Passive Water Intake Screen to Reduce Entrainment of Debris and Aquatic Organisms Under Various Hydraulic Flow Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mathematical Model

- —density of the fluid,

- —velocity vector.

- —density of the fluid,

- —velocity vector,

- —vector of mass forces,

- —stress tensor matrix.

- —kinetic energy,

- —density of the fluid,

- —velocity component in corresponding direction,

- dynamic turbulent viscosity index,

- —coefficient of turbulence kinetic energy generation due to averaging of velocity gradients,

- —coefficient of turbulence kinetic energy generation due to buoyancy,

- —coefficient representing the contribution of turbulent dilation to the rate of energy dissipation,

- , —additional coefficients that can be defined,

- —turbulence kinetic energy dissipation rate.

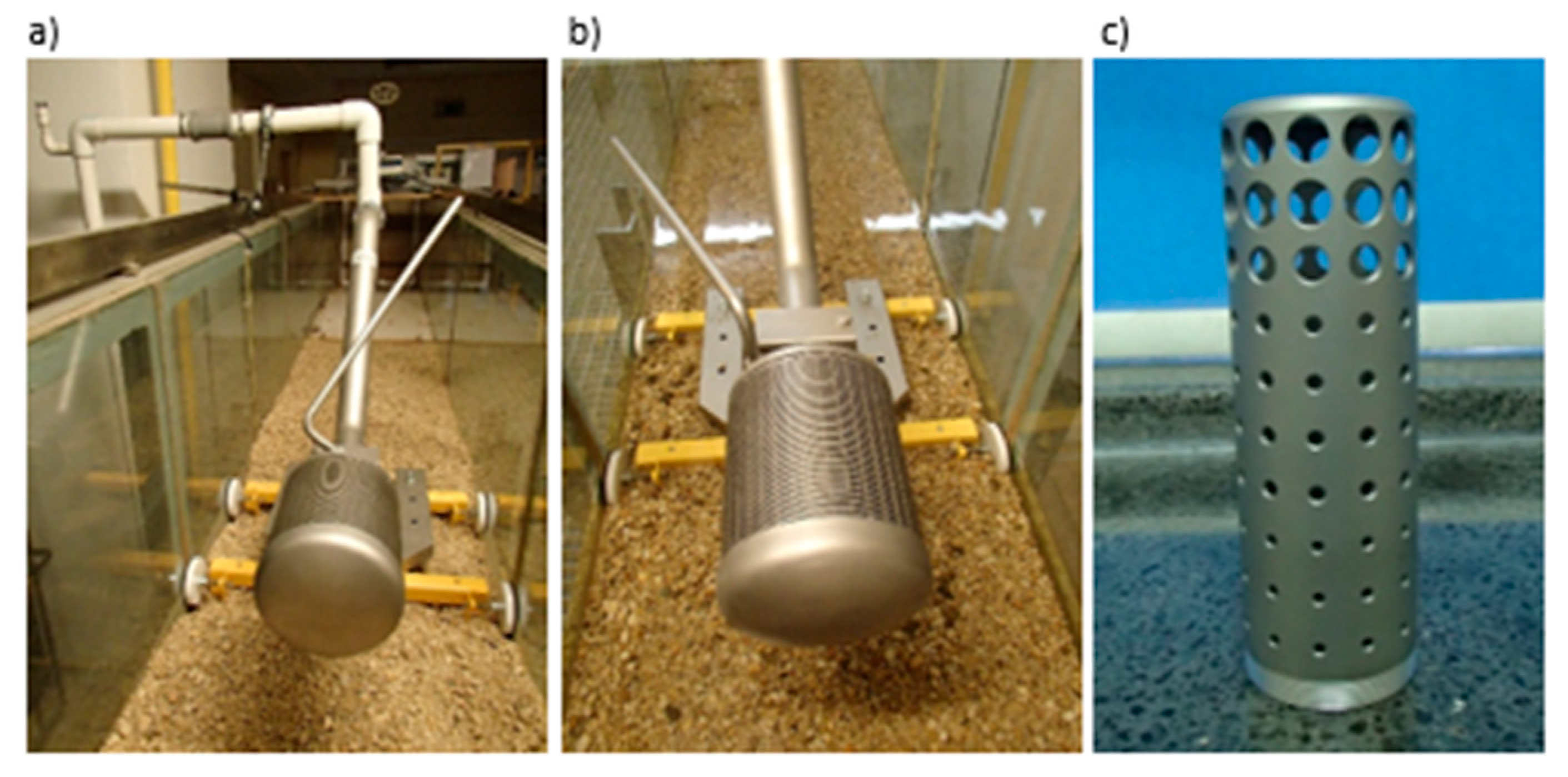

2.2. Laboratory Bench

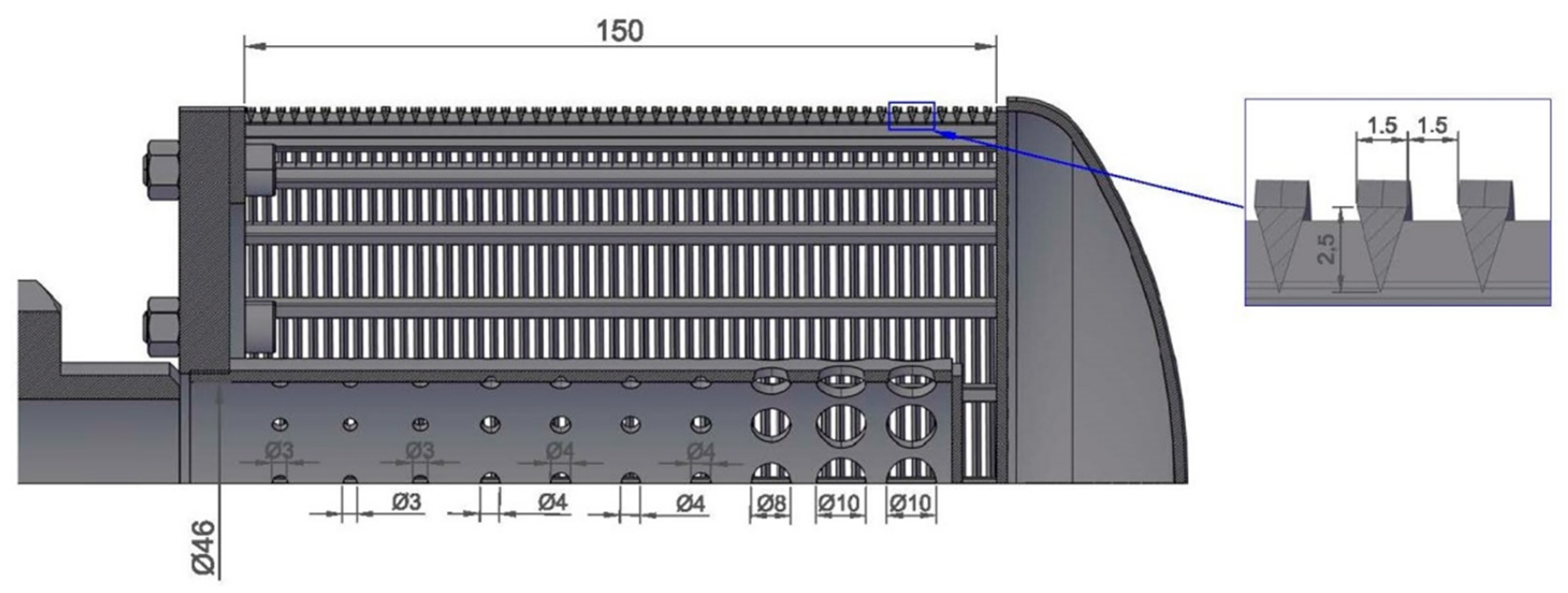

2.3. Model of the Screen and a Deflector Placed Inside

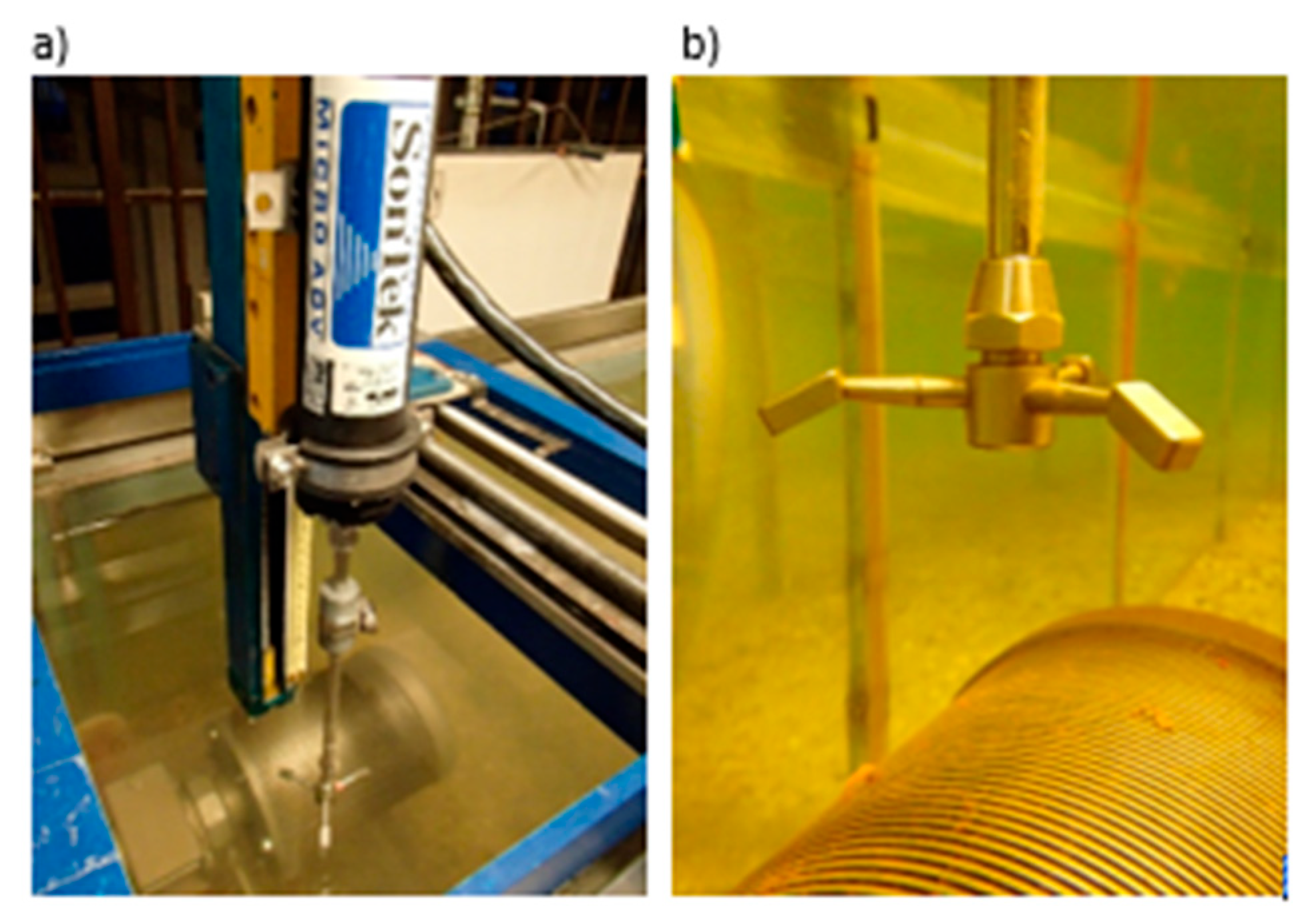

2.4. Measuring Instrumentation

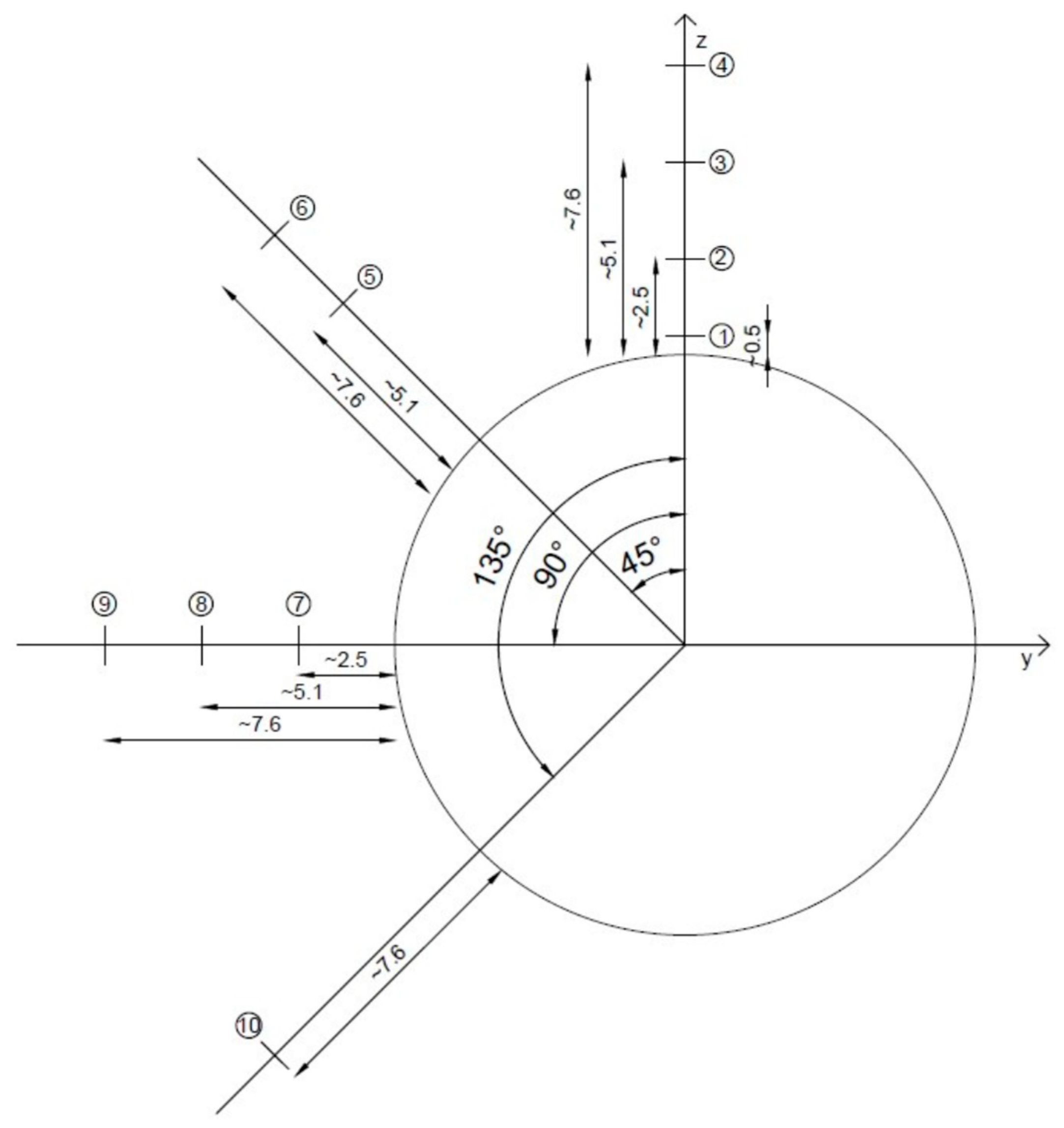

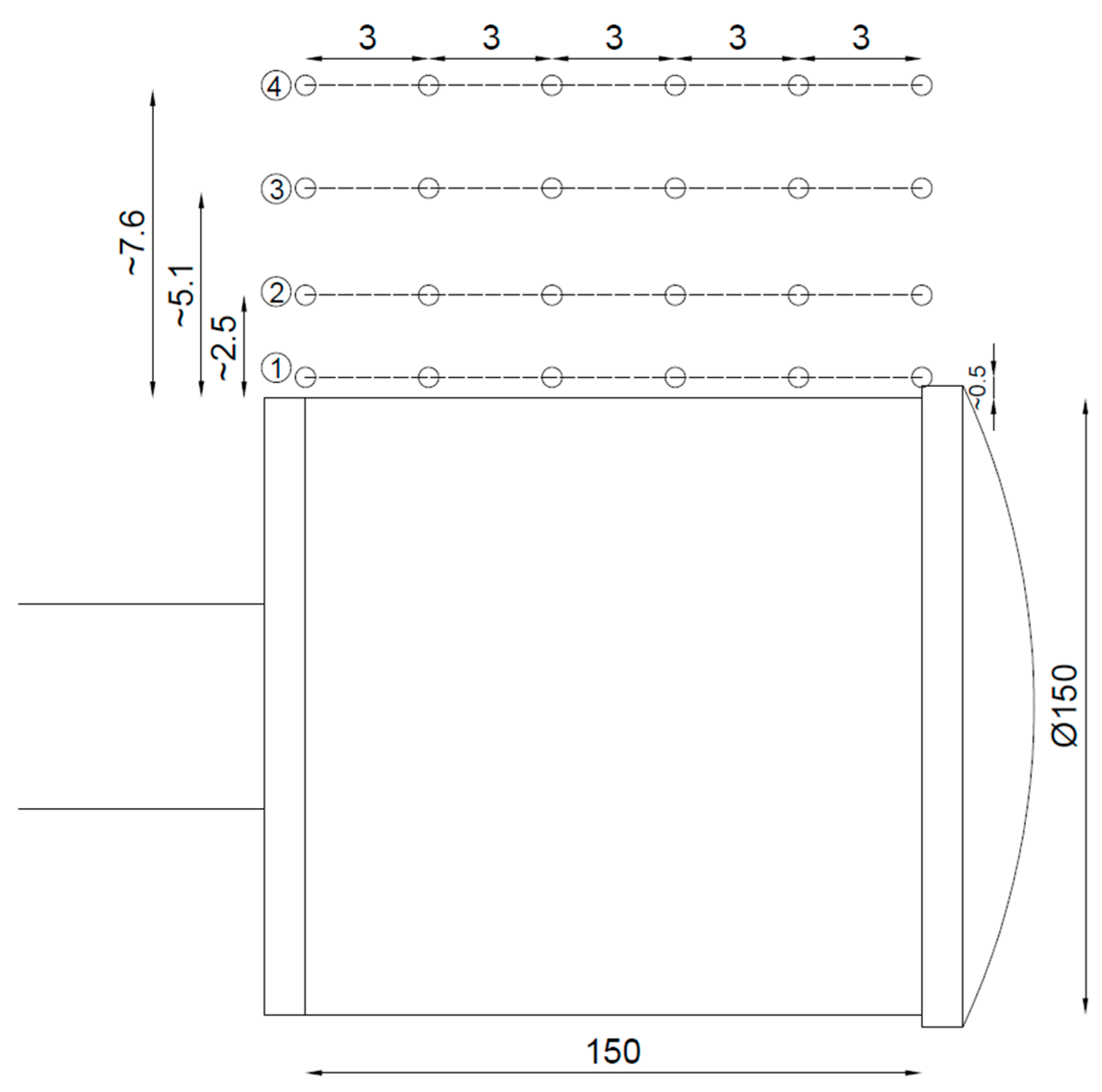

2.5. Location of Measuring Points

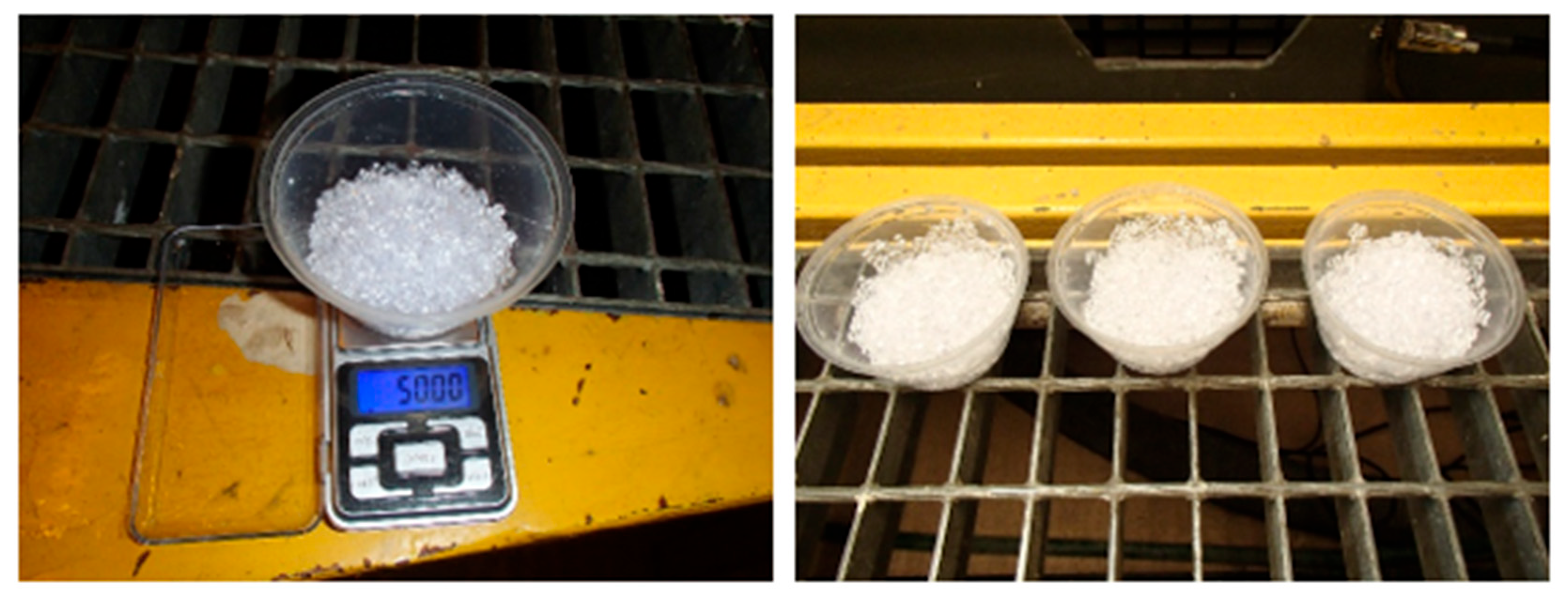

2.6. Experimental Tests with Granulate

3. Results and Discussion

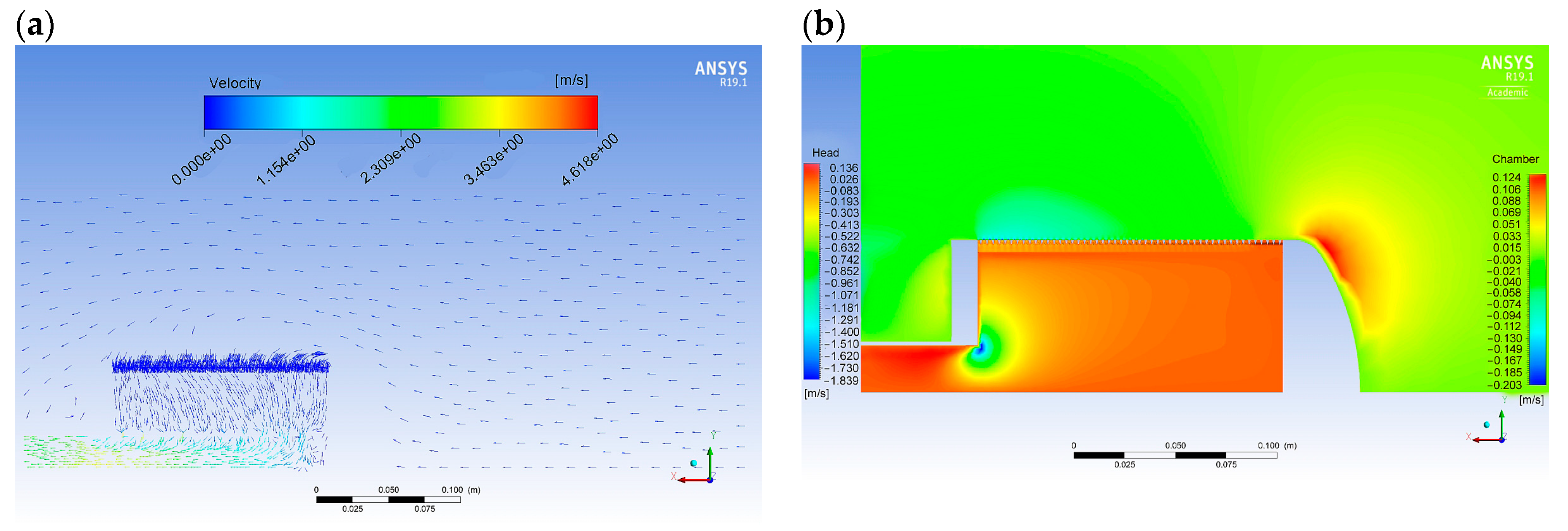

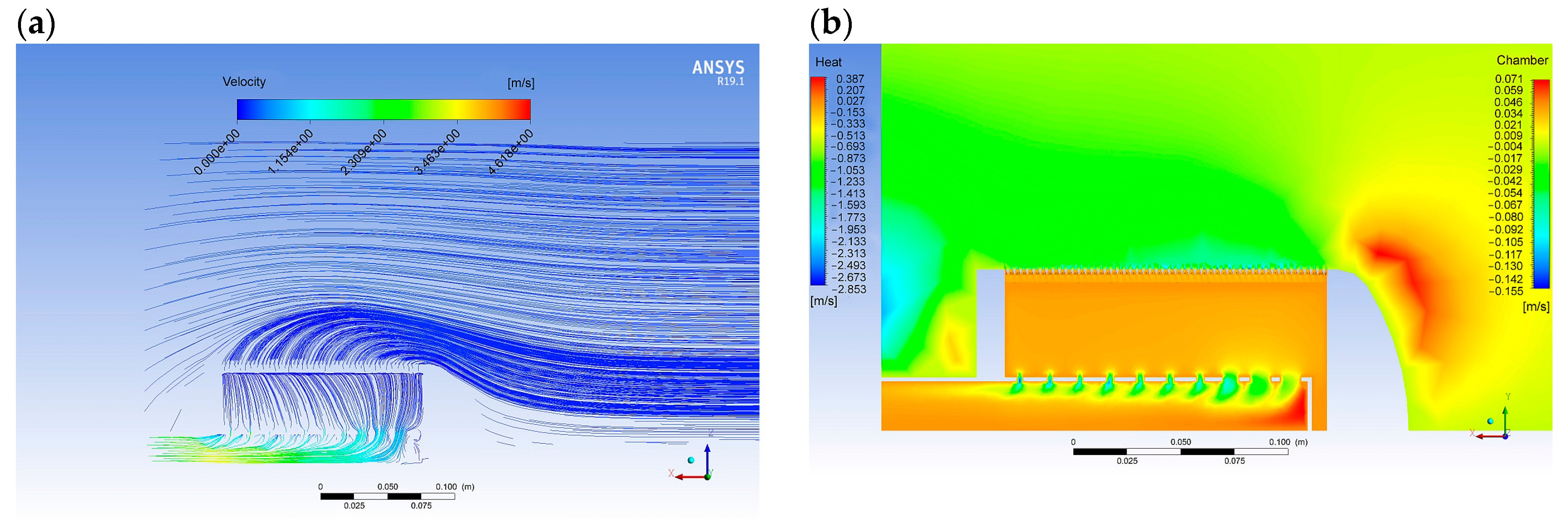

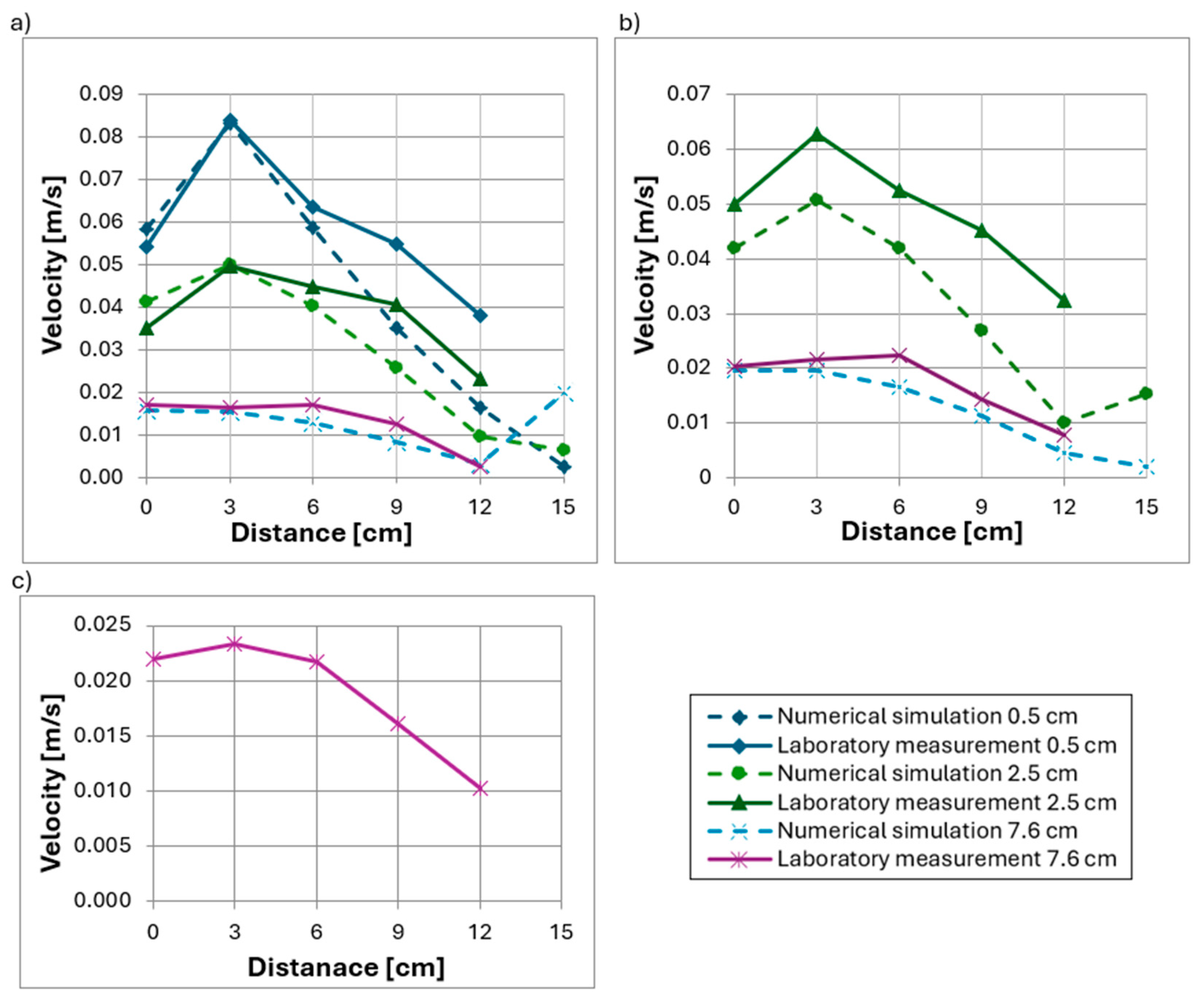

3.1. Numerical Simulations

3.2. Approach Velocity Tests Without the Wedge Wire Screen

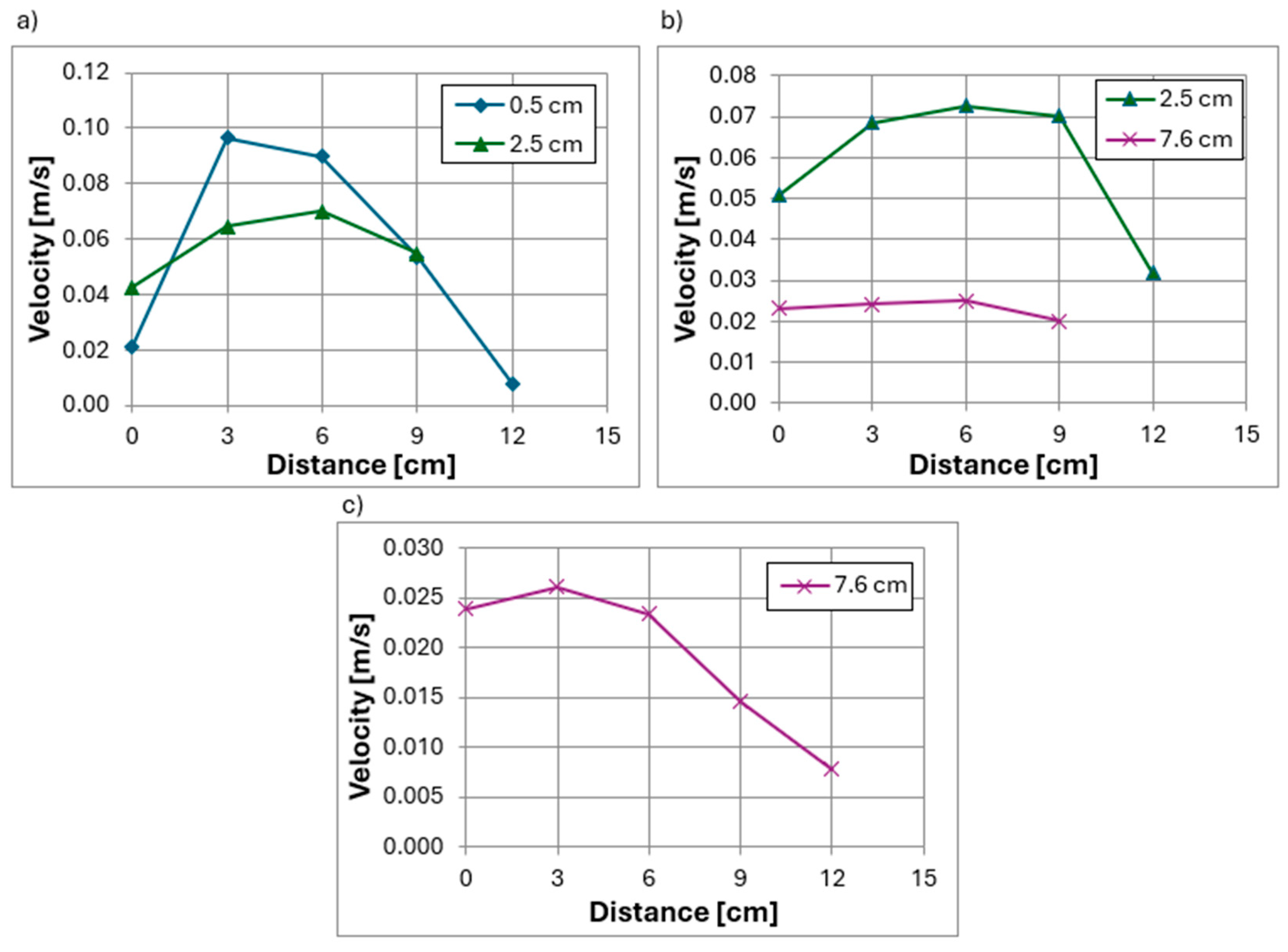

3.3. Studies of Velocity Distributions at a Hydraulic Flume Flow of 113 m3/h

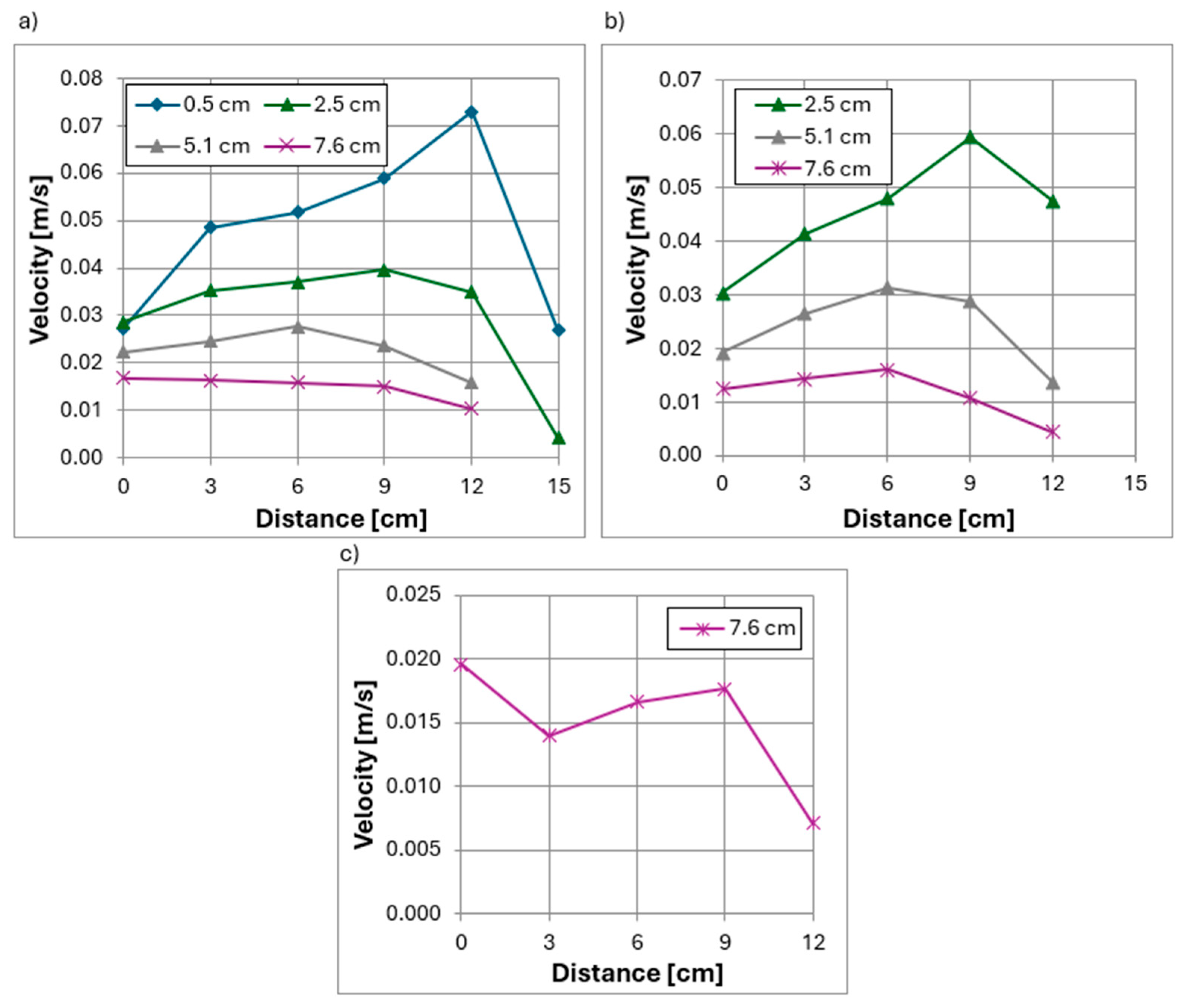

3.4. Studies of Velocity Distributions at a Hydraulic Flume Flow of 226 m3/h

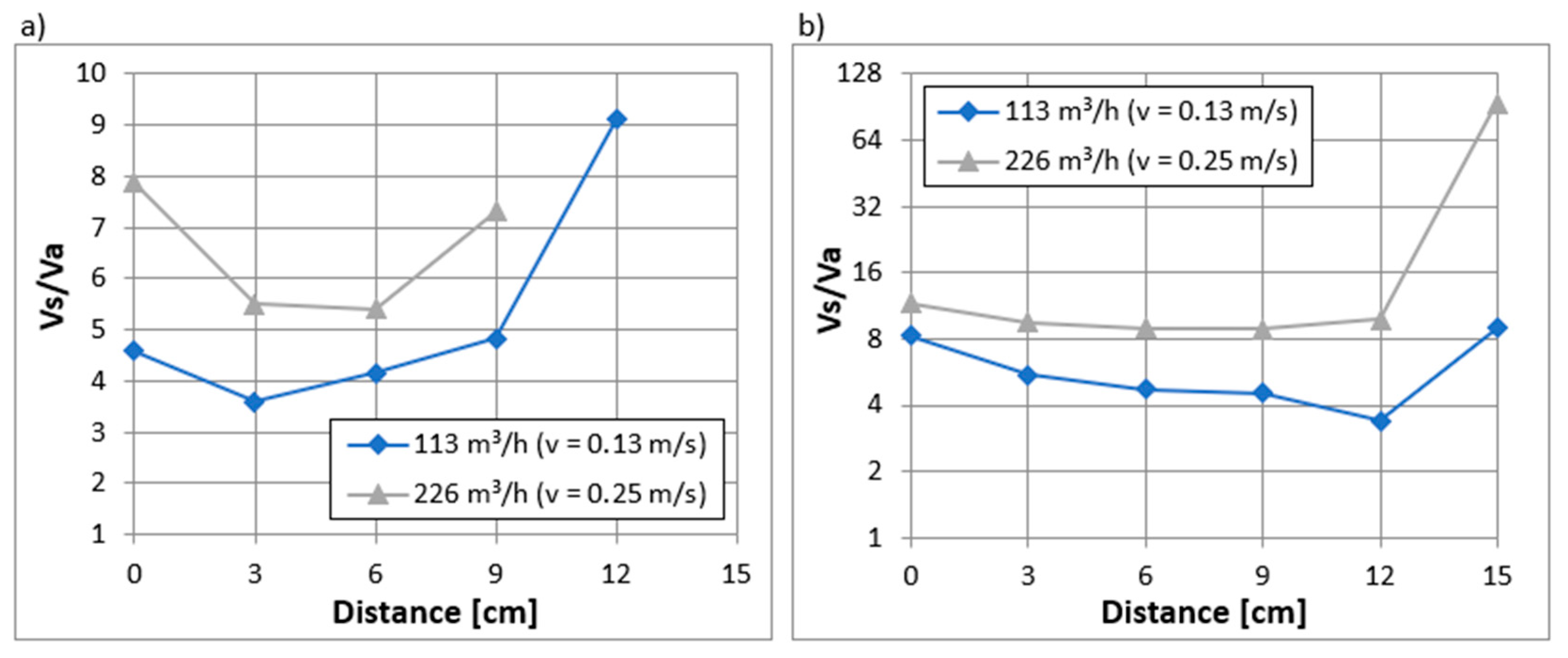

3.5. Analysis of Velocity Vector Component Ratios

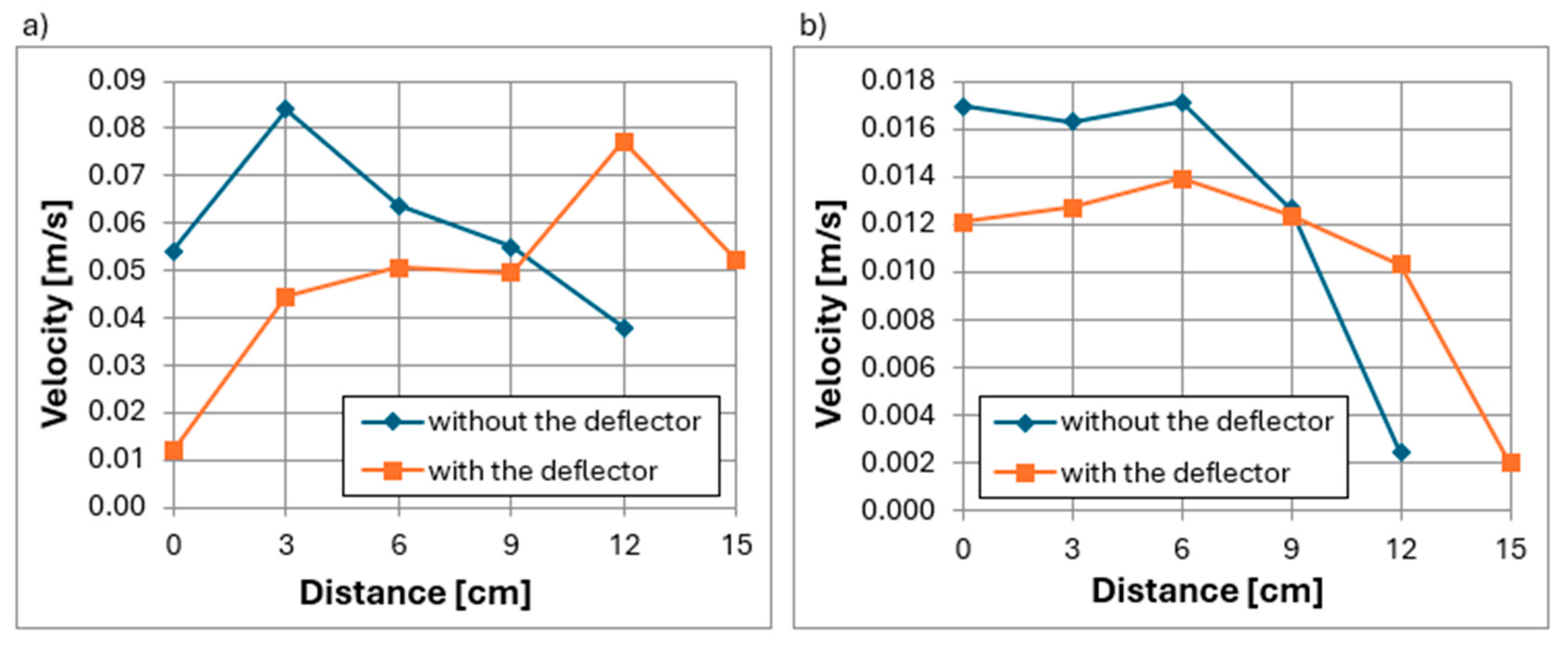

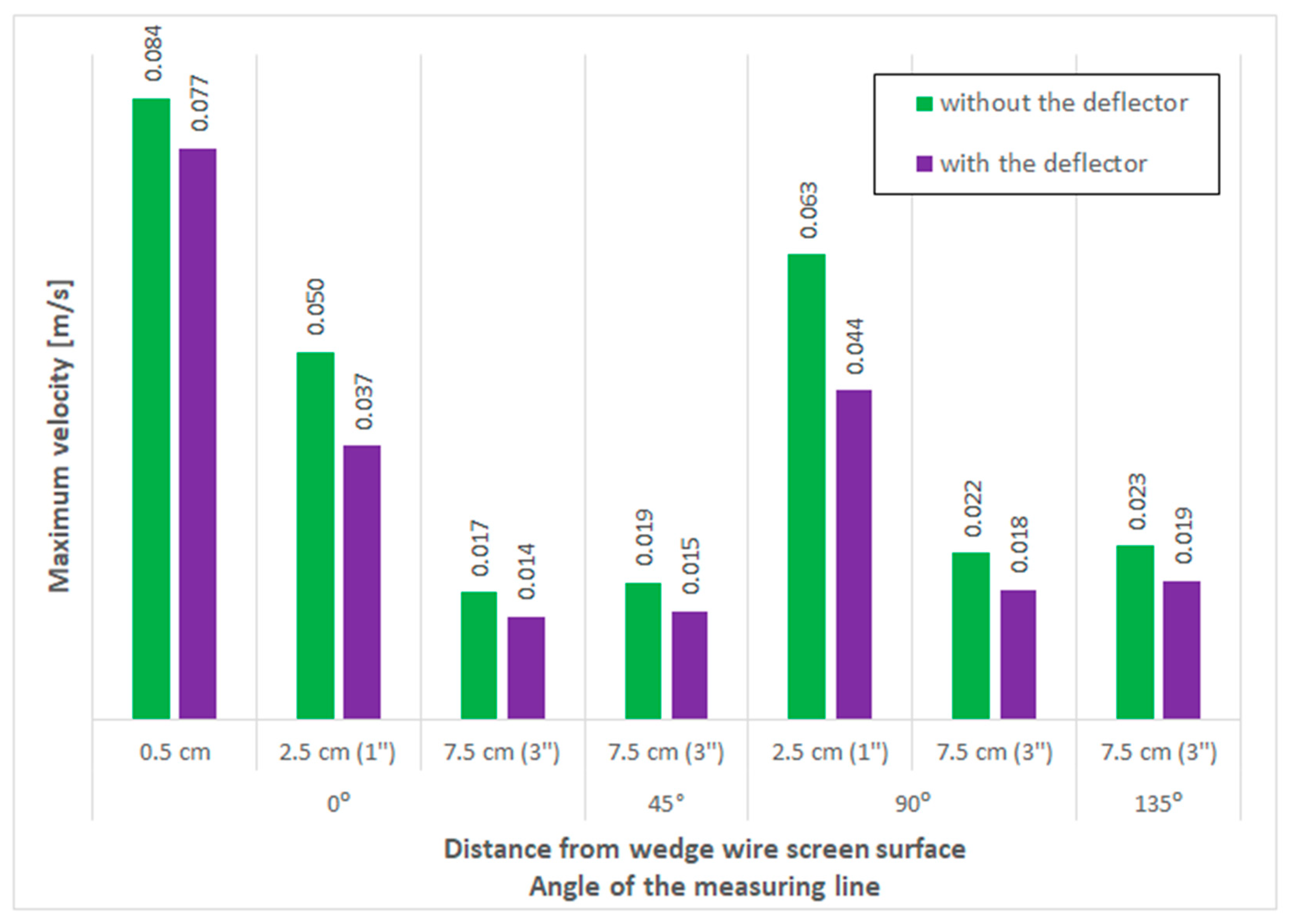

3.6. Effect of the Deflector on Maximum Velocities

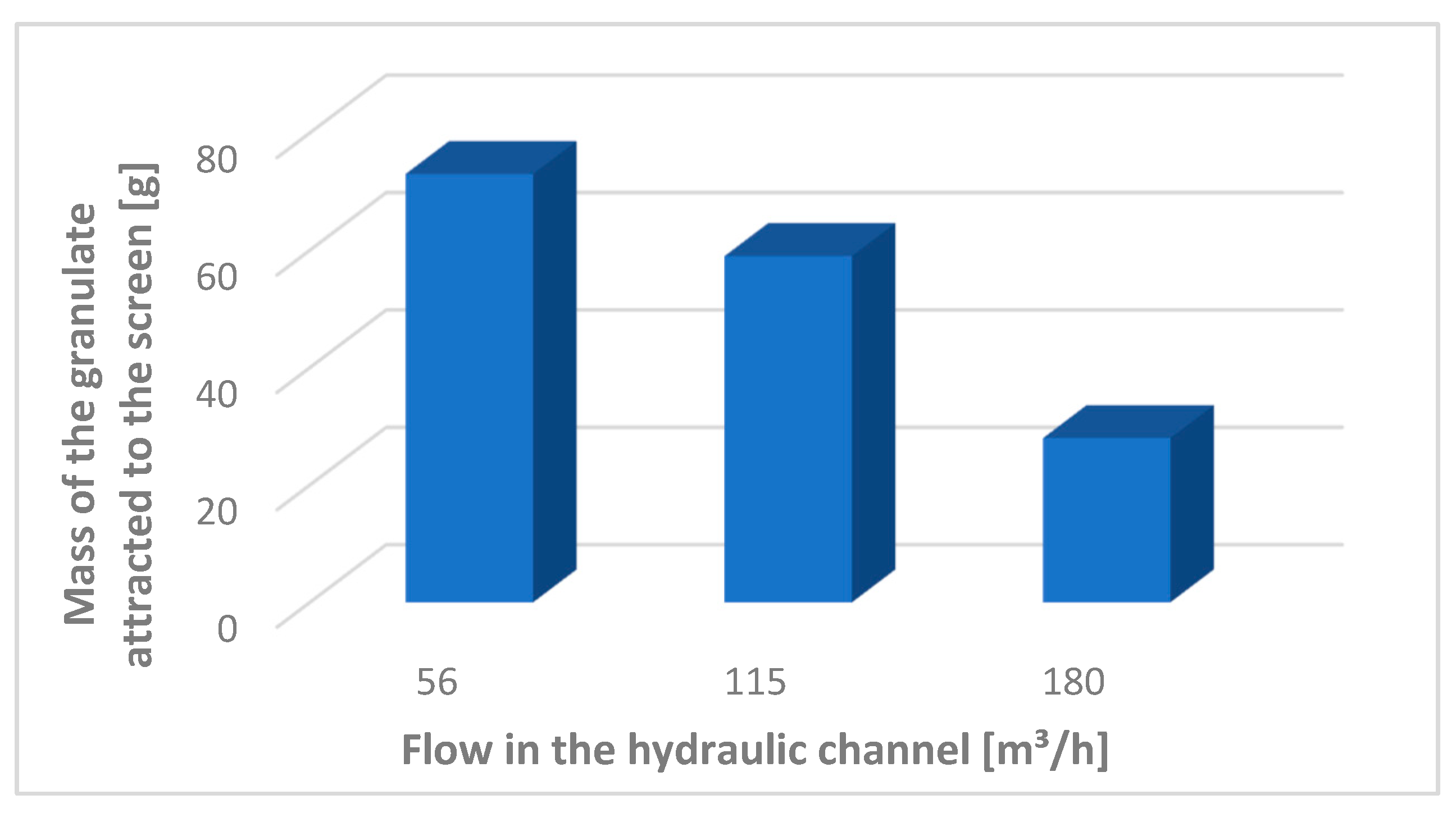

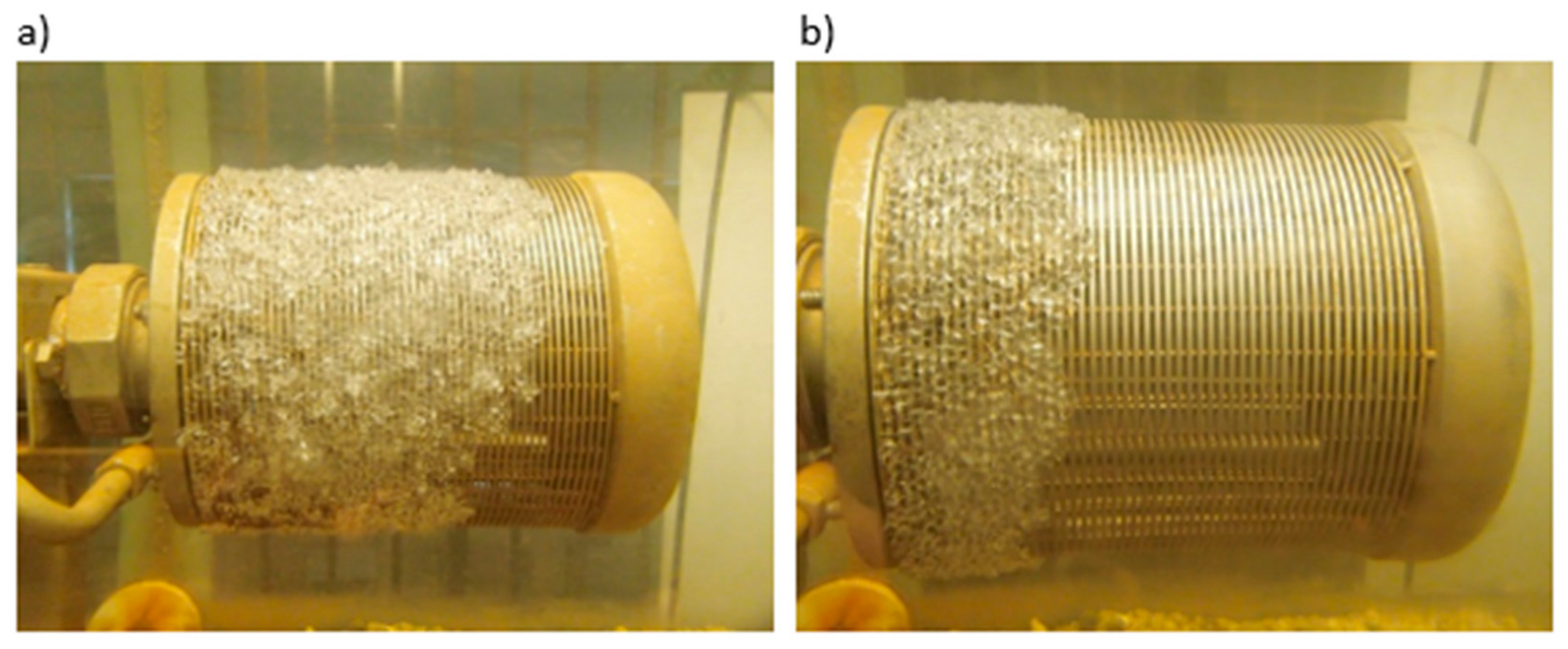

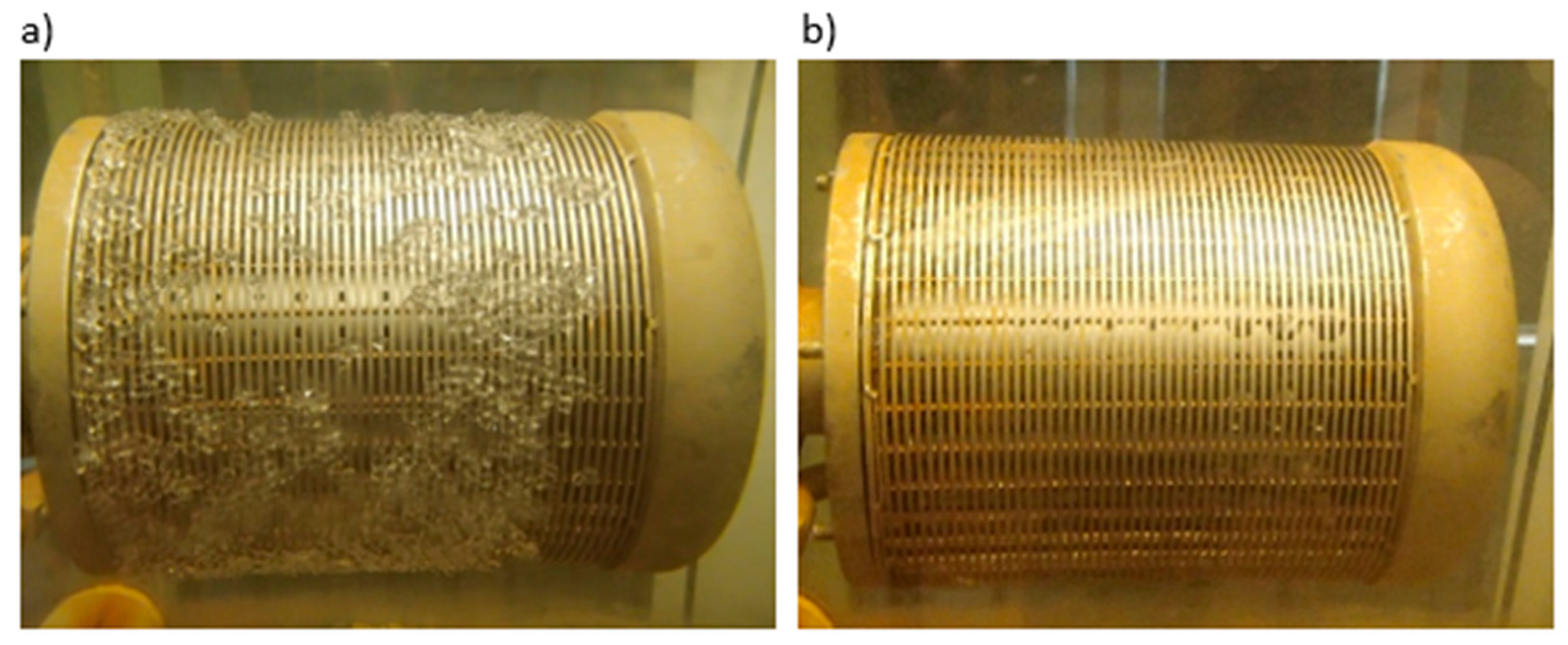

3.7. Tests of Particle Attraction to the Screen Surface

4. Conclusions

- The inlet velocity into the suction pipe without the use of the wedge wire screen was 2.3 m/s and was more than 10 times higher than the maximum permissible values specified in the American and Canadian guidelines.

- In the absence of a deflector installed inside the head, the highest velocity values were obtained close to the suction pipe inlet, while the lowest values were observed on the water inflow side. In contrast, the use of a deflector at both 113 m3/h and 226 m3/h flow rates shifted the maximum normal velocity values toward the inflow side, farther from the suction pipe inlet.

- The use of the deflector resulted in lower local maximum velocity values in longitudinal sections of the head at different distances from the screen surface and at various cross-sectional angles. Due to the higher local velocities on the inflow side with the deflector, it would be reasonable to design and test a deflector with less varied hole sizes.

- Increasing the flow in the hydraulic flume did not significantly alter the shape of the velocity distribution curves around the head. However, laboratory measurements more frequently showed points where the normal velocity vector was reversed, indicating unsteady flow conditions and vortex formation around the head.

- The increased flow also led to a higher ratio of the sweeping velocity vector to the approach velocity vector, thereby reducing the degree of contaminant attraction to the screen surface.

- Numerical simulations performed using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) produced velocity values similar to those obtained in laboratory tests. Differences were approximately 20%, which, given the analyzed velocities expressed in m/s, corresponds to differences on the order of thousandths and is therefore negligible.

- Particle attraction tests using polystyrene confirmed the proper functioning of the deflector. Its use resulted in uniform particle deposition on the screen surface and, importantly, significantly reduced the amount of particles attracted. At a flow rate of 56 m3/h, corresponding to an average velocity of 0.06 m/s, the deflector reduced the mass of particles attracted to the head surface by more than 35%. At higher flow rates of 115 m3/h (average velocity 0.13 m/s) and 180 m3/h (average velocity 0.2 m/s), no particles were attracted to the screen surface.

- The polystyrene tests also demonstrated the effect of hydraulic flume velocity. In the absence of a deflector, increasing the average flow velocity from 0.06 m/s (56 m3/h) to 0.2 m/s (180 m3/h) resulted in a reduction in the mass of attracted granules by almost 62%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Szpak, D.; Tchórzewska-Cieślak, B.; Stręk, M. A new method of obtaining water from water storage tanks in a crisis situation using renewable energy. Energies 2014, 17, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, I.; Arnold, R.; Demiral, D.; Maddahi, M.; Boes, R. Field monitoring and modelling of sediment transport, hydraulics and hydroabrasion at Sediment Bypass Tunnels. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2024, 55, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Council of the European Communities. Council Directive 92/43/EEC on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora, Official Journal of the European Communities. 1992. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/1992/43/oj/eng (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- The European Parliament and The Council of The European Union. Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Water Policy, Official Journal of the European Communities. 2000. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/homepage.html (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Environmental Protection Agency. National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System—Final Regulations to Establish Requirements for Cooling Water Intake Structures at Existing Facilities and Amend Requirements at Phase I Facilities. Fed. Regist. 2014, 79, 158. [Google Scholar]

- Mikheev, P.; Suleyman, A.; Mutalibov, Z. On the use of fish protection structures in the conditions of water intake buckets. Prirodoobustrojstvo 2022, 4, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benin, D.M.; Mikheev, P.A.; Borovskoy, V.P. Optimization principles for inlet portal designs of gravity fish outlets of fish protection structures of water intake facilities. Nexo Rev. Científica 2022, 35, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geist, J. Editorial: Green or red: Challenges for fish and freshwater biodiversity conservation related to hydropower. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2021, 31, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, N.; Knott, J.; Pander, J.; Geist, J. Fish behavior at the horizontal screen of a novel shaft hydropower plant. River Res. Appl. 2024, 40, 1219–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Wei, J.; Xie, Q.; Miao, B.; Wang, L. Experimental and Numerical Investigations of Hydraulics in Water Intake with Stop-Log Gate. Water 2020, 12, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, L.J.; Collier, S.J.; Thomas, R.E.; Norman, J.; Wright, R.M.; Bolland, J.D. The influence of passive wedge-wire screen aperture and flow velocity on juvenile European eel exclusion, impingement and passage. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 192, 106972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Zhu, D.; Shao, W.; Fu, J.; Rui, J. Forebay hydraulics and fish entrainment risk assessment upstream of a high dam in China. J. Hydro Environ. Res. 2015, 9, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shomorin, G.O.; Storebakken, T.; Kraugerud, O.F.; Overland, M.; Hansen, B.R.; Hansen, J.O. Evaluation of wedge wire screen as a new tool for faeces collection in digestibility assessment in fish: The impact of nutrient leaching on apparent digestibility of nitrogen, carbon and sulphur from fishmeal, soybean meal and rapeseed meal-based diets in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquaculture 2019, 504, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boys, C.A.; Robinson, W.; Baumgartner, L.J.; Rampano, B.; Lowry, M. Influence of approach velocity and mesh size on the entrainment and contact of a Lowland river fish assemblage at a screened irrigation pump. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missimer, T.M.; Hogan, T.W.; Pankratz, T. Passive Screen Intakes: Design Construction Operation Environmental Impacts. In Intakes and Outfalls for Seawater Reverse-Osmosis Desalination Facilities; Environmental Science and Engineering; Missimer, T., Jones, B., Maliva, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 79–104. [Google Scholar]

- Burgi, P.; Christensen, R.; Glickman, A.; Johnson, P.; Mefford, B. Fish Protection at Water Diversions: A Guide for Planning and Designing Fish Exclusion Facilities; Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Denver: Denver, CO, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nordlund, B. Designing Fish Screens for Fish Protection at Water Diversions; National Marine Fisheries Service: Lacey, WA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- National Marine Fisheries Service Southwest Region, Portland, Oregon, 1996. Juvenile Fish Screen Criteria for Pump Intakes. Available online: https://media.fisheries.noaa.gov/dam-migration/fish_screen_criteria_for_pumped_water_intakes.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Turnpenny, A.W.H.; Horsfield, R.A. International Fish Screening Techniques; WIT PRESS: Southhampton, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, D.; Bonnett, M.; Jellyman, D.; Unwin, M. Fish Screening: Good Practice Guidelines for Canterbury, NIWA Client Report CHC 2007-092; National Institute of Water Atmospheric Research Ltd.: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- SI 2009/3344; Eels (England and Wales) Regulations. The Secretary of State in Relation to England and the Welsh Ministers: London, UK, 2009.

- Environment Agency. Screening at intakes and outfalls: Measures to protect eel. In The Eel Manual—GEHO0411BTQD-E-E; Environment Agency: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zielina, M.; Pawłowska, A.; Kowalska-Polok, A. Numerical analysis of cylindrical wedge-wire screen operation. In Advances and Trends in Engineering Sciences and Technologies II; Ali, M., Platko, P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 709–714. [Google Scholar]

- Chanson, H. Hydraulics of aerated flows: Qui pro quo? J. Hydraul. Res. 2013, 51, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanson, H. Turbulent air–water flows in hydraulic structures: Dynamic similarity and scale effects. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2009, 9, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zima, P.; Sawicki, J. Numerical analysis of the influence of 2D dispersion parameters on the spread of pollutants in the coastal zone. Water 2024, 16, 3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocken, B.; Gualtieri, C. Ten iterative steps for model development and evaluation applied to Computational Fluid Dynamics for Environmental Fluid Mechanics. Environ. Model. Softw. 2012, 33, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macián-Pérez, J.; García-Bartual, R.; Huber, B.; Bayon, A.; Valles-Morán, F. Analysis of the Flow in a Typified USBR II Stilling Basin through a Numerical and Physical Modeling Approach. Water 2020, 12, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielina, M.; Pawłowska-Salach, A.; Kaczmarski, K. Hydraulic analysis of a passive wedge wire water intake screen for ichthyofauna protection. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipin, A.; Sepahvand, A.; Rustamova, N. Hydraulic Calculations of a Telescopic Water Intake. Slovak J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 31, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilsnack, M. An Application of Computational Fluid Dynamics to the Hydraulic Analysis of a Water Intake Tower. J. Water Manag. Model. 2022, 30, C494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bor, A.; Szabo-Meszaros, M.; Vereide, K.; Lia, L. Application of Three-Dimensional CFD Model to Determination of the Capacity of Existing Tyrolean Intake. Water 2024, 16, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senfter, T.; Berger, M.; Schweiberer, M.; Knitel, S.; Pillei, M. An Experimentally Validated CFD Code to Design Coandă Effect Screen Structures. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, J.M.; García, J.T.; Guachamín-Paladines, K.; Ros Bernal, A.; Castillo, L.G. Testing a smoothed-particle hydrodynamics (SPH) code to solve the hydrodynamics of a bottom intake Coanda screen. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Hydraulic Structures, Zurich, Switzerland, 17–19 June 2024; ETH Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión-Coronel, E.; Ortiz, P.; Nanía, L. Physical Experimentation and 2D-CFD Parametric Study of Flow through Transverse Bottom Racks. Water 2022, 14, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, J.M.; García, J.T.; Castillo, L.G. Experimental and Numerical Modelling of Bottom Intake Racks with Circular Bars. Water 2018, 10, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mater, B.D.; Coutant, C.C.; Ham, K.D.; Perkins, W.A.; Christ, J.F.; Anderson, D.M.; Singh, R.K.; Rahrooh, A.A.; Tarufelli, B.L.; Mueller, R.P. Making a Deal with the Devilfish: Biometric-Informed Screening Technology CRADA—514 (Final Report); Pacific Northwest National Laboratory: Richland, WA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Akulshin, A.A.; Bredikhina, N.V.; Akulshin, A.n.A.; Aksenteva, I.Y.; Ermakova, N.P. Development of Filters with Minimal Hydraulic Resistance for Underground Water Intakes. Civ. Eng. J. 2020, 6, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennels, D.C.; Hudson, H.M. Pipe Flow: A Practical and Comprehensive Guide; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Xiong, Q.; Morris, P.J.; Paterson, E.G.; Sergeev, A.; Wang, Y.C. OpenFOAM for Computational Fluid Dynamics. Not. Am. Math. Soc. 2014, 61, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.R.; Camacho, R.G.R. The Boundary Element Method Applied to Incompressible Viscous Fluid Flow. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2005, 27, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymkiewicz, R. Mathematical Modeling of Flows in Rivers and Canals; Scientific Publishing PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jeżowiecka-Kabsch, K.; Szewczyk, H. Fluid Mechanics; Publishing House of Wroclaw University of Technology: Wroclaw, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pawłowska-Salach, A.; Zielina, M.; Kaczmarski, K. Passive Water Intake Screen to Reduce Entrainment of Debris and Aquatic Organisms Under Various Hydraulic Flow Conditions. Water 2025, 17, 3424. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233424

Pawłowska-Salach A, Zielina M, Kaczmarski K. Passive Water Intake Screen to Reduce Entrainment of Debris and Aquatic Organisms Under Various Hydraulic Flow Conditions. Water. 2025; 17(23):3424. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233424

Chicago/Turabian StylePawłowska-Salach, Agata, Michał Zielina, and Karol Kaczmarski. 2025. "Passive Water Intake Screen to Reduce Entrainment of Debris and Aquatic Organisms Under Various Hydraulic Flow Conditions" Water 17, no. 23: 3424. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233424

APA StylePawłowska-Salach, A., Zielina, M., & Kaczmarski, K. (2025). Passive Water Intake Screen to Reduce Entrainment of Debris and Aquatic Organisms Under Various Hydraulic Flow Conditions. Water, 17(23), 3424. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233424