The Application of Remote Sensing to Improve Irrigation Accounting Systems: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

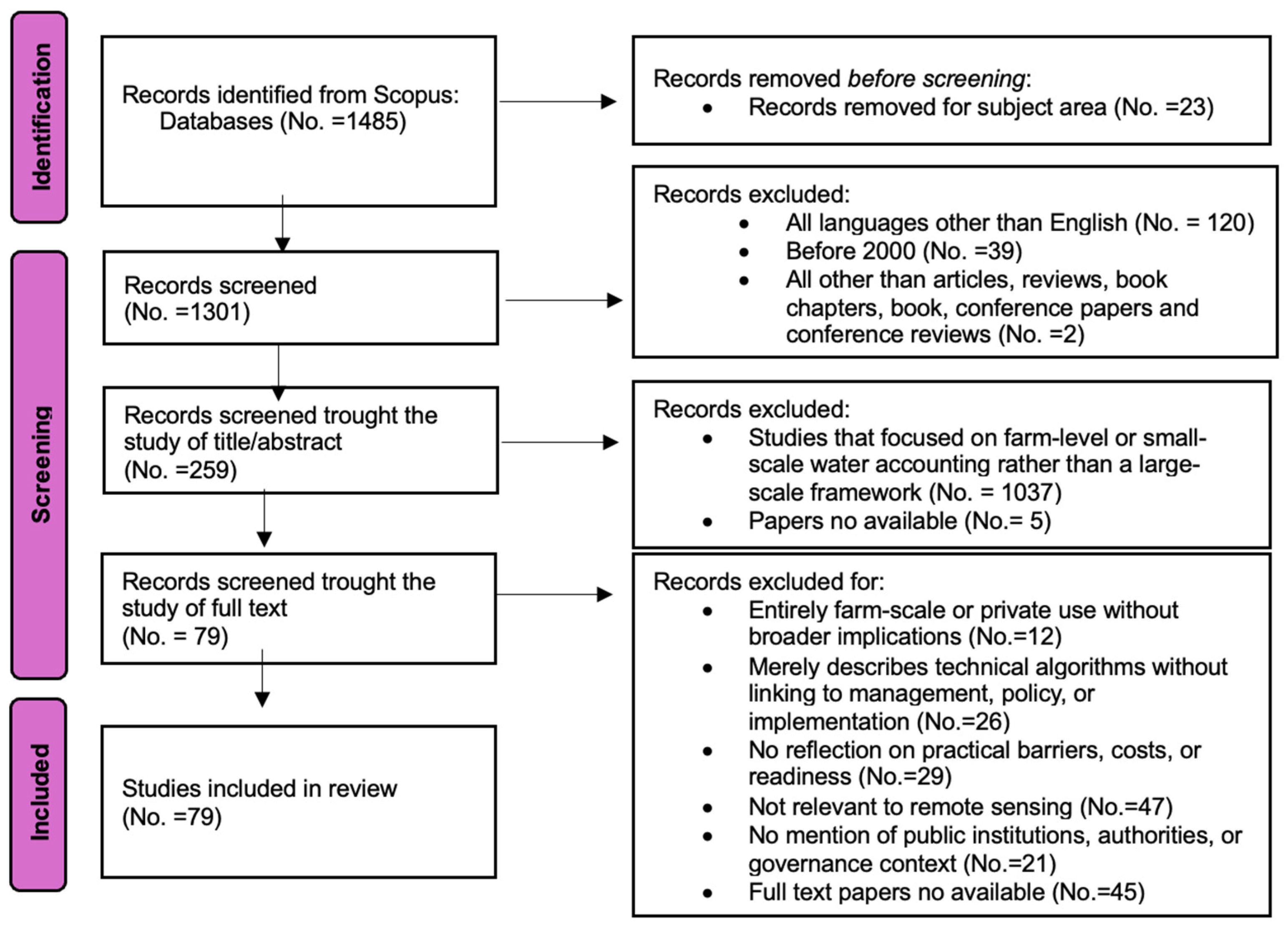

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

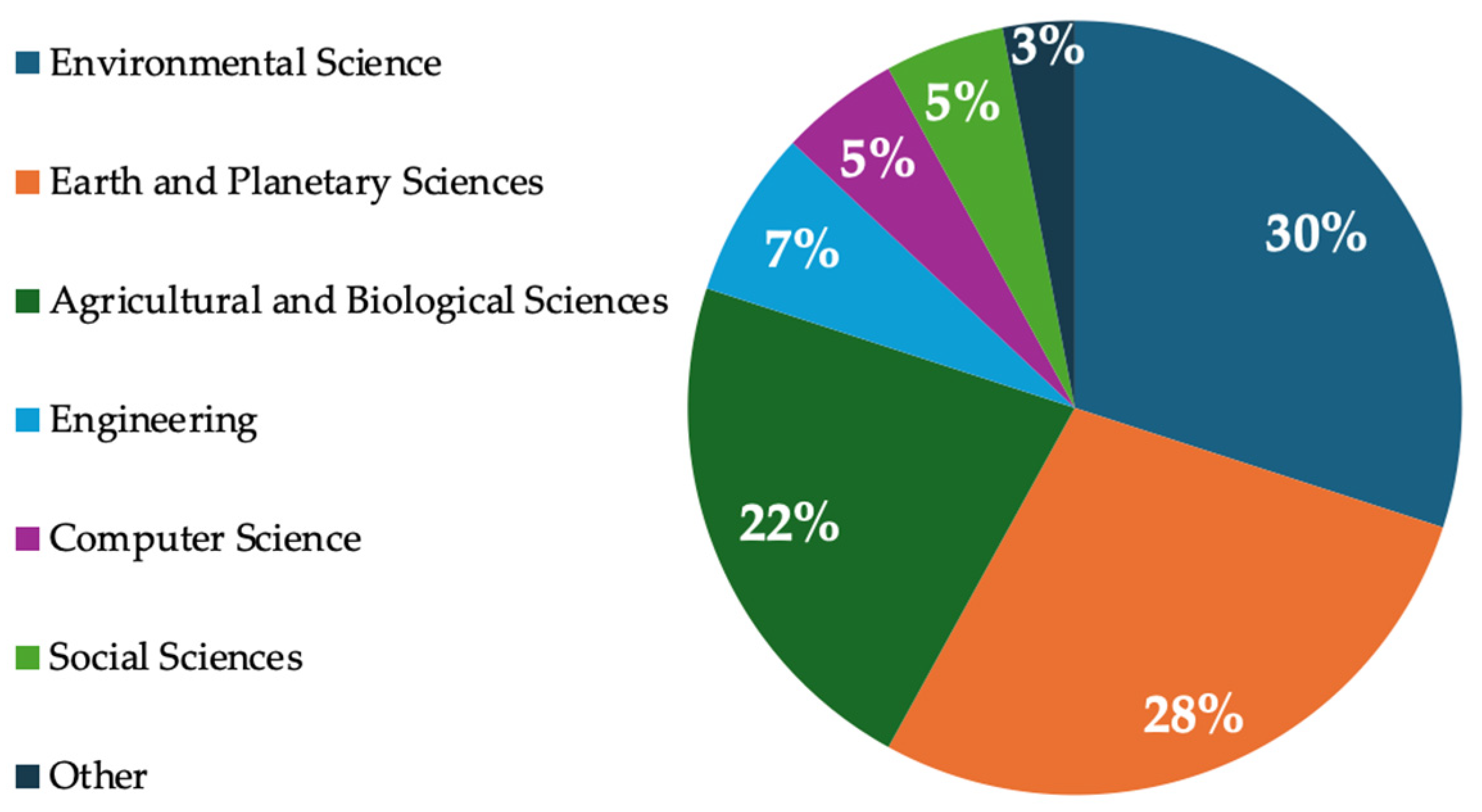

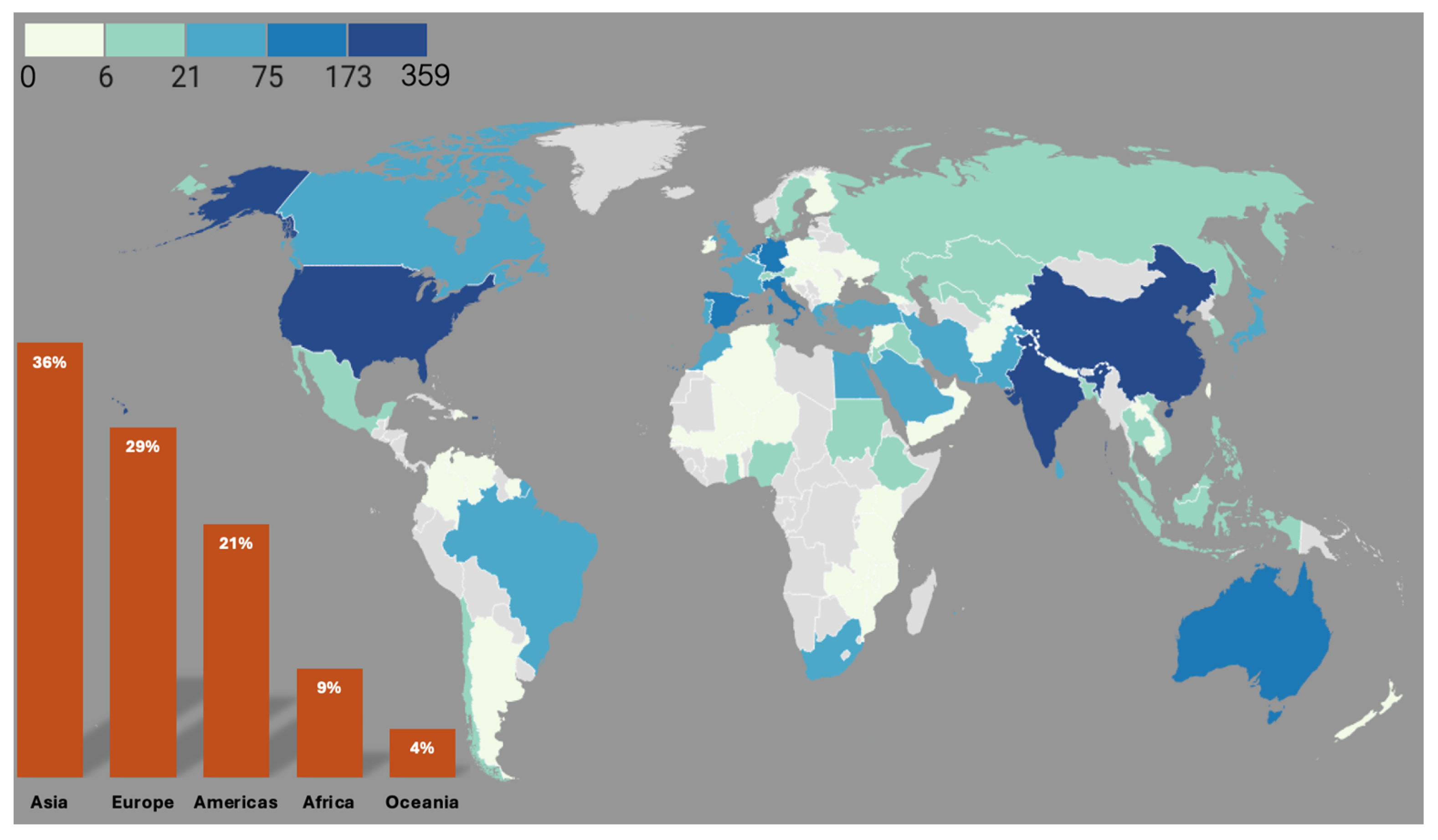

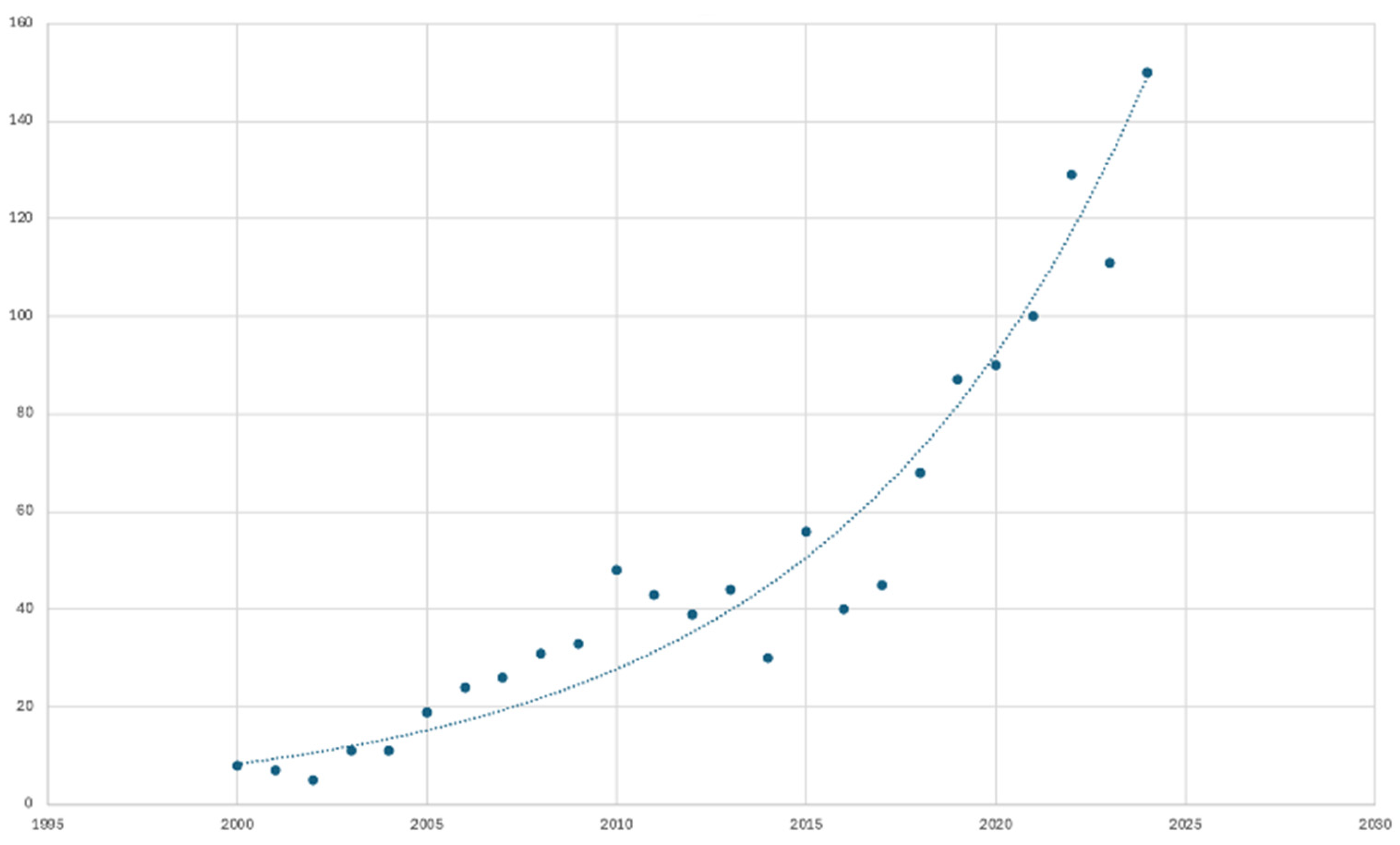

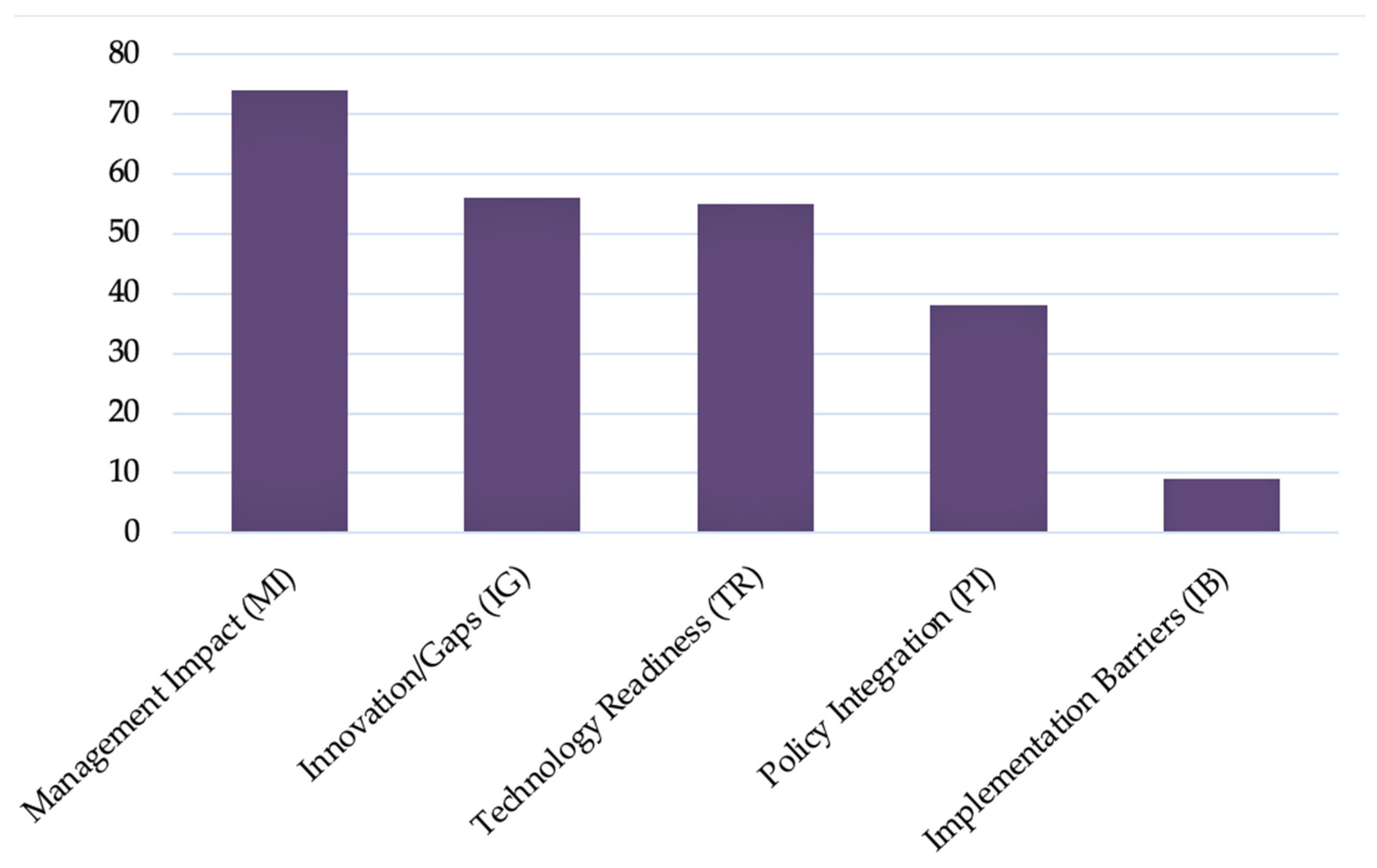

3.1. Overview

3.2. Results: The Five Classification Labels

3.2.1. Management Impact

3.2.2. Innovation/Gaps

3.2.3. Tech Readiness

3.2.4. Policy Integration

3.2.5. Implementation Barriers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CROPWAT | Crop Water |

| EO | Earth Observation |

| ET | Evapotranspiration |

| Eta | Actual Evapotranspiration |

| EU | European Union |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| IB | Implementation Barriers |

| IG | Innovation/Gaps |

| LST | Land Surface Temperature |

| MI | Management Impact |

| MOBIDIC | MOdello di Bilancio Idrologico DIstribuito e Continuo |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| PI | Policy Integration |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RS | Remote sensing |

| SEBAL | Surface Energy Balance Algorithm for Land |

| SWAT | Soil and Water Assessment Tool |

| TR | Technological Readiness |

| WA | Water Accounting |

| WA+ | Water Accounting Plus |

| WaPOR | Water Productivity through Open access of Remotely |

Appendix A

| Reference | Title | Year | Label Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| [15] | Satellite remote sensing and GIS technologies to aid sustainable management of Indian irrigation systems | 2000 | IG-MI-TR |

| [77] | Determining a better water management using a geographical technique—A case study in Egypt | 2001 | MI-PI-TR |

| [56] | Inverse modeling to quantify irrigation system characteristics and operational management | 2002 | IG-MI-TR |

| [55] | SEBAL model with remotely sensed data to improve water-resources management under actual field conditions | 2005 | IG-MI-PI-TR |

| [68] | Irrigation management from space: Towards user-friendly products | 2005 | IG-MI-PI-TR |

| [99] | Remote sensing application for estimation of irrigation water consumption in Liuyuankou irrigation system in China | 2005 | IG-MI-TR |

| [87] | Operational tools for irrigation water management based on Earth Observation: The DEMETER project | 2006 | IG-MI-PI-TR |

| [57] | Application of remote sensing techniques for water resources planning and management | 2006 | IG-MI-TR |

| [31] | Evapotranspiration from a remote sensing model for water management in an irrigation system in Venezuela | 2006 | IG-MI-TR |

| [74] | Using state-of-the-art techniques to develop water management scenarios in a lake catchment | 2007 | IG-MI-PI-TR |

| [35] | Enhancing water productivity at the irrigation system level: A geospatial hydrology application in the Yellow River Basin | 2008 | MI-PI-TR |

| [33] | A distributed package for sustainable water management: A case study in the Arno basin | 2009 | IB-MI-PI-TR |

| [53] | Irrigation water management in Latin America | 2009 | IG-MI-PI |

| [83] | Earth observation products for operational irrigation management: The PLEIADeS project | 2009 | MI-PI-TR |

| [34] | Remote sensing for irrigation water management in the semi-arid Northeast of Brazil | 2009 | IB-MI-PI-TR |

| [60] | Water resources management for Virudhunagar district using remote sensing and GIS | 2010 | MI-TR |

| [47] | Current status and perspectives for the estimation of crop water requirements from earth observation | 2010 | MI-PI-TR |

| [71] | Earth Observation products for operational irrigation management in the context of the PLEIADeS project | 2010 | MI-PI-TR |

| [16] | Remote Sensing and Economic Indicators for Supporting Water Resources Management Decisions | 2010 | IG-MI-PI-TR |

| [75] | Operational monitoring of daily crop water requirements at the regional scale with time series of satellite data | 2010 | MI-PI-TR |

| [17] | Calibration of a distributed irrigation water management model using remotely sensed evapotranspiration rates and groundwater heads | 2011 | IG-MI-TR |

| [62] | Development of a satellite-based multi-scale land use classification system for land and water management in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan | 2011 | IG-MI-TR |

| [86] | Smart management and irrigation demand monitoring in Cyprus, using remote sensing and water resources simulation and optimization | 2011 | IG-MI-PI-TR |

| [82] | Water balance of irrigated areas: a remote sensing approach | 2011 | IG-MI-PI-TR |

| [93] | Improving water governance in Central Asia through application of data management tools | 2012 | IB-MI-PI |

| [72] | Satellite irrigation management support with the terrestrial observation and prediction system: A framework for integration of satellite and surface observations to support improvements in agricultural water resource management | 2012 | IG-MI-PI-TR |

| [95] | Remote sensing applications for planning irrigation management. The use of SEBAL methodology for estimating crop evapotranspiration in Cyprus | 2012 | IG-MI-TR |

| [67] | Remote sensing applications in water resources | 2013 | IG-MI-TR |

| [66] | Evapotranspiration estimates from remote sensing for irrigation water management | 2013 | IG-MI-PI |

| [52] | Monitoring and determination of irrigation demand in Cyprus | 2013 | IG-MI-PI |

| [13] | An innovative remote sensing based reference evapotranspiration method to support irrigation water management under semi-arid conditions | 2014 | IG-MI-TR |

| [59] | Development of irrigation water management model for reducing drought severity using remotely sensed soil moisture footprints | 2014 | IG-MI-TR |

| [58] | Remote sensing and district database programs for irrigation monitoring and evaluation at a regional scale | 2015 | IG-MI-TR |

| [44] | Water balance indicators from MODIS images and agrometeorological data in Minas Gerais state, Brazil | 2015 | IG-MI-TR |

| [84] | Temporal change in land use by irrigation source in Tamil Nadu and management implications | 2015 | IG-MI-TR |

| [38] | Development of a district information system for water management planning and strategic decision making | 2015 | MI-PI-TR |

| [85] | Hydro-economic analysis of groundwater pumping for irrigated agriculture in California’s Central Valley, USA [Analyse hydro-économique des pompages d’eaux souterraines pour l’agriculture irriguée dans la vallée Centrale en Californie, Etats Unis d’Amérique] | 2015 | MI-PI-TR |

| [46] | Estimation of crop water requirements using remote sensing for operational water resources management | 2015 | IG-MI-TR |

| [40] | Satellite-based irrigation advisory services: A common tool for different experiences from Europe to Australia | 2015 | IG-MI-TR |

| [90] | Policies, Land Use, and Water Resource Management in an Arid Oasis Ecosystem | 2015 | IB-MI-PI |

| [92] | Geospatial techniques for improved water management in Jordan | 2016 | IB-IG-MI |

| [42] | Assessing irrigated agriculture’s surface water and groundwater consumption by combining satellite remote sensing and hydrologic modelling | 2016 | IG-MI-TR |

| [41] | Sustainable Agricultural Water Management in Pinios River Basin Using Remote Sensing and Hydrologic Modeling | 2016 | IG-MI-TR |

| [31] | Implications of non-sustainable agricultural water policies for the water-food nexus in large-scale irrigation systems: A remote sensing approach | 2017 | IB-MI-PI-TR |

| [96] | Remote sensing for crop water management: From ET modelling to services for the end users | 2017 | IG-MI-TR |

| [89] | Remote sensing-based water accounting to support governance for groundwater management for irrigation in la Mancha oriental aquifer, Spain | 2017 | IB-MI-PI-TR |

| [43] | Remote sensing-based soil water balance for irrigation water accounting at the Spanish Iberian Peninsula | 2018 | IG-MI-PI-TR |

| [37] | Validation and verification of lawful water use in South Africa: An overview of the process in the KwaZulu-Natal Province | 2018 | MI-PI-TR |

| [20] | HidroMap: A new tool for irrigation monitoring and management using free satellite imagery | 2018 | IG-MI-TR |

| [76] | Application of a remote sensing-based soil water balance for the accounting of groundwater abstractions in large irrigation areas | 2019 | MI |

| [49] | Basin-wide water accounting based on modified SWAT model and WA+ framework for better policy making | 2020 | IG-MI-PI |

| [21] | Satellite-Based Monitoring of Irrigation Water Use: Assessing Measurement Errors and Their Implications for Agricultural Water Management Policy | 2020 | IG-MI |

| [26] | Evaluation of remote sensing-based irrigation water accounting at river basin district management scale | 2020 | IG-MI-PI-TR |

| [65] | Remote sensing–based soil water balance for irrigation water accounting at plot and water user association management scale | 2020 | IG-MI-TR |

| [81] | Between regulation and targeted expropriation: Rural-to-urban groundwater reallocation in Jordan | 2020 | IG-MI-PI |

| [78] | A Methodological Approach for Irrigation Detection in the Frame of Common Agricultural Policy Checks by Monitoring | 2020 | IG-MI-PI-TR |

| [80] | Towards a sustainable and adaptive groundwater management: Lessons from the Benalup Aquifer (Southern Spain) | 2020 | IG-MI-PI |

| [30] | Remote sensing’s role in improving transboundary water regulation and compliance: The Murray-Darling Basin, Australia | 2021 | MI-PI |

| [50] | Combining Remote Sensing and Crop Models to Assess the Sustainability of Stakeholder-Driven Groundwater Management in the US High Plains Aquifer | 2021 | IG-MI |

| [54] | Enhanced Water Management for Muang Fai Irrigation Systems through Remote Sensing and SWOT Analysis | 2021 | IG-MI |

| [73] | Mapping Impact of Farmer’s Organisation on the Equity of Water and Land Productivity: Evidence from Pakistan | 2022 | IB-MI-PI |

| [63] | Estimating the economic value and economic return of irrigation water as a sustainable water resource management mechanism | 2022 | IG-MI-TR |

| [61] | Water and productivity accounting using WA+ framework for sustainable water resources management: Case study of northwestern Iran | 2022 | IG-MI-TR |

| [45] | Viewpoint: Irrigation water management in a space age | 2022 | IG-MI |

| [27] | An interval multi-objective fuzzy-interval credibility-constrained nonlinear programming model for balancing agricultural and ecological water management | 2022 | IG-MI-TR |

| [64] | Tracking spatiotemporal dynamics of irrigated croplands in China from 2000 to 2019 through the synergy of remote sensing, statistics, and historical irrigation datasets | 2022 | IG-MI-TR |

| [19] | Remote Sensing for Agricultural Water Management in Jordan | 2023 | IG-TR |

| [70] | Evaluating Performance of Community-based Irrigation Schemes Using Remote-sensing Technologies to Enhance Sustainable Irrigation Water Management | 2023 | IG-MI-TR |

| [39] | Methodologies for Water Accounting at the Collective Irrigation System Scale Aiming at Optimizing Water Productivity | 2023 | IG-MI-TR |

| [69] | Quantifying irrigation water demand and supply gap using remote sensing and GIS in Multan, Pakistan | 2023 | MI-TR |

| [36] | Effects of Yellow River Water Management Policies on Annual Irrigation Water Usage from Canals and Groundwater in Yucheng City, China | 2023 | IG-MI-PI-TR |

| [91] | Water Accounting Plus: limitations and opportunities for supporting integrated water resources management in the Middle East and North Africa | 2024 | IB |

| [48] | Analysis and forecast of crop water demand in irrigation districts across the eastern part of the Ebro river basin (Catalonia, Spain): estimation of evapotranspiration through copernicus-based inputs | 2024 | IG-MI |

| [51] | Impact of ET and biomass model choices on economic irrigation water productivity in water-scarce basins | 2024 | IG |

| [28] | Toward field-scale groundwater pumping and improved groundwater management using remote sensing and climate data | 2024 | MI |

| [94] | Socioeconomic impact of agricultural water reallocation policies in the Upper Litani Basin (Lebanon): a remote sensing and microeconomic ensemble forecasting approach | 2024 | IG-PI |

| [79] | Geospatially Informed Water Pricing for Sustainability: A Mixed Methods Approach to the Increasing Block Tariff Model for Groundwater Management in Arid Regions of Northwest Bangladesh | 2024 | MI-PI |

| [29] | Comprehensive model for sustainable water resource management in Southern Algeria: integrating remote sensing and WEAP model | 2024 | IG-MI-TR |

| [88] | Estimating irrigation water use from remotely sensed evapotranspiration data: Accuracy and uncertainties at field, water right, and regional scales | 2024 | IG-PI |

References

- Wang, X.; Shao, J.; Van Steenbergen, F.; Zhang, Q. Implementing the Prepaid Smart Meter System for Irrigated Groundwater Production in Northern China: Status and Problems. Water 2017, 9, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molle, F.; Closas, A. Groundwater Metering: Revisiting a Ubiquitous ‘Best Practice’. Hydrogeol. J. 2021, 29, 1857–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döll, P.; Siebert, S. Global Modeling of Irrigation Water Requirements. Water Resour. Res. 2002, 38, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mialyk, O.; Booij, M.J.; Schyns, J.F.; Berger, M. Evolution of Global Water Footprints of Crop Production in 1990–2019. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 114015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroepsch, A.C. Monitored but Not Metered: How Groundwater Pumping Has Evaded Accounting (and Accountability) in the Western United States. Water Altern. 2024, 17, 348–368. [Google Scholar]

- Hanemann, M.; Young, M. Water Rights Reform and Water Marketing: Australia vs the US West. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2020, 36, 108–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochford, L.M.; Ordens, C.M.; Bulovic, N.; McIntyre, N. Voluntary Metering of Rural Groundwater Extractions: Understanding and Resolving the Challenges. Hydrogeol. J. 2022, 30, 2251–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viaggi, D.; Raggi, M.; Bartolini, F.; Gallerani, V. Designing contracts for irrigation water under asymmetric information: Are simple pricing mechanisms enough? Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Stefano, L.; Lopez-Gunn, E. Unauthorized Groundwater Use: Institutional, Social and Ethical Considerations. Water Policy 2012, 14, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursitti, A.; Giannoccaro, G.; Prosperi, M.; De Meo, E.; De Gennaro, B.C. The Magnitude and Cost of Groundwater Metering and Control in Agriculture. Water 2018, 10, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, T.; Pérez-Blanco, C.D.; Schmidt, G. Monitoring Agricultural Water Use: Challenges and Solutions for Sustainable Water Management. In Improving Water Management in Agriculture; Knox, J., Ed.; Burleigh Dodds Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molle, F.; Closas, A. Why Is State-Centered Groundwater Governance Largely Ineffective? A Review. WIREs Water 2020, 7, e1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Blanco, M.; Lorite, I.J.; Santos, C. An Innovative Remote Sensing Based Reference Evapotranspiration Method to Support Irrigation Water Management under Semi-Arid Conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 131, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, G.; Arduini, S.; Uyar, H.; Psiroukis, V.; Kasimati, A.; Fountas, S. Economic and Environmental Benefits of Digital Agricultural Technologies in Crop Production: A Review. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 8, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintapalli, S.M.; Raju, P.V.; Abdul Hakeem, K.; Jonna, S. Satellite Remote Sensing and GIS Technologies to Aid Sustainable Management of Indian Irrigation Systems. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2000, 33, 264–271. [Google Scholar]

- Hellegers, P.J.G.J.; Soppe, R.; Perry, C.J.; Bastiaanssen, W.G.M. Remote Sensing and Economic Indicators for Supporting Water Resources Management Decisions. Water Resour. Manag. 2010, 24, 2419–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhorar, R.K.; Smit, A.A.M.F.R.; Bastiaanssen, W.G.M.; Roest, C.W.J. Calibration of a Distributed Irrigation Water Management Model Using Remotely Sensed Evapotranspiration Rates and Groundwater Heads. Irrig. Drain. 2011, 60, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Daniel, Á.; Garrido-Rubio, J.; Molina-Medina, A.J.; Gil-García, L.; Sapino, F.; González-Piqueras, J.; Pérez-Blanco, C.D. Sensitivity of Water Reallocation Performance Assessments to Water Use Data. Water Resour. Econ. 2024, 48, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bakri, J.T.; D’Urso, G.; Calera, A.; Abdalhaq, E.; Altarawneh, M.; Margane, A. Remote Sensing for Agricultural Water Management in Jordan. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedelobo, L.; Ortega-Terol, D.; Del Pozo, S.; Hernández-López, D.; Ballesteros, R.; Moreno, M.A.; Molina, J.-L.; González-Aguilera, D. HidroMap: A New Tool for Irrigation Monitoring and Management Using Free Satellite Imagery. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, T.; Mieno, T.; Brozović, N. Satellite-Based Monitoring of Irrigation Water Use: Assessing Measurement Errors and Their Implications for Agricultural Water Management Policy. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2020WR028378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-López, C.; Ben Abdallah, S.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Hassoun, A.; Trollman, H.; Jagtap, S.; Gupta, S.; Aït-Kaddour, A.; Makmuang, S.; Carmona-Torres, C. Digital Technologies for Water Use and Management in Agriculture: Recent Applications and Future Outlook. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 309, 109347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Dugo, V.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. Assessing the Impact of Measurement Errors in the Calculation of CWSI for Characterizing the Water Status of Several Crop Species. Irrig. Sci. 2024, 42, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gunn, E.; Rica, M.; Zugasti, I.; Hernaez, O.; Pulido-Velazquez, M.; Sanchis-Ibor, C. Use of the Delphi Method to Assess the Potential Role of Enhanced Information Systems in Mediterranean Groundwater Management and Governance. Water Policy 2024, 26, 1183–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Rubio, J.; Calera, A.; Arellano, I.; Belmonte, M.; Fraile, L.; Ortega, T.; Bravo, R.; González-Piqueras, J. Evaluation of Remote Sensing-Based Irrigation Water Accounting at River Basin District Management Scale. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Zhang, C.; Guo, S.; Sun, H.; Du, J.; Guo, P. An Interval Multi-Objective Fuzzy-Interval Credibility-Constrained Nonlinear Programming Model for Balancing Agricultural and Ecological Water Management. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2022, 245, 103958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, T.J.; Majumdar, S.; Huntington, J.L.; Pearson, C.; Bromley, M.; Minor, B.A.; ReVelle, P.; Morton, C.G.; Sueki, S.; Beamer, J.P.; et al. Toward Field-Scale Groundwater Pumping and Improved Groundwater Management Using Remote Sensing and Climate Data. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 302, 109000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegait, R.; Bouznad, I.E.; Remini, B.; Bengusmia, D.; Ajia, F.; Guastaldi, E.; Lopane, N.; Petrone, D. Comprehensive Model for Sustainable Water Resource Management in Southern Algeria: Integrating Remote Sensing and WEAP Model. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 10, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretreger, D.; Yeo, I.-Y.; Kuczera, G.; Hancock, G. Remote Sensing’s Role in Improving Transboundary Water Regulation and Compliance: The Murray-Darling Basin, Australia. J. Hydrol. X 2021, 13, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trezza, R. Evapotranspiration from a Remote Sensing Model for Water Management in an Irrigation System in Venezuela. Interciencia 2006, 31, 417–423. [Google Scholar]

- Al Zayed, I.S.; Elagib, N.A. Implications of Non-Sustainable Agricultural Water Policies for the Water-Food Nexus in Large-Scale Irrigation Systems: A Remote Sensing Approach. Adv. Water Resour. 2017, 110, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, F.; Menduni, G.; Mazzanti, B. A Distributed Package for Sustainable Water Management: A Case Study in the Arno Basin. In Proceedings of the Role of Hydrology in Water Resources Management Symposium, Capri, Italy, 13–16 October 2008; IAHS Press: Wallingford, UK, 2009; pp. 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Folhes, M.T.; Rennó, C.D.; Soares, J.V. Remote Sensing for Irrigation Water Management in the Semi-Arid Northeast of Brazil. Agric. Water Manag. 2009, 96, 1398–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Hafeez, M.M.; Rana, T.; Mushtaq, S. Enhancing Water Productivity at the Irrigation System Level: A Geospatial Hydrology Application in the Yellow River Basin. J. Arid. Environ. 2008, 72, 1046–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Jing, K.; Li, X.; Song, X.; Zhao, C.; Du, S. Effects of Yellow River Water Management Policies on Annual Irrigation Water Usage from Canals and Groundwater in Yucheng City, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapangaziwiri, E.; Mwenge Kahinda, J.; Dzikiti, S.; Ramoelo, A.; Cho, M.; Mathieu, R.; Naidoo, M.; Seetal, A.; Pienaar, H. Validation and Verification of Lawful Water Use in South Africa: An Overview of the Process in the KwaZulu-Natal Province. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2018, 105, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukas, A.; Tzabiras, J.; Spiliotopoulos, M.; Kokkinos, K.; Fafoutis, C.; Mylopoulos, N. Development of a district information system for water management planning and strategic decision making. In Proceedings of the SPIE, the International Society for Optical Engineering, Paphos, Cyprus, 19 June 2015; Volume 9535, p. 95351L. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Rolim, J.; Paredes, P.; Cameira, M.D.R. Methodologies for Water Accounting at the Collective Irrigation System Scale Aiming at Optimizing Water Productivity. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuolo, F.; D’Urso, G.; De Michele, C.; Bianchi, B.; Cutting, M. Satellite-Based Irrigation Advisory Services: A Common Tool for Different Experiences from Europe to Australia. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 147, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomas, A.; Dagalaki, V.; Panagopoulos, Y.; Konsta, D.; Mimikou, M. Sustainable Agricultural Water Management in Pinios River Basin Using Remote Sensing and Hydrologic Modeling. Procedia Eng. 2016, 162, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Arancibia, J.L.; Mainuddin, M.; Kirby, J.M.; Chiew, F.H.S.; McVicar, T.R.; Vaze, J. Assessing Irrigated Agriculture’s Surface Water and Groundwater Consumption by Combining Satellite Remote Sensing and Hydrologic Modelling. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 542, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Rubio, J.; Calera Belmonte, A.; Fraile Enguita, L.; Arellano Alcázar, I.; Belmonte Mancebo, M.; Campos Rodríguez, I.; Bravo Rubio, R. Remote Sensing-Based Soil Water Balance for Irrigation Water Accounting at the Spanish Iberian Peninsula. Proc. IAHS 2018, 380, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Teixeira, A.H.; Leivas, J.F.; Andrade, R.G.; Victoria, D.D.C.; Bolfe, E.L.; Da Silva, G.B.S. Water balance indicators from MODIS images and agrometeorological data in Minas Gerais state, Brazil. In Proceedings of the SPIE, the International Society for Optical Engineering, Toulouse, France, 14 October 2015; Volume 9637, p. 96370O. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, M.; Awan, U.K. Viewpoint: Irrigation Water Management in a Space Age. Irrig. Drain. 2022, 71, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliades, L.; Spiliotopoulos, M.; Tzabiras, J.; Loukas, A.; Mylopoulos, N. Estimation of crop water requirements using remote sensing for operational water resources management. In Proceedings of the SPIE, the International Society for Optical Engineering, Paphos, Cyprus, 19 June 2015; Volume 9535, p. 95351B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, G. Current Status and Perspectives for the Estimation of Crop Water Requirements from Earth Observation. Ital. J. Agron. 2010, 5, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellvert, J.; Pamies-Sans, M.; Quintana-Seguí, P.; Casadesús, J. Analysis and Forecast of Crop Water Demand in Irrigation Districts across the Eastern Part of the Ebro River Basin (Catalonia, Spain): Estimation of Evapotranspiration through Copernicus-Based Inputs. Irrig. Sci. 2025, 43, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delavar, M.; Morid, S.; Morid, R.; Farokhnia, A.; Babaeian, F.; Srinivasan, R.; Karimi, P. Basin-Wide Water Accounting Based on Modified SWAT Model and WA+ Framework for Better Policy Making. J. Hydrol. 2020, 585, 124762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deines, J.M.; Kendall, A.D.; Butler, J.J.; Basso, B.; Hyndman, D.W. Combining remote sensing and crop models to assess the sustainability of Stakeholder-Driven groundwater management in the US High Plains Aquifer. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR027756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazimeh, R.; Jaafar, H. Impact of ET and Biomass Model Choices on Economic Irrigation Water Productivity in Water-Scarce Basins. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 292, 108651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadavid, G.; Michailidis, A. Monitoring and Determination of Irrigation Demand in Cyprus. Glob. NEST J. 2013, 15, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, A.S.; Trezza, R.; Holzapfel, E.; Lorite, I.; Paz, V.P.S. Irrigation Water Management in Latin America. Chilean J. Agric. Res. 2009, 69, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supriyasilp, T.; Pongput, K.; Boonyanupong, S.; Suwanlertcharoen, T. Enhanced Water Management for Muang Fai Irrigation Systems through Remote Sensing and SWOT Analysis. Water Resour. Manag. 2021, 35, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaanssen, W.G.M.; Noordman, E.J.M.; Pelgrum, H.; Davids, G.; Thoreson, B.P.; Allen, R.G. SEBAL Model with Remotely Sensed Data to Improve Water-Resources Management under Actual Field Conditions. J. Irrig. Drain Eng. 2005, 131, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ines, A.V.M.; Droogers, P. Inverse Modeling to Quantify Irrigation System Characteristics and Operational Management. Irrig. Drain. Syst. 2002, 16, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, A.; Shehzad, A.; Asghar, M. Application of Remote Sensing Techniques for Water Resources Planning and Management. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference on Advances in Space Technologies, ICAST, Islamabad, Pakistan, 2–3 September 2006; pp. 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalghaf, I.; Elhaddad, A.; García, L.A.; Lecina, S. Remote Sensing and District Database Programs for Irrigation Monitoring and Evaluation at a Regional Scale. J. Irrig. Drain Eng. 2015, 141, 4015016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Jung, Y. Development of Irrigation Water Management Model for Reducing Drought Severity Using Remotely Sensed Soil Moisture Footprints. J. Irrig. Drain Eng. 2014, 140, 4014021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuradha, C.T.; Prabhavathy, S. Water Resources Management for Virudhunagar District Using Remote Sensing and GIS. Int. J. Earth Sci. Eng. 2010, 3, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbanpour, A.K.; Afshar, A.; Hessels, T.; Duan, Z. Water and Productivity Accounting Using WA+ Framework for Sustainable Water Resources Management: Case Study of Northwestern Iran. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2022, 128, 103245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löw, F.; Michel, U.; Dech, S.; Conrad, C. Development of a satellite-based multi-scale land use classification system for land and water management in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. In Proceedings of the SPIE, the International Society for Optical Engineering, Prague, Czech Republic, 26 October 2011; Volume 8181, p. 81811K. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashe, T.; Alamirew, T.; Dejen, Z.A. Estimating the Economic Value and Economic Return of Irrigation Water as a Sustainable Water Resource Management Mechanism. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 8, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Dong, J.; Zuo, L.; Ge, Q. Tracking Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Irrigated Croplands in China from 2000 to 2019 through the Synergy of Remote Sensing, Statistics, and Historical Irrigation Datasets. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 263, 107458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Rubio, J.; González-Piqueras, J.; Campos, I.; Osann, A.; González-Gómez, L.; Calera, A. Remote Sensing–Based Soil Water Balance for Irrigation Water Accounting at Plot and Water User Association Management Scale. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 238, 106236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.C.; Allen, R.G.; Brazil, L.E.; Burkhalter, J.P.; Polly, J.S. Evapotranspiration Estimates from Remote Sensing for Irrigation Water Management. In Satellite-Based Applications on Climate Change; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.N.; Reshmidevi, T. Remote sensing applications in water resources. J. Indian Inst. Sci. 2013, 93, 163–188. [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte, A.C.; Jochum, A.M.; GarcÍa, A.C.; Rodríguez, A.M.; Fuster, P.L. Irrigation Management from Space: Towards User-Friendly Products. Irrig. Drain. Syst. 2005, 19, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, M.; Farid, H.U.; Khan, Z.M.; Anjum, M.N.; Ahmad, A.; Mubeen, M. Quantifying Irrigation Water Demand and Supply Gap Using Remote Sensing and GIS in Multan, Pakistan. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashe, T.; Alamirew, T.; Dejen, Z.A. Evaluating Performance of Community-Based Irrigation Schemes Using Remote-Sensing Technologies to Enhance Sustainable Irrigation Water Management. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2023, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, G.; Richter, K.; Calera, A.; Osann, M.A.; Escadafal, R.; Garatuza-Pajan, J.; Hanich, L.; Perdigão, A.; Tapia, J.B.; Vuolo, F. Earth Observation Products for Operational Irrigation Management in the Context of the PLEIADeS Project. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 98, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton, F.S.; Johnson, L.F.; Lund, C.P.; Pierce, L.L.; Michaelis, A.R.; Hiatt, S.H.; Guzman, A.; Adhikari, D.D.; Purdy, A.J.; Rosevelt, C.; et al. Satellite Irrigation Management Support with the Terrestrial Observation and Prediction System: A Framework for Integration of Satellite and Surface Observations to Support Improvements in Agricultural Water Resource Management. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2012, 5, 1709–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfan, M. Mapping Impact of Farmer’s Organisation on the Equity of Water and Land Productivity: Evidence from Pakistan. Pak. Dev. Rev. 2022, 61, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, E.; Zacharias, I. Using State-of-the-Art Techniques to Develop Water Management Scenarios in a Lake Catchment. Hydrol. Res. 2007, 38, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Rampini, A.; Bocchi, S.; Boschetti, M. Operational Monitoring of Daily Crop Water Requirements at the Regional Scale with Time Series of Satellite Data. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2010, 136, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Rubio, J.; Sanz, D.; González-Piqueras, J.; Calera, A. Application of a Remote Sensing-Based Soil Water Balance for the Accounting of Groundwater Abstractions in Large Irrigation Areas. Irrig. Sci. 2019, 37, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairy, W.M.; Abdel-Dayem, M.S.; Coleman, T.L. Determining Better Water Management Using a Geographical Technique: A Case Study in Egypt. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2001, Scanning the Present and Resolving the Future, IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Sydney, Ausralia, 9–13 July 2001; Volume 1, pp. 453–455. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes-Gómez, V.; Gutiérrez, A.; Del Blanco, V.; Nafría, D.A. A Methodological Approach for Irrigation Detection in the Frame of Common Agricultural Policy Checks by Monitoring. Agronomy 2020, 10, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuvo, R.M.; Chowdhury, R.R.; Chakroborty, S.; Das, A.; Kafy, A.A.; Altuwaijri, H.A.; Rahman, M.T. Geospatially Informed Water Pricing for Sustainability: A Mixed Methods Approach to the Increasing Block Tariff Model for Groundwater Management in Arid Regions of Northwest Bangladesh. Water 2024, 16, 3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez-Nicolás, M.; García-López, S.; Ruiz-Ortiz, V.; Sánchez-Bellón, Á. Towards a Sustainable and Adaptive Groundwater Management: Lessons from the Benalup Aquifer (Southern Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 5215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liptrot, T.; Hussein, H. Between Regulation and Targeted Expropriation: Rural-to-Urban Groundwater Reallocation in Jordan. Water Altern. 2020, 13, 467–485. [Google Scholar]

- Taghvaeian, S.; Neale, C.M.U. Water Balance of Irrigated Areas: A Remote Sensing Approach. Hydrol. Process. 2011, 25, 4132–4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, G.; Vuolo, F.; Richter, K.; Belmonte, A.C.; Osann, M.A. Earth observation products for operational irrigation management: The PLEIADeS project. In Proceedings of the SPIE, the International Society for Optical Engineering, Berlin, Germany, 18 September 2009; Volume 7472, p. 74720D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumma, M.K.; Kajisa, K.; Mohammed, I.A.; Whitbread, A.M.; Nelson, A.; Rala, A.; Palanisami, K. Temporal Change in Land Use by Irrigation Source in Tamil Nadu and Management Implications. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Medellín-Azuara, J.; MacEwan, D.; Howitt, R.E.; Koruakos, G.; Dogrul, E.C.; Brush, C.F.; Kadir, T.N.; Harter, T.; Melton, F.; Lund, J.R. Hydro-Economic Analysis of Groundwater Pumping for Irrigated Agriculture in California’s Central Valley, USA. Hydrogeol. J. 2015, 23, 1205–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadavid, G.; Hadjimitsis, D.; Fedra, K.; Michaelides, S. Smart Management and Irrigation Demand Monitoring in Cyprus, Using Remote Sensing and Water Resources Simulation and Optimization. Adv. Geosci. 2011, 30, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Calera, A.; Jochum, M.A.O. Operational tools for irrigation water management based on Earth observation: The DEMETER project. In Proceedings of the SPIE, the International Society for Optical Engineering, Stockholm, Sweden, 17 October 2006; Volume 6359, p. 63590U. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipper, S.; Kastens, J.; Foster, T.; Wilson, B.B.; Melton, F.; Grinstead, A.; Deines, J.M.; Butler, J.J.; Marston, L.T. Estimating Irrigation Water Use from Remotely Sensed Evapotranspiration Data: Accuracy and Uncertainties at Field, Water Right, and Regional Scales. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 303, 109036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calera, A.; Garrido-Rubio, J.; Belmonte, M.; Arellano, I.; Fraile, L.; Campos, I.; Osann, A. Remote sensing-based water accounting to support governance for groundwater management for irrigation in la Mancha oriental aquifer, Spain. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 220, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Liao, J.; Hsing, Y.; Huang, C.; Liu, F. Policies, Land Use, and Water Resource Management in an Arid Oasis Ecosystem. Environ. Manag. 2015, 55, 1036–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdar, N.; Mul, M.; Al-Bakri, J.; Uhlenbrook, S.; Rutten, M.; Jewitt, G. Water Accounting Plus: Limitations and Opportunities for Supporting Integrated Water Resources Management in the Middle East and North Africa. Water Int. 2024, 49, 880–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bakri, J.; Shawash, S.; Ghanim, A.; Abdelkhaleq, R. Geospatial Techniques for Improved Water Management in Jordan. Water 2016, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullaev, I.; Rakhmatullaev, S.; Platonov, A.; Sorokin, D. Improving Water Governance in Central Asia through Application of Data Management Tools. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2012, 69, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapino, F.; Hazimeh, R.; Pérez-Blanco, C.D.; Jaafar, H.H. Socioeconomic Impact of Agricultural Water Reallocation Policies in the Upper Litani Basin (Lebanon): A Remote Sensing and Microeconomic Ensemble Forecasting Approach. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 296, 108805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadavid, G.; Perdikou, S.; Hadjimitsis, M.; Hadjimitsis, D. Remote Sensing Applications for Planning Irrigation Management. The Use of SEBAL Methodology for Estimating Crop Evapotranspiration in Cyprus. Sci. J. Riga Tech. Univ. Environ. Clim. Technol. 2012, 9, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calera, A.; Campos, I.; Osann, A.; D’Urso, G.; Menenti, M. Remote Sensing for Crop Water Management: From ET Modelling to Services for End Users. Sensors 2017, 17, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molle, F. Water and the Politics of Quantification: A Programmatic Review. Water Altern. 2024, 17, 325–347. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogesteger, J.; Sanchis-Ibor, C.; Laan, M.; ter Horst, R.; Calera, A.; González-Piqueras, J. The Co-Evolution of Collective Groundwater Management: Understanding the Interdependencies between User-Based Organizations, Remote Sensing and State Agency Support in the La Mancha Oriental Aquifer, Spain. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 104065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, M.; Khan, S. Remote Sensing Application for Estimation of Irrigation Water Consumption in Liuyuankou Irrigation System in China. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Modelling and Simulation (MODSIM05), Advances and Applications for Management and Decision Making, Modelling & Simulation Soc Aust & NZ, Melbourne, Australia, 12–15 December 2020; pp. 1375–1381. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor, A.; Kiparsky, M.; Hubbard, S.S.; Kennedy, R.; Pecharroman, L.C.; Guivetchi, K.; Darling, G.; McCready, C.; Bales, R. Making a Water Data System Responsive to Information Needs of Decision Makers. Front. Clim. 2021, 3, 761444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portoghese, I.; Matarrese, R.; Mirra, L.; Giannoccaro, G. Assimilating Farmers’ Behaviour in the Development of an ET-Based Irrigation Water-Accounting Model. Water Resour. Manag. 2025, 39, 7749–7774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obembe, O.S.; Hendricks, N.P.; Jagadish, S.K. Changes in groundwater irrigation withdrawals due to climate change in Kansas. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 94041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis-Ibor, C.; Bouzidi, Z.; Varanda, M.P.; López-Pérez, E.; Rinaudo, J.-D.; Nieto-Romero, M.; García-Mollá, M.; Faysse, N.; Rubio-Martín, A.; Kchikech, Z.; et al. Can Enhanced Information Systems and Citizen Science Improve Groundwater Governance? Lessons from Morocco, Portugal and Spain. Water 2024, 16, 2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benli, H.; Cassiano, M.; Giannoccaro, G. The Application of Remote Sensing to Improve Irrigation Accounting Systems: A Review. Water 2025, 17, 3430. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233430

Benli H, Cassiano M, Giannoccaro G. The Application of Remote Sensing to Improve Irrigation Accounting Systems: A Review. Water. 2025; 17(23):3430. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233430

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenli, Hakan, Massimo Cassiano, and Giacomo Giannoccaro. 2025. "The Application of Remote Sensing to Improve Irrigation Accounting Systems: A Review" Water 17, no. 23: 3430. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233430

APA StyleBenli, H., Cassiano, M., & Giannoccaro, G. (2025). The Application of Remote Sensing to Improve Irrigation Accounting Systems: A Review. Water, 17(23), 3430. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233430