1. Introduction

Water inrush disasters are a primary risk to tunnel construction safety [

1]. They occur suddenly and are highly destructive, often leading to significant casualties and economic losses [

2]. With the rapid expansion of infrastructure development in China into geologically complex regions [

3], these disasters are occurring with increasing frequency and escalating severity [

4]. Accurately evaluating the disaster-breeding process of water inrush events has become essential for proactive disaster prevention and control to ensure engineering safety [

5].

Water inrush disasters represent complex dynamic catastrophic phenomena triggered by blasting-induced disturbances in tunnels [

6], which result in drastic changes in the mechanical equilibrium of water-bearing hazardous structures and impermeable mudstone formations [

7]. During the disaster-breeding process, significant variations occur in multiple physical and mechanical parameters such as rock mass displacement, pore water pressure, and stress, as well as in geophysical parameters including resistivity and electromagnetic wave responses [

8]. Current monitoring technologies for water inrush disasters fall into two categories: non-geophysical monitoring and geophysical monitoring methods [

9,

10,

11].

Non-geophysical monitoring primarily involves the measurement of physical and mechanical parameters such as rock mass displacement, pore water pressure, and stress by employing technologies including fiber optic sensing, vibrating wire sensors, and wireless sensor networks. These measurements support the analysis and evaluation of the dynamic evolution of water inrush disasters. Piao proposed a coal mine geological transparency approach based on distributed fiber optic sensing (DFOS) [

12]. By integrating multiple parameters such as strain field, temperature field, and vibration field—through indicators like strain increment ratio and temperature gradient—the method enables dynamic monitoring of rock mass fracturing and aquifer water level changes during mining operations. Hu studied a DFOS-based method for monitoring roof deformation in coal mines. The study proposed and optimized fiber layout and strain measurement techniques, investigated strain transfer characteristics of optical fibers, and provided an experimental basis for the safety monitoring of water inrush disasters in mining roofs [

13]. Pengfei Li employed vibrating wire sensors in the field to monitor parameters such as surrounding rock pressure, primary support concrete stress, steel arch stress, and deep rock mass displacement in tunnels excavated in high-stress and weak surrounding rocks. Their findings revealed the temporal evolution and spatial distribution of mechanical interactions between surrounding rock and supporting structures, with sensitivity ranking: surrounding rock pressure > steel arch stress > concrete stress [

14]. Kumar M. deployed a wireless sensor network in a landslide-prone area of the Western Ghats, India. This network integrated various geological sensors, including piezometers, inclinometers, and rain gauges, to monitor pore water pressure, surface deformation, and rainfall dynamics in real time. Data were transmitted remotely to a monitoring station 300 km away via satellite link, forming a real-time landslide analysis system that provides innovative technical support for disaster monitoring [

15]. Yan Zhigang applied Internet-of-Things (IoT) technologies to deploy smart sensors. He proposed a source identification method for water inrush disasters using maximum or minimum boundary Support Vector Machine (SVM) models, providing a technical solution for monitoring water inrush sources [

16].

Although these technologies offer significant advantages in water inrush monitoring, including strong real-time capability, high data accuracy, and reliable early warning performance, they still present certain limitations. Their effectiveness is strongly influenced by environmental complexity and uncertainty. In high-stress, geologically complex settings, sensor stability and sensitivity may degrade. Furthermore, in extreme environments such as deep-buried tunnels or fault zones, the effectiveness and coverage of sensor data acquisition may be limited. These technologies may also exhibit a certain degree of error in identifying large-scale water inrush sources. Geophysical monitoring methods, through the integration of multi-dimensional physical field responses and the cooperation of multiple techniques, demonstrate superior environmental adaptability and comprehensive detection capabilities. Methods such as the Transient Electromagnetic Method (TEM), Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR), Acoustic Emission (AE), Microseismic Monitoring (MS), and Induced Polarization (IP) are based on physical principles including electromagnetic induction, high-frequency reflection, elastic wave radiation, and electrochemical polarization. These techniques effectively identify water-bearing structures, fractured aquifers, and their evolutionary characteristics during water inrush disasters [

17,

18,

19]. Jun Lin proposed an adaptive high-resolution (AHR) TEM detection method based on pseudo-seismic wavelet transform [

20]. This method improves the accuracy of resistivity imaging in complex urban geological environments and provides early prediction of road collapses and water-related hazards. Subsurface TEM applications in water inrush monitoring have achieved continuous progress. Lu Gaoming developed an innovative signal processing algorithm for ground penetrating radar (GPR). By applying dual-threshold wavelet filtering and wave propagation theory, the algorithm effectively reduces interference from tunnel boring machine (TBM) operations. It substantially enhances radar imaging quality, offering a new solution for water hazard detection in TBM tunnels. Microseismic monitoring and acoustic emission (AE) techniques have also advanced significantly in water inrush monitoring [

21]. Chen Yanhao investigated the disaster-inducing mechanisms of water-conducting channels and proposed a new monitoring and early warning method based on microseismic and AE techniques. This method provided theoretical support for preventing similar geological hazards and for the safe construction of major infrastructure projects [

22]. Gai Qiukai proposed a microseismic-based method for evaluating floor failure characteristics and water inrush risk. Using a weighted coefficient of variation and microseismic energy analysis, the method effectively assessed the risk of water inrush from the tunnel floor [

23]. Nie Lichao applied a fully decayed induced polarization (IP) multi-parameter inversion imaging technique. By integrating cross-gradient constraints with geological interpretation, they achieved high-precision three-dimensional detection of water-bearing structures, which successfully guided the safe crossing of complex water-rich zones in the Gaoligongshan Tunnel and provided a technical model for TBM construction risk control and efficiency improvement [

24]. Kemna A combined induced polarization with borehole observation. Using IP’s sensitivity to groundwater and the qualitative correlation between the imaginary part of complex conductivity and lithological parameters, the study produced images and quantitative interpretations of inter-borehole water-bearing media and hydraulic characteristics [

25].

Among the current geophysical methods for water inrush monitoring, techniques such as Transient Electromagnetic Method (TEM) [

26,

27], Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) [

28], microseismic monitoring, acoustic emission, and Induced Polarization (IP) each offer distinct advantages. These methods can provide early warning information regarding groundwater flow paths, fracture distributions, and potential water sources. Compared with these techniques, the borehole resistivity method demonstrates significant advantages in water inrush monitoring.

The borehole method involves embedding electrodes directly within boreholes, which effectively eliminates the shielding effect of surface overburden on electrical current. The current can propagate vertically downward through the borehole into deeper rock formations. Directional current injection and signal reception with in-hole electrode arrays produce near-field high-density current focusing in the target zone. This configuration reduces interference from surface stray currents and enables detailed characterization of the geometry, scale, and connectivity of local anomalies [

29,

30]. Compared with conventional resistivity methods, borehole resistivity techniques provide greater penetration depth and higher resolution. They can accurately identify groundwater flow paths and source locations, making them particularly suitable for water inrush monitoring in geologically complex environments. Su Maoxin applied a borehole-to-surface resistivity tomography method in a limestone mine in Pingnan, Guangxi. Under complex geological anomaly conditions, hybrid array imaging was used to successfully locate and delineate the water-conducting channel behind the inrush, providing practical guidance for grouting and sealing operations [

31]. Du Liang employed roof borehole resistivity tomography to monitor the spatial and temporal distribution of water seepage above a mining face. By analyzing variations in low-resistivity anomaly zones, they were able to qualitatively assess water content, offering a reliable basis for predicting and providing early warning of roof water inrush events. These applications highlight the advantages of borehole resistivity tomography in monitoring water inrush hazards [

32].

Compared with borehole or surface surveys commonly applied in coal-mining or near-surface settings, tunnel investigations must be carried out under multiple tunnel-face constraints, including near-field conditions, water-saturated and highly conductive media, construction disturbances, and electromagnetic noise from equipment. These factors significantly limit the penetration depth of GPR in conductive formations and make TEM/IP more susceptible to shielding and geometric mismatch caused by linings, metallic components, or irregular tunnel geometry. The borehole resistivity method takes advantage of the fact that the borehole can directly contact or closely approach water-bearing anomalies so that near-field, directional current injection and reception can be achieved inside the hole. In this way, more reliable local electrical information can be acquired, and localized imaging can be performed even under highly conductive and disturbed conditions. For monitoring and early warning of tunnel water and mud inrush, and considering that such hazards essentially arise from the gradual evolution of water-rich unfavorable geological structures, we consider the borehole resistivity method to be better suited to this scenario.

Therefore, taking advantage of borehole resistivity in water inrush monitoring, this study conducted numerical simulation experiments of inversion imaging to monitor the evolution of water-conducting channels ahead of the tunnel face. Given the pronounced staging characteristics of seepage-instability-induced water inrush disasters, the study systematically summarizes four typical stages of the disaster-breeding process. The geological features and corresponding resistivity responses of each stage are identified. Using a borehole resistivity time-lapse evaluation method based on least squares inversion, the study realizes the imaging of the water inrush evolution process. It quantitatively analyzes the spatial distribution patterns of resistivity anomalies at different evolutionary stages of an inclined fault-type water-conducting channel. A whole-process imaging strategy based on resistivity ratio is employed to characterize water-conducting channels of varying degrees of development [

33,

34].

2. Analysis of Resistivity Evolution During Seepage Instability-Induced Water Inrush Hazards

Seepage-instability-induced water inrush is a typical disaster-breeding mechanism in tunnel engineering and frequently occurs in filling-type failure zones. When large fractures, faults, or karst conduits are exposed, the infill material, often the weakest part of the structure, becomes the key factor affecting the overall stability of the rock mass. If the infill has high porosity and permeability, seepage may develop within it under excavation disturbance and high-pressure groundwater conditions. Fine particles within the infill are gradually washed out, leading to the formation of interconnected water-conducting channels. These channels continuously expand and extend, eventually developing into continuous flow paths and causing water and mud inrush disasters [

35,

36,

37].

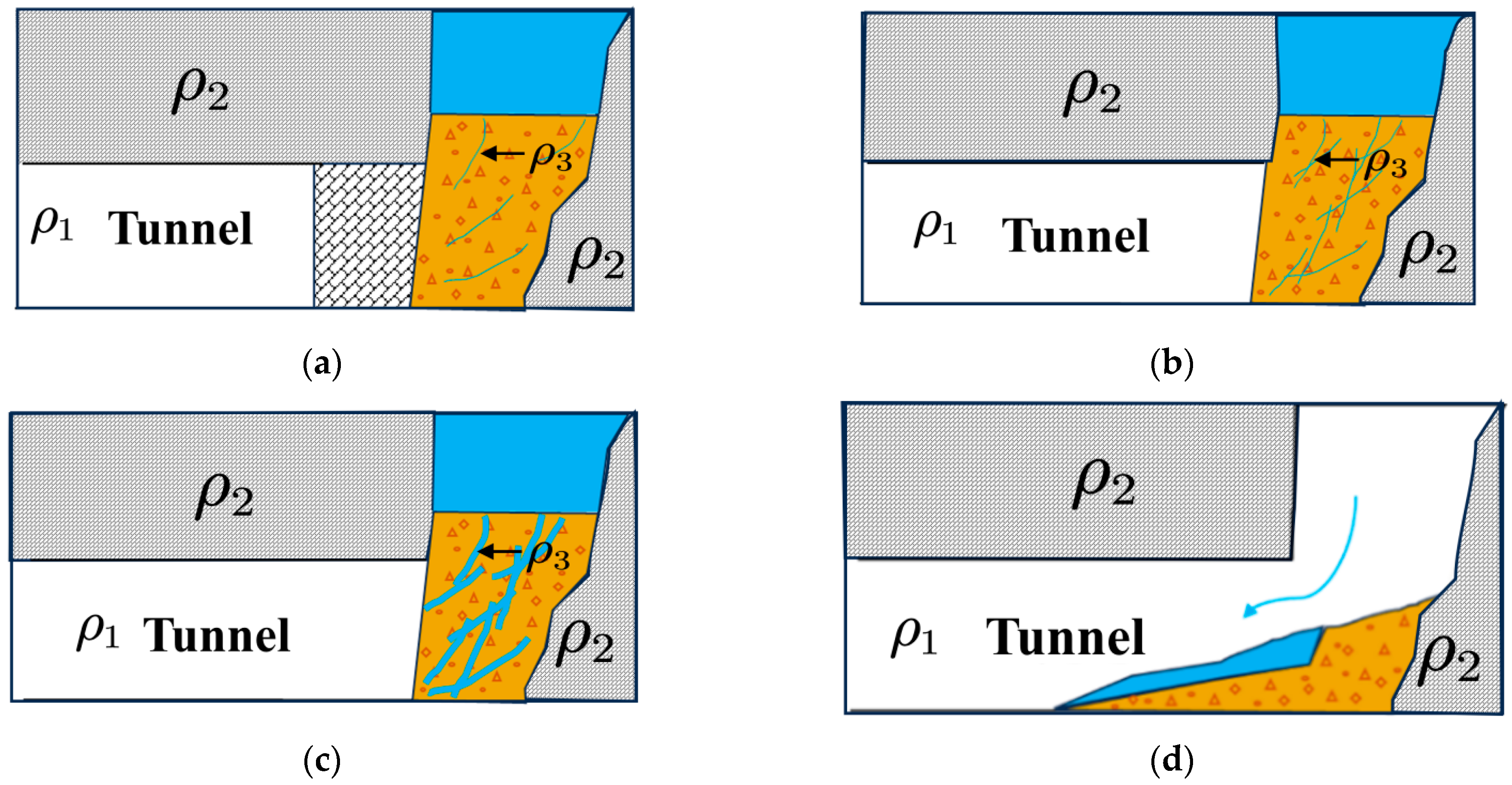

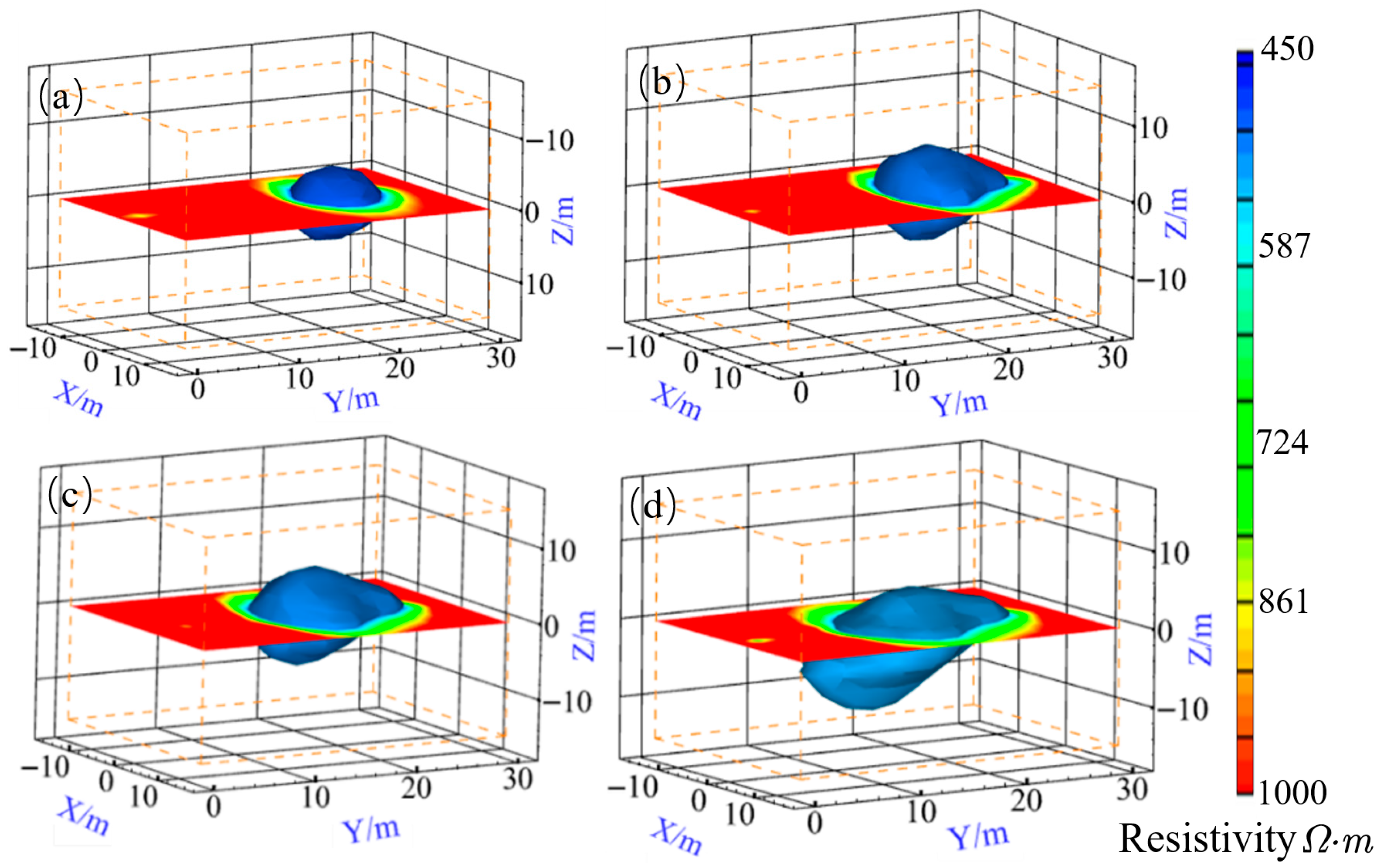

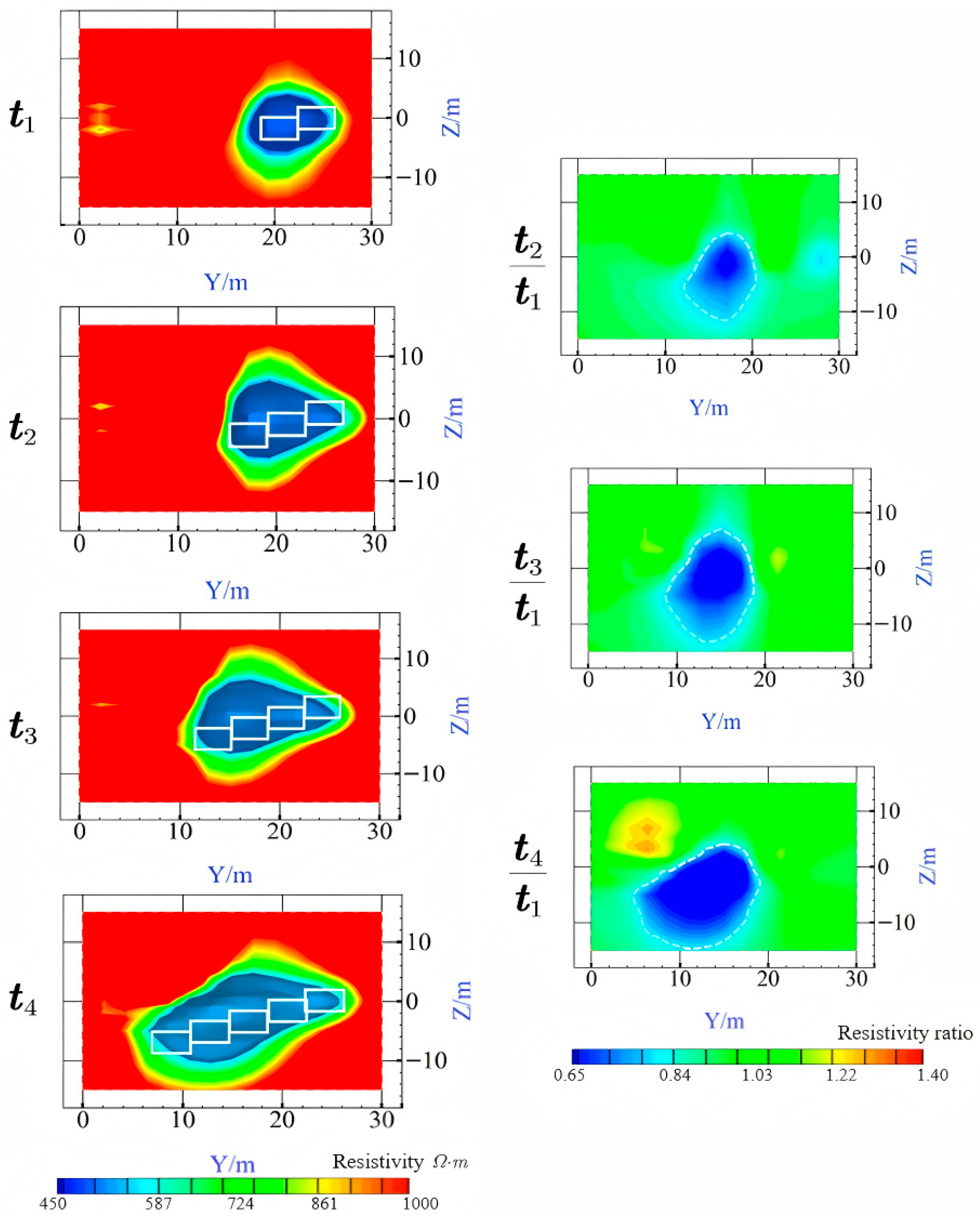

The seepage-instability process leading to tunnel water inrush does not occur instantaneously; rather, it evolves progressively under the combined effects of excavation disturbance and groundwater action. Drawing on existing studies of tunnel and mining water hazards, this evolution can be generalized into four characteristic stages—initial disturbance, fracture connection, channel expansion, and channel penetration—within which the morphology of the water-bearing structure, the degree of seepage connectivity, and the corresponding resistivity responses all exhibit identifiable differences. On this basis, and building upon previous work, this study summarizes the geoelectrical characteristics of these four stages and constructs the corresponding simplified geoelectrical models to support the subsequent borehole resistivity simulations and imaging analyses (

Figure 1).

Based on previous studies conducted by researchers in China and abroad, this study preliminarily analyzes the evolutionary stages of such disasters. To facilitate the investigation of the general characteristics of different stages using borehole resistivity imaging, four simplified geoelectrical models are proposed (

Figure 1). These models represent the resistivity values of the tunnel (

), surrounding rock (

), and anomalous water-bearing body (

), respectively, respectively, with the condition that

.

Taking the karst conduit in a filling-type hazardous structure as an example, this study analyzes the typical stages of the disaster evolution process of seepage-instability-induced water inrush in tunnels. Compared with other hazardous structures such as faults and karst caves, filling-type karst conduits generally exhibit smaller development scales, more irregular geometries, and stronger suddenness in triggering water inrush disasters. These characteristics pose greater threats to tunnel construction safety, and the underlying mechanism of water inrush is considered representative.

The first stage is the initial disturbance stage (

Figure 1a). Construction activities induce stress release in the surrounding rock of the tunnel, leading to stress redistribution. Microcracks within the infill of the karst conduit, which were initially relatively closed, begin to expand and form a limited number of connected fractures. The opening of local fractures allows water molecules to start infiltrating the fissures. During this stage, water gradually seeps into the rock mass through small fracture channels, resulting in minor water inflow within the tunnel.

The second stage is the fracture connection stage (

Figure 1b). When the karst conduit connects with an underground water-bearing structure or receives increased water recharge, the permeability of the rock mass and infill material changes significantly. During this stage, groundwater infiltrates the infill, leading to its gradual liquefaction. Continuous scouring by groundwater causes fine particles within the infill to be eroded and transported. As a result, the initial fractures expand, and previously isolated microcracks gradually interconnect to form relatively stable seepage pathways. Dripping water may appear within the tunnel at this stage.

The third stage is the expansion and extension of the water-conducting channel (

Figure 1c). Once a stable seepage path is formed, the permeability of the infill further increases, and fracture propagation accelerates. Both the velocity and discharge of groundwater gradually increase. Under continuous seepage action, larger particles within the infill begin to be eroded and transported, leading to further reduction in the structural stability of the filling body. As the water-conducting channel continuously expands and extends, the volume of water inflow into the tunnel increases. With the ongoing loss of granular infill material, the discharged water becomes increasingly turbid.

The fourth stage is the penetration of the water-conducting channel (

Figure 1d). As larger particles within the infill are continuously eroded, the porosity inside the conduit increases. When the channel expands to a critical scale, seepage instability reaches a threshold, and localized failure may occur at any time. The infill undergoes structural collapse due to seepage-induced instability, resulting in rapid groundwater migration. The hydraulic impact further destabilizes the surrounding rock mass. Eventually, the water-conducting channel fully penetrates, forming a continuous flow path that leads to a water and mud inrush disaster. At this stage, most of the granular infill material has been washed out, and the outflow water gradually changes from turbid to clear.

In summary, seepage-instability-induced water inrush in filling-type karst conduits occurs under the combined effects of tunnel excavation disturbance and high-pressure groundwater seepage. The evolution of this disaster can be divided into four stages: the initial disturbance stage, the fracture connection stage, the expansion and extension stage of the water-conducting channel, and the final penetration stage forming a continuous inrush path. In the initial disturbance stage, the surrounding rock is predominantly intact, with low porosity and dry conditions. Due to the inherently high resistivity of the rock mass, the overall electrical resistivity remains high. However, local water infiltration into microcracks slightly increases conductivity, leading to isolated low-resistivity anomalies in a limited area behind the tunnel face. In the fracture connection stage, as the fracture network develops, the resistivity of the surrounding rock decreases. Directional conductive paths begin to form, and low-resistivity strips and channels become apparent. In the expansion and extension stage, with increasing porosity and continuous particle loss, the resistivity of the surrounding rock continues to decline. The main water-conducting channel shows a significant reduction in resistivity, and surrounding areas are also affected, resulting in a broader zone of resistivity decline. In the final penetration stage, as the granular infill material is nearly completely eroded and the water flow becomes clear, the resistivity of the surrounding rock drops sharply. A continuous low-resistivity body is formed, indicating the complete establishment of a hydraulically connected inrush pathway.

The disaster-breeding process of water inrush is a progressive accumulation process involving the interaction of multiple factors, including fracture propagation, migration of fine particles, increased permeability, and the buildup of fracture water pressure. As the geotechnical body undergoes deformation and failure under external loads, its geophysical field characteristics change accordingly, particularly electrical resistivity. These resistivity changes are influenced by factors such as contact area between fine particles, porosity, and water content. Under external loading, fracture propagation leads to the separation of solid particles, which alters the electrical conductivity of the rock mass. When the expanded fractures become saturated with water, the conductivity of the water, being higher than that of rock particles, further modifies the overall conductivity of the rock, resulting in a change in resistivity. These electrical variations provide a crucial basis for the monitoring and evaluation of the dynamic development of water-conducting channels.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Inversion Method

Various geophysical techniques have been employed to detect water-bearing anomalies in subsurface environments, including transient electromagnetic methods (TEM), induced polarization (IP), ground-penetrating radar (GPR), and microseismic monitoring (MS). TEM and IP are effective for detecting conductive or chargeable features at depth, while GPR provides high-resolution imaging in shallow, dry conditions. However, these methods often face limitations in tunnel environments due to strong conductivity contrasts, limited accessibility, and the need for localized, high-resolution monitoring. In contrast, borehole resistivity imaging offers direct, high-sensitivity detection of near-tunnel anomalies and has potential for dynamic monitoring of seepage-instability processes.

While traditional resistivity inversion methods have been widely applied in geological investigations, their resolution and adaptability to complex tunnel conditions remain limited, especially for evolving hazards such as water inrush. To address this challenge, this study adopts a dynamic borehole resistivity imaging approach integrated with a least-squares inversion algorithm [

38,

39]. Building upon prior work, we introduce a time-lapse resistivity ratio method tailored to characterize the staged evolution of inclined water-conducting pathways. This approach aims to enhance the resolution, localization, and interpretability of monitoring data under complex geologic and hydrologic conditions.

The least squares method is a classical mathematical optimization technique aimed at minimizing the discrepancy between observed data and model-calculated values. In the inversion process, this method is used to reduce the error in resistivity data in order to extract the electrical characteristics of subsurface water bodies, thereby enabling accurate inference of the distribution and evolution of water inrush channels. Specifically, the inversion model is optimized using the least squares approach to minimize the difference between simulated and measured data. This process improves the accuracy of the inversion results and effectively mitigates errors commonly encountered in traditional resistivity methods, facilitating more precise analysis of the electrical properties of groundwater.

Therefore, this study proposes a dynamic inversion method based on borehole resistivity, integrated with least squares inversion techniques. This method enables accurate inversion of the electrical properties of subsurface water bodies under complex geological conditions. It allows for the identification of the expansion process of water-conducting channels and the real-time tracking of the location and evolution of water inrush anomalies. In this study, the smoothed least squares inversion method is employed to obtain borehole resistivity parameters. The corresponding algorithm is described as follows:

In Equation (1), represents the difference between the measured and predicted data in the borehole resistivity method, is the Jacobian matrix, which characterizes the sensitivity of the observed data to changes in model parameters, is the smoothness matrix, The smoothness constraint ensures that the variation in model parameters between adjacent grid cells transitions smoothly, and denotes the model update vector used for iteratively refining the model parameters, denotes the Lagrange multiplier, which determines the weighting of the model regularization term.

By applying Equation (2), the model resistivity increment

for each inversion iteration can be obtained, which is then used to calculate the updated model parameter

for the next iteration.

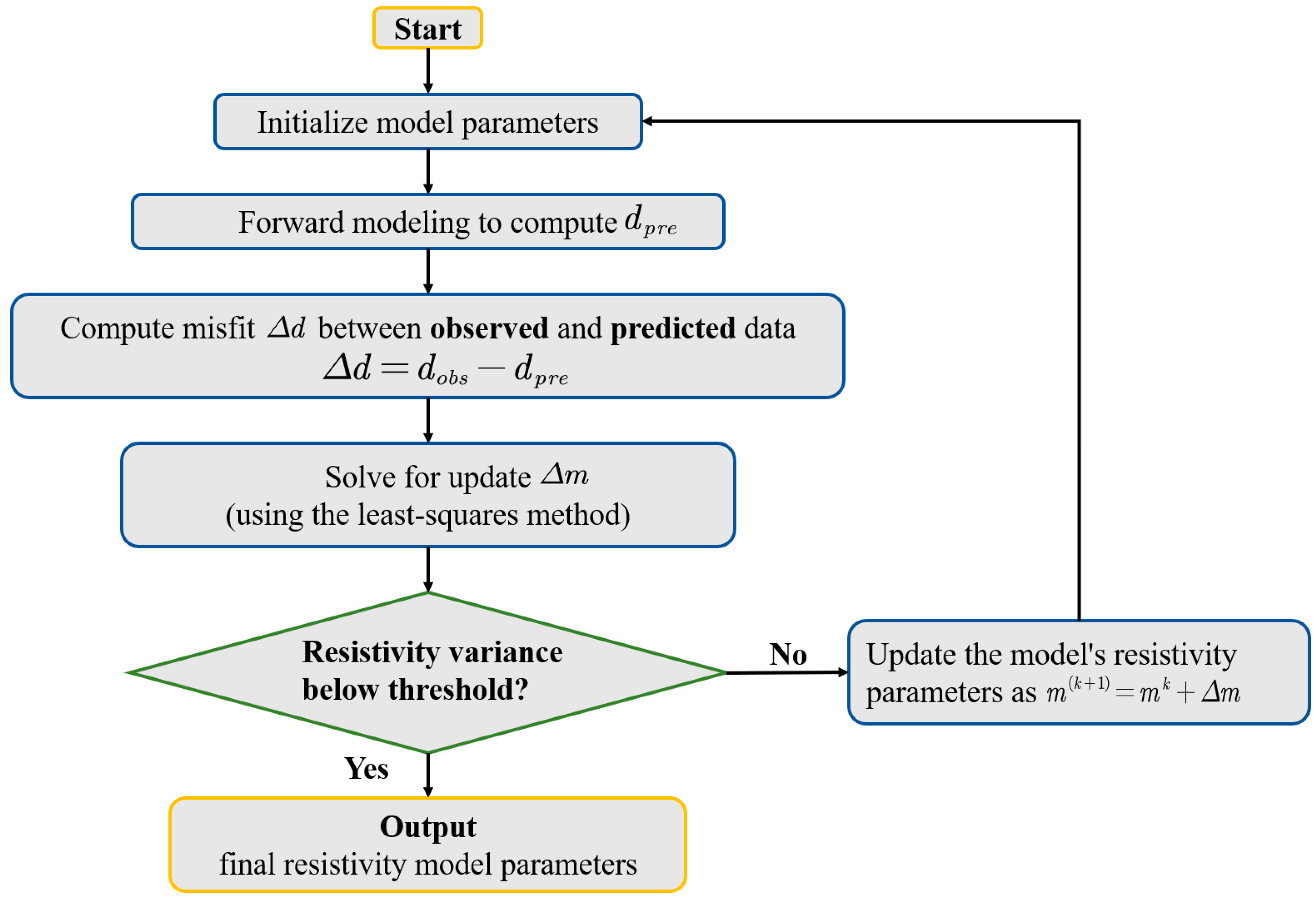

The overall workflow of the smoothed least-squares inversion is summarized in

Figure 2, highlighting the iterative procedure from initial model setup to final convergence.

Equations (1) and (2) and the workflow in

Figure 2 were implemented in a custom Fortran-90 code. The linearized subproblem is solved using a Jacobian-preconditioned conjugate-gradient (PCG/JPCG) algorithm. The convergence criterion adopted in this study requires that the relative residual be smaller than the specified threshold, i.e.,

; by default,

, and the maximum number of iterations is set to 6000.

For the monitoring scenario addressed by the inversion method in this study, a temporal dimension is introduced based on traditional geophysical exploration techniques, transforming the process from a single measurement approach into a multi-temporal measurement strategy. This shift in methodology is characterized by conducting repeated measurements at different time intervals while maintaining the same observation configuration and measurement location, as excavation progresses. The key aspect of this approach lies in the progressive update of subsurface electrical properties through time-dependent inversion computations. Unlike conventional geophysical methods, which typically rely on a single measurement and corresponding inversion analysis, the incorporation of the time dimension allows for continuous monitoring. By repeatedly measuring and inverting data at successive time points, the temporal evolution of the subsurface electrical response is captured, forming a continuous dataset. Based on borehole resistivity inversion, the final model parameter

values obtained at multiple time points are used to calculate the ratio of model parameters between different time intervals. The resistivity ratio is defined as:

where

denotes the resistivity model obtained at monitoring time step

, and

represents the reference resistivity model at baseline time step

. This ratio quantifies the relative change in model parameters at time

with respect to the reference state

, thereby capturing the temporal evolution of borehole resistivity parameters associated with the water-conducting channel. Through this ratio-based formulation, the dynamic changes in the electrical properties of the channel over successive time intervals can be effectively characterized.

3.2. Observation Setup and Geoelectrical Parameter Configuration

After establishing the borehole resistivity inversion method based on the least squares approach and introducing the concept of time-varying model parameter ratios, obtaining high-density and multi-dimensional measured data becomes a critical issue for supporting practical algorithm implementation. Traditional two-dimensional resistivity observation systems are limited in spatial resolution and data volume, making it challenging to meet the refined imaging requirements of multi-directional water-conducting channels under complex geological conditions. To further improve inversion accuracy and expand the applicability of the method, this study proposes an integrated resistivity observation approach that combines borehole resistivity with a three-dimensional electrode network layout. By integrating electrode arrays installed in both boreholes and the tunnel face, a significant breakthrough is achieved in spatial coverage, forming a three-dimensional resistivity detection field that encompasses the area ahead of the tunnel and the surrounding rock. This configuration enables real-time detection of electrical response differences associated with the evolving water-conducting channels during tunnel excavation. The high-density data acquisition capability and comprehensive spatial coverage of this system provide a robust foundation for dynamic inversion and make time-series-based analysis of model parameter ratios feasible. Based on this system, the following section constructs a representative inclined water-conducting channel model and quantitatively analyzes the anomalous electrical response characteristics at different evolutionary stages.

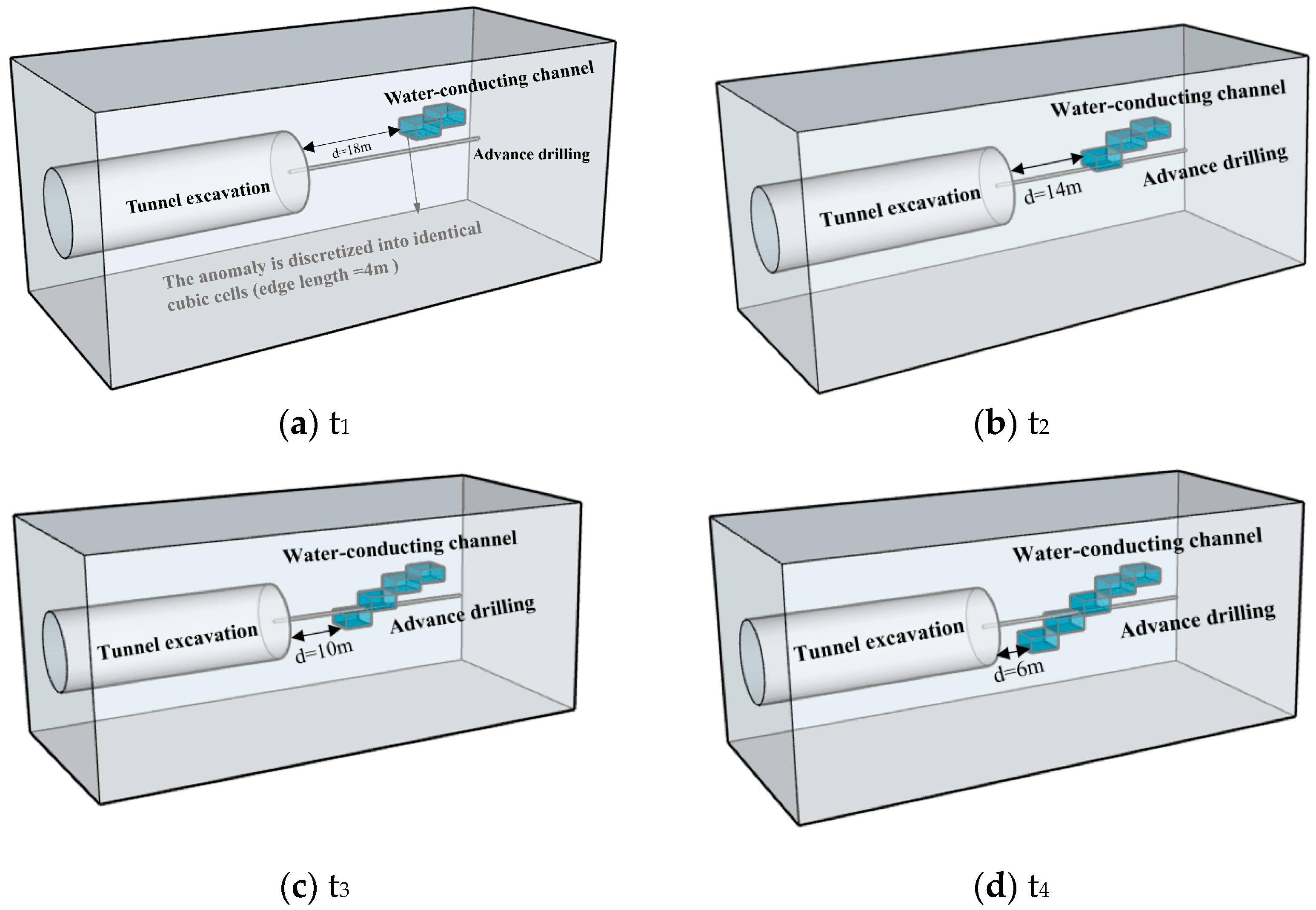

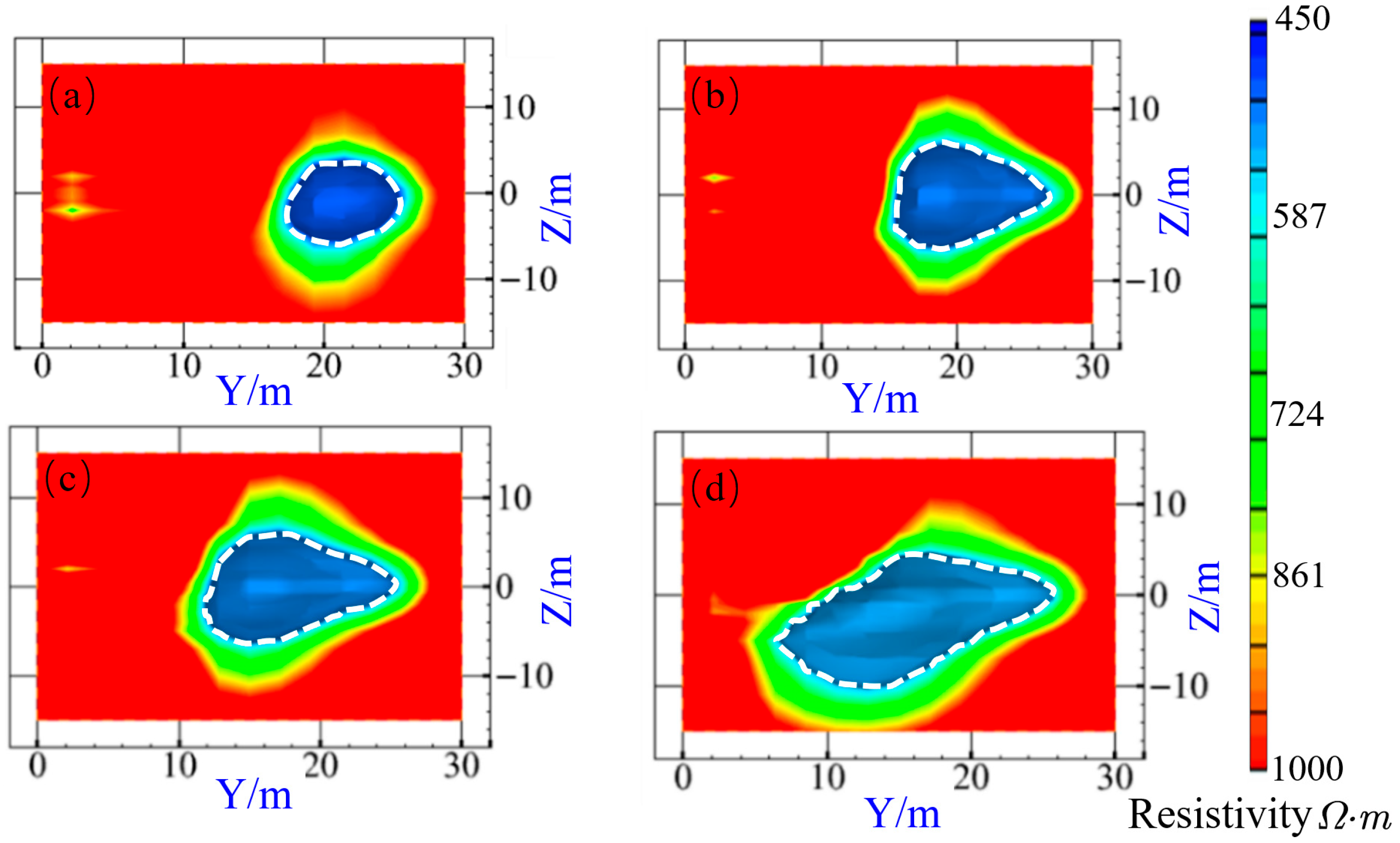

To achieve high-resolution inversion imaging of water-conducting channels in various orientations, a borehole–tunnel face integrated resistivity observation system was employed (

Figure 3). This system combines a three-dimensional electrode network with borehole resistivity acquisition, thereby overcoming the limitations of traditional two-dimensional surveys and enabling comprehensive data collection. As illustrated in

Figure 3a, the 3D observation system consists of power-supply electrodes installed inside the borehole and measurement electrodes distributed on the tunnel face.

Balancing depth of investigation, vertical resolution, and computational efficiency, we set the vertical spacing of the borehole electrodes to 2 m [

25]. This spacing provides an effective near-face imaging resolution on the order of the electrode spacing while keeping the inversion mesh size and computational burden manageable. Consequently, the configuration achieves the required depth coverage and yields resolvable responses for typical low- and high-resistivity anomalies ahead of the tunnel face. The tunnel face covers an area of

. A total of 15 current electrodes are installed in the boreholes, spaced at 2 m intervals. On the tunnel face, three measurement lines are arranged vertically, each with nine measurement points, yielding a total of 27 measurement electrodes (

Figure 3b). The inversion domain is set to

. Using this borehole resistivity configuration, a total of 12,150 observation data points are acquired. Based on this observation system, a water-conducting channel model with an inclined orientation was constructed. Although water inrush may occur along various orientations, previous studies have shown that inclined channels are the most representative and hazardous form [

33,

34,

40], as they commonly develop along fractured zones and exert dominant control on groundwater migration during seepage-induced failure. Therefore, only inclined channel models were considered in this study. The model parameters are uniformly set as follows: the resistivity of the tunnel cavity (

) is

, the resistivity of the surrounding rock (

) is

, and the resistivity of the water-conducting channel is (

)

. These settings are used to analyze the borehole resistivity response characteristics at different evolutionary stages.

5. Discussion

The borehole resistivity method can provide valuable electrical information for monitoring tunnel water inrush, but its imaging accuracy is still constrained by several factors. First, the achievable resolution is limited by electrode spacing and current penetration capability. When fine fractures or small-scale water-conducting features at depth need to be delineated, insufficient current energy in deeper zones may result in inadequate imaging detail. Second, water-conducting channels are often accompanied by complex fracture networks; in highly conductive environments the injected current tends to diffuse, making it difficult to distinguish flow direction, fracture orientation, and medium anisotropy, and thereby reducing the geometric resolution under complex hydrogeological conditions. In addition, tunnel-surrounding rock commonly exhibits strong heterogeneity and well-developed fractured zones, which increases the likelihood of misinterpreting non-conductive structures as water-conducting channels. During long-term monitoring, electrode polarization, corrosion, and aging may further cause signal attenuation, so maintenance or replacement of electrodes is required to keep data quality stable.

For the identification of inclined water-conducting channels immediately ahead of the tunnel face, the borehole resistivity imaging adopted in this study can directly characterize electrical connectivity. Relying on the fact that boreholes can directly contact or closely approach water-bearing anomalies, they can still maintain strong localizing capability and stage-resolved time-lapse characterization under water-saturated, highly conductive, and near-field directional current-injection/reception conditions. By contrast, TEM/IP is more advantageous for regional volumetric coverage or chargeability parameters, GPR provides high resolution in the shallow subsurface, DTS can detect temperature variations induced by flow or seepage in real time, and MS is more sensitive to mechanical precursors. Based on the complementary strengths of these techniques, a face-oriented tiered monitoring workflow can be constructed: far-field preliminary screening is first performed by TEM/IP or MS; DTS is then used to identify active seepage segments; and finally, borehole resistivity is triggered for targeted in-hole densification and time-lapse updating ahead of the tunnel face, so as to improve the localization and early-warning efficiency under a limited number of boreholes.

With respect to time-lapse imaging strategies, three commonly used representations can be adopted for the tunnel-face scenario: the ratio method, the difference-imaging method, and the change-rate method. The ratio method normalizes inversion results from all observation epochs to a common reference epoch, thereby highlighting relative amplitude variations at the same spatial location over time; it is suitable for detecting early-stage low-resistivity anomalies whose absolute resistivity change is not yet pronounced. The difference-imaging method directly yields the absolute increase or decrease in electrical properties between epochs and is therefore convenient for comparison with design baselines, historical observations, or engineering thresholds derived from processing; it is better suited to cases with good baseline quality and to stage-by-stage performance evaluation or grouting verification. The change-rate method emphasizes the speed and abruptness of change and is more sensitive to rapid responses caused by short-term increases in water pressure, seepage enhancement, or excavation-induced disturbances; it is therefore applicable to monitoring scenarios with higher sampling frequency or near-real-time data transmission. In practical engineering, these three strategies are not mutually exclusive and can be combined according to the principle of “using the ratio for background identification, the difference for engineering quantification, and the change rate for rapid warning”. First, the ratio method is used to screen low-resistivity zones that continue to strengthen over time; then, the difference-imaging method is applied to quantify the magnitude and spatial extent of the electrical changes; and finally, the change-rate method is activated for key periods and locations to enable rapid discrimination and early warning of sudden or accelerated evolution.

It should be emphasized that the medium and electrode conditions assumed in numerical simulations are generally more favorable than those in the field, so monitoring and imaging performance in real tunnel projects may deviate from the simulated results, mainly due to the heterogeneity of the surrounding rock and the uncontrollable electrode–formation contact. To mitigate these effects, two aspects should be prioritized in field applications. First, for lithological investigation and parameter specification, surveys of rock lithology, fracture development, and water-bearing conditions should be conducted prior to construction or monitoring; combined with tunnel-face mapping, geological prediction, and experience from similar tunnels, key parameters such as background resistivity and electrical contrast of water-bearing structures should be reasonably defined and zoned so as to reduce, at the source, the systematic bias in inversion results caused by heterogeneous media. Second, for electrode–formation contact control, during drilling, electrode installation, and data acquisition, good contact between the electrodes and the borehole wall (or grouting medium/water) should be ensured; measures such as hole cleaning, supplementary grouting, and contact-resistance testing can be adopted to improve the signal-to-noise ratio and reduce observation errors induced by poor contact, polarization, or corrosion. Through these two levels of field constraints, the gap between the simulation conditions and actual tunnel environments can be narrowed to a certain extent, thereby enhancing the stability of borehole resistivity imaging and the reliability of its interpretation.