1. Introduction

Photocatalysis is an advanced oxidation process widely used for water and wastewater treatment [

1]. Titanium dioxide (TiO

2) is the most commonly employed photocatalyst due to its corrosion resistance, chemical stability, low toxicity, affordability, commercial availability, and photochemical stability [

2,

3,

4]. TiO

2 has been extensively applied for the degradation of a broad range of organic pollutants and exhibits notable bactericidal activity, particularly under ultraviolet (UV) irradiation [

5]. Upon UV exposure, TiO

2 nanoparticles absorb photons with sufficient energy to excite electrons from the valence band to the conduction band, generating electron–hole pairs. These pairs initiate redox reactions at the catalyst surface: the excited electron reduces molecular oxygen to form reactive oxygen species (ROS), while the hole oxidizes water or hydroxide ions to produce hydroxyl radicals (•OH). These ROS are non-selective, highly reactive, and capable of damaging bacterial cell walls, DNA, and biofilm matrix components [

6]. The photocatalytic reaction continues as long as UV light is supplied, making TiO

2 an effective tool for sustained disinfection [

7].

To evaluate the efficacy of photocatalytic treatment, biofilm formation, a key virulence factor, was monitored as an indicator.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (

P. aeruginosa) was selected as the model organism for assessing treatment performance. This ubiquitous Gram-negative bacterium exhibits remarkable adaptability through genetic and metabolic flexibility, enabling it to resist various stressors, including UV radiation, chemical agents, and nutrient limitation [

8].

P. aeruginosa expresses numerous virulence factors, either cell-associated (e.g., motility structures, pili) or secreted (e.g., exopolysaccharides (EPS), alginate), which play critical roles in host invasion and infection in humans, animals, and plants. This opportunistic pathogen exists in two physiological states: planktonic (free-floating cells) and sessile (biofilm-embedded cells) [

9]. Its capacity to form biofilms on diverse surfaces represents a key survival strategy, making it an ideal model for assessing post-treatment virulence factor expression and biofilm control efficiency.

The expression of many of these virulence factors, such as secondary metabolite production, swarming motility, and biofilm formation [

10], is regulated by quorum sensing (QS), a cell-to-cell communication process in which bacteria use structurally diverse autoinducers to sense population density and coordinate collective behavior [

11,

12,

13]. Three main QS systems are recognized: (i) LuxI/LuxR-like systems in Gram-negative bacteria, using acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) as signaling molecules; (ii) oligopeptide-two-component systems in Gram-positive bacteria, relying on small peptides for communication; and (iii) the luxS-encoded autoinducer-2 (AI-2) systems in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive species [

14]. These signaling molecules play a vital role in promoting the transformation of free planktonic cells into structured biofilm communities and controlling biofilm formation.

Beyond virulence factor regulation, QS also mediates the resuscitation of viable but non-culturable (VBNC) bacteria [

15]. The VBNC state is a survival strategy adopted by microorganisms under stress or extreme environmental conditions. VBNC bacteria remain metabolically active and retain pathogenic potential but cannot be detected by standard culture methods. This poses a significant risk to human health, particularly in water systems where pathogens such as

Legionella pneumophila,

Vibrio cholerae, and

P. aeruginosa may persist in this dormant state [

16]. Therefore, disrupting quorum sensing can control both biofilm formation and VBNC cell resuscitation.

Effective disruption of QS requires a reduction in bacterial population density. Lytic phage pretreatment lowers bacterial concentrations below the critical threshold necessary for QS signal accumulation, thereby indirectly suppressing QS-regulated pathways associated with biofilm initiation, maturation, and virulence factor expression [

17,

18]. Accordingly, lytic bacteriophages were employed in this study as a strategic pretreatment approach. Bacteriophages are viruses that specifically infect bacteria and archaea [

19]. Recent applications include phage therapy for multidrug-resistant bacteria [

20], biosensors for detecting bacterial viability [

21], and biological control in water treatment [

22].

As obligate intracellular parasites, phages cannot replicate or persist in the environment without their specific hosts. This property has enabled their use, for example, as biosensors to detect bacterial viability and activity post-treatment, even when bacteria enter the viable but non-culturable state [

23]. Additionally, these viruses have been used to control the density of pathogenic bacteria [

24]. In biological wastewater treatment, phages have been shown to influence bacterial community structure and, subsequently, improve process efficiency and effluent quality [

25]. The use of phages may provide more efficient alternatives with reduced toxicity and improved water reuse potential [

26,

27]. Nevertheless, research in this area remains less extensive than that on conventional physical and chemical processes.

Biofilms are heterogeneous structures comprising bacterial populations in various physiological states, including viable cultivable bacteria (VCB), VBNC cells, and dead or lysed cells. Notably, several studies have shown that a subpopulation of dead bacteria undergoes lysis, releasing extracellular DNA (eDNA), which plays a crucial role in intercellular cohesion and the structural stability of the biofilm matrix [

28]. Therefore, even after partial bacterial inactivation, remaining viable cells can exploit eDNA from lysed cells to contribute to biofilm persistence or regeneration.

To counter biofilm persistence and enhance photocatalytic efficiency, this study combined TiO

2 with TEO from

Thymus vulgaris as a bio-inspired photosensitizer. TEO contains bioactive phenolic compounds (primarily thymol and carvacrol) with potent antibacterial and antibiofilm properties [

29]. These compounds disrupt bacterial membranes, inhibit exopolysaccharide production, interfere with quorum sensing, and destabilize eDNA, a key component of the biofilm matrix [

30]. Several studies have demonstrated that thymol disrupts molecular bridges formed by eDNA, thereby weakening biofilm cohesion [

31]. Additionally, thyme essential oil has been shown to inhibit early biofilm formation and interfere with bacterial communication systems essential for biofilm maturation [

32]. Thymol also significantly reduces resistant strains such as methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus by downregulating genes involved in controlled cell lysis, such as cidA, while also reducing production of polysaccharide intercellular adhesin, another key extracellular matrix component [

33].

The TiO2–TEO combination thus provides a dual-action mechanism: ROS generation from TiO2 under UV/visible light inactivates bacteria, while TEO disrupts membranes, prevents adhesion, inhibits biofilm initiation, and destabilizes the eDNA network. This synergistic, nature-inspired approach offers a sustainable alternative to conventional chemical disinfectants.

Several studies have explored the use of natural photosensitizers to extend the visible-light activity of TiO

2 for antibiofilm applications. Notably, TiO

2/red cabbage anthocyanin (RCA) complexes have been shown to reduce early biofilm formation from planktonic bacteria by enhancing photocatalytic efficiency under visible light [

34]. However, the primary objective of the present study goes beyond photosensitization alone. In this present study, a sequential strategy using lytic phage pretreatment with TiO

2–TEO photocatalysis was applied to inhibit biofilm development and, critically, to prevent post-treatment biofilm regeneration.

The novelty of this approach lies in its preventive dimension: phage pretreatment weakens bacterial adhesion and disrupts early biofilm architecture, while subsequent TiO2–TEO photocatalysis promotes not only bacterial inactivation but also the degradation of eDNA and cellular debris released during treatment. The removal of these residual components, known to act as structural and genetic reservoirs for biofilm re-establishment, significantly limits biofilm regrowth after treatment.

Study Objective: This study aimed to inhibit P. aeruginosa biofilm formation by combining: (i) Lytic phage pretreatment to reduce bacterial density and disrupt biofilm integrity; (ii) TiO2 photocatalysis to generate oxidative stress; and (iii) TEO as a bio-inspired photosensitizer to enhance antibacterial activity and degrade eDNA. This integrated bio-photocatalytic approach targets both planktonic and sessile bacterial populations to prevent biofilm initiation and eliminate mature biofilm structures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Catalyst

The photocatalyst used was titanium dioxide TiO2 Degussa P25 (Evonik Industries AG, Essen, Germany), composed of approximately 80% anatase and 20% rutile, with a specific surface area of ~50 m2·g−1 and an average crystallite size of ~30 nm. A 0.1% (w/v) aqueous suspension (1 mg·mL−1) was prepared by dispersing 0.100 g of TiO2 powder in approximately 80 mL of ultrapure water produced by a Milli-Q purification system (Merck Millipore, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), followed by sonication in an ultrasonic bath (40 kHz, 120 W) at 25 ± 2 °C for 15–30 min using intermittent cycles (5 min on/2 min off) to prevent overheating and to ensure homogeneous dispersion through cavitation-induced deagglomeration. The final volume was then adjusted to 100 mL with ultrapure water. The suspension was used immediately after sonication to maximize colloidal stability and minimize particle re-agglomeration; no storage was applied. When sonication was unavailable, vigorous magnetic stirring (≥800 rpm for ≥1 h) was employed as an alternative dispersion method, although with reduced dispersion efficiency. The resulting suspension exhibited a slightly milky appearance, indicating uniform TiO2 dispersion.

2.2. Preparation of Bacterial Strains and Growth Media

P. aeruginosa ATCC 4114 was maintained on Nutrient Agar (NA; Biokar Diagnostics, Beauvais, France) and stored at 4 °C. For each experiment, an isolated colony was used to inoculate Nutrient Broth (NB; Biokar Diagnostics, Beauvais, France) medium, and cultures were grown overnight at 37 °C under aerobic conditions with constant shaking. Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring optical density at 600 nm (OD600). Cells were harvested during the stationary phase. Bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation at 4000× g for 10 min and washed twice with sterile demineralized water. Finally, the pellet was re-suspended in physiological saline solution (0.85% NaCl; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The final cell density was adjusted to approximately 106 CFU/mL.

2.3. Isolation of Phages and Study of Their Susceptibility to the Target Bacteria

The phage isolated in this study was a Siphovirus, a tailed phage belonging to the order

Caudovirales, which specifically infects

Pseudomonas host strains and exhibits lytic activity. This phage has also been used in a previous study by Ben Said et al. (2009) [

35]. In the present work, phages were isolated from municipal wastewater collected in Soliman, Tunisia, following the method described by the same authors. Briefly, 100 mL of wastewater was mixed with 100 mL of double-strength Luria–Bertani (LB) broth (Biokar Diagnostics, Beauvais, France) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h with shaking at 150 rpm. The cultures were then centrifuged at 8000×

g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants were filtered through 0.22 µm pore-size membrane filters (Biokar Diagnostics, Beauvais, France). The resulting phage lysates were stored at 4 °C in the dark and supplemented with one drop of chloroform until further use.

For the primary isolation of lytic phages, P. aeruginosa was used as the host strain using the agar spot test method. Briefly, the host strain was grown in LB broth, and 100 µL of an overnight culture was mixed with 5 mL of molten soft LB agar (0.6% w/v) maintained at 49 °C, then poured onto LB agar plates. After solidification and drying of the agar surface, 5 µL of phage lysate was spotted onto the plates and incubated to detect the formation of clear or turbid lysis zones.

Individual clear plaques were picked using a sterile pipette tip and suspended in LB broth for further purification. Alternatively, soft agar containing phage plaques was overlaid with 5 mL of LB broth and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with gentle agitation to facilitate phage release. Phage particles were subsequently separated from agar and host cell debris by centrifugation at 13,000× g for 15 min at 4 °C. Phage titers were determined, and the resulting preparations were used for host-range determination using the agar spot test described above.

2.4. Coupling TiO2 with Thyme Essential Oil

100 g of dried plant material (leaves of Thymus vulgaris) was subjected to hydrodistillation in a Clevenger-type apparatus for 3 h. The obtained essential oil was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and stored in amber vials at 4 °C until further analysis.

An aqueous suspension of TiO2 P25 was prepared at a concentration of 0.1 g/L by dispersing 0.010 g of nanopowder in 100 mL of deionized water under magnetic stirring (800 rpm, 15 min). To this suspension, TEO was added to achieve final concentrations of 0.05%, 0.075%, 0.1%, and 0.2% (v/v). To facilitate homogeneous dispersion, 0.5 mL of ethanol (≥99.8%, HPLC grade) was used as a co-solvent per 100 mL suspension. The mixtures were stirred in the dark at 500 rpm for 30 min to promote adsorption of TEO bioactive compounds onto the TiO2 surface. The resulting TiO2–TEO hybrids were used immediately in photocatalytic assays as described below.

The interaction between TiO2 P25 and TEO was evaluated using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Prior to analysis, 3 mL aliquots of each TiO2-TEO hybrid suspension (0.1 g/L TiO2 with 0.05–0.2% v/v TEO) were diluted 1:10 in deionized water to avoid signal saturation. Measurements were performed in 1 cm path-length quartz cuvettes, using a blank consisting of 0.5% (v/v) ethanol in deionized water.

2.5. Photocatalytic Treatment

An aqueous suspension of titanium dioxide (TiO2; anatase, P25) was prepared at a concentration of 0.1 g/L by dispersing the powder in deionized water under vigorous stirring. Photocatalytic tests were then performed by exposing the suspension to simulated sunlight under constant stirring at room temperature (25 °C). Samples were collected at regular intervals (every 20 min) for subsequent biofilm production assays.

2.6. Monitoring of Biofilm Formation Under Different Conditions

Biofilm formation was quantified according to O’Toole (1998) [

36], with minor modifications. Briefly, an overnight culture of

P. aeruginosa was diluted 1:100 in fresh LB broth, and 200 μL of the bacterial suspension (previously subjected to different treatments) was added to the wells of a sterile 96-well microtiter plate. The plates were incubated for 18 h at 30 °C. Following incubation, wells were gently washed three times with sterile physiological saline (0.85% NaCl) to remove non-adherent cells, and the remaining biofilms were stained with 0.1% (

w/

v) crystal violet (CV). Excess dye was removed by washing, and bound CV was solubilized in 33% acetic acid (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The extent of biofilm formation was quantified by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD

600), and results were compared to untreated controls (medium only). Each condition was tested in triplicate, and experiments were repeated at least three times.

For preformed biofilms, 24 h old biofilms were first established in 96-well plates as described above. Preformed biofilms were gently washed three times with sterile 0.85% (w/v) NaCl solution (physiological saline) to remove non-adherent planktonic cells while preserving the extracellular matrix and sessile population. A volume of 200 μL of specific lytic phage suspension (106 PFU/well) was then added to each well. The plates were incubated at 30 °C for the specified duration. Biofilms were quantified before and after treatment using the CV staining method. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

The percentage of biofilm inhibition was calculated according to the following formula [

37]: % Biofilm inhibition = 100 − (OD

600 treated/OD

600 control) × 100.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test for pairwise comparisons or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Monitoring Biofilm Inhibition in Different Cell Forms Using Photocatalytic Treatment

The first part of this study aimed to evaluate the impact of photocatalytic treatment on biofilm formation by

P. aeruginosa. Specifically, the bacteria were treated in both planktonic and sessile forms (

Figure 1) to assess the dual effectiveness of the photocatalytic process: first, in inhibiting biofilm initiation by free planktonic cells, and second, in disrupting pre-established structurally resistant biofilm. This approach allowed us to investigate the potential of the treatment to prevent biofilm development and to weaken and destabilize mature biofilm structure.

The kinetics of biofilm inhibition under photocatalytic treatment with TiO

2 nanoparticles were modeled using a modified first-order exponential decay model:

With: Mb, the total biomass of the biofilm for the control test before photocatalytic treatment; Mt, the residual biomass of the biofilm at time t after treatment; A, the fraction of bacteria in planktonic cell state which has lost the ability to adhere to the inert support after treatment (in planktonic form) or the biofilm weakness rate (in sessile form); k, bio-film inactivation rate; C, photocatalyst concentration; t, irradiation time (min); and n, the threshold level (n is equal to 1 for the first-order model).

Then, the biofilm growth constants (A, k) were determined (

Table 1). Results are summarized in the table below for planktonic (suspended cells) and sessile (biofilm) forms.

Photocatalytic treatment significantly reduced the density of metabolically active bacteria (Ma) capable of adhering to surfaces and initiating biofilm formation (

Figure 1), while simultaneously increasing the proportion of defective or inactivated cells (Md). This shift resulted in 59% biofilm inhibition (

Table 1). The observed inhibition is attributed to photocatalysis-mediated reduction of active bacterial density, which disrupts quorum sensing (QS), the intercellular communication system regulating virulence factor expression and biofilm development [

38]. By lowering the Ma fraction below the quorum threshold, photocatalysis suppresses the coordinated bacterial behaviors required for biofilm initiation.

The active bacterial fraction (Ma) comprises three subpopulations: (i) viable and cultivable bacteria (VCB), (ii) viable but non-cultivable (VBNC) cells undetectable by conventional culture-based methods, and (iii) viable but not yet resuscitated bacteria following treatment. In contrast, the defective fraction (Md) includes dead cells and severely injured bacteria unable to recover or resuscitate [

39,

40]. The VBNC state represents a survival strategy under adverse conditions, allowing cells to maintain metabolic activity despite loss of culturability. Guo et al. (2023) [

41] demonstrated that stress-induced VBNC populations form thinner but more resilient biofilms with altered extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) composition, enabling rapid resuscitation and recolonization once favorable conditions are restored.

Monitoring biofilm weakening in sessile

P. aeruginosa cells revealed 53% inhibition under photocatalytic treatment (

Figure 1,

Table 1), indicating comparable susceptibility in planktonic and sessile states. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated damage including membrane peroxidation, DNA lesions, and protein denaturation effectively penetrated the EPS matrix, overcoming diffusion limitations typically associated with biofilm resistance. These results highlight photocatalysis as a physiology-independent disinfection strategy.

Despite substantial inhibition (53–59%), residual VBNC cells and eDNA released from lysed bacterial populations contribute to biofilm persistence and regrowth. eDNA plays a key role in cell–cell adhesion and biofilm structural integrity [

42], enabling remaining active bacteria to maintain biofilm architecture and resume growth through QS-mediated resuscitation. Consequently, complete biofilm eradication requires strategies that prevent VBNC survival or effectively target resuscitated cells and structural biofilm components.

To address these limitations, a dual synergistic pretreatment strategy was implemented: (i) lytic bacteriophages to reduce the active bacterial population (Ma) and (ii) TiO2 combined with 0.05% thyme essential oil (TEO) as a bio-inspired photosensitizer to enhance ROS generation and extend photocatalytic activity into the visible spectrum. This integrated approach suppresses residual biofilm formation by surviving active and VBNC populations while simultaneously promoting eDNA degradation, thereby disrupting the structural scaffold essential for biofilm resilience and regrowth.

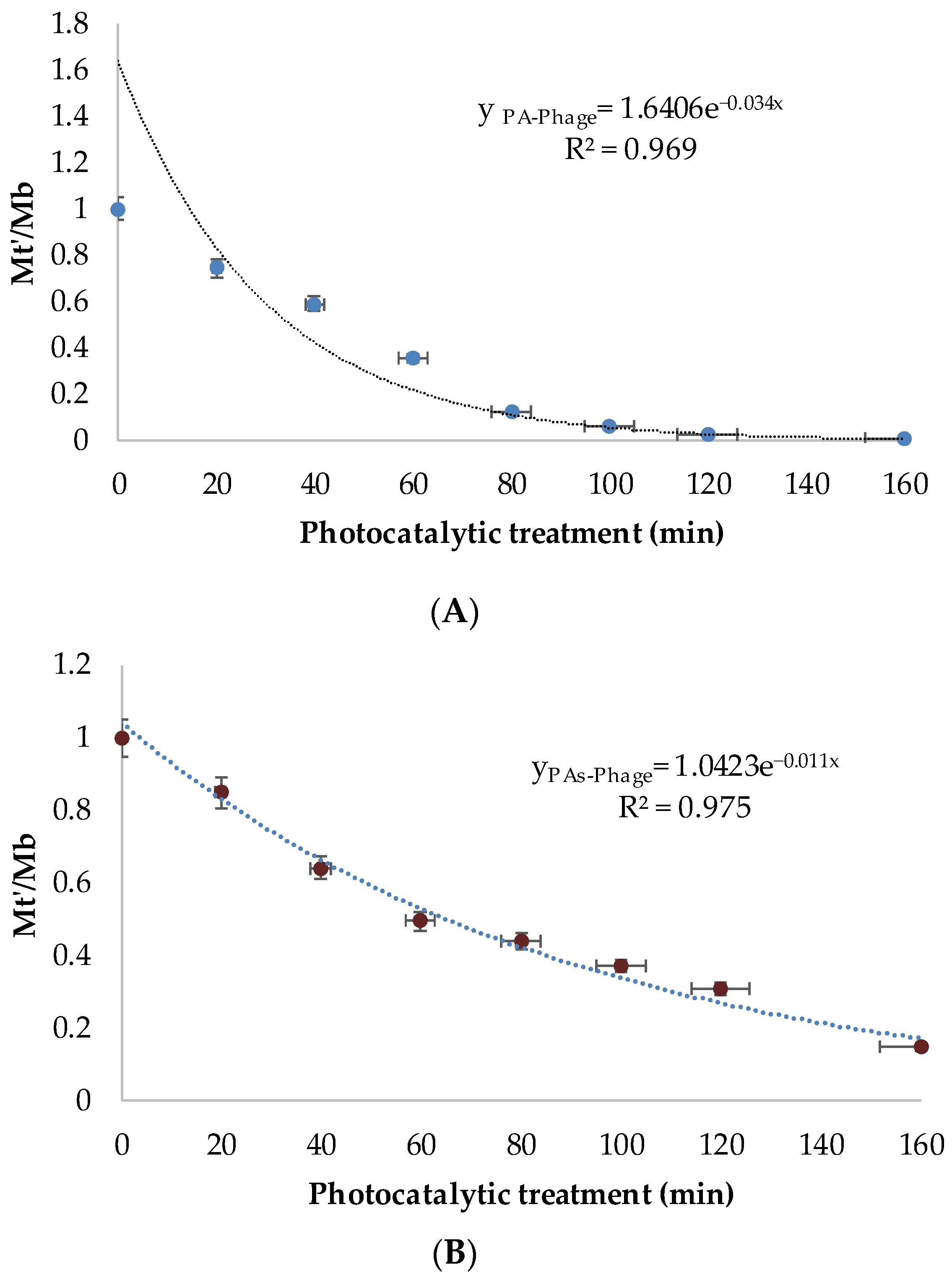

3.2. Application of Specific Lytic Phage Pretreatment to Prevent and Reduce Biofilm Formation

For planktonic cells, lytic phage pretreatment markedly enhanced photocatalytic efficacy against

P. aeruginosa. The biofilm inactivation rate constant increased from k = 0.006 to 0.034 min

−1, while the fraction of bacteria losing adhesion capacity (A) rose from 1.055 to 1.64 (

Table 1 and

Table 2). This resulted in 99.6% inhibition of biofilm formation (

Table 2), corresponding to a 1.7-fold improvement compared to photocatalysis alone (

Figure 2). These results confirm the strong effectiveness of phage pretreatment in suppressing biofilm initiation by planktonic cells.

In sessile biofilms, combined phage pretreatment and photocatalysis also significantly improved biofilm control. Overall inhibition increased from 52.73% to 89.06% (

Table 1 and

Table 2), accompanied by a doubling of the inactivation rate constant (k from 0.005 to 0.011 min

−1). The modest increase in parameter A (from 0.936 to 1.04) despite higher inhibition likely reflects the accumulation of dead bacterial debris following phage-induced lysis. As lysed cells were not removed prior to biomass quantification, they may have contributed to the measured residual biomass, affecting the apparent biofilm weakness rate [

43]. Nevertheless, the strong increase in k confirms a clear net benefit of phage pretreatment.

This enhancement arises from multiple complementary phage-mediated mechanisms. Many lytic phages encode polysaccharide depolymerases that degrade the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix, facilitating penetration into deeper biofilm layers [

44]. Other phages produce quorum-quenching lactonases capable of hydrolyzing acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs), thereby disrupting quorum-sensing (QS) signaling [

45]. Importantly, phages remain effective against viable but non-cultivable (VBNC) cells following disinfection, enabling lysis of cultivable, VBNC, and resuscitating bacterial populations [

46].

By reducing bacterial density below QS thresholds, phage pretreatment limits the ability of surviving bacteria, including VBNC cells, to initiate or sustain biofilm regrowth, thereby overcoming a key limitation of standalone photocatalysis. However, the accumulation of phage-induced lysed cells (not removed from samples) can, in some contexts, promote more active and resilient biofilms with increased cultivability, metabolic activity, ATP content, and density [

47]. In our case, the substantial rise in k and overall inhibition (89.06%) demonstrates the dominant positive effect of pretreatment. Disinfection strategies must therefore account for dead cell contributions to biofilm resilience.

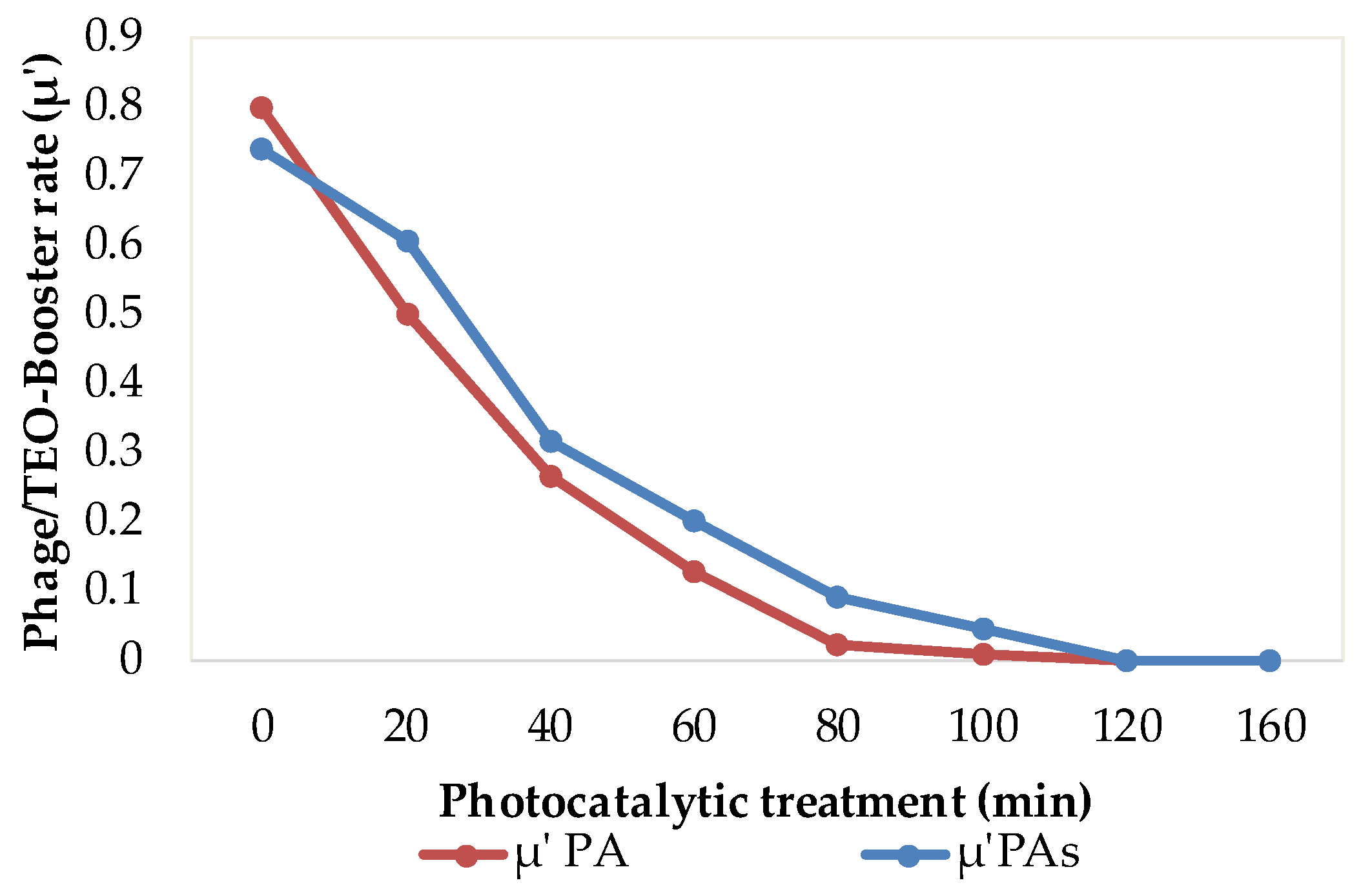

To further highlight the impact of the phage pretreatment, an additional parameter was evaluated, the phage booster rate (µ), which was calculated as follows:

where μ is the phage booster rate; Mt represents the total biofilm biomass after photocatalytic treatment alone, and Mt′ corresponds to the total biofilm biomass following pre-treatment with phage and the subsequent photocatalytic treatment.

Analysis of μ indicated that phage activity persisted throughout the photocatalytic disinfection process and remained closely correlated with host cell survival. Despite the sensitivity of bacteria to reactive oxygen species (ROS), phage persistence is likely enabled by a pseudo-lysogenic state, in which phage nucleic acid remains latent within the host cell, preserving infectivity under oxidative stress conditions [

48]. This latent state contributes to the long-term survival and activity of phages during photocatalytic treatment.

Under sessile conditions, the booster effect developed more slowly than in planktonic systems but exhibited greater stability over time (

Figure 3). This behavior can be attributed to the protective role of the biofilm matrix, which facilitates phage penetration into deeper biofilm layers while shielding viral particles from photocatalytic inactivation.

The incorporation of phages within the biofilm structure likely protects them against ROS exposure, enabling sustained replication and synchronized lysis in concert with photocatalytic damage. As a result, prolonged and coordinated antibiofilm activity is achieved through the combined action of phage-mediated lysis and photocatalysis.

Following phage treatment, bacterial lysis releases cellular debris and extracellular DNA (eDNA), which may serve as a structural scaffold for biofilm reformation. Consequently, photocatalysis was applied as a complementary step to degrade residual organic matter, including eDNA and dead cell fragments, thereby eliminating substrates for bacterial adhesion and reducing the likelihood of biofilm reestablishment. To further enhance photocatalytic efficiency, TEO was incorporated as a bio-inspired photosensitizer, acting synergistically with TiO2 to improve photocatalytic degradation and reinforce overall antibiofilm activity.

The multi-step strategy thus eliminates adhesion substrates, reinforces matrix disruption, and delivers a resilient, long-lasting inhibition of biofilm formation and maintenance, making it a promising approach for large-scale water treatment applications.

3.3. Combination of TiO2 with Thyme Essential Oil for Enhanced Photocatalysis

To enhance photocatalytic treatment and eliminate residual post-treated bacteria capable of initiating biofilm formation, TEO was combined with TiO

2 nanoparticles at different concentrations (0.05%, 0.075%, 0.1%, and 0.2%

v/

v). Based on preliminary screening (

Figure 4), 0.05% TEO was selected as the optimal concentration for subsequent experiments, as it provided high antibiofilm efficiency at minimal dosage, ensuring both effectiveness and cost-efficiency for potential large-scale applications.

UV–Vis spectroscopy (

Figure 4) confirmed the strong absorption of pure TiO

2 below 400 nm, attributed to its wide bandgap (~3.2 eV) [

1,

2,

3]. Additional absorption peaks in the 270–285 nm range were observed after TEO incorporation, corresponding to phenolic compounds, primarily thymol and carvacrol [

49]. The TiO

2–TEO composite exhibited a clear red shift of the absorption edge, extending into the visible region in a dose-dependent manner [

50]. This behavior is attributed to surface adsorption of phenolic compounds onto TiO

2 and possible ligand-to-metal charge transfer interactions, which effectively enhance light harvesting and photosensitivity under visible irradiation [

51]. Such modifications are consistent with previous studies reporting improved photocatalytic performance of TiO

2 functionalized with plant-derived photosensitizers.

Beyond optical enhancement, the incorporation of TEO provides complementary antibiofilm mechanisms. Thymol and carvacrol destabilize bacterial membranes, interfere with quorum-sensing pathways, and potentiate oxidative stress. This synergy between TiO2-generated reactive oxygen species (ROS) and TEO bioactivity enhances antibacterial efficacy, inhibits biofilm initiation, and promotes destabilization of extracellular DNA (eDNA), a critical structural component of mature biofilms.

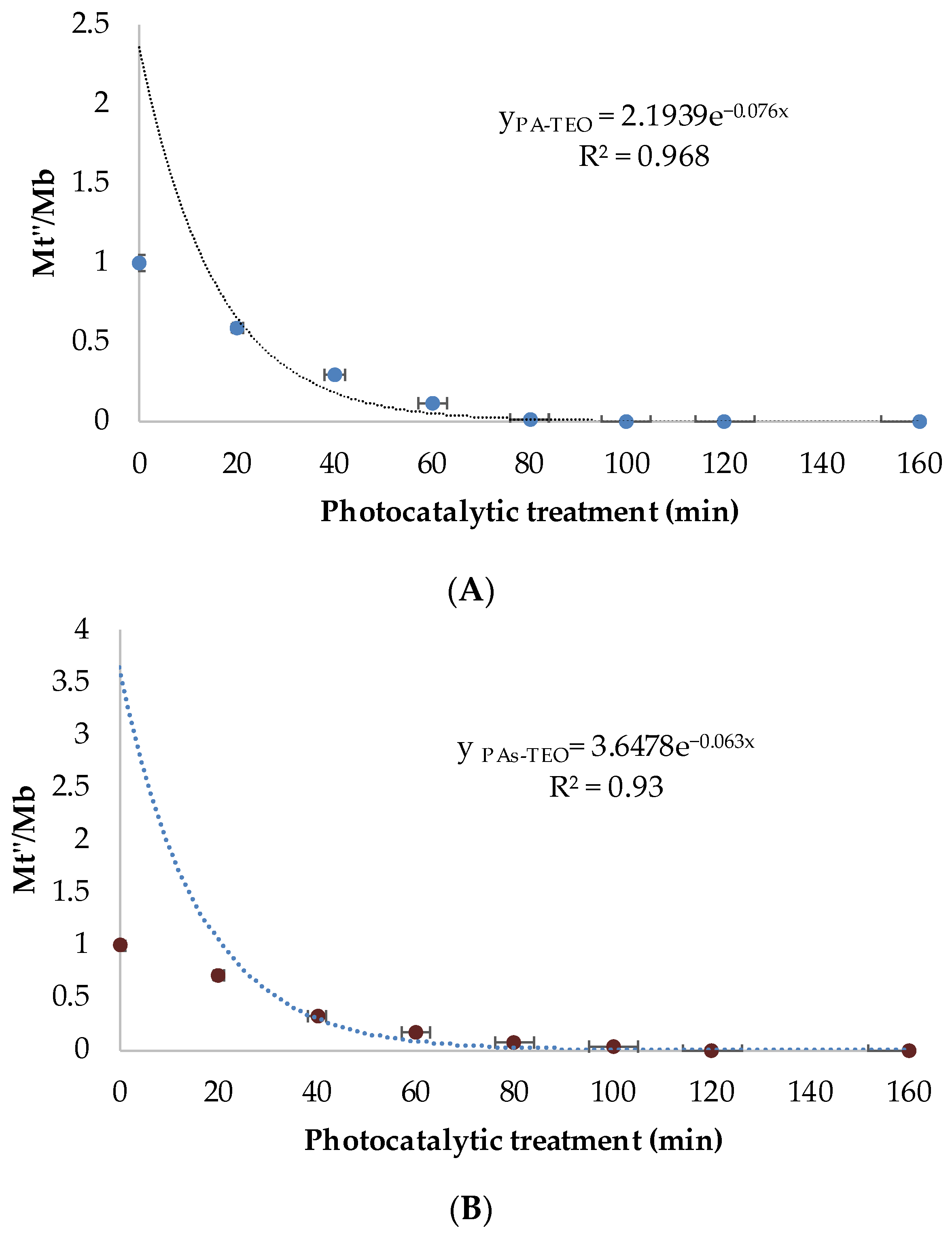

The monitoring of biofilm formation/destabilization after the last optimization of photocatalytic treatment shows an increase in kinetic parameters (k, A). Combined phage pretreatment and TiO

2–TEO (0.05%) photocatalysis achieved 99.99% biofilm inhibition for both planktonic and sessile cells (

Figure 5,

Table 3). This represents a substantial improvement compared to photocatalysis alone (59%) or phage–photocatalysis (99.6% for planktonic, 89% for sessile). Kinetic parameters (A, k) increased significantly, reflecting enhanced biofilm inactivation efficiency (

Figure 5;

Table 2). These results highlight the potential of natural-based solutions to enhance the performance of conventional water treatment methods and to achieve more effective control of biofilm formation and persistence.

To quantify the overall synergy of the integrated approach, the phage/TEO booster rate (μ′) was defined as:

where Mt is the biofilm biomass after conventional TiO

2 photocatalysis alone, and Mt″ is the biomass after lytic phage pretreatment followed by TiO

2–TEO (0.05%) photocatalysis complex.

The (μ′) quantifies the synergistic reduction in biofilm biomass achieved by integrating phage pretreatment with TiO

2–TEO photocatalysis relative to photocatalysis alone (

Figure 6).

As a natural photosensitizer, TEO enhances the elimination of residual metabolically active bacteria capable of initiating biofilm formation. Beyond its photosensitizing role, TEO contributes to the degradation and removal of cellular debris released during bacterial inactivation, thereby limiting the availability of structural and biochemical components that favor biofilm reconstitution. As a result, the combined treatment significantly increases the kinetic parameters (k and A) and achieves up to 99.99% biofilm inhibition for both planktonic and sessile cells, demonstrating the sustained and preventive effectiveness of this bio-inspired strategy against biofilm redevelopment. These findings highlight the strong potential of natural, bio-based additives to enhance conventional water treatment processes. When applied following photocatalytic disinfection, TEO may exert persistent anti-biofilm effects by modifying surface hydrophobicity, disrupting bacterial adhesion, and interfering with quorum-sensing pathways [

52].

Overall, the phage–TEO–TiO2 integrated approach offers a green, sustainable, and highly effective strategy for both biofilm removal and long-term prevention of regrowth.