1. Introduction

A large portion of Japan’s land area consists of mountainous terrain, resulting in numerous steep rivers that can experience rapid water-level rises during heavy rainfall. Therefore, swift evacuation is critically important in the event of river flooding. Furthermore, recent climate change has increased the frequency of intense short-duration rainfall events. In Japan, the number of rainfall events exceeding 50 mm per hour has increased by approximately 1.5 times [

1]. As a result, the risk of flooding damage, including large-scale floods, has increased dramatically. Sudden heavy rainfall causes river water levels to rise rapidly, shortening the time until flooding occurs and increasing the likelihood of severe inundation damage. In fact, in recent years, the number of rivers exceeding the Flood Dangerous Water Levels (indicating a high risk of overflow) has been on the rise [

2]. As a countermeasure against such disasters, extensive research has been conducted on predicting river water levels. Accurate prediction of water levels during flooding is essential for residents to make appropriate evacuation decisions. For instance, in Japan, issuing evacuation advisories based on flood forecasts made several hours in advance would save many lives.

Conventional water-level prediction methods have employed several physical models to simulate rainfall-runoff processes [

3,

4]. In recent years, deep learning-based models have been reported to achieve even higher prediction accuracy [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. These studies primarily train prediction models using observed rainfall and water level data from upstream observation stations to forecast downstream water levels. However, many rivers lack sufficient observation stations necessary for accurate forecasting. In Japan’s small and medium-sized rivers, upstream observation stations are often absent. For example, during Typhoon No. 10 in 2016, flooding with human casualties occurred in Iwate Prefecture’s Ōmoto River, which had only one water-level observation station [

13]. This highlights the need for high-precision water-level forecasting even in small rivers. Achieving reliable predictions even without upstream observation data enables appropriate evacuation in such river basins. Additionally, it should be noted that some large rivers lack sufficient water-level and rainfall observation stations, indicating a need for data enabling water-level prediction to substitute for upstream observation station data.

As an alternative to rainfall data from rain measurement stations, radar precipitation data observed and published by the Japan Meteorological Agency is available [

14]. Radar precipitation data is observed nationwide on a 1 km grid and is derived from radar reflectivity. Unlike point-based rain gauge data, radar precipitation data provides spatially estimated precipitation amounts at high spatial resolution, enabling the capture of precipitation distribution across entire watersheds. Therefore, it possesses the potential to enable water-level forecasting even in river basins lacking upstream rainfall or water-level observation stations.

Furthermore, many small and medium-sized rivers, and even some large rivers, lack sufficient historical flood records, making it difficult to secure the large data volumes required for deep learning-based prediction models. To address this constraint, transfer learning has been presented as an effective method [

15]. Transfer learning is widely used across various research fields [

15], which reuses knowledge acquired from one task to learn another related task. By applying transfer learning, it becomes possible to construct water-level prediction models for target locations with limited flood records by utilizing data from other rivers with similar characteristics.

For this purpose, we previously proposed a river water-level prediction method using radar rainfall data and transfer learning [

16]. This method achieved high prediction accuracy by using radar rainfall data instead of upstream water levels or rainfall observations. In this method, we first select water-level stations from rivers exhibiting similar trends to the target location and perform pre-training using past flood data from these rivers. Subsequently, we fine-tune the model using flood data from the target location. A key finding in this study is that introducing the newly defined “flow distance” feature enables this transfer learning approach to function effectively. Through evaluation, we demonstrated that the flow distance feature actually plays a crucial role in it. Furthermore, we showed that using radar rainfall data instead of upstream observation data enables water-level prediction several hours ahead with accuracy comparable to conventional models based on upstream observation data.

However, this method requires extracting similar rivers for each target river and constructing individual prediction models for each water-level observation station, complicating model development and management. Furthermore, our previous study [

16] conducted performance evaluations on only a single target river, excluding elements such as dams that could potentially reduce prediction accuracy. Consequently, the prediction accuracy of the model for rivers with varying conditions, such as the presence or absence of dams and elevation differences, has not been evaluated.

In this study, instead of using only similar rivers for prior learning, we utilize historical flood data obtained from all Class-A rivers nationwide to construct a river water-level prediction model applicable to all Class-A rivers throughout Japan, where Class-A rivers are the designated major rivers managed by the Japanese government. Subsequently, we evaluate the prediction accuracy of this prediction model and show the ability of the prediction model pre-trained using all Class-A river data as a generalized water-level prediction model.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work.

Section 3 describes the prediction model applied in this work.

Section 4 presents the evaluation results using actual river observation data.

Section 5 describes the limitation of this study. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes this study.

2. Previous Predictive Models

Hitokoto et al. [

5] proposed a river water-level prediction model based on deep learning and demonstrated that deep learning has the potential to predict river water levels more accurately than traditional physics-based models. Their method employed a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) to construct the prediction model, which used rainfall and water-level data from upstream observation stations to predict the downstream water level. Yamada et al. [

6] showed that higher prediction accuracy than MLP could be achieved by using Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), which is a recurrent neural network suited for time-series data. By utilizing LSTM, the model can learn the temporal characteristics of water level and rainfall observations.

Chen et al. [

8] introduced a convolutional model and proposed a prediction model using a Convolutional LSTM (ConvLSTM), which combines a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and an LSTM to handle two-dimensional time-series data with spatial information. They utilized rainfall data from 50 observation stations in Xixian County, Henan Province, China, to predict water levels, and showed that ConvLSTM was effective for water-level forecasting. Li et al. [

9] also proposed a convolutional model, CNN-LSTM model, and applied it to the Hun River in China, obtaining high prediction accuracy for river water levels.

Xie et al. [

10] introduced an ensemble learning model, which combines one-dimensional (1D) and two-dimensional (2D) CNNs, which also demonstrated high prediction performance. As more advanced water-level prediction approaches, Alizadeh et al. [

11] and Wang et al. [

12] introduced models that incorporate attention mechanisms [

17]. Although these models obtained high predictive performance, they relied heavily on data from numerous observation stations located upstream of the forecast location. In Japan, few rivers have many rainfall and water-level observation stations, making it difficult to apply these methods to high-precision water-level prediction.

On the other hand, several studies have proposed water-level prediction models using radar rainfall. Baek et al. [

18] proposed a CNN-based prediction model that utilized radar rainfall and past water-level data at the prediction site in Korea and demonstrated good prediction accuracy. Li et al. [

19] introduced a CNN-LSTM model using radar rainfall to forecast downstream water levels in Germany based on radar rainfall and upstream observation data, also obtaining high accuracy. However, no study has compared the prediction accuracy of models using upstream observation data with that of models using only radar rainfall and past water levels at the prediction site. Therefore, it remains unclear whether radar rainfall can fully substitute for upstream gauge observations and achieve comparably high predictive performance.

Regarding river water-level prediction using transfer learning, Kimura et al. [

20] developed a CNN-based prediction model and constructed a transfer learning model for predicting water levels one hour ahead using rainfall and water-level observation data from other river basins in Japan. This study demonstrated the effectiveness of transfer learning for short-term (one-hour) forecasting. However, constructing the training data requires selecting rivers exhibiting similar rainfall and water-level variation patterns to the target river. This data generation process is labor-intensive, making it difficult to apply the method to rivers with fewer observation points. Furthermore, this approach does not utilize radar rainfall data and requires upstream observation points for forecasting.

3. Method

3.1. Overview

The prediction model used in this study is built by combining CNN and LSTM. Unlike our previous study, we use the inundation data of all Japanese Class-A rivers rather than selected rivers with similar trends to the prediction point. As shown later, this pre-trained model can be commonly applied for water-level prediction at all stations on all Class-A rivers in Japan. By applying transfer learning that incorporates radar rainfall data, it is possible to predict water levels several hours in advance without relying on upstream gauge stations.

3.2. River Water-Level Prediction Model with CNN and LSTM

This study utilizes a river water-level prediction model that combines CNN and LSTM architectures. First, convolution and pooling operations are applied to radar rainfall and the flow distance matrix to compress spatial information. The compressed features are then concatenated with rainfall and water-level observations from both upstream and target-site gauging stations, and the resulting feature set is fed into the LSTM. The output of the LSTM is passed through a fully connected layer to generate the final water-level prediction. Because the water-level data used in this study are recorded at hourly intervals, the LSTM time steps are aligned to a 1 h resolution. Radar rainfall data, which are provided in 10 min intervals, are aggregated into 1 h intervals, and the six resulting time slices are stacked as input channels for the CNN. Thus, the CNN input comprises seven channels: six channels of radar rainfall and one channel of flow distance. After the CNN performs convolution and pooling operations on this input, the extracted features are combined with rainfall and water-level observations, which are then input to the LSTM at each time step. Finally, the output of the last LSTM step is passed through a fully connected layer, and its output is used as the predicted water level at the target site. In this study, because we consider situations with limited training data, we employ a simplified architecture where each of the CNN, LSTM, and fully connected layers consists of only a single layer.

A schematic of the proposed prediction model is shown in

Figure 1. Each row in the figure corresponds to one time step of the LSTM, aligned with a 1 h interval as mentioned above. Arrows indicate the paths of information flows. As shown on the left side of each row, the CNN block consists of a convolution layer and a pooling layer. Its output is used as the spatial feature input for that time step. On the right side, the LSTM block receives the CNN output as well as the observed values from water level and rainfall gauges as input at each time step. The output from the final LSTM time step is fed into a fully connected layer, and the resulting value is used as the predicted water level for the target location

k hours later, where

k is a preliminary determined value. In short, at each time step of the LSTM, we input the flow distance matrix and the six 10 min interval radar rainfall images of the most recent hour and output the predicted water level

k hours later. By repeating this process, we obtain a

k-hour-ahead water-level prediction. As the computing time for the prediction of each LSTM step takes less than 1 s, the prediction steps operate in real time.

3.3. Transfer Learning Methodology

3.3.1. Flow Distance Matrix

This study uses transfer learning to predict river water levels. A key challenge in this setting is that the terrain and flow direction of the river used for pre-training may differ significantly from the target river. Consequently, the spatial distribution pattern of rainfall at the prediction site and its resulting impact on water-level elevation vary for each river. To address this issue, we introduce the “runoff distance” feature, which quantifies the distance that water travels from each radar rainfall cell to the prediction location. By incorporating runoff distance data into the model input, we aim to capture the temporal lag between rainfall at each location and its impact on water levels at the target location. This approach enables the model to accommodate basin-specific variations, thereby promoting transfer learning between rivers with heterogeneous topography more effectively.

The procedure for generating flow distance data is described below. We utilize a surface flow direction dataset [

21], which provides high-resolution information (1 s arc in both latitude and longitude), indicating the direction of surface runoff on each grid cell among the eight possible neighboring directions. For each grid cell, we trace the water flow path according to its assigned direction in the dataset, accumulating the number of grid cells traversed until reaching the cell corresponding to the prediction location. This cumulative count is defined as the flow distance. If the water path does not eventually reach the prediction location, the flow distance for that cell is marked as null. After calculating the flow path distance for all 1 s cells, the data are transformed to match the resolution of the radar rainfall grid (30 s latitude and 45 s longitude, corresponding to approximately 1 km by 1 km cells). For each radar rainfall cell, the average flow path distance of the 1 s resolution cells contained within that area is calculated. The resulting matrix provides a spatially consistent flow-path distance map that can be used as input to our prediction model, in combination with the radar rainfall map.

A specific example of the flow distance data generation process is illustrated in

Figure 2. This figure demonstrates how flow distance data at an approximate 1 km resolution are generated from surface flow direction data with a resolution of 1 s in both latitude and longitude. In the figure, the shaded red cells with diagonal patterns represent the water-level prediction points, and the arrows indicate the flow direction for each cell provided in the surface flow direction dataset. First, based on the surface flow direction matrix (

Figure 2a), we compute the flow distance at 1 s resolution (

Figure 2b). The numeric values within each cell denote the number of grid cells traversed along the flow path from that cell to the prediction location, that is, the flow distance. Next, we perform spatial averaging over 30 cells in the latitude direction and 45 cells in the longitude direction to resample the data to the approximate 1 km grid, which matches the radar rainfall dataset. This results in the flow distance map at 1 km resolution shown in

Figure 2c, where each cell contains the mean flow distance of the corresponding 1 s resolution cells within that area. The resulting flow distance values provide features aligned with the radar rainfall mesh, enabling the prediction model to consider the spatial delay of rainfall impact based on a terrain-derived hydrological structure.

3.3.2. Transfer Learning Method

The procedure for the transfer learning approach used in this study is as follows. First, we train the prediction model described in

Section 3.2 using the pre-trained dataset explained in

Section 3.3.3, which includes all Class-A rivers in Japan. Next, this pre-trained model is fine-tuned using the limited amount of flood data available at the target location. Specifically, we use the pre-trained weights as initial parameters and re-train the entire model’s weights using the limited data from the target prediction location. By leveraging this two-stage training strategy, we aim to mitigate the shortage of training data specific to the prediction location. The prediction model used in this study is relatively simple (with only 1–2 layers for each of CNN, LSTM, and fully connected layers), and we chose to update all weights during fine-tuning. To prevent overfitting and ensure stable convergence during this fine-tuning phase, a smaller learning rate is employed compared to the pre-training phase, allowing for gradual adjustment of the weights. Furthermore, we posit that the differences in terrain between the pre-training rivers and the target river—such as variations in topography that affect rainfall-runoff dynamics—can be effectively accounted for by incorporating the flow distance information described earlier into the model input. This enables the model to generalize across rivers with varying hydrological and geographical characteristics.

The transfer learning framework applied in this study is illustrated in

Figure 3.

Figure 3a depicts the pre-training phase, while

Figure 3b shows the fine-tuning phase. The prediction model comprises a CNN, an LSTM, and a fully connected layer, utilizing the same model architecture for both pre-training and fine-tuning. In the pre-training phase shown in

Figure 3a, the model is trained using the pre-training dataset, which consists of flood events from all Class-A rivers in Japan. After the pre-training, we go to the fine-tuning phase, where all the weights learned in the pre-training are used as the initial weights, as shown in

Figure 3b. During fine-tuning, the model is re-trained using training data from the target location. In this phase, all model weights are updated, enabling the model to adapt to the specific characteristics of the target river.

3.3.3. Rivers in the Pre-Training Dataset

Our previous work [

16] utilizes radar rainfall and transfer learning, but the dataset for pre-training is selected based on similarity to the target river. Specifically, for all water-level observation stations along Class-A rivers in Japan, we first extract the period during which the highest peak water level was recorded between 2006 and 2021. Then, we calculate the Pearson Correlation Coefficient of the water levels between each station and the target station using the 120 h interval of the extracted flood periods. Observation stations with a correlation coefficient of 0.75 or higher are selected as similar river stations. Here, each 120 h interval is defined as the period starting 72 h before the peak water level and ending 48 h after. However, this method requires extracting similar river stations in advance for each target location and conducting pre-training individually for each prediction location. As a result, the prediction model must be built separately for each river, making it difficult to generalize the operation to multiple rivers.

In this study, to overcome this limitation, we build a water-level prediction model that is commonly applicable to all Class-A rivers in Japan. To achieve this, we build a large dataset that includes all the inundation records in Class-A rivers in Japan from 2006 to 2021. Specifically, we extract all Class-A rivers in Japan for which a Flood Dangerous Water Level has been exceeded at least once between 2006 and 2021, based on the officially designated Flood Dangerous Water Levels [

22,

23]. After excluding the target sites, a total of 247 locations are identified. For each of these sites, we then extract all flood events from 2006 to 2021 during which the water level exceeded the Warning Water Level. After excluding periods with missing radar rainfall data, we obtain a total of 2180 flood periods to use as the pre-training data. This pre-training using the comprehensive dataset demonstrates that it is possible to construct a generalized river water-level prediction model that does not require reconstruction for each individual river. This enables the development of pre-trained models that unify the model construction process across diverse rivers, significantly reducing the required effort.

3.4. Evaluation Method

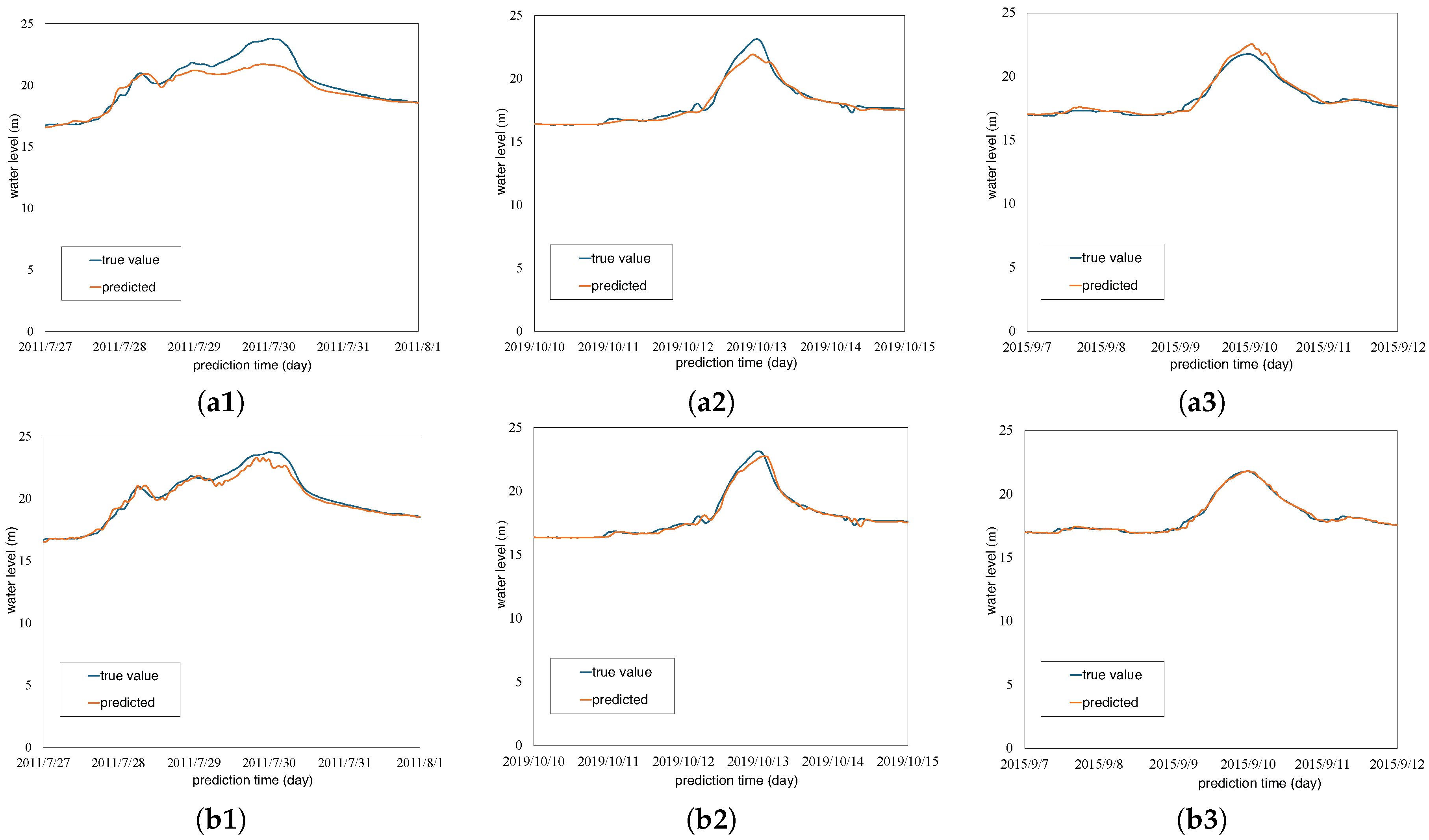

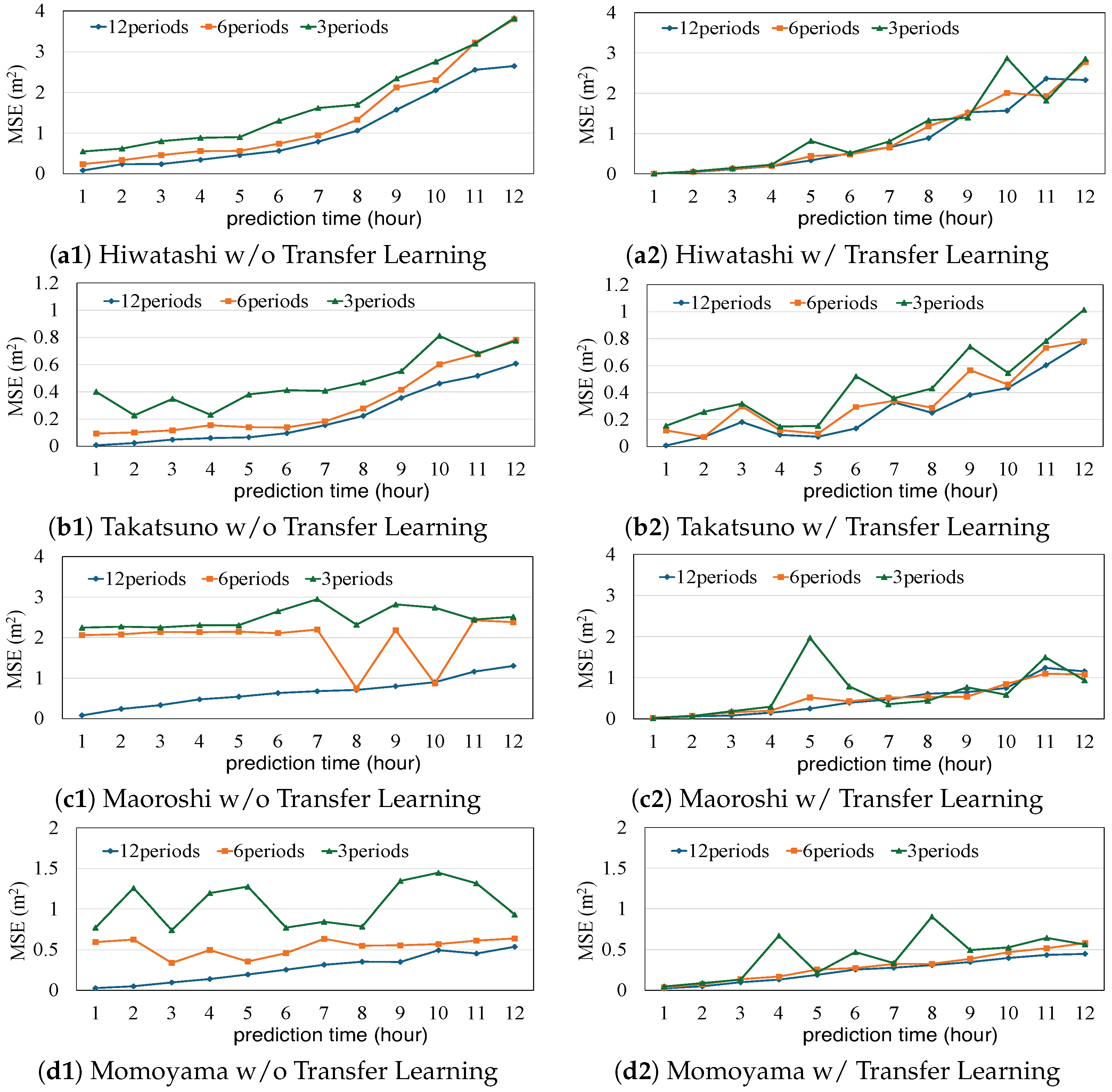

This study proposes utilizing all Class-A rivers in Japan as pre-training data sources and demonstrates the feasibility of constructing a generalized river water-level prediction model applicable to multiple rivers with varying conditions. Specifically, we compare the performance of the following two cases:

Without transfer learning: The CNN–LSTM model is trained solely using water-level, radar rainfall, and flow distance data from the target site, without any pre-training.

With transfer learning: The CNN–LSTM model is pre-trained using data from all Class-A rivers in Japan and then fine-tuned using water-level, radar rainfall, and flow distance data from the target location.

For evaluation, the model was trained using data up to 11 h prior to the reference time and configured to predict water levels from 1 h after to 12 h after the reference time. Prediction performance was evaluated using leave-one-out cross-validation, and the evaluation metric used was the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE). The formulation of MSE and NSE is given in Equations (

1) and (

2).

where

and

denote the

i-th observed and predicted water levels, respectively,

n is the total number of data points, and

is the average of the measurements.

3.5. Study Basin

The water-level prediction sites used in this study are listed in

Table 1. These sites were selected from Japan’s Class-A rivers based on the criterion of diversity in physical characteristics such as the presence of upstream dams, reference elevation, and watershed area. Here, reference elevation denotes the height above mean sea level in Tokyo Bay. Furthermore, to obtain proper results for the fair evaluation of the generalized prediction model, these four sites were excluded from the pre-training dataset. The prediction period is defined as the duration during which water levels exceeding the designated Flood Control Standby Water Level for each observation site occurred between 2006 and 2021 [

22,

23]. Each period consists of 120 h, which includes the 72 h preceding and the 48 h following the peak water level observed during that period. The pre-training dataset consists of 247 observation points and 2180 flood periods, as described in

Section 3.3.3.

3.6. Dataset

The water-level and rainfall data used in this study were obtained from the Hydrological and Water Quality Database [

24], with a temporal resolution of 1 h. Radar rainfall data were acquired from the Japan Meteorological Business Support Center [

25], covering the entire country on an approximately 1 km mesh (30 s latitude × 45 s longitude) at 10 min intervals. Surface flow direction data were obtained from the Japan Surface Flow Direction Map [

21]. The spatial resolution is approximately 30 m (1 s latitude × 1 s longitude), covering the entire Japanese archipelago. These data represent the surface flow direction for each grid cell. For both the target prediction location and the pre-training locations, radar rainfall inputs are extracted over a 60 × 60 km area centered at each measurement location, using the surface flow direction data as spatial context. The surface flow direction data are converted into a flow distance matrix with a 1 km mesh resolution using the procedure described in

Section 3.3.1. The flow distance matrix is then aligned spatially with the radar rainfall data so that both cover the same 60 × 60 km region with the same resolution for each of the prediction and pre-training locations.

3.7. The Detailed Prediction Model

It is well known that biased training data can negatively affect model learning. Therefore, prior to training, the input data were normalized such that all values fall within the range of

. The normalization was performed using the formula shown in Equation (

3).

where

denotes the normalized value,

is the original (pre-normalized) value,

represents the minimum value in the training data, and

represents the maximum value in the training data. The hyperparameter settings used for training the prediction model without transfer learning are listed in

Table 2, while those used for the transfer learning-based model are summarized in

Table 3. The configuration of the CNN layers used in both models is shown in

Table 4. During pre-training, the number of training epochs was set to 1000 to ensure sufficient convergence. For fine-tuning, AdamW [

26,

27] was employed with a small learning rate to perform fine adjustments of the model weights.

In this study, for each prediction site, we determined the optimal parameters for the two prediction models used in evaluation by conducting a preliminary comparison of prediction accuracy under different parameter settings. Specifically, we varied the number of LSTM layers between 1 and 2, and the early stopping patience between 50 and 100 epochs. When using a two-layer LSTM, the dropout rate was set to 0.3. The combination of parameter values that achieved the highest prediction accuracy for each prediction model and site is summarized in

Table 5. These parameter settings were then used for all subsequent evaluations and accuracy comparisons.

5. Limitations

Dam: The evaluation results demonstrated that the predictive model is applicable to various river characteristics, particularly achieving favorable prediction performance in river systems with dams, such as those at Maoroshi and Momoyama. The successful prediction can be explained by the typical dam operation methods prescribed by law. This operation involves reducing reservoir storage before anticipated heavy rainfall and stabiliZing discharge adjustments during rainfall to suppress flow peaks. While successful in predicting water levels under this operation, a limitation of this study is that prediction accuracy may decrease under different dam operation regimes.

Small Rivers: The ultimate goal of our research is to achieve water-level prediction for small rivers. However, this paper has succeeded in predicting only Class-A rivers using a generic model trained on Class-A river data. The runoff characteristics of small rivers could be fundamentally different. As flood data for small rivers is either insufficient or of poor quality, one of the next challenges is to predict water levels in small rivers using flood data from large rivers, which is another limitation of this study.

Radar Data Quality: Radar precipitation data inherently contains a certain degree of error, as it estimates rainfall from radar reflections. Furthermore, the data is provided on a coarse 1 km mesh, with a temporal resolution of 10 min. Another limitation of this paper is the inability to evaluate the quality effects of the radar data. As the government has started providing 250 m mesh data from 2019, it may become possible to examine the effects of geometric mesh resolution in the near future.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we developed a generalized river water level prediction model using transfer learning that incorporates radar rainfall and flow distance as input features. The model was pre-trained on all Class-A rivers in Japan, rather than selecting only rivers similar to the target site. By applying the pre-trained model to multiple rivers with varying characteristics, we aimed to build a generalizable water-level prediction model that could be applied across diverse river basins.

For evaluation, we conducted hours-ahead predictions using historical water level records and examined the effects of varying the pre-training dataset across multiple rivers under different conditions. The results demonstrated that pre-training on all Class-A rivers in Japan consistently improved prediction accuracy across diverse target sites, even more so than when pre-training was performed only on similar rivers. Furthermore, we showed that the transfer learning approach was effective even when only a small number of training periods were available at the prediction site. The model was able to correct prediction errors and achieve accuracy comparable to cases with larger training datasets.

These findings suggest that a river water-level prediction model pre-trained on all Class-A rivers in Japan has strong potential to serve as a generalized prediction model, capable of being effectively applied to multiple rivers with different hydrological and topographical conditions. In summary, our results shown in this paper support the potential to construct a generalized water-level prediction model applicable to a wide range of rivers by utilizing pre-training using a large number of rivers with diverse flow regimes.

Future research tasks could include incorporating various datasets, such as land-use data and soil characteristic data, which significantly influence runoff behavior. Another potential future research task is attempting to predict water levels for small rivers.