Enhancing Flood Inundation Simulation Under Rapid Urbanisation and Data Scarcity: The Case of the Lower Prek Thnot River Basin, Cambodia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Model Framework

2.3. RRI Model

2.4. Target Event

3. Data Augmentation

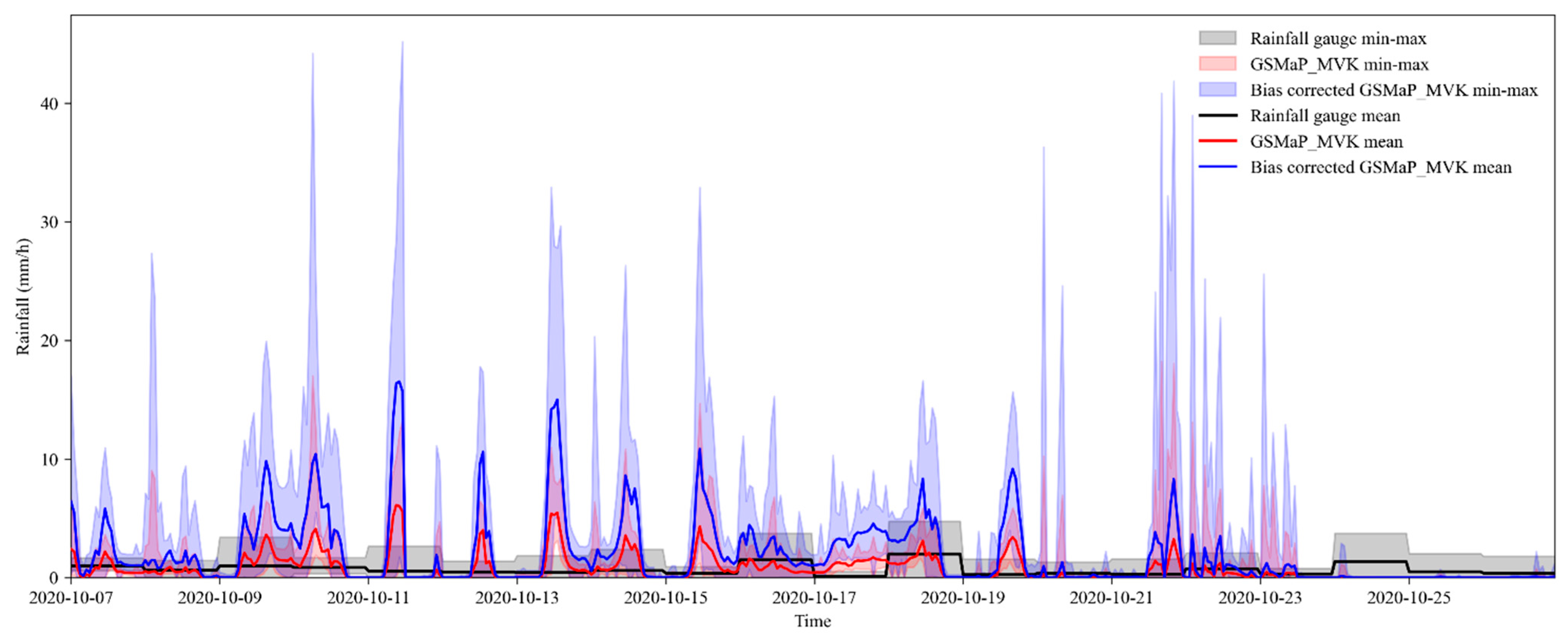

3.1. Meteorological Data

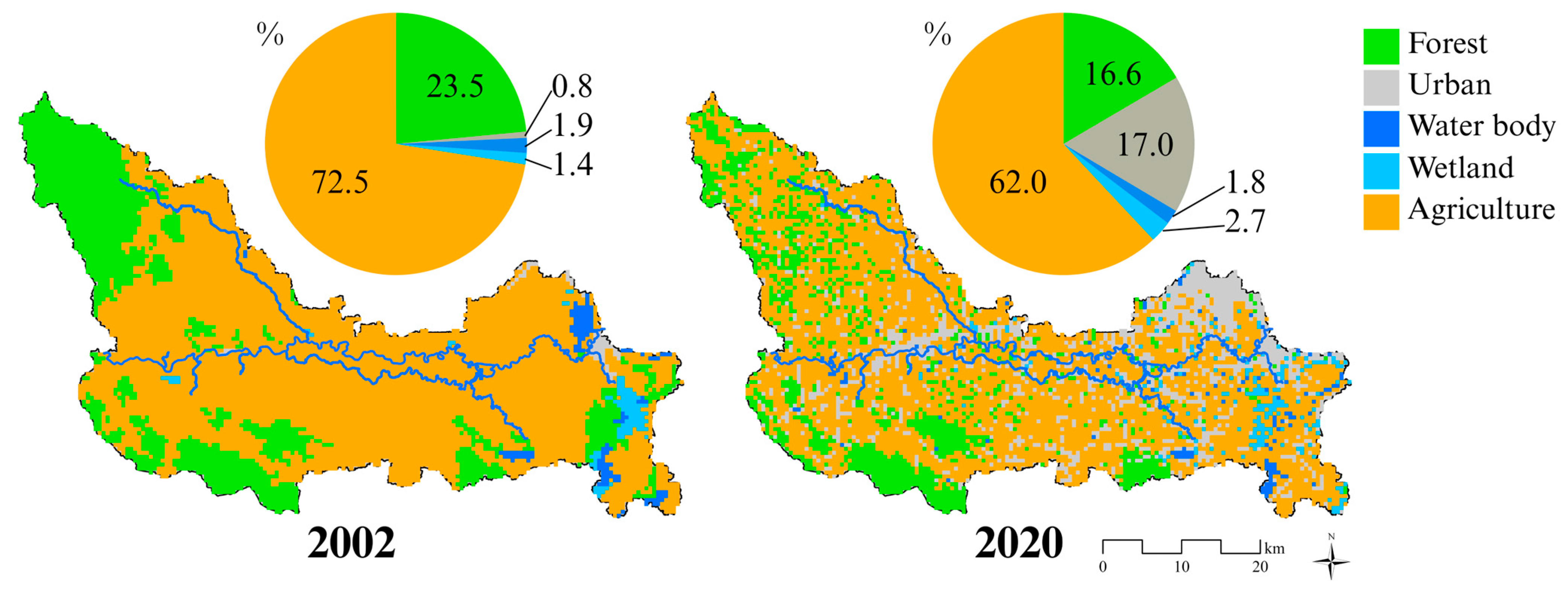

3.2. Land Use Data

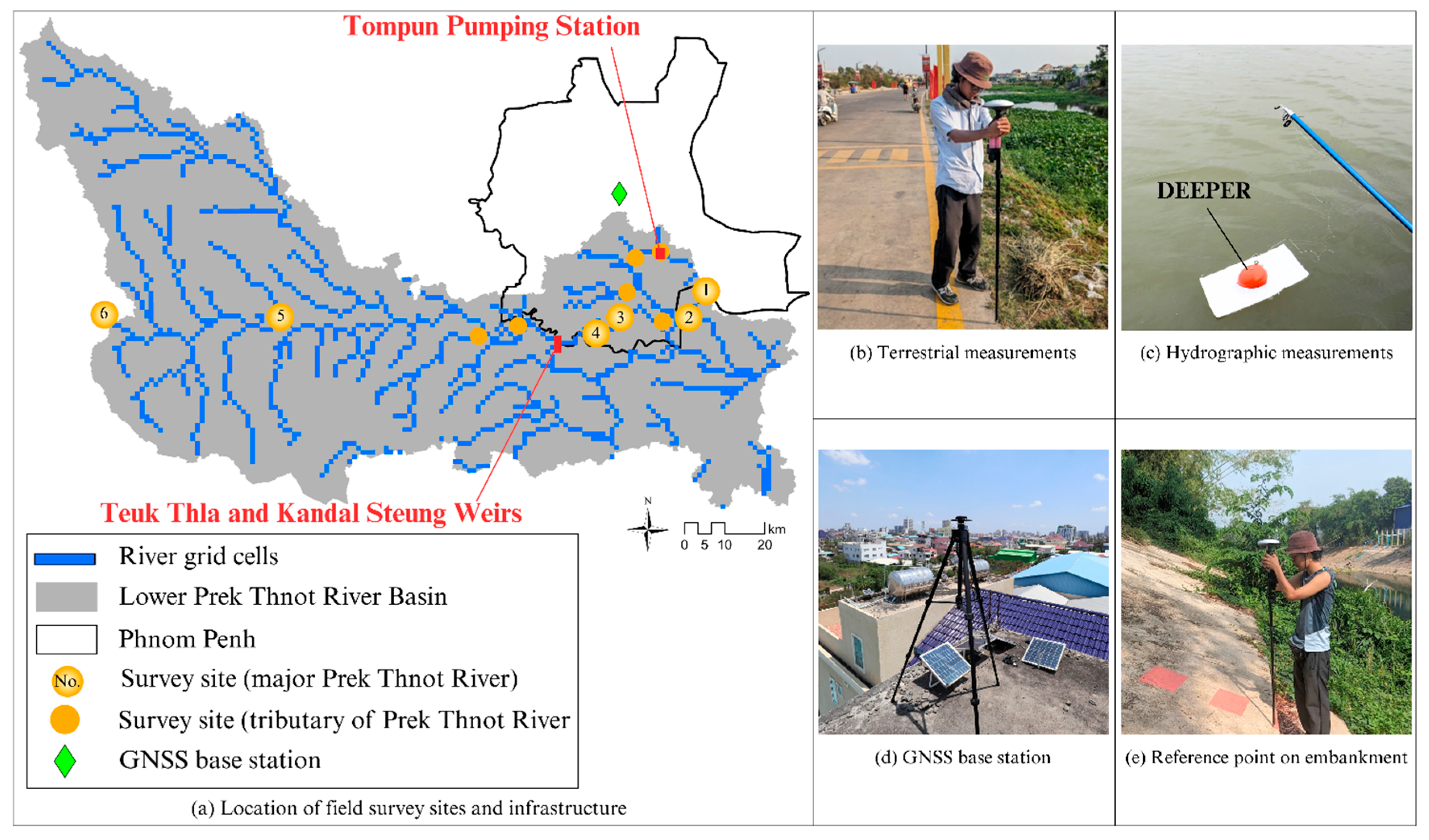

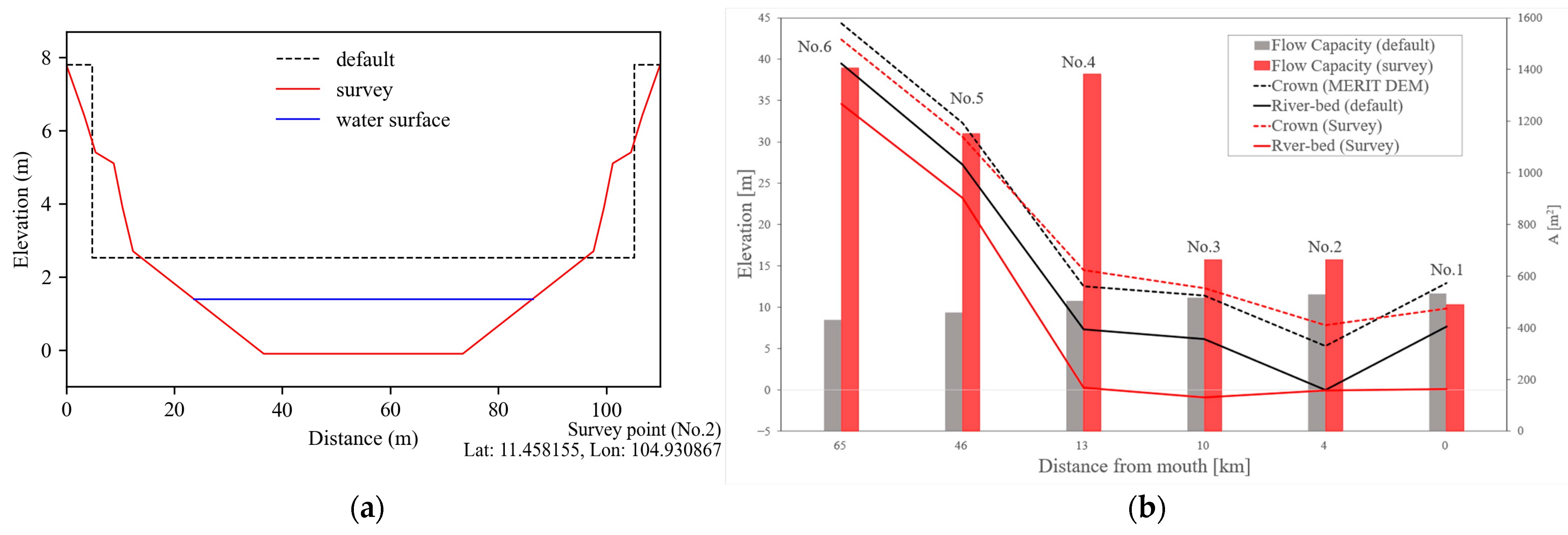

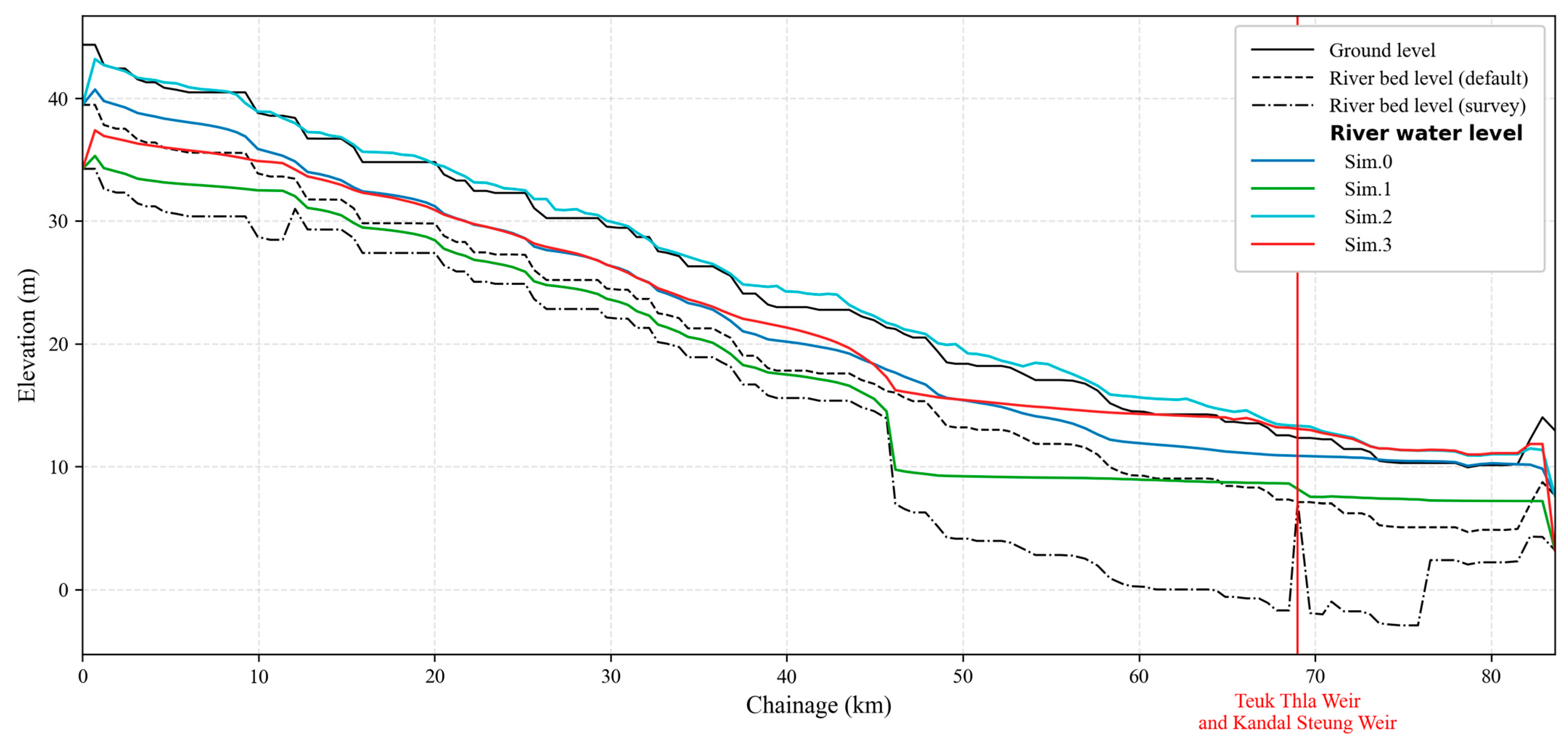

3.3. River Channel Cross-Section

3.4. Hydraulic Infrastructure

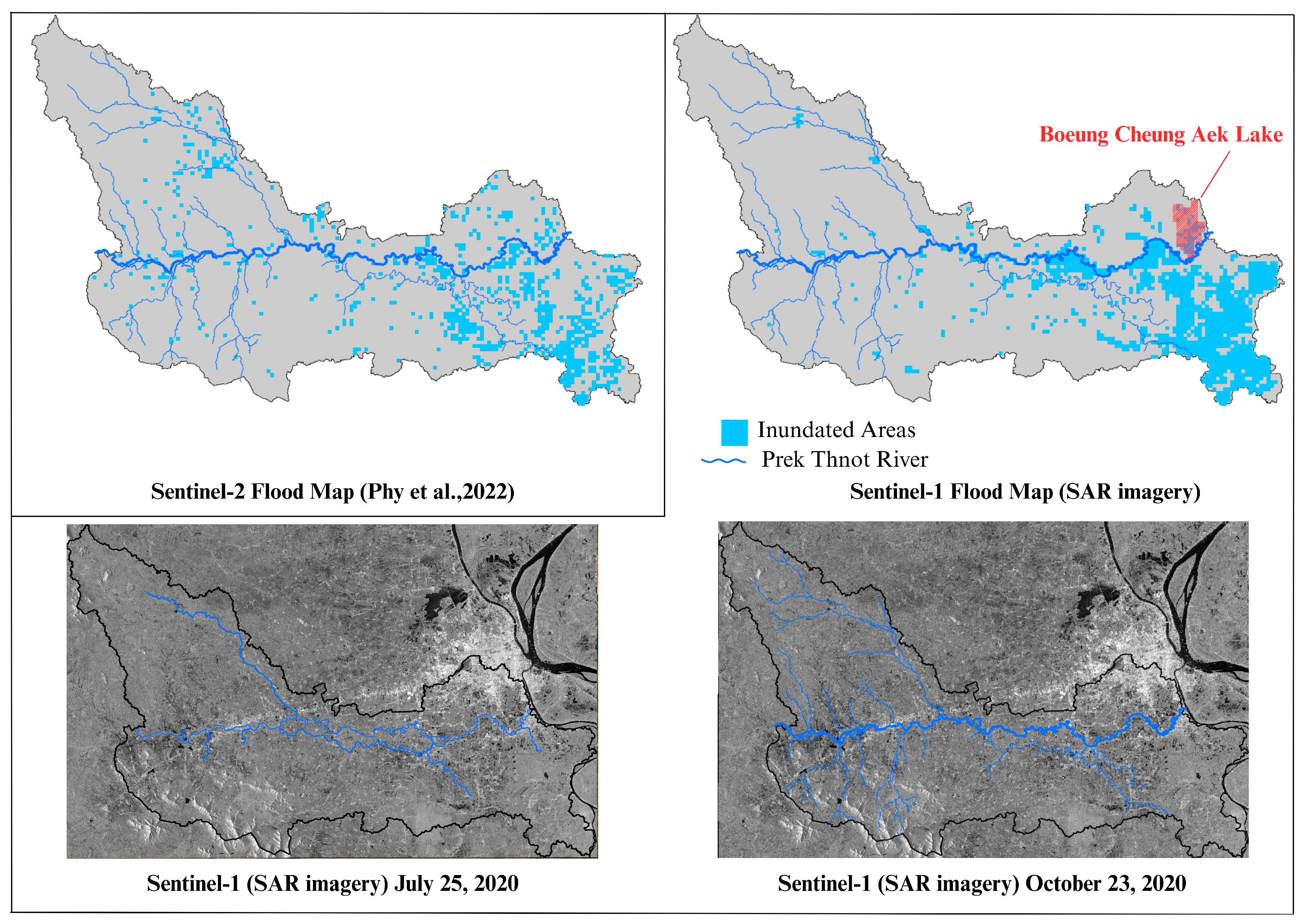

3.5. SAR Imagery

3.6. Data Limitations and Assumptions

4. Results and Discussion

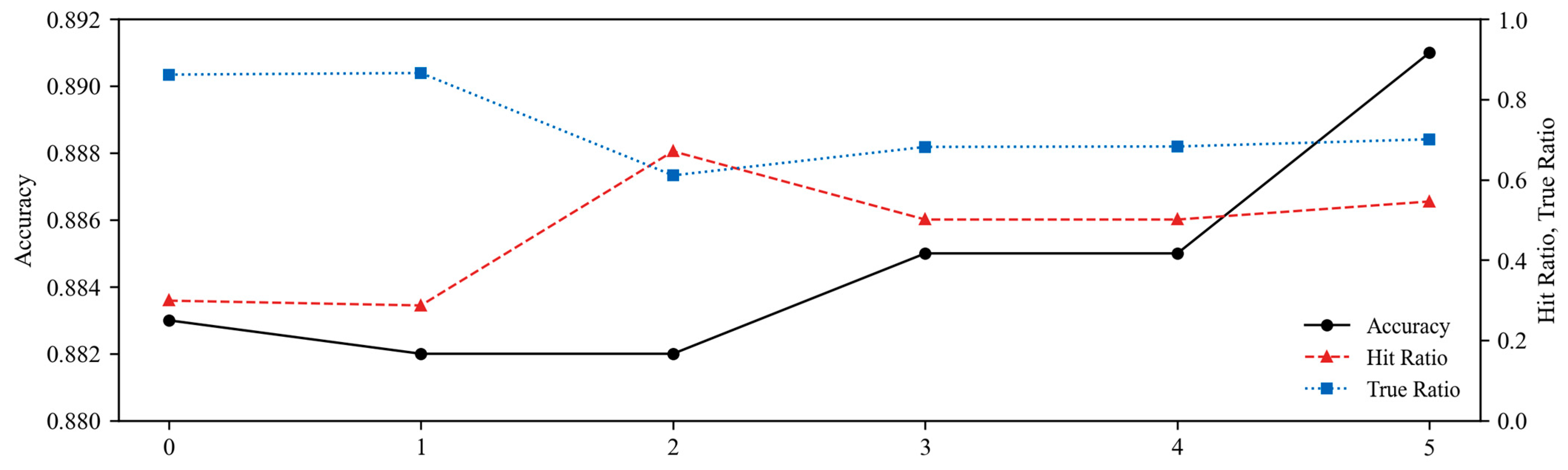

4.1. Overall Performance Across Simulations

4.2. Combined Effects of Channel Geometry and Rainfall Resolution (Sims. 0–3)

4.3. Effect of Land Use Update (Sim. 3 to Sim. 4)

4.4. Effect of Hydraulic Infrastructure (Sim. 4 to Sim. 5)

4.5. Practical Implications, Limitations, and Synthesis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LPTRB | Lower Prek Thnot River Basin |

| MOWRAM | Ministry of Water Resources and Meteorology |

| RRI | Rainfall-Runoff Inundation |

| JICA | Japan International Cooperation Agency |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| DIR | Flow Direction |

| ACC | Flow Accumulation |

| GSMaP | Global Satellite Mapping of Precipitation |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| AC | Accuracy |

| HR | Hit Ratio |

| TR | True Ratio |

| IC | Inundated cells |

| UC | Un-inundated cells |

| TC | Total cells |

References

- UNDRR Human Cost of Disasters. UNDRR. Geneva, CHE. 2000. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/media/48008/download?startDownload=20250715 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 35–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwami, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Miyamoto, M.; Kudo, S.; Yamazaki, Y.; Ushiyama, T.; Koike, T. Comparative study on climate change impact on precipitation and floods in Asian river basins. Hydrol. Res. Lett. 2017, 11, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.B.; Perera, E.D.P.; Kudo, S.; Miyamoto, M.; Yamazaki, Y.; Kuribayashi, D.; Sawano, H.; Sayama, T.; Magome, J.; Hasegawa, A.; et al. Assessing flood disaster impacts in agriculture under climate change in the river basins of Southeast Asia. Nat. Hazard. 2019, 97, 157–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDESA. World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/assets/Files/WPP2019_Highlights.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- ADB. Asian Water Development Outlook 2020: Advancing Water Security Across Asia and the Pacific; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong City, Philippines, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayama, T.; Tatebe, Y.; Iwami, Y.; Tanaka, S. Hydrologic sensitivity of flood runoff and inundation: 2011 Thailand floods in the Chao Phraya River basin. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 15, 1617–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakti, P.C.; Miyamoto, M.; Misumi, R.; Nakamura, Y.; Sriariyawat, A.; Visessri, S.; Kakinuma, D. Assessing flood risk of the Chao Phraya River Basin based on statistical rainfall analysis. J. Disaster Res. 2020, 15, 1025–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamrussri, S.; Toda, Y. Assessing the effectiveness of non-structural flood countermeasures in the upper Chao Phraya River Basin, Thailand. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2017, 10, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koem, C.; Tantanee, S. Flood Disaster Studies: A Review of Remote Sensing Perspective in Cambodia. Geogr. Tech. 2021, 16, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phy, S.R.; Sok, T.; Try, S.; Chan, R.; Uk, S.; Hen, C.; Oeurng, C. Flood Hazard and Management in Cambodia: A Review of Activities, Knowledge Gaps, and Research Direction. Climate 2022, 10, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.J.; Triet, N.V.K.; Hoang, L.P.; Heng, S.; Hok, P.; Chung, S.; Koponen, J.; Kummu, M. The Cambodian Mekong floodplain under future development plans and climate change. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 22, 967–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichet, N.; Kawamura, K.; Trong, D.P.; On, N.V.; Gong, Z.; Lim, J.; Khom, S.; Bunly, C. MODIS-Based Investigation of Flood Areas in Southern Cambodia from 2002–2013. Environments 2019, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Park, E.; Wang, J.; Sophal, T. The changing rainfall patterns drive the growing flood occurrence in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 55, 101945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierolf, L.; Moel, H.D.; Vliet, J.V. Modeling urban development and its exposure to river flood risk in Southeast Asia. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 87, 101620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mialhe, F.; Gunnell, Y.; Navratil, O.; Choi, D.; Sovann, C.; Lejot, J.; Gaudou, B.; Se, B.; Landon, N. Spatial growth of Phnom Penh, Cambodia (1973–2015): Patterns, rates, and socio-ecological consequences. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, T.N.; Thi Thu Trang, N.; Bui, X.T.; Thi Da, C. Remote sensing and GIS for urbanization and flood risk assessment in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 6625–6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L. An economic assessment of urban flooding in Cambodia: A case study of Phnom Penh. Insight Cambodia J. Basic Appl. 2019, 1, 125–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahmakum Teang Tnaut (STT). Poverty Assessment for Urban Poor Communities in Phnom Penh. 2022. Available online: https://teangtnaut.org/en/research/reports/poverty-assessment-for-urban-poor-communities-in-phnom-penh (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Nop, S.; Thornton, A. Urban resilience building in modern development. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 24, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, B.; Fortnam, M. Urbanising Disaster Risk: Vulnerability of the Urban Poor in Cambodia to Flooding and Other Hazards. 2015. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/submissions/47109_urbanisingdisasterriskreportinteractive.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Kudo, S.; Yorozuya, A.; Perera, E.D.P.; Koseki, H.; Iwami, Y.; Nakatsugawa, M. Influence Analysis of Observed River Channel Conditions of Inundation Process in Lower Mekong River Basin. Jpn. J. JSCE 2016, 72, 145–150. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heng, S.; Kheav, K.; Hok, P.; Chhuon, K.; Ly, S.; Kinouchi, T. Urban Flood Modeling in Phnom Penh Using Flo-2D: Consideration of Climate Change Effect. Techno-Sci. Res. J. 2021, 9, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Phy, S.R.; Try, S.; Sok, T.; Ich, I.; Chan, R.; Oeurng, C. Integration of Hydrological and Flood Inundation Models for Assessing Flood Events in the Lower Prek Thnot River Basin under Climate Change. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2022, 27, 05022012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srey, S.; Yaguchi, T. The Peri-Urban Landscape Interface Contribution to Flood Management of The Metropolis, The Case of Phnom Penh. Journal of Architecture Planning. Archit. Inst. Jpn. 2023, 88, 1648–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Climate Change Knowledge Portal. 2024. Available online: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/cambodia (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Ministry of Planning (MOP). Commune Database: 2005–2022; Unpublished Excel Data Set; Ministry of Planning (MOP) Commune Database: Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- OCIC Group. Techo International Airport. OCIC Homepage. 2023. Available online: https://www.ocic.com.kh/projects/techo-international-airport (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Raksmey, H. Techo International Airport: Cambodia’s Emerging Passenger and Cargo Hub. The Phnom Post. 2025. Available online: https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/techo-international-airport-cambodia-s-emerging-passenger-and-cargo-hub (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- The World Bank Cambodia Country Office. Urban Development in Phnom Penh Land Use Policy; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Volume 87, Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/286991511862455372 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Sayama, T.; Ozawa, G.; Kawakami, T.; Nabesaka, S.; Fukami, K. Rainfall-Runoff-Inundation Analysis of the 2010 Pakistan Flood in the Kabul River Basin. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2012, 57, 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakinuma, D. 2022 PWRI New Technology Seminar in Tokyo. PWRI Homepage. 2022. Available online: https://www.pwri.go.jp/jpn/results/tec-info/siryou/seminar/R4/pdf/2022seminar_1555.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025). (In Japanese).

- Yamazaki, D.; Watanabe, S.; Hirabayashi, Y. Global Flood Risk Modeling and Projections of Climate Change Impacts. Geophys. Monogr. Ser. Ch. 2018, 11, 158–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambodia Humanitarian Response Forum. Floods in Cambodia: Situation Report No. 6—Humanitarian Response Forum, As of 26 October 2020. KHM. 2020. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/cambodia/floods-cambodia-situation-report-no-6-humanitarian-response-forum-26-october-2020 (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Kamimera, H.; Thanh, N.D.; Le, V.X.; Matsumoto, J.; Ushio, T.; Iwami, Y. Evaluation of the performance of the satellite precipitation product GSMaP in central Vietnam. In Proceedings of the Japan Society of Hydrology and Water Resources Annual Conference 2014, Miyazaki, Japan, 26 September 2014; Volume 27, p. 100034. (In Japanese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, M.; Application of Corrected GSMaP to flood Forecasting and Warning. JAXA Homepage. 2016. Available online: https://www.eorc.jaxa.jp/event/2016/pdf/06_tsuda.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025). (In Japanese).

- Potapov, P.; Hansen, M.C.; Pickens, A.; Hernandez-Serna, A.; Tyukavina, A.; Turubanova, S.; Zalles, V.; Li, X.; Khan, A.; Stolle, F.; et al. The Global 2000-2020 Land Cover and Land Use Change Dataset Derived from the Landsat Archive: First Results. Front. Remote Sens. 2022, 3, 856903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulder, M.A.; Masek, J.G.; Cohen, W.B.; Loveland, T.R.; Woodcock, C.E. Opening the Archive: How Free Data Has Enabled the Science and Monitoring Promise of Landsat. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 122, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan International Cooperation Agency. The Study on Comprehensive Agricultural Development of Prek Thnot River Basin in The Kingdom of Cambodia; Report; JICA: Tokyo, Japan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Japan International Cooperation Agency. Project for The Comprehensive Flood Management Plan for The Chao Phraya River Basin Final Report Addendum Report: The Flood Analysis on the Chao Phraya River with RRI Model; Report; JICA: Tokyo, Japan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Obata, S.; Shimatani, Y.; Sato, T. Evaluation of Flood Control Function of Irrigation Ponds in The Rokkaku River Watershed. J. Jpn. Soc. Civ. Eng. Ser. B1 2020, 76, 757–762. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iida, Y.; Watanabe, N.; Sato, J.; Koarai, M. Disaster Monitoring using High Resolution SAR. J. Geospat. Inf. Auth. Jpn. 2002, 99, 49–56. Available online: https://gbank.gsj.jp/ld/resource/geolis/200211961 (accessed on 11 June 2024). (In Japanese).

- Quang, N.H.; Tuan, V.A.; Hang, L.T.; Hung, N.M.; The, D.T.; Dieu, T.D.; Anh, N.D.; Hackney, C.R. Hydrological/Hydraulic Modeling-Based Thresholding of Multi SAR Remote Sensing Data for Flood Monitoring in Regions of the Vietnamese Lower Mekong River Basin. Water 2020, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Sayama, T. Impact of climate change on flood inundation in a tropical river basin in Indonesia. Prog. Earth Planet Sci. 2021, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Land Use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Forest | Urban | Water Body | Wetland | Agriculture |

| nriver | 0.03 | ||||

| nslope | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| d | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.40 |

| 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | |

| kv | ― | ― | ― | 1.66 × 10−7 | 1.66 × 10−7 |

| Sf | ― | ― | ― | 0.273 | 0.273 |

| ka | 0.10 | ― | 0.10 | ― | ― |

| ― | ― | 0.05 | ― | ― | |

| Land Use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Forest | Urban | Water Body | Wetland | Agriculture |

| 2002 | 478.3 | 15.5 | 37.8 | 28.5 | 1475.8 |

| 2020 | 337.0 | 345.8 | 36.5 | 54.3 | 1262.3 |

| Data Augmentation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sim. | Cross- Section | Hourly Rainfall | Land-Use | Infrastructure (Weir, Pump) |

| 0 | ||||

| 1 | ◯ | |||

| 2 | ◯ | |||

| 3 | ◯ | ◯ | ||

| 4 | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | |

| 5 | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Sim. | Simulated Area (km2) | Matched Area (km2) | AC | HR | TR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 92.25 | 79.50 | 0.883 | 0.299 | 0.862 |

| 1 | 88.00 | 76.25 | 0.882 | 0.287 | 0.866 |

| 2 | 292.00 | 178.50 | 0.882 | 0.671 | 0.611 |

| 3 | 195.50 | 133.25 | 0.885 | 0.501 | 0.682 |

| 4 | 195.00 | 133.25 | 0.885 | 0.501 | 0.683 |

| 5 | 207.25 | 145.25 | 0.891 | 0.546 | 0.701 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumagae, T.; Nong, M.; Konishi, T.; Amaguchi, H.; Imamura, Y. Enhancing Flood Inundation Simulation Under Rapid Urbanisation and Data Scarcity: The Case of the Lower Prek Thnot River Basin, Cambodia. Water 2025, 17, 3222. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223222

Kumagae T, Nong M, Konishi T, Amaguchi H, Imamura Y. Enhancing Flood Inundation Simulation Under Rapid Urbanisation and Data Scarcity: The Case of the Lower Prek Thnot River Basin, Cambodia. Water. 2025; 17(22):3222. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223222

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumagae, Takuto, Monin Nong, Toru Konishi, Hideo Amaguchi, and Yoshiyuki Imamura. 2025. "Enhancing Flood Inundation Simulation Under Rapid Urbanisation and Data Scarcity: The Case of the Lower Prek Thnot River Basin, Cambodia" Water 17, no. 22: 3222. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223222

APA StyleKumagae, T., Nong, M., Konishi, T., Amaguchi, H., & Imamura, Y. (2025). Enhancing Flood Inundation Simulation Under Rapid Urbanisation and Data Scarcity: The Case of the Lower Prek Thnot River Basin, Cambodia. Water, 17(22), 3222. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223222