A New Fuzzy Preference Relation (FPR) Approach to Prioritizing Drinking Water Hazards: Ranking, Mapping, and Operational Guidance

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Nitrates (NO3−). In Central and Eastern Europe, the problem of nitrate pollution of water associated with intensive agriculture remains significant. Studies in Poland have shown that in some municipalities, concentrations in groundwater exceed 50 mg/L, increasing the risk of methemoglobinemia in infants (blue baby syndrome) [10]. Similar results have been reported in the Czech Republic and Hungary [11].

- -

- Lead (Pb). Lead contamination in drinking water is well documented, for example, in the Flint (USA) incident, where corrosion of old pipes led to neurotoxic exposure of thousands of children [12]. In Europe, the problem mainly concerns internal installations—studies in the United Kingdom have shown that in older buildings, Pb concentrations in water exceeded 10 μg/L [13].

- -

- Arsenic (As). The most well-known incidents of mass exposure concern Bangladesh and India, where tens of millions of people have been using groundwater with As concentrations reaching hundreds of μg/L for decades, resulting in an epidemic of skin and bladder cancer [14]. In Europe, the problem has been noted in southern Italy and Hungary, among other places, where geothermal waters naturally contain arsenic in concentrations above 10 μg/L [15,16].

- -

- Trihalomethanes (THMs). An analysis by Villanueva [17] covering 26 EU countries showed that approximately 6500 cases of bladder cancer per year (about 5% of the total) can be attributed to chronic exposure to THMs in drinking water, even in systems that comply with the 100 μg/L limit.

- -

- Manganese (Mn). Epidemiological studies in Canada and the USA have shown that chronic consumption of water with elevated manganese concentrations (above 100 μg/L) is associated with reduced cognitive ability in children [18].

- -

- Copper (Cu). Exceedances of acceptable values are recorded locally in highly corrosive water supply systems—chronic exposure can lead to hepatotoxicity and gastric problems [19].

- -

- Iron (Fe). In most cases, iron does not pose a health risk, but it is the cause of consumer complaints due to its colour, taste and sediment, and it can also promote the secondary growth of microorganisms in the network [6].

- -

- Water Quality Index (WQI). Many studies use WQI, a multi-parameter index that aggregates various variables (chemical, physicochemical, biological) into a single index value, which facilitates communication of the overall water status. For example, Luo et al. [20] used WQI together with multidimensional analysis to assess 17 drinking water parameters in the city of Nanning (China), including metals such as arsenic, lead and mercury [20].

- -

- Statistical and probabilistic methods. Other studies use classification and comparison methods, such as ranking or aggregation approaches, as well as probabilistic risk measures. In a study of the Douro River Basin (Portugal), the authors used various risk measures (mean, variance, exceedance probability, value at risk, etc.) and then merged the ranking of monitoring stations on this basis [21].

- -

- WQI with uncertainty analysis. Methods combining the classic WQI with uncertainty analysis are becoming increasingly common. Critical studies of the arbitrariness in the selection of weights indicate that the choice of parameters and their weights can significantly affect the final result and interpretation of water status. An example of this is analyses that have shown that different weighting schemes lead to different quality assessments [22].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Basics of the Research Methodology

- -

- trapezoidal function μ(x; a, b, c, d)

- -

- triangular function μ(x; a, b, c)

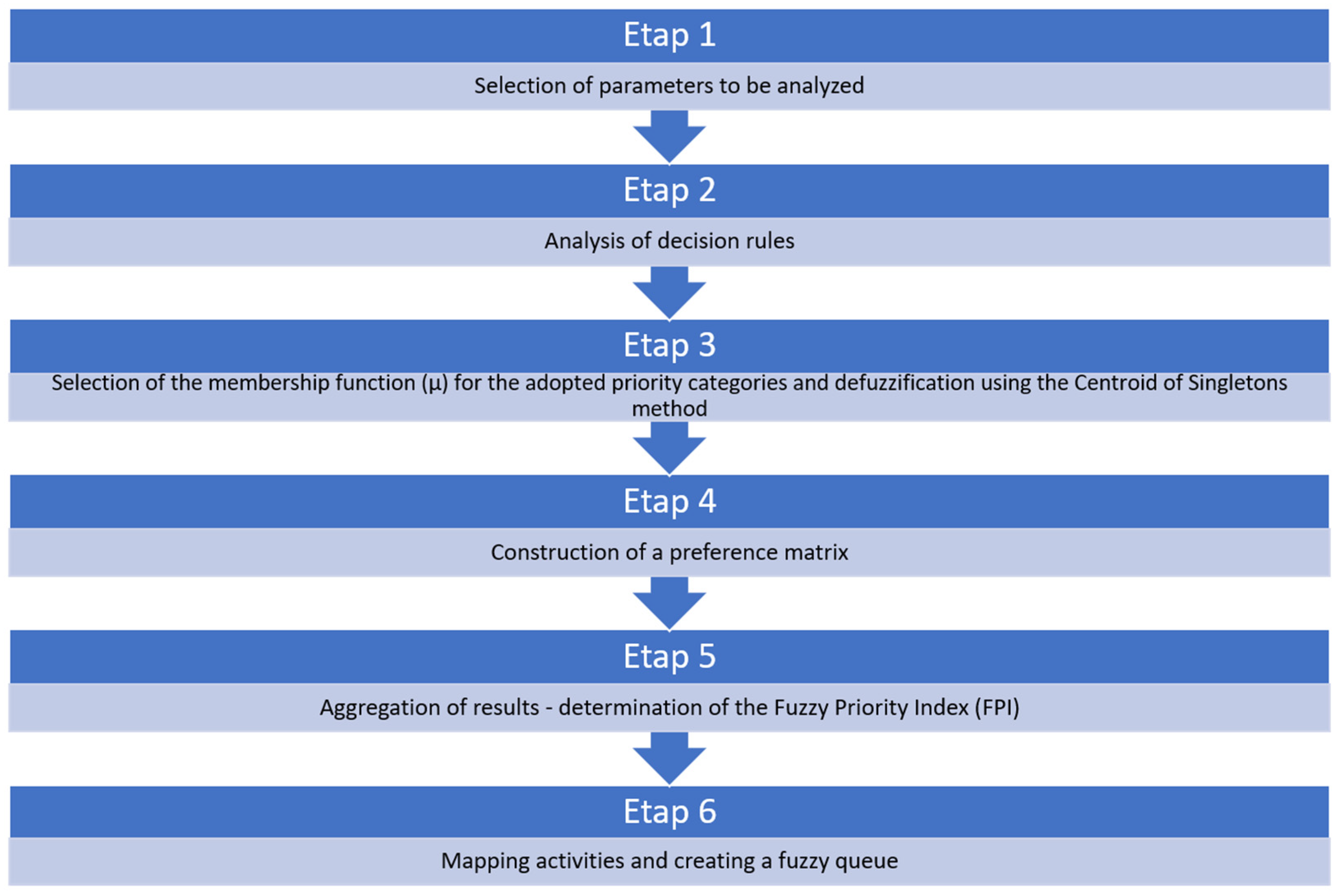

2.2. Prioritisation of Water Quality Parameters: Assumptions and Stages of the Method (FPR–FPI)

2.2.1. Stage 1. Selection of Parameters for Analysis

- -

- health significance (toxicity, carcinogenic potential, impact on sensitive groups),

- -

- frequency of occurrence in water supply systems,

- -

- technological/operational consequences (colour, sediments).

- -

- highest priority (rank 5): parameter with the highest priority due to carcinogenicity and neurotoxicity, with proven health effects even with chronic low exposure (e.g., arsenic, lead).

- -

- high priority (rank 4): parameter of high health significance, more frequently exceeded in monitoring or with a documented link to negative effects (e.g., nitrates, THM, mercury),

- -

- medium priority (rank 3): parameter of significant toxicological importance, but less frequently exceeding normative values (e.g., chromium),

- -

- low priority (rank 1–2): copper, manganese, iron—mainly local exceedances and aesthetic/technological problems, less toxicological and health significance.

2.2.2. Stage 2. Analysis of Decision Rules

- -

- absolutely more dangerous (absolute preference): aij = 0.9

- -

- definitely more dangerous: aij = 0.80

- -

- significantly more dangerous: aij = 0.70

- -

- slightly more dangerous: aij = 0.55

- -

- equally dangerous: aij = 0.50

- The sum of preferences ai relative to aj and aj relative to ai is equal to one, i.e., there is so-called additive reciprocity: (aij) + (aji) = 1 for all i ≠ j.

- Diagonal: aii = 0.5 for all i.

- Accepting the relationship (aji) = 1 − (aij) and (aii) = 0.5 creates a fuzzy relation (of preference) with the membership function μA (ai, aj).

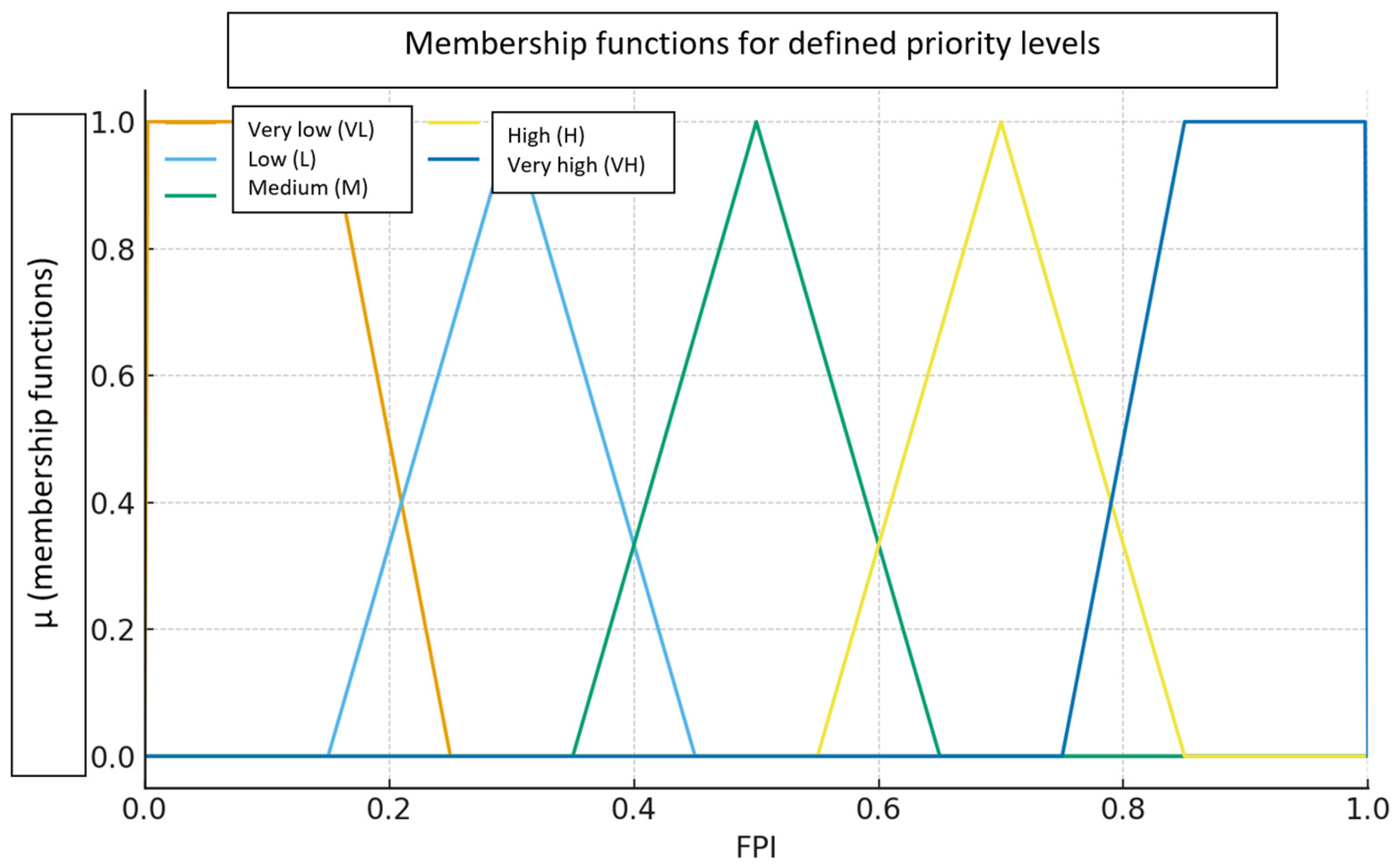

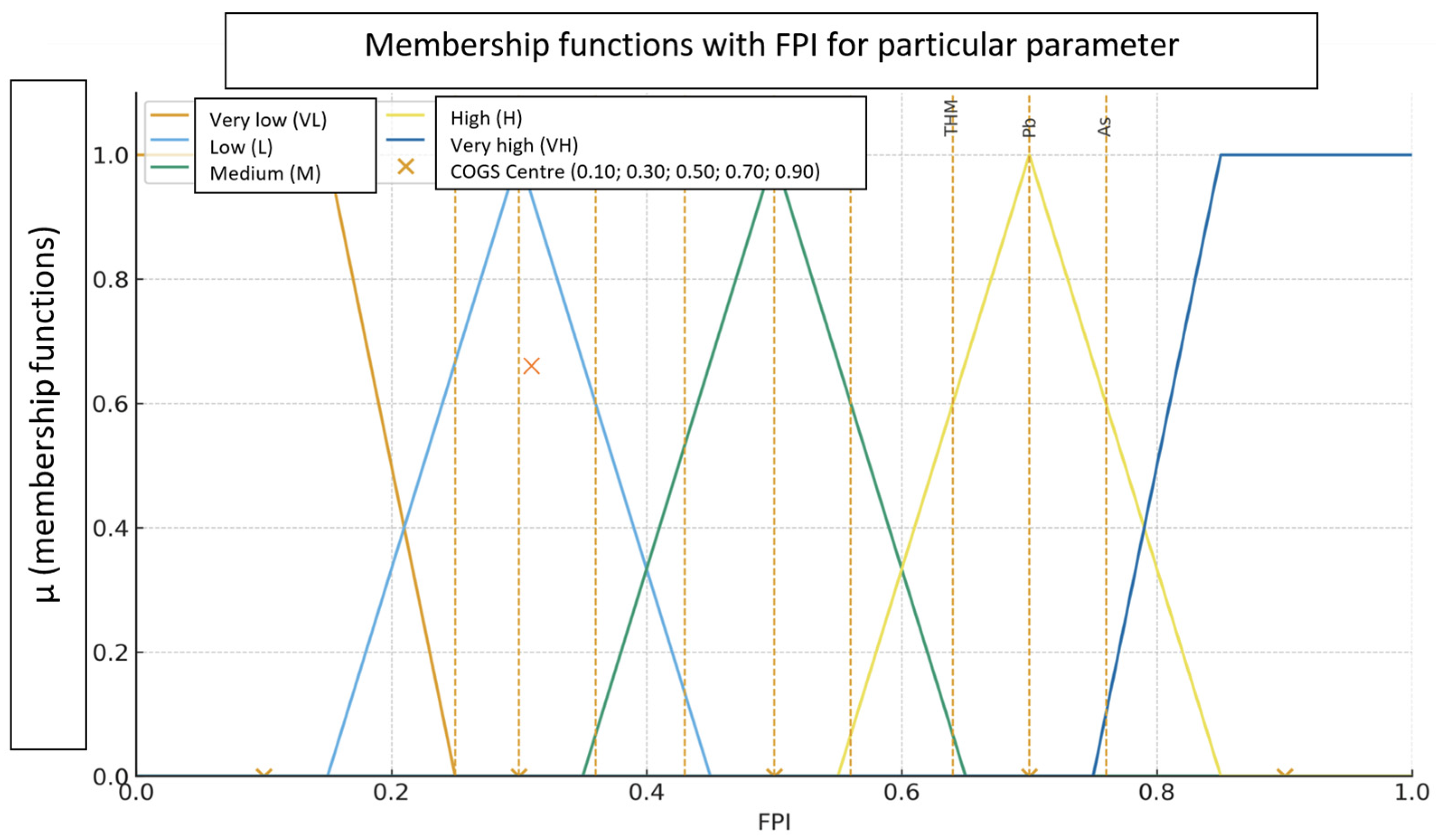

2.2.3. Stage 3. Selection of Membership Functions (μ) for the Adopted Priority Categories and Defuzzification Using the Centroid of Singletons Method (A Priori Calibration)

- -

- Very low (VL)—trapezoidal ⟨a = 0.00, b = 0.00, c = 0.15, d = 0.25⟩, (centre C = 0.10)

- -

- Low (L)—triangular ⟨a = 0.15, b = 0.30, c = 0.45⟩, (centre C = 0.30)

- -

- Medium (M)—triangular ⟨a = 0.35, b = 0.50, c = 0.65⟩, (centre C = 0.50)

- -

- High (H)—triangular ⟨a = 0.55, b = 0.70, c = 0.85⟩, (centre C = 0.70)

- -

- Very high (VH)—trapezoidal ⟨a = 0.75, b = 0.85, c = 1.00, d = 1.00⟩, (centre C = 0.90).

2.2.4. Stage 4. Construction of the Preference Matrix

- —expert assessment, e = 1, …, m:

- m—number of experts.

2.2.5. Stage 5. Aggregation of Results—Determination of the Fuzzy Priority Index (FPI)

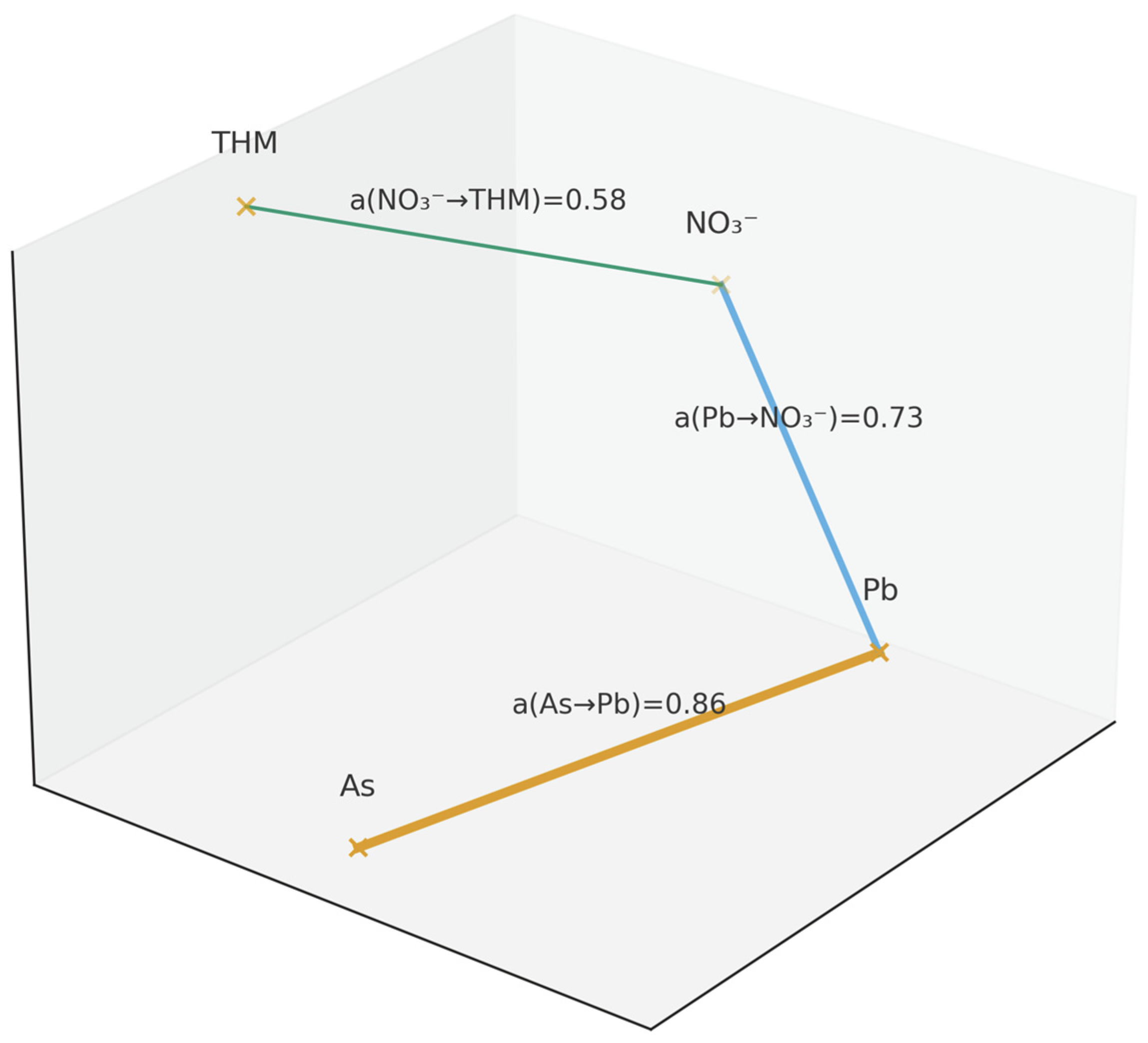

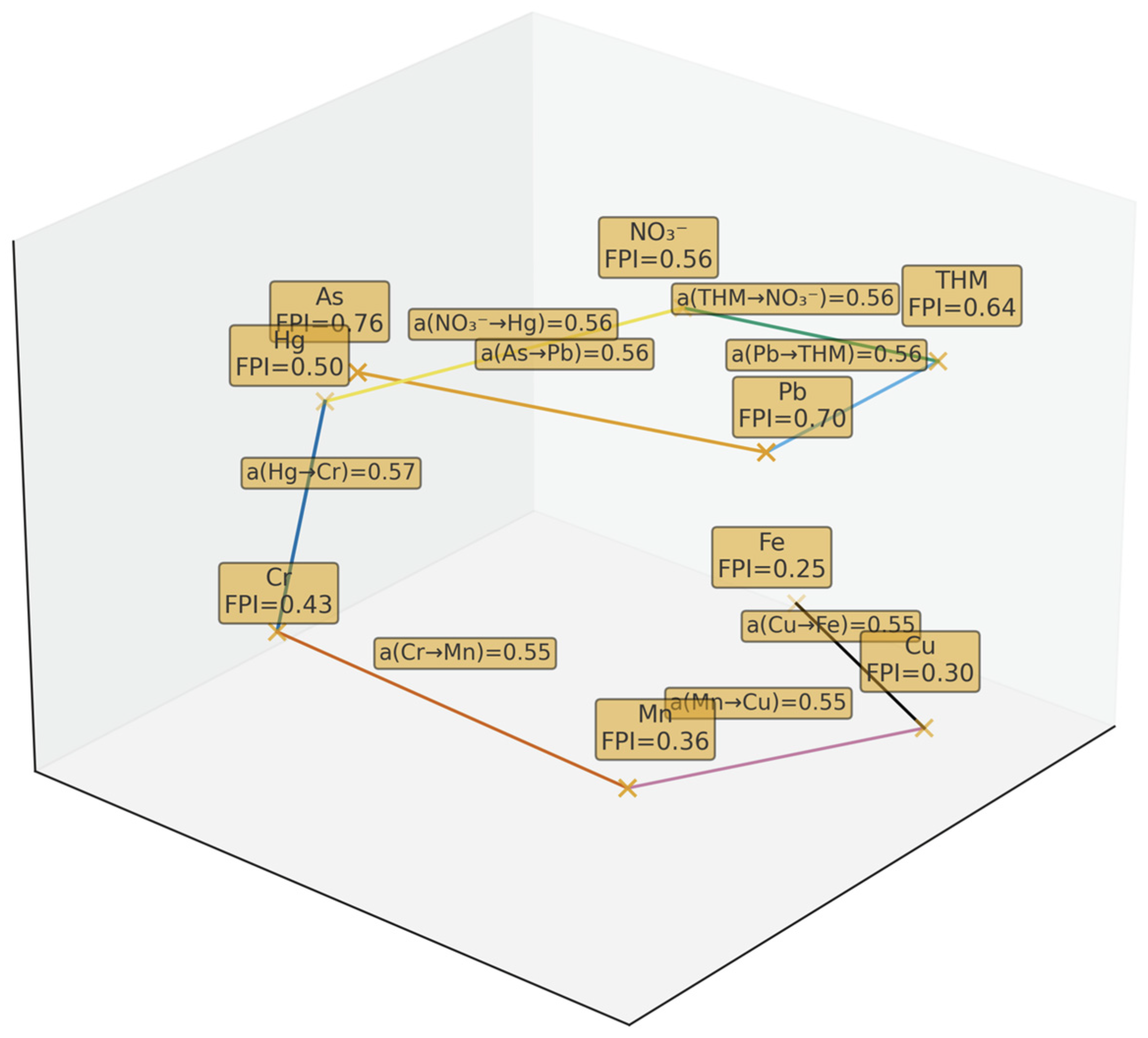

2.2.6. Stage 6. Mapping Actions and Creating a Fuzzy Queue of Water Quality Parameters

- -

- The nodes (crosses with labels) are water quality parameters arranged in descending order according to FPI (from highest priority to lowest).

- -

- The edges connect neighbours in the ranking—they show how strong the local advantage of the previous parameter over the next one is.

- -

- The edge label is in the form a(i → j)—this is a value from the preference matrix: the degree to which parameter i is more important/dangerous than neighbouring parameter j (a ∈ [0, 1]; 0.50 ≈ tie).

- -

- The thickness of the line is proportional to the strength of the preference a(i → j): the thicker the line, the greater the advantage.

- -

- The colour of the line is used to visually distinguish between levels of strength (see legend); in the black and white version, line thickness + value label are used.

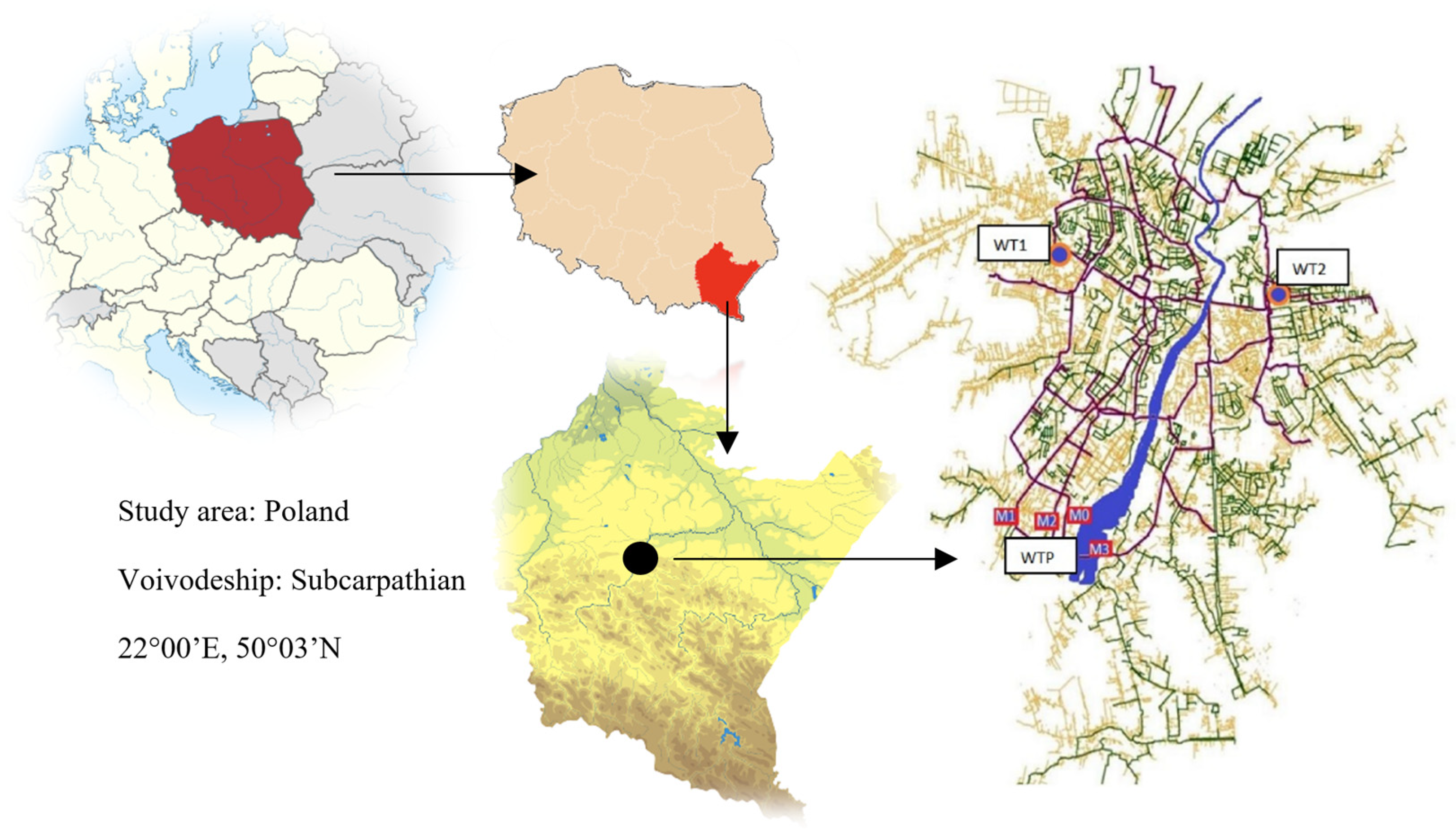

3. Characteristics of the Study Object

- (1)

- Initial ozonation—oxidation of colour, taste, and odour compounds and initial disinfection (ozone generated from oxygen);

- (2)

- Coagulation (aluminium salts)—removal of colloids and poorly settling suspensions affecting turbidity and colour (e.g., humic substances, silica, organic pollutants);

- (3)

- Sedimentation in horizontal settling tanks—separation of flocs formed during coagulation;

- (4)

- Filtration through sand and anthracite–sand beds—removal of fine particulates;

- (5)

- Intermediate ozonation—further oxidation of residual colour/taste/odour compounds and reinforcement of disinfection;

- (6)

- Granular activated carbon (GAC) filtration—removal of dissolved organics and reduction of selected micro-pollutants;

- (7)

- UV pre-disinfection—enhancement of microbiological stability, improvement of organoleptic qualities, and reduction in chlorination doses;

- (8)

- Final disinfection with chlorine compounds (chlorine dioxide and chlorine gas)—ensuring sanitary quality in the distribution network; chlorine dioxide is produced in situ from sodium chlorite and chlorine gas;

- (9)

- pH correction using sodium carbonate (as needed)—mitigation of corrosivity in the distribution system.

4. Results

- -

- regulatory significance—all are included in the catalogue of parameters of Directive (EU) 2020/2184 [7], with specified parametric values (Part B—chemical parameters; Fe and Mn as indicator parameters in Part C) or monitoring guidelines.

- -

- the diversity of risk-creating mechanisms, which allows for reliable testing of the proposed prioritisation methodology:

- carcinogenicity (As, Cr(VI), part of DBP/THM),

- neurotoxicity and developmental effects (Pb, Hg, Mn),

- acute effects in infants (NO3−),

- gastrointestinal effects and metallic taste (Cu),

- nuisances/secondary operational risks (Fe, Mn).

- -

- operational challenges in European water supply systems: corrosion and metal leaching from installations, water ageing, seasonal variability of NO3− parameters, prevailing hydraulic conditions.

- -

- availability of data from routine water quality monitoring programmes for water supply systems, which facilitates the use of the method in other cities.

- -

- aij ∈ [0, 1]—degree of preference of i over j.

- -

- additive reciprocity: aij + aji = 1 for i ≠ j

- -

- diagonal in the matrix: aii = 0.5 (no preference for i over i).

- -

- only ratings for pairs i < j (upper triangle) were collected. Values for j < i were automatically reconstructed based on the rule: aji = 1 − aij.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization; UNICEF. Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2000–2020: Five Years into the SDGs; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, S.D.; Postigo, C. Drinking Water Disinfection By-products. In The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry Emerging Organic Contaminants and Human. Health; Ferreira, N., Saraiva, D.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 93–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzenbach, R.P.; Egli, T.; Hofstetter, T.B.; von Gunten, U.; Wehrli, B. Global water pollution and human health. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fewtrell, L.; Bartram, J. Water Quality: Guidelines, Standards & Health; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, R.; Villanueva, C.M.; Beene, D.; Cradock, A.L.; Donat-Vargas, C.; Lewis, J.; Martinez-Morata, I.; Minovi, D.; Nigra, A.E.; Olson, E.D.; et al. US drinking water quality: Exposure risk profiles for seven legacy and emerging contaminants. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2024, 34, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality, 4th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-92-4-004506-4. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2020 on the quality of water intended for human consumption (recast). Off. J. EU 2020, L 435, 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Minister of Health. Regulation of the Minister of Health of 7 December 2017 on the quality of water intended for human consumption. J. Laws 2017, 2294. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20170002294 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Kavcar, P.; Odabasi, M.; Kitis, M.; Inal, F.; Sofuoglu, S. Occurrence, oral exposure and risk assessment of volatile organic compounds in drinking water for İzmir. Water Res. 2006, 40, 3219–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awais, M.; Aslam, B.; Maqsoom, A.; Khalil, U.; Ullah, F.; Azam, S.; Imran, M. Assessing Nitrate Contamination Risks in Groundwater: A Machine Learning Approach. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozísek, F. Influence of nitrate levels in drinking water on urological malignancies: A community-based cohort study. BJU Int. 2007, 99, 1550–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna-Attisha, M.; LaChance, J.; Sadler, R.C.; Champney Schnepp, A. Elevated blood lead levels in children associated with the Flint drinking water crisis: A spatial analysis of risk and public health response. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, G.K. Lead in drinking water and health. Sci. Total Environ. 1981, 18, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.H.; Lingas, E.O.; Rahman, M. Contamination of drinking-water by arsenic in Bangladesh: A public health emergency. Bull. World Health Organ. 2000, 78, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Herath, I.; Vithanage, M.; Bundschuh, J.; Maity, J.P.; Bhattacharya, P. Natural Arsenic in Global Groundwaters: Distribution and Geochemical Triggers for Mobilization. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2016, 2, 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose-O’Reilly, S.; McCarty, K.M.; Steckling, N.; Lettmeier, B. Mercury exposure and children’s health. Curr. Probl. Paediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2010, 40, 186–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, C.M.; Cantor, K.P.; Kogevinas, M.; Grimalt, J.O.; Malats, N.; Silverman, D.; Tardon, A.; Garcia-Closas, R.; Serra, C.; Carrato, A.; et al. Bladder cancer and exposure to water disinfection by-products through ingestion, bathing, showering, and swimming in pools. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 165, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchard, M.F.; Bellinger, D.C.; Sauvé, S.; Barbeau, B.; Legrand, M.; Brodeur, M.E.; Bouffard, T.; Limoges, E.; Mergler, D. Intellectual impairment in school-age children exposed to manganese from drinking water. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teksoy, A.; Özyiğit, M.E. A Study on the Use of Copper Ions for Bacterial Inactivation in Water. Water 2025, 17, 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Nong, X.; Xia, H.; Liu, H.; Zhong, L.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, W.; Lu, Y. Integrating Water Quality Index (WQI) and multivariate statistics for regional surface water quality evaluation: Key parameter identification and human health risk assessment. Water 2024, 16, 3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, I.; Goncalves, A.M.; Pedra, A.C. Risk assessment for the surface water quality evaluation of a hydrological basin. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2024, 38, 4527–4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachroud, M.; Trolard, F.; Kefi, M.; Jebari, S.; Bourrié, G. Water Quality Indices: Challenges and Application Limits in the Literature. Water 2019, 11, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.I.; Sadiq, R. Risk-based prioritization of air pollution monitoring using fuzzy synthetic evaluation technique. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2005, 105, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegede, D.O.; Oladeji, O.J.; Adeniyi Afolabi, T.; Oyedotun Agunbiade, F.; Remilekun Gbadamosi, M.; Sojinu, S.O.; Ojekunle, O.Z.; Varanusupakul, P. Fuzzy logic modelling of the pollution pattern of potentially toxic elements and naturally occurring radionuclide materials in quarry sites in Ogun State, Nigeria. Environ. Geochem. Health 2025, 47, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, P.; Mendoza, E. A fuzzy logic technique for the environmental impact assessment of marine renewable energy power plants. Energies 2025, 18, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control. 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, H.-J. Fuzzy Set Theory—and Its Applications, 4th ed; Kluwer Academic: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Klir, G.J.; Yuan, B. Fuzzy Sets and Fuzzy Logic: Theory and Applications; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Chiclana, F.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Alonso, S.; Marques Pereira, R.A.; Alberto, R. Preferences and Consistency Issues in Group Decision Making; Studies in Fuzziness and Soft Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; p. 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H. Additively Consistent Interval-Valued Intuitionistic Fuzzy Preference Relations and Their Application to Group Decision Making. Information 2018, 9, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-M. Centroid defuzzification and the maximizing set and minimizing set ranking based on alpha level sets. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2009, 57, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzegar, Y.; Gorelova, I.; Bellini, F.; D’ascenzo, F. Drinking Water Quality Assessment Using a Fuzzy Inference System Method: A Case Study of Rome (Italy). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lermontov, A.; Yokoyama, L.; Lermontov, M.; Ribeiro de Carvalho, D. River quality analysis using fuzzy water quality index: Ribeira do Iguape river watershed, Brazil. Ecol. Indic. 2009, 9, 1188–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trach, R.; Trach, Y.; Kiersnowska, A.; Kiersnowska, A.; Lendo-Siwicka, M.; Lendo-Siwicka, K. A Study of Assessment and Prediction of Water Quality Index Using Fuzzy Logic and ANN Models. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Wątróbski, J.; Faizi, S.; Rashid, T.; Tarczyńska-Łuniewska, M. Sustainable decision making using a consensus model for consistent hesitant fuzzy preference relations—water allocation management case study. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebre, S.L.; Cattrysse, D.; Van Orshoven, J. Multi-criteria decision-making methods to address water issues: A state-of-the-art review. Water 2021, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internal technical documentation provided by the Municipal Water Utility (CWSS), 2022.

- Internal technical documentation provided by the Municipal Water Utility (CWSS), 2023.

- Internal technical documentation provided by the Municipal Water Utility (CWSS), 2024.

| Parameter | Main Health Effects | Technological Criterion | Priority Level (Rank 1–5) | Justification | Action Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic (As) | Highly carcinogenic (skin, bladder and lung cancer), skin lesions, | None | 5 | One of the most dangerous parameters, documented health effects with chronic exposure. | Immediate corrective action; suspension of supply or switching of source; implementation of advanced technologies (adsorption, membranes); priority monitoring and reporting. |

| Lead (Pb) | Neurotoxicity (children), developmental disorders, hypertension, nephrotoxicity | corrosion of installations | 5 | High toxicological significance, especially in sensitive groups. | Elimination of the source (replacement of lead installations, corrosion control); child health protection programmes; intensive monitoring and consumer information. |

| Mercury (Hg) | Neurotoxicity, kidney damage, foetal effects | None | 4 | Highly toxic, but rarely exceeds standards in water supplies. | Increased monitoring frequency; identification of the source of contamination; implementation of reduction technologies (e.g., ion exchange); notifications in case of exceedances. |

| THM (Trihalomethanes) | Cancer risk (bladder, intestine), inhalation and dermal effects | Disinfection by-product | 4 | Commonly found, risk signals even at concentrations below EU standards. | Optimization of the disinfection process (contact time, chloramination, DBP precursors); implementation of technologies limiting the formation of THM (GAC, ozone, biological filtration); monitoring at network points. |

| Nitrates (NO3−) | Methaemoglobinaemia (infants), possible links to stomach cancer | insignificant | 4 | Very important parameter in agriculture; high risk for infants. | Monitoring in agricultural areas; identification of sources of inflow (sewage, fertilisers); alternative water sources for infants; implementation of desalination/denitrification in treatment. |

| Chromium (Cr) | Carcinogenic (Cr(VI)), toxic to kidneys and liver | Industrial nature | 3 | Significant toxicologically, but exceedances in water supply systems are rare. | Periodic monitoring; testing of industrial sources; contingency plan in case of increased concentrations; implementation of reduction technologies (e.g., reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) + coagulation). |

| Copper (Cu) | Diarrhoea, liver damage with chronic exposure | corrosion of installations | 2 | Significant mainly in the case of long-term exceedances in domestic installations. | Monitoring of internal installations (corrosion of copper pipes); operating recommendations (flushing of the network, pH control); measures to be taken in the event of long-term exceedances. |

| Manganese (Mn) | Neurotoxicity (children), developmental disorders | sediment, secondary contamination | 2 | Moderate health risk, more often an aesthetic and technological problem. | Regular rinsing of nets; use of filtration in treatment plants; measures mainly in the case of aesthetic problems and secondary contamination. |

| Iron (Fe) | No significant health effects (except for haemochromatosis in high doses) | colour, taste, sediment | 1 | Secondary parameter, more of a visual quality issue than a toxicological one. | Measures to reduce sediment and colour (iron removal, network flushing); response to consumer complaints; maintaining the |

| As | Pb | THM | … | |

| As | 0.5 | a12 | a13 | … |

| Pb | 1 − a12 | 0.5 | a23 | … |

| THM | 1 − a13 | 1 − a23 | 0.5 | … |

| … | … | … | … | … |

| FPI Range | Priority Category |

|---|---|

| <0.20 | Very low (VL) |

| 0.20–0.40 | Low (L) |

| 0.40–0.60 | Medium (M) |

| 0.60–0.80 | High (H) |

| ≥0.80 | Very high (VH) |

| FPI Range | Priority Category | Proposed Actions |

|---|---|---|

| <0.20 | Very low (VL) | Routine monitoring; action only in response to complaints/aesthetic nuisances. |

| 0.20–0.40 | Low (L) | Planned monitoring; analysis in case of upward trends; local action. |

| 0.40–0.60 | Medium (M) | Periodic in-depth investigations; source analysis; targeted corrosion/precursor control. |

| 0.60–0.80 | High (H) | Increased monitoring frequency; optimisation/implementation of removal technologies (e.g., GAC, membranes, denitrification); notifications in case of exceedances. |

| ≥0.80 | Very high (VH) | Immediate corrective action; possible suspension of supply/switching of source; advanced technologies; priority reporting and supervision. |

| Parameter | Risk Group | Health/Operational Justification | Regulatory Comments (WHO/DWD) [1,6,7,8] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrates (NO3−) | Inorganic pollutants (agriculture) | Methaemoglobinaemia in infants; possible thyroid disorders; strong | WHO: 50 mg/L; DWD: 50 mg/L |

| Lead (Pb) | Heavy metal (installation materials) | Developmental neurotoxicity, increased cardiovascular RR; release from lead fittings and fixtures | DWD: 5 μg/L from 12 January 2036 (until then 10 μg/L; 5 μg/L when using new materials in internal installations). |

| Arsenic (As) | Metalloids (geogenic) | Carcinogen (skin, bladder, lungs); chronic exposure | WHO: 10 μg/L DWD: 10 μg/L |

| Chromium (Cr; toxicologically mainly Cr(VI)) | Heavy metal | Caution regarding carcinogenicity | DWD: 25 μg/L from 2036 (until then 50 μg/L) |

| Copper (Cu) | Metal (installation materials) | Potential hepatotoxicity with chronic exposure; depends on pH/alkalinity and water stagnation in pipes | DWD: 2 mg/L |

| Manganese (Mn) | Metal (water supply network material) | Neurodevelopmental risk in children, sediment formation, discolouration; promotes biofilm formation | DWD: indicator value 50 μg/L (indicator parameter—operational significance) |

| Iron (Fe) | Metal (water supply network material) | Nuisance (colour, taste), deposits, risk of secondary quality degradation; significant impact on consumer complaints | WHO: parameter Aesthetic DWD: indicator 200 μg/L |

| THM—total | Disinfection by-products (DBPs) | Increased risk of bladder cancer (chronic exposure); dependent on water temperature and age | WHO: individual guidelines DWD: total 100 μg/L (chloroform, bromoform, dibromochloromethane, bromodichloromethane). |

| Comparison Pair Number | Parameter_i | Parameter_j | Expert Assessment 1 | Expert Assessment 2 | Expert Assessment 3 | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P01 | As | Pb | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.56 |

| P02 | As | THM | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.59 |

| P03 | As | NO3− | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.68 |

| P04 | As | Hg | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| P05 | As | Cr | 0.74 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

| P06 | As | Mn | 0.82 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| P07 | As | Cu | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| P08 | As | Fe | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| P09 | Pb | THM | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.56 |

| P10 | Pb | NO3− | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.60 | 0.60 |

| P11 | Pb | Hg | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.71 |

| P12 | Pb | Cr | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.75 |

| P13 | Pb | Mn | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.76 | 0.80 |

| P14 | Pb | Cu | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.87 |

| P15 | Pb | Fe | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| P16 | THM | NO3− | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.56 |

| P17 | THM | Hg | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| P18 | THM | Cr | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.67 |

| P19 | THM | Mn | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| P20 | THM | Cu | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| P21 | THM | Fe | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| P22 | NO3− | Hg | 0.54 | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.56 |

| P23 | NO3− | Cr | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.59 |

| P24 | NO3− | Mn | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 0.68 |

| P25 | NO3− | Cu | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| P26 | NO3− | Fe | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.79 |

| P27 | Hg | Cr | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.57 |

| P28 | Hg | Mn | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.63 |

| P29 | Hg | Cu | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.69 |

| P30 | Hg | Fe | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.76 |

| P31 | Cr | Mn | 0.62 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| P32 | Cr | Cu | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.64 | 0.61 |

| P33 | Cr | Fe | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.66 |

| P34 | Mn | Cu | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| P35 | Mn | Fe | 0.64 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.59 |

| P36 | Cu | Fe | 0.59 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| As | Pb | THM | NO3− | Hg | Cr | Mn | Cu | Fe | |

| As | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.79 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Pb | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.90 |

| THM | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.8 | 0.85 |

| NO3− | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.68 | 0.7 | 0.79 |

| Hg | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.57 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.76 |

| Cr | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.61 | 0.66 |

| Mn | 0.14 | 0.2 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.59 |

| Cu | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.55 |

| Fe | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.50 |

| Parameter | FPI | μ(VL) | μ(L) | μ(M) | μ(H) | μ(VH) | Score (COGS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | 0.76 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 0.10 | 0.73 |

| Pb | 0.70 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.70 |

| THM | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.68 |

| NO3− | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.52 |

| Hg | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 |

| Cr | 0.43 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.46 |

| Mn | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.32 |

| Cu | 0.30 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.30 |

| Fe | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.30 |

| Parameter | FPI | Score | Priority Category | Operational Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | 0.76 | 0.72 | High (H) | Immediate corrective action; suspension of supply or switching of source; implementation of advanced technologies (adsorption, membranes); priority monitoring and reporting. |

| Pb | 0.7 | 0.7 | High (H) | Elimination of the source (replacement of lead installations, corrosion control); child health protection programmes; intensive monitoring and consumer information. |

| THM (total) | 0.64 | 0.68 | High (H) | Optimization of the disinfection process (contact time, chloramination, DBP precursors); implementation of technologies limiting the formation of THM (GAC, ozone, biological filtration); monitoring at network points. |

| NO3− | 0.56 | 0.52 | Medium (M) | Monitoring in agricultural areas; identification of sources of inflow (sewage, fertilisers); alternative water sources for infants; implementation of desalination/denitrification in treatment. |

| Hg | 0.5 | 0.50 | Medium (M) | Increased monitoring frequency; identification of pollution sources; implementation of reduction technologies (e.g., ion exchange); notifications in case of exceedances. |

| Cr | 0.43 | 0.46 | Medium (M) | Periodic monitoring; testing of industrial sources; contingency plan in case of increased concentrations; implementation of reduction technologies (e.g., reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) + coagulation). |

| Mn | 0.36 | 0.32 | Low (L) | Regular flushing of the network; use of filtration in treatment plants; measures mainly in the case of aesthetic problems and secondary contamination. |

| Cu | 0.3 | 0.3 | Low (L) | Monitoring of internal installations (corrosion of copper pipes); operational recommendations (flushing the network, pH control); measures in the event of prolonged exceedances. |

| Fe | 0.25 | 0.3 | Low (L) | Measures to reduce deposits and colour (iron removal, network flushing); response to consumer complaints; maintaining the aesthetics and acceptability of water. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piegdoń, I.; Tchórzewska-Cieślak, B.; Raček, J. A New Fuzzy Preference Relation (FPR) Approach to Prioritizing Drinking Water Hazards: Ranking, Mapping, and Operational Guidance. Water 2025, 17, 3410. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233410

Piegdoń I, Tchórzewska-Cieślak B, Raček J. A New Fuzzy Preference Relation (FPR) Approach to Prioritizing Drinking Water Hazards: Ranking, Mapping, and Operational Guidance. Water. 2025; 17(23):3410. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233410

Chicago/Turabian StylePiegdoń, Izabela, Barbara Tchórzewska-Cieślak, and Jakub Raček. 2025. "A New Fuzzy Preference Relation (FPR) Approach to Prioritizing Drinking Water Hazards: Ranking, Mapping, and Operational Guidance" Water 17, no. 23: 3410. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233410

APA StylePiegdoń, I., Tchórzewska-Cieślak, B., & Raček, J. (2025). A New Fuzzy Preference Relation (FPR) Approach to Prioritizing Drinking Water Hazards: Ranking, Mapping, and Operational Guidance. Water, 17(23), 3410. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233410