1. Introduction

Amidst the accelerating global urbanization and population growth, the generation of municipal solid waste (MSW) has escalated dramatically, presenting a critical challenge to environmental sustainability [

1,

2]. While the “waste-free city” initiatives and mandatory waste sorting policies (e.g., in Shanghai) have standardized management, they have also concentrated high-moisture food waste, leading to a significant surge in food waste leachate (FWL) production [

3]. FWL is rich in organic matter, heavy metals, and inorganic salts; if not properly treated, it will become a severe source of secondary pollution, posing serious problems to water bodies and groundwater resources [

4]. However, its high biodegradability also endows it with extremely high potential for resource utilization [

5]. Anaerobic digestion (AD), capable of synergistically achieving waste reduction, harmless treatment, and bioenergy (e.g., methane) production, has become the mainstream technology for treating high-concentration organic wastewater [

6]. Nevertheless, the mono-digestion of FWL often faces challenges such as unstable gas production, susceptibility to acidification, and low methane yield [

7]. Anaerobic co-digestion, by introducing two or more synergistic substrates, can effectively balance the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, dilute toxic substances, and enhance the system’s buffering capacity, thereby overcoming the drawbacks of mono-digestion [

8].

Parallel to the organic waste crisis, global concerns regarding plastic pollution and the proliferation of plastics have intensified, prompting strict “plastic bans” and driving the transition toward biodegradable plastics (BPs) like polylactic acid (PLA) and poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) [

9,

10,

11]. Although BPs offer a potential alternative to petroleum-based plastics, they are not a panacea. Their degradation in natural environments remains slow, and without proper management, they may still contribute to plastic accumulation. Studies have found that some plastics can increase methane production during anaerobic co-digestion with FWL, while also exerting certain effects on anaerobic microorganisms [

12]. Therefore, anaerobically co-digesting BP and FWL, which achieves a dual benefit in waste treatment, represents a highly attractive research direction. However, a critical bottleneck exists in the “asynchronous degradation” of these substrates. BPs typically require up to 90 days for degradation, whereas FWL degrades rapidly within 25–30 days [

13]. To bridge this gap, recent innovations have focused on enzyme-modified plastics—directly embedding enzymes into the BP matrix—which has shown promise in accelerating hydrolysis under composting conditions, though its efficacy in AD systems remains to be fully explored [

14].

Beyond process optimization, accurate modeling is indispensable for the scale-up and control of this complex co-digestion system. Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) tests serve as the basis for evaluating substrate biodegradability, while kinetic models are utilized to analyze its degradation rates and rate-limiting steps [

15,

16]. However, traditional kinetic models rely on numerous simplified assumptions, making it difficult to capture the complex effects of multivariate interactions (e.g., temperature, pH, substrate composition) on the methanogenesis process, which results in limited prediction accuracy. Conversely, data-driven machine learning (ML) algorithms have demonstrated superior accuracy in mapping complex non-linear relationships [

17]. Yet, the inherent “black-box” nature of ML models results in poor interpretability, making it difficult to deduce the underlying biological mechanisms or provide reliable guidance for process diagnostics.

To address the limitations of both deterministic and purely data-driven approaches, the integration of domain knowledge into machine learning—specifically Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs)—has garnered increasing attention [

18]. The fundamental concept of using neural networks to solve differential equations was first proposed by Lagaris et al. [

19]. Building on this, Raissi et al. formally established the PINN framework, demonstrating its capability to solve forward and inverse problems involving non-linear partial differential equations [

20]. Pure ML models, lacking physical constraints, may generate predictions that violate fundamental laws (e.g., mass balance) when training data is scarce or noisy [

21]. PINN resolves this by embedding physical laws directly into the neural network’s loss function as regularization terms [

22]. This hybrid architecture compels the model to adhere to known biological principles while learning from data, thereby significantly enhancing generalization capability, physical consistency, and interpretability. Despite its potential, the application of PINN in complex anaerobic co-digestion systems involving modified materials remains largely uncharted.

In view of these scientific gaps, this study aims to advance both the process technology and the modeling framework for organic waste treatment. First, we investigated the anaerobic co-digestion performance of plastics modified with three specific enzymes (Proteinase K, Porcine Pancreatic Lipase, and Amylase) and FWL under both mesophilic and thermophilic conditions. Subsequently, based on the experimental data, we systematically evaluated the predictive performance of traditional kinetic models versus various ML models (SVR, GBR, XGBoost, ANN). Innovatively, a PINN model incorporating Modified Gompertz kinetic constraints was constructed. The specific objectives are: (1) to elucidate the methane enhancement potential of enzyme-modified plastics in co-digestion; and (2) to establish a robust hybrid model that synergizes high prediction accuracy with physical interpretability, providing a novel tool for the intelligent management of mixed organic waste.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Anaerobic Co-Digestion Methane Potential of Enzyme-Modified BP and FWL

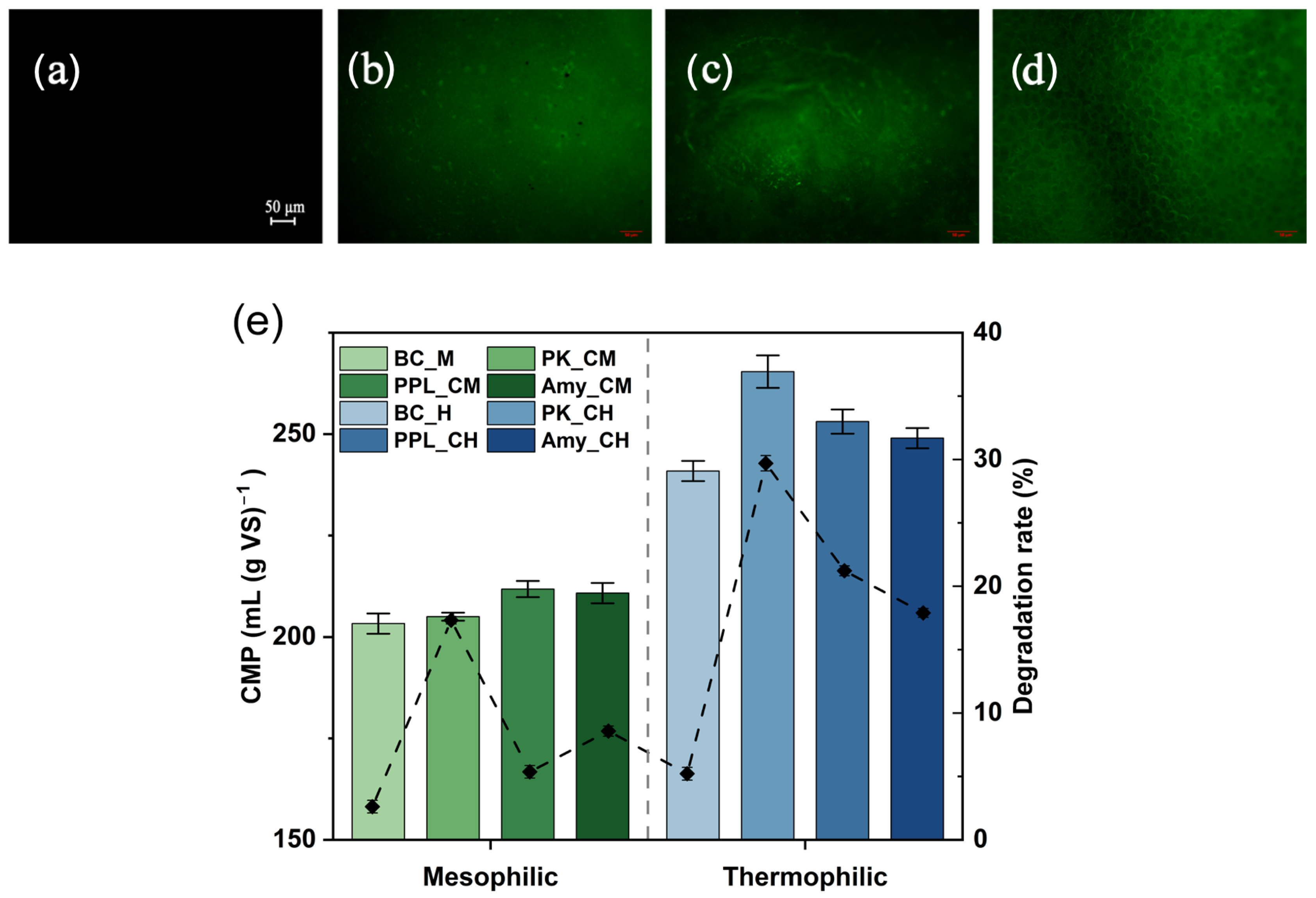

The modified BP was characterized using fluorescence microscopy, wherein green fluorescence indicated the presence of protein components (

Figure 1a–d). Before the experiment, no fluorescence was observed on the surfaces of the unmodified BP. In contrast, the surfaces of all enzyme-modified BP samples exhibited green fluorescence before the experiment. This result demonstrates that PK, PPL, and Amy were successfully loaded onto the surfaces of the enzyme-modified BP.

The cumulative methane production (CMP) on day 30 (

Figure 1e) revealed the differential impacts of various modified BPs on the anaerobic co-digestion of FWL. Compared to the control groups (Mesophilic: 203.3 mL (g VS)

−1; Thermophilic: 240.9 mL (g VS)

−1), the addition of modified BP significantly enhanced methane production performance, particularly under thermophilic conditions (PK_CH group: 265.4 mL (g VS)

−1). ANOVA confirmed that significant differences existed among treatment groups under both temperatures (F = 39.29–496.00), indicating that the type of modified BP was a key factor (

Table 2). This performance enhancement may be attributed to the functional enzymes (e.g., PK, PPL, Amy) released from the self-hydrolysis of the modified BP, which synergistically accelerated the hydrolysis of both FWL and BP. Additionally, under thermophilic conditions, the degradation rates (mass loss rate) of BPs across all groups were generally higher than those under mesophilic conditions. Furthermore, the degradation rates of enzyme-modified BPs were significantly higher than those of the control group. For instance, the degradation rates of PK_CH, PPL_CH, and Amy_CH BPs were significantly higher than that of BC_H (5.21%), with PK_CH exhibiting the highest rate at 29.70% (

Figure 1e). Therefore, the superiority of thermophilic conditions stemmed from a higher plastic degradation rate (releasing more monomers), potentially more efficient microbial communities, and a more favorable enzymatic environment. Particularly under thermophilic conditions, the high significance of the F-value further highlighted that the substrate specificity of the enzymes was central to determining methanogenic efficiency. PK is capable of specifically hydrolyzing proteins, while PPL and Amy exhibit specific degradation capabilities for lipids and starches, respectively [

37,

38,

39]. Simultaneously, anaerobic microorganisms demonstrate a critical demand for ammonia nitrogen during their metabolic and growth processes [

40]. The amino acid monomers derived from protein hydrolysis by PK provide a robust foundation for microbial metabolism and proliferation, which likely explains why the methane yield under thermophilic conditions was significantly higher than that of other groups. However, the sensitivity of enzyme activity (particularly PK) to temperature attenuated this specificity-driven enhancement effect under mesophilic conditions.

3.2. Kinetic Model Construction for Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Enzyme-Modified BP and FWL

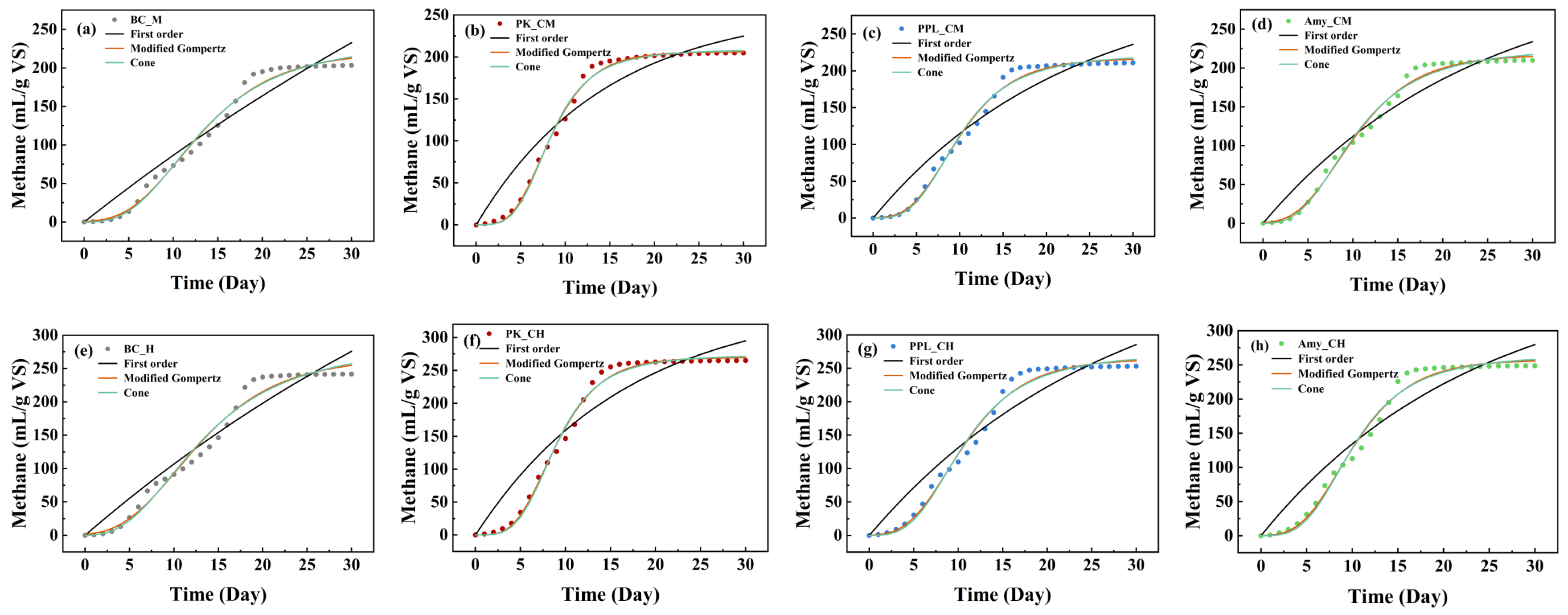

To further elucidate the kinetic characteristics of the BMP test, this study employed the First-order, Modified Gompertz, and Cone models to fit and analyze the 30-day experimental data. The fitting results of the model’s kinetic parameters are summarized in

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5, and the comparison between the model-predicted curves and the experimental data is shown in

Figure 2. The goodness-of-fit of the models was evaluated by comparing statistical indicators such as the coefficient of determination (R

2), Residual Sum of Squares (RSS), and Root Mean Square Error (rMSE). The results showed that the R

2 values of the First-order model were relatively low, and its RSS and rMSE values fluctuated significantly across samples, indicating its limited predictive ability in describing the complex methane generation process. In contrast, both the Modified Gompertz model and the Cone model demonstrated extremely high fitting accuracy, with R

2 values generally approaching 1.0, while their RSS and rMSE values remained at low levels. In terms of parameter identifiability and stability, the parameters of the First-order model (such as k and f

d) are relatively simple, but they showed large variations among different samples, indicating poor stability. Although the Modified Gompertz model (f

d, R

m, λ) and the Cone model (k and n) have more complex structures, their parameter estimates exhibited higher consistency across different samples. Particularly, the parameters of the Modified Gompertz model possess clear biological significance (e.g., maximum methane potential, maximum methane production rate, lag phase), granting them high identifiability. Overall, the Modified Gompertz and Cone models were significantly superior to the First-order model in terms of goodness-of-fit, parameter stability, and universality (adaptability to different substrates and conditions).

Among the models studied, the Modified Gompertz model exhibited the lowest RSS, rMSE, and AIC values in all fittings, and was selected as the optimal kinetic model to describe this anaerobic co-digestion system. The superior performance of the Modified Gompertz model can be attributed to its structural inclusion of the lag phase parameter. In the co-digestion system containing enzyme-modified plastics, the hydrolysis of solid polymer matrices and the subsequent colonization by microorganisms require a distinct initialization period. Unlike the First-order model, which assumes instantaneous degradation, the Modified Gompertz model accurately captures this biological adaptation phase, resulting in a better fit for the sigmoidal methane production curves observed. It is noteworthy that although hydrolysis is often considered the rate-limiting step in anaerobic digestion [

41,

42], the excellent fit of the Modified Gompertz model (rather than the hydrolysis-based First-order model) suggests that hydrolysis may not be the key rate-limiting step in this enzyme-enhanced co-digestion system. The fitted parameter f

d (predicted maximum methane yield) of the optimal model showed a trend highly consistent with the BMP experimental observations. For instance, the f

d under thermophilic conditions was significantly higher than under mesophilic conditions, and the PK_CH group exhibited the highest methane potential. Furthermore, the numerical patterns of parameters R

m (maximum methane production rate) and λ (lag phase) clearly quantified the differences in methane generation rates among the treatment groups, which kinetically explains why the PK_CH group could produce more methane in a shorter time (λ was shorter) and at a higher rate (R

m was higher) [

43].

Although the First-order model had a poor goodness-of-fit, its parameter (the k-value, representing the hydrolysis rate constant [

44]) can still provide valuable supporting evidence. The data show that the k-value of the PK_CH group was much larger than that of the control group BC_H, while the R

2 value of its First-order model fit was also lower. This phenomenon precisely indicates that the addition of PK-modified BP greatly accelerated the system’s hydrolysis rate, causing the hydrolysis reaction to no longer be the sole rate-limiting step of the system. Therefore, the First-order model, which is based on a single hydrolysis rate limitation, was no longer applicable. This also corroborates, from a kinetic perspective, the experimental observation that enzyme-modified BP can significantly enhance anaerobic co-digestion methane production.

3.3. Machine Learning Model Construction for Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Enzyme-Modified BP and FWL

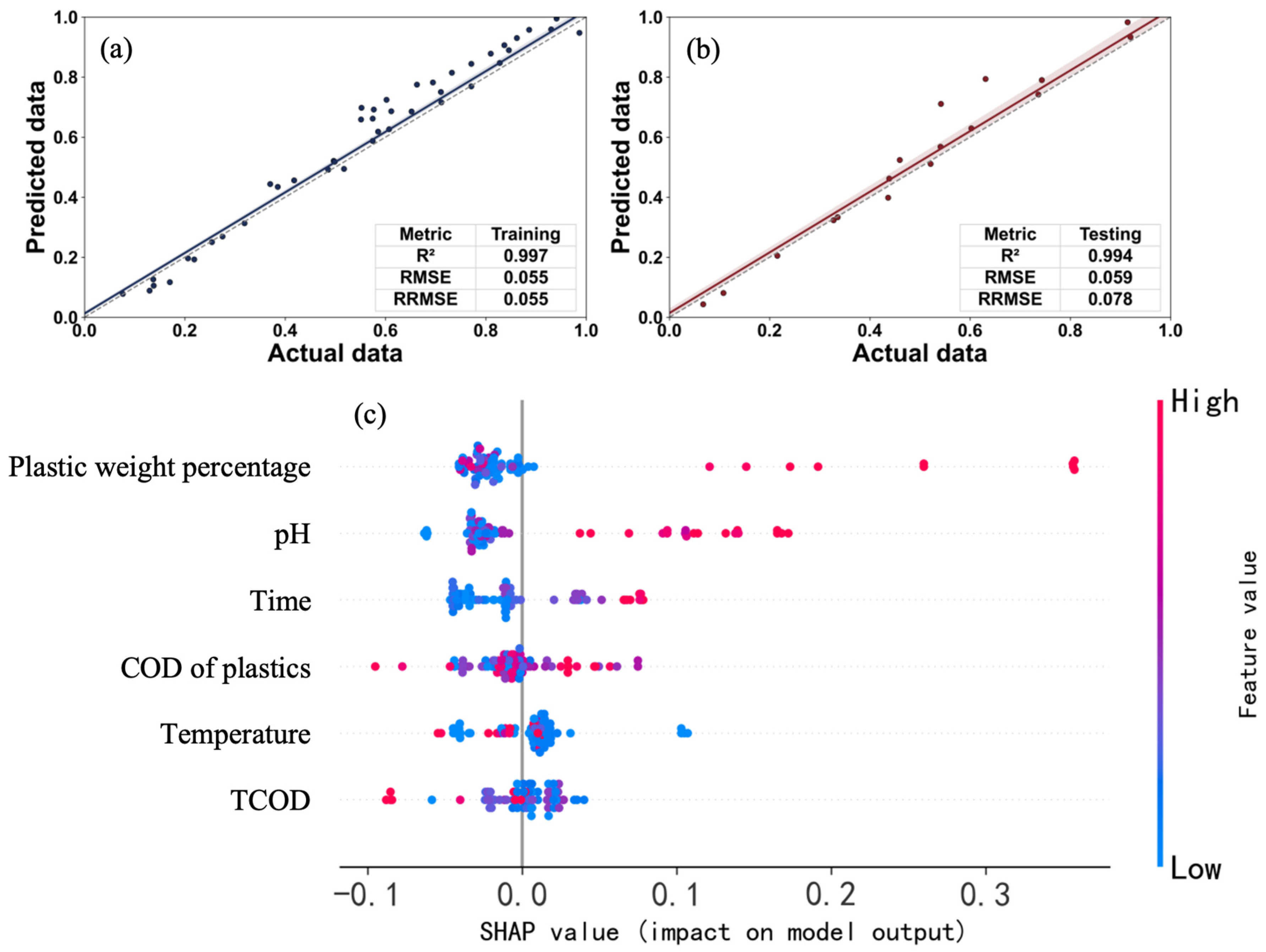

To overcome the limitations of kinetic models in handling multivariate interactions, four machine learning models (SVR, GBR, XGBoost, and ANN) were constructed to predict methane production. The performance of these models varied significantly regarding generalization ability (

Figure 3). Both SVR and XGBoost exhibited distinct signs of overfitting. While XGBoost achieved a perfect fit on the training set (R

2 = 1), its performance on the test set dropped significantly, and SVR similarly showed a sharp decline in from 0.994 (training) to 0.905 (testing). This discrepancy suggests that these models captured noise specific to the training data rather than the underlying universal biological patterns, resulting in poor generalization to unseen data. Although GBR mitigated overfitting to some extent through ensemble learning, its prediction accuracy was surpassed by the ANN model.

The ANN model showed a good goodness-of-fit on the training set (R2 = 0.946). Notably, the model demonstrated superior performance on the test set (R2 = 0.958), indicating its excellent generalization ability, which was significantly better than the SVR and XGBoost models. This phenomenon, where the test set performance slightly exceeds the training set performance, is likely attributed to the effective implementation of regularization techniques during the training phase. Regularization introduces constraints to prevent overfitting, which may slightly suppress the training scores. However, these constraints are typically deactivated during the testing phase, allowing the model to utilize its full predictive capacity. Furthermore, the random partitioning of the dataset might have resulted in a test set containing data points with distribution characteristics that are slightly easier for the model to generalize compared to the training set. The RMSE and RRMSE of the ANN model on both the training and test sets remained at low levels, and the gap between them was minimal, which jointly confirmed the model’s strong robustness. This excellent generalization performance (i.e., test set performance surpassing training set performance) is likely attributed to effective regularization techniques and appropriate selection of model complexity. This allowed the ANN to successfully capture the complex non-linear relationships in the data via multiple neuron layers and activation functions, while effectively avoiding the overfitting trap, thus achieving an ideal balance between model complexity and generalization performance. Based on the ANN model, the optimized process conditions were predicted to betemperature 35 °C, pH 8.1, TCOD 64.64 g L−1, SCOD 13.38 g L−1, fermentation time 100 days, and a plastic weight percentage of 0.3%. Under these conditions, the predicted maximum cumulative methane yield could reach 384.4 mL (g VS)−1. It is important to acknowledge the limitations regarding the optimal digestion time suggested by the ANN optimization. Since the BMP experiments in this study were conducted for a duration of 30 days, predicting methane yields at 100 days represents an extrapolation beyond the experimental domain. The model assumes that the metabolic trends observed within the first 30 days would continue essentially linearly or asymptotically without unforeseen inhibition or substrate exhaustion. Therefore, the predicted yield at 100 days should be interpreted as a theoretical maximum potential under ideal conditions. Future long-term experimental validation is required to confirm the accuracy of predictions extending significantly beyond the training data timeframe.

However, despite the superior predictive accuracy of the ANN, purely data-driven models possess inherent limitations. Firstly, they operate as “black boxes”, lacking the transparency required to elucidate the biological mechanisms (e.g., hydrolysis rates or lag phases) driving the predictions. Secondly, without physical constraints, ML models may generate predictions that violate fundamental mass balance or kinetic laws when extrapolating beyond the training range. These limitations highlight a critical need for a modeling approach that synergizes the high accuracy of machine learning with the interpretability of kinetic principles [

45].

3.4. Construction of the Hybrid Prediction Model for Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Enzyme-Modified BP and FWL

To bridge the gap between the high predictive accuracy of the ANN and the interpretability of kinetic laws, this study constructed a novel Modified Gompertz PINN model. Unlike purely data-driven approaches, this hybrid framework explicitly embeds the Modified Gompertz kinetic equation into the neural network’s loss function as a physical constraint.

Figure 4a,b demonstrate the prediction performance of the constructed Modified Gompertz PINN model on the training and test sets. The model exhibited outstanding fitting accuracy and generalization ability, with R

2 values reaching as high as 0.997 and 0.994 on the training and test sets, respectively. Meanwhile, all error metrics were maintained at extremely low levels (e.g., test set rMSE = 0.054, test set rRMSE = 0.078). The high consistency of statistical metrics between the training and test sets strongly confirms that the model successfully avoided overfitting and possesses excellent generalization performance. This superior performance (compared to traditional neural networks) is attributed to the intrinsic mechanism of PINN (

Table 6). Traditional ANN models must search within a vast parameter space during optimization, whereas PINN embeds the Modified Gompertz kinetic equation as a physical constraint within the loss function. This physical prior knowledge effectively narrows the model’s solution space, guiding the optimization process to converge towards a solution that complies with physical laws. Consequently, the model not only learns data-driven features but also adheres to intrinsic physical mechanisms, enabling it to more accurately reflect the true biological process, thereby significantly improving prediction accuracy and robustness.

To investigate the influence mechanisms and contribution levels of each input variable on methane production prediction, this study employed SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis, with the results shown in

Figure 4c. In the SHAP plot, all input features are ranked in descending order according to their mean absolute SHAP value, which quantifies the feature’s global contribution to the model’s output. Each point in the plot represents a data sample: its position on the X-axis represents the SHAP value of that feature for that sample, where a positive SHAP value indicates a positive impact on the model output (methane production), and a negative value indicates a negative (inhibitory) impact; the color of the point represents the feature’s own normalized value (red for high feature values, blue for low feature values) [

17,

46]. According to the analysis results in

Figure 4c, plastic weight percentage is the feature with the largest contribution to methane production, followed by pH. Furthermore, the three features plastic weight percentage, pH, and time all exhibited a significant positive promotional effect on methane production. This is specifically manifested as: the vast majority of red dots (high feature values) for these three features are distributed on the positive half of the X-axis (high SHAP values), clearly indicating that a higher plastic weight percentage, a higher pH value, and a longer reaction time all lead to an increase in the model’s predicted methane production.

The SHAP analysis results revealed that plastic weight percentage and pH are the two key features with the highest contribution to methane production. The strong positive correlation of plastic weight percentage may be attributed to its role as an additional organic carbon source, increasing the total substrate supply, as biodegradable plastics are degraded by microorganisms into small-molecule organic matter under anaerobic conditions, directly increasing the total substrate available for methanogenesis. Meanwhile, the rapid degradation of certain plastics might release readily utilizable intermediate products, such as short-chain fatty acids or alcohols, which are excellent substrates for methanogens, thereby accelerating the methane generation rate. Additionally, a higher plastic percentage might also act as an environmental selection pressure, enriching microbial communities specialized in plastic degradation and enhancing their abundance and metabolic activity. As the second key factor, the positive promotional effect of pH highlights its core regulatory role in the anaerobic digestion process. This is because the optimal physiological activity range for the vast majority of anaerobic microorganisms, especially methanogenic archaea which are highly sensitive to environmental changes, lies in the neutral to slightly alkaline range (e.g., pH 6.5–8.0). Maintaining this optimal pH range is a prerequisite for ensuring efficient metabolism; moreover, a higher pH (such as the slightly alkaline conditions indicated by SHAP) implies the system possesses stronger buffering capacity, which can effectively neutralize accumulated acidic intermediates (like volatile fatty acids), thereby preventing system acidification from inhibiting the methanogenesis stage and maintaining the dynamic balance and synergy among different functional microbial groups. In the anaerobic digestion process, hydrolysis is the initial step that produces acidic intermediates and directly influences pH, and this process is extremely sensitive to pH changes. Therefore, the Modified Gompertz PINN prediction model learned from the data and identified the extreme importance of pH. This result also indirectly corroborates, from a biological perspective, the core limiting and regulatory role of the hydrolysis–acidification process on the entire anaerobic co-digestion system.