Immobilized Sinirhodobacter sp. 1C5-22 for Multi-Metal Bioremediation: Molecular Resistance Mechanisms and Operational Validation in Industrial Wastewater Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Rhizosphere Soil from Mangrove Plants

2.2. Isolation and Identification of Culturable Microorganisms from Rhizosphere Soil

2.2.1. Microbial Isolation and Cultivation

2.2.2. Colony Purification

2.2.3. Molecular Characterization

2.2.4. Comprehensive Strain Profiling

2.3. Determination of Microbial Tolerance to Metal Ions

2.3.1. Initial Tolerance Screening

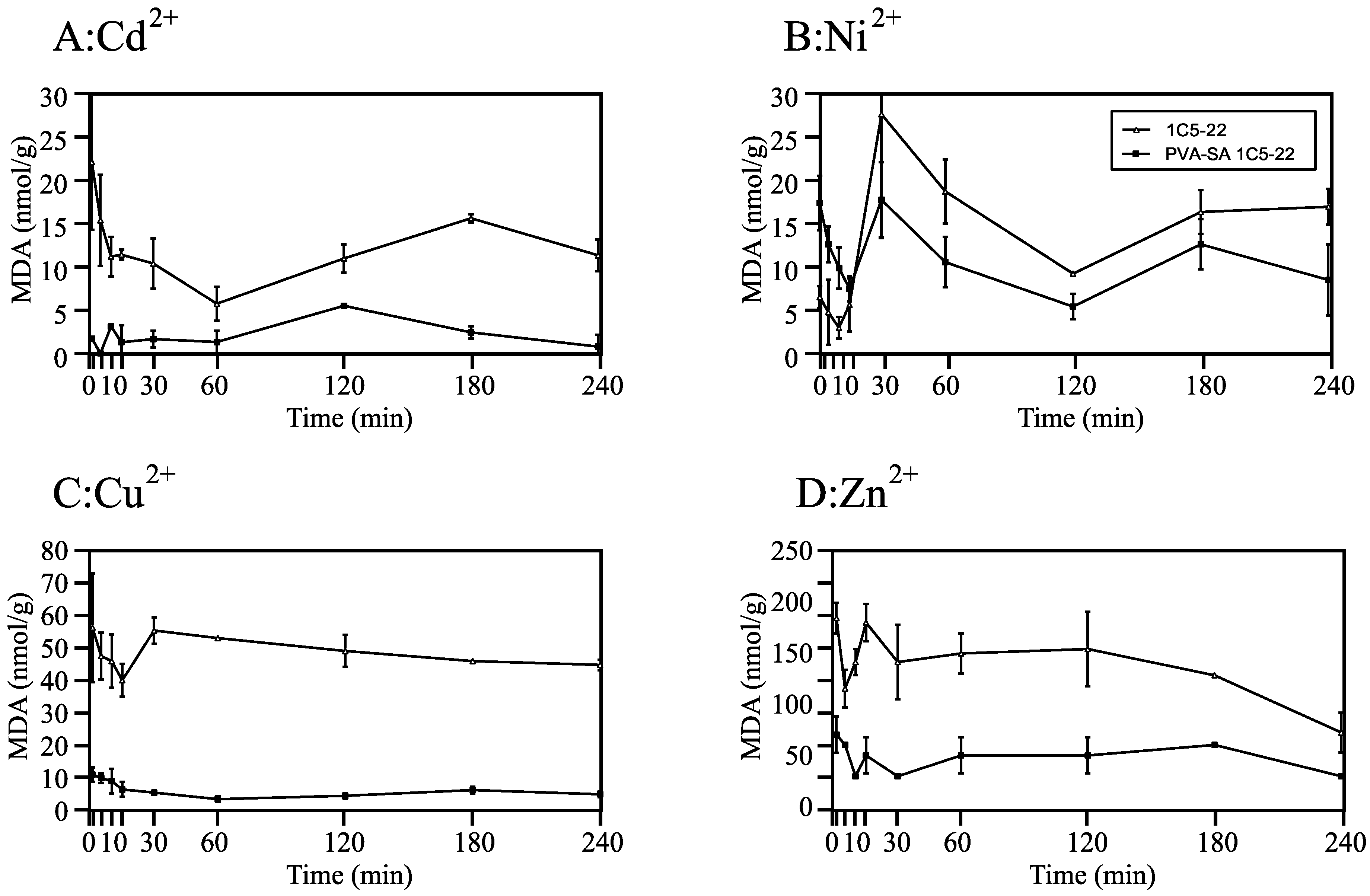

2.3.2. Assessment of Heavy Metal-Induced Oxidative Damage via Malondialdehyde (MDA) Quantification

2.4. Multi-Omics Profiling of Heavy Metal Adsorption in Strain Sinirhodobacter sp. 1C5-22

2.5. Determine the Ability of Microorganisms to Remove Metal Ions

2.5.1. Biosorption Capacity Evaluation Protocol for Cd2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+

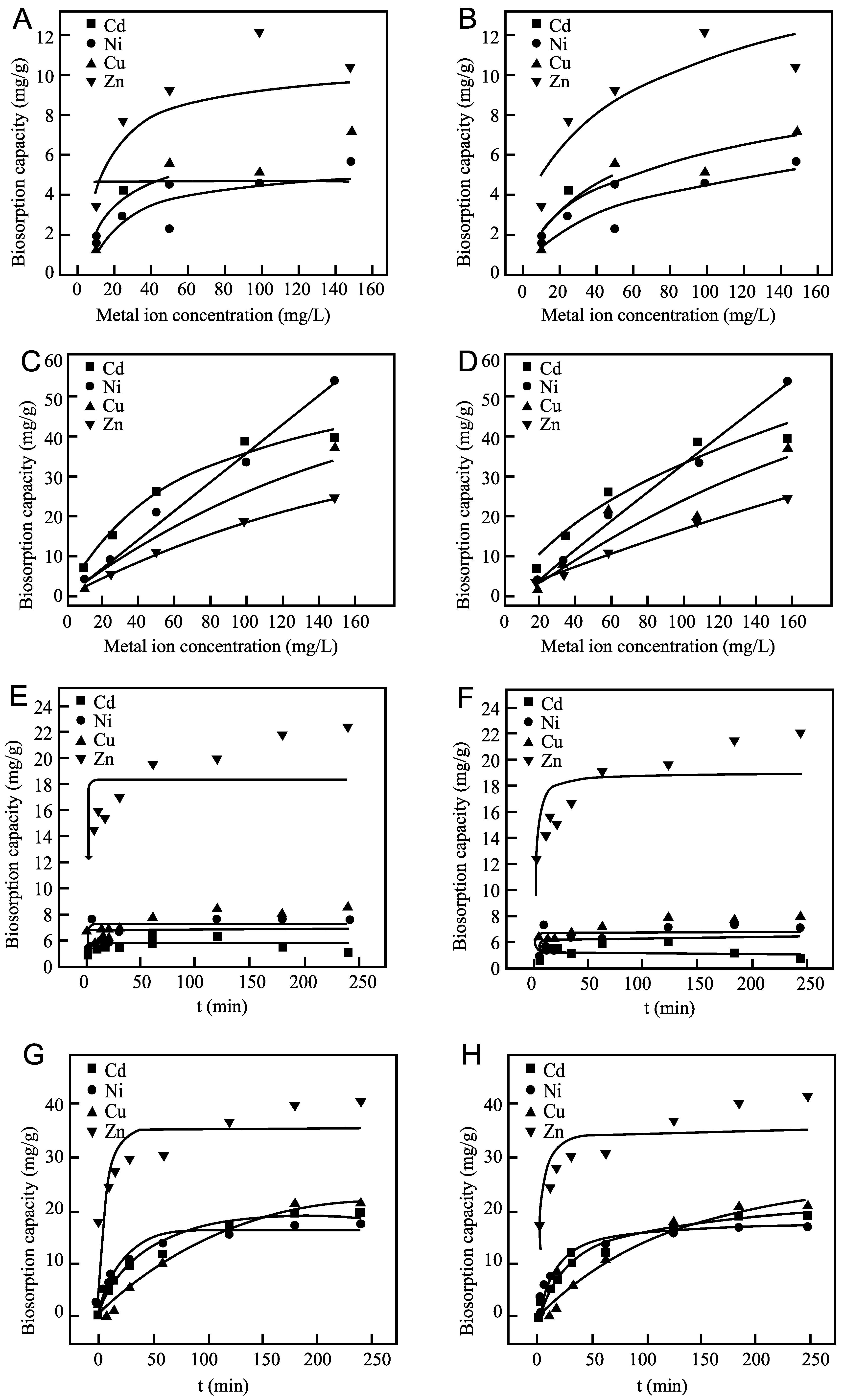

2.5.2. Metal Uptake Equilibrium and Kinetic Analysis

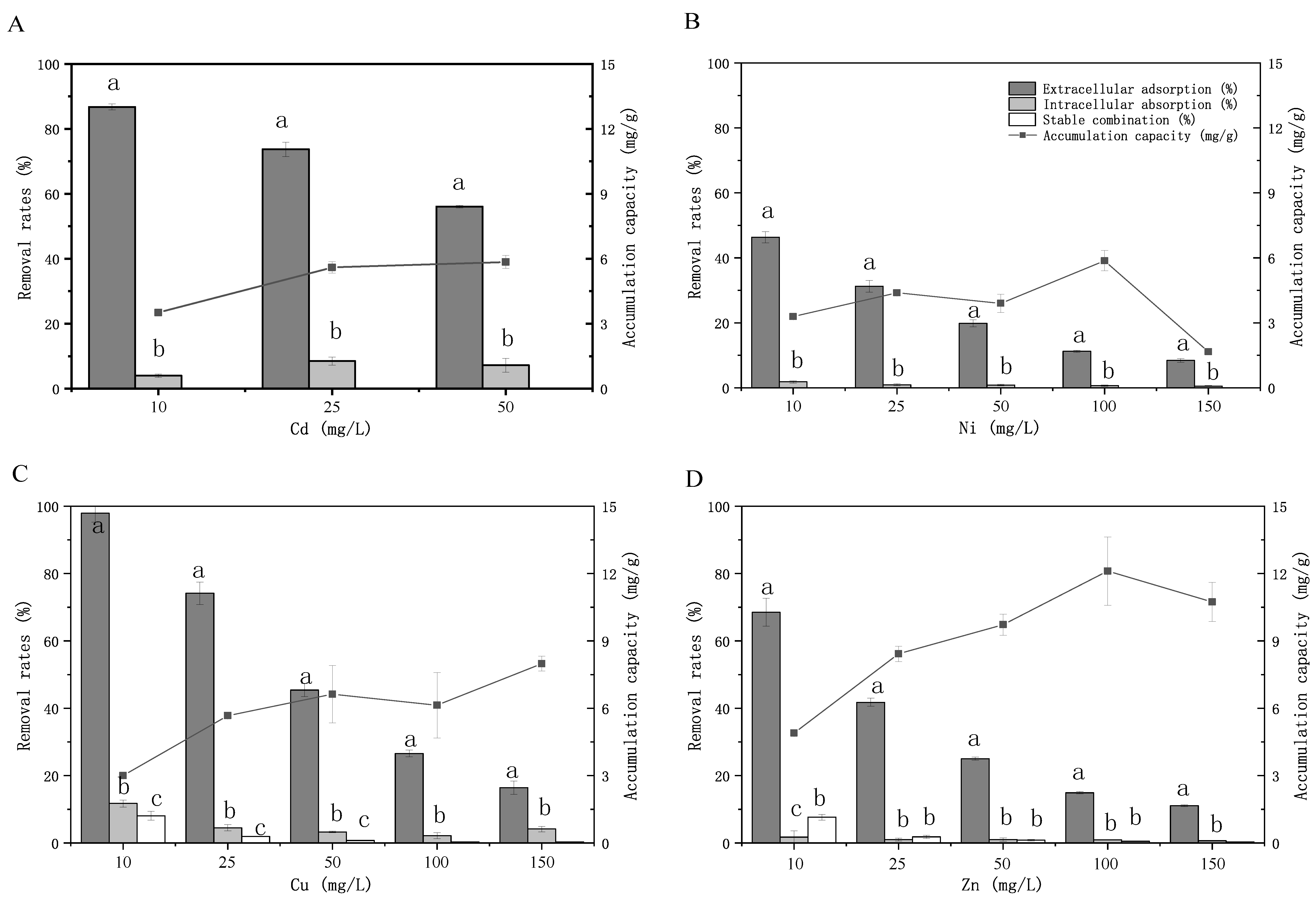

2.5.3. Cellular Domain-Specific Metal Partitioning (Extracellular Adsorption, Intracellular Absorption, Structural Integration)

2.6. Preparation of Immobilized Bacterial Agents

2.7. Determination of Desorption Performance of Immobilized Microbial Agents

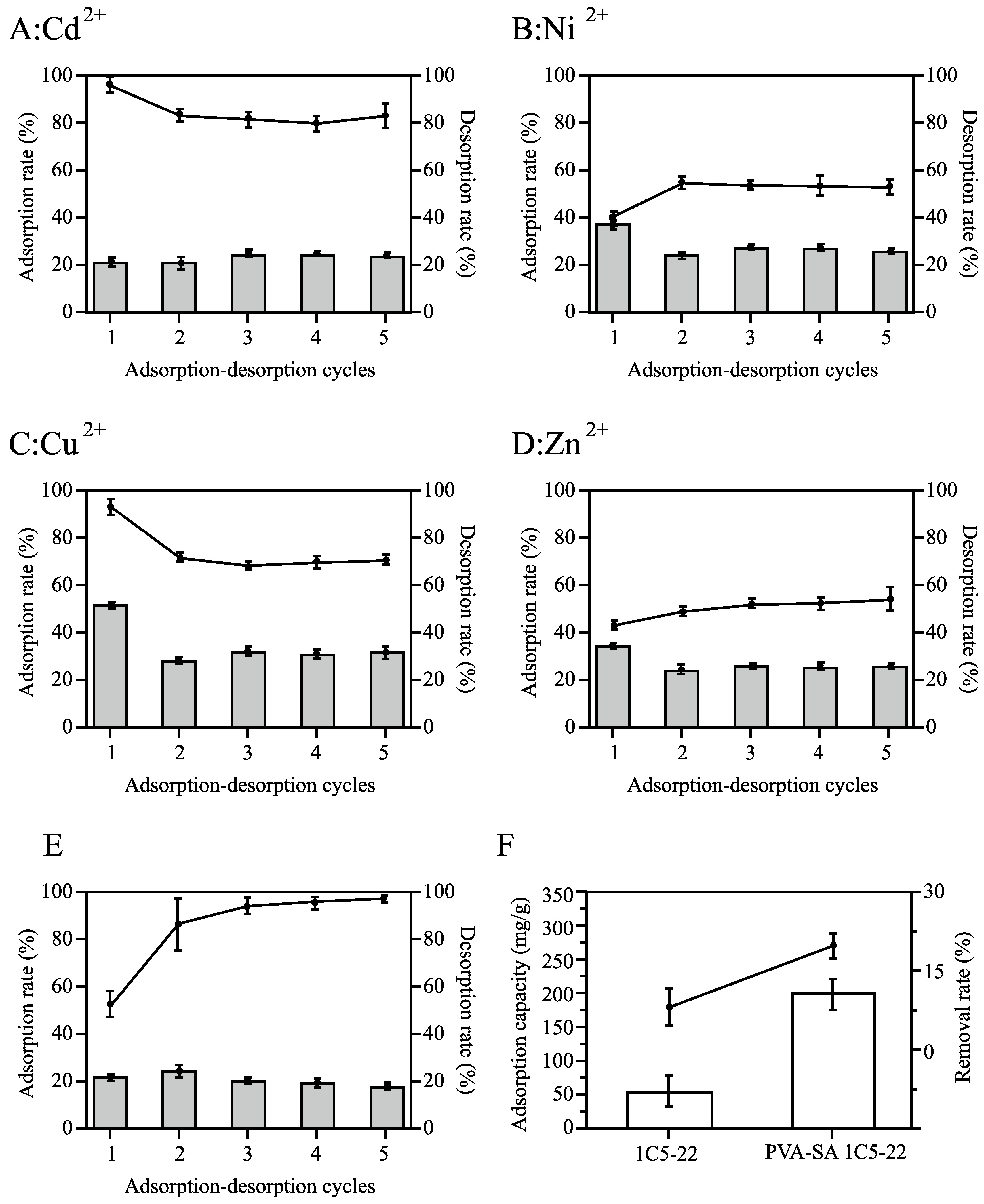

2.7.1. Cyclic Adsorption–Desorption in Model Solutions with Immobilized Cells

2.7.2. Validation via Electroplating Wastewater

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Adsorption and Molecular Mechanisms of Heavy Metal Resistance in Sinirhodobacter sp. 1C5-22

3.1.1. Heavy Metal Tolerance of Strain 1C5-22

3.1.2. Extracellular/Intracellular Metal Distribution in Strain 1C5-22

3.1.3. Molecular Architecture of Heavy Metal Resistance in Sinirhodobacter sp. 1C5-22

3.2. Application of 1C5-22 Immobilized Bacterial Agent for Heavy Metal Removal

3.2.1. Enhanced Metal Enrichment via SA/PVA Immobilization of Strain 1C5-22

3.2.2. Oxidative Damage Mitigation via Immobilization in Strain 1C5-22

3.2.3. Adsorption Behavior and Sustainable Removal Performance of PVA-SA 1C5-22

3.2.4. Performance Validation in Real Electroplating Wastewater

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Li, J.; Jian, S.G.; Ren, H. Mangrove succession enriches the sediment microbial community in South China. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, K.P.; Fernandes, S.O.; Chandan, G.S.; Bharathi, P.A.L. Bacterial contribution to mitigation of iron and manganese in mangrove sediments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2007, 54, 1427–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Gangola, S.; Bhandari, G.; Bhandari, N.S.; Nainwal, D.; Rani, A.; Malik, S.; Slama, P. Rhizospheric bacteria: The key to sustainable heavy metal detoxification strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1229828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimermanova, M.; Pristas, P.; Piknova, M. Biodiversity of Actinomycetes from Heavy Metal Contaminated Technosols. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, G.W.; Ding, S.L.; Zhang, Q.J.; Huang, D.D.; Shang, C.J. A Thirty-Year Record of PTE Pollution in Mangrove Sediments: Implications for Human Activities in Two Major Chinese Metropolises, Shenzhen and Hong Kong. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 68, 102766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.C.; Liao, J.X.; Zhang, Q.J.; Ding, S.L.; He, M.Y.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Shang, C.J.; Chen, S. Diversity and Vertical Distribution of Sedimentary Bacterial Communities and Its Association with Metal Bioavailability in Three Distinct Mangrove Reserves of South China. Water 2022, 14, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthusseri, R.M.; Nair, H.P.; Johny, T.K.; Bhat, S.G. Insights into the response of mangrove sediment microbiomes to heavy metal pollution: Ecological risk assessment and metagenomics perspectives. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 298, 113492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Varela, Z.E.; Orozco-Sánchez, C.J.; Bolívar-Anillo, H.J.; Martínez, J.M.; Rodríguez, N.; Consuegra-Padilla, N.; Robledo-Meza, A.; Amils, R. Halotolerant Endophytic Bacteria Priestia flexa 7BS3110 with Hg2+ Tolerance Isolated from Avicennia germinans in a Caribbean Mangrove from Colombia. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, H.L.; Stahl, D.A. Microbial community structures in anoxic freshwater lake sediment along a metal contamination gradient. Isme J. 2011, 5, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, N.; Yankelzon, I.; Adar, E.; Gelman, F.; Ronen, Z.; Bernstein, A. The Spatial Distribution of the Microbial Community in a Contaminated Aquitard below an Industrial Zone. Water 2019, 11, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Xu, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, J.; Peng, Y.; Liao, J.; Qiao, Y.; Shang, C.; Guo, Z.; et al. A novel yeast strain Geotrichum sp. CS-67 capable of accumulating heavy metal ions. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 236, 113497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, P.; Saravanan, V.; Rajeshkannan, R.; Arnica, G.; Rajasimman, M.; Baskar, G.; Pugazhendhi, A. Comprehensive review on toxic heavy metals in the aquatic system: Sources, identification, treatment strategies, and health risk assessment. Environ. Res. 2024, 258, 119440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, X.; Chen, S.; Xu, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Jia, R.; Zhang, S.; Lin, W.; Jiao, X.; Shi, M.; et al. Bioremediation of heavy metals by mangrove rhizosphere microbes: Extracellular adsorption mechanisms and enhanced performance of immobilized Aestuariibaculum sp. JKB11. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 498, 139968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Singh, N.; Rai, S.N.; Kumar, A.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, M.P.; Sahoo, A.; Shekhar, S.; Vamanu, E.; Mishra, V. Heavy Metal Contamination in the Aquatic Ecosystem: Toxicity and Its Remediation Using Eco-Friendly Approaches. Toxics 2023, 11, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayuo, J.; Rwiza, M.J.; Sillanpää, M.; Mtei, K.M. Removal of heavy metals from binary and multicomponent adsorption systems using various adsorbents—A systematic review. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 13052–13093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Kuila, A. Bioremediation of heavy metals by microbial process. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2019, 14, 100369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.Y.; Xiang, G.H.; Xiao, W.; Yang, Z.L.; Zhao, B.Y. Microbial mediated remediation of heavy metals toxicity: Mechanisms and future prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1420408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.Q.; Zheng, X.L.; Chen, S.; Li, S.F.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y. Exploring the Potential of Natural Products From Mangrove Rhizosphere Bacteria as Biopesticides Against Plant Diseases. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 2925–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Chen, J.; Ge, Q.; Sun, J.; Guo, W.; Wang, J.; Peng, L.; Xu, Q.; Fan, G.; Zhang, W.; et al. Draft Genomes and Comparative Analysis of Seven Mangrove Rhizosphere Associated Fungi solated From Kandelia obovata and Acanthus ilicifolius. Front. Fungal Biol. 2021, 2, 626904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, B. Heavy metal-induced stress in eukaryotic algae-mechanisms of heavy metal toxicity and tolerance with particular emphasis on oxidative stress in exposed cells and the role of antioxidant response. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 16860–16911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caracciolo, A.B.; Terenzi, V. Rhizosphere Microbial Communities and Heavy Metals. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, K.H.H.; Mustafa, F.S.; Omer, K.M.; Hama, S.; Hamarawf, R.F.; Rahman, K.O. Heavy metal pollution in the aquatic environment: Efficient and low-cost removal approaches to eliminate their toxicity: A review. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 17595–17610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovida, A.F.D.; Costa, G.; Santos, M.I.; Silva, C.R.; Freitas, P.N.N.; Oliveira, E.P.; Pileggi, S.A.V.; Olchanheski, R.L.; Pileggi, M. Herbicides Tolerance in a Pseudomonas Strain Is Associated With Metabolic Plasticity of Antioxidative Enzymes Regardless of Selection. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 673211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.F.; Li, X.; Yu, L.; Wang, T.Q.; Wang, J.N.; Liu, T.T. Review of soil heavy metal pollution in China: Spatial distribution, primary sources, and remediation alternatives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 181, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, A.J.M. Assessment of heavy metal pollution from anthropogenic activities and remediation strategies: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 246, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawwam, G.E.; Abdelfattah, N.M.; Abdel-Monem, M.O.; Jahin, H.S.; Omer, A.M.; Abou-Taleb, K.A.; Mansor, E.S. An immobilized biosorbent from Paenibacillus dendritiformis dead cells and polyethersulfone for the sustainable bioremediation of lead from wastewater. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmuir, I. The Adsorption of Gases on Plane Surfaces of Glass, Mica adn Platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918, 40, 1361–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundlich, H.M.F. Über die Adsorption in Lösungen. Z. Phys. Chem. 1907, 57, 385–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagergren, S. Zur Theorie der sogenannten Adsorption gelöster Stoffe. K. Sven. Vetenskapsakad. Handl. 1898, 24, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.L.; Lan, R.; He, L.R.; Liu, H.Y.; Pei, X.J. A critical review of adsorption isotherm models for aqueous contaminants: Curve characteristics, site energy distribution and common controversies. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 329, 117104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijada, C.; Leite-Rosa, L.; Berenguer, R.; Bou-Belda, E. Enhanced Adsorptive Properties and Pseudocapacitance of Flexible Polyaniline-Activated Carbon Cloth Composites Synthesized Electrochemically in a Filter-Press Cell. Materials 2019, 12, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.W.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Tu, B.J. Immobilization of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria by polyvinyl alcohol and sodium alginate. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2017, 48, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.S.; Xing, Q.S. Study on properties and biocompatibility of poly (butylene succinate) and sodium alginate biodegradable composites for biomedical applications. Mater. Res. Express 2022, 9, 085403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavinia, G.R.; Soleymani, M.; Sabzi, M.; Azimi, H.; Atlasi, Z. Novel magnetic polyvinyl alcohol/laponite RD nanocomposite hydrogels for efficient removal of methylene blue. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 2617–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.Q.; Chen, M.; Zhou, S.G.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, Y. Sinorhodobacter ferrireducens gen. nov., sp nov., a non-phototrophic iron-reducing bacterium closely related to phototrophic Rhodobacter species. Antonie Leeuwenhoek Int. J. Gen. Mol. Microbiol. 2013, 104, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.W.; Hoang, T.S.; Rhee, M.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Im, W.T. Sinirhodobacter hankyongi sp. nov., a novel denitrifying bacterium isolated from sludge. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.Y.; Xu, J.J.; Sun, M.; Yu, P.; Ma, Y.M.; Xie, L.; Chen, L.M. Comparative secretomic and proteomic analysis reveal multiple defensive strategies developed by Vibrio cholerae against the heavy metal (Cd2+, Ni2+, Pb2+, and Zn2+) stresses. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1294177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mergeay, M.; Monchy, S.; Vallaeys, T.; Auquier, V.; Benotmane, A.; Bertin, P.; Taghavi, S.; Dunn, J.; van der Lelie, D.; Wattiez, R. Ralstonia metallidurans, a bacterium specifically adapted to toxic metals: Towards a catalogue of metal-responsive genes. Fems Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Deeb, B. Plasmid Mediated Tolerance and Removal of Heavy Metals by Enterobacter sp. Am. J. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2009, 5, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.F.; Li, Q.; Lin, Y.; Hou, Y.; Deng, Z.Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, H.T.; Xia, Z.M. Biochemical and genetic basis of cadmium biosorption by Enterobacter ludwigii LY6, isolated from industrial contaminated soil. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 264, 114637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Chen, W.G.; Zhang, Z.L.; Qin, F.; Jiang, J.; He, A.F.; Sheng, G.D. Enhanced removal of cadmium from wastewater with coupled biochar and Bacillus subtilis. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 83, 2075–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rulísek, L.; Vondrásek, J. Coordination geometries of selected transition metal ions (Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Cd2+, and Hg2+) in metalloproteins. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1998, 71, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouabidi, Z.B.; El-Naas, M.H.; Zhang, Z.E. Immobilization of microbial cells for the biotreatment of wastewater: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, P.A.; Olamide, A.N.; Rafi, N.; Wahid, S.; Wasiu, I.A.; Sunday, O.O. Sodium Alginate/Polyvinyl Alcohol Immobilization of Brevibacillus brevis OZF6 Isolated from Waste Water and Its Role in the Removal of Toxic Chromate. Biotechnol. J. Int. 2016, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyurek, S.B. A comparative study for petroleum removal capacities of the bacterial consortia entrapped in sodium alginate, sodium alginate/poly(vinyl alcohol), and bushnell haas agar. Pet. Sci. 2024, 21, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Z.; Yan, H.J.; Zhou, J.C.; Zuo, Z.H.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wu, L.Y.; Zhao, W.L.; Wu, Z.G. Immobilization of a novel formaldehyde-degrading fungus in polyvinyl alcohol-sodium alginate beads for continuous wastewater treatment. Biochem. Eng. J. 2025, 221, 109802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.T.; Deng, D.; Yuan, Y.; Li, W.; Lin, Q.L.; Deng, J.; Zhong, F.F.; Wang, L. Integrated degradation of bacteria, organic pollutants, total phosphorus, and antibiotics in food wastewater through immobilization of Bacillus velezensis on polyethylene glycol-polyvinyl alcohol/sodium alginate/ nano-TiO2 microspheres. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 303, 140750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.Y.; Chen, W.W.; Ren, X.Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.Q. Enhanced Biodegradation of Methyl Orange Through Immobilization of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 by Polyvinyl Alcohol and Sodium Alginate. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, J.; Das, S. Characterization and cadmium-resistant gene expression of biofilm-forming marine bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa JP-11. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 14188–14201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.I.; Malik, A. Biosorption of nickel and cadmium by metal resistant bacterial isolates from agricultural soil irrigated with industrial wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 3149–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.H.; Chen, W.L.; Cai, P.; Rong, X.M.; Feng, X.H.; Huang, Q.Y. Competitive adsorption of Pb and Cd on bacteria-montmorillonite composite. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 218, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.W.; Zhang, L.; Narty, O.D.; Li, R.R. Adsorption Characteristics of Cu2+ on Natural Zeolite from Baiyin, China. Asian J. Chem. 2013, 25, 3161–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, S.Y.; Fan, D.; Rao, X.; Chen, J.H.; Wen, J.; Zhu, Y.G.; Sun, W. Computational Insights into the Adsorption Mechanism of Zn Ion on the Surface (110) of Sphalerite from the Perspective of Hydration. Minerals 2023, 13, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gola, D.; Malik, A.; Namburath, M.; Ahammad, S.Z. Removal of industrial dyes and heavy metals by Beauveria bassiana: FTIR, SEM, TEM and AFM investigations with Pb(II). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 20486–20496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gola, D.; Dey, P.; Bhattacharya, A.; Mishra, A.; Malik, A.; Namburath, M.; Ahammad, S.Z. Multiple heavy metal removal using an entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 218, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gururajan, K.; Belur, P.D. Screening and selection of indigenous metal tolerant fungal isolates for heavy metal removal. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2018, 9, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, F.; Sadeghizadeh, A.; Neysan, F.; Heydari, M. Fabrication of nanofibers using sodium alginate and Poly(Vinyl alcohol) for the removal of Cd2+ ions from aqueous solutions: Adsorption mechanism, kinetics and thermodynamics. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.W.; Gao, Y.C.; Du, J.H.; Zhang, W.; Huang, Y.J.; Zhao, Q.Q.; Duan, L.C.; Liu, Y.J.; Naidu, R.; Pan, X.L. Single and Binary Adsorption Behaviour and Mechanisms of Cd2+, Cu2+ and Ni2+ onto Modified Biochar in Aqueous Solutions. Processes 2021, 9, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Liu, Y.J.; Naidu, R.; Du, J.H.; Qi, F.J.; Donne, S.W.; Islam, M.M. Mesoporous Biopolymer Architecture Enhanced the Adsorption and Selectivity of Aqueous Heavy-Metal Ions. Acs Omega 2021, 6, 15316–15331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, N.K.; Al-Zaban, M.; Albarakaty, F.M.; Abdelwahab, S.F.; Hassan, S.H.A.; Fawzy, M.A. Kinetic, Isotherm and Thermodynamic Aspects of Zn2+ Biosorption by Spirulina platensis: Optimization of Process Variables by Response Surface Methodology. Life 2022, 12, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Y.; Zeng, G.M.; Tang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.Y.; Lei, X.X.; Wu, M.S.; Li, Z.; Liu, C. Cr(VI) reduction by Pseudomonas aeruginosa immobilized in a polyvinyl alcohol/sodium alginate matrix containing multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 10733–10736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorova, K.; Velkova, Z.; Stoytcheva, M.; Kirova, G.; Kostadinova, S.; Gochev, V. Novel composite biosorbent from Bacillus cereus for heavy metals removal from aqueous solutions. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2019, 33, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qiao, Y.; Huang, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jia, R.; Zhang, S.; Lin, W.; Jiao, X.; et al. Immobilized Sinirhodobacter sp. 1C5-22 for Multi-Metal Bioremediation: Molecular Resistance Mechanisms and Operational Validation in Industrial Wastewater Systems. Water 2025, 17, 3450. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243450

Qiao Y, Huang X, Chen S, Zhang Z, Xu Y, Zhang X, Jia R, Zhang S, Lin W, Jiao X, et al. Immobilized Sinirhodobacter sp. 1C5-22 for Multi-Metal Bioremediation: Molecular Resistance Mechanisms and Operational Validation in Industrial Wastewater Systems. Water. 2025; 17(24):3450. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243450

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiao, Yue, Xiaojun Huang, Si Chen, Zuye Zhang, Ying Xu, Xiaorui Zhang, Runmei Jia, Song Zhang, Wenting Lin, Xian Jiao, and et al. 2025. "Immobilized Sinirhodobacter sp. 1C5-22 for Multi-Metal Bioremediation: Molecular Resistance Mechanisms and Operational Validation in Industrial Wastewater Systems" Water 17, no. 24: 3450. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243450

APA StyleQiao, Y., Huang, X., Chen, S., Zhang, Z., Xu, Y., Zhang, X., Jia, R., Zhang, S., Lin, W., Jiao, X., Chen, H., Guo, Z., Ye, X., Wu, Z., & Lin, Z. (2025). Immobilized Sinirhodobacter sp. 1C5-22 for Multi-Metal Bioremediation: Molecular Resistance Mechanisms and Operational Validation in Industrial Wastewater Systems. Water, 17(24), 3450. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243450