Geothermal Reservoir Parameter Identification by Wellbore–Reservoir Integrated Fluid and Heat Transport Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area

3. Methods

3.1. Wellbore–Reservoir Coupled System

3.2. Inverse Modeling

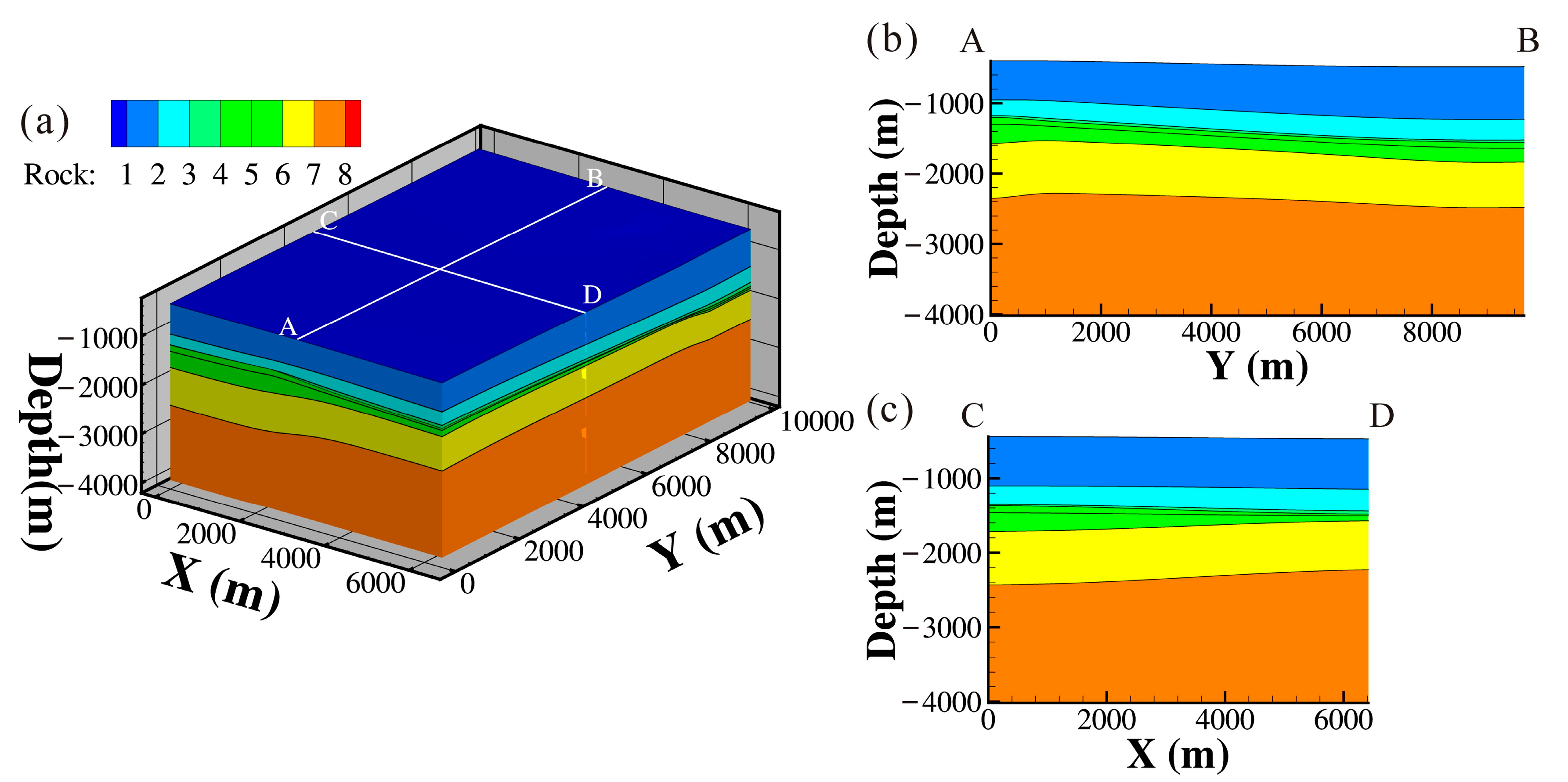

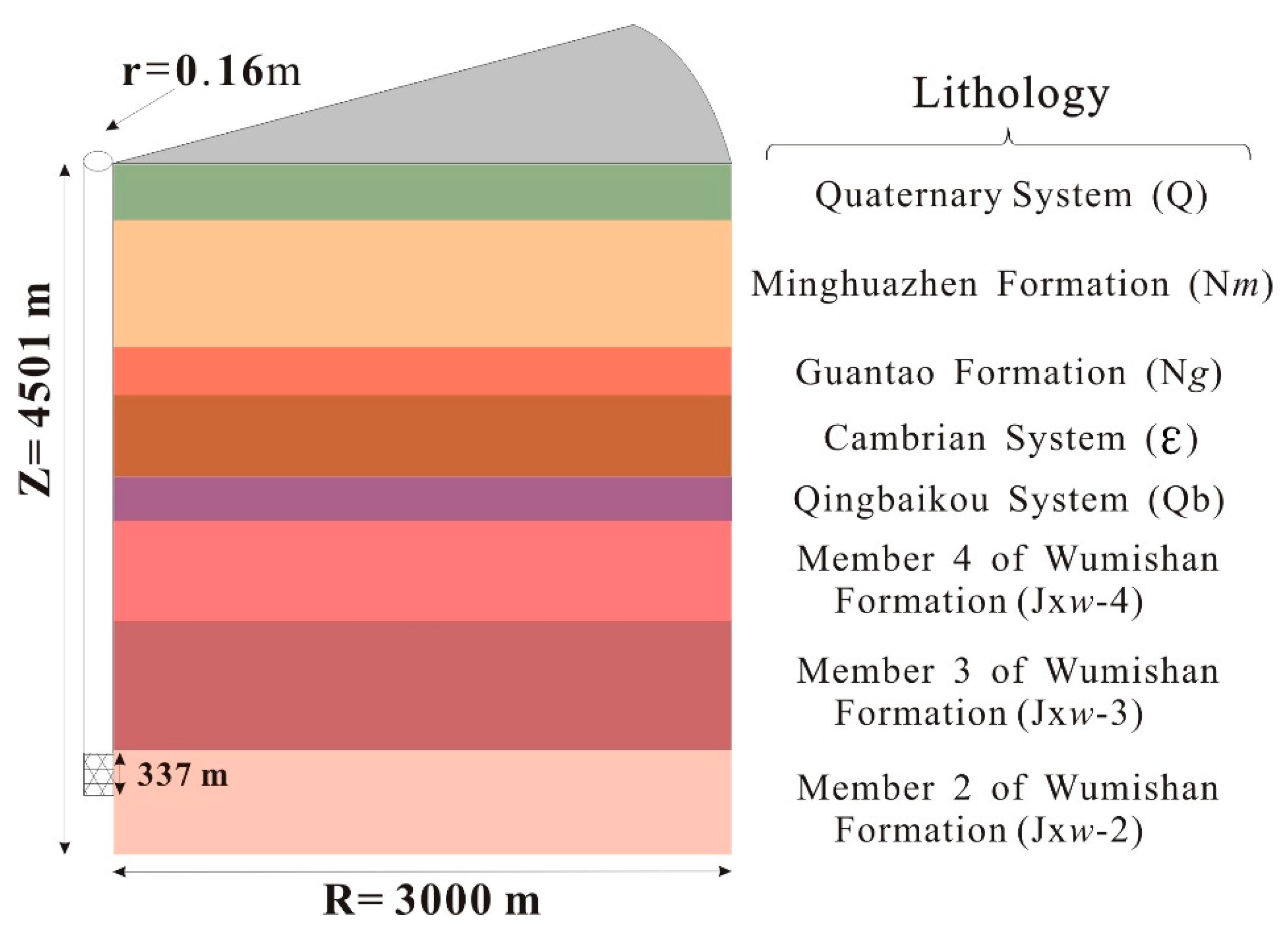

4. Numerical Modeling

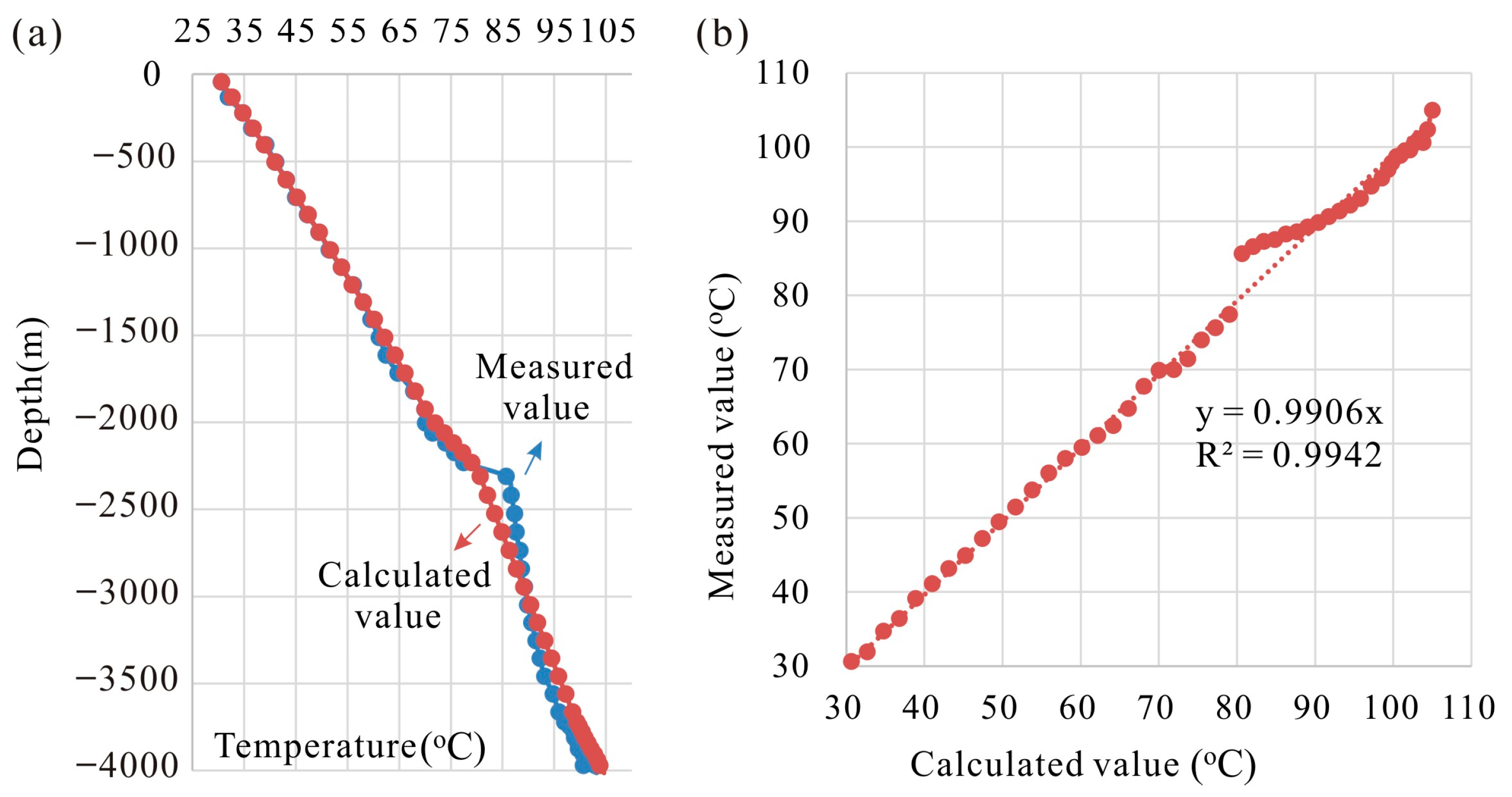

4.1. Geothermal Background

4.2. Natural State Model

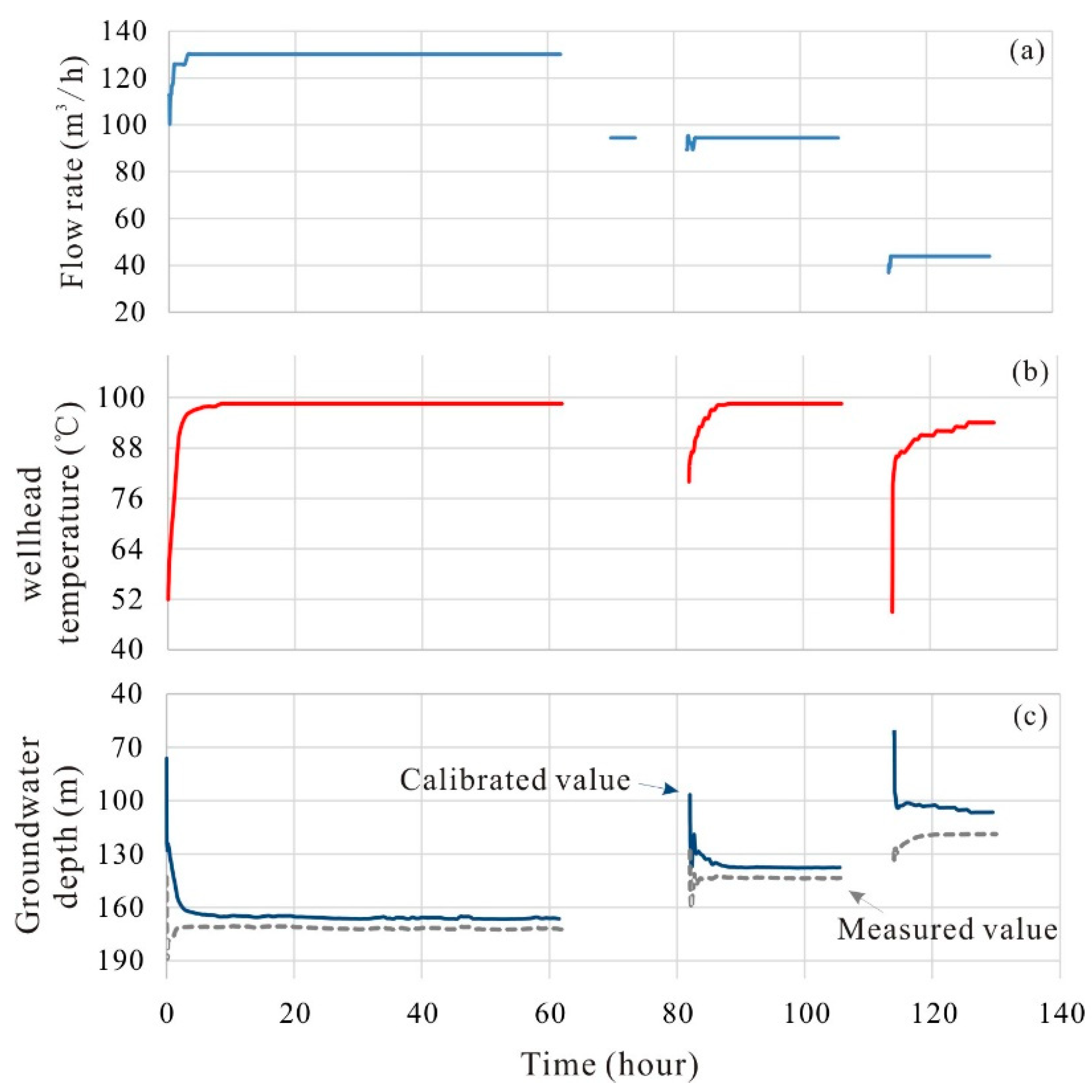

4.3. History Matching of Pumping Test

4.3.1. Field Pumping Test Situation

4.3.2. History Matching of Temperatures and Pressures

4.4. Geothermal Production Strategies and Criteria

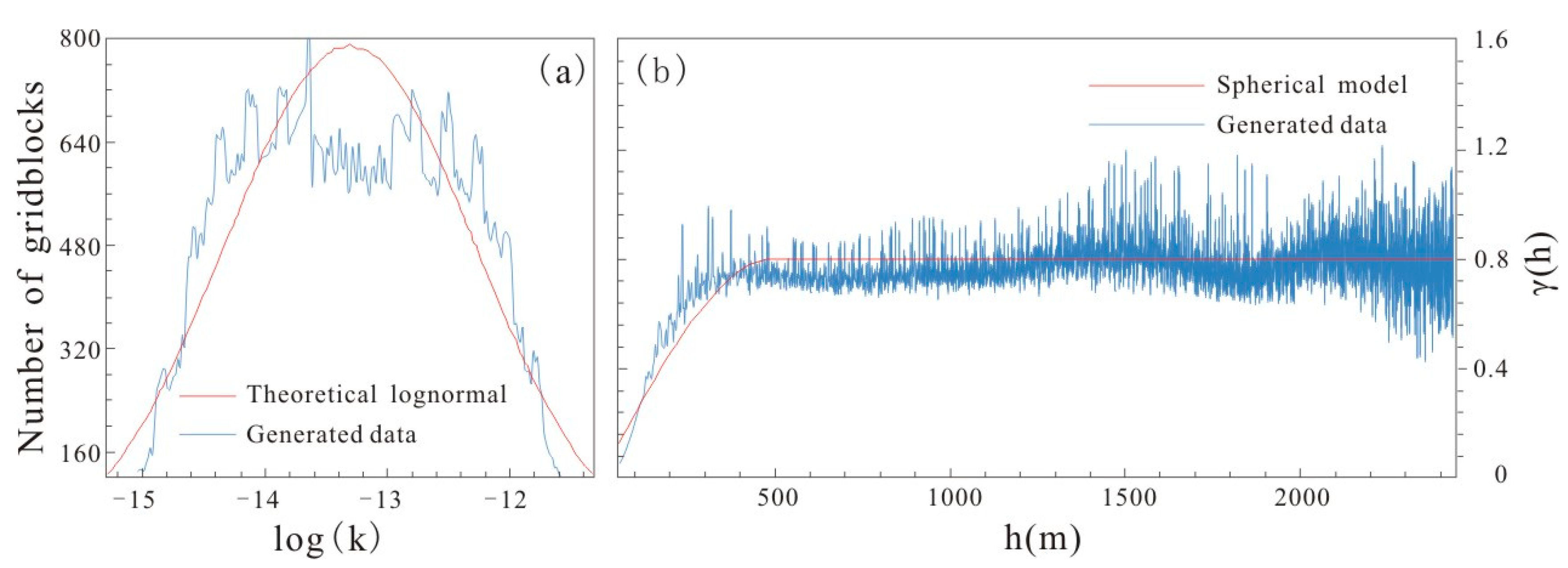

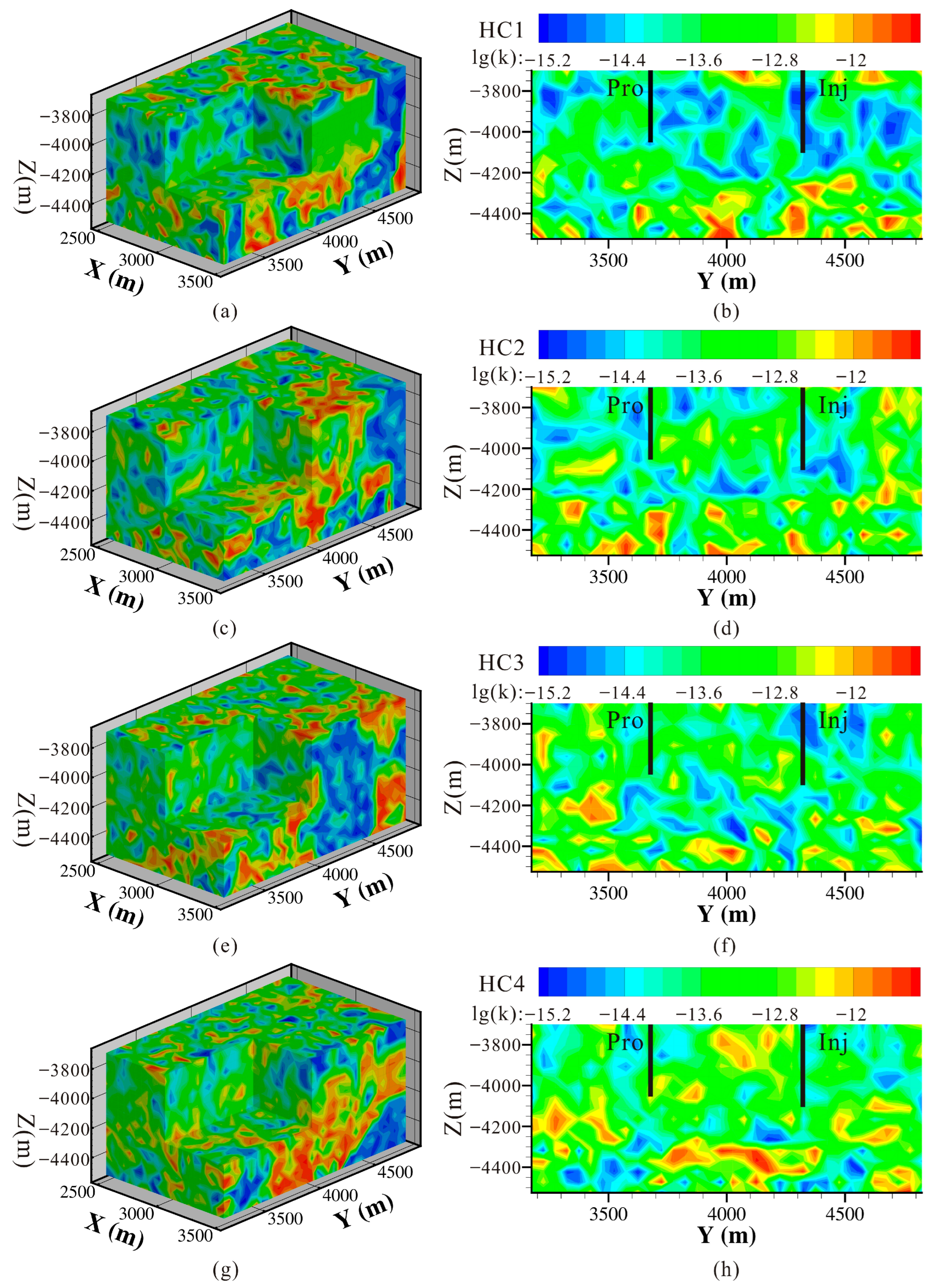

4.5. Heterogeneity Implementation

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Productivity Optimization

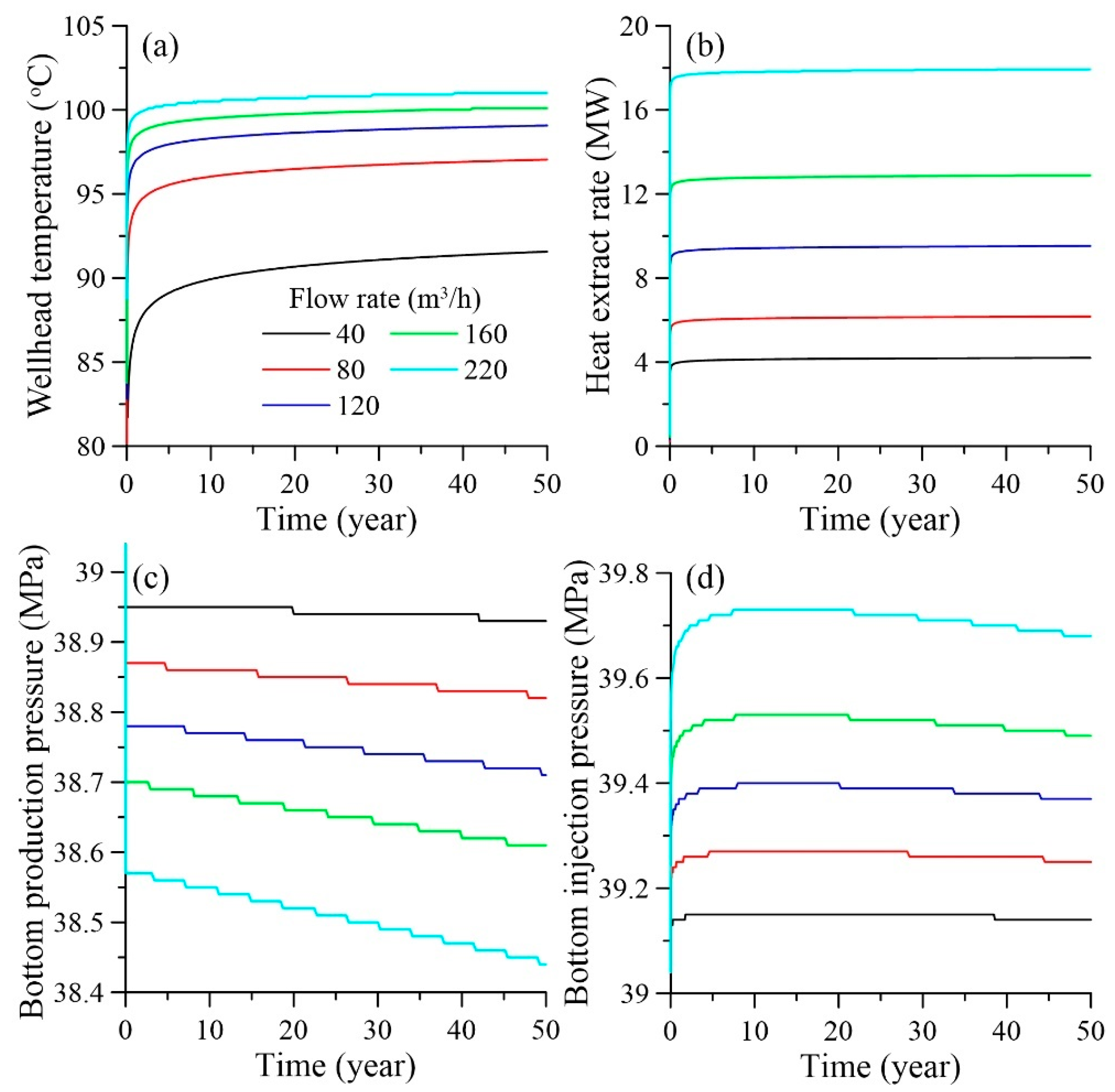

5.1.1. Flow Rate

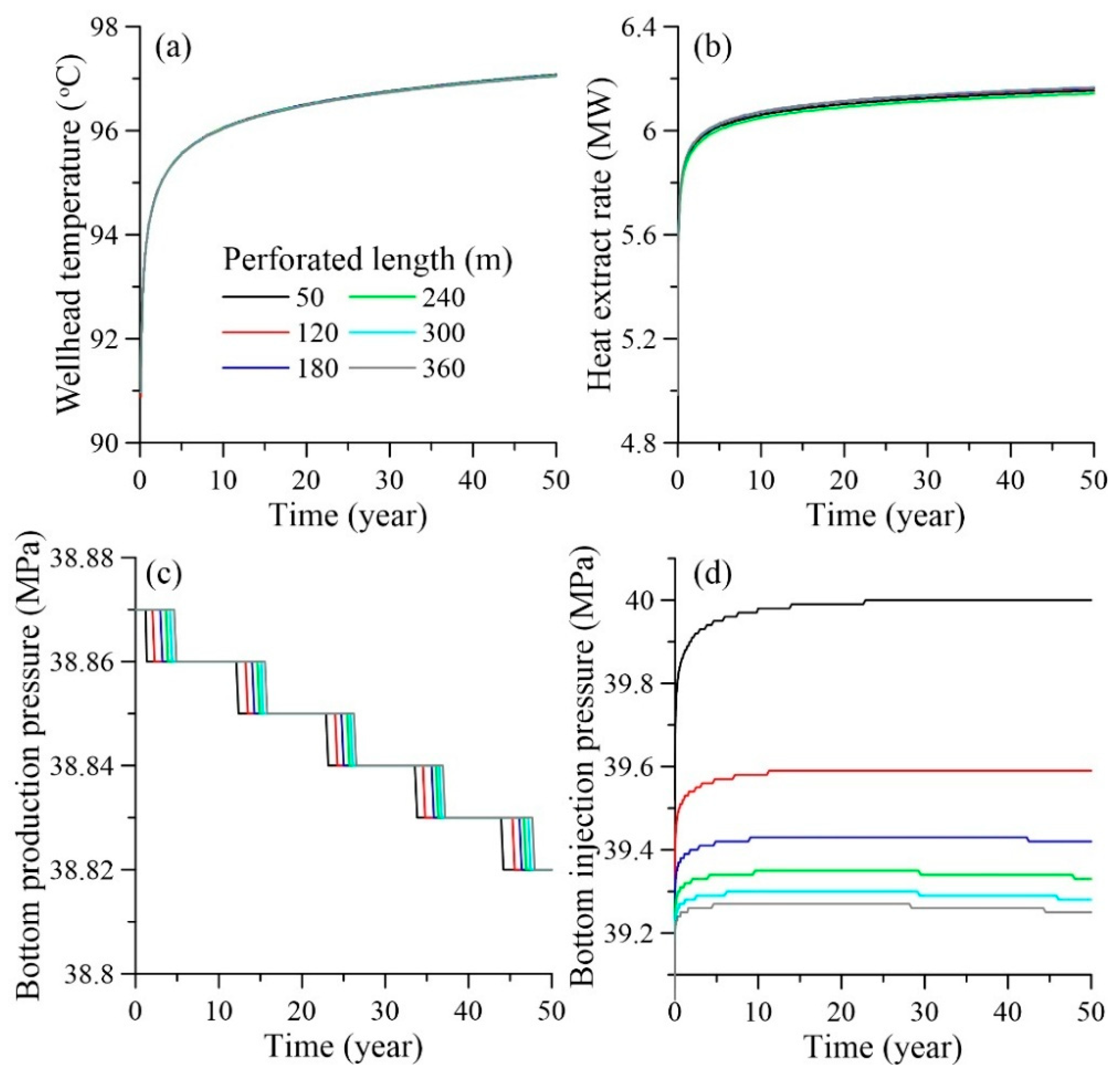

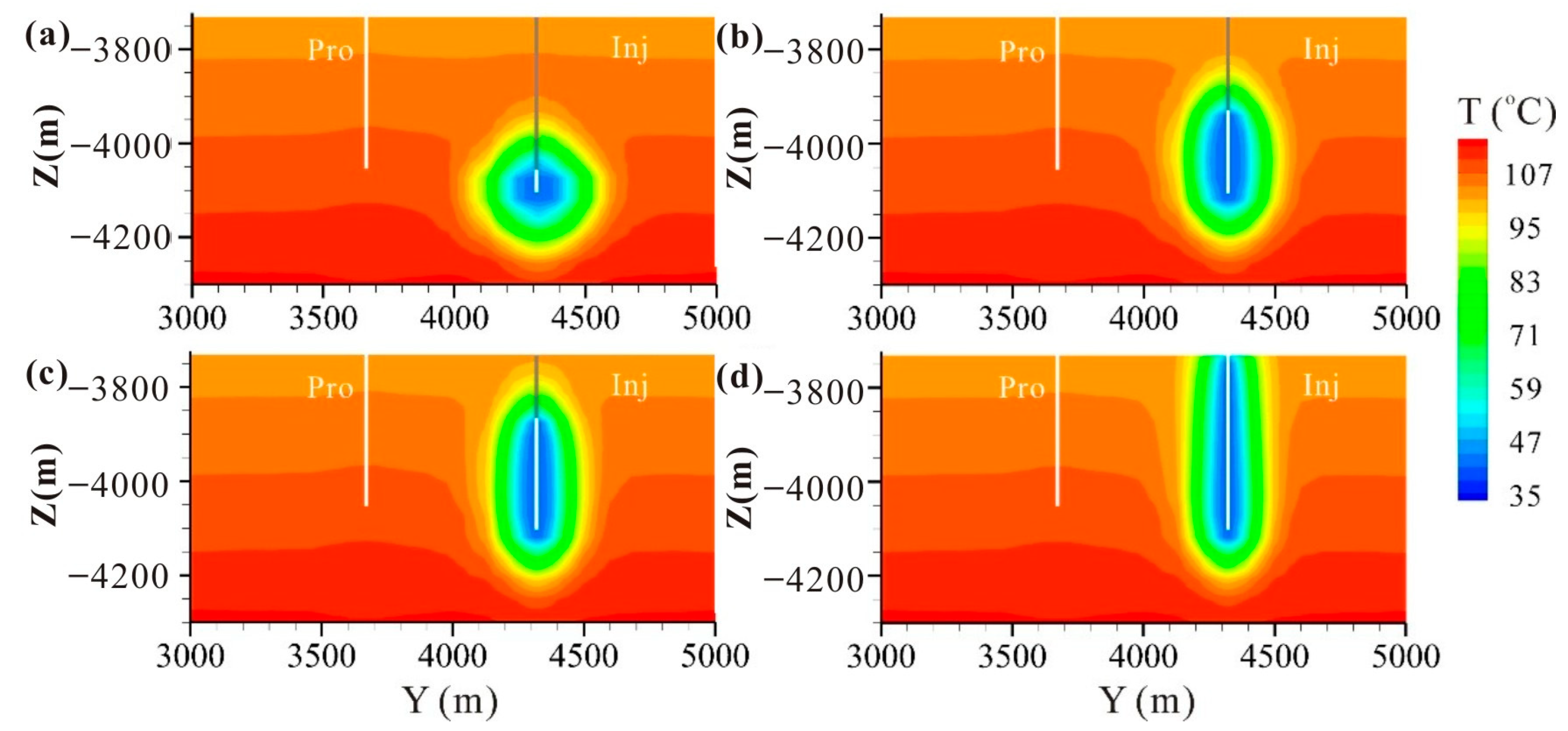

5.1.2. Perforated Length of Injection Well

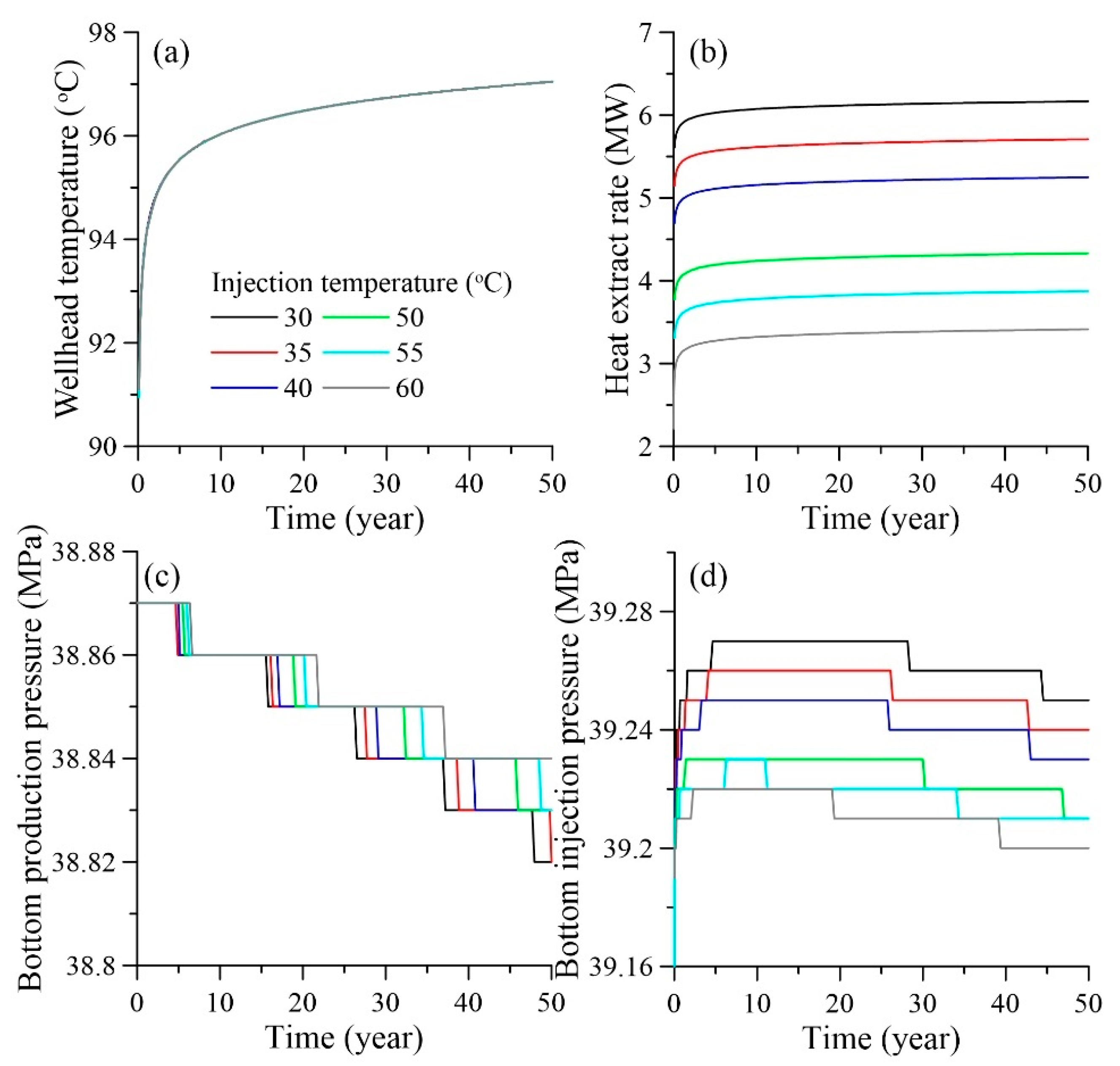

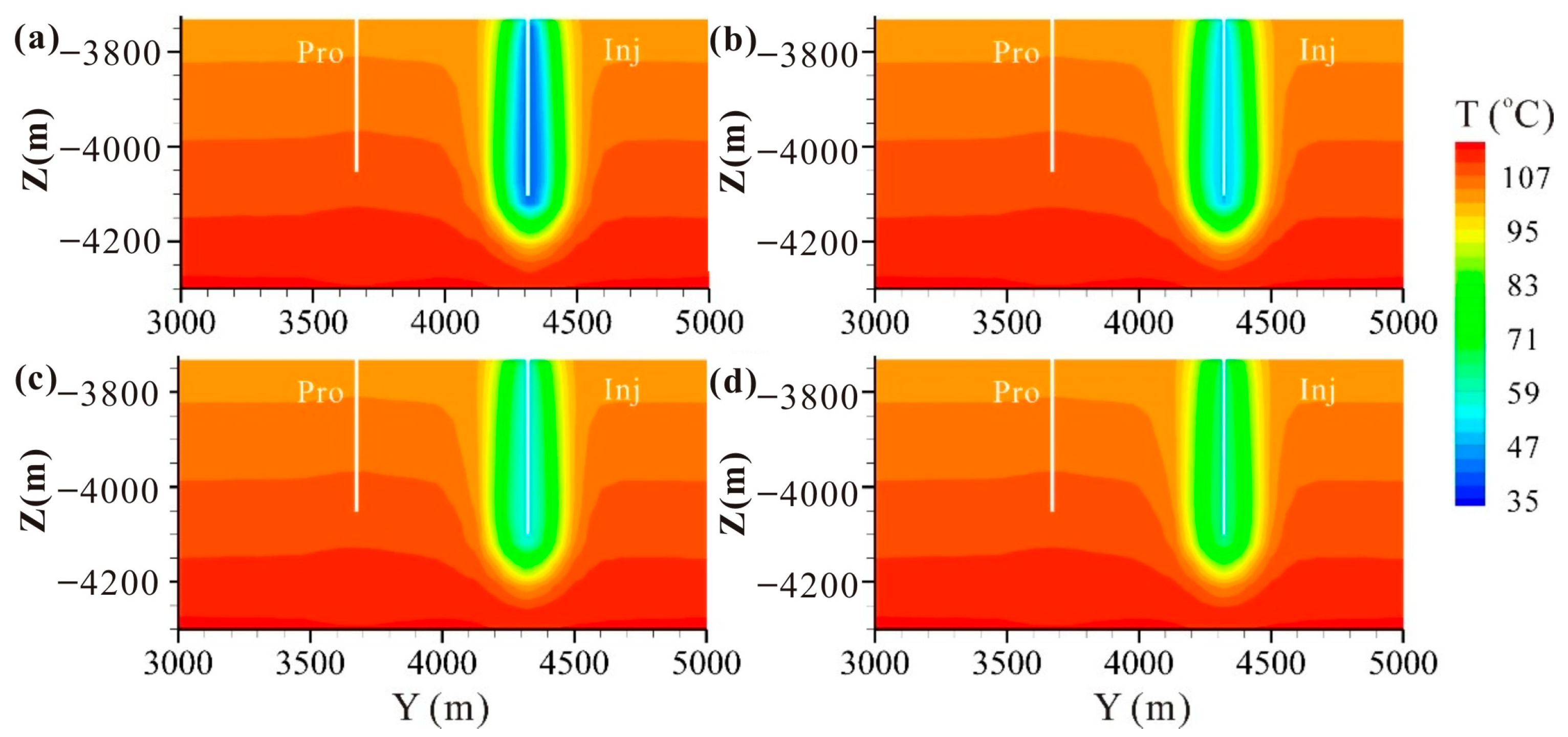

5.1.3. Injection Temperature

5.2. Risk Evaluation of Geothermal Breakthrough

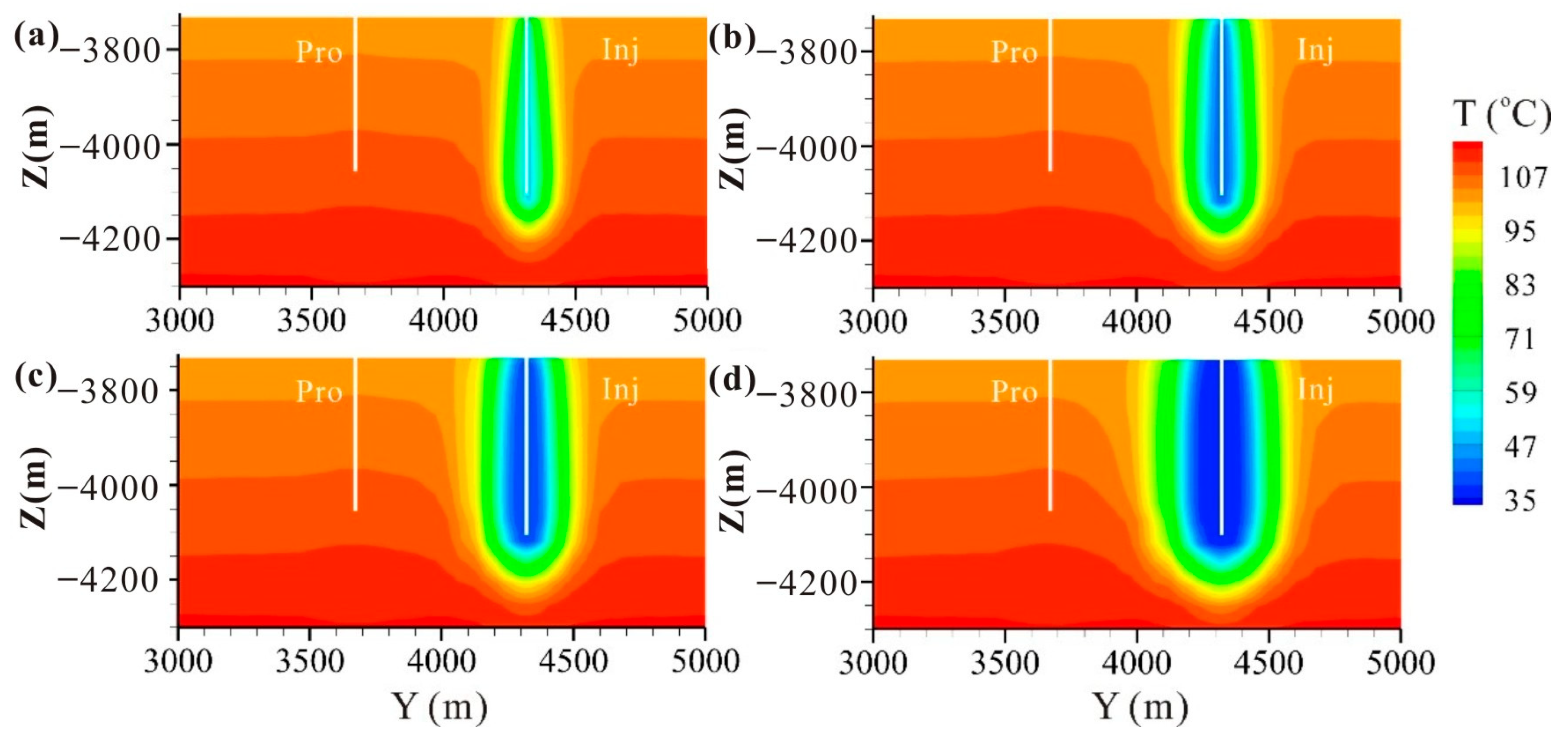

5.2.1. Homogeneous Reservoir

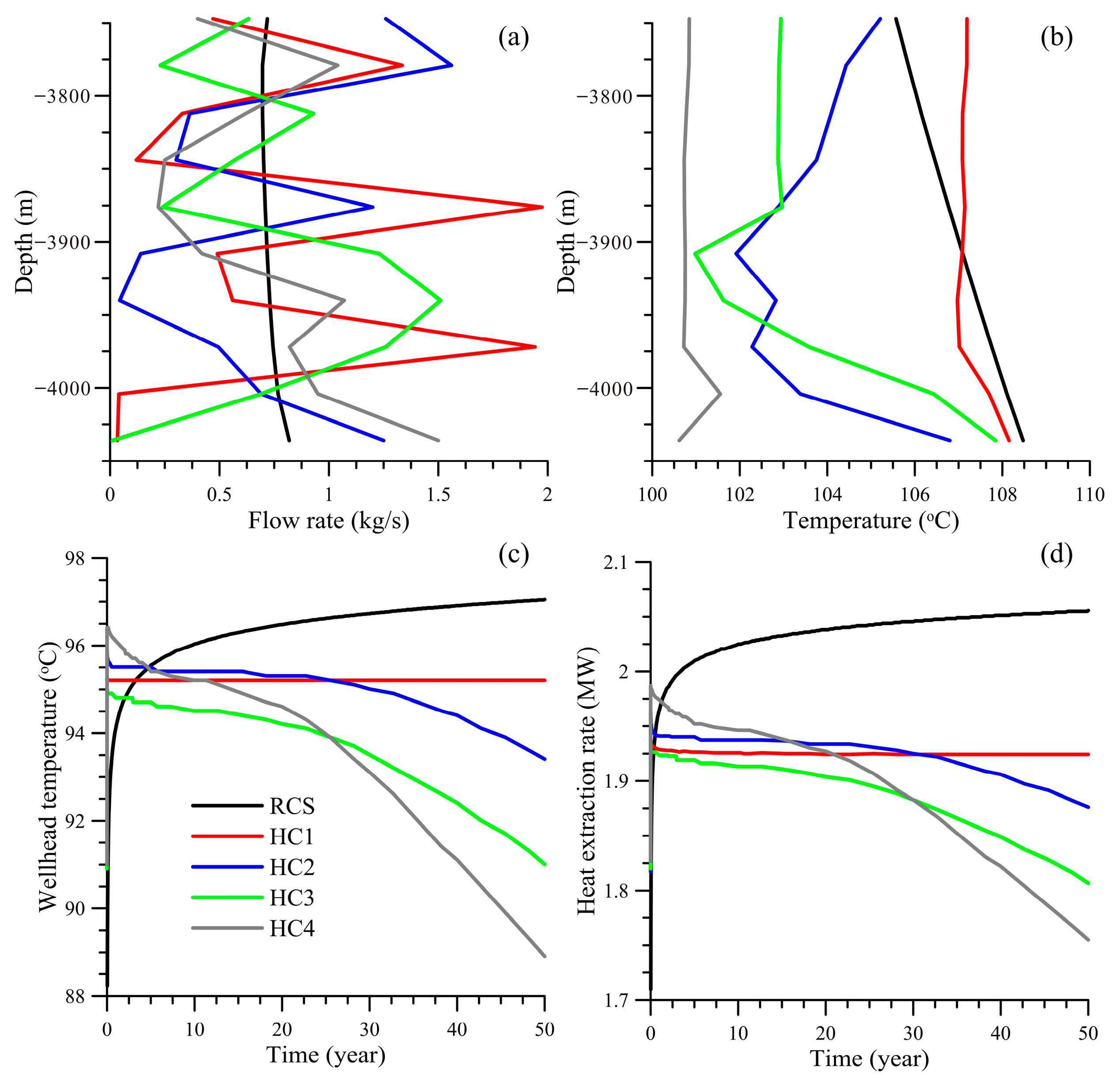

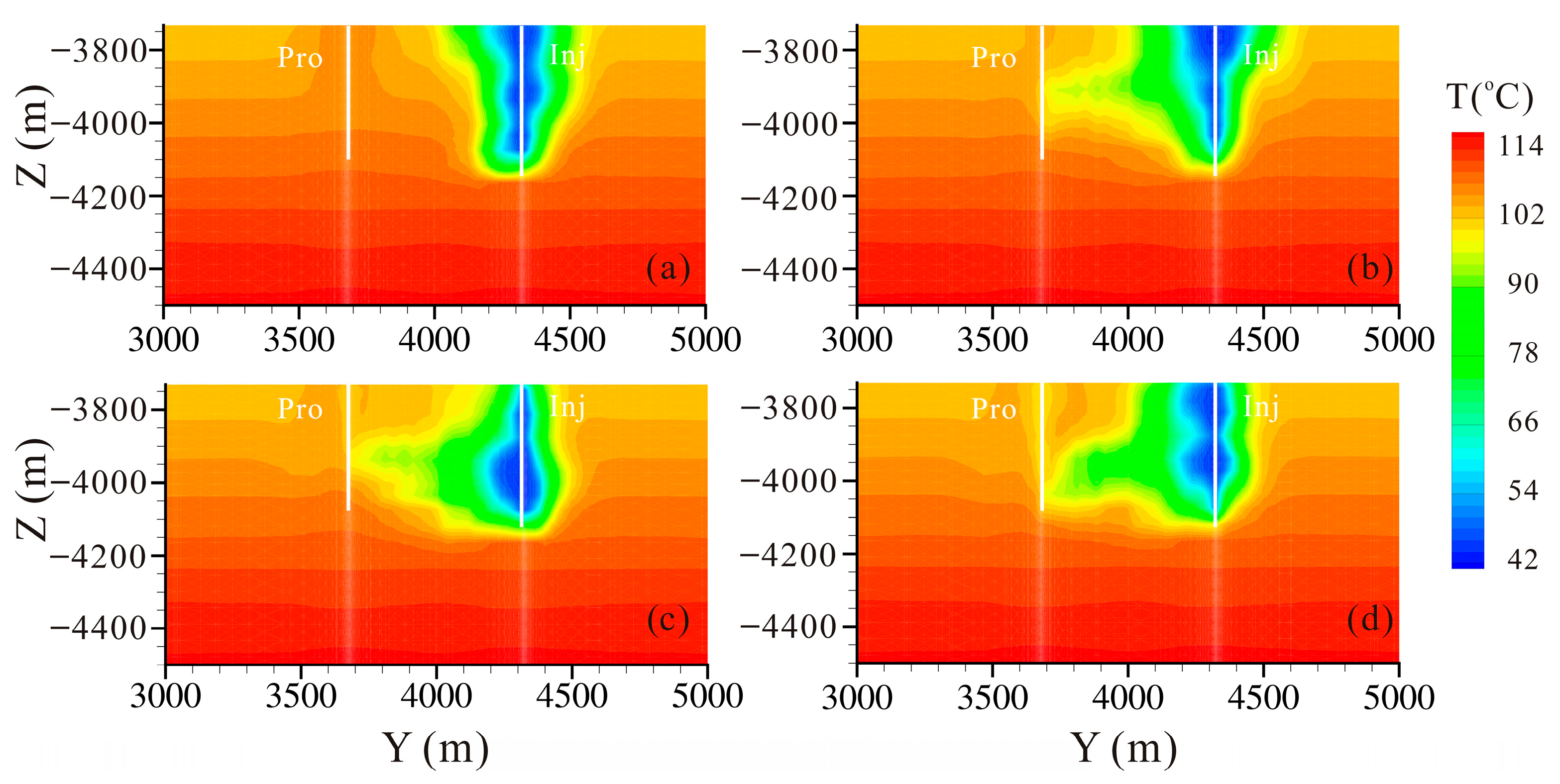

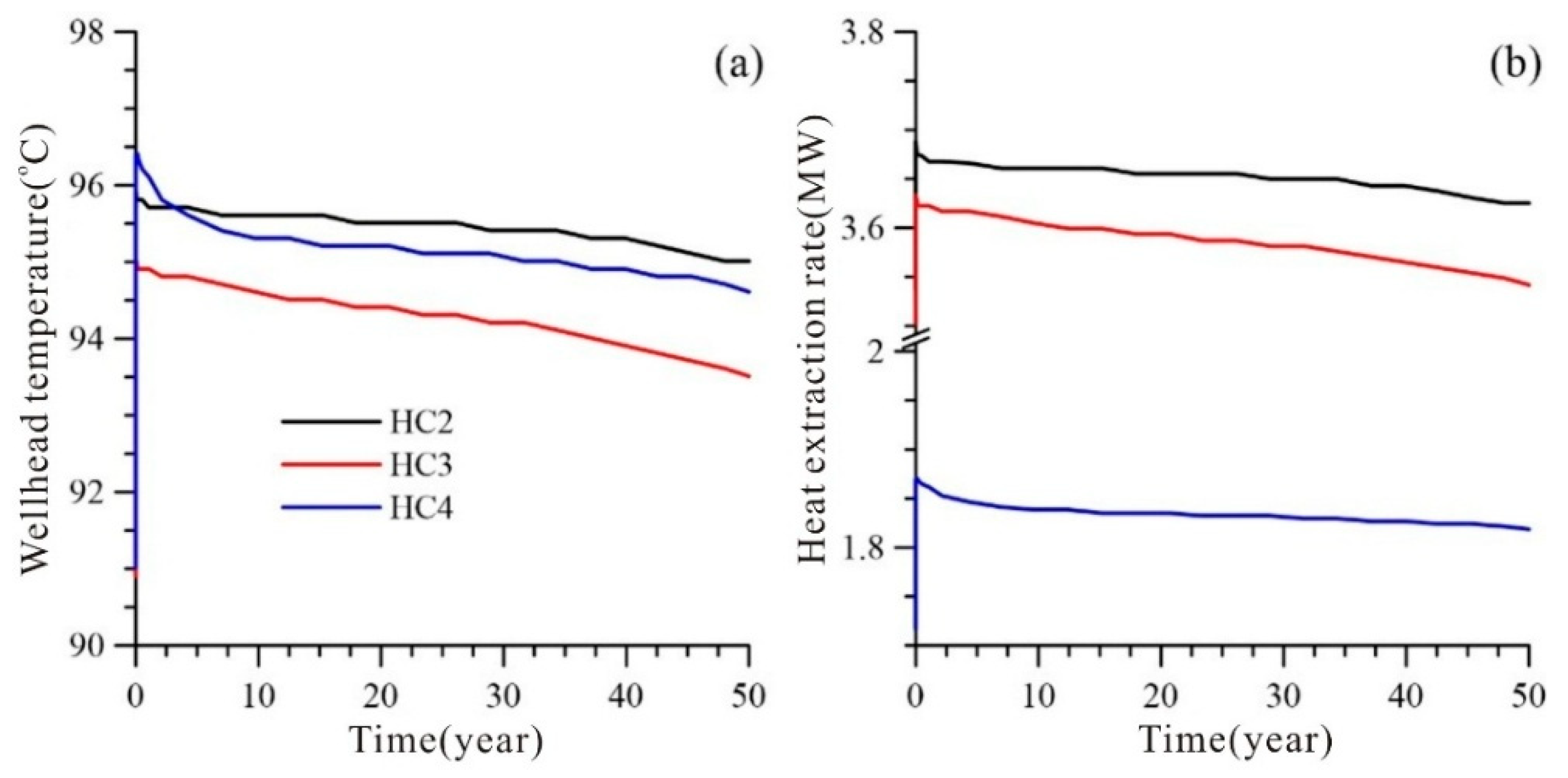

5.2.2. Heterogeneous Reservoir

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The steady-state temperature profile is governed by borehole temperature and thermal conductivity. The geothermal gradient decreases with an increase in the thermal conductivity of the rock matrix and increases with a rise in borehole temperature. The results from natural state modeling show that the thermal conductivity of the Jxw Formation (2.93~4 W/m·°C) is higher than that of the Q (2.3 W/m·°C), Nm, and Ng Formations (2.5 W/m·°C).

- (2)

- The results of inverse modeling based on pumping tests show that the calibrated borehole (at a depth of 4051 m) temperature is 109 °C, which is 4 °C higher than the measured value (105 °C). Because geophysical well logging was conducted immediately after well completion of well CGSD-01, it is inferred that the measured values were affected by drilling fluid. The identified permeability of the Wumishan Formation of Panzhuang Uplift is 5.25 × 10−14 m2.

- (3)

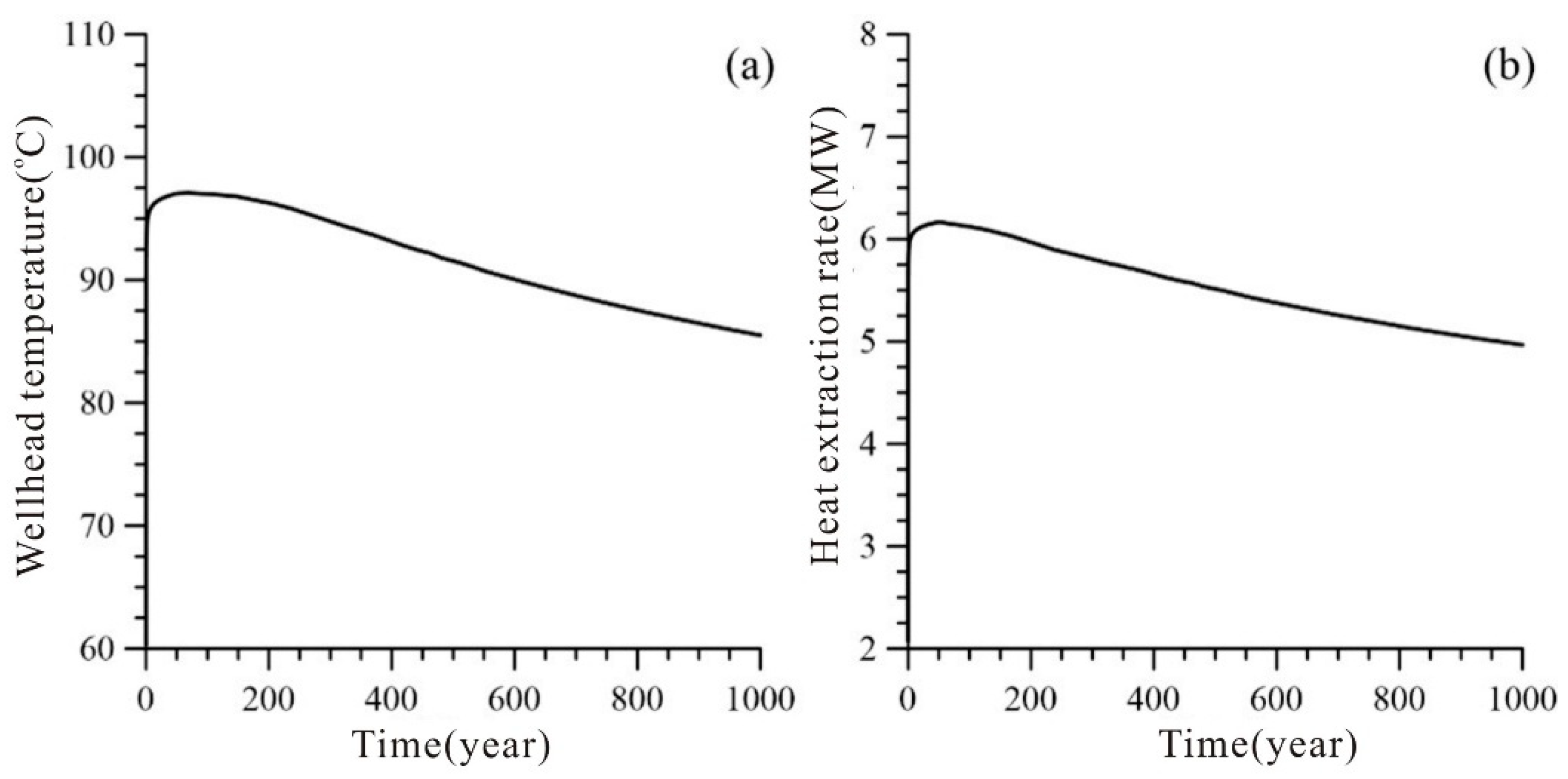

- Taking the actual heating area (1.33 × 105 m2) demand as the optimization objective, the engineering operation parameters of the geothermal doublet system under homogeneous reservoir conditions are adjusted. The optimization results are as follows: the optimal flow rate is 80 m3/h, the optimal perforated length of the injection well varies from 360 to 388 m, and the optimal injection temperature is 30 °C, with a wellhead temperature of 97 °C and a heat extraction rate of 6.17 MW.

- (4)

- From the perspective of the long-term benefit associated with project operation, the risk of geothermal breakthrough was comprehensively evaluated. In the case of only considering a homogeneous reservoir, this designed geothermal doublet can achieve stable operation for at least 200 years, with a temperature reduction of 0.85 °C and an HER ranging from 4.97 to 6.17 MW. Such results indicate that the geothermal doublet can provide a solid technical basis for the project’s long-term planning and risk management.

- (5)

- In the case of heterogeneous scenarios listed above, the high-permeability channels between wells can promote the occurrence of thermal breakthrough, thereby significantly reducing the stable operating flow rate of the geothermal doublet. Therefore, when optimizing well location layout, it is necessary to have a clearer understanding of the distribution characteristics of underground high-permeability channels.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rao, Y.; Wu, C.; He, Q. The antagonistic effect of urban growth pattern and shrinking cities on air quality: Based on the empirical analysis of 174 cities in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 97, 104752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Cao, M.; Liu, P. Development and utilization of geothermal energy in China: Current practices and future strategies. Renew. Energy 2018, 125, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Sun, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhao, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, D. Geothermal resource distribution and prospects for development and utilization in China. Natural Gas Ind. B 2024, 11, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, C.; Wang, Y.; Wen, D.G.; Xu, T.; Gherardi, F. Research Progress and Technical Challenges of Geothermal Energy Development from Hot Dry Rock: A Review. Energies 2025, 18, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.S.; Shi, C.Y.; Zhu, Z.M.; Lin, H.X.; Li, Z.H.; Du, F.; Cao, Z.Z.; Lu, P.T.; Liu, L. Overburden failure characteristics and fracture evolution rule under repeated mining with multiple key strata control. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R. User’s Guide for Aquifer; Waterloo Hydrogeologic Incorporated: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Malama, B.; Kuhlman, K.L.; Barrash, W. Semi-analytical solution for flow in a leaky unconfined aquifer toward a partially penetrating pumping well. J. Hydrol. 2008, 356, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, G.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, F. A new well pattern of cluster-layout for deep geothermal reservoirs: Case study from the Dezhou geothermal field, China. Renew. Energy 2020, 155, 484–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Dou, Z.; Liu, G.; Chen, S.; Tan, X. Equivalent flow channel model for doublets in heterogeneous porous geothermal reservoirs. Renew. Energy 2021, 172, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, T.; Chen, Y.L.; Wang, S.; Jia, W.J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, K.; Li, Z.L. Water injection softening modeling of hard roof and application in Buertai coal mine. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.T.; Wen, D.G.; Feng, B.; Li, F.Y.; Yue, D.D.; Zhang, Q.X.; Wang, J.Z.; Feng, Z.L. Numerical optimization of geothermal energy extraction from deep karst reservoir in North China. Renew. Energy 2023, 202, 1071–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, F.Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, Y.J.; Li, R.R. Exploring the formation mechanism of cold mineral springs in the potassic basaltic region of Wudalianchi, Northeast China. Chem. Geol. 2025, 689, 122862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.Y.; Guo, X.; Qi, X.F.; Feng, B.; Liu, J.; Xie, Y.P.; Gu, Y.M. A Surrogate Model-Based Optimization Approach for Geothermal Well-Doublet Placement Using a Regularized LSTM-CNN Model and Grey Wolf Optimizer. Sustainability 2025, 17, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Guo, X.; Zhang, H.K.; Feng, B.; Yuan, Y.L.; Li, F.Y.; Liu, J. A Simulation-Optimization Approach of Geothermal Well-Doublet Placement in North China Using Back Propagation Neural Network and Genetic Algorithm. Water 2025, 17, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, G.; Xu, H. A robust optimization approach of well placement for doublet in heterogeneous geothermal reservoirs using random forest technique and genetic algorithm. Energy 2022, 254, 124427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.F.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, J. A time-series forecasting model-based optimization approach for well-doublet system in geothermal reservoirs under geological uncertainty. Energy 2025, 330, 136926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, T.; Liang, X.; Zhang, S. Evaluation and Optimization of Heat Extraction Strategies Based on Deep Neural Network in the Enhanced Geothermal System. J. Energy Eng. 2022, 149, 04022050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, H.; Zhang, J.; Kong, X.; Yuan, L. A robust assessment method of recoverable geothermal energy considering optimal development parameters. Renew. Energy 2022, 201, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, V.; Bouzit, M.; Lopez, S. Assessment of complex well architecture performance for geothermal exploitation of the Paris basin: A modeling and economic analysis. Geothermics 2016, 64, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tan, X.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, J.; He, J.; Shi, Q. Coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical modeling on geothermal doublet subject to seasonal exploitation and storage. Energy 2024, 293, 130650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Oldenburg, C.M. T2Well-An integrated wellbore-reservoir simulator. Comput. Geosci. 2014, 65, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.F.; Li, F.Y.; Feng, B.; Feng, G.H.; Jiang, Z.J. Numerical evaluation of the performance of a single-well groundwater source heat pump system in Beijing, China. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2020, 38, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; HU, Z.; Feng, B.; Li, F.Y.; Jiang, Z.J. Numerical evaluation of building heating potential from a coaxial closed-loop geothermal system using wellbore-reservoir coupling numerical model. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2020, 38, 733–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HU, Z.; Xu, T.F.; Feng, B.; Yuan, Y.L.; Li, F.Y.; Feng, G.H.; Jiang, Z.J. Thermal and fluid processes in a closed-loop geothermal system using CO2 as a working fluid. Renew. Energy 2020, 154, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Xu, T.; Gherardi, F.; Jiang, Z.; Bellani, S. Geothermal assessment of the Pisa plain, Italy: Coupled thermal and hydraulic modeling. Renew. Energy 2017, 111, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.Y.; Xu, T.; Li, S.; Feng, B.; Jia, X.; Feng, G.H.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, Z.J. Assessment of Energy Production in the Deep Carbonate Geothermal Reservoir by Wellbore-Reservoir Integrated Fluid and Heat Transport Modeling. Geofluids 2019, 2019, 8573182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Xu, T.; Yuan, Y.; Gherardi, F.; Feng, B.; Jiang, Z.J.; Hu, Z. Enhanced heat extraction for deep borehole heat exchanger through the jet grouting method using high thermal conductivity material. Renew. Energy 2021, 177, 1102–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Xu, T.; Yuan, Y.; Feng, B.; ShangGuan, S. Enhanced heat extraction performance from deep buried U-shaped well using the high-pressure jet grouting technology. Renew. Energy 2023, 202, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Xu, T.; Yuan, Y.; Gherardi, F.; Tian, H.L. Single well geothermal heating systems: Technical and economic assessment of two widely-used configurations. J. Hydrol. 2024, 635, 131126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Song, Z.; He, G.; Li, S.; Xu, B.; Ma, H.; Du, Y.; Yin, G. Application of muti-process combined well flushing and pumping test in well CGSD-01. Explor. Eng. Rock Soil Drill. Tunneling 2019, 46, 8–13. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Zhang, K.N.; Cao, X.Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, C.B. IGMESH: A convenient irregular-grid-based pre- and post-processing tool for TOUGH2 simulator. Comput. Geosci. 2016, 95, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruess, K.; Oldenburg, C.M.; Moridis, G.J. TOUGH2 User’s Guide Version 2; Office of Scientific & Technical Information Technical Reports; Office of Scientific & Technical Information: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Xu, T.; Yuan, Y.; Gherardi, F.; Tian, H.L. Numerical analysis of coupled thermal-hydraulic processes based on the embedded discrete fracture modeling method. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 253, 123765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Xu, T.; Gherardi, F.; Yuan, Y. Comparison of CO2 and water as working fluids for an enhanced geothermal system in the Gonghe Basin, northwest China. Gondwana Res. 2023, 122, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, J.E. PEST: Model Independent Parameter Estimation; Watermark Computing: Corinda, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L. Sustainable Development and Utilization of Thermal Groundwater Resources in the Geothermal Reservoir of the Wumishan Group in Tianjin. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China, 2006. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Tian, G. Sustainable Development and Utilization of Geothermal Resources in the Donglihu Hot Spring Resort of Tianjin. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China, 2014. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Z. Geothermal Reinjection Numerical Simulation and Resource Evaluation of the Wumishan Group in Dongli District of Tianjin. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China, 2016. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.J.; Xu, T.; Wang, Y. Enhancing heat production by managing heat and water flow in confined geothermal aquifers. Renew. Energy 2019, 142, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Pang, J.; Kong, Y.; Luo, L.; Duan, Z.; Yang, F.; Wang, S. Large Karstic Geothermal Reservoirs in Sedimentary Basins in China: Genesis, Energy Potential and Optimal Exploitation. In Proceedings of the World Geothermal Congress (WGC-2015), Melbourne, Australia, 16–24 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vinsome, P.K.W.; Westerveld, J. A simple method for predicting cap and base rock heat losses in thermal reservoir simulators. J. Can. Pet. Tech. 1980, 19, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.F.; Yuan, Y.L.; Jia, X.F.; Lei, Y.D.; Li, S.T.; Feng, B.; Hou, Z.Y.; Jiang, Z.J. Prospects of power generation from an enhanced geothermal system by water circulation through two horizontal wells: A case study in the Gonghe Basin, Qinghai Province, China. Energy 2018, 148, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltelli, A.; Ratto, M.; Andres, T.; Campolongo, F.; Cariboni, J.; Gatelli, D.; Saisana, M.; Tarantola, S. Global Sensitivity Analysis. The Primer; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; p. 297. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H.L.; Pan, F.; Xu, T.; McPherson, B.J.; Yue, G.; Mandalaparty, P. Impacts of hydrological heterogeneities on caprock mineral alteration and containment of CO2 in geological storage sites. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2014, 24, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Cheng, J.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, T.; Liu, G.; Chen, S. Coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical-chemical modeling on acid fracturing in carbonatite geothermal reservoirs containing a heterogeneous fracture. Renew. Energy 2021, 172, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Layer | Porosity | Permeability (m2) | Rock Gain Density (kg/m3) | Specific Heat (J/kg·°C) | Thermal Conductivity (W/m·°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | 0.30 | 2.30 × 10−13 | 2600 | 919 | 1.8~2.3 |

| Nm | 0.29 | 4.60 × 10−13 | 2600 | 958 | 1.68~2.5 |

| Ng | 0.32 | 6.15 × 10−13 | 2600 | 909 | 1.68~2.5 |

| Є | 0.05 | 8.23 × 10−13 | 2760 | 827 | 1.68~3.2 |

| Qb | 0.05 | 2.09 × 10−13 | 2600 | 850 | 1.68~3.2 |

| Jxw | 0.05 | 3.65 × 10−13 | 2677 | 838 | 2.93~4.00 |

| Formation | Range W/(m·°C) | Initial Value W/(m·°C) | Optimal Value W/(m·°C) | 95% Confidence Interval | Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | 1.80~2.30 | 2.05 | 2.30 | 1.51~3.09 | 0.22 |

| Nm | 1.68~2.50 | 2.09 | 2.50 | 1.73~3.27 | 0.38 |

| Ng | 1.68~2.50 | 2.09 | 2.50 | 1.35~3.65 | 0.12 |

| Є | 1.68~3.20 | 2.44 | 2.79 | 1.60~3.97 | 0.14 |

| Qb | 1.68~3.20 | 2.44 | 1.68 | 6.87 × 10−2~3.29 | 8.51 × 10−2 |

| Jxw-4 | 2.93~4.00 | 3.47 | 4.00 | 2.46~5.54 | 0.11 |

| Jxw-3 | 2.93~4.00 | 3.47 | 4.00 | 2.56~5.44 | 0.20 |

| Jxw-2 | 2.93~4.00 | 3.47 | 2.93 | 2.31~3.55 | 0.16 |

| Observed Variables | Large Drawdown | Middle Drawdown | Small Drawdown |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow rate (m3/h) | 130.2 | 94.5 | 43.9 |

| Wellhead temperature (°C) | 98.5 | 98.5 | 94.0 |

| Groundwater depth (m) | 171.70 | 143.48 | 118.85 |

| Time of duration (h) | 62 | 24 | 16 |

| Parameter | Range | Initial Value | Optimal Value | 95% Confidence Interval | Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom temperature (°C) | 110~122 | 113.2 | 120.26 | 119.07~121.46 | 3.13 × 10−2 |

| Permeability (m2) | 3.65 × 10−15~3.65 × 10−12 | 3.65 × 10−14 | 5.25 × 10−14 | 7.82 × 10−15~2.03 × 10−13 | 2.65 × 1011 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Flow rate (m3/h) | 40~220, 80 |

| Perforated length of injection well (m) | 50~360, 360 |

| Perforated length of production well (m) | 336.68 |

| Injection temperature (°C) | 30~60, 30 |

| Wellbore radius (m) | 0.08 |

| Sequence Number | Start Depth (m) | End Depth (m) | Thickness (m) | Porosity (%) | Permeability (m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1869.5 | 1875.2 | 5.7 | 5.74 | 1.08 × 10−15 |

| 2 | 1884.2 | 1895.8 | 11.6 | 5.86 | 3.41 × 10−15 |

| 3 | 1909.8 | 1923.3 | 13.5 | 5.58 | 1.62 × 10−15 |

| 4 | 1927.9 | 1935.2 | 7.3 | 5.11 | 9.20 × 10−16 |

| 5 | 1942.7 | 1947.9 | 5.2 | 7.12 | 4.34 × 10−15 |

| 6 | 1955.2 | 1960.3 | 5.1 | 10.10 | 9.75 × 10−15 |

| 7 | 1973.3 | 1982.2 | 8.9 | 8.22 | 4.14 × 10−15 |

| 8 | 1987.6 | 1992.8 | 5.2 | 12.58 | 1.94 × 10−14 |

| 9 | 1997.6 | 2015.6 | 18.0 | 8.30 | 2.88 × 10−14 |

| 10 | 2023.3 | 2027.8 | 4.5 | 6.68 | 1.65 × 10−15 |

| 11 | 2036.3 | 2040.9 | 4.6 | 8.08 | 3.56 × 10−15 |

| 12 | 2043.8 | 2058.6 | 14.8 | 8.61 | 2.35 × 10−14 |

| 13 | 2080.6 | 2087.8 | 7.2 | 9.97 | 2.77 × 10−14 |

| 14 | 2154.1 | 2165.7 | 11.6 | 3.98 | 5.40 × 10−16 |

| 15 | 2170.9 | 2185.0 | 14.1 | 8.57 | 5.13 × 10−15 |

| 16 | 2214.7 | 2225.8 | 11.1 | 5.81 | 1.91 × 10−15 |

| 17 | 2255.7 | 2262.8 | 7.1 | 8.71 | 5.61 × 10−15 |

| 18 | 2273.9 | 2288.5 | 14.6 | 4.12 | 5.50 × 10−16 |

| 19 | 2316.5 | 2323.8 | 7.3 | 5.04 | 6.10 × 10−16 |

| 20 | 2339.6 | 2345.3 | 5.7 | 9.46 | 1.71 × 10−14 |

| 21 | 2367.7 | 2375.3 | 7.6 | 6.59 | 4.14 × 10−15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, F.; Guo, X.; Xing, Z.; Cui, H.; Zhang, X. Geothermal Reservoir Parameter Identification by Wellbore–Reservoir Integrated Fluid and Heat Transport Modeling. Water 2025, 17, 3269. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223269

Li F, Guo X, Xing Z, Cui H, Zhang X. Geothermal Reservoir Parameter Identification by Wellbore–Reservoir Integrated Fluid and Heat Transport Modeling. Water. 2025; 17(22):3269. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223269

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Fengyu, Xia Guo, Zhenxiang Xing, Haitao Cui, and Xi Zhang. 2025. "Geothermal Reservoir Parameter Identification by Wellbore–Reservoir Integrated Fluid and Heat Transport Modeling" Water 17, no. 22: 3269. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223269

APA StyleLi, F., Guo, X., Xing, Z., Cui, H., & Zhang, X. (2025). Geothermal Reservoir Parameter Identification by Wellbore–Reservoir Integrated Fluid and Heat Transport Modeling. Water, 17(22), 3269. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223269