Unravelling Metabolic Pathways and Evaluating Process Performances in Anaerobic Digestion of Livestock Manures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inoculum and Feedstock Collection

2.2. Reactor Operation

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.4. Whole Genome Shotgun Sequencing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Long-Term Performance

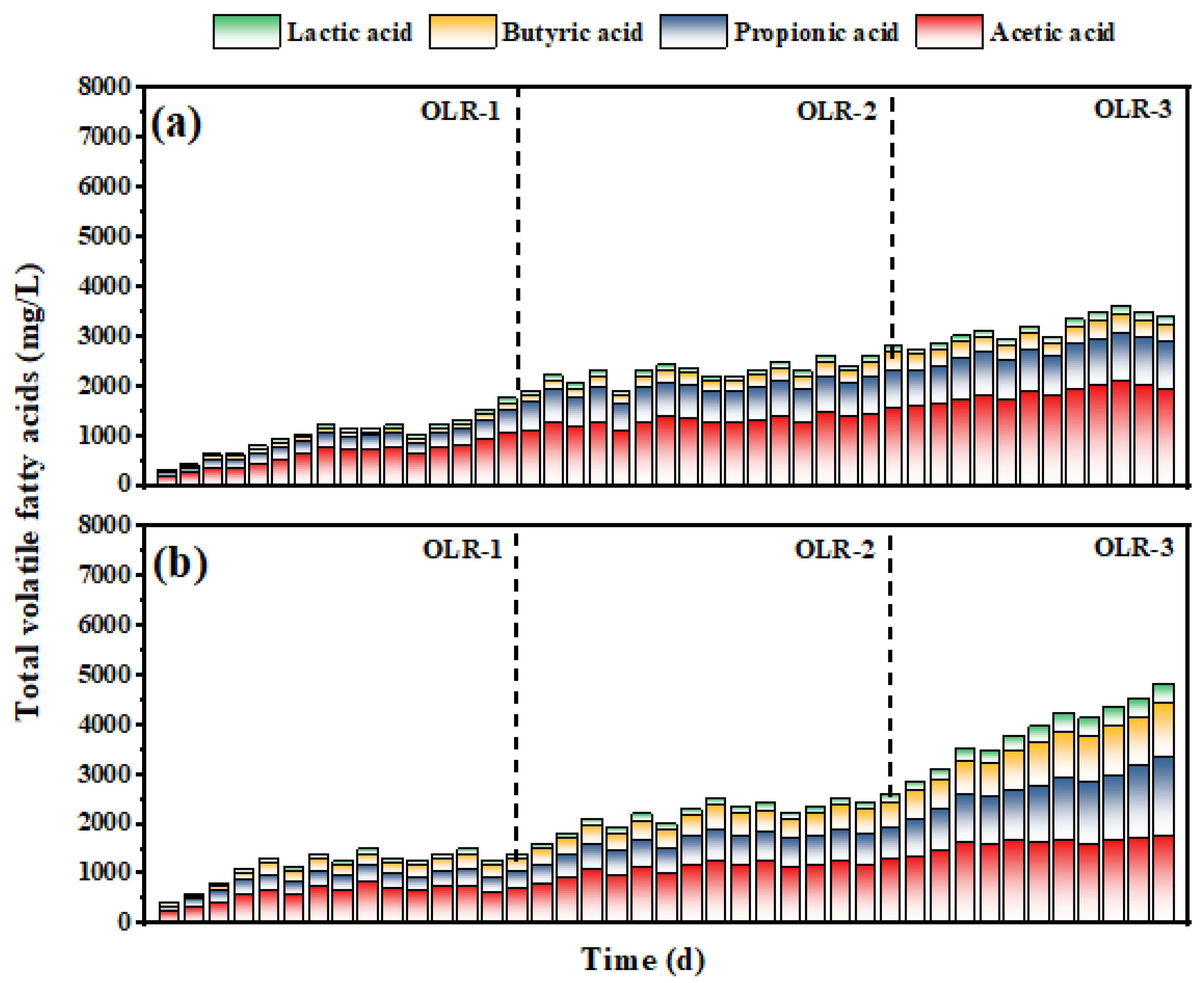

3.2. Changes in Total Volatile Fatty Acids

3.3. Changes in Fiber (Cellulose, Hemicellulose and Lignin), Carbohydrate, Protein and Lipid

3.4. Microbial Community Structure

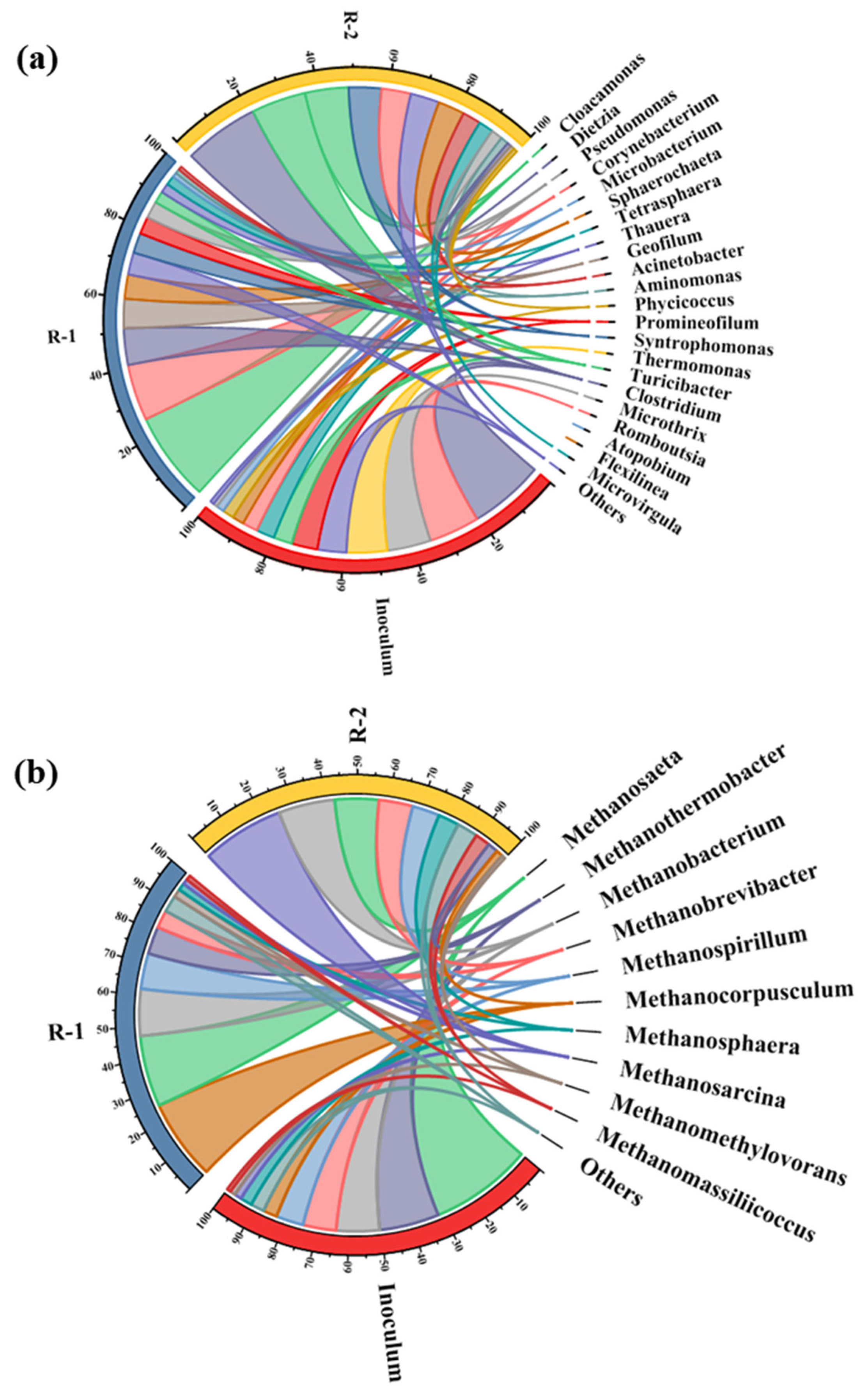

3.4.1. Bacterial and Archaeal Community Structure

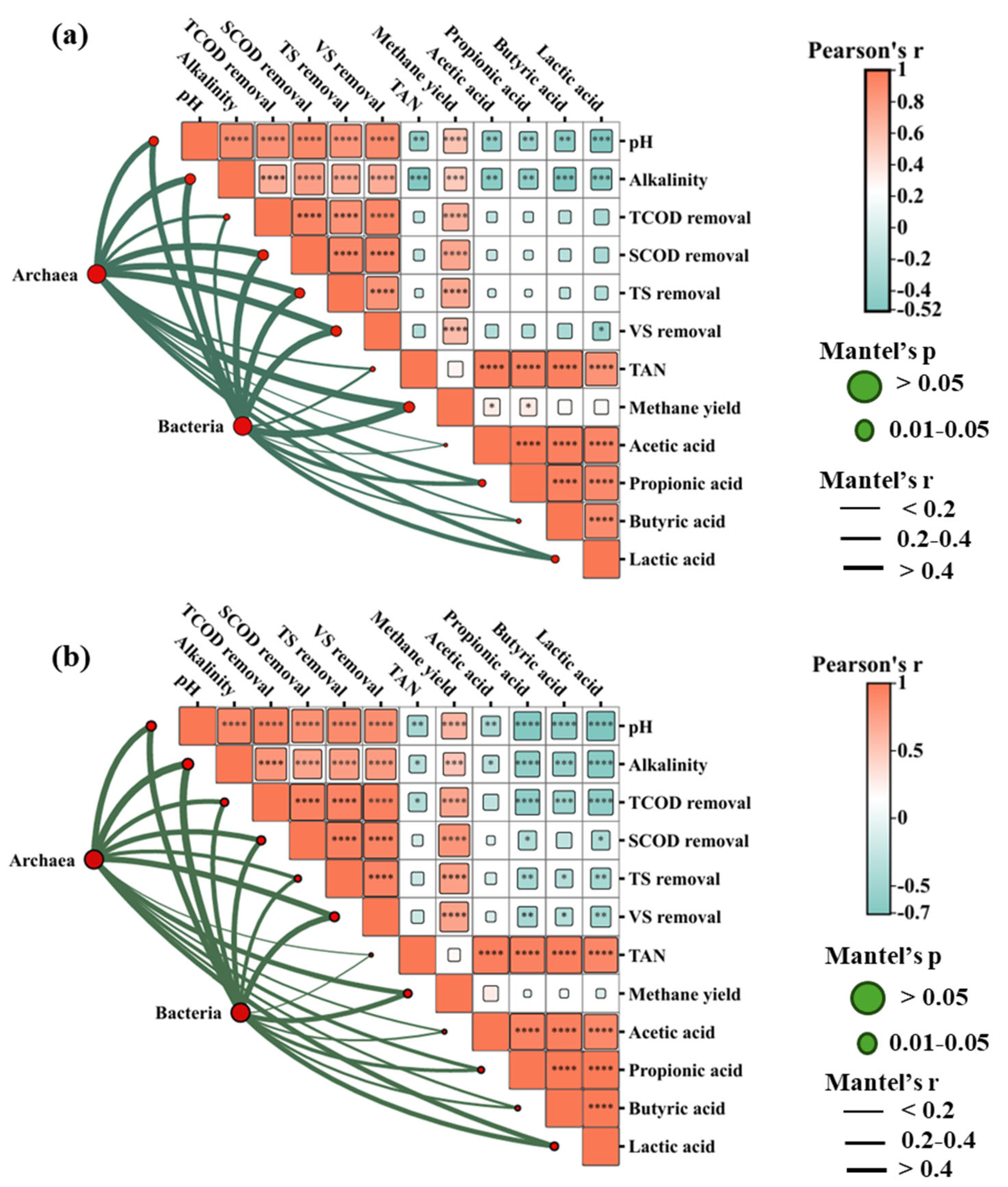

3.4.2. Pearson Correlation and Mantel Test Analysis Between Bacteria and Archaea with Physiochemical Parameters

3.5. Functional Enzymes and Metabolic Pathways

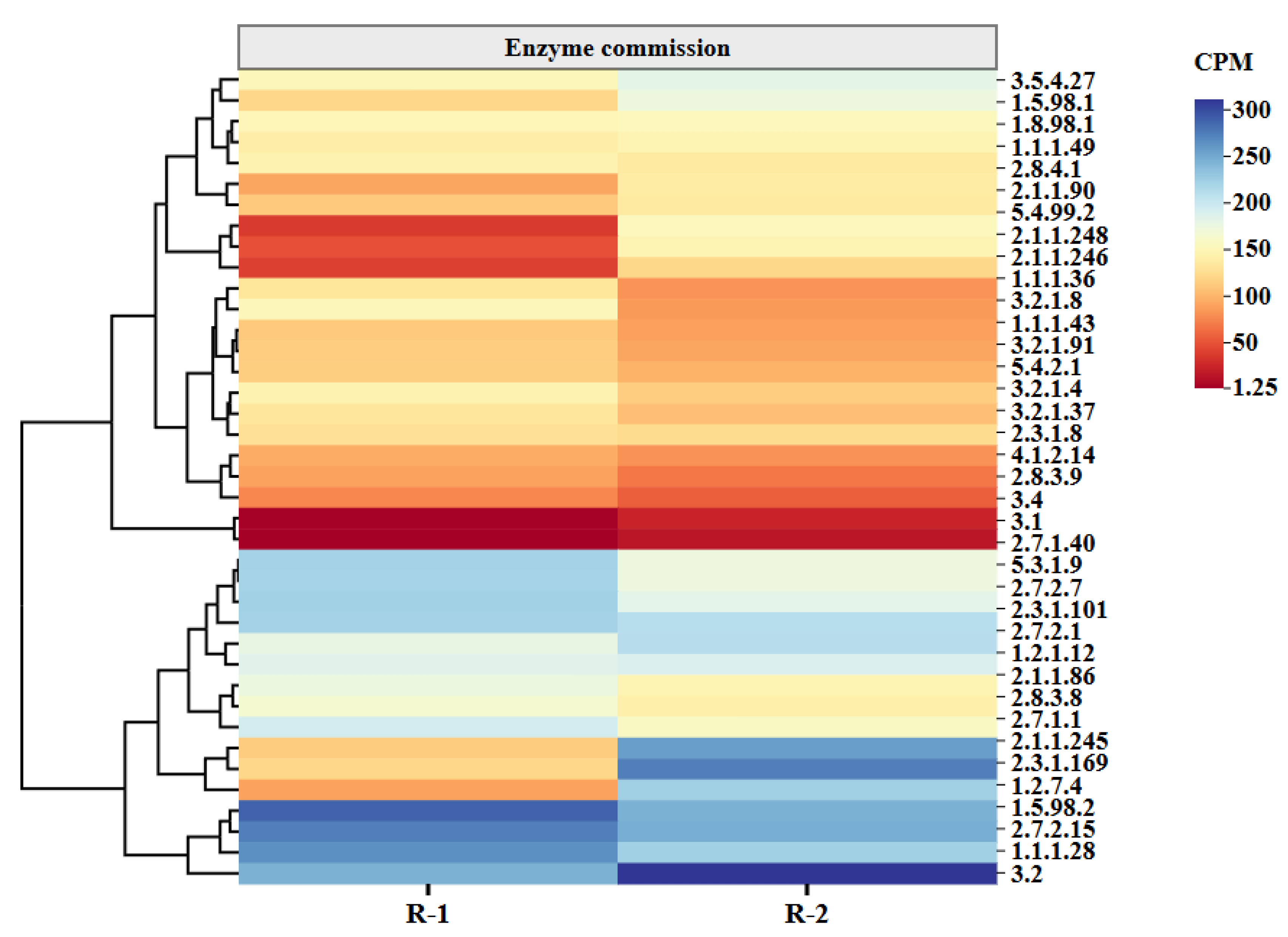

3.5.1. Functional Enzymes

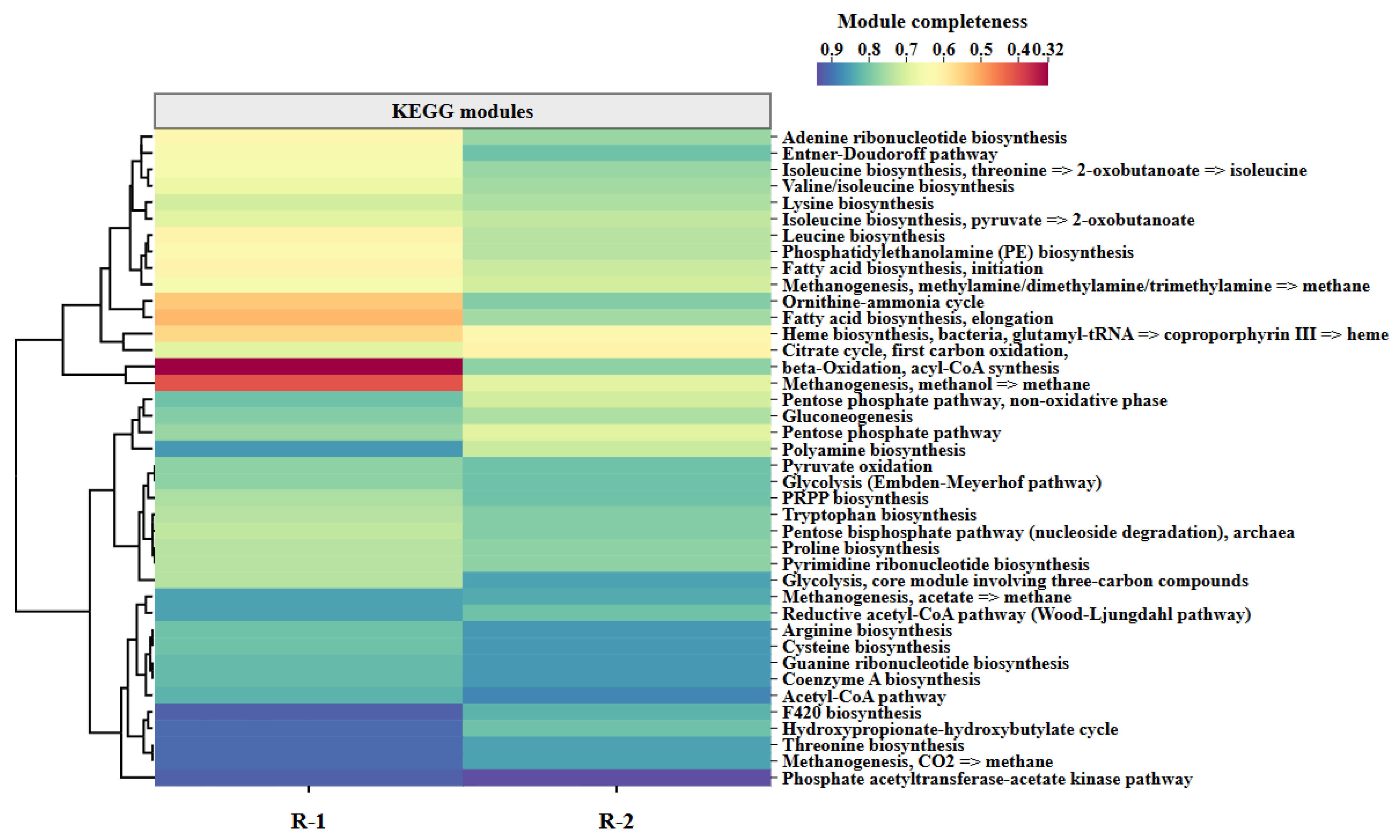

3.5.2. Metabolic Pathway Reconstruction

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Kadam, R.; Jo, S.; Lee, J.; Khanthong, K.; Jang, H.; Park, J. A review on the anaerobic co-digestion of livestock manures in the context of sustainable waste management. Energies 2024, 17, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Bae, J.; Kadam, R.; Lee, J.; Park, J.; Jun, H. Enhanced anaerobic co-digestion of cattle manure with food waste and pig manure: Statistical optimization of pretreatment condition and substrate mixture ratio. Waste Manag. 2024, 183, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, S.; Yoon, Y.; Hamid, M.M.A.; Reza, A.; Shim, S.; Kim, S.; Ra, C.; Novianty, E.; Park, K.-H. Estimation of greenhouse gas emission from Hanwoo (Korean native cattle) manure management systems. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Krooneman, J.; Euverink, G.J.W. Strategies to boost anaerobic digestion performance of cow manure: Laboratory achievements and their full-scale application potential. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, L.; Ho, G. Mitigating ammonia inhibition of thermophilic anaerobic treatment of digested piggery wastewater: Use of pH reduction, zeolite, biomass and humic acid. Water Res. 2012, 46, 4339–4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saady, N.M.C.; Massé, D.I. Impact of organic loading rate on the performance of psychrophilic dry anaerobic digestion of dairy manure and wheat straw: Long-term operation. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 182, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, N.; Zhang, D.; Lin, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, Z. Effect of organic loading rate on anaerobic digestion of pig manure: Methane production, mass flow, reactor scale and heating scenarios. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 231, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, B.; Tian, D.; Jun, H. Bioelectrochemical enhancement of methane production from highly concentrated food waste in a combined anaerobic digester and microbial electrolysis cell. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 247, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Wilkins, D.; Chen, J.; Ng, S.-K.; Lu, H.; Jia, Y.; Lee, P.K. Metagenomic reconstruction of key anaerobic digestion pathways in municipal sludge and industrial wastewater biogas-producing systems. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCola, A.C.; Toppen, L.C.; Brown, K.P.; Dadkhah, A.; Rizzo, D.M.; Ziels, R.M.; Scarborough, M.J. Microbiome assembly and stability during start-up of a full-scale, two-phase anaerobic digester fed cow manure and mixed organic feedstocks. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 394, 130247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.-S.; Zhao, J.-L.; Liu, W.-R.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Q.-Q.; He, L.-Y.; Ying, G.-G. Variations of antibiotic resistome in swine wastewater during full-scale anaerobic digestion treatment. Environ. Int. 2021, 155, 106694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, R.; Jo, S.; Park, J. Importance of substrate mixture ratio optimization on efficient anaerobic co-digestion of organic wastes generated in livestock sector: Insights into process performances and metagenomics. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 441, 133561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioabla, A.E.; Ionel, I.; Dumitrel, G.-A.; Popescu, F. Comparative study on factors affecting anaerobic digestion of agricultural vegetal residues. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2012, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Qiao, W.; Westerholm, M.; Zhou, Y.; Dong, R. High rate methanogenesis and nitrogenous component transformation in the high-solids anaerobic digestion of chicken manure enhanced by biogas recirculation ammonia stripping. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuetos, M.; Gómez, X.; Otero, M.; Morán, A. Anaerobic digestion and co-digestion of slaughterhouse waste (SHW): Influence of heat and pressure pre-treatment in biogas yield. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 1780–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Huang, W.; Yuan, T.; Zhao, Z.; Cai, W.; Zhang, Z.; Lei, Z.; Feng, C. Volatile fatty acids (VFAs) production from swine manure through short-term dry anaerobic digestion and its separation from nitrogen and phosphorus resources in the digestate. Water Res. 2016, 90, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsapekos, P.; Kougias, P.; Vasileiou, S.; Treu, L.; Campanaro, S.; Lyberatos, G.; Angelidaki, I. Bioaugmentation with hydrolytic microbes to improve the anaerobic biodegradability of lignocellulosic agricultural residues. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 234, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Zhang, W.; Ren, S.; Liu, F.; Zhao, C.; Liao, H.; Xu, Z.; Huang, J.; Li, Q.; Tu, Y.; et al. Hemicelluloses negatively affect lignocellulose crystallinity for high biomass digestibility under NaOH and H2SO4 pretreatments in Miscanthus. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2012, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Liu, S.; Xin, F.; Zhou, J.; Jia, H.; Xu, J.; Jiang, M.; Dong, W. Biomethane production from lignocellulose: Biomass recalcitrance and its impacts on anaerobic digestion. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamperidou, V.; Terzopoulou, P. Anaerobic digestion of lignocellulosic waste materials. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Ndegwa, P.; Harrison, J.H.; Chen, Y. Methane yields during anaerobic co-digestion of animal manure with other feedstocks: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jin, Y.; Borrion, A.; Li, H.; Li, J. Effects of organic composition on the anaerobic biodegradability of food waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 243, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, C.; Park, S.-G.; Yu, S.I.; Dalantai, T.; Shin, J.; Chae, K.-J.; Shin, S.G. Mapping microbial dynamics in anaerobic digestion system linked with organic composition of substrates: Protein and lipid. Energy 2023, 275, 127411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdalena, J.A.; Greses, S.; González-Fernández, C. Anaerobic degradation of protein-rich biomass in an UASB reactor: Organic loading rate effect on product output and microbial communities dynamics. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 274, 111201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Dang, Y.; Li, C.; Sun, D. Inhibitory effect of high NH4+–N concentration on anaerobic biotreatment of fresh leachate from a municipal solid waste incineration plant. Waste Manag. 2015, 43, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razaviarani, V.; Buchanan, I.D. Anaerobic co-digestion of biodiesel waste glycerin with municipal wastewater sludge: Microbial community structure dynamics and reactor performance. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 182, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breton-Deval, L.; Salinas-Peralta, I.; Alarcón Aguirre, J.S.; Sulbarán-Rangel, B.; Gurubel Tun, K.J. Taxonomic binning approaches and functional characteristics of the microbial community during the anaerobic digestion of hydrolyzed corncob. Energies 2020, 14, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.-M.; Westerholm, M.; Qiao, W.; Bi, S.-J.; Wandera, S.M.; Fan, R.; Jiang, M.-M.; Dong, R.-J. An explanation of the methanogenic pathway for methane production in anaerobic digestion of nitrogen-rich materials under mesophilic and thermophilic conditions. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 264, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Y.; Hou, W.; Bian, C.; Zheng, T.; Xiao, B.; Li, L. Enhancing anaerobic digestion of swine manure using microbial electrolysis cell and microaeration. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 514, 163319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Lu, T.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Shen, P.; Wei, Y. Response and mechanisms of the performance and fate of antibiotic resistance genes to nano-magnetite during anaerobic digestion of swine manure. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 366, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Che, X.; Li, C.; Liang, D.; Zhou, H.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y. Biochar stimulates growth of novel species capable of direct interspecies electron transfer in anaerobic digestion via ethanol-type fermentation. Environ. Res. 2020, 189, 109983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Guo, T.; Chen, Y.; Meng, Q.; Zhu, C.; Huang, H. Physicochemical characteristics of stored cattle manure affect methane emissions by inducing divergence of methanogens that have different interactions with bacteria. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 253, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Achinas, S.; Zhao, J.; Geurkink, B.; Krooneman, J.; Euverink, G.J.W. Co-digestion of cow and sheep manure: Performance evaluation and relative microbial activity. Renew. Energy 2020, 153, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Fan, Q.; Gao, F.; Xia, T.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Guo, X.; Yang, X.; Yao, Y.; Qiu, L.; et al. Sustained methane production enhancement by magnetic biochar and its recovery in semi-continuous anaerobic digestion with varying substrate C/N ratios. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 514, 163050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Niu, X.; Su, X.; He, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, D.; Chen, D.; Lin, Y.; Li, K. Enhancement of methane production from pig manure by ferrate pretreated anaerobic digestion: Performance and mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 515, 163862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Treu, L.; Campanaro, S.; Tian, H.; Zhu, X.; Khoshnevisan, B.; Tsapekos, P.; Angelidaki, I.; Fotidis, I.A. Effect of ammonia on anaerobic digestion of municipal solid waste: Inhibitory performance, bioaugmentation and microbiome functional reconstruction. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 401, 126159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolay, P.; Muro-Pastor, M.I.; Rozbeh, R.; Timm, S.; Hagemann, M.; Florencio, F.J.; Forchhammer, K.; Klähn, S. The novel PII-interacting protein PirA regulates flux into the cyanobacterial ornithine-ammonia cycle. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jun, H.; Kadam, R.; Jo, S.; Park, J. Unravelling Metabolic Pathways and Evaluating Process Performances in Anaerobic Digestion of Livestock Manures. Water 2025, 17, 3464. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243464

Jun H, Kadam R, Jo S, Park J. Unravelling Metabolic Pathways and Evaluating Process Performances in Anaerobic Digestion of Livestock Manures. Water. 2025; 17(24):3464. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243464

Chicago/Turabian StyleJun, Hangbae, Rahul Kadam, Sangyeol Jo, and Jungyu Park. 2025. "Unravelling Metabolic Pathways and Evaluating Process Performances in Anaerobic Digestion of Livestock Manures" Water 17, no. 24: 3464. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243464

APA StyleJun, H., Kadam, R., Jo, S., & Park, J. (2025). Unravelling Metabolic Pathways and Evaluating Process Performances in Anaerobic Digestion of Livestock Manures. Water, 17(24), 3464. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243464