Contribution of Hydrogeochemical and Isotope (δ2H and δ18O) Studies to Update the Conceptual Model of the Hyposaline Natural Mineral Waters of Ribeirinho and Fazenda Do Arco (Castelo de Vide, Central Portugal)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geomorphological, Climatological, Geological and Hydrogeological Framework

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Physico-Chemical Signatures of the Waters

4.2. Isotopic (δ2H and δ18O) Signatures of the Waters

5. Updating of the Conceptual Hydrogeological Model

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moore, J.E. Field Hydrogeology: A Guide for Site Investigations and Report Preparation; Lewis Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brassington, F.C. A proposed conceptual model for the genesis of the Derbyshire thermal springs. Q. J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 2007, 40, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, J.M.; Carreira, P.M.; Caçador, P.; Antunes da Silva, M. Update of the Interpretive Conceptual Model of Ladeira de Envendos Hyposaline Hydromineral System (Central Portugal): A Contribution to Its Sustainable Use. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira da Silva, A.M.; Condesso Melo, M.T.; Marques da Silva, M.A. Modelo conceptual e caracterização hidrogeológica preliminar do sistema aquífero da Serra do Buçaco. In Proceedings of the Actas das Jornadas Luso-Espanholas sobre As Águas Subterrâneas no Noroeste da Península Ibérica, La Coruña, Spain, 3–6 July 2000. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

- Simões Cortez, A. Águas Minerais Naturais e de Nascente da Região Centro, 1st ed.; Mare Liberum: Aveiro, Portugal, 2012; pp. 483–485. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Feio, M.; Almeida, G. A Serra de S. Mamede. Finisterra 1980, 15, 30–52. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, J.P.; Silva, M.L. Aspectos da Hidrogeologia e Qualidade das Águas Associadas à formação Carbonatada de Escusa (Castelo de Vide). In Revista de Geologia Económica Aplicada e do Ambiente (GEOLIS); Carlos Romariz, C., Ed.; Secção de Geologia Económica e Aplicada da Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 1992; pp. 19–32. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, J.P. Hidrogeologia da Formação Carbonatada de Escusa (Castelo de Vide). Master’s Thesis, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Departamento de Geologia, Lisboa, Portugal, 1993. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, J.P.; Silva, M.L.; Carreira, P.M.; Soares, A.M. Aplicação de Métodos Geoquímicos Isotópicos à Interpretação da Hidrodinâmica do Aquífero Carbonatado da Serra de S. Mamede (Castelo de Vide). In VII Congresso de Espanha de Geoquímica; CEDEX: Madrid, Spain, 1997; pp. 544–551. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, A.P.; Perdigão, J.C.; Carvalho, H.F.; Peres, A.M. Notícia Explicativa da Folha 28 D–Castelo de Vide, Carta Geológica de Portugal na Escala 1/50,000; Direcção-Geral de Minas e Serviços Geológicos: Lisboa, Portugal, 1973. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Morais Almeida, A.; Dias, D.; Almeida, M.; Marques, J.M.; Antunes da Silva, M. Contribuição para o desenvolvimento do modelo conceptual de circulação da Água Mineral Natural de Castelo de Vide. In Proceedings of the Livro de Actas do 12º Seminário sobre Águas Subterrâneas, Coimbra, Portugal, 7–8 March 2019; pp. 18–21. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

- IAEA. Training Course Series 35 Laser Spectroscopic Analysis of Liquid Water Samples for Stable Hydrogen and Oxygen Isotopes. Performance Testing and Procedures for Installing and Operating the LGR DT-100 Liquid Water Stable Analyser, 1st ed.; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2009; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- IAEA. Procedure and Technique Critique for Tritium Enrichment by Electrolysis at IAEA Laboratory, 1st ed.; Technical Procedure nº19; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 1976; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Freeze, A.R.; Cherry, J.A. Groundwater; Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, NJ, USA, 1979; pp. 82–134. [Google Scholar]

- Appelo, C.A.J.; Postma, D. Geochemistry, Groundwater and Pollution, 1st ed.; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 1–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço, C.; Ribeiro, L. Classificação das águas minerais naturais e de nascente de Portugal segundo as suas características físico-químicas. In 7º Congresso da Água; LNEC: Lisboa, Portugal, 2004. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2009/54/EC. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2009/54/oj (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Todd, E.C.T.; Sherman, D.M.S.; Purton, J.A.P. Surface Oxidation of Pyrite under Ambient Atmospheric and Aqueous (pH = 2 to 10) Conditions: Electronic Structure and Mineralogy from X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2003, 67, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, I.D.; Fritz, P. Environmental Isotopes in Hydrogeology; Lewis Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Geyh, M. Environmental Isotopes in Hydrological Cycle. Principles and Applications; IHP-V, Technical Documents in Hydrology, No. 39; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2000; Volume IV. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, H. Isotopic variations in meteoric waters. Science 1961, 133, 1702–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreira, P.; Nunes, D.; Valério, P.; Araújo, M.F. A 15-year record of seasonal variation in the isotopic composition. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2009, 281, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, K.; Gibson, J.J.; Aggarwal, P. Deuterium excess in precipitation and its climatological significance. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2002. Available online: http://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/publications/PDF/CSP-13-P_web.pdf/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Gonfiantini, R.; Wassenaar, L.I.; Araguás-Araguás, L.J. Stable isotope fractionations in the evaporation of water: The wind effect. Hydrol. Process. 2020, 34, 3596–3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellagamba, A.W.; Berkelhammer, M.; Weber, R.; Patete, I. Suspended in sound: New constraints on isotopic fractionation of falling hydrometeors using acoustically levitated water droplets. Hydrol. Process. 2023, 37, e14804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Borehole | Vitalis I | Vitalis II | Vitalis III | Vitalis VI | Vitalis V | Vitalis VI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HsIL (m) | 0 | 13 | 20.4 | 32.5 | 47.6 | 32.2 |

| EHdL (m) | 16 | 35 | 44 | 54 | 61 | 60 |

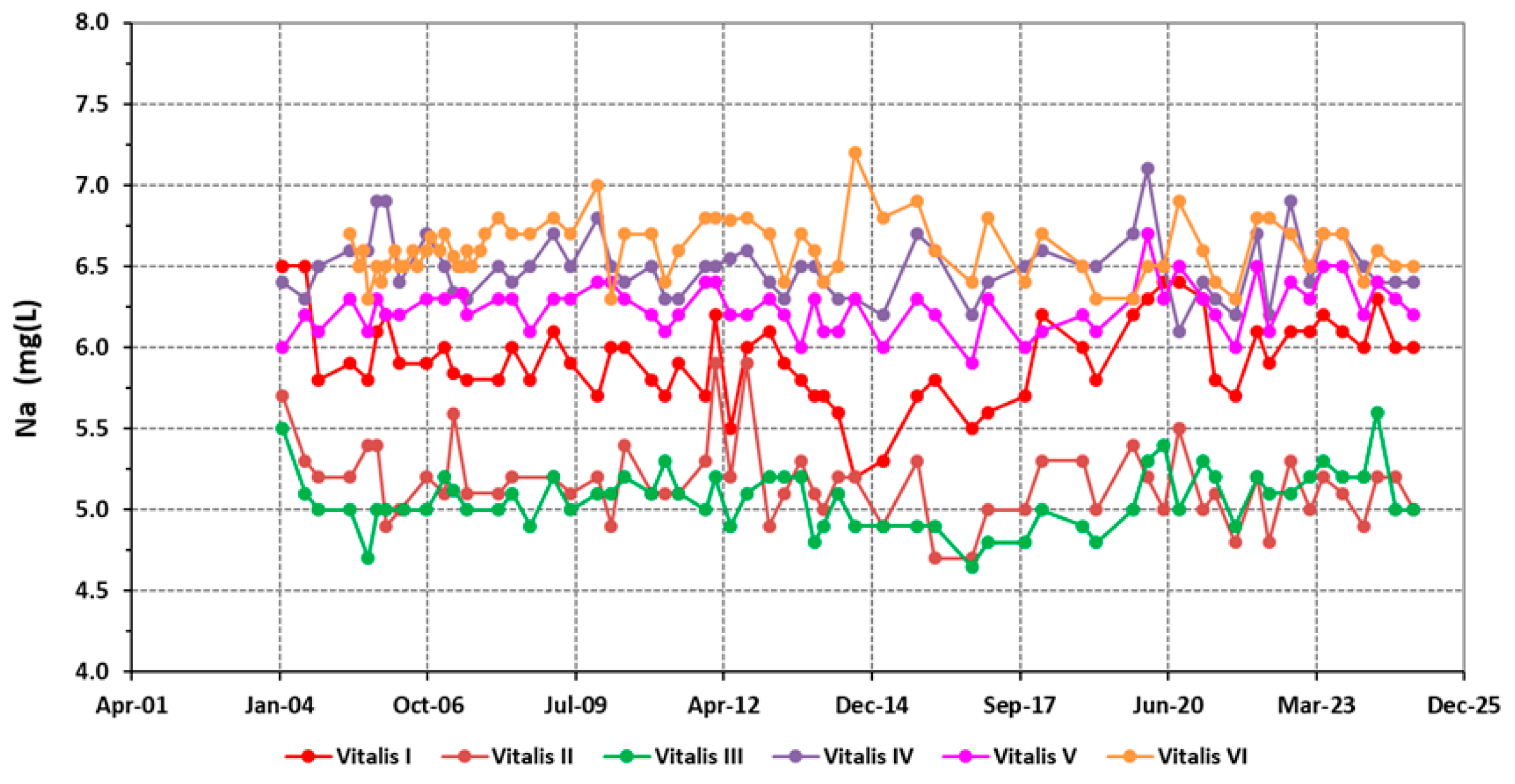

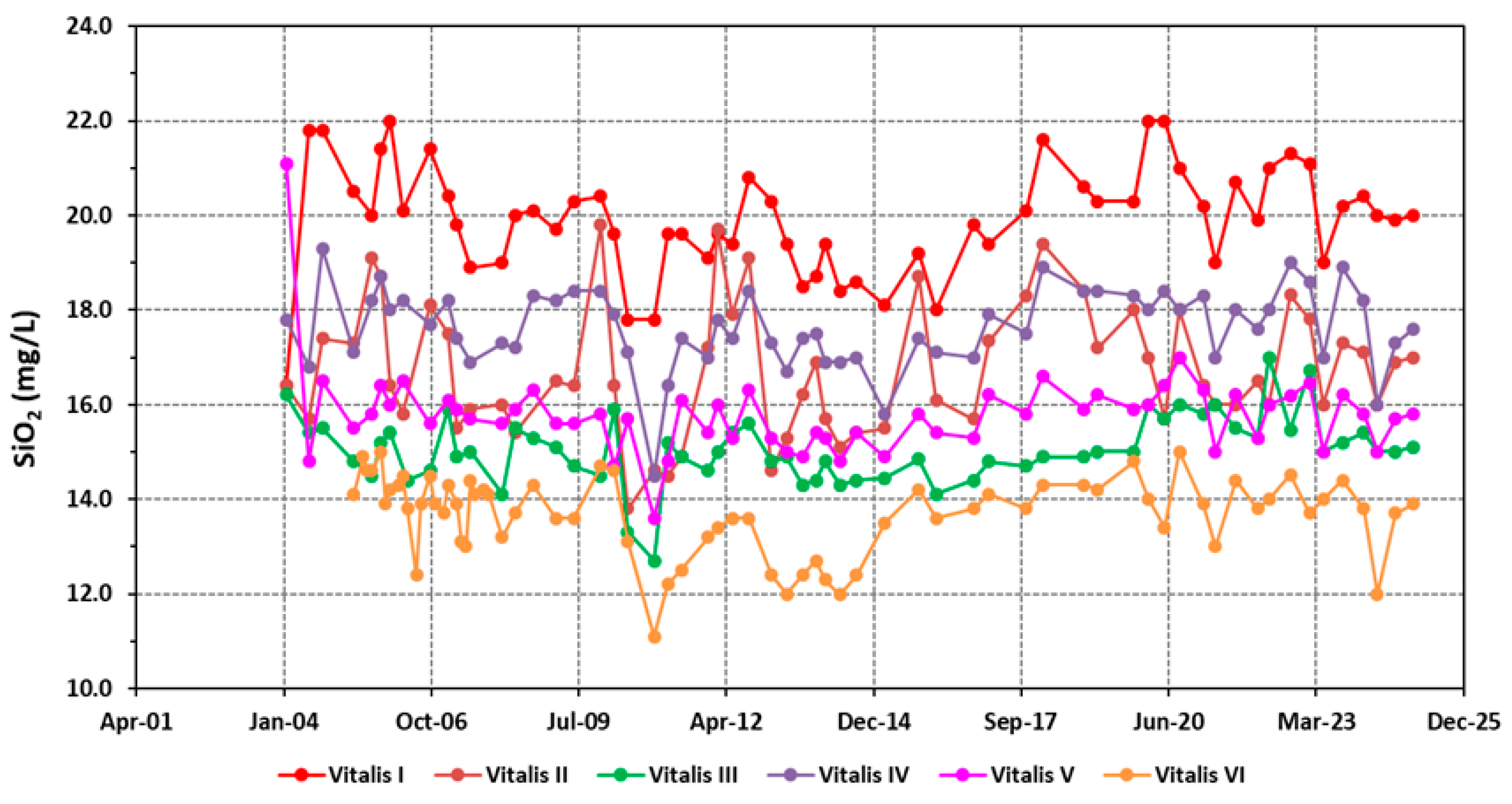

| Vitalis I (n = 60) | Vitalis II (n = 59) | Vitalis III (n = 60) | Vitalis IV (n = 61) | Vitalis V (n = 60) | Vitalis VI (n = 72) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 5.46 ± 0.08 | 5.17 ± 0.11 | 5.26 ± 0.07 | 5.22 ± 0.07 | 5.18 ± 0.08 | 5.14 ± 0.09 |

| EC | 46.34 ± 2.95 | 44.90 ± 2.69 | 42.80 ± 2.59 | 54.45 ± 3.36 | 52.97 ± 3.41 | 54.02 ± 3.03 |

| HCO3− | 6.40 ± 0.63 | 3.05 ± 0.30 | 4.35 ± 0.24 | 4.07 ± 0.30 | 4.08 ± 0.37 | 3.40 ± 0.44 |

| Cl− | 6.58 ± 0.40 | 6.97 ± 0.49 | 6.96 ± 0.25 | 8.50 ± 0.28 | 9.00 ± 0.43 | 9.69 ± 0.58 |

| SO42− | 2.79 ± 0.44 | 2.53 ± 0.39 | 2.09 ± 0.41 | 4.16 ± 0.49 | 2.74 ± 0.33 | 2.67 ± 0.63 |

| Na+ | 5.93 ± 0.27 | 5.17 ± 0.24 | 5.06 ± 0.18 | 6.50 ± 0.19 | 6.24 ± 0.15 | 6.60 ± 0.18 |

| K+ | 2.07 ± 0.08 | 2.06 ± 0.12 | 1.91 ± 0.08 | 2.35 ± 0.10 | 2.06 ± 0.10 | 1.85 ± 0.13 |

| Ca2+ | 0.81 ± 0.06 | 0.72 ± 0.07 | 0.71 ± 0.06 | 0.97 ± 0.07 | 0.99 ± 0.09 | 0.89 ± 0.07 |

| Mg2+ | 0.45 ± 0.03 | 0.45 ± 0.07 | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 0.62 ± 0.03 | 0.63 ± 0.03 | 0.59 ± 0.03 |

| SiO2 | 19.92 ± 1.15 | 16.79 ± 1.41 | 15.04 ± 0.71 | 17.66 ± 0.83 | 15.79 ± 0.91 | 13.72 ± 0.84 |

| Sampling Site | October 2023 Field Work Campaign | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| δ18O | δ2H | d | |

| Vitalis I | −6.31 | −30.8 | 19.68 |

| Vitalis II | −6.13 | −30.7 | 18.34 |

| Vitalis III | −6.13 | −31.0 | 18.04 |

| Vitalis IV | −6.31 | −32.0 | 18.48 |

| Vitalis V | −6.4 | −32.8 | 18.40 |

| Vitalis VI | −6.49 | −32.5 | 19.42 |

| AC22 | −5.90 | −33.5 | 13.70 |

| Sampling Site | pH | EC (µS/cm) | T (oC) | Eh (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitalis I | 4.82 | 49.8 | 16.1 | 96.2 |

| Vitalis II | 5.44 | 48.3 | 16.2 | 61.9 |

| Vitalis III | 4.76 | 56.5 | 15.8 | 99.4 |

| Vitalis IV | 4.69 | 58.8 | 16.2 | 103.5 |

| Vitalis V | 4.41 | 60.0 | 16.7 | 119.3 |

| Vitalis VI | 4.84 | 60.1 | 16.4 | 95.0 |

| AC22 | 4.37 | 45.6 | 15.5 | 120.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marques, J.M.; Carreira, P.M.; Antunes da Silva, M. Contribution of Hydrogeochemical and Isotope (δ2H and δ18O) Studies to Update the Conceptual Model of the Hyposaline Natural Mineral Waters of Ribeirinho and Fazenda Do Arco (Castelo de Vide, Central Portugal). Water 2025, 17, 3443. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233443

Marques JM, Carreira PM, Antunes da Silva M. Contribution of Hydrogeochemical and Isotope (δ2H and δ18O) Studies to Update the Conceptual Model of the Hyposaline Natural Mineral Waters of Ribeirinho and Fazenda Do Arco (Castelo de Vide, Central Portugal). Water. 2025; 17(23):3443. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233443

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarques, José M., Paula M. Carreira, and Manuel Antunes da Silva. 2025. "Contribution of Hydrogeochemical and Isotope (δ2H and δ18O) Studies to Update the Conceptual Model of the Hyposaline Natural Mineral Waters of Ribeirinho and Fazenda Do Arco (Castelo de Vide, Central Portugal)" Water 17, no. 23: 3443. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233443

APA StyleMarques, J. M., Carreira, P. M., & Antunes da Silva, M. (2025). Contribution of Hydrogeochemical and Isotope (δ2H and δ18O) Studies to Update the Conceptual Model of the Hyposaline Natural Mineral Waters of Ribeirinho and Fazenda Do Arco (Castelo de Vide, Central Portugal). Water, 17(23), 3443. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233443