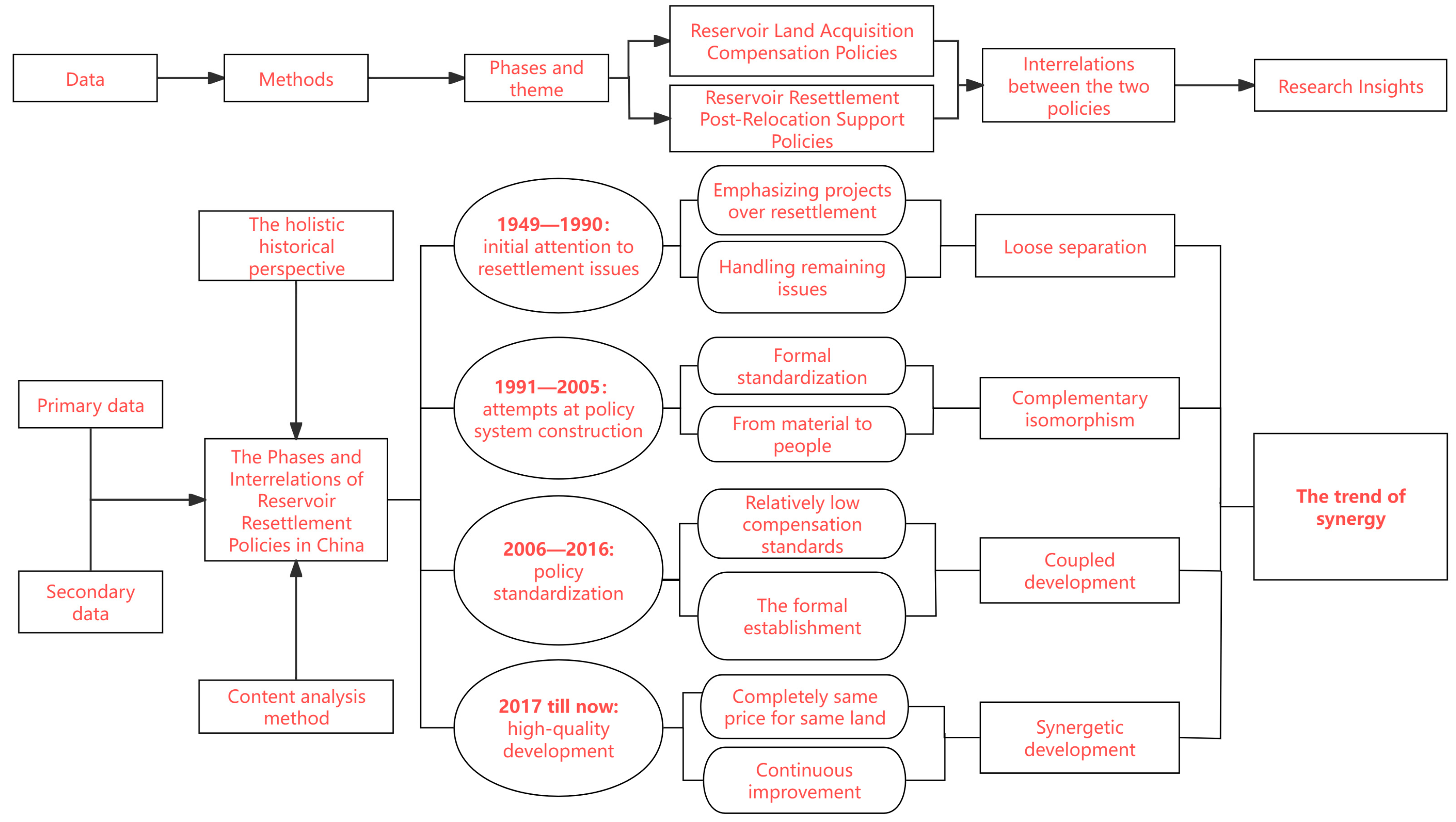

A Study on the Evolution and Interrelation of China’s Reservoir Resettlement Policies over 75 Years

Abstract

1. Introduction

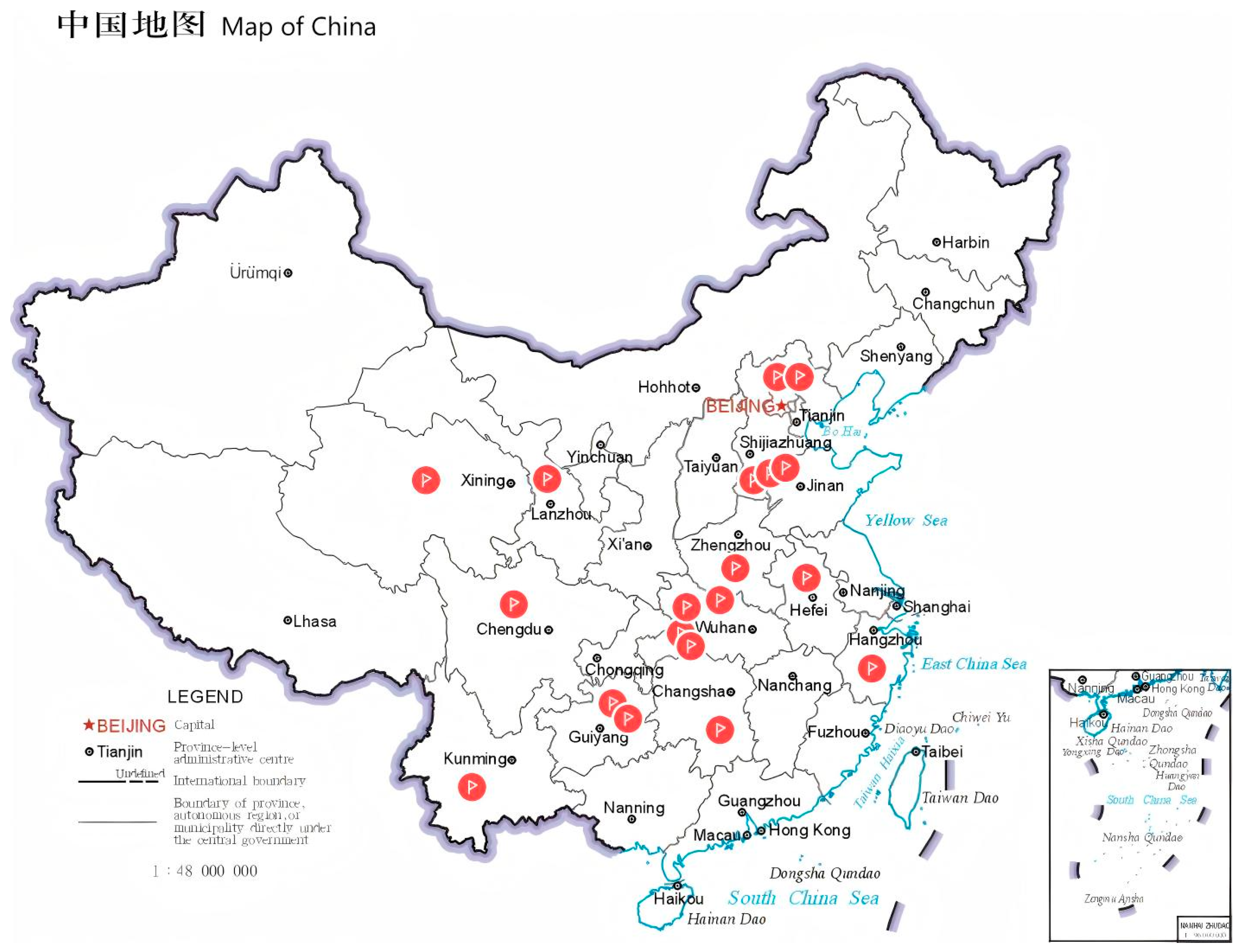

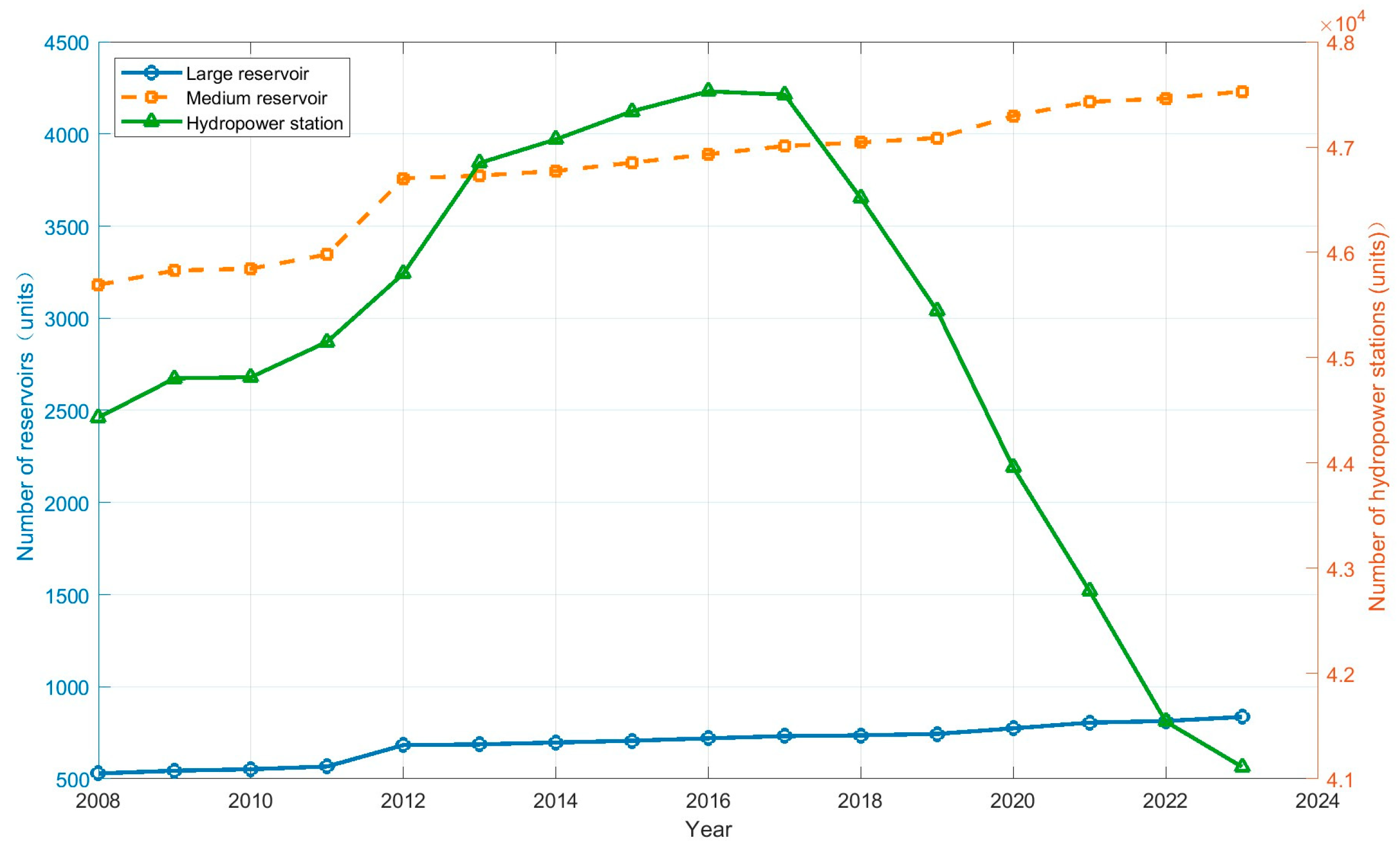

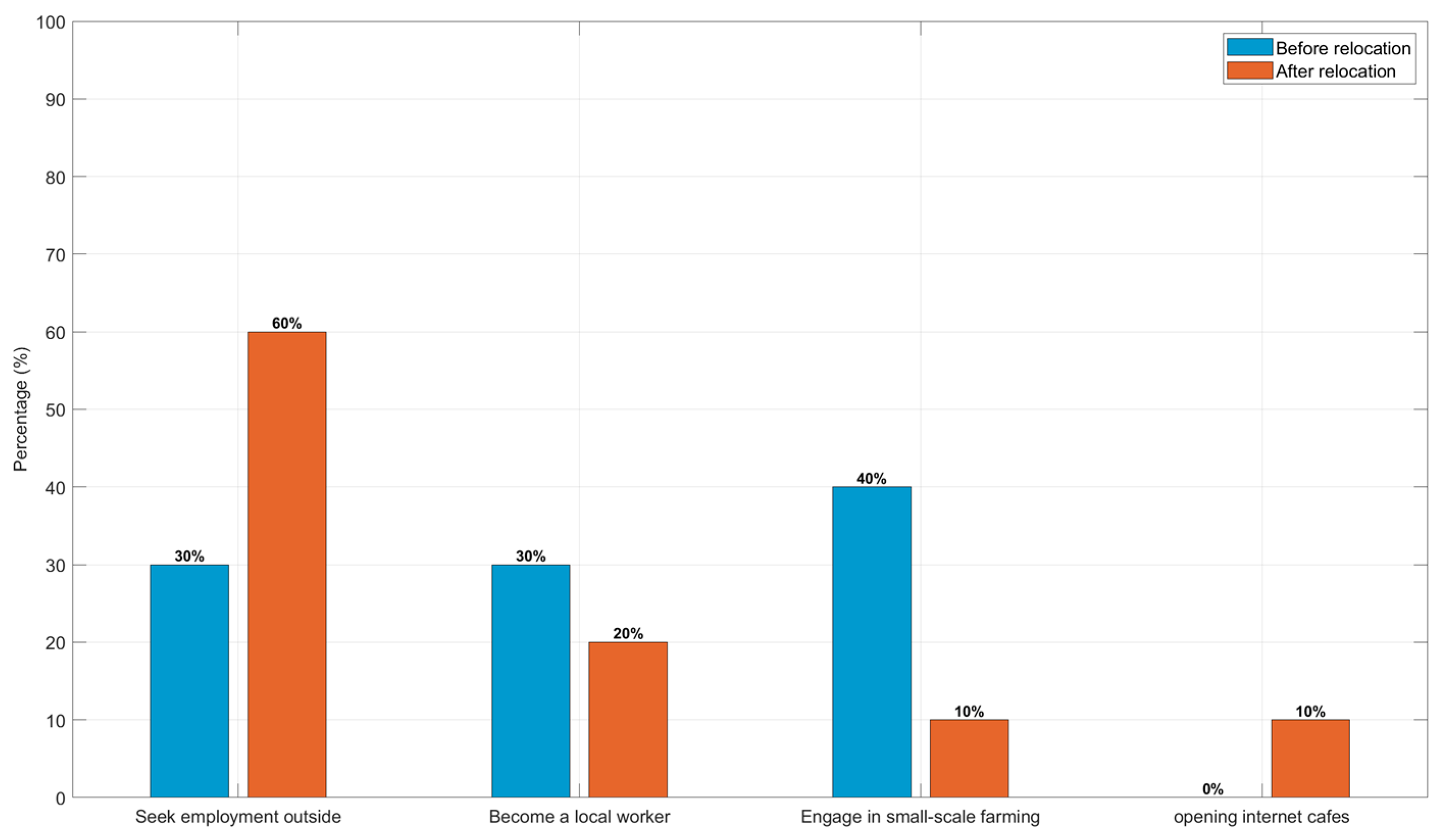

2. Materials and Methods

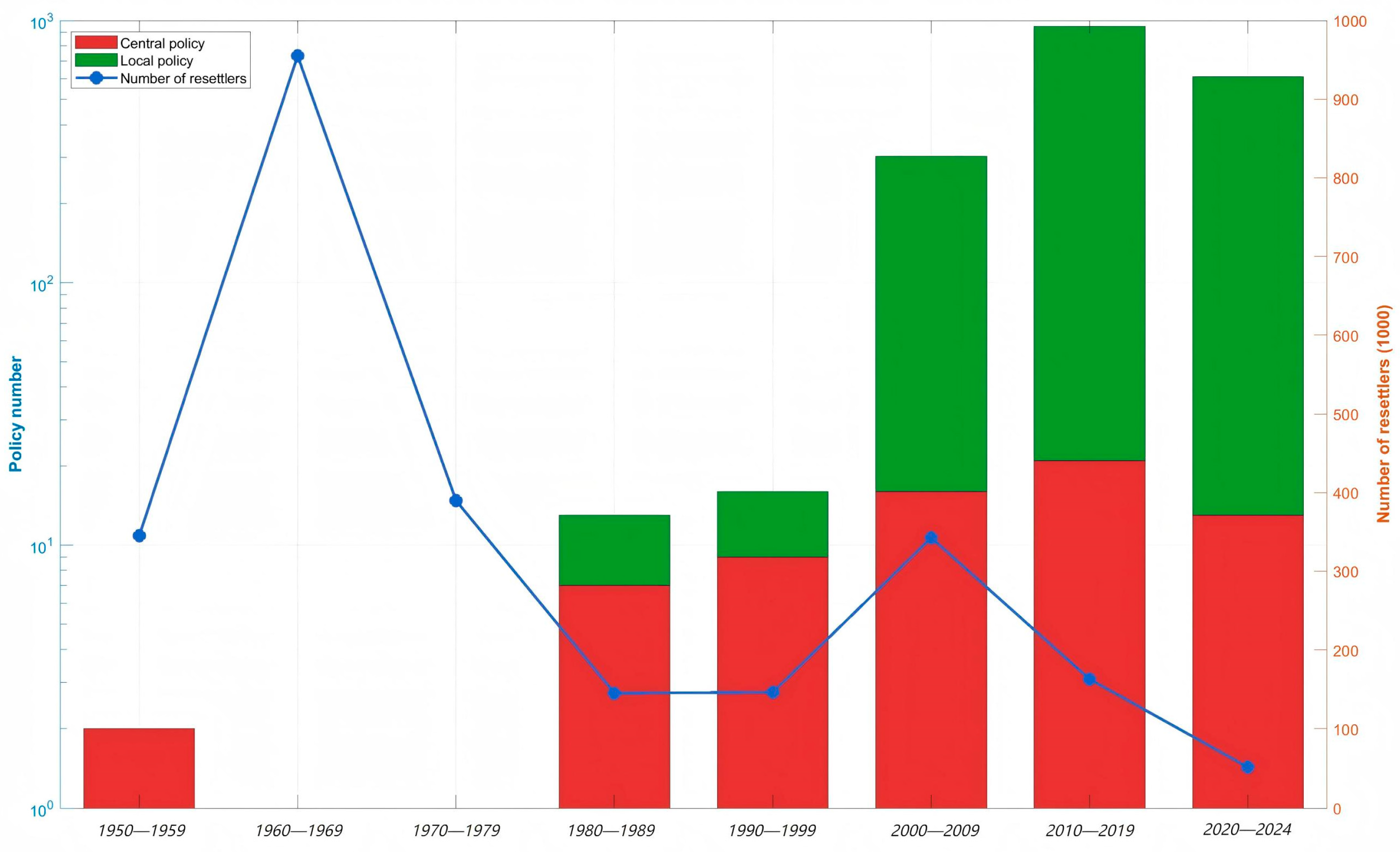

3. Results

3.1. Initial Attention to Resettlement Issues from 1949 to 1990

“Early reservoir resettlement in China was primarily driven by practice, with issues arising from the process leading to the development of policies”.

3.1.1. “Emphasizing Projects over Resettlers”—Land Acquisition Compensation Policies and Practices

“The 1980s marked a pivotal period for reservoir resettlement issues, coinciding with significant rural reforms such as the land contract system, which heightened land demand and exacerbated human-land conflicts”.

3.1.2. “Handling Remaining Issues”—Background and Practices of the Post-Relocation Support Policy

“Issues related to reservoirs provided formed the context for developing follow-up support policies and remained a central focus of policy efforts for an extended period”.

3.1.3. “Loose Separation”—The Interrelations Between the Two Policies

3.2. Attempts at Policy System Construction from 1991 to 2005

3.2.1. “Formal Standardization”—Land Acquisition Compensation Policies and Practices

3.2.2. “From Material to People”—Exploration and Practice of the Post-Relocation Support Policy

3.2.3. “Complementary Isomorphism” of the Two Policy Interrelations

3.3. Policy Standardization—Reorientation from 2006 to 2016

3.3.1. “Relatively Low Compensation Standards”—Land Acquisition Compensation Policies and Practices

3.3.2. “Formal Establishment”—Post-Relocation Support Policies and Practices

3.3.3. “Coupled Development”—The Interrelations Between the Two Policies

3.4. High-Quality Development Since 2017

3.4.1. “Completely the Same Price for the Same Land”—Land Acquisition Compensation and Subsidy Policies and Practices

“Compared to other projects, the standards for reservoir compensation were low for an extended period, resulting in significant demands from resettlers and prompting the subsequent introduction of regional comprehensive land prices”.

“Only in 2017 did reservoir compensation achieve ‘same land, same price’ with other projects”.

3.4.2. “Continuous Improvement”—Post-Relocation Support Policies and Practices

3.4.3. “Synergetic Development”—The Interrelations Between the Two Policies

| Stage | Year | Policy Name | Compensation Fee for Requisitioned Farmland | Resettlement Subsidy | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same land, same price | 1953 | Measures for Land Requisition for National Construction | Land expropriation compensation, 3–5 times | ||

| 1958 | Measures for Land Requisition for National Construction | Land expropriation compensation, 2–4 times | |||

| 1982 | Regulations for Land Requisition for National Construction (Decree No. 80 of The State Council) [55] | Land expropriation compensation, 3–6 times | Resettlement fee, 2–3 times | The total amount of compensation and resettlement subsidies for land expropriation shall not exceed 10 times. | |

| 1986 | Land Management Law of the People’s Republic of China | Land expropriation compensation, 3–6 times | Resettlement fee, 2–3 times; the maximum must not exceed 10 times | The total amount of compensation and resettlement subsidies for land expropriation shall not exceed 20 times. | |

| 1988 | Land Management Law of the People’s Republic of China (Amended) | Land expropriation compensation, 3–6 times | Resettlement fee, 2–3 times; the maximum must not exceed 10 times | The total amount of compensation and resettlement subsidies for land expropriation shall not exceed 20 times. | |

| Same land at different prices | 1991 | Regulations on Land Acquisition Compensation and Resettlement for the Construction of Large and Medium-Sized Water Conservancy and Hydropower Projects (Decree No. 74 of the State Council) [48] | Land expropriation compensation, 3–4 times | Resettlement fee, 2–3 times | The total amount of compensation and resettlement subsidies for land expropriation shall not exceed 20 times. |

| 1998 | Land Management Law of the People’s Republic of China (revised) | Land expropriation compensation, 6–10 times | Resettlement fee, 4–6 times | The total amount of compensation and resettlement subsidies for land expropriation shall not exceed 30 times. | |

| 2004 | Decision of The State Council on Deepening Reform and Strict Land Administration (Guofa (2004) No. 28) [56] | Under the comprehensive land price system for districts, the compensation fees for land expropriation shall be determined by the provincial people’s governments (block pricing may be applied for non-reservoir resettlement). | Block price is proposed for the first time. | ||

| 2004 | Land Management Law of the People’s Republic of China (Amended) | Land expropriation compensation, 6–10 times | Resettlement fee, 2–3 times; the maximum must not exceed 10 times | The total amount of compensation and resettlement subsidies for land expropriation shall not exceed 30 times. | |

| 2004 | Guiding Opinions on Enhancing the Compensation and Resettlement System for Expropriated Land (Land Resources Development (2004) No. 238) [57] | Where conditions permit, the provincial land and resources department, in collaboration with the relevant departments, may establish a comprehensive land price for the county (or city) levy area within the province. | |||

| 2005 | Notice on the Formulation of Unified Annual Output Value Standards for Land Requisition and the Collection of Comprehensive Land Prices for Regional Plots (Land Resources Development (2005) No. 144) [58] | Comprehensive land pricing for the eastern region should be established. In the central and western regions, the suburbs of large and medium-sized cities and other areas with suitable conditions should also actively promote the development of comprehensive land pricing for their districts. Additionally, other regions may establish standardized annual output value criteria for land requisition. | |||

| Same land at different prices | 2006 | Regulations on Land Acquisition Compensation and Resettlement for the Construction of Large and Medium-Sized Water Conservancy and Hydropower Projects (Decree No. 471 of The State Council) [51] | The total amount of compensation and resettlement subsidies for land expropriation is 16 times. | ||

| 2013 | Decision of the State Council on Repealing or Amending Certain Administrative Regulations (Decree No. 638 of the State Council) [59] | Regulations on Land Compensation and Resettlement for the Construction of Large and Medium-Sized Water Conservancy and Hydropower Projects (Decree No. 471 of The State Council) [51] The first paragraph of Article 51 is amended | The sum of compensation and resettlement subsidies for land expropriation is 16 times. | ||

| 2015 | 2015 Central Document No. 1 | For the construction of major water-saving and water-supply conservancy projects, the policies of land expropriation compensation and arable land compensation should align with those established for major national infrastructure projects, such as railways. | The sum of compensation and resettlement subsidies for land expropriation is 16 times. | ||

| Same land, same price | 2017 | Regulations on Land Acquisition Compensation and Resettlement for the Construction of Large and Medium-Sized Water Conservancy and Hydropower Projects (Decree No. 679 of the State Council) [59] | The compensation for land expropriated for the construction of large and medium-sized water conservancy and hydropower, as well as the resettlement fees, shall align with the compensation standards established for land utilized in railway and other infrastructure projects. | Same land, same price. | |

| Stage | Year | Policy Name | Adjustment Target | Adjustment Characteristics | Adjustment Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handling remaining issues | 1981 | Notice Regarding the Withdrawal of the Reservoir Area Maintenance Fund from the Power Generation Costs of Hydropower Stations (81 Electronic Finance No. 56) [60] | Clarify the source, management, and scope of use of the fund, utilizing it for future production recovery while gradually addressing the remaining issues in certain reservoir areas. | For the first time, the legacy of resettlement legacy is addressed. | The maintenance fund for the reservoir area shall be established. |

| 1985 | Measures for the Verification, Collection, and Administration of Water Charges for Water Conservancy Projects | For reservoirs facing ongoing issues, the water fee may be allocated to the reservoir resettlement assistance fund to support resettlers in developing their production capabilities. | Propose resettlement assistance. | Establish funds for resettlers in reservoir areas to assist them in developing productive activities. | |

| 1986 | General Office of the State Council Forwards the Ministry of Water Resources and Electric Power’s Report on Urgently Addressing the Issue of Reservoir Resettlement (Guobanfa (1986) No. 56) [61] | Act swiftly to address outstanding issues, provide further clarification on the guidelines for reservoir resettlement efforts, assist resettlers in restoring and enhancing their production capabilities, and explore new avenues for production development. | Focused on the resolution of the outstanding issues concerning the central government’s direct reservoir resettlers prior to 1985. | Clarify the methods of post-relocation support for resettlers. Follow a development-oriented approach to resettlement. Establish a resettlement assistance fund for reservoir area inhabitants. | |

| 1986 | Notice on Increasing the Construction Fund for Reservoir Areas (Finance and Industry No. 151 (1986)) [62] | Increase the reservoir area construction fund. | The extraction standard has increased fourfold compared to 1981. | The extraction standard for the construction fund of the directly affiliated hydropower station reservoir areas is set at CNY 0.004 per kilowatt-hour. | |

| From material to people | 1991 | Regulations on Land Acquisition Compensation and Resettlement for Large and Medium-Sized Hydropower Projects (State Council Order No. 74) [48] | Strengthen management practices, expropriate land judiciously, and ensure proper resettlement for displaced individuals. | For the first time, the administrative regulation explicitly outlines post-relocation support. | The state promotes and supports developmental resettlement by implementing a strategy that combines initial compensation and subsidies with support after relocation. |

| 1996 | Notice on the Establishment of a Subsequent Support Fund for Hydropower Stations and Reservoir Areas (Jijianshe (1996) No. 526) [63] | Clarify the scope of use, extraction timeline, and related management of the support fund. Adjust policies and standards for post-relocation assistance. Enhance the efficiency of fund utilization. | Establish a post-relocation support fund. | Regulations for implementing unified support policies and standards include a controlled allocation of CNY 250–400 per resettler per year. These regulations also establish uniform criteria for the amount and duration of fund extraction for hydropower stations commissioned after 1986. | |

| 2002 | Several Opinions on Accelerating the Resolution of Residual Issues Concerning Centrally-Administered Reservoir Resettlers (Guobanfa (2002) No. 3) [64] | Accelerate the resolution of outstanding issues related to the resettlement of individuals affected by centrally administered reservoirs that were commissioned before the end of 1985. | Agree to increase the collection standard for the reservoir area construction fund to CNY 1250 per person, with local matching funds, over a period of six years. | Regulations stipulate that resettlement support funds must not be distributed or subsidized to individuals. Furthermore, the central government has established a construction fund for reservoir areas to address the legacy issues faced by reservoir resettlers. | |

| Formal establishment | 2006 | Opinions on Enhancing the Post-Relocation Support Policy for Resettlement of Large and Medium-Sized Reservoirs (Guofa (2006) No. 17) [52] | In the short term, it is essential to address the basic needs and food security of individuals resettled from reservoir areas, as well as tackling the significant issues related to inadequate infrastructure in both reservoir and resettlement areas. Medium–long-term goals include strengthening the infrastructure and ecological environments in reservoir and resettlement areas, improving the living and production conditions of resettlers, and promoting economic development. | Representative document for the post-relocation support policy. | The standards for post-relocation support standards have been enhanced; they now offer an annual subsidy of CNY 600 per person. Additionally, the duration of support has been clearly defined. |

| 2006 | Regulations on Land Acquisition Compensation and Resettlement for Large and Medium-Sized Hydropower Projects (Decree No. 471 of The State Council) [51] | Aiming to ensure that the living standards of the resettled population meet or exceed their original levels. | The state implements a development-oriented resettlement policy that combines initial compensation, subsidies, and post-relocation support. | Clarify the methods of initial compensation, subsidies, and subsequent production support. | |

| 2015 | Notice on Further Strengthening the Post-Relocation Support Work for Large and Medium-Sized Reservoir Resettlement (Fagainongjing (2015) No. 426) [65] | Increase the intensity of post-relocation support efforts, expedite the resolution of poverty alleviation, actively promote the development of attractive communities for resettlers, and prioritize enhancing the income levels of resettlers to address the long-term development challenges in reservoir areas and resettlement zones. | Representative document for improving the post-relocation support policy. | Proposing the development of a poverty alleviation and hardship resolution plan for reservoir resettler, with a focus on increasing the income levels of those affected. | |

| Continuous improvement | 2018 | Notice from the Ministry of Water Resources on Further Enhancing the Post-Relocation Support for Large and Medium-Sized Reservoir Resettlement (Water Resettlement Document No. 208 (2018)) [66] | The post-resettlement support for those displaced by large and medium-sized reservoir resettlement is a crucial aspect of addressing rural issues. | Representative document for enhancing the post-relocation support policy. | Vigorously advance poverty alleviation and hardship relief initiatives for reservoir resettlers, actively promote the upgrading and development of industries, and prioritize strengthening entrepreneurship and employment training for these individuals. |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Human Development Report 2006—Beyond Scarcity: Power, Poverty and the Global Water Crisis; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R. Hydropower’s future, the environment, and global electricity systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Key Renewable Trends; Excerpt from Renewable Information, Technical Report; International Energy Agency: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- International Commission on Large Dams (ICLD). World Register of Dams. 2024. Available online: https://www.icold-cigb.org/article/GB/world_register/general_synthesis/number-of-dams-by-country (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Yao, Y.Q. 70 Years of Land Acquisition and Immigration in Hydropower and Electric Power Engineering. Water Power 2020, 46, 8–12+55. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Shi, H.; Sivakumar, B.; Peart, M.R. Population, water, food, energy and dams. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Katoch, S. Sustainability indicators for run of the river (RoR) hydropower projects in hydro rich regions of India. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 35, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. China-Involuntary Resettlement. Washington, DC. 1993. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/276691468262455582/China-Involuntary-resettlement (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- World Commission on Dams (WCD). Displacement, Resettlement, Rehabilitation, Reparation, and Development, WCD Thematic Review Social Issues I.3. 2000, pp. 35–36. Available online: https://pdf4pro.com/view/displacement-resettlement-rehabilitation-21a7c9.html (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Du, F.C. Ecological Immigration Research in the Sanjiangyuan Area; China Social Sciences Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Directions in Hydropower. 2009. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2009/03/12331040/directions-hydropower (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Cernea, M. Involuntary Resettlement and Development: Some projects have adverse social effects. Can these be prevented? Financ. Dev. 1988, 33, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.S. A preliminary exploration of the ‘secondary poverty’ of reservoir immigrants and countermeasures. Water Resour. Econ. 1992, 4, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, H.M. The Resettlement of People Displaced by Development Projects: Issues and Approaches. In Development, Displacement and Resettlement: Focus on Asian Experiences; Mathur, H.M., Ed.; Vikas Publishing House: Delhi, India, 1995; pp. 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Namy, S. Addressing the social impacts of large hydropower dams. J. Int. Policy Solut. 2007, 7, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Caspary, G. Assessing, mitigating and monitoring environmental risks of large dams in developing countries. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2009, 27, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J. India’s Narmada dams controversy. J. Int. Commun. 2007, 13, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Ahrenshop, M.P.; Charles, K. Resettlement lies: Suggestive evidence from 29 large dam projects. World Dev. 2018, 114, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, N. Political Responses to Dam-Induced Resettlement in Northern Uplands Vietnam. J. Agrar. Change 2016, 16, 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver-Smith, A. Catastrophes, mass displacement and population resettlement. In Preparedness and Response for Catastrophic Disasters; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 185–224. [Google Scholar]

- Kodirekkala, R.K. Structural Violations in Resettlement and Rehabilitation: Evidence from the Gundlakamma Project in Andhra Pradesh. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2020, 55, 552–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavhura, E. Dam-induced displacement and resettlement: Reflections from Tokwe-Mukorsi flood disaster, Zimbabwe. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 44, 101407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.; Lopez, M.C.; Moran, E.F. Uncompensated losses and damaged livelihoods: Restorative and distributional injustices in Brazilian hydropower. Energy Policy 2022, 167, 113048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Pohlner, H.; Charles, K.J. Cleaning up the big muddy: A metasynthesis of the research on the social impact of dams. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2016, 60, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Dams (WCD). Dams and Development: A New Framework for Decision-Making; World Commission on Dams: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, J.F.; Orange, D.; Habich-Sobiegalla, S.; Van Thiet, N. Socialist hydropower governances compared: Dams and resettlement as experienced by Dai and Thai societies from the Sino-Vietnamese borderlands. Reg. Environ. Change 2017, 17, 2409–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.L.; Fu, L.L.; Lv, B.F. A study on the comprehensive compensation mechanism for involuntary immigrants. Chin. Public Adm. 2015, 11, 121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Du, C.L.; Cheng, L.Q. From coercive to induced: Evolution and innovative path of reservoir immigration policy—Taking the reservoir immigration policy in Hunan Province as an example. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 22, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.N.; Li, L.F.; Xu, Y.N.; Wang, Z.Z. Evolution and outlook of land expropriation and immigration policies. Hydropower Pumped Storage 2021, 7, 116–120. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, A.; Lopez, M.C.; Johansen, C.I.; Moran, E. Hydropower, Social Capital, Community Impacts, and Self-Rated Health in the Amazon. Rural Sociol. 2022, 87, 393–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayum, M.; Li, W.; Sohail, M.T. Evaluating the Quality-of-Life and Happiness Indices of Hydropower Project-Affected People in Pakistan: Towards a Sustainable Future. Water 2024, 16, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, X. Transitioning from Large-Scale Infrastructure to Sustainable Development in China: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 45, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Ye, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H. New infrastructure-lead development and green-technologies: Evidence from the Pearl River Delta, China. Sustain Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y. To leave or not to leave? ‘Intention’ is the question. Investigating farmers’ decision behaviours of participating in contemporary China’s rural resettlement programme. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 97, 106888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Li, Y.H. Revitalize the world’s countryside. Nature 2017, 548, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X.J.; Xu, Y.; Wan, C.; Zhou, Y. How does resettlement policy affect the place attachment of resettled farmers? Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 105476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.P.; Zou, F. Research on content analysis. J. Libr. Sci. China 2004, 2, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gaur, A.; Kumar, M. A systematic approach to conducting review studies: An assessment of content analysis in 25 years of IB research. J. World Bus. 2018, 53, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, B.M.; Lundman, B.; Graneheim, U.H. Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 108, 103632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.W. A 70-year study of the evolution of China’s immigration and poverty alleviation. Chin. Rural Econ. 2019, 8, 2–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.N.; Shi, G.Q.; Yu, Q.N. A study on the historical changes and post-resettlement support policies of reservoir immigrants. People’s Yellow River 2009, 31, 9–10+13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.S. The Development and Reform of the Compensation Mechanism for Hydropower Project Immigrants. Water Resour. Dev. Res. 2005, 8, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.R. Property rights and land requisition system: A critical choice for China’s urbanization. Chin. Econ. Q. 2004, 4, 93–210. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.Q.; Duan, Y.F. A Review of Compensation Methods for Rural Involuntary Immigrants in Land Expropriation. J. China Three Gorges Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2006, 4, 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.S. The evolution process and poverty alleviation orientation of post-resettlement support policies for reservoir immigrants. Seeking 2019, 3, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Chen, S.J.; Chen, Y.H. Redefinition of developmental migration and its practice model in China. Water Power 2018, 44, 6–9, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.J. International experience in the resettlement of project-induced immigrants and its implications for the development of China’s western region. Econ. Theory Econ. Manag. 2001, 1, 69–70. [Google Scholar]

- The State Council. Regulations on Land Acquisition Compensation and Resettlement for Large and Medium-Sized Water Conservancy and Hydropower Projects; State Council Order (1991) No. 74; The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, X.; Qin, Y.; Dong, J.; Wu, J.; Li, B. Improved maps of surface water bodies, large dams, reservoirs, and lakes in China. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 3757–3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, X.; Zou, Z.; Dong, J.; Qin, Y.; Doughty, R.B.; Menarguez, M.A.; Chen, B.; Wang, J.; Ye, H.; et al. Gainers and losers of surface and terrestrial water resources in China during 1989–2016. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council. Regulations on Land Acquisition Compensation and Resettlement for the Construction of Large and Medium-Sized Water Conservancy and Hydropower Projects; Decree No.471 of The State Council; The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- The State Council. Regulations on Land Acquisition Compensation and Resettlement for the Construction of Large and Medium-Sized Water Conservancy and Hydropower Projects; Guofa (2006) No.17; The State Council: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- The State Council. Regulations on Land Acquisition Compensation and Resettlement for the Construction of Large and Medium-Sized Water Conservancy and Hydropower Projects; Decree No. 679 of the State Council; The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.S. Why the Later-Stage Support Project Supply of Reservoir Resettlement ls “Misalignment”: Discussions Based on Grassroots Governance Logic. J. Hunan Univ. Sci. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 22, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council. Regulations for Land Requisition for National Construction; Decree No.80 of The State Council; The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Decision of The State Council on Deepening Reform and Strict Land Administration; Guofa (2004) No. 28; The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land and Resources. Guiding Opinions on Enhancing the Compensation and Resettlement System for Expropriated Land; Land Resources Development (2004) No. 238; Ministry of Land and Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land and Resources. Notice on the Formulation of Unified Annual Output Value Standards for Land Requisition and the Collection of Comprehensive Land Prices for Regional Plots; Land Resources Development (2005) No. 1442005; Ministry of Land and Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- The State Council. Decision of the State Council on Repealing or Amending Certain Administrative Regulations; Decree No. 638 of the State Council; The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Electric Power Industry. Notice Regarding the Withdrawal of the Reservoir Area Maintenance Fund from the Power Generation Costs of Hydropower Stations; 81 Electronic Finance No. 56; Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China/Ministry of Electric Power Industry of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- General Office of the State Council. General Office of the State Council Forwards the Ministry of Water Resources and Electric Power’s Report on Urgently Addressing the Issue of Reservoir Resettlement; Guobanfa (1986) No. 56; General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Financial Regulatory Authority. Notice on Increasing the Construction Fund for Reservoir Areas; Finance and Industry No. 151 (1986); Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- National Energy Administration. Notice on the Establishment of a Subsequent Support Fund for Hydropower Stations and Reservoir Areas; Jijianshe (1996) No. 526; State Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China/Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China/Ministry of Electric Power Industry of the People’s Republic of China/Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- General Office of the State Council. Several Opinions on Accelerating the Resolution of Residual Issues Concerning Centrally-Administered Reservoir Resettlers; Guobanfa (2002) No.3; General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Water Resources. Notice on Further Strengthening the Post-Relocation Support Work for Large and Medium-Sized Reservoir Resettlement; Fagainongjing (2015) No. 426015; National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China/Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China/Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Water Resources. Notice from the Ministry of Water Resources on Further Enhancing the Post-Relocation Support for Large and Medium-Sized Reservoir Resettlement; Water Resettlement Document No. 208 (2018); Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ty, P.H.; Van Westen, A.C.M.; Zoomers, A. Compensation and Resettlement Policies after Compulsory Land Acquisition for Hydropower Development in Vietnam: Policy and Practice. Land 2013, 2, 678–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikura, R.; Nakayama, M.; Takesada, N. Lessons from Resettlement Caused by Large Dam Projects: Case Studies from Japan, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2009, 25, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiama, K.; Lengoiboni, M.; Van der Molen, P. In the Land of the Dammed: Assessing Governance in Resettlement of Ghana’s Bui Dam Project. Land 2017, 6, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Survey Methodology | Survey Period | Survey Location | Survey Theme | Target Group | Representative Interviews Selected and Numbers | Main Interview Question Topics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field observations and semi-structured interviews | 2021–2024 | Zhejiang Province | Three Gorges Reservoir; G Reservoir | ① Relevant government authorities; ② Monitoring entity; ③ Reservoir resettlers. | ① Three community workers, coded N01–N03; ② Monitoring personnel, coded N04; ③ Two resettlers, coded N05 and N06. | For relevant government authorities and monitoring entities: 1. Standards for land acquisition compensation and the implementation of follow-up support policies. 2. Policies related to the reservoirs from central to local levels. 3. Effectiveness of reservoir policies and the degree of livelihood restoration. 4. Challenges faced by policy implementation agencies during the policy implementation process. For reservoir resettlers: 1. Livelihood and income sources before and after relocation. 2. Integration into local life, including any challenges faced and requests for government support. |

| December 2024 | Jiangxi Province | W Reservoir | ① Relevant government authorities; ② Monitoring entity; ③ Reservoir resettlers. | ① Two village heads of resettlement villages, coded N07 and N08; ② Management center, coded N09; ③ Five resettlers, coded N10–N14. | ||

| October 2022–October 2024 | Guizhou Province | N Reservoir; P Reservoir | ① Relevant government authorities; ② Monitoring entity; ③ Reservoir resettlers. | Two government-affiliated staff members, coded N15 and N16. | ||

| Experts interviews | April 2024 | Jiangsu Province | Reservoir resettlement policy; policy phases; policy interrelation | 2 experts | Two experts, coded N17 and N18. | 1. Phases of water conservancy and hydropower relocation. 2. Characteristics and outcomes of reservoir evolution. 3. China’s policy system from land-acquisition- to development-oriented resettlement. 4. Existing problems and directions for improvement in reservoir policies. |

| April 2024 | Jiangsu Province | 2 experts | Two experts, coded N19 and N20. | |||

| May 2024 | Hubei Province | 2 experts | Two experts, coded N21 and N22. | |||

| May 2024 | Hubei Province | 1 expert | One expert, coded N23. | |||

| September 2024 | Jiangsu Province | 1 expert | One expert, coded N24. |

| No | Data Information | Data Source | Respective Link | Publicly Available |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Number of Reservoir Resettlers in China | World Bank Statistics; Literature; World Commission of Dams | e.g., https://wbwaterdata.org/; (accessed on 30 October 2024) https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/9126IIED.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2024) | Yes |

| 2 | Reservoir Resettlement Policies | Government Official Website; Policy Statistics Website | e.g., https://www.gov.cn/ (accessed on 30 October 2024); https://www.pkulaw.com/ (accessed on 1 March 2025) | Yes |

| 3 | Number of Reservoirs and Hydropower Stations | China Water Resources Bulletin | http://www.mwr.gov.cn/sj/tjgb/szygb/ (accessed on 3 March 2025) | Yes |

| 4 | Policy Implementation | Local provincial and municipal statistical yearbooks; Local government annual reports | - | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, X.; Lu, J.; Chen, S. A Study on the Evolution and Interrelation of China’s Reservoir Resettlement Policies over 75 Years. Water 2025, 17, 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17101444

Wu X, Lu J, Chen S. A Study on the Evolution and Interrelation of China’s Reservoir Resettlement Policies over 75 Years. Water. 2025; 17(10):1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17101444

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Xiaoqing, Jiahua Lu, and Shaojun Chen. 2025. "A Study on the Evolution and Interrelation of China’s Reservoir Resettlement Policies over 75 Years" Water 17, no. 10: 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17101444

APA StyleWu, X., Lu, J., & Chen, S. (2025). A Study on the Evolution and Interrelation of China’s Reservoir Resettlement Policies over 75 Years. Water, 17(10), 1444. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17101444