Abstract

Effective investments in rural irrigation infrastructure are critical for sustainable agricultural development and rural revitalization. This study investigates how social capital influences farmers’ investment in public infrastructure in terms of management and maintenance of irrigation facilities in rural Xinjiang, China. By using field survey data from 700 farmers in southern Xinjiang, we distinguished traditional social capital from newly emerged social capital (accumulated aid assigned to Xinjiang governors by upper authorities) and found that (1) both social capitals significantly facilitate farmers’ investment in managing and maintaining irrigation maintenance, particularly the latter; (2) the main influencing mechanism is twofold, directly promoting irrigation investments and indirectly stimulating participation in non-agricultural employment. These findings suggest that policy interventions should simultaneously strengthen rural social networks and improve non-agricultural employment services to foster collective action in investing in public irrigation system management and maintenance.

1. Introduction

The 20th CPC National Congress emphasized the need to comprehensively promote rural revitalization, prioritize agricultural and rural development, facilitate the flow of urban and rural factors, and maintain the red line of 120 million hectares of arable land. The flow of factors, especially labor and land, is a critical issue in the rural revitalization strategy. Water resources are particularly vital in the arid regions of Northwest China, serving as a key element for sustaining the red line of arable land. General Secretary Xi Jinping has stressed the importance of water security and the need to enhance awareness of the water crisis, addressing it from the strategic perspective of building a well-off society and ensuring the sustainable development of China. In Xinjiang, irrigation water is essential for agricultural production. Xinjiang’s development heavily depends on the availability and efficient use of water resources. Within the broader framework of rural revitalization, farmers’ involvement in irrigation infrastructure investment is integral to both capital investment and water resource utilization, making it a significant agricultural issue.

Effective governance of rural public affairs is a core focus of agricultural and rural modernization within China’s rural revitalization strategy. Improving collective action in the provision of rural public goods at the grassroots level is critical for strengthening the rural governance system [1]. Social capital, as a relational resource consisting of trust, norms, and networks, plays a pivotal role in this aspect by strengthening relationships among stakeholders in irrigation water allocation [2]. The public irrigation system is a key rural public good, typically funded by the government at the initial stage due to its large-scale investment and unclear property rights. However, the maintenance of these systems largely relies on farmer cooperation. The collective irrigation system is characterized by non-excludability of benefits and non-competitiveness in use, making farmers’ cooperation as a form of collective action crucial in this aspect [3]. However, since the nationwide rural tax and fee reform, the abolition of the rural “two labor” system and the introduction of the “one case, one discussion” funding model have presented challenges to collective actions such as the maintenance and construction of farmland irrigation facilities [4]. Furthermore, issues such as land fragmentation [5], free-rider behavior, and differences in preferences among collective members [6] exacerbate these challenges. At the micro-level, understanding the logic of farmers’ collective action in providing public goods—specifically, farmers’ participation in the cooperative management and maintenance of public irrigation systems—is crucial for the sustainable utilization of rural water and soil resources and for safeguarding food security.

Previous studies have demonstrated that social capital, rooted in trust, reputation, and interaction, plays an essential role in facilitating collective action for public good provision [7]. Social networks enable face-to-face communication and foster cooperation through reputational mechanisms [8], while trust encourages individuals to engage in collective action even in the face of potential defaults by others [9]. In communities with abundant social capital, members are more likely to participate actively in collective affairs [10]. Existing research increasingly emphasizes the importance of social capital in promoting the provision of public goods. For example, Sanditov and Arora (2016) demonstrated through mathematical modeling that social networks are crucial in facilitating public good provision [11]. Empirical studies by Cai et al. (2016) confirmed that social capital significantly enhances farmers’ willingness and level of participation in maintaining small-scale irrigation facilities [12]. However, Guo (2017) found that in villages with low social capital, the lack of collective norms and sanctions hinders the maintenance and management of village-level irrigation systems [3].

It is evident that in rural China, where kinship and geographical ties are often complex, understanding how farmers leverage social capital—such as interpersonal relationships—to cooperate in the provision of public goods like irrigation systems is critical. While existing research has highlighted the role of social capital in fostering farmers’ collaborative investment in irrigation, much of current analysis has focused on willingness to invest, and only a few studies pay attention to actual farmers’ investment behaviors. Furthermore, the concept of social capital refers more to the traditional forms, such as kinship and proximity. Indeed, there are new forms of social capital stemming mainly from government intervention. For instance, the role of social capital generated by “Visit, Benefit, and Unite” work teams embedded within rural communities deserves greater attention. The influence of such forms of newly emerged social capitals plays an essential role in influencing rural farmers’ agricultural behaviors. This analysis attempts to examine how both new and traditional forms of social capital shape farmers’ participation in collective conservation and investment in irrigation infrastructure, focusing particularly in the mechanisms through which both types of social capitals influence the collective action among small farmers in participation in the investment in public irrigation investment in irrigation infrastructure management and maintenance. The data used is from the field survey data in Awati County, located in the arid and semi-arid regions of southern Xinjiang.

The remaining parts of this paper are constructed as follows. Section 2 introduces the theoretical analysis on the links between social capital and farmers’ investment in irrigation infrastructure management and maintenance and generates the theoretical proposals. Section 3 introduces the research site and the dataset. Section 4 states the methodological framework. Section 5 presents the empirical results and their analysis, followed by a conclusion and discussion on the policy implications. This study pursues three interrelated objectives: (1) to evaluate farmers’ investment behavior in farmland irrigation facilities and identify the key socio-economic and institutional factors shaping such investments; (2) to assess the influence of social capital and policy recognition on promoting investment and technological adoption; and (3) to provide robust empirical evidence to inform policy measures aimed at enhancing and accelerating irrigation infrastructure investment.

2. Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Traditional Social Capital and Farmers’ Investment in Public Irrigation Infrastructures

Rural China is characterized by a relationship-based society, predominantly shaped by kinship and geographical ties. In this context, the social networks within traditional social capital are particularly critical for farmers’ production and livelihood decisions. On one hand, these social networks facilitate the dissemination of investment information related to farmland irrigation, thereby enhancing farmers’ awareness of the benefits associated with irrigation facility investments and shifting their attitudes towards participating in collaborative management and maintenance [11]. On the other hand, the idea that individuals care more is embedded within these networks and can connect farmers with different social ties, thus creating potential mechanisms for supervision and restraint, consequently supporting the implementation of collective norms in public good supply [13]. This implies that the social capital can increase the likelihood of farmers’ participation in collective investments for the management and maintenance of irrigation facilities. Furthermore, reciprocal social capital promotes mutual assistance among farmers, both financially and in terms of labor, positively influencing collective investment behavior. Therefore, we propose the first theoretical hypothesis that traditional social capital has a positive impact on farmers’ participation in the management and maintenance of farmland irrigation facilities.

2.2. Newly Emerged Social Capital and Farmers’ Investment in Public Irrigation Infrastructure

From the launch of the Fang Hui Ju (“Visit, Benefit, and Gather”) village-stay program in Xinjiang in 2014 to 2021, more than 500,000 Party members and government officials were dispatched to over 10,000 villages. Their mission encompassed poverty alleviation, consolidation of poverty reduction achievements, and the advancement of rural revitalization through practical, problem-solving initiatives for local communities. The social capital generated through village-based cadres, the “Ethnic Unity as One Family” initiative, and the appointment of First Secretaries differs from traditional forms of social capital. In this study, such social capital is characterized by variables including participation in major village management meetings; frequency of attending Fang Hui Ju non-agricultural training sessions; engagement in “pairing-up” (jieqin, or kinship-bonding) activities; level of trust in stationed village cadres; familiarity with social organizations; presence of relatives or friends employed in government or village committees; the degree of importance attached to village regulations; and the extent to which individuals feel their rights are exercised when expressing opinions on village governance.

These new relationships directly or indirectly improve farmers’ living standards, expanding their social networks and accumulating more social capital [14]. Through initiatives such as “cadres’ residence in villages”, “ethnic unity as one big family”, and “paired-assistance”, local farmers have formed relationships with individuals beyond traditional social ties—such as village administrators and non-kin relatives—whom they had previously not interacted with. Within this new social network, village cadres frequently visit farmers’ households, engaging in communication and providing the latest agricultural policies, as well as propagandizing scientific knowledge and development concepts. These casual interactions help to address information asymmetry and foster trust, facilitating cooperation among farmers [1]. First, cadres assist the village’s Party branch and committee in conducting relevant management and technical training, breaking the information barriers between farmers and government, which encourages mutual learning and a supervision mechanism between villagers and administrators. This enhances farmers’ understanding and acceptance of investments in farmland irrigation facilities [15]. Second, through reciprocal assistance, farmers exchange feedback on irrigation management, improving water resource accessibility and mitigating operational and financial challenges, especially when adopting water-saving technologies [16]. These factors collectively stimulate farmers’ enthusiasm and initiative for participating in investments. Therefore, we propose the second hypothesis that newly emerged social capital has a positive impact on farmers’ participation in the management and maintenance of farmland irrigation facilities.

2.3. The Role of Non-Agricultural Employment

Social capital not only directly influences farmers’ participation in investment decisions concerning farmland irrigation facilities, but also mediates this participation through non-agricultural employment.

Social capital plays a significant role in facilitating rural households’ migration for non-agricultural employment [17]. It helps rural laborers access employment information, reduces search costs for non-agricultural jobs, and prevents inefficiencies in labor mobility due to information asymmetry, thus promoting rural labor migration for employment [18]. Simultaneously, social networks provide crucial employment information, which increases non-agricultural employment among rural households [19,20].

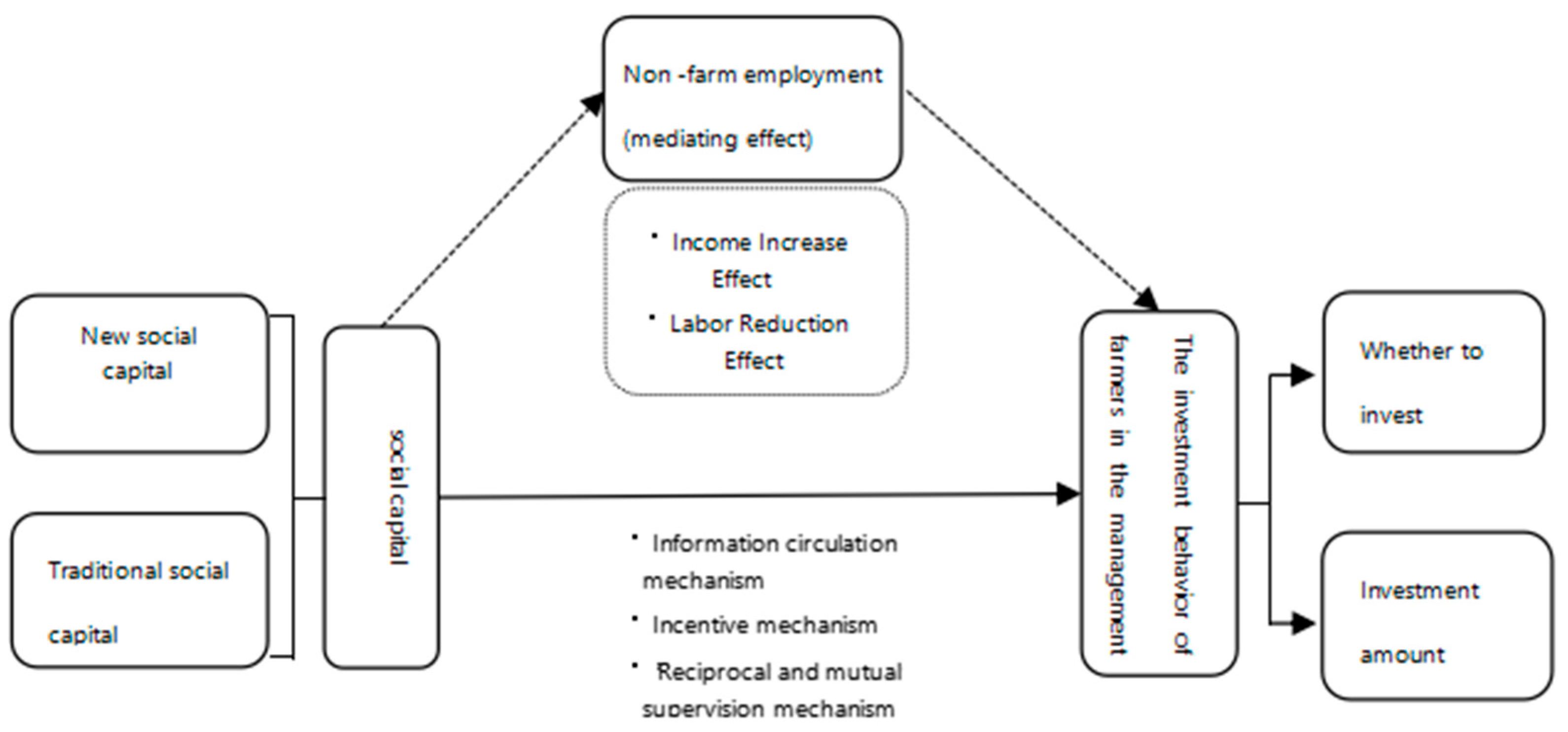

The impact of non-agricultural employment on investments in farmland irrigation facilities is ambiguous. As farmers engage in non-agricultural employment, the number of laborers dedicated to agricultural production decreases, while their wage income typically increases. Since agricultural production is heavily influenced by natural conditions, and the quality of irrigation directly affects productivity, farmers in underdeveloped labor markets often rely on agriculture as a stable source of livelihood. In arid and semi-arid areas, where agricultural productivity is highly dependent on irrigation water, farmers are motivated to invest in irrigation facilities to ensure stable or increased yields [21]. In other words, when farmers secure high-income, long-term non-agricultural employment, their household income becomes more stable and less susceptible to external fluctuations. This reduces the uncertainty of income and weakens precautionary savings motives, which leads to an increase in irrigation investments. Additionally, greater income stability enhances farmers’ risk-bearing capacity, encouraging them to adopt higher-risk, higher-return irrigation technologies and invest more in irrigation canal maintenance, thereby boosting agricultural income and increasing the likelihood of further irrigation investments [22]. Furthermore, non-agricultural employment income supplements farmers’ household income, reducing the risks associated with a diminished agricultural labor force. Thus, non-agricultural employment positively influences investments in farmland irrigation facilities. Based on the discussions above, we propose the third hypothesis that non-agricultural employment has a positive impact in strengthening the roles of both traditional and newly emerged social capitals in inducing farmers’ participation in the management and maintenance of farmland irrigation facilities. The theoretical links among social capital, farmers’ investments in public irrigation facility maintenance and management, as well as off-farm employment, are shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical analysis framework of social capital, non-agricultural employment, and investment in management and maintenance of farmland irrigation facilities.

3. Research Site and Dataset

3.1. Research Site

Our research site is located in Awati County, Aksu Prefecture, in southwestern Xinjiang, which neighbors the northern edge of the Taklimakan Desert. Awati County is known as the land of long staple cotton, a designation given by the Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 2001. In 2015, the total sown area of cotton was 1,345,806 mu, with around 95 percent being not intercropped with Jujube or other fruit. To address challenges such as water scarcity and competition between domestic, industrial, and agricultural water use, the Aksu region of Xinjiang has prioritized infrastructure development and policy implementation, actively encouraging both enterprises and farmers to adopt reforms in the field of high-efficiency water-saving agriculture. As early as 2006, the local government began to promote subsurface drip irrigation technology, particularly in cotton cultivation.

In Awati County, there are around 267 ha of demonstration zones for drip irrigation, along with 700 ha of supporting facilities for large-scale dissemination. These initiatives resulted in an approximately 8% increase in cotton yield per unit area and a 10% improvement in fertilizer utilization efficiency. Statistical data revealed that the notable gains in water-use efficiency significantly motivated the local government, leading to sustained increases in investment and promotional efforts for drip irrigation in subsequent years. By 2014, a dedicated fund of 12.06 million RMB was allocated to the county, with the goal of expanding water-saving irrigation to an additional 2680 km2 within the year. In 2014, Aksu Prefecture poured a total of 137.66 million RMB for farmland water conservancy infrastructure. Of this amount, 37.169 million RMB came from central government investment, 20.4672 million RMB from the Xinjiang Autonomous Region budget, 23.038 million RMB from project-matching funds, and 56.989 million RMB (around 41.4% of the total) from farmer self-financing. The construction effort mobilized 36,300 workers, contributing a total of 279,600 labor days. Key achievements included dredging 20 km of drainage canals, leveling 700 hectares of farmland, improving irrigation coverage across 11,000 hectares, and constructing or upgrading 20 km of anti-seepage irrigation channels. Located in a typical arid zone, the study area’s agricultural productivity is highly dependent on the cooperative management and maintenance of irrigation canal systems, which directly influences crop yields.

3.2. Data Collection

The data used in this study were obtained from a field survey conducted in Awati County, Xinjiang, in February 2017. A combination of stratified and random sampling methods was employed to ensure data quality. First, towns and villages were selected based on geographic location (upper, middle, and lower reaches of the irrigation basin, and distance from the county center), level of socio-economic development, and agricultural resource endowments. Second, within each selected village, households were randomly sampled from rosters provided by village officials, following a “one in every five households” selection rule. The survey covered 774 households from 17 villages. The questionnaire collected detailed information on social capital, households’ investments in agriculture, household characteristics, utilization of land and water resources, agricultural input–output data, socio-cultural attributes, and village-level features. As this research focuses on farmers who make investment decisions regarding farmland irrigation facilities, 62 households without contracted farmland and 12 households with missing key variables were excluded, resulting in 700 valid observations. To ensure the reliability and accuracy of the survey, all enumerators were Uyghur graduate or senior undergraduate students majoring in agricultural economics or land resource management. Prior to data collection, they received systematic training on the questionnaire content from subject-matter experts.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Model Specification and Estimation Strategy

To empirically investigate the impacts of two types of social capital on farmers’ participation in the collaborative management and maintenance of farmland irrigation facilities, this study focuses on the maintenance, improvement, and/or construction of public irrigation canal systems at both the village collective and village group levels. Farmers’ participation in these activities is categorized by whether they invest and the total amount invested. Based on survey data, farmers’ investments in irrigation system management and maintenance include both monetary contributions and labor inputs. For consistency in quantitative analysis, labor inputs are converted into monetary equivalents by multiplying the number of labor days contributed by the local daily wage rate. Since the outcome of total investment in the second stage is only observable when farmers decide to invest, potential sample selection bias must be considered. To address this, a Heckman test was performed, which revealed that the inverse Mills ratio was −0.057 (p = 0.863) and not statistically significant, indicating the absence of sample selection bias in this study. We specified the basic investment model as follows in Equation (1):

where indicates whether farmer i participates in the investment decision of the management and maintenance of farmland irrigation facilities. is the social capital of farmer i (including traditional social capital as well as newly emerged social capital). are other control variables that affect farmer i’s participation in the investment decision-making of irrigation facility management and maintenance. and are parameters to be estimated; is the regression intercept. is a random error term.

Regarding estimation strategy, a Tobit model is constructed to explore the impact of social capital on farmers’ investment levels in the maintenance and management of farmland irrigation facilities. The foundational framework of the model is outlined as follows:

where is the total investment amount of farmer i in the management and maintenance of farmland irrigation facilities. is the social capital of farmer i (including new social capital and traditional social capital). are other control variables that affect the total investment of farmer household i in the management and maintenance of irrigation facilities. and are parameters to be estimated; is the regression intercept. is a random error term.

Furthermore, to verify the mediating effect of non-agricultural employment on the relationship between social capital and farmers’ investment behavior in the management and maintenance of farmland irrigation facilities, we conducted a mediation effect test following the methodology proposed by Wen et al. (2014) [23]. The models were established as follows:

where refers to the investment behavior of farmer i in the management and maintenance of farmland irrigation facilities (including whether to invest and the investment amount). is the social capital of farmer i (including new social capital and traditional social capital). is the intermediary variable non-farm employment. are other control variables that affect farmer i’s investment behavior in the management and maintenance of farmland irrigation facilities. is a constant term; are random error terms. represents the total effect of social capital on farmers’ investment behavior in participating in the management and maintenance of farmland irrigation facilities. represents the direct effect of social capital on their non-agricultural employment. and , respectively, represent the direct effects of social capital and non-agricultural employment on farmers’ investment behavior in participating in the management and maintenance of farmland irrigation facilities.

4.2. Variable Definition and Description

Explanatory Variable: The dependent variable refers to farmers’ investment behavior in the management and maintenance of irrigation facilities. This is specifically defined as the material and labor inputs by farmers in the maintenance, improvement, or construction of public irrigation canal systems at the brigade or team level. It consists of two components: first, whether a farmer invests, which is coded as 1 for “yes” and 0 for “no”; second, for cases where investment occurs, the total investment amount is measured, and a logarithmic transformation is applied.

Key Explanatory Variable: Social capital is selected as the core explanatory variable and is distinguished into two types, namely, the traditional social capital and the newly emerged social capital.

Mediating Variable: Regarding the mediating variable, we refer to non-agricultural employment. It is measured as the non-agricultural employment rate of family members, which is the ratio of the number of non-agricultural laborers to the total number of family laborers.

Control Variables: Based on a review of the relevant literature, four categories of control variables are selected: (i) characteristics of the household head, including gender, age, educational attainment, and experience in off-farm employment; (ii) characteristics of the farmer household, including the proportion of agricultural labor, the current value of household fixed assets, land area, land salinization degree, perception of irrigation importance, and irrigation satisfaction; (iii) the household head’s perception of village irrigation, including perceptions of the importance of irrigation and irrigation satisfaction; and (iv) village characteristics, including government investment intensity in irrigation facilities and the distance from the county seat. Additionally, township dummy variables are included to account for unobserved factors. The definitions and descriptions of the variables introduced are shown below in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable definition and description.

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Impact of Social Capital

Using STATA 14.0, we conducted regression analysis on farmers’ investment behavior in irrigation facility management and maintenance. Table 2 below presents the results. The model demonstrates good fit, as evidenced by the log-likelihood value and likelihood ratio test. Moreover, the chi-square test values for both stages were statistically significant at the 1% level. The results indicate that social capital significantly influences farmers’ cooperative maintenance behavior of irrigation facilities.

Table 2.

Estimation results of social capital on farmers’ land transfer behavior.

Both new and traditional social capital positively affect farmers’ investment decisions in irrigation facilities at the 1% and 5% significance levels, respectively. Similarly, both types of social capital positively influence investment amounts at the 5% level, supporting Hypotheses 1 and 2.

The positive effect of newly emerged social capital stems from government-initiated programs like “Visit, Benefit, and Consolidate”, which embed work teams in rural communities. Village cadres frequently interact with farmers, disseminating agricultural policies, providing technical training, and fostering mutual learning. This enhances farmers’ understanding of irrigation investments and facilitates better water resource management through collective supervision and assistance. Traditional social capital, rooted in kinship and local networks, similarly promotes cooperation by leveraging established trust and reciprocity mechanisms.

5.2. The Role of Non-Farm Employment

To examine the mediating effect of non-agricultural employment, we incorporated this variable into our analytical model. Following Wen et al. (2014) [23], we implemented a stepwise regression approach. Table 3 shows both new-type and traditional social capital significantly enhanced non-agricultural employment at 1% and 10% levels, respectively, confirming social capital’s positive influence on rural households’ off-farm employment opportunities.

Table 3.

Test results of the intermediary effect of non-agricultural employment.

For investment decisions, when including both social capital and non-agricultural employment simultaneously (with reference to Table 2 results), new-type social capital showed a significantly positive effect with coefficient increasing from 0.51 to 0.54, indicating mediation. Similarly, traditional social capital’s coefficient rose from 0.77 to 0.85, demonstrating that its effect operates through non-agricultural employment.

Regarding investment amounts, simultaneous inclusion of both factors revealed new-type social capital’s positive influence with coefficient increasing from 1.49 to 1.58, while traditional social capital’s coefficient grew from 2.35 to 2.52. These consistent increases across specifications confirm non-agricultural employment’s mediating role in both social capital types’ effects on irrigation investments.

5.3. The Impact of Other Control Variables

The age of the household head positively correlates with investment decisions (5% significance) and amounts (10% significance). Older farmers, with greater agricultural experience and limited off-farm employment opportunities, recognize the benefits of irrigation facilities and rely more heavily on them. Conversely, education level negatively affects investment decisions and amounts (10% significance), as higher education facilitates non-agricultural employment, reducing dependence on farming. Similarly, household fixed assets positively influence investment decisions (5% significance) and amounts (10% significance). Wealthier farmers face fewer financial constraints and are more likely to invest when irrigation benefits outweigh costs. In contrast, land area negatively affects investment (10% significance). The negative relationship between total land area and investment likelihood reflects the fact that larger landowners typically already own private irrigation systems and face different marginal incentives. The proportions of agricultural labor and soil salinization were insignificant, though the former exhibited a positive trend. Soil salinization was not significant likely due to coarse measurement, limited variation, or substitution through other adaptation strategies such as crop rotation or drainage works. Likewise, irrigation satisfaction positively impacts investment (10% significance). Water quality may influence yields more directly than investment choices; future research should include objective measures and model both yield and investment outcomes. Farmers dissatisfied with current conditions are more motivated to improve facilities. The perceived importance of irrigation was insignificant, likely because actual investment decisions depend on external factors beyond awareness. In contrast, government investment negatively affects individual contributions (5% significance), indicating a crowding-out effect. Farmers in areas with government support may reduce their own investments due to reliance on public funding.

5.4. Robustness Test

However, there are differences in the impacts of new-type social capital and traditional social capital on farmers’ investment behavior in the management and protection of farmland irrigation facilities, considering that these two types of social capital are intertwined and integrated within rural communities, and there may be some omitted factors or correlations between them. Therefore, a model robustness estimation was further carried out. A comprehensive social capital variable was introduced into the model to test its impact on farmers’ investment behavior in farmland irrigation facilities. The results are shown in Table 4. Except for a few control variables, the estimation results are basically similar to those in Table 2, indicating that comprehensive social capital has a significant positive impact on both farmers’ participation in the management, protection, and investment of farmland irrigation facilities and the amount of investment. The estimation results of this paper are relatively robust and reliable.

Table 4.

Results of robustness test.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This section aims to, from a micro-level perspective, combine the survey data of farmers in Awat County, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Based on the theoretical analysis in the previous text, it empirically examines the impacts of new-type social capital and traditional social capital on farmers’ investment behavior in the management and maintenance of farmland irrigation facilities, and also focuses on the mediating effect of non-agricultural employment.

The research findings are as follows:

(1) The new-type social capital formed through the intervention of village resident cadres and the traditional rural social capital both have a significant positive impact on farmers’ decision-making regarding participation in the management, maintenance, and investment of farmland irrigation facilities, as well as the amount of investment. Our research shows that in today’s rural grassroots governance system with the collaborative participation of multiple subjects, the new type of social capital formed by the “Visit, Benefit and Consolidate” working group, which is an intervention by the government, is embedded in rural grassroots. In this new social network, cadres stationed in villages frequently visit rural households. They use the scientific knowledge and new development concepts they have mastered to provide farmers with the latest publicity of agricultural policies, carry out relevant management and technical training and support, and encourage villagers and administrators to learn from and supervise each other. As a result, farmers’ cognitive level of investment in farmland irrigation facilities and their degree of recognition of policies have been improved.

(2) Social capital not only has a positive and significant impact on farmers’ decision-making regarding investment in the management and maintenance of farmland irrigation facilities and the amount of investment, but can also positively promote farmers’ non-agricultural employment. This, in turn, enhances farmers’ farmland transfer behavior, indicating that non-agricultural employment plays a mediating role. That is, new-type social capital and traditional social capital increase farmers’ non-agricultural employment opportunities through means such as providing employment training and transmitting employment information. Subsequently, non-agricultural employment income, as an important supplement to farmers’ family income, helps to mitigate the risks of agricultural planting brought about by the reduction in family labor force. Ultimately, the family’s non-agricultural employment behavior has a positive impact on farmers’ investment behavior in farmland irrigation facilities.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, C.Z., A.A. and F.R.; investigation, C.Z. and X.S.; data curation, C.Z., A.A. and F.R.; writing—review and editing, C.Z., A.A. and F.R.; funding acquisition, A.A., F.R. and X.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72173061, “Implementation of Farmland Property Rights Policies under Village-Level Autonomy, Property Rights Status, and Mismatch of Circulation Supply-Demand: Influence Mechanism and Policy Optimization”; 72173065, “The impact of the reform of agricultural land property rights system and grassroots governance on the efficiency of water and soil resource utilization—based on the analysis of Jiangsu, Hebei, and Xinjiang”; 72463031, “Research on the Comprehensive Management and Quality Improvement Strategies of Salinized Cultivated Land from the Perspective of Multi-Subject Collaborative Governance: A Case Study of Xinjiang”); and the Xinjiang New Agricultural Science Education Alliance Project (2022XNJMCX04, “Exploration and Practice of Collaborative Education Mechanism Based on the Main Body of Xinjiang New Agricultural Science Education Alliance”).

Data Availability Statement

All survey and farm-level data used in this study were anonymized prior to analysis. No personally identifiable information or confidential business data are included in the reported dataset. The processed dataset that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abudureheman, A.; Rao, F.; Ma, X.; Shi, X. Impact of collaborative governance on farmers’ participation in collective maintenance of soil and water conservation facilities. Resour. Sci. 2022, 44, 1949–1963. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kimutai, E.K.; Osimbo, V.L. The status and challenges of a modern irrigation system in Kenya: A systematic review. Irrig. Drain. 2022, 71 (Suppl. S1), 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z. Reciprocal mutual benefit, punitive mutual benefit and voluntary cooperative supply of small-scale farmland water conservancy facilities: A case study of Z Village. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 17, 92–100+164–165. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, B. Tax reform, “one case one discussion” and the dilemma of village governance. Chin. Public Adm. 2003, 9, 50–51+56. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zang, L.; Araral, E.; Wang, Y. Effects of land fragmentation on the governance of the commons: Theory and evidence from 284 villages and 17 provinces in China. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, W.F.; Ostrom, E. Analyzing the dynamic complexity of development interventions: Lessons from an irrigation experiment in Nepal. Policy Sci. 2010, 43, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social capital, collective action, and adaptation to climate change. Econ. Geogr. 2003, 79, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, G. The role of multilateral institutions in international trade cooperation. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 190–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Walker, J. Trust and Reciprocity: Interdisciplinary Lessons for Experimental Research; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jules, P. Social capital and the collective management of resources. Science 2003, 302, 1912–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanditov, B.; Arora, S. Social network and private provision of public goods. J. Evol. Econ. 2016, 26, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cai, Q.; Zhu, Y. Impacts of social capital and income disparity on collective village action: Evidence from farmers’ participation in maintenance of small-scale farmland water conservancy facilities in three provinces. J. Public Manag. 2016, 13, 89–100. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E.; Ahn, T.K. The meaning of social capital and its link to collective action. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2008, 10, 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. State presence and local logic of targeted poverty alleviation in Xinjiang’s ethnic areas: Field research in Hotan Prefecture. Xinjiang Soc. Sci. Forum 2021, 6, 56–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lambrecht, I.; Vanlauwe, B.; Merckx, R.; Maertens, M. Understanding the process of agricultural technology adoption: Mineral fertilizer in Eastern DR Congo. World Dev. 2014, 59, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escott, H.; Beavis, S.; Reeves, A. Incentives and constraints to Indigenous engagement in water management. Land Use Policy 2015, 49, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.; Yueh, L. The role of social capital in the labor market in China. Econ. Transit. 2008, 16, 389–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, L.; Ying, R. Analysis of factors influencing rural labor migration: From the perspective of social networks. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2010, 8, 73–79. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. Analysis of social capital in rural labor mobility. Rural Econ. 2008, 6, 78–82. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Diao, L. Social capital, non-agricultural employment and rural poverty. J. South China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 17, 61–71. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C. Impact of non-agricultural employment on farmers’ willingness to maintain Grain for Green results: Based on survey of 1132 farmers. China Land Sci. 2020, 34, 67–75. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Hu, L.; Lu, Q. Effects of farmers’ risk preference and risk perception on willingness to adopt water-saving irrigation technologies. Resour. Sci. 2018, 40, 797–808. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Mediation effect analysis: Methods and model development. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).