Numerical Assessment of the Long-Term Dredging Impacts on Channel Evolution in the Middle Huai River

Abstract

1. Introduction

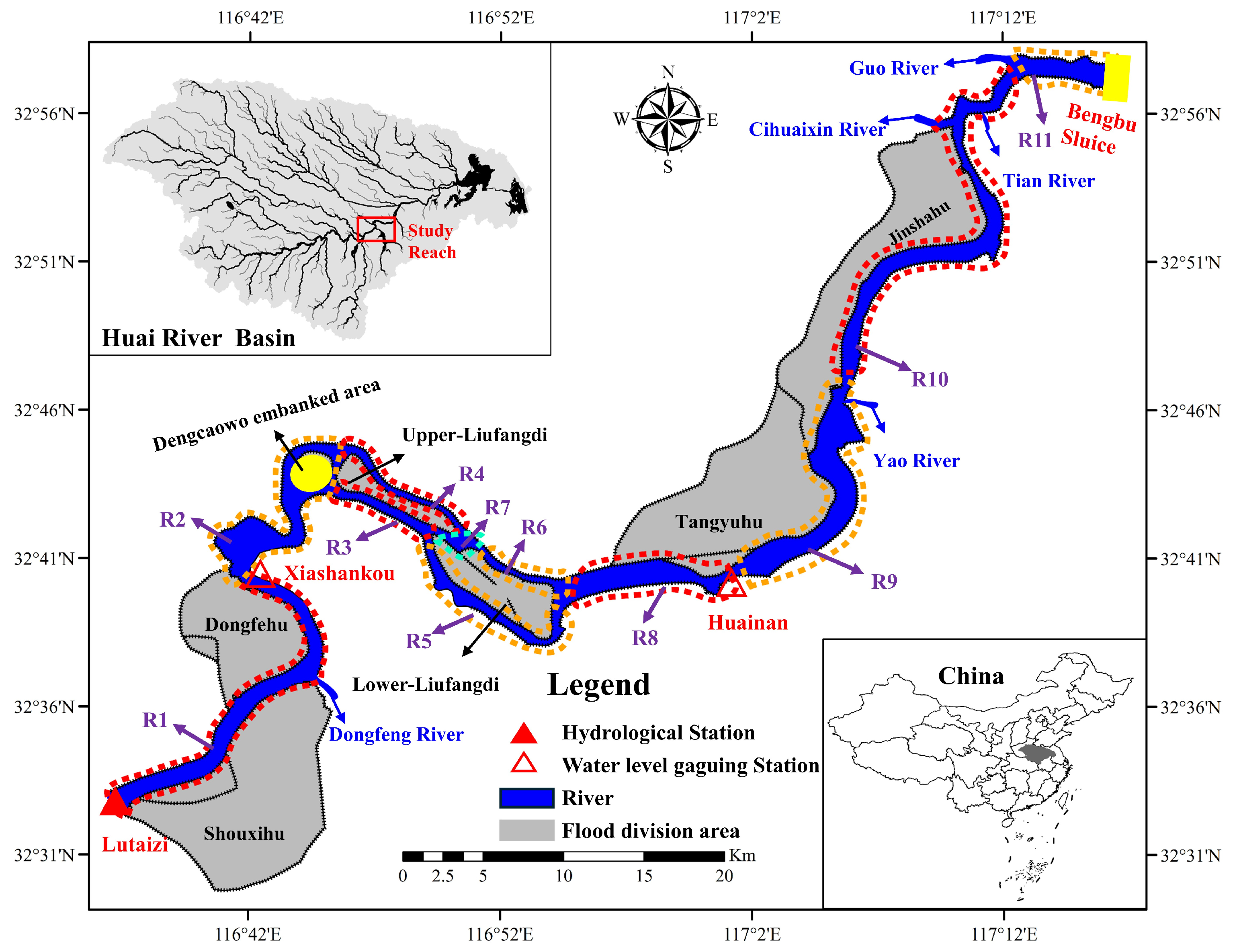

2. Study Area

3. Methodology

3.1. Numerical Model

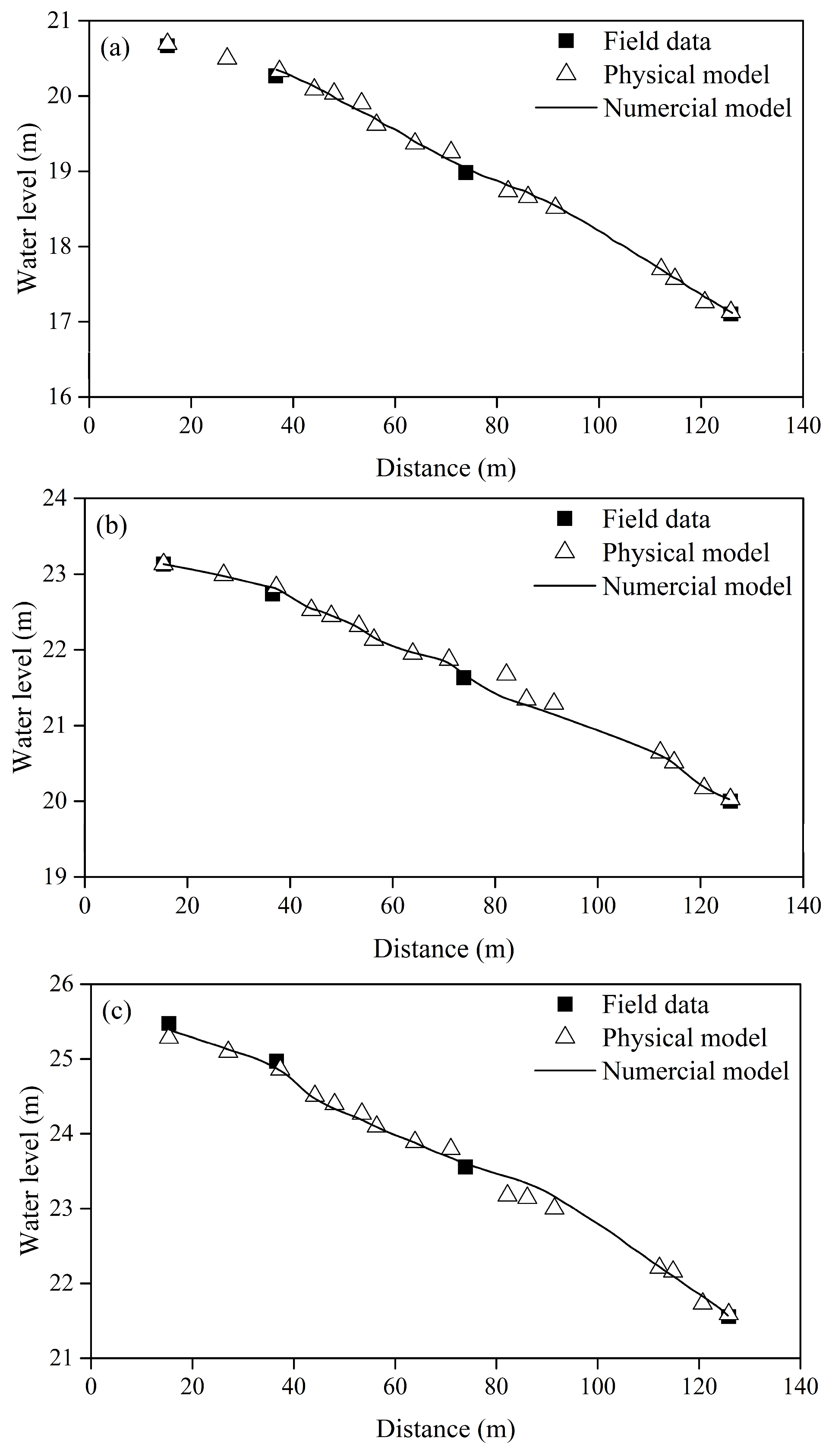

3.2. Model Validation

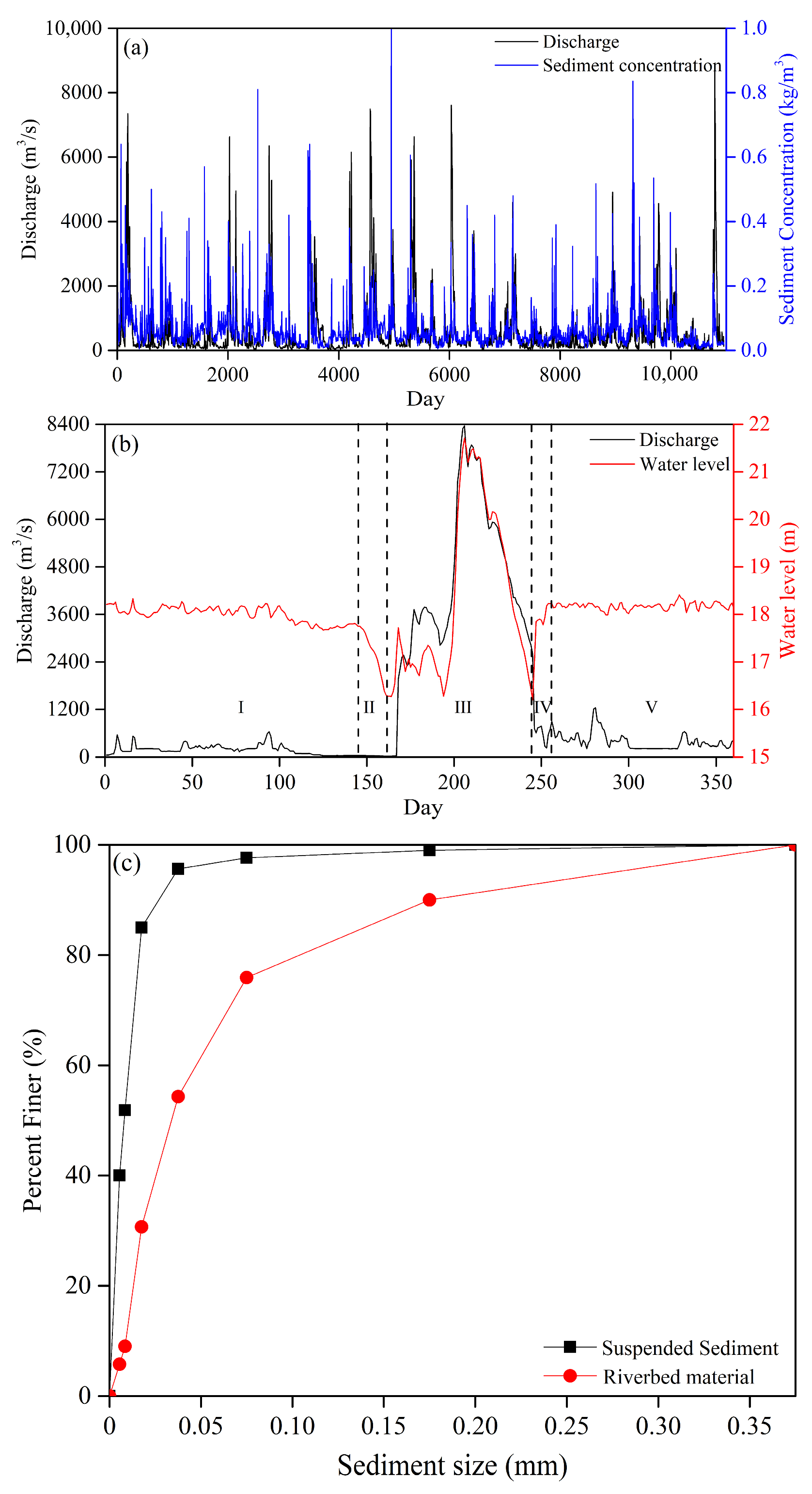

3.3. Model Setup

4. Results

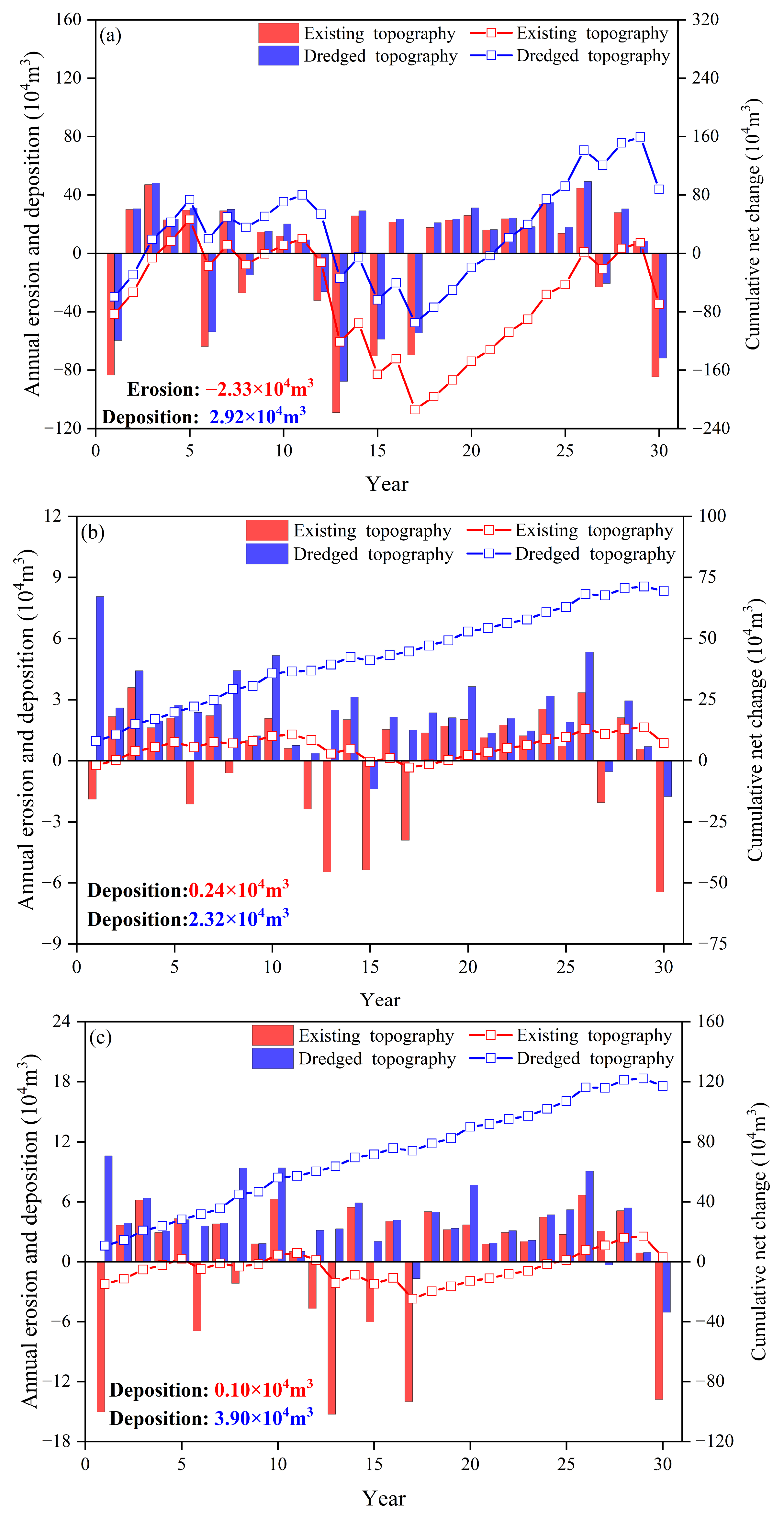

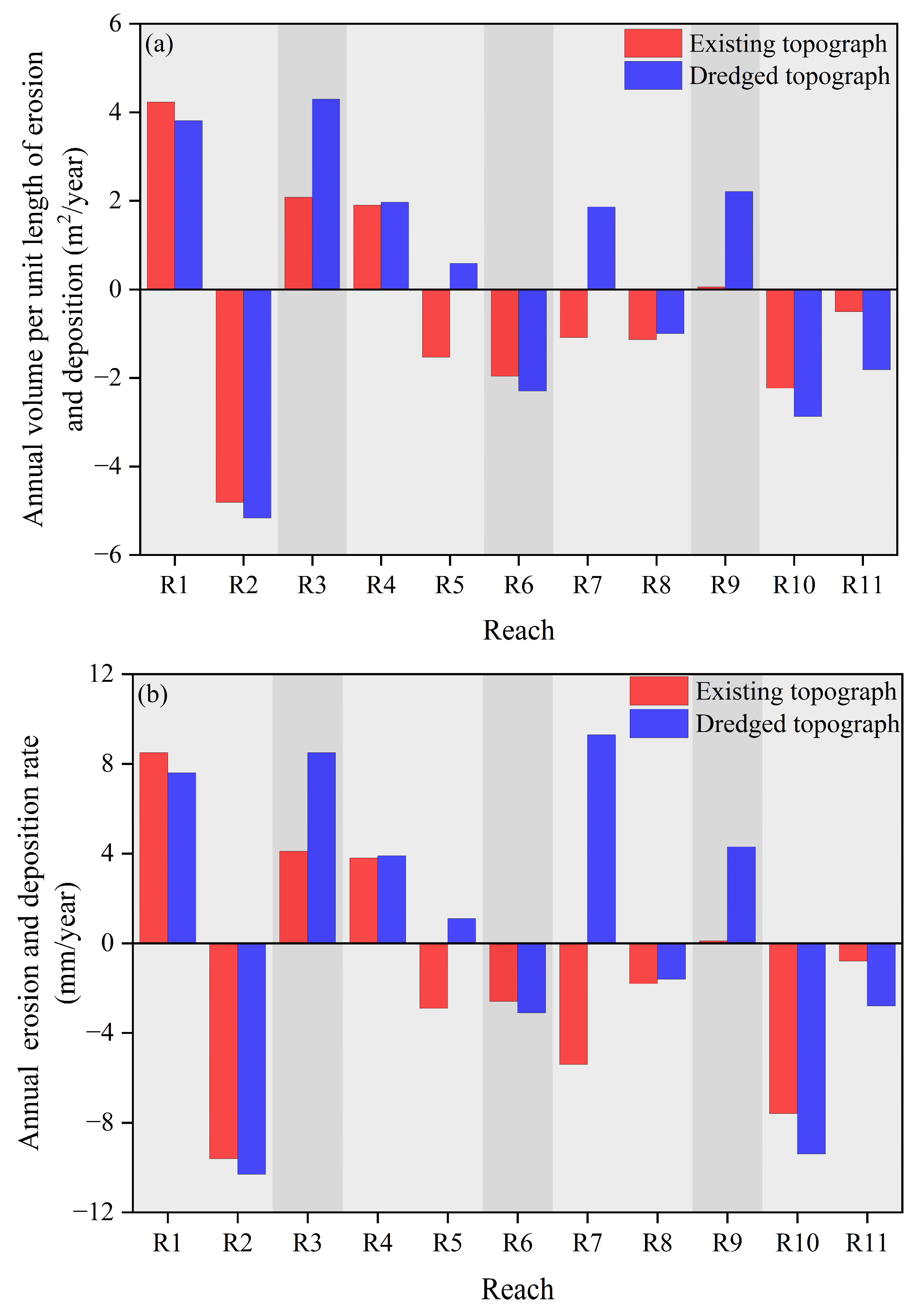

4.1. Patterns of Long-Term Channel Evolution

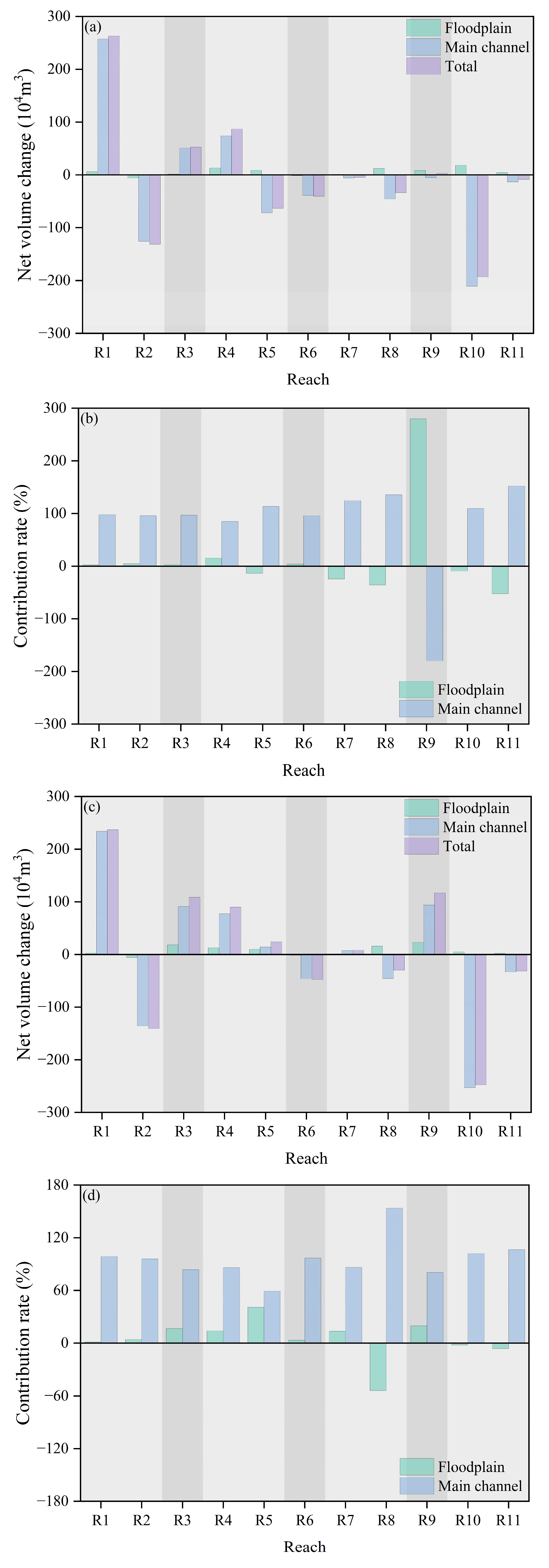

4.2. Adjustment Patterns of the Main Channel and Floodplain

4.3. Temporal Variations in Flow Division Characteristics Within Multiple Channels

5. Discussions

5.1. Multiscale System Responses of Channel Evolution to Dredging

5.2. Implications and Limitations

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The implemented dredging in the Lutaizi–Bengbu Sluice section fundamentally reversed the long-term erosional trend of the channel, transforming the system from a state of net erosion (69.80 × 104 m3) to one of net deposition (87.67 × 104 m3).

- (2)

- Dredging reconfigured the sediment dynamics between the main channel and floodplain and synchronized the erosion–deposition trends of both, with the main channel dominating this process by contributing over 84% of the net volumetric changes.

- (3)

- In the Liufangdi Reach, dredging induced significant spatial heterogeneity in the geomorphic adjustment of adjacent sub-reaches, which exhibited contrasting erosion and deposition behaviors. This geomorphic reorganization altered the flow division characteristics, resulting in a stable and long-term regime with flow division ratios varying by less than 3%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kvočka, D.; Falconer, R.A.; Bray, M. Flood hazard assessment for extreme flood events. Nat. Hazards 2016, 84, 1569–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, L.; Burek, P.; Feyen, L.; Forzieri, G. Global warming increases the frequency of river floods in Europe. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 19, 2247–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.-K.; Zhang, X.; Zwiers, F.W.; Hegerl, G.C. Human contribution to more-intense precipitation extremes. Nature 2011, 470, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Su, B.; Wang, Y.; Xia, J.; Huang, J.; Jiang, T. Flood risk and its reduction in China. Adv. Water Resour. 2019, 130, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; He, B.; Nover, D.; Fan, J.; Yang, G.; Chen, W.; Meng, H.; Liu, C. Floods and associated socioeconomic damages in China over the last century. Nat. Hazards 2016, 82, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S. Study on flood affected population and economic risk assessment and zoning method. China Water Resour. 2023, 8, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhai, J.; Qing, L.; Yao, M. Research on meteorological thresholds of drought and flood disaster: A case study in the Huai River Basin, China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2014, 29, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Ye, A.; Gong, W.; Mao, Y.; Miao, C.; Di, Z. An estimate of human and natural contributions to flood changes of the Huai River. Glob. Planet. Change 2014, 119, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Lv, L.; Yang, X.; Ni, J. Research progress of flood outlet and river regulation in the middle reach of the Huaihe River. J. Sediment Res. 2021, 46, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yu, M.; Deng, L.; Lu, Y. Review on influences of Yellow River intruding into Huaihe River on middle and lower reaches of Huaihe River and flood control measures. Yangtze River 2021, 52, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, B.; Ni, J.; Wang, J. Susceptibility and Periodicity of Water and Sediment Characteristics of Mainstream Huaihe River in Recent 66 Years. J. Yangtze River Sci. Res. Inst. 2020, 37, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Regulation of the middle reaches of the Huaihe River and evaluation on its effect. Yangtze River 2008, 39, 1–3+110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Han, Q.; Guan, J. Study on feasibility and long-term effect of bed dredging on lowering flood level in the reach below Bengbu of Huaihe River. J. Sediment. Res. 2016, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Lu, Q. Study on scale and effect of river dredging aiming at reducing flood level. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2022, 53, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, X.; Yuan, J.; Li, L.; Guan, W. Impacts of channel dredging on hydrodynamics and sediment dynamics in the main channels of the Jiaojiang River Estuary in China. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2023, 42, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraha, A.; Khangaonkar, T.; Michalsen, D.; Brown, S. Numerical feasibility study for dredging and maintenance alternatives in Everett Harbor and Snohomish River. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2022, 56, 102695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, D.K.; Talke, S.; Geyer, W.R.; Al-Zubaidi, H.A.M.; Sommerfield, C.K. Bigger Tides, Less Flooding: Effects of Dredging on Barotropic Dynamics in a Highly Modified Estuary. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2019, 124, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Maren, D.S.; van Kessel, T.; Cronin, K.; Sittoni, L. The impact of channel deepening and dredging on estuarine sediment concentration. Cont. Shelf Res. 2015, 95, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, H.L.; Ding, P.X.; Wang, Z.B.; Yang, S.L.; Lu, J.Y. Morphodynamic impacts of large-scale engineering projects in the Yangtze River delta. Coast. Eng. 2018, 141, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abderrezzak, K.E.K.; Paquier, A. One-dimensional numerical modeling of sediment transport and bed deformation in open channels. Water Resour. Res. 2009, 45, W05404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, S.S.Y. One-Dimensional Modeling of Dam-Break Flow over Movable Beds. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2007, 133, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Xia, J.; Deng, S. One-dimensional modelling of channel evolution in an alluvial river with the effect of large-scale regulation engineering. J. Hydrol. 2019, 575, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, S.; Yu, X.; Du, H.; Zhang, F. Numerical simulations of flow and sediment transport within the Ning-Meng reach of the Yellow River, northern China. J. Arid Land 2017, 9, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhou, M. Modelling of hyperconcentrated flood and channel evolution in a braided reach using a dynamically coupled one-dimensional approach. J. Hydrol. 2018, 561, 622–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canestrelli, A.; Lanzoni, S.; Fagherazzi, S. One-dimensional numerical modeling of the long-term morphodynamic evolution of a tidally-dominated estuary: The Lower Fly River (Papua New Guinea). Sediment. Geol. 2014, 301, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ye, J.; Yang, X. Analysis of the spatio-temporal patterns of dry and wet conditions in the Huai River Basin using the standardized precipitation index. Atmos. Res. 2015, 166, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Wang, J.; Li, F.; Xie, Y.; Jiang, C.; Sun, L. Drought Trends and the Extreme Drought Frequency and Characteristics under Climate Change Based on SPI and HI in the Upper and Middle Reaches of the Huai River Basin, China. Water 2020, 12, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shao, Q.; Xia, J.; Bunn, S.E.; Zuo, Q. Changes of flow regimes and precipitation in Huai River Basin in the last half century. Hydrol. Process. 2010, 25, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xu, S.; Wang, K.; Liang, S.; Su, C.; Feng, Z.; Zhao, M. Comparative Analysis of Extreme Flood Characteristics in the Huai River Basin: Insights from the 2020 Catastrophic Event. Water 2025, 17, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Wu, P.; Sui, J.; Yang, X.; Ni, J. Fluvial geomorphology of the Middle Reach of the Huai River. Int. J. Sediment. Res. 2014, 29, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Cao, H.; Yuan, S.; Xiao, Y.; Jiang, C.; Gualtieri, C. A Numerical Study of Hydrodynamic Processes and Flood Mitigation in a Large River-lake System. Water Resour. Manag. 2020, 34, 3739–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. Flood Disaster Characteristics and Causative Mechanisms in the Middle Reaches of the Huai River. Jianghuai Water Resour. Sci. Technol. 2009, 6, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q. Theoretical study of non equililrium transportation of non uniform suspended load. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2007, 38, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q. Sediment carrying capacity in natural rivers. J. Sediment Res. 2006, 5, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Yu, B.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J. Response of the Channel Regime to the Meng River Diversion and Dredging Project in the Wanglin section of the Huai River. Yangtze River 2021, 52, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, A.D. Hec Models for Water Resources System Simulation: Theory and Experience. Adv. Hydrosci. 1981, 12, 297–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Zhao, L.; Fu, X. Research on Mathematical Model for Sediment in Yellow River. J. Wuhan Univ. Hydraul. Electr. Eng. 1997, 30, 22–26. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFQ&dbname=CJFD9697&filename=WSDD705.004 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Zhang, E.; Zhang, D.; Li, T. Three Steps Method to Compute Unsteady Flow for River Networks. J. Hohai Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 1982, 1, 1–13. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFQ&dbname=CJFD7984&filename=HHDX198201000 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Zhou, J.; Lin, B. One-dimensional mathematical model for suspended sediment by lateral integration. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1998, 124, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.S.; Ni, J. Research Report on River Engineering and Hydraulic Structure Model Tests for the Regulation and Construction Project of Flood Diversion Areas in the Xiaoshankou to Guohekou Reach of the Huai River; Anhui & Huai River Institute of Hydraulic Research: Hefei, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, J.; Yu, B.; Wu, P. A Numerical Study of the Flow and Sediment Interaction in the Middle Reach of the Huai River. Water 2021, 13, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Yu, B.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J. Study on water and sediment transport law of Bengbu-Fushan Reach of main stream of Huaihe River. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2020, 51, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Yu, B.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J. Study on fluvial processes between Bengbu to Fushan reach of the Huaihe River. J. Sediment. Res. 2018, 45, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, L.B.; Castro, Í.B.; Fillmann, G.; Peres, T.F.; Belmino, I.K.C.; Sasaki, S.T.; Taniguchi, S.; Bícego, M.C.; Marins, R.V.; de Lacerda, L.D.; et al. Dredging impacts on the toxicity and development of sediment quality values in a semi-arid region (Ceará state, NE Brazil). Environ. Res. 2021, 193, 110525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, E.; Elsersawy, H.; Hamed, E.; Abdelhaleem, F.S. Sustainability of a navigation channel in the Nile River: A case study in Egypt. River Res. Appl. 2020, 36, 1817–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gob, F.; Houbrechts, G.; Hiver, J.M.; Petit, F. River dredging, channel dynamics and bedload transport in an incised meandering river (the River Semois, Belgium). River Res. Appl. 2005, 21, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendô, A.R.R.; Da Silva, D.V.; Costi, J.; Kirinus, E.P.; Paula, D.P.; Albuquerque, M.G.; Marques, W.C. Hydromorphodynamics modeling of dredging and dumping activities in Mirim lagoon, RS, Brazil. Ocean Eng. 2023, 289, 116219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surian, N.; Rinaldi, M. Morphological response to river engineering and management in alluvial channels in Italy. Geomorphology 2003, 50, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.M.; Winkley, B.R. The response of the Lower Mississippi River to river engineering. Eng. Geol. 1996, 45, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heritage, G.; Entwistle, N. Impacts of River Engineering on River Channel Behaviour: Implications for Managing Downstream Flood Risk. Water 2020, 12, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.K.; Cheng, K.; Luo, M.; Xu, Z.X.; Yan, X.F. Numerical assessment of hydro-morphodynamics affected by altered upstream discharge in the Dujiangyan reach of the Min River, China. Hydrol. Process. 2024, 38, e15113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Liu, X.; Er, H. Dujiangyan Irrigation System—A world cultural heritage corresponding to concepts of modern hydraulic science. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2010, 4, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhou, X.; You, J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ma, K. Wisdom, predicaments, and challenges of a millennium ancient weir—Dujiangyan Project. J. Mt. Sci. 2021, 18, 2971–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Xia, J.; Zhang, Y. Water quality variation in the highly disturbed Huai River Basin, China from 1994 to 2005 by multi-statistical analyses. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 496, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, G.; Wang, R.; Huang, H. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the water-SPM-sediment system from the middle reaches of Huai River, China: Distribution, partitioning, origin tracing and ecological risk assessment. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 230, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xia, J.; Liang, T.; Shao, Q. Impact of Water Projects on River Flow Regimes and Water Quality in Huai River Basin. Water Resour. Manag. 2009, 24, 889–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Arthington, A.H.; Bunn, S.E.; Mackay, S.; Xia, J.; Kennard, M. Classification of Flow Regimes for Environmental Flow Assessment in Regulated Rivers: The Huai River Basin, China. River Res. Appl. 2011, 28, 989–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniazza, G.; Bakker, M.; Lane, S.N. Revisiting the morphological method in two-dimensions to quantify bed-material transport in braided rivers. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2019, 44, 2251–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Ludeña, S.; Franca, M.J.; Cardoso, A.H.; Schleiss, A.J. Evolution of the hydromorphodynamics of mountain river confluences for varying discharge ratios and junction angles. Geomorphology 2016, 255, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite Ribeiro, M.; Blanckaert, K.; Roy, A.G.; Schleiss, A.J. Flow and sediment dynamics in channel confluences. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2012, 117, F01035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niroumand-Jadidi, M.; Bovolo, F. Sentinel-2 Reveals Abrupt Increment of Total Suspended Matter While Ever Given Ship Blocked the Suez Canal. Water 2021, 13, 3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manap, N.; Voulvoulis, N. Environmental management for dredging sediments—The requirement of developing nations. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 147, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reach Number | Extent Description | Length (km) |

|---|---|---|

| R1 | From the Lutaizi to the Xiashankou | 20.81 |

| R2 | From the Xiashankou to the inlet of the LFD Reach | 9.16 |

| R3 | South branch of the Upper-LFD Reach | 8.74 |

| R4 | North branch of the Upper-LFD Reach | 16.50 |

| R5 | South branch of the Lower-LFD Reach | 14.87 |

| R6 | North branch of the Lower-LFD Reach | 7.49 |

| R7 | Erdaohe Reach | 2.36 |

| R8 | From the outlet of the LFD Reach to the Huainan | 9.95 |

| R9 | From the Huainan to the Jinshangkou | 17.66 |

| R10 | From the Jinshangkou to the Guohekou | 28.77 |

| R11 | From the Guohekou to the Bengbu Sluice | 5.67 |

| Topography | Reach | Upper-LFD Reach | Lower-LFD Reach | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Model (m3/s) | Numerical Model (m3/s) | Relative Error (%) | Physical Model (m3/s) | Numerical Model (m3/s) | Relative Error (%) | ||

| Existing topography | R3 | 6360 | 6340 | 0.3 | 4832 | 4820 | 0.2 |

| R4 | 1640 | 1660 | 1.2 | 3168 | 3180 | 0.4 | |

| Dredged topography | R5 | 6704 | 6610 | 1.4 | 4512 | 4375 | 3 |

| R6 | 1296 | 1390 | 7.3 | 3488 | 3625 | 3.9 | |

| Reach | Length (m) | Width (m) | Slope | Dredged Volume (104 m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LTD reach (R3, R6, R7) | 18.23 | 110~260 | 1:4 | 904.05 |

| TYH reach (R9) | 19.68 | 280~320 | 1:4 | 1107.18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ni, J.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, K.; Lu, H.; Wu, P. Numerical Assessment of the Long-Term Dredging Impacts on Channel Evolution in the Middle Huai River. Water 2025, 17, 3466. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243466

Ni J, Zhang H, Cheng K, Lu H, Wu P. Numerical Assessment of the Long-Term Dredging Impacts on Channel Evolution in the Middle Huai River. Water. 2025; 17(24):3466. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243466

Chicago/Turabian StyleNi, Jin, Hui Zhang, Kai Cheng, Haitian Lu, and Peng Wu. 2025. "Numerical Assessment of the Long-Term Dredging Impacts on Channel Evolution in the Middle Huai River" Water 17, no. 24: 3466. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243466

APA StyleNi, J., Zhang, H., Cheng, K., Lu, H., & Wu, P. (2025). Numerical Assessment of the Long-Term Dredging Impacts on Channel Evolution in the Middle Huai River. Water, 17(24), 3466. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243466