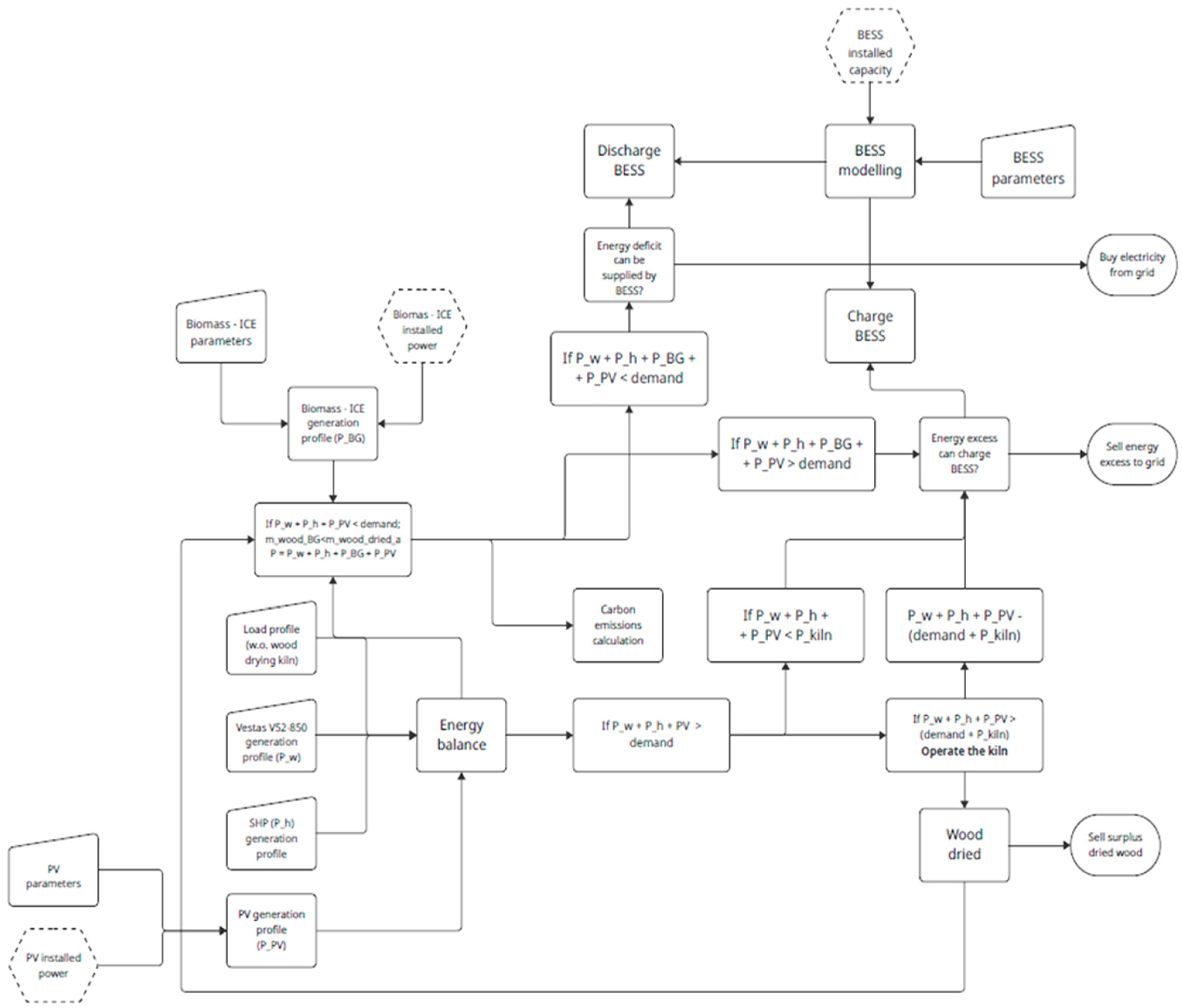

3.1. Input Data

The definition of several parameters is necessary for the simulations, such as those presented in

Table 7. This table lists all variables corresponding to what is called scenario 1, illustrating the complexity of the simulation tool and hybrid energy platform developed for renewable energy optimization, which can be applied in different sectors.

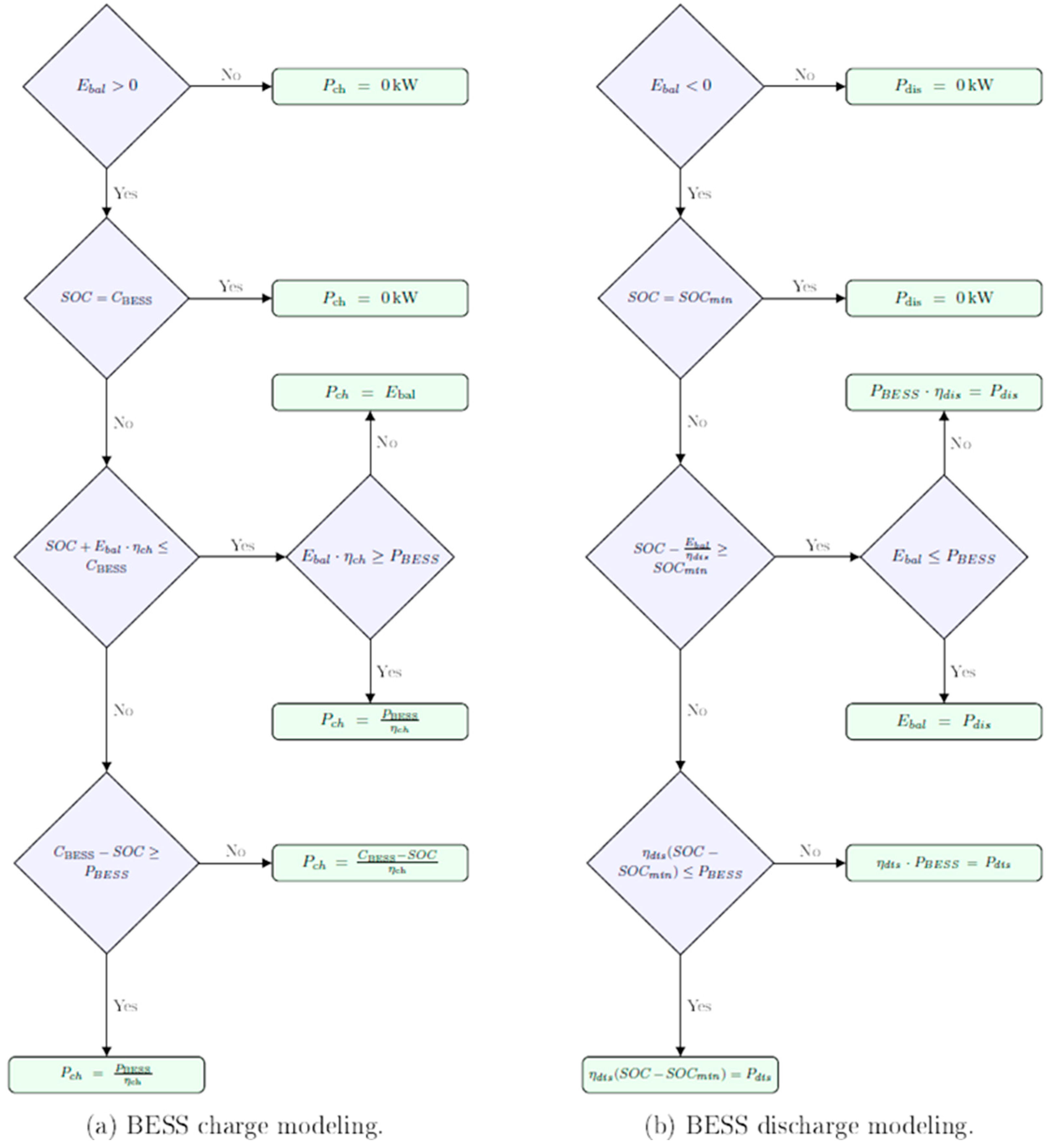

The system integrates multiple renewable energy sources, including hydropower with a capacity of 380 kW, wind power at 850 kW, and a biomass gasifier producing 2000 kWh per ton of wood. The biomass used is Sitka spruce, with a lower heating value of 3811 kWh/t and a moisture content of 20%. The biomass-to-electricity conversion efficiency is 25%. Financially, the system operates under an interest rate of 5.66%, a discount rate of 6%, and an inflation rate of 3%. Corporate tax is set at 12.5%, while inflation rates for PV converters and BESS are negative at −5% and −5.7%, respectively. Capital costs include EUR 500,000 per wind turbine, EUR 100,000 per SHP unit, EUR 3000/kW for biomass gasifiers, EUR 1000/kW for PV systems, EUR 150/kWp for PV converters, and EUR 1000/kW for BESS power capacities. Fixed operation and maintenance costs are EUR 25,782/year for wind turbines, EUR 30,000/year for SHP, EUR 28.91/kW for PV, and EUR 25/kW for the BESS. The grid allows a feed-in limit of 500 kW, with biomass gasifiers representing 12% of installed capacity. Battery energy storage systems (BESSs) start with a state of charge (SOC) of 25%, operate with 95% charge/discharge efficiency, and maintain a minimum SOC of 10%. Their energy-to-power ratio is 4. Emission data show that biomass gasifiers emit 69 g CO2/kWh, while grid electricity emits 187 g CO2/kWh. Carbon tax is not defined, but its growth rate is set at 3%. Variable operating costs include EUR 40/t for wood chip purchases and EUR 120/t for sales. Biomass gasifiers under 100 kW incur EUR 0.15/kWh in O&M costs, while those over 100 kW cost EUR 0.10/kWh. The system and biomass gasifier lifetimes are 25 years, with wind turbines lasting 20 years and SHP up to 50 years. PV modules and converters last 25 and 15 years, respectively, while a BESS has a calendar life of 15 years and a cycle life of 5475 cycles. Depreciation is calculated over 8 years, and the residual value of biomass gasifiers after their lifetime is 10% of CAPEX. Market values for PV systems, converters, and BESSs are set to zero. Grid tariffs include a fixed feed-in rate of EUR 0.0946 and a fixed purchase price of EUR 0.3808.

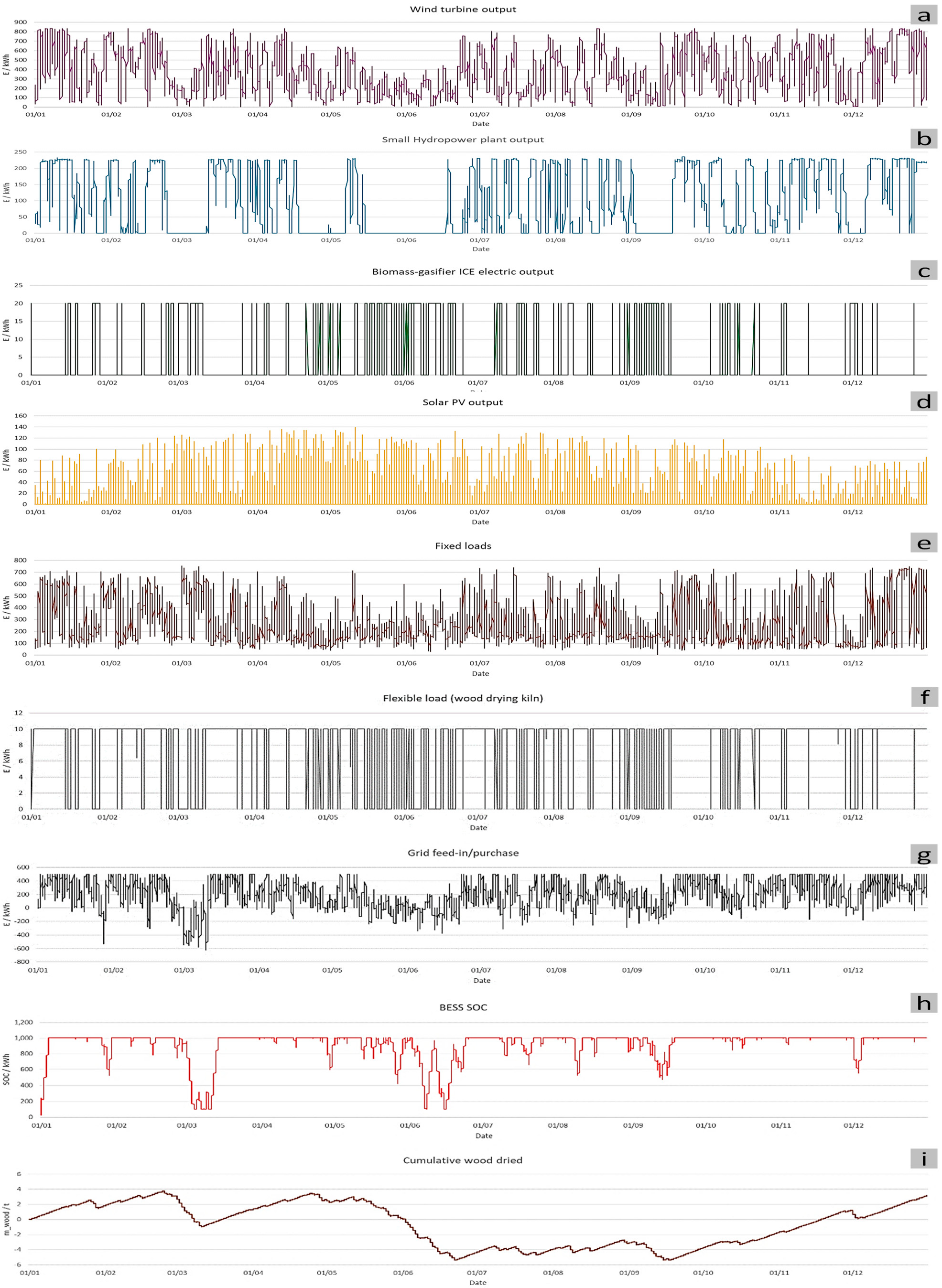

3.3. Technical Summary

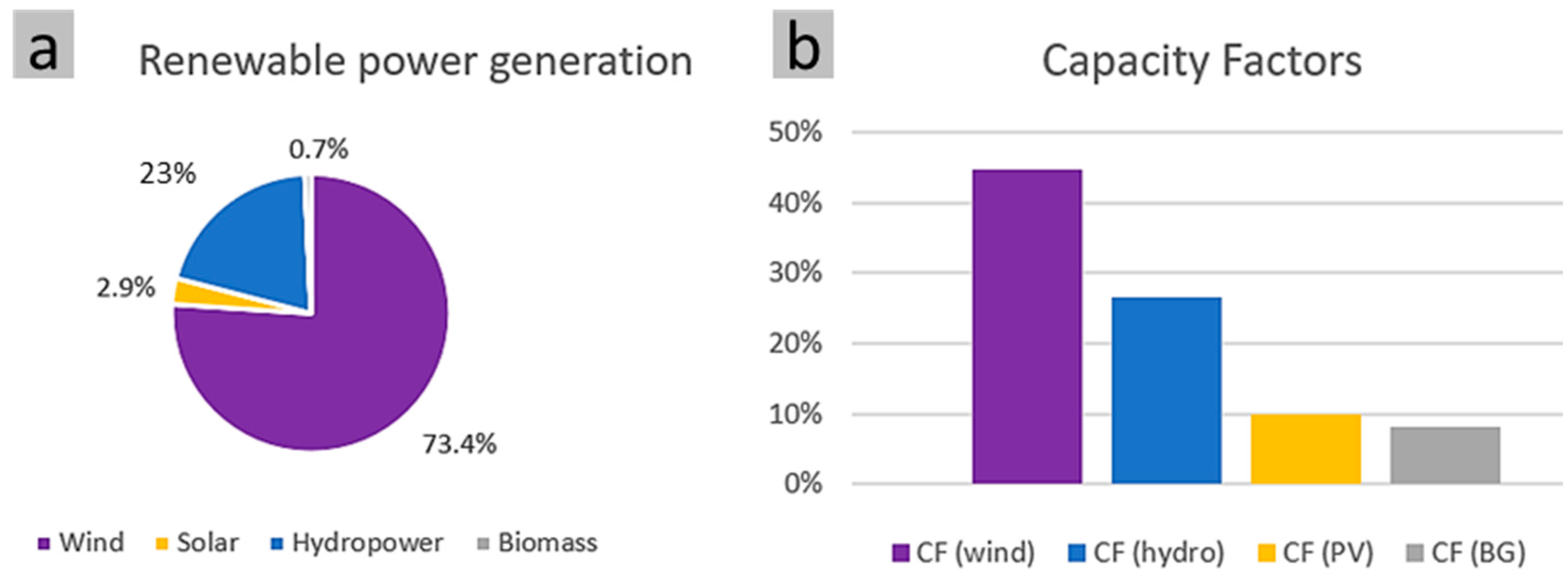

The energy system demonstrates a strong reliance on renewable sources (

Figure 6), with wind energy contributing the largest share at 3,262,431 kWh, representing 73.1% of total generation (

Table 8). Solar and hydropower follow with 884,225 kWh (19.8%) and 884,225 kWh (6.1%), respectively, while biomass plays a minimal role at 3999 kWh (0.1%). Overall, renewable sources account for 95.5% of the total generation, amounting to 4,459,694 kWh.

The system also imports 151,012 kWh from the grid, covering 3.2% of the energy demand. The contribution of each RES is shown in

Figure 7a. Electricity consumption is dominated by the system’s load, totaling 4,681,866 kWh. No energy is allocated to the drying kiln, while 151,012 kWh is fed back into the grid. The battery energy storage system (BESS) supports grid flexibility with 13,986.48 kWh of both charge and discharge, operating over a cycle life of 5475 cycles and a calendar life of 15 years. The system achieves a high self-sufficiency rate of 96.8%, indicating minimal dependence on external energy sources. Its self-consumption rate stands at 50.7%, reflecting the efficient use of locally generated energy.

The technical summary highlights key performance metrics related to wood usage, carbon emissions, and generation efficiency. The system consumes 35.73 tons of wood, with 51% of it used in the gasification process. Carbon emissions from biomass gasification amount to 35.95 g CO

2 eq./kWh, while grid electricity contributes slightly less at 32.36 g CO

2 eq./kWh. The overall system emissions average 33.87 g CO

2 eq./kWh. In terms of utilization, wind energy shows the highest operational efficiency, with 3970 full-load hours, followed by hydropower at 2367 h. PV systems operate for 876 h, and biomass gasification operates for 682 h. The capacity factors reflect this trend, with wind at 45%, hydro at 27%, PV at 10%, and biomass gasification at 8%, indicating wind as the most productive source in the system (

Figure 7b).

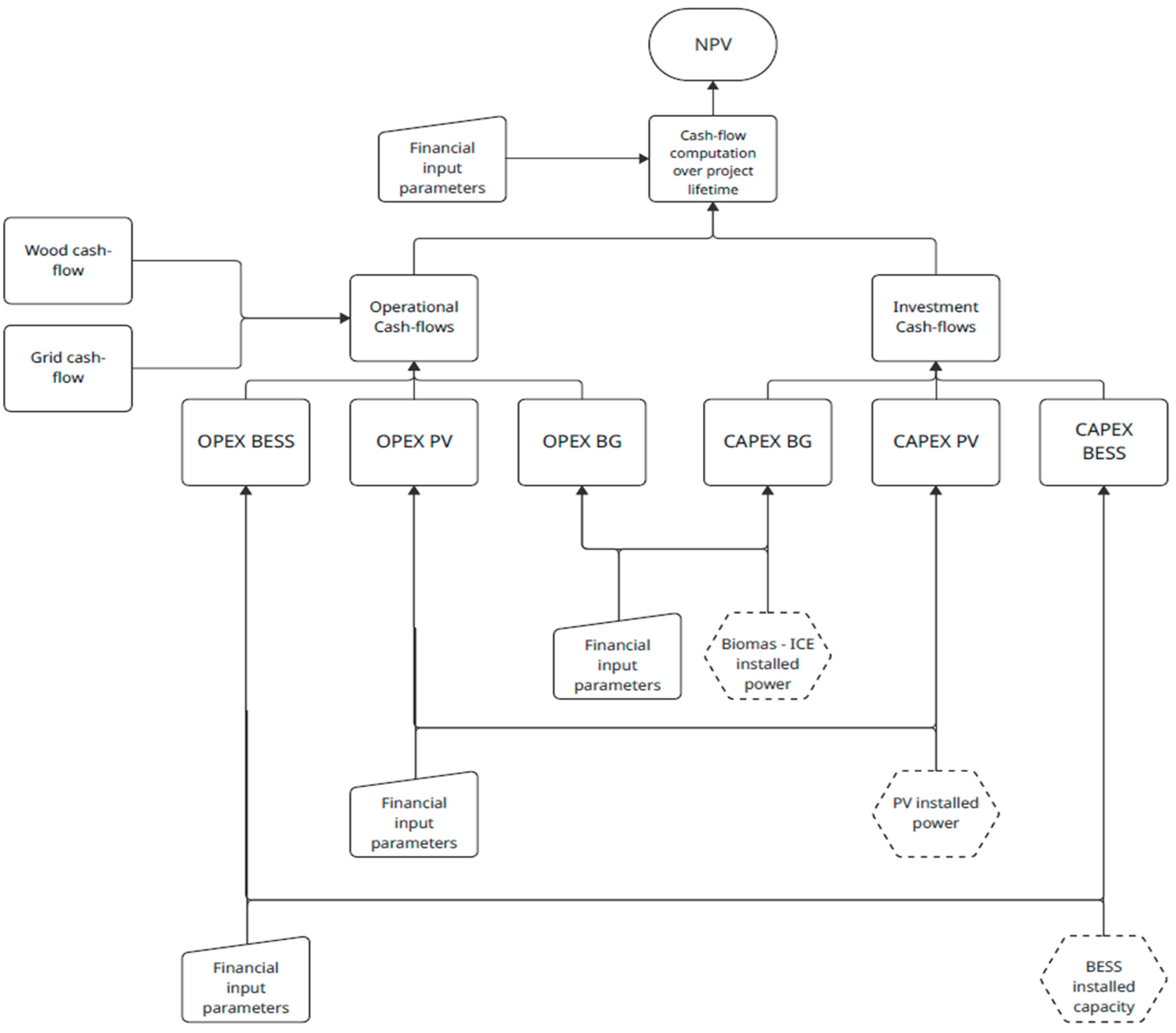

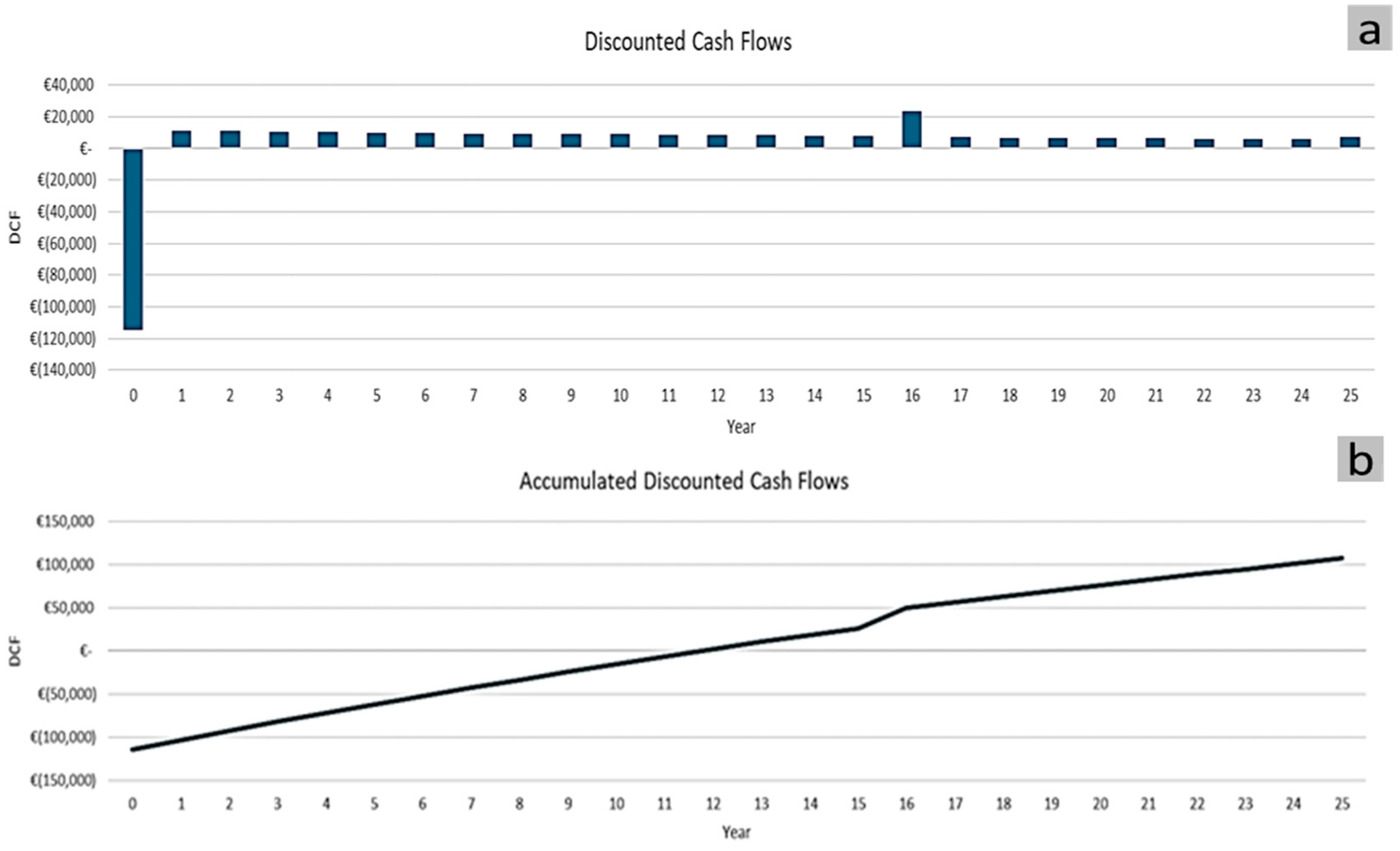

3.4. Financial Summary

The financial results from scenario 1 indicate that the project is economically viable, with a net present value (NPV) of EUR 107,290.91, suggesting a positive return over its operational lifetime. The internal rate of return (IRR) stands at 12%, which is comfortably above typical discount rates, reinforcing the attractiveness of the investment. However, the modified internal rate of return (MIRR) is slightly lower at 8%, reflecting more conservative reinvestment assumptions. The total investment required is EUR 114,500, and the payback period is estimated at 16.05 years. While this is relatively long, it is not uncommon for renewable energy infrastructure projects of this type. In terms of energy cost efficiency, the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for biomass gasification is notably high at EUR 1287/MWh, indicating that this technology is less cost-effective within the scenario. In contrast, photovoltaic generation offers a much lower LCOE of EUR 192/MWh, making it a more economically favourable option.

Table 9 presents a resume of financial investments with respect to Scenario 1, which is primarily driven by the performance of the PV system, while the high cost of biomass energy may allow reconsideration or optimization.

Figure 8a illustrates the discounted cash flows over a 25-year period for the project. It shows a significant initial investment in Year 0, represented by a large negative cash flow. Subsequent years exhibit relatively stable and modest positive returns, indicating consistent financial performance. Overall, the cash-flow trend supports a gradual return on investment, aligning with the long payback period observed in the financial results.

Figure 8b presents the accumulated discounted cash flows over 25 years, showing a steady upward trajectory after the initial investment. The curve crosses into positive territory around Year 16, confirming the payback period. A noticeable increase around Year 15 suggests a financial boost, possibly from asset recovery or reduced costs. Overall, the project demonstrates gradual capital recovery and long-term profitability, culminating in a positive net return by the end of its lifetime.

3.5. Sensitivity Analyses

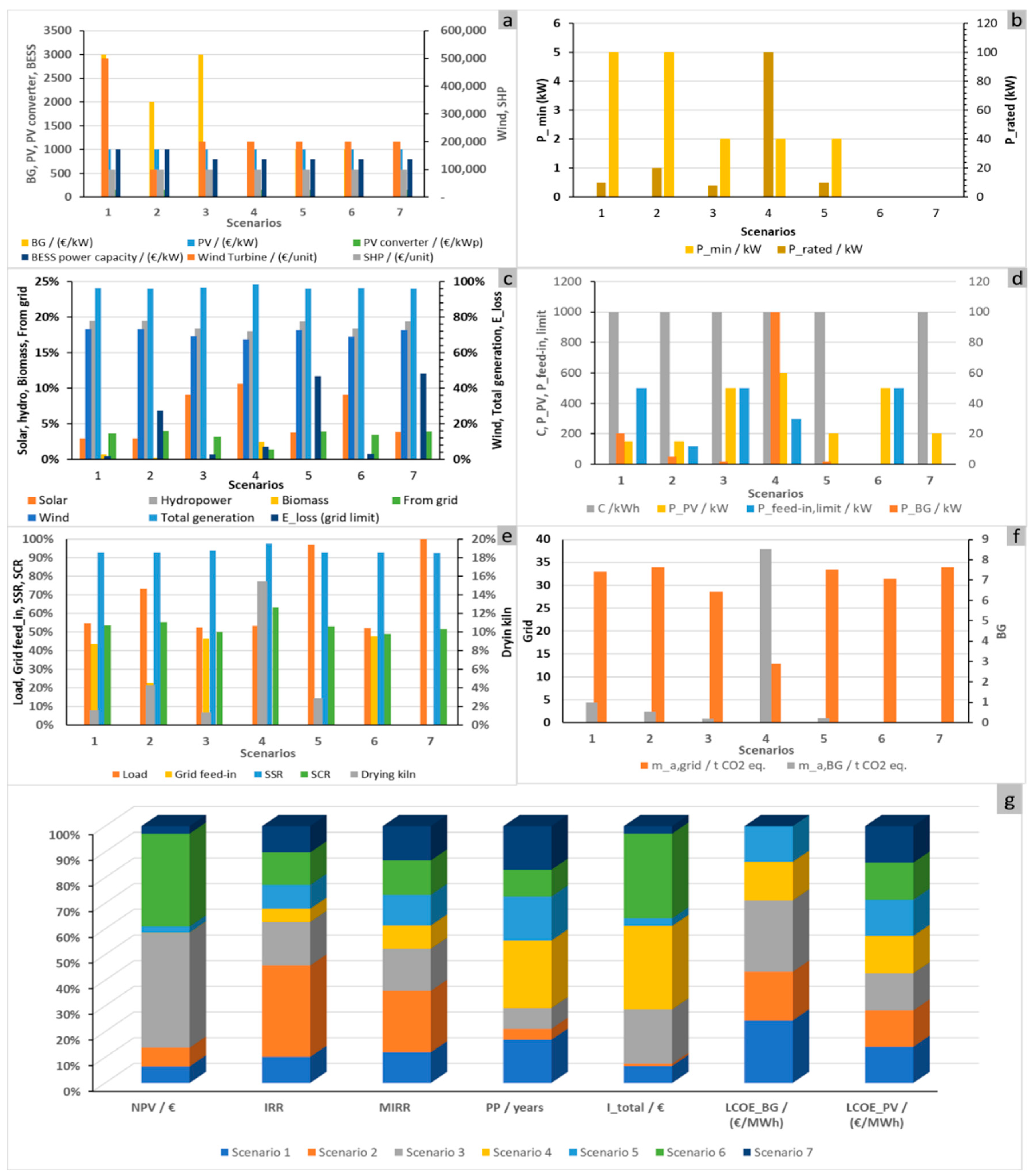

The developed analysis explores the techno-economic and environmental performance of these hybrid renewable energy systems, with a focus on biomass, solar, wind, small hydropower (SHP), and battery energy storage systems (BESSs), where the following results are presented in

Figure 9.

From the seven scenarios (Sc1 to Sc7) modelled, the analysis explores techno-economic and environmental performances. Here is a breakdown of the key findings: In terms of technical configuration, with respect to the biomass drying kiln, the following conclusions are drawn: Only scenarios 1–5 include biomass kilns, with Sc4 having the highest rated power (100 kW). Sc6 and Sc7 exclude biomass entirely. Grid Feed-in Limits: These vary significantly from 0 kW (Sc5, Sc7) to 500 kW (Sc1, Sc3, and Sc6), influencing grid reliance and feed-in potential. Installed Capacities: PV ranges from 150 kW (Sc1, Sc2) to 600 kW (considering a future situation without this limitation) (Sc4). Biogas (BG) capacity peaks at 100 kW in Sc4, but it is zero in Sc6 and Sc7. With respect to storage performance, for BESS Usage, scenarios 1–5 utilize battery storage, with Sc2 showing the highest charge/discharge values. Sc6 and Sc7 omit BESSs, resulting in zero cycles and no storage contribution. Lifetime: Sc4’s BESS has the longest projected lifespan (861 cycles), likely due to its lower cycling intensity.

Based on the renewable generation mix by source and the type of scenarios, some highlights can be drawn: wind in Sc1, 2, 5, and 7 consistently presented high generation (~0.73). Solar in Sc4 has the highest share (10.6%). Hydropower is fairly stable at ~19% across all scenarios. Biomass in Sc4 presents the highest share (2.5%). Scenarios with higher renewable penetration show reduced grid reliance and emissions.

Regarding financial metrics, the NPV of Sc3 (EUR 741,293) has the stronger investment return. Sc2 exhibits fast payback and high profitability, with an IRR of 42%. For the payback period, Sc2 has 4 years and exhibits the quickest return on investment for all scenarios. Sc5 has the lowest biogas energy cost (LCOE_BG) of 734 EUR/MWh. Hence, Sc3 and Sc2 stand out financially, but Sc4 lags with a long payback (25 years) and low IRR (6%).

In terms of environmental impact and carbon emissions, scenario 4 (Sc4) achieves the lowest grid-related emissions (12.83 t CO2 eq.) due to its high renewable penetration and limited grid dependence; however, it also records the highest biogas emissions as a result of its large biogas capacity. Nevertheless, Sc4 attains the highest values for both the self-sufficiency ratio (SSR, 97.8%), indicating strong grid independence, and self-consumption ratio (63.4%), positioning it as technically robust and environmentally advantageous, albeit financially, it is less favourable. By contrast, Sc2 delivers the strongest economic performance while maintaining acceptable environmental outcomes. Sc3 balances a high net present value (NPV) with moderate emissions and solid renewable integration, whereas Sc6 and Sc7, lacking biomass and storage, exhibit limited sustainability and resilience.

A comparative evaluation of the seven scenarios (Sc1–Sc7) highlights pronounced trade-offs among technical performance, environmental impact, and financial feasibility, as summarised in

Table 10. Scenario 4 (Sc4) achieved the lowest grid-related carbon emissions, estimated at 12.83 t CO

2 equivalent, reflecting its strong renewable integration. However, this environmental advantage was offset by its limited financial viability, as evidenced by a minimal net present value (NPV) and a significantly prolonged payback period.

In contrast, Sc2 demonstrated outstanding financial feasibility, showing the highest IRR equal to 42% and the shortest payback, which was 4 years. Its technical efficiency was compromised by significant grid-related energy losses. Sc3 provided the most balanced outcome, combining the best NPV, which was equal to EUR 741,293, low emissions, and good renewable integration, defining moderate IRR and payback. Sc6 also performed strongly financially while maintaining low energy losses, but its lack of biomass and storage integration limited sustainability and autonomy. Scenarios 5 and 7, constrained by the absence of grid feed-in and/or biomass, show the highest energy losses (>45%), poor financial metrics, and weaker sustainability. Finally, Sc1 offered an intermediate pathway, with acceptable emissions, modest financial returns, and reasonable autonomy.

Hence, Sc3 showed the most balanced configuration, combining the highest NPV with moderate emissions and solid renewable integration. Unlike Sc2, which favoured financial returns at the expense of efficiency, or Sc4, which maximized environmental performance but suffered financially, Sc3 provided a practical, compromising solution. This balance makes it the most suitable scenario for real-world implementation within sustainable energy transition pathways.

3.6. Discussion

The comparative assessment of the seven modeled scenarios (Sc1–Sc7) reveals a complex interplay between technical configuration, financial viability, and environmental performance, underscoring the necessity of integrated evaluation frameworks for hybrid energy systems.

Technical and Environmental Trade-offs: Scenario 4 (Sc4) emerges as the technically strongest configuration, characterized by the highest rated biomass kiln power (100 kW), extensive renewable integration—particularly solar (10.6%) and biomass (2.5%)—and superior storage performance, with the longest battery lifespan (861 cycles). These attributes contribute to Sc4’s exceptional grid independence (SSR 97.8%) and lowest grid-related emissions (12.83 t CO2 eq.). However, its elevated biogas emissions and limited financial returns (NPV EUR 2241; IRR 6%) highlight the environmental–financial trade-off inherent in highly renewable systems.

Financial Performance and Efficiency: Scenarios 2 and 3 (Sc2, Sc3) demonstrate strong financial metrics, with Sc2 offering the fastest payback (4 years) and highest IRR (42%), albeit with significant energy losses (27.4%). Sc3, by contrast, balances economic and environmental dimensions, achieving the highest NPV (EUR 741,293), moderate emissions (28.52 t CO2 eq.), and robust renewable integration. This positions Sc3 as the most viable compromise between sustainability and profitability.

System Limitations and Design Implications: Scenarios 6 and 7, which exclude biomass and storage, exhibit constrained autonomy and sustainability. Sc6 performs well financially (NPV EUR 602,280) with low energy losses (3.0%), yet its lack of storage and biomass integration limits resilience. Sc7, with minimal IRR (0.12%) and high losses (48.4%), underscores the risks of under-investment in key system components. Similarly, Sc5’s absence of grid feed-in and high losses (46.7%) result in poor financial and environmental outcomes.

Strategic Insights for Implementation: The analysis confirms that no single scenario optimally satisfies all performance dimensions. Sc4 excels environmentally but lacks financial appeal; Sc2 maximizes returns but compromises efficiency; Sc3 offers a balanced configuration, making it the most suitable candidate for real-world deployment. These findings reinforce the value of multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) in guiding energy system design, where stakeholder priorities—be they environmental, economic, or technical—must be explicitly weighted.