1. Introduction

Water is a critical natural resource, indispensable for life, environmental well-being, and economic development [

1]. However, water resources are becoming increasingly threatened due to climate change impacts and a growing demand from agriculture, industries, and domestic sectors, as well as pollution [

2]. Agriculture consumes nearly 70% of global freshwater withdrawals, and inefficient water use in this sector poses significant risks to the environmental sustainability and economic stability of communities that rely heavily on agriculture [

3]. Therefore, effective water governance is essential to achieve equitable, efficient, and sustainable management of water resources in the face of growing social, economic, and environmental pressures. Recognizing the urgency of these issues, numerous actors and agencies have initiated frameworks, partnerships, and policy reforms to strengthen water governance at the local, national, regional, and international levels [

4]. According to OECD [

5], water governance encompasses the “range of political, institutional and administrative rules, practices and processes through which decisions are taken and implemented, stakeholders can articulate their interests and have their concerns considered, and decision-makers are held accountable for water management.”

Esmeraldas, a province in Ecuador known for its cultural richness and biodiversity, possesses significant potential for agritourism. By integrating the agriculture and tourism sectors, the region can promote sustainable rural development and generate new socio-economic opportunities [

6]. However, this potential is constrained by several challenges, including the impacts of climate change, inadequate water infrastructure, institutional fragmentation, inefficient water use, and socio-economic inequalities [

7]. For instance, less than 50% of households in most cantons of Esmeraldas have access to running water, while sewer coverage remains below 6% in most rural areas [

8]. This limited access to water is further worsened during peak tourism periods. A notable example occurred in August 2017, when the influx of 40,000 tourists to Atacames forced local authorities to ration water and rely on tanker deliveries to meet demand [

9].

Environmental degradation has further intensified the water governance crisis. Between 1990 and 2018, Esmeraldas province lost about 308,000 hectares of forest, which compromised watershed regulation and increased sediment loads in rivers [

10]. In 2007, about 60% of residents resided in areas highly susceptible to flooding and landslides, revealing deeper governance failures rooted in marginalization and vulnerability [

11]. Additionally, illegal mining and agro-industrial runoff have chronically polluted rivers in the province. Recently, on 13 March 2025, a major oil spill from the rupture of the Trans-Ecuadorian Pipeline System (SOTE) released 25,166 barrels of crude oil, leaving nearly 500,000 residents without potable water [

12] and over 51,500 households in urgent need of emergency assistance [

13]. These recurring environmental crises underscore the urgent need for effective water governance frameworks that integrate social, administrative, and political systems to ensure resilient water management [

14].

In recent years, there has been growing interest in water governance to achieve global goals such as the United Nations‘ Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 6—clean water and sanitation), as well as water security amid climate change and growing demand. Scholars and international organizations typically conceptualize water governance through the following three main paradigms: integrated water resources management (IWRM), the human right to water and sanitation, and polycentric governance. These paradigms insist on cross-sectoral planning at the hydrological scale, prioritize equitable access, and distribute authority across interacting centers so that learning and mutual accountability can co-exist, respectively [

15,

16,

17]. Despite these efforts, water governance is still unevenly adapted and implemented globally. For instance, Latin America has made significant progress with rights-based and participatory water governance models [

18], while many African countries, despite having integrated water resources management (IWRM) institutions, continue to face limited capacity and inconsistent financing, which undermine the ability to achieve the SGD 6 targets [

19,

20]. Similarly, while most Asia–Pacific countries have adopted modern water policies, critical gaps persist in data availability, regulatory enforcement, and stakeholder engagement, which could force about 3.4 billion people to live in water-stressed regions by 2050 [

21].

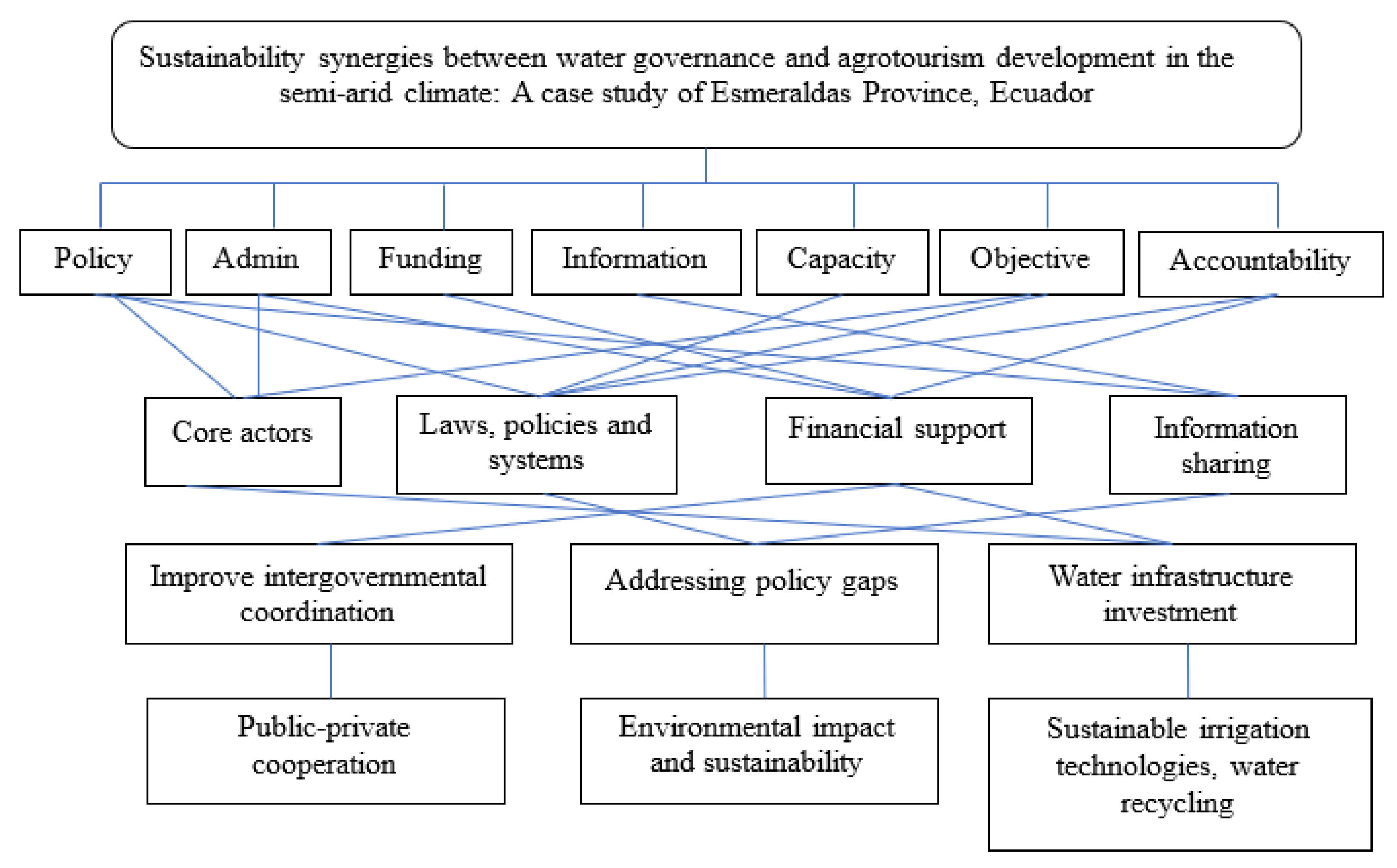

Therefore, this study aims to evaluate how sustainable water governance and its potential can support agrotourism development in Esmeraldas Province, Ecuador, through a mixed-methods approach. Specifically, questionnaires were administered to relevant stakeholders in order to identify and prioritize the key challenges impeding water governance in Esmeraldas Province using multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA). In addition, we also analyzed existing legal and policy frameworks to identify the institutional and regulatory impediments in Esmeraldas province. Finally, we quantified water availability in this province during 1980–2022 using the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI), a drought index.

4. Discussions

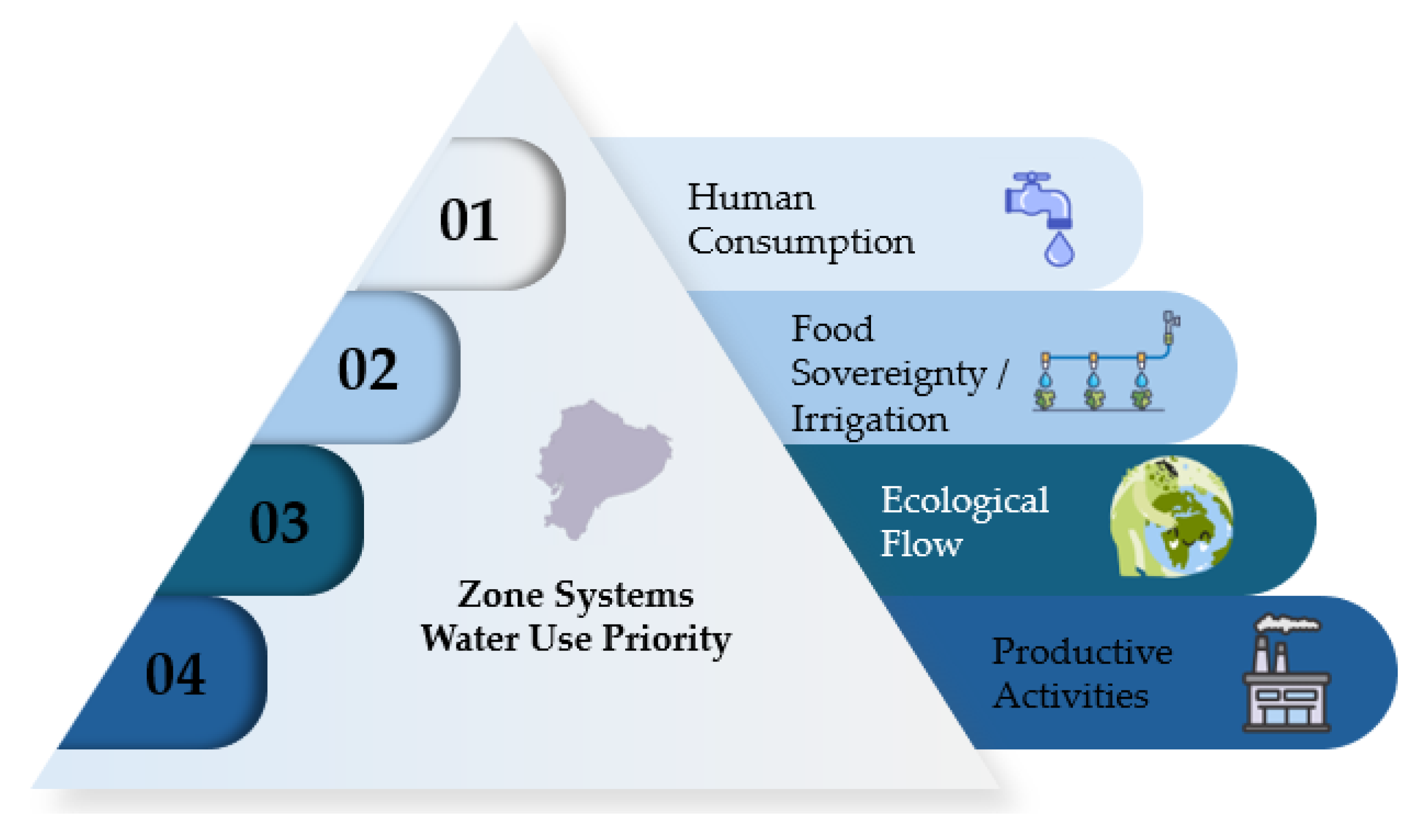

Water governance in Ecuador presents a paradox: although the country has a progressive legal framework [

27], reality reveals the deficit in governance implementation, including insufficient coordination between different government levels [

31,

32] in many regions, particularly in Esmeraldas. This interferes with the sustainability of agrotourism in the province [

30]. Key challenges, including a lack of water infrastructure and gaps in policies and regulations, are the main issues affecting all stakeholders, which indicates a common concern about institutional and structural failure. This fragmentation is exacerbated by weak stakeholder engagement mechanisms, particularly the limited participation of farmers and rural residents directly affected by water management policies [

26,

33,

34,

35].

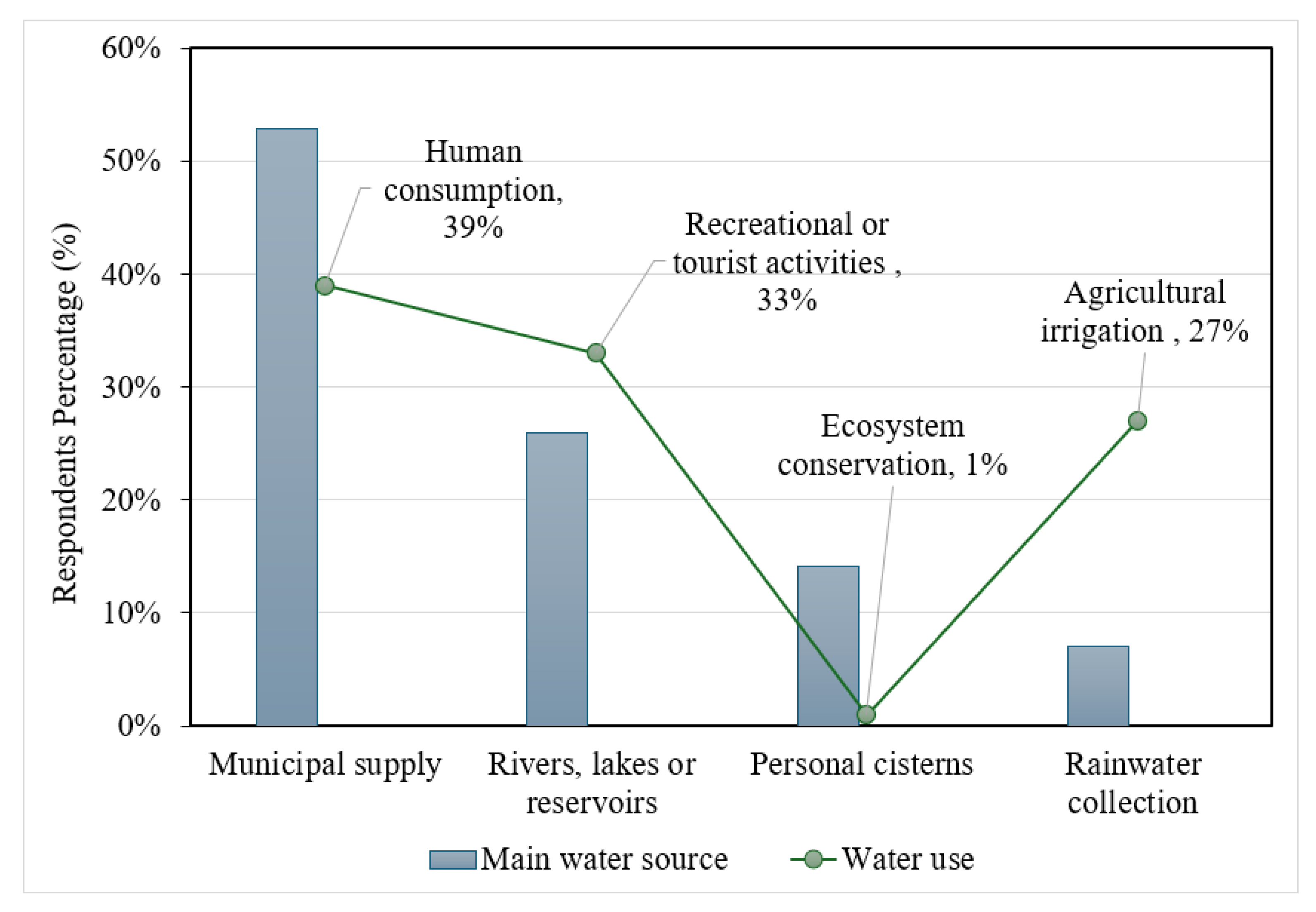

Competing demands for water from agriculture, tourism, and human consumption intensify these challenges, particularly in the absence of adequate regulations and incentives for efficient water allocation in emerging agrotourism sectors [

36,

37]. Additionally, the framework addresses balancing through several interconnected governance components: stakeholders’ cooperation, efficient technologies adoption, and water allocation practices. Acute events like droughts and chronic water treatment, storage, and distribution deficiencies worsen situations [

12]. Furthermore, environmental degradation due to mining, deforestation, and agriculture adversely affects water quality and availability [

38,

39,

40]. Climate change is putting additional pressure on the province’s fragile infrastructure, manifesting in more frequent and severe floods and droughts, which negatively impact agriculture and tourism [

41]. A clear example is the pronounced and persistent drought scenarios that Esmeraldas experienced from the early 2000s through the 2010s, visible in Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) values reaching below −3, indicating severe extreme drought and affecting the potential development of the agrotourism sector in the province, as obtained by the SPEI analysis [

49]. Although droughts have always been a natural part of the climatic patterns in the area, the frequency and intensity of droughts are increasing, mainly due to global warming, deforestation, and human-induced forest degradation [

11]. Studies based on modeling and observations suggest that the droughts occur due to decreased precipitation and a delayed onset of the rainy season, resulting in a longer dry season, especially during El Niño and/or the Oceanic and Atmospheric Niño Index years [

78]. Through the SPEI, we could highlight an alarming trend: climate-induced droughts are not isolated anomalies, but a growing norm threatening rural water supplies [

2]. These conditions, confirmed by Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projections and recent research in tropical regions [

49], compromise food security and the sustainable tourism objectives set out in SDG 8.9, which aim to create jobs while promoting local products and culture [

79].

The multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) conducted as part of this study revealed that, while infrastructure deficiencies are a major problem, they are symptomatic of a deeper problem: rigid, inflexible governance structures unable to respond to dynamic environmental challenges. Comparisons with adaptive and community-based models in Bolivia and Peru highlight that more resilient water governance is both possible and necessary [

78]. In Esmeraldas, the prevailing reactive attitude limits long-term sustainability, particularly in agrotourism, which relies heavily on access to quality water.

It is also important to note that civic engagement and behavior change challenges are inextricably linked to educational attainment. Many farmers and tourism operators lack formal education, which limits their participation in governance and their ability to adopt innovative practices. This reveals the need for SDG 4 to provide inclusive, quality education as a foundation for sustainable development [

80] and supports UNESCO’s assertion that access to knowledge is the foundation for meaningful civic engagement [

81]. Addressing these constraints would not only accelerate progress toward SDG 6.4, which encourages improving water use efficiency, but also align Esmeraldas with global best practices [

82].

Limitations and Prospects

This study explores the sustainability synergies between water governance and agrotourism development in a semi-arid region in Ecuador. It also developed a sustainable framework that proposes context-driven and practical solutions to the water governance challenges in water-scarce areas and climate-vulnerable regions. However, the study acknowledges several limitations that could be addressed to improve the accuracy and depth of its analysis. For instance, incorporating methodologies such as the Adaptive Participatory Integrated Approach (APIA), co-production frameworks, Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), or Delphi technique could foster stronger local engagement and enhance institutional ownership of water governance processes. Such participatory methods would also help to legitimize decision making and ensure that governance reflects the needs and perspectives of a broader range of stakeholders. Another limitation lies in the sample size; although 250 respondents provided valuable insights, this number may not fully capture the diversity of stakeholders in the region. In this study, the prioritization of governance gaps was based on the frequency with which these challenges were mentioned by the respondents. This method was appropriate for the exploratory nature of the study, as the primary objective was to identify the most pressing water governance challenges in the region. As the first analysis of its kind in this region, the relative weight approach could provide an important baseline for future studies. Despite these limitations, the study provides a critical foundation for understanding the relationship between water governance and agrotourism in semi-arid Ecuador. The findings not only highlight key challenges, but also set the stage for more in-depth, participatory, and methodologically intensive research in the future.

5. Conclusions

Our evidence shows that water governance and agrotourism are not competing agendas, but mutually reinforcing levels for rural resilience. By aligning climate triggers, fiscal incentives, and participatory institutions, Esmeraldas can transform its current “ping-pong governance” into a coherent system capable of delivering SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) outcomes in tandem. The study demonstrated the critical need for better water management systems to sustain both agriculture and tourism in Esmeraldas Province, Ecuador. The study integrated surveys, climatic data, and policy studies to create a holistic picture of the difficulties confronting water management and consumption in the area. It became evident that the existing system is not functioning as it should, since many people do not have reliable access to clean water, infrastructures are in poor condition, and key stakeholders like farmers and local communities are frequently kept from vital decisions. One of the most significant implications is that tackling these challenges does not simply mean constructing more pipelines or creating new laws. Real change would require active engagement of all relevant stakeholders. This involves listening to their perspectives, creating opportunities for them to share their ideas, and ensuring that each stakeholder has a meaningful role in the governance of water resources within their communities. The study suggests a more flexible, people-focused approach to water governance that will interconnect with multiple sectors, support better investments, and foster resilience. If implemented properly, this can become a model for other communities facing similar water and climate change challenges.