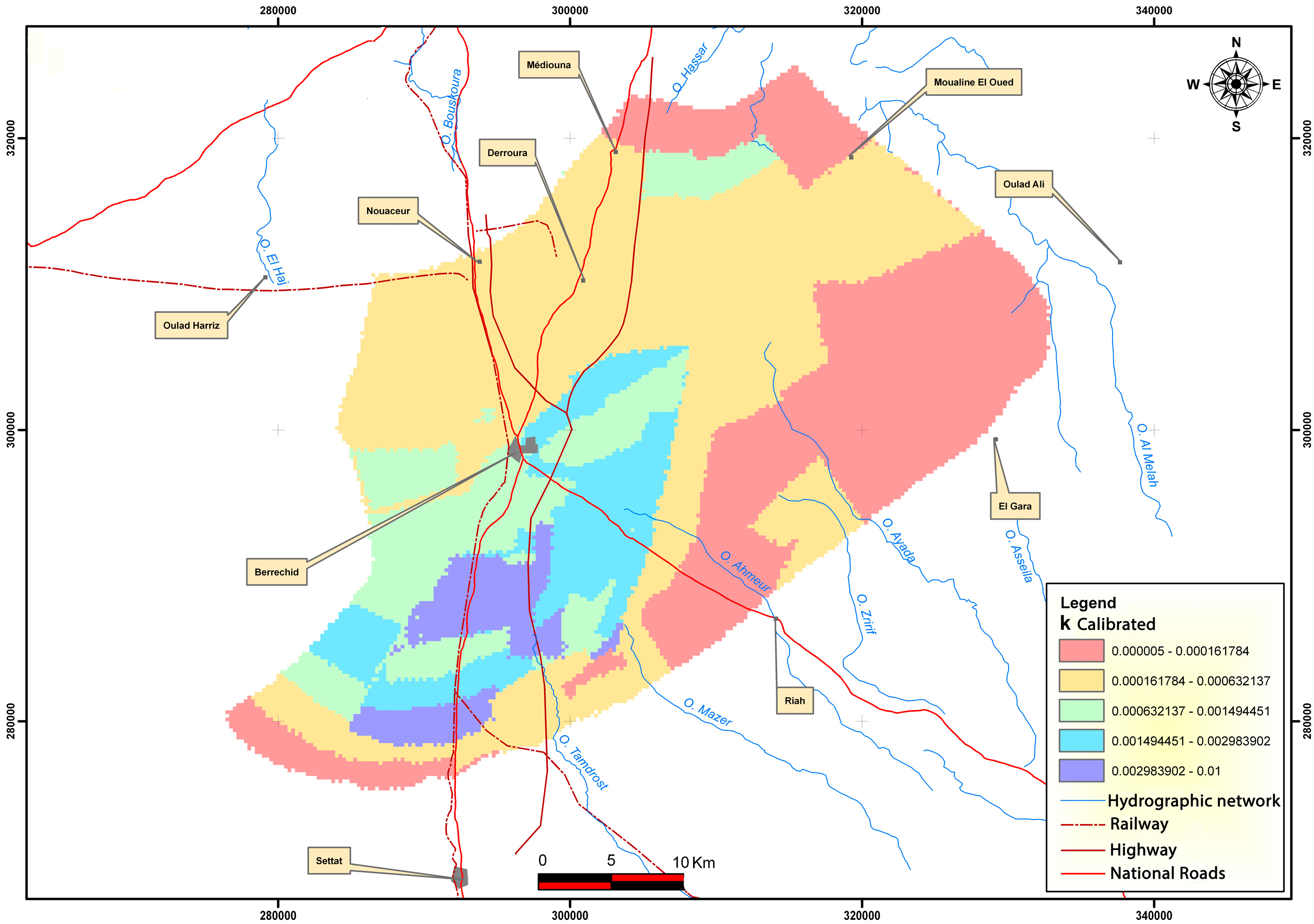

Calibration of hydraulic conductivity produced the permeability distribution shown in

Figure 11, revealing four distinct hydrogeological zones: (i) very low permeability (<10

−4 m/s) in the southern sector, corresponding to thin sandstone fringes with high hydraulic gradients; (ii) relatively high values (>10

−3 m/s) in the west and southwest; (iii) exceptionally high permeability (>10

−2 m/s) associated with coarse channel-fill deposits; and (iv) intermediate values ranging from 10

−4 to 10

−3 m/s across the remaining areas.

The simulated water balance reproduces the hydrogeological conditions described in the 1980 synthesis, with discrepancies between the conceptual model and numerical results remaining below 1.2 Mm

3 (

Table 4).

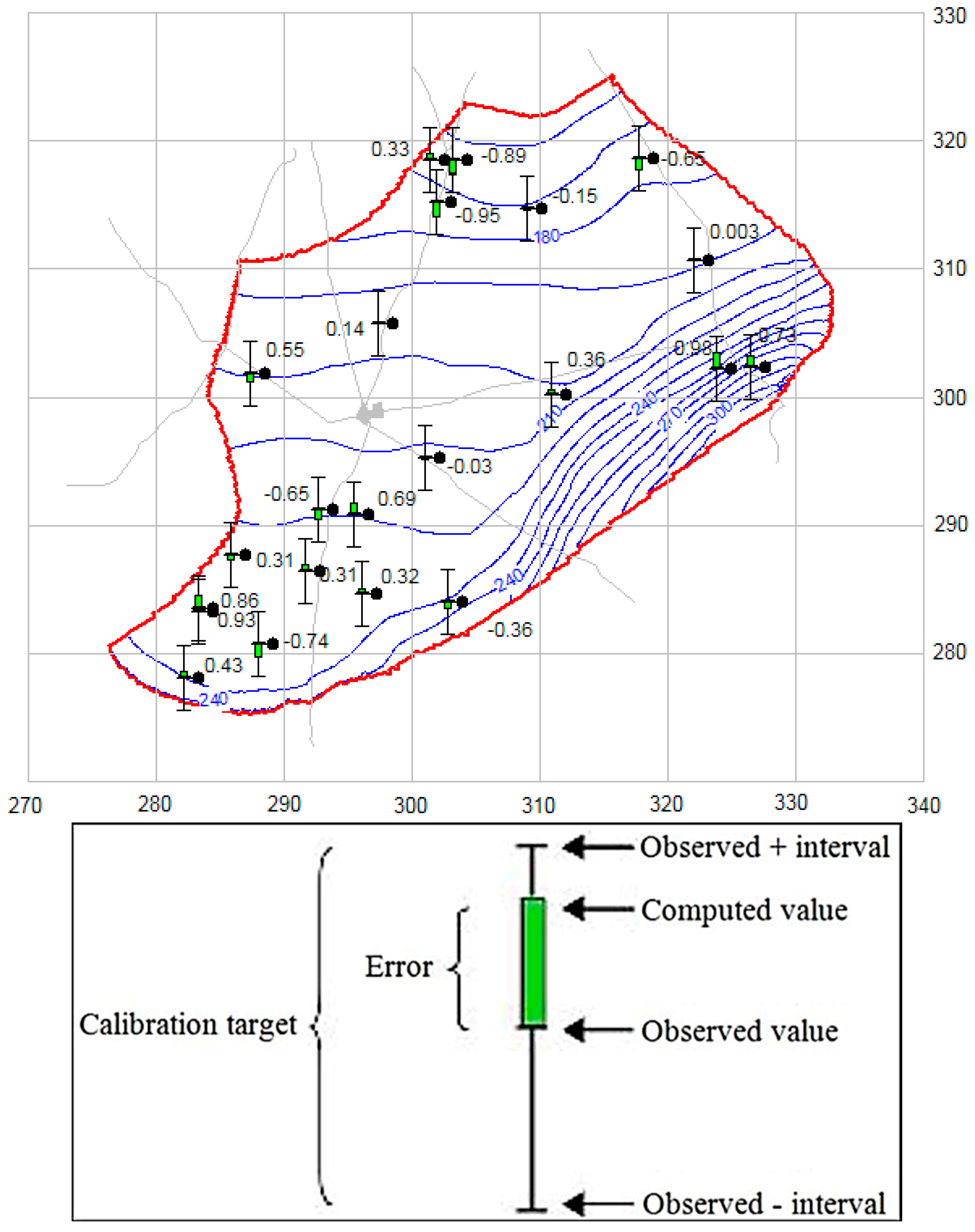

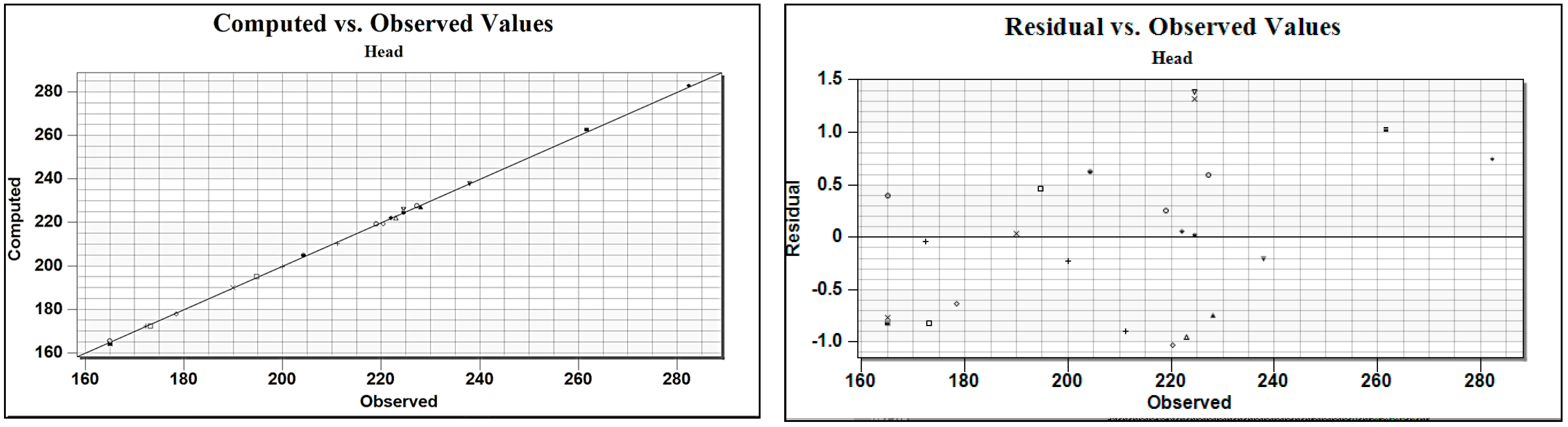

Figure 12 presents the observed and simulated heads along with the calculated residuals. With residuals generally below 1.5 m, the steady-state model demonstrates a high degree of reliability for representing baseline conditions.

Transient modeling represents a continuation of the steady-state calibration process. The primary objective of this stage of hydrodynamic modeling is to calibrate the storage coefficient and homogenize aquifer system data under transient conditions. The selected simulation period spans 31 years, subdivided into annual intervals. Inputs and withdrawals in the Berrechid aquifer were incorporated into the model for each period, and calibration relied on piezometric data from long-time series observation points in the existing monitoring network of observation wells.

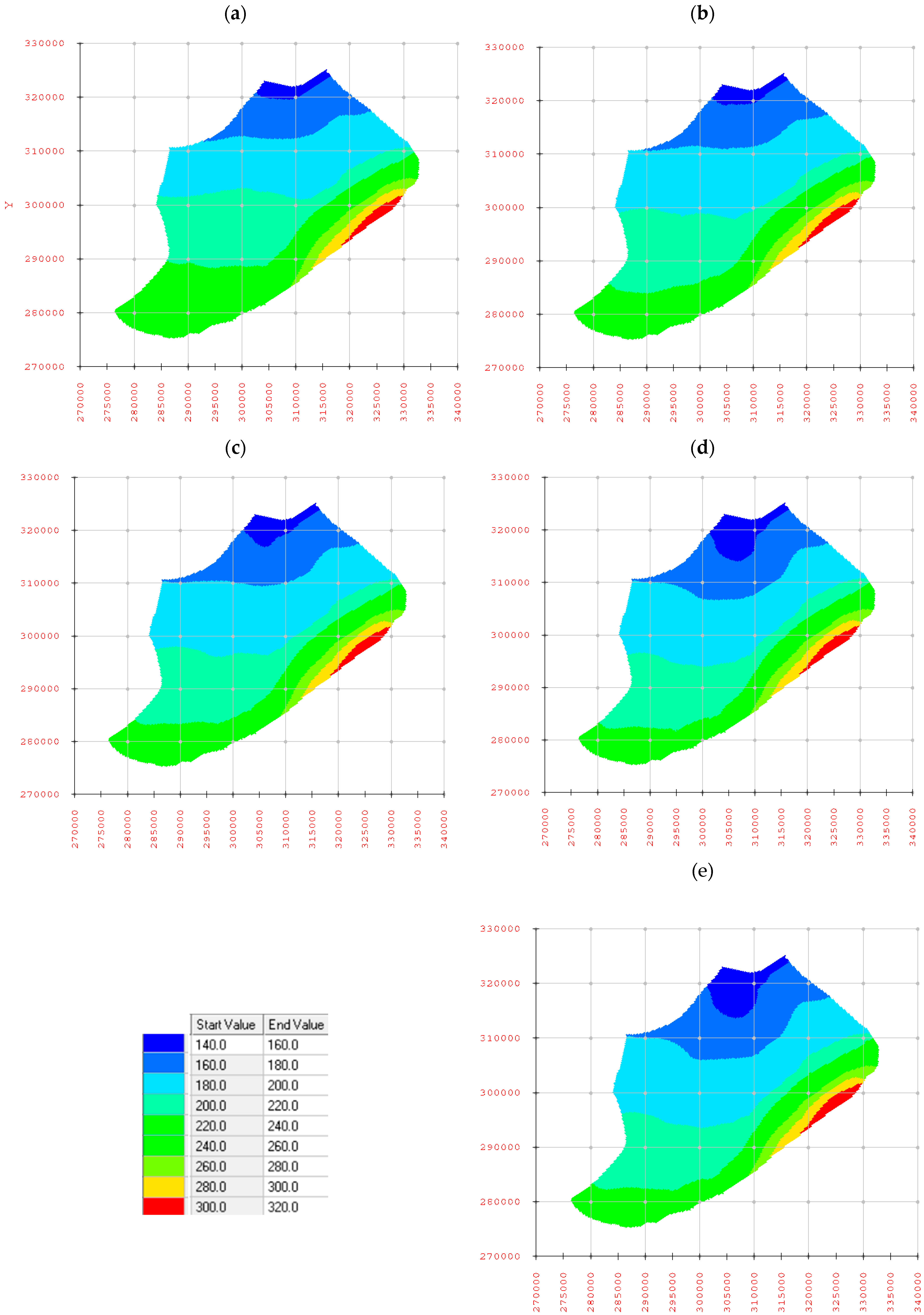

Piezometric surveys conducted every five years between 1980 and 2022 (

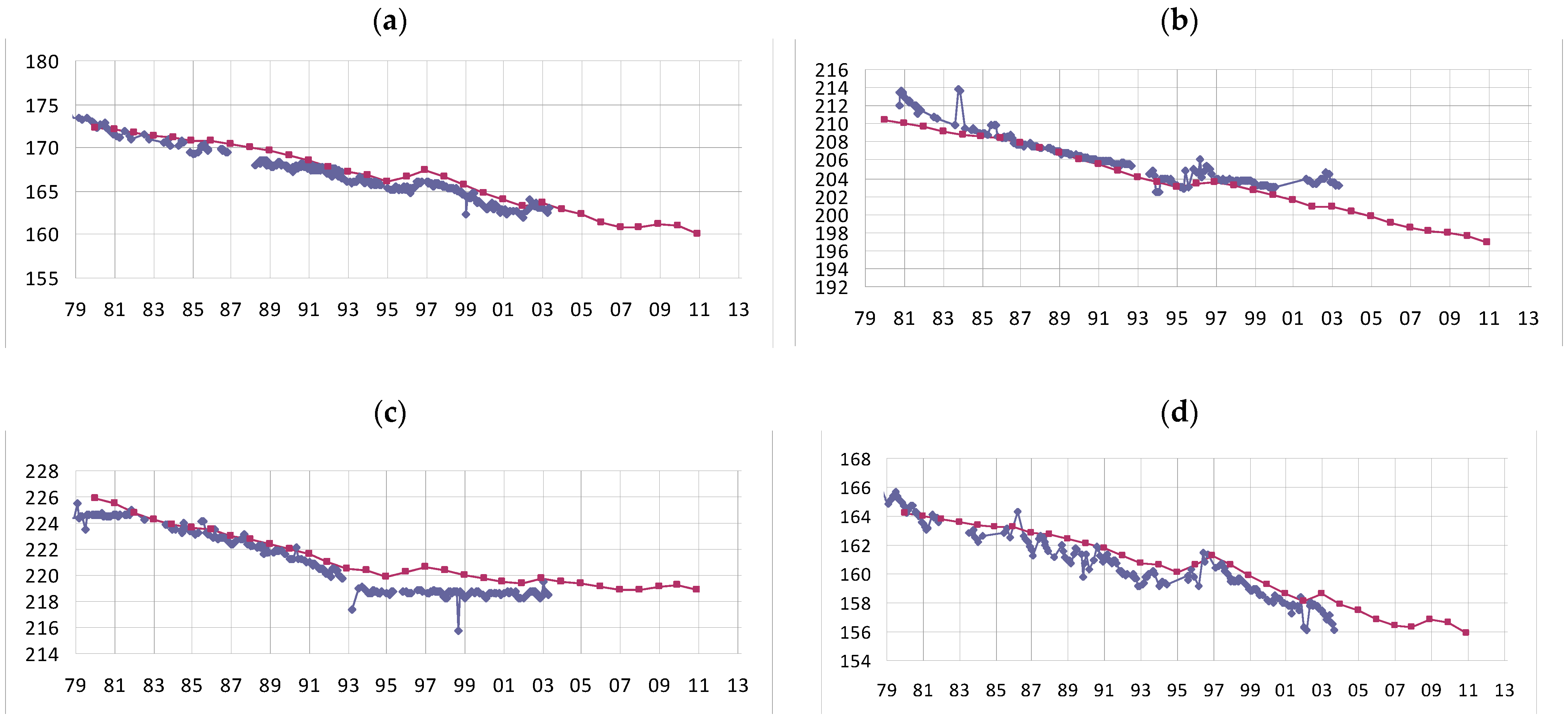

Figure 13) revealed clear evidence of progressive groundwater decline throughout the aquifer. Over time, the drawdown expanded in spatial extent and magnitude, reflected by the migration and widening of piezometric contours. For example, the 223–212 m elevation interval mapped in 2000 was reduced to 212–201 m by 2016, indicating accelerated depletion. This continuous decline is primarily linked to increased groundwater abstraction driven by population growth, agricultural intensification, and evolving climatic conditions. Piezometric records (

Figure 14) comparing simulated and observed groundwater levels further confirm the accuracy of the model, with deviations remaining minor and only slightly increasing after 1990, likely coinciding with elevated anthropogenic pressure on the resource.

Groundwater balance outputs, combined with the piezometric variation maps at the end of the transient simulation, indicate widespread aquifer depletion, particularly in central zones characterized by intensive extraction. The simulation results estimate an average drawdown rate of approximately 2 m/year, demonstrating a persistent long-term decline in groundwater levels. Water balance analyses show that inflows have remained relatively stable, while outflows have increased significantly, reflecting intensified pumping (

Figure 15) and reduced natural recharge. The aquifer maintained a positive storage balance only until 1996; afterward, storage progressively declined, indicating a long-term transition toward unsustainable extraction. If current conditions continue, model projections suggest that groundwater reserves could reach a critical depletion threshold around 2050.

The final calibrated storage coefficient distribution reflects substantial spatial variability linked to aquifer heterogeneity. Specific yield values range from 2.5% to 20% in unconfined areas, while confined zones exhibit values between 0.0025% and 0.5%. These contrasts align with field evidence and lithological interpretations, confirming the structural complexity of the system.

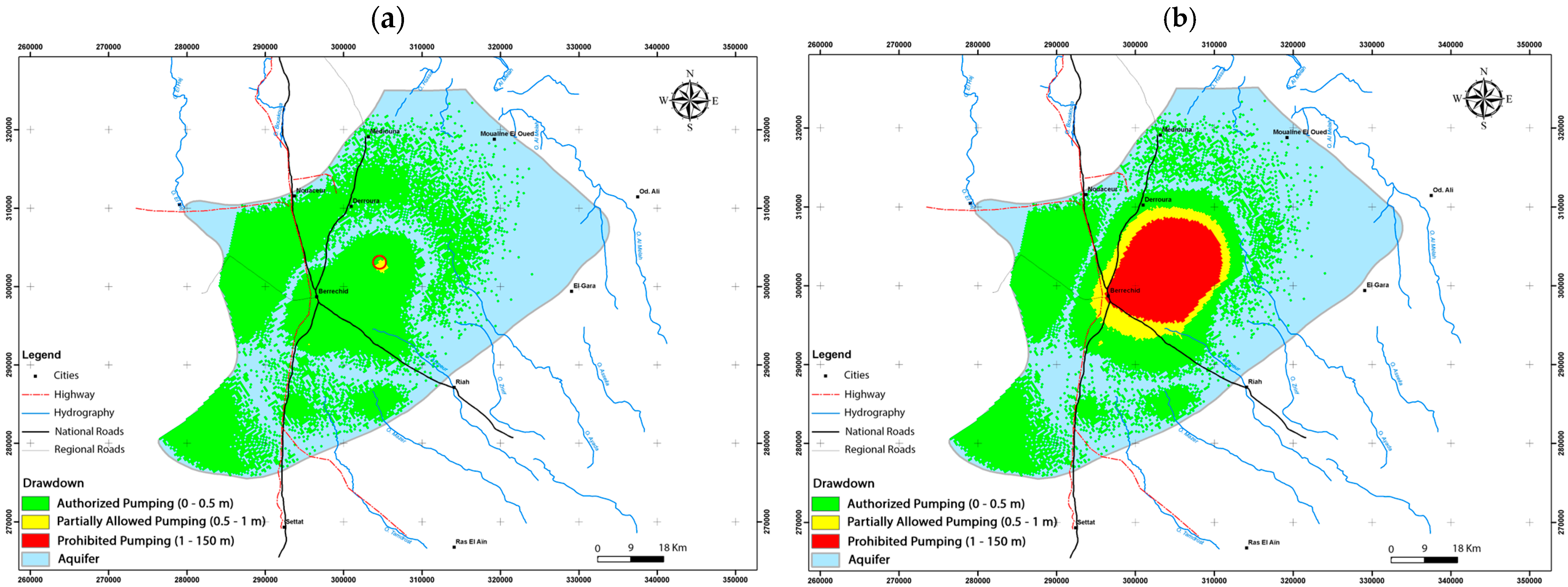

Overall, the calculated piezometric values closely match those measured at control observation wells, indicating satisfactory calibration results. The global piezometric variation map illustrates a general decline in the water table, reflecting reduced reserves attributed to drought and pumping activities. This requires the necessity of developing a withdrawal management tool to act directly at the user level and promote groundwater protection against overexploitation. The groundwater withdrawal management tool developed for the Berrechid aquifer, as demonstrated by Zerouali-A. et al. [

22], utilizes ArcGIS 9.3–MODFLOW/GMS 6.5 coupling to assess and optimize extraction scenarios. This integrated framework enables the calculation of drawdown resulting from pumping activities at specific locations or designated zones and ensures its spatial visualization. The tool produces a decision-support cartographic map of groundwater drawdown, clearly identifying areas where withdrawals are authorized, restricted, or prohibited across the study area.

The analysis demonstrates that a withdrawal rate of approximately 1.5 Mm3/year represents the upper limit of sustainable groundwater extraction. Sensitivity tests further show that any increase above this threshold (i.e., beyond 50 L/s, equivalent to 1.5 Mm3/year) would accelerate groundwater level decline and compromise the long-term viability of the resource, particularly for agricultural and industrial demand. Therefore, extraction volumes exceeding 1.5 Mm3/year are classified as conditionally acceptable, whereas withdrawals greater than 1 m3/s are designated as prohibited due to their critical impact on the aquifer system.

3.1. The Impact of Climate Change on the Berrechid Water Table

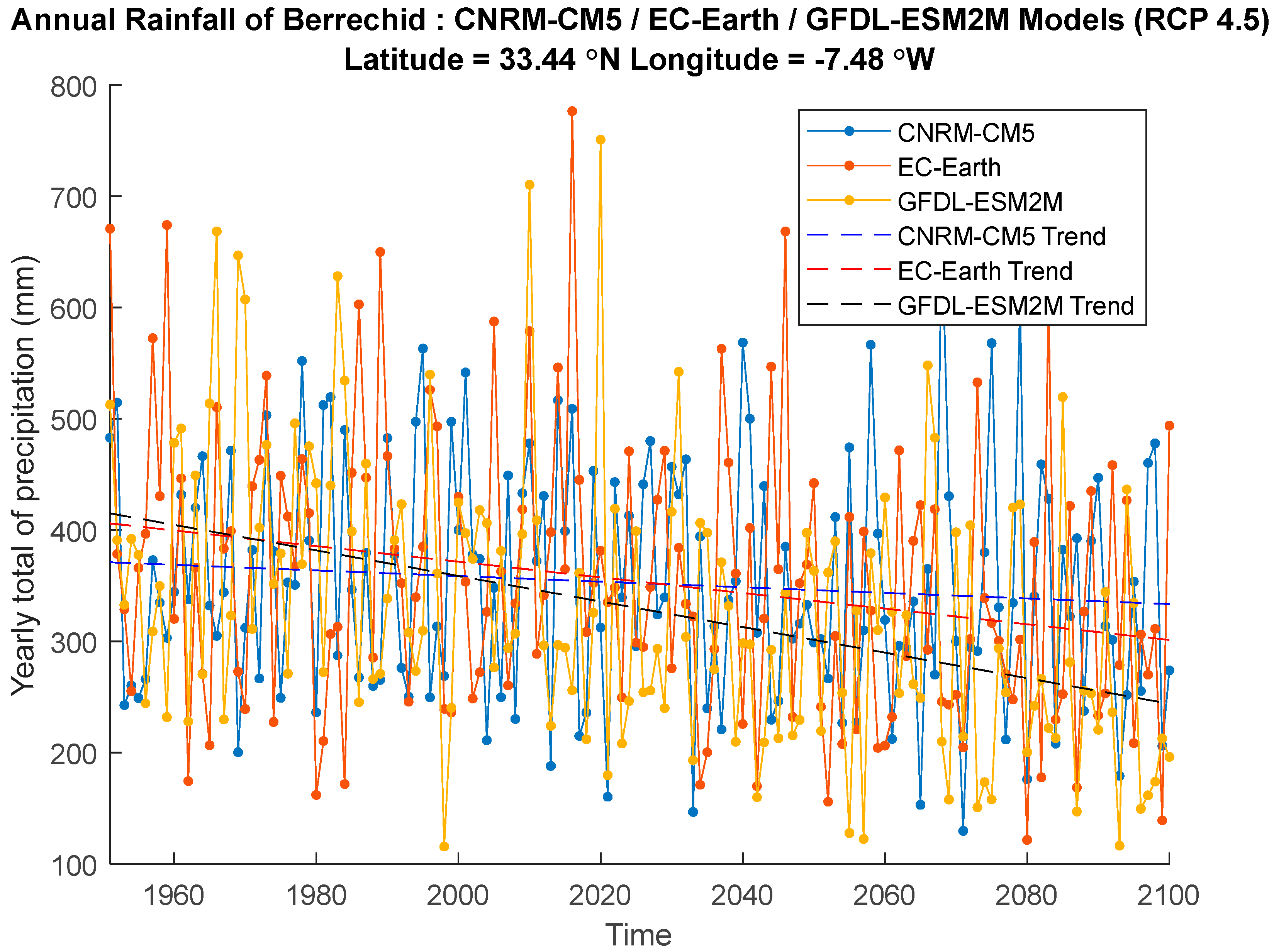

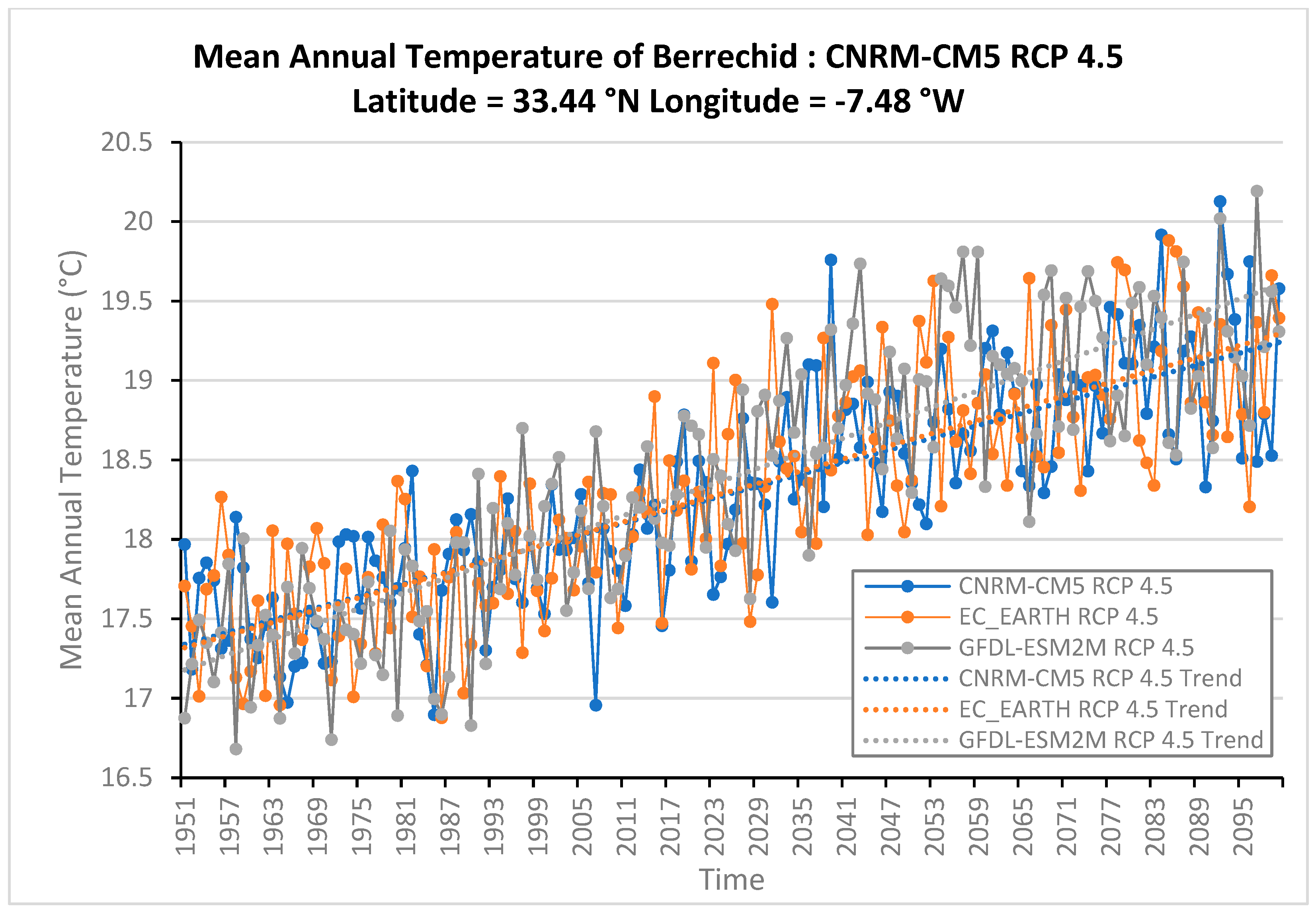

To assess the potential impacts of climate change on the Berrechid aquifer, three Global Climate Models (GCMs)—CNRM-CM5, EC-EARTH, and GFDL-ESM2M—were used under the RCP4.5 scenario. This Representative Concentration Pathway is considered an optimistic trajectory that assumes a gradual stabilization of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and moderate global warming by the end of the 21st century.

The outputs of these models (

Figure 16 and

Figure 17) were used to generate long-term projections of precipitation and temperature for the Berrechid region from 1950 to 2100. These climatic variables are key inputs for estimating future recharge variations and for simulating the hydrodynamic response of the aquifer within the GMS/MODFLOW framework.

The CNRM-CM5 model projects an overall decline in precipitation, mostly ranging between 200 mm and 500 mm, with a maximum of 667 mm in 2068. In contrast, temperature shows a clear upward trend, increasing by about 2 °C between 1950 and 2100, from 16 °C in 1985 to nearly 20 °C in 2092. These results indicate a gradual intensification of aridity, potentially leading to a reduction in effective recharge across the Berrechid Plain.

Under the same RCP4.5 scenario, the EC-EARTH model also predicts a sharp downward trend in precipitation, with a total reduction of approximately 100 mm over the 150-year period. The maximum value is 776 mm in 2016, while the minimum reaches 121 mm in 2080. Meanwhile, temperature increases from 17.25 °C to 19.25 °C (maximum 19.8 °C in 2085), confirming a consistent warming pattern similar to that found in CNRM-CM5 projections.

The GFDL-ESM2M model also indicates a progressive decrease in precipitation by roughly 100 mm throughout the study period. Precipitation peaks are observed in 2010 (710 mm) and 2020 (750 mm), followed by a minimum of 115 mm in 1998. Simultaneously, temperature increases from 17.25 °C to 19.5 °C, reaching a maximum of 20 °C in 2097.

Overall, the three climate models converge on two consistent findings: a declining precipitation trend, indicating a potential reduction in groundwater recharge, and a steady temperature increase of about 1.5–2 °C by 2100, which is expected to intensify evapotranspiration and consequently place greater stress on the Berrechid aquifer’s water resources.

These projected climatic changes were incorporated into the transient simulations of the Berrechid aquifer to quantify their influence on future groundwater levels and assess the system’s vulnerability under the RCP4.5 scenario.

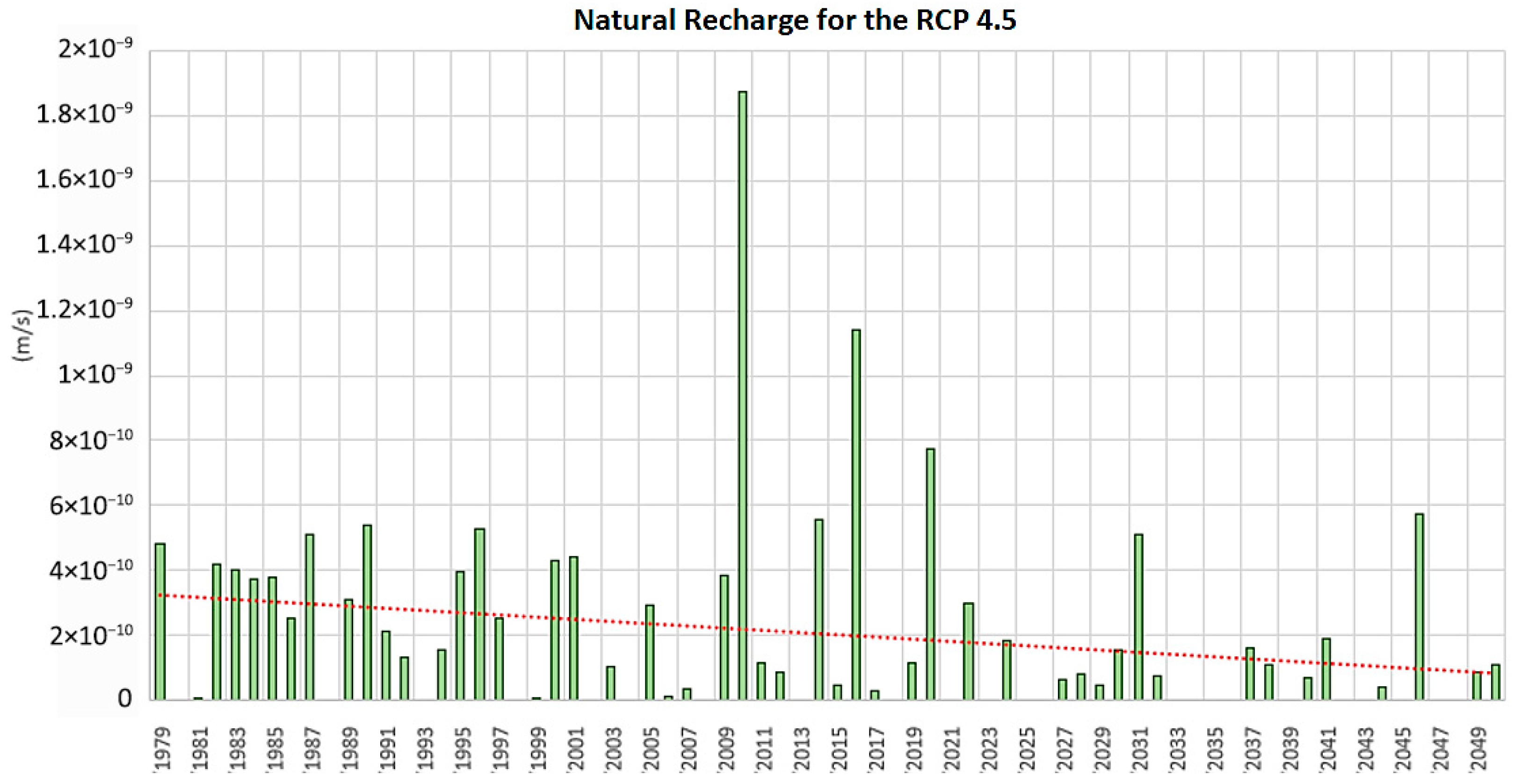

3.2. The Impact of Climate Change on Natural Recharge

To better assess the impact of climate change on natural recharge, we performed calculations to determine average natural recharge scenarios, considering an optimistic projection (

Figure 18).

The figure illustrates the evolution of natural recharge between 1979 and 2050, showing a downward trend. Notably, the year 2010 stands out with the highest recharge value, attributable to particularly humid weather conditions. The diagram also highlights variations in natural recharge between 2022 and 2050, with a wet year projected in 2046, showing the highest recharge value of the period.

The precipitation variation graphs describe forecasts over a 150-year period. The horizontal axis represents time, while the vertical axis represents the amount of precipitation (mm). Interpretation of these graphs shows that, while precipitation remains relatively uniform on average, notable fluctuations occur. The maximum value reaches 800 mm, while the minimum drops to 100 mm, underlining both the magnitude of these variations and the relative stability of long-term averages.

The temperature variation graphs reflect an optimistic scenario of gradual warming, despite significant fluctuations. According to the data, the maximum temperature reaches 20 °C, while the minimum is 16.5 °C. The upward trajectory of temperature is consistent with climate change, which is characterized by a progressive rise in average global temperatures over time.

After a detailed analysis of precipitation and temperature under this scenario, it is clear that the natural recharge of the Berrechid aquifer is strongly influenced by climate variability. The observed downward trend in recharge is largely driven by reduced precipitation.

Having modeled the Berrechid aquifer under both steady-state and transient conditions up to 2022, our focus now shifts to forecasting its future dynamics and evaluating the potential impacts of climate change on groundwater. To achieve this, we integrated precipitation forecast data from three different climate models—CNRM-CM5, EC-EARTH, and GFDL-ESM2M—under the RCP4.5 scenario. This integration enables the simulation of future aquifer behavior and the analysis of its evolution in response to climatic variations.

For the simulation of climate change impacts on the Berrechid aquifer, all variables were held constant except for precipitation, which was adjusted according to forecasts from 2023 to 2050. The average RCP4.5 values from the three models (CNRM-CM5, EC-EARTH, and GFDL-ESM2M) were used to establish the input data for this analysis.

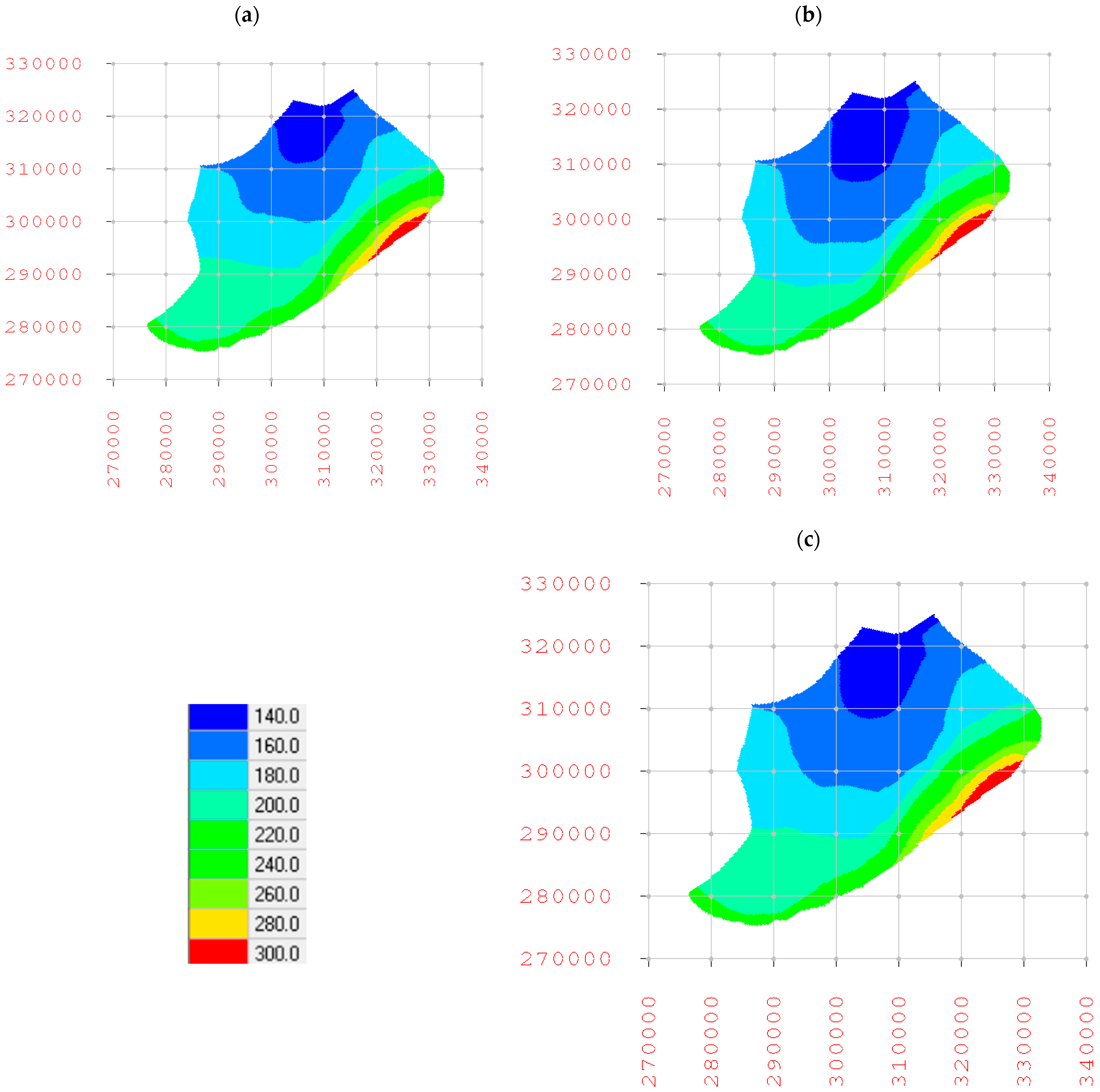

3.3. Model Results for the RCP4.5 Scenario

The results obtained under the RCP4.5 scenario highlight a remarkable stability of groundwater levels throughout the projection period from 2023 to 2050 (

Figure 19). This key finding emerges as one of the most significant outcomes of the modeling effort. The simulated piezometric levels, derived from three climate models—CNRM-CM5, EC-EARTH, and GFDL-ESM2M—show that groundwater dynamics remain largely unchanged under this optimistic emission scenario.

Based on these results, a constant abstraction rate of approximately 1.45 Mm3/year was selected as the reference management scenario, as it represents the most appropriate and sustainable withdrawal limit for the Berrechid aquifer. This value corresponds to the aquifer’s current average pumping conditions, as confirmed by the water-balance results for well abstractions (0.046 m3/s ≈ 46 L/s), and it remains appropriate under projected climate-change conditions.

This stability of the piezometric surface can be explained by two main factors. First, the assumed constant pumping rate of 1.45 Mm3/year exerts a dominant control over groundwater behavior, likely offsetting the moderate climatic variations projected under RCP4.5. Second, the RCP4.5 scenario itself, which assumes a gradual reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and moderate changes in precipitation and temperature, does not generate sufficiently strong climatic stress to significantly alter groundwater recharge or discharge processes.

Consequently, despite minor fluctuations associated with interannual climate variability and human abstraction, the piezometer measurements indicate that the aquifer maintains overall equilibrium over the 28-year simulation period. This suggests that anthropogenic extraction remains the main driver of the aquifer’s long-term balance, while the moderate effects of climate change under RCP4.5 play a secondary role.

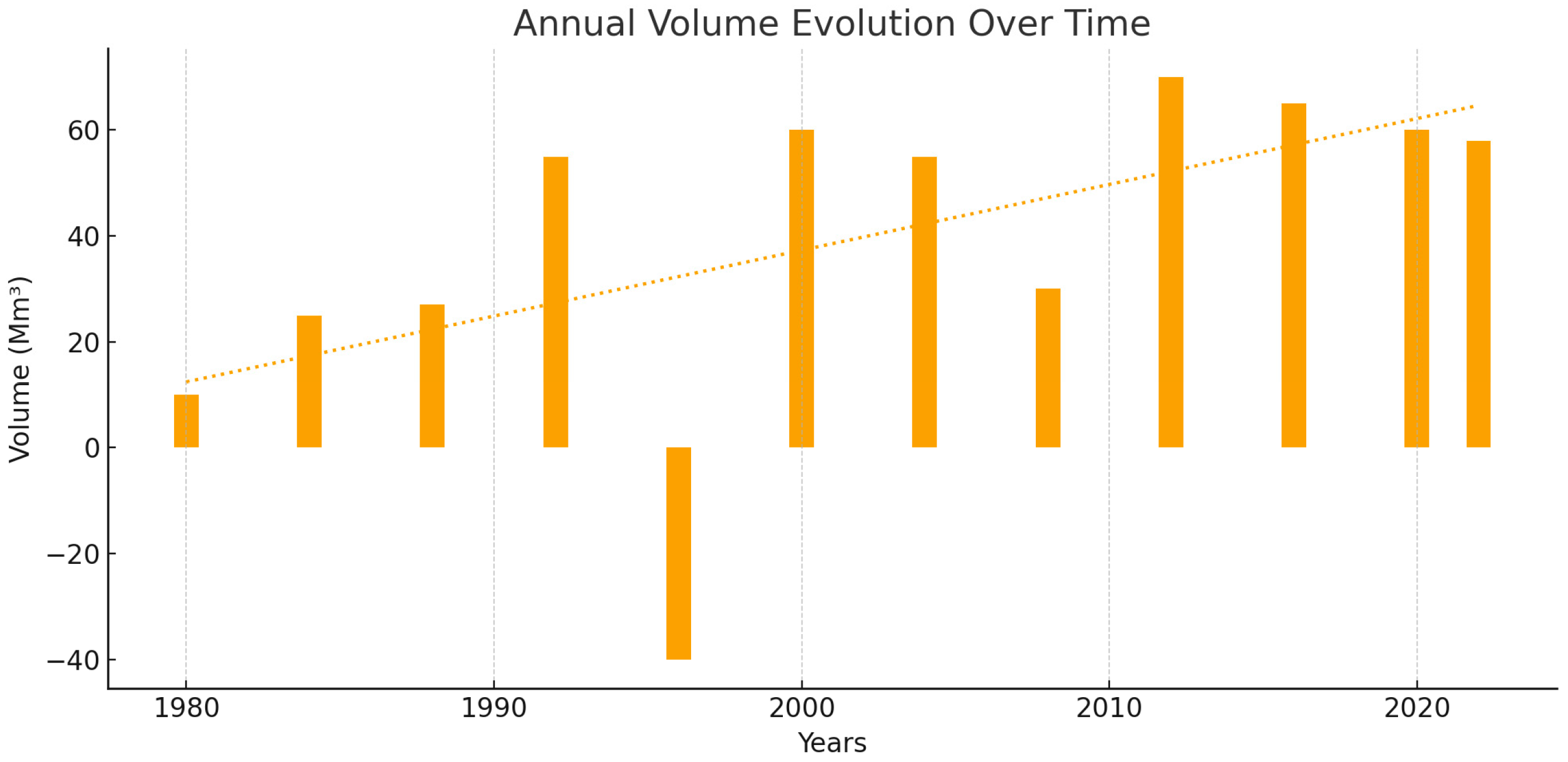

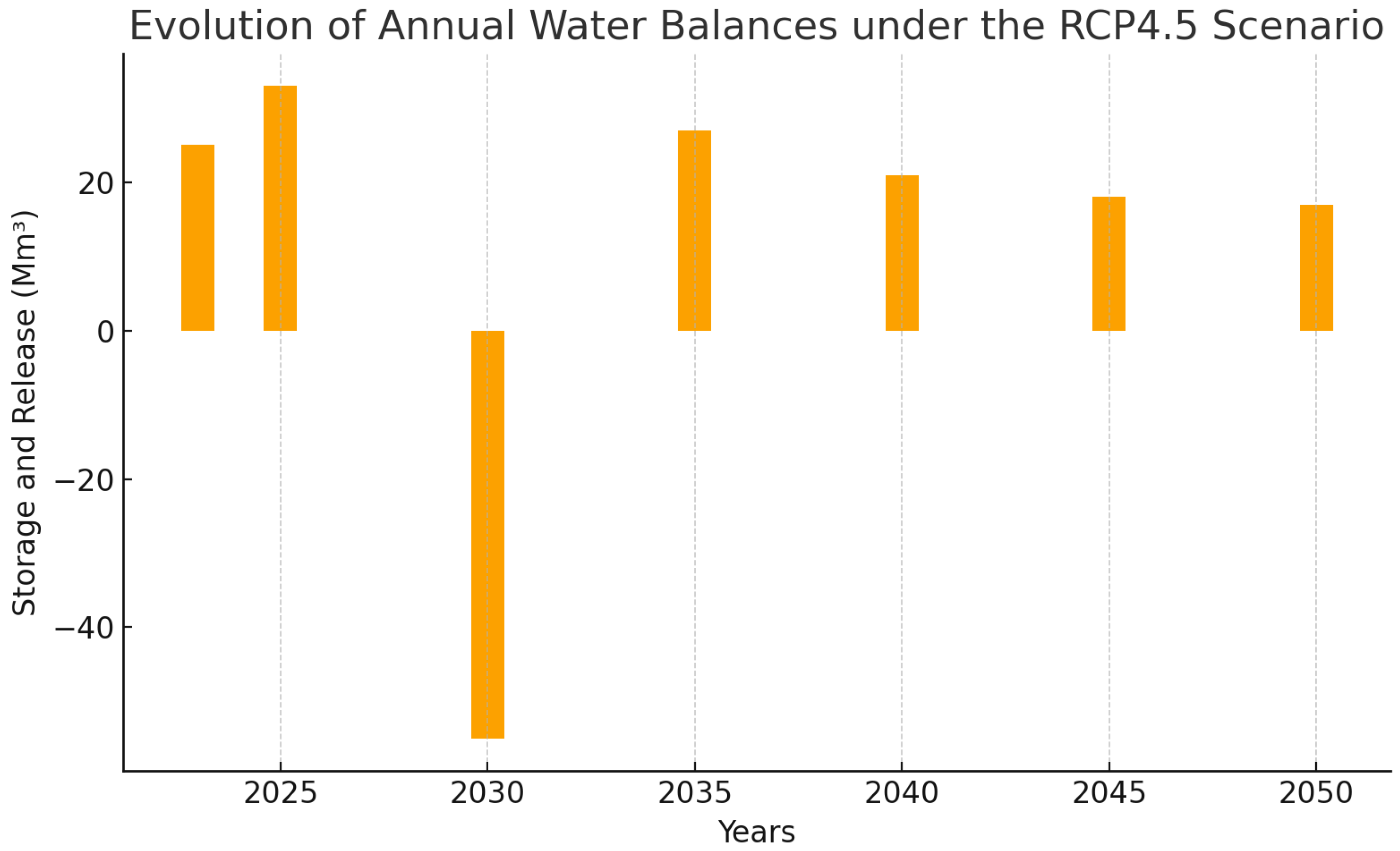

The annual evolution of the groundwater system is summarized in

Table 5, with

Figure 20 illustrating the changes in storage and depletion balances between 2023 and 2050. The analysis confirms that storage remains relatively stable across the study period, except for the year 2030, which exhibits a significant deficit of 55 Mm

3/year—the largest imbalance observed. This temporary reduction may result from a combination of reduced recharge and sustained abstraction during that period; however, it is not expected to affect the subsequent years, as recharge conditions improve and the system gradually returns to equilibrium.

In summary, the RCP 4.5 scenario leads to relatively minor long-term impacts on groundwater levels. This is mainly because maintaining a regulated and constant pumping rate does not strongly influence aquifer behavior under the moderate climatic fluctuations projected for this scenario.

Although the modeling framework provides valuable insights into the future behavior of the Berrechid aquifer under the RCP4.5 scenario, several limitations must be acknowledged to properly frame the interpretation of the results.

Recharge was estimated using the Thornthwaite method for potential evapotranspiration and a simple percentage (15–20%) of annual precipitation, an approach that may underestimate the nonlinear effects of soil moisture deficits, land-use changes, or intensified extreme events.

Data limitations also exist. Boundary conditions, particularly lateral inflows from the Settat Plateau and outflows toward the Chaouia coastal aquifer, rely on simplified general-head or specified-head representations that may not fully capture dynamic interactions during extreme wet or dry years.

Finally, the use of only three GCMs (CNRM-CM5, EC-EARTH, GFDL-ESM2M) under a single intermediate scenario (RCP4.5) limits the range of explored uncertainty; higher-emission pathways (e.g., RCP8.5) or a wider GCM ensemble could reveal greater vulnerability.

Despite these constraints, the projected stability (or only minor, temporary deficits) of groundwater levels when pumping is maintained at sustainable levels aligns with several regional studies. Earlier assessments by ABHBC [5, 6] and DRPE [

10] documented severe historical depletion (average ~2 m/year) driven predominantly by overexploitation rather than climatic trends alone, a conclusion supported by our transient calibration for 1980–2022. In the coastal Chaouia aquifer, modeled recharge reductions of 20–40% by 2050 under higher-emission scenarios led to significant water-table decline when pumping was not curtailed [

23]. In contrast, our results under the optimistic RCP4.5 pathway and regulated abstraction resemble findings from the Haouz plain (central Morocco), where strict pumping controls were shown to largely offset projected recharge declines of 10–25% [

28]. The relatively muted climate signal observed here, compared with stronger depletion projected in North African aquifers under unconstrained abstraction (Kastali et al. [

4], in the Mitidja plain, Algeria), reinforces the conclusion that, in the Berrechid system, anthropogenic withdrawal remains the primary driver of long-term aquifer health, at least until mid-century and under moderate warming.

These limitations and comparisons highlight the need for continued model refinement—incorporating higher-resolution downscaled climate data, dynamic pumping scenarios, and coupled surface–groundwater processes—as well as expanded monitoring networks to reduce parameter uncertainty in future assessments.

4. Conclusions

Climate change is a major global concern, and its effects are already evident in recurring droughts, irregular precipitation, and extreme weather events. Groundwater resources are directly affected by these changes.

For the Berrechid aquifer, simulations under the RCP4.5 scenario indicate that, despite moderate climatic variations, groundwater levels remain largely stable between 2023 and 2050. The relative stability of the piezometric surface can be attributed to the adoption of a constant abstraction rate of approximately 1.45 Mm3/year, which represents an appropriate and realistic reference management scenario for the aquifer. This pumping level reflects future average withdrawal conditions and remains below the threshold that would induce significant drawdown. As a result, it helps maintain hydraulic equilibrium and prevents further degradation of groundwater levels, thereby supporting more sustainable long-term aquifer behavior under existing hydroclimatic pressures.

Although the aquifer remains relatively stable under the RCP4.5 scenario, proactive and adaptive management is essential to ensure its long-term sustainability, particularly given potential increases in agricultural, domestic, and industrial demand. Priority actions include improving water-use efficiency and diversifying water supply through treated wastewater reuse, rainwater harvesting, and desalination. Considering projected population growth and the associated rise in regional water demand, part of the future needs is expected to be met by a planned desalination plant, which will help reduce pressure on the aquifer and support a more balanced groundwater-management approach under climate-change conditions.

Reinforcing monitoring systems to track groundwater levels, water quality, and aquifer responses to climatic variability is also crucial. Additional measures involve enhancing community awareness, strengthening institutional coordination, adopting integrated long-term planning, and supporting research and innovation to optimize water-management technologies.

In conclusion, while no major depletion is anticipated in the near future under the RCP4.5 scenario, implementing these strategies is vital to ensure resilience and safeguard groundwater resources for future generations.